Since 1970:

Conflicts Surrounding Hotel Life

Before 1970, the elimination of SRO units was encouraged by government policy, often against the objections of private hotel owners. Since 1970, hotel housing advocates have hammered together a pro-SRO movement and won converts in official life. Pro-SRO activists continue to be haunted by critics and by the underside of hotel life. Nevertheless, since 1970, officials and owners have changed sides. Growing numbers of public officials have moved to conserve hotels, while more owners want to close or raze their buildings. The following summaries can introduce only salient moments and principal themes in the gradual building of a national pro-SRO movement after 1970. Not presented here—but available in the cited literature—are the complex historical processes which supported and delayed each case: urban and regional economies, local power structures, and myriad participants. For each failed SRO campaign noted here, a great many more occurred. Other positive examples also exist, but in more modest numbers.

The Coalescing of a Pro-SRO Movement

Between 1967 and 1973, the political situation of hotel life changed dramatically. The climate of American political activism and awareness of minority needs had reached critical mass. As part of reforms aimed at urban renewal, arguments began to be heard locally and in Congress for the inclusion of hotel residents in public housing programs.[38] Responding to these arguments, Congress passed the Uniform Relocation Act in 1970. This policy change marked 1970 as a major pivot year in the political history of SROs. For the first time, redevelopment agencies and other federally funded groups were legally required to recognize people living in hotels as bona fide city residents; if a residential hotel was to be demol-

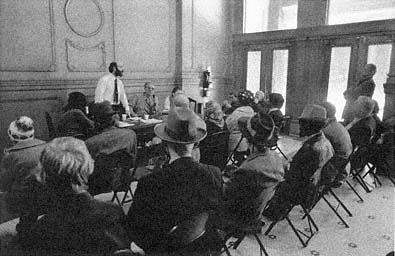

Figure 9.13

A hotel tenants' meeting in San Francisco's South of Market, 1973. Members

of Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) confer with

their lawyers in a hotel lobby.

ished as part of a public project, the agency had to help the hotel tenants find new housing, just as if they were apartment dwellers. Twenty years of official removal had made SRO units hard to find, and the process of assisting tenants was difficult. Most critically, the budget outlays were substantial: each hotel dweller was to receive the $200 household dislocation allowance, compensation for moving costs, and up to $83 a month for four years if the new housing cost more than 25 percent of the individual's income; the total was not to exceed $4,000.[39] Suddenly hotel residents were both visible and very expensive for the urban renewal process.

Simultaneously, SRO tenants had learned their rights and with community activists had organized themselves more effectively. Because urban renewal was early and done on a large scale in San Francisco, the local movement against it was an important national example. In 1968, South of Market hotel tenants began organized protests of the relocation for what became Moscone Convention Center and Yerba Buena Gardens (fig. 9.13). In December 1969, courts issued the first restraining order against the San Francisco Renewal Agency, and the court battles continued for four years. The residents proved to the court that adequate replacement housing did not exist in the city, and the court forced the SFRA to develop over 1,500 units of new housing in the area. Developed by a nonprofit community group, Tenants and Owners Development Corporation (TODCO), the first new replacement housing opened in 1979.[40]

San Francisco was only one early center among several engaged in full-fledged fights to revise plans for urban renewal and to save SROs. In Boston SRO tenants stopped progress on a renewal program. So did tenants in New York's Greenwich Village and on the Upper West Side. The New York Mayor's Office of SRO Housing was opened in 1973 to work on social programs and tenant protection laws. Other groups were working to rehabilitate hotels and improve their management. In 1975, a pro-SRO group in New York City, Project FIND, leased and moved into the 308-room Woodstock Hotel, located near Times Square.[41] These projects saved only a few hotels from demolition but did create a new and embarrassing climate of public relations. Suddenly hotel owners, city housing authorities, redevelopment agencies, and other people with anti-SRO views had to work hard to prove that residential hotels were an urban blight of culturally aberrant buildings where only marginal people lived.

