2—

Intellectual and Political Ties between Nicole Oresme and Charles V

The Historical and Biographical Context

The relationship between Oresme and his patron provides another context for the Aristotle translations.[1] Although scholars now agree that Oresme was not Charles's childhood preceptor,[2] it seems likely that he served as an informal intellectual adviser. Oresme's early writings in French provide evidence that by the late 1350s he had attracted the prince's attention. Miniatures in manuscripts commissioned by Charles clarify not only his relationship to Oresme but also some of the future king's interests.

Details of Oresme's early life are sparse. He was probably born near Caen sometime in the early 1320s. His name first appears in a document of the University of Paris dated 1348 among the masters of the Norman nation and as a scholarship holder of the College of Navarre. After teaching arts and then theology, he became a master of theology in 1356. Oresme probably studied with Jean Buridan, head of the College of Navarre, which was founded in 1304 by Queen Joan of Navarre, wife of King Philip IV. Buridan, an interpreter of Aristotle, was also an important nominalist and natural philosopher and may have influenced Oresme's thinking.[3] Since Oresme was at the leading center of Aristotelian studies in Europe, he would have been infused with a thorough knowledge of the Philosopher's thought. The first group of Oresme's writings date from the late 1340s to the early 1350s, when Oresme was teaching in the arts faculty. Among these unpublished works are collections of individual questions on selected topics, a method of scholastic argument, six of which concern works of Aristotle. A second group of Oresme's writings in Latin on mathematics and physics addressed to scholarly audiences probably dates from the late 1340s to the early 1360s.

In 1356 Oresme was named Grand Master of the College of Navarre, a royal foundation, around the same time that scholars believe he came to the attention of the royal family. That year marked a low point in the fortunes of the new Valois dynasty that had succeeded the last Capetian king, Charles IV, in 1328. The accession to the French throne of King Philip VI, the first of the Valois line and father of John the Good, had precipitated the Hundred Years' War. At the decisive battle of Poitiers that ended the first phase of the Hundred Years' War, in 1356, King John the Good and the flower of French chivalry were defeated and captured by the English. Leadership of France fell to the Dauphin Charles, eldest son

of John. Only eighteen years old, Charles faced the threat of civil war. Certain aristocratic factions sided with the English claimant to the French throne, King Edward III. Opposition to the Valois dynasty also arose from Charles the Bad of Navarre. His mother, Queen Joan II of Navarre, was the daughter of Louis X, one of the last Capetian kings. But the exclusion of women from inheriting the French throne either directly or passing it to a male heir negated the claims of both Edward III and Charles the Bad.[4]

Other threats to the Valois monarchy came in the late 1350s from a revolt in Paris led by Etienne Marcel, provost of the wool merchants, who allied himself with Charles the Bad. In 1358 the peasant revolt called the Jacquerie broke out. Furthermore, a financial crisis, partly caused by the need to raise the ransom for the captured king, brought cries for monetary reform. The various meetings of the Estates General between 1355 and 1358, summoned to raise money first by John the Good and then by Charles, brought pressure for political and monetary reform of the monarchy. A particular sore point was the king's continued debasement of the coinage. Disaffection with royal power was widespread and extended to members of the faculty of the University of Paris, among them Nicole Oresme. As master of the College of Navarre, he may have been an adherent of the faction supporting Charles the Bad.[5]

Economic Counsel

Under these circumstances of extreme civil unrest, about 1356 or 1357 Oresme wrote the first version of his influential treatise De moneta (On the Debasement of the Coinage),[6] the first medieval treatise on economics. Heated in tone and outspokenly critical, De moneta states that the coinage is not the property of the sovereign but belongs to the entire community.[7] Regulation of it, therefore, is not the prerogative of the monarch alone but of a gathering of the kingdom's inhabitants. Furthermore, the coinage cannot be altered without the consent of the people's representatives. In this treatise, Oresme borrows essential arguments from both the Nicomachean Ethics and the Politics . From the Politics come the distinction between tyranny and monarchy and the warning that power should not be unduly concentrated in any one segment of the community. Oresme's argument that the king's economic powers are subject to regulation by law and custom also derives from the Politics .[8]

