The Problem of Formulas and Their Interpretation

In a little-known passage, Albert Ladenburg, a student of Bunsen, Carius, Kekulé, and Wurtz, painted an intriguing picture of the Frankfurt Naturforscherversammlung of 1868. Butlerov had come to Germany for a third time, but Kekulé and several other Germans had felt aggrieved by Butlerov's critiques and were no longer very friendly. On a walk to a restaurant for lunch, Kekulé and Butlerov got into an angry argument, so when they arrived, some of the younger members of the group made sure to sit between the disputants. Later at one of the sessions, Kekulé and Erlenmeyer contested long and earnestly over questions of formulation. Ladenburg sat there silently, thinking that they were disputing unessential matters and had little disagreement in

substance. He said that he was able to persuade both men of this in private conversation afterward.[73]

Such disputes were common in the 1850s and 1860s. Kekulé had personally contributed to some of the confusion, for in 1857-1858, he had formulated a substantially new theory (atomicity of the elements, or structure theory) from the socially safe haven of type theory, using type-theoretical language and formulas. This conventional (Gerhardtian) garb later led some colleagues, notably Erlenmeyer and Butlerov, to view Kekulé incorrectly as having come only halfway at first.[74]

In 1864 Kekulé attempted to straighten out what he regarded as misinterpretations of his formulas. Rational formulas are ordinarily written as reaction formulas, that is, incompletely resolved formulas designed to illustrate specific reactions, functions, or familial relationships. This is normally the most useful and appropriate way to write formulas, Kekulé argued, since excessive or unnecessary detail can degrade clarity of presentation. However, there are certain situations when one wishes to specify the bonding relationships of every atom in the molecule, and this is possible if the compound has been sufficiently investigated. One can write such a completely resolved formula using either type-theoretical or graphical notation (the latter being, for Kekulé, his curious sausage-shaped structures); graphical formulas are clearer but also more cumbersome. According to Kekulé, when one writes a completely resolved formula, whether in terms of types or sausages,

compound radicals completely vanish. . . . Thus, one goes back to the elements themselves which compose the compound. But these are the very considerations that led to the view that carbon is a tetratomic element, and that carbon atoms have the property of bonding to themselves.[75]

It would appear that Kekulé was trying here not only to defend himself from Butlerov's critiques but also to explain Wurtz' position with regard to Kolbe, for Kolbe had scorned Wurtz' view that multiple rational formulas are possible for one and the same compound. Wurtz found himself making a similar defense against his Russian friend Butlerov. After Butlerov's "Erklärungsweisen" appeared, Wurtz published it in his Répertoire de chimie pure and sent him a letter complimenting him on the work:

I find expressed there ideas which I share myself; among others, that the idea of atomicity of elements is based on Gerhardt's types and gives them their true sense. . . . But I would regret it if you were to renounce type notation before being able to replace it with a more advantageous

one. Are you not struck by the simplicity of type formulas? . . . When bodies of complex composition are involved, these [structural] formulas are necessarily complicated, and in such cases indiscriminate use could hurt the clarity of the exposition. . . . Aside from these small reservations I am with you . . .[76]

Butlerov responded,

I am very happy to know that you share my thoughts, and I must add at the same time that what I said about the signification of Gerhardt's types is of course your idea, an idea that you have long been expressing in your publications. I believe that those typical formulas that suffice for the majority of relations of bodies do nothing more than express their chemical structure, or at least the most salient part of that structure.[77]

Butlerov was writing a new textbook of organic chemistry just at this time, the first fascicle appearing in the course of the summer of 1864. Since (as Beilstein put it in a letter to Baeyer) the book was based on German theories, namely on a "Kolbe-Kekulé foundation," Butlerov sought and eventually found a publisher for a German edition.[78] Here he repeated what he had said in his 1863 article, acknowledging that Kekulé was the author of structure theory but averring that his partial allegiance to type theory had led him to a number of inconsistencies. It was these inconsistencies and gaps that he had tried to call attention to and remedy in 1861. Still, Kekulé "recognized the principle of chemical structure more completely and applied it more generally" than Kolbe, who nonetheless deserved major credit (in Butlerov's opinion) for developing the theory. However, it had been Erlenmeyer, Butlerov said, who had been the most consistent and definite in recent years.[79]

This was not Beilstein's view. He wrote Butlerov about this time,

I also spoke during this vacation with Erlenmeyer about this point [atomicity of elements]. I told him that his papers often caused me a great deal of trouble, because each time I had to think myself into his theories, which cost a lot of time. The explanation for this is simple. These days there is no single orthodoxy or type theory, each chemist has his own beliefs & acts accordingly. Everyone is therefore used to thinking only in his own fashion & finds it difficult, i.e., is unaccustomed, to think in another fashion. For instance, Kolbe believes his formulas to be the simplest possible ones & once told Erlenmeyer that he has never been able to properly understand Gerhardt's theory.[80]

Erlenmeyer, for one, professed to have no trouble understanding other chemists' formulas. He wrote Butlerov,

I think we are the only two chemists in the world who understand each other and everyone else. Besides us, I know of no one else who understands us, and none who understands everyone else, as we do. Most typists understand Kolbe not at all, Kolbe understands the typists not at all, Kekulé doesn't understand himself, Kolbe, or us. Wurtz is in the same position. Heintz understands Wislicenus and Wislicenus understands Heintz, but no one else understands anyone else. Heintz thinks he understands you, but he too misunderstands you. Who's left?[81]

Erlenmeyer's viewpoint seems to have been fairly common among his peers. Each thought he understood the various formula styles quite well, thank you; it was only the others who were guilty of misunderstanding. Beilstein's comment cited above complains not about the impossibility but merely the labor of formula translation; Ladenburg averred that he succeeded in serving as interpreter between Erlenmeyer and Kekulé in 1868 and that their disagreement had been insubstantial.

