Chapter 4—

Ritual Language, New Music Encounters in the Academy of Domenico Venier

The previous two chapters have struggled to construct narratives from records of musical patronage that are sketchy at best. My approach has necessarily been bifocal, reading above for concrete particulars and below for deeper cultural meanings, while looking to the dialogics of vernacular exchange to mediate between them. Here I confront a different set of problems in the situation of literary patronage — a patronage at once of and by literati. These figures recorded their ideas and projects in the very media of poems, letters, and dialogues through which I tried to decipher hidden subtexts relevant to musical patronage. They devised the representations of themselves in the same texts in which they pretended to lay themselves bare, manipulating the claims avowed at the outer face of the text. Like the literary critic, the historian must therefore read surface for subsurface, always keeping in view the pressures, pleasures, and performative impulses in which such claims were implicated.

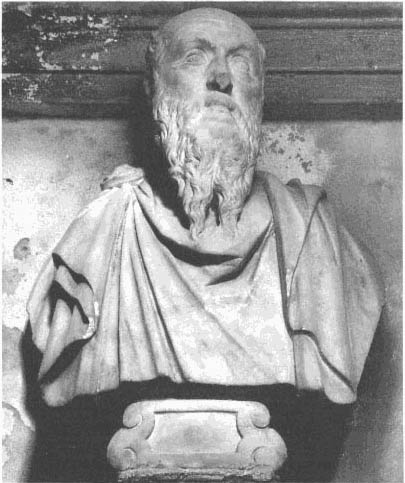

This chapter explores the most prominent literary patron at midcentury, a Venetian patrician named Domenico Venier. Venier lived from 1517 until 1582 and presided for virtually all of his adult life over the most renowned vernacular literary academy in Venice.[1] Consolidated around the mid-forties, the academy became the

[1] The secondary literature on Venier and his circle is scant. The chief work is Pierantonio Serassi, ed., Rime di Domenico Veniero senatore viniziano raccolte ora per la prima volta ed illustrate (Bergamo, 1751), which includes the unique edition of his poetic works as well as a biography. A new edition by Tiziana Agostini Nordio of the Centro Interuniversitario di Studi Veneti, under the general direction of Giorgio Padoan, is currently in preparation. The brief entry on Venier's academy in Michele Maylender, Storia delle accademie d'Italia, 5 vols. (Bologna, 1926-30), 5:446, is based on Serassi's work. A few poems are anthologized in Daniele Ponchiroli, ed., Lirici del cinquecento (Turin, 1958), pp. 105-12, and Carlo Muscetta and Daniele Ponchiroli, eds., Poesia del quattrocento e del cinquecento (Turin, 1959), pp. 1373-77. For a critique of how cinquecento Petrarchists, including Venier, have been anthologized, see Amedeo Quondam, Petrarchismo mediato: per una critica della forma antologia (Rome, 1974). On the academy's effects in the second half of the century see some of the literature on Veronica Franco, whom Venier patronized in the 1570s: Riccardo Scrivano, "La poetessa Veronica Franco," in Cultura e letteratura nel cinquecento (Rome, 1966), pp. 195-228; Margaret F. Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan: Veronica Franco, Citizen and Writer in Sixteenth-Century Venice (Chicago, 1992), pp. 89-94, 154-55, 179-80, and passim; and Alvise Zorzi, Cortigiana veneziana: Veronica Franco e i suoi poeti (Milan, 1986), pp. 59-90. Discussions of Venier's own poetry are taken up in Dámaso Alonso and Carlos Bousoño, Seis calas en la expresión literaria española (prosa, poesía, teatro), 4th ed. (Madrid, 1970), pp. 51 and 92-94; Edoardo Taddeo, Il manierismo letterario e i lirici veneziani del tardo cinquecento (Rome, 1974), pp. 39-70; and Francesco Erspamer, "Petrarchismo e manierismo nella lirica del secondo cinquecento," in Storia della cultura veneta: il seicento, vol. 4, pt. 1, ed. Girolamo Arnaldi and Manlio Pastore Stocchi (Vicenza, 1983), pp. 192-97.

city's crossroads for local and foreign writers and remained so until Venier's death. Nowadays Venier's reputation has dramatically faded, only barely revived by renewed interest in the phenomena of lyric production, dispersion, and collection.[2] Yet in his own day his life was marked by constant accolades that came to assume near-mythic proportions.[3] His fame as an organizer of literary culture continued posthumously — long enough to have been included in the 1640s as interlocutor with Apollo, Aristotle, Plato, Plutarch, Seneca, Guicciardini, and others by an anonymous Florentine satirist lampooning the conversations of the Accademia degli Unisoni.[4]

Let me begin to sketch some formative details of Venier and his circle of patrician friends as they developed in the second quarter of the century. Venier's coterie had been largely schooled together in the 1520s. By the 1530s they had already begun to fashion themselves as virtual heirs apparent to Venice's literary scene. Meanwhile most of them held civic offices and pursued various business interests. In 1546 a worsening case of gout seems to have prevented Venier from continuing to hold offices (as noblemen normally would), and at the same time his academic activities moved into high gear.[5] His palazzo at Santa Maria Formosa quickly became the

[2] See, for example, Roberto Fedi, La memoria della poesia: canzonieri, lirici, e libri d'amore nel rinascimento (Rome, 1990), esp. pp. 43-46.

[3] The large number of sixteenth-century references mentioned below represents merely a fraction of what exists. Despite this, Venier's academic activities have not been well documented elsewhere — hence the rather heavy documentation that follows.

[4] This comes from a manuscript of satires entitled "Sentimenti giocosi havuti in Parnaso per L'Academia degli Unisoni," I-Vmc, Misc. P.D. 308C/IX. Other manuscript copies of these satires are listed by Ellen Rosand, "Barbara Strozzi, virtuosissima cantatrice: The Composer's Voice," JAMS 31 (1978): 250 n. 31.

[5] According to the electoral records of the Great Council, Venier was voted in as a senator on 26 October 1544 for a sixteen-month term that ended on 15 March 1546, after which he apparently did not serve for many years; I-Vas, Segretario alle voci, Elezioni del Maggior Consiglio, registro 2 (1541-52), fols. 40'-41. Zorzi summarizes the various offices held by Venier in Cortigiana veneziana, pp. 83-84 (without citing documents that provide the information but giving an overview of pertinent archives). The results of my archival searches have thus far agreed with Zorzi's information. On senatorial ranks see Robert Finlay, Politics in Renaissance Venice (London, 1980), pp. 59-81, and the glossary, p. xvi, and Oliver Logan, Society and Culture in Venice, 1470-1790: The Renaissance and Its Heritage (New York, 1972), p. 25.

The secondary literature alluding to Venier's academy shows some discrepancy concerning the academy's date of origin. Serassi's claim of 1549 is based on the far-fetched reasoning that Michele Tramezzino's dedication to Venier of 1548 (see n. 29 below) omits to mention the illness that ostensibly prompted Venier to drop out of political life and focus full time on cultural activities. Serassi's date is repeated in Pompeo Molmenti, La storia di Venezia nella vita privata dalle origini alla caduta della repubblica, 7th ed., 3 vols. (Bergamo, 1928), 2:374. Already in May 1548, however, Pietro Aretino referred to "l'Accademia del buon Domenico Veniero, che in dispetto della sorte, che il persegue con gli accidenti delle infermità, ha fatto della ornata sua stanza un tempio, non che un ginnasio" (the Academy of the good Domenico Venier, who in spite of fate, which persecutes him with the misfortune of illness, has made of his ornate salon a temple, not a mere schoolroom); letter to Domenico Cappello, Lettere, 6 vols. (Paris, 1609), 4:274, quoted in Girolamo Tiraboschi, Storia della letteratura italiana, vol. 7, pt. 3 (Milan, 1824), p. 1684. And as early as 1544, Bembo referred to Venier's "dilicata complessione" (see n. 19 below).

meeting place for writers of every stripe: patrician diplomats and civil servants, cultivated merchants, editors, poets, classicists, theorists, and playwrights.[6] Some of them were professional, others amateur, and (most strikingly) many had no clearly defined social-professional position of any sort.