Drawing on the authority of these citations from Aristotle, Oresme wrote a second Latin version of De moneta , seemingly in response to the mood of crisis caused by the defeat at Poitiers and John the Good's captivity. Although the tone of the tract is unfriendly to monarchy, the advice offered may have attracted the attention of the Dauphin. In any case, the wording of the reference to a reader in the conclusion of a French translation of De moneta —called the Traictié des monnoies —attributed to Oresme suggests that the vernacular version was addressed to Charles.[9] Although the date of this translation presents problems, the final section suggests that between 1357 and 1360 personal ties existed between Oresme and

the Dauphin.[10] This does not mean that the Traictié des monnoies was necessarily Oresme's first writing in French. Oresme himself named the Livre de divinacions as his earliest work in the vernacular. If, as some scholars propose, this treatise dates from between 1356 and 1357, the Traictié des monnoies could follow it in the last few years of this decade.[11]

In any case, historians generally accept that Oresme's suggestions in the De moneta for reforming the currency were followed in December 1360 by John the Good.[12] Emile Bridrey points out that the language in preambles to a series of royal ordinances dealing with financial policy derives from key terms used by Oresme in De moneta and its French translation.[13]

Another type of evidence confirms Oresme's political and intellectual influence with Charles while he was acting as regent. In 1359 Oresme was secretary of the king and had direct access to members of the royal family, including the sovereign—or in this case, the regent Charles. If commanded to do so by the king, a secretary was entitled to sign acts, and Oresme did so in 1359 (document now lost).[14] Although at this time the rank of secretary was less powerful than in later periods, the holder of this position was nonetheless an intimate officer of the king.[15] Further corroboration of the Dauphin's faith in Nicole Oresme's acumen can be found in a document of 1360. According to Bridrey, in that year Oresme was given the delicate mission of obtaining a substantial loan from the city of Rouen.[16] Oresme's advice to Charles in a period of great crisis forms a practical basis for his relationship with the future king. In this connection, the relevance of Aristotelian ideas advocated by Oresme as a basis for reform constitutes a precedent for his translations of the Ethics and the Politics .

The Question of Astrology

Although little information survives about Charles's formal education, inventories and extant manuscripts from his library indicate that he began collecting books well before his accession to the throne. Lys Ann Shore has found that Charles's library contained more than thirty manuscripts of astronomical and astrological texts in French.[17] In the Middle Ages astrology connoted the study of the celestial bodies both for a rational understanding of the physical nature of the universe and as a pseudo-scientific system to predict the outcome of an individual or collective event. Scholars disagree on which aspect of the subject attracted Charles's attention. In his recent study on Oresme's De causis mirabilium , Bert Hansen takes the position that Charles was predisposed to the irrational side of astrology seen in the king's "official and public commitments to the reality of magic and marvels." As evidence he cites "Charles's patronage of astrologers, his support for the translating, writing, and copying of astrology books, his collection of talismans, and his founding of the College of Master Gervais at the University of Paris for the study of astrology and astrological medicine."[18] By contrast, Charity Cannon Willard believes that Charles's interest in astrology centers on its "investigation of the physical world as part of a single philosophical activity concerned with the search for reality and truth."[19] Willard bases her judgment on the kinds of books Charles

