ONE—

TEXT/CONTEXT

In the course of the strange odyssey, which Rabelais describes in his Fourth Book, Pantagruel and his friends sail along one morning "in high spirits" — until their guide Xenomanes points out Tapinos Island, where Quaresmeprenant rules.[1] Humanists among Rabelais's early readers would not have been surprised at the dampening effect the island's name seems to have on the company: Tapeinos, a Greek adjective describing something low, might refer to a low lying island or, more figuratively — and readers of Rabelais are amply conditioned to take things figuratively — to a miserable island, a base and paltry place. Humanist or not, Rabelais's readers might also have known the expression en tapinois, documented from 1480 onward, which meant to do something with dissimulation or like a sneak.[2]

Is it there that "Quaresmeprenant" reigns? French readers, humanist and nonhumanist, must have been very surprised at this, for to them Quaresmeprenant was a word referring to Carnival.[3] From at least the

[1] François Rabelais, Le Quart Livre, ch. 29 (published 1552), in Oeuvres, ed. Jacques Boulenger (Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1955), 641. All quotations from Rabelais are from this edition, unless otherwise noted; page numbers, when relevant, will be given after book and chapter in this form: QL , 29, 641. Other abbreviations used with reference to this edition are: G, Gargantua; P, Pantagruel; TL, Tiers Livre; CL, Cinq Livre; PP, Pantagrueline Prognostication ; Pr, prologues by Rabelais; DL, dedicatory letter in the Fourth Book; BD, Briefve Déclaration d'aucunes dictions plus obscures contenues on Quatriesme Livre ; L, other letters by Rabelais; Pl. Bib., Bibliography compiled by Boulenger and revised by L. Scheler. Quotations from other works included in Boulenger's edition will simply give page numbers but will be identified by title in the text. English translations of Rabelais and other authors are mine throughout.

[2] Xenomanes uses the phrase to describe Quaresmeprenant later: "De toutes corneilles prinses en tapinois ordinairement poschoit les oeilz" (QL, 32, 649). J. M. Cohen translates Tapinos Island as Sneaks' Island in his English translation of Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel (Harmondsworth, Eng., 1955), 512.

[3] Carnival will be capitalized when it refers to the festival preceding Ash Wednesday (see n. 1, Foreword). Mardi Gras also will be capitalized when referring to this festival generally; when it refers only to the day before Ash Wednesday, it will be lowercased.

thirteenth century and perhaps in oral discourse for a long time previously, "Quaresmeprenant" rivaled "Caresmeentrant" and "Charnage" as a word designating either the personification of or the collective term for the revelry-filled days preceding Lent (Carême or Quaresme ). "Mardi Gras," Fat Tuesday, the last day of Carnival before Ash Wednesday, was also occasionally used to mean Carnival time or its personification in general. Many other sixteenth-century writers — Clément Marot, Marguerite de Navarre, Henri Estienne, Etienne Pasquier, Agrippa d'Aubigné, and Michel de Montaigne — used Quaresmeprenant in this manner.[4]

What is Carnival doing as king of a miserable island, reigning perhaps as a sneak or over sneaks? From Xenomanes's subsequent description, this Quaresmeprenant is anything but a merrymaker. In fact, he behaves more like Lent than Carnival. He is, says Xenomanes, "a man of worth, a good Catholic, thoroughly devout . . . . He is a great fellow for breaking barrels . . . half a giant, fuzzy-chinned and wearing a double tonsure." Is this a member of the clergy, then, or is the phrase metaphorical, referring to someone doubly stupid, with even less wits than the proverbial doctor or lawyer "with a single tonsure?"[5] What kind of barrels does he break? Are they full of herrings — as has usually been assumed by commentators — or of wine, or perhaps of that ambivalent food, snails? What did he do with the broken barrels, empty them into his gullet or throw them away with abhorrence[6]

[4] See Edmond Huguet, Dictionnaire de la langue française du seizième siècle, Volume 2 (Paris, 1932), 98–99, article "Caresmentrant, Caresme-prenant" for quotations from the authors mentioned in the text. Estienne is particularly explicit, citing a "parish priest . . . speaking of mardi gras, in other words Quaresmeprenant or Quaresmentrant, [who] recommended to his parishioners Saints Big Paunch, Gross Eater, and Full-to-Bursting [Pansard, Mangeard, Crevard]."

[5] QL , 29, 642. The "proverbial phrase, docteur, medecin, avocat etc. à simple tonsure " is quoted by Johan Gottlob Regis, ed. and trans., Gargantua und Pantagruel , Volume 2 (Leipzig, 1832–1841; reprint, Munich, 1911), 234. Regis also points to Rabelais's reference to "fol à simple tonsure" in TL , 38, 487, a phrase occurring in the comically antiphonal blason of the fool Triboulet by Pantagruel and Panurge. Panurge's "fol à simple tonsure" is his response to Pantagruel's "fol prétorial." Regis does not cite the source or derivation of his proverbial phrase. Does it come from the custom of furnishing university students with a single tonsure as a symbol of first entry into the clergy when they begin studies, but tonsuring them again when they enter higher faculties? In this case double tonsure could refer in an inversionary, satiric sense to someone of little wit.

[6] Caquerotier seems to be composed of French caque with -rotier, from Latin ruptor, someone who breaks or strikes open. On caque , see Jean Nicot and Aimar de Raconnet, Thresor de la langue françoyse, tant ancienne que moderne (Paris, 1621), 101: "Caque, m. penac. Est une espece de futaille . . . et est à eau, à poisson salé" Randle Cotgrave's Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (London, 1611), folio O, ii recto, translates: "Caque . . . a barrell, or vessell, wherein saults-meats, pitch, rosen, etc., are usually carried, or kept"; "Caqueroles: the shels of Snayles, Periwincles, and such like; "Caquerotier: m. A catcher, cater, or owner, of shellfish." Hence "Un grand cacquerotier" is annotated in Rabelais, Oeuvres complètes, ed. Pierre Jourda, Volume 2 (Paris, 1962), 125, as "mangeur d'escargots (?) ou de cacques de harengs (?)." Snails are ambivalent food: In nineteenth-and twentieth-century Languedoc they were used, by varying the sauce in which they were prepared, to mark Carnival and Lent successively: "Ainsi l'escargot devint-il, entre les mains des cuisinères, une viande ou un poisson incarnant successivement les deux temps du calendrier alimentaire." Claudine Fabre-Vassas, "Le soleil des limaçons," Etudes rurales, nos. 87–88 (July–December 1983): 78. If the phrase refers to snails, the meaning of Quaresmeprenant's name and behavior become still more difficult to fathom.

Quaresmeprenant is a linguistic paradox, whose name is at once confirmed and denied by his actions. The man is full of contradictions. He dresses in a "joyous" manner both in cut and color, Xenomanes continues ironically: his clothes are "gray and cold, with nothing before and nothing behind, and sleeves to match." He spends his time manufacturing larding sticks and meat skewers — toothsome Carnival preparations — and yet "he weeps three parts of the day" and never attends a wedding. "He's the standard-bearer of the Fisheaters," declares Xenomanes, "dictator of Mustardland, a whipper of small children, a burner of ashes." Ashes were thrown about in Carnival-time, but a cross of ashes was also drawn on penitents' foreheads at the beginning of Lent. Mustard was consumed in great quantities with fish in Lent — and also with sausage in Carnival. Quaresmeprenant whips children and sits about weeping. Who is this fellow, whose appearances and activities seem so absurdly, violently irreconcilable?

Xenomanes soon mentions Quaresmeprenant's enemies, the "Zany Sausages who live on Ferocious Island" (les Andouilles farfelues de l'Isle Farouche ). Although they might seem to be simple animations of Carnival fare — pork sausage was a favorite dish during Mardi Gras — these folk turn out to be as puzzling as the master of Tapinos Island. They behave, metaphorically speaking, less like sausages than like eels: Lenten food. The andouilles conduct themselves like anguilles , fishy and wriggling. As if to substantiate the point, a later chapter explains that they are the venerable ancestors of the mermaid Melusine and of the sly snake who tempted Eve.[7]

[7] QL , 38, 665.

