9—

The Gold Rush and the Beginnings of California Industry

David J. St. Clair

The California Economy on the Eve of the Gold Rush

In 1845, California was a sparsely populated, remote, colonial outpost. Not counting the 100,000 unassimilated Indians who continued to live independently, California's population of 17,900 (10,000 assimilated Indians, 7,000 Spanish/Mexican descendants, 700 Americans, and 200 Europeans) was largely clustered along the coast from San Diego to Sonoma.[1] Monterey and Los Angeles were its cultural centers, while San Francisco, then known as Yerba Buena, was only a small hamlet of a few hundred people.

On the eve of the Gold Rush, the missions had been secularized and decaying for more than a decade. Most economic activity was organized around the ranchos, large cattle ranches that produced hides and tallow, the two leading commodities that connected California with the outside world. Along with soap making, the processing of hides and tallow were the only activities that might be described as industrial. The hides, minimally dressed and processed, were sold to foreign merchants. Cattle brought from $4 to $6 per head, reflecting the value of their hides and fat.[2] Ample supply and very limited demand made the meat almost worthless. The export of hides, tallow, and small quantifies of wheat, soap, lumber, and gold financed imports. Imported products and local crafts provided Californians with a simple but comfortable life.

California's pre-gold-rush economy was certainly rudimentary. Some historians have gone further, arguing that it was stagnant. In their pioneering economic history, Robert Cleland and Osgood Hardy described California from 1769 to 1848 as "sparsely populated by an unambitious, pastoral people who were seemingly . . . indifferent to all material progress and . . . unmindful of the vast economic opportunities that surrounded them on every hand."[3] Although this stereotypical criticism

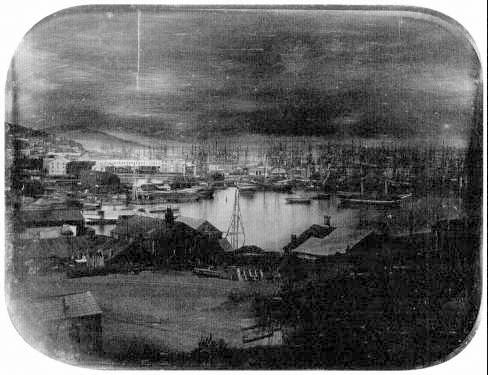

When the amateur artist William R. Hutton visited San Francisco in September 1847, it was a

rough-and-tumble community of adobes, shanties, and frame buildings scattered along Yerba

Buena Cove. But following the discovery of gold at Coloma in January, the village was

transformed into a vigorous cosmopolitan city. By late 1851 it had a population of some thirty

thousand, streets lined with solid brick edifices, and one of the busiest ports in the nation.

Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

is unwarranted, there is no doubt that the California economy was small and largely undeveloped.

The Gold Rush unleashed a torrent of change on this pastoral economy. Its first effect was to disrupt the economy. Workers, ranch hands, and shopkeepers rushed off to seek their fortunes in the gold fields. One San Francisco newspaper printed its last edition in 1848 with the following declaration:

The majority of our subscribers and many of our advertising patrons have closed their doors and places of business and left town . . . . We have also received information that very many of our subscribers in various parts of the country have left their usual places of abode, and gone to the gold region . . . . The whole country from San Francisco to Los Angeles and from the sea to the Sierra Nevada resounds with the sordid cry of "gold! GOLD!! GOLD!!! " while the field is left half planted, the house half built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes.[4]

Although we have no statistics, production must have suffered. Fortunately, the disruption was only temporary, as many who rushed off in search of fortune returned after finding only hard work and little gold. However, the lure of gold kept labor at a premium, at least at first, and high wages were a common complaint. John Hittell, a contemporary commentator, argued that high wages delayed industrial development in California.[5]

Those who returned from the gold fields found a very different economy. Overnight, gold transformed California's lethargic business world into a surging boom. People rushed in and gold poured out into the world economy, as California became the center of world production of precious metals. The surge of population brought an unprecedented demand that turned the traditional economy upside down. The scrawny Spanish-stock cattle that earlier had sold for $5 per head now brought $300 to $500 per head to feed hungry miners with gold in their pockets.[6]

By the beginning of 1849, California's population had reached 26,000.[7] By the summer, it jumped to 50,000. San Francisco became the world's fastest growing city, its population exploding from 812 in 1848 to 25,000 in 1850. The official census of 1850 recorded 92,597 people living in the state, while unofficial estimates put the correct figure at 115,000. California's population rose to 380,000 in 1860, 560,000 in 1870, and 865,000 in 1880.[8] During its first century as a state, California's population doubled roughly every twenty-five years.

