Introduction

A traveler taking autoroute A-47 southwest from Lyon will first pass by the industrial city of Givors and then descend into the Gier valley. The traffic passes speedily by a cluster of somber little industrial towns that darken an otherwise verdant and pleasant valley: Rive-de-Gier, La Grande Croix, L'Horme. After L'Horme, one comes upon Saint Chamond, the least forgettable of these towns, for there the road goes through, instead of by, the city. A signal, which seems always to be red, halts traffic. The tall smokestacks, darkened old factories, and old houses that retain traces of black smoke impress themselves upon the traveler's consciousness. The green light permits the traveler to continue on to Saint Etienne, a larger version of these industrial towns, but dotted with recently cleaned public buildings and renovated town squares that burst with fountains.

Few tourists would feel inspired to explore Saint Chamond. But a narrow street that goes off to the right leads the venturesome up a steep hill into a neighborhood whose origins date back to the year 640. This hill certainly lacks the charm of Lyon's vieille ville or Croix Rousse. Its past, however, contains a comparable richness. Originally the home of Archbishop Ennemond who came from Lyon, this hill hosted numerous seigneurial lords and religious orders.[1] But apart from street names—rue du Château, rue des Capucins—and the ruins of the chapel of Saint John the Baptist, little of that past remains. Instead one finds the small, unsightly church of Saint Ennemond (see figure 1) and an architecture that speaks to an industrial rather than a religious past.

From at least the sixteenth century, this hill teemed with iron forgers, ribbon weavers, silk workers, and, later, miners, stonecutters, and carpenters. At its base, clustered along the Gier River (currently paved over), millers worked their silk on water-run spindles. The neighborhood of Saint Ennemond today appears much as it did in the middle of the nineteenth century. As one

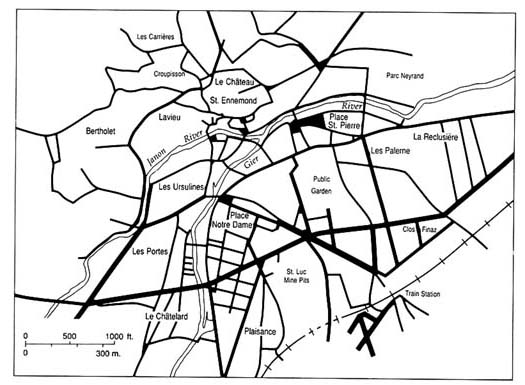

Map 2. Saint Chamond, 1890

military officer described it in 1843, "the houses are of simple construction, built with cut stone." The streets are "generally dirty and poorly paved in round stone."[2] Now blotted with timeworn layers of asphalt, the cobblestone streets twist among old apartments that once housed enormous ribbon looms and shops for iron forges (see figure 2).

The houses designed for tools of production as much as for people testify to a past that knew little distinction between work life and home life. They remind us that one of the most common elements in preindustrial work was its heavy reliance on families rather than factories as work units. From the top of the hill in Saint Ennemond, one can look down upon the lower city, on the other side of the autoroute, where in the nineteenth century industries built their own shrines—braid factories, steel plants, and the immense churches of Notre Dame and Saint Pierre, renovated with bourgeois funds in the 1870s. Today, urban, working-class apartments—tall, gray HLMs (Habitations à Loyer Modéré) built since World War II—dominate the landscape.

Saint Chamond's architecture alone hints at the multiple layers of its history. The differences between the hill and the lower city represent the transformation in workers' lives that came with industrialization. Indeed, the drama that unfolded within these structures during the nineteenth century repeated itself countless times throughout industrializing Europe: productive labor left the home and became concentrated in factories.