Unfortunately, the Uniform Relocation Act could not decree an instant change in the SRO attitudes of all housing officials in Washington, D.C., or in local agencies; at first, the act exacerbated harassment of residents and hastened hotel demolition. From 1970 to 1980, an estimated one million residential hotel rooms were converted or destroyed, including most of the Yerba Buena area (fig. 9.14).[42] Hotel owners generally did not want help to stay in business, in large part because of the potential profits from the expansion of downtown offices. In the 1970s, downtown office construction suddenly started a new boom and developers began to offer hotel owners handsome prices for their properties. Then, as now, the land underneath most residential hotels had more market value than the buildings. In New York, an empty hotel was worth two to three times that of an occupied building because the new speculator owner could more quickly rehabilitate it for a new use or tear it down.[43] Then, as now, to encourage the perception of hotels as blight, public and private owners understated the positive side of hotel living and overemphasized the problems in bad hotels. In day-to-day management and long-term goals, the lines between public and private ownership often blurred. Redevelopment agencies (through eminent domain) and city governments (through tax foreclosure) frequently became unwilling landlords for remaining residential hotels. To manage their hotel programs, they often hired anti-SRO people from the property industry, not pro-SRO people from social welfare offices.

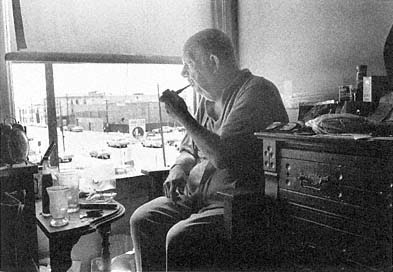

Figure 9.14

Ken Roth, a South of Market hotel resident in the 1970s, watching the

demolition of his San Francisco neighborhood for the Yerba Buena project.

For the stubbornly positive SRO buildings with sound structures and tenants neither marginal nor easy to dislodge, both public and private landlords developed an arsenal of tools to create problems where none have existed before. Although the techniques were perfected in the early 1970s, many remain in use. To generate vacancies, one of the most effective means was to reverse normal management principles and to harass the tenants: replacing friendly, long-term staff with churlish employees; suddenly lowering the standards for admissible tenants; and loosening security, stopping maid service, or permanently removing clean linen from stock. Other owners deliberately aggravated tenants by shutting off heat and hot water for long periods, locking toilet rooms, not repairing (or entirely closing down) elevators in six-story and eight-story buildings, plugging room locks, seeing that mail and messages were "lost" (particularly for tenants who were demanding their rights), not letting Meals on Wheels attendants deliver food, spraying for roaches while tenants were still in the room, taking the furniture out of the lobby, falsely advertising no vacancy so the hotel emptied, and sending gangs of thugs along with eviction notices to intimidate tenants. The agents of one hapless San Francisco hotel owner had the poor judgment to use the roach-spray-in-an-occupied-room technique while one of Mayor Dianne Feinstein's aides was visiting the tenant. One New York landlord went at the steel stair landings of his building with a hammer and chisel; after five flights of stairs had thus

"collapsed," the building had to be vacated because of failure to comply with fire safety laws.[44]

In San Francisco, struggles like these eventually led to the International Hotel dispute and eviction of 1977, which was another turning point in national opinion about SRO homes and SRO people. After eight years of nationally publicized eviction struggles, at 3:00 A.M., 330 police officers and sheriff's deputies converged on the hotel, which stood at the edge of Chinatown. After vociferously protesting the court orders to do so, the sheriff had finally come to evict about forty elderly Chinese and Filipino residents who remained in the 184-room hotel. On nearby sidewalks more than 2,000 demonstrators protested. Many of the public knew the hotel's location not only because of its residents but also because of its large basement nightclub, the hungry i, which in earlier years had headlined Barbra Streisand, the Kingston Trio, Dick Cavett, Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory, and Woody Allen.[45] After the eviction battle, the owner of the property, the Four Winds Corporation of Singapore, immediately razed the building. Fifteen years later, the site was still empty, except for the archways of the remaining basement walls, where the hungry i had once been. There, on cold nights, homeless people huddled to get out of the wind.