Many references in the prolific occasional literature of the time make note of the various personalities involved. Among the closest to Venier were the patrician poet Girolamo Molino, whose posthumous biographer counted Venier's salon the most influential in Molino's experience,[7] and the letterato Federigo Badoer — an exact contemporary, though intermittently much occupied with diplomatic missions prior to his founding of the Accademia Veneziana in 1558.[8] Others included the Paduan scholar Sperone Speroni; a host of vernacular poets like Fortunio Spira, Anton Giacomo Corso, Giovanni Battista Amalteo, and Giacomo Zane, and others whose lyrics appeared in the copious poetic anthologies of midcentury; and polygraphs like Girolamo Parabosco and Lodovico Dolce.[9] Parabosco named many of these in a much-cited capitolo to Count Alessandro Lambertino, along with the satirist Aretino, who had at least a tangential relationship to the group.[10]

[6] Francesco Flamini, Storia letteraria d'Italia: il cinquecento (Milan, 1901), identified the location of Venier's palazzo as the Venier house at Santa Maria Formosa (p. 180) — i.e., that of Sebastiano Venier who was made famous by his victories against the Turks at Lepanto in 1571 — an assertion echoed elsewhere in secondary literature. Venier's tax report, I-Vas, Dieci savi alle Decime (166-67), b. 130, fol. 653 (located by David Butchart and graciously shared with me), confirms the general location, but the genealogies give no reason to think that the house was the same.

[7] In naming Molino's many friends and colleagues in Venice, Giovan Mario Verdizzotti wrote that "of all these honored conversations he frequented none more often than that of Domenico Venier . . . whose house is a continuous salon of talented people, both noblemen of the city and all sorts of other men in the literary profession and others rare and excellent" (di tutte queste honorate conversationi niuna egli più frequentava, che quella del M. Domenico Veniero . . . la casa del quale è un continuo ridutto di persone virtuose così di nobili della città, come di qual si voglia altra sorte d'huomini per professione di lettere, & d'altro rari, & eccellenti); Molino, Rime (Venice, 1573), p. [7]. Sansovino listed him among the other great Venetian writers of the time ("M. Gieronimo Molino è noto a ciascuno, però non ve ne parlo"), as he did Venier — both through the droll mouth of "Venetiano"; Delle cose notabili che sono in Venetia. Libri due, ne quali ampiamente, e con ogni verità si contengono (Venice, 1565), fol. 33'. Molino lived from 1500 until 1569.

[8] Badoer (1518-1593) was precisely contemporary with Venier. A satiric capitolo, in praise of Badoer by Girolamo Fenaruolo to Venier, recounts how Fenaruolo, while walking through the Merceria, hears the news that Badoer has been made Avogadore; Francesco Sansovino, Sette libri di satire . . . Con un discorso in materia de satira (Venice, 1573), fols. 196-200'.

[9] Most of the writers listed by "Venetiano" as being in Venice can be linked to Venier: in addition to "Bargarigo" [sic, i.e., Niccolò Barbarigo] and Molino it includes Gian Donato da le Renghe, Pietro Giustiano (historian), Paolo Ramusio, Paolo Manutio, Giorgio e Piero Gradenighi (Gradenigo), Luca Ieronimo Contarini, Di Monsi, Daniel Barbaro, Agostino da Canale (philosopher), Bernardo Navaiero (Navagero), "prestantissimo Senatore," Iacomo Thiepolo, Agostin Valiero, Lodovico Dolce, Sebastiano Erizzo" (fols. 33'-34). "Et se voi volete Huomeni forestieri," he continues, "ci habbiamo M. Fortunio Spira, gran conoscitor de tutte le lingue, M. Carlo Sigonio che legge in luogo d'Egnatio che fu raro a suoi dì Bernardo Tasso; Hieronimo Faleto orator di Ferrara, Sperone Speroni habita la maggior parte del tempo in quest' segue. Il vescovo di Chioggia non se ne sa partire. Girolamo, Ruscelli, dopo molto girar per Italia, finalmente s'è fermato in questa arca" (Delle cose notabili, fol. 34). We will encounter many of these figures below.

[10] Aretino's acquaintance with Domenico and other members of the Venier family goes back to the 1530s; see Aretino's letters to Lorenzo Venier of 24 September 1537 (Aretino, Lettere 1:163), to Gianiacopo Lionardi of 6 December 1537 (Lettere 1:233'-34), and to Domenico of 18 November 1537 encouraging his literary talents (Lettere 1:190-190').

Andarò spesso spesso a ca' Venieri, I'll go ever so often to the Veniers' house

Ove io non vado mai ch'io non impari Where I've never gone for four whole years

Di mille cose per quatr' anni intieri; Without learning about a thousand things.

Per ch'ivi sempre son spiriti chiari, For eminent spirits are always there

Et ivi fassi un ragionar divino And folk reason divinely there

Fra quella compagnia d'huomini rari. Among that company of rare men.

Chi è il Badoar sapete, e chi il Molino, Who Badoer is you know, and who Molino is,

Chi il padron della stanza, e l'Amaltèo, Who the father of the stanza, and Amalteo,

Il Corso, lo Sperone, e l'Aretino. Corso, Sperone, and Aretino.

Ciascun nelle scienze è un Campanèo, Each one in the sciences is a Capaneus,

Grande vo' dire, et son fra lor sì uguali, Great, I mean, and so equal are they

Che s'Anfion è l'un, l'altro è un That if one is an Amphion, the other is an

Orfeo.[11] Orpheus.

Parabosco composed the capitolo as a bit of salesmanship, hoping to induce Lambertino to visit the city, and he bills the salon as one of the town's featured spots.[12] Some of the writers he mentions are practitioners of high lyric style, like Molino and Amalteo; others, like Aretino, dealt in satire and invective; and still others — Speroni for one — in philosophy. The mix seems representative, since everything points to a scene that was generously eclectic.

Some measure of this eclecticism clearly extended to include music. Although the academy's agenda was essentially literary, Parabosco's presence in its regular ranks is telling. He was one of several stars from the San Marco musical establishment who had connections with Venier's group, which also included various solo singers — probably of less professional cast — who declaimed poetry to their own accompaniments. Not surprisingly, some of the literary members had strong musical interests too — interests that can be documented through sources outside Venier's immediate group.

As the major center for informal literary exchange in mid-cinquecento Venice and one that embraced musicians, Venier's academy articulates concerns relevant to the

[11] La seconda parte delle rime (Venice, 1555), fols. 61-61'.