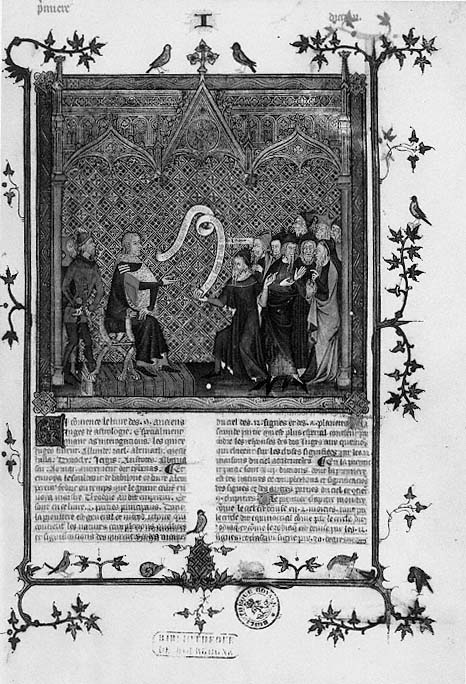

Figure 1

The Future Charles V Disputes with the Nine Judges of Astrology. Le Livre des neuf

anciens juges d'astrologie.

collected, as well as on the description of the king's knowledge of the subject by his biographer, Christine de Pizan.[20]

Christine herself was the daughter of Charles's astrologer, Tommaso de Pizanno, summoned from Bologna in 1365 to serve at the king's court. Before and after he ascended the throne, Charles employed a series of astrologers. Of course, catastrophic events such as the Hundred Years' War and the Black Death obviously encouraged the taste for and belief in astrology. The English called an astrologer, said to have predicted the French defeat at Poitiers, to enliven the captivity of John the Good, while another escorted the king back to France.[21]

Charles commissioned several books on astrology written in French before his accession to the throne, which may shed light on his attitude toward the subject. The earliest of them is Le livre des neuf anciens juges d'astrologie , a translation by Robert Godefroy of the Liber novem judicum . The text is dated to Christmas Eve 1361 by Godefroy, identified in another of the works as the Dauphin's "astronomien."[22] Of particular interest is the unusual frontispiece of the 1361 text (Fig. 1). In Godefroy's absence, the Dauphin addresses Aristotle, the foremost and only identified member of the "neuf anciens juges." The philosopher holds an inscribed banderole that indicates his willingness to answer the questions posed by the prince.[23] The miniature is exceptional not only for its likeness of Charles but also for its depiction of him as the enthusiastic agent of intellectual inquiry. The astrological text contains practical advice on war, pestilence, and dreams drawn from the writings of ancient and Arabic sages.[24] Aristotle's leading role in the frontispiece corresponds to his position in the text, where his authority on celestial matters remains preeminent.

The Dauphin also commissioned two treatises on astrology from another of his household astrologers, Pélerin de Prusse. The first, on the twelve houses of the planets, is dated 11 July 1361; the second, on the astrolobe, 9 May 1362.[25] In the prologue to the first treatise the author refers not only to Charles's insistence on clear writing in French but also to his avid search for instruction on astrological lore that affects rulers. A miniature in a manuscript in St. John's College, Oxford, shows Charles receiving the work from the author while engaged in active dialogue with him (Fig. 2). Although Charles's likeness is conventional, the miniature features a well-organized room furnished for scholarly purposes that corresponds to Christine de Pizan's glowing description of the king's private study.[26] The elaborate horoscopes of the royal family added to the treatise in 1377 attest to the king's lasting interest in the texts of this manuscript.[27] Thus, the first two works commissioned by Charles in the early 1360s show that he viewed astrology as a way to control political events rather than as a disinterested investigation of natural philosophy. Yet the Dauphin's active intellectual engagement with the subject shows him to be capable of developing more theoretical areas of learning.

