PART FIVE—

TECHNOLOGIES

The changing technologies of film production and of film/video screening have been the subject of a number of Film Quarterly articles over the years. The topics treated in these pieces are necessarily of interest to the "mad keen" film lovers who read Film Quarterly . The art to which they devote so much of their time is almost constantly changing, both in the mode of its production and in the systems of delivery that convey it. Change occasions queries, not unmixed with anxiety, in any devotee. Will a changed cinema still love us? Will we still love it?

Charles Shiro Tashiro's article on videophilia is unusually well informed. A graduate of the UCLA film production program, he was at the time of writing a Ph.D. student in Critical Studies at the University of Southern California. Moreover, as a former producer for the Criterion Collection of videodiscs, including their edition of Lawrence of Arabia , Tashiro understands the technologies involved first-hand. He concedes the usefulness of home systems for the close study of films, but notes that "this apparent windfall has usually been embraced with little attention to the technical issues raised by the movement of a text from one medium to another or to the consequences of film evaluation based on video copies."

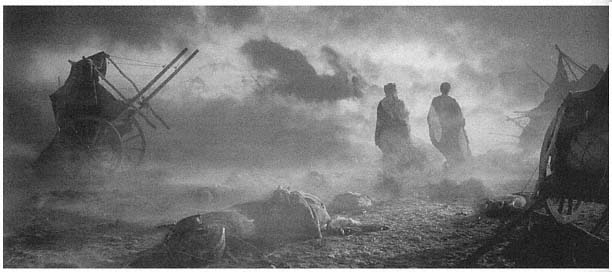

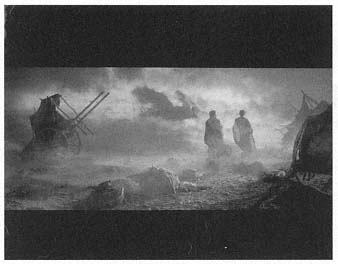

To enhance this argument, Tashiro provided Film Quarterly with stills of three formats of Lawrence: scanned, letterbox, and full film frame. The contrast between the second and the third is revealing because the depth evident in the full film frame is almost completely absent in the letterbox version. The value that Charles Barr saw in CinemaScope—a greater sense of depth than the conventional frame—is in fact negated by video or laserdisc letterboxing, which refocuses attention on the flatness of the image and hence accentuates the composition rather than, as Barr argued, effacing it.

The pieces by Charles Eidsvik and Jean-Pierre Geuens concern what Eidsvik calls "changes in film technology in the age of video." Eidsvik's exceptionally clear-eyed view is that "there is very little that is esthetically revolutionary in

the new technologies, and nothing that would upset the basic film-making power structure. Changes have been conservative, a defense against inroads and threats brought by very rapidly evolving video technologies." Within this framework, Eidsvik discusses new improved film stocks, including high-speed ones, which, supplemented by six emulsions and also by advances in postproduction sound enhancements, make possible low light-level filming and, indeed, night-for-night filming. Eidsvik argues that, oddly, these changes have not affected film style. Venturing into narrative theory, however, he suggests that they may have "a discernible effect" on story and plot construction, because they allow "freer use of the kinds of settings that can be easily shown," rather than left as gaps. This is a stimulating suggestion, but later he notes more cautiously that the developments he has discussed have made "story construction a bit different in potential." Indeed, one of the conclusions of the piece is that "large theoretical claims must be put on hold," to which Eidsvik adds, very sensibly, that theory "must limit itself to a little bit of history at a time." The developments that Geuens elaborates in such elegant detail and cultural depth were anticipated by Eidsvik:

The most obtrusive technical change outside of the area of special effects in the last decade has been in camera movement. The Steadicam, Louma-type crane, Camrail, and jibbed dolly systems that have allowed us our current period-style of perpetually moving cameras are all consequences of fitting video viewfinders to film cameras, thus making them remote-controllable.

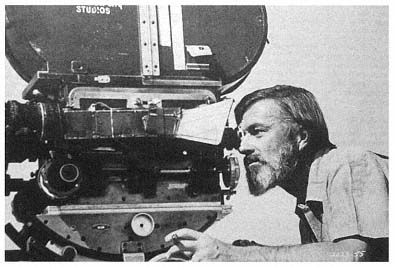

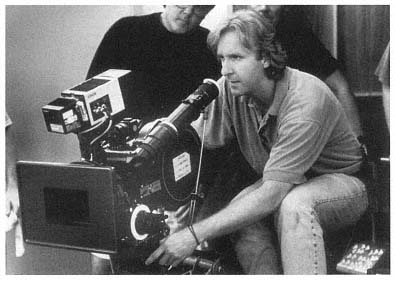

Geuens's article on the video assist begins with a discussion of Martin Heidegger on technology and proceeds to quote the techno-perspectives of Andrew Feenberg and Herbert Marcuse as well. He traces the prehistory of movie camera viewfinders up until 1936, when the Arnold and Richter Company of Germany introduced continuous reflex viewing with its new Arriflex 35mm camera. He also discusses Peeping Tom (1960); Vivian Sobchack; Gilles Deleuze; independent filmmakers, including Direct Cinema practitioners, who direct and photograph their own films; Heidegger again; and Emmanuel Levinas. He then surveys the history of the use of video to support film production, which culminates in the introduction of video assist. As in Geuens's earlier article on the Steadicam, it is only after carefully building theoretical and historical contexts that he allows himself some doubt. Video assist would not have benefited Ingmar Bergman very much, but the films of James Cameron or Robert Zemeckis would have made little sense without it. In their films, "the device itself is no more than an advanced representative" of the other technologies that will be introduced in postproduction. Toward

the end of the video assist piece, Geuens quotes with approval Eidsvik's account of new technologies as the industry's "defensive maneuvers" with regard to video technologies.

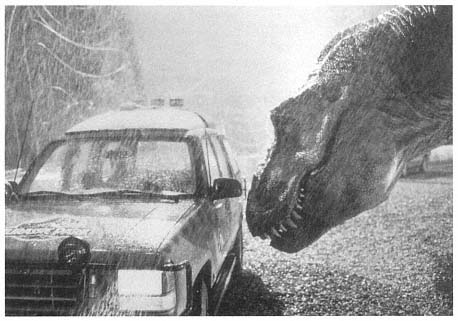

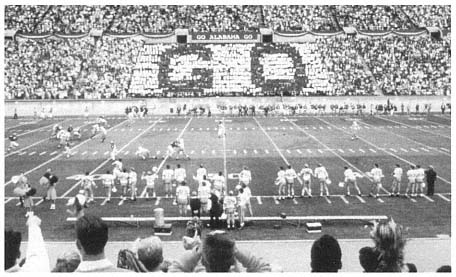

Stephen Prince's article contains a wealth of information about another important new technology: digital imaging or, as it is called in the industry, computer-generated imagery (CGI). Prince conducted telephone interviews with a number of practitioners in the field, research that adds significantly to the value and detail of his discussions. He distinguishes between films in which the conspicuous use of digital processes makes them evident to viewers—True Lies, Jurassic Park , and Forrest Gump —and others that use digital processes of which the viewer is unaware. In both categories, however, the ability of CGI to simulate movement, location, lighting, and other features creates the perceptual patterns of photographically realistic cinema.

Unlike the writers of the articles discussed above, Prince is not critical of the new technologies he discusses, either for their role in the cinema-video competitions or for their other functions in the media industry and in the national and global economies. He turns his research in a different direction—toward film theory and toward overcoming what has been called by some a realist versus formalist opposition in film theory. Given that the line between real and not real will be increasingly blurred, Prince asks, "How should we understand digital imaging in theory? How should we build theory around it?" His answer, developed at length and cogently, is what he calls a correspondence-based model of cinematic representation: film shares many of the perceptual codes that structure our everyday perception. Although CGI by definition has different origins than photographic-based imagery, the two equally correspond to our normal perception, and hence are both experienced as perceptually realistic.