[12] Parabosco was involved with Venier from at least 1549 when Aretino mentioned to Parabosco in a letter from October of that year that it was Venier who had introduced them ("avermi insegnato a conoscervi"); Lettere sull'arte di Pietro Aretino, commentary by Fidenzio Pertile, ed. Ettore Camesasca, 3 vols. in 4 (Milan, 1957-60), 2:308. In July 1550 Parabosco wrote Venier a letter of praise and affection from Padua, which suggests by its wording that the two had had a more extensive correspondence: "ho ricevuto una di V.S. a li ventisette del passato" (I received one of your [letters] on the 27th of the past [month]); Il primo libro delle lettere famigliari (Venice, 1551), fols. 4-4'. In 1551, finally, Parabosco published a letter to one Pandolpho da Salerno characterizing the group around Venier as a definite body: "Io sto qui in Vinegia continuando la prattica del Magnifico M. Domenico Veniero, & del Magnifico Molino, & del resto della Accademia: i quali sono tutti quei spiriti pelegrini, & elevati che voi sapete" (I remain here in Venice continuing the activities of the magnificent Messer Domenico Venier, and the magnificent Molino, and the rest of the Academy, all of whom are those rare and lofty spirits whom you know); (Lettere famigliari, fol. 14'). The letter could well have been written earlier than 1551. It is undated, but most other letters in the collection bear dates between the years 1548 and 1550. Parabosco's reference to the "spiriti pelegrini" is ambiguous. For evidence surrounding this mysterious appellation, associated with an academy of Doni's, see Maylender, Storia delle accademie 4:244-48. Maylender voices doubts about whether it ever existed (4:248), as does James Haar, "Notes on the Dialogo della musica of Antonfrancesco Doni," Music & Letters 47 (1966): 202.

intensely literary orientation of Venetian music. Yet the academy has found its way into surprisingly few musical studies of the cinquecento, and then only in passing.[13] The elusive state of evidence about the group's musical activities no doubt accounts for some of this neglect, for nothing of a direct nature survives. Nonetheless, the history of Venier's circle is rich, and an attempt to reconstruct its values and practices yields valuable insight into the processes by which literary ideas were absorbed by makers of music.

The Legacy of Pietro Bembo, Ratified and Recast

Venier and his peers grew up under the spell of Pietro Bembo. Until receiving his cardinalate in 1539 Bembo lived in semiretirement at his villa in Padua, so that only a few privileged literati, including some members of Venier's circle, could have managed much contact with him before he departed for Rome. Venier was only twenty when Aretino named him in a fanciful, irreverent account of a dream about a Bembist Parnassus. As Aretino nears the garden he finds Domenico and his brother Lorenzo among a group of callow youth seated at Bembo's feet. In the idyllic excerpt below Bembo is reading aloud his Istorie veneziane to a rapt and adoring audience.

I take myself to the main garden and as I draw near it I see several youths: Lorenzo Venier and Domenico, Girolamo Lioni, Francesco Badoer and Federigo, who signal me with fingers to their lips to come quietly. Among them was the courteous Francesco Querino. As they do so the breath of lilies, hyacinths, and roses fills my nostrils; then, approaching my friends, I see on a throne of myrtle the divine Bembo. His face was shining with a light such as never before seen; sitting on high with a diadem of glory upon his head, he had about him a crown of sacred spirits. There was Giovio, Trifone, Molza, Nicolò Tiepolo, Girolamo Querino, Alemanno, Tasso, Sperone, Fortunio, Guidiccione, Varchi, Vittore Fausto, Pier Francesco Contarini, Trissino, Capello, Molino, Fracastoro, Bevazzano, Bernardo Navaier, Dolce, Fausto da Longiano, and Maffio.[14]

[13] Such references begin in the mid-nineteenth century with Francesco Caffi, Storia della musica sacra nella già cappella ducale di San Marco dal 1318 al 1797, 2 vols. (Venice, 1854), 1:112-13, 121, and 2:49-50, 129. His suggestions were pursued by Armen Carapetyan, "The Musica Nova of Adriano willaert: With a Reference to the Humanistic Society of 16th-Century Venice" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1945), pp. 74-75, and Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:446, and were taken up by (for example) Francesco Bussi, Umanità e arte di Gerolamo Parabosco: madrigalista, organista, e poligrafo (Piacenza, 1961), pp. 36-37, and Dean T. Mace, "Pietro Bembo and the Literary Origins of the Italian Madrigal," The Musical Quarterly 55 (1969): 73. None of these contains more than a few sentences.

It should be mentioned that Serassi assumed more musical activity and patronage in connection with Venier's salon than evidence collected thus far will support — namely, that "nè capitava in Venezia Musico o Cantatrice di conto, che il Veniero non li volesse udir più d'una volta; e se accadeva ch'essi fossero veramente eccellenti, non solo li premiava secondo il merito loro, ma li celebrava ancora co' suoi bellissimi versi" (Rime di Domenico Veniero, pp. xiv-xv). Serassi's view surely contributed to the assumption prevalent in music histories that Venier's was equally a literary and a musical academy.

[14] "Mi lascio menare a l'uscio del giardin principale, e ne lo appressarmici, veggo alcuni giovani: Lorenzo Veniero e Domenico, Girolamo Lioni, Francesco Badovaro e Federico, che col dito in bocca mi fêr cenno ch'io venga piano: fra i quali era il gentil Francesco Querino. Intanto il fiato dei gigli, de' iacinti e de le rose mi empieno il naso di conforto; onde io, acostandomi agli amici, veggo sopra un trono di mirti il divin Bembo. Splendeva la faccia sua con luce non più veduta; egli sedendo in cima col diadema de la gloria in capo, aveva intorno una corona di spirti sacri. V'era il Iovio, il Trifone, il Molza, Nicolò Tiepolo, Girolamo Querino, l'Alemanno, il Tasso, lo Sperone, il Fortunio, il Guidiccione, il Varchi, Vittor Fausto, il Contarin Pier Francesco, il Trissino, il Capello, il Molino, il Fracastoro, il Bevazzano, il Navaier Bernardo, il Dolce, il Fausto da Longiano, il Maffio" (quoted from Lettere sull'arte 1:97-98). The letter is dated from Venice, 6 December 1537. The figures not fully identified are Paolo Giovio, Triphon Gabriele, Francesco Maria Molza, Luigi Alemanno, Bernardo Tasso, Sperone Speroni, Giovanni Francesco Fortunio, Giovanni Guidiccione, Benedetto Varchi, Giangiorgio Trissino, Bernardo Capello, Girolamo Molino, Girolamo Fracastoro, Marco Bevazzano, Bernardo Navagero, Lodovico Dolce, and Maffio Venier.

Aretino's spoof played on the kind of doting admiration he must have observed in Venice. At midcentury Bembo's beliefs in linguistic purity and the imitation of models and his rhetorical principles for writing prose and poetry still formed the near-exclusive stylistic guides for mainstream vernacular writers, especially in the Venetian literary establishment that Venier came to represent. In Chapter 5, I show how volumes of writings on vernacular style produced by Venetian literary theorists of the generation that succeeded Bembo reproduced and gradually transformed his views. For the moment I wish only to point up some contexts in which Bembo's theories were propounded within the academy and the range of mechanisms by which they were transmitted.