Charles's enthusiasm for astrology may well have aroused the anxiety of his mentor. Oresme was a fierce opponent of using astrology to predict the future.[28] In general, Oresme disliked the irrational approach of astrology, as he preferred to account for terrestrial phenomena by natural causes rather than by occult celestial

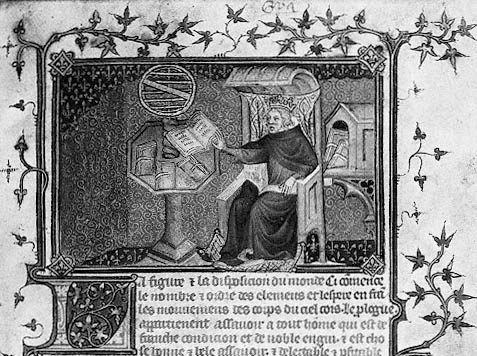

Figure 2

Charles V Receives the Book from Pélerin de Prusse. Nicole Oresme, Traitié de l'espere,

and Pélerin de Prusse, Astrological Treatises.

influence. His theory that celestial motions were incommensurable meant that their configurations would not be repeated. This notion nullifies a basic premise of astrological prediction.[29]

Oresme's French writings on astrology offer concrete examples of the dangers faced by rulers who depended on this form of knowledge. In his Livre de divinacions he addresses "princes and lords to whom appertains the government of the commonwealth." Although not directed to Charles specifically, Oresme gives historical examples of rulers whose reigns ended disastrously because of their attempts to predict the future.[30] He does not totally deny the value of astrology to the ruler but separates its scientific aspects from reliance on divinations and occult practices.[31] Oresme stresses that the most basic form of knowledge for a ruler is the science of politics. Oresme's description of politics as "architectonic" and as the "princess and mistress of all human science"[32] in the prologue of his translation of Aristotle's Politics reveals his pedagogical motivation in translating the Ethics and the Politics conceived in the spirit of Mirror of Princes literature. This educative tone substantiates the tradition that Oresme served as mentor to the Dauphin.

The first translation commissioned from Oresme by Charles also reinforces their close personal and intellectual ties. Not surprisingly, the text is an astrological

Figure 3

The Future Charles V Receives the Book from Nicole Oresme.

Ptolemy, Le Quadripartit.

treatise based on Plato of Tivoli's Latin version of the Quadripartitum of Ptolemy with commentary by Ali ibn Ridwan.[33] Both the attribution and date of the manuscript are controversial. Delachenal's arguments that Nicole Oresme (not his brother the less-known Guillaume Oresme) was the translator are persuasive, as is Clagett's dating of it between 1357 and 1360.[34] Delachenal refers to the ideas and language that later reappear in Oresme's prologues to his translations of the Ethics and the Politics . Among them are the translator's praise of the beauty of the French language and of the royal house for commissioning works in this tongue.[35] Furthermore, in several glosses of the Ethiques and the Politiques Oresme mentions in familiar terms the French version of the text.[36] Reference to "Charles, hoir de France, à present gouverneur du royalme" (Charles, heir to the crown of France, at present regent of the kingdom), seems to limit the date to the return in 1360 of John the Good from captivity in England. Another kind of evidence for attributing the treatise to Nicole Oresme is the tiny illustration at the head of the first column of the prologue (Fig. 3). The style of the miniature confirms an early dating of the text, while its iconography makes it the earliest known example of an informal dedication portrait from Charles's iconography.[37] The appearance of the iconographic type of the intimate presentation portrait testifies to a one-to-

one relationship between prince and author. Charles's mantle, shoulder-length hair, and beard are features repeated incisively in Figure 1. By contrast, the figure of Oresme, who looks squarely at the Dauphin, is far more substantial than that of the wispy prince. The short, chubby portrait type of Oresme is consistent with similar images in the later dedication scenes of his translations of the Ethics and the Politics .