The episode that describes the Pantagruelians' encounter with Quaresmeprenant and the Sausages is the longest in Rabelais's Fourth Book , the last work published before his death in 1553. I have indicated the larger interpretive reason for attempting to understand the puzzles posed by this unusually prominent episode: Bakhtin, who sees a "carnivalesque spirit, permeating Rabelais's text, deals with these chapters only in passing, although they would seem crucial to his hypothesis.[8]

Bakhtin is not alone in this. The most authoritative editors of Rabelais's text and most modern critics have argued away its paradoxes. Never mind the name, Quaresmeprenant is Lent, and the Sausages are just Carnival food, appropriately assaulted by Pantagruel's cooks. The Quaresmeprenant chapters are treated as an example of Rabelais's humanist, evangelical attacks on church practices, in this case fasting. The Sausage-people chapters, which involve a battle between them and Pantagruel's cooks, are seen as one of Rabelais's mock epic war stories. Such interpretations deal with what are considered the salient features of the text, not its troubling details. They construct an even surface, not a series of polysemic knots.[9] Separating the Quares-

[8] In addition to chs. 29 through 42 of QL , there are two further episodes in Rabelais's novels, both in G , where Rabelais may be said to set the scene in Carnival time: the moment of Gargantua's birth (G , 4–6) and the visit of Master Janotus de Bragmardo, to Gargantua (G , 18–20). But Rabelais says nothing about the nature of Carnival here, nor does he describe its relation to Lent. He merely alludes to several Carnival customs. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World , 222–24, makes much of the birth scene and refers also at some length to Janotus's visit, but he mentions the Quaresmeprenant-Sausage episode in only a few scattered sentences: 177, 323, 34–6, 400, and 4–15.

[9] For example, Pierre Jourda in his prestigious edition (the "Classiques Garnier") reproduces a seventeenth-century print, entitled "Le combat de Mardygras" (Rabelais, Oeuvres, ed. Jourda, Volume 2, unnumbered page following 126), mistitled as "Combat de Mardigras et de Quaresmeprenant": the verses written on the print identify the combatants as "Mardy gras" and "Caresme." Like Jourda, Boulenger (QL , 29, 642), Cohen, trans., Gargantua, 512, and Robert Marichal (ed. Rabelais, Le Quart Livre, édition critique [Geneva, 1947]) treat Quaresmeprenant as Lent. Marichal, whose edition offers the most complete and authoritative text of the full Fourth Book available at present, does not mention the conflict between allegorical figures of Carnival and Lent. Michael Screech does treat the Quaresmeprenant and Andouilles chapters as forming one episode, and he does point to the custom of Carnival-Lent battle as forming the background for the tale. But he calls Quaresmeprenant "the spirit of Lent" "the incarnation of the onset of Lent;" or "Lent" tout court in his Rabelais, 371, 367, 373. He does not see any meditation on the nature of Carnival and Lent in this episode: Rabelais is for one and against the other, and so he concludes, 377: "The Andouilles arc not right but merry [Screech lays considerable emphasis on the contemporary religious meaning of the Sausages as Protestants]; Quaresmeprenant is wrong and repulsive." Other contemporary criticism of the episode is discussed in my chs. 3–5 and especially ch. 7 below.

Of course I am not arguing that Rabelais's chs. 29–42 can or should only be understood from the point of view of their allusions to Carnival-Lent customs. Important aspects of the text demand that quite different groupings of the chapters or subdivisions of chapters be considered, in accordance with interpretive goals different from the problematics pursued here.

meprenant chapters generally from the Sausage-people chapters and treating Carnival-Lent conflict as little more than a vague formal framework for the episode has important consequences, for these moves lead one to wish away a third puzzle: Why do Pantagruel and his army, defenders of carnivalesque boozing and banqueting and hence the enemies of the Sausages' enemy "Lent" (that is, Quaresmeprenant), attack such presumably congenial folk as the Sausage-people while never confronting Quaresmeprenant, whom Pantagruel denounces as a monstrous "Anti-Nature"? Is there perhaps more to it than the obvious references to Sausages as Carnival food and to the Pantagruelians as gourmands?

The fact is that Quaresmeprenant meant Carnival in the sixteenth century, and Rabelais was no stranger to his times. He was strange enough, however, to find playing with commonplaces fascinating and perceptive enough to see that Quaresmeprenant, which etymologically seemed to mean "taking Lent," was a curious name for Carnival. Word games gave wings to Rabelais's fantasy. And what if the phonetic similarity between andouille and anguille were brought to bear upon the parallel obscenities clustering around their slippery, long, round forms? Once fantasy began its play, there was no stopping until meat merged with fish, man with woman, and humans with animals, or seemed to.

This episode of the Fourth Book largely dissolves the traditional moral difference between Carnival and Lent. Despite the conclusions about Rabelais's ambivalent or ambiguous position drawn by the few critics who have observed the variable overtones given to the protagonists in these chapters, Rabelais does not equivocate between the two calendrical moments. And although he hops and skips among etymologies and puns, he does not confuse the symbols traditionally associated with one occasion with those attributed to the other. He disseminates their meaning, rather than wobbling between two poles of

traditional Catholic practice. The manner of this dissemination offers a general insight into Rabelais's enterprise in the most bizarre of his "Pantagrueline Books."

For nearly three hundred years Rabelais's reformulation of Carnival-Lent relations has been blatantly misinterpreted. Portions or all of this episode have been discussed by nearly every critic who has written about Rabelais since the seventeenth century. What is the reason for a critical tradition that has so long and so complacently argued away the contemporary meaning of Rabelais's words?

Rabelais's text has been misinterpreted because its context has been wrongly defined. The problem does not primarily arise from bringing wrong or inadequate information to bear upon the text. It is a question of redefining the relation of text to context. That relation is usually represented theatrically or cinematically: context is the background or stage scenery for text, which is front and center; alternatively the text is seen as a moving picture, a re-presentation or mirroring of the context. In recent decades semiotic critics like Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, and Michael Riffaterre have replaced the theatrical-cinematic model with that of a productive machine. Their key term is "intertextuality": every text is a product of other texts. Tracing the ties of one text with others, showing the linkages and transformations of the semiotic codes used in the whole group of texts, reveals the way in which the particular "machine" in question produces meaning.[10]

[10] Julia Kristeva developed the concept of intertextuality in an essay on Bakhtin, "Le Mot, le Dialogue, et le Roman" (published in Critique [April 1967] and reprinted in her Semiotiké [Paris, 1968], 43–73); see especially 14.5–4.6 and also ch. 8, "La productivité dite texte," in the same book. Both here and in ch. 5, "Intertextuality," of Kristeva's Le texte du roman (Paris, 1970), intertextuality is related to what she calls "carnivalesque structure" whose verbal forms produce a "more flagrant dialogism [Bakhtin's term] than any other discourse (Semiotiké , 161; see also my ch. 1, n. 56, below). Barthes's understanding of intertextuality is different: "By degrees," he writes in S/Z, An Essay (New York, 1974), 211, "a text can come into contact with any other system: the inter-text is subject to no law but the infinitude of its reprises. The Author himself — that somewhat decrepit deity of the old criticism — can or could some day become a text like any other . . . he has only to see himself as a being on paper . . . a writing without referent, substance of a connection and not of a filiation ." Riffaterre's use of the term in Text Production (New York, 1983) is discussed in ch. 8 below. My labeling of intertextual criticism as mechanical refers to the tendency of these critics to discern, behind the surface play of word and theme, the work of a definable set of operations that produce the text. In these writers the organicist metaphors of the "old criticism" to which Barthes refers are replaced by mechanical mathematical ones. "Any text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations, any text is the absorption and transformation of another. The notion of intertextuality replaces that of intersubjectivity" (Semiotiké , 146). Recent work by François Rigolot suggests that this association of intertextuality with mechanical mathematical models, much in vogue during the structuralist trend in the human sciences, is by no means necessary. Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804–1869), Rigolot writes in Le texte de la Renaissance (Geneva, 1982), 19–20, anticipated the basic idea of these intertextual semioticians when he described "any text" in more traditional rhetorical terms "as the 'synecdoche' of another vaster, more complex text which remains to be written."

The theatrical-cinematic metaphor reduces context to a scenic perspective that enhances or coerces writing, as the case may be, but in either case stands outside it. The mechanical metaphor supposes that context consists of other literary works, decomposable like the text in question into neatly separable literary units and reassembled for the purposes at hand. In this case context does enter into the text, and even seems to conjugate it, but only insofar as the context has been reduced to verbal forms.