Lodovico Dolce, possibly the most dogged Bembist at midcentury and one of Venier's closest adherents, provides a link between Bembist ideology and Venier's literary practice. Dolce was an indigent polymath who earned a meager livelihood off the Venetian presses. In 1550, three years after Bembo's death, he published his Osservationi della volgar lingua as a kind of zealous reaffirmation of official vernacular ideology. Many of its catchiest passages obediently echo the judgments and jargon of Bembo's Prose della volgar lingua. Dolce reinforces his "Venetocentric" view by naming as the best lyric stylists five comrades, including Domenico Venier and at least three other Venetian poets tied to his circle — Molino, Bernardo Cappello, and Pietro Gradenigo.[15] Other writings, seen in juxtaposition with Dolce's, imply that after Bembo left the Veneto, Venier filled the patriarchal void he left behind.[16] The cosmopolitan Girolamo Muzio cast Venier as a kind of literary padron in his verse treatise Arte poetica. Dedicated to Venier in 1551, it exploited the folk rhetoric of didactic capitoli.

Ricorrerò ai maestri de la lingua, I'll apply myself to the masters of language,

Al buon Trifon Gabriello, al sacro To the good Triphon Gabriele, to the sacred

Bembo. Bembo.

Andrò in Toscana al Varchi, al Tolomei, I'll go to Tuscany to Varchi, to Tolomei,

E correrò a Vinegia al buon Veniero.[17] And I'll race to Venice to the good Venier.

[15] Dolce argues that to write the best Tuscan one need not be Tuscan, as proved by Bembo and others in Venice, "who, writing often in this language, produce fruits worthy of immortality, such as [Bernardo] Capello, Domenico Venier, M. Bernardo Zane, Girolamo Molino, Pietro Gradenigo, and many others" (che in essa lingua, spesso scrivendo, producono frutti degni d'immortalità si come il Capello, M. Domenico Veniero, M. Bernardo Zane, M. Girolamo Molino, M. Piero Gradenigo Gentilhuomini Vinitiani, e molti altri); Osservationi nella volgar lingua (Venice, 1550), fol. 9. Compare the protestations of Girolamo Muzio, Chap. 5, n. 32 below.

[16] The view appears repeatedly in sixteenth-century accounts, as well as in modern ones; see, for instance, Flamini, Storia letteraria, p. 180, who calls Venier "l'erede e successore del Bembo."

[17] Arte poetica, fol. 94.

The political prominence of Venier's noble family and his early education at San Marco with the renowned teacher of humanities, Giovanni Battista Egnazio, made him well suited to the role he came to assume.[18] In their correspondence of 1544, Bembo praised the young Venier for "a lovely, pure, and well-woven style" (un bello, casto, e ben tessuto stile), the same qualities championed in the Prose.[19] Indeed, the strands of their relationship were not only literary but included the larger familial web of Venetian patrician society: the manuscript letters of Pietro Gradenigo, Bembo's son-in-law and Venier's literary cohort, reveal that in the mid-forties Venier actually became godfather to two of Bembo's grandsons.[20]

Venier's most explicit advocacy of Bembist canons came in the commemorative sonnets he composed after Bembo's death in 1547 and published in 1550 in the third volume of the famed series of anthologies known as the Rime diverse, or Rime di diversi.[21] Venier adapted the norms of Bembist style to the purposes of a fervid encomium. By stressing in Bembo the traditional virtues of Venice, he fixed his predecessor's fame in the lasting domain of Venetian civic mythology. An especially typical embodiment of this comes in the sonnet Pianse non ha gran tempo il Bembo,[22] a double tribute to Bembo and another patriarchal contemporary (and close colleague of Bembo's), the Venetian poet-scholar Triphon Gabriele, who died in 1549.[23]

Pianse non ha gran tempo il Bembo, ch'era, Not just as much as the sun circles the Adriatic shore,

Scevra l'alma dal corpo al ciel salito, But as much as it turns from morning to evening,

D'Adria non pur, quanto circonda il lito, [Had Venice] wept not long ago for Bembo, who had risen

Ma quanto gira il Sol da mane a sera. To Heaven, his soul severed from his body. 4

[18] See the reference to Venier's schooling by Lodovico Dolce cited in Rime di Domenico Veniero, p. iv. On Egnazio see James Bruce Ross, "Venetian Schools and Teachers, Fourteenth to Early Sixteenth Century: A Survey and a Study of Giovanni Battista Egnazio," RQ 29 (1976): 521-60.

[19] "Ho tuttavia con grande piacer mio in essa vostra lettera veduto un bello & casto & ben tessuto stile: ilquale m'ha in dubbio recato, quali più lode meritino, o le rime vostre o le prose" (Delle lettere di M. Pietro Bembo . . . di nuovo riveduto et corretto da Francesco Sansovino, 2 vols. [Venice, 1560], 2: libro 10, fol. 131). The letter is dated 31 July 1544, from Rome.

[20] Their father, Pietro Gradenigo, one of the poets singled out for mention by Dolce (see n. 15 above), was a nobleman and husband to Bembo's illegitimate daughter Helena. The information comes from a series of letters in manuscript, "Lettere inedite di Pietro Gradenigo Patrizio Veneto Scritte a diversi," I-Vnm, MSS It. Cl. X, 23 (6526), fols. 9 and 13. A letter on fol. 9 of 15 April (no year but probably from 1544 based on the surrounding letters) speaks of the birth of their son Alvise: "ho elletto per compari Domenico Veniero, e Federigo Badoero miei antichi, et cari amici, et compagni, et Signori devotissi mi di Vostra Signora Reverendissi ma oltre ad alcuni altri gentilhuomini" (I have chosen as godfathers Domenico Venier and Federigo Badoer, my old and dear friends and comrades, and most loyal sirs of your Republic, in addition to some other gentlemen). Elsewhere Pietro writes to his father-in-law: "Marti prossimo passato battezzammo il mio bambino, et li ponenimo nome Paolo. . . . I compari che l'hanno tenuta al battesimo sono stati questi, lo eccellen te ms. Giacomo Bonfio . . ., Monsigno r Franco, il Sign or Girardo Rambaldo, ms. Federigo Badoer, ms. Domenico Veniero, ms. Antoni o Moresini, et ms. Marc' Antonio Contarini. Gentilhuomini tutti di gran valore, et miei cari amici et compagni" (Last Tuesday we baptized my baby boy, and named him Paolo. . . . The godfathers who held him at the baptism were the excellent Messer Giacomo Bonfio . . ., Monsignor Franco, Signor Girardo Rambaldo, Messer Federigo Badoer, Messer Domenico Venier, Messer Antonio Moresini, and Messer Marc' Antonio Contarini, all gentlemen of great worth and my dear friends and comrades); fol. 13.

[21] Libro terzo delle rime di diversi nobilissimi et eccellentissimi autori nuovamente raccolte (Venice, 1550).

[22] Folio 197'.

[23] Gabriele was a principal interlocutor of Daniello's La poetica, on which see Chap. 5 below. In 1512 Bembo sent to him the first two books of his Prose della volgar lingua in manuscript; see Mario Marti's preface to his edition Opere in volgare (Florence, 1961), pp. 265-68, and for a reprint of the letter Bembo wrote accompanying the manuscript, pp. 713-15. A manuscript in I-Vmc entitled "Accademie in Venezia" (MS Gradenigo 181) lists Gabriele's circle in Padua under "Adunanze virtuose" (fol. 148'). A few remarks on Gabriele's circle may be found in Paul Lawrence Rose, "The Accademia Venetiana: Science and Culture in Renaissance Venice," Studi veneziani 11 (1969): 200.