When production took place within the home, work and family fused in a number of ways. Labor shared time and space with eating, sleeping, lovemaking, childbearing and childrearing, and socializing with friends and kin. Family and household concerns frequently and spontaneously broke up the sixteen-hour workday. Equally important, the bond between work and family had cultural significance. Men, women, and children often labored as a team. Parents passed skills on to their children, trained and disciplined them, and initiated them into the secrets and associations of their trades. Marriages formed around work relationships and in turn reinforced those relationships. Even when the family members labored at unrelated tasks, the common effort to sustain a family income bound them together.[3]

In removing work from the home and centralizing it near sources of power, mechanization transformed the interrelationship

between family and labor. Merchants no longer put out work to cottagers; instead, the latter had to leave their homes to earn a daily wage. Frequently they had to abandon their homes in the countryside and migrate to the towns and cities where production became concentrated. Not only did such migration often break up families, but factory labor itself changed the relationship between parents and children. Mechanization made some skills obsolete and created other new skills. Training no longer took place in the home and, for the most part, sons no longer learned from their fathers. Factory work also transformed the economic role of women. Because leaving the home to work conflicted with child care, mothers could no longer easily contribute to the family income.

The object of this book is to examine precisely what this dramatic change in the relationship between work and family meant for the lives of nineteenth-century workers. Specifically, it uses family formation and family structure as windows onto the world of workers and as points of departure for understanding workers' material experiences with industrialization and changes in the organization of work. How workers adapted to industrial change in turn cannot be understood apart from their relations with employers and the local elite, whose behavior—benevolent, utilitarian, or a combination of both—created the context in which workers' consciousness developed. Thus a secondary focus of this study is an analysis of class relations in the light of changes in family structure. Industrial change pressed workers into new modes of survival. It also forced the elite to develop new strategies to preserve and discipline the working class and to try to mold workers in their own image.

The city of Saint Chamond and its surrounding region offer rich opportunities to examine the relationship between family structure and economic and technological transformations, as well as implications family change had for class relations. The city is located in the Stéphanois basin, an area which corresponds roughly with the arrondissement of Saint Etienne in the department of the Loire. Referred to frequently as "the cradle of the industrial revolution in France," this basin has long attracted scholarly attention.[4] Its mountains and valleys provided industry with abundant primary resources—particularly in water power and coal deposits—and set the stage for industrialization along classical lines. The region attracted

industry not just because of its resources but also because agriculture alone could no longer support the growing population.[5]

Cottage industry, and especially the employment it provided for women and children, thus contributed significantly to the sustenance of the rural population. An extensive network of domestic workshops produced nails, bolts, files, luxury arms, glass, ceramics, silk ribbon, and thread. By 1790, these industries supported a population of 118,981 in the Stéphanois region. Beginning about 1820, the importation of English metal-working processes, combined with the introduction of steam power, radically transformed this region's economy, demography, and social relations. By 1866, the Loire ranked as one of the most densely populated departments in France.[6] Most of this population crowded into the principal Stéphanois cities of Saint Etienne, Firminy, Le Chambon-Feugerolles, Saint Chamond, and Rive-de-Gier. Stéphanois industrialization also forged a militant working class and an entrepreneurial bourgeoisie committed to republicanism. This workshop of France has become a laboratory for historians interested in studying the economic, social, and political impacts of industrialization.

Saint Chamond's development pivoted on the commercial manufacturing of iron and silk. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ribbon merchants and forge masters expanded the domestic industries of ribbon weaving and nail making throughout Saint Chamond and deep into the adjacent countryside. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, heavy metallurgical production and mechanical braid-making became established. By the 1850s, for a number of reasons that varied from industry to industry, ribbon and nail merchants either left Saint Chamond entirely or invested their capital in the new factory-based industries. The simultaneous mechanization of silk and iron production industrialized Saint Chamond more completely and dramatically than its neighbors. This development in turn transformed the town's labor force, environment, and architecture. Industrialization largely eliminated domestic production, polluted the environment, and drew thousands of migrants from the surrounding countryside. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the town's population grew from 4,000 to 14,000 inhabitants.