Michael Dempsey's two-page manifesto against colorization is the classic statement on this galling issue. It is also classical in that one could analyze its superb rhetoric as one does a Cicero oration. He begins on a moment of rest after exhausting conflicts: "Whatever gamuts American movies have had to run during production, once made they are supposed to be secure." Studio interference, the hobbling of censorship, and other compromises impede the making of films; but there are also postrelease hazards such as pan-and-scan prints, the fading of color prints, and, most serious of all, the colorization of black-and-white films by those who own them. These include Ted Turner, who owns the MGM film library; the Hal Roach Company; and Color Systems Technology—all of whom "produce new prints of black-and-white movies with color added." (As in Cicero, the perpetrators of scandalous behavior are named.) After answering the arguments of the colorizers such as that the makers of black-and-white films

could not afford color, Dempsey lists the agencies and individuals that are working to preserve black-and-white films.

Dempsey argues that the colorizers are motivated by greed and concludes, "But talking to the colorizers about things like moods of elation and reconciliation is pointless." Here the writer doubts the power of his words and arguments to have any effect on those responsible for damaging the nation's film heritage. This is known in classical rhetoric as an aporia, a point in an oration or brief in which the writer questions how to continue. This doubt itself can be used against the writer's opponents and may also reorient the argument as a whole. Thus the failure of words or arguments to have any effect upon the colorizers is at the same time his most damning indictment of them. Since money is all they understand, moreover, the writer urges his readers not to screen or broadcast colorized films: don't buy them, rent them, or watch them.

Colorization

Michael Dempsey

Vol. 40, no. 2 (Winter 1986-87): 2–3.

Whatever gamuts American movies have had to run during production, once made they are supposed to be secure. This, naturally, has not been the case. Circulating prints of Chaplin, Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy silent comedies have been corrupted with cutesy, moronic noises. TV stations concoct pan-and-scan prints of wide-screen films, destroying their compositions. Color negatives of the past three decades are subject to fading.

Now our film heritage has a new nemesis: "colorization." Using computers, such entrepreneurs as Ted Turner (who now owns the MGM film library, which he bought as fodder for his Atlanta "super station"), the Hal Roach Company, and Color Systems Technology produce new prints of black-and-white movies with color added.

Various rationales have been advanced for this disgusting cultural vandalism: black-and-white films can't draw huge TV audiences; many video store customers turn up their noses at them; "the kids" aren't interested. Shrugging "philosophically," some apologists point out that the original black-and-white negatives remain untouched. Others would protect the "classics" (these sensitive souls know all the classics intimately, of course) but let the colorizers have, say, Republic Pictures potboiler Westerns or Abbott and Costello comedies. Besides, one defense of colorization runs, most American studio pictures were shot in black-and-white only because color was too expensive. The clear implication is that black-and-white is a primitive form of cinematography which "lacks" color, and now these technocrat/hustlers will correct that deficiency. One of them, Earl Glick, the board chairman of Hal Roach Studios, has even had the gall to state that his colorizers have improved Joseph Walker and Joseph Biroc's black-and-white work on It's a Wonderful Life .

Color may have been too costly for most American studio movies during the 1930s and 1940s, but once black-and-white photography was chosen, the movies were designed, costumed, and lit accordingly. However, even bothering to refute arguments like these grants them undeserved dignity when in fact

they are just contemptuous coverups for the one and only motive behind this rush to colorization: raw greed.

And a rush it is. Already, colorized cassettes of, for example, Yankee Doodle Dandy, The Maltese Falcon, Topper , and It's a Wonderful Life are not only flooding video stores, they are also inexorably driving the black-and-white originals into the ghettos of occasional museum or revival theater screenings in cities where such forums exist. If this situation is not reversed, no American black-and-white motion picture may ever again live in regular showings as its makers intended.

Defenders of black-and-white movies are not sitting idle. The Directors Guild has decried colorization on artistic and cultural grounds and has gone to court over the issue of copyright infringement. RKO has done the same in an effort to protect the films produced under its own name. Numerous directors, among them Billy Wilder, John Huston, Fred Zinnemann, Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, Bertrand Tavernier, Nicholas Meyer, Peter Hyams, Martha Coolidge, and Frank Capra, have expressed outrage. James Stewart has eloquently described the grief he felt when he tried and failed to watch a colorized print of It's a Wonderful Life to the end. Having seen a colorized effigy of this movie's climax, I can testify that if this is how the picture is going to be presented from now on, then It's a Wonderful Life , in effect, no longer exists; the added color annihilates the mood of elation and reconciliation that Frank Capra and his collaborators originally sought and achieved.

But talking to the colorizers about things like moods of elation and reconciliation is pointless. Whether you are an individual viewer or a more influential person (say, a buyer or a programmer for television), the urgent message is the same: don't screen or broadcast colorized films, don't rent them, don't buy them, don't watch them. We are dealing with people who are unreachable by cultural, artistic, or social appeals because they don't care about anything except money. Therefore, let us hurt them in the way most painful to their shriveled sensibilities, by depriving them of every dollar that we can. If we do not, their bottomless avarice will deprive us and future generations of infinitely more.

[The above views are passionately endorsed by the Film Quarterly editorial board.]

Machines of the Invisible:

Changes in Film Technology in the Age of Video

Charles Eidsvik

Vol. 42, no. 2 (Winter 1988–89): 18–23.

Until the early 1970s, critical discussion of film technology and practice was a preserve monopolized by film-makers and by theorists such as André Bazin and Jean Mitry who were in close contact with film-making communities and often served as intellectual spokesmen for views commonly held by film-makers. The film-making community, in trade journals such as American Cinematographer and J.S.M.P.T.E ., traded secrets, discussed craft, and celebrated its lore, myths, and mystique. Theorists and historians such as Bazin and Mitry—Mitry was himself a film-maker—built film-makers' perspectives into their views of how new technology catalyzes change in film history. This view, which permeates Mitry's Esthétique et psychologie du cinéma and can also be found in essays such as "The Myth of Total Cinema" by Bazin, posits an "Idealist" and "technologically determinist" view of history, with film technology allowing film-makers ever greater potential for recreating reality.[1] Though technological determinism is an understandable belief among film-makers, whose jobs depend on machines and for whom belief in technological determinism is anxiety-lessening, the position is hardly intellectually respectable.[2] Once Althusserian Marxism began to explore relationships between ideology and technology, an attack on Idealist and technologically determinist positions was inevitable. The attack, led by Jean-Louis Comolli, J.-L. Baudry, and Stephen Heath, attempted to critique technology within a "materialist" approach to cinema. Soon joined by feminist film critics such as Teresa de Lauretis, the analysis of technology and ideology has become a mainstream approach to technology at least within academe.

Though the academics (and Comolli himself) are prone to gaffes when discussing specific technological practice,[3] one cannot quarrel with their intentions or intelligence. Nevertheless, insofar as the job of historians is to account for change, their approach has little future, not because their methods—the search, for example, for codes to which technology speaks—are weak, but because they have chosen to write and work from the "position of the spectator," from what can be seen and heard on movie screens, rather than on

"tainted" film-maker-generated technical histories.[4] This would be fine except for a simple problem. Not only do most movies, in George Lellis's terms, "seek to hide the methods by which they produce their illusions,"[5] new production practices often are deliberately made invisible and inaudible to film spectators. Information on new technical practices is only briefly hinted at in trade journals but primarily is passed on through actual film-making.

