Introduction: The Ethnographic Scene

One phenomenon inherent in the nature of the plural society of the Indian subcontinent is the coexistence—often in a narrow space—of populations varying greatly in the level of material and intellectual development. Confrontation and eventual harmonization are the two possible outcomes of such a state of affairs, and this book focusses on the social problems created by the mounting influence of economically advanced and politically powerful groups on autochthonous societies which persisted until recently in an archaic and in many respects primitive life-style. A full understanding of the disruption caused by this impact within the whole fabric of tribal life cannot be gained from generalizations embracing the totality of the forty millions of Indian tribal populations. The diversity of ethnic groups and cultural conditions is so great that such an approach would be impracticable, and it is for this reason that I have concentrated on a series of microstudies, each dealing with a specific tribal society and with particular problems cognate to the process of social change.

While anthropologically interested Indian readers will have no difficulty in visualizing the tribes mentioned in the appropriate geographic and cultural context, those unfamiliar with the Indian ethnographic scene may well be confused by the kaleidoscopic pattern of tribal societies from which I have chosen concrete examples to illustrate contemporary developments among the tribesmen of the two regions best known to me, Andhra Pradesh and Arunachal Pradesh.

At the risk of repeating what I have written in earlier publications, many now out of print, I propose therefore to set the scene with a

catalogue raisonné describing briefly the various ethnic groups whose members appear as dramatis personae in the pages of this book. For the convenience of the reader wishing to probe deeper into the cultural background of the individual tribes, I have appended to each of the ethnographic vignettes a bibliography listing the main anthropological sources containing information on the group in question. To forestall any accusation of egocentricity, I may mention that in the case of several tribes, such as the Chenchus and Apa Tanis, few published ethnographic data are available apart from the results of my own field research.

Tribes of the Deccan

Chenchus

During the Palæolithic Age, the vast forests and park-lands of South India were inhabited by bands of nomadic people, who lived by hunting and the gathering of wild fruits, tubers, and edible roots. The only traces left by these early foodgatherers are crude stone implements found on the surface of many parts of the Deccan; so far no skeletal remains of the early races have come to light. Yet, in some isolated parts of the subcontinent, small groups of aboriginals persisted until modern times in a way of life which outwardly had changed very little since the Stone Age.

The Chenchus of Andhra Pradesh are one of these ethnic splinter groups, which were left behind by the material advance of the great majority of the South Indian population. Their present habitat is confined to the rocky hills and forested plateaux of the Nallamalai Range, extending on both sides of the Krishna River. Until 1947 this river formed the border between the princely state of Hyderabad, officially known as His Exalted Highness the Nizam's Dominions, and the Madras Presidency of British India. At that time Chenchus were found both in Hyderabad and in British territories, but today their entire habitat lies within the state of Andhra Pradesh, which contains the overwhelming majority of the speakers of the Dravidian tongue of Telugu, the language spoken also by the Chenchus.

Although in the census of 1971 more than 18,000 Chenchus were enumerated, only a few hundred persist today in their traditional life-style as semi-nomadic forest dwellers, and it is with the latter that we are mainly concerned in the context of this study.

In their physical make-up the Chenchus conform largely to a racial type described by anthropologists as Veddoid, a term derived from the Veddas, a primitive tribe of Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Like the Veddas, the

Chenchus are of short and slender stature with very dark skin, wavy or curly hair, broad faces, flat noses, and a trace of prognathism. Though no longer dressing in leaves like their ancestors, of whom the seventeenth-century Muslim chronicler Ferishta gave a poignant description, they normally wear but the scantiest dress: the men small aprons suspended from a fibre or leather belt, the end drawn in between the legs, and the women cotton bodices and a length of sari-cloth wound round their hips. There is no people in India poorer in material possessions than the Jungle Chenchus; bows and arrows, a knife, an axe, a digging stick, some pots and baskets, and a few tattered rags constitute many a Chenchu's entire belongings. He usually owns a thatched hut in one of the small settlements where he lives during the monsoon rains and in the cold weather. But in the hot season communities split up and individual family groups camp in the open, under overhanging rocks or in temporary leaf-shelters.

The basic unit of Chenchu society is the nuclear family, consisting of a man, his wife, and their children. For all practical purposes husband and wife are partners with equal rights, and this equality of status means that the family may live with either the husband's or the wife's tribal group. Each such group holds hereditary rights to a tract of land, and within its boundaries its members are free to hunt and collect edible roots and tubers. These used to be the Chenchus' staple food, though we shall see that in recent years there has been a change in their diet and ways of subsistence.

The Chenchus are characterized by a strong sense of independence and personal freedom. None of them feels bound to any particular locality, and the ability to move from one group to the other allows men and women to choose the companions with whom they wish to share their daily lives. Marriage rules are based on the exogamy of patrilineal clans. As long as they observe the rules of clan exogamy young people are free to marry whomsoever they wish. Spouses can separate without any formality, but the abduction of a woman still living with her husband is disapproved of as immoral.

In the sphere of religion the Chenchus evince certain characteristic traits which distinguish them from the surrounding Hindu peasantry. Though they worship some of the deities prominent in the cult of Telugu villagers, they accord much greater importance to a powerful goddess who has control over the game and the fruits of the forest. They also revere a sky god who shares some features, including name, with the Hindu supreme divinity Bhagavan and, though not believed to intervene very much in human affairs, is credited with power over life and death. The Chenchus' ideas of man's fate after death are vague, and it would seem that various notions adopted from their Hindu neighbours have not been incorporated into a consistent body

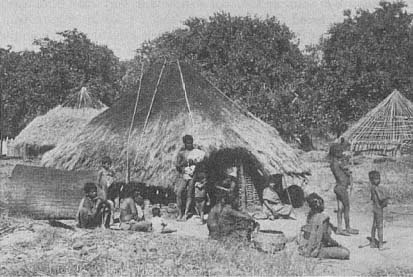

The Chenchu settlement of Pulajelma in 1940; during the dry winter season

the round huts with conical roofs are being rethatched. In the background is

the framework of a hut under construction.

of eschatological beliefs. There is no definite idea that a person's fate in the hereafter depends on his deeds in this life, even though some Chenchu stories contain references to reincarnation. More widespread is the belief that a person's life-force (jiv ) is derived from the supreme god and returns to him after death. The whole concept of a life-force, a belief common to various Indian populations, very likely stems from casual contacts with Hindus, and thus represents a comparatively new element in Chenchu thinking.