The tenants in the International Hotel lost their single-room homes, but like tenants in earlier cases, their fight helped to raise new questions about the intersections of hotel life, property rights, and social services. For instance, the year following the eviction, the staff of the U.S. Senate used the case for the introductory example in an information paper about the SRO crisis.[46] Owing to the fights of the 1970s, the formerly invisible realms of hotel life finally began to appear regularly in public spotlights, with front-page newspaper articles headlined "Rooms of Death," "Heatless Hotels," and "Struggle over Downtown Continues." Through the 1980s, the New York Times prominently featured SRO stories nearly once a week. The Gray Panthers and other senior groups also came to be instrumental in several fights.[47]

Another important example of the turnaround process since the 1970s is the experience of Portland, Oregon. About the same time as the last fights at the International Hotel, a private group remodeled Portland's Estate Hotel with a city loan; in 1978, neighborhood leaders formed the nonprofit Burnside Consortium (now called Central City Concern) to coordinate services and to preserve other housing. In 1979,

Andy Raubeson was appointed director of the consortium and saw immediately that SRO hotels were a prime priority for his skid row clientele. "It just seemed too obvious," he says, "that we had to champion the housing stock." His organization began leasing and then buying hotels, eventually renovating more than five hundred units.[48] The Burnside experience emphasizes the growing realization that proper management—often subsidized by a nonprofit organization—is a key to maintaining low-cost hotel life. As part of the Portland action, in 1980, U.S. Rep. Les AuCoin, a Democrat from Oregon, persuaded Congress to make SROs eligible for federal low-interest rehabilitation loans and then for Section 8 housing funds. These and other successful programs have put Portland in the forefront of municipal efforts to preserve SROs.[49]

With the federal Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981 and the Stewart B. McKinney Bill in 1987, hotel housing moved further toward better housing status and became eligible for a few other subsidies. With cruel irony, these official changes of heart began just before the Reagan and Bush administrations slashed public housing funds by 80 percent.[50] The widespread implementation of the new policies was thus deferred.

The Legacy of Problem Hotels

In spite of a generation of pro-SRO work and the gradual but growing official acceptance of hotel life, the problems of the past continue to haunt the progress of the present. At the worst hotels, not only the buildings are residues. So are the owners and managers. For many owners, a net loss helps their tax accounting. Such owners are unwilling to put money into their buildings; they hire the cheapest possible managers, who rarely have any training and never stay very long in the demanding and often dangerous business. Many managers lack the simple bookkeeping acumen to maintain profitable cash flows. Observers in Portland saw hotels where repair investments as small as $15 per room (for fixing a broken sink, window, or toilet) could have restored one-fifth of the vacant rooms to full weekly and monthly rents. For other managers, costs of labor and of maintaining desk, telephone, linen, and housekeeping services have risen at a rate greater than reasonable rents.[51]

The most deteriorated rooms and disturbing social conditions in hotel life do not necessarily occur in the cheapest hotels but in those

where managers and owners are completely callous, inept, underpaid, or overwhelmed. Most simply, these locations can be called "problem hotels." A subset of problem hotels are those where the owners and managers have given up any attempt at lobby surveillance and where no one screens or controls troublesome residents, guests, or behavior. Social workers call such places "street hotels" or "open hotels."[52] The daily conditions around problem and street hotels disturb even SRO advocates. In a street hotel, the negative stereotypes of hotel tenants ring true: a majority are unemployed, addicted to alcohol or narcotics, mentally ill, or otherwise chronically disabled. The tenants exhibit little capacity for normal social life or collective political action. Single parents may leave children unattended for long periods. The residents might include someone who likes to throw knives at walls or a heavy drinker who routinely vomits on the hall carpets or urinates in the elevators. In street hotels, lobbies and halls are unsafe because speed freaks attract or bring "bad trade" into the building. The desk clerks do nothing to screen out these people. Other tenants collect stolen weapons or other contraband items in their rooms. The more vulnerable tenants are often brutally beaten and robbed by the tougher ones. Tenants in problem hotels expect to see psychotic behavior or erratic anger.

