Critique of the Food-Supply Dictatorship

The rhetoric used by the Bolsheviks to present and justify the foodsupply dictatorship reflected their whole view of the revolution. The same can be said of the critique of the Bolshevik program put forth by the Left SRs and the Mensheviks, who constituted the loyal soviet opposition at this point and were still able to present their case in the Central Executive Committee. These two opposition parties were themselves deeply opposed in outlook, and it is probably true that each of them had more in common with the Bolsheviks than they had with each other. But their critique of the food-supply dictatorship had one point in common: they both lashed out at the Bolsheviks' primitivism and propensity to solve complex problems by means of crude force and heavy-handed centralization. The two parties had very different ideas about where the important complexities lay, and each defended the claims of their own specialists to be able to handle these complexities. The Left SR specialists were members of the SR-dominated village soviets, whom the Left SRs regarded as experts in peasant class relations, whereas the Menshevik specialists were economists and foodsupply experts like Groman.

The essence of the Left SR position was the defense of the independence of the village soviets, the latest incarnation of the village solidarity that the populist tradition had always celebrated. The Left SRs felt that the kulaks were an isolated and hated minority and hardly likely to dominate free soviets. The majority of the peasants—the "laboring peasantry"—genuinely supported worker-peasant sovereignty, and it was a mistake to stifle their initiative by imitating tsarist bureaucratism or, even worse, to antagonize them by sending out requisition squads. The proper course was rather to carry out energetically the laws on land equalization and to rely on the "state sense" of the local democratically elected authorities. Let policy be determined at the center, the Left SRs argued, but let it be carried out in a decentralized manner.

What particularly pained the Left SRs was the Bolsheviks' irresponsible use of the SRs' two-part division of the peasantry. The SRs used the model to emphasize the unity of the majority of the peasantry; the Bolsheviks temporarily adopted it to stress the sharpness of the split within the peasantry (without the fuzziness created by the assumption of a large swing group in the middle) and thus to stress the necessity and expediency of resorting to splitting tactics and the use of force. But the Bolsheviks were hardly likely to apply force constructively, said the Left SRs, as long as they relied on such a vague and inaccurate understanding of the kulak as they displayed in the Central Executive Committee debates. Obviously not everyone with a marketable surplus was a kulak: only those totally ignorant of the village would so believe. Who was or was not a kulak was a question to be decided by knowledgeable experts, namely, the local soviets, who would decide "on the basis of a whole range of complicated and delicate considerations" of which only locals could be aware. But the Bolsheviks proposed to send detachments composed of the dregs of the working class, people whose hunger had overcome their sense of honor to such an extent that they were ready to attack the laboring population of the villages.[48] Of course force should be applied against the real kulaks, acknowledged the Left SRs, but to do that in a crude and ignorant way would surely lead to a general throat cutting and discredit the revolutionary authority.

The Left SRs asserted that if the Bolsheviks were absolutely determined to split the village along class lines, they should do it in a respectable way and divide the classes by means of production (land and equipment), not by means of consumption (grain surpluses). As a result of Bolshevik bungling and paranoia about kulak influence on the peasantry, the exact opposite of

[48] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 9 May 1918, 254-56 (Karelin).

what they intended would be achieved: the otherwise isolated kulaks would get a new lease on life as the village formed a united front against what would be perceived as a marauding band from the cities. As the Left SR B. V. Kamkov summed it up: "Out of all the ways to fight with the famine, [the Bolshevik food-supply dictatorship] is the least likely to achieve its aim. . . . You do not know the village and you do not know how to fight the kulaks and as a result you are supporting them."[49]

Beyond these tactical arguments, the Left SRs had a deeper objection to what they regarded as Bolshevik dogmatism. They felt that the Bolshevik class-war rhetoric betrayed a willingness to shove alien urban schemes down the throats of the villagers. The Left SR V. A. Karelin interpreted the Bolshevik slogan class war in the villages to mean "up against the wall, I'm applying the principle of class struggle to you."[50] And Spiridonova parodied Bolshevik determination to clothe their emergency measures in revolutionary rhetoric: "Comrade Bolshevik-peasants, take these thick books of the Marxists and you will understand why punitive expeditions are being sent out." At bottom was the vindication of the peasants' right to full political and cultural equality with the urban workers: "We declare that the peasantry also has an independent way of life and a right to a historical future."[51]

