PART THREE—

CREATING COMMUNITY

14—

Crucifixion, Slavery, and Death:

The Hermanos Penitentes of the Southwest

Ramón A. Gutiérrez

There is in the remote mountain villages of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado a penitential confraternity known as La Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, the Pious Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene, popularly known as the Hermanos Penitentes. The group's devotion to the passion and death of Christ, still commemorated with rituals of crucifixion on Good Friday, has long fascinated believers and disbelievers, promoters and detractors of Hispano culture in the Southwest. Since 1833 when Josiah Gregg first described the penitential rituals he observed during Holy Week at Tomé, in his much-read book Commerce of the Prairies, wells of ink have been spent recounting the activities of the Hermanos Penitentes.[1] Protestant authors in the nineteenth century focused on the brutality and barbarity of the bloody flagellants and their crucifixion rite to validate Anglo-American presuppositions about New Mexican Hispano Catholicism—namely, that centuries of Roman Catholic rule in what became the U.S. Southwest had bred a backward, primitive, and savage piety that hampered the civilizing mission of the Anglo capitalist gospel.[2]

At the end of the nineteenth century, a host of pundits, visionaries, and pop-historians, individuals who as a group lacked the linguistic tools and cultural sensitivity to study much less understand the activities of the Hermanos Penitentes, focused a voyeuristic gaze on the group. "Orientalizing" the Upper Rio Grande Valley for touristic purposes, they painted pictures of a primitive, simple landscape and populace in the Southwest that resembled Egypt and offered a potential escape from the decadent industrial northeastern United States. In this frame of reference, even sympathetic advocates of the brotherhood depicted it as one of the "last vestiges of medievalism in America," as "mired in webs of iconographic confusion," and locked "in a time-warp oblivious to history."[3]

This essay on the history of the Pious Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene forms part of a larger research project on the history of Indian slavery in New Mexico. Much of the extant scholarship on slavery in the Americas has focused on the African experience. Reams have been written on the Atlantic passage, on the African slave experience in various plantation economies, and on the process of manumission, the meaning of freedom, and the stigma and meanings of color for these former slaves throughout the hemisphere. But except for Silvio Zavala's 1967 documentary history, Indian Slaves in New Spain, little attention has been given to the role of Indian thralls in the hacienda and ranch economies of the hemisphere.[4] My goal here is to begin to fill this lacuna, if only very partially, by studying the cultural history of genízaros, as Indian slaves were known in New Mexico, focusing in this essay on their religious organizations and rituals.

Membership in the Pious Confraternity of the Our Lord Jesus Nazarene, even to this day, is considered a fundamental way of life. The confraternity offers its members a code for living that is marked by a year-long calendar of pious acts, a regimen of prayer, fasting, mortification, and social works of mercy. Confraternity activities reach a high pitch during Holy Week, when Christ's passion and death on the cross are commemorated. From Palm Sunday until Holy Saturday, members of the brotherhood reenact the Way of the Cross, which according to some late-nineteenth-century accounts, actually culminated in the death of the surrogate Christ.

To understand the historical and cultural meanings of the daily, weekly, and Holy Week rituals of the La Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, one must approach their rituals like one approaches the careful analysis of an onion, peeling away layer after layer. The organizational form the brotherhood takes is the cofradía, or confraternity. The words confraternity and cofradía both derive from the Latin word confrater, which literally means a "co-brother." A confraternity was a group of persons who lived together like brothers in a larger fictive or mystical family. Confraternities had their origin in Europe during the twelfth century as voluntary associations of the Christian faithful committed to the performance of acts of charity. In an era before social services were provided by the state, the pressing social needs created by poverty and vagrancy accelerated the formation of religious brotherhoods. Victims of catastrophe, disease, or unemployment found their basic needs met through the works of mercy performed by confraternities. Members of confraternities, by performing such acts, gained grace and indulgences, which were deemed sure routes to sanctity and personal salvation.[5]

Confraternities dedicated themselves to the promotion of particular devotions to Christ, to the Virgin Mary, and to various saints. They required episcopal sanction for formation and were governed by statutes that contained their rule, their prescribed ritual practices, their required works of piety, and festival days of observance. Despite great differences in devotional

practices, the common thread that bound brotherhoods was their obligation to lead model lives of Christian virtue, to care for the physical welfare of the locality's needy, to bury the dead, and to pray for the salvation of departed souls.[6]

The familial language that confraternities employed made them vibrant organizational forms for the expression of broader social affinities. As equal members of the mystical body of Christ joined in spiritual brotherhood, for purposes of larger social good, residents of a community could momentarily put aside the enmities and distrust that typically marked the daily interactions of families, households, and clans. Indeed, through the creation of religious associations of co-brothers who were united in the mystical body of Christ with God as father and the Church as mother, Catholic prelates and theologians explicitly critiqued the secular, biological theory of family that had existed in Western Europe since the second century A.D.[7]

Nowadays, when we speak of familia, or family, we equate it with our immediate blood kin. That which is within the family is intimate, within the private walls of the home, and devoid of strangers. But if we focus carefully on the historical genealogy of the word familia, on its antique meanings, it was tied neither to kinship nor to a specific private space or house. Rather, what constituted familia was the relationship of authority that one person exercised over another, and more specifically, familia was imagined as the authority relationship of a master over slaves. The etymological root of the Spanish word familia is the Latin word familia. According to historian David Herlihy, Roman grammarians believed that the word had entered Latin as a borrowing from the Oscan language. In Oscan famel meant "slave"; the Latin word for slave was famulus. "We are accustomed to call staffs of slaves families. . . . we call a family the several persons who by nature of law are placed under the authority of a single person," explained Ulpian, the second century A.D. Roman jurist. Family was initially that hierarchical authority relationship that one person exercised over others, most notably slaves, but in time, also over a wife, children, and retainers.[8]

It was to temper this authority that a master exercised over his slaves or family that the Church elaborated the relationship of spiritual fraternity that was born of baptism. Through the sacrament of baptism one was born again a child of God, thus defining the person both as a natural and a spiritual being, with loyalties both to biological natural parents and to spiritual parents as well. For slaves, who often had no natural or genealogical relationships in a town, the confraternity served as an alternative kinship network morally obligated to offer protection and succor in times of need.[9]

In every town and village, in both Europe and the Americas, vertical and horizontal confraternities existed side by side.[10] The vertical confraternities integrated a locality's social groups, joining the rich and the poor, Spaniards and Indians, the slave and free. By emphasizing mutual aid and ritually

obliterating local status distinctions and social hierarchy, vertical confraternities diffused latent social tensions into less dangerous forms of conflict. In place of overt class antagonism, parish confraternities squabbled over displays of material wealth, the splendor of celebrations, and the precedence due each group.

If vertical brotherhoods integrated a town's various classes, horizontal confraternities mirrored a locale's segmentation, marking organizationally status inequalities, be they based on race, honor, property ownership, or other material and symbolic goods. Relationships of domination and subordination were often articulated through confraternity rivalries and their symbolic opposition throughout the yearly cycle of sacred rites. The social supremacy of the Spanish gentry, for example, was expressed through their opulent confraternity rituals and celebrations to various saints. Dominated groups such as Indians and slaves also expressed their dignity and their collective identity with acts of piety that rivaled those of their oppressors.

Such horizontal separation of social groups is clearly apparent in the symbolic opposition that has existed in Santa Fe, New Mexico, from the eighteenth century to the present, between the Confraternity of Our Lady of Light and the Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene, popularly known as the Brothers of Darkness. During the colonial period, noted Fray José de Vera, the population of the Kingdom of New Mexico was divided into "three groups . . . superior, middle and infamous."[11] The superior class consisted of noble men of honor, the conquistadors of the province. Below them were the landed peasants, who were primarily of mestizo or mixed ancestry but who considered themselves Spaniards to differentiate themselves from the Indians. At the bottom of the social hierarchy were the "infamous" genízaros who were dishonored by their slave status.