If the last decade is any indication of how change occurs in cinema, a lot goes on below the realm of the easily perceivable. The central fact of recent cinema is the film industry's attempt to survive in the face of overwhelming competition from video. Film can compete with video only as a producing and large-screen exhibition medium. As a producing medium it can compete only on the basis of "quality," with quality defined as something film is not trying to achieve but already has . Technological innovation has largely served the purpose of making that quality either "better" or easier to achieve, but not different basically from the quality that already exists. New technology thus has expanded what can be filmed but not (deliberately at any rate) how we are meant to see films. Except in the area of special effects, an area in which mainstream film-makers have been able to use the old Hollywood ploy of turning big budgets and technical prowess into a publicity stunt, conceptually conservative technological innovation has been the norm. In understanding this innovation, perhaps the only relevant theorist would be Michel Foucault, whose approach to power struggles is relevant to just about any study of technical change.[6]

But the power struggle has been basically defensive. In the last decade, the majority of technical developments in the film industry have been aimed at facilitating extant production practices rather than at changing the "look" or sound of commercial films. Just about every new product has been advertised as something that makes film-making cheaper and easier, usually by allowing smaller crews or less schlepping of equipment on location. For each problem to be solved—light levels needed for shooting, the problem of equipment weight, problems of camera mobility, or the difficulty of getting good sound on location—different companies have offered competing solutions. For low-light filming, for example, Kodak, Fuji, and Agfa have offered faster film stocks; Zeiss, Angenieux, Cooke, and Panavision have offered faster, sharper lenses; and various makers of lighting equipment have developed lights and light-control equipment that require little electricity and are highly portable. Alone, each new technology has had little effect. But in aggregate, the dozens of new technical possibilities made available have radically altered the construction and implied worlds of commercial narrative films. In terms of David Bordwell's "style-syuzhet-fabula" triad,[7] the technical developments have had surprisingly little effect on style, but a discernible effect on syuzhet (plot) construction. This has occurred because the new technologies allow more on-location film-making

control, and thus freer use of the kinds of settings that can easily be shown, rather than left as syuzhet gaps, in fiction films. I will return to this issue later, after a review of the major recent changes in film technology.

How film-makers get images has been directly affected by changes in film-stock technology, lenses, and cameras meant for location use. But the primary change in visuals has been indirectly created through Automated Dialogue Replacement (ADR) in postproduction. ADR masks its own existence so well that it is not audibly detectable to a film viewer. It has been radically liberating as a catalyst for other shifts in technical practice.[8]

The most important of the visual-technology shifts has been in an expected area, film-stock technology.[9] Until the mid-1970s Eastman's 5254/7254 negative was standard for narratives; when the new 5247/7247 stock came in, films changed visually and film-making got easier: the stock had such fine grain and wide exposure latitude (7 to 10 stops of light acceptance) that it became a new standard, one still more or less prevalent. Since then Eastman, in addition to unpublicized refinements of 5247, has produced three generations of high-speed stock, a fine-grained and contrastier replacement for 7247 in 16mm (7291), a daylight-balanced version of 5247 for use with the new high-efficiency "metalhalide" arc lamps known as "HMIs," and a stock designed purely for matte work in special effects film-making. Though the newest high-speed stocks have six-layer emulsions[10] and flattened-molecule technology (which combine to allow high-speed film-making without visible grain), each stock intercuts smoothly with the basic "47." The new high-speed stocks are rated at ASA 320 (compared to 47's ASA 100) and can be rated faster, even without extended lab development ("pushing"). For example, Full Metal Jacket was shot with the film rated at ASA 800.[11] To the viewer, almost nothing has changed in a decade. But because of the increase in film speed without increase in grain, now very low-light scenes can be filmed easily; because of compatible tone and grain-structure architecture, interiors and even night exteriors are similar in "look." Eastman, Fuji, and Agfa stocks can coexist as stylistic variants even within a single film without a viewer noticing.[12] The effect has been on the kinds of shots that can be incorporated into narratives smoothly. Night-for-night filming is now relatively easy, provided the new "superspeed" lenses are used.

Low-light filming problems also were "solved" by lens and lighting manufacturers unobtrusively. Quicker and sharper zoom and prime lenses enhance the possibilities of fast stock without introducing their own "look." Where it used to take 100 footcandles of light to get sharp images a decade ago (because older lenses were only really sharp stopped down) now 25 footcandles or even 10 is common. (In Eastman's demonstration film for film-to-video transfer techniques, one romantic candle-lit scene is lit with only one ordinary candle; it looks fine.) Not only is frying no longer an occupational hazard for actors;

syuzhet construction now has very few light limitations. And because lighting problems in narrative film-making are in good part problems in schlepping lights and light-control equipment, and in getting juice to the lights, more efficient units such as HMIs have become popular. (An HMI is around five times as efficient as a tungsten lamp, twice as efficient as a carbon arc, and is day-light-temperature.) Quicker lighting set-ups with less generated heat and smaller electricity requirements expand location possibilities.

The additional location flexibility made possible by new visual tools made location work cheaper and easier; it also made story construction a bit different in potential. More low-light locations could be used, and they could be used in new ways. The city night locations of a Desperately Seeking Susan or After Hours were predicated on the new tools and stocks. Certainly night exteriors are not new; the ease with which they can be put into films is.

Complementing and accelerating the changes brought by stocks, lenses, and lights are post-production sound developments. ADR, based on "insert" electronic technology (which "ramps" the onset of the bias tone so that sounds can be inserted in a track without pops or other recording artifacts), makes it possible to clean up location sound tracks or unobtrusively to replace location sound entirely in post-production. Now so ubiquitous that almost every feature film lists ADR credits, the art of sound replacement and remixing is an unsung but central contemporary film- and video-making craft. But except for the remarkable intelligibility of dialogue made possible by ADR and new versions of sound tools such as radio microphones, the main effect of new sound technology has been to free up crews on location. No longer is a take spoiled by bad sound; no longer need a boom shadow be in the way; no longer must the sound of a moving camera be so carefully masked. But the use or non-use of ADR in a scene is undetectable.

Curiously, a by-product of ADR has been in characterization and acting styles. Actors such as Robert DeNiro now often just mumble their lines on-location, and depend on ADR sessions to get the right intonation and subtextual subtlety into the final film.[13] Before ADR, Europeans (such as Bergman) frequently "matched" dialogue either because of bad recording conditions or to re-do performance nuances;[14] with ADR this technique has become common, even everyday. Actors who do not have to project their voices can present different aspects of character than those who must be heard clearly by location microphones. Potentially this could cause large shifts in story and character construction. But the trick to the technique working is for the actor and film-maker not to get caught by viewers. Acting styles have changed since ADR. But only those within the industry know how or why.

The cameras used to shoot also have changed, and similarly, it is impossible to tell what camera has been used in any recent normal-format film. Which of the

four generations of Arri 35BL or two generations of Moviecam or myriad generations of Panavision/Panaflex cameras a film was shot with is in no way visible. (Similarly it is impossible to tell what camera recent 16mm films were shot on.) Each generation in each manufacturer's line has become quieter, more reliable, more adaptable to video viewfinders, and more versatile, particularly for location filming, but no recent camera has advertised its existence to the viewer.

The most obtrusive technical change outside of the area of special effects in the last decade has been in camera movement. The Steadicam, Louma-type crane, Camrail, and jibbed dolly systems that have allowed us our current period-style of perpetually moving cameras are all consequences of fitting video viewfinders to film cameras, thus making them remote-controllable. The earliest uses of these tools were obtrusive: in Bound for Glory when the camera glided through a crowd smoothly and in ways not conceivable with a boom or dolly, the effect was startling; so was the camera smoothness in An Unmarried Woman when the camera went up flights of stairs with the actors; so were the hallway and maze and stairs moving-camera scenes in The Shining . But the Steadicam has become just part of current film technique, and the different devices for moving a camera by remote control are used in films almost interchangeably, usually without calling attention to themselves. The basic principle behind all the devices is that a camera can be moved more freely if its 50-lb. weight can be separated from the weight of the operator and focus-puller. Remote control and videotapes solve the problem: in the Steadicam by physically isolating the camera from the "handholding" operator; in the Louma and jib-based rigs by putting the controls at a console and locating the camera at the end of some sort of boom, with mechanical, hydraulic, or electronic servocontrol systems that allow manipulation of all camera controls.

