Chapter 2—

The Cinematic Image as a Visualization of Sight

It is impossible to express the beauty in words. The art of painting is dead, for this is life itself, or something higher, if we could find a word for it.

—Constantijn Huygens, after seeing an image in a camera obscura (1622)

The visual systems represented by the eye and the camera receive "the light flux over time," and transform it into the visual world and the cinematic image. In the case of the eye, the transformation is organic, a biological necessity. In the case of the camera, it is mechanical and a cultural preference—the product of machines and technological processes created to satisfy socially determined expectations about what an image of the world should look like. Those expectations rest on assumptions about image making and visual perception that predate the invention of cinema by several centuries. This chapter will place those assumptions in their historical context, show why they have imposed unduly restrictive conventions on the making and viewing of cinematic images, and indicate some of the ways avant-garde filmmakers have rebelled against them to make cinematic images truly responsive to visual perception "in its deepest sense."

1—

For the recurring relationships between image making and visual perception, I have coined the expression "visualization of sight" and applied it in two different but clearly related senses. In its primary sense it refers to pictures ("still" or "moving," drawn or painted or photographed) that are intended to be equivalents of our actual experience of seeing. This is what Joel Snyder has called "picturing vision."[1] The softly glowing, barely distinguishable shapes in Monet's Water Lilies and the sharply focused,

immediately recognizable images of human forms and architectural spaces in Raphael's The School of Athens are both visualizations of sight because both represent what their makers believed to be pictures of what the eye actually sees.

In its secondary sense, visualization of sight refers to diagrams, models, and instruments of various sorts that reveal something about how sight occurs, whether or not they were originally intended for that purpose. In one way or another they give visible form to some aspect of the processes that produce sight. Let us begin with examples of this kind of visualization of sight, because in them we can see how models of how we see have influenced the efforts to picture what we see.

Our first example is familiar to anyone who has studied visual perception. It shows a schematized eyeball and a man scrutinizing the retina from the darkness behind the eye. It first appeared in René Descartes's treatise on optics and vision, La Dioptrique , published in 1637, and was intended to illustrate the formation of the retinal image. In Descartes's illustration the retinal image is produced by light rays entering the eye through the pupil and converging on the retina, where they form an inverted image of the sources outside the eye. Granting its schematic simplifications, the illustration is essentially accurate, which is why, presumably, it continues to appear in modern works on visual perception.

But what is the reason for including that man in the dark staring at the back of the eyeball? He has nothing to do with the formation of the retinal image, and we know Descartes did not subscribe to the naive theory that some sort of homunculus in the brain looks at the images on the retina and somehow lets the mind know what it sees there. Who is that man, then, and what is he doing?

One answer is fairly simple. He represents anyone who might perform an experiment that was first carried out by the German priest Christopher Scheiner in 1619, which Descartes describes in detail in La Dioptrique . The eye of a recently dead human or large animal, such as an ox, is carefully removed, and the membranes covering the back of the eye cut away without allowing the vitreous humor to spill out. Then a piece of thin paper or eggshell is placed where the membranes have been removed and the eye inserted into the hole of a special shutter so that the pupil faces the outdoors and the back of the eye is in a totally darkened room. "When this has been done," Descartes writes, "if you look at that white body . . . [the area where paper or eggshell has replaced the retina], you will see there, not perhaps without admiration and pleasure, a picture which will represent in natural perspective all the objects which will be outside of it."[2]

The formation of the retinal image,

as illustrated in René Descartes's La Dioptrique (1637).

Descartes goes on to note that by squeezing the eyeball slightly and thereby making it a bit longer, one can adjust the focus for objects brought nearer to the eye.

From a modern point of view, the eyeball is like a miniprojection system with adjustable focus and a built-in rear-projection screen on which images of the outside world appear for the "admiration and pleasure" of its one-person audience in the darkened room. From Descartes's point of view, however, the chief value of the experiment was to demonstrate empirically that "the objects we look at do imprint very perfect images on the back of our eyes."[3]

When Descartes wrote La Dioptrique , the retinal image was still a new concept in theories of visual perception, its existence having been documented only thirty-three years earlier in Kepler's Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena (1604). Although Kepler left it to others to figure out what happens beyond the retina, he established the retinal image as the nexus between the world of light and the dark processes of the brain from which our perception of the visual world emerges.

In ancient and medieval theories of vision, there was no intervening "picture." The eyes simply served as conduits for rays (of what nature and from what source were questions never satisfactorily answered) that permitted the brain to perceive the world. Ironically, perhaps, modern theories have come back to a somewhat similar view. As mentioned in chapter 1, the retinal image has been relegated to a relatively minor role in seeing, compared with the "grand scheme" of electrochemical impulses that begin with the play of light on the rods and cones and culminate in the brain cells that give us the sensation of sight. Nevertheless, Kepler's theory and the experiments of Scheiner and Descartes correctly emphasized the fact that a picture (or more precisely a nearly infinite sequence of pictures) stands between the world and our perception of it.