The Confraternity of Our Lady of Light, founded in Santa Fe in 1760, was largely composed of members of Santa Fe's Spanish nobility. The confraternity owned a private chapel, which by eighteenth-century standards was the most ornate in town, and had furnishings that were considered sumptuous, rich vestuaries, and a large endowment of land and livestock. On the feast days that commemorated Our Lady of Light's conception, purification, nativity, and assumption, her devotees carried her bejeweled image through the streets of Santa Fe accompanied by the royal garrison firing salvos, and ending in celebrations marked with dances, dramas, and bullfights.[12]

Symbolically counterpoised to the co-brothers of Our Lady of Light were the Brothers of Darkness, whose devotion was to Christ's passion and death. The members of the Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene were primarily genízaros. The Brothers of Darkness displayed their piety through acts of mortification, flagellation, cross-bearing, and the Good Friday crucifixion of one of its members. "The body of this Order is composed of mem-

bers so dry that all its juice consists chiefly of misfortunes," wrote Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez, describing the confraternity's poverty in 1776. They had neither membership records, accounts, nor an endowment, and frequently had to borrow ceremonial paraphernalia from other confraternities for their services.[13]

Between 1693 and 1846, approximately 3,500 Indians slaves entered New Mexican households as domestic servants, captured as prisoners of a "just war."[14] As defeated enemies living in Spanish towns, these slaves were considered permanent outsiders who had to submit to the moral and cultural superiority of their conquerors. In addition to these slaves captured in warfare, throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries New Mexico's slave population swelled to about ten thousand, out of a total Spanish population of thirty thousand, through the purchase of Indian slaves from the Apaches and Comanches, and through the incorporation into New Mexican villages of Pueblo Indian outcasts from their native towns.[15]

Genízaro slaves residing in Spanish households and towns were convenient targets for Spanish racial hatreds. As captives and outcasts, the genízaros were considered infamous, dishonored, and socially and symbolically dead in the eyes of the Christian community. Though they lived in Christian households, they lacked genealogical ties to a kinship group, and had legal personalities primarily through their owners. The only public form of sociability open to them to express their common plight as slaves, and eventually to express their ethnic solidarity, were the confraternity rituals of the Catholic Church, which bound them as co-brothers in the mystical body of Christ.[16]

With only few notable exceptions, scholars in the past have usually depicted the Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno in a rather static and timeless fashion. The documentary and material evidence clearly suggests various periods of development, transformation, and florescence, periods that are never easy to establish with precision and can only be considered rough approximations.

The confraternity's first period, difficult to recuperate given the paucity of oral and historical sources, begins with the colonization of the Kingdom of New Mexico in 1598 and extends roughly into the 1790s. Many of the ritual forms of the fraternidad were undoubtedly introduced in New Mexico by the Franciscan friars as part of their project to Christianize the indigenous population. Given the fear that the Franciscans had of imparting heretical understandings of the sacraments to the Indians, their Christianization project became that of teaching through paraliturgies, rites of sowing and harvest, didactic dramas, devotional practices tied to cosmological phenomena, and various Franciscan devotions to the Crucified Christ, such as the Way of the Cross. The cross was a symbol that many Indians had long

given special importance in their iconography, albeit because it represented the six directions of the cosmos. Ritual flagellation too was commonly practiced by Mesoamerican Indians as a purificatory rite for contact with the sacred.[17] What occurred in colonial New Mexico under the rubric of Christianization was a process of cultural convergence between two systems of ritual practice; Franciscan Holy Week rituals substituted well for the Indians' warfare and masculine rituals of power, which under Spanish rule were prohibited. Historian William B. Taylor maintains that the great continuity and convergence between Christianity and Mesoamerican religions was in the ways of representing religious power, in the ways of conjuring the supernatural, in the substances that were deemed holy and polluting, in the ways of creating and entering sacred spaces, and in the ways of anchoring and linking the natural and supernatural to very specific localities.[18]

The laws regulating slavery in New Mexico stipulated that thralls could only be kept in bondage for a period of ten to twenty years. In many cases slaves were freed upon a master's death.[19] The manumission of slaves in New Mexican society produced a peculiar problem in terms of symbolic logic. How could a person considered socially dead and dangerous be given life again as a free and integral member of the community of Christians? The solution was to negate the negation of life—that is, to negate the slave's social death through a second ritual death.

I have long suspected that the rituals of the hermandad were initially rituals of slave manumission; and here I am offering nothing more than an educated hunch. The theology of Christ's crucifixion was a particularly appropriate metaphor for manumission as a death to the state of human bondage, for in it were the ideas of death and renewal. Just as Christ had died because of our slavery to sin and so had given us eternal life anew, so too the genízaro slave's social death was negated through a ritual death, bringing the person back to life. Christ's death brought us redemption. The word "redemption" means to ransom one from the bondage of slavery through the martyrdom of a sacrificial victim. Similarly, through Christ's death we atoned for our sins, and those separated by sin were brought back together. Here again, genízaros, who were outsiders and intruders in Spanish society, were reintegrated into the community.[20] The crucifixion of Christ theologically represented a series of status elevations that paralleled the status changes that accompanied a genízaro's manumission: from spiritual slavery to freedom, from spiritual death to life, from social separation to social integration.

The rather fragmentary evidence seems to suggest that in the community's religious division of labor, the Franciscan friars localized the need for corporal penance on the genízaros, thereby gaining the genízaros' redemption from sin and their reincorporation into the community through manumission. Much of the symbolism of the Hermanos Penitentes' ritual is one of status elevation; being led out of darkness to the light, brothers of dark-

ness in time become brothers of light. Here again we have the Franciscan mystical formula for spiritual perfection. One kills the body to have mystical union with the father of light. Physical purgation prepares the soul for illumination, which, in turn, readies the soul for its mystical marriage with Christ.[21]

A clearly distinct second period for the confraternity dates from approximately 1790 to the 1820s. In these years genízaros in New Mexico develop as a distinct ethnic group. Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez noted in 1776, "Although the genízaros are servants among our people they are not fluent in speaking or understanding Castilian perfectly, for however much they may talk or learn the language, they do not wholly understand it or speak it without twisting it somewhat."[22] Fray Carlos Delgado observed in 1744 that the genízaros "live in great unity as if they were a nation." Delgado added that genízaros practiced marriage-class endogamy for "they marry women of their own status and nature."[23]

Genízaros were stigmatized by their slave and ex-slave status. Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez reported that genízaros were "weak, gamblers, liars, cheats and petty thieves."[24] When New Mexicans today say "No seas genízaro" (Don't be a genízaro), they mean, don't be a liar.[25]

The threat Hispanos felt at having increasing numbers of members of the enemy group living within their towns led to the residential segregation and spatial marginalization of genízaros. In Santa Fe the genízaros lived in the Analco district, situated strategically across the Santa Fe River in a suburb established to protect the town's eastern approach from Apache attacks. By the mid-eighteenth century, manumitted genízaros were congregated into settlements along Apache, Navajo, and Comanche raiding routes into the settlements of the Rio Grande drainage. Belén and Tomé were established in 1740 to protect the southern approach, Abiquiu and Ojo Caliente both were founded in 1754 to protect the northwest, and San Miguel del Vado in 1794 to protect the northeast.[26]

By around 1790, genízaros were perceived as a distinct ethnic group. Spanish society viewed them as marginal persons because of their slave and former slave status. They spoke a distinctive form of Spanish, married endogamously, and shared a corporate identity, living together as if they were a nation. And their liminality between the world of the Pueblo Indians and that of the Spaniards was marked through residential segregation and congregation in autonomous settlements. Membership in the Pious Confraternity of Our LordJesus Nazarene became an expression of ethnic solidarity. The position of this confraternity in the Church's horizontal system of pious organizations reflected their place at the bottom of the social order.