Are developments in moving-camera technology revolutionary? They seemed so in the 1970s; now the situation is less clear. As the mobile camera became more common, the stylization apparent in a film such as The Shining has blended into a repertory of mobile-camera/stationary-camera paradigms. But these paradigms are not so much the consequence of technologically created opportunity as of an economics- and video-driven loss of other esthetic options. A decade ago, a film-maker could use the edges of the frame as part of compositional graphics—to lead the eye, to counterbalance other visual elements. But now cable and video distribution is the financial heart of the media storytelling business, so film-makers have to keep essential information away from the edges of the screen, and have to forget about using the graphic potentials of 2.3:1, 1.85:1 or 1.65:1 frame formats. All films must be composed for what the Europeans call "amphibious" life, for viewability both on theater and on television screens. Without control of the shape or edge of frames, visual control must be done kinetically—especially because TV screens do not carry enough visual information for long-held static shots to retain viewer attention. Glance Esthetics, our contemporary period-style,

has almost completely replaced Gaze Esthetics, in which film-makers left time for the viewer to contemplate the mise-en-scène . Glance Esthetics (perhaps seen in purest form on music videos) requires the moving camera. But it seems far less than obvious how one might analyze stylistic changes forced by economic changes that themselves reflected new technologies and broader-scale power struggles within society. And the longer the new camera-moving technologies are with us, the less radical they seem—the more they seem mere successors to the dolly-shot esthetics championed by Max Ophuls and a whole batch of New Wave film-makers.

The sum of the technical shifts in the last decade has been to increase the possibilities of location film-making and to free film-makers from some logistical and financial production hassles. Though it would take statistical analysis to prove or disprove my impression that location exterior (and especially low-light) scenes are much more common now than they were a decade ago, and that they now more frequently form parts of the syuzhet rather than syuzhet gaps, the major drawback to such scenes (their cost) has been lessened. The film industry's ability "to turn the world into a story" (to use Mitry's famous phrase) has been increased in that more kinds of "natural" scenes can now be appropriated for fiction. But there is very little that is esthetically revolutionary in the new technologies, and nothing that would upset the basic film-making power structure. Changes have been conservative, a defense against inroads and threats brought by very rapidly evolving video technologies. Pressure from the outside rather than forces within the film industry has given us the new toys we work with on location. Each of these toys also plays to the extant power structure within the film-making community.

To grasp how new technology functions it is perhaps helpful to outline the economic and professional interests each technical shift favors. Low-budget film-makers, pushed out of the "industrial" market by video, mostly switched to video, bankrupting a lot of small 16mm equipment manufacturers and labs in the process. But at the higher budget levels, the mystique of film quality was promoted heavily by everyone from Eastman on down. Those with the most to lose by competition with video pushed the new technologies hardest. Crafts-people with a life invested in film technique were eager to try any new film tool that would make them more competitive. Rental houses could make money renting out new "top of the line" tools that changed quickly enough to keep film-makers from wanting to buy them, but still were rentable because they "worked like" older tools. Equipment manufacturers exploited film-makers' desire to survive and the willingness of rental houses to buy their stuff as a nudge to bring out "ever-better" tools. Accommodation was made to eventual video use by promoting the use of film as an originating medium and accepting the reality of Rank-Centel or Bosch video transfer. Driven by the nightmare of hearing the

phrase "we could just as well have done it on tape," the film community made its internal power accommodations and promoted its mystique of quality in order to survive in the higher-budget ends of the industry. In a weird sense, the threat from video was approached with a triage mentality. What was irrevocably lost was simply accepted—films would be transferred to and shown on video. What was seen as "working" all right without change, that is, film's basic rhetoric and "tradition of quality," was deliberately not undermined by technical shifts but instead was reinforced. What was changed were production practices and technology. The changes made here were meant to expand the domain of fictionalized establishment practices into areas in which video could not compete well, such as location film-making. Video has (at least at present) real problems in dealing with on-location light contrasts. Film's light acceptance range makes it unbeatable on-location. A battery of technical changes were gradually instituted so that film's on-location advantages could be maximized. The last decade has been a power struggle between factions in the entertainment industry. Technology has simply been a tool for gaining or retaining financial power.

What can be said about the relationships between change in cinema and technical change on the basis of recent film history? Nothing very global. There have been some changes in what we see and hear and how actors act. But each change, as it came, was so subtle, so well masked, that no major change ever was "felt" by audiences. The film industry's defensive maneuvers of the 1970s and 1980s are far different from the flaunting of color, 3-D, and wide-screen in the 1950s (and judging by industry finances, far more successful). But the changes that have occurred are still not fully played out, so to argue either the parallels or differences between the last decade and preceding ones would be to deny the complexity (and complex approaches to the craft) of film as a technological medium and art form. In film, as Ingmar Bergman put it, "God is details." So large theoretical claims must be put on hold, or at least balanced with one another in recognition of the different perspectives from which cinema can be seen.

The basic problem in theorizing about technical change in cinema is that accurate histories of the production community and its perspectives, as well as of the technological options that face film-makers, must precede the attempt to theorize. And theory itself must limit itself to a little bit of history at a time. It is not that we do not need theory that can help us understand the relationships between larger social and cultural developments, ideology, technical practice, and the history of cinema. Rather it is that whatever we do in our attempts to theorize, we need to welcome all the available sources of information, from all available perspectives, tainted or not, and try to put them in balance. Anything less than that approach lessens us as students of cinema by denying the complexity of the art we study.

Videophilia:

What Happens When You Wait for It on Video

Charles Shiro Tashiro

Vol. 45, no. 1 (Fall 1991): 7–17.

Since the early 1980s, there has been a steady increase in the revenue generated by marketing of theatrical films on videocassette and disc. This mass dissemination has been a boon to those interested in close study of film texts as well as to those simply interested in owning a copy of their favorite films. However, this apparent windfall has usually been embraced with little attention to the technical issues raised by the movement of a text from one medium to another or to the consequences of film evaluation based on video copies.

This discussion is meant as a broad overview of home video, and much of it is relevant to both videocassette and videodisc. However, I have concentrated on the latter, since it has evolved into the "quality" video medium, with a greater focus on duplicating the cinematic experience and an increased sensitivity to the technical requirements of film. (As a former producer for the Criterion Collection, including their edition of Lawrence of Arabia , I have some insight into the factors that go into disc production.) In particular, more attention to visual matters has popularized the transfer of wide-screen films at full horizontal width, with the resulting "letterbox" shape.[1] Videodisc publishers' attempted fidelity to film originals, the theoretical problems raised by such an attitude, and its relevance to film viewing and analysis are the focus of this paper.

The Videodisc Medium

To some extent, videodiscs would appear to be the film enthusiast's dream come true. They are light, portable, easy to store. With the growth of the market, a larger catalogue of titles is available.[2] While not cheap, the retail price is well below fees for print rental, not to mention the astronomical sums for purchase. Moreover, discs are (at least in theory) permanent, unlike either videotape or film, which deteriorate with each use.

Film never wears out faster than when run through a flatbed editing machine, the condition best suited for close analysis. Videotape offers fast-forward and rewind, but is much slower than the nearly instantaneous access available with videodisc players. Consumer-level VCRs, in addition, cannot offer the true freeze frame that a CAV videodisc offers. Disc players can also interact with computers and offer higher picture resolution than most commercially available tape gauges.[3] And there is, finally, the greater attention paid to the video transfer true of at least some videodisc publishers.

Still, with videodiscs there are trade-offs and underlying ideological assumptions. For example, unlike compact audiodisc players (a related technology), which usually have a feature to play songs in random order, videodisc players cannot randomly "scramble" the chapter encoding included on some discs. Presumably this lack of scrambling ability is based on the assumption that the film viewer will not be interested in mixing up the linear flow of the narrative. The players also do not have a feature to play sound at anything other than regular speed, which obviously assumes that only the picture is worthy of multispeed analysis.[4]

These features are designed into (or out of) the medium. Some are more beneficial to the user than others; all are ideologically dictated. But the limitations of the machinery itself and the assumptions that go into its design must be considered (if only in the background) in any discussion of the use of discs for pedagogical, analytical, or substitute cinematic viewing purposes. We must also consider the strategies of moving the text from film to video.

