PART 1

GENDER IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

2

Gender, Prestige, and Political Economy in the Nineteenth Century

Malays have a high sense of personal honour; and as in the interior the necessary weapons for avenging an insult are always carried about their persons, the outward deportment of natives to each other is remarkably punctilious and courteous. Europeans, particularly sailors, not aware of this sensitiveness, were formerly in the habit of trespassing upon it by practical jokes, but soon found that inexperienced persons playing with edged tools are liable to have their fingers cut.... To wipe out a stain on his honour by shedding the blood of an offender, even if assassination be the means employed, is accounted as little disgraceful by him as the practice of duelling by others in civilized Europe.

T. J. Newbold, Political and Statistical Accounts of the British Settlements in the Straits of Malacca (1839)

The approach developed in this and subsequent chapters is informed by recent work on gender and prestige. In particular, it builds on Ortner and Whitehead's (1981a) demonstration that cultural constructions of gender and sexuality are most profitably analyzed as comprising hierarchies or systems of prestige or status (social honor, social value); and that the logic and social and cultural entailments of gender systems are keyed to—and in important ways determined by—the workings of the most encompassing systems of prestige in the societies in which they are found (see also Collier 1988; Atkinson and Errington 1990; Kelly 1993).[1] The first section of the chapter provides an overview of prestige, kinship, and political organization in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. Of primary interest here are data bearing on the criteria for allocating prestige, and the prestige considerations of the political elite, especially their concerns with what I refer to, following Errington (1990), as spiritual power or "potency." Of broader analytic relevance are the links between the systems of prestige, kinship, and political organization on the one hand, and the structure of marriage and affinal relations on the other, and the ways

in which (untitled) in-marrying males were pressed into the service of generating property rights, wealth, and prestige for their wives' kin. The second section of the chapter deals with contrasting representations of marriage and affinal exchange, which I analyze by employing a modified version of Bourdieu's (1977) distinction between "official" and "practical" kinship. I demonstrate that while official representations of the system of marriage and affinal exchange portrayed the system as focusing on men's exchange of rights over women, practical representations depicted the system as focusing on women's exchange of rights over men. In the third and final section of the chapter, I argue that the practical system of representations was more in keeping with everyday practice in the nineteenth century. I also address some of the comparative and theoretical implications of the system, including the importance of reassessing the widely held position that institutions of kinship and marriage (e.g., the "exchange of women") constitute the ultimate locus of women's secondary "status" vis-à-vis men. I suggest that prestige differentials between men and women were rooted in cosmological views that accorded men more spiritual power and potency than women, and that these broadly grounded views—rather than institutions of kinship and marriage—lay at the heart of women's secondary "status."

Before turning to a discussion of nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan, two caveats are in order, the first of which is that my references to "the nineteenth century" pertain specifically to the period 1830–80. Many aspects of the reconstruction presented in the following pages are applicable to Negeri Sembilan during the post-1880 era, and are probably relevant as well to the decades immediately prior to 1830. My decision to focus on the period 1830–80 is based partly on the limited availability of sources on the pre-1830 era; it also reflects a concern to avoid delineating the impact of British colonialism (which was introduced into some areas of Negeri Sembilan as early as 1874) in the initial sections of the chapter. The local effects of colonial rule are discussed in subsequent chapters and elsewhere (Peletz 1987b, 1988b).

The second caveat is more in the form of a warning to the nonspecialist about the language employed in this chapter and some of the conceptual and analytic issues addressed here. This chapter is the most technically daunting in the volume as a whole, and my treatment of various issues (bearing on "official" and "practical" kinship, marriage and affinal relations, the exchange of men, and the like) will undoubtedly strike some nonspecialist readers as highly detailed, rather abstract, or both. Suffice it to say that the technical material is deeply important since it provides the

basis on which we can evaluate and challenge some of the most widely held theoretical views on women, kinship, and marriage; that many of these views are packaged abstractly; and that engaging them and laying the foundations for new theoretical orientations thus requires descriptions and analyses that incorporate some degree of technical and abstract discussion. Uninitiated readers who proceed with patience are likely to find their efforts rewarded, and will, in any case, see that subsequent chapters focus more directly on case studies and other discussions of real people and are for these and other reasons more accessible.

Prestige, Kinship, And Political Organization

Malays and other Southeast Asians are intensely concerned with prestige and status.[2] The intensity of prestige and status concerns in Southeast Asia is well documented in Leach's (1954) work on the highlands of Burma and Volkman's (1985) study of the Toraja (Sulawesi), though it is perhaps best illustrated in Geertz's (1973) analysis of the Balinese cockfight. The Balinese cockfight is a ritual dramatization and "celebration of status rivalry" which underscores that "prestige is the central driving force in society" (1973:43, 60), and that status relationships are matters of life and death. Cockfights, and the gambling associated with them, are by no means confined to Bali. They have long occurred throughout the Malay Peninsula (Newbold 1839 II:179, 183; Gullick 1987:330–32, 344–45) and other parts of Southeast Asia, as have myriad other contests and amusements which, at least in times past, frequently ended in the shedding of human blood (Reid 1988:143, 183–91).

The Malay terms that most closely approximate the meanings of the English terms "prestige" and "status" are pangkat and taraff. Pangkat denotes rank, degree, standing, position; rank or grade in a career. (Sepangkat refers to being of the same rank, social position, grade, degree, or age; berpangkat to having a rank, position, or grade; being noble, distinguished.) Taraff denotes social rank or standing, status, position in a society, standard of living. The two terms are frequently employed as synonyms, though pangkat is, at least at present, the more commonly used of the two terms.

In the nineteenth century there were various criteria that were used to allocate and claim prestige: descent, age, birth order, religious knowledge and experience, spiritual power or potency, and wealth were the most common. Each of these criteria may be seen as the axis within a particular system of prestige, though it is important to note that these systems were

not equally valorized. Some were more significant than others in the sense of being more encompassing and hegemonic. This is clear from the following observations of Newbold (1839 II:124), which pertain specifically to Malays in the Rembau district of Negeri Sembilan, but which are relevant to Malays elsewhere as well.

Although the Malays, like the Greeks and Romans, entertain the highest veneration for old age, still the claims of descent supersede those conferred by years , particularly with regard to the heads of tribes [i.e., clans], who take precedence in the councils of the state, conformably to the rank of the ... [clan] they represent. (emphasis added)

Newbold (1839 II:124) goes on to describe a ceremony he observed in 1833 that involved

a boy, whose dress and weapons betokened some rank, and to whom a considerable degree of deference was shewn by the natives. On inquiry I found him to be the ... [leader] of the principal ... [clan]; and that, although a younger brother, he had been elected ... to that dignity, in consideration of his elder brother's imbecility. This boy affixed his name, or rather his mark (for neither he nor any of his seven compeers could write) immediately after the Penghulu [District Chief] of Rumbowe, before the rest of the ... [clan leaders], some of whom were venerable old men, and grown grey in office.

The most encompassing and hegemonic system of prestige in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan was the system of hereditary ranking or descent (keturunan ) which was encoded in the political system, and which operated through the kinship system. The kinship system was composed of matrilineally constituted descent units, such as dispersed and localized clans (both referred to as suku ), lineages (perut ) and lineage branches (pangkal ).[3] Clans and lineages were ranked relative to one another and had their own political leaders, who, along with the District Chief (variously referred to as Undang, Penghulu , or Penghulu Undang ), constituted the formal leadership of the (political) system. The relative status of these leaders was, in theory, fixed, and depended largely on the relative status of the kinship and territorial units over which they presided. The heads of dispersed clans, for example, were ranked in relation to one another on the basis of the ranking of their respective dispersed clans, each of which was defined, partly through mythic charters, either as a "gentry" or "commoner" clan, or as a "dependent" (satellite) clan of one or another gentry group. In practice, however, the relative status of political leaders also depended on how well they worked the system of political patronage

to attract supporters and dependents and otherwise build up their nama ("names," "reputations").

