The Legacy of Group f.64

Many factors, including the departure of several members from the Pacific Coast and Carmel, caused Group f.64 to break apart.[51] Weston went to Santa Barbara to be with his son; Willard Van Dyke (Fig. 100) left for New York and a career making movies (beginning with The River ). Although Mary Jeannette Edwards stayed at 683 Brockhurst, it is clear that she felt deserted. Returning some prints to Weston, she remarked in a letter, "I think the only course open to the group is not to show as f.64, but as a group of Western Photographers. There is such diversity in work and point of view."[52] In August 1935 she added, "Now I realize that my little 683 must be given up, as soon as I am economically able to make the move."[53]

Did the photographers who continued to be active evolve new ways of seeing and composing their photographs? Or did their increasing fame rest on the growing understanding of the general and museum-going public that photography, the pervasive language of the times, was uniquely significant? Ansel Adams evolved as a photographer, building on his extraordinary vision and technique, his passionate feeling for California land, and his ability to enlarge the meaning of landscape photography as central to environmental concerns. Weston applied his straight photography to a broader landscape on his Guggenheim trip and, in a darker view, to the final pictures of Point Lobos, but illness overcame him before major change could develop and be resolved in his work. The photographs he showed at the f.64 exhibitions constituted, as he thought, many of his most successful pictures.

Group f.64 provided a rallying place for like-minded photographers to gather, state their aims, and exhibit their carefully composed black-and-white images (Fig. 101) in defiance of the then reigning pictorialist tradition. That the proponents were young, bold, and optimistic about their chosen medium was important to the group's success. As an informal Oakland meeting place and gallery, 683 Brockhurst encouraged the

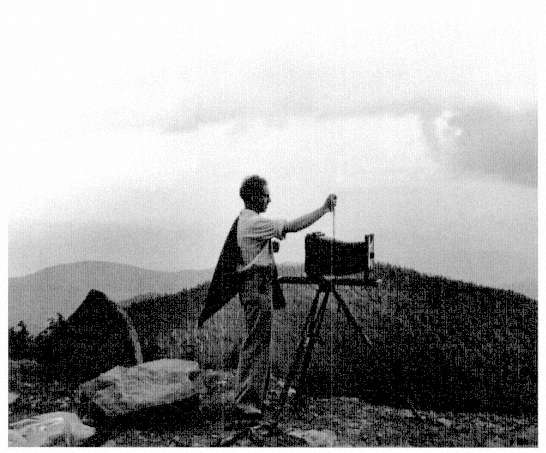

Figure 100

Peter Stackpole, Willard Van Dyke with View Camera , 1930s.

The Oakland Museum, gift of Douglas Elliott. Photograph courtesy Peter Stackpole.

revolutionary Bay Area modernist aesthetics that resulted in straight seeing and "pure photography."

Individually, four f.64 members combined their shared vision, adapting straight, clearly seen images for diverse purposes, from picturing California's stark beauty to addressing social issues. More remarkable, from this group of eight, four of the best-known and most celebrated photographers of the period emerged—Edward Weston, Willard Van Dyke, Imogen Cunningham, and Ansel Adams. One can postulate that although each of them was committed to making photographs, their collaborative effort, their entwined relationships, and their spirit of rebellion clearly benefited the

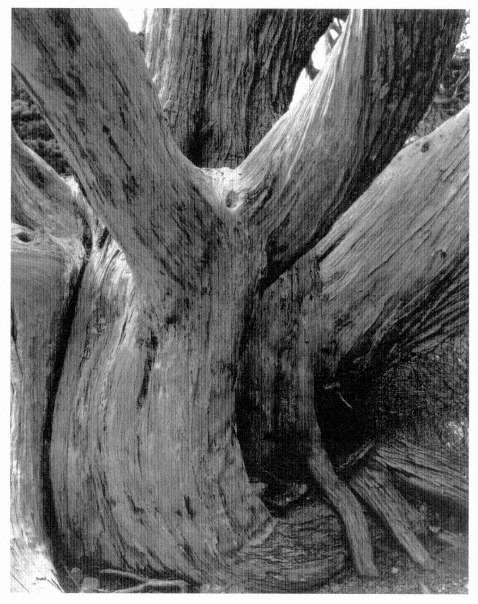

Figure 101

Sonya Noskowiak, Cypress, Point Lobos, Carmel, California , 1938.

The Oakland Museum, Photography Fund purchase.

younger members. The f.64 photographers gave an intriguing name and a specific location to a modernist movement that for the next forty years characterized American fine art photography. Cunningham captured the irony of their love of photography with humor and a determination to undermine pompous aims when she observed, "You have to be really crazy to stay in it, the way a photographer is treated . . . .You really have to be a mad person to stick to it. We did all seem to stick."[54]

Despite the pervasive and elegant modernism of a photography grounded in seeing straight and in a purist's modernist idiom, younger photographers changed, experimenting by revisiting mixed media and by striving for pictorial effects in their work. Perhaps manipulation, hand-coloring, and collage—all despised by the modernists of the 1930s—came to be acceptable once more as natural to artistic expression. Modernism in California first narrowed its focus to the purely photographic and then, by the 1950s, broadened it once more to encompass the wide range of media and images that could be imposed on paper.