Apocalyptic Tradition at the Time of the Ezkioga Visions

The Last Judgment is a notion Catholics reaffirm in every mass: "I believe that Jesus Christ rose up to Heaven and is seated on the right hand of God the Father Almighty. I believe that from there he will come to judge the living and the dead." The catechism in use in the diocese of Vitoria provided a reason for the Last Judgement and distinguished it from the judgment of individuals

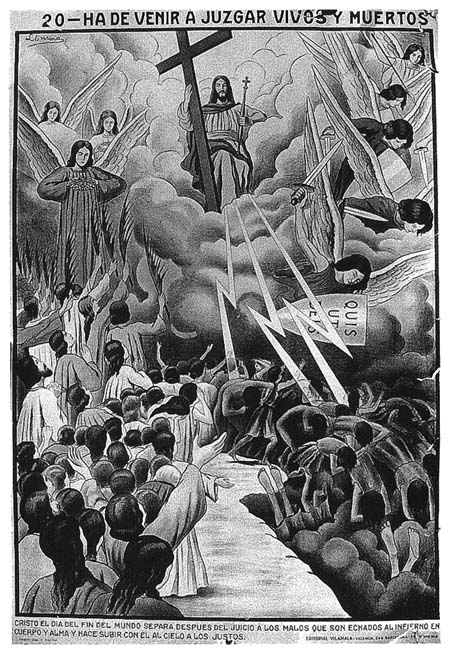

"He will come to judge the living and the dead." Catechism poster by

Ramón Llimona, Barcelona, 1919. Courtesy parish of Taganana, Tenerife

after death, but it provided no specifics about when the Last Judgment would occur.

143.

Q. When will Jesus Christ come to judge the living and the dead?

A. Jesus Christ will come to judge the living and the dead at the end of the world.

144.

Q. What is the trial called in which Jesus Christ will judge all men at the end of the world?

A. The trial in which Jesus Christ will judge all men at the end of the world is called the universal judgment.

145.

Q. Will there be, then, more than one judgment?

A. Yes, there will be two judgments: one individual, right after the death of every person, and another universal, at the end of the world.

146.

Q. Why will there be a universal judgment?

A. The universal judgment will be to confound the bad and glorify the good, and show the triumph of the justice of God.[2]Múgica, Catecismo, 22.

This vagueness about the timing of the Last Judgment, the sensible result of centuries of mistaken predictions, has been difficult for some Christians to accept. They have tried to reconcile the many references in the Old and New Testaments and assemble them into a program for the future. Additional prophecies by "holy" persons have complicated an already confusing task. Prophetic literature proliferated especially in periods of religious trial, political or social revolt, and military defeat.[3]

Carbonero, "Prólogo," vi; Thurston, The War, 189.

In the wake of the French Revolution, prophets in nineteenth-century France like Mlle. Le Normand, the farmer Thomas Martin, Eugène Vintras, the children of La Salette, and Joseph Antoine Bouillan revived medieval traditions of the coming of a great monarch, thus comforting ultraroyalists looking for a return to the Old Regime and ultra-Catholics looking to the pope as a temporal power. Visionaries from other countries like the Lithuanian Pole Andrzej Towianski, the Italian David Lazzaretti, and the Spaniard José Domingo Corbató found comfort and inspiration in France.[4]

For late medieval and Early Modern prophets: Niccoli, Prophecy; Frijhoff, "Prophétie et société"; for nineteeth-century prophets: Caffiero, La Nuova era; Griffiths, Reactionary Revolution; Kselman, Miracles and Prophecies; Boutry and Nassif, Martin l'Archange; Lazzareschi, David Lazzaretti; Peterkiewicz, Third Adam, 63-66. Thurston, The War, lists prophetic literature from the 1870s.

The Voix prophétiques of the Abbé J.-M. Curicque had great success in France because of the fall of the Papal States and the French loss of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. The prophecies in this book were the main source for similar collections in Spanish by Corbató, in 1904 and the Chilean priest Julio Echeverría in 1932. Padre Burguera used Corbató, and Antonio Amundarain used Echevarría. The Corbató work in turn was the basis for Enrique López Galuá's in 1939, which in turn provided material for the work of Benjamín Martín Sánchez in 1968.[5]

Corbató, Apología; Echeverría Larrain, Predicciones; López Galuá, Futura grandeza; and Martín Sánchez, Los Últimos Tiempos. Curicque himself used the collection Recueil des prophéties les plus authentiques. A Spanish translation of Voix prophétiques with some additional material was published in 1874. For Spanish background on Antichrist see Caro Baroja, Formas complejas, 247-265. Raymond de Rigné used Elie Daniel, Serait-ce vraiment la fin des temps? (Paris: Téqui); for Rigné's other reading see R 104-108, and for that of Burguera see B 469-471.