The Mensheviks did not share the Left SR enthusiasm for the local soviets and wondered why the Left SRs could not see the necessity of preserving the "ties that united the different parts of Russia into one integral organism."[52] Although accepting the Bolshevik goal of centralization and organization, the Mensheviks felt that the Bolsheviks were entirely incapable of achieving it because of their political methods. The heart of the Menshevik critique was the assertion that Bolshevik exclusiveness and demagoguery on the political level made effective economic organization impossible. The Bolsheviks rejected a broad socialist coalition, harassed the opposition press, restricted the electorate, and in general resorted to "civil-war methods." At the same time they proclaimed "all sovereignty to the soviets," a policy that had the predictable result of destroying the ability of the center to carry out effective policy. And in their desperate attempt to save the situation, the Bolsheviks continued to refuse to share power; hence recentralization led to heavy-handed and ineffective bureaucratism.

[49] Fifth Congress of Soviets, 5 July 1918, 74-77.

[50] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 9 May 1918, 262.

[51] Fifth Congress of Soviets, 5 July 1918, 58-59. "Independent way of life" is a desperate paraphrase of zhizneustoichivo .

[52] Central Executive Committee, 9 May 1918, 256-58 (Dan).

Certainly localism was a problem, but the Bolshevik diagnosis of that problem as stemming from kulak influence was simply mythology. Any democratically elected local government would show the same localist tendencies, said Iulii Martov, and there was only one weapon against them: "independent and free deliberation, and most important, the independent manifestation of public opinion." Unwilling to countenance this openness, the Bolsheviks overreacted to localism: "Without enlistment of the broad masses [that is, without universal suffrage], you will be tossed like a squirrel in a treadmill between ultra-anarchist ideas and a bureaucratism that sounds like a sour joke in the ear of the workers to whom you promised to give 'all sovereignty to the soviets.'"[53]

One political advantage of the Mensheviks was that their specialists in food supply and other economic areas were clearly a more prestigious group than the Bolsheviks could produce—indeed in 1917 the Bolsheviks had simply taken over the program of Groman and his followers. The Mensheviks tried to press their advantage by stressing the technical incompetence of the Bolsheviks: what good was centralization if the Bolsheviks did not have the bureaucratic wherewithal to make use of the opportunity? "Why your bureaucrats [chinovniki ] should be more skillful and intelligent than the old ones, we do not know: practice has shown that they are much more venal, more dishonorable, and more corrupt than the old bureaucrats." (The speaker here, Rafael Abramovich, was called to order at this point by Sverdlov.)[54]

The Bolshevik response was to extol the virtues of the "modest workers [rabotniki ]" who were "pushed forward [vydvinutye ] by the masses." Lenin admitted that "the workers begin to learn slowly and of course with mistakes—but it is one thing to spout phrases and another to see how gradually, month after month, the worker [rabochii ] grows into his role, starts to lose his timidity, and feels himself the ruler."[55] A remark made by N. Orlov about the first food-supply congress in January expresses the underlying clash of attitudes:

One of the authoritative food-supply officials [Groman?] attached to the group that walked out of the Congress announced in a session of the socialist group of employees of the old Ministry of Food Supply that members of the Congress

[53] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 27 May 1918, 328-30 (Martov).

[54] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 27 May 1918, 330-32. Abramovich's attack was even more embarrassing because he quoted an intra-Bolshevik party circular confirming his analysis.

[55] Shlikhter, Third Congress of Soviets, 15 January 1918, 71-72. Lenin, PSS , 36:515, 5 July 1918.

"were people who sincerely despised all knowledge and hated all bearers of knowledge." In that heated time, it was difficult to expect an objective appraisal from people, especially from those who had chosen the enviable part of "sincerely not understanding" any creative outburst and who were deeply contemptuous of people striving to realize their desires in reality.[56]

The Mensheviks felt that energetic ignorance was no substitute for competent experts responsive to informed public opinion. The Bolsheviks were returning to an illusion of tsarism when they relied on giving wide power to commissars—a sort of food-supply governor-general—and sending them out as troubleshooters, acting in defiance of economic laws and the need for careful coordination.[57] Given their reliance on these methods, the Bolsheviks were incapable of actually carrying out the grain monopoly. Although the Mensheviks were even more closely associated than the Bolsheviks with the monopoly and the need for extensive economic organization, they reluctantly concluded that a paper monopoly was worse than none at all: why prohibit the people from providing for themselves if the government is incapable of providing them with the food they need? The Mensheviks therefore advocated certain concessions in regard to prices and the right of independent purchase; the Bolsheviks seized on these and called the concessions a capitulation to the capitalists and the kulaks.