Saint Chamond's transition from artisan-based production to full-scale factory production and the pattern of migration and urban

growth there make it an ideal setting for the study of family change among workers. Its combination of metallurgy and textiles makes possible a comparison among different types of artisans and industrial workers; previous social, economic, and political histories of the region, moreover, offer an implicit comparative perspective with other towns and cities.

This book argues that among both artisans and industrial workers a strong relationship existed between the organization of labor and gender roles, the number of children born to workers, and the number of their children who died early in life. Among artisans, family structure depended upon gender-specific demands of labor and varied by occupation. Occupational differences became less important with industrialization. By removing work from the home, mechanization forced workers to restructure their family lives. They had smaller families for both voluntary and involuntary reasons. Most couples clearly attempted to limit the number of their children more than they had in the past, but many had smaller families also as a result of poor health and infant and child deaths.

As workers lost control over their work lives, curtailing family size became more important as a means of exercising self-determination. But many working-class families did not succeed in surviving independently and had to rely on material assistance. In this regard, industrialization meant new forms of dependence on the employer class. Removal of work from the home not only made material independence more difficult but undermined workers' power in other ways. Factory work deprived them of the ability to develop skills and authority within their own families. Apprenticeship either disappeared entirely or came under factory control. Factory work attracted to the city migrants who also suffered a loss of independence from employers because they lacked strong familial bonds and social ties.

This study of industrialization and the working-class family fits into a broad body of literature that spans a century and a half, and its conclusions will clash with those of many studies that have preceded it. Little dispute is engendered by the statement that the removal of work from the home had significance for workers' lives; what that significance was, however, escapes consensus. Throughout the nineteenth century, many observers sharply criticized factory labor. As early as the 1830s, sociomedical economists such as

Louis René Villermé brought attention to the miserable, insalubrious conditions in factories.[7] Later in the century, when working conditions had improved somewhat, political economists still had reason for concern. The concentration of workers into industrial urban slums made them more visible. Crime and poverty made it apparent that workers' home lives had become a source of moral degeneracy. Consternation over working-class morality grew more intense with every social upheaval in which they participated: the revolution of 1830, pervasive working-class unrest shortly thereafter, the revolution of 1848, the increased incidence of strikes in the 1860s, and most important, the Paris commune of 1871. This last event presented the specter of socialism in its most pronounced form yet.

In response to the apparent moral decay in French society, by the 1870s Frédéric Le Play had begun to formulate a sociology of the working-class family. With a methodology based on observation and induction, he concluded that partible inheritance, legislated during the Revolution of 1789, had proletarianized rural workers and devastated their families. It destroyed the traditional stem family, in which the father perpetuated his authority by transferring family property to only one heir, who would provide a pension for his parents and cash or dowries for his siblings. Equal inheritance weakened paternal authority and destroyed the family as a moral and economic unit. Large-scale industrialization accelerated this destruction, particularly for the working classes, for it further destabilized family life.[8]

Le Play inspired many followers who adopted his methodology as well as his conclusions. Among them was the abbé Cetty, who in 1883 published La famille ouvrière en Alsace . Based on interviews with workers in the industrial centers of Alsace, this study attempted to uncover the roots of working-class misery. Although Cetty's perceptions are often skewed by his own moralistic predisposition, his thorough investigation leaves rich material for historians of the working class. Following Le Play's reasoning, Cetty believed that lack of patrimony and the removal of work from the home destroyed the power and authority of fathers over their sons. In former times, the worker's children "grew up under his eyes, were raised by his side, and when they came of age, he made them a part of his work, took them by the hand, and guided their first efforts." But with the introduction of factory labor, young boys associated

talent, art, and progress only with the machine and not with their fathers' experience.[9] Factory organization encouraged insubordination toward the father, for the son did not work under his direction. Working for the same employer placed father and son in a position of equality and sometimes even put the latter in a superior position.[10]