As in other parts of the Malay world and Southeast Asia as a whole, building a name for oneself presupposed the accumulation and display of invisible spiritual power or "potency" (kesaktian, kekayaan, ilmu, kuasa ).[4] outward signs of which were large numbers of followers and substantial wealth (see Skeat [1900] 1967:81; Milner 1982:130 n.5; Gullick 1987:48; Anderson 1972; Wolters 1982; Reid 1988:120, 125–27; Errington 1990). Political leaders at all levels of the hierarchy sought to bolster their claims to spiritual potency and thus build their names primarily by gaining control over human resources (only secondarily by acquiring land). They amassed supporters and dependents in a number of ways: through military campaigns; through various forms of "adoption"; and by attempting to use their female relatives—especially their sisters and their sisters' daughters—as "bait" (to use Ortner's [1981:371] term) to attract and gain control over men, who, as in-marrying males, would ideally add property rights, wealth, and prestige to the kinship and territorial groups over which political leaders presided. My reference to women as "bait" is not meant to suggest that women were pawns in the status games of men; as I discuss further along, it is arguably more appropriate (assuming we can speak of pawns) to suggest that untitled men, not women, played this role.

Political leaders were typically males, but one should not conclude from this fact—or from the existence of a gendered division of labor—that there were radical prestige differentials or other pronounced inequalities between men and women. As in the nineteenth-century Malay world generally, women were not really viewed (or treated) as inferior to men (Gullick 1987:210), though for reasons noted below they were accorded somewhat less prestige and were likewise regarded as more vulnerable than men. Men's and women's roles and activities were viewed in terms of complementarity rather than hierarchy, as is clearly the case at present. Thus, men were accorded the primary role in matters of statecraft, formal politics, diplomacy and warfare, and in extralocal trade; they also assumed the major role in the production of metals used for tools and weapons, and thus effectively monopolized production of the means of violence. In addition, men performed much of the labor involved in household construction as well as the heavy labor of clearing forest and other land for residential and agricultural purposes. Women, for their part, engaged in fishing and surface mining (as did men), performed most of the tasks associated with rice production, and were primarily responsible for mak-

ing cloth, for processing foodstuffs, and for everyday cooking as well as the preparation of food for ritual feasts. Women also predominated in childcare and in the exchange of rights over children (informal child transfers). In these and other ways they exercised considerable autonomy and social control, acquired prestige, facilitated the acquisition of prestige on the part of their male kin, and helped maintain and reproduce households and the larger kin groupings and social units of which these households were a part.

The spheres in which men moved were more extensive and inclusive in a physical or territorial sense than the spheres of women and did in fact encompass women's spheres, though it should be noted that women were not subject to strict seclusion or segregation and did not wear veils (Newbold 1839 1:246). Whether men's activities were for this reason alone viewed as more directly related to universalistic concerns or "the social good"[5] is difficult to say (there are no data on the subject), though this is arguably the case at present. What is clear is that Western notions of the universality of "public" and "private" domains—and the attendant universalistic assumption linking men with the public domain and women with the private—do not fit comfortably with the situation in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. True, women were more directly associated with matters of the household than were men, but their activities clearly transcended the domains of household, as well as those of lineage and clan. Women's predominance in rice production was clearly seen as a public and not simply a private activity; so, too, was their centrality in marriage and affinal exchange, funerary ceremonies, and spirit cults.

It merits remark as well that women could and did assume the roles of midwife (bidan ) and healer (dukun ). They could also become shamanic specialists (pawang ) and thus find themselves in the critically significant position of being responsible for mediating relations of metaphoric kinship between the realm of humans and the worlds of nature and spirits. In some parts of Negeri Sembilan, moreover, women held political office (Lister 1887:88; cf. Lewis 1962:44–45). Women's abilities to assume important ritual and political roles had counterparts elsewhere in the Malay world and in other parts of Southeast Asia both in the 1800s and in earlier times (Reid 1988), as was undoubtedly well known in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. More generally, women's involvement in the public domains of communal ritual and formal politics served to mute the cultural elaboration of prestige differentials between men and women (and males and females on the whole).

The situation described here should not obscure the fact that women's involvement in ritual and political activities during the nineteenth century was far more constricted than it had been in earlier times. During the early part of the period 1450–1680, women had been extremely active in communal rituals throughout much of Southeast Asia due in large part to the fact that their reproductive and regenerative capacities gave them "magical and ritual powers which it was difficult for men to match" (Reid 1988:146; Andaya and Ishii 1992:555–56). This had changed by the latter part of this period, however, due to the development in Southeast Asia of Islam and other "Great Religions" (especially Buddhism and Christianity), none of which "provide any textual basis for female participation in religious rituals at the highest levels" (Andaya and Ishii 1992:555). More generally, the highest ritual positions of the dominant faiths came to be reserved for males, who thus presided over communal rituals. Women's public ritual roles became progressively less apparent, and they were increasingly "relegated to the domains of shamanism and spirit propitiation. In the process, the status of the shaman, both female and transvestite, declined.... and women became the principal practitioners of 'village' as opposed to 'court' magic" (Andaya and Ishii 1992:555–56). In the Malay case, and throughout much of Southeast Asia, this gendered skewing of ritual (and political) activities was usually rationalized in terms of beliefs relating to spiritual (and/or intellectual) power or potency—that men's was greater or stronger than women's—as discussed later (see also Andaya and Ishii 1992:556–57).

Alam beraja

Negeri/Luak berpenghulu

Suku bertua

Anak buah beribubapa

Orang semenda bertempat semenda

Dagang bertapatan, perahu bertambatan

The realm/empire has a raja,

The district has a district chief,

The clan has an elder/clan chief,

People of the clan have clan sub-chiefs,

People who marry into a clan have relatives through marriage,

The stranger finds a place as the boat an anchorage.

Customary sayings or aphorisms (perbilangan ) such as the one reproduced here (which is cited by Hale 1898:53–54; Parr and Mackray 1910:98; other colonial scholar-officials; and contemporary villagers) provide a suc-

cinct overview of political relations in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. These relations were organized at the district (negeri/luak ) level, and were overseen by district chiefs. Some of these chiefs formed an unprecedented but largely ineffectual politico-military union in the 1770s, the titular head of which was styled Yang diPertuan Besar (He Who is Made Lord), though he was sometimes referred to as Raja (King). The Yang diPertuan Besar served in some respects like the sultans of other Malay states, one principal difference being that he had no real authority within districts in which there were Undang .[6]

The Undang sat at the apex of the (district-level) political hierarchy and was regarded by his subjects as God's Caliph or Vice-Regent (berkhalifah ) and as sacrosanct (berdaulat ). He served as the supreme arbiter and final court of appeals for disputes that could not be settled by lower ranking political figures, and he was vested with the right to invoke capital punishment (stabbing below the collar bone with a keris or dagger). The Undang also enjoyed the right to conscript (male) villagers for defense purposes, to make periodic demands on household labor and food resources, and to claim all illegitimate children born in the district (Parr and Mackray 1910:52). In addition, he was entitled to collect annual payments in kind from the proprietors of certain categories of land. The resources which he commanded in these and other ways were used partly to sponsor lavish feasts held in connection with coronation rituals, marriage, circumcision, and death, as well as Islamic holidays (e.g., the Prophet's birthday), all of which testified to the Undang's grandeur and largesse. Other resources were deployed in support of the Undang 's military campaigns, many of which were geared toward acquiring or maintaining control over river traffic and other extralocal trade routes, and thus generating the wealth and followers that were outward signs of his spiritual potency. In these and other ways (e.g., through the public display of ritual paraphernalia and certain styles of clothing forbidden on pain of death to all others), the Undang legitimated his claims to berkhalifah and berdaulat .