The third period of the confraternity's history roughly begins in the 1820s and continues with some modifications to the present. What is unique about this period is the confraternity's evolution into autonomous political and

economic organizations, which were eventually repudiated by the Catholic Church hierarchy. In the early years of this period we increasingly see the nominal Christian veneer in the ritual and ideological system of the hermandad being supplanted by cosmological beliefs and practices, as well as the development of the confraternity into a civic political body.[27]

The first change observed in this movement toward political autonomy is the redefinition of the confraternity's sacral topography. Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez in 1776 reported that there were separate altars to Jesus Nazarene in the churches at Santa Fe, Santa Cruz, Albuquerque, Tomé, and Abiquiu.[28] By 1814 the altar at Santa Fe's parroquia (parish) was replaced by a free-standing chapel in the church's courtyard.[29] And by 1821 this chapel had been moved off church land and established as an independent morada, or penitente chapel, on private property.[30] These moradas were maintained by the confraternity without any form of ecclesiastical supervision.

Starting in 1836, the Bishop of Durango (in charge of New Mexico until 1848), continually tried to assert his authority over the confraternity by imposing the rule of the Third Order of St. Francis. The bishop's hope was to regain control over branches of the confraternity that were increasingly aloof to clerical supervision, or so he asserted.[31] In 1830 José de la Peña expressed succinctly why the Church hierarchy found the Hermanos Penitentes so subversive. Peña wrote: "They have a constitution somewhat resembling that of the Third Order, but entirely suited to their own political views. In fact, they have but self-constituted superiors and as a group do as they please."[32] Fifty years later, in 1888, Jean Baptiste Salpointe, Archbishop of Santa Fe Archdiocese, similarly observed: "This society, though perhaps legitimate and religious in its beginning, has so greatly degenerated many years ago that it has no longer fixed rules, but is governed in everything according to the pleasure of the director of every locality; and in many cases it is nothing else but a political society."[33]

Archbishop Salpointe was quite correct in seeing the confraternity as the corporate political body of genízaro communities. The ritual leader of the confraternity, the hermano mayor or the "eldest brother," was also quite frequently the town's civic leader. He administered justice, managed the locality's economic resources, and cared for the social welfare needs of the place. Of course, one should not minimize the organization's religious functions, which continued to thrive, particularly after the secularization of New Mexico's Franciscan missions between 1830 and 1850. Devoid of priest and access to the sacraments, the Hermanos Penitentes elaborated and evolved their own rites and routes to the sacred. According to anthropologist Munro Edmonson, the ritual calendar in genízaro villages did not correspond to the Christian one.[34] The themes articulated in the alabados, the penitential hymns members of the brotherhood chanted in their rites, also changed

over time. Rather than the themes of death and darkness as a way to salvation, metaphors and symbols of illumination, which in American Indian religious thought signify utopia, started to figure more prominently.[35] Similarly, the first report of a man actually dying on the cross on Good Friday comes from the 1890s.[36] The mystery and legitimacy of Christianity comes from the fact that Christ descended to earth and was crucified for the sins of humanity. In the absence of priests, might the crucifixion of a Penitente similarly have given legitimacy to the confraternity's devotions and served as a symbol for their own resistance to outside domination? Perhaps.

What we do know for sure is that in the late 1880s and 1890s knowledge of the Hermanos Penitentes was widely disseminated throughout the United States to a broad reading public. The development of an integrated national market criss-crossed by railways and highways, and interpolated by print journalism, made it at last possible to imagine the nation on a continental scale and to travel to its remotest corners to see the odd customs of its exotics and view the most picturesque scenes imaginable.[37] American nationalism produced and fed both the production and consumption of travel literature, and ultimately the touristic marketing of New Mexico.[38]

At the end of the nineteenth century many luminaries, writers, artists, alienated intellectuals and social misfits came to New Mexico seeking a salubrious refuge from the machine age. In the quaint villages of what was to become the "Land of Enchantment" and in its prehistoric sites was a preindustrial America, a vestige from the past that offered mystical and romantic repose.

Charles Fletcher Lummis, the man who coined the slogan "See America First," was the individual most responsible for the initial marketing of New Mexico's cultures. It was Lummis who constructed the Pious Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene as the savage and fanatic "Penitent Brothers" for the Anglo touristic gaze, simultaneously fixing for his readers the most enduring Anglo-American representations of the Pueblo Indians, the Navajo, the Apache, and especially of the New Mexican landscape.

Lummis came to New Mexico and the American West in 1881, seeking a cure for the "brain fever" he had developed at Harvard preparing for the ministry. In the West he found health and the city editorship of the Los Angeles Times, and it was from there, with extended forays to New Mexico, that he penned and preached about the corruption and decadence of Anglo-Saxon New England and the vigor and salubrity of the multi-ethnic West.[39] Writing such well received and popular books as A New Mexico David (1891), Pueblo Indian Folk Tales (1891), A Tramp Across the Continent (1892), Some Strange Corners of Our Country (1892), The Land of Poco Tiempo (1893), The Spanish Pioneers (1893), The Enchanted Burro ( 1897), and The King of the Broncos (1897), Lummis took his readers on an "orientalist" adventure to New

Mexico through fantasies and hallucinations of Egypt, Babylon, Assyria, and deepest, darkest Africa.[40] In The Land of Poco Tiempo Lummis writes:

The brown or gray adobe hamlets [of New Mexico] . . . the strange terraced towns . . . the abrupt mountains, the echoing, rock-walled cañons, the sunburnt mesas, the streams bankrupt by their own shylock sands, the gaunt, brown, treeless plains, the ardent sky, all harmonize with unearthly unanimity. . . . It is a land of quaint, swart faces, of Oriental dress and unspelled speech; a land where distance is lost, and eye is a liar; a land of ineffable lights and sudden shadows; of polytheism and superstition, where the rattlesnake is a demigod, and the cigarette a means of grace, and where Christians mangle and crucify themselves—the heart of Africa beating against the ribs of the Rockies. (4–5)

In chapter after chapter, in description after description, New Mexico was Egypt. Describing the unique light on New Mexico, Lummis wrote: "Under that ineffable alchemy of the sky, mud turns ethereal, and the desert is a revelation. It is Egypt, with every rock a sphinx, every peak a pyramid" (9). The residents of Acoma Pueblo were "plain, industrious farmers, strongly Egyptian in their methods" (69). The Indian pueblos at Taos, Zuni, and Acoma, had been built in the shape of "pyramid" blocks (51–52). Pueblo girls cloaked themselves in "modest, artistic Oriental dress" (53). The Indian pony-tail was "The Egyptian queue in which both sexes dress their hair" ( 111). In the wind-eroded sand sculpture of the desert, Lummis saw an "insistent suggestion of Assyrian sculpture. . . . One might fancy it a giant Babylon" (61). The Apache were the "Bedouin of the New World," and the land they inhabited, a "Sahara, thirsty as death on the battlefield" (175–76). The Penitent Brothers whipped themselves like "the ancient Egyptians flogged themselves in honor of Isis" (80).

When Lummis described New Mexico as Egypt and employed Orientalist tropes, he was mimicking what was standard fare in Anglo-American travel writing from the eighteenth century forward. Such images were employed to give readers unfamiliar with a particular place some readily identifiable imaginary markers drawn from their own colonial histories, from travels to the Holy Land by their compatriots, and from their own readings of the Bible.[41] But equally important, writes Mary Louise Pratt, Egypt offered "one powerful model for the archeological rediscovery of America. There, too, Europeans were reconstructing a lost history through, and as, 'rediscovered' monuments and ruins." By reviving indigenous history and culture as archaeology, the locals who occupied those sites were being revived as dead.[42]

What evoked the sights, sounds and smells of Egypt in New Mexico for Lummis were the women who carried clay water jars on their heads, the cool mud (adobe) houses that dotted the landscape, the donkey beasts of bur-

den, the two-wheeled carts, the desert sun, light, and heat, and the presence of sedentary and nomadic "primitives" amidst the ruins and abandoned architectural vestiges of former grand civilizations.