Transfer/Translation

The term "film-to-video" transfer is itself an ideological mask. Its connotation of neutral movement from one location (projection in a theater) to another (viewing at home) hides the reconfiguration of the text in new terms. A more accurate expression would be "translation," with its implicit admission of a different set of governing codes. While film and video share common technical concerns (contrast, color, density, audio frequency response, etc.), their means of addressing those concerns differ. The conscientious film-to-video transfer is designed to accentuate the similarities and minimize the differences, but the differences end up shaping the video text.

We might call the ease of translating a particular film to video its "videobility." A film with high videobility translates relatively easily, perhaps even gaining in the process. (Which is to say that there are elements in the film that come through more clearly on video. Subtlety of performance, intricacy of design, for example, may be lost in the narrative drive of the one-time-only cinematic setting, but en-

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

hanced at home.) A film of low videobility translates with more difficulty. There are two components to videobility: technical and experiential. Technical differences of image between film and video center around three issues: 1) brightness and contrast range, 2) resolution, and 3) color.[5] As for the sound, a sound track mixed for theatrical exhibition may, when transferred to video, have tracks that will not balance "properly" at home. (For example, dialogue tracks may be drowned out by ambience tracks, etc.)[6]

Consider the following hypothetical example. A young couple, with their baby daughter, sits next to a window covered by horizontal blinds. Next to the window is an open doorway, leading out into a garden ripe with daffodils in summer sunlight. A butterfly flits across the flowers, attracting the attention of the baby, dressed in a bright red dress. She toddles out into the sun to chase the butterfly as her parents remain in the alternating shadows and shafts of light caused by the horizontal blinds. The mother looks at the father, then says "I think it's time we called it quits" at just the moment their daughter, as she reaches for the butterfly, trips and falls giggling into the flowers.

As we work to translate this image into video, problems arise immediately. First, there is the brightness range between the garden in sunlight and the parents in shade. Film records this juxtaposition without difficulty. But as the telecine operator exposes the video for the father and mother, the baby, butterfly, and flowers disappear into a white blaze; correcting for the baby, the parents disappear into murky shadow.

A choice has to be made, but which is more important? Attention to narrative would dictate exposing for the most significant action. Reasoning that the overall film is about the couple's divorce, the operator decides that the line "I think it's time we called it quits" is more important and thus chooses to expose for the interior. The baby's giggle seems to come out of nowhere; even if the juxtaposition between the line and the baby's giggling were not there, letting the flowers go to blazes runs the risk of losing the sensual detail. This detail may not dominate a film, but its cumulative effect is certainly a powerful influence on our perception.

The operator decides to make an overall adjustment in contrast to bring all the brightness ranges into midrange, thus making the image more "acceptable" to video. As a result, the alternating light and shadow are readable as a pattern and the baby in the flowers reappears out of the white sun.

Just about everything is visible now, but the sacrifice has been to change all the tonal values into the middle greys. Vividness of color and detail are lost, and the image looks as if it's been washed with a dirty towel. (As an example of just such a "dirty towel" transfer, see the video release of Joseph Losey's Don Giovanni .) The video image is acceptable within the limitations of the medium but unsatisfactory as a reproduction of the film image. In other words, the overall contrast of the image can be "flattened" to conform to the technical limitations of video, but the visual impact has been flattened as well. Thus, films photographed in a low-key or contrasty manner might be said to have low videobility because of the difficulty in reproducing their visual styles.

But there is another problem with our scene. The horizontal blinds read perfectly well on film because of its resolving power. But on video, they produce a distracting dance as the pixels inadequately resolve the differences between the blinds and intervening spaces. In other words, film can read the interstices between the blinds and reproduce that difference; video, trying to put both the blind and the space into the same pixel, cannot. (This is why TV personalities do not wear clothing with finely detailed weave or patterns.) The only way to compensate for this "ringing" effect is to throw the image slightly out of focus.

The resolving power of the film image is almost always greater than that of video. It is this greater resolution that enables the film image to be projected great distances. It is also this resolution that allows the greater depth

and sensory detail that we associate with the filmgoing experience. Therefore, a film dependent on the accumulation of fine details also has low videobility. (For example, in the MGM/UA letterboxed video release of Ben-Hur's chariot race, the thousands of spectators become a colorful flutter; the spectacle of Lawrence of Arabia is also significantly reduced by the low resolution of background detail.)

And what about color? Although photography and video color reproduction are fundamentally different (one is a subtractive process, the other additive), it is the limitations of the video image that present the greatest problems, particularly the handling of saturated reds. Too vibrant or dense, and the signal gets noisy. But since red is often used to attract attention, it cannot be muted too much in video without violating visual design. Thus, color balance on the baby's dress would have to be performed carefully to allow the red to "read" without smearing. (For examples of dissonant reds, see Juliet's ball dress in the Paramount Home Video release of Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet; also note the scenes inside HAL's brain in the MGM/UA release of 2001: A Space Odyssey .)

On the other hand, the relative imprecision of video does have some advantages, or, at least, it can be exploited. For example, optical effects in film, such as dissolves, "announce" themselves because of a noticeable shift in visual quality as the optical begins. This shift results from the loss of a generation involved in the production of the optical effect. To some extent, because the video image lacks the same resolution, the differences between the first-generation film image and the second-generation optical image can be lessened. In effect, the difference takes advantage of video's inferior resolving power to make the first-generation image look more like the second-generation image.

There are other problems, though, that result indirectly from the relatively low fidelity of the video image when compared with the high-fidelity sound reproduction possible with only a modest home stereo. Classical narrative is structured on the notion of synchronization between image and sound. This synchronization has a temporal component: we expect words to emerge from lips at the moment they form the letters of those words; when a bomb goes off, we expect to hear an explosion, etc. But there is also a qualitative component to synchronization. A big image of an explosion should be loud; a disjuncture occurs if the audio "image" remains large when that big image is reduced to a small screen. Imagine attending the opera and sitting in the last row of the upper balcony but hearing the music as if sitting in orchestra seats.

Home stereo is not equal to a theater. But subjectively, it is much closer in effect to the theatrical experience than a television image is to a projected film image. Moreover, when the sound tracks maintain some aspects of theatrical

A spinner in Blade Runner

viewing/hearing that are easy to maintain in audio but impossible to duplicate in picture, we're once again conscious of the differences, not only between picture and sound, but between video and film. For example, in the opening scene of Blade Runner , a spinner (flying car) appears in the background, flies toward the foreground, then disappears camera left. As it retreats into the distance behind us, the sound continues (at least in those theaters equipped with surround stereo), fading into the distance, even though the image is no longer on the screen.

When this effect is duplicated in the Criterion Collection's letterboxed edition of the film, the audio decay of the spinner goes on too long or not long enough, depending on where you've placed your speakers. While the speakers can be moved, doing so runs the risk of throwing other sounds out of "synch." Even if it doesn't affect other sounds, however, the labor of moving speakers around for each viewing session takes the home video experience a long way from the passive enjoyment of sitting in a darkened theater, allowing yourself to be worked over by sight and sound.

"Improving" the film original by correcting optical effects, "fudging" the video when it can't handle the superior resolving power of film images, "flattening" the contrast ratio in order to produce an image that registers some version of the information contained in the original, together with audio that by its technical superiority reinforces our awareness of the video image—at what point do these differences produce a product no longer a suitable signifier of the film signified? Colorizing, for example, while damned as an obvious distortion

of the film, can also be defended as improving the original. Is the conscientious transfer any less of a distortion? Preserving the "original" film text may prove as elusive a goal as the "unobtrusive" documentary camera.