The Undang was the only person in the district who could legitimately maintain that he was God's Vice-Regent or Caliph, and that he had royal power, sanctity, or majesty (daulat ); but he was by no means the only person who could legitimately claim to have spiritual potency. Indeed, one of the central tensions in the system was that while the Undang could legitimately contend that he possessed qualitatively superior forms or concentrations of spiritual potency (manifested in daulat ), others (i.e., pretenders and other detractors) could counter with some justification that the Undang 's spiritual powers were at best quantitatively superior forms

of the mystical knowledge cum power (sakti, kesaktian, ilmu ) which was concentrated among certain classes of ritual specialists (shamans, healers, midwives), and which was at the same time broadly distributed (albeit in less concentrated or potent forms) throughout the population, especially among men. Moreover, since the external signs of invisible spiritual power were large numbers of followers and substantial wealth, pretenders and other adversaries needed only amass followers and wealth comparable to or greater than the Undang to render concrete their claims to have comparable or superior forms (or concentrations) of sakti/ilmu . And if they succeeded, through trickery or force of arms, in capturing the regalia or kebesaran (literally, things or symbols of greatness) of an incumbent Undang , they were all the more likely to prevail over him, particularly since the paraphernalia of office were suffused with the same sanctity that permeated the body of the ruler (Skeat [1900] 1967:36; cf. Andaya and Ishii 1992:547). Such was a dangerous undertaking, however, and could entail kena daulat , which Skeat ([1900] 1967:23–24) described as being "struck dead by a quasi-electric discharge of that Divine Power which Malays suppose to reside in the king's person ..., [and which] is believed to communicate itself to his regalia, and to slay those who break the royal taboos" (cf. Newbold 1839 I:223, II:193; Gullick 1958:44–45, 1987:35).

Compounding the dilemmas both for the Undang and for leaders at all levels of the political hierarchy was the fact that extensive involvement in the affairs of their subjects was inimical to the accumulation and display of the spiritual potency that was a sine qua non for any political office and for being a "big man" (orang besar ) or "man of renown" generally. Spiritual potency presupposed and had as one of its outward signs a high degree of refinement, detachment, and studied restraint—immobility was a sign of divinity (Gullick 1958:45)—all of which indexed not simply the predominance of "reason" over "passion" but also the divinely inspired cultivation of "reason" in the pursuit of the highest forms of knowledge and enlightenment (see Milner 1982). Concerns with the accumulation and display of spiritual power were thus partly responsible for the highly decentralized regulation of local affairs (and the attendant frequency of challenges to the authority of the Undang and other political leaders). Put differently, such concerns help explain why Malay political institutions did not entail "an exceptional concentration of administrative authority" and did not "consist in exercise of pre-eminent power" (Gullick 1958:44). Such concerns were, at the same time, one of the reasons much of the regulation of such affairs fell to women; for women were held to be less preoccupied than men with the accumulation and display of spiritual po-

tency, and, in any event, were assumed to have less developed spiritual capacities.

More broadly, the myriad restrictions on the Undang meddling in the affairs of his subjects without their express request for his intervention (see Parr and Mackray 1910:48, 58) were not merely "checks and balances that helped ensure the autonomy of lower-ranking officials and the untitled majority. They also helped secure the Undang's spiritual potency. More importantly, given the explicit links between the spiritual and general health of the ruler on the one hand, and the welfare of his subjects and the world as a whole on the other, these same restrictions helped guarantee the balance and well-being of the universe and all of its constituent elements (Skeat [1900] 1967:36; cf. Anderson 1972; Jordaan and de Josselin de Jong 1985).

Clan chiefs (lembaga ) occupied the next highest rung on the political ladder, and presided over dispersed clans (or territorially defined segments of them). Like the Undang , they were entitled to collect taxes of various kinds and to call upon the labor resources of the households within their jurisdiction. Similarly, they helped settle disputes among their kin, for which they received certain fees. Clan chiefs also enjoyed the rights to wear certain styles and colors of clothing that were denied to both lower-ranking figures and the untitled majority. These and other ritual prerogatives were highly valued, as was clan chiefs' knowledge of adat and ilmu , which was manifested in their eloquence, oratorical skills, and overall abilities to attract followers.

There were relatively few clan chiefs for any given (dispersed) clan. Partly for this reason, but also because of the indigenous construction of power, responsibilities for regulating a broad range of political affairs typically devolved on the immediate subordinates of clan chiefs, who were referred to as buapak or ibuapak , which I gloss "clan subchief(s)." These individuals exercised authority over the compounds of a localized clan (Lister 1887:45–46) and concurrently served to link village residents with extralocal political figures. Clan subchiefs also helped guarantee that the members of their communities received equitable treatment at the hands of clan chiefs, in much the same fashion as the latter effected a check on the activities of the Undang (see Parr and Mackray 1910:36–39).

Titled individuals occupying the lowest rung of the political hierarchy were also charged with promoting justice in accordance with adat and with increasing the likelihood that their immediate superiors did right by their relatives. These "big people among the kin" (orang besar dalam anak buah ) helped ensure that capricious, partisan, or extortionary behavior

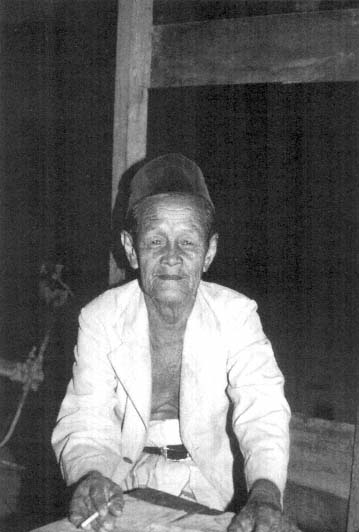

Figure 6.

Clan chief

Figure 7.

Male elder

on the part of subchiefs either did not occur, or, if it did occur, that it resulted in the appropriate punishment (Parr and Mackray 1910:34). In the latter instances, portions of the fine paid by a guilty subchief to the clan head were shared with the lineage heads, and apparently fines constituted the main source of income associated with the office. Lineage heads also received direct remuneration in the form of percentages of

the fees paid by male clan members in the village who were involved in "irregular marriages" (e.g., marriage by storm or abduction), although they were prohibited by adat from levying fines on their own accord.

Though I have spoken of "big people among the kin" as occupying the lowest rank of the political hierarchy, the customary saying cited earlier refers to yet another relationship of hierarchy or asymmetry: that between tempat semenda ([the place of] the wives' kin) and orang semenda (the people who marry in). This was clearly a political relationship; it was, moreover, the focus of considerable cultural elaboration. Some of the entailments of this relationship were encoded in the following perbilangan (cited in Hale 1898:57 and Caldecott 1918:36–37; cf. Parr and Mackray 1910:87, 116–17):

Orang semenda bertempat semenda.

Jika cherdik, teman berunding;

Jika bodoh, disuroh diarah,

Tinggi banir, tempat berlindong

Rimbun daun, tempat bernaung.

Orang semenda pergi karna suroh,

Berhenti karna tegah.

Jikalau kita menerima orang semenda;

Jikalau kuat dibubohkan dipangkal kayu;

Jikalau bingong disuroh arah,

Menyemput nan jauh, mengampongkan nan dekat;

Jikalau ia cherdik, hendakkan rundingan;

Jikalau maalim, hendakkan doanya;

Jikalau kaya, hendakkan emas;

Jikalau patah, penghalau ayam;

Jikalau buta, penghembus lesong;

Jikalau pekak, pembakar bedil.

Masok ka-kandang kerbau menguak;

Masok ka-kandang kambing membebak,

Bagaimana adat tempat semenda dipakai;

Bila bumi dipijak, langit dijunjong,

Bagaimana adat negeri itu dipakai.

Orang semenda dengan tempat semenda,

Bagi mentimun dengan durian,

Menggolek pun luka, kena golek pun luka.