Until two or three generations ago, the Jungle Chenchus seem to have persisted in a life-style similar to that of the most archaic Indian tribal populations, and their traditional economy can hardly have been very different from that of forest dwellers of earlier ages. In the following chapters we shall see that, despite recent developments and innovations, the Chenchus still stand out from all the other tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh.

In other parts of India, however, there are still some comparable groups of foodgatherers who have so far resisted the pressure to move out of the forests and change over to a more settled life. Several of these tribes inhabit the forested hills of the Southwest Indian state of Kerala. Anthropologists have studied the Kadars, who form the subject of a book by U. R. von Ehrenfels, and the Malapantaram, also known

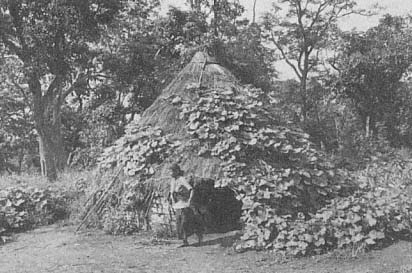

A hut in the Chenchu settlement of Boramacheruvu in 1978. There has been

no change in the structure of huts, but Chenchus have learned to grow

marrows and to train them up the roofs of their huts.

as Hill Pantaram, whom I visited in 1953 and who were subsequently investigated in depth by Brian Morris. Of special interest are the parallels between the Chenchus and the Veddas of Sri Lanka, the first South Asian tribe of hunters and foodgatherers to arouse the interest of western scholars, notably C. G. Seligmann and P. Sarasin. The Veddas have virtually given up their traditional life-style, but during some brief encounters with groups of semi-settled Veddas I was struck by a physical similarity between Veddas and Chenchus so close that it would be exceedingly difficult to distinguish members of the two populations if brought together in one place. Though separated by a distance of hundreds of miles and a stretch of sea, the two groups may well be remnants of the most archaic human stratum of South Asia.

Bibliography

Ehrenfels, U. R. von. The Kadar of Cochin. Madras, 1952.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Chenchus--Jungle Folk of the Deccan. London, 1943.

——. "Tribal Populations of Hyderabad: Yesterday and Today." Census of India, 1941. Vol. 21. Hyderabad, 1945.

——. "Notes on the Malapantaram of Travancore." Bulletin of the In-

Chenchu drawing his bow. Hunting used to be an important activity of the men,

and though game has been depleted Chenchus are still in the habit of carrying

bows and iron-tipped arrows.

ternational Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research , no. 3 (1960), pp. 45-51.

Morris, Brian. "Tappers, Trappers and the Hill Pantaram." Anthropos 72 (1977): 225-41.

Seligmann, C. G., and Brenda. The Veddas , Cambridge, 1911.

Sarasin, Paul und Fritz. Die Weddas von Ceylon und die sie umgebenden Völkerschaften. Wiesbaden, 1893.

Scott, Jonathan. Ferishta's History of Dekkan. Shrewsbury, 1794.

Konda Reddis

Among the aboriginal tribes of India there are many which persist on an economic level characteristic of the period in human history when man first abandoned the nomadic habits of hunters and foodgatherers and began to raise edible plants. In some parts of the world this revolutionary step occurred more than ten thousand years ago and was soon followed by further developments in agricultural techniques. In India, however, there exist tribal people who never advanced beyond a primitive type of agriculture, known as shifting or slash-and-burn cultivation, though most of them are now abandoning this way of life

Digging for edible roots and tubers remains an essential feature of Chenchu

daily life. The iron spikes of the digging sticks are purchased from blacksmiths

of the plains villages.

under the pressure of governments objecting to such tillage as wasteful of limited natural resources. Until half a century ago, tribes of slash-and-burn cultivators were found in many of the hill areas of Middle and South India, and in extensive regions of Northeast India shifting cultivation is still the predominant type of tillage.

The Konda (or Hill) Reddis of Andhra Pradesh are one of the tribal groups which depend to a great extent on slash-and-burn cultivation. They inhabit the wooded hills flanking the Godavari River where it breaks through the barrier of the Eastern Ghats. In the same way as the Krishna River separated the Nizam's Dominions from British territory, the Godavari formed the boundary between the erstwhile Hyderabad State and the East Godavari Agency of Madras Presidency. Today the great majority of Konda Reddis are found within Andhra Pradesh, though a few communities live in the adjoining Koraput District of Orissa. The Konda Reddis must be distinguished from the important Hindu caste also known by the name Reddi, which is politically the most powerful in the state and, at the time of writing, includes among its members the President of the Republic of India. The tribe of Konda Reddis has a strength of 43,609 and is divided into several sections differing in the manner of their assimilation to neigh-

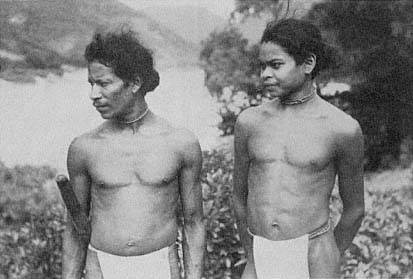

Konda Reddis of a riverside village in the Godavari Valley; the men wear

langoti tucked into a belt of twisted creeper.

bouring, economically more advanced Hindu castes. Like most other populations of Andhra Pradesh they speak Telugu, but in their racial composition, which includes primitive Veddoid as well as more progressive strains, they are clearly distinct from the majority of Telugu-speaking castes.

