14—

COASTAL ZONE RIPARIAN SYSTEMS

MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION CHALLENGES IN AN AREA OF RAPID DEVELOPMENTAL CHANGE

Protection of Riparian Systems in the California Coastal Zone[1]

John Zentner[2]

Abstract.—Protection of riparian systems is a major concern in coastal California. The Coastal Plan, written in 1975, advocates riparian protection through watershed management plans. The Coastal Act, passed in 1976, contained strong riparian corridor protection policies but deleted the concept of watershed management. This paper explores past actions of the California Coastal Commission to protect riparian systems and discusses the contradiction between strong riparian protection and relatively weak watershed regulation.

Introduction

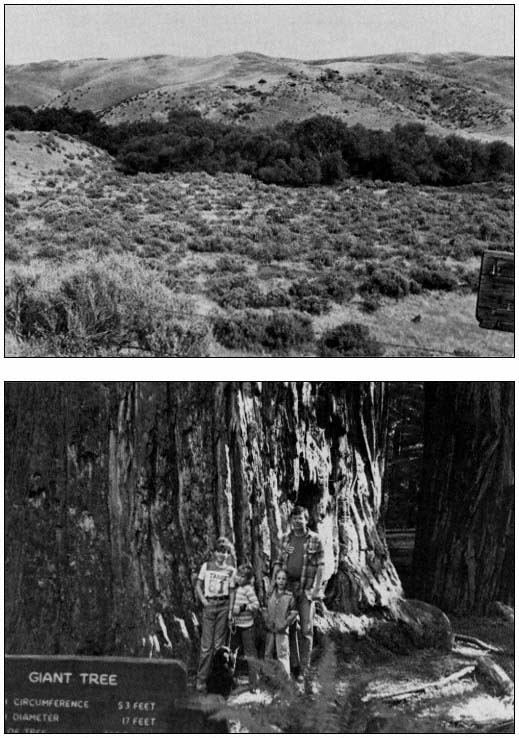

Despite the efforts of many federal, state, and local agencies, private organizations, and concerned citizens, riparian vegetation continues to disappear at an alarming rate in California (Beer 1978). Although no separate data are available for coastal areas, subjective observations indicate that this loss also holds true in the state's coastal watersheds.

The California Coastal Commission, a state agency within the Resources Agency, is charged with protecting coastal resources, and is concerned about continued degradation of riparian systems. Through its power to regulate development, the Commission, in conjunction with local government, has the ability to guide much of the growth and change in the coastal zone. This paper discusses the genesis of the Commission, what it has done to protect riparian systems, and what the future may hold.

Background

A Governor's Panel recommended in 1936 that a coastal commission be established. However, it was not until 1969 that the first legislation toward that end was introduced.[3], [4] When the Legislature failed to pass a coastal bill, activists gathered enough signatures to place an initiative on the ballot. The initiative, Proposition 20, passed by a 55.1% margin in November, 1972. Proposition 20 established the predecessor of the Coastal Commission, the California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission (CCZCC). The CCZCC was charged with writing a coastal plan in three years and regulating development in the coastal zone. Under Proposition 20 the coastal zone extended landward to the "highest elevation of the nearest coastal mountain range" except in Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego Counties where it extended to the highest elevation or 8 km. (5 mi.) inland, whichever was less. However, the permit zone only went about 900 m. (1,000 yds.) inland. Thus the "coastal zone" included most coastal watersheds but CCZCC permit authority over development extended only a relatively short distance inland.

In 1975, the CCZCC adopted the California Coastal Plan and submitted it to the Legislature. In addition to an inventory of coastal resources and policies on coastal planning issues, the Plan contained several provisions on protection and management of riparian systems as follow:

Coastal streams are vital to the natural system of the coast;

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] John Zentner is Resource Ecologist for the California Coastal Commission, San Francisco, Calif. Opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect views of the California Coastal Commission.

[3] Marsh, Linda. 1978. The California Coastal Commission: Who's minding the shore? South Bay Tribune, Manhattan Beach, Calif. 12 July, 1978.

[4] In 1965, the Legislature created the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) to regulate development in San Francisco Bay. BCDC became an important precedent for creation of a coastal commission. See Odell (1972) for a history of BCDC.

coastal streams directly affect the coastal environment;

they are vital to anadromous fish that live in both salt and fresh water;

they collect and transport sand from the watershed to supply coastal beaches;

they are valuable to the aesthetic and recreational enjoyment of coastal waterways; and

they are interrelated with the estuarine systems that in turn are essential to the productivity of the marine environment.

Coastal streams also significantly influence flooding, natural ecosystems, agricultural water supply, and groundwater recharge within the coastal land environment. Watershed areas are thus an ideal focus for developing management techniques to maximize utilization and preservation of natural resources of the coastal zone. (California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission 1975)

These findings linked riparian system protection with watershed management. Thus, basic policy for CCZCC riparian system protection would be establishment of comprehensive watershed management. Policy 22 provided the guidance and detail on development of these plans:

Prepare and implement comprehensive watershed management plans:

a. Procedure for Preparation and Implementation of the Plans. A lead agency at the State level designated by the Legislature (e.g., the Resources Agency, Department of Conservation, or Water Resources Control Board) shall coordinate watershed planning and work closely with affected local governments, other State agencies, and Federal agencies. The coastal agency shall participate in an advisory role in the overall watershed planning program and watershed plans beyond the coastal resource management area.

b. Content and Goals of the Plans. The watershed management plans shall relate upland and shoreline land use management to the protection and restoration of the marine environment; use consistent assumptions, standards, and criteria for determining appropriate future population levels and land uses within each coastal watershed; consider statewide interbasin interests (e.g., true costs of water importation); and otherwise assure that allowable development conforms to the Coastal Plan. The plans shall stress the protection of coastal groundwater resources, streams, wetlands, and estuaries, and shall prevent significant adverse impacts on these resources . . . (ibid .)

Watershed management is used by many state water resource departments for water supply planning. However, these departments have rarely considered themselves land-use planning agencies, and have generally tried to simply manage water supply to meet demand (White 1969). It was partially the failure to resolve the increasingly complex conflicts between riparian and watershed protection and water regulation that led to an outcry for more land-use oriented watershed planning (see Howe 1978; Burke and Heaney 1975).

The Coastal Plan reflected this concern by incorporating resource protection and the concept of limiting growth to the level of available resources. However, the land-use planning aspect of these plans provoked substantial concern among local governments. Opposition to further state control was so great that when the Coastal Plan was modified and adopted by the Legislature as the Coastal Act of 1976, the watershed management policies of the Plan were not included in the Act.

Clearly, including coastal watersheds in the coastal zone makes good sense. Upstream developments affecting downstream areas, especially wetlands, could be regulated and the multitude of different governmental bodies coordinated—but the political effort would be considerable. The amount of land which would have been added to the coastal zone was enormous, especially in the north state. This factor alone made it politically infeasible to include watershed management in the Coastal Act.[5]

The Act is, however, very protective of the riparian corridor. Section 30236 states:

Channelizations, dams, or other substantial alterations of rivers and streams shall incorporate the best mitigation measures feasible, and be limited to (1) necessary water supply projects, (2) flood control projects where no other method for protecting existing structures in the flood plain is feasible and where such protection is necessary for public safety or to protect existing development, or (3) developments where the primary function

[5] Douglas, Peter. April, 1981. Personal conversation. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco, Calif.

is the improvement of fish and wildlife habitat.

Section 30240 states:

(a) Environmentally sensitive habitat areas shall be protected against any significant disruption of habitat values, and only uses dependent on such resources shall be allowed within such areas.

(b) Development in areas adjacent to environmentally sensitive habitat areas and parks and recreation areas shall be sited and designed to prevent impacts which would significantly degrade such areas, and shall be compatible with the continuance of such habitat areas (California Coastal Act of 1976).