The married man is guided by [moored/subservient to] his wife's kin:

If he is clever, they seek his counsel,

If he is stupid, they see that he works;

Like the buttress of a big tree, he shelters them,

Like the thick foliage, he shades them.

The married man must go, when he is bid, and halt, when he is forbid.

When we receive a man as bridegroom,

If he is strong, he shall be our champion;

If a fool, he will be ordered about

To invite guests distant and collect guests near;

Clever, and we'll invite his counsel;

Learned, and we'll ask his prayers;

Rich, and we'll use his gold.

If lame, he shall scare chicken,

If blind, he shall pound the mortar;

If deaf, he shall fire our salutes.

If you enter a byte, low;

If you enter a goat's pen, bleat;

Follow the customs of your wife's family.

When you tread the soil of a country and live beneath its sky,

Follow the customs of that country.

A bridegroom among his bride's relations

Is like a cucumber among durian fruit;

If he rolls against them, he is hurt;

And he is hurt, if they roll against him.

One might ask here, Which of the "bride's relations" would be most likely to "roll against" a bridegroom on a day-to-day basis? More generally, assuming in-marrying males experienced difficulties living up to the expectations of, or otherwise dealing with, their affines, were the difficulties they experienced primarily in the context of the relationships with their wives' male kin, their female kin, or some combination of the two? I am inclined to think that in-marrying males experienced most difficulty with their wives' female kin. This is largely because, at the local level, a man's female affines enjoyed considerable autonomy and social control. Let me sketch out the reasons for this.

A married man lived in or near his wife's natal compound, and thus with his wife's closest female kin, other in-marrying males, and unwed individuals associated by birth with his wife's descent and residential unit. Even though a married man fell under the formal jurisdiction of his wife's clan spokesmen, they did not live with him in the same lineage compound or even (necessarily) in the same hamlet or village; in a community settled primarily by a single exogamous clan, for example, they would reside in a separate village, as would his wife's brothers (and mother's brothers). Circumstances of this nature clearly limited the extent to which out-marrying men could exercise direct or indirect control over their sisters and their sisters' children and spouses, or even take part in relatively im-

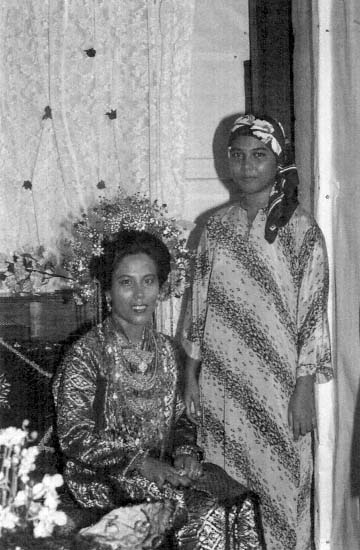

Figure 8.

Female elder

portant decisions bearing on resource allocation and the imposition of informal sanctions within the lineage or its households (as did, of course, temporary out-migration or merantau [see below]). This despite the fact that as adult male consanguines their role in the judiciary affairs of their lineage and its residential domain was theoretically preeminent.

A central issue here is that clans, lineages, and their component segments differed from the residential clusters of households representing them, and that women (especially female elders) exercised considerable autonomy and social control over the affairs of their natal households and compounds. This meant that the female elders of a lineage branch probably emerged as the de facto loci of authority (as clearly occurs at present), particularly since genealogical groupings below the level of lineage were not political units in the sense of having representative spokesmen assuming permanent titled offices. The implications of these facts are discussed elsewhere (Peletz 1987a, 1988b; see also chap. 3, below). Here I might simply point out that it was undoubtedly the activities and expectations of such women (rather than their male counterparts) that engendered many of the tensions experienced by in-marrying men owing to affinal demands on their loyalties and productivity.

In this connection it is especially significant that some of the customary sayings cited previously have been translated by early colonial-era scholar-officials as referring specifically to a married man's relationship with his mother-in-law , even though she represented but one of his in-laws or tempat semenda (see, e.g., Hale 1898:57; cf. Parr and Mackray 1910:87, 116–17). Such translations may well have been informed by scholar-officials' first-hand familiarity with the realities of local practice. This seems quite likely since individuals such as Abraham Hale, who served as the District Officer (Collector of Land Revenue and Chief Magistrate) for the administrative district of Tampin (which included Rembau), had many opportunities, and were in fact required, to gain first-hand knowledge of the workings of the local system. Be that as it may, Hale's (1898:57) commentary on the first of the texts cited above merits note.

One can imagine the satisfaction a Malay mother derives from thinking over this saying, and reciting it to her cronies and her daughter when she has made up her mind to receive a son-in-law into her family; be he sharp or slow, clever or stupid, either way she cannot be a loser. Her daughter's house will be built behind her own; if the man is clever he will get enough money to build the house by easy means; if he is stupid, she will so bully him that the poor man will be glad to labour with his hands at her bidding; it would seem to the anxious mother that she and her daughter cannot but be the gainers by this contract; perhaps they forget for the time that there is another side to the question, namely that they may have to pay his gambling debts.

Hale's remarks raise a number of issues worthy of further analysis, particularly since they might give the reader the erroneous impression

that we are dealing with a "matriarchal" society. I address such issues in subsequent sections of the chapter, which focus on various aspects of the system of marriage and affinal relations. Before turning to a detailed analysis of marriage and affinity, however, we need to consider a few other entailments of the political system, such as how one attained political office, and how competition among political leaders and "big men" generally informed local understandings and representations of femininity.

How Did One Get to Be a Political Leader?

Succession to political office was determined partly by ascriptive criteria in the sense that it was confined largely to males, and depended partly on being born into an appropriate kin group. Achieved status was also important, however, as we will see.

Rights to political offices were defined as the "ancestral property" (harta pesaka ) [ 7] of kin units associated with specific territorial domains. Succession to office rotated in theory among the units defined (through mythic charters) as eligible to furnish candidates for the office. For example, rights to the title of Dato Perba (the head of the Lelahmaharaja clan) rotated in theory between the four "founding" villages deemed eligible to provide candidates for this office. When the Dato Perba from village A died or relinquished his title, it was village B's turn to provide a candidate; next was village C's turn, then D's, then back to A, and so on.

The scheme of rotation was actually more complex than this, for in theory the different lineages comprising the Lelahmaharaja clan in village A took their turns in supplying candidates whenever it was their village's turn to provide someone for office. The same for villages B, C, and D.

There were no circuits beyond this, however, and there were no rules of primo- or ultimogeniture (or anything of the sort commonly reported for conical clans) specifying which male within a sibling set, lineage branch, or lineage merited preferential treatment when their kin group had its turn at providing a candidate for office. (This despite the importance attached to birth order in most other contexts.) Brothers and other males belonging to the same lineage thus competed with one another for the privilege of holding office, thereby giving rise to invidious intralineage cleavages in the very units they sought to represent. That many such competitions were fierce and frequently bloody is a common theme in the literature on the nineteenth century. More generally, the literature is replete with accounts of armed aggression and full-scale warfare between

men, kin groups, and larger territorial groupings linked to one another through siblingship (see Peletz 1988b).

Men thus competed with one another to attract supporters and dependents and otherwise build up their names. As noted earlier, this entailed developing and displaying spiritual potency, knowledge of adat , expertise in the recitation of the Koran and other religious texts—and eloquence and oratorical skills generally—as well as competence in economic activities (e.g., the collection and trade of forest products). Bear in mind, too, that the proceeds of economic activities were in many cases used to sponsor feasts that would not only impress supporters and potential supporters alike, but also enable them both to bask in the sponsor's majesty and to revel in the blessings of the various local spirits that were attracted to and pleased by such feasts.