Traditionally the economy of the Reddis is based on the periodic felling of forest and the cultivation of various millets, maize, pulses, and vegetables in the resulting clearings. This type of tillage, in which the axe and not the plough is the primary instrument, is in Andhra Pradesh known as podu , in Madhya Pradesh as bewar or penda , and in Northeast India as jhum . But there are important differences among the various forms of shifting cultivation. While the Naga, Nishi, or Hill Maria uses a hoe to turn over the soil on his hill fields, the Reddi of the Godavari region broadcasts all small millets without so much as scratching the surface of the ground and dibbles the great millet (Sorghum vulgare ), maize, and pulses into holes made with his digging stick. It can safely be said that Reddi agriculture represents as crude a form of cultivation as may be found anywhere on the Asiatic mainland. It is by no means efficient, and at some times of the year when their stores of grain have run out, Reddis subsist on wild forest produce, eating the sago-like pith of the caryota palm or the kernels of

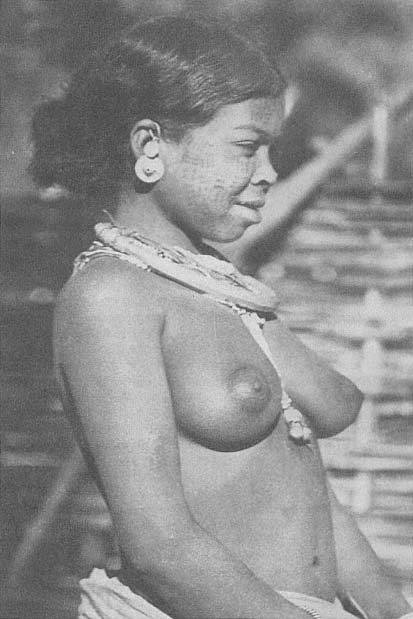

Reddi woman and child of the hill village of Gogulapudi; Reddis buy cotton

cloth and gilded nose ornaments from neighbouring plainsmen.

mango stones. They also hunt with bow and arrow, and those living on the banks of the Godavari add to their food supply by fishing, often from dug-out canoes.

Traditionally ownership of the land was vested in local groups whose members may hunt, collect, and cultivate anywhere within the territory belonging to the community.

The sense of unity based on a group's common ownership of a tract of land finds expression in joint ritual activities. Though not all the members of a group need live in one locality, they combine for the celebration of seasonal festivals and for the performance of sacrificial rites connected with the agricultural cycle. The atmosphere within such a local group is entirely egalitarian, but one man acts as head of the community. His position is usually hereditary in the male line, and his function lies mainly in the religious sphere. Acting as mediator between man and the local deities to secure the prosperity of the community, he inaugurates the sowing of the grain crops and propitiates the earth mother with sacrifices of pigs and fowls. This goddess is the only deity who is thought to be entirely and unalienably well-disposed towards humans, and is therefore regarded with gratitude and affection. The Reddi's attitude toward other deities and spirits is one of caution rather than reverence, for these supernatural beings are

Hills flanking the Godavari River bear the marks of the Reddis' slash-and-burn

cultivation. The light patches are fields on which the crops have been harvested

and only stubble is standing.

deemed potentially dangerous as well as helpful. The hills and forests are believed to be inhabited by a host of anthropomorphically conceived divinities, many of whom have their seats on mountain tops, and are hence referred to as konda devata , i.e. "hill deities." Ordinary people cannot see them, but there are magicians and shamans who can communicate with supernatural forces in dreams as well as in a state of trance.

The improvement of communications in recent years has made the Reddis' habitat accessible to outsiders, and we shall see that the commercial exploitation of forests has brought about a change in their style of living and has involved the loss of the freedom and independence of their traditional forest life.

The Konda Reddis are not the only tribe of slash-and-burn cultivators in the Eastern Ghats, and it is not unlikely that in the not very distant past the entire tangle of hills rising from the eastern coastal plains was inhabited by populations of a similar economic pattern. Even today the northernmost group of Reddis adjoins a small tribe known as Dire or Didayi, who occupy a hill tract inside Orissa but close to the border of Andhra Pradesh. The Dires speak a Munda language akin to that of the Bondos, but otherwise have much in common with the Reddis, whom they also resemble in racial type. The fact

Reddis of Gogulapudi dibbling millet on a plot newly cleared of forest growth;

the seed is dropped into holes made with iron-tipped digging sticks.

that Munda- and Dravidian-speaking groups share similar cultural features suggests that the economic and social pattern characteristic of the primitive shifting cultivators of the Eastern Ghats cannot be associated with any one ethnic or linguistic group.

Bibliography

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Reddis of the Bison Hills--A Study in Acculturation. London, 1945.

——."Notes on the Hill Reddis in the Samasthan of Paloncha." In Tribal Hyderabad--Four Reports . Hyderabad, 1945.

Thurston, Edgar. Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. 3. Madras, 1909. P. 354.

Kolams

At a distance of some 250 miles from the habitat of the Konda Reddis lies the highland of Adilabad, the northernmost district of Andhra Pradesh. Until a generation ago a tribe known as Kolam (or in their own language, Kolavar) lived in this highland in a style very similar to that of the Reddis. We shall see in chapter 3 that the reservation of

forests has largely destroyed the life-style and indeed the entire economic basis of Kolam society. In the 1940s, however, groups of Kolams still practised slash-and-burn cultivation, and their agricultural methods differed from those of the Reddis of the Godavari region only in minor details. Whereas the Reddis cultivate with digging sticks, the Kolams use a small hoe with an iron spike affixed by means of a socket to a knee-shaped shaft. It is a poor instrument compared to the broad hoes of such tribes as the Maria Gonds or Saoras, and does not turn over the soil but only scratches it. The same iron point can be hafted alternatively on hoe and digging stick, the latter being used for dibbling sorghum and maize, while the hoe is frequently used also for digging up edible roots.

Unlike Chenchus and Konda Reddis, who speak only Telugu, the Kolams have a language of their own which belongs, like Gondi, to the intermediate group of Dravidian languages. When talking to Gonds or Pardhans, Kolams generally speak Gondi, in which tongue most of them are fluent. In the eastern part of Adilabad District there are some groups of Kolams who have lost their original language and speak Telugu, and some groups in the Kinwat Taluk of Maharashtra speak Marathi. In these cases the loss of the tribal language means that Kolams living in adjoining regions can no longer communicate with each other, for members of the somewhat detribalized groups do not necessarily speak Gondi either.