Kepler, in fact, used the term pictura to describe the image on the retina, and this was, as David C. Lindberg has pointed out, "the first genuine instance in the history of visual theory of a real optical image within the eye—a picture , having an existence independent of the observer, formed by the focusing of all available rays on a surface."[4] Lindberg's way of putting it certainly suggests analogies with the images in the modern photographic camera, but of course a much older camera, the camera obscura , fits the analogies equally well.

Originally the camera obscura was a dark room with a small hole in the roof or wall, through which an image from outside the room fell on a wall or screen opposite the hole. It seems to have been used primarily for

observing eclipses of the sun and for conducting experiments in optics. With more sophisticated versions of the camera obscura came a greater interest in the images themselves, and that interest led to the recognition that the camera obscura and the eye have certain image-making properties in common. Leonardo da Vinci appears to have been the first person to draw analogies between the camera obscura and the eye—which means that Leonardo's long list of accomplishments should include the invention of the camera-eye metaphor.[5]

Leonardo may have invented the metaphor, but Descartes more fully explored its implications. In La Dioptrique he argues that the images on the retina are like "images that appear in a chamber, when having it completely closed except for a single hole, and having put in front of this hole a glass in the form of a lens, we stretch behind, at a specific distance, a white cloth on which the light that comes from the objects outside forms these images." Descartes then compares the camera obscura to the eye: "The chamber represents the eye; this hole, the pupil; this lens, the crystalline humor, or rather, all those parts of the eye which cause some refraction; and this cloth, the interior membrane, which is composed of the extremities of the optic nerve [the retina]."[6] His experiment with the eyeball, Descartes explains, should make "more certain" that analogies between the camera obscura and the eye are accurate and appropriate.

Thus, by the early seventeenth century, the camera obscura had been recognized as an image-making instrument analogous to the eye. Both were dark chambers with a small aperture opposite a "screen" that received images produced by light passing through the aperture. (Although a lens was commonly present, it was not essential for the production of an image.) Both produced images that could be observed from the darkness behind the "screen," and because the images in both cases were two-dimensional projections of the three-dimensional world they had a distinctly pictorial quality.

Because of their pictorialness, the projected images had the potential of being transformed into literal pictures. Leonardo notes that when the images are received on a very thin white paper and viewed from behind, they appear in their "proper forms and colors," and "will seem actually painted on this paper."[7] It is not known who took the first step from merely observing that pictorial quality to actually reproducing it, but by the middle of the seventeenth century a number of ingenious devices had been developed for making pictures directly from the projected image on the translucent screen of the camera obscura .[8] Whether used for artistic

A small, portable camera obscura designed by Robert Hooke (1694).

From Philosophical Experiments and Observations (1726).

purposes or simply as visual records of places and things, these copies implicitly emphasized the pictorial qualities of the image in the camera obscura and by analogy the same pictorial qualities of the image on the retina.

As early as 1637 (the same year as the publication of Descartes's La Dioptrique ) Pierre Hérigone, a French mathematician, made the pictorialness of the retinal image explicit. "Vision," he wrote, "is the percep-

tion of the image of the object painted on the retina."[9] The notion of an image "painted on the retina" became a commonplace of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century theories of visual perception. At the same time, it was argued that since we do not normally perceive the world as a two-dimensional image flitting over a curved surface, there must be other, nonvisual factors such as touch, kinesthetic experience, memory, and other thought processes that contributed to our perception of a solid, stable, three-dimensional world.[10] In other words, the very qualities that draw attention to the pictorialness of the retinal image and suggest analogies between the picture "painted on the retina" and the picture in the camera obscura are also the qualities that distinguish the picture from the visible world it is a picture of.

A way out of that paradoxical situation was offered by the theory and practice of pictorial perspective, in which space as depicted is intended to represent space as perceived in the everyday visual world. Descartes had noted that the image on the simulated retina of the eyeball appeared "in natural perspective," and many people commenting on the images in the camera obscura had said the same thing. For example, Descartes's contemporary Daniel Barbaro alled the camera obscura a "natural means for showing perspective" and concluded a long description of the camera obscura by remarking, "Seeing, therefore, on the paper the outline of things, you can draw with a pencil all the perspective and shading and coloring according to nature."[11] By the time of Descartes and Barbaro, it was commonly assumed that since nature is three-dimensional, the rules of perspective offered a natural means of representing the three-dimensionality of the real world on the two-dimensional plane of a picture. This assumption seemed to be supported by scientific evidence as well as aesthetic practice. It also carried significant if less obvious ideological implications, which helps to explain why it exerted so much influence on visualizations of sight—and why, therefore, we must examine the specific mechanisms of that influence in painting, photography, and filmmaking.