Piange te parimente, hor ch'a la vera Now that to the true Fatherland, dying,

Patria morendo e tu TRIFON se gito, You too have gone, Triphon, all of Venice

Venezia tutta, e quanto abbraccia il sito Weeps for you equally, as much as it yet embraces

Qua giuso ancor della mondana sfera. The site of the worldly sphere here below.[24] 8

D'egual senno ambo duo, d'egual bontate Of equal wisdom both, of equal goodness

Foste, a communi studi ambo duo volti, Were you, both turned to common studies

D'una patria, d'un sangue, e d'una etate; From one homeland, one blood, and one age. 11

Nodo par d'amistade insieme avolti An equal knot of friendship wound round both

Tenne sempre i cor vostri alme ben nate, Always held your hearts, well-born souls;

Ed hor ancho v'ha 'l cielo ambo raccolti. And now even Heaven has gathered you both. 14

Here Venier placed the memory of his two mentors in the discourse of Venetian myth by stressing in them qualities attached to traditional conceptions of the state — goodness and wisdom — as well as their derivation from a common race. Though Venier distinguishes between Heaven, the "vera patria," and Venice, the "mondana sfera," his affections seem to lie chiefly with the latter. From the opening image of the sun circling the Adriatic shore (the "lito") he links in a linguistically rich evocation both Venetian geography and the notion of the homeland to the patriotic rhetoric of the Serenissima.[25] The poem's emphasis on the moral content of Venetian mythology ("d'egual bontade") demonstrates that Venier's depiction of Bembo and Gabriele as model figures was not meant to be just literary and scholarly but ethical as well, charged with a moral imperative.

In other poems on Bembo's death Venier made clear the nature of this imperative, as seen in a sonnet that asks Dolce too to mourn Bembo.

DOLCE, possente a raddolcir il pianto, Dolce, powerful enough to sweeten the mourning

Ch'èper alta cagion pur troppo amaro, That from a great cause is all too bitter,

Piangendo il Bembo à tutto 'l mondo caro, Weeping for Bembo, dear to the whole world,

Poi che sua morte ha tutto 'l mondo pianto, Now that the whole world has wept for his death: 4

Perche seco habbia il duol di gioia alquanto, Since grief contains some joy,

Anzi vada il gioir col duolo a paro, Or rather joy goes paired with grief,

Segui 'l tuo stile, e non ti sia dischiaro Follow your style, and let it not displease you

Di lagrimarlo in sì soave canto. To lament him in such a sweet song. 8

[24] For vv. 1-2 Nino Pirrotta kindly offers the alternative "Not just what is surrounded by the Adriatic shore [i.e., Venice], but all the land circled by the sun from morning to evening" as clarification of the distinction Venier later draws between Venice and the "worldly sphere" (private communication).

[25] Bembo used a related lexicon and imagery in his own sonnet, "Questo del nostro lito antica sponda, / Che te, Venezia, copre e difende" (Opere in volgare, ed. Marti, no. 93, pp. 300-301).

Questo farà, che 'l suon de tuoi lamenti This will make the people hear ever more

Gioia non men che duolo altrui recando Eagerly the sound of your laments,

Sempre piu disiose udran le genti. Bearing joy to others no less than grief: 11

Tal che ferendo in un I'alme e sanando, So that at once wounding and healing the souls,

Fama eterna il tuo stil ne l'altrui menti, Your style, like Achilles' lance,

Come l'hosta d'Achille, andrà lasciando.[26] Will leave eternal fame in people's minds. 14

Throughout the poem Venier pursued the Petrarchan opposition of gioir and duolo to develop the poem's thematic strategy, while punning his recipient's name: to make his sadness felt most keenly Dolce should lament Bembo's death in sweet tones. His conceit tempers the sense of both terms, joy and grief, with distinctly Petrarchan reserve, each straining to uphold and assert its meaning in the face of its antonym.

At its surface, then, the injunction for Petrarchan paradox is simply a thematic one. But its stylistic basis finds an explanation in Ciceronian codifications of vernacular style that prevent words from registering too firmly on a single semantic or stylistic plane. By reducing the expression of sorrow through its opposite and exhorting Dolce to a sweet style even for the dark subject of death, Venier thus also claimed for his contemporaries the same canon of moderation earlier urged by Bembo. The road he treads is dutifully narrowed by Bembist precepts. And his insistence in the sestet that a lament is best heard mixed with contrasting sentiments invokes Bembo's advocation of Ciceronian variation and restraining decorum as the vehicles of rhetorical persuasion.

Such reserved expression also recalls the Venetian patriciate's artfully orchestrated self-image and its tendency to insist on well-monitored emotions in the civic sphere. Decorum, in this sense of reserve, formed the literary counterpart of virtù, purity, wisdom, and good judgment. As we have seen, these qualities, basic to Venetian communal identity, were epitomized for Venetians by Petrarch's lyric style. The academic and self-conscious brand of Petrarchism that proliferated in Venier's milieu, in catering to the needs of a highly disciplined state, thus served to reinforce the self-identity that was so emphatically articulated in the political and social rhetoric of the republic.

Yet, paradoxically, the ideological force that suppressed the poet's voice joined blithely with a candid quest for individual public acclaim. And so, ironically, Venier sugars the end of his sonnet with assurances that "Fama eterna il tuo stil ne l'altrui menti . . . andrà lasciando." The Bembist path to literary perfection might be unyieldingly self-effacing, but the promised compensation for taking it was poetic immortality.

[26] Libro terzo delle rime di diversi, fol. 211, in the Newberry Library copy [recte: fol. 195].

Venier was well accustomed to the position of civic literary advisor he assumed in these sonnets. Although he wielded as much power as any vernacular author in Venice, he seems to have eschewed print by and large, publishing little and participating mainly in a manuscript culture that circulated verse by hand, post, perhaps even word of mouth.[27] Publicly he served primarily as a mentor to the many fledglings of the bourgeoisie, aristocratic dropouts, and patrician dilettantes who flocked to his door. Despite the power and esteem he accumulated, Venier resembled other noble literati in producing no canzoniere or other literary opus while he lived. His role instead was that of arbiter of Venetian poetic tastes. Like the printed anthologies to which he sometimes added his prestigious name, his salon and his acquaintance were stepping stones to public status for numerous literary aspirants of backgrounds less privileged than his, striving for acknowledgment or remuneration and a firm place within the active literary discourse of the day.[28] In this capacity Venier appeared as dedicatee of a number of volumes issued from the prolific Venetian presses, and much of the poetry that he and his comrades produced responded indirectly to the new public nature of words.[29] Generated out of the larger fabric of Venetian society, this poetry often transformed the contemplative, soloistic poetics of Petrarchan-Bembist lyric models into the more externalized and explicitly dialogic forms that I identified in Chapter 3 — sonnet exchanges, dedica-

[27] On this phenomenon see Armando Balduino, "Petrarchismo veneto e tradizione manoscritta," in Petrarca, Venezia e il Veneto, ed. Giorgio Padoan, Civiltà veneziana, Saggi 21 (Florence, 1976), pp. 243-70.