The social organization of the Kolams is based on a system of exogamous patrilineal descent groups, each of which is associated with an ancestral territory and a common cult centre. Several of such lineages are grouped together in larger equally exogamous units which bear names identical with those of some Gond clans. Intimately linked with the system of localized patrilineal clans is the cult of a deity known in Kolami as Ayak, but referred to by speakers of Gondi as Bhimal and by those of Telugu as Bhimana. Within the territory which the members of a Kolam clan consider as their ancestral homeland there is a shrine of Ayak. In the chaos created by the expulsion of Kolams from areas of reserved forest, these Ayak shrines remain the only focal points of clan unity, for all Kolams, unless totally detribalized, return to their ancestral Ayak shrine for the performance of important rites, when the living members of the clan are united in worship and the dead of the clan are propitiated with offerings. The care of each Ayak shrine is the responsibility of a clan priest whose office is hereditary in the male line. Once in every three or four years the symbols of an Ayak may be taken on a circuit and visit Kolam and Gond villages within a radius of twenty or even more miles. Ayak is considered a benevolent god, accessible to the prayers and offerings of

men. Though all Kolams emphasize the one-ness of Ayak, he is worshipped under different names derived from localities containing shrines of Ayak.

The Kolams are renowned for their skill in divination and the propitiation of locality gods. This reputation has led many Gond communities to entrust the cult of certain local divinities, and particularly of the gods holding sway over forests and hills, to the priests of nearby Kolam settlements, and it is because of this sacerdotal function of Kolams that Gonds refer to the entire tribe as Pujari.

Bibliography

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. "Tribal Populations of Hyderabad: Yesterday and Today." Census of India, 1941. Vol. 21. Hyderabad, 1945.

——. "The Cult of Ayak among the Kolams of Hyderabad." Wiener Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik 9 (1952): 108-23.

Russell, R. V. The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. Vol. 3. London, 1916. Pp. 520-26.

Naikpods

The wooded hills and secluded valleys of Adilabad District which were the habitat of the Kolams also served some groups of Naikpods as a refuge area, where until the 1940s they practised slash-and-burn cultivation with hoe and digging stick. Like the Kolams, whom they resemble in many respects, the Naikpods fell victim to the policy of forest reservation, and today only insignificant numbers of Naikpods live in hill settlements. Most of them are found in villages of the plains, where they work as tenant farmers or agricultural labourers. Few of them own the land they cultivate. They are scattered over a large area, and communities of Naikpods are found also in the districts of Karimnagar and Warangal. Naikpods originally had a language of their own which closely resembles Kolami, but today only a few small groups of Naikpods in the western part of Adilabad District and the adjoining taluks of Maharashtra still know this ancient tongue. The majority of the tribe speak Telugu as their only language and have largely been assimilated within the Hindu social order. They are regarded as a caste of low status but as superior to the polluting castes. Unlike the Kolams, the Naikpods have no institutionalized link with Gonds.

Bibliography

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Raj Gonds of Adilabad. London, 1948. Pp. 37-39.

Gonds

Among the tribal populations of India the Gonds stand out by their numbers, the vast expanse of their habitat, and their historical importance. No exact figures for the present size of the group of Gond tribes is available, for the census of 1961 was the last in which all individual tribes were enumerated. At that time 3,992,905 persons were returned as Gond, and there can be little doubt that by now the number of Gonds must long ago have exceeded the four million mark. Figures for the speakers of tribal languages are still being published, and in 1971, 1,548,070 Gondi-speakers were recorded. But this does not give an indication of the present strength of the ethnic group embracing the various Gond tribes, for more than half of all Gonds speak languages other than Gondi, such as Chhattisgarhi Hindi, an Aryan tongue which must have replaced the Dravidian Gondi.

The majority of Gonds are found today in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Their main concentrations are the Satpura Plateau, where the western type of Gondi is spoken, and the district of Mandla, where the Gonds have adopted the local dialect of Hindi. The former princely state of Bastar, now included in Madhya Pradesh, is the home of three important Gond groups, namely, the Murias, the Hill Marias, and the so-called Bisonhorn Marias, all of whom speak Gondi dialects. The states of Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh also contain substantial Gond populations, and the majority of these have traditionally been described as Raj Gonds, though in their own language they call themselves Koitur , a word common to most Gondi dialects. The term Raj Gonds , which in the 1940s was still widely used, has now become almost obsolete, probably because of the political eclipse of the Gond rajas. The rulers of Chanda, situated now in Maharashtra, were until 1749 powerful princes whose dominion included a large part of the Adilabad District of Andhra Pradesh. The rule of the Gond rajas of several princely states in Chhattisgarh lasted until 1947, when the British withdrew from India and the Gond states were merged with Madhya Pradesh.

There exists little accurate information on the early history of the Gonds, and it was not until Mughal times that Gond states figured in contemporary chronicles. But the ruins of forts ascribed to Gond rajas suggest that in past centuries the Raj Gonds did not live in the isolation typical of many other tribal communities but entertained manifold relations with other populations whose style of living their rulers imitated. Until comparatively recent times, a feudal system prevailed also in the highlands of Adilabad, and myths and epics depict the life of Gond chieftains who were not subject to any outside power. The Gonds were then already settled farmers who cultivated their land

with ploughs and bullocks. Land was plentiful, and individuals could freely move from one settlement to another. In the following chapters we shall see that this mobility has now come to an end, and with this the entire life-style of the Gonds has changed.

Gond society has both its vertical stratification and its horizontal divisions, and while with the decline of the raja families the stratification based on hereditary rank has been reduced in relevance, the division of society into exogamous patrilineal units has retained its importance. The basis of the social structure is a system of four phratries, each subdivided into clans, and the origin of this system is attributed to a divine culture hero. The members of each clan worship a deity described as persa pen ("great god"), and in some cases the shrine of this deity lies within the ancestral clan land. Today the clans are widely dispersed, but they still form a permanent framework which regulates marriage and many ritual relations.

Closely linked with each individual Gond clan is a lineage of Pardhans, bards and chroniclers, who play a vital role in the worship of the clan deity and many other ritual activities. The Pardhans, though themselves not Gonds and of a social status lower than that of their Gond patrons, are nevertheless the guardians of Gond tradition and religious lore. The recent deflection of their interests and energy to other enterprises will undoubtedly have an adverse effect on the preservation of Gond traditions.

A role similar to that of Pardhans is being played by another and much less numerous group of bards and minstrels known as Toti. These too have hereditary ritual relations with individual Gond lineages and act as musicians and story-tellers.

The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh, whose fortunes in recent years are the subject of a large part of this book, are only one of the many sections of the Gond race, and differ in cultural characteristics from the various Gond groups inhabiting the hill country of Bastar, which lies due east of Adilabad.

