11—

Change and Development among Tribes of Arunachal Pradesh

Realistic accounts of the fortunes and prospects of the majority of the tribal societies in Peninsular India may well create the impression that material impoverishment and the disruption of the traditional social fabric are unavoidable concomitants of the aboriginals' contact with economically and politically more advanced sections of the Indian population. Yet developments in other tribal areas of India present a very different and far less gloomy picture, and in this chapter I shall outline the emergence of Himalayan tribes from almost total isolation and their harmonious integration into the economic and political structure of the wider Indian society. The people in question are of Mongoloid race, speak Tibeto-Burman languages, and dwell in the highlands of the Subansiri District of Arunachal Pradesh. Until recently designated as North East Frontier Agency, this union territory, which extends from Assam to Tibet, always enjoyed a political status different from that of most other parts of India. In the days of British rule only a fraction of the territory was under regular administration, whereas the greater part was a political no man's land where feuding tribes lived in a state of complete autonomy.

When in 1944 I first entered the Subansiri region, so called after its main river, in the course of a mission aimed at exploring the tribal country beyond the control of the Government of India,[1] I encoun-

[1] The circumstances of that mission undertaken in the service of the Government of India are described in my book Himalayan Barbary , and my recommendations for the eventual administration and development of the area are contained in my report Ethnographic Notes on the Tribes of the Subansiri Region .

tered a tribe known as Apa Tani, which numbered then about 15,000 and had persisted for centuries in an archaic economy and self-contained social order uninfluenced by any outside power. Although the Apa Tanis had developed an exceedingly efficient system of rice cultivation which enabled them to produce a surplus of grain for barter with neighbouring tribes, they did not know the use of the plough, were unfamiliar with the wheel, and did not use their cattle for traction, carriage, or milking. Money had no place in their economy, and though a few men occasionally ventured to the fringe of the plains of Assam, not a single Apa Tani had a command of Assamese sufficient for effective communication. A few of the neighbouring Nishis had some knowledge of the Apa Tani dialect, and many Apa Tanis could follow the dialects of nearby Nishi villages, all these tongues being closely related Tibeto-Burman languages. In view of the Apa Tanis' geographical and cultural isolation, one might well have assumed that the obstacles in the path of their development and adjustment to the economic and social system of contemporary India would have been much greater than those impeding the progress of such tribal populations as the Gonds of the Deccan, who for generations have been in touch with advanced civilizations. Surprisingly, the economic and political progress of the Apa Tanis during the past thirty years belies any such supposition, and we are faced with the phenomenon of a rapid material, social, and educational development of a tribal society which has found a place in the modern world without so far losing its identity as a distinct ethnic entity.

In my recent book A Himalayan Tribe: From Cattle to Cash , I described in detail the transformation of the Apa Tanis during the years which followed the establishment of permanent links with the Indian administration in 1944 and 1945, and in this context I shall concentrate on the circumstances which account for the differences between the fortunes of the Apa Tanis and the fate of the tribal societies discussed in the foregoing chapters of this volume.

When the Government of India extended its administration over the region now known as Arunachal Pradesh, it continued the long-established policy of protecting the tribal populations inhabiting the hills which surround the plains of Assam against incursions and exploitative practices of people from the lowlands. Fundamental to this policy was the maintenance of the so-called "Inner Line," a boundary running along the foothills, which no plainsman was allowed to cross without a written permit. Inhabitants of the hills were free to cross this line in either direction, for there was no intention of keeping the hillmen within their territory, only of keeping the lowlanders out. In the days of British rule there was in nationalist quarters considerable criticism of the fact that Indian citizens should need special permission to enter any part of India, but it is to the credit of the leaders of post-independence India that they were realistic enough to retain the Inner Line policy in order to allow the tribesmen of Arunachal Pradesh to develop undisturbed by outsiders competing for the resources of the hill regions. The protection afforded to Apa Tanis and other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh by the Inner Line prevails to this day, and we shall see presently how great were the benefits which they derived from the breathing space provided by this policy.

The basis of traditional Apa Tani economy was agriculture, with animal husbandry and barter trade taking second and third place. The Apa Tanis are expert in growing several varieties of rice on terrace-fields irrigated by a complicated system of channels and ducts fed by streams and rivulets which flow from the surrounding wooded hills into the wide bowl of the Apa Tani Valley. At an altitude of close to 5,000 feet there is no possibility of growing two rice crops per year, but the Apa Tanis make the best of their irrigable land by planting both early- and late-ripening varieties of rice. Unlike many of their neighbours they do not grow rain-fed rice on hill slopes, but use arable dry land for the cultivation of millet, maize, potatoes, and various vegetables, many of which have recently been introduced by the administration. Apart from these they plant fruit trees, and carefully tend groves of bamboos and pine trees required as building material. The meticulous care with which the Apa Tanis have transformed the entire valley into a veritable garden, in which every square yard is put to a useful purpose, is one of the most striking characteristics of the

The Apa Tani Valley is filled with an intricate pattern of irrigated rice fields,

while the villages lie on higher ground at the foot of the surrounding hills.

Apa Tani women, wearing home-woven jackets and skirts, weeding a rice field.