[28] Venier's sporadic contributions to the printed literature may be compared with those of several other Venetian poets, highly placed in the social and literary worlds, whose writings circulated in manuscript. Molino, also of noble birth, must have been known primarily in manuscript, since his Rime were printed only posthumously. The same is true of Giacomo Zane, who died in 1560 and whose Rime were issued in 1562; see Taddeo, Il manierismo letterario, p. 101 n. 1. I am inclined to think that there was a tendency among the uppermost crust to emulate aristocratic Florentine manuscript culture (in addition to the Tuscan language) by avoiding a wholesale participation in the culture of printed words as being beneath their station. Poets, including Molino, Celio Magno, Giuliano Goselini, and others, frequently entered into the world of print via musical sources, and only later poetic ones; see Lorenzo Bianconi and Antonio Vassalli, "Circolazione letteraria e circolazione musicale del madrigale: il caso G.B. Strozzi," in Il madrigale tra cinque e seicento, ed. Paolo Fabbri (Bologna, 1988), pp. 125-26.

[29] Among volumes dedicated to Venier are the Lettere volgari di diversi nobilissimi huomini, et eccellentissimi ingegni scritte in diverse materie (Venice, 1542), with a dedication by the publisher and editor Paolo Manutio; an edition of Ficino's Tre vite entitled Marsilio Ficino florentino filosofo eccellentissimo de le tre vite (Venice, 1548), translated into the vernacular by Giovanni Tarcagnota (pseudonymously called Lucio Fauno in a preface to the readers) and dedicated by the publisher Michele Tramezzino; the Rime diverse del Mutio Iustino Politano (Girolamo Muzio), including the Arte Poetica (Venice, 1551), dedicated by the author; and the Rime di Mons. Girolamo Fenaruolo (Venice, 1574), dedicated by Fenaruolo's posthumous biographer Marc'Antonio Silvio. Venier also figured among the inflated number of dedicatees (loosely so-called) scattered throughout Antonfrancesco Doni's Libraria (Venice, 1550), fol. 16'; on the various editions of the work, two of which date from 1550, see C. Ricottini Marsili-Libelli, Anton Francesco Doni, scrittore e stampatore (Florence, 1960), nos. 21, 22, and 70. In addition, many of the poems in the Libro terzo delle rime di diversi stem from the Venier circle and include a great many encomiastic praises of both Bembo and Venier — for example, Dolce's Venier, che dal mortal terreno chiostro, fol. 184, Giorgio Gradenico's (Gradenigo) Venier, che l'alma a le crudel percosse, fol. 98', and Pietro Aretino's VENIERO gratia di quel certo ingegno, fol. 183'. The Libro terzo was the first of the Rime di diversi series to represent large numbers of poets connected with Venier, including Dolce, Giovanni Battista Susio, Giovanni Battista Amalteo, Parabosco, Giorgio Gradenigo, Fortunio Spira, Bernardo Tasso, Giacomo Zane, Bernardo Cappello, Anton Giacomo Corso, and Venier himself (although a number had already been included in the Rime di diversi nobili huomini et eccellenti poeti nella lingua thoscana. Libro secondo [Venice, 1547] — Corso, Cappello, Susio, Parabosco, and Dolce).

tory poems, stanzas in praise of women, patriotic encomia, and so forth. It thus became fundamentally a poetics of correspondence and exchange, but also of competition, which often took the form of ingenious and ultrarefined verbal games.

One of the works that best reveals the evolving direction of Venier's academy at midcentury is Parabosco's I diporti. First printed (without date) by 1550, I diporti is a colorful, Boccaccesque series of novellas in the form of conversations between various men of letters.[30] The interlocutors are mostly linked with Venier's group: Parabosco himself, Molino, Venier, Badoer, Speroni, Aretino, the scholar Daniele Barbaro, Benedetto Corner (Venier's interlocutor in a dialect canzoniere discussed below), the editor and poet Ercole Bentivoglio, Count Alessandro Lambertino (recipient of Parabosco's capitolo cited earlier), the philosopher and classicist Lorenzo Contarini, and the poets Giambattista Susio, Fortunio Spira, and Anton Giacomo Corso, among others.[31]

During a lengthy digression toward the end of the stories the participants enumerate the requisite qualities of different lyric genres — madrigal, strambotto, capitolo, sestina, pastoral canzone, and sonnet.[32] Madrigals must be "sharp with a well-seasoned, charming invention" (acuti e d'invenzione salsa e leggiadra) and must derive their grace from a lively spirit.[33] They must be beautifully woven, adorned with graceful verses and words and, like the strambotto, have a lovely wit (arguzia) and inventiveness. To exemplify these qualities Sperone recites one of Parabosco's madrigals, applauding its manipulation of a pretty life-death conceit. Corso then recites a witty capitolo (again Parabosco's), full of anaphora, prompting Badoer to effuse on its "begli effetti amorosi."[34] The sestina, Contarini insists, allows the exposition of beautiful things and is a very lovely poem (poema molto vago).[35]

[30] I cite from the mod. ed. in Novellieri minori del cinquecento: G. Parabosco — S. Erizzo, ed. Giuseppe Gigli and Fausto Nicolini (Bari, 1912), pp. 1-199, hereafter I diporti. On the date of the first edition see Bussi, Umanità e arte, p. 77 n. 1. As Giuseppe Bianchini reported, Parabosco mentioned the existence of I diporti in a letter (also undated), which in turn probably stems from 1550; Girolamo Parabosco: scrittore e organista del secolo XVI, Miscellanea di Storia Veneta, ser. 2, vol. 6 (Venice, 1899), p. 394. On this basis Bianchini suggested 1550 as the date of the first edition. Ad[olphe] van Bever and Ed[mond] Sansot-Orland, Oeuvres galantes des conteurs italiens, 2d ser., 4th ed. (Paris, 1907), pushed the compositional date to a slightly earlier time (pp. 219-20), but without real evidence. The hope Doni expressed in the Libraria (Venice, 1550) that Parabosco would soon issue "un volume di novelle" (p. 23) would seem to secure the date of 1550, since Doni's book was published in that year.

[31] The mix of Venetians and non-Venetians overlaps a good deal with other descriptions of Venier's circle, like the one in Parabosco's capitolo cited in n. 11 above. Characteristically, a number of figures (as Parabosco states in the ragionamento to the Prima giornata) are non-Venetians but all spent time in Venice: Bentivoglio and Lambertino from Bologna, Susio from Mirandola, Spira from Viterbo, Corso from Ancona, and Speroni from Padua (I diporti, p. 10). Speroni was also a main interlocutor in Bernardino Tomitano's Ragionamenti della lingua toscana (see Chap. 5, pp. 129-30 below). The towering Aretino, quite fascinatingly, though counted by Parabosco among the non-Venetians, is the only one given no native origin. For further identifications of these and other interlocutors in I diporti see Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco, pp. 395-98. On Baldassare Donato's encomiastic setting of a sonnet on Contarini's death see Chap. 9 n. 76.

In the decade after I diporti M. Valerio Marcellino published a series of conversations called Il diamerone that were explicitly set among the Venier circle (Venice, 1564); see Chap. 5 below, n. 139.

[32] I diporti, pp. 177-91.

[33] Ibid., p. 177.

[34] Ibid., pp. 179-80.

[35] Ibid., pp. 182-83.

In each genre, then, grace and beauty are paramount. But no less important in their estimation are invention, wit, and technical virtuosity. When they come to the labyrinthine sestina, this stance takes the form of a little apologia, as Corso and Contarini argue that the genre is no less suited than the canzone to expressions of beauty and no more difficult to compose.[36] After more madrigals of Parabosco are recited — and amply praised by as harsh a judge as Aretino — the whole company assembles to assess the formidable sonnet.