Rabelais's text does not yield its meanings to such interpretive assumptions. To provide a more adequate model for analysis of the text/context relation requires an excursus to analyze some paratextual elements in Rabelais's works before we return to the puzzles of the Quaresmeprenant-Sausage episode.

1—

Paratexts and Printing

Context neither frames the text nor consists simply of verbal fragments that have been reassembled into a new text. How a text is interlaced with context is illumined and to some extent defined by paratext, a neologism that, like intertext, has value if used with other critical tools rather than as a sovereign methodology. Paratext refers to elements that frame the text, such as the title page, with its indications of title, author, and publisher, the table of contents, dedication, and preface; paratext includes elements scattered through the text such as illustrations, footnotes, and marginal indications or subtitles; it comprehends too a book's format: typeset, binding, size, quality of paper.[1]

Paratexts indicate the forces that have shaped a text: they show how contexts invade the text. But they are also an arena in which the author can, more or less openly, combat such forces. Precisely this is what Rabelais did with the paratextual elements most under an author's control, his dedication and prefaces. In the prologue to the Fourth Book, for example, Rabelais attempts to exercise control over how his book will be interpreted by representing the context in which the book is

[1] Comparison of this brief list with the preliminary discussion of paratext by Gérard Genette, who seems to have invented the term, reveals some differences between his definition and mine; see his Seuils (Paris, 1987), 7–9, and his earlier Palimpsestes (Paris, 1981), 9. These differences stem from a theoretical disagreement: Genette sees the "literary work" as "consist[ing] exhaustively or essentially in a text" which is created by an author. Hence paratext for Genette is above all "defined by an intention and a responsibility [on the part] of the author" (Seuils, 7, 9). I assume, on the contrary, that neither text nor paratext are defined simply by an author's intentions and responsibilities but instead are the consequence of a series of compromises between the author and other persons involved in making a book, most obviously the book's editor and those representing the financial and other interests of a book's publishing house. This is true of "literary works" as of other printed publications. I have developed further this idea of collective creation and compromise in paratext in chapter 8. For a list of other studies of paratextual elements, some of them anticipating Genette's formalization of the concept, see the appendix to François Rigolot, "Prolégomènes à une étude du statut de l'appareil liminaire des textes littéraires," L'Esprit Créateur 27, no. 3 (Fall 1987): 15–18.

being received by his readers. The first words of the text treat readers as if they were being greeted physically by the author: "God save and keep you, worthy people! Where are you? I can't see you. Wait until I put on my glasses. Ha, ha! Lent is going by, well and fair! I see you!"[2]

With the use of a half-dozen interjections Rabelais transforms the text/context twice in three lines, from reading to looking to playing. The "Prologue of the Author M. François Rabelais to the Fourth Book;" continues with a subtitle, "To Well-Disposed Readers" (Aux Lecteurs Bénévoles ); title and subtitle identify this object as an element of written language, as one book among others available to a literate public. But the salutation, "God save and keep you" is an oral greeting. The shift from written to oral representation of the books context is confirmed by the further words "Where are you?" The author looks where he cannot possibly look, and he claims to see.

His seeing is not like that of some omniscient deity. He does not say "I, Rabelais, see you, all of my present and future readers until Kingdom come!" The peeking the author-narrator pretends to do is human, even homely, given intimacy by reference to his glasses and playfulness by means of the words: "Ha, ha! Lent is going by, well and fair! I see you!" These phrases are associated with an old version of the game of "I spy."

The game, "Lent is going by, well and fair," is listed among those that Gargantua played as a boy in Rabelais's earlier book, Gargantua, describing Pantagruel's father. Presumably it was widely known, although historians have thus far not found other contemporary allusions to it. In the nineteenth century the game was played during Lent in Poitou, a region just to the south of the Loire Valley where Rabelais — and his fictitious giants — grew up.[3] There the game was called "capiote," from the Latin capio te, "I catch you" or "I take you." As Léon Pineau described it in 1889, it presupposed an agreement between the children or young people to play the game all through Lent. Morning, noon, or night, each one tried to surprise the other by shouting: "Capiote!" The person who had the lesser number of capiotes at the end of Lent was obliged to buy the winner a small cake on Maundy Thursday.

[2] QL, Pr, 545: "Gens de bien, Dieu vous saulve et guard! Où estez-vous? Je ne vous peuz voir. Attendez que je chausse mes lunettes! Ha, ha! Bien et beau s'en va Quaresme! Je vous voy."

[3] See G , 22, 88. Many place-names in Rabelais's fictions locate the scene in the countryside of the author's childhood around Chinon.

Antoine Oudin, an antiquarian writing in 1656 about "French curiosities explained "Lent is going by" in terms parallel to Pineau, so the idea of the game seems well established.[4] But what does the phrase mean?

In the list of Gargantua's childhood pastimes the game listed just after "Lent is going by" is "I catch you without any green" (or "take you": Je vous prens sans verd) , a May Day game in which one concealed a green leaf on one's person and produced it when accosted with this phrase. Gargantua played gargantuanly: Rabelais lists 216 games, and in the long listing one is often associated with the next. If this is why Rabelais thought of one after the other, then perhaps the phrase "Lent is going by, well and fair" has a seasonal meaning, as the green-leaf game on May Day certainly does: it heralds the change of weather toward fair and mild springtime. However, the phrase may refer ironically to the period of obligatory fasting, an obligation that was not a "good and fair" thing (bien et beau ) in the opinion of many; but for such people, if Lent is passing along, that is well enough.

Rabelais's readers are not addressed from the distance of a writer's study. They are brought into the text as interlocutors, even as players in a game. The text is transformed into a public place, a place of encounter, as if the text's words were determined in some measure by the behavior of the audience. Rabelais creates a narrative frame as open-ended, as indefinite and inconclusive as the conversations of the Pantagruelians in the story, which are often broken into by some accident that interferes with their pursuits.[5] By using this conversational frame, Rabelais places readers in the position of politely responding in kind to his congenial warmth:

[4] Léon Pineau, letter published in "Notes et Enquêtes" section, Revue des traditions populaires 4. (1889): 368. Antoine Oudin, Curiositez françoises (Paris, 1656) explains "Bien et beau" thus: "C'est une sorte du jeu où chaque jour du Caresme, celuy qui dit le premier ces mots à son compagnon gaigne le prix convenu." Oudin is quoted in Michel Psichari, "Les Jeux de Gargantua" Revue des études rabelaisiennes 6 (1908): 351.

[5] Imitation of oral spontaneity and unplanned, inconclusive talk was developed by François Villon, to whom Rabelais frequently refers in the novels. Nancy Regalado analyzed Villon's techniques (breaking off phrases, inserting interjections and digressions, using frequent deixis) in her paper, "Speaking in Script: The Re-creation of Orality in Villon's Testament, " presented at the conference on "Oral Tradition in the Middle Ages," Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, State University of New York at Binghamton, October 22, 1988.

And so? Your vintage has turned out well, as I've been told, and I would never be sorry about that. You have found an infinite remedy against any kind of change, any kind of thirst. That's most virtuously done. You, your wives, your children, your relatives and households, are as healthy as may be? That's good, that's fine, that pleases me.[6]

This feigned warmth and closeness in the address to readers had first appeared in the prologue to the Third Book , published six years earlier (1546).[7] The attitude contrasts with that in the prologues of Gargantua and Pantagruel , where readers are more distantly, although still familiarly, praised and abused as if they were being harangued by a market-place bookseller.[8]

The change is connected with a shift in persona: the "author" of Gargantua and Pantagruel was not indicated in the paratexts of those books. There the narrator calls himself Alcofribas Nasier, an anagram of François Rabelais. Few readers would have been able to unscramble the vaguely Arabian pseudonym and discover the notable doctor and editor of Hippocrates.[9] But "François Rabelais, doctor of medicine," is proclaimed as the author of the Third Book and the Fourth Book on the title pages, and the author's name is used again as part of the titles of the prologues: a certain distance is thus placed between author and narrator of the tales proper, who continues to be Alcofribas.[10]

Text is pulled away from paratext, as Rabelais makes more explicit his representation of himself as an author. There were several reasons

[6] QL, Pr, 545.