Where did men seek followers? Men sought supporters both among their own kin and among affinal relations. Support from their own kin was necessary since, in theory, a man's succession to (and continued tenure in) office presupposed consensus on the part of his kin (male and female alike) that he was the most appropriate candidate for the office. Support from affines, especially male affines, was also highly advantageous. For the sake of convenience, male affines may be divided into two categories. The first (and for present purposes less important of the two) consisted of the wife's brothers and her other male matrikin. A man could seek political support and various types of assistance from such individuals, but he was constrained in doing so by the fact that he was ultimately beholden to them since he stood as their orang semenda (they were his tempat semenda ). The second (and for present purposes more important) of the two categories consisted of the men married to a man's sisters and sisters' daughters. The men married to a man's sisters and sisters' daughters were, both in theory and in practice, beholden to him since he was their tempat semenda (to whom they stood as orang semenda ). Of comparable if not greater significance, the labor power and productivity of such men helped create property rights, wealth, and prestige for the households and lineage into which they married and thus enhanced the names of all such groupings and members thereof. These, in short, were the male affines who were of greatest strategic importance to a man with political aspirations.

Let us assume, then, that men with political aspirations used their sisters and their sisters' daughters as "bait" to attract men who, as in-marrying males, would create property rights, wealth, and prestige for their kin groups. In what sense did they do this? First, they helped ensure

that their sisters and their sisters' daughters had at least respectable (and ideally, impressive) holdings of land and other property to bring to their marriages. And second, they guarded the virginity and moral standing of these women so as to enhance the likelihood that they commanded impressive marriage payments and were otherwise able to be matched as wives with men who not only had comparable or higher status, but also clear potential for contributing to their stores of property and wealth. In these ways they could ally themselves with prestigious clans or segments thereof. Some "beautification" rituals such as teeth filing may also be interpreted in a similar light (i.e., as attracting men) even though many such rituals did not occur until after marriage ceremonies were well under way.

Note, though, that men did not appropriate the labor power of their sisters or their sisters' daughters. Nor, for the most part, were they in a position to appropriate the labor power of the men married to these women. Not only did women retain control over the fruits of their agricultural and other labor; they also exercised important control over the labor power of in-marrying males. In short, we are not dealing with what Collier and Rosaldo (1981) refer to as a "brideservice society" (see also Collier 1988), or a situation in which, in the words of Lévi-Strauss (1949:115), "men exchange[d] other men by means of women."

Some Relational Features of Femininity

There is very little precise information on the ways in which femininity and female sexuality were experienced, understood, or represented in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. However, certain broad inferences can be drawn from the system of prestige outlined in the preceding pages. If we accept the proposition that the prestige considerations of the political elite were instrumental in motivating understandings and representations of femininity, then it seems reasonable to assume that, in relational terms, the category of "female" was dominated by understandings and representations of women in their roles as sisters and sisters' daughters, as opposed to, say, mothers and/or wives. To the extent that this was true, the gender system of nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan is similar to the gender systems of Polynesia, as described by Ortner (1981), and significantly different from the gender systems found in most other areas (e.g., Buddhist, Mediterranean, Catholic, and many Middle Eastern Islamic societies). In most societies, the category "female" is defined by female relational roles such as mother and wife, which serve to emphasize women's sexuality,

reproductive capacities, and links with "natural functions," and which in these and other ways effectively "pull women down."[8] In Polynesia, however, this does not really occur (or occurs on a much reduced scale), for the simple reason that the category "female" is, as noted earlier, defined primarily by women's roles as sisters and sisters' daughters. This is one of the reasons women in Polynesia enjoy "higher status" than women in most other societies (see Ortner 1981). Women in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan, for their part, also enjoyed "high status" relative to women in most other societies, and did so for much the same reason(s) as women in Polynesia.

The situation in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan both differed from and is more complex than that of Polynesia, however, for while the systems of kinship, prestige, and political organization in these two areas are in many respects quite similar, Negeri Sembilan has long been a Muslim society, whereas Polynesia has never been Muslim. More to the point, Islamic doctrines and cosmologies (like those of Buddhism, Christianity, and the other Great Religions) tend to focus on women in their roles as wives and mothers, rather than sisters and sisters' daughters. In these and other ways—most notably by emphasizing that women have less "reason" and more "passion" than men—Islam highlights women's sexuality, reproductive capacities, and links with natural functions. The fact that nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan was a Muslim society means that the "Polynesian features" of the system existed alongside and were in some contexts encompassed within a Muslim framework. (In other contexts, Muslim features of the system were encompassed within a "Polynesian framework.") Many but by no means all elements of these two systems were mutually inconsistent, which is to say that there were structural contradictions in the relations between the systems, and that, in relational terms, femininity was thus constituted of diverse heterogeneous elements whose cultural implications and social entailments were in many respects characterized by relations of structural contradiction as well. As we will see later on, some of these contradictions provided crucial structural precedents for historical changes during the period of British colonial rule (1874–1957).

Broadly similar types of contradictions characterized nineteenth-century constructions of masculinity. To understand the nature and locus of these contradictions—and the attendant challenges of masculinity—we need to look more closely at the ways in which in-marrying males were pressed into the service of generating property rights, wealth, and prestige for their wives' kin.

Marriage, Affinal Relations, and the Challenges of Masculinity: An Introductory Sketch

A man marrying into another tribe [i.e., clan] becomes a member of it. (Newbold 1839 II:123)

On marriage a man passes from his mother's [clan] to become a lodger in his wife's home.... A married man, by the fact of his marriage, is severed from his own [clan], which has no claims on him and no obligations toward him except in regard to "life and blood," so long as his married life continues. (Parr and Mackray 1910:86, 95)

A man passes on marriage from the control of his mother's [clan] to that of his wife's, so that a large proportion of the males in the charge of any one [clan] do not belong to that [clan] at all by descent. (Wilkinson 1911:316)

A man definitely passes into his wife's [clan] and becomes subject to her [clan] chief in all matters affecting her and her family.... He remains a member of his own [clan] for certain limited purposes but he is definitely subject to his wife's [clan] chief in all matters affecting her [clan].... The sole exception is the Undang . (Taylor 1929, cited in Winstedt 1934:78; emphasis added)

Nineteenth-century observers such as Newbold mistakenly assumed that, upon marriage, men were incorporated into their wives' descent groups. Later observers, such as Wilkinson, had a more accurate understanding of the system. In-marrying males were not actually incorporated into their wives' descent groups in any formal or legal sense; for example, although postmarital residence was uxorilocal, men did not change their descent group affiliation on marriage, and they still owed formal allegiance to their own political leaders. In social and political terms, however, and with respect to their day-to-day experiences, the lives of in-marrying men changed in fundamental ways as a consequence of their marriages. These changes were realized in the kinship terms with which in-marrying men were referred to and addressed. In his natal village, for example, a second-born male would be referred to and addressed by same-generation juniors as bang ngah or simply ngah ("elder brother, second born," or "second born," respectively). If he married a woman who was first-born, however, same-generation juniors in his wife's village would refer to and address him as bang lung or simply lung ("elder brother, first born," or simply "first-born," respectively), thus reinforcing the change in his social identity. More generally, he would be defined as orang semenda in his wife's village, and thus subject to all the constraints entailed in the relationship between orang semenda and tempat semenda . Some of these

constraints were expressed in customary sayings noted earlier, which suggest that the labor power and material resources of in-marrying males were of critical concern to their wives' kin.