2—

In actual practice pictorial perspective is a rather unscientific mixture of theory, experiment, and artistic convention, and I will go no further into the subject than seems absolutely necessary to demonstrate the role played by perspective in the presumed correspondences between visual perception and image making. For this purpose, the brief definition of

perspective offered by William Ivins in Art and Geometry is sufficiently precise and uncontroversial:

Technically, [perspective] is the central projection of a three-dimensional space upon a plane. Untechnically, it is the way of making a picture on a flat surface in such a manner that the various objects represented in it appear to have the same sizes, shapes, and positions, relatively to each other , that the actual objects as located in actual space would have if seen by the beholder from a single determined point of view.[12]

From the Italian Renaissance onwards, artists learned to envision that plane or flat surface as being like a plate of glass or even an actual window on which could be seen a proportionately scaled-down replica of the things in front of the glass. In Leonardo da Vinci's words, "Perspective is nothing else than the seeing of an object behind a sheet of glass, smooth and quite transparent, on the surface of which all the things may be marked that are behind this glass; these things approach the point of the eye in pyramids, and these pyramids are cut by the said glass."[13] What the artist does, in principle, is copy the image produced where the glass intersects the "pyramids," duplicating (to the degree his or her materials and skill permit) the exact shapes, colors, and shading seen there. Or as Alberti puts it, "A painting will be the intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance, with a fixed center and certain position of lights, represented artistically with lines and colors on a given surface."[14]

Leonardo and Alberti (like most Renaissance theorists of perspective) conflated the perceptual and the purely optical aspects of perspective.[15] They talked about images as if they were explaining concepts in geometry and mathematics. Vision became a question of "lines" forming "pyramids" that converged on a "point" in the eye, and painted pictures were simply larger versions of the picture produced by the same "pyramid" within the eye itself. Thus, the rules of perspective and vision seemed to complement each other and in both cases rested upon the principles of geometry and optics.

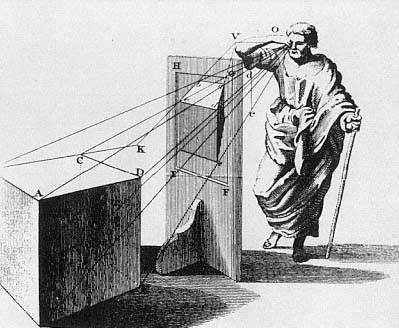

This meant that illustrations explaining the theory and practice of perspective were, at the same time, explanations of vision. They were, in effect, visualizations of sight that revealed—unintentionally—that a too literal application of the theories of perspective imposes peculiar limitations on understanding vision as well as on the possibilities of image making. The eye of the observer (the artist in this case) had to be an absolutely fixed point toward which all visual rays converge. The rays are represented with lines connecting the eye with the object of its regard, and

A demonstration of pictorial perspective: the plane E-F-G-H intersects

the visual pyramid whose base is the cube and apex is the viewer's eye.

From Brook Taylor, New Principles of Linear Perspective (1811).

where the lines pass through the artist's intersecuting plane, they define points corresponding to each line's point of origin. Alberti describes it this way: "We may imagine the [visual] rays as though they were very fine threads tightly bound together in a bunch by an iron band within the eye . . . almost like a pollard of all the rays, the node of which shoots its young branches straight and fine against any opposing surface."[16]

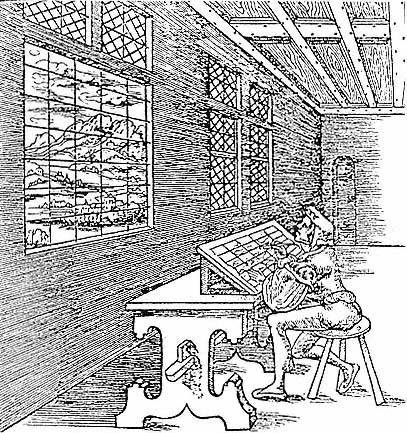

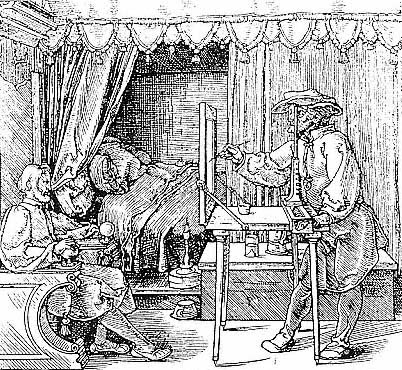

An illustration by Dürer shows an artist actually stretching strings from the object to the picture plane, but more normally artists covered the plane with a rectangular grid through which they looked at the objects from a fixed point of view—sometimes with the aid of an actual eyepiece mounted in front of the picture plane. The grid defined the hypothetical points where lines of the visual pyramid intersected the picture plane. With these points as guides, the artist could scale down the three-dimensional objects and situate them relative to each other on the two-dimensional surface of the picture.

Producing a picture by these means was like catching images in a rigid

Corresponding grids on the window and the artist's picture plane help

the artist to reproduce images seen on the plane created by the window.

From Johann II of Bavaria and Hieronymus Rodler, Ein schön nützlich

büchlein und unterweisung der Kunst des Messens (1531).

net strung across the space between the observer and the objects observed.[17] No matter how complex or ambiguous those objects might be—in form, spatial relationships, or emotional impact—they were caught in the same geometrical net and seen and depicted within the same rigid framework. Guided by this mechanical system of grids and immobilized points of view, the artist could (in the words of William Ivins) "substitute something that was rational and objective for something that was irrational and subjective."[18] What painting seemed to gain in realistic accuracy, it lost in what André Bazin called "the expression of spiritual reality wherein the symbol

The artist's eyepiece assures the fixed point of view necessary for

correct perspective. From Albrecht Dürer,

Underweysung der Messung , 2d edition (1538).