The Disintegrating Text:

Videodiscs as Classical Ruins

Reconstructions of ancient architecture can be attempted from the fragments scattered across a landscape. But a rebuilt Parthenon is still a product of the archaeology that researched it. Videocassettes and discs are like large shards—hints of the original. But discs are not just the ruins of their forebears, they are the guns that destroy the temple by taking the archaeological process further, breaking the flow of a film into sides, segmenting the programming into "chapters," halting it altogether with freeze frames, encouraging objective analysis.

Film viewing, of course, is not genuinely continuous, since a feature film is divided into several reels. The theatrical experience, however, represses the disruption of reel breaks by quick changeovers of projectors, producing an illusion of continuous action. Videotape maintains that flow, at least for average length films. Discs cannot,[7] and publishers are thus faced with the problem of where to break the narrative. The decisions are governed by two concerns: 1) length limitations of the side—one hour for a CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) disc, 30 minutes for a CAV (Constant Angular Velocity) disc, and 2) suitability of the break.

Choice of breaks is not as simple as it might seem. For example, with a 119-minute film, it is not just a matter of putting 60 minutes on one side, and 59 minutes on another. If the 60-minute mark occurs in the middle of dialogue or a camera movement, then the break has to be pushed back to the previous cut. If there's an audio carryover over that cut (particularly a music cue), then other problems arise. If aesthetic considerations suggest going back before the 59-minute mark, it will no longer be possible to fit the film on a single disc, which means a rise in production costs. Faced with such an alternative, aesthetic considerations become secondary. (For example, consider the break between sides one and two on the Criterion CAV Lawrence of Arabia , which occurs in the middle of a dissolve between Lawrence and Tafas in the desert and their retrieval of water from a well. This break subverts the linkage function of a classical dissolve, here intended to bridge two disparate times and locations. On the disc, the desert and the well remain distant, separated by the time necessary to change sides.)

The disruption to narrative is inevitable, though, wherever the break is placed. It can be ignored , but it cannot be overcome . The jolt created by the side breaks becomes an integral part of the text. Moreover, the passive watching of

the theatrical experience is replaced by one involving labor, however minimal (getting up and switching sides), encouraging a literal, physical interaction with the medium. (Imagine what it would be like if in the middle of every theatrical viewing you had to wait a few seconds before the film continued; imagine further what it would be like if you were responsible for continuing the experience.) This physical interaction involves the proletarianization of the video viewer by forcing him/her to become, in effect, a projectionist. And any suppression of the knowledge of technology thus requires a conscious activity: we cannot pretend that the discourse will proceed without us, because it won't until we get off the couch and flip sides.

This fragmentation of the viewing experience gets reinforced by the chapter encoding (although most discs are still produced without chapters). By their very name, chapters call attention to the hybrid nature of the medium. The obvious comparison is with a book. But book chapters are chosen by their authors; however much they segment the narrative, that choice arises at the moment of composition. As such, they are an integral part of the book's form.

Videodisc chapters are not cinematic composition, they are videodisc imposition. They aren't chosen at the point of film production, but after the fact, a voice from outside the text.[8] While common sense might lead one to expect chapters to be equivalent to the cinematic "sequence," in fact they often do not conform to any breakdown of the cinematic action, and there is no single pattern or rationale for their placement. They do, however, encourage the user to think of the text as something other than an unrolling, uninterruptible narrative. (For this reason, at least one well-known producer/director refuses to allow chapter encoding on disc releases of his films.)

Furthermore, while the chapter metaphor evokes books, their function is more similar to the track or cut of an LP or CD. The visual appearance of the videodisc, obviously intended to evoke the LP,[9] reinforces this hybrid association. Scenes or segments of the film end up getting treated like individual pop songs on a record or CD: no longer related to their immediate surroundings, they become isolated as discrete units. Chapter stops run like a mine field under the linear development of classical narrative. Fans of a film no longer have to sit through the parts they don't like; they can jump to their favorite scenes, in whatever order they choose. Imagine how different an experience it would be to enter a movie theater and be able to skip the tedious parts or scramble the order of the reels. "I came for the waters . . ." zip "We'll always have Paris." And I suspect even the viewer interested only in watching the movie will use the chapter encoding for quicker access. Isn't one of the consequences of the repeated viewings encouraged by home video boredom? The significance of chapters is that viewers are beginning to think in these terms, to feel in control of a film's tedium.

If chapters evoke books and records, freeze frames turn a film into a sequence of stills or paintings. In so doing, they further destroy linear development. A single CAV side contains 54,000 frames. That's 54,000 possible points of fixation, alternative entries into an imagistic imaginary. The film's characters and story can be discarded in favor of new narratives inspired by the images. Just as photographs and paintings arrest our gaze and inspire us to invent, so too the frozen film image, isolated in time, loses its context and creates a new one.

With motion removed, the film image becomes subject to a different critical discourse. No longer is it enough to talk about an image getting us from point A to B (the narrative prejudice). Criticism of the image's frozen form, composition, lighting, color are invited. Individual images can be subjected to the standards of photography and painting. Of course, few film images can withstand such scrutiny, since most are composed in movement.

Of course cinema cannot be reduced to its still frames and the semiotic system of cinema cannot be reduced to the systems of painting or of photography. Indeed, the cinematic succession of images threatens to interrupt or even to expose and to deconstruct the representation system which commands static paintings or photos. For its succession of shots is, by that very system, a succession of views.[10]

To the extent that they encourage a criticism based on alternative codes, freeze frames threaten the very basis of classical narrative, in effect reversing the semiotic power relationship noted by Dayan.

"You Have to See It in a Theater"

An undergraduate film-appreciation class at the University of Southern California is taught on the basis that films, in order to be understood fully, must be seen under theatrical conditions. Great expense is taken to obtain good prints; screenings occur in a large facility analogous to first-run theaters in the Los Angeles area. Stress is placed on the larger-than-life aspect of filmgoing. And yet, when a scheduled film is unavailable in 35mm, dirty, murky, 16mm prints are used. Is this part of the theatrical experience?

Yes, although in ways not likely to be on the minds of anyone prejudiced toward theatrical exhibition. This attitude implies that theatrical viewing conditions, even at their worst, are preferable to viewing a decent video version at home. But film exhibition is subject to a range of factors—print quality, film gauge, optical vs. magnetic sound, stereo vs. mono, screen size, aspect ratio,

High "videobility": The Wizard of Oz

the quality of the reproductive machinery—beyond the control of the consumer. So—which violates the film more, a good video or a bad print?

Most video transfers are made from technically superior film sources. At their best, the resulting tapes or discs have a uniform gloss that is generally not true of theatrical prints outside of initial runs. The benefit of this uniformity is a standardization of presentation, dependent only on the hardware used for reproduction. Of course, all forms of standardization involve loss as well as gain. The variability of theatrical projection can have unintended benefits, when elements not noticed in one circumstance show up under others. But it seems unlikely that anyone would prefer a scratchy, inaudible reduction print made from a third generation negative to a video copy made carefully from an early generation source.

Earlier, I introduced the concept of videobility to describe the ease of translating a film into video. But videobility involves more than just questions of whether or not a decent video image can be produced. Some films have high videobility (The Wizard of Oz probably seems more familiar on video than in a theatrical screening, since most of us know the film through television broadcast). Others strike us as impossible to imagine on video without significant loss (Bondarchuk's War and Peace , for example). Is there, then, something in the viewing experience that depends on theatrical conditions for full effect of a given film? Or, more properly, what does video lack that film possesses that makes the theatrical experience "essential"?

In "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," Walter Benjamin wrote that

The cult of the movie star, fostered by the money of the film industry, preserves not the unique aura of the person but the "spell of the personality," the phony spell of a commodity.[11]

Is the quasi-religious aspect of film viewing, induced by capital or not, "phony"? If a film succeeds in moving us to ecstasy, does it matter in experiential terms whether or not it is a "true" sensation? The ecstatic component of (some) filmgoing cannot be dismissed, particularly when discussing it in relationship to home video. For this religious aspect of filmgoing is clearly lacking in home video viewing.