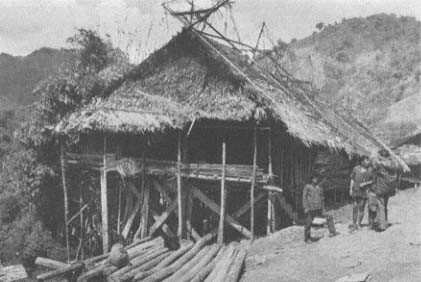

Street in a traditional Apa Tani village; the houses are built on piles and

have verandahs in front and rear.

tribe, and one which distinguishes them from the much less systematic shifting cultivators in the surrounding hill regions.

Contact with the outside world and the growing familiarity of many young Apa Tanis with other regions of India have not led to any fundamental change in agricultural methods, and though Apa Tanis possess cows and bullocks, attempts to introduce ploughing have not met with any positive response. On the other hand Apa Tanis have eagerly taken to fish farming in the flooded rice fields, which provides the owners of fish ponds and suitable fields with a considerable cash income. Similarly, fruit farming, initially subsidized by government, has been developed most successfully. Some enterprising men have planted several thousand fruit trees and derive large profits from their orchard.

In traditional Apa Tani society a man's land-holding determined to a great extent his prestige and influence, and though new sources of wealth have developed, land is still a cherished possession, and rich men continue to invest in land though the yield in money terms is less than the rate of interest paid by the State Bank of India on deposit accounts. Previously land could be purchased only in exchange for cattle, but today Indian currency is widely accepted and most land sales are effected by cash transactions. In 1978 half an acre of irrigated

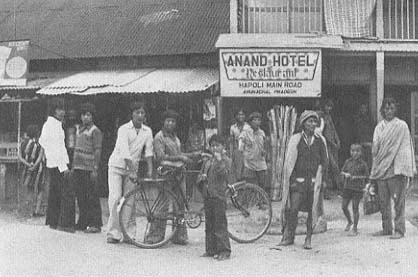

Street in Hapoli, the newly founded district headquarters in the Apa Tani Valley;

shops and restaurants are frequented by Apa Tanis and Nishis.

land was worth about Rs 7,000–8,000, and for a large field near a village up to Rs 30,000–40,000 was paid. In assessing the significance of such cash transactions, it must be remembered that land can be passed only from one Apa Tani to another, for no outsider is permitted to acquire land.

When I first studied the Apa Tanis, none of them ever gave land on lease or hire, and sharecropping was unknown. Today, both leasing and sharecropping have taken root, and men engaged in trade outside the Apa Tani Valley let out their land on rent paid either in cash or as an agreed share of the crop. A novel feature of the agricultural economy is the employment of labourers paid cash wages. Previously most of the work on the fields was done by labour gangs, whose members worked on each others' fields in rotation. Rich men could hire such a gang by paying the workers in rice, but nowadays the payment is usually made in cash. The average daily wage in 1980 was Rs 5 for men and Rs 3 for women, and in either case a midday meal and ample quantities of rice beer were provided by the employer. For the heavy work of levelling fields, Rs 8 was paid, and during rush times adults earned daily wages of as much as Rs 10 to Rs 15. Wealthy landowners spent an annual average of Rs 3,000—4,000 on payments to agricultural labourers.

Apa Tani men and women on the verandah of a house; the men wear rass

pins in their hair-knots.

Large sums of money are also paid for cattle, and particularly for mithan (Bos frontalis ), the bovine which traditionally has the greatest prestige value, both as a sacrificial animal and as a medium of exchange. While in the latter role mithan have been replaced by cash, they still play an important role in ritual and as a source of meat. A full-grown mithan fetches nowadays a price of up to Rs 1,500. Ordinary Indian cattle (Bos indicus ) are also increasingly kept by Apa Tanis. Many animals are bought in the plains of Assam and driven up to the Apa Tani Valley. Some are used for breeding, but all are ultimately destined for slaughter. Among the Apa Tanis there is an inexhaustible demand for beef, and many cows and bullocks are sold at a large profit to neighbouring Nishi or Miri tribesmen, who value beef no less than the Apa Tanis. There is also a flourishing trade in small pigs, purchased in the plains and brought by bus or truck to the Apa Tani Valley, where they are kept till full grown. Meat is an important item of the local diet, and there are not many parts of India where villagers eat meat as regularly as Apa Tanis do. In the old days Apa Tanis used to obtain livestock from Nishis in exchange for their surplus grain, and at the time of seasonal festivals hundreds of pigs were sacrificed, most of which had been supplied by Nishis.

There is still a limited trade between Apa Tanis and their tribal

Apa Tani women and children. The women wear nose-plugs of blackened

wood, blue beads, and hand-woven cloths.

neighbours, but its economic importance has been eclipsed by the Apa Tanis' involvement in commercial exchanges with the people of the plains. They also earn cash by provisioning government employees posted in the hills and by working as contractors or in various other capacities for government agencies.