The fixed, peephole eyepiece and transparent screen offer the artist

a view much like that offered by a camera's viewfinder.

From Albrecht Dürer, Underweysung der Messung , 1st edition (1525).

transcended its model." Hence, for Bazin, "perspective was the original sin of Western painting."[19]

Not everybody has shared Bazin's pessimistic (and moralistic) views of perspective in painting, but most now agree that Renaissance perspective represents a special and limited interpretation of the visual world. It is, as Herbert Read has put it, "merely one way of describing space and has no absolute validity."[20] The Renaissance theory and practice of pictorial perspective encouraged an implicit equation between seeing and picture making based on the presumption that vision operates according to the same rules that artists follow in producing pictorial perspective. In Bazin's words, "The artist was now in a position to create the illusion of three-dimensional space within which things appeared to exist as our eyes in reality see them."[21] It is upon this basis that one can discuss a picture as a visualization of sight, in the primary sense proposed at the beginning of this chapter.[22]

3—

As a kind of guarantee of a picture's accuracy in visualizing sight, perspective was incorporated into the dominant theory and practice of the visual arts from the Renaissance until well into the nineteenth century, at which point photography arrived to carry on the traditional assumptions about visual and pictorial perspective. Technically, as Peter Galassi points out, "Photography is nothing more than a means for automatically producing pictures in perfect perspective."[23] Through mechanical, optical, and chemical processes the camera reproduced what earlier artists had tried to trace with pencils on the translucent screen of the camera obscura . And since the image in the camera obscura had been so readily equated with the retinal image, now the photographic image could be equated with the retinal image as well.

The photographic camera also seemed to duplicate the eye's structure: a dark chamber with an aperture and lens directing light rays onto a surface where an image of the world in front of the camera is formed. With photography the image could be preserved, removed from the dark chamber, and looked at with the same assumptions about verisimilitude that are commonly applied to paintings in perspective or to images on the back of the eyeball.

Here the circuitous historical argument we have been pursuing doubles back on itself. Descartes and Scheiner made the retinal image visible to the observer in the dark room behind the eyeball. Now anyone can reenact the

role of that observer by looking at a photograph. When the photographic image becomes cinematographic, the observer returns to the darkened room with a screen, like the retina, on which ephemeral images are in constant motion. Observing the images cast on the screen by the projector, the viewer easily feels the "admiration and pleasure" Descartes felt when "that white body" revealed "a picture which will represent in natural perspective all the objects which will be outside of it."

Of course, the image on the cinema screen is just as flat and pictorial as the image on the retina—and also the images in the camera obscura , in paintings, and in photographs—but its equivalence to the three-dimensional world has been guaranteed by the principles of pictorial perspective built into the lenses of cameras and projectors. These machines are not only carefully engineered to obey the same rules of geometrical optics that are assumed to produce perspective in seeing and in picture making, they also have incorporated the girds, eyepieces, and other mechanical contrivances in the perspectivist's toolbox. From these rigid restrictions on seeing comes the typical cinematic image.

Not only is it "in natural perspective," but the usual cinematic image shows a world that is focused, stable, and unambiguously lit. These additional norms are not required by the rules of perspective, but they have proved to be peculiarly suited to an image-making system based on mathematically precise calculations and geometrically exact projections. Yet, like perspective, they are relevant to a very small part of what we actually see: not much more than two degrees of the approximately 200-degree angle that our eyes encompass as we look at the world around us. They come from that part of the retinal image covering the fovea centralis, the extremely small central portion of the retina where the color-sensitive and high-resolution cones are most tightly packed together. The farther visual awareness ranges from that tight little two-degree island in the center of the visual world, the less it has in common with the normal cinematic image.

In effect, the norms derived from perspectivist painting have denied the cinematic image much of what the eye actually sees. Spatially, they exclude virtually everything but the two-degree wedge of space directly in front of the eyes, and psychologically, they avoid the distortions of emotion and idiosyncratic points of view. They place a premium on a measured and cooly analytical approach to image making—what William Ivins calls "the rationalization of sight." Ivins argues persuasively that "the forms produced by our modern geometrical perspective are conventions which . . . are only a loose general rationalization of the actual sense returns of physiological binocular vision."[24] R. L. Gregory has pushed the

argument further by insisting, "In an important sense perspective representations of three dimensions are wrong, for they do not depict the world as it is seen but rather the (idealized) images on the retina. But," he reminds us, "we do not see our retinal images."[25] We see what the eye's "grand scheme" derives from the patterns of light falling on the retina.

Therefore, the artist's and the camera's representations of the retinal image cannot be the equivalent of what we actually see. "Indeed," as Gregory wryly remarks, "it is fortunate that perspective was invented before the camera, or we might have had great difficulty in accepting photographs as other than weird distortions."[26] This may be why some anthropologists have reported that photographs are initially unintelligible to people who have had no experience with pictorial representations of perspective.