[7] The first lines of TL, Pr, 341, parallel the opening of G, Pr, 25, published long before (1534–1535). Readers are addressed with the same jocular praise/abuse and immediately introduced to a learned theme (an additional greeting, "Bonnes gens," added in 1552, will concern us in ch. 9): "Beuveurs très illustres, et vous goutteux très précieux, veistez-vous oncques Diogènès, le philosophe cynic?" This attitude of distant familiarity is exchanged almost immediately, however, for something approaching personal acquaintance; ten lines after the salutation the author pursues: "Vous item n'estez jeunes, qui est qualité compétente pour en vin, non en vain, ains plus que physicalement philosopher."

[8] The marketplace-like settings have been frequently remarked. Bakhtin, Rabelais , 160–71, offers the fullest interpretation of their praise and abuse.

[9] Moreover, the title page to Pantagruel refers to the author as "Feu M. Alcofribas" "the late Master Alcofribas": P , 187.

[10] Alcofribas's name does not appear in the Fourth Book , but Panurge addresses him by his sobriquet "Monsieur the abstractor," and the book's narrator uses the collective "we" to refer to the Pantagruelians. For this and other reasons explained in ch. 8, it seems clear that Rabelais retained his fictive alter ego as narrator of the Fourth Book .

for the change; some involved the general form of the novels and others concerned particular events. Only the latter interest us at this point. Rabelais's first, second, and third novels had been condemned in 1543, 1545, and 1546 by the Sorbonne; the second and third condemnations had been endorsed by the Parlement of Paris; there was a risk that copies of the novels in bookstores would be confiscated and the booksellers fined if not imprisoned.[11] Reacting to this situation with some intrepidity, Rabelais issued a part of the Fourth Book in 1548 with a prologue in which themes and attitudes of the later 1552 prologue carried different overtones. In 1552 the prologue author feigns first not to see the "worthy people" whom he invites to conversation ("where are you? I can't see you"), but he then dissolves the pretense with his playful "Ha, ha! . . . I see you." The atmosphere of sedate ease thus engendered is quite different from that brought about by use of the same phrase in 1548 ("O worthy people, I can't see you!"), for no resolution of the tension introduced by this phrase follows. In its sixteenth-century context to say "I can't see you" meant to protest someone's absence, in this case presumably the absence of the kind of "worthy people" who could protect Rabelais's writings from attack.[12]

Rabelais lashes out with great verbal violence against those denouncing his writings in the prologue of 1548. Four years later his situation had changed. Having gained new support at the French court, Rabelais received a royal privilege to print all his works with the king's protection for ten years to come. The altered situation for his books is reflected in Rabelais's easy tone in the prologue of 1552. He asks about the health of his suppositious readers' friends and relatives and responds with an orotund Christian prayer: "Healthy as may be? That's good, that's fine, that pleases me. May God, the good God, be eternally

[11] Francis M. Higman, Censorship and the Sorbonne: A Bibliographical Study of Books in French Censured by the Faculty of Theology of the University of Paris 1520–1551 (Geneva, 1979), explains the sixteenth-century mechanisms of censorship and condemnation. For Rabelais's condemnations, not especially singled out for study by Higman, see 52, 62, 63.

[12] As explained in ch. 9, the prologue is written with shifting ironic tones, so that even when one can be fairly certain about the text's referents, the meaning of such referents for the author represented in the text, let alone the real author, is not always clear. In QL , Pr 1548, 752, n. 4, editor Boulenger says that the contemporary writer Du Fail and later La Fontaine in his Fables also used the phrase in the sense of protesting someone's absence. Rabelais had already used it that way in G , 3, 204.

praised for it and, if such is his holy wish, may you long continue so." In 1548 the prayer is imploring: "Oh worthy people, I can't see you! May the great virtue of God come eternally in aid to you, and no less to me! There then, by God, let us never do anything without first praising his sacred name!"[13] The concluding declaration of orthodoxy seems almost tailored to belie charges of impiety.

On whom could Rabelais rely besides God? The royal privilege of 1550 was not the first he had received. The Third Book had been published in 1546 with a royal privilege that had not saved it from the Sorbonne's condemnation. Church authority was at least semi-independent from state authority; even the authority of Parlement was not always under the control of the king and his ministers. During the first half of the sixteenth century royal favor had waxed and waned toward those of humanist and evangelist persuasion like Rabelais. He could not feel entirely secure in royal patronage. Others — most signally the learned though impetuous Louis de Berquin and Etienne Dolet — had been burned for their humanist opinions and publications.

Rabelais's firmest source of support was not the king and his ministers but his anonymous readers. By 1552 it is probable that at least fifty thousand copies of Rabelais's first four books had been printed. The vogue of his books would continue after his death in 1553 until the end of the sixteenth century.[14] He was extraordinarily popular. Such massive although remote support was novel; it was due to the invention of printing a century earlier and to the inventiveness of publishers in exploiting new markets of readers.

The problem for Rabelais was how to use this new but anonymous power. Through printing the boundaries of literary influence and re-

[13] QL , Pr 1548, 752.

[14] The figure of fifty thousand copies is derived from multiplying the forty-six editions certainly published by 1552 (NRB , nos. 1–13, 19–51) by eleven hundred copies per edition. One thousand copies seems to have been the more or less normal printing for an author in Rabelais's time. But Aldus Manutius earlier in the century often printed three thousand copies of popular classical authors, and Reformation writings after 1520 also were published in printings much larger than one thousand. See Martin Lowry, The World of Aldus Manutius (Ithaca, N.Y., 1979), 257, 290. Rabelais was a popular author; at least some of the forty-six editions were probably published in runs of more than one thousand copies; there is always the possibility, too, that some as yet unknown editions existed, especially pirated editions of Pantagruel and Gargantua . Some persons also presumably bought single tomes of the multivolume editions among those listed in the NRB . The figure of fifty thousand is one-half the number of "Rabelaisian writings" estimated for the whole sixteenth century by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, L'apparition du livre (Paris, 1958), 415: "Les différents écrits rabelaisiens furent répandus dès le XVIe siècle . . . peutêtre à plus de cent mille, compte tenu des éditions perdues."

sponsibility, usual in the age of the manuscript book, were suddenly opened; given that, he was probably uncertain about the tactic to choose. There were as yet few conventions to follow. Authors derived little income from their publications. The only semblances of copyright were the privileges extended to favored authors or publishers by princes and city councils. Due to the still largely decentralized character of feudal-monarchical society, such privileges were ineffective in preventing pirated editions and even incapable of preventing condemnation by rival authorities. Yet Rabelais could be certain not only that he possessed power but also that this was recognized by those upon whom he otherwise depended. Luther's massively published writings proved that low and obscure men, capable of evoking popular response through the printed book, might move and even overturn church and state. The example of Erasmus's popularity was equally pertinent. The Dutch humanist, who unlike Luther was one of Rabelais's heroes, had both taught and demonstrated that writing seriocomically in a popularizing vein might through the new tool of the printed book be a leavening force.[15]

Printing was Rabelais's inspiration. "You have lately seen, read, and come to know The Great and Inestimable Chronicles of the Enormous Giant Gargantua, " Alcofribas Nasier declares in the prologue to Rabelais's first novel, Pantagruel . "You have often passed the time in the company of honorable ladies and maidens by telling them fine long stories from that book," he continues, and he urges that the Chronicles be committed to memory "so that if the art of printing happened to die out . . . everyone should be able . . . to transmit it to his successors and survivors, as if from hand to hand, like some religious Cabala." "Find me a book in any language, on any subject or science whatever,

[15] Cf. Erasmus's clarion call in the Paraclesis , the paratextual introduction to his new Latin translation of the Greek New Testament (1516), where he states that his ambition is to make the biblical gospels and epistles so available and understandable through translations and commentary that farmers, women, weavers, and travelers might read it as they move about their daily tasks. See Desiderius Erasmus, Ausgewählte Werke, ed. Hajo Holborn and Annemarie Holborn (Munich, 1933), 142. Erasmus's Praise of Folly, Colloquies, and some other of his works are superb examples of popularizing elite culture, and, at least in the opinion of opposing authorities, they were ideologically effective. "Erasmus laid the egg that Luther hatched," the saying ran.

which has such virtues, properties and prerogatives, and I will pay you a quart of tripe . . . . For more copies of it have been sold by the printers in two months than of the Bible in nine years!"[16]

A few letters by Rabelais in Greek and Latin, published and unpublished at the time, remain from the years up to 1532 when this prologue was written. They, like the learned translations and commentaries he also published in 1532, exhibit correct but unexceptional diction. There is little sign of the audacious verve and ironic subtlety of expression that erupt in Pantagruel . Printing, because it was a mode of communication that widened the possible audience immeasurably, seems not only to have served Rabelais as a humanist but also to have suggested to him another, fictive avenue of verbal exchange with readers, calling upon a different level of mind and feeling from that with which he dealt in his scholarly productions.