The Gond tribes of Bastar are themselves by no means uniform. The Hill Marias, a population of some 15,000 concentrated in the Abujhmar Hills, are slash-and-burn cultivators, and their agricultural methods resemble those of Konda Reddis and Kolams. Each group occupies a territory within which its members shift their settlements as well as their fields every few years, returning after some time to the same village sites. A few communities of Hill Marias have moved across the state boundary into the Bhamragarh region of Chandrapur District. Those who live in the high hills continue their traditional way of life, but in recent years quite a number have migrated to lower ground. There they have learnt plough cultivation from the local plains people, and now grow rice on rain-fed fields.

Hill Maria woman with extensive face tattoo wearing a hollow necklace

of white metal and silver ear-rings.

Hill Maria girl wearing silver nose-studs and ear-rings, and several strings

of glass beads.

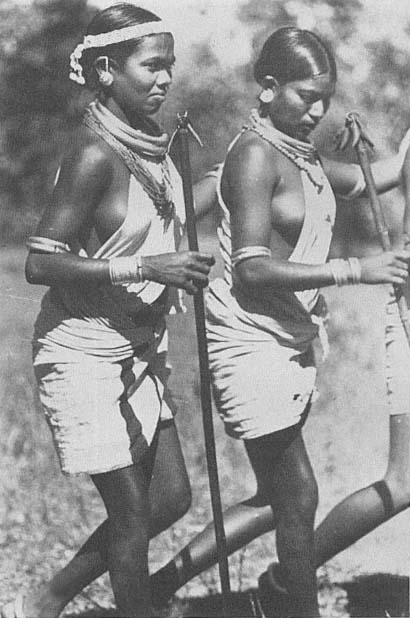

Bisonhorn Maria girls of Bastar during a dance, wielding sticks with rattles

attached; their necklaces and armlets are made of white metal.

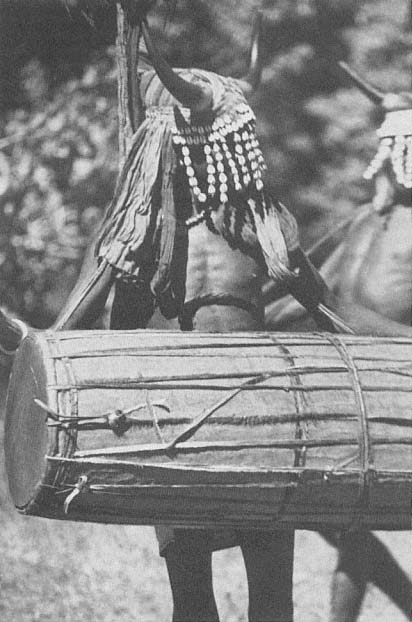

Bisonhorn Maria dancer with a mask of cowrie shells playing a large cylindrical drum.

Far more numerous than the Hill Marias of the Abujhmar Hills are the Dandami, or Bisonhorn Marias, with a population of over two hundred thousand, spread over a large part of Southern Bastar, including the hills of Dantewara, the forest lands of Bijapur, and the low country of the Kutru, Sukma, and Konta regions. The designation Bisonhorn Marias , which has become current in the ethnographic literature, is derived from a distinctive head-dress adorned with the horns of wild bison and worn at marriage dances. These Marias are more settled than the Hill Marias and farm their land in a manner similar to that prevailing among the Raj Gonds of Adilabad. Like the latter they have a cult of clan gods, each of whom is connected with a traditional clan territory. The system of phratries subdivided into clans, so characteristic of the Raj Gonds, extends also to the Bisonhorn Marias.

Distinct from Hill and Bisonhorn Marias are the Murias, a Gond tribe spread over an extensive region in Northern Bastar. The most distinctive feature of the Murias is the ghotul or youth dormitory, and it is due to this institution, reminiscent of the youth dormitories of the Oraons in Bihar and most Naga tribes, that the Murias have a special place in anthropological writings on Indian tribal societies. Their compact villages are distinguished by spacious houses more solid than the dwellings of most other Gond groups. Their principal crop is rice, cultivated on permanent fields, usually embanked and irrigated, but where level land is scarce they also practise slash-and-burn cultivation on hill slopes, and much speaks for the probability that this was the original type of tillage before the Murias acquired ploughs and bullocks. Today the Murias of the Narainpur Taluk are among the most prosperous Gond communities.

The Koyas, a tribal population largely, though not exclusively, concentrated in Andhra Pradesh, are the southernmost section of the great Gond race. Known also as Dorla Koitur, they merge on the southern border of Bastar with the Bisonhorn Marias, and some groups of Koyas, notably those in the lower Godavari regions, also possess bisonhorn head-dresses. In that area Koyas still speak a Gondi dialect, but the majority of Koyas have lost their own language and now speak the Telugu of their Hindu neighborus. In the districts of Khammam and Warangal, Koyas make up the majority of the tribal population. There they have suffered a fate similar to that of the Gonds of Adilabad District, in the sense that they have lost much of their best land, which they used to cultivate with ploughs and bullocks, and are largely reduced to the role of tenants and agricultural labourers. The process of detribalization has progressed further among Koyas than among any other Gond tribe.

Bibliography

Elwin, Verrier. Maria Murder and Suicide. Bombay, 1943.

——. The Muria and Their Ghotul. Bombay, 1947.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Raj Gonds of Adilabad. London, 1948.

——. The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh. Delhi/London, 1979.

Grigson, Sir Wilfrid. The Maria Gonds of Bastar. London, 1949.

Jay, Edward J. A Tribal Village of Middle India. Calcutta, 1970.

Rao, P. Setu Madhava. Among the Gonds of Adilabad. Hyderabad, 1949.

Saoras

The Saoras (also spelt Savaras ) are one of the principal Munda-speaking tribes and are widely spread over hill regions within Orissa, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal. Their main concentrations are in the Ganjam District of Orissa and the Srikakulam District of Andhra Pradesh, and their total numerical strength exceeds 450,000. There are cultural and economical distinctions between the various sections of this large autochthonous population, but Saoras are conscious of their ethnic identity wherever and in whatever conditions they live. Communities inhabiting rugged hill regions practise mainly slash-and-burn cultivation, using hoes as their main agricultural implements. In lower and more level country they use ploughs and bullocks, and they also terrace fields wherever the terrain lends itself to irrigated rice cultivation. Saora settlements are characterized by parallel lines of houses standing opposite each other in long streets. Many Saoras erect megalithic monuments, in the style of the menhirs and stone platforms of the Gadabas, another Munda-speaking tribe of Orissa also represented by a few small communities in Srikakulam District.