In Western culture, geometrical perspective has been familiar for so long that its limits on and deviations from actual vision are hardly noticed at all. It is, in other words, a set of pictorial conventions that, as Ivins points out, is of "such great utility and so exceedingly familiar that for practical purposes it has the standing of a 'reality.'" Because photography automatically incorporates geometrical perspective, it has confirmed perspective in the public mind, made it "true" and, in Ivins's phrase, "clamped it on our vision."[27] This has resulted in a very odd situation. An image deprived of the full possibilities of visual perception has become generally accepted as the only accurate visualization of sight. The measure of its accuracy is not what we actually see but what the perspectivist tradition has produced as pictures of what we see.

The situation has become so thoroughly institutionalized that the dominant cinema, its audiences, and most critics who write about it happily accept perspectivist norms for cinema's visualization of sight—with consequences that André Bazin eloquently defends. Although "perspective was the original sin of Western painting," in Bazin's view, "it was redeemed by Niepce and Lumière"—by photography and cinema, in other words, which Bazin regards as "discoveries that satisfy, once and for all and in its very essence, our obsession with realism." The work of painters, no matter how skillfully it might incorporate the rules of perspective, "was always in fee to an inescapable subjectivity," Bazin argued, but photography "completely satisf[ies] our appetite for illusion by a mechanical reproduction in the making of which man plays no part." For Bazin, "The cinema is objectivity in time."[28]

Bazin reiterates these points when he uses his "ontology of the photographic image" as a basis for his essay "The Myth of Total Cinema."

There he presents cinema as the inevitable goal toward which "all the techniques of the mechanical reproduction of reality in the nineteenth century" were tending: "namely an integral realism, a recreation of the world in its own image, an image unburdened by the freedom of interpretation of the artist or the irreversibility of time."[29] This "guiding myth," as Bazin calls it, is the outcome of mutually reinforcing attitudes toward seeing and reproducing what is seen, which have made the cinematic image a powerful, yet peculiarly limited visualization of sight. For Bazin, as for the dominant film industry (and many critics and theorists who otherwise have little sympathy with Bazin's defense of realism), the strength of the cinematic image derives from its (generally unrecognized) limitations—that is, from its exclusion of any kind of seeing that is not amenable to mechanical, optical, and photochemical reproductions of Renaissance pictorial perspective.

Therein lies the source of the "trouble" in the lens: a mechanization and standardization of seeing that sacrifice much of what emotion, imagination, and the total visual experience offer to visual artists. Filmmakers dedicated to "vision and visualization" would therefore find it easy to agree with the artist and art historian José Argüelles when he calls perspective "a graph applied to the eye for the purpose of mechanizing vision and thus mind" and with Stan Brakhage when he describes the "vista" in Père Lachaise cemetery as "a play of planes wherein one makes marionette of one's eye's sight for the vanishing of lines into perspective, to say 'O!', to have x-changed one's owned sight for the first ring of a chain of other vision."[30] Elsewhere Brakhage has told how his efforts to develop freer and more relaxed ways of seeing made him conscious of "something that was constricting my sight." That "something," he decided, was his "training in this society in Renaissance perspective—in that form of seeing we could call 'westward-hoing man,' and which is to try to clutch a landscape or the heavens or whatever. That is a form of sight which is aggressive and which seeks to make any landscape a piece of real-estate."[31]

Brakhage's contentions have a historical basis in the congruence of advances in mapmaking, the early voyages of exploration, and the adoption of geometrical perspective by Renaissance artists. Samuel Edgerton discusses these developments in detail,[32] and Argüelles comments on them in terms very similar to Brakhage's:

In actuality both the topographical and the ideal landscapes are based on the mechanical contrivance of the perspective grid. Through this means nature is denatured. The corresponding development of Mercator's projection system (1541), in which terrestrial geography is plotted into squares, aided in the

transformation of nature from a wilderness into an intellectual field-pattern, and finally into real estate.[33]

Here, as in Brakhage's comments, perspective becomes an ideological issue, or as Claudio Guillén calls it in his study of perspective as a metaphor, a "cultural concept."[34]

As a "cultural concept," perspective implies for Brakhage the loss of individual perception ("x-changed one's owned sight for the first ring of a chain of other vision") as well as an aggressive and proprietary attitude toward nature and the world in general ("to make any landscape a piece of real-estate"). Others have interpreted the relationship of perspective to individuality differently, arguing that perspective has enhanced bourgeois concepts of individualism by placing the individual's eye at the apex of the pyramid of rays intercepting the picture plane. "This makes the single eye the centre of the visible world," John Berger writes: "Everything converges on to the eye as to the vanishing point of infinity. The visible world is arranged for the spectator as the universe was once thought to be arranged for God."[35] Thus individual consciousness, the eye-ego, believes itself to be the maker of what it sees. Everything seems to fall into place according to the individual's point of view. Although this suits the bourgeois ideology of individualism, it does not mean that, in fact, individuals are experiencing their own perceptions of the world. They are simply adjusting their view to what an artist has produced with the aid of geometric perspective.