Lummis introduced the Penitent Brothers in The Land of Poco Tiempo, noting:

[S] o late as 1891 a procession of flagellants took place within the limits of the United States. A procession in which voters of this Republic shredded their naked backs with savage whips, staggered beneath huge crosses, and hugged the maddening needles of the cactus; a procession which culminated in the flesh-and-blood crucifixion of an unworthy representative of the Redeemer. Nor was this an isolated horror. Every Good Friday, for many generations, it has been a staple custom to hold these barbarous rites in parts of New Mexico. (79)

Lummis asserted that the brotherhood consisted largely of "petty larcenists, horse-thieves, and assassins" (106). The brotherhood was widely feared because it controlled political power in northern New Mexico. "No one likes—and few dare—to offend them; and there have been men of liberal education who have joined them to gain political influence" (106), Lummis attested.

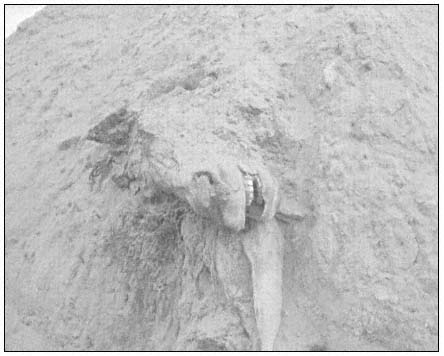

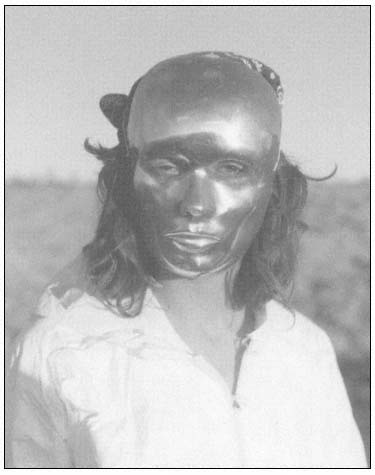

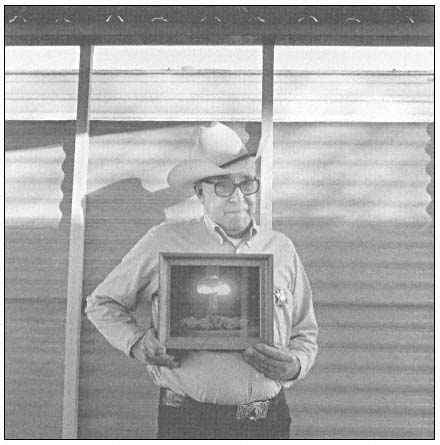

The Penitente discourse Charles Lummis constructed was followed almost verbatim by most Anglo-American writers who described the brotherhood from 1890 on. The gaze he focused on the flagellation, the bloodletting, the use of cacti for mortification, the shrill of the pito, and the nature and extent of crucifixion framed numerous "eye-witness" accounts that are difficult to accept as such primarily because the descriptions so closely ape those written by Lummis. Lummis took the first, and one of the only, sets of photographs of a Penitente procession and crucifixion, and this visual record may also account for the linguistic framing of what subsequent "outsiders" saw.

Interestingly, Lummis narrates the taking of these photographs as if on a safari hunting large game animals with his camera as his gun. "Woe to him if in seeing he shall be seen. . . . But let him stalk his game, and with safety to his own hide he may see havoc to the hides of others" (85). Lummis recounts how he waited anxiously for Holy Week to arrive so that he could photograph the impossible—the Penitentes. "No photographer has ever caught the Penitentes with his sun-lasso, and I was assured of death in various unattractive forms at the first hint of an attempt" (87). But on hearing the shrill of the pito, his prudence gave way to enthusiasm and he set himself up waiting for what he called the "shot." Though the Hermanos protested, "well-armed friends . . . held back the evil-faced mob, with the instantaneous plates were being snapped at the strange scene below" (91).

Photographs of this barbaric rite were necessary, explained Lummis, because Mexicans were "fast losing their pictorial possibilities" (8–9). What Lummis failed to explain, but what did not elude the diary of Adolph Bandelier, was that Lummis and Amado Chaves had held up the Hermanos at gun point, to get these "shots."

The political subtext of Lummis's Penitente photographs and textual descriptions was a critique of New Mexican despotism and of religious fanaticism that had no place in a republic governed by Anglo Protestants. Like the Israelites who had been led out of the darkness and idolatry of their Egyptian captivity, so too the peoples of New Mexico had to be freed from their "paganism" (read Roman Catholicism) (5).

What Lummis did by hunting Penitentes, cunningly stalking his prey like game animals, trying to capture on film that which was sacred, was to begin the process of desacralization that was to mark the history of the Hermanos and their Fraternidad from 1888 to the 1950s. The Good Friday rituals of the Hermanos at the turn of the century became touristic spectacles for Anglo New Mexicans. According to Gabriel Melendez, it was not uncommon for outsiders to sit in their cars waiting for the Hermanos to emerge from their moradas. As soon as they did, a flood of auto headlights would illuminate their activities.[43]

Once the rituals and processions of the fraternidad had been desacralized, their religious icons and statues soon suffered a similar fate. Mabel Dodge Luhan, in her autobiography, Edge of Taos Desert: An Escape to Reality, recounts how she and her friend Andrew Dasburg created the market for the religious icons that had once adorned moradas.

Andrew had started hunting, an instinct that awakened in him every once in a while, made him breathless, eyes darkened, fully engaged. He hunted the old Santos painted on hand-hewn boards that we had discovered soon after we came to Taos. No one had ever noticed them except to laugh, but here was an authentic primitive art, quite unexploited. We were, I do believe, the first people who ever bought them from the Mexicans, and they were so used to them and valued them so little, they sold them to us for small sums, varying from a quarter to a dollar; on a rare occasion, a finer specimen brought a dollar and a half, but this was infrequent. . . . Andrew was soon absorbed in sainthunting. . . . he went all around the valley looking for them. He became ruthless and determined, and he bullied the simple Mexicans into selling their saints, sometimes when they didn't want to. He grew more and more excited by the chase, so that the hunt thrilled him more than what he found; and he always needed more money to buy new Santos. . . . It was Andrew who started a market for them, and people began to want them and buy them; and I was always giving one or two away to friends who took them east where they looked forlorn and insignificant in sophisticated houses. People always thought they wanted them, though, and soon the stores had a demand for

them. Stephen Bourgeois finally had a fine exhibition of them in his gallery. All this makes them cost seventy-five, a hundred, or two hundred dollars today.[44]

The bultos, santos, and the various religious icons and statues that adorned home altars and moradas slowly were commercialized, deconsecrated, robbed, and placed on display in museums.

A class of alienated Anglo-American intellectuals, writers, artists, and financiers packed their belongings and headed to northern New Mexico at the end of the nineteenth century and in increasing numbers after World War I. They came rejecting the tastes, aspirations, and pretensions of the "Blue Bloods" who mimicked European aristocracy. And by so doing they started to imagine a national culture that was rooted, not in Europe, but on this continent in the cultures of New Mexico.[45]

The preservation of the simple authentic cultures these easterners found in New Mexico, and their implicit critique of the industrial age, was clear in such acts as the 1925 creation of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society by Mary Austin and Frank Applegate. They aestheticized religious expressions and revalorized colonial artifacts as commercial art best enjoyed by connoisseurs. The process of appropriation reached its greatest extreme when the Santuario de Chimayo, the religious pilgrimage site in northern New Mexico, was purchased by the Spanish Colonial Arts Society in 1929 in order to protect it from the local ignorant folk.