The headquarters of the Subansiri District, officially referred to as Ziro, is situated in the Apa Tani Valley on a site known as Hapoli. Since this place has been linked by an all-weather road with North Lakhimpur in the plains of Assam, Hapoli has grown into a township with a large bazaar offering a choice of goods hardly inferior to that found in any average Indian district headquarters. But whereas commercial centres in tribal areas of Peninsular India are invariably concentrations of non-tribal merchants, all the shops at Hapoli are owned by Apa Tanis, and no outsider is permitted to establish himself in any locality within the valley. The initial success of the many shops at Hapoli was largely due to the fact that hundreds of Apa Tanis were earning cash wages by being employed in road-building projects and other public enterprises. In the past twenty years there has been a great deal of construction work both inside the Apa Tani Valley and in the surrounding country, and Apa Tanis, who are disciplined and industrious, could easily compete with Nishis and Miris, neither of

whom have a tradition of coordinated labour. No figures are publicly available for the total amounts spent by government on such undertakings, but one can well imagine how many millions of rupees must have been shelled out for the construction of all the mountain roads with permanent surface throughout the Subansiri District. Apa Tani contractors who could supply and control labour must certainly have earned a substantial share of the funds expended, for the experience of wealthy clan heads in directing the work of numerous slaves and hired labourers undoubtedly helped them in recruiting and controlling contract labour. There can be little doubt that it was the influx of government funds through the channels of wage payments which gave the first stimulus to the development of Hapoli as a commercial centre. The profits of contractors enabled Apa Tanis to establish and stock shops, and the wages earned by a broad stratum of Apa Tanis led to the emergence of an adequate clientele patronizing these shops. The explanation for the success of the relatively inexperienced Apa Tanis lies in the fact that government had barred outside merchants from engaging in trade in the hills. While in other parts of India Marwaris, Komtis, and members of other trading castes have infiltrated into most tribal areas and prevented the emergence of any indigenous merchant class, the Apa Tanis were saved from such competition and hence could establish their own business enterprises without being overshadowed from the start by more skilled and more aggressive traders and moneylenders.

While it is difficult to find out the volume of an individual's trading operations or to assess his capital resources, various indications suggest the general level of the trading community's affluence. In the branch of the State Bank of India in Hapoli about 1,200 tribesmen, most of whom are Apa Tanis, maintain current accounts, and in a good many of these there are balances of over Rs 100,000. Some time in 1978, a wealthy, middle-aged man who wanted to marry a young girl as his second wife was persuaded to open a joint account in his own name and that of his bride with an initial deposit of Rs 30,000. His willingness to do so indicates the affluence of some Apa Tani businessmen, an affluence which stands in stark contrast to the poverty of most tribal populations in other parts of India.

The Apa Tanis' success in the commercial field was facilitated by the rapid spread of education, which has led to the emergence of a class of businessmen capable of operating in an economy involving a measure of paperwork. While at the time of the Apa Tanis' initial contacts with representatives of government they hardly knew the meaning of literacy, as early as 1950 government schools were established in the valley, and this enabled children to obtain a sound education irrespective

of parental means. In more recent years parents capable of paying fees have also sent children to independent schools outside Arunachal Pradesh. As a result of all these factors, educational progress has been rapid and literacy is now relatively high. After some years, when teaching had been first in Assamese and later in Hindi, student organizations put pressure on the Legislative Assembly of Arunachal Pradesh to adopt English as the medium of instruction at all levels of education beginning with primary schooling. This move greatly benefited those students who wanted to join universities and other institutions of higher education. Many were accepted for degree courses in a variety of subjects, and by the beginning of 1980 there were already forty-five Apa Tanis with university degrees, while many more students were enrolled in the universities of Gauhati, Dibrugarh, Shillong, and even Delhi. Most of the graduates entered government employment, and in 1978 no less than fifteen served in gazetted posts. Among them were fully qualified doctors and a pilot-officer in the Indian Air Force. If one contrasts this with the lamentable performance of the products of Gond schools in Andhra Pradesh—schools which were established a decade before the first Apa Tanis even began primary education—one realizes how disadvantaged the tribal people of Peninsular India are in comparison with the tribesmen on India's northeast frontier. It could be argued that the Government of India has provided very large funds for the development of a politically sensitive and strategically endangered zone close to the Chinese border, and that the Apa Tanis and other tribesmen of Arunachal Pradesh automatically benefited from the large expenditure in the region. Yet very substantial funds have also been sanctioned by the central government for tribal development in such states as Andhra Pradesh, but these grants were not spent in a manner conducive to bringing the intended benefits to the tribesmen.