Other portions of the Act established six Regional Commissions, defined development broadly, gave the Commission the power to approve, deny or condition development permits, and directed each local jurisdiction to develop a local coastal plan, which, when certified by the Commission, would give the jurisdiction permit authority over coastal development. In addition, the Act seeks to minimize flood and other hazards and to assure that, in case of policy conflicts, decisions will seek a balance which is most protective of natural resources. The definition of coastal zone also underwent some changes. The coastal zone now extends 4.8 km. (3 mi.) seaward and averages 915 m. (1,000 yds.) inland from the mean high tide line. This distance is reduced in some built-up areas, such as parts of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, but can be expanded up to 8 km. (5 mi.) where necessary to protect significant coastal resources.

The remainder of this paper discusses pertinent Commission actions on permits, local coastal plans, and other areas which have affected riparian systems.

Permits Affecting Protection of Riparian Systems

As indicated above, the Commission has permit authority over a wide range of activities within the coastal zone. For this paper, a brief survey was made of permits which were appealed to the state Commission after a regional commission decision, and which were concerned with protection of riparian systems. These are presented below by the issue which seems to characterize each best. Unless otherwise noted, these appeals are referenced by their Commission appeal number.

Development in a Riparian Corridor

The Los Virgenes Municipal Water District sought a permit to expand its handling facility in Monte Nido Valley in the Santa Monica Mountains. The applicant wished to grade and channelize a portion of a small creek to construct a new shop and maintenance building in proximity to the other structures. The Commission approved the permit but required, as a condition of approval, that no grading and channelizing be done in the riparian corridor and that the shop be relocated.

A second major issue which surfaced with this permit concerned impact of the wastewater discharged to Malibu Creek from the facility. The Water District collected data on its discharge for an entire year, and collaborated with the Regional Water Quality Control Board in a report which concluded that the discharge had no effect on algae, fish, or macroinvertebrates in the creek. Based on that report, the Commission concluded that the discharge was not harming the biological productivity of the stream and approved the permit (Appeal 39–80).

The Orange County Flood Control District applied for a permit to remove from a channelized portion of San Juan Creek in Orange County 280,000 cubic yards of sediment deposited by a storm. The Commission aproved the permit on the condition that the flood control district use the excavated material for beach replenishment, thereby avoiding potential shoreline erosion problems. In this case, the Commission made extensive findings showing that removing creek sediments would deplete sand replenishment of downcurrent beaches (Appeal 200–80).

Cumulative Impact of Incremental Developments

A private landowner applied for a permit to divide a four-acre parcel into two parcels for residential development in Cold Creek Canyon in Malibu. Much of the site is either within the Cold Creek Significant Ecological Area (SEA) or the SEA buffer zone as designated in the Commission's Malibu/Santa Monica Mountains Area Plan. The Commission's interpretive guidelines contain policies recognizing the cumulative impacts of new development in Cold Creek Canyon and recommend against new land divisions in the area. The Commission denied the permit, finding that the project would set a precedent by allowing more land divisions in the canyon, thereby severely undercutting the guidelines. The Commission decided that the cumulative impacts of the buildout in the canyon would have significantly degraded the creek's riparian systems (Appeal 360–80).

The Commission has not blocked all development in this area, however. Another applicant was granted a permit for terracing a hillside above Cold Creek for orchard and vineyard planting. The Commission found that this low-intensity use, if properly buffered, was compatible with protection of the biological productivity of the creek (Appeal 53–79).

Setbacks for Development

A private landowner applied for a permit to construct a single-family residence on a narrow

lot in Los Flores Canyon in Los Angeles County. The lot was not wide enough for a 50-ft. setback between the septic tank and the stream. The Commission denied the permit, noting that some riparian vegetation would have been destroyed by the riprap needed to protect the house during moderate floodflows. In addition, the Commission found there was not enough room for an adequate stream buffer (a minimum of 30 m. (100 ft.)) from the house (Appeal 61–80).

Timber Harvesting Along Riparian Corridors

Prior to passage of the Coastal Act, the Masonite Corporation applied for a permit to cut timber on 170 ha. (420 ac.) of land along the Albion River in Mendocino County. The lumber company proposed to leave 30-m. (100-ft.) natural buffers along the edge of the river in accordance with the Forest Practices Act, although the company indicated it would harvest the trees left in the buffer after the rest of the trees had been cut. Several local residents spoke in opposition to the permit, requesting that at least 60- to 90-m. (200- to 300-ft.) buffers be required to protect local salmon spawning grounds and blue heron rookeries. The Commission approved the permit but required 60-m. buffers along the river (Healy 1977).

Under the Coastal Act, the Commission was not given the authority to regulate commercial timber operations larger than 1.2 ha. (3 ac.). The Legislature determined that the Forest Practices Act and the Board of Forestry should have sole jurisdiction over larger operations. However, the Coastal Act directed the Commission to submit to the Board of Forestry a list of forest special treatment areas where logging could adversely affect rivers or streams. The Board later adopted these special treatment areas and certain other changes in forestry practices also suggested by the Commission (Blumenthal 1979).

In another case, after the Act was passed, a private landowner applied for a permit to harvest timber, about five cords per year, on a 1-ha. (2.5-ac.) parcel near the Eel River Delta in Humboldt County. The Department of Fish and Game raised concerns about the permit, fearing it could set a precedent for logging other parcels in that area. The Department, the Commission and Humboldt County had been working extensively with local landowners to develop riparian protection measures for the delta. The Commission denied the permit and made the finding that, in order to fully protect the riparian system, no cutting could be allowed until a detailed, comprehensive management plan for the area could be developed (Appeal 68–81).

Local Coastal Programs

Each city or county with jurisdiction in the coastal zone is required to prepare a Local Coastal Plan (LCP) under the Coastal Act. An LCP is composed of the Land Use Plan (LUP) and zoning ordinances implementing the LUP. The Commission reviews each LCP and decides on its conformity with the Coastal Act. The following section discusses two LCPs submitted by the County of San Mateo and the City of Oceanside.

San Mateo County

The San Mateo County LCP, approved 5 December, 1980, was the first county LCP to be certified by the Commission. As one of the earliest plans, it has often been held up as a model for its resource protection policies. The riparian protection policies are especially strong:

Definition of Riparian Corridors

Define riparian corridors by the "limit of riparian vegetation" (i.e., a line determined by the association of plant and animal species normally found near streams, lakes and other bodies of freshwater: red alder, jaumea, pickleweed, big leaf maple, narrowleaf cattail, arroyo willow, broadleaf cattail, horsetail, creek dogwood, black cottonwood, and box elder). Such a corridor must contain at least a 50% cover of some combination of the plants listed.

Designation of Riparian Corridors

Establish riparian corridors for all perennial and intermittent streams and lakes and other bodies of freshwater in the Coastal Zone. Designate those corridors shown on the Sensitive Habitats Map and any other riparian area meeting the definition of Policy 7.7 as sensitive habitats requiring protection, except for man-made irrigation ponds over 2,500 square feet surface area.

Permitted Uses in Riparian Corridors

a. Within corridors, permit only the following uses: (1) education and research, (2) consumptive uses as provided for in the Fish and Game Code and Title 14 of the California Administrative Code, (3) fish and wildlife management activities, (4) trails and scenic overlooks on public land(s), and (5) necessary water supply projects.

b. When no feasible or practicable alternative exists, permit the following uses: (1) stream dependent aquaculture provided that non-stream dependent facilities locate outside of corridor, (2) flood control projects where no other method for protecting existing structures in the flood plain is feasible and where protection is necessary for public safety or to protect existing development, (3) bridges when supports are not in significant conflict with corridor resources, (4) pipelines, (5) repair or

maintenance of roadways or road crossings, (5) logging operations which are limited to temporary skid trails, stream crossings, roads and landings in accordance with State and County timber harvesting regulations, and (7) agricultural uses, provided no existing riparian vegetation is removed, and no soil is allowed to enter stream channels (San Mateo County 1980).

The plan also contained extensive policies on performance standards in riparian corridors, establishment of buffer zones, and permitted uses and performance standards in buffer zones. These policies form the basis of the County's LCP ordinances and are now being applied to new development in the coastal portion of San Mateo County.