Just as Bolshevik political methods made economic recovery impossible, Bolshevik economic methods made further political degradation inevitable. In particular, the accelerating inflation provided an economic analogue to the disintegration of central authority. Semyon A. Falkner, one of Groman's group, argued that the inflation created an irresistible economic pressure to break the increasingly unrealistic prices fixed by the state and that this pressure realized itself in the sackmen:

True, the fixed price usually entails a personal responsibility for breaking it, established by penal sanction in the law. But the realization of these threats requires a powerful state organization that penetrates into all cells of the social organism, [It must be] powerful not only from the physical volume of forces and means at its disposal but from the psychological training and unbribability of its agents.

But it is in the epoch of revolution and the reconstruction of the state mechanism that these forces are weakened and the

[56] Orlov, Rabota , 38.

[57] Central Executive Committee, 9 May 1918, 256-58 (Dan).

threats merely hang in the air, only haphazardly striking down this or that chance victim.[58]

This description of a coercive apparatus that is both all-embracing and ineffective does seem to apply to the Cheka, which never succeeded in damming the pressures leading to a speculative black market.

A brief mention should be given to critiques advanced by the Right SRs and the Kadets. Only one Right SR put in an appearance during the Central Executive Committee debates on the food-supply dictatorship. This speaker, Disler, boldly accused the Bolsheviks of creating the famine—through the inflation that they had intensified in a desperate attempt to stay in power, through the Brest-Litovsk peace, which deprived Russia of grain areas, through the civil war provoked by Bolshevik methods (the Czech troops in Siberia had just revolted), and finally through the proposed foodsupply dictatorship: "These armed detachments will be able to alleviate your thirst for blood, but not the hunger of the population." At this point, as can well be imagined, Disler was deprived of the floor.[59]

I take the Kadet critique from a pamphlet written in England in early 1919 by the emigre[émigré] Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams. She viewed the Provisional Government's original grain monopoly as a painful wartime necessity, one that later turned out to be a mistake since it was clearly beyond the capacity of the government machinery. The Bolsheviks retained it even after the peace treaty for ideological reasons, although they rejected most other Provisional Government reforms. Tyrkova-Williams also attacked the harassment of the sackmen train passengers by the lawless blockade detachments. (None of the socialist parties raised this point in the spring Central Executive Committee debates, although it had been going on since January.) Similarly, Tyrkova-Williams did not condemn the Committees of the Poor because they distorted the class struggle: rejecting the idea of class struggle altogether, she maintained that the Committees of the Poor were making orderly life impossible by introducing violence into village affairs and giving an opportunity to the village rabble to settle accounts: "Vio-

[58] Trudy pervogo s"ezda , 31 May 1918, 395-404. To combat inflation and the incoherent system of fixed prices, the Gromanites brought up their old program of an economic regulatory council (to be called the Price Center) on which the various economic interests would be represented so that an "equilibrium" would be established.

[59] Central Executive Committee, 4 June 1918, 386-87. This was a joint meeting with the Moscow Soviet and worker groups. The next speaker was Trotsky, who erupted with rage at the implied charge that he was responsible for the Czech uprising; in a speech later that week he called for the removal of the Right SRs from the Moscow Soviet. According to Osipova, the SRs were instigators of peasant revolts. Osipova, Klassovaia bor'ba , 317ff.

lence was everywhere rampant, there was no one to complain to, and in any case complaint was useless. When utter lawlessness reigns, people do not complain but fight over their differences." In sum, "The commissaries themselves are powerless amid the anarchy they have created."[60]

How should we evaluate the critique advanced by the parties of the soviet opposition, the Left SRs and the Mensheviks? It cannot be doubted that many of their criticisms of the Bolshevik food-supply dictatorship were well aimed and that the Bolsheviks were forced, in practice if not in words, to recognize the accuracy of their predictions. The "class struggle in the village" did turn into a "throat cutting"; the worker detachments did disintegrate into drunken bands; bureaucratic red tape did damage commodity exchange with the village. But the positive alternatives put forth by the opposition parties were also weak, especially those of the Left SRs, who wanted to rely on independent local soviets and saw a complete solution only in a revolutionary war against Germany to regain the grain-rich regions. The Menshevik contention that only extensive economic regulation in the style of Groman could solve the problem may have been correct, but it was an irrelevant counsel of perfection under the circumstances. The Mensheviks had begun to understand this flaw and were advocating a retreat from attempts to enforce the grain monopoly in its full rigor. The real question is whether Menshevik demands for a government of socialist unity and for unfettered political freedom were compatible with the imperative of imposing order.