One of the causes of the rapid economic and educational development of the Apa Tanis is their freedom from oppression and exploitation by more advanced communities. When the hill regions now forming Arunachal Pradesh were brought under the control of the Government of India, great care was taken not to disrupt the traditional social order, and from the very beginning efforts were made to build up a political structure which would allow the tribesmen to run their own affairs within the framework of the wider Indian political system. At first village and district panchayats were established, and local leaders emerging from these bodies were subsequently appointed as members of a Legislative Assembly which functioned on the lines of the assemblies of the Indian states. Arunachal Pradesh is at present a union territory with a political setup differing only in details

Modern Apa Tani couple; the husband, Kuru Hasang, was a fighter pilot

in the Indian Air Force, the wife owns and manages a pharmacy in Hapoli.

from that of such states as Nagaland and Meghalaya. In February 1978, elections to the Legislative Assembly were held on the basis of universal franchise. Four Apa Tanis, all literate in English, stood as candidates in a constituency which included not only the Apa Tani Valley but also numerous Nishi villages. The candidate of the Janata Party won the seat and was subsequently elected speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Arunachal Pradesh. The ministry consists entirely of tribals from various regions of the union territory, and the making of policy thus lies almost entirely in the hands of tribal leaders. This situation, too, contrasts sharply with conditions in Andhra Pradesh, where the few tribal members of the Legislative Assembly, heavily outnumbered by Hindus and Muslims, are without power and influence, demonstrably unable to influence developments in the tribal areas and to protect their constituents against oppression by non-tribals.

In Arunachal Pradesh the tribesmen are masters in their own house, and after only thirty-six years of contact with government and an even shorter time when any kind of education was available, a very substantial share of government posts is already held by Apa Tanis. In 1978 there were not only 15 Apa Tani officers in gazetted posts, but 342 Apa Tanis served in non-gazetted posts. Of these 115

P. Ette, Circle Officer, Raga, and his wife, a school-teacher; both belong to

the Adi tribe, which is closely akin to the Miris of Raga.

were posted in the Apa Tani Valley, while many worked in other localities in the Subansiri District, and the rest were dispersed over several districts of Arunachal Pradesh. This development, which indicates a progress not matched by any of the tribes of Peninsular India, is, moreover, cumulative, for men in government employment usually have both the opportunity and the incentive to send their children to good schools, with the result that in the next generation even more Apa Tanis will be qualified for posts demanding a mesasure of higher education.

Opponents of any special privileges for tribals, particularly of the exclusion of non-tribal settlers from tribal areas, often put forward the argument that tribals will advance only if they freely mix with other sections of the population. The experience in Arunachal Pradesh demonstrates that this argument is fallacious, for it is precisely the special protection afforded to the tribesmen by the Inner Line policy which has enable the Apa Tanis to achieve within one generation an advancement surpassing any achieved by those Indian tribals whose ancestral homeland has been infiltrated by members of the so-called progressive communities. Events such as the massive alienation of tribal land in Andhra Pradesh are unthinkable in any part of

Arunachal Pradesh, where the indigenous inhabitants are politically sufficiently conscious and powerful to safeguard their rights and to resist any exploitation by outsiders.

Some 15,000 Apa Tanis, constituting only a small percentage of the 467,511 inhabitants of Arunachal Pradesh, already occupy a position of influence and economic power completely out of reach of the more than 100,000 Gonds of Adilabad District, even though in the days of the Gond rajas the latter were a ruling race and long ago acquired such technological achievements as plough, wheel, and animal traction, which even one generation ago were foreign to the Apa Tanis and their tribal neighbours.

There have been changes in the Apa Tanis' social life, but these were gradual and none of them can be described as revolutionary. The Apa Tanis were never ruled by autocratic chiefs, but order was maintained by a system of clan elders and village councils entrusted with such tasks as the organization of seasonal rituals and feasts, mediation in disputes, and the punishment of criminals. Though this system was basically democratic, Apa Tani society was divided into two classes, which I have called patricians and commoners. These two classes were, and largely still are, endogamous, but under the influence of education and new opportunities for commoners in trade and government employment this endogamy seems to be breaking down. In recent years there have been some marital unions between patricians and commoners, though the couples involved still suffer from some discrimination. While a few commoners have become successful traders and have even gained political influence, the members of the leading patrician families have retained much of their wealth and influence. They were the first to take advantage of new educational facilities, and most of them are active in commerce. The most prominent Apa Tani politician, elected speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Arunachal Pradesh in 1978, is the son of a wealthy and highly respected clan elder, and other patrician families have also succeeded in maintaining their status. The abolishment of slavery in 1962 has deprived them of some of their captive labour force, but they received from government compensation for the loss of their slaves, and now employ many of their previous dependants as wage labourers. Some differences in wealth and power have been evened out, but others have arisen as the result of the large profits made by successful businessmen. Several of these have built homes in Hapoli and furnished them partly in modern style, while retaining their old family houses in their villages. The possession of bicycles, motor scooters, and in some cases even jeeps enables them to move freely between their two homes and between the old and the new life-style without showing

any of the symptoms of alienation and disorientation so typical of tribal political leader in states such as Andhra Pradesh.