By incorporating perspective into its image-making apparatus, cinema has maintained the "cultural concepts" that give each member of the audience the sense of seeing the image from a privileged and unique point of view, while remaining distanced from it. This is what Stephen Heath calls "the positioning of the spectator-subject in an identification with the camera as the point of a sure and centrally embracing view."[36] The problem is that the view provided by the camera is not privileged and unique at all. It conforms to the norms of pictorial perspective and imposes them on the cinematic image. It denies the "spectator-subject" the possibility of experiencing a truly individual perception—just as it stands between the artist and his or her desire to create images true to an individual perception of the visual world.

4—

In their efforts to achieve their own authentic visualizations of sight, avant-garde filmmakers have severed the bonds between the cinematic

image and the perspectivist tradition. They have broken the rules of filmmaking and subverted the cinematic apparatus. A paradigmatic statement of the avant-garde's approach to filmmaking appears in Brakhage's Metaphors on Vision:

By deliberately spitting on the lens or wrecking its focal attention, one can achieve the early states of impressionism. One can make this prima donna heavy in performance of image movement by speeding up the motor, or one can break up movement, in a way that approaches a more direct inspiration of contemporary human eye perceptibility of movement, by slowing the motion while recording the image. One may hand hold the camera and inherit worlds of space. One may over- or under-expose the film. One may use the filters of the world, fog, downpours, unbalanced lights, neons with neurotic color temperatures, glass which was never designed for camera, or even glass which was but which can be used against specifications, or one may photograph an hour after sunrise or an hour before sunset, those marvelous taboo hours when the film labs will guarantee nothing, or one may go into the night with a specified daylight film or vice versa. One may become the supreme trickster, with hatfuls of all the rabbits listed above breeding madly.[37]

Such a "supreme trickster" is Brakhage himself, whose hats have produced "all of the rabbits listed above" and more. What is important is not the novel techniques per se but the recognition that these techniques are necessary to free the cinematic image from "Western compositional perspective" (Brakhage's expression) and the pictorial conventions it supports.

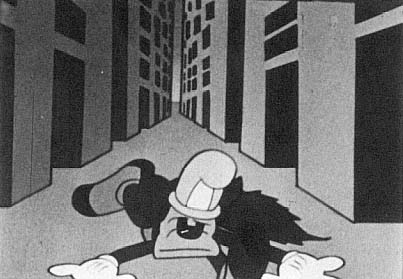

In a piece of found footage included in Brakhage's Murder Psalm (1980), a cartoon animal dressed as a policeman runs directly toward the audience, while the buildings lining the street recede behind him in exaggerated lines of perspective. Suddenly a car comes hurtling out of the vanishing point, runs over him, and disappears. With cartoon logic, the animal jumps up and continues running, now angrily waving his nightstick at the departed car. In subsequent shots he is run over again, and the last time we see him, he is lying flat on his face in the street. These are only a few brief images cut into a complex and subtly nuanced film, yet it is hard not to see in them a parable of the futility of trying to flee "Western compositional perspective" by running away from its vanishing point. Not only will it attack from behind, but it leaves its victim no option but to run straight ahead, toward the open end of the visual pyramid, which is, in fact, the flat, impenetrable screen. The screen, moreover, is only the base of another pyramid whose apex is (perceptually) in the viewer's eye and (optically) in the projector's gate.

Brakhage has long recognized the irony of campaigning against "Western compositional perspective" while continuing to work with its most

Exaggerated perspective in a found cartoon

(Murder Psalm , Stan Brakhage).

efficient tools. He has noted that the light between the project and the screen offers a striking equivalent to the visual pyramid intersecting the painter's picture plane. By its very nature, Brakhage has said, film emphasizes perspective and "creates this perfect tunnel" from the projector to the screen. But he also insists that this is an "artificial" situation and one that filmmakers can confront and expose by creatively using the medium against its own predilections.[38]

A good example is his own Song XII (c. 1966), which he has explained came about because of his extremely negative reaction to Chicago's O'Hare airport. Being in the airport had given him a terrible headache, and he decided that the cause had been O'Hare's long, glass-enclosed corridors, which made him feel trapped in a maze of vanishing points. Subconsciously his eyes had been fighting the strong pull of the corridors' lines of perspective and their dramatically emphasized vanishing points—effects made even more disturbing by the glass walls that superimposed and reflected them ad infinitum . As soon as he flew out of O'Hare his headache disappeared. Later he returned to make Song XII .[39]

His capsule description of the short 8mm film ("Verticals and shadows—reflections caught in glass traps") indicates some of the formal elements and general theme of Song XII , but it only hints at the film's confrontation with

"Reflections caught in glass traps"

(Song XII , Stan Brakhage).

the power of perspective.[40] The film is in gray and white, with almost continuous superimpositions that not only layer one image over another but soften shapes and wash out fine details as the shots overlap, dissolve, and fade in and out. Anonymous figures (or their reflections and shadows) appear briefly and usually in slow motion amid geometrically regular lines and planes (a visual pun on "plane" is even suggested by one shot in the film that actually shows an airplane beyond or reflected in a glass wall). The superimpositions produced by the reflections are compounded by the su-

perimposition of shots, and the viewer's eye becomes trapped by conflicting cues to perspective. It is not people in an airport but seeing itself that is "caught in glass traps."