There always were, and still are, pitfalls in understanding caused solely by a lack of complete comprehension of the notation, formula, or language used. Despite Erlenmeyer's sarcasm, however, most of the misunderstandings in organic chemistry of the 1860s were relatively minor or short lived, such as those described between Kekulé, Erlenmeyer, Butlerov, and Wurtz. There is little basis for the thesis that the primary cause of chemical controversy at this time was due to competing formula styles. Priority for structure theory was a lively subject, to be sure, in part due to slippery semantics. But when the discourse concerned specific reactions and specific substances, competitors generally managed to understand each other pretty well. Moreover, by the end of the 1860s, graphical structural notation had largely supplanted the diverse type notations, and there was thereafter little cause for confusion among the majority of organic chemists.

The one significant exception to this generalization was Kolbe, who sometimes found it difficult to follow the details of structure-theoretical arguments and whose own idiosyncratic formulas were sometimes misinterpreted, especially during the 1850s when his notation kept shifting. This problem is explored in greater detail in the first section of chapter 13. But even here the difficulties can be exaggerated. There were some substantive differences between Kolbe and the structuralists. These distinctions were understood by both Kolbe and his rivals, and it was usually on these that they rightly focused. This was particularly the case after he finally adopted atomic weights in 1868.

Kolbe's birthplace and home from 1818 to 1826, the Elliehäuser

parsonage. Photograph taken in June 1992 by the author.

Lutheran church in Stöckheim, Kolbe's home from 1826

to 1840. Photograph taken in June 1992 by the author.

Lutheran church in Lutterhausen, Kolbe's parents' home from

1840 to 1870. Photograph taken in June 1992 by the author.

Hermann Kolbe, ca. 1860, pen-and-ink drawing by F. Justi (1880), from a photograph.

Courtesy of the Erbengemeinschaft Justi, Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

Deutsches Haus, Marburg—Kolbe's Institute, 1851-1865.

Photograph taken in June 1992 by the author.

Chemical Institute of the University of Leipzig, ca. 1908. From the

Festschrift zur Feier des 500 jährigen Bestehens der

Universität Leipzig (Leipzig: Hirzel, 1909, page 72).

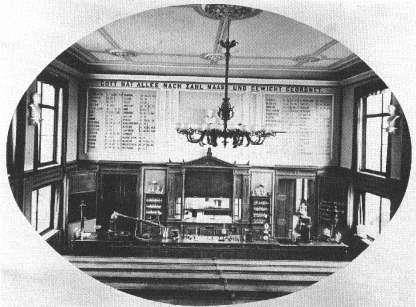

Kolbe's lecture theater, Leipzig, 1872.

Courtesy of the Deutsches Museum, Munich.

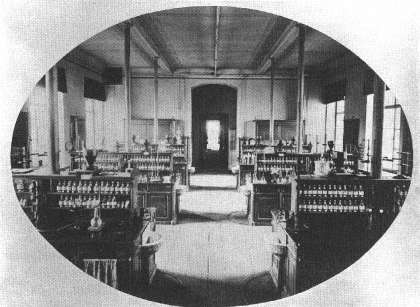

Kolbe's teaching laboratory, Leipzig, 1872.

Courtesy of the Deutsches Museum, Munich.

Villa Adolpha, Dresden, 1874: site of first production of

salicylic acid. Courtesy of the Deutsches Museum, Munich.

Hermann Kolbe, ca. 1880. Photograph

from the author's collection.

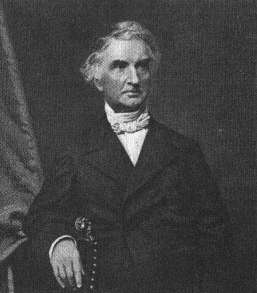

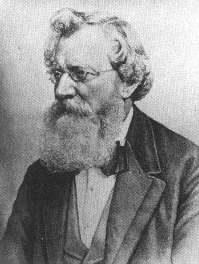

Justus Liebig. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

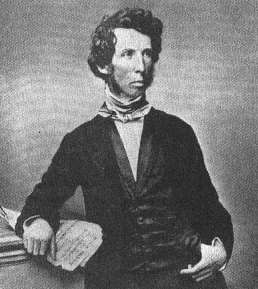

Friedrich Wöhler. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Robert Bunsen. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Edward Frankland. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

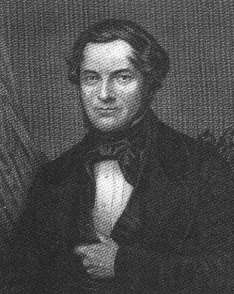

August Kekulé. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

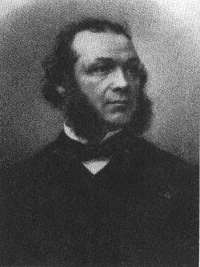

August Wilhelm Hofmann. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

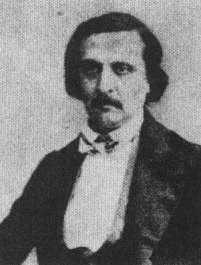

Adolphe Wurtz. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Charles Gerhardt. Courtesy of The Edgar Fahs Smith

Collection, Special Collections Department, Van Pelt-

Dietrich Library Center, University of Pennsylvania.