Plates

The plates in this book range from images of people to images of houses and temples to images of life-cycle ceremonies. They are drawn from a variety of sources, including Nakarattar publications and other documents of the colonial period as well as photographs of contemporary architecture and rituals.

The Public Image

Nakarattars were known to colonial society as archetypal merchant-bankers. Plate 1 portrays a Nakarattar banker in Colombo, a visage known by Nakarattar clients throughout India and Southeast Asia. Plates 2 and 3 show S. Rm. A. Muthia Chettiar, the most visible representative of the Nakarattar community to the colonial government, in two of his most prominent roles: in Plate 2 as Mayor of Madras (1932) and in Plate 3 as Minister for Education, Health and Local Administration (1936–37). See Chapter 7.

Plate 1.

A Nakarattar banker in Colombo (1925).

Reprinted from Weerasooria (1973)

by permission of Tisara Prakasakayo Ltd.

Plate 2.

Raja Sir Muthia as first Mayor of Madras (1932).

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 3.

Raja Sir Muthia as Minister for Education,

Health and Local Administration (1936).

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Political Constituencies of Raja Sir Muthia

As with Plates 2 and 3, Plates 4 through 8 are reproduced from the commemorative volume published for Raja Sir Muthia's sixtieth birthday celebration (shastiaptapurti kalyanam ), and date from the period before he received his knighthood and the title "Raja Sir." The photographs illustrate many of the Raja's political connections, discussed in Chapter 7: the Banking Enquiry Committee on which he served in 1929 (Plate 4), the Justice party upon his election as Chief Whip and Chairman in 1930 (Plate 5), prominent supporters from Karaikudi on the occasion of his election as Mayor of Madras in 1932 (Plate 6), members of the South India Chamber of Commerce in Madras, likewise posing with him at a reception in celebration of his election in 1932 (Plate 7), and finally, his father, Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar, with members of the Indo-Burma Chamber of Commerce in 1935 (Plate 8).

Plate 4.

Banking Enquiry Committee (1929); Raja Sir Muthia second from right.

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 5.

South India League Federation (Justice Party) on Muthia's election as

Chief Whip and Chairman (1930). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 6.

Supporters from Karaikudi Municipality on Muthia's election as Mayor

of Madras (1932). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 7.

Supporters from South India Chamber of Commerce on Muthia's election

as Mayor of Madras (1932). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 8.

Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar (seated, right) in England with members

of the Indo-Burma Chamber of Commerce (1935). Reprinted from Annamalai

University (1965).

Houses

The hybrid Anglo-Indian political style reflected in colonial dress and title are also reflected in the magnificent vernacular architecture of Chettinad. This style is illustrated in the increasingly elaborate Nakarattar versions of the Anglo-Indian bungalow, aptly described as "country forts" (nattukottai ). Chapter 6 draws attention to the valavu (the central courtyard, surrounding corridor, and double rooms for pullis or conjugal families) from which many Nakarattars derive the name for their joint families. A floor plan for a relatively simple Nakarattar house (Plate 9) illustrates this feature along with an outside veranda for guests in the front of the house, a small courtyard in back for cooking, and a separate room for women "polluted" by various life-cycle crises.