Not so much a new group of uncultivated "popular" readers but the broadly mixed audiences made possible by printing proved the making of Rabelais as a writer; his audiences were literate and illiterate, serious and mocking, leveling and hierarchizing in feeling, idealist and practical, naturalistic and yet also religious in belief. Printing allowed communication with this varied and variable set of sensibilities. Rabelais pressed his readers to develop in themselves such variability by his paratextual tactics.

With the advent of printing a vast gray space emerged between composition and reception, between sending the text's messages and feedback to author and publisher about them; the prologue narrator's exclamation, "Where are you? I can't see you," carries this nuance, too. How different this was from the situation of pulpit preacher and jongleur, whose orally delivered texts necessarily involved audience encounter. Far from his readers, Rabelais represented his readers as paradoxically near, clustering around a bookstall in the prologue to Pantagruel as Alcofribas extols the exquisite virtues of the Chronicles about Gargantua and its sequel Pantagruel ; sitting in some room with Dr. Rabelais himself in the prologue to the Fourth Book as that affable gentleman inquires about friends and family.[17]

[16] P , Pr, 189–91.

[17] After the opening salutations, as the "conversation" continues, Dr. Rabelais feigns to turn to his books, citing the New Testament and three medical treatises attributed to Galen. Hence one imagines him in some place, perhaps his study, with his books at hand: "Cl. Gal . . . . eust congneu et frèquenté les saincts Christians de son temps, comme appert lib. II, De usu partium, lib. 2 De differentiis pulsuum, cap. 3, et ibidem, lib. 3, cap. 2, et lib. De renum affectibus (s'il est de Galen)" (QL , Pr, 546).

Text/context: paratextual elements like these prologues allow an author to represent his readers and hence to suggest to them how he would like his books to be read . . . and not read. For any representation implies a reality beyond it that differs from the representation. To represent author and reader in the obviously impossible forms of Rabelais's prologues requires the reader to reflect upon the identity of the author behind the simulacrum, to reflect upon his or her own identity in relation to these texts, and hence to separate in greater or lesser degree the reality from the representation. If Rabelais writes of Dr. Rabelais in his parlor or study, receiving worthy well-wishers of his books, one can be certain that he is asking his readers to imagine an author-reader connection that is something other than the one depicted in such a scene.

The manuscript book contained wide margins, filled with glosses. The physical space between the scribe or scholar who wrote and the theological, pedagogical, or otherwise interested reader who commented was broad because the intellectual space between them was assumed to be narrow.[18] The printed book had small margins, just wide enough for a word or two, an emendation, an exclamation, a notch or other sign to indicate interest. It was small because the physical distance between author and reader was large. Because it was large it stimulated authors to develop their manipulative powers, to inveigle readers, and to steer them in directions consistent with their textual purposes. The authors of the printed book had to imagine themselves and their readers in ways quite unparalleled in either oral or manuscript communication. They might move either to induce looseness and inventive digression or to insure compliance.[19] Whatever their tactics, the result

[18] See the first section, "Le temps du manuscrit," and especially the subsection in it by Paul Saenger, "Manières de lire médiévales," in Roger Chartier and Henri-Jean Martin, Histoire de l'imprimerie française, Volume 1 (Paris, 1983). Henry Chaytor, From Script to Print (London, 1945), also remains valuable as is Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, 2 volumes (Cambridge, 1980). Rabelais's fictitious list of the books in the monastery library of Saint Victor at Paris (P, 7, 216–24) is from the point of view considered here less an image of monastic obscurantism and hypocrisy than a representation of the narrow, obsessively glossing mentality encouraged by the form of manuscript bookmaking.

[19] Bakhtin's distinction between "dialogical" (loose, digressive) and "monological" (tight, authorially manipulative) texts, might be said to be related to this difference. See the essays in Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination (Austin, Tex., 1981). This is my suggestion; Bakhtin does not especially concern himself with effects of printing.

separated the represented reader from the reader beyond that representation, holding a real book in real hands.[20]

How did the real reader appear to the eyes of the real author? We cannot be certain of course, but we have several clues. One clue consists of woodcuts, showing scenes of reading, on the title pages of two pirated editions of Rabelais's Gargantua . Neither woodcut was influenced by Rabelais; they are presumably pieces of advertising chosen by the publishers. The publishers, located in southern France, were familiar with the milieus in which Rabelais's books were selling so well: if they chose to represent these reading scenes, it is because they were commonly known and would beckon to the buyer. But because they would have been commonly known, they may be assumed to have been familiar to Rabelais as well and to have entered into his idea of his readers.

The first woodcut, published by Etienne Dolet in the abusively unexpurgated edition of 1542, shows a stout, long-robed gentleman reading from a large book opened on a table before him.[21] His right hand rests on the shoulder of a child of ten or twelve in front of him, who is looking at the book. His left arm grazes the shoulder of another child of the same age (both children seem to be male) while pointing to a line in the book. Two large vessels, seemingly for liquid (one at least seems filled), are placed to right and left of the book on the table. Six men of varying ages crowd in upon the scene of reading, as if to hear what the gentleman is saying. Two or three are represented with open mouths, as if exclaiming in astonishment.

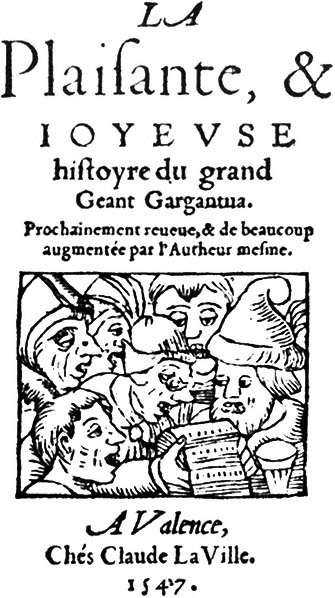

The second woodcut (see Fig. 1), published in 1547 by Claude La Ville in a pirated edition of Rabelais, shows a cluster of people with even more expressive facial gestures in a similar scene of reading. In-

[20] These issues have been explored by, among others, Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader (Baltimore, 1974), Umberto Eco, The Role of the Reader (Bloomington, Ind., 1979), Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Classroom? (Berkeley, 1980), Cesare Segre, Avviamento all'analisi del testo letterario (Turin, 1985), and the authors in S. R. Suleiman and I. Crosman, ed., Reader in the Text. Essays on Audience and Interpretation (Princeton, 1980). They are discussed further in chs. 7–9 here.

[21] See the introduction above for reference to Dolet's edition. NRB , 48, reproduces the woodcut.

1. Anonymous, Title page, Rabelais, Gargantua (Valence:

Claude La Ville, 1547). Phot. Bibl. Nat. Paris.

stead of presenting the central figure frontally, here the reader is shown in profile, peering through spectacles at the open book. A cup or glass stands to the right of the book; is this a tavern scene? The five people listening to the reader crowd around him more closely than the people in Dolet's woodcut. They grimace or gaze with open mouths, bedazed or aghast at the words of the reader bending over his text. This representation shows more lower class and more eccentric people — note their bizarre hats — than that in Dolet's edition; these people express their reactions with toothy directness.