Safety and health hazards also darken life in problem hotels. Children fall to their deaths from unprotected windows or open elevator shafts. Uncollected garbage piles up in the halls; rats jump from can to can. Some residents hoard toilet paper; then because no toilet paper is available, other residents substitute newspaper, which clogs the toilets. Because the maintenance staff is minimal at best, the toilets can remain out of commission for a long time. Eventually, when angry tenants break toilets with baseball bats and angry landlords refuse to replace the shattered plumbing, even those not incapacitated by alcohol use the halls for toilet rooms.

The fire hazards of problem hotels match their social and health risks. Fire escapes may be wooden; panic hardware is absent on the doors; no alarm system has ever been installed, or the aging system is out of order. Smoking in bed causes frequent mattress fires. Tenants (or landlords) intentionally set other fires. Because the electrical wiring in the rooms is old and intended to run only one 60-watt bulb, overloaded extension cords to refrigerators and hot plates routinely blow fuses or

start fires. Managers and tenants put out the fires by themselves if they can; if they call the fire department, fire marshals may inspect and then close the building.

The people and activities from these problem SRO buildings spill out into the surrounding neighborhoods. Socially marginal residents and their friends congregate outside the door. They panhandle passing pedestrians, or rant to them about imaginary fears. Garbage (called "air-mail" by hotel residents), epithets, and urine can be hurled from open windows onto surrounding sidewalks.[53] New York's Hotel Martinique, made infamous by Jonathan Kozal's study Rachel and Her Children , exemplified many problem hotel dimensions of the mid–1980s. Kozol detailed a case in which crowding, lack of services, and corruption had created a nightmare for family groups. The supply of the city's public housing apartment units and affordable apartments had lagged so far behind need that social workers were forced to dump clients on a temporary basis that was essentially permanent and very expensive for the public. Dangers and privations endured by single people and by the elderly in problem hotels can be equally serious, and are often similarly intertwined with public assistance.

Problem motels for permanent residents have begun to reflect the degree to which the American city has become a suburban city. Where highway traffic has shifted away from a motel and the units are over a generation old, managers have hung out signs advertising WEEKLY AND MONTHLY RATES. At the more expensive examples are salesmen on temporary assignment and construction workers in town for a season. There, the system works. Elsewhere, residential motels often shelter very low income residents. Families unable to afford other housing and recent immigrants sometimes fill whole motels that have the worst management. Many of the families, like those in light housekeeping rooms in the 1920s, have their furniture in storage. In 1985, officials estimated that Orange County, California, had 15,000 people living in motels, along boulevards such as Katella Avenue near Disneyland. South of San Francisco, hundreds of families and single-person households live in residential motels that line access roads to the Bayshore Freeway not far from the airport. The Memphis, Tennessee, motel where the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in 1969 had become a residential motel and a haunt of prostitutes by 1988, when residents were evicted to convert the structure into a museum of the

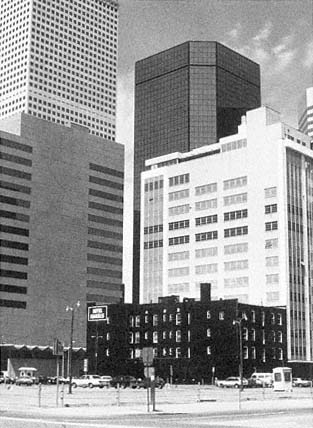

Figure 9.15

A three-story rooming house, the Hotel Harris, virtually

quivering before the onslaught of new office tower

development in Denver, 1983.

civil rights movement. Even the wealthiest counties can have serious residential motel problems. The citizens of Westchester County, north of New York City, refuse to build adequate low-income housing but pay $3,000 per month for each of hundreds of residents in miserable motels where the maids steal medications and a reputed 80 percent of the residents use crack cocaine. Often without cars, parents cannot reach jobs or take their children to school.[54]