Mining surged, and California agriculture was soon booming as well. Herds of cattle and sheep driven to California augmented local supplies. Wheat output increased dramatically. By 1860, California was producing five times as much wheat as all other western states and territories combined. California wheat exports poured into world markets. Vineyards were also planted and a wine industry took root within a couple of years of James Marshall's discovery. The impact of gold on California agriculture has generally been appreciated, but what about California industry? Was it similarly influenced, or were money, labor, and energy channeled instead only into gold mining and agriculture?

Historiography of California Industry During the Gold Rush

Historians have offered divergent views of California industry during the Gold Rush. All acknowledge that important first steps were taken during these years, but many argue that industrial development lagged until the last decade of the nineteenth century, or even later. John Hittell began his 1862 survey of California industry, The Resources of California , with a list of reasons why the state's industry could not compete with eastern or European producers.[9] High wages, high interest rates, and a lack of coal, iron, and cotton supplies, he argued, were barriers that producers could not

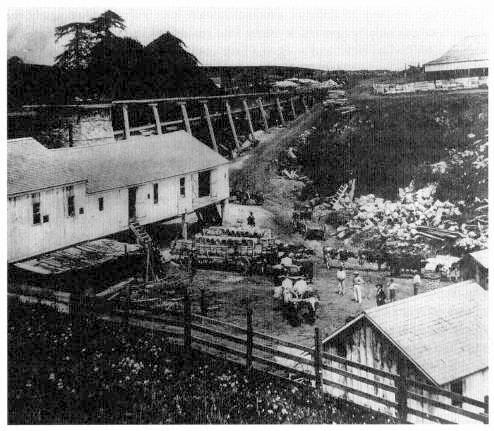

A team of oxen hauls a wagon loaded with barrels of lime from the Davis & Cowell kilns at

Santa Cruz, about 1865. The rapid rise of urban California that began with the Gold Rush

created a huge demand for lime, an essential element in the making of mortar, plaster, and

cement. Lime production emerged as a leading industry of Santa Cruz at midcentury, and by

1868 the company was shipping a thousand barrels a week, helping to make Henry Cowell

one of the richest men in the county. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

hurdle. In the 1879 edition of the same book, Hittell added the following to his list of obstacles retarding industry: a lack of water power near cities, high transportation costs, expensive water in large towns, expensive land prices near deep-water ports, and insecure land titles.[10] According to Hittell, these obstacles prevented California from exporting any manufactures, kept industry only producing crude industrial products, and limited the state's exports to unfinished or semi-finished resources.[11]

To be sure, Hittell's 1879 edition chronicled more industrial activity in the state by that date, but he still described California products as being "mostly of a crude class.[12] He argued that California producers were able to survive because high transportation costs made outside goods less competitive in the California market.

Hittell concluded that "California agriculture and mining industries had reached advanced development in some branches, while our manufactures are backward.[13] Symptomatic of the state's retardation was its failure to embrace steam power, relying instead on its human muscle, to its "great disadvantage."[14]

Hittell's views became less pessimistic in his later work, but historians have echoed his negative themes down to the present. One author of a survey history of the state, Andrew Rolle, observed that large-scale manufacturing in California appeared "tardily on the scene" due to unstable conditions in California and its distance from large eastern cities.[15] Earl Pomeroy concludes that during the Gold Rush "Western industry lagged or even deteriorated while Western agriculture advanced in technique and prospered."[16] According to Pomeroy, the problem was that "Western manufacturers could not compete with the mass production of the older states except in goods that had to be custom-made or cost too much to ship."[17] In addition, San Francisco businessmen "were content to put their capital into the finished goods that came from the East."[18]

Richard Rice, William Bullough, and Richard Orsi note that in 1860 San Francisco ranked fifteenth among American cities in terms of population, but only fifty-first in terms of manufacturing "because conditions then discouraged heavy industry in the city and state."[19] Scarce coal and iron, prohibitive interest rates, and more lucrative prospects in mining, transportation, and land delayed industrialization until the 1860s and early 1870s. They argue that isolation brought on by the Civil War was a factor in stimulating industrial growth, but concede that the industrial demands of new mining techniques were more important.

Other writers argue that the Civil War had a greater impact on California industry. Cleland and Hardy credit disrupted trade with the East Coast with affording more protection for California's infant industries, including the manufacture of boots, shoes, clothing, chemicals and drugs, furniture, iron and steel, distilled liquor, soap, candles, and tobacco products.[20] Rolle argues that the Civil War not only provided infant industry protection to California firms, it also turned San Francisco into an export center for grain, flour, lumber, wool, mineral ores, quicksilver, and other products.[21] The implication in these accounts is that California industry was delayed until the war, an external event, forced California producers to develop their own resources. However, this stimulus was short-lived, making the industries that benefited from the war exceedingly vulnerable to the inevitable downturn that came with peace.