City of Oceanside

Oceanside's LUP was a different situation. On 8 December, 1981, the Commission determined after two public hearings that several sections of the LUP were not in conformity with Coastal Act policies. One of the sections concerned development in the San Luis Rey River system. The Commission staff reported:

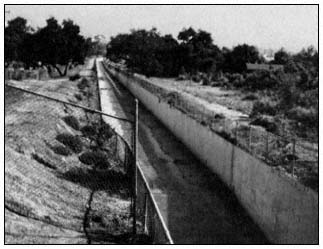

The City's LCP proposes the construction of State Highway 76 through the San Luis Rey River Valley. The proposed construction would include the removal of previously deposited spoils banks, grading of valley slopes, removal of approximately 4.4 acres of old growth riparian habitat, and construction of the expressway.

The currently proposed Route 76, as included in the City's LUP presents serious questions as to impacts on the habitat values of the valley. LCP policies to protect the sensitive resources of the river would require the City to:

a. Post signs at appropriate locations noting regulations on littering, offroad vehicles, use of firearms, and leash laws.

b. Encourage the California Department of Fish and Game to actively enforce the Fish and Game Code in the river area.

c. Require property owners to remove debris from their properties when fire or health hazards exist.

d. Monitor future public use of the river area to identify areas of overuse. If such areas are identified, take steps to restrict access commensurate with the carrying capacity of the resources.

e. Encourage CALTRANS to buy and restore the spoil bank on the south side of the river west of I-5 as a first priority. Acquisition of habitat for the endangered plant Dudleyaviscida shall be a second order priority.

f. Continue police and code enforcement against litterers, trespassers, offroad vehicles, and other violators.

The general nature of these policies would not adequately protect the habitat values of the area as is required by the Coastal Act. Major development in the area would disrupt endangered plant/animal species and result in an overall reduction in the resource values of the area.

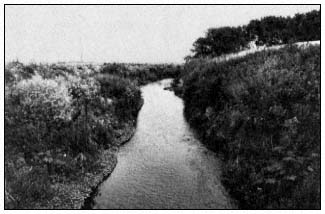

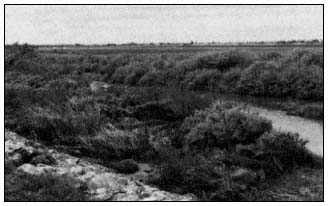

The San Luis Rey River area, as detailed in the CALTRANS biological Resource Analysis has biological significance in several respects: "As a natural ecosystem with great diversity surrounded by a highly urbanized area; as an important locality for rare and endangered species and utilization by a diverse assemblage of animals. The various plant communities have interrelationships that tend to indicate that the canyon is a single functioning ecosystem."

As the only publicly accessible coastal riparian stream corridor in San Diego County, the area has significant resource value. In testimony before the State Commission, the representative from the State Department of Fish and Game stated: "The systematic destruction of nearly every coastal river valley in Southern California confers added importance to the maintenance of this and the one or two other remaining river valleys where enough differing and contiguous habitats exist to function at an ecosystem level."

The San Luis Rey River, wetlands, and riparian areas are environmentally sensitive habitat as defined in Section 30107.5 of the Coastal Act. The expressway would be located in and/or adjacent to wetland riparian areas and in this location the project would have to be found consistent with Sections (a) and (b) of Section 30240. Section (a), discussed earlier, addresses the appropriate uses in an environmentally sensitive habitat area. Clearly a road is not a resource dependent use. The Commission has previously described and defined resource dependent uses in its certification of the County of Humboldt North Coast Area Land Use Plan. The Commission considered a variety of interpretations of resource dependent:

"(1) Resource dependent uses are those requiring the use of the ecosystem that led the area to be designated as environmentally sensitive habitat; (2) resource dependent uses may depend on one aspect of the total habitat, but that particular aspect must in turn relate to the functioning of the whole or be an integral part of the habitat value of an area; and (3) any use that relies on the existence of a resource that is simply present in the habitat area". In the North Coast Plan, the Commission considered whether timber harvesting and firewood removal in riparian corridors were resource dependent. Timber harvesting was clearly dependent upon trees as an available, renewable resource. However, locating a road in a riparian corridor is not dependent on any of the renewable/non-renewable resources of the San Luis Rey River area and therefore conflicts with Coastal Act policies regarding sensitive habitat.

As currently proposed, the project has adverse impacts on the environmentally sensitive habitat of the valley (noise, water pollution, air pollution, destruction of sensitive habitat, loss of endangered plants, isolation of remaining riparian areas from coastal sage scrub hillside, etc.) and would therefore require extensive mitigation. Such required mitigation measures have not been adequately identified by either the City or Caltrans. City policies would require transplantation of the endangered Dudleyaviscida , and Caltrans proposed to remove the spoils banks as mitigation for the removal of 4.4 acres of old growth riparian habitat, but other project impacts have not been addressed. In the absence of detailed mitigation proposals, the project would conflict with recommendations by the State Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that the whole river area should be afforded protection due to the uniqueness of its ecosystem.

In order to protect the integrity of the river and maintain the functional capacity of related habitat areas, the Commission finds that the policies proposed by the City of Oceanside are not in conformity with the policies of Chapter 3 of the Coastal Act (California Coastal Commission 1981a).

This LUP was an important test case for the riparian protection policies of the Coastal Act. The Commission subsequently approved the remainder of the City's LUP leaving the San Luis Rey River portion uncertified. This meant the Commission retains permit jurisdiction until the plan is revised and approved.

Special Guidelines

The Commission adopts interpretive guidelines primarily for use in reviewing coastal permit applications. These help interpret the Coastal Act and explain Commission precedent to insure consistency. The Statewide Interpretive Guideline for Wetlands and Other Wet Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Areas include considerable guidance on riparian habitat protection (California Coastal Commission 1981b).

Statewide Interpretive Guideline for Wetlands and Other Wet Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Areas

The wetland guideline was adopted February 4, 1981 after almost two years of public hearings and numerous revisions. It represents a major effort on the part of the Commission to protect wet environmentally-sensitive habitat areas. Although the guideline focuses primarily on wetlands, it also addresses riparian areas: defining rivers and streams, riparian habitat, permittable development in streams and rivers, and criteria for establishing buffer areas. Because buffer width can vary depending on the circumstances, the guideline requires the following factors be considered in an analysis: 1) biological significance of adjacent lands; 2) sensitivity of species to disturbance; 3) susceptibility of parcel to erosion; 4) use of natural topographic features to locate development; 5) use of existing cultural features to locate buffer zones; 6) lot configuration and location of existing development; and (7) the type and scale of development proposed.

The guideline has proven very useful in permit analysis. It provides solid, technical criteria for regulating development. This type of guidance is necessry to implement a complex statute, particularly when political and economic pressure are present.

Conclusions

This report demonstrates that the Coastal Commission has had considerable experience in protecting riparian systems in the coastal zone. Although not discussed as part of this report, other agencies, particularly the Department of Fish and Game, deserve a great deal of credit for this achievement. Their assistance and technical recommendations to the Commission have been greatly appreciated.

However, several gaps exist in this protection network. First, only riparian corridors in the coastal zone are protected. The riparian zone is part of a system which includes upstream headwaters and the surrounding watershed. Degradation of upstream areas is eventually reflected in downstream changes, ultimately in the coastal zone. Most of the watersheds are outside the

coastal zone; without good upstream protection it is somewhat futile to discuss long-term downstream regulation.

Second, watershed concerns such as erosion are complex and difficult to address issues. Development within a stream or river corridor is relatively easy to regulate because the resource is identifiable and the impacts direct. Sedimentation from an upslope development, for example, is difficult to trace; its impact difficult to assess. To complicate matters further, effects of sediment in the riparian corridor may be adverse or beneficial (beach replenishment, for example, versus silting of spawning beds).