Rabelais mixed appeals to his readers, sometimes addressing "worthy people" like those in Dolet's woodcut and sometimes referring to "poor victims of pox and gout . . . their faces shining like a larder lock-plate and their teeth rattling like the keys on the manual of an organ" as they listen to the Chronicles of Gargantua or crowd around a fellow in tavern or street like those on the title page of Claude La Ville's edition.[22] The complaints of other authors prove — and this is a second kind of clue — that scenes like those depicted in the woodcuts mixed the literate and illiterate inside or at shop doors and other gathering places in the towns. An anonymous prologue to a book about commercial ethics published in 1496 at the French city of Provins complained about "the useless novels and tales which people customarily read so assiduously at the workshops and stores of merchants, where many come to hear and listen to them for [purposes of] vain pleasure."[23]

Printing might be said to have paradoxically stimulated illiteracy no less than literacy because it increased the repertoire and means of entertainment at the disposal of oral performers, descendants of the courtly minstrels who still in sixteenth-century Europe told tales — and now might read them aloud — improvised songs, and broadcast the news in public places.[24] Printing glorified illiteracy, making it profitable both to imitate the modes of oral discourse in writing and to play variations on

[22] "Worthy people": QL , Pr, 752. "Poor victims": P , Pr, 190.

[23] Cited by Dominique Coq, "Les incunables: textes anciens, textes nou-veaux," in Chartier and Martin, Histoire de l'imprimerie , 1: 184.

[24] See Paul Zumthor, La lettre et la voix de la "littérature" médiévale (Paris, 1987), 67–80, who shows that the tendency of oral performers at court and in town to introduce written elements in their recitations begins almost with the first notices we have of their courtly existence in the tenth century. The mixture of oral with written elements, therefore, rather than the exclusion of one or the other, is characteristic of such performers, who continued to exist in some parts of Europe well into the twentieth century.

oral turns of speech, proverbs, and jokes.[25] The relation between oral and written forms of verbality both sharpened the distance between them (writing now passed through a more or less complex process of editing and printing before becoming public) and made it possible to recognize more easily their ultimate inseparability. Any written communication presupposes oral communications concerning the same subjects or using the same words in other connections. And vice versa: disconnecting oral from written forms of human exchange or giving priority to one over the other is in a philosophic sense a phonocentric or graphocentric illusion, depending on whether the oral or written side is accorded sovereign power. The sources of language do not lie on one side as opposed to the other but in the two sides' interplay, in utterance combined with inscription.[26]

Rabelais exploited the interplay by representing what was written not only as if it were taking place orally but also in a more general sense. "Rabelais writes prose which, when read, . . . gives the illusion of lis-

[25] The inverse is equally true and has received more attention from scholars: Printing brought letters to the unlettered in new ways. Towns in particular were plastered with print, now that public proclamations of every kind could be cheaply reproduced. Those who could not read were in the presence of written documents at church, on the job, and in the streets in unprecedented ways, and this atmosphere of literacy formed their consciousness no less than that of the lettered. On this subject, see Natalie Z. Davis, "Printing and the People," in her Society and Culture in Early Modern France (Stanford, Calif., 1975), and Roger Chartier, "Stratégies éditoriales et lectures populaires," in Chartier and Martin, Histoire de l'imprimerie , Volume 1.

[26] In a historical sense with reference to circumscribed communities one can of course often establish the priority of written over oral or of oral over written communication. The more general perspective alluded to in these sentences, developed particularly in the work of Martin Heidegger (e.g., On the Way to Language [New York, 1971]) and Jacques Derrida (e.g., Of Grammatology [Baltimore, 1974]) may serve to remind us that oral communication has frequently been accompanied, even in cultures "without writing," by inscriptive and mnemonic devices that resemble it, from the bone scratches that, Alexander Marshack supposes (The Roots of Civilization [New York, 1971]), represented Pleistocene humanity's way of calculating fertility cycles, to the mantic sticks that, Ferdinand de Saussure once suggested, were the means by which Sanskrit sages retained in memory their phonemically complex hymns; cf. S. Kinser, "Saussure's Anagrams; Ideological Work," Modern Language Notes 94 (1974.): 1119–22.

During the time this study has been in gestation, the climate of opinion has already begun to shift from revisionism in favor of the claims of orality against literacy in art (Walter Ong, Presence of the Word [New York, 1967], Paul Zumthor, Introduction à la poésie orale [Paris, 1983], etc.) to arguments stressing the interaction of written and oral models of verbal communication in nearly all artifacts, artistic and nonartistic, whether performed in oral or written ways. See, e.g., Tony Lentz, Orality and Literacy in Hellenic Greece (Carbondale, Ill., 1988); and Carl Lindahl, Earnest Games: Folkloric Patterns in the Canterbury Tales (Bloomington, Ind., 1987).

tening to a supremely skilled oral performance."[27] In other passages, however, he reverses this procedure and wearies the reader's eyes with long lists of items whose significance emerges best from their visual presence in written rows over which the eye can rove back and forth, comparing and contrasting. The list of the books of the monastic library of Saint Victor in Pantagruel is one example; enumeration of the parts of Quaresmeprenant's anatomy in the Carnival-Lent episode of the Fourth Book is another.

I suggested that paratext is a linking place between elements proper to a book's composition and elements related to a book's reception. Investigation of this place of linkage will be helpful in explaining the misinterpretation of Rabelais's idea of Carnival and hence ultimately of critics' idea of the text as carnivalesque. Rabelais's paratextual elements constitute a series of feints and mixtures of tactics, favored by the relatively new character of printed book production. How did such feints and mixtures serve Rabelais's ends, which at the very least included that of being able to continue to publish? How did such tactics counter the attacks on him, attacks of which he took almost frenzied notice in the Carnival-Lent episode, denouncing the "maniac [Guillaume] Postels, the demoniacal [John] Calvins, the crazy [Catholic theologian Gabriel Du-] Puy-Herbaults . . . catamites and cannibals" who condemned his books[28]

Rabelais was a dependent person economically and politically. Unlike the career-seeking, back-biting intellectuals in his time, he does not seem to have sought to rise above that condition. One might guess — but it is only a guess, an argument from silence more than from facts — that he even sought mediocre obscurity in arranging his life and career. Because he did not write from a position of power, he had to write from a place of concealment, almost like a guerrilla fighter whose allies are anonymous and changing, depending on circumstances. Rabelais

[27] Carol Clark, The Vulgar Rabelais (Oxford, 1985), 62.

[28] QL , 32, 651. I follow the form of the name of the last-named person used by Eugenie Droz in her "Frère Gabriel DuPuyherbault, l'agresseur de François Rabelais," Studi Francesi 10 (1966): 401–27.

did not simply imagine this tactic; he was stimulated to do so by the newness of the printer's art. He drew upon the power of his numerous but remote readers by crossing boundaries made uncertain by the advent of printing.[29] Thus, we have noticed how he crossed the new gray space, removing reader from author through the printed book by representing readers in oral rapport with a series of authors — Alcofribas, Dr. Rabelais — who necessarily bear only an oblique relation to the real author writing about them. He crossed the frontiers between a number of genres of elite and popular literature by varying his rhetoric, mixing jokes with theology or medicine and Carnival topics with high seriousness. He also scrambled the boundaries between oral and written modes of writing. Let us briefly return to consideration of this third way of developing an anonymous popularity.

The new distance between author and reader imposed by printing stimulated recognition of the fact that writing like speaking never relies simply on words to communicate. Face-to face communication supplements the voice with gestures and clothes and bodily stance. In written communication various marks must be substituted for these supplements. Even in the medieval period of the manuscript book, separations between paragraphs and chapters, capitalization, punctuation marks, and other instruments irrelevant to orally oriented literature had been worked out.[30] With printing such aids were further elaborated by means of the paratextual elements mentioned earlier: title pages with identifying emblems, typeset, size of the printed page, paper quality, and so on. But for Rabelais's purposes all this seems inadequate. He seems to want to lean out of the page to accost readers with onomatopoeic, rhythmic, emotive utterances ("Ha, ha!" exclaims Dr. Rabelais), utterances that lead over the book's margins toward games and dances

[29] "A 'tactic' [is] . . . a calculus which cannot count on a 'proper' (a spatial or institutional localization) [sic ], nor thus on a borderline distinguishing the other as a visible totality. The place of a tactic belongs to the other . . . . Many everyday practices (talking, reading, moving about, shopping . . . ) are tactical in character. And so are, more generally, many 'ways of operating': victories of the 'weak' over the 'strong' . . . , clever tricks . . . , joyful discoveries, poetic as well as warlike." Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley, 1984), xix.