Cetty also attributed the "almost irredeemable decadence" of the family to the unhappy fate that industrialization had imposed on women. He pointed to the central question of the family wage: women had almost no choice but to enter the factory. Prostitution offered the only other alternative. Their departure from the home to the factory attacked domestic life at its very source. And removal of productive labor itself disorganized the family and reduced the home to a mere shelter for eating and sleeping: "[The family] is no longer a hearth around which a new generation grows and develops with the same faith, the same soul, the same character." Parents and children returned from the factories too exhausted for conversation or education. The family lost its role as a source of moral authority and knowledge.[11]

The decline in parental, particularly paternal, authority created a vicious cycle in each generation that weakened the structure of the family. It led to early marriages and numerous children, which in turn resulted in high rates of infant mortality and death from childbirth. Women worked in factories until they delivered babies and then immediately resumed work. Between 1861 and 1870, Mulhouse averaged 33 infant deaths per 100 legitimate births. Worse than early marriages was the habit of concubinage (cohabitation) when workers could not afford to marry. Cetty found the practice reproachable in and of itself, and he showed it also helped produce higher rates of infant mortality: 45 of every 100 illegitimate babies died before they were a year old.[12]

The decline of paternal authority, the necessity for women to work outside the home, the destruction of family traditions, and premature marriages made the family unable to meet its own needs. The death of either parent, which frequently came early, would throw the family into a state of dependence. Other relatives no longer cared for family members as they had in the past. Institutions thus developed to meet those needs. Orphanages, kindergartens (salles d'asile ), and hospices had become establishments of "first necessity"; in Mulhouse, the salles d'asile "render such great

services, that have so entered the customs of the inhabitants, that it would be hard to imagine this city without them."[13] Although Cetty praised charitable activities in the industrial centers of Alsace, he did not look to charity as a solution to the problems of the working-class family. Instead, the family had to be strengthened from within. He cited efforts among some industrialists to reinforce morals both in and outside the workplace.[14]

Cetty and Le Play condemned industrialization because it ruined the family and thus undermined the moral basis of society. Noteworthy about their position is that they did not blame the worker for moral degeneration. Instead, the family had become the "first victim of industrialism," whose situation required the invention of a new word, pauperism .[15]

Not all contemporary observers shared the views of the Le Play school. The well-known inquiries of Louis Reybaud and Armand Audiganne, for example, did not consider the removal of work and of women from the home as destructive to the family. The fact that women had always performed productive labor made their entry into the workshops and factories seem logical. Indeed, many investigators believed factory work to be beneficial to women because machine-tending suited their strength. They did not, moreover, view factory work as a source of family decay. Employers and observers alike frequently indicated that unmarried women supplied most of the labor force; they left the factory either after marrying or after the birth of their first child. Unlike Cetty, Reybaud and Audiganne believed the miserable slums they witnessed in their travels resulted, not from industrial capitalism leading systematically to pauperism, but from individual moral failings.[16]

The most recent generation of scholarship echoes these latter observers insofar as it has treated the working class as maker of its own history rather than as passive victim of the industrial process. E. P. Thompson pioneered new avenues of research by bringing to light the existence of a positive, rich working-class culture that enjoyed independence.[17] Labor movement activity grew out of that culture. As social history came to focus on working-class life rather than on labor movements and strike activities alone, the working-class family emerged as an important source of culture.

Recent research tends to support the view that industrialization did not severely disrupt family life among workers, and certainly that it did not destroy it in the ways Cetty and others suggested.