These and other data (presented below) indicate that a man's economic competence and social status and prestige within his wife's community were defined largely in relation to how well he provided for his wife and children. A "good provider" built a house for his wife and children on land that was part of (or adjacent to) his wife's natal compound, and he worked with his wife to expand her agricultural (wet-rice) holdings; he also provided his wife and children with cash and commercial items (cloth, jewelry, etc.) acquired through the rearing and sale of livestock and the collection and sale of forest products. Property rights thus created were defined as "conjugal earnings" (carian laki-bini ), but the bulk of these rights would pass to the man's wife and children in the event of the dissolution of his marriage through divorce or his death. (They would devolve upon the children and the wife's matrilineal survivors in the event that she predeceased her husband.) These features of the property and inheritance system highlight the structurally important role that married men played in the creation and initial transmission of property rights that would ultimately pass only among their wives' matrilineally related kin; more generally, they illustrate that in-marrying males played a crucial role in the reproduction of the material base of descent units and the larger systems of kinship, politics, and prestige of which they were a part.

We do not know how affinal relations were experienced by in-marrying men, but if the present is any indication of the past, married men often found that they could not live up to the prestige-driven expectations and demands of their affines, and otherwise found these situations both rather oppressive and out of keeping with Islamic ideals, which recognize no such political asymmetries or parochial distinctions (see below). One solution to a married man's dilemma would be to divorce or simply abandon his wife, along with any children he might have. This was but a temporary solution, for divorced (like widowed) men would not necessarily be welcome in their mothers' or sisters' homes for extended periods. Nor was living alone (in a local prayer house or mosque, or in a home by oneself) a viable alternative; for socialization and the sexual division of labor left men with little direct knowledge or experience concerning the domestic tasks necessary to maintain themselves, and houses were defined as female property. Avoiding marriage altogether was not feasible either,

for marriage, along with fathering (or adopting) children, was a sine qua non for adult male personhood.

Another possible and more long-term solution to the predicaments experienced by in-marrying males was to attain political office (alternatively, to become a healer or a shaman). This would enable a married man to establish a separate base of political support and thus partly offset his dependence on, and subordination to, his affines. It would also provide a separate basis for social identity and self-esteem arguably more in keeping with Islamic ideals emphasizing the seamless brotherhood and equality obtaining among all members of the Muslim community (umat ).

This solution to the dilemmas encountered by in-marrying males indicates that there was a critically important but largely "hidden" prerogative of political office: Compared to untitled males, political leaders were not nearly as dependent on the cooperation and goodwill of their wives' kin, and were relatively autonomous in relation to them. In their roles as in-marrying males, in other words, political leaders were relatively unconstrained by the political and economic entailments of the system of marriage and affinal relations. This was especially true in the case of the Undang , who, as noted earlier, is singled out by Taylor (1929) as "the sole exception" to the rule that "a man definitely passes into his wife's [clan] and becomes subject to her [clan] chief in all matters affecting her and her family." I suspect it was also true, though less pronounced, for clan chiefs, though there is no direct evidence for this other than clan chiefs' exemption from the ritual fetching of the groom and his kin during certain stages of wedding ceremonies. In any event, Undangs' freedom from the constraints of the system enabled them both to exert critical leverage toward social and cultural change in the latter part of the nineteenth century (and throughout the colonial era in general), and to confer legitimacy on myriad departures from tradition (see Peletz 1988b).

One should bear in mind, however, that there were not all that many political (or ritual) offices to go around, and that most men were therefore unable to claim roles as political leaders or ritual specialists, or otherwise define themselves in "positional" terms. Rather, most men were defined simply as kinsmen: husbands, fathers, brothers. In light of the material presented earlier, it seems reasonable to assume that they were defined first and foremost as in-marrying males, and as husbands and fathers in particular.

Nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan is by no means the only society in which the majority of men, and constructions of masculinity generally,

were defined largely in "relational" terms. Such was clearly the case in nineteenth-century Aceh (northern Sumatra), which had systems of kinship, marriage, and prestige that were in many respects quite similar to those in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. Siegel (1969:68) notes, for example, that in nineteenth-century Aceh, "[male] villagers were first of all husbands and fathers." This is to say that men's primary identities and senses of self were defined not by their roles or positions in the political economy, or in terms of citizenship, nationality, or religion, but rather in "relational" terms of the sort that, according to much of the literature on women and gender, are ostensibly reserved for women (see, e.g., de Beau-voir 1949; Ortner 1974; Ortner and Whitehead 1981a; Chodorow 1974, 1989; see also chaps. 6 and 7, below). Of additional interest here is that "even when [Acehnese] men lived up to their material obligations, they had little place in their wives' homes. Women were independent of men, even if they [men] could pay their own way" (Siegel 1969:54). Stated differently, "Although men tried to create a role as husbands and, especially, as fathers, women thought of them as essentially superfluous. They allowed men no part in raising children and tolerated them only so long as they paid their own way and contributed money for goods that a woman could not obtain through her own resources.... A man's role as a husband-father in the nineteenth century was small indeed.... Men were like 'guests in their own homes"' (Siegel 1969:54). Many and perhaps all of these generalizations pertain to nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan as well, and are also relevant to contemporary Negeri Sembilan (Siegel 1969:183), as will be discussed later.

Having drawn attention to the pressures and difficulties that many (perhaps most) men experienced in their roles as husbands and fathers (and in-marrying males generally), I should emphasize that some men undoubtedly did succeed in living up to and gaining prestige from these roles. They did this partly by being "good providers," especially by raising and selling livestock and collecting and selling or trading forest products for commercial items and/or cash that could be used to supplement the rice and other agricultural products their wives contributed to the household coffers.

Another way in which men gained prestige was by making the pilgrimage to Mecca (the haj ). Recall that married men, like the rest of the population, were Muslims and thus bidden to undertake the haj should they be financially able. Making the pilgrimage was not merely a way of carrying out one's religious obligations, however; it also brought the pilgrim considerable prestige both as a person of means and as someone who had

acquired uncommon and otherwise highly valued religious experience and knowledge. Equally important, the haj was apparently widely seen as an "outlet for humiliation" (Gullick 1987:233 n.53, 250; see also Ellen 1983:74) in the sense that its performance enabled individuals to make partial atonement for their social sins and shortcomings.

Not surprisingly, gaining sufficient funds to make the haj was a principal objective of men who engaged in cash-cropping in the early years of colonial rule. Even before that time, the sale of forest produce and livestock had been undertaken for this purpose. Thus, in 1892 Lister wrote that the Yang diPertuan Besar had informed him that

The money supply for luxuries had always been obtained from the sale of fruit, vegetables, and orchard produce generally but in a far greater degree from the sale of buffaloes, goats, and poultry reared on these lands.... It was also by this industry that the people of the country were able to save up money to accomplish the pilgrimage to Mecca.... In former times, prior to the natives having been given facilities in regard to working for wages, this was in most cases the sole source of cash wealth. (quoted in Gullick 1951:48)

We see here the mutual reinforcement of two separate though interrelated criteria for prestige ranking: the one based on the cultural construction of affinal obligations, relatedness, and cleavages keyed ultimately to the system of hereditary ranking and prestige; the other resting on a more transcendent ideology according to which all men are equal before God, but those among them who journey to Mecca enjoy exalted spiritual and social standing. That a man could earn prestige on both accounts through trading activities is, I think, a critical factor in motivating their involvement in trade in the first place, and in encouraging both the colonial-era acquisition of land by males and their involvement in cash-cropping on the whole (see Peletz 1988b).

It would obviously be useful to know something of the effects of the pilgrimage experience on men (and women) from Rembau and other parts of Negeri Sembilan. Unfortunately, there is very little information on such matters, or even on more basic issues such as how many men (or women) from Negeri Sembilan were making the pilgrimage in the mid-or late nineteenth century. Gullick (1958:141) writes that six of thirty "notables and headmen" assembled in Rembau in 1883 had been to Mecca, though he hastens to add that it is highly improbable that a full 20 percent of the entire population had undertaken the pilgrimage. It is quite likely, in any event, that men from Negeri Sembilan who made the pilgrimage

had experiences similar to those of pilgrims from other parts of the Peninsula and the Malay-Indonesian world generally. These experiences may well have led to the development of a deeper appreciation of the broader Muslim community to which they belonged, and the beginnings of a clear sense of some of the similarities and differences between Malayan (especially Negeri Sembilan) Islam and adat on the one hand, and Middle Eastern variants of Islam and "custom" on the other. As such, they might have entailed a greater awareness of the ways in which their roles as husbands and fathers, and as in-marrying males on the whole, contrasted with the roles of married men elsewhere in the Muslim world. Regrettably, however, the precise extent to which this greater awareness may have helped motivate men to effect changes either in their roles as husbands and in-marrying males, or in the more encompassing system in which these roles were embedded, is unclear, at least for the period prior to colonial intervention. Unclear, too, is the extent to which developments of the sort at issue here might have led to the increased salience (in local society and culture) of the concepts of "reason" and "passion."