In Spanish colonial art products, in religious icons and handicrafts, Anglos imagined the possibility and romance of non-alienating labor. Such artifacts were not mass-produced and appeared to stand frozen in isolation, defying the principles of global capitalism.[46] Mabel Dodge Luhan captured this flight from modernity to the cultural pluralism (read classless society) of New Mexico well when she instructed her son, "Remember, it is ugly in America. . . . we have left everything worthwhile behind us. America is all machinery and money-making and factories . . . ugly, ugly, ugly."[47]

A whole generation of Anglo-Americans, under the influence of piedpiper Charles Fletcher Lummis, were lured to New Mexico hoping there to resist industrial capital, to preserve the quaint picturesque cultures they found, and to market Pueblo and Hispano handicrafts as an authentic American art that offered a solution to national alienation. We see these sentiments expressed very well in the very first page of Roland F. Dickey's New Mexico Village Arts ( 1949). "This book does not recount famous names and urbane schools of art. It tells of ordinary men and women who worked with their hands to create a satisfying way of life in the Spanish villages of New Mexico." Waxing lyrical for over two hundred pages, Dickey concludes: "Today it is possible to escape from the commonplaceness of the machine world by furnishing an adobe house in what is reputed to be the Hispanic manner. . . . Beautiful things made by hand provide a relief from the systematic lines

and textures of machine manufacture, and keep awake sensitivities that are dulled by standardization."[48]

The fraternidad responded to the commercialization of their religious expressions and to their transformation into safari tour spectacles by going underground, seeking anonymity, placing a premium on secrecy, and eventually retreating into New Mexico's hinterlands. There they developed a deep spiritual and mystical sense of community. In interviews, conversations, and a recent conference on the Penitent Brotherhood, the Hermanos have consistently noted that the essence of the brotherhood is mysticism and faith. Hermano Larry Torres of Taos recently stated that to be an Hermano was to devote one's life to prayer, penitence, and sacrifice. Torres cited the Song of Songs and the life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux as his two models for reaching spiritual perfection. The two alabados, or prayers that captured the nature of his faith, were: Un ardiente deseo, which tells of lovers yearning for the beloved and the sweetness of their embrace, and Por ser mi divina luz, which describes how Christ is the beacon leading one from darkness to the light.[49] Hermano Floyd Trujillo described his duties and commitments as follows: "When one becomes an hermano it is like the bond of sacred matrimony. . . . we know the role we accept and, like Christ, we take the cross and follow him. We help the people. We help those that need help. . . . We never say no. We see the needs of the community and we take care of them. We are the leaders of the community."[50]

The Hermanos take this leadership role very seriously. Hermano Gabriel Melendez has explained that the role of the hermano is that of a mediator who makes reconciliation possible. To mediate conflicts between Hermanos, between husbands and wives, between the Church and the Brotherhood, between the saints and the local morada. It is only through such activities of mediation that social peace and reconciliation can occur.[51]

One of the most eloquent members of the hermandad, Felipe Ortega, the master of novices at La Madera, New Mexico, clearly sees the fraternidad and the morada as an anti-hierarchical organization and sacred space for the experience of Christ and the community, that stands outside and in juxtaposition to the Catholic Church. Ortega notes that when members of a morada sing their penitential hymns or alabados in a cantor/response mode, a "unison is created, one spirit, one mind, one heart." Within the morada, people stand facing each other, rather than oriented toward a priest and altar, further inscribing the egalitarian sense of community among morada members. And when the Hermanos come together to celebrate rituals, they in fact create the very sacraments. For when the Hermanos sing "Venid. Venid. Venid a la mesa divina" (Come. Come. Come to the divine table), members of the brotherhood are called to feed their souls and their bodies in a common union, at a veritable communion, through the sharing of food.[52]

I realize that this essay is both tentative and speculative, and perhaps devoid of the chronological precision one commonly finds in historical tracts. My main theoretical concern in this research has been to understand the dynamics of cultural systems of reckoning and relatedness that are imagined and spoken with the same language we use to describe biogenetic ties, but which are often deemed "fictive." Since the late nineteenth century our anthropological and historical understanding of kinship has been dominated by studies of kinship terms, componential analysis, and household structures. Simply knowing who is biologically related to whom, who co-resides, and who gave birth to whom tells us very little about how relationships are imagined and kinship obligations animated in any society. Kinship theory has been too tightly constrained by our own modern preoccupation with biology and the salience of biogenetic principles of descent. If we are to understand the meaning of kinship in the early modern period, we have to approach the topic culturally, sketching the parameter of thought by studying prescriptive literature and then exploring instances where thought was concretely negotiated in practice. Herein I have tried to show how Indian slaves or genízaros, individuals who had no kinship ties to the community of Christians in New Mexico, forged ties of affinity through the Catholic Church's structure of confraternities that were just as real, important, and vibrant as any biological link ever has been or can be.

My second explicit aim has been to focus intensively on religious thought and expression as a window into local politics. Perhaps because we live in a secular age, we often relegate religion and its rituals to the domain of magic and superstition. I have tried to show that if one is going to take politics seriously in the early modern period and to study the origins of political forms, one has to turn to religion, the idiom through which politics was expressed until quite recently. One cannot, for example, understand the appeal of the New Mexican 1960s land radical, Reyes López Tijerina, unless one understands the religious qua political organization of the villagers to whom he was appealing for help in reclaiming lands fraudulently stolen from Hispano villages in the 1850s. Reyes was the king, and he took New Mexicans, who prior to the 1960s had lived in darkness, into the light.[53]

Finally, the Hermanos Penitentes teach us how deeply notions of ethnicity and kinship are intertwined. Whether one is a child of Abraham (as a Jew), a child of Malinche (as a Chicano), or a brother of Jesus Christ (as a genízaro), ethnic identity is tied to cultural conceptions of family. At a time when our civic fabric seems frayed beyond repair, when women are reinscribed as subordinates in patriarchal thinking, and single mothers are seen as pathologies in the body politic, we must reinvent new models of relatedness, based not on hierarchy but on egalitarian principles. This is the model for a better tomorrow that I think the Pious Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus Nazarene offers us all.

15—

"Pongo Mi Demanda":

Challenging Patriarchy in Mexican Los Angeles, 1830-1850

Miroslava Chavez

In 1850, Gregoria Romero went before the Los Angeles justice of the peace to ask that criminal charges be filed against her husband Manuel Valencia for abusing her physically and verbally. He "gives me a mala vida, " she told the judge, "mistreats me with beatings, defames me, . . . threatens me with death at every step, denies me indispensable nourishment, . . . and instead of giving good advice and sustenance as a husband should do, he gives me a distressing and miserable life. I request a separation." The judge took the case under submission, but before he could render a decision, Romero reappeared in court two days later with her husband at her side. "My husband has promised me that, in the future, he will treat me well and provide me with the considerations a wife deserves," she stated. "I retract my [criminal] charge, forgiving the mistreatment he has previously inflicted." Romero's husband affirmed that he had changed his ways. "Never, for my part, will there be cause for fights," he declared, "nor anger between us." He promised to "follow a straight path and subject [him] self to scrutiny by the civil authorities." The judge, already predisposed to salvaging marriages, agreed to Romero's request and dropped the charges against her husband.[1]

By going to the judge with her complaint Romero had boldly indicated her unwillingness to tolerate her husband's repeated abuses. However, by later recanting her charges solely on his promise to reform, she revealed not only faith in the sincerity of her husband's pledges but also Mexican society's high regard for the inviolability of marriage and the husband's place as master of the home.[2] Mexican and, earlier, Spanish legal and social norms were steeped in patriarchal ideology that recognized men as the heads of the households to whom wives and children owed their obedience. Those same norms also placed restrictions and responsibilities on men: they had to provide food, clothing, and shelter for their families and were forbidden to use

excessive force in guiding and instructing their wives, children, and household servants. The Los Angeles court records, as in the case of Gregoria Romero, reveal that men sometimes abused their authority, and women, when necessary, invoked the law to protect themselves and check errant husbands and fathers. The records also indicate that justice could elude women and that the courts often interpreted the law in ways that reflected deeply rooted gender biases.

In exploring women's experiences with the judicial system in Mexican California, this study relies on extant civil and criminal court cases that came before Los Angeles's Court of First Instance between 1830 and 1850. Though the tribunal existed prior to 1830, no earlier records have survived. In 1850 the court ceased to exist as a result of the ratification of California's state constitution and the introduction of the American court system. These records, which total 502 court cases, include 78 cases involving women in civil and criminal matters.[3] Of these, 47 have been selected for study because they reflect the ways in which women of different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds dealt with husbands, fathers, and men in the larger community who violated their authority by physically abusing them, neglecting to provide for them, or unlawfully coercing them. These cases also illustrate how local leaders handled individuals who transgressed standards of propriety. Cases involving women's property disputes and other civil matters, while equally significant in elucidating their experiences with patriarchy in Los Angeles, are not treated in this discussion because of space limitations and because they deserve a paper of their own. The focus here is on those women who appeared in the civil and criminal conciliation courts (usually as the plaintiff but sometimes as the defendant). Though these women constitute a distinct minority (approximately 9 percent of the 665 women who resided in Los Angeles during the 1830s and 1840s), they represent a crosssection of gente de razón (non-Indian) women (500) and Indian adult females (165).[4] They include married, widowed, and single women from impoverished, middling, and elite backgrounds.