Examples abound. Nearly thirty years ago, Neil Smelser noted that mechanization in the English cotton industry did not break up the family; parents employed their own children in factories and thus replicated some of the teamwork they had depended upon in their homes. Michael Anderson later demonstrated that, if anything, migration and industrialization strengthened relations among family and kin. Migrants from the countryside did not travel alone to the city. They came with, or after, family, friends, and neighbors. Hardship forced them to rely on one another even more than before. During critical life situations—unemployment, sickness, the death of a key wage-earner in the family, widowhood—workers relied on one another and used bureaucratic forms of assistance only as a last resort. In his more recent study of the Lyonnais region, Yves Lequin also stressed continuity in the industrial process: industry moved to the countryside long before workers moved to urban industry. When they did migrate to the city, many came from only a day's journey away, and they maintained contact with the countryside. Moreover, they came from regions that already had the same industries as those in the city. In other words, occupational and thus cultural continuity mediated the move from country to city.[18]

Lequin's conclusions complement another direction of research that further turns attention away from industrialization per se as the most important watershed in the history of the working class. Wage labor in the context of cottage industry proletarianized workers and transformed their family lives long before mechanization did. Artisans became proletarianized because they lost control over the purchase of raw materials, tools of production, and the marketing of finished products. This process, recently labeled proto-industrialization , prepared workers for urban factories and was a phase not only preceding industrialization but necessary to it.[19]

The focus on proto-industrialization has brought to the surface the darker side of domestic industry. In addition to proletarianizing workers, it also reshaped the working-class family by encouraging workers to have large numbers of children so that they could contribute wages to the family income.[20] It could and did lead to the exploitation of men, women, and children. In the light of recent research, the Le Play school's nostalgia for domestic industry looks extremely romantic. Not only did the working-class family survive

factory labor intact, but the mode of production preceding it offered a far from ideal situation for the traditional family as they conceived it.

In their path-breaking study of industrialization and women's work, Joan Scott and Louise Tilly also downplay the severity of change that mechanization brought to the family. They conclude that the family provided "a certain continuity in the midst of economic change" in the contexts of domestic and of factory production. Even though industrialization removed work from the home, the spheres of family and work did not separate completely; the family "continued to influence the productive activities of its members."[21] Most important, they called attention to the crucial relationship between production and reproduction. In the transition from the family economy to the family wage economy and family consumer economy, workers adjusted their fertility strategies. According to this scholarship, the family turned out to be remarkably flexible in the face of industrial change.

The studies of these researchers and others investigating the family economy have demonstrated that although most production ultimately did leave the home, the process occurred gradually. New types of domestic industry replaced those that became mechanized. The introduction of electricity began another era of home industry, much as did the personal computer in recent years. Married women and mothers, by continuing to work in the home, carried on the same kind of productive activities they always had. Home industry permitted them to continue to juggle productive and reproductive responsibilities.[22]

Implicitly and explicitly, this scholarship suggests that the family served not only as a source of continuity but, indeed, a source of strength, if not defense. Echoing Michael Anderson's findings, Jane Humphries has offered the hypothesis that family hardship promoted a "primitive communism" among workers that, in turn, helped promote class consciousness. In the effort to avoid the "degradation of the workhouse," only kinship ties could "provide an adequate guarantee of assistance in crisis situations." Not only were kin ties strengthened, but the struggle to provide for nonlaboring members of the family created a consciousness of social obligation that extended to nonkin. This sense of obligation in turn established a basis for class consciousness and class

struggle. The family's ability to survive independently of state institutions provided a foundation for class resistance to economic exploitation.[23]

The existence of a powerful labor movement by the end of the nineteenth century demonstrates that industrialization did not destroy the moral fabric of the working class. Workers could not have organized if factory labor had reduced their family lives to total disarray. Complete demoralization would have resulted in apathy. On the contrary, a positive culture gave workers the class consciousness, inspiration, and courage to resist exploitation and demand more rights in the workplace. William Reddy, for example, has recently documented that protest often derived from the effort to protect not just the family income but a way of life organized around it.[24]

The recent empirical research seems to overturn the assessments of working-class life that are based on eyewitness accounts of the Le Play school. This study of workers in Saint Chamond, however, argues that while the modern research corrects the Le Play school it goes too far in downplaying the extent and profundity of change that occurred in family life. It has also left unexplored the implications those changes had for class relations. The argument presented here turns to an analysis of demographic patterns as a key to understanding economic change and working-class family life. A close examination of marriages, births, and deaths among proto-industrial and industrial workers reveals that an enormous change in the family did occur with industrialization: through deliberate control over births as well as through high mortality, family size declined; the working-class family also became weakened as a basis for class culture as it lost a certain measure of autonomy.