Toward the end of their exchange they cite several sonnets of Venier, whose virtuosic verbal artifice won him widespread fame in the sixteenth century. Whereas the madrigals described earlier aimed at a tightly knit and clever rhetorical formulation, these sonnets employ technical artifice in a somewhat different role. To construct the following, for example, Venier systematically reworked corresponding triads of words — no fewer than four of them in the first quatrain alone.

Non punse, arse o legò, stral, fiamma, o laccio The arrow, flame, or snare of Love never

D'Amor lasso piu saldo, e freddo, e sciolto Stung, burned, or bound, alas, a heart more

Cor, mai del mio ferito, acceso, Steady, cold, and loosed than mine, wounded, kindled,

e 'nvolto, and tied

Gia tanti dì ne l'amoroso impaccio. Already so many days in an amorous tangle. 4

Perc'haver me 'l sentia di marmo e ghiaccio, Because I felt marble and ice within me,

Libero in tutto i' non temeva stolto Free in everything, I foolishly did not fear

Piaga, incendio, o ritegno, e pur m'ha colto Wound, fire, or restraint, and yet

L'arco, il foco, e la rete, in ch'io The bow, the fire, and the net in which I lie have

mi giaccio. caught me. 8

E trafitto, infiammato, avinto in modo And pierced, and inflamed, and captured in such a way

Son, ch'altro cor non apre, avampa, o cinge Am I that no dart, torch, or chain opens, blazes, or clasps

Dardo, face, o catena hoggi più forte. Any other heart today more strongly. 11

Ne fia credo chi 'l colpo, il caldo, Nor, I believe, may it be that the blow, and the heat, and

e 'l nodo, the knot

Che 'l cor mi passa, mi consuma, e stringe, That enter, break, and squeeze my heart

Sani, spenga, o disciolga altri, che Could be healed, extinguished, or unloosed by any other

morte.[37] but death. 14

Parabosco's interlocutors submit a panegyric on Venier after the mention of this puzzlelike poem and its sister sonnet, Qual più saldo, gelato e sciolto core. Both poems were well enough known to the interlocutors to forego reading them aloud. Non

[36] Ibid., p. 182.

[37] In addition to its mention in I diporti, p. 190, and its inclusion in the Libro terzo delle rime di diversi, fol. 198, the sonnet appeared in numerous subsequent printed anthologies and a large number of manuscripts. For a partial listing of these see Balduino, "Petrarchismo veneto e tradizione manoscritta," pp. 258-59. I give an early version of the sonnet as it appeared in the Libro terzo delle rime di diversi, to which I have added some modern diacritics.

punse, arse o legò, Spira avows, is one of the "rarissimi e bellissimi fra i sonetti maravigliosi di Venier."

Non punse, arse o legò initiated a subtle shift in the stylistic premises that Venier's circle had maintained for years. Its formal type, dubbed by the modern critics Dámaso Alonso and Carlos Bousoño the "correlative sonnet,"[38] seems to have been Venier's invention, created by extending to their utmost Petrarchan tendencies toward wit and ingegno that appear in earlier cinquecento poetry in far less extreme guises. The essential strategy of the correlative sonnet lies in its initial presentation of several disparate elements ("punse" / "arse" / "legò") that are continually linked in subsequent verses with corresponding noun, verb, or adjective groups ("stral" / "fiamma" / "laccio"; "saldo" / "freddo" / "sciolto," and so forth). Although the high-level syntactic structure is highly syntagmatic, the immediate syntax of the poetic line tends to lack coordination and subordination of elements except that of a crisscrossed, paratactic sort.

Very possibly Non punse, arse o legò and Qual più saldo had even been written some time before 1550, as Spira seems to imply in describing them as the models imitated by another sonnet and the source of Venier's wide renown as a "raro e nobile spirto."[39] They thus represent an early and radical extension of the Petrarchan penchant for witty wordplay, one that was carried out in less systematized forms in Petrarch's own sonnets and imitated in less extreme ways by others in the sixteenth century — Luigi Tansillo, Annibale Caro, Benedetto Varchi, and Gaspara Stampa.[40]

[38] For their analysis of this sonnet see Alonso and Bousoño, Seis calas, p. 56. See also Taddeo, Il manierismo letterario, pp. 57-58, and Erspamer, "Petrarchismo e manierismo," pp. 190-91, who names the basic rhetorical figure with the Latin rapportatio. The sixteenth-century Daniello characterized the phenomenon as "corrispondenze e contraposizioni" in his discussion of Petrarch's sonnet no. 133, Amor m'ha posto come segno al strale; La poetica (Venice, 1536), p. 79 (see n. 40 below and Chap. 5 below on Daniello). For an analysis of the sonnet's correlations see Dámaso Alonso, "La poesia del Petrarca e il petrarchismo (mondo estetico della pluralità)," Studi petrarcheschi 7 (1961): 100-4.

[39] I diporti, p. 190. The two sonnets appear on the same page in the Libro terzo delle rime di diversi. One candidate for the imitations Spira refers to is Parabosco's sonnet Sì dolce è la cagion d'ogni mio amaro; its first tercet reads: "Non fia però ch'io non ringratia ogn'hora / La fiamma, il dardo, la cathena, e Amore / Che si m'arde per voi, stringe, & impiaga" (Parabosco, Il primo libro delle lettere famigliari, fol. 50).

[40] Consider, for example, the more leisurely correlations in Petrarch's sonnet no. 133, "Amor, m'ha posto come segno al strale, / Come al sol neve, come cera al foco, / Et come nebbia al vento," in which two and a half lines (vv. 1-3) are needed to correlate four pairs of elements a single time. The second quatrain brings back their substantive forms ("colpo," "sole," "foco," "vento") just once, and the first tercet correlates only the first three pairs of elements ("saette," "sole," "foco" / "mi punge," "m'abbaglia," "mi distrugge"). The last tercet concludes the whole by turning its final rhetorical point around a reorientation of the last element: the "dolce spirto" of the beloved that becomes the breeze ("l'aura") before which the poet's life flees. Petrarch's four-pronged correlations thus number a total of four for the whole sonnet, as compared with twelve for Venier's three-pronged correlations in Non punse, arse o legò.

For an example in Bembo, see sonnet no. 85, Amor, mia voglia e 'l vostro altero sguardo (Opere in volgare, ed. Marti, p. 497), which structurally resembles Petrarch's Amor, Fortuna e la mia mente (no. 124). Alonso and Bousoño, Seis calas, pp. 85-106, discuss two-, three-, and four-pronged correlations in sonnets by Petrarch, Ariosto, Luigi Tansillo, Vincenzo Martelli, Benedetto Varchi, Gaspara Stampa, Camillo Besalio, Pietro Gradenigo, Annibale Caro, Maffio Venier, Luigi Groto, and Giambattista Marino. A good example, though not as rigorously organized as this one, exists in Stampa's no. 26, which may be significant in view of her association with Venier; see Fiora A. Bassanese, Gaspara Stampa (Boston, 1982), pp. 9-12, 18, 37-38, and nn. 66-75 below. The first quatrain of the poem reads: "Arsi, piansi, cantai; piango, ardo, canto; / Piangerò, arderò, canterò sempre / Fin che Morte o Fortuna o tempo stempre / A l'ingegno, occhi e cor, stil, foco o pianto" (Rime, ed. Maria Bellonci and Rodolfo Ceriello, 2d ed. [Milan, 1976], p. 97). Like Petrarch, Stampa reorders the triad in its different reincarnations.