Oresme's favorable comparison of the valiant kings of France to the Roman emperors who had sponsored translations of Greek classics into Latin hints at the theme of the translatio studii . More specifically, Oresme is thinking of John the Good's patronage of Jean de Sy's translation of the Bible and Pierre Bersuire's French version of Livy.[38] The prologue states that, with these precedents in mind, Charles commissioned the present translation of a work that contains the most noble science: astrology that is free of superstition and composed by excellent and accepted philosophers.[39] In other words, Oresme says, this text of the Quadripartitum is an example of the kind of knowledge about the physical world that does honor to the prince and benefits the public good.[40]

Oresme's work of mathematical astronomy, his Traitié de l'espere (On the Sphere), is not specifically addressed to Charles.[41] The concluding chapter, however, mentions that the treatise is intended to be useful knowledge for every man, especially for a prince of noble mind.[42] Oresme is writing for a lay audience, similar to the one mentioned in his version of the Quadripartitum . The copy of the text in the king's library strengthens the hypothesis that Oresme had Charles in mind as a primary reader. In fact, the Traitié de l'espere precedes the treatises by Pélerin de Prusse discussed above. In a miniature from this manuscript, Charles is reading and studying by himself (Fig. 4). Seated in a high-backed chair, he holds one book open on his lap, while he consults another lying on his revolving bookstand. The fleur-de-lis pattern on the walls and floor allude to his rank. Although the portrait is conventional, the image establishes Charles as an active seeker after knowledge. Indeed, the presence of the armillary sphere suggests that Charles is pondering the subjects treated in Oresme's work. Despite certain problems with the date of this manuscript, the text and image of the Traitié de l'espere testify not only to Charles's intellectual character but also to a type of knowledge about the celestial world Oresme considered appropriate for both a layman and a prince.

Certain features of the book emphasize its pedagogical character. Among them is the large historiated initial on folio 2 depicting a scholar (possibly a conventional portrait of the author) pointing at an armillary sphere. Dominating the text is a series of rather crude, but clearly labeled, diagrams explaining basic concepts in the text. The glossary of sixty-eight scientific and technical terms supplied by Oresme also addresses the general, educated reader.[43] The inclusion of Oresme's treatise on acceptable "astronomical" knowledge in the same manuscript as Pélerin de Prusse's astrological works is ironic. The compilation indicates the difficulty of Oresme's task in defining the boundaries of knowledge that he considers beneficial to Charles.

Figure 4

Charles V Studies Astrology. Nicole Oresme, Traitié de l'espere, and Pélerin de Prusse ,

Astrological Treatises.

While the dating of Oresme's early writings is controversial, the motivation for his shift from Latin to the vernacular seems clear. As soon as he developed political ties with Charles and his circle, he found it necessary to express his ideas in French. In order to exert his influence, he had to recast not only his language but also the formulation and compilation of his treatises. These early writings in French provided the model for Oresme's more elaborate and sophisticated translations of the 1370s.

Oresme's Later Career

After Charles's accession to the throne in 1364, Oresme continued to enjoy the confidence of the new sovereign. Two years earlier, Oresme had been appointed canon of the cathedral of Rouen, where he was named dean shortly before Charles's coronation. In 1363 he was made a canon at the Sainte-Chapelle, Paris. Upon completion of the Aristotle translations, with royal support he became bishop of Lisieux in his native Normandy. He held the post from 1377 until his

death five years later. Oresme also undertook official missions for the king, such as a journey in 1363 to Avignon to persuade Pope Urban VI to remain in that city under Charles V's protection. In an official document of 1377 Oresme is called counsellor of the king, although his appointment to that position may have come earlier. In his prologue to the Politiques , Oresme refers to himself as Charles's chaplain. Oresme played a conspicuous part in two important ceremonial occasions of the reign. During the visit in 1378 of the king's uncle, Emperor Charles IV, Oresme was a member of the delegation that escorted him to Vincennes. Later, the chronicles mention him among those taking part in the funeral ceremony of Queen Jeanne de Bourbon.[44] Oresme's long service to the crown included diplomatic and political acts, as well as less measurable intellectual contributions. Among them, his translations of Aristotle's works are highly significant, culminating his long personal and political ties with Charles. In these works, Oresme remained consistent with his earliest French writings, in which Aristotle's thinking served as a model for the prince's right conduct and rule.