Nineteenth-century observers and modern historians have noted that industrialization caused a lowering of the age at marriage, reduced life expectancy, and increased infant and maternal mortality. But at the same time, in part because of earlier marriages, it also caused a larger than average family size among workers. While workers supposedly continued to have large families, contraceptive practices spread regionally and conquered all of geographical France. Thus in the face of this overall decline, the newest of social classes, that of urban industrial workers, apparently remained a bastion of high fertility. While considered "laggers" in the general demographic transition of Western society, they eventually joined

the middle class in having smaller families once infant mortality decreased and their standard of living rose.[25]

Analyses of family structure among industrial workers have been based mostly on aggregate data from vital events or from census reports, neither of which can provide a completely accurate picture of fertility or trends in fertility. Aggregate data, for example, cannot control for such factors as duration of marriage; census reports supply information for households rather than for families and do so only at five-year intervals. A more accurate method for documenting fertility change in a local context is through family reconstitution—the actual reconstruction of individual families through linkage of birth, death, and marriage records over two or more generations for the entire population of a single locality. Most family reconstitution studies have concentrated on preindustrial populations, in part because they seek to establish the roots of the fertility transition, which began prior to industrialization. Moreover, in practical terms, the task of family reconstitution is an overwhelming one even for small village populations. Few family reconstitutions have been conducted in an urban context, and none has been done, to my knowledge, for a nineteenth-century industrial city.[26] Yet without this technique, gaining a detailed picture of fertility and mortality among urban workers and thus better insights into the material conditions of their family lives remains beyond the historian's grasp. Through a method of cohort analysis, I have overcome most of the obstacles inherent in reconstituting families in an urban population.[27]

Using family reconstitution, Part 1 of this book explores the relationship between work and family in two contexts: among proto-industrial artisans in the first half of the nineteenth century, and among factory workers in the second. Although workers did continue to have relatively larger families, family size declined considerably with industrialization. More important than the decline itself are the conditions under which it took place: workers had fewer children not because they began to follow the path of their middle-class counterparts, but because the industrial work organization pressed them into doing so. The decline in fertility neither stemmed from an improved standard of living, as is often argued, nor did it necessarily lead to a higher standard of living. Instead, fertility and mortality signified distress among certain elements of the industrial population.

Part 1 also explores the meaning that change in work organization had for the family by reexamining and questioning the continuity between rural and factory industries, as well as occupational continuity between generations. Registers of births, deaths, and marriages used for family reconstitution contain detailed information about occupation, birthplace, and residence. The linkage of these records in the individual family histories over two or three generations in Saint Chamond thus makes possible a close examination of migration and occupational change. Despite the proletarianization prior to mechanization, and the continuity it provided for urban industry, migration and new modes of production indeed produced a generational break with the past. Occupational inheritance did decline, and where it persisted it created fewer and less meaningful bonds among family members. Migration also broke up families even when it strengthened ties among those members who stayed together.

This study of occupational change and family structure also touches on the question of whether patriarchal authority within the family deteriorated, leaving family life more permeable to employers' paternalistic incursions. Removal of work from the home meant a decline in occupational inheritance as well as a loss of family cohesion. This process portends a loss of social power as well as of authority over the work process itself. When skills and their perpetuation remained in the domain of the family rather than of the capitalist, workers had leverage over who attained skills. The decline in occupational inheritance and the fact that its very nature changed clearly transformed the relationship between parents and children, because parents lost much of their ability to shape a child's future, and children had to leave the family to obtain skills. The family lost custody over technological knowledge. This process also changed the relationship between employers and workers, for the former began to control apprenticeships.[28]