Many of the eradication processes that destroyed good hotel homes in the 1960s and 1970s have remained in force (fig. 9.15). Through the 1980s, professional "housers" or housing activists were typically not converted to pro-SRO views. Cushing Dolbeare, long-term director of the National Low Income Housing Coalition in Washington, D.C., admits that people like herself were the hardest to convince. She notes that housers "assumed that the requirement for a kitchen and a bath for each unit was always supposed to be in a housing proposal." She was

not personally involved in the pro-SRO movement until 1981.[55] Some housing advocates still expect that preserving hotel housing will undermine family housing minimums and that the cities will not have the ability to enforce occupancy standards of one or two people per room even for elderly people. All hotel rooms, the doubters say, will soon be overcrowded with single mothers with three children each. In 1985, when many people could only choose between living on the street or in an armory shelter, a HUD program director still stated that in rehabbed structures "asking people to give up a private bathroom is an awful lot."[56]

Official actions continue to reverse earlier progress. In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court eviscerated New York City's 1985 moratorium on SRO conversion or demolition, although rent stabilization laws continued to protect most of the city's long-term tenants. In California, for more than twelve months after the Santa Cruz and San Francisco Loma Prieta earthquake in October 1989, planners and hotel residents of several cities had long struggles with officials of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) over whether or not residential hotels qualified as dwellings for more than $50 million in repair or replacement funds.[57] The debate sounded a great deal like the debates of the 1960s. "The wave of the future may be an undertow," warns SRO activist Richard Livingston. "For each hundred hotel units that we fight to save, a thousand are torn down or converted. We are moving rapidly backwards."[58]

The problems of living at the lowest-priced hotels are serious, but many of them are inherited from generations of misunderstanding. Prohibition, the national ban on alcoholic beverages lasted only thirteen years. The national prohibition of single-room housing lasted more than sixty years and is not yet completely rescinded. Many public officials have come to realize the importance of SROs at precisely the same time that their redevelopment agency has just torn down the city's last publicly owned—and usually largest—SRO buildings.

Nonetheless, shifting policies and programs in several cities show a viability for hotel life and suggest that public vision is widening. Hotels remain the cheapest private housing available downtown. Hotels are less ideal than apartments, especially for families with young children. However, as numerous activists put it, for the most difficult to house

people in the city, hotels work "better than shelters and better than the streets."[59] In bad hotels, a change of owners and better management can create a very different home environment, even for hotel and motel tenants with very low housing budgets. Where managers strictly control lobby entrances, carefully screen residents, and keep up building maintenance, the type of tenants and their living situations change dramatically. Managers at positive SROs still serve their tenants not only as tough-minded rent collectors and rule enforcers but also as social workers, part-time grandparents, or political advocates. Significantly, rents in successful SROs are not necessarily higher than in street hotels, although as the price rises, conditions generally improve. The profitability of a good residential hotel lies in higher occupancy rates with less turnover.[60]

For public housing provision, hotels make economic sense, too. As Bradford Paul has put it, for the cost of one new HUD Section 8 studio apartment, 4 or 5 hotel rooms can be rehabilitated in San Francisco (with its stringent seismic safety requirements); 12 to 15 rooms can be rehabilitated in Portland; or 35 to 40 rooms can be rehabilitated in city-owned hotels in New York.[61] Seeing figures like these, more and more elected officials and representatives have begun to join pro-SRO forces, spurred by the worsening homeless situation. More cities have passed and enforced ordinances to slow the conversion or demolition of residential hotels. Several mayors have created special offices for hotel housing and encouragements for rehabilitation. In the early 1980s, the New York mayor's office began offering six-month training courses (two nights a week) and internships for SRO managers.[62] These experiments in a new attitude about downtown hotel life, in addition to each one hundred hotel units that are saved, may have an importance far greater than their initial numbers. The wave of the future may be a wave of change.