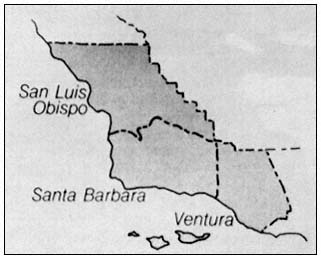

In addition, under the Coastal Act, removal of vegetation for agricultural purposes is not considered development—and therefore not regulated by the Commission. This problem is especially apparent in Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties where conversion of native vegetation to avocado production is drastically increasing the rate of sedimentation in coastal streams. Local governments are attempting to grapple with this problem with varying degrees of success.

Finally, the Commission itself has a very heavy workload and is subject to some political pressure. In accordance with state law, the regional commissions, which absorbed a large amount of work, were dissolved on 1 July, 1981. The Commission meets only eight days each month. Members of the public, seeking to speak to issues on the Commission's agenda are often limited to two to three minutes per item due to the large number of speakers. Given this situation, it could become easy to ignore the complexities of each issue and forego substantive discussions. This would jeopardize resource protection policies of the Coastal Act and the clear precedents the Commission has set to date.

Recommendations

It would be easy to simply recommend that watershed plans be prepared for all areas. The political pressure against such a measure would be overwhelming. It is more fashionable presently to talk about decreasing the role of government in our lives. On the other hand, who else will be concerned with an entire watershed and the riparian and instream systems it feeds? A neo-classical economic approach, such as advocated by Ostrom and Ostrom (1972), would place each watershed within the control of one user group, on the theory that someone who owns a resource will take better care of it than many individuals who have no incentive to safeguard the resource.

Instead, I would suggest an alternative. All jurisdictions within the state, whether in the coastal zone or not are required to prepare land use plans. I would recommend requiring them, through statute, to include a watershed element in such a plan. This could also include membership in a watershed planning program as suggested in the Coastal Plan.

Second, education on watershed and riparian issues needs to be greatly expanded. The effort which went into disseminating information on the importance of wetlands was enormous and began over a decade ago; issues of riparian protection are only beginning to become a subject of debate.

Riparian system protection in the coastal zone is a reality. The California Coastal Act assures protection of our rivers and streams within the coastal zone. However, that protection does not extend outside the coastal zone, nor does it adequately protect watersheds inside or out of the coastal zone. These limitations should be changed to insure adequate protection of riparian systems throughout California.

Literature Cited

Beer, Jack. 1978. Identifying habitat types and disappearance rates. p. 38–54. In : Proceedings of the instream use seminar. 178 p. California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento.

Blumenthal, Robert. 1979. Vegetation management report. California Coastal Commission special report. 68 p. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco, Calif.

Burke, Roy, and James Heaney. 1975. Collective decision making in water resources planning. 238 p. Lexington Books, New York, New York.

California Coastal Zone Conservation Commission. 1975. California Coastal Plan. December, 1975. State Documents and Publications Branch, Sacramento.

California Coastal Commission. 1981a. Staff report to the California Coastal Commission from Bob Brown, Chief Planner, and Michael Buck, Staff Analyst. 44 p. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco.

California Coastal Commission. 1981b. Statewide interpretive guideline for wetlands and other wet environmentally sensitive habitat areas. 46 p. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco.

Healy, R.G. 1977. An economic interpretation of the Californi Coastal Commissions. 270 p. Conservation Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Howe, C.W. 1977. Comparative analysis and critique of the institutional framework for water resources planning and management. 106 p. Office of Water Research and Technology, Washington, D.C.

Odell, Rice. 1972. The saving of San Francisco Bay. 115 p. Conservation Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Ostrom, Vincent, and Elinor Ostrom. 1972. Legal and political conditions of water resource development. Land Economics 48(1):1–14.

San Mateo County. 1980. Local coastal plan. 368 p. County of San Mateo, San Mateo, California.

White, Gilbert. 1969. Strategies of American water management. 288 p. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Plant Species Composition and Life form Spectra of Tidal Streambanks and Adjacent Riparian Woodlands Along the Lower Sacramento River[1]

John W. Willoughby and William Davilla[2]

Abstract.—Flora and life forms of the tidal streambank plant community along the Sacramento River near Collinsville, Solano County, California are compared to those of adjacent plant communities. The tidal streambank flora has a significantly smaller non-native component than the floras of adjacent riparian woodland and annual grassland communities. All three communities have developed in historically disturbed habitats. Rhizomatous herbs represent the predominant life form of the tidal streambank community. In contrast, the riparian woodland community has a much lower percentage of rhizomatous herbs and higher percentages of annual and woody species. Reasons for these differences are discussed.

Introduction

Plants growing in the intertidal zones of river systems are subjected to rather rigorous growing conditions. Regular, periodic inundation by fresh to brackish waters makes establishment and subsequent growth of vascular plants difficult. Relatively few plant taxa are capable of coping with such conditions. Some plant taxa, however, are totally restricted to intertidal areas of major river systems and are often rare (Ferren and Schuyler 1980).

In some river tidal areas, water salinity (and resultant soil salinity) may be a limiting factor to plant establishment and survival. This is especially true of riverine systems near oceans and bays where substantial volumes of salt water mix with the fresh water of the rivers.

This study examines the life form strategies of the vascular plants in the intertidal zone along the lower Sacramento River (herein referred to as the "tidal streambank" community). This community is compared to the adjacent riparian woodland community. Floristic composition and richness of these two communities and the adjacent annual grassland community are compared.

Study Area

The study area is located on the northern banks of the lower Sacramento River east of Collinsville, Solano County, California. The river at this point becomes part of the Sacramento/San Joaquin estuary. Study plots were located at the mouth of Marshall Cut, extending a distance of 1.0 km. east and 0.3 km. west of the cut along the bank of the Sacramento River. Riverbanks in this area were artificially created by levee construction designed to reclaim natural tidal marshland between 1900 and 1940 (Atwater etal . 1979). Tidal streambank and riparian woodland vegetation has developed on the levees during the short period since their construction. Inland of the levees, artificial landfill has resulted in displacement of former natural tidal marshlands. These recent fill areas now support a disturbed cover of annual grassland composed almost entirely of introduced plant species. An artificially flooded marsh behind the levee east of Marshall Cut is presently managed as a duck club. The flora and elevational zonation of vascular plants in this marsh/grassland mosaic have been considered elsewhere (BioSystems Analysis, Inc. 1979).

Methods

Tidal streambank, riparian woodland, and annual grassland plant communities were subjectively delineated using primarily physiognomic criteria. The riparian woodland community was identified by the presence of tree and shrub strata. In the few cases where these strata were poorly developed or lacking, this community was identified by the presence of herbaceous species

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] John W. Willoughby is Botanist/Range Conservationist, USDI Bureau of Land Management, Sacramento, Calif. William Davilla is Senior Botanist, BioSystems Analysis, Inc., San Francisco, Calif.

commonly associated with the riparian woodland community.

The criteria used to identify the tidal streambank community were: 1) its position between the river and the riparian woodland community; 2) the absence (with two exceptions) of woody species; and 3) the presence of species which flower in late summer to early fall. Upper limits of the tidal streambank community correspond roughly to the upper level of the levee banks inundated by maximum high tides.

The annual grassland community was recognized by its inland location, the absence of woody species, and the predominance of annual grass and forb species which flower in the spring.

A complete species list was compiled for each of these three plant communities. The life forms of each species were determined using available literature (e.g., Munz 1959; Mason 1957; Robbins etal . 1951) and field observations. Five life forms were recognized: annual, perennial herb (including biennials), rhizomatous perennial herb (including herbs spreading by stolons and creeping root systems), shrub, and tree. In a few cases a species may function as either an annual or a perennial. These facultative species were scored under both the annual and perennial herb categories. Suffrutescent (only obscurely or very modestly woody) plants were scored as perennial herbs. Woody plants which exhibit both a tree and shrub habit (e.g., Salix spp.) were scored as either shrubs or trees based on the principal life form exhibited in the study area.