A third area of investigation in this book is class relations, to which Part 2 is devoted. This subject has certainly received more than its share of attention from historians. And yet scholars have focused mostly on workers who exerted power. They have not often enough questioned why the majority of workers did not organize and why those who did failed in their efforts to construct a society according to their own vision. This study examines class relations in a society where workers did not exercise very much

power and seeks to explain why this was the case despite their efforts to organize. One area of investigation is the practice of paternalism, a topic that has received increased attention in recent years. Paternalism has generally been examined in the context of workers who rejected it, which has led to the conclusion that it did not succeed in its goal of pacifying the working class. Many workers did indeed shun material assistance. Others, however, had no choice but to rely on it. Whether or not it achieved its goal, material assistance did play a role in class relations that has, as of yet, remained relatively unexplored.

The use of paternalism to describe various forms of charity in the late nineteenth century has confused the issue because the word connotes an anachronistic, Old Regime view of the world and thus one whose policies were doomed to failure in the nineteenth century. The analysis of charity in Saint Chamond is based primarily on the archives of the city's hospice—a source rarely used in studies of the working class—as well as on employer practices within and outside the workplace. These sources show that industrialists in Saint Chamond tailored their paternalistic activities to conditions of urban industrialization. They adopted new ways of administering material assistance such as employer-controlled insurance and child-care centers. These institutions not only addressed the new pressures that came with industrial society but also attempted to moralize workers. Rather than restoring power and authority to the working-class family, these paternalistic practices assumed some family functions and further deprived workers of independence. What happened in Saint Chamond at least partially supports recent theories regarding industrial discipline derived from Michel Foucault and Jacques Donzelot and applied by Michelle Perrot.[29] The inability to survive independently made many working-class families permeable to intervention from local caretaking institutions. The family became a medium for class relations and an arena for elite influence.

Part 2 also examines local politics and the labor movement in this context. Here previous work done on the Stéphanois region provides a comparative perspective. Yves Lequin, Sanford Elwitt, Michael Hanagan, and David Gordon have analyzed working-class and middle-class left-wing political activity in this region during the nineteenth century.[30] In both its bourgeois and its working-class political consciousness, Saint Chamond proved exceptional

for this region and provides interesting points of contrast. Its bourgeoisie remained devoutly Catholic and politically conservative, if not monarchist, through the end of the nineteenth century, while the working class was relatively tranquil. This book argues that rapid industrialization, the need to rely on material aid, and the Catholic, monarchist, and paternalist stance of employers weakened workers' propensity to develop a strong political movement; moreover, because local priests were friends of the poor, workers could not fully sympathize with the anticlericalism of the left wing. At the same time, workers did retain a cultural independence and many of them resisted elite domination even though it did not become effectively translated into political opposition. Their resistance is all the more remarkable given the cultural barriers to the formation of worker associations and the pervasiveness of employer efforts at political hegemony.

Every city or region is unique. The hope of a local study is to speak, not to that uniqueness, but to common human experience. In Saint Chamond, the years between 1860 and 1880 mark a period of discontinuity in working-class culture and family formation strategies. These workers' experience does not fit easily with the thrust of recent scholarship. But perceptions of continuity and discontinuity do not necessarily contradict one another. Instead, they represent coexisting realities. Neither proto-industrialization nor industrialization assumed homogeneous forms in their respective developments. Nowhere did industrial capitalism develop linearly. Thus the impacts of industrialization on the working-class family varied as well. In Saint Chamond, mortality and fertility rates suggest that industrialization caused distress for the working-class family. Rarely are demographic patterns unique to a single locality, and Saint Chamond was not alone in its high rates of death and low rates of birth. Nor was it unique in its strong paternalism. In the structural weakening of the family and its vulnerability to assistance from the elite, the experience of the Saint-Chamonais should provide insight into workers' lives in other industrial centers.