One obvious reason for this lack is the difference in scale. As the cliché has it, film is larger than life, television smaller. And yet the difference between video and film experiences is not scale as such , but the depth that greater size gives to film's sensory extravagance. It is that richness, sensual saturation, and euphoria that video cannot duplicate. But if video is excluded from the Dionysian, it gives access to the excess that creates ecstasy through the capacity to repeat, slow, freeze, and contemplate. Savoring replaces rapture.

Letterboxing, Mon Amour

The problem of scale has, from the first, been linked to the related issue of aspect ratio. CinemaScope and other wide-screen processes were developed (along with high-fidelity stereo sound) with the purpose of overwhelming viewers with an experience not available on their televisions at home. On the other hand, sale of broadcast and video rights of theatrical features represents a lucrative source of revenue, necessitating a means of squeezing wide-screen images into the TV frame. But you cannot fill the TV frame without either cutting off edges of the film picture, or through anamorphic compression, turning the films into animated El Grecos.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in maintaining the theatrical aspect ratio for video viewing. Unfortunately, this interest has bred the fallacious notion that there is a single "correct" aspect ratio. In fact, it is the rule , not the exception, that there is no single "correct" aspect ratio for any wide-screen film. For example, during photography, it is common for directors and cinematographers to "hard matte" some, but not all, of their shots if they expect to exhibit in 1.85 or 1.66. If you examine the negative, some shots would be matted for 1.66, say, and others at full frame 1.33. Which is "correct"?

Full reproduction of Lawrence frame, without matte

Frequently, too, the ratio of photography will be altered when a film changes gauges. A film might be shot in nonanamorphic 70mm at 2:1, reduced to anamorphic 35mm at 2.35:1, then reduced to 16mm at 1.85:1. (The Lawrence of Arabia disc, for example, was produced from a 35mm source, meaning a slight loss of vertical information.) Then there are those processes, like VistaVision, that were designed to be shown at different ratios. As if that weren't complex enough, most projectionists show everything at 2:1. Is "correct" based on intention, gauge, exhibition, breadth of distribution, amount of visual information, . . .?

While it might be more prudent to think of an "optimal" aspect ratio, rather than a "correct" one, who should choose the optimum? Asking the director or cinematographer perpetuates the auteurist mystique while assuming that the filmmaker knows best how a film at home should be watched. This approach further assumes that these people are best equipped to translate film images into video images. To privilege film technicians, then, subordinates video to film.

Prior to the involvement of the film's technicians, optimality was visually determined by concentrating on significant dramatic action and sacrificing composition and background detail (by cropping the edges of the frame). When composition made such reframing impossible (when, for example, two conversing characters occupied opposite edges of the frame), then a "pan-and-scan" optical movement was made; or the frame was edited optically into two shots.

"Full frame" TV image with pan-and-scan

"Full frame" TV image with letterboxed full film frame

Pan-and-scan transfers are performed largely to preserve narrative and to approximate the theatrical experience by keeping the entire television frame filled. There is an implicit assumption that the vertical dimensions of the film frame must be maintained. Letterboxing maintains the full horizontal dimension of the wide-screen image. In effect, pan-and-scan transfers privilege the television (thus subordinating film to video). It is more important to fill the TV frame than it is to maintain cinematic composition. Letterboxing reverses that priority by preserving the cinematic framing.

But a transformation occurs in maintaining composition. (If it didn't, letterboxing wouldn't be controversial.) In his essay "CinemaScope: Before and After," Charles Barr writes:

But it is not only the horizontal line which is emphasized in CinemaScope. . . . The more open the frame, the greater the impression of depth: the image is more vivid, and involves us more directly.[12]

If Barr is correct, letterboxing, by merely maintaining the horizontal measurement of the 'Scope frame, cannot duplicate the wide-screen experience. Letterboxing equates the shape of the CinemaScope screen with its effect .

In fact, while letterboxing subordinates the TV screen to cinematic composition, it simultaneously reverses that hierarchy. If film is usually considered larger and grander than TV, wide-screen film letterboxed in a 1.33 TV frame subjects film to television aesthetics by forcing the film image to become smaller than the TV image. Thus, in the act of privileging film over video, video ends up dominant. (The movement from 70mm theatrical exhibition to 19-inch home viewing is one long diminuendo of cinematic effect.)

Moreover, letterboxing is an ambiguous process, with all the resistance ambiguity encounters. A letterboxed image is neither film nor TV. Its diminished size makes it an impossible replacement for the theatrical experience; at the same time, the portentous black bands at the top and bottom of the screen remind the video viewer not only of the "inferiority" of the video image to the film original (it can only accommodate the latter by shrinking it) but also of a lack. What is behind those black bars? Edward Branigan makes the point that the frame is "the boundary which actualizes what is framed" and that "representation is premised upon, and is condemned to struggle against, a fundamental absence."[13]

The absent in film is everything outside the visual field. In a letterboxed transfer of 'Scope films, the matte hides the bottoms and tops of the outgoing and incoming frames. Viewing the film without the matte would make it impossible for us not to be aware of the "cinematicness" of the image, since we

would be viewing frame lines in addition to the picture. The mattes for "flat" wide-screen films (1.85:1 and 1.66:1) frequently blot out production equipment such as microphones, camera tracks, and so on, that the director or cinematographer assumed would be matted out in projection.

Both frame lines and extraneous equipment are part of the repressed production process. To see them ruptures the classical diegesis. And the fact that such a violence to our normal cinematic experience is necessary in video would call attention once again to the differences between the media. A double exposure of ideology would occur: of the repressed aspects of cinematic projection (frame lines, equipment)[14] and of the presumed neutrality of the transfer procedure.

Yet there is no useful alternative to letterboxing.[15] Form and composition are important; useful analysis of films on video cannot be performed when 43 percent of the image has been cropped, and certainly no one can claim to have seen(!) the film on video under such circumstances. If maintaining the horizontal length of the image creates the fiction that the cinematic experience has been approximated, it is nonetheless a fiction worthy of support. Besides, letterboxing introduces aesthetic effects of its own.

The frame created by the matte contributes one more effect toward treating the cinematic image as an object of analysis. Just as the frame of a painting directs our gaze toward the painting enclosed, so too the letterbox calls attention to the aesthetic qualities of the image framed. But that may be the problem; if people object to letterboxing, it's because it turns their classical narratives into formalist galleries. (Consider how the ponderously pseudo-epic qualities of Lawrence of Arabia get lost in a background blur on video, refocusing attention on the flatness of the image and compositional precision.) In fact, letterboxing does precisely the opposite of what Barr likes about wide-screen:[16] it ends up accentuating composition, rather than effacing it.

"I'll Wait for It on Video"

Who, after becoming used to the flexibility of home video, has not wanted to fast-forward past bits of a boring or offensive theatrical film? Doesn't this desire suggest a transformation of the cinematic experience by home video? What we once might have endured, we now resent. Hollywood continues to offer plodding, linear narratives wilted with halfhearted humanism as the staple of its production. But doesn't our itchy, reflexive reaching for the remote control suggest a complete saturation by classical narrative?

Whether we like it or not, home video turns us all into critics. Instead of being engulfed by an overwhelming image that moves without our participation,

we're able to subject film texts to our whims. And by allowing the viewer greater insight into an object of cultural production, home video starts to break the hold of individual texts and, possibly, of cinema in general. This conscious participation in film viewing can only be helped by the widespread dissemination of film texts, even in hybrid form.

We're back to Benjamin again. Having a good reproduction of the Mona Lisa does not substitute for the actual painting but it "enables the original to meet the beholder halfway," and in so doing, the copy "reactivates the object reproduced."[17] Well-produced home video performs the same function for film texts, which, the "phoniness" of the theatrical experience notwithstanding, are invested with an aura by classical practices of obfuscation, suppression, and capitalist investment in the commodity of the image. As home video allows us to meet the film text halfway, it does to film what film-makers have done to the world for years: turns it into an object for control.