The Saoras' material standards are lower than those of such neighbouring tribes as the Jatapus, and they give on the whole the impression of considerable primitivity. Their ritual and religious life, on the other hand, is extraordinarily complex, and Saora shamanism, in particular, is based on very complicated ideas about the interrelations between men and spirits and the possibility of human beings entering the spirit world and closely associating with its denizens.

Bibliography

Elwin, Verrier. The Religion of an Indian Tribe. Bombay, 1955.

Mazumdar, B. C. The Aborigines of the Highlands of Central India. Calcutta, 1927.

Thurston, Edgar. Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. 6. Madras, 1909. Pp. 304-47.

Jatapus

In the hills of Srikakulam District, Jatapus live in symbiosis with Saoras, members of both tribes either dwelling in adjoining villages or sharing the same village site. As a rule Jatapus prefer the lower valleys where there is level land for wet rice cultivation, while the less fertile higher hill slopes are left for cultivation by Saoras. Although the Jatapus are held to have originally been a Kond subtribe, few of them speak a dialect related to Kui, the language of the Konds, and most have adopted Telugu as their only tongue. They are settled plough-cultivators and practise slash-and-burn cultivation only in localities where they do not have sufficient flat land for permanent cultivation.

Jatapus extend over several districts of Andhra Pradesh and the adjoining regions of Orissa. Their total strength exceeds eighty thousand.

Bibliography

Thurston, Edgar. Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. 2. Madras, 1909. Pp. 453-54.

Tribes of Arunachal Pradesh

The tribal populations of Northeast India, which will be discussed in chapter 11, belong racially, linguistically, and culturally to a sphere totally different from that of all the aboriginal tribes of Peninsular India, and their present political situation contrasts fundamentally with that of tribals in states such as Andhra Pradesh.

Arunachal Pradesh, the union territory previously known as the North East Frontier Agency, is a mountainous region extending between the Brahmaputra Valley, whose eastern part it encloses like a horseshoe, Tibet to the north, Burma to the east, and Bhutan to the west. With the Tibetan region of China it has a common frontier, from the Bhutan border eastward to the tri-junction of India, Burma, and China in the extreme northeast. The border with Tibet/China is about 1,000 kilometers long and runs along some of the highest mountains of the eastern Himalayas. Arunachal Pradesh occupies an area of 81,436 square kilometers (31,438 square miles), and the population at the time of the 1971 census—the latest available enumeration—was 467,511. This means that the average density of population per square kilometer is only 6, whereas the comparable figure for the whole of India is 178 and that for Assam, 153.

Arunachal Pradesh comprises ethnic groups of great cultural diversity, but in many respects there is an overall uniformity. All tribes are

of basically Mongoloid stock, and they all speak Tibeto-Burman languages. Many of these languages are not mutually understandable, but there are also large areas within which people can communicate by each speaking his own language, which is more or less understood by those speaking other dialects. British administration extended over only a small part of the present territory of Arunachal Pradesh, and the populations of large areas lived then in virtual isolation, although those of the northern border areas maintained occasional trade contacts with Tibet, while those of the foothills were dependent on some barter trade with Assam. Since 1947 strenuous efforts have been made to bring the entire territory under the effective administration of the Government of India, and in 1978 a democratic form of government based on universal franchise was introduced. Today Arunachal Pradesh has a legislative assembly and a cabinet of ministers consisting of members of this assembly.

The following ethnographic notes relate only to communities discussed in chapter 11, for in this context a description of all the tribal groups would serve no useful purpose.

Nishis

A large population of closely related tribal groups extends over the southern and western part of the Subansiri District and across its western border into the Kameng District. As long as little was known about the people of these districts, the members of this population were called Daflas, a name coined by the Assamese of the adjoining plains, which has the somewhat derogatory connotation "wild man." With the development of contacts between the people of the hills and those of the Brahmaputra Valley and particularly with the spread of education among the tribesmen, this term appeared objectionable to the people concerned, and they insisted on being referred to as Nishi, a term which is derived from the word Ni meaning "man." Today the name Dafla has been discarded and Nishi (or in relation to some groups Nishang) is used in conversation and all official publications, though some Assamese persist in their old habit of referring to the hillmen as Daflas. In the 1971 census 33,805 Nishis, 15,462 Nishangs, and 8,174 Hill Miris were counted, but it is not clear what criteria were used to distinguish between Nishis and Nishangs.

According to tribal tradition all Nishis are descended from one mythical ancestor by name of Takr, and it is also believed that his sons became the forefathers of three branches of the tribe, respectively known as Dopum, Dodum, and Dol. Each of these branches is divided into a number of phratries, which are exogamous units subdivided into several named clans. This system is spread over an extensive area,

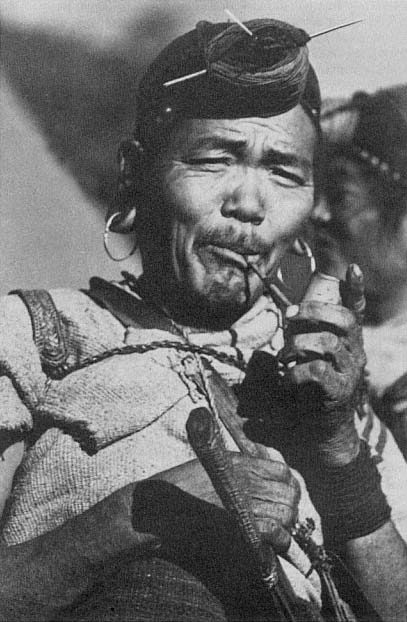

Nishi man of Jorum village. Cane hats and hair-knots pierced by a brass pin are

part of the traditional Nishi attire, and served as protection as well as decoration.

Miri woman of the Raga Circle. The disks worn in the ear-lobes are made of silver;

the necklaces are partly of glass beads and partly of more valuable stone beads.