Though recent historians have greatly enriched our understanding of the daily lives of women in Spanish and Mexican California, none has utilized court records with their abundance of first-person testimonies from women.[5] Scholars have, with success, drawn on the narratives collected by Hubert Howe Bancroft and his assistants, but these accounts describe events long after they occurred and lack the immediacy of oral testimony describing life as it was being lived.[6]

Drawing on sources such as court cases, which focus on adversarial relations, clearly skews our view of male and female interactions, and may suggest an inclination for men and women to engage in violent confrontations. Placing the material within its proper cultural context, however, allows for a more nuanced understanding of how and why gender relations

turned sour as well as the ways in which the community handled such strife. And, more importantly, the evidence reveals not only women's anxieties, expectations, and attitudes but also how women of different circumstances—gente de razón (non-Indians or, literally, "people of reason"), neófitos (baptized California Indians), and gentiles (unbaptized California Indians) fared in the legal system and in the broader society.[7]

The discussion that follows begins with an examination of the gente de razón's understanding of marriage and the family, and then shows how women used local institutions to deal with heads of households who exceeded their paternal authority. The principal reasons women went to court—physical abuse, inadequate support, adultery, and unlawful coercion—receive close attention here. The essay also explores how women of different ethnicities and socioeconomic levels contended with men in the larger community who abused them, and the ways in which men responded to women's grievances. Finally, the discussion analyzes women's use of extralegal means to escape their troubled households, and shows how figures of authority sought to maintain their power.

Mexicans inherited from Spain strong convictions about the centrality of marriage and the family to the survival of civilized Catholic society. These convictions seemed self-evident to the residents of Los Angeles, a precarious and small community on the northern frontier whose gente de razón and Indian populations together barely numbered 2,300 as late as 1844.[8] At the most elemental level, stable marriages and families produced the children who would secure the future and also ensure continuity in cultural and moral values as well as in the inheritance and transfer of property.[9] To the clergy, marriage was a sacrament, a bond sanctified by Christ for the procreation and education of children as well as companionship. Except through death or a church-sanctioned annulment, marriages, preached the padres, remained indissoluble, even when one spouse was extremely cruel to the other.[10] The clergy, in their goal to keep marriages intact, frequently sought the help of civil authorities and sometimes publicly berated them and went over their heads to higher officials if their support was not forthcoming.

Most local officials lacked formal legal training, but they familiarized themselves with the relevant civil codes on marriage and the family, most of them derived from Spanish laws and decrees.[11] Permeating that law was the widely held tenet of paternal authority (patria potestas ) that came from deep in the Iberian past and was embedded in Las Siete Partidas and Leyes de Toro, thirteenth- and sixteenth-century compilations of law that located familial authority in male heads of household—fathers and husbands—the assumption being that such delegation of power ensured a well-ordered family and stable society. A man had virtually complete authority over his dependents—wife, children, and any servants in the household—who, in turn,

owed him their obedience. Qualifying a man's authority was his obligation to support, protect, and guide his dependents. The law and social mores also required a husband to respect a wife's person, but it conceded him the right to dole out mild punishment—the meaning of which varied with time, locale, and circumstance—to her and his other dependents as a way of guiding or teaching them. The ideal home (casa de honor ) was a place where husband and wife, regardless of socioeconomic status or racial and cultural identity, treated each other well, supported their dependents, practiced their religion, remained faithful to one another, and otherwise set a good example for their children.'[12] Men who abandoned or neglected the well-being of their households or engaged in excessive punishment violated not only the law but also the norms of the community.[13]

As members of the community, women had the right to hold men responsible for neglecting to fulfill their obligations or for exceeding their power and authority as heads of households. To deal with such men, women sometimes felt compelled to turn to the Court of First Instance. Depending on the matter at issue, the tribunal convened a civil or criminal trial in the first court (juzgado primero ), presided over by the alcalde, or a conciliation trial (juicio de concilio ) in the second court (segundojuzgado ), presided over by the justice of the peace, or juez de paz. In particularly violent and abusive relationships, the alcalde—with the consent of the individual issuing the complaint, usually the woman—would order a criminal trial, treating the physical violence in the home as a crime punishable by possible imprisonment or banishment. In matters that involved so-called "light" (leve ) crimes of physical abuse or some other transgression the court considered mild, justices ordered a civil trial or conciliation hearing, in which the aggrieved and defending parties each appointed his or her hombre bueno, or good man, who served as an advisor to the court. The goal of these sessions, which were common throughout Mexico and its possessions, was to reconcile the disputing couple, thus preserving the marriage for the good of the family and social stability.[14] In the case of an unmarried couple living together, the purpose was to separate them.[15] In many instances, women found that these sessions functioned only as "quick fixes" that failed to restrain a consistently violent husband. Women wanting legal separations or annulments usually received a hearing in the civil branch of the court, though the clergy preferred to handle such matters through ecclesiastical channels.

In the criminal, civil, and conciliation courts, women voiced a host of complaints against heads of households. Married women complained about husbands who physically abused them, failed to support them and their children, and otherwise set a bad example in the household. Luisa Domínguez's troubles with her spouse are representative. In 1843, she went to the conciliation court, complaining to the justice of the peace about her husband ángel Pollorena. "My husband's treatment is insufferable," she told

the judge and the hombres buenos. "At every moment he beats me [and] I ask for a separation." To prove how badly she had been abused, she exposed her body to the court, revealing the scars left from the wounds. Pollorena, also present in the court, responded, "my wife is a bad woman." "The fight began after I punished one of her children," he explained, "and, as she has [already] had three children outside of our marriage, she wants to return to the same [behavior]." "I have had two children outside of the marriage," Domínguez admitted, but "now that I am with him he does not support me."

The judge and hombres buenos believed that the marriage could be saved and ordered the couple to attempt a reconciliation. "I agree to reunite with my husband," replied Domínguez, but "with the condition that he treat me well, not punish excessively my children, or give them a bad example." Pollorena accepted her demands, though he, too, set a condition. "I promise to educate the children, comply with my obligations, and forget the past as long as she [is] prudent." To ensure that Pollorena kept his promise to Domínguez, the judge appointed several men to keep close watch over his behavior.[16]

Complaints like those of Luisa Domínguez often accompanied accusations of infidelity from women as well as men. Adultery, which the authorities treated as a criminal act and flagrant threat to marriage and the family, prompted women to appeal to the conciliation court and, if they felt especially wronged, to file civil or criminal charges against their husbands. Sometimes they even asked for the indictment of his accomplice on the grounds that the other woman had provoked the marital troubles. In 1844, Francisca Pérez accused her husband and his lover (amasia ) of adultery, telling the judge that the other woman had "caused my husband's infidelity and refusal to give me sustenance."[17] Marina García likewise informed a judge in 1845 that she had a "bad life with my husband Francisco Limón because of Manuela Villa, who is living" with him.[18] To ensure an end to these relations, wives demanded the banishment of such women. "Having caught my husband in flagrante delicto with Nicolasa Careaga," Marta Reyes told the justice of the peace in 1843, "I ask that [the court] punish him and banish her from the town." When Reyes's husband admitted that he was "at fault" and "put himself at the court's disposal," the judge, with the agreement of the hombres buenos, ordered him to "treat his wife well" and sent Careaga to an undisclosed destination.[19]

A woman's decision to file a formal complaint against her spouse for abuse or adultery did not come quickly or easily. In most instances, women turned to the courts only after a prolonged period of contentious relations. Their testimony is usually filled with numerous examples of earlier abuse. Typical were Ramona Vejar and Luz Figueroa, who, in the criminal court, described years of mistreatment. "My husband Tomás Urquides," Vejar stated to the alcalde in 1842, "hits me because of Dolores Valenzuela

[with whom he] has been living . . . for more than two years. . . . He has hit me so many times with a rope or whatever else he can find that I can not recall the exact number." Witnesses verified Vejar's account and also testified that Urquides had fathered a child with Valenzuela. Urquides admitted knowing Valenzuela but denied having an affair with her. He also acknowledged hitting his wife, though he said he did so in order to correct her insolence. "One day, she came to my mother's house," he informed the court, "looking for someone, and when I asked her what or whom she wanted, she responded, 'I am looking for that [sexually promiscuous woman] who is your friend and your mother who is an alcahueta [a mediator between lovers].' . . . I only hit her when she gives me cause to do so," he insisted, "not because [Valenzuela] tells me to do so; I do so when she neglects the children or leaves without my permission."