W. H. Hutchinson writes that while California lacked the coal and iron necessary for industrial expansion, the state "quickly established a basic heavy industry because she had to."[22] Cleland and Hardy repeat Hittell's discussion of the obstacles retarding California industrial growth, but nonetheless cite "a material advance" in California industry between 1850 and 1870, especially during the Civil War.[23] However, they argue that higher profits in mining and agriculture meant that little "serious at-

tention" was accorded California industry until 1900.[24] Likewise, Gerald Nash sees California's industrial stage as beginning in 1900.[25]

More positive views have been expressed by historian John Caughey and journalist Carey McWilliams. Caughey writes that California manufacturing developed "hand in hand" with mining, commerce, and agriculture in northern California.[26] McWilliams takes a different tack, arguing that California enjoyed the advantages of a head start in the competition for industry.[27] He sees California becoming a manufacturing center almost at the same time that it became a state.[28] According to McWilliams, California's early start in industrialization was a distinct departure from the norm, a great exception brought about by the novel conditions created by the Gold Rush and California's unique environment. The Gold Rush, he argues, created "certain underlying dynamics" that became the hallmark of the California economy.[29]

The Pace of Industrial Growth During the Gold Rush

Disparaging comments about the pace of California industry are not supported by U.S. census data.[30] Statistics for California first appear in the census of 1850. While this census is not entirely accurate (incomplete and lost data resulted in an under-count), it does offer insight and a starting point. Table 9.1 shows estimates of California manufacturing from the 185o through 1880 censuses.

The 1850 census ranked California manufacturing sixteenth (by value of output) among the thirty-six states and territories, a remarkable achievement in itself in the first year of statehood. By 1860, California manufacturing output had risen to seventh place, growing by 430.6 percent during the 1850s. This growth was far faster than that of any other state. Table 9.1 also shows the number of manufacturing establishments. Between 1860 and 1870, the number of establishments appears to drop precipitously along with a modest drop in the value of manufacturing output. This would be consistent with a revival of competition with the outside world following the war and the opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. However, there is a simpler explanation for the decline. Census data for both 1850 and 1860 include "mining" in the "manufacturing" category. Consequently, the Gold Rush of the early 1850s and the consolidation of mining in larger companies after those years appear in manufacturing statistics, thus distorting the data and begging the question at hand.

A better picture of industrial growth emerges when gold mining is removed from these figures. Table 9.2 shows California manufacturing with gold mining excluded. These figures reduce the size of the "manufacturing" sector reported in the census, but still show California with an industrial sector larger than nine other states and territories. More importantly, between 1850 and 1860, California's industrial sector

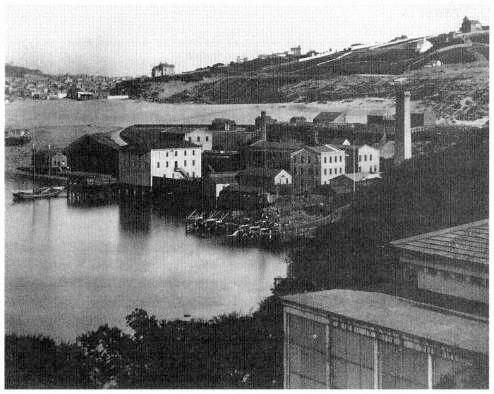

Two of the first iron works in California, the Pacific Iron Foundry, left , and the

Vulcan Foundry, right , stand silhouetted against the waters of Yerba Buena

Cove in a daguerreotype probably made in the winter of 1852-53 from the corner

of First and Howard streets, San Francisco. Although steamship repairs played

an important role in the early rise of foundries and machine shops, it was the

needs of mining that contributed most to the growth of iron working, which by the

conclusion of the Civil War was the leading manufacturing industry in the Golden

State. California Historical Society, FN-08432 .

(excluding gold mining) grew by 510.6 percent, faster than the 396.4 percent growth in gold mining. By 1860, California industry (again excluding gold mining) was ranked eighteenth, and was larger than the manufacturing sectors (with mining still included) of twenty-one other states and territories. In addition, when the distortion of gold mining is removed from manufacturing statistics, there is no decline in the number of establishments or output after 1860.

By 1870, California ranked twenty-fourth in population and sixteenth in manufacturing output (gold mining excluded). Table 9.3 shows 1870 population, manufacturing output, and output per capita for California and six other states with larger populations and larger manufacturing sectors. California manufacturing output per capita exceeded that of Ohio and Illinois, but was still well behind the others.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Output per capita is not a flawless measure of the manufacturing sector, but it is indicative and does compensate for differences in population.

By 1880, California still ranked twenty-fourth in population and fifteenth in agricultural output, but had moved up to twelfth in manufacturing output.[31] California's per-capita manufacturing output in 1880 was about the same as Illinois's, and still greater than Ohio's. California manufacturing per capita also increased relative to all of the states shown in Table 9.3, except Illinois.

By any measure then, California manufacturing grew rapidly during the Gold Rush. Rapid simultaneous development in mining and agriculture, or more rapid industrial growth in later years, do not alter this. It will be argued below that this rapid growth was accompanied by the development of an industrial core that laid the foundation for the state's future industrial growth. There was no significant delay or lag in developing California industry, and while the obstacles to growth were formidable, the history of California industry is a story of overcoming these obstacles, not succumbing to them.

The Effect of the Gold Rush on California Industries

The Gold Rush influenced California industries in three ways. First, the Gold Rush precipitated the population boom that created a soaring demand for a wide range of consumer and producer goods. These products often had little or no direct connection to gold mining. In these cases, there was nothing unique about the gold industry, it was merely the sector that fueled an economic expansion from which other industries benefited. Second, direct gains accrued to industries linked to the gold industry. An expanding gold industry demanded inputs and technologies from supplying industries. Third, and perhaps most important, technologies and industrial infrastructure developed for the gold industry were transferred to other sectors and products. The gold industry was the catalyst for the creation of an industrial infrastructure centered around a foundry-machine shop core.

Links to Consumer Goods Industries

The increased demand for food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and construction materials was initially met mostly with imports. For example, glass bottles were in such demand that old bottles from Honolulu, Tahiti, and Mexico were collected and shipped to San Francisco.[32] Imports from the East Coast followed, but breakage and transportation costs doubled their price. Local production of glass began in San Francisco as early as 1862. Similarly, the first stone house built in San Francisco was constructed in 1854 of imported Chinese marble.[33] But within two years, stone from

California quarries was replacing imports. Likewise, California initially imported all of its flour, and the first flour mills in the state got their start remilling imported flour that had spoiled in transit. Flour production expanded rapidly as California's wheat crop grew, and flour imports ceased in 1860. California flour production continued to expand, exporting to world markets.

In contrast, California breweries began immediately after the perishable beer shipped from the East Coast spoiled in transit.[34] By 1881, San Francisco had thirty-eight breweries, the first erected in 1850. Many California brewers specialized in "quick-brewed beer" that was brewed in only three days, no doubt sacrificing taste to speed and quantity.

San Francisco grew first as a bustling trade center before becoming the center of California industry. Table 9.4 shows the date and location of selected California industries established by 1860. San Francisco's domination is apparent, as is its diversity. It is also hard to discern any delay or lag here.

By 1860, California's largest industries, in order of size of output, were flour milling, lumber, sugar refining, machinery (including steam engines), and malt liquors. The largest industries in 1870 were flour milling, lumber, machinery, boot and shoe findings, sugar refining, quartz milling, and cigar making. These were mostly consumer goods industries (except machinery and, to a certain extent, lumber) that thrived in the general prosperity initiated by the Gold Rush.

Flour and lumber mills proliferated. Ninety-one flour mills and 279 lumber mills were in operation by 1860, compared to only 2 and 10, respectively, in 1850. The growth of California flour milling is shown in Table 9.5. Flour mills produced half of the food (by value) produced in the state. In addition, flour and lumber mills were capital intensive, further augmenting the demand for California machinery. California flour mills employed more than 12 percent of the state's steam engines in 1870.

California boot and shoe production is shown in Table 9.6. The sharp increase after 1860 in output-value probably reflects the disruption of imports during the Civil War. The figures in Table 9.6 also suggest that California producers were able to weather the competition from the resumption of imports following the end of the war and the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

California woolen mills provide a good example of how California's post-gold-rush agricultural success has drawn attention away from the state's industrial progress. California's first woolen mill was opened in San Francisco in 1858.[35] By 1881, there were thirteen mills operating in the state, consuming 20 percent of the state's wool and producing woolens valued at $4.85 million. Woolen imports in that year amounted to another $5 million to $6 million. Eighty percent of California wool was exported unworked. According to Hittell, the source for these figures, this high export ratio was "one of the most striking examples of the underdeveloped condition

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

of our manufacturing industries."[36] However, if California woolen mills had produced woolens sufficient to replace all of her imports in 1881, it still would have exported 60 percent of its wool. The problem, if that is what it should be called, was not an underdeveloped woolen industry, but rather a large wool output.

The Gold Rush also saw the beginnings of many well known names and labels. Domingo Ghirardelli opened a chocolate factory in San Francisco in 1852. Claus Spreckels began his sugar refinery business in San Francisco in 1863. Levi Strauss

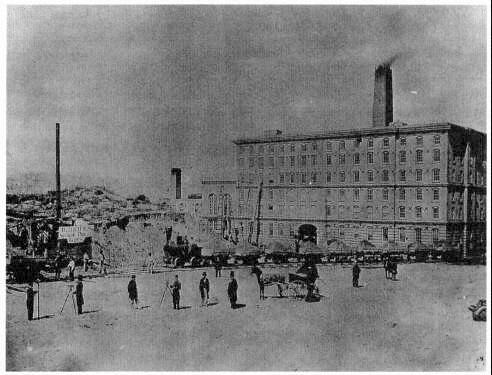

David Hewes's steam paddy, which carried sand for bay fill, passes before the San

Francisco Sugar Refinery at Harrison and Eighth streets. Constructed in 1856 by a

corporation headed by the Forty-niner George Gordon, this was the first sugar refinery

in California and the beginning of an industry that ultimately would emerge as the most

economically important in the city. Relying at first on raw sugar from Batavia and Manila,

Gordon's refinery was capable of processing sixteen thousand pounds of sugar a day.

California Historical Society, FN-10655 .

originally made trousers for California miners and workers. Folgers Coffee and Schilling Spices both got their start in San Francisco. The Studebaker Brothers, later automobile pioneers, started in a carriage shop in the gold-mining town of Placerville.

Links to Producer Goods Industries

Many industries were connected to the gold industry through supplier-customer links. These could be either forward or backward linkages. Forward linkages are connections with "downstream" industries, that is, industries that utilize the product. In contrast, backward linkages are "upstream" connections to industries that provide raw materials or machinery used in the production of the product in question.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Forward linkages to gold mining included jewelry making, gold beating (to produce gold leaf), and coin minting. Jewelry and gold beating were undertaken in San Francisco, but neither was particularly significant. In 1850, however, private mints in San Francisco began minting gold coins to alleviate California's currency shortage. These private mints operated until a U.S. mint opened in San Francisco in 1854.[37]

While forward linkages were not extensive, gold's backward linkages were very significant. To appreciate these connections, it is important to see gold mining as an industry , rather than as a discovery or find. Perhaps the most common image of the California gold miner is that of a beamed, grizzled prospector bent over a stream, panning for gold. While this may have been typical of many of the early Forty-niners, it does not accurately reflect gold mining after it quickly became more of an industry and less of an adventure.

There were different types of gold mining with different links to other industries. The Forty-niners used simple placering techniques, including panning and the use of rockers, toms, and sluices. Before 1860, placer gold mining accounted for about 99 percent of the gold produced in California.[38] All placering techniques used water, motion, and trapping mechanisms such as ridges and cleats to separate gold from mud and gravel. While larger gold flecks could be picked out of the pan or sluice,

The Pioneer Woolen Mills at Black Point, San Francisco, 1865. Though wool was sheared,

carded, spun, and woven at the Franciscan missions at least as early as 1786, it was not until

nearly three-quarters of a century later that the manufacture of woolen goods arose as an

important industry in California. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

this mechanical separating left most of the gold behind. To improve yields from placering (and other types of gold mining as well), mercury, or quicksilver as it was commonly called, was added to concentrated ores. The mercury formed an amalgam with gold and silver. The amalgam was collected and the mercury driven off with heat, leaving the precious metals behind. Some of the mercury could be recovered for subsequent use, and the gold and silver were separated with acids. The backward linkages from placer mining thus included links to quicksilver, lumber, and the acid industry. To meet the demand from mints and mines, acid production in San Francisco began in 1854. Lumber was needed for rockers, toms, and sluices. Quicksilver, mined from California mines, was indispensable to gold and silver recovery until the invention of the cyanide process in 1890.

By the mid-1850s, however, simple placer mining sites had been played out. Hydraulic mining and dredging, more advanced forms of placering, were developed to

work less accessible ores. Both hydraulic mining and dredging are very capital intensive, with more extensive and significant links to other enterprises. California industry expanded to meet the demand for leather hoses, pumps, and nozzles. The dams and flumes required for hydraulic mining also dramatically increased the demand for lumber. Lumber mills responded with special planks, narrower at one end so they could be readily attached end to end, to construct the long wooden channels for hydraulic sluices. Leather hoses were made in San Francisco starting in 1857. California oak-tanned leather was stronger than leather used by eastern and European hose producers.[39] As a consequence, California hoses were superior products, stronger and less expensive. Eventually, California leather hoses were exported around the world and were used extensively by fire departments until rubber hoses replaced them after 1874. Nozzles, first made of wood, were soon crafted out of metal in California foundries. Dredging was initially tried in 1850 on a river boat converted to the task of capturing gold from river bottoms near Marysville.[40] However, dredging did not become important until after 1880, when court rulings limited hydraulic mining. The Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works of San Francisco produced a larger dredge in the 1890s that ignited interest in the technology. Dredging remained an important mining technique into the 1940s.

Quartz, or hardrock, mining had the greatest impact on California industry. Gold embedded in quartz was discovered as early as 1849, and was followed by a wave of speculative excitement. But the excitement ended in a bust, and the quartz mining that survived was carried out on a small and unprofitable basis for many years. Rod-man Paul observed that as late as 1859-60, the cash returns to quartz mining could be written off as unjustified were it not for the unique technologies invented in this activity.[41] Later, hardrock gold mining in California, Comstock silver mining, and the development of a California mining equipment industry owed much to the persistence of these early ventures.

Hardrock mining entailed tunneling to reach the ore, digging it out and bringing it to the surface, and finally crushing and processing the ore. All stages of this activity were capital intensive and required specialized machinery. To get at the ore, drills and explosives were used to dig through rock. San Francisco foundries and machine shops developed drills that reduced friction, breakage, and fuel consumption.[42] Hand drills were quickly replaced by steam-driven patent drills. Steam engines were originally taken down into the mines to power the drills, but this drastically reduced their efficiency. The air compressor permitted steam engines to remain above ground with hoses supplying the compressed air to the drills. More leather hoses were needed.

Explosives were also used to get at ore. Imported black powder was originally used, but transporting it was dangerous, and shipments were disrupted by the Civil War. Within the state, the California Powder-Works opened near the city of Santa

Cruz in 1861 to produce black powder.[43] The company subsequently opened a second facility near Point Pinole to produce its highly explosive "Hercules" powder. Acids were used in the manufacture of these explosives, leading to the development of yet more satellite industries. California explosives were shipped throughout the West for use in mines and railroad construction and were exported to Canada, Hawaii, and Latin America, especially Mexico.[44] California's explosives industry, however, did not lead to the development of an armaments industry, at least not in the nineteenth century. The manufacture of guns remained an eastern specialty. Blasting techniques developed in the gold mines, on the other hand, were applicable to the mining of other minerals. One of the more interesting applications was found in California's marble quarries, where precision blasting of marble blocks was perfected.

All but the shallowest of hardrock mines required drainage, venting, and hoisting. Timbers and lumber were needed for hoists, supports, and shoring. Hoisting machines and steam engines were produced by California foundries and machine shops; San Francisco wire and cable makers made cable for hoists and ore trams. In addition, most mining machines used leather belts in conveyers and drives; by 1861, four San Francisco firms manufactured leather belts superior to competing eastern and European products.[45]

San Francisco foundries also produced most of the pumps used to pump water out of California and Comstock mines.[46] The Risdon Iron and Locomotive Works manufactured water pipe for use in Virginia City, as well as irrigation pipe for Hawaiian plantations, and made the much-acclaimed pumps for the Chollar-Norcross Mine.[47] Pumps provide an interesting example of how California firms overcame the obstacles working against West Coast manufacturing. California foundries produced mostly mining pumps, which were large and designed and manufactured to order. California foundries relied on their design expertise, their proximity to mining company customers, and superior service to compete against cheaper eastern imports. Although they succeeded in securing the bulk of the mining business, they could not compete with eastern firms in the market for smaller pumps for cisterns, household use, or small business applications.[48] Small eastern pumps were mass-produced, employing cheap child labor, and sold for up to 60 percent less than local, West Coast rivals. California producers enjoyed neither the labor force, the low wages, nor the market size that would have enabled them to compete in this market.

California steam engines were also developed for the mines. The 1870 census records forty-two steam engines in use in California mines, many made by California companies.[49] California ranked ninth in the number of steam engines used in mines. This is all the more impressive in light of California's water-power resources. California also ranked first in the use of waterwheels as a power source in mines, employing 70 of the 134 waterwheels in use in the United States in 1870. While steam

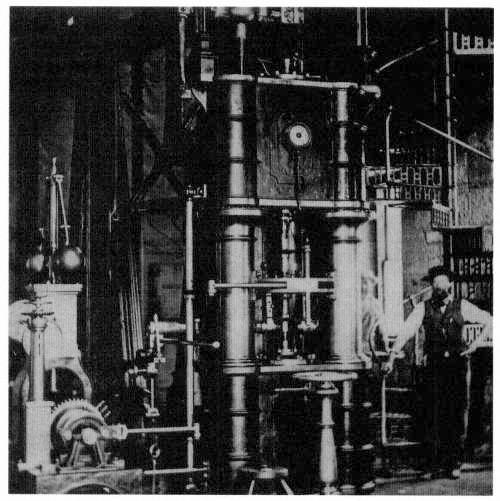

A workman poses with one of the massive steam engines at the mill of the Gould & Curry

Mine, Virginia City. On the Comstock Lode, powerful engines manufactured in San Francisco

drove a range of hardrock mining machinery, including pumps, compressors, hoists, and stamp

mills. Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

engines were developed for the mines, their use spread to other California industries. In 1870, there were 604 steam engines in use in the state's manufacturing establishments. The lumber industry, flour mills, distilleries, and the iron trades often utilized steam power. The assertion that California industry lagged because it failed to embrace steam engines is simply not correct.

Processing quartz ores proved to be a formidable challenge. Ore-bearing rock was first broken into smaller, more manageable pieces. This was followed by grinding. California initially imported grinding machines from Europe for this task, but

these, according to John Hittell, proved to be "fancy and usually worthless.[50] They were quickly abandoned in favor of arrastras , simple Mexican devices that dragged heavy stones over the ore. A Chilean version substituted a mill stone.

Slow and ineffective, arrastras were soon replaced by California stamp mills, which used heavy iron feet, mechanically lifted and dropped, to grind the ore. They were produced by California foundries and machine shops. Rodman Paul calls hydraulic mining and the California stamp mill the crowning technological achievements of the California Gold Rush. The stamp mill was especially important in encouraging the development of local foundries and mining technology.

Because about two-thirds of the gold in quartz ores was not recovered by early processing methods, California miners, working with local foundries and machine shops, rapidly developed other techniques to improve yields. Paul claims that more progress was made in the first twelve years of the California Gold Rush than had occurred over the previous several centuries.[51] Californians invented concentrators, machines that generally used conveyer belts and shaking motion to further concentrate ores before amalgamation. They also developed a second grinding process, often with mercury added. In the late 1850s, metal pans with mechanical stirring devices and steam heat emerged to facilitate amalgamation. These techniques were later incorporated into the vats used in the Washoe process on the Comstock.

All these mining developments stimulated California industry. The effect on the metal working industries appeared immediately in census data. In 1850, half the state's manufacturing establishments not involved in gold processing were blacksmith shops. Since there were no separate census categories for "foundries" or "machine shops," these were included in blacksmithing. In terms of value of output, California blacksmithing ranked third in the nation, behind only New York and Pennsylvania. This is remarkable for a state that was less than two years old. By 1880, the output-value of California foundry and machine shops, now separately enumerated, ranked eleventh among the states, but seventh on a per-capita basis.[52] In blacksmithing, California ranked seventh in output, and second in output per capita.

The size of the iron working trades is obscured by the increasing complexity of the census. This category includes blacksmithing, foundries and machine shops, wire and cable making, iron pipe, pumps, steam engines, saws, shipbuilding, wheelwrighting, and other types of enterprises. These activities formed the core of nineteenth-century industry. After 1850, successive censuses expanded the reporting categories. While this was more accurate and useful for some purposes, the growth of iron working in the aggregate is lost. Table 9-7 recombines these separate categories in the census into an aggregate "iron working trades" industry. The increase in iron working trades, despite the state's poor natural endowment of iron ores and coal, is striking.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Spread of Gold Industry Technologies

Technologies developed for the gold industry were not confined to that sector. As pointed out above, such devices as hoses, steam engines, and pumps all found their way to other sectors of the economy. Nathan Rosenberg has called this process "technological convergence," and maintains that it was vital to creating the machine tool industry on the East Coást in the early nineteenth century.[53] The textile industry, he argues, was the initial catalyst for technological convergence on the East Coast.

Technological convergence can be seen in California, but with gold mining serving as the catalyst. The blacksmith shops, foundries, and machine shops that produced the equipment for the gold industry also created technologies and an industrial base that could later be employed in shipbuilding, in the defense industry, and in other types of manufacturing. By the 1880s, for example, California firms were supplying most of the machinery used on Hawaiian plantations and in sugar cane processing, replacing European imports.[54] California's hydroelectric power also had early connections to the Gold Rush.[55] The first hydroelectric operation in the state was undertaken in northern California in 1879. Soon after, Lester A. Pelton, a millwright and carpenter in the Mother Lode town of Camptonville, created the turbine wheel generator, building on technology developed for gold mining.

The cable industry provides another example of technology dissemination. A. S. Hallidie, president of the California Wire-Works Company, made screens for quartz mills and flour mills, riddles, birdcages, fenders, fireguards, and many other wire products for use in kitchens and industry. In 1868, Hallidie invented a wire ropeway for transporting ores. Soon after, he used the same technology to invent the cable railway, which powers San Francisco's famous cable cars.[56]

California's oldest foundry, the Union Iron Works, also illustrates how gold mining technologies were transferred to other industries. Founded in 1849 by three

brothers, Peter, James, and Michael Donahue, the Union Iron Works overcame the iron shortage by buying scrap iron made plentiful by the fires that destroyed San Francisco in the early 1850s. As did a host of other San Francisco foundries, it used the scrap metal and iron imported as ballast to make mining equipment. The Union Iron Works produced a large share (90 percent by one estimate) of the mining equipment used by California and Comstock mines.[57] From mining equipment, the Union Iron Works branched out to supply other iron working industries. It built the first locomotive on the West Coast in 1865. It repaired ships, made ship engines, and assembled ships, including the first steel ship made on the West Coast, the collier Arago , in 1885. The company then won one of the first major Navy construction contracts awarded a California firm and built the first steel warship produced on the West Coast, the Charleston , in 1888. In addition, Peter Donahue was instrumental in constructing street railroads.

One striking difference between California producers and their eastern counterparts that encouraged technology dissemination was the degree to which California producers did not specialize. Eastern foundries and machine shops tended to specialize in the production of a few products. However, with many smaller local markets, California foundries often made more than twenty products, "everything that is in demand, from mining-machinery, locomotives, steamship engines, sugar-mills, and architectural iron-work, down to the various small articles required for every-day use.[58] Diversity was also typical of California's agricultural equipment producers.[59]

The difference between eastern and western foundries was probably due to the wider markets in the East, which facilitated specialization. It was also due to the mining origins of western foundries. Mining equipment was very diverse and often custom-made. San Francisco foundries survived by staying flexible, by experimenting, by innovating, and by producing a wide array of products. Carey McWilliams argued that a willingness to experiment was a long-standing hallmark of California that had taken root in the state's mining past.[60] Equally important, the diversity of California foundries and machine shops probably speeded up the process of technological diffusion because it became more of an in-house process on the West Coast, facilitating easier transfer of technology from product to product.

Finally, the discovery of other minerals was often a by-product of the search for gold during the Gold Rush. Silver, borax, petroleum, coal, chromite, and copper were discovered as gold seekers scoured the countryside. The Comstock Lode, primarily silver, was discovered by California miners looking for gold.

There was, however, one notable exception to this pattern. When California was still part of Mexico, quicksilver was discovered at New Almaden, near San Jose, in 1845. While its discovery and initial development preceded Marshall's discovery, the New Almaden Mine (and the other California quicksilver mines that soon fol-

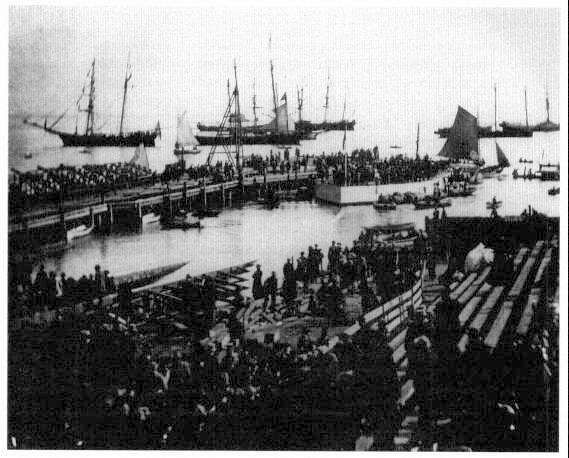

San Franciscans press forward to watch the launching of the ironclad monitor Camanche on

November 14, 1864. Assembled at the Union Iron Works with parts manufactured in the East and

sent around the Horn, it was the second warship built in California. Slightly more than twenty

years later, the Union Iron Works made a successful bid to construct the U.S. Navy's Cruiser No.

2, the Charleston , one of the first vessels in the country's "New Navy" and the ship that

inaugurated the modern era of shipbuilding in California. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

lowed) enjoyed robust demand during the Gold Rush. Among mineral industries, quicksilver was second only to gold in output-value until the end of the nineteenth century. More importantly, it is hard to imagine what the Gold Rush and the Comstock silver rush would have been like in the absence of local supplies of quicksilver. In the last half of the nineteenth century, California produced half of the world's supply of mercury, breaking a world quicksilver cartel by flooding world markets with cheap quicksilver.[61]

Conclusion

Through backward linkages, a California industrial nexus was created in the Gold Rush. Its features and characteristics were determined by the responses of industrial firms to increasing consumer demand and to the demands emanating from the gold mining industry. In the process, California's industrial capacity was created. An industrial core, centered around foundries, machine tool companies, and the iron working trades, developed. This base became the foundation for future industrial expansion.

While the Gold Rush increased the demand for both consumer and producer goods, care must be taken to keep this factor in perspective. Demand is never sufficient alone to explain development. Boomtowns the world over have generated similar demands, but few managed to create an economic base that survived the exhaustion of the mineral that brought them into being. Virginia City, for example, did not become another San Francisco. Gold presented the opportunity, but the real story is found in the response. Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Gold Rush was not its ability to attract gold miners, but its ability to attract entrepreneurs who seized the opportunities that gold offered.