Nishi war leader speaking during peace negotiations to end a long-standing

feud in 1944.

and there are few men whose knowledge of its ramifications extends further than their own phratry. Though the Nishis' mobility is high and there is evidence of extensive migrations, it appears that the three major branches and also some of the phratries had at one time a regional dimension.

But neither phratries nor clans are political units, nor in traditional Nishi society did the members of a village cooperate in the pursuance of political aims. We shall see in chapter 11 that in recent years there have been considerable changes in the system of social control, but in the conditions which prevailed until well into the 1940s (in many remote areas, into the 1950s and even the 1960s) the primary social unit was the household. Most Nishis lived and still live in long-houses comprising several families. It is only the members of such a giant household who have the duty to support each other in any dispute with outside adversaries, for Nishis lacked a tribal organization capable of maintaining law and order.

The instability of Nishi society was linked with the system of land tenure. As no one had individual rights to land and the inhabitants of a settlement were free to cultivate wherever they chose, wealth could not be invested in land, and movable possessions, be they cattle or valuables, were liable to fall into the hands of powerful opponents. A

Nishi men discussing the terms of a peace settlement.

concomitant of the general insecurity and frequency of armed hostilities was the distinction between free men and slaves. The latter were mainly people captured in war and either kept by their captors or sold. Their children became members of their owner's clan, but their status was that of dependents rather than slaves, and in time they could gain their freedom and acquire property. Thus there existed among Nishis no permanent slave class, barred for all time from a rise in social status.

Like most other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, the Nishis were traditionally slash-and-burn cultivators. They cleared the forested slopes lying at altitudes between one thousand and six thousand feet and grew rice, millet, and pulses on these hill fields. Hoe and digging stick are their principal agricultural implements, and though they breed cattle, particularly mithan (Bos frontalis) , they use neither the plough nor any form of animal traction. In recent years, however, the cultivation of rice on permanent, irrigated fields has been introduced in many villages possessing some level land, and this change in agricultural methods has caused economic as well as social changes.

Barely distinguishable from the Nishis of the western part of Subansiri District is a tribal group about 8,200 strong officially referred to as Hill Miris, which is settled in the hills to both sides of the lower

course of the Kamla River. The two groups merge and overlap, and any line drawn between them would be entirely arbitrary, for there is no bar to intermarriage and many so-called Hill Miris describe themselves as Nishis when speaking their own language.

Equally blurred is the distinction between the Nishis of the upper Kamla Valley and the tribes living to the north of that area and spreading into the Sipi Valley and that of the upper Subansiri. They are usually referred to as Tagin, but as so far no anthropological research has been done among this ethnic group, little information of an ethnographic nature is available.

In the Kameng District the people identical with the Nishis of the Subansiri District but separated from them by a high though not impassable mountain range are known as Bangni. Their life-style is similar to that of the Subansiri Nishis, and in the days before the establishment of Indian administrative control they were as warlike as their eastern fellow-tribesmen and used to terrorize the less martial local tribes.

Bibliography

Bower, Ursula Graham. The Hidden Land. London, 1953.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. Ethnographic Notes on the Tribes of the Subansiri Region. Shillong, 1947.

——. Himalayan Barbary. London, 1955.

Pandey, B. B. The Hill Miri. Shillong, 1947.

Shukla, B. K. The Daflas of the Subansiri Region. Shillong, 1959.

Apa Tanis

Whereas Nishis, Hill Miris, and other related groups merge imperceptibly one into the other, there is one people, known as Apa Tani, which constitutes a separate endogamous community with its own territory, language, customs, and traditions, and an economy fundamentally different from that of all other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. In a single valley with an area of approximately fifty-two square kilometers, close to 13,000 Apa Tanis live in seven villages ranging in size from 160 to 1,000 houses. The fact that roughly 300 tribal people can make a living on one square kilometer would be unusual anywhere among primitive subsistence cultivators dependent on their own resources, but in an area where no other tribe had until recently any idea of intensive cultivation, the achievement of the Apa Tanis is truly astonishing. Both Nishis and Apa Tanis are agriculturists, but their systems of cultivation differ fundamentally. While the Nishi slash-and-burn cultivator seldom tills a piece of land more than two or three years in succession, the Apa Tani tends every square yard of his land

with loving care and the greatest ingenuity. Until the economic revolution of recent years, land was to him the source and essence of all wealth, and only the possession of land gave a man material independence. All cultivated land is jealously guarded property, and good irrigated fields fetch prices that in the plains of Assam would be considered fantastic. Rice cultivated on irrigated terraced fields is the Apa Tani's main crop, but on dry land millet, maize, potatoes, and vegetables are grown. All cultivation is done with iron hoes, digging sticks, and wooden batons, for not only were ploughs unknown in the past, they also failed to gain acceptance in recent years when Apa Tanis eagerly took to bicycles and other products of modern technology.

While most Nishis live in dispersed settlements, the Apa Tanis dwell in crowded villages where hundreds of houses stand eave to eave in long streets and narrow lanes. The villages are divided into wards, and each of these contains several exogamous clans. The villages are administered by councils of elders, but there has never been any overall authority controlling the entire tribal community or determining its relations with neighbouring Nishi villages.

A characteristic feature of Apa Tani society is its rigid stratification. There are two classes differing in status: an upper class whose members own the larger part of the land and wield political power in clan and village, and a lower class which used to consist of free men owning their own land as well as of domestic slaves. The latter have now been freed, but the endogamy of the classes persists, though nowadays it is occasionally breached.

Priests and shamans maintain communications with the world of gods and spirits, whom they propitiate with animal sacrifices and food offerings. There is a strong belief in an underworld, where the dead lead a life resembling in all details life on earth.

Bibliography

Bower, Ursula Graham. The Hidden Land. London, 1953.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Apa Tanis and Their Neighbours. London, 1962.

——. Morals and Merit--A Study of Values and Social Controls in South Asian Societies. London, 1967.

——. A Himalayan Tribe: From Cattle to Cash. Berkeley and Los Angeles/New Delhi, 1980.