The sphere of Apa Tani life which has been least influenced by recent developments is that of religion and ritual. Apa Tanis continue to perform public as well as domestic rites in the traditional manner, and even public servants and students residing temporarily outside Arunachal Pradesh make every effort to return to the Apa Tani Valley when their village performs the triannual celebration of the Mloko, the greatest of the seasonal feasts. Unlike such tribes as Gonds and Koyas, who, yielding to Hindu pressure, have given up cow sacrifice, the Apa Tanis show no signs of abandoning their traditional ritual practices, nor has there been any suggestion that the people of the plains of Assam stigmatize them as untouchable because of their habit of eating beef. The self-confidence so characteristic of Apa Tanis and other hillmen of Arunachal Pradesh enables them to resist interference with practices which they consider their own affair and of no concern to anyone outside the tribal community. In this respect, too, the Apa Tanis' attitude sharply contrasts with that of the timid tribals of Andhra Pradesh, whose long-standing experience as victims of oppression and bullying has broken their spirit and taught them the wisdom of complying with Hindu prejudices. Among the Apa Tanis there is as yet no significant impact of Hindu ideas or customs, but it would seem the traditional belief in an underworld, where the departed lead a life identical to that they led on this earth, has been slightly confused by stories of heaven and hell brought back by students in mission schools. However, such novel ideas have not yet had any effect on the ritual practices in which even the most educated participate with undiminished dedication. These, of course, are early days in the contacts with different ideologies, and it is by no means unlikely that the traditional world-view may not indefinitely satisfy the intellectual aspirations of those who study in universities and other institutions of higher learning.

The Apa Tanis are only one of the numerous tribal groups which make up the population of Arunachal Pradesh, and in 1980 I had the opportunity of spending some time among their neighbours, known as the Nishis and the Hill Miris. When I encountered these tribes in 1944 and 1945, their relations with the Apa Tanis alternated between mutually profitable trade contacts and sporadic feuds, often culminating in the capture and holding for ransom of Apa Tanis by Nishis or Miris, or in the raiding of the latter's settlements by Apa Tanis seeking revenge. Though the loss of life was usually not very great in these long-drawn-out feuds, revenge killings did occur, and it was unsafe for any tribesman to enter the land of villages where he had no

friends to offer him protection. Among the slaves of the Apa Tanis there were many of Nishi or Miri origin, usually men or women captured in raids. A few had been taken prisoner by Apa Tanis, but many more were victims of endo-tribal fights between Nishis whose captors had sold them to Apa Tanis.

Today peace reigns among Nishis, Miris, and Apa Tanis, and anyone who experienced the tense atmosphere which prevailed only thirty-five years ago in areas rent by unending feuds must be surprised by the speed with which the Government of India brought tranquillity to this region. The achievement is all the greater as the elimination of feuds and raiding was effected largely without employing armed force. Although at the beginning of the pacification of the region there were a few incidents involving members of the security forces, on the whole law and order was established more by persuasion than by police action, and this stands in sharp contrast to the interminable fights against insurgents in Nagaland. At present men and women of any tribal group can freely move from village to village without running any risk, and many have become used to visiting the plains of Assam for the purpose of petty trade.

Whereas the Apa Tanis, dwelling in large, compact villages, always enjoyed a considerable degree of security as long as they did not venture too far from their home ground, for Nishis the newly gained freedom from the fear of being raided or kidnapped is a relatively novel experience, and one which has transformed their social life. Previously, individual families sought to attain a measure of safety by concluding alliances with men in other villages, and such alliances were based either on marriage relations or on formal friendship pacts which involved the exchange of valuables. Today the need for such individual links no longer exists. Recent political events have ended the lawless state of affairs in which the members of a Nishi household had to fend for themselves, and even co-villagers were under no obligation to come to the rescue of a family attacked by raiders. Quite apart from overall control by the administration, which is capable of imposing sanctions on law-breakers, the past few years have seen the development of a judicial system resting on the authority of village elders, the so-called gaonbura. Among the Nishis their position is an innovation which goes back to the final phase of British rule, when the officers of government selected in a somewhat informal way prominent men as representatives of their villages. After the suppression of violent acts of self-help, which used to be the only way of obtaining redress of grievances, the tribesmen have learned to depend on the gaonbura for the settlement of disputes, and various steps have been taken to regularize their function. In the Raga Circle, for instance, an area which has a large concentration of Hill Miris, the circle

officer—incidentally, himself a tribal—encouraged the gaonbura and panchayat members to lay down certain basic principles for the administration of justice.

In a meeting of village elders drawn from all parts of the circle which was held on 27 February 1980, a number of rules for the settlement of disputes were formulated and unanimously agreed upon. Significantly, the elders decided that anyone trying to bypass their jurisdiction by directly approaching an officer of the administration should be fined Rs 500, which for tribals is a very substantial sum. The rules laid down in the document resulting from this meeting reflect a very liberal attitude insofar as the marriage system is concerned. Thus the list of rules begins with the categorical statement that "child marriage is strictly prohibited" and that a fine of Rs 1,000 would be imposed on the parents of the immature girl as well as on the person marrying her. This is followed by the rule that "nobody can marry a girl against her will" and that "the parent giving her in marriage against her will would be fined Rs 1000." Compared to these rates the fine of Rs 600 for adultery and of Rs 500 for attempted murder seem rather small. No punishment for homicide is laid down because capital offences fall under the jurisdiction of government magistrates. Once a council of tribal elders has pronounced judgement in any of the cases within their purview, an appeal to the circle officer is permitted, but in most instances this representative of government confirms the verdict of the council.