Results and Discussion

The major environmental variables controlling the distribution of vascular plants in tidal marshes of the northern San Francisco Bay estuary are elevation and water salinity (Atwater and Hedel 1976). Elevation of marsh surfaces relative to tide levels determines the soil moisture content and frequency, duration, and depth of submergence, whereas the salinity of the water flooding a marsh determines the soil salinity (ibid .). Water salinity is an important influence in the regional distribution of tidal marsh plants; high soil salinity causes many plants to disappear toward San Francisco Bay, resulting in tidal marsh communities composed of only 13 or 14 native plant species (Atwater etal . 1979). Where water salinities are rather low, as in the Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta, tidal marsh communities are more diverse, containing some 40 plant species, most of which are relatively salt-intolerant—largely the same species that occur in freshwater marshes in California (ibid .).

Water salinities in the vicinity of the study area vary both seasonally and annually in response to the amount of freshwater flow from the river systems. Figure 1 shows the variation in mean monthly water salinities at Collinsville. Judging from the salinity data for Collinsville, water salinity is probably not a major limiting factor for plants in the intertidal zone there. Except in unusual circumstances (such as the drought of 1976–77) the water in this area varies from essentially fresh to only slightly brackish. Because of the regular flushing action of the tides and the rapid runoff from riverbanks at low tides, soil-salt concentrations resulting from evaporation would not be expected to be significantly higher than the water salinity of the river. That soil salinities are not high in the intertidal zone of this area can be inferred from the absence of salt-tolerant plants such as Distichlisspicata and Frankenia grandifolia from the upper reaches of the intertidal zone.

Figure 1.

Mean monthly water salinities (in parts per thousand) of the

Sacramento River at Collinsville, California. The bottom line

averages monthly means over the period 1967–80. The top

line represents monthly means for 1977, the year with the

highest salinities on record (from USDI Bureau of

Reclamation, Tracy Field Division).

The major ecological factor influencing the distribution of plants in the intertidal zone of the study area is considered to be elevation with respect to tide levels. Tidal heights (in decimeters) at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (near the study area) are as follows (based on data in Simpson etal . 1968; definitions from Atwater etal . 1979):

10.1—mean higher high water (average height of the higher of the daily high tides);

–3.4—mean lower low water (average height of the lower of the daily low tides);

18.3—estimated maximum high water;

–7.6—estimated minimum low water.

Plants tolerant of relatively long periods of submergence (e.g., Scirpusacutus , S .

californicus , and Typha spp.) occupy lower sites along the river (below mean higher high water), whereas species less tolerant of long submergence (e.g., Carex barbarae , Hydrocotyleverticillata var. triradiata , and Lythrumcalifornicum ) occur at higher elevations in the intertidal zone (at or above mean higher high water).

A complete list of the vascular plants of the three plant communities considered in this study (tidal streambank, riparian woodland, and annual grassland) is found in Appendix A.

A tabulation of the flora of the three communities is given in table 1. The riparian woodland community contains the largest number of species (78) followed by the tidal streambank (49) and annual grassland (38) communities. The annual grassland community is included here primarily to illustrate the highly disturbed nature of the site. The low total number of species present (38) and the very high percentage of introduced species (82%) attests to its disturbed condition.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The riparian woodland community also supports a large non-native component (29 species). Over 30% of species are introduced plants, the majority of which also occur in the adjacent annual grassland community.

The tidal streambank community supports the smallest number of introduced species (8), only 16% of the total species. This figure compares favorably with the proportion of introduced species in the California flora as a whole, but is low compared to most California cismontane areas (table 2). Only the floras of Mount Diablo and Mount Hamilton Range have similar non-native components. The published floras of these two areas, however, are almost 40 years old; the percentages of introduced taxa present in both areas are almost certainly higher today.

| ||||||||||||||||||

The percentage of introduced species present in the tidal streambank community is especially low given the disturbed nature of the site. As previously indicated, this community has developed since the construction of levees between 1900 and 1940. The riparian woodland and annual grassland communities have also developed during this same time period. Their floras, however, exhibit a significantly higher percentage of introduced plant species. Annuals comprise a large percentage of the introduced species in the annual grassland (59%) and riparian woodland (42%) communities. An additional 32% of the introduced species of the annual grassland and 35% of those in the riparian woodland are perennial, non-rhizomatous herbs. Both of these life forms, especially the annuals, appear to be at a competitive disadvantage in the tidal streambank environment. Fifty-eight percent of the tidal streambank flora consists of rhizomatous herbs (fig. 2). Of the 29 species of rhizomatous herbs present in the tidal streambank community, only three (10%) are introduced.

It thus appears that the primary reason for the low number of introduced species in the tidal streambank community (relative to the other two communities) is the restricted capability of introduced plants (most of which are annuals or non-rhizomatous perennials) to establish under conditions of periodic or prolonged inundation. This fact is further emphasized by the relative paucity of introduced species in areas within the intertidal zone which have been more recently disturbed by riprapping. Although cover and density in riprapped areas are far lower than on undisturbed levees, the species which are found in these areas are predominantly native.

The life form spectra of the tidal streambank and riparian woodland plant communities (fig. 2) highlight several differences between these two communities. Almost 25% of the species present in riparian woodland are woody species, as opposed to 4% (2 species) of the total species found in the tidal streambank community. Twentyfive percent of the riparian woodland species are annuals—62% are introduced—while 14% (6 species) of the intertidal flora are annuals—43%

Figure 2.

Life form spectra of the tidal streambank and riparian woodland plant communities. Height of the bars corresonds to the percentage

of the total species in the community represented by each of the five life forms. A—annual; PH—perennial herb (including biennials);

RH—rhizomatous perennial herb (including herbs spreading by stolons and creeping root systems); S— shrub; and T—tree.

are introduced. The percentage contribution of perennial, non-rhizomatous herbs to the floras of both communities is almost identical, 24% for the tidal streambank community and 25% for the riparian woodland (the absolute species numbers are 10 and 21, respectively). Perhaps the most significant difference between these two communities is the much greater proportion of rhizomatous herbs in the flora of the tidal streambank plant community (58% of the total species compared with 28% for riparian woodland community).

Certain life forms enjoy an apparent competitive advantage in the tidal streambank community. Perennials account for 86% of the total flora, suggesting that one major limiting factor is the difficulty of seedling establishment under the ebb and flow of tidal waters. This would put annuals at a distinct disadvantage. The annual strategy may also be a handicap in another way: in an azonal community where water is not limiting, dry season dormancy is not only unnecessary but is probably detrimental. Rhizomatous species are more successful than non-rhizomatous species, a fact which may be at least partially explained by the greater ability of the former to apomictically spread once established. Even the two woody species present in the intertidal zone, Salix lasiolepis and the introduced Rubusdiscolor , are capable of extensive vegetative reproduction. Thus 63% of the tidal streambank flora is capable of vegetative reproduction.

In terms of floristic composition and life form spectra, the tidal streambank community in this rather disturbed area is remarkably similar to that of other, less disturbed areas in the Sacramento/San Joaquin estuary (compare the species list for Browns Island in Knight 1980). However, the plant cover and density of the tidal streambank community of the study area are certainly lower relative to less disturbed examples of this community elsewhere, although this fact is yet to be quantitatively documented.

Many of the species of the tidal streambank community (e.g., Typhalatifolia , Scirpusacutus ) have very wide distributions and occur in several types of moist to wet habitats. However, a few of the tidal streambank species in the study area exhibit restricted distributions and occupy only the intertidal habitat. Asterchilensis var. lentus and Lilaeopsis masonii are both recognized as rare and endangered by the California Native Plant Society (Smith etal . 1980). Both of these taxa and a third, Grindeliapaludosa , formerly considered rare and endangered, are entirely restricted to intertidal areas in the Sacramento/San Joaquin estuary. Although these plants are not particularly rare in the habitats in which they occur, their continued existence may be threatened by human alterations of their narrow habitats. The practice of riprapping streambanks results in a significant loss of habitat; potential increases in water salinity of the estuary as a result of

proposed future freshwater diversions may have deleterious effects on these plants.

Summary

The flora of the tidal streambank plant community along the lower Sacramento River near Collinsville is markedly different from the floras of adjacent riparian woodland and annual grassland communities. Non-native plant components of the latter two communities are significantly larger than that of the tidal streambank community, although all three communities have developed within the last 40 to 80 years. The proportion of introduced plants in the tidal streambank community is low even in areas more recently disturbed by riprapping. Introduced species, most of which are annuals or non-rhizomatous perennials, appear to be at a competitive disadvantage in the tidal streambank zone.