Though the correlative sonnet represents only one subgenre in the poetry of Venier, it nonetheless presents a vivid example of the growing tendency in the Venetian lyric to invest the sanctioned Ciceronian properties of grace and moderation with greater technical complexity.[41]

Polyphony and Poetry, High and Low

The infatuation with ingegno that inspired Venier's correlative sonnets must have found congenial exemplars in the madrigalian practice recently ascendent in Venice. Both correlative sonnets and polyphonic madrigals depended on an audience immediately at hand, ready to be engaged and impressed and to reflect on its currency in the world of vernacular arts. And both were rooted in a kind of intellectual luxuria that was necessary to champion what might otherwise have seemed intolerably arcane creations.

The reshaping of Venetian madrigals in knotty church polyphony parallels the academic, self-conscious impulse toward intellectual sophistication that lay beneath Bembo's thinking about vernacular style and that reached extremes in correlative verse. Such impulses were the very sort encouraged by the competitive lather of Venetian academic life and the commercialization of art with which it intersected. Yet they contradict the prevailing norms of decorum that control both Venetian sonnets and sonnet settings to produce a basic tension in Venice's high vernacular arts: like Venier's most intricate poems, the madrigals produced by Willaert and his circle seem to want to emerge unruffled from the competitive fray as both the most urbane and the gravest emblems of aristocratic culture — to win eminence in the domain of virtuosity without jeopardizing the aristocratic values to which they are beholden.

Ultimately the extremes of complexity in both Willaertian madrigals and Venier-styled verse threatened to upset the Bembist balance between calculated artifice and natural grace. Both labor in a ponderous rhetoric whose guiding hand is an over-riding consciousness of noble gravitas, without embracing the elegance — the sprezzatura — that was de rigueur in Florentine music and letters or in those of courts like

[41] Other famous examples of Venier's correlative verse include M'arde, impiaga, ritien, squarcia, urta, e preme (Rime di diversi . . . Libro quinto [Venice, 1552], p. 299) and Maladetto sia 'l dardo, il foco, e 'l laccio (ibid., p. 300).

The source tradition may indicate that Venier revised such sonnets with a view to perfecting technical aspects of them. In the radically revised version of Non punse, arse o legò that was issued in vol. 5 of the Rime di diversi, p. 297, for example, he changed vv. 5 and 6 from: "Perc'haver me 'l sentia di marmo, e ghiaccio / Libero in tutto i non temeva stolto" to: "Saldo et gelato più, che marmo, et ghiaccio, / Libero & franco i non temevo stolto," adding an extra two sets of correlations and allowing every verse in the sonnet to participate in the correlative pattern. Multiple variant readings from various manuscripts are given in Balduino, "Petrarchismo veneto" (p. 259), who also lists sixteenth-century prints that include this sonnet (p. 258 n. 26). Balduino cites other sorts of revisions that show Venier's increasing concern for technical perfection, for example the two versions of the sonnet Mentre de le sue chiome in giro sparse (pp. 254-58). Venier apparently rewrote the initial quatrain in a later version, changing the first verse, from "in giro sparse" to "a l'aura sparse" and thus introducing a pun and play of sounds between the ends of vv. 1 and 4 ("Vedea sotto il bel cerchio aurato starse") — that is, "a l'aura sparse" / "aurato starse."

Mantua and Ferrara. On the contrary, the new Venetian products were strangely mannered by comparison with those produced elsewhere in northern Italy and in ways perhaps unimaginable without Venice's combative pressure to adapt afresh new techniques and styles. Beneath its virtuosic displays Venice managed to maintain as a Procrustean bed ideals of the ordene antiquo that were deeply rooted in Venetian consciousness.

Although no direct reports tell of Venetian madrigals performed in the Venier household (or in most others, for that matter), fictive re-creations like Doni's make it clear that madrigals found their main abode in drawing rooms. Clearly the primary occupation of the Venier house was vernacular literature, with musical performances playing a decidedly secondary role. Yet much evidence suggests that music nonetheless occupied a regular niche in the academy's agenda. Several central figures linked with Venier's household sustained strong connections with the culture of written polyphony: in addition to Parabosco the literati Girolamo Fenaruolo and Girolamo Molino, to whom I will turn shortly. Two other star pupils of Willaert's were known to its members: Perissone Cambio and Baldassare Donato. Perissone formed the subject of a double sonnet exchange between Venier and Fenaruolo following his death, probably in the early 1560s.[42] And the promising Donato was given the task no later than 1550 of setting three of Venier's stanzas for large civic celebrations — this at a time when Venier's academy was still in its youthful stage and Donato himself no more than about twenty.[43] Even Willaert appears in what may be suggestive proximity to Venier, namely the postscript to Parabosco's capitolo characterizing Venier's salon to Lambertino of 1555.[44] Perhaps Willaert — aging, heavily burdened, and slowed by ill health — would not have spent much time there late in life, but there is no doubt that he kept in touch with many of its intimates.

Serious polyphonic madrigals stand at the forefront of developments in Venetian secular music. But like Venier's correlative sonnets for Venetian literati and vernac-

[42] See Chap. 9 nn. 65-66 below, and for the sonnets the Appendix to Chap. 9.

[43] See Giulio Maria Ongaro, "The Chapel of St. Mark's at the Time of Adrian Willaert (1527-1562): A Documentary Study" (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986), p. 125.

Yet another polyphonist, Gasparo Fiorino of Rossano, was directly acquainted with Venier, although probably in a later decade. Fiorino flourished from about 1571-74 in Ferrara and apparently had social connections with Rome as well (see Iain Fenlon, "Fiorino, Gasparo," in The New Grove 6:601-2). Fiorino was recipient of a dedicatory sonnet by Venier, which was attached to his Libro secondo canzonelle a tre e a quatro voci, fol. [2], a collection "in lode et gloria d'alcune signore et gentildonne genovesi," published in 1574. Fenlon speculated that Fiorino had been a singer at St. Mark's in the middle of the century. Although the documentary work of Ongaro, "The Chapel of St. Mark's," now makes this very doubtful, the sonnet addressed to him by Venier does confirm that he was a singer (Rime di Domenico Venier, no. 98).

[44] Parabosco, La seconda parte delle rime, fol. 63'-64. Earlier scholars treated the juxtaposition of their names as evidence that Willaert frequented Venier's house, even though the poem makes no such explicit claim; see Gaetano Cesari, "Le origini del madrigale cinquecentesco," Rivista musicale italiana 19 (1912): 395-96, and Carapetyan, "The Musica Nova of Adriano Willaert," p. 74.

ular poetry more broadly, they represented only one of several genres available to musicians. Bembo's call for discrete stylistic levels echoed as profoundly in vernacular music as it did in literature. And while Venetian composers now generally reserved their most serious secular efforts for madrigal books, the same composers also began, in 1544, to publish in separate volumes stylized genres of light music — canzoni villanesche alla napolitana and villotte.[45] Many of the dialect songs were obscene and invariably had something comic, rustic, or earthy about them. The canzoni villanesche that emanated from Venice reworked Neapolitan polyphonists' three-voice settings of popular Neapolitan songs by expanding the models from three voices to four and shifting the original popular tune from its prominent place in the soprano to a more hidden location in the tenor. They often Tuscanized the poems' dialect and reduced the number of stanzas. These transformations made the whole genre into something less soloistic and more madrigalistic — that is, more a matter of shared choral singing according to the elevated northern ideal of equal-voiced polyphony. They also invested