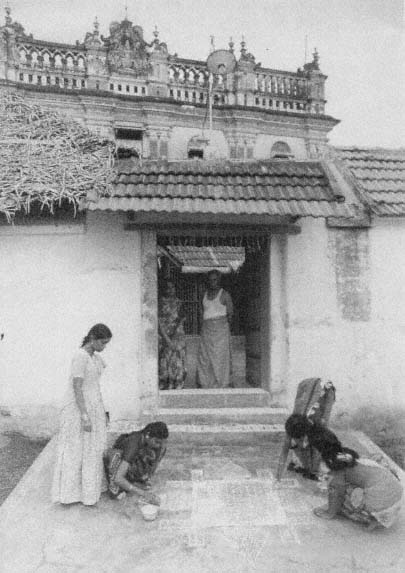

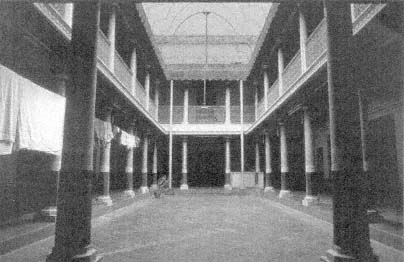

All Nakarattar houses share this division into a front "male" section, a central ceremonial section, and a rear "female" section. From the last quarter of the nineteenth century on, however, Nakarattars elaborated on this common theme, adding on extra rooms around the central core and incorporating a variety of colonial architectural motifs, ranging from Mughal-inspired towers to niches with sculptures of Queen Victoria. Such elaborations are depicted in the floor plan of a more elaborated Nakarattar house (Plate 10) and in the following four photographs of Nakarattar houses. Plate 11 captures the facade from a relatively simple Nakarattar house in Attankudi. Plate 12 shows the daily activity of Nakarattar women drawing a kolam (auspicious design) in the street before the front entrance to their house. Plate 13 is reproduced from Raja Sir Muthia's sixtieth birthday celebration commemorative volume and shows his highly elaborate Chettinad "Palace." Plate 14 captures a detail from a gateway to the palace in which the demon devotees of Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth, have been replaced by British soldiers. Plate 15 shows the central courtyard in the Chettinad Palace's elaborate two-storied variant of the Nakarattar house. Further analysis and photographs of Nakarattar houses may be found in Palaniappan (1989) and Thiagarajan (1983, 1992).

Front (Male) Section of House

1. Veranda.

Central, Ceremonial Section of House

2. Hal vitu or vitu: first courtyard; literally, "hall house."

3. Tontu: columns.

4. Melpati, tinnai: a raised platform on which people sit, usually under the veranda or on either side of the door of the house.

5. Valavu: aisle or corridor surrounding central courtyard; central section of house including central courtyard, aisle, and inner and outer rooms; entire house.

6. Ull arai: pulli's inner room for puja and storage of dowry items.

7. Veli arai: pulli's outer, "conjugal" room.

Kirpati: raised sitting platforms in front of each arai (not shown).

Back (Female) Section of House

8. Kattu: second courtyard, women's courtyard; where grains are dried, foods are prepared, and water is stored.

9. Samayal arai: kitchen.

10. Kutchin: a small room for women during their menses and for girls during their coming-of-age ceremony.

11. Veranda.

12. Pin kattu: open garden space with or without well.

Tottam: garden (not shown).

Kenru, keni: well (not shown).

Plate 9.

Plan of ground floor of a "simple" Nakarattar house.

Source : Thiagarajan (1983).

Front (Male) Section of House

1. Munn arai: front room.

2. Murram: courtyard.

3. Talvaram: corridor.

Central, Ceremonial Section of House

4. Kalyana kottakai: marriage hall.

5. Patakasalai, tinnai: the "public" room in a house.

6. Bhojana salai: dining hall.

7. Veliarai: outer room.

8. Ullarai: inner room.

9. Irantam maiya arai: second central hall.

10. Murram: courtyard, roofed or covered with grill work.

Back (Female) Section of House

11. Murram: courtyard, roofed or covered with grill work.

12. Talvaram: corridor.

13. Kalanjiyam: store room.

14. Samaiyal arai: kitchen ("cooking room").

15. Pin kattu: backyard.

16. Keni: well.

Plate 10.

Plan of ground floor of an "elaborate" Nakarattar house.

Source: Palaniappan (1989).

Plate 11.

Nakarattar house, Athankudi. Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 12.

Women drawing kolam (auspicious design) in front of Nakarattar house.

Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 13.

Raja Sir Muthia's "Palace" in Chettinad. Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 14.

Detail of gateway to Chettinad Palace, showing Lakshmi and British "Guardians."

Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 15.

Interior courtyard of Chettinad Palace. Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Temples and Charitable Endowments

Nakarattar house construction in Chettinad shares much in common with house construction in other parts of South India (see, e.g., Daniel 1984, Moore 1990) and indeed with other architectural forms—most notably, temples. All such forms are influenced in varying degrees by a complex set of iconic architectural principles based on Hindu religious ideas about cosmic creation, sacrifice, and regeneration (cf. Beck 1976b; Daniel 1984; Kramrisch 1946; Meister 1983, 1986; Michell 1988; Moore 1990; Varahamihira 1869–74: Chs. 53, 56). The central idea is that properly designed buildings (kattitam: literally, "bounded spaces") represent an image of the personified Hindu universe in microcosm: creation spreading outward toward the eight cardinal directions from a central point where formless divinity is manifest, worshiped, and celebrated in ritual. The center/periphery contrast already noted for Nakarattar houses constitutes only a specific version of this core theme, which is expressed most dramatically in the relationship between the sanctum of the temple (Sk: garbagrihya , Tm: karpakkirikam: literally, "womb room") and its outer walls (cf. Meister 1986).

The floor plan for Ilayathakudi Temple (Plate 16) illustrates the relationship between central sanctum and peripheral shrines. In addition, it also reflects an architectural concern for locational significance defined along both a front-back axis and a right-left axis. The front-back orientation, already remarked in the case of houses, is reflected in Ilayathakudi Temple by the outward and easterly gaze of the temple's principal deity, Kailasanatasvami (Siva) and the inward, westerly, devotional gaze of devotees as they enter the temple through the pillared hall (muna mantapam ) and towered gateway (koparam ). The right-left orientation, expressed in Nakarattar houses by the placement of the kitchen (samayalarai ) and of the room for the seclusion of women, is expressed in temples by the location of the kitchen (matappalli ) and of a shrine for demon devotees (yakasalai ). In both the house and the temple, relatively pure entities and activities are positioned on the right-hand side of the divine center, and relatively impure entities and activities on the left-hand side.