The lens of Brakhage's camera is also a "glass trap," as Brakhage would be the first to admit. But that trap is sprung by the superimpositions, the overexposure, the cuts, fades, and dissolves with which Brakhage undercuts the single and immobile, precise, and authoritarian point of view built into the camera's lens. Instead of trying to run away from perspective within its own rigid lines (like the hapless cartoon policeman), Brakhage makes the lines and planes of perspective serve his own artistic (and in this case therapeutic) need to escape the tyranny of the vanishing point.

If Brakhage defeats perspective by changing its rules, Ernie Gehr beats it at its own game in Serene Velocity (1970). From a fixed point of view, like that of the artist's eye in illustrations of how to draw in perspective, Gehr's camera filmed a long bare corridor lit by a row of fluorescent lights in the ceiling. The lines formed by the floor, walls, ceiling, and lights converge toward a vanishing point behind two doors at the end of the corridor. The rectilinear space and dramatically receding lines make the basic image of Serene Velocity a model of geometrical perspective. It is a perfect cinematic equivalent of Alberti's formula: "A painting will be the intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance, with a fixed center and certain position of lights, represented artistically with lines and colors on a given surface."[41]

In Serene Velocity , however, the "intersection of a visual pyramid at a given distance" changes every one-sixth of a second. The film alternates four-frame shots of the corridor taken at different focal lengths (with a zoom lens). As the film proceeds, the disparity between focal lengths gradually increases. 50mm shots are juxtaposed with 55mm shots, then 45mm shots with 60mm shots, 40mm with 65mm, 35mm with 70mm, and so on. Because of the principles of geometrical perspective built into the lens, each change in focal length is like a change in the place at which the imaginary picture plane intersects the visual pyramid. The (invisible) vanishing point at the center of the image remains the same because the camera position remains the same, but the angle of converging lines changes: narrowing as the focal length decreases, widening as the focal length increases. It is as if the vanishing point were leaping toward and away from the picture plane six times every second. The visual effect is to make the space seem deeper or shallower and the doors farther from or closer to the viewer, as the shots alternate between shorter and longer focal lengths. The increasing disparity of focal lengths produces a cinematic image that progresses from mild pulsations to what P. Adams

An empty corridor emphasizes the lines and planes of geometrical perspective

(Serene Velocity , Ernie Gehr).

Sitney describes as "an accordion-like slamming and stretching of the visual field."[42] The illusion of a stable three-dimensional space is thoroughly shattered by Gehr's manipulation of the very devices and conventions of geometrical perspective that were designed to produce it.

Michael Snow's Wavelength (1967) also exploits changes in perspectival relationships produced by changes in focal length. In Snow's film, however, the change of focal lengths (again with a zoom lens) only goes in one direction—from short to long, from wide angle to telephoto—so that an initial image of fairly deep space is slowly drained of its illusionistic depth. Like Gehr, Snow filmed a single enclosed space, a nearly empty room, from one point of view. But unlike Gehr, whose framing emphasizes the receding lines of perspective, Snow deemphasizes perspective by shooting from a high angle that centers attention on the far wall of the room, its windows, the tops of trucks passing outside, and the fronts of the buildings across the street. Although as Snow points out, "It's all planes, no perspectival space," the image retains a fairly strong impression of perspective (it could hardly do otherwise, given the optical properties of the lens) until the zoom-in has eliminated the cues to perspective and flattened the room's space against the wall and windows.[43] Then the image

can be seen for what it really is: light making "lines and colors on a given surface," in Alberti's phrase. In chapter 7 I will examine in much more detail the implications of Wavelength's zoom; for now, I simply add it to the list of ways avant-garde filmmakers have forced the lens to reveal what it is supposed to conceal: the problematic nature of perspective within the cinematic image.

Another way—brilliantly exploited by Sidney Peterson, most notably in Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur (1949) and The Lead Shoes (1949)—is the creation of anamorphic images. Anamorphosis was a direct spin-off of the development of Renaissance perspective and perhaps the first example of artists using the rules of perspective to frustrate ordinary seeing. (The best known example is an anamorphic death's head in the foreground of Holbein's The Ambassadors , but many other examples can be found in paintings since the fifteenth century.) As Claudio Guillén writes, "This vexing sort of visual trickery was but an extension of the illusionistic power implicit in perspective, and of the notion that the characteristics of vision could control the visible contents of the painting."[44]

In conventional perspective, the picture plane intersects the visual pyramid at an angle that is at, or fairly close to, a ninety-degree angle—like a window glass through which one views the scene outside. The anamorphic picture plane is either curved or skewed at an extremely oblique angle to the visual pyramid, which results in images that are weirdly stretched or squashed when looked at straight-on (as we look at most pictures) but will appear normal and in perspective if viewed from an oblique angle or reflected in a curved surface that matches the original point of view. The trick will work only if the artist rigorously maintains a fixed point of view and accurately reproduces the point-to-point correspondence between the three-dimensional objects and their two-dimensional images on the picture plane. An anamorphic lens applies the same mathematical rigor to bending light rays so that they strike the film at an "abnormal" angle and produce a cinematic image that looks distorted if it is projected through a normal lens but appears normal when projected through another anamorphic lens that corrects the original distortions.

