The Resurrection Frieze.

Although some of the figures in the Resurrection frieze (nos. 11–19, Plates IIIa and IVa) have been heavily restored, careful examination revealed that much of the original sculpture has survived.[10] Even though some of the figures appear severely recut (nos. 11b, 12b, and 13a, Plate IIIb), and many losses of both original and nineteenth-century carving have occurred, with few exceptions either the original pose and gestures of the figure survive, or fragments—some still extant, others visible in earlier photographs—verify the poses and gestures as restored. In fact, the one figure that belongs almost entirely to the nineteenth-century rests on a fragment of the original right buttock—a detail authenticating at least the seated pose (no. 17a, Plate IVb). In the same figure the bent left leg, a second fragment surviving from the twelfth century but now hidden by the nineteenth-century right arm and sarcophagus lid, confirms the restoration of this resurrected figure seated with her back to the central figure of Christ.

Although not one head has survived in the frieze, a number of torsos in proof condition deserve special note (see nos. 11c, 12a, and 12c, Plate IIIa-b, and nos. 18b and 19c, Plate IVa-b). The natural proportions, lively poses, and subtle modeling of those bodies show the artist's respect for and knowledge of human anatomy—a true reflection of the new attitudes that distinguish the nascent Gothic style. Several of the figures deserve further attention either because of their iconographical and stylistic importance or because they reveal techniques used by the restorer.

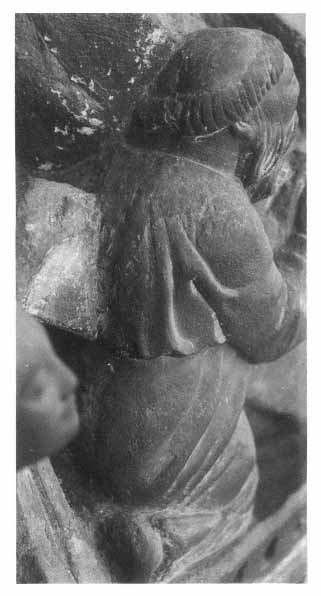

Fig. 10.

Oblique view of Suger kneeling at the feet of Christ. Detail

of frieze of the Resurrected Dead, lintel zone, left, no. 14

Kneeling Figure of Suger

Enough remnants of the original sculpture survive to reconstruct the silhouette of the twelfth-century figure identified as Suger (sarcophagus no. 14, Fig. 10 and Plate IIIa) and to verify his kneeling pose at the feet of Christ. A single nineteenth-century inset encompasses the head, torso, arms and hands, and the right upper leg. The joining of the inset, sometimes lost under heavy white mortar and in roughened stone, becomes visible on the top of Suger's head despite an overlay of mastic (Fig. 10). The joint continues down the middle of the back of his head, shoulders, back, and buttocks, with the mastic overlay especially heavy across his shoulders. The well-defined joint follows the contour of

the right heel and calf, proceeds on a diagonal from his rump to the top of the knee, then turns upward at an acute angle to continue its course along the inside of his right thigh. The joint can then be traced with difficulty in the rough twelfth-century stone beneath the sleeves below the forearms, but it emerges clearly between the fingertips of the two hands. The twelfth-century remnants, although entirely recut, include the left thigh, right lower leg and foot, and a sliver of stone that forms the left buttock, back, shoulder, left side of the skull, and fingertips of the left hand. Those vestiges testify to the existence in the original iconographical program of this kneeling figure with hands in prayerful supplication. With the pose authenticated by the twelfth-century silhouette, the identification of the figure rests on the sole reference to the central tympanum in the writings of Abbot Suger. He mentioned an inscription, now lost, that originally appeared in superliminari (on the lintel):

Receive, O stern Judge, the prayers of thy Suger;

Grant that I be mercifully numbered among thy own sheep.[11]

Suger's sarcophagus appears so completely recut that no traces of the twelfth-century decoration survive, but behind the kneeling figure, the twelfth-century lid of his sarcophagus has retained its original patina. A comparison of Suger's smooth-shaven sarcophagus with the two on the far right (nos. 18 and 19, Fig. 11), indicates the type of ornamental detail erased by recutting. Beading surrounds every aperture in sarcophagus no. 18, and an incised line accents each tiny lancet piercing the surface of no. 19. Traces of decorative beading and outlining survive on three others (nos. 11, 12, and 15, Plates IIIa-b and IVa-b), but only the two on the far right retain pristine twelfth-century surfaces. Presumably similar details embellished the architectural elements of the other four clean-shaven sarcophagi.

Figure of a Bishop or King

This figure (sarcophagus no. 16a, Plate IVa) raises interesting iconographical questions that cannot be answered with certainty but which seem worth considering. The diagram shows insets, recutting, and a new head crowned with a poor approximation of a twelfth-century bishop's or abbot's miter. Although the height of the headgear as restored seems correct for a miter, it also vaguely

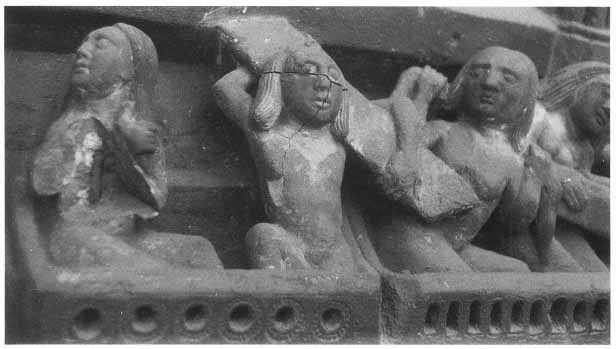

Fig. 11.