At the same time, a conscious video consumer must confront the reality that home video is a luxury, that the possession of the equipment results from a position of privilege, thus perpetuating the very economic relations the active viewership (might) help undermine. Does this reality turn any video viewing into a guilty pleasure? One answer to this dilemma may reside in the writings of Epicurus, whose philosophy of pleasure derived from moral calculation may be the best guide for the aware consumer:

The flesh perceives the limits of pleasure as unlimited and unlimited time is required to supply it. But the mind, having attained a reasoned understanding of the ultimate good of the flesh and its limits . . . supplies us with the complete life, and we have no further need of infinite time: but neither does the mind shun pleasure.[18]

Videodiscs make us into proletarians and encourage criticism through physical interaction and segmentation. But, produced with care to maintain some aspect of the scopic pleasure of the cinematic image, they make possible a connoisseurship of form that theatrical viewing discourages. Videodisc viewing sits at an awkward juncture between criticism and experience, analysis and ecstasy, progress and privilege. As we participate in this ambiguous vacillation between oppositions, we become a post-modern contradiction: the Proletarian Epicure.

Moreover, home video gives us a means of almost literally "deconstructing" films, helping us remake them to our own ends. Even those who deny their proletarian position by viewing these film/videos in a linear fashion end up, as they change sides or put the VCR in pause, participating in the creation of an

alternative text. Videodiscs, as a hybrid medium dedicated to reproducing an experience alien to it, standardizes, fragments, commodifies, objectifies, and segments that experience. You can "wait for it on video," but "it," like Godot, will never arrive, because the discs' high-tech insouciance offers, despite their truckling to the capitalist realities, a revolutionary hope: the destruction of classical cinema.

Through the Looking Glasses:

From the Camera Obscura to Video Assist

Jean-Pierre Geuens

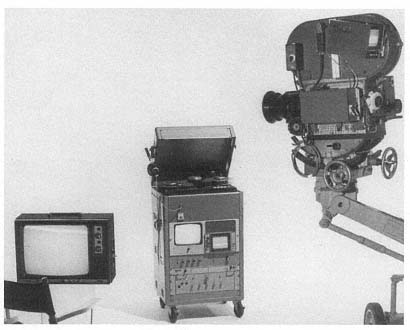

The original video assist apparatus put together by Bruce Hill in 1970

Vol. 49, no. 3 (Spring 1996): 16–26.

The studio is finally quiet. The actors are restless. The crew is ready. "Sound." "Camera." The slate is taken. A voice calls "Action." A voice? Is this really the director, "with his back to the actors,"[1] looking at the scene on a little video monitor? Isn't the director, at least the solid Hollywood professional of old, supposed to sit just next to the camera, facing the action? What's happening here?

Following the trajectory that led from the old-fashioned parallax viewfinders to the contemporary use of video-assist technology, I will argue that "looking through the camera" is never a transparent activity, that each configuration has distinctive features whose design and implementation resonate beyond the actual use of the device. In his still seminal essay "The Question Concerning Technology,"[2] Martin Heidegger warned us that "technology is no mere means,"[3] that the adoption of a new method of production often expresses more than the simple substitution of one tool by another. In Andrew Feenberg's words, "modern technology is no more neutral than medieval cathedrals or the Great Wall of China; it embodies the values of a particular civilization. . . ."[4] Herbert Marcuse is even more radical. For him, "specific purposes and interests of domination are not foisted upon technology 'subsequently' and from the outside; they enter the very construction of the technical apparatus. Technology is always a historical social project: in it is projected what a society and its ruling interests intend to do with men and things."[5] Thus, as far as the camera is concerned, the very appearance of a novel gizmo could itself be significant of cultural or economic changes that have taken place in the film industry prior to the use of the new technology and, in turn, the actual practice of the supplemental device may help shape a different kind of cinema.

In the first years of cinema, getting access to the image that was to be recorded on film was no easy matter. The early cameras could never provide such necessary information. Indeed, not only the pioneer cameras of the 1890s and the

1900s but also the first truly professional cameras used by Holly-wood—the Bell and Howell 2709 and the Mitchell Standard Model—had to resort to peeping holes, miscellaneous finders, magnifying tubes, swinging lens systems, and rack-over camera bodies to give any information at all about the image produced by the lens.[6] At best, the operators were allowed to survey the scene before or after actually shooting it. Crucially missing from their arsenal was the capability to check on exact framing, focusing, lighting, depth of field, and perspective while filming. Although a lens could be precisely focused on an actor's position ahead of time, what happened during the shot, especially if there was any movement, remained a mystery. The operators, in effect, were shooting blind. As they watched through the parallax viewfinder on the side of the camera, a device that produced but a pallid, lifeless, uninviting substitute for the real thing peeked at seconds earlier, they remained outsiders to what was truly going on inside the apparatus. In a way, the mystery of what happened inside the camera during the shooting acted as a synecdoche for the further magic that would be worked on the film in the lab, where it was to be chemically treated and its content at last exposed to view. Only at the screening of the dailies could one know for sure whether the scene was good or needed to be reshot. Such a daunting situtation therefore required steady professional types and, indeed, this is how the "operative cameramen" were described by their peers in the American Society of Cinematographers: "They must be ever on the watch that no unexpected or unplanned action by the players or background changes from the originally planned movement and lighting on the set, occur during shooting. They sit behind the camera, like the engineer at his throttle, ever watching for danger signals."[7] These brave men behind the camera, despite their vigilance, thus stood in a hermeneutic relation to their instrument. The otherness of the machine remained unassailed, its viewing apparatus a numinous, hermetic object standing as a third party between the operator and the world. The best one could do was stand next to the thing, maybe controlling its mishaps or its surges, but, throughout, acknowledging the actual film process as a thorough enigma.

The situation changed in 1936, when the Arnold and Richter Company of Germany introduced continuous reflex viewing with its new Arriflex 35mm camera. The solution was truly elegant: by mirroring the side of the shutter that was facing the lens and tilting it at a 45-degree angle, the light that was not used by the film when the latter was intermittently moving inside the camera was now made available to the operator for viewing purposes. Suddenly, the deficiencies that had marred the early camera systems were eliminated as operators, looking through the lens during the filming, gained maximum control over the images they were shooting. In fact, the smoothness of the Arriflex

solution hid a paradox. Even though the operator may believe he or she sees what the film gets, technically speaking one never actually witnesses the same instant of time that is recorded on film because of the fluctuating movement of the shutter—when the operator gets the light, the film does not, and vice versa. More importantly, this means that the access to the lens is punctuated by the blinking presence/absence of the mirrored shutter. In my view, this flickering implies more than a simple technical chink; it radically transforms the linkage between the operator, the camera, and the world by literally embodying the eye within the technology of the apparatus itself.

Indeed, if we go back to the early years of still photography for a moment, there was always a sense of awe when the operator's head finally disappeared under a large black cloth in order to take the picture. "What do you have there: a girlfriend?" a model asked of Michael Powell's protagonist in Peeping Tom (1960), a comment that clearly exposes the prurience of the act. In a similar fashion, on the motion picture set, the view through the reflex viewfinder quickly became fetishized, the actual practice exceeding the useful aspect of checking on the parameters of the scene. Crew hierarchy determined who got to take a peek. Yet the static image one could witness when the camera was at rest had finally little to do with what happened during the real shooting, when the operator alone received the full force of the system. Then the impact was truly stirring; due to the saccadic nature of the shutter's rotation, the effect on the eye was nothing less than phantasmagoric. Because the other eye of the operator remained closed during the filming, the flickering light on the ground glass became thoroughly hypnotic, even addictive.[8] For the time of the shot, with only one eye opened onto the phantastic spectacle on the little screen, the operator was very much lost in another world, a demimonde, a netherworld not unlike a dream screen for the wakened.