Impractical as the positive suggestions of the Left SRs and the Mensheviks may have been, they were at least couched in language that corresponded to the actual content of the proposed programs. The same cannot be said of the Bolsheviks: the rhetorical dissonance between the class-war rhetoric and the actual program of disciplined centralization was vast and difficult to bridge. Having staked their political reputation on "all sovereignty to the soviets," the Bolsheviks could not say out loud that as predicted, it had all been a terrible mistake and sovereignty would now have to be taken away from the soviets. Their rhetorical cover-up was something more than the usual political hypocrisy and euphemism, and it had important consequences. One has already been mentioned: the opposition parties had to be excluded from the soviets so that they would not "sow panic," that is, so they could not point out that the Bolsheviks' new rhetorical clothing was threadbare. The Bolsheviks were caught in a bind:

[60] Tyrkova-Williams, Why Soviet Russia Is Starving , 11-13, 5-8. The Mensheviks also saw the village soviets as one armed group lording it over the rest. Tyrkova-Williams is somewhat coy about Kadet responsibility for the introduction of the grain monopoly in the first place.

their effort to overcome the crisis of authority depended on public loyalty to a political formula that they themselves no longer fully believed in.

The debates over the food-supply dictatorship in the spring of 1918 have special historical resonance because they mark the point where three visions of the Russian revolution finally parted ways. The intensity with which the Russian intelligentsia believed in the idea of revolution had come in large part from the clash and interplay of these partially conflicting visions of the tasks of the revolution. The spring of 1918 was the end of the road for two of these visions. The revolutionary vision defended by the Left SRs contended that the Russian peasant had something of positive value to contribute to the Russian future. The vision of the February revolution defended by the Mensheviks asserted that the Western model of constitutionalist civilization—not just the technological and organizational dynamism admired by the Bolsheviks—contained many things that Russia must adopt if it were to reach greatness. These visions could not survive the pitiless environment of the time of troubles. The food-supply crisis of 1918 revealed the impoverishment not only of the Russian people but also of the Russian revolution.

1. Bolshevik propaganda poster, 1920: "The workers and the peasants are

finishing off the Polish gentry and the barons, but the workers on the home

front also have not forgotten about help to the peasant economy. Long live

the union of the workers and peasants!" At the bottom: "Week of the

Peasant." (From N. I. Baburina, ed., The Soviet Political Poster, 1917-

1980, from the USSR Lenin Library Collection [Harmondsworth:

Penguin, 1985], plate 18.)

2. Bolshevik propaganda poster, 1920: "Without a saw, axe, or nails you

cannot build a home. These tools are made by the worker, and he has to

be fed." (From N. I. Baburina, ed., The Soviet Political Poster, 1917-

1980, from the USSR Lenin Library Collection [Harmondsworth:

Penguin, 1985], plate 21.)

3. "Milk was very hard to get, and the women and children waited sometimes

overnight for a small supply." (From Orrin Sage Wightman, The Diary of an

American Physician in the Russian Revolution, 1917 [Brooklyn: Brooklyn

Daily Eagle, 1928].)

4. "Tobacco, like bread and other necessities, was secured by ticket. This

offered a profitable field of speculation for the soldiers." (From Orrin Sage

Wightman, The Diary of an American Physician in the Russian Revolution,

1917 [Brooklyn: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1928].)

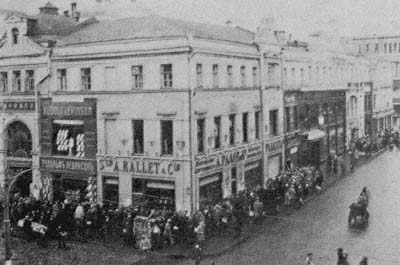

5. "At Nijni-Novgorod they had established small markets where you

could buy almost anything the other man did not want." (From Orrin

Sage Wightman, The Diary of an American Physician in the Russian

Revolution, 1917 [Brooklyn: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1928].)

6. "At every station the peasants would meet the passing trains with food and

milk, often cooked fowl and chicken wrapped in steaming hot towels." (From

Orrin Sage Wightman, The Diary of an American Physician in the Russian

Revolution, 1917 [Brooklyn: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1928].)