The regulations framed by the tribal elders of the Raga Circle are the first attempt at the codification of customary law by assemblies of tribesmen. In practice most disputes have for long been dealt with by informal gatherings of elders, and it speaks for the broadmindedness and imaginative approach of the government that law enforcement by local bodies is encouraged and the intervention of government officers and courts reduced to a minimum. This policy contrasts with the much more legalistic and far less imaginative attitude of the Government of Andhra Pradesh, which abolished the tribal courts instituted by the Nizam's government, with the result that the tribals are once again subject to the jurisdiction of ordinary courts, the complicated procedures of which they are incapable of comprehending.

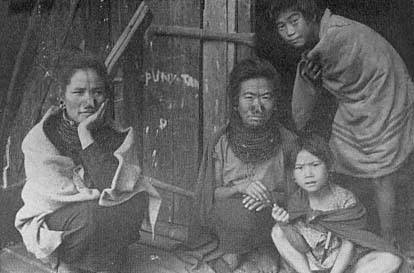

While the Government of Arunachal Pradesh deliberately favours the retention of the greater part of the traditional social order, it has encouraged certain changes in the settlement pattern. Unlike the Apa Tanis, most Nishis and Miris used to live in dispersed settlements, and particularly the former rarely built compact villages. Individual long-houses, sheltering under one roof several families and sometimes up to fifty or sixty people, stood on spurs and ledges, often at a considerable distance from other houses of the same village. Such a scattering

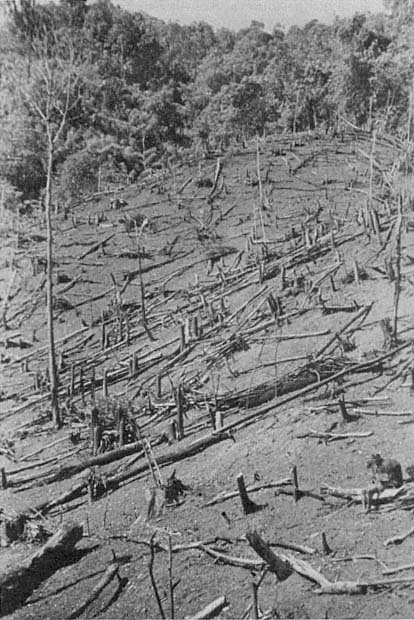

Nishi jhum field cleared of all brush-wood; the stumps of trees are left in the

ground and serve to prevent erosion. The crop will be sown in between the

stumps and trunks of felled trees.

Harvest on a Nishi jhum field. The ears of millet and rice are cut off the

standing crop and carried home in baskets.

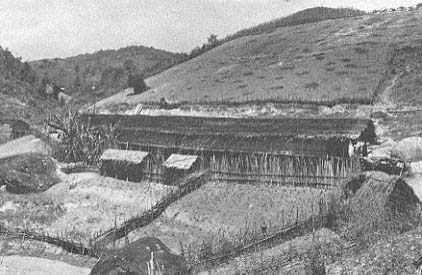

Miri house in Godak, Raga Circle. The house contains one undivided hall with

separate hearths for individual families.

of homesteads made the provision of public facilities difficult, and the government hence adopted a policy of regrouping villages so that as many people as possible could benefit from the establishment of schools and health centres and, above all, could gain access to piped water and of late also electricity. The regrouped villages are still not very large, the number of houses seldom exceeding forty, and there has been no change in the type of houses. These are still built on wooden piles and contain one large undivided hall with a number of hearths, each used by one unit of the joint family inhabiting the house. Regrouping has occurred mainly in areas where a motorable road acts as an incentive to move from mountain sites to the vicinity of such a line of communications.

One example of such a population movement is the Panior Valley, for the road linking the Apa Tani Valley and such large Nishi villages as Jorum and Talo with the Assamese town of North Lakhimpur runs for a long stretch through this valley. In the 1940s this valley was covered in dense tropical jungle difficult to penetrate even on foot, and several Nishi settlements were perched on the crest of hills high above the river level. The inhabitants cultivated the upper parts of the hill slopes and descended into the valley only for fishing and hunting, or when visiting settlements on the other side of the valley. Within

Nishi long-house in Talo village standing between permanently cultivated and

regularly manured fields and garden plots.

the past ten years most of these hill-top settlements have been abandoned, and the Nishis have moved down into the valley, where they build houses close to the motor road. They still practise shifting cultivation on hill slopes situated within their traditional territory, but wherever the valley broadens and offers possibilities for permanent cultivation, they grow rice in irrigated fields. Those in settlements close to the plains have also begun to use ploughs and bullocks for tilling their land.

This Nishi tribe extends over a large area of diverse climate and configuration, and the altitude of settlements ranges from a few hundred feet to well over six thousand feet. In the 1940s I had found many parts of the Nishi country sparsely populated, and the frequency of feuds and revenge killings then undoubtedly acted as a check on the growth of the population. This check has now been removed, and the availability of medical services has limited the effect of epidemics, which on occasions took a heavy toll. An increase in the Nishi population is hence inevitable and will certainly be reflected in the figures of the 1981 census. Even before these figures are available one can gauge the magnitude of the problem by comparing the present size of villages with that observed in 1944. The village of Talo, whose land adjoins the Apa Tani Valley, for instance, consisted then of fewer than 40

houses. In 1978 I counted 176 houses and the number of hearths, which mirrors the number of separate nuclear families, was then 1,077, while the size of the population was estimated to be 2,076. My Nishi informants stated emphatically that few of the villagers had migrated to Talo from other places and that the expansion of the village was due solely to the natural growth of the families of old residents. Yet there has probably been a considerable influx of women born elsewhere, for the men of Talo were rich and could marry many wives by paying high bride-prices. Even in 1944 there was a man who had nine wives, and men with five wives were not unusual in Talo.