The multiplicity of shrines to secondary deities in Ilayathakudi Temple is obvious (their names are given a Tamil transcription in the floor plan, Plate 16). Invisible is the division of honors (maryatai ) in the yearly round of rituals among different "shareholders" in the temple (kovil pankalis ). Also invisible is the rotation of rights (murai ) to sit on the temple board of trustees and the political interplay among trustees and other prominent members of the temple clan concerning any allocation of temple resources or conduct of ritual practices. See Chapter 7 for discussion.

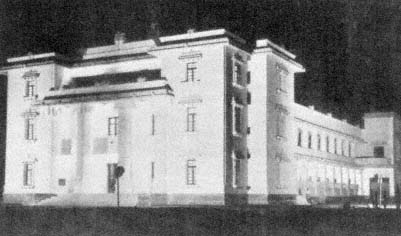

Their apparent architectural invisibility notwithstanding, many of these political properties of the temple influence the construction of secondary shrines and the performance of rituals at all shrines—including, for example, the allocation of separate shrines to Ganesh (Tm: Kanapati —the elephant-headed son of Siva) to temple members from Peramaratur, Perasantur, and Sirusettur. A local historical reading of Ilayathakudi Temple is beyond the scope of the present study, but evidence suggests that temple architecture should be seen not only as reflecting general cosmo-logical principles, but also as reflecting and constituting locally specific political processes. Photographs of Iraniyur Temple (Plates 17 and 18) provide a glimpse of the material consequences of Chettinad ritual politics. A parallel secular manifestation is illustrated by the Raja Annamalai Mandram (music academy) in Madras (Plate 19; again, see Chapter 7 for discussion).

Plate 16.

Floor plan of Ilayathakudi Temple. Based on a drawing by V. Thennappan, Devakottai, July 5, 1981.

Plate 17.

Iraniyur Temple (exterior). Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 18.

Iraniyur Temple (interior of mandapam). Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 19.

Raja Annamalai Mandram (music academy and auditorium).

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Life-Cycle Ceremonies

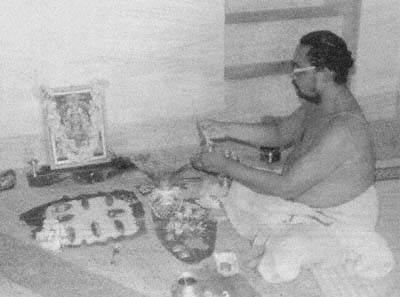

Ancestor worship forms part of a continuum of religious practice that mixes seamlessly with the worship of village and Sanskritic deities (see Chapter 10). Photographs of a family's founders are often displayed over the front entrance to the central courtyard of a Nakarattar house, alongside notable members of Indian society. In many houses these photographs might also be interspersed with paintings of Hindu gods and goddesses. Plate 20 shows a family priest (purohit ) making daily puja offerings at the family shrine (sami arai ). Similar devotions figure into life-cycle ceremonies that play important roles in both the reproduction and the transformation of Nakarattar culture (See Chapter 9). Plates 21 through 23 illustrate scenes from the renewal of a marriage alliance between two families at a second wedding ceremony performed for the couple on the occasion of the groom's sixtieth birthday (his shastiaptapurti kalyanam ).

Plate 20.

Priest performing puja in family shrine (sami arai ). Photo by Peter Nabokov.

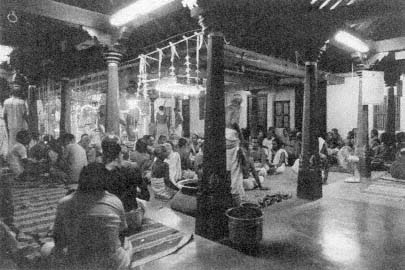

Plate 21.

Shastiaptapurti kalyanam (sixtieth birthday celebration): Priests performing

ceremonies in central courtyard with guests in surrounding corridor.

Photo by Peter Nabokov.

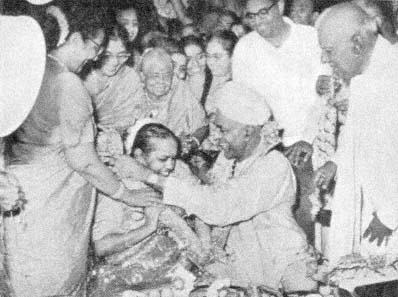

Plate 22.

Shastiaptapurti kalyanam: The second "wedding" of Raja Sir Muthia

and his wife. Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 23.

Shastiaptapurti kalyanam: Male guests at "wedding" meal. Photo by

Peter Nabokov.