Contrasting Representations Of Marriage And Affinal Exchange

Much of what I have described thus far has been couched in the terms and concepts of the outside observer. We also need to know how the actors represented their system. For this I turn briefly to marriage and funerary rituals, which indicate that nineteenth-century representations of marriage and affinal exchange were in many respects quite contradictory. Before addressing such matters it will be useful to provide a few comments concerning the negotiation of marriage and ideal marriage partners.

Nineteenth-century marriages were arranged, and senior kin, especially females, appear to have played the principal role in spouse selection. Newbold (1839 I:254), for example, notes that "the [marriage] alliance is first agreed upon by the friends of both parties, generally the matrons " (emphasis added). Precise information on which female relatives played a decisive role in arranging marriages would certainly be of interest, but unfortunately no such information exists. At present, mothers, mothers' sisters, and other matrilineally related female kin typically play the decisive role in arranging marriages, and this situation has probably always obtained (cf. Lewis 1962:166-67; Abdul Kahar bin Bador 1963). Situations such as these, which prevail in other parts of the Malay Peninsula and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, are part of a larger Southeast Asian pattern

of women's predominance in diplomatic matters, trade, and marketing—and in managing information and social relationships generally—which serves both to insulate men from the haggling, negotiation, and compromise that could pose serious threats to their status concerns, and to help ensure that the latter concerns do not interfere with "good business" (see Reid 1988:163–72; see also Brenner 1995, and chap. 7, below).

Female preponderance in arranging marriages in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan is noteworthy in light of the fact that men rather than women were accorded the role of giving, receiving, and otherwise publicly validating affinal transactions in the formal context of engagement and marriage ceremonies. This suggests an implicit gendered division of labor—between "practical" and "official" tasks—of the sort which is found in many other parts of the world (see Bourdieu 1977:33–38), and which is sometimes keyed to a more encompassing (analytic) distinction between "practical" and "official" kinship, about which more in a moment.

As for ideal marriage partners, contemporary accounts suggest that, in the nineteenth century, the ideal groom-to-be was an industrious man with a demonstrated competence in agriculture and trade, as well as Koranic recitation, adat lore, various elocutionary skills, and one or another domain of ritual knowledge. He was also at least a few years older than his bride-to-be, of generally comparable status and untainted pedigree, previously unwed, free of physical disabilities, and neither "insane, leprous, impotent, nor lost to a sense of shame" (Parr and Mackray 1910:80–81). Corresponding qualities were sought in brides (they should be neither "insane, nor afflicted with dropsy or hemorrhoids, and should be capable of consummating the marriage" [Parr and Mackray 1910:80–81]), one principal difference being that a girl's prior marital status and virginity were of greater social concern. A girl's competence in cooking, washing, sewing, and agricultural labor also counted for much more than her mastery of Koranic verse and verbal skills.

There also seems to have been a preference for local (but not necessarily village-level) endogamy, and for marriage within the same relative generation, even though a "good match" might join a man with a woman held to be one generation his junior. In addition, marriage with (nonmatrilineal) relatives (saudara ) was favored over marriage with non-kin or strangers (both glossed orang lain or "other people"), as described by present-day villagers and by the accounts of earlier observers (e.g., Lewis 1962:164–65). More precisely, ideal marriage partners were of comparable status and wealth, and stood related as cross-cousins of the same generation.[9]

Less clear, however, is whether these latter ideals pertained to cross-cousins of the first degree or simply to all individuals related as cross-cousins. It is also difficult to determine the extent to which matrilateral cross-cousins might have been favored, if at all, as potential spouses for eligible bachelors (or their marriageable sisters) (but see de Josselin de Jong 1951:174, 1977:250–51). The data suggest only a general preference for marriage with classificatory cross-cousins on either the maternal or paternal side (Lewis 1962:164; Peletz 1988b:64–70).

Official and Practical Kinship

To help make sense of the contradictory representations of marriage and affinal exchange to which I referred earlier, I draw upon and employ a modified version of Pierre Bourdieu's (1977:33–38) distinction between "official" and "practical" kinship, which I find heuristically valuable, though ultimately somewhat simplistic. Bourdieu develops these terms as part of a larger program designed to help social scientists better appreciate that static, highly abstract formulations and models of formal or "official" rules and principles of social structure (such as those for which Lévi-Strauss is justly famous) do not get us very far in understanding social actors or the myriad contexts in which they organize themselves, relate to one another, avail themselves of resources, or create meaning and order in their lives. Bourdieu argues that if we want to understand these phenomena we need to devote far greater attention to social actors' contextually variable behavioral strategies, especially those everyday practical strategies geared toward the attainment of locally defined value. These strategies are of course informed by "offical" rules and principles, but they are also conditioned by culturally induced but largely implicit (and sometimes unconscious) dispositions as well as material and symbolic interests, and are thus not in any way "mere execution[s] of the model (in the ... sense of norm ... [or] scientific construct)" (Bourdieu 1977:29). Of more immediate relevance is that, for Bourdieu, the term "official kinship" refers to "official representations" of kinship and social structure, which "serve the function of ordering the social world and of legitimating that order" (Bourdieu 1977:34). Official kinship is "explicitly codified in ... quasi-juridical formalism" (Bourdieu 1977:35), and is, at least with respect to kinship as a whole, "hegemonic" in Raymond Williams's (1977) sense of the term. "Practical kinship," on the other hand, denotes the uses and representations of kinship in everyday practical situations, which are more oriented toward "getting things done" than to formal representa-

tions of kinship and social structure (though I would emphasize that they, too, have important legitimating functions).[10] In many societies the distinction between official and practical kinship is highlighted in the institution of marriage. As Bourdieu (1977:34–35) notes, "marriage provides a good opportunity for observing what ... separates official kinship, single and immutable, defined ... by the norms of genealogical protocol, from practical kinship, whose boundaries and definitions are as many and as varied as its users and the occasions on which it is used." To paraphrase: It is practical kin—"utility men," in Bourdieu's terms—who do much of the actual work in arranging marriages; it is official kin—"leading actors," in Bourdieu's terms—who publicly celebrate and validate them.

Bourdieu's distinction between official and practical kinship is useful for my purposes, but it is insufficiently precise both for Negeri Sembilan and for many (perhaps most) other societies. This is partly because official kinship is rarely if ever "single," with all that is implied in terms of being monolithic, internally undifferentiated, and free of contradiction. It is, moreover, essential to appreciate that in some cases—such as those of the Merina and the Andaman Islanders (see Bloch 1987; Ortner 1989–90, respectively)—there are three or more contrasting sets of representations bearing on the culturally interlocked domain of gender (to which domain the distinction may be applied), not simply the two that are suggested by Bourdieu's terminological and analytic distinction. To this we need add three other important qualifications. First, contrasting representations bearing on kinship, gender, and so on, may be invoked—and contested—in all kinds of different contexts (practical and official alike). Second, the majority of (if not all) such representations may be thoroughly grounded in practice, though differently so (e.g., in different contexts and domains, to different degrees, in different ways, with different effects). And third, all may speak to "partial truths," the more general point being that cultures-or, to be more precise, elements of ideological formations—" get things right" (are truly illuminating) in some contexts, but are "wrong" or "false" (profoundly distorting or mystifying) in others.