The increased population of Talo can be maintained because the village land comprises a large expanse of level ground which has been transformed into irrigated rice fields. Following the example of their Apa Tani neighbours, the Nishis of Talo have been raising wet rice for some time, but the acreage under irrigation has now greatly increased. Every side valley with a trickle of water and even narrow ravines have been adapted for the construction of rice terraces, and much hard work has gone into this transformation of the natural environment. The traditional slash-and-burn cultivation is also being practised, and there is still some land for the potential expansion of this type of tillage.

Yet not all Nishi villages are as favourably placed as Talo, with its large area of level irrigable land. In neighbouring Jorum the population has also grown but land has become scarce, and within the past ten to fifteen years four colonies have branched off and moved to sites close to the periphery of Jorum land. The members of these new settlements have converted former communal land into rice terraces, and these they now regard as their individual property. This is not contrary to Nishi custom, and as long as land was plentiful such practices were generally accepted. But with the increasing population growth, land is gradually becoming an object of conflict, and in Jorum I was told that whereas previously men used to quarrel about women and mithan most disputes now arise from competition for land.

A novel source of dissension among Nishis who inhabit the hills adjoining the plains of Assam in the influence of Christian missions on young people educated in their schools in places such as North Lakhimpur and Tezpur. While numerous Hindu children go to such schools without being induced to change their religion, a good many Nishi youths have been converted to Christianity. This in itself need not have created any difficulty, for Nishis, like most tribals, are not greatly concerned about the religious beliefs of their fellow-tribesmen, and if the Christian converts had been equally tolerant their rejection of traditional Nishi religion might have been ignored by the great mass of conservative tribesmen. However, the converts seem to have

been lacking in tolerance and tact, and educated young men of villages affected by the ideological split to whom I spoke in 1980 complained bitterly that Christians deliberately disrupted the harmony of community life. They allegedly refused to share the houses of adherents of the old faith, and this meant that old parents were abandoned by their converted children, who claimed that they could not stay in dwellings where "devils" were worshipped and the meat of sacrificial animals was consumed. My informants insisted that the missions encouraged the establishment of separate settlements for Christians, and that the Christians refused to participate in village festivals, thereby demonstrating their dissociation from the tribal community. It was alleged, moreover, that converts, not satisfied with this symbolic withdrawal from village life, went a step further by abusing and physically attacking priests as they invoked the gods in the performance of traditional Nishi rituals. Enraged by such interference with hallowed religious practices, some Nishi youths took the offensive and destroyed some huts used by Christians for their prayer meetings.

Nishi teachers at the government high school in Yazali, who were members of a youth organization formed to promote traditional tribal culture, told me how frustrated they were because they could not match the large sums lavished by the missions on propaganda which is undermining the old Nishi life-style. The missionaries concerned are Indian nationals, and though the Inner Line rules prevent them from entering Arunachal Pradesh for the purpose of proselytization, they allegedly pay young Nishis to spread Christianity in their home villages, and a commission of Rs 200 is said to be paid to any convert who induces another Nishi to embrace Christianity. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the case may be, it is widely believed that there are young Nishis who, after having left mission schools, live in comfortable circumstances without holding any official position or engaging in any normal occupation, such as farming, teaching, or running a business. Adherents of the traditional faith resent the subsidizing of such young people, whom they regard as hostile to their ancestral ideology and social customs.

The conflict created by the impact of Christianity on the Nishis of the Subansiri District stands in striking contrast to the developments in the neighbouring Kameng District, where tribal groups such as the Khovas have come under the influence of Tibetan Buddhism. In their general life-style the Khovas, a tribe of shifting-cultivators adjoining Monpas and Sherdukpens, resemble Nishis in their economy and in the character of their traditional religion. Among the Khovas there is a spontaneous trend towards Buddhism; in two villages small gompa are under construction, and the villagers have invited Monpa lamas to

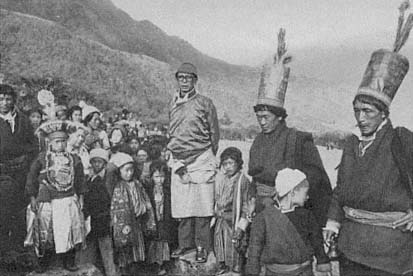

Monpa men of Sangti in Dirang Circle of Kameng District; they wear

rain-resisting caps made of yak hair.

perform Buddhist rituals. A prominent headman of the last generation who was known to be a believer in Buddhism is said to have assisted in the establishment of a gompa in Bomdila. Unlike the Christian converts among the Nishis, those Khovas who are attracted to Buddhism do not opt out of the social life of their community and continue to participate in the traditional tribal rituals.