Khovas

The Khovas are a small tribe of slash-and-burn cultivators inhabiting ten villages in the Bomdila Circle of Kameng District. In their own

language they call themselves Bugun, but this name is not used by any of their neighbours. Their social organization is based on a system of exogamous clans distributed over all the ten villages. The tribe is strictly endogamous, and there is no intermarriage with any neighbouring tribe, such as the Akas and Mijis, whose life-style is similar, or the Sherdukpens, with whom the Khovas have long-standing ritual and economic relations. Though the Khovas' traditional religion consists of the worship of numerous deities and nature spirits, which involves sacrifices of cattle, they are now influenced by Tibetan Buddhism and have begun to employ lamas for the performance of rituals. The Khovas used to have trade relations with Monpas as long as the latter were in a position to trade with Tibet. In the 1971 census only 703 Khovas were returned, but this may be an underestimate due to the fact that the small community is known under different names.

Bibliography

Elwin, Verrier. Democracy in Nefa. Shillong, 1965. Pp. 77-80.

Sherdukpens

The small tribe of Sherdukpens, numbering about 1,600 souls, inhabits a single valley of the Kameng District, where most of the population is concentrated in the two principal settlements of Rupa and Shergaon, each of which has several satellite villages. In their own language the Sherdukpens refer to themselves as Senji-Thonji, but the neighbouring Monpas call them Sherdukpen, and this name has been adopted in official records. According to local tradition the Sherdukpens are the descendants of a Tibetan prince and his followers who came originally from Beyalung in Tibet and first settled in Bhut, a village near Dirang Dzong, where the ruins of their first fort are still standing. Like Apa Tani society the Sherdukpen community is divided into two unequal and endogamous classes, known as Thong and Tsao, each of which comprises several exogamous clans. The Thong class is supposed to be descended from the legendary princely ancestor, whereas the inferior Tsao class stems from his attendants who immigrated at the same time. The Sherdukpens have long-standing political and trade relations with the plains people of Assam, and in one locality on the fringe of the plains there is still an area of 103 acres which is under the control of Rupa and serves as the site of an annual festival celebrated jointly by Sherdukpens and Assamese. Similarly, people from Assam send gifts to support the celebration of a festival at Rupa. The tribal god worshipped at this festival has no connection with Buddhism, and the priests ministering at the rites are local men elected by the people of Rupa. Yet, there is in Rupa a large Mahayana gompa deco-

rated in a style influenced by Bhutanese and Tibetan prototypes. Like many populations on the periphery of the Tibetan culture sphere, the Sherdukpens practise two religions: an old tribal cult as well as Mahayana Buddhism. The Buddhist rituals are performed by lamas who are of Bhutanese origin or have been trained in Bhutan.

The Sherdukpens have some level land which they plough, using crossbreeds of mithan and ordinary cattle for traction. On hill slopes they practise shifting cultivation in the same way as Khovas and many Monpas.

Bibliography

Sharma, R. R. P. The Sherdukpens. Shillong, 1961.

Monpas

All along the northern border of Arunachal Pradesh there are populations influenced by Tibetan culture or of Tibetan origin. In Kameng District, a population of 23,319 Monpas was returned in the 1971 census, but it seems that 1,716 Dirang Monpas, 1,046 Lish Monpas, and 826 Tawang Monpas listed separately are not included in that number. However this may be, in the Bomdila and Tawang subdivisions Monpas form the majority of the population. All of them speak languages akin to Tibetan, but not all of the local dialects are mutually understandable. Yet, culturally the various groups of Monpas have much in common. They differ fundamentally from such non-Buddhist tribes as Bangnis (as the Nishis are called in Kameng), Akas, Mijis, and Khovas, but share the Buddhist heritage of the Sherdukpens.

Most Monpas are high-altitude dwellers, and their economy has far more in common with that of such Himalayan populations as the northern Bhutanese or most Bhotias of Nepal then with the economy of most tribal groups in Arunachal Pradesh. For the cultivation of their level land they use ploughs and bullocks or yak-hybrids, though here and there they also practise slash-and-burn cultivation on hill slopes too steep for ploughing. Barley, wheat, and buckwheat are their main crops, though in sheltered valleys at an altitude below eight thousand feet rice is also grown. Monpa society is divided into several strata of different social status, but there is no developed system of exogamous clans comparable to that of Nishis, Khovas, or Sherdukpens.

Buddhist beliefs and traditions dominate cultural life, and monasteries and nunneries play an important role in the fabric of Monpa society. But side by side with Buddhist institutions there persists a cult of tribal deities conducted by priests who are openly described as representing an old religion related to the Tibetan pre-Buddhist Bon faith.

It is this coexistence of Buddhism with tribal religions which suggests the possibility of a fertilization of local cults by the more sophisticated ideology of Mahayana Buddhism, which was at one time the mainspring of Tibetan civilization.

Anthropologists concerned with India have for some time debated the problem of the distinction between autochthonous tribal groups and Hindu castes. Those speaking of a tribe-caste continuum hold the view that it is impractical to draw a sharp line between tribes and castes, whereas others feel confident of their ability to decide in concrete cases whether a given community should be classified as a tribe or a caste.

The notification[1] of tribal groups as "scheduled tribes" by the Indian Parliament clarifies, in most cases at least, the legal position. Yet there remain borderline cases. Political reasons may motivate a state government to include a particular community in the list of scheduled tribes, whereas in a neighbouring state more resistant to pressure groups the same community may not be notified as a scheduled tribe, and hence may not enjoy the privileges granted to kinsmen on the other side of the state boundary (see chapter 8). Insofar as the tribes included in the foregoing list are concerned, there can be little doubt that they deserve the politically advantageous classification of scheduled tribes.

In Arunachal Pradesh the notification of an ethnic group as a scheduled tribe is not of great relevance because in this union territory tribals constitute the majority of the population and power lies in their hands. It becomes important only for those tribesmen who pursue studies or a career outside Arunachal Pradesh and benefit from the reservation of a percentage of places in universities as well as of jobs in government service for members of notified tribal communities. In Andhra Pradesh, the autochthons are now a minority, even in areas where not long ago they constituted the main population, and the privileges granted to scheduled tribes play a vital role in their struggle for economic and cultural survival.

[1] Notification is a legal term used in India—as in other previously British territories—for the promulgation of laws and government ordinances in the official gazette. Tribes notified as belonging to the "scheduled tribes" and notified tribal areas are those whose special legal status was established by a "notification" in the government gazette.