[30] Paul Saenger's "Manières de lire," on the other hand, reveals the astonishing extent to which written literature in antiquity and the early Middle Ages remained wedded to oral models, ignoring the marks and distinctions mentioned in this sentence.

and popular theater. Then again he seems to withdraw into a medically professional anonymity, as in the descriptions of Quaresmeprenant in the Fourth Book . Rabelais's tactics acknowledge the otherness of nonverbal communication and seek to turn it to the printed text's profit by imitating those modes of everyday behavior with which he was especially familiar. The context is given opportunity to enrich the text throughout, not simply in its paratextual elements. Context permeates the text.[31]

The cumulative effect of these boundary crossings and mixtures is not simply to demand a great deal of knowledge and a nimble wit in order to seize an author's nuanced references; it is also to foster a kind of cunning. If readers are not prepared to shift and swerve with the feints of the author, they cannot apprehend the text. Printing brought immense new pressures to bear upon authors from state and church; these authorities were not interested in nimble wits, let alone cunning; they were concerned with security. The apparatus of the title page, indicating place, date, and printer's or publisher's name, was of course an economic advantage, telling buyers where to find the book; but it was also a means of political control, allowing the state to find and condemn suspicious books and booksellers. Printing increased the author's freedom by distancing him from official as well as unofficial readers. But printing also increased the pressures on the author to conform, on one hand to public opinion in order to sell and on the other to official opinion in order to avoid arrest of the books or oneself.[32]

To thwart these pressures Rabelais sought to stimulate cunning; he also tried something else. His gaiety of spirit, which comes from many sources and serves many ends, was at least in part a political attitude, if not at the beginning of his fictional writing in 1532, then certainly by 1545 or 1546 when he elaborated the Fourth Book after repeated condemnations by the Parlement of Paris and the Sorbonne. By means of laughter Rabelais sought to contact his readers in ways that would pry them loose from the demands of special interests and self-serving dogmatisms:

[31] The attentive reader will have noticed that my use of the word "context" has varied — with the context. The word has unavoidably different meanings, distinguished in Appendix 1.

[32] Judicial execution of printers and booksellers began in the 1520 in France in the name of religious conformity. It is a bloody tale. See the section, "Le livre et les propagandes religieuses," in Chartier and Martin, Histoire de l'imprimerie , Volume 1.

Amis lecteurs, qui ce livre lisez

Despouillez-vous de toute affection,

Et, le lisant ne vous scandalisez:

Il ne contient mal ne infection

. . . . . . . . . .

Mieux est de ris que de larmes escripre,

Pour ce que rire est le propre de l'homme.

Friendly readers, you who read this book,

Do strip yourselves of every predilection,

Do not find scandal, reading it,

It has no evil nor infection

. . . . . . . . .

To write of smiles, not tears, is best,

For laughter is the proper quality of man.[33]

Rabelais's playfulness with readers, his digressive fables and tales, his obscenities, his scatology are frequently political in Bakhtin's sense of dethroning official pretentiousness; they are always political in the more general sense of thwarting orderliness with laughter.[34] Rabelais is a popular author not because he wrote for a certain class of people but because he wrote for a certain aspect of mind — an aspect given its due by nearly everyone some of the time. One of Rabelais's most effective feints was to represent his alter egos, Alcofribas and Dr. Rabelais, as if they were continuously in this state of mind, assisted by copious wine.

The Rabelaisian text is suffused with an atmosphere of leisure and pleasure: hence its relation to Carnival; hence the (limited) justice of certain critics' qualification of the text as carnivalesque; hence also Rabelais's recurrent imitation of oral communication. In the vagaries of talk, through the unforeseeable deviations of common language employed in common conversation, the spirit relaxes; it becomes pliable and receptive to excess, deviation, violation of norms.

Were these maneuvers politically successful? The Fourth Book , when it appeared, was immediately condemned. The royal privilege included in its paratext did not inhibit the Parlement of Paris from condemning the book on the advice of the Sorbonne on March 1, 1552. On April 8, 1552, the Parlement forbade sale of the Fourth Book , pending King Henry II's review of the case. That is all we know. About the time of

[33] G, title page, 24: This "dizain" by the author occupies the reverse of the title page of Gargantua . Thus once Rabelais began publishing Gargantua and Pantagruel in order, with Gargantua first, these were the first words of the author's text.

[34] For this aspect of Bakhtin's work, see the discussion at the end of ch. 1.

Rabelais's death in early 1553 the Fourth Book was published in several more editions in 1552 and 1553; the Fifth Book , probably based on drafts found among Rabelais's papers, was published in 1564. Thus just as in the case of other heretics (Rabelais's works were condemned one and all by the Roman Catholic Index in 1564), the conflicting jurisdictions of ecclesiastical, monarchical, and administrative bureaucratic powers seem to have allowed publishers by and large to print with impunity whatever they could sell.

It is too easy simply to look backward and take the represented author's side: Dr. Rabelais was the good guy and so the wise King Henry and his astute councillors supported him; the "demoniacal" Calvin, the "crazy" Catholic theologian DuPuyherbault and their ilk were wrong, evil-minded men. Such conclusions elide the context and make Rabelais's text ultimately less understandable.[35] Rabelais's support at court probably fluctuated less in accord with perception of his virtue or literary worth than in relation to political dangers from Rome, from Germany, and from rebellious, Protestant-inspired subjects. We have already suggested this by referring to the difference in tone between the two prologues that Rabelais published to his Fourth Book . The one published in 1552, with its Lenten game and calm prayer, was jovially sedate; the other, published in 1548 after the third condemnation of his books, was imploring in its prayerfulness and accusatory with respect to Rabelais's slanderers: "caphards, cagots, matagots . . . pope's parasites . . . pardoners, catamites," "some kind of monstrous race of barbarous animals," "black and white, domestic or private devils," "lunatic fools, bug-

[35] Robert Marichal has done excellent work on the circumstances of censure and publication of QL in his edition of that book (Geneva, 1947) and in "Rabelais et les Censures de la Sorbonne," Etudes rabelaisiennes 9 (1971). But his conclusion in the latter study takes Dr. Rabelais too complacently at his own word and argues too positively from silence about the attitudes and power of his friends at court: "Il ne s'agit pas de méconnaître la puissance de la Sorbonne et du Parlement, mais François Ier n'avait-il pas trouvé, dans le Tiers Livre 'passaige aulcun suspect' et eu 'en horreur' ses calomniateurs? Les Réformés n'ont-ils pas, en avril 1547, fondé de grands espoirs sur Henri II? . . . Rabelais ne s'est donc pas trompé sur le crédit de ses protecteurs auprès du roi et sur l'étendue de leur pouvoir: ils ne lui ont pas plus manqué en 1546 qu'ils ne lui manqueront en 1552" (150). The words quoted by Marichal are from Rabelais's dedicatory letter to the Fourth Book , discussed at length in my ch. 9. Marichal's earlier conclusions about the censure of the Quart Livre were more tentative and more substantive. See his "Quart Livre: Commentaires," Etudes rabelaisiennes 5 (1964.): 124–27, 132–33.

gers and bastards' let them all go "hang themselves" before the new moon rises![36]

The public scene between 1545 and 1548 provided justification for this near frenzy, whether feigned or genuinely felt.[37] In January 1545 a secretary to Cardinal Jean du Bellay, Rabelais's patron and protector, was burned for heresy, and the following year Rabelais's sometime friend, Etienne Dolet, was burned publicly at Paris for the same crime. The long-awaited Council of Trent began in a manner that augured little hope for Catholic liberals like Rabelais and Jean du Bellay. In the Smalkaldic War of 1546–1547 Emperor Charles V crushed the Protestant forces with whom the French king had been allied. On March 31, 1547, King Francis died, replaced by his young son Henry, whose political inclinations were not clear. He was closest to the conservative and peremptory Constable Montmorency. The iron age of force and orthodoxy of Francis I's last years threatened to continue.[38]

Then, as Rabelais perfected the Fourth Book between 1548 and 1552, the political atmosphere lightened. Montmorency showed himself no extremist and, in spite of his hatred of Lutheranism, remained committed to his family ties even with such religious liberals (and eventual Protestants) as the Châtillon brothers. One of these, Cardinal Odet de Châtillon, made himself responsible for a new royal privilege in 1550, protecting Rabelais's books.[39] Awareness of new support in 1549 or 1550 from the king's closest advisers contributed, according to the author in a dedicatory letter to Cardinal Odet, to the swell of novelistic energy and ingenuity displayed in the second edition of the Fourth Book .[40]

That swell of energy, like the towering anger that preceded it in the

[36] QL , Pr 1548, 755–58.