The life form spectra of tidal streambank and riparian woodland communities illustrate several significant differences between these two communities. Rhizomatous herbs are the most important life form of the tidal streambank community, apparently because of their facility to spread under conditions unfavorable to seedling establishment. Annuals are at a competitive disadvantage probably for the same reason, and also due to the handicap resulting from dry season dormancy in an azonal habitat where water is not limiting. In contrast, the riparian woodland community has a much lower proportion of rhizomatous herbs and higher percentages of annual and woody species.

In terms of floristic composition and life form spectra, the tidal streambank community that has developed in this disturbed area is similar to that of other, less disturbed areas. Three rare plant species occur in the intertidal zone of the study area, and are restricted in distribution to the intertidal zone of the Sacramento/San Joaquin estuary. Although not currently rare where they occur, they appear to be very narrowly adapted to this habitat. Additional human alterations of their habitat may threaten their continued existence.

Literature Cited

Atwater, B.F., S.G. Conard, J.N. Dowden, C.W. Hedel, R.L. MacDonald, and W. Savage. 1979. History, landforms, and vegetation of the estuary's marshes. p. 347–385. In : T.J. Conomos (ed.). San Francisco Bay: the urbanized estuary. Pacific Division, American Assoc. Adv. Sci., San Francisco, California.

Atwater, B.F., and C.W. Hedel. 1976. Distribution of seed plants with respect to tide levels and water salinity in the natural tidal marshes of the northern San Francisco Bay estuary, California. USDI Geological Survey Open File Report 76–389.

BioSystems Analysis, Inc. 1979. Potential for mitigation of salt marsh losses and associated adverse impacts on salt marsh harvest mice at the proposed Montezuma powerplant site. Unpublished report prepared for Pacific Gas and Electric Co. 51 p.

Bowerman, M.L. 1944. The flowering plants and ferns of Mount Diablo, California. 290 p. Gillick Press, Berkeley, California.

Ferren, W.R., Jr., and A.E. Schuyler. 1980. Intertidal vascular plants of river systems near Philadelphia. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sciences of Philadelphia 132:86–120.

Howell, J.T. 1970. Marin flora. Second edition with supplement. 366 p. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Howell, J.T. 1972. A statistical estimate of Munz' Supplement to a California Flora. Wasmann Journal of Biology 30:93–96.

Knight, W. 1980. The story of Browns Island. Four Seasons 6(1):3–10.

Mall, R.E. 1969. Soil-water salt relationships of waterfowl food plants in the Suisun Marsh of California. California Department of Fish and Game, Wildlife Bulletin No. 1. 59 p.

Mason, H.L. 1957. A flora of the marshes of California. 878 p. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Mueller-Dombois, D., and H. Ellenberg. 1974. Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. 547 p. Wiley and Sons, New York, New York.

Munz, P.A., and D.D. Keck. 1959. A California flora. 1681 p. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Robbins, W.W., M.K. Bellue, and W.S. Bell 1951. Weeds of California (1970 reprint). 547 p. Documents and Publications, State of California, Sacramento.

Sharsmith, H.K. 1945. Flora of the Mount Hamilton Range of California. Amer. Midl. Nat. 34:289–367.

Simpson Stratta and Associates, and K.H. Baruth. 1968. Suisun Soil Conservation District Master Plan Study II. Suisun Soil Conservation District, Dixon, California.

Smith, G.L., and A.M. Noldenke. 1960. A statistical report on A California Flora. Leaflets of Western Botany 9:117–123.

Smith, J.P. Jr., R.J. Cole, and J.O. Sawyer, Jr. 1980. Inventory of rare and endangered vascular plants of California (in collaboration with W.R. Powell). Special Publ. No. 1 (second edition). 115 p. California Native Plant Society, Berkeley.

Thomas, J.H. 1961. Flora of the Santa Cruz Mountains of California. 434 p. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sediment Control Criteria for an Urbanizing Area in San Diego County, California[1]

James S. Jenks, Thomas C. MacDonald, and James P. McGrath[2]

Abstract.—Studies were conducted to develop criteria and methodologies to mitigate the effects of urbanization on sedimentation processes at North City West in San Diego County. A sediment control plan was developed and adopted to mitigate these effects using on-site erosion controls and detention basins.

Introduction

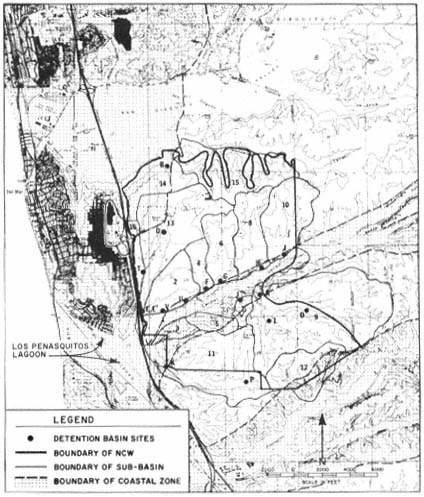

The urbanization of undeveloped land can cause many environmental, social, and legal problems, many of which are associated with changes in the hydrologic and sedimentation regimes of the area. The California Coastal Commission has been concerned with these problems in the coastal zone and, in the case of the Los Penasquitos Lagoon-North City West (NCW) area (San Diego County), has been instrumental in developing policies and solutions to urbanization problems. The following paragraphs present the background leading to these policies and solutions and describe the Los Penasquitos Lagoon and NCW areas.

Background

When the voters in California passed Proposition 20 in 1972, they established the Coastal Commission for the purpose of planning for the preservation of the coast of California for all the people of the state. The Commission made recommendations for long-term management of the coastline which are embodied in the California Coastal Plan. Recognizing that changes in coastal streams and wetlands are closely associated with changes in the watershed, the plan recommended that watershed management be required for coastal watersheds.

In 1976, when the Legislature established a permanent agency and body of legislation to carry out the goals of the Coastal Plan, it did not require watershed management plans, although Section 30231 of the Coastal Act did provide a general policy that runoff should be regulated and managed.

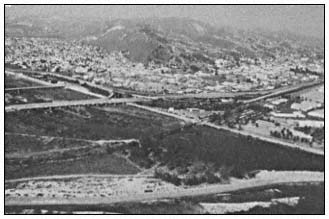

In the legislative mapping of the coastal zone, particularly in urbanizing areas, the coastal zone boundaries are generally too narrow to allow meaningful watershed management. However, there are exceptions to this in various areas along the coast. In Southern California, there are three major exceptions: the Santa Monica Mountains, where the coastal zone boundary included virtually the entire coastal watershed of the proposed national recreation area; the Aliso and Wood Canyon areas in southern Orange County, where the coastal zone included much of the proposed Laguna Greenbelt; and the Los Penasquitos Lagoon area in the northern part of the city of San Diego, where a significant portion of the watershed tributary to the lagoon is within the coastal zone.

The need for protecting the State-owned wetland was clearly evident in Los Penasquitos Lagoon. However, even there, political reality tempered the concept of watershed management. Only the floors and slopes of Carmel Valley, Penasquitos Canyon, and Lopez Canyon were included in the coastal zone. Carroll Canyon and much of the undeveloped area proposed to be developed in the city's NCW community were excluded. In exchange for this mapping of the coastal boundaries, the City of San Diego (and through its influence, the League of Cities), tempered its position on pending bills. In addition, the planning director pledged the city's cooperation in mitigating potential adverse effects of the highly controversial NCW development.

The Coastal Commission's experience in San Diego County under Proposition 20 had clearly revealed that urban development resulted in increased rates of sedimentation. The causes and mechanisms of these problems were less clear, so the Commission authorized a "special study" of the lagoon and watershed by a geologist/hydrologist. The resulting study, by Karen Prestegaard

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, Sept. 17–19, 1981].