When Valenzuela was called to testify and admitted to a long affair with Urquides, the judge moved quickly to end the relationship. He ordered Valenzuela's banishment: she had to live at least ten leagues (thirty-five miles) from the town in a casa de honor where she and her children would be watched. Urquides, on the other hand, received only a reprimand for "correcting" his wife and a fine of ten pesos for his sexual misconduct. Within six months, Vejar was back in court complaining that Urquides had returned to his old habits. "I ran to take shelter [from him] in a nearby home," she told the judge, "but he pulled me out, beat me, and then tied me up with a rope." Before the authorities could apprehend him, Urquides fled from the town, forcing the authorities to drop the case until he could be located.[20]

Like Ramona Vejar, Luz Figueroa experienced years of abuse from her husband, Juan Riera. Figueroa's problems, however, lasted more than a decade, culminating in 1849 with flight from her husband and an appeal for help from the local priest. "What should I do?" she asked him. His response: "return to your husband." Dutifully, she returned to the household only to be beaten again by her husband. This time she turned to the court for help, describing for the judge her husband's years of abuse and his latest attack. He "picked up a leather rope and he struck me once in the face, and did so repeatedly on my back," she stated. "Luckily I was able to escape . . . and found help in a nearby house. But soon my husband found me, and pulled me from the house, dragging me through the streets and telling me to follow him or else he would kill me with the knife he pulled out of his pants." She showed the judge the scars that the many beatings had left on her body. "What [punishment] do you request for your husband for having beaten and publicly humiliated you?" asked the judge. "I request his banishment from this city because I fear that a grave injury may happen to me. He has always given me a miserable life, and in the twelve years I have been married to this man, there have been numerous relapses into his bad habits."[21] The judge ordered the arrest of Riera whom he questioned and then imprisoned

pending a full criminal investigation. What that investigation revealed is unknown, since the surviving records indicate only that Riera was freed but not the reasons why. What is clear was Luz Figueroa's attempt to have him removed from her life.

Women challenged not only abusive and unfaithful husbands but also coercive fathers. Though fewer women issued complaints against fathers than husbands, those who did so frequently won the support of local authorities. In 1842, for instance, Casilda Sepúlveda complained to the judge in the civil court that her father, Enrique Sepúlveda, with the support of her stepmother Matilda Trujillo and the local priest, had forced her to marry Antonio Teodoro Trujillo. She asked the judge "for the protection of the law against such an attack on my personal liberty" and to grant her an annulment. The judge examined witnesses and found that, indeed, she had been married against her will, and he nullified the marriage. The judge then informed the local priest at Mission San Gabriel, Tomás Estenaga, of his actions, prompting Estenaga, in turn, to notify Francisco García Diego y Moreno, the bishop of both Alta and Baja California, about what had occurred. The bishop, convinced that the judge had exceeded his authority by interfering in a religious matter, reacted angrily. "Judging the validity or nullity of marriage is absolutely reserved to the ecclesiastical domain," the bishop wrote to Santiago Argüello, head of the prefectura, or prefecture, the highest civil authority in southern California directly responsible to the governor.[22] Bishop García then ordered Estenaga to speak privately with Sepúlveda and urge her to reconcile with Trujillo. If she refused to do so, then she and her relatives should go to Santa Barbara, the current residence of the bishop, and plead her case before the ecclesiastical tribunal there. At first, she balked at going, preferring to "present her reasons, in writing, to the Bishop," but under the prodding of Father Estenaga, she finally consented to go.

The hearing in Santa Barbara concluded with the bishop announcing that the marriage had been forced and annulling it. Sepúlveda's success in attaining an annulment, a rare occurrence in California and Mexico, was a triumph over paternal authority and her family's insistence that she marry a man whom she had refused as a husband.[23] Her victory, however, did not come without consequences. Shortly after returning to Los Angeles, she was again in court complaining that her father had retaliated against her. "I don't want to return to my father's house," she declared, for "he refuses to support me[,] refuses to recognize me as his daughter[, and] wants to disinherit me. What shall I do?" The judge's response and her long-term relationship with her father and family are unknown, since the record ends abruptly. But even if the alienation from her family was short-lived, it reveals the risk that women in this frontier community took when they challenged patriarchal authority.[24]

Sepúlveda, like all the women who used the courts to challenge male

heads of households, identified herself as a member of the gente de razón. The extant court records involving Indian women—a total of nine cases—provide no instance of a neófita (baptized Indian woman) or gentil (unbaptized Indian woman) bringing a complaint against a spouse or father. Perhaps the neófitas took their complaints against family members to the priests or governors who exercised greater direct authority over their lives than other non-Indians did. Similarly, the gentiles may have avoided the courts in favor of tribal customs when it came to similar problems. The evidence indicates, however, that Indian women did use local institutions in dealing with non-family members, both Mexican and Indian, who committed depredations against them.

Vitalacia, a married Indian woman who resided at San Gabriel Mission, was the only neófita to bring a complaint to the local court, in this case the criminal court. In 1841, she told the judge that Asención Alipas, a Mexican man who was not her husband, had "maimed and cut [her] with a knife." "Last week," she informed the court, "I was at the mission gathering wheat when Lorena [an Indian woman who worked at the mission] informed me that Alipas had arrived." With a knife in hand, he "approached me and in a derisive tone asked, 'why do you no longer want to be with me?' When I told him [again] that I didn't want to be with him anymore, he took the knife and cut my hand and my braid." Alipas told the judge, "I have been having relations with Vitalacia for about four or five years past, and have sacrificed the earnings of my work in supporting her." When "I arrived at . . . the mission . . . I saw a behavior in Vitalacia that I disliked, [and] I became violent and grabbed her, cutting her hair with a knife." The cut on her hand was of her own doing, he insisted. In "trying to take the knife away from me, she grabbed the blade, and because she refused to let go of it, I pulled on it, and she cut her fingers."[25]

What angered the judge was their extramarital relationship. "What do you have to say about using a married woman?" he asked Alipas. "It is true," he responded. "I recognize my crime, but an offended man becomes violent." Puzzled, the judge pressed his inquiry. "What offense did she commit against you; she is not your wife." Alipas attributed his anger to Vitalacia's disregard for her obligations to him, particularly the sexual services that she owed him for his economic support. "She never appreciated that," he stated. The judge was unsympathetic. He found Alipas guilty of adultery and injuring Vitalacia and sentenced him to labor on public works. He urged Vitalacia, whom he also found guilty of adultery, to stay away from Alipas. Vitalacia's case is significant because it reveals that, although occupying a subordinate position in relation to the community of gente de razón, she used the court successfully to extricate herself from the grip of Alipas, whose gender and ethnic status would have normally placed him in a dominant position.