Caveats such as these should be borne in mind throughout the ensuing discussion. So, too, should the more basic and in some ways far more important point that distinctions of the sort proposed by Bourdieu, which have deep roots in Marxist contributions to theories of ideology, are not intended to effect "an ontological carving of the world down the middle" (Eagleton 1991:83), but rather to highlight the existence and entailments of the different perspectives, discourses, and registers that invariably constitute any given ideological formation. There are, of course, other con-

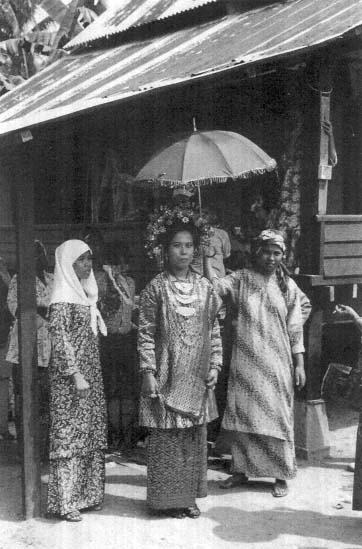

Figure 9.

Clan chief at wedding

ceptual and analytic frameworks available for handling the polyvocality and multiplicity at issue, but they, too, have their limitations and need not concern us here.[11]

The modified distinction between official and practical kinship that is proposed here is particularly relevant to an understanding of marriage and funerary rituals in nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan. These rituals are of interest not only because they shed valuable light on how people represented their systems of kinship and gender. They also illuminate highly significant ("on-the-ground") dynamics of the nineteenth-century systems, the historical reproduction and transformation of which are crucial for an understanding of kinship and gender at present.[12]

In nineteenth-century Negeri Sembilan, official representations of kinship, gender, and affinal exchange were especially evident in the first day of formal wedding ceremonies. This day served as the occasion for lavish feasting as well as the ritual presentation of "marriage gold" (mas kawin ) from the clan chief of the groom to the clan chief of the bride (Parr and Mackray 1910:36, 94). This ritual not only validated the bond between husband and wife and the linkage between their respective descent units. It also highlighted clan chiefs, and men more generally, as "leading actors," effectively denying the role, in arranging and maintaining marriage and affinal relations, of untitled males and women as a whole.

The same day served as the occasion for the specifically Islamic dimension of the wedding, which also symbolized the official view of kinship and gender. This ritual called for the presence of a local mosque official, the bride's Islamic guardian (or wali ),[13] the groom, and a few male onlookers as witnesses. It focused on the mosque official's recitation of the "marriage service" (khutbah nikah ) and symbolized, but did not actually effect, a transfer of legal responsibility and control over the bride from her Islamic guardian–usually her father but conceivably her father's brother or another of her father's close male relatives–to her husband. This ritual represented the system of affinal alliance as composed of descent units linked to one another through exchanges of rights over women. As such, it entailed a mis representation of the practice of affinal exchange and social reproduction more generally; for the practice of marriage and affinal exchange did not really center on a father relinquishing rights and obligations with respect to his daughter and doing so in favor of his daughter's husband; rather, it focused on a mother's transfer of claims and responsibilities over her son to the son's wife and the latter's immediate kin.

I will return to this theme (the exchange of men) in due course. Before doing so I might explain the basis of my contention that the mosque official's ritualized recitation of the "marriage service" symbolized but did not effect a transfer of legal responsibility and control over the bride from her Islamic guardian to her husband . The bride's Islamic guardian was not vested with the control over the bride that was encoded in this feature of the marriage ritual; rather such control was vested in the bride's matrilineal kin. The groom, moreover, did not really acquire full legal responsibility and control over the bride, though he did acquire certain rights in his wife's sexual services, labor services, and property (see below); such control remained with the bride's kin.

Why then did this ritual exist? Put differently, what purposes, if any, did it serve? One could conceivably argue that this ritual was simply integrated into local marriage practices when elements of Islam began to be incorporated into various domains of Malay society and culture subsequent to "the coming of Islam" beginning around the thirteenth century. Such an argument begs the question, however, just as it glosses over the possibility that a structurally similar ritual might have existed in the Malay world before "the coming of Islam." It also says nothing about the purposes such a ritual may have served. We can only speculate on this issue, but it is reasonable to suggest the following: By (mis)representing the system of marriage and affinal relations as composed of groups of men

exchanging rights over women, this ritual statement helped disguise and render more palatable to men, especially the untitled majority, the basic social fact that it was the exchange of rights over men, untitled men in particular, which made possible the production and reproduction of the material and social basis of households and lineages, and the larger systems of kinship, politics, and prestige of which they were a part. In this view, the ritual statement at issue was structurally motivated by the prestige considerations of titled males such as the Undang (and perhaps clan leaders as well), who clearly had much to gain by the reproduction of the system and were at the same time largely immune to its imperatives and constraints, at least in their roles as husbands and in-marrying males. Prestige considerations of the Undang aside, the ritual also resonated deeply both with Undangs' experiences as husbands and in-marrying males, and with the prestige differentials which obtained between men and women generally (titled and untitled alike), and which were sanctified and rendered theoretically inviolable by their grounding in a heavily (but by no means thoroughly) Islamicized cosmology.

Most other elements of marriage ritual served to foreground practical representations of marriage and affinal exchange, which were clearly contradictory to their official counterparts insofar as they emphasized not only that men–as opposed to women–were being exchanged, but also that they were being exchanged by groups of women, not by other men. Thus, the second day of wedding festivities witnessed the groom's relatives traveling to the bride's home bearing gifts of food, along with a lavish feast sponsored by the bride's mother. Subsequent to the feast, the groom formally entered the bride's mother's home, bringing gifts of food along with a bundle of clothes and other personal possessions, which symbolized the severance of residential ties with his mother, sisters, and other close kin. Once inside, he was welcomed by his in-laws and formally accepted into their household. Other ritualized introductions typically stretched over the course of the following week or two. One such series of introductions involved visits by the bridal couple to various households inhabited by the groom's kin. Not surprisingly, these were glossed mengulang jejak , which refers to the groom's "going over," or "retracing," his footsteps for the very last time.

Many of these same practical representations of marriage and affinal exchange were highlighted in funerary rituals. In the event of the husband's death, for example, the widow financed the burial as well as the principal funerary rituals and feasts (Parr and Mackray 1910:88, 91; Taylor [1929] 1970:123), all of which occurred in her village. Particularly

noteworthy is the ritualized exchange which ideally took place during the final feast in the funerary cycle, and which consisted of a pair of pants, a coat, a sleeping mat, and a pillow (Parr and Mackray 1910:88; DeMoubray 1931:149–50); in short, the very same items the husband brought with him when he began living among his wife's relatives and simultaneously severed residential ties with his own kin. It is especially significant that these items passed from the widow to her mother-in-law. The design of the transfer symbolized both the end of the daughter-in-law's relationship with her former husband, and a return to the mother-in-law of the son that she had in effect "given away" in marriage. Moreover, just as this ritual depicted the principal exchanges in the formation of conjugal and affinal bonds as centering on transfers of rights over males, so, too, did it portray such exchanges as entailing transfers between women, who were thus represented as trafficking in men, or in rights over them.

The rituals following the dissolution of the conjugal bond owing to the wife's death conveyed generally similar messages. Suffice it to say that they highlighted the peripheral and "guest" status of the widower among his affines, underscoring that he could only remain among them if his children indicated a desire to have him stay.

Practical representations of marriage and affinal exchange were largely congruent with everyday practice in the nineteenth century. These circumstances help account for the references in the early colonial-era literature to men "becoming members of" their wives' clans upon marriage. They also help clarify the meaning of the customary sayings or aphorisms that I discussed earlier.

The Exchange of Men