One strain of this prophetic tradition, the reign of the Sacred Heart, was particularly respectable in twentieth-century Spain, perhaps because the Jesuits

promoted it. Its origin lay in "promises" the French nun Marguerite-Marie Alacoque had received in vision between 1672 and 1675, especially: "This Sacred Heart will reign in spite of Satan and of all those whom he convokes to oppose it." The "social reign of the Sacred Heart of Jesus" became a central theme of the pilgrimages to Paray-le-Monial in Burgundy in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The idea of this reign spread through international Eucharistic congresses. Padre Bernardo de Hoyos in 1733 had connected this expected reign more specifically to Spain. At the time of the visions of the Christ of Limpias in 1919, commentators inside and outside the country speculated that the Christ's movements were a sign that the reign was approaching. In the twenties and thirties the notion gave a sharp focus to the phrase in the Our Father "thy kingdom come." Amado de Cristo Burguera was counting on the arrival of the reign of the Sacred heart; he had received the idea for his great work at Alacoque's vision site at Paray-le-Monial. And the reign of the Sacred Heart Played a central role in the false prophecies of María Rafols. In the prophecy that María Naya discovered in January 1932 the Sacred Heart himself told Rafols that the document would be found "when the hour of my Reign in Spain approaches." So it is not surprising that Christ's reign—just what that meant was unclear—became part of the Ezkioga visions and the scenarios the seers described for the end of time.[6]

Alacoque was beatified in 1864. Pius XI considered the feast of the Sacred Heart a bulwark against liberalism and made it universal in 1856. On the promises see Ladame, Paray-le-Monial, 237-266. On the reign of the Sacred Heart see Cinquin, "Paray-le-Monial," 269-273; and Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 109-116. For prophecy, Zurbitu, Escritos, 56.

The end of the world was of particular interest for many Integrists or Carlists. La Semana Católica of Madrid recalled that the energetic archbishop and founder of the Claretian order Antonio María Claret had said the world would end around 1930. The magazine also cited an alleged apparition of Pius X in which he said there would be calamities within ten years. In 1923 a canon of Jaéen, who agreed with Claret, thought the growing ascendancy of the devil and the apostasy of nations, including wise men, politicians, writers, spiritists, and "twenty million socialists and communists in international collusion," were signs the end was near. He speculated on the different phases that would take place after the coming of Christ—his reign, the millennium, the Last Judgment. And he hoped the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera would delay the apocalyptic catastrophe so that the rest of the world felt its effects first. Writing in January 1931 about an impending worldwide cataclysm, Antonio Amundarain saw the Aliadas as victims who offered themselves to God to avoid the end.[7]

Predictions in Sarrablo, "Verdades," and La Semana Católica, 4 August 1923, pp. 142-143, and 8 March 1924, p. 306; Morrondo (the canon of Jaen), Proximidad and Jesús no viene; citation from Morrondo's article in La Semana Católica, 8 September 1923, pp. 302-303; on Primo de Rivera see La Semana Católica, 29 March 1924, pp. 402-404. After more on the end of the world in July and August 1924, readers of the magazine were told to disregard the predictions on 6 September 1924, p. 299. Burguera read Morrondo (De Dios a la Creación, 83). Amundarain, LIS, 1931, pp. 9-10.

Short-term prophecies came in tracts, broadsides, and leaflets, such as the prophecies related to World War I and the Spanish military setbacks in Morocco. This literature—the Rafols prophecies are prime examples—received a fresh impetus in 1931 with the burning of convents and the separation of church and state. Apparitions of the Virgin, however, provided a more direct way to know the future. The Integrist newspaper El Siglo Futuro thought that the Virgin appeared at Ezkioga as at La Salette to warn of a civil war that was a chastisement from God: "Here too the Most Holy Virgin prophesied catastrophes, here too,

by means of her faithful servants, male and female, she preached penance to the Spaniards."[8]

On World War I prophecies see Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 185 n. 102. La Semana Católica, 26 July 1924, p. 111, cites a pamphlet by Gil Zarco, Los Milagros y profecías en el momento presente, about the seer/prophet/healer Bernardo Carboneras, who operated in Valencia and Cuenca, and his success in finding soldiers lost in Morocco, El Siglo Futuro, Madrid, 16 January 1934.

The supposed secrets of Mélanie of La Salette, first published in 1871, circulated widely in Spain. The Ezkioga apocalyptic visions eventually converged on this text. The most relevant passage is as follows:

Paris will be burned and Marseilles swallowed by the sea. Many great cities will be leveled and swallowed by earthquakes. It will seem that all is lost, you will see only murders and hear only the sounds of weapons and blasphemies. The just will suffer greatly; their prayers, their penance, and their tears will rise to heaven, and all the people of God will ask for pardon and pity and will ask for my aid and intercession.

Then Jesus Christ, through a miracle of his justice and his great mercy for the just, will order his angels that all my enemies be put to death. Suddenly, the persecutors of the church of Jesus Christ and all the men given over to sin will perish, and the Earth will become like a desert.

Then peace will be made, the reconciliation of God with men. Jesus Christ will be served, adored, and glorified. Charity will flower everywhere. The new kings will be the right arm of the Holy Church, which will be strong, humble, pious, poor, zealous, and imitate the virtues of Jesus Christ. The Gospel will be preached everywhere, and men will make great advances in faith because there will be unity among the workers of Jesus Christ and men will live in the fear of God.[9]

Texts in: Corbato; Curicque, Voces proféticas, 82; R 105; López Galuá, Futura grandeza, 70; and Martín Sánchez, Los Últimos Tiempos, 42-43. For critical issues regarding Mélanie's secret, see Zimdars-Swartz, Encountering Mary, 183.

These macrothemes filtered into the Ezkioga messages in the following sequence: (1) a great miracle; (2) a chastisement, which seers predicted first as local, then as universal; (3) an ever more elaborate program for the end of times that subsumed both miracle and chastisement.