In the same way the Sherdukpens combine their adherence to Mahayana Buddhism with the communal worship of tribal deities whose cult lies in the hands of priests entirely distinct from the lamas in charge of the large gompa furnished and decorated in the style of Tibetan gompa . Among the Monpas, too, elements of the ancient Bon religion coexist with the dominant Buddhist faith, and the parallel practice of both religions within the same communities has not sparked off any conflicts comparable to those which threaten to destroy the social fabric of Nishis affected by religious rivalries.

In the field of higher education the Nishis and Miris have not yet caught up with the Apa Tanis, but their progress is nevertheless remarkable compared to the educational achievements of such tribes as the Gonds and most other tribal groups of Peninsular India. In 1980 there were some thirty university graduates among the Nishis and Miris of the Subansiri District, and several youths and girls were en-

Sherdukpen couple of Rupa in ceremonial dress; the wife wears a brocade

hat of Tibetan style.

rolled in degree courses in institutions outside Arunachal Pradesh. The speed of the educational and political development of the Nishis can be measured by the fact that a member of that tribe by name of Tada Talang, born in 1944 in Nyapin, a remote village south of the Khru Valley, is now education minister of Arunachal Pradesh. He told me that while at present teachers recruited from various parts of India were still on the staffs of many schools, soon enough trained tribal teachers would be available to make the employment of teachers from outside Arunachal Pradesh unnecessary. At the same time, he demonstrated his realism by explaining that at this stage government must consolidate rather than expand primary education. In the first enthusiasm of providing education for all children of school age, numerous schools were opened and teachers appointed, but the supply of essential equipment such as books and slates could not keep pace with this rapid expansion. The minister emphasized, therefore, very reasonably, that existing schools must be properly equipped before there was any point in establishing new schools.

Having experienced how in Andhra Pradesh educational policy was drawn up and repeatedly changed without any consultation with the tribals whose children were ultimately affected by the planning of the school system, I was impressed by the sound and responsible attitude

Monpas of Tawang during a village festival involving a ritual riding display.

of a relatively young man belonging to the first generation of literate Nishis and already in charge of a ministry controlling education throughout Arunachal Pradesh.

My respect for tribal leaders grew even more when a few weeks later I had a chance to discuss educational policy with the former Chief Minister Pema Kando Thondung, M.P., who by that time had been elected to represent the people of Arunachal Pradesh in the Indian Parliament. He belongs to the numerically small but culturally advanced community of Sherdukpens and evinced a breadth of vision and a refreshing realism which I have not often encountered among Indian politicians. Though his career has been little short of meteoric, he was free of all pomposity and seemed to possess a captivating sense of humour. The Sherdukpens, whose total number was 1,639 at the time of the 1971 census, have been prominent in public life, and the success of their leaders in state and national elections shows that in the politics of Arunachal Pradesh personal qualities count for more than the size of the community which backs a candidate in an election. Pema Kando Thondung's predecessor as member of parliament was also a Sherdukpen, and in 1979 another member of the tribe, Nima Tsiring Khrime, was elected to a seat in the Legislative Assembly of Arunachal Pradesh, defeating candidates from numerically very much stronger tribal groups.

Monpa priests of the indigenous, pre-Buddhist Bon religion with a crowd

of villagers celebrating a festival in honour of local deities.

The spectacular progress of Apa Tanis, Nishis, Sherdukpens, and other tribes of Arunachal Pradesh within the past thirty years establishes beyond any doubt the capacity of Indian tribal populations to attain the same level of education, economic efficiency, and political maturity as any other ethnic group within the wider Indian society. The fact that the enlightened policy of the Government of India vis-à-vis the hillmen of the northeastern frontier regions could bring about so rapid a transformation of archaic and in some respects barbaric societies highlights the failure of the tribal policies of the governments of many of the Indian states. For none of these governments provides its aboriginal tribes with facilities similar to those available in Arunachal Pradesh, nor do they effectively assist them in their struggle for an existence free of exploitation and domination by powerful vested interests. Unless we were to argue that the tribes of Arunachal Pradesh are by nature and heredity equipped with superior mental qualities, their performance, outshining most other tribal populations, must be attributed to favourable circumstances and to the historical accident of their relatively late emergence from an isolation which provided them with physical protection from subjugation by economically and politically more advanced ethnic groups. The tribesmen of Arunachal Pradesh were fortunate that at the time when their isola-

tion finally came to an end they benefited from a liberal policy framed by the distinguished anthropologist Verrier Elwin and powerfully supported by the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Had a similar policy been consistently applied to the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh, the fate of Gonds, Koyas, Kolams, and Konda Reddis would also have been a happier one, but we have seen that there measures taken for the benefit of tribal populations in the 1940s were reversed when political pressures created an atmosphere unfavourable to the indigenous tribesmen. Thus tribes such as Apa Tanis and Gonds—to take only two typical examples—stand today at opposite ends of a spectrum which reflects the various possibilities for the development of tribal societies: while the Apa Tanis are clearly set on an upward path, the Gonds are threatened by an apparently irreversible decline in their fortunes.