Frieze of the Resurrected Dead. Detail of lintel zone, right, nos. 18a-b and 19a-b

suggests the profile of a crown. The headdress also lacks the lateral peaks and the lappets that characterized twelfth-century miters, although the recutting and mastic overlay on the shoulder could have eliminated all traces of the lappets. The nineteenth-century hand, now lost, was raised, but not in the gesture of blessing appropriate to a bishop. Earlier photographs show the hand open, palm facing out, in a gesture of adulation or acclaim now impossible to verify. Neither the gesture nor the attribute held in the left hand resolves the identify of the figure. The shape of the attribute, a small round object capped with a worn and poorly articulated node, suggests either an orb or a pomegranate. The orb, a royal symbol, should be carried with the emblem upright, but here the small protuberance tilts forward. Therefore it is probably a pomegranate, an attribute equally appropriate for a resurrected king or bishop in expectation of immortality.[12]

Mutilated Figure

The loss of a portion of the nineteenth-century inset that replaced the head, arms, and chest of this figure (sarcophagus no. 18a, Fig. 11 and Plate IVb) demonstrates to perfection some of the techniques employed by the restorer. The triangular wedge that has fallen away reveals not only the surface of the old stone prepared to receive the inset, but also the upper portion of the pinning dowel still set into a hole that formed a pocket for the mortar (Fig. 11). The area,

a gaping inverted V, shows the surface of the twelfth-century stone smoothed and cut away on an inclined, stepped-back plane nearly to the level of the navel. The lost inset originally replaced the head, shoulders, upper torso, and all but the left elbow of the folded arms. Certainly too large in relation to the scale of the figure, the metal dowel, which had expanded and contracted with seasonal temperature changes, finally caused the loss of a portion of the restoration. Although the legs, hips, and lower abdomen consist of good unrecut twelfth-century carving, not enough survives to reconstruct the original pose. The remnant of the left elbow, which required a bent left arm, makes the arrangement plausible, if not certain.

Contorted Figure

The adjacent figure in the same sarcophagus (sarcophagus no. 18b, Fig. 11 and Plate IVb) reveals an earlier stage in the degenerative process, caused by the expansion and contraction of the pinning dowel. The splintering of the stone has already resulted in the loss of a wedge of old stone over the right rib cage (Fig. 11). A diagonal fracture runs from the upper right corner of the scar and continues through the joint of the nineteenth-century head at the base of the neck, across the chin, mouth, and into the left cheek, where it ends at the transverse fracture that bisects the restored head. Hairline cracks, portending the loss of another portion of the figure, define another rectangular section of old stone on the right side of the chest.

Because the figure provides one of the best-preserved examples of the lively twelfth-century figurate style and of the formal skill of the sculptor of the Resurrection frieze, its impending disintegration seems particularly unfortunate. The marvelously contorted but entirely plausible arrangement of the arms, the diagonal thrust of the lightly modeled torso, the bent right leg tensed to assist the upward impulse implicit in the right hand, not only reflect the physical effort necessary to raise the sarcophagus lid and emerge from the grave, but also reveal the artist's concern for anatomical reality, as well as his skill in rendering it.

Hair-Pulling Figure

In this figure (sarcophagus no. 19a, Fig. 11 and Plate IVb) another twelfth-century pose has survived, spared by both the iconoclasts and the restorer, who

replaced only the head and lightly recut the left hand (Fig. 11). The new head joins the body at the base of the throat; the lateral lines of joining conform to the contours of the head. The fists grabbing the locks of hair proved original—a lively conceit with a counterpart in gesture at the opposite end of the Resurrection frieze.

Coquettish Woman Adjusting Her Coiffure

Except for her head, left forearm, and hand, the figure of the woman (sarcophagus no. 11b, Plate IIIb) appears well preserved. Her acutely bent left elbow survives from the original carving and, as the factor determining the position of the new left forearm, authenticates her natural and feminine gesture. The pose suggests that at the moment of resurrection, the woman's first thought was for her appearance. Nearly freestanding, her delicately modeled body, naturally proportioned and anatomically correct, testifies to the artist's respect for the integrity of the human figure.

As a whole, differentiated not only by pose but also by sex, and even reflecting psychological differences, the figures of the frieze of the Resurrected Dead express the artist's concern for and awareness of traits that would distinguish individual types. The eye traveling across the lintel zone finds the coquette, the glutton, the demure, the pious, the vigorous, the lowly, and the mighty all represented and characterized in this animated row, awaiting judgment.

The artist responsible for the Resurrection frieze also carved other sections of the portal. We will gradually discover sculpture attributable to his hand in the lunette of the tympanum, in the figures on axis in the four archivolts, in the scenes of the Blessed and Damned on the innermost archivolt, and on the two jambs of the doorway. We have noted that in the Resurrection frieze he carved figures of natural but solid proportions that were anatomically correct, delicately modeled, and carefully differentiated. His treatment of draperies in the clothed figures and individualistic handling of drapery conventions set him apart from the two other masters whose work can be identified in the central portal. We will call this artist the Master of the Tympanum Angels, because those four figures represent his crowning achievement. The second master, styled the Master of the Apostles, carved the row of figures above the Resurrection

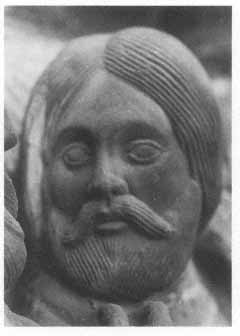

Fig. 12.

Nineteenth-century head, view from left.

Detail of Apostle no. 33, tympanum, far

right

frieze, but not the central figure of Christ. As we survey the sculptural ensemble and perceive the stylistic proclivities and preferences embodied in the work of each master, evidence will accumulate to attribute the figure of Christ to a third artist, the Master of the Elders (or patriarchs), who was responsible for those twenty-four figures in the three outer archivolts.