[37] Irony is never far from Rabelais's textual strategies. The question is further explored in ch. 9.

[38] See Screech, Rabelais , 207–14, 293–303, 321–26, for a narrative of political changes in the late 1540s. Henri Hauser and Augustin Renaudet, Les débuts de l'âge moderne (Paris, 1956), 486–91, remains an accurate and more general summary of French policy in the 1540s. The eventual turn toward more rigid religious orthodoxy in Henry II's later years was not clear in 1547–1550. For one thing Jean du Bellay was on cordial terms with Montmorency, while Montmorency had political reasons to resist the influence of the repressive Cardinal Tournon over the king.

[39] See the reference to this at the beginning of ch. 1.

[40] For additional details about the censorship threatening Rabelais and the aid which Odet de Châtillon gave to him, see Rabelais, Quart Livre , ed. Marichal, x–xvi.

old prologue of 1548, had another source: the absence of institutions in the sixteenth century that could have coherently channeled response and interpretation of Rabelais's works to the author and to church and state authorities. Rabelais rehearses his good faith and innocence of all ideological wrongdoing in the old prologue by suggesting that his readers grant his writings total approval: "What? You say that you have not been irritated by anything in all my books printed up to now?" He attributes royal favor to himself: "Well, then, I shall certainly not irritate you either if I mention to you the saying of an ancient Pantagruelist, who says: 'It is no common praise to have been able to please princes.'"[41] Rabelais is able to construct an image of public opinion so entirely favorable because no one could measure what that opinion was. He constructed it gaily, of course, not only expecting that readers would recognize its exaggeration but also knowing that readers could not possibly judge just how exaggerated it was.

Nor could Rabelais himself. Printing, with its fundamental restructuring of the circulation of words and ideas, did not automatically create that complex network of critical reviews, authorial interviews, editorial analysis, and publishers' marketing research that over centuries has emerged to guide and constrain decisions to publish or suppress an author's work. Literary criticism had just begun to take shape as a discipline based on something more than moral or theological principles. Literature did not yet exist as a university subject separate from the study of grammar and rhetoric.[42] There were no research libraries, no scholarly gatherings,[43] no means of obtaining and consolidating opinion about any of the far-flung topics, political and scientific, professional and commonplace, to which Rabelais devoted attention. How could informed opinion about his polymorphic novels possibly

[41] QL , Pr 1548, 754. The "ancient Pantagruelist" is Horace: Principibus placuisse viris non ultima laus est .

[42] Literary criticism took on considerable sophistication with respect to the editing and exegesis of ancient authors. Philological and amateur enthusiasm cooperated to create some beginnings, too, in the analysis of modern authors, particularly with respect to their near or far imitation of the ancients. But this activity had as yet scarcely any conceptual unity and hence could call upon neither analytic norms nor institutional support.

[43] I refer to conferences of otherwise distant representatives of a field of inquiry, like those for example that brought together theologians, and not to the more informal sodalities of local amateurs that flourished in the Renaissance and were the forerunners of academics.

emerge? All that existed in Rabelais's time were the two extremes of this eventual system of rationalization, normalization, invention, interpretation, and control: bookselling on one hand, and on the other inquisitorial committees dedicated to stamping out dissent from the official opinions of which they were the instruments.

If it was not wrong for booksellers to circumvent the decisions of the committees, by placing false names or none at all on their title pages, so also it was not evil of the committees to seek to suppress these circumventions and the — to them — pernicious originals disrupting public order. Books are social, not only cultural, tools, and they can cut deeply. All social fractions, including the governmental, therefore have a legitimate interest in what is published, and an author soon or late, consciously or unconsciously, takes a position in relation to them. Paratexts are the best clue to such assumed positions. Paratexts indicate at the very least how near or far a writer aspires to be from the social conflicts amid which and by means of which the text was composed.

On the other hand, by the very decision to give written and hence preservable form to words, a writer's work takes its place at some distance from social circumstances. Writers who give printed form to their words are especially distant because printing not only elongates the channel of communication between senders and receivers but also multiplies mediators between them, each with their own interests. In the case of a popular author like Rabelais this mediating position between author and public is not simply that of the collaborating patrons, financiers, printers, editors, licensers, and booksellers who bring the book to birth. It is also that of the offices of public opinion, formal and informal, that in the fifteenth and the sixteenth century were shaken to their foundations first by printing, then by Protestantism, and then by the two in conjugation.

These changes in the way words were circulated threw authors into confusion no less than their friends and enemies. Authors as they write inevitably imagine their readers, whether or not they represent that image, as Rabelais did in his prologue to the Fourth Book . The image is the response to a "conversation" with readers that goes on silently as one writes. Authors' attention is divided between fabrication of the message and those for whom it is intended.[44]

[44] These points are raised in a different manner with respect to Rabelais by François Rigolot, Le texte , 138–44. My use of "represented" or "imagined" reader corresponds to Wolfgang Iser's "implied reader" (implizite Leser: see ch. 1, n. 20) and to Rigolot's "'narrataire.' interlocuteur du narrateur," a term Rigolot (140) borrows from Gérard Genette.

The few messages received from Rabelais's early readers that we in the twentieth century have been able to discover seem, in the light of what we think about Rabelais's text, mostly ignorant or absurd. [45] The first to emerge emanated from Rabelais's literary friends and hence might be discounted as self-interested. Humanists were notorious for praising and damning each other in order to develop their reputations, a tactic encouraged by the absence of more regular institutions of criticizing and advertising.[46] In the short poem by Hugues Salel, which first appeared on the reverse of the title page of the eighth edition of Pantagruel in 1534, in a Latin poem by Jean Visagier, in a passing reference in one of Clément Marot's facetious versifications, Rabelais is a great poet, a laughing writer, a Democritus reborn.[47] Meanwhile the condemnations were already circulating; Pantagruel was gossiped about as an "obscene book" by learned men or ecclesiastics in autumn 1533, only a year after its appearance.[48]

[45] I list five proto-critical attitudes here, based on the investigations of Lucien Febvre, The Problem of Unbelief (see esp. Book One, Part One), Marcel de Grève, L'interprétation de Rabelais au XVIe siècle (Geneva, 1961), and Michael Kline, Rabelais and the Age of Printing (Geneva, 1963). The matter requires reformulation. Grève and Kline offer source listings without any model of the critical possibilities in the sixteenth century structuring these responses. Febvre's investigation of poetic, humanist, and theological circles to which Rabelais was related or in which Rabelais was discussed is less aimed at reconstructing the consistency or variability of the principles of discussion than at disproving the charge in some of these circles that Rabelais was seriously believed to be an atheist.

[46] The absence explains the practice of publishing letters to and from famous and not-so-famous humanists, a practice that, together with the philological and editing activity referred to in n. 42, created the sense of a cultural community, the "republic of letters," with its own hierarchies of prestige. This system of mutual recognition was no adequate organ of critical analysis, but it should be mentioned, in addition to the widespread grammatical-rhetorical commentaries on "auctores" by humanist school teachers, as a third, relatively institutionalized mode of elaborating literary interpretation, along with the two extremes mentioned earlier: sales and inquisitorial committees.

[47] Salel's poem is reprinted, P , 188. On Visagier's poem, see Febvre, Le problème , 34–35; and on Marot, see Grève, L'interprétation , 38–39.

[48] Grève (L'interprétation , 16) cites a letter by Calvin to a friend, written in October 1533. Grève assumes that Calvin reports the opinion of Nicholas Le Clerc, a Sorbonne master; however, Calvin's phrasing is such that his reference to "obscene books which should be damned [like] Pantagruel " may reflect Calvin's opinion rather than Le Clerc's.

After such simplistic good and bad judgments came the more serious disrepute of Rabelais in fashionable circles, a disrepute popularized after Rabelais's death by persiflage in poems like Pierre Ronsard's comic epitaph depicting the writer wallowing amid spilt wine "like a frog in mud."[49] Such satire reinforced the rabid attacks of Catholic controversialists like Gabriel DuPuyherbault, who depicted Rabelais as a drunkard and glutton "who does nothing everyday but . . . sniff kitchen odors and imitate the long-tailed monkey."[50]