Women, whether neófitas, gentiles, or de razón, often had the assistance of their immediate families when they turned to the courts or other civil or religious authorities in dealing with men in the larger community. At times, family members, especially fathers or brothers, represented the women, particularly in instances of sexual assaults.[26] The socially and politically prominent gente de razón viewed rape not only as a grave offense against a woman's reputation, or honor, but also as a stain on the family's honor. Hispanic law reflected this attitude, as it allowed male family members to kill a perpetrator who was caught in the act of rape.[27] The threat that rape posed to elite females and their families emerged sharply in 1840 in a criminal complaint filed by María Ygnacia Elizalde, wife of the prominent José María Aguilar, a former local government official in Los Angeles who continued to have political influence.[28] She accused Cornelio López with attempting to rape her. "López broke into my house and entered my room," she told the judge, "with the intent of wanting to use my person in the [sexual] act when he saw me alone. . . . With much struggle I managed to resist the force with which he surprised me. [It was not] until Raimundo Alanis arrived that López separated himself from me, giving me the freedom and opportunity to come [to the court] to report this."

The judge ordered a full investigation followed by a trial at which Elizalde repeated her charges. López, she testified, "tried to force me to have a [sexual act] with him, but I absolutely denied him. He told me, 'why do you not want to have relations with me? Have you not already been with others?' But I continued to resist and, eventually, he relented, but only momentarily. At that moment, he looked out the [bedroom] door to see if anyone else was around, and then returned to my bed to try and force me [to have relations]. He remained an hour, after which time he left, no doubt [because] he saw Alanis sitting outside the door. I then proceeded immediately to complain to the authorities so that they would restrain him."

When López took the stand, he denied forcing her to have sex with him. On an earlier occasion, he stated, she had promised to have relations with him, but, now, when he asked her to comply, she refused, causing him to become incensed. Making him even angrier, he declared, was the extramarital affair that she was having with another man, José Avila.

Presenting the case for the prosecution was Elizalde's husband, Aguilar. The court typically either appointed a prosecutor or asked the aggrieved parties to select one, family member or not. And, usually, those selected were socially or politically prominent in the community. "During my absence," Aguilar began, "in which I had to travel to Santa Barbara, Cornelio López took advantage of my wife's solitude, and with a bold move he profaned the home of an honorable citizen." He continued, "on the morning of the nineteenth of the past month, my wife was resting in her bed from her do-

mestic work, when suddenly Cornelio López appeared and, as if possessed with the devil and with the most obscene words, attempted to force my wife to have carnal relations; my wife, who was surprised to see this man, heroically resisted . . . this treacherous man, who . . . attempted to use her for his pleasure." López's attack, he argued, "disregarded the respect that [was] due to the institution of marriage and [that was among] the duties of a man in society." Upset about the effect of the attack on his social standing in the community, Aguilar declared that "López has made me look like a common alcahueta in public . . . and [has] offended my honor." Furthermore, he told the court, López's "immorality" had not only threatened his marriage, but also that of José Avila. To redeem the "offended honor of [my] wife and family," Aguilar asked the court to banish López for five years to the presidio (military garrison) of Sonoma "where work and reclusion," he continued, "will teach him not to commit such excesses and to respect the society in which he lives; and perhaps then he will be an honorable citizen."

The defense, headed by Juan Cristobal Vejar, argued that Elizalde's gender was to blame for López's behavior. "Man is susceptible to the inclinations of the female sex," Vejar argued. "That the defendant approached an honorable woman is not a crime." López's behavior may have been improper but not criminal. On the other hand, acknowledged Vejar, Aguilar had every right to be angry with López, for his anger is "founded on the insult that López caused by approaching his wife and disrespecting her [married] state." But, Vejar emphasized again, an insult is not a crime.

Before rendering a verdict, the judge waited for the authorities in Monterey to convene the first appellate court. Recent legislation, enacted in Mexico in 1837, required verdicts and sentences in criminal courts, including those in California, to be reviewed by a higher court.[29] (Earlier, appeals had gone to the governor.) The Los Angeles judge waited more than two years for creation of the Superior Tribunal, composed of three justices. Following that action, the judge at last rendered a verdict on López, who all the while had been incarcerated, finding him guilty of the attempted rape of Elizalde. "For having wanted to use with violence a married woman . . . I condemn him for the public satisfaction of José María Aguilar so that the honor of this man's wife is free from damage." Since Lépez had been jailed for nearly three years, however, the judge believed he had served his sentence and so he set him free. The case then went on appeal to the Superior Tribunal, which responded with mixed approval to the courtroom proceedings as well as the sentence: "since the [court] proceedings lack the formal prerequisites that are necessary in overseeing personal injury cases . . . and given the time that Cornelio López has suffered in prison, the judge's decision to free López is approved." López deserved freedom, the Superior Tribunal continued, "not because of the [need for] public satisfaction" of

José Maria Aguilar, but because the Los Angeles judge had committed a procedural error that mandated López's release. To the tribunal in Monterey, the law took precedence over redeeming the honor of Aguilar and Elizalde.[30]

While sexual assaults by Mexican men on Mexican women were considered an affront to the honor of the women and their families, similar attacks on unbaptized Indian women brought dishonor only to the Mexican men and their relatives. Indian women were seen as lesser beings possessing no honor or esteem that could be insulted. This was the message of a rape case involving an Indian woman in 1844. That year a gentil named Anacleto accused two Los Angeles residents, Domingo Olivas, an assistant of the court, and Ygnacio Varelas, a friend of Olivas, of raping his wife at their ranchería near San Bernardino. Anacleto filed his charges with the local judge in San Bernardino, José del Carmen Lugo, who gathered additional evidence and then persuaded a Los Angeles judge to hold a criminal hearing at which Lugo presented his findings. According to Anacleto and other witnesses, Lugo informed the judge, the incident occurred shortly after Olivas and Varelas arrived at the rancheria with the intent of taking Anacleto to the court in Los Angeles (for reasons that do not appear in the public record). They found Anacleto, who was blind, and his wife inside their home. The two then "took the woman," Lugo told the judge, "and used her by force, threatening her with a knife and saying they wanted to kill them both." About this time, "some Indians and a Mexican approached" whom Varelas threatened with the knife." When the "men warned Varelas that they were going to inform the local authorities about what had occurred, he fled the scene."[31]

Varelas challenged Lugo's testimony, insisting that he and Olivas had not sexually assaulted the woman. Rather, they had offered her money for sexual relations, and she had consented. When Olivas testified, however, he contradicted Varelas and admitted to the crime which he attributed to drunkenness. Prior to the incident, he and Varelas had drunk aguardiente (locally brewed alcohol) that blurred their senses and led to the "lewd acts." He begged that the crime not be made public. "In view of my remorse and frank confession, please consider that I am married and have children, and I live in good harmony with my family. Therefore, I ask and beg you that this situation not be made public." He also pleaded with the judge for "a punishment that is prudent and discreet."

The judge was moved by Olivas's appeal. "The confession and guilt of Olivas and Varelas have been established," the judge ruled. "The former has violated a woman by force and the latter was his accomplice. I should condemn Olivas to service in public works," he declared, "but in order not to disrupt his marriage [or] . . . harm . . . his minor children . . . I order Olivas to pay a fine of twenty pesos and his accomplice to pay ten." The judge made no effort to compensate the Indian woman for her (or her family's) loss of

honor, nor did he, in fact, make any reference to a dishonored household. He obviously placed greater value on Olivas's public reputation and family life than on the crime committed against a gentil woman or on her reputation. Clearly, gender along with ethnic and class biases influenced the court's decision in this matter. How often the court demonstrated such prejudices is unclear, since the extant records are incomplete and this is the only surviving case illustrating such biases. Further research in other materials, including the legal records of communities elsewhere, should shed additional light on this important issue.

Beyond dispute is the evidence showing that both Mexican women and neófitas devised extralegal means to contend with figures of authority whose abuses were not effectively checked by local authorities. Some women simply fled from violent households. In 1845, María Presentación Navarro, a single Mexican woman, left her home in Los Angeles because she feared the wrath of her angry father. Earlier that year, she and Antonio Reina, a married Indian man who befriended her father and family, had engaged in sexual relations that resulted in her becoming pregnant. Frightened of her father's reaction, she asked Reina to "help me escape from my father's side. . . . I fear that he will kill me." Reina took her to Rosarito in Baja California. Learning of their flight, her father asked the authorities to apprehend them and to punish Reina who, he believed, "has forcibly pulled her away from her family."[32]