Peterson's anamorphic images are intended to remain uncorrected, with the result that familiar shapes appear grotesquely elongated or unnaturally short and squat. They seem to occupy a space that is too shallow and strangely congealed (an impression encouraged by the extreme slow motion Peterson commonly uses in his films). These images may evoke "the realm of dream, memory or a visionary state," as Sitney suggests, but first and more overtly they subvert the objective visualization of sight

that the rules of perspective are presumed to guarantee.[45] Peterson himself has said that anamorphosis is "the most subjective of all the branches of linear perspective" and hence a way of emphasizing "the subjectivity of the viewing process."[46]

To wring a subjective visualization of sight out of the objective lens is what Brakhage had in mind when he recommended using the lens "against specifications." Another example of that tactic is Ed Emshwiller's practice of filming with a wide-angle lens brought very close to his subjects. As Emshwiller's camera moves over them, parts of the body balloon out then shrink away; all sense of proportion disappears; the solid, three-dimensional world becomes an undulating field of polymorphic shapes. Relativity (1966) is not only the title of Emshwiller's best-known film, it is also the principle underlying these visualizations of sight: there is no single, correct representation of objects in space; all is relative to the point of view and the way the lens bends the light rays.[47] Like Peterson's "subjectivity of the viewing process," Emshwiller's relativity of the cinematic image is as prized by avant-garde filmmakers as it is abhorred and hidden by the dominant film industry—except for occasional special effects, dream sequences, and the like. The avant-garde does not need such narrative excuses to justify its rejection of the lens's objectivity.

Avant-garde filmmakers have found many other ways to break the lens's subservience to the goals of geometric perspective. The murky, stippled image in parts of Man Ray's Etoile de mer (1928) and the multifaceted psychedelic images in passages of Kenneth Anger's Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) and a number of other films of the 1960s were produced by special lenses. But many filmmakers have found that simply by throwing an ordinary lens out of focus—"wrecking its focal attention," as Brakhage calls it—the spatial clarity of perspective will dissolve into glowing colors and mysterious, overlapping shapes. Superimposition (another tactic favored by many avant-garde filmmakers) automatically destroys the single, fixed point of view essential to perspectivist representations of space. Collage techniques and masking can produce disproportionate sizes and conflicting vanishing points within the same image. Rapid camera movement can flatten space and shatter the edges separating objects from each other and the space around them; if it is rigorously pursued, it can evoke totally new perceptions of space—as has been demonstrated in films as different as Brakhage's Anticipation of the Night (1958) and Snow's « (Back and Forth ) (1969) and La Région Centrale (1971).

Rapid intercutting of simple images and movements also flattens the perceived space, as Léger seems to have been the first to discover while

making Ballet mécanique (1924).[48] If the intercutting is rapid enough and extended over a long enough period of time, as in Tony Conrad's The Flicker (1966) and passages of Paul Sharits's "flicker films," the flatness of the screen can give way to illusory and ambiguous perceptions of depth that have nothing to do with the depth cues of perspective. In a very different way, Duchamp's Anemic cinéma (1927) turns depth perception into an optical illusion by presenting rotating spirals that seem to protrude from and recede into the screen itself.

Jordan Belson exploits a similar illusion in Allures (1961), though in most of his films the methods are much subtler and involve coordinates and cues to perspective that are constantly changing the implied point of view of the camera. The result is a "disembodied perspective," which Sitney associates with a passage in Olaf Stapledon's science-fiction novel Star Maker: "But I had neither eyes or eyelids. I was a disembodied, wandering viewpoint."[49] Similar effects can arise from contemplating the permutations of vastly intricate dot patterns in James Whitney's Yantra (1957) and Lapis (1966).

There are also avant-garde films with images that have never been subjected to the perspectival biases of the lens because they were made without cameras—such as the "Rayograms" opening Emak Bakia (1926), the scratched and painted films of Len Lye, Norman McLaren, Harry Smith, and Stan Brakhage, to mention a few of the best-known practitioners of these handmade effects. There is also that tour de force of cameraless films, Brakhage's Mothlight (1963), with its bits of leaves, grass, flowers, and moth wings taped to the surface of a clear film base.

Some of the films mentioned above will be examined more fully in later chapters. Comparable examples could be listed almost endlessly if more evidence were needed to demonstrate the avant-garde's concerted effort to challenge the perspectivist tradition and break its hold on the manufacture and conventional uses of the cinematic apparatus. Virtually all avant-garde filmmakers have contributed to and profited from this effort to make the cinematic image a fuller and much more revealing visualization of sight—no one more so than Stan Brakhage, whose campaign on behalf of what he calls the "untutored eye" has produced the most pointed attacks on and most creative departures from the conventional cinematic image. To appreciate the nature of that campaign, we must make an excursion into the history of theories of visual perception—where we will discover significant corollaries to the propositions concerning vision, perspective, and the cinematic image that we have examined in this chapter.