[2] James S. Jenks and Thomas C. MacDonald are Principal Engineers with Leeds, Hill and Jewett, Inc., San Francisco, Calif. James P. McGrath is Coastal Analyst, California Coastal Commission, San Francisco, Calif.

provided some of the answers. The study recommended: 1) preservation of the natural areas of sediment storage (largely the undeveloped floodplains); and 2) mitigation of the increased storm flows associated with urbanization to prevent scour of sediment from the stream-beds and banks and increased downstream movement of sediment associated with such scour and increased flow.

The city of San Diego and local developers began further studies to implement these recommendations in the detailed planning of individual developments. The most successful effort was, ironically, in NCW. One of the major developers of the area authorized the detailed hydrologic analyses needed to carry out the recommendations of the Prestegaard study. The resulting study by Leeds, Hill and Jewett, Inc.[3] , was successful enough to be incorporated as an element of the city's Local Coastal Program (LCP).

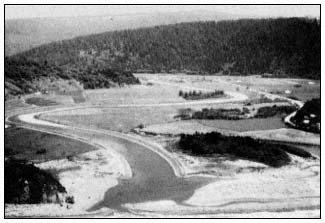

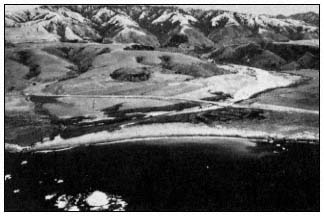

Los Penasquitos Lagoon

Los Penasquitos Lagoon is a coastal lagoon about 1.6 km. (1 mi.) long and 0.8 km. (0.5 mi.) wide, located in San Diego County. It consists of flat marshlands laced with deep tidal channels and interspersed with occasional tidal and salt flats (California Department Fish and Game 1974). The size of the lagoon is being slowly reduced by inflows of sediment from the Los Penasquitos watershed. Reports indicate that before 1888, the lagoon was continuously connected to the ocean. Railroad and highway construction through the lagoon in the 1920s drastically changed drainage patterns in the lagoon area and led to intermittent blockages of the mouth of the lagoon.

Removal of the beach and cobble littoral drift material that collects at the outlet of the lagoon to the ocean was first tried in 1966 to reestablish tidal flushing. It was believed that improved tidal flows would encourage the restoration of a healthy marine fauna to the lagoon. However, maintenance of the outlet to the ocean has been sporadic since 1966 and generally not successful.

One important factor involved in keeping the mouth of the lagoon clear is the volume of water which passes through the opening during one tide cycle. This volume is called the tidal prism. Accumulations of sediment in the lagoon reduce the tidal prism, which reduces the natural sediment-removing mechanism of the lagoon. It has been noted that in recent years there has been a net accumulation of sediment in the upstream areas of the lagoon.

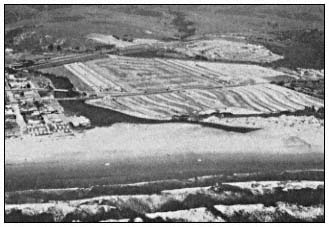

North City West

In 1975 the North City West Community plan[4] was prepared by the City of San Diego for a new community to be located near the north city limits. The boundaries of NCW encompass about 1,740 ha. (4,300 ac.), most of which are tributary to Los Penasquitos Lagoon. The community will consist of a variety of housing types, commercial developments, and public facilities, including recreational areas and open spaces. The areas associated with each type of development are presented in table 1.

The estimated total number of dwelling units planned for NCW is 13,970, sufficient to house a population of about 40,000. The community will have an employment center and town center. It will also have small commercial centers scattered throughout the area which will contain a variety of light industry, commercial establishments, and offices to serve the needs of future residents and to provide employment opportunities. Open space areas consist of parks, floodplains, areas of hazardous geology, and slopes greater than 25%. The NCW community will be developed by various developers and property owners.

As described in the Community Plan,[4] the NCW area will be developed as nine separate units. More than one of these units may be under development at any one time.

Technical Principles and Criteria for Sediment Control

Technical Principles

Development of NCW will have significant impacts on the sedimentation regime of the area which, if not regulated, could increase the rate of sediment accumulation in Los Penasquitos Lagoon.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[3] Leeds, Hill and Jewett, Inc. 1980. North City West drainage study. Report to Pardee Construction Company, San Francisco, Calif. 44 p.

[4] City of San Diego, 1975. North City West Community Plan. 147 p. San Diego, Calif.

Currently most of the NCW area is undeveloped, with the predominant vegetative cover being annual grasses and open brush. Some of the land is used for agricultural and grazing purposes. Soils in the area are fine-grained and cohesionless and are predominately in hydrologic soil group D, which has a very low infiltration rate. This soil-type, along with the minimal vegetative cover and, in some areas, overgrazing, makes the area subject to the erosive forces of rainfall and runoff. This situation is aggravated by point discharges into the unprotected drainage channels in the western part of NCW of urban runoff from areas on the west side of Interstate Highway 5. During the recent wet years, these point discharges have, in at least one place, eroded a huge gully and transported several thousand cubic yards of sediment downstream, some of which has been deposited in the lagoon.

When NCW is developed, the potential for sediment runoff will initially increase when vegetative cover, which tends to hold the soil in place, is removed by grading operations. Sediment runoff during this period must be controlled to avoid clogging the downstream channels and lagoon with sediment.

After NCW is developed, sediment production from the area will be less than currently occurs. Sediment production will decrease as a result of open space and developed areas being protected by roof tops, streets, lawns, and other erosionresistant groundcovers.

Also after development, rainfall over much of the area will be collected in non-erosive roadbeds, gutters, and storm drains and conveyed to the stream channels, thereby avoiding concentrated flows over sediment-producing areas. Other sediment control devices in NCW, such as berms, downdrains, etc., will protect against local sedimentation damages to other portions of the development.

Although sediment production from NCW will be less after the area is developed and the vegetation is well established, the amount and rate of runoff will increase. The amount of runoff will increase because there will be less infiltration loss in the impervious areas of the development. The rate of runoff will increase because runoff will be collected and conveyed to the downstream channels in a more rapid manner than occurs naturally. Because of this more rapid drainage, runoff from larger areas during the most intense periods of precipitation will be more nearly simultaneous than normal.

The increased volumes and rates of rainfallrunoff and the reduced amount of sediment production after NCW is developed will, if not controlled, have long-term effects on the sediment regime of channels downstream from the development. The increased rates and volumes of runoff will have a greater capacity to transport sediment than the flows that now occur and the watershed will not supply as much sediment to the flows. Thus, if drainage controls are not provided, erosion of the bed and banks of stream channels can be expected downstream of points where runoff is discharged from NCW.

From the foregoing, it is apparent that both short-term and long-term drainage control plans are needed for NCW to protect against sediment damages to downstream areas.

Drainage Control Criteria

During the construction period, the most effective control plan for a proposed development is to provide on-site controls to reduce the amount of sediment that would otherwise run off the construction slopes. Such controls include vegetating bare slopes, constructing low berms and drains, and other short-term measures.

Reduction of sediment erosion by means of protecting land surfaces can effectively eliminate sediment runoff from many areas. However, it may not be possible to protect all areas or the protection used may not be completely effective at all times. In these cases, it will be necessary to provide additional backup controls. These backup controls have the function of collecting the sediment that does run off before it can cause any downstream damage.

For the long-term, drainage control facilities must be provided that regulate outflows from the development such that the ability of the outflow to erode sediment from the downstream channels is reduced. For a constant rate of flow, the amount of sediment that can be transported is directly proportional to the duration or the volume of flow. However, in most cases it is not practical to try to reduce the volume of stormwater runoff. The sediment transport capacity of the flow increases disproportionately faster than increasing flow rate. Thus, to protect against erosion of downstream channels, it is more important to regulate the rate of runoff.

It is also important that the facilities that provide the long-term control of sedimentation problems allow passage of sediment from the developed watershed. Sediment from the developed watershed will satisfy part of the sediment transport capacity of the downstream flows. To the extent that outflows from an area contain less sediment than the flow's capacity to transport sediment, the flow will try to make up the sediment deficiency by eroding the bed and banks of the downstream channel. Thus, it is important that sediment runoff from the watershed pass through the control facilities and into the downstream channels.

In implementing the recommendation that increased storm flows be mitigated, a number of difficult technical issues had to be resolved. First, the design storm event to be the basis of analyses needed to be selected. Second, methods for estimating and comparing runoff had to be established.

The field work done for the Prestegaard study indicated that the storm event with a recurrence interval of from one to two years did not appear to be the channel-forming event for this Mediterranean-type climate. Also, five-year storm flows are not substantially greater than the two-year flows. However, storms in 1978 and 1979–80 had an approximate 10-year recurrence frequency and indicated that significant channelforming processes do occur with such storms. Thus, the 10-year storm was selected as the design storm of the analyses. Subsequent analyses showed that the controls developed to regulate runoff from a 10-year event also effectively attenuated runoff from the 25-year storm event—further strengthening arguments for use of the 10-year storm as an analytical base.

The "Rational Formula" for estimating rainfall-runoff is commonly used for subdivision drainage design in the county. This formula estimates the peak rate of rainfall-runoff as the product of the watershed area, rainfall intensity, and an empirical rainfall-runoff coefficient. In general this formula tends to overestimate flow rates. If controls are to be provided to regulate flow rates to natural levels for the purpose of sediment control, that purpose may be defeated by analytical tools that overestimate flow rates. An overestimation of flows from undeveloped lands, if used as a criterion for design of control facilities, would lead to a strategy that did not sufficiently attenuate flows in the developed condition—and thus, failure of the mitigation strategy.

A methodology was developed by Leeds, Hill and Jewett, Inc., for analyzing rainfall-runoff from the 1,740± ha. (4,300± ac.) of land tributary to Los Penasquitos Lagoon to be occupied by NCW. This methodology, which utilizes the US Army Corps of Engineers (CE) HEC-1 computer program, provides accurate estimates of runoff hydrographs from relatively small drainage areas for both developed and undeveloped land-use conditions. The methodology and its verification are described below.

North City West Sediment Control Plan

Methodology

Several methods to control stormwater runoff from developed areas were investigated, and detention basins were found to be the most effective. These detention basins can also be used, on a temporary basis, to protect against potential erosion during construction when slopes will be bare.

Preparation of an effective drainage control plan utilizing detention basins requires determination of stormwater runoff characteristics for existing and future land-use conditions. Estimates of peak runoff under existing conditions are needed to establish the level of regulation that should be provided. Estimates of increases in runoff under future developed conditions are needed to locate and determine the size of detention basin facilities that would regulate future flows to less than those that would occur under existing conditions.

The CE's HEC-1 computer program was used to analyze stormwater runoff. This program is capable of generating estimated runoff hydrographs from precipitation using very small time intervals in the hydrograph calculation. Because the drainage areas used in the analyses are generally small, and therefore have short times of concentration, a method of analysis that uses even smaller time intervals in the hydrograph calculation is necessary to accurately estimate peak discharges. The HEC-1 program provides a cost-effective method of obtaining these estimates.

The HEC-1 program estimates the amount and rate of rainfall-runoff based on the drainage area size, land use, types of soils, intensity of precipitation, and antecedent moisture conditions. These characteristics can be estimated from soil, groundcover, and topographic maps, photographs of the study area, and information gathered during field inspections. Precipitation intensities and antecedent moisture conditions can usually be obtained from local agencies.

During the initial construction period detention basins can be fitted with a temporary riser so that they function as both sediment traps and as detention basins. Once development is complete and slopes are stabilized by vegetation, the temporary riser can be removed. After the riser is removed, the basin outlet would be at the low point of the basin floor such that much of the subsequent inflow of sediment can pass through the basin and into the downstream channel. As previously noted, allowing sediment to pass through the basin will minimize the tendency of the downstream channel to degrade due to a reduction of sediment inflow. Temporary desilting basins can be provided to protect those areas that do not have a downstream detention basin. Use of both desilting basins and modified detention basins during the construction period is considered a backup to the primary on-site controls of vegetation and avoidance of grading during the runoff season.

Verification

The reliability of the methodology used to estimate runoff characteristics of developed and undeveloped areas was verified by calculating runoff from the drainage areas of Pomerado and Beeler creeks, for which actual precipitation and runoff data are available, and by comparing the measured and calculated runoff hydrographs. These creeks are tributary to Los Penasquitos Lagoon and are about 8 km. (5 mi.) east of the NCW area. Stream gauge measurements on these two creeks are available for a short period of record, so the choice of past storms that can be studied is limited.

A storm which occurred on 4 December 1972, was selected for verification. This was an isolated storm which produced fairly uniform and equal amounts of rainfall over both drainage areas. The drainage areas were divided into urbanized and nonurbanized subareas. The Pomerado Creek area is 10.6 sq. km. (4.1 sq. mi.) in size, of which about 15% is urbanized by medium-density residential housing. About 1.6 km. (1 mi.) of the creek channel is concrete-lined. Beeler Creek drainage area is 14.2 sq. km. (5.5 sq. mi.) in size and, except for a very small development, not urbanized.

The measured precipitation data from nearby rain gauging stations along with hydrologic characteristics of the subareas, estimated from soil and topographic maps and aerial photographs, were used in the HEC-1 computer program. The runoff hydrographs from each of the subareas were calculated, routed through the stream channels, and then combined to obtain the total runoff hydrograph from the drainage areas of the two creeks. These hydrographs were then compared with measured flow rates as shown in figure 1. This comparison indicates that the methodology produced reasonable estimates of runoff from Pomerado and Beeler Creek drainage areas and can be used to produce reasonable estimates of runoff for both urbanized and undeveloped areas.

Figure 1.

Calculated and measured discharge for December 4, 1972 storm.

North City West Analyses

Following verification of the methodology, hydrologic characteristics of each drainage subarea in NCW (fig. 2) were determined and are presented in table 2. Future conditions were estimated using the NCW Community Plan.[4]

Precipitation intensities having recurrence frequencies of 10 and 25 years were used in the analyses for sizing detention basins and analyzing their performance. Peak rates of discharge were computed at the potential basin sites shown in figure 2 for existing and ultimate land-use conditions for the two storm events. These peak discharge rates are presented in table 3 for selected locations.

Alternative basin locations, sizes, and outlet works were then examined to develop a plan which would meet Coastal Commission requirements. It was found that a minimum of three detention basins are needed to meet the requirements but that several alternative combinations of basin locations could be used. Regulated peak outflow rates for one of the alternative plans are presented in table 3.

Hydrographs of stormwater runoff for the 10-year storm under existing and ultimate land-use conditions with and without detention basins are shown in figure 3 for the location where Carmel Creek flows into Los Penasquitos Lagoon. The peak discharge at this location is 554 cubic feet per second (cfs) under existing conditions, 917 cfs under future conditions without detention basins, and 539 cfs with detention basins for the alternative plan that provides detention basins at locations E, R, and H.

In addition to providing for regulation of stormwater runoff under ultimate land-use conditions, the plan requires on-site controls during the interim construction period. These controls provide that no grading be done during the fivemonth period from October 5 to March 15 of each year. It further provides for planting of exposed construction slopes before November 1 of each year to minimize erosion during the rainy winter season. Although this program should be adequate, the plan also provides backup controls by fitting the detention basins with risers during the interim construction period so that they can act as sediment traps.

Figure 2.

North City West drainage areas and detention basin sites.

Figure 3.

Discharges from NCW in Carmel Creek at

Los Penasquitos Lagoon-10-year storm.

Conclusion

The concept of watershed management through stormwater management used in NCW poses great potential for urbanized areas where development goals include minimizing increases in downstream flooding, preserving natural riparian corridors, and/or controlling sediment movement. Although the side canyons of the watershed will be substantially altered through urbanization, the main stem of the stream will be preserved and managed in a state similar to its natural condition. Thus, sediment transport capabilities of the channel will be maintained, although sediment production from the watershed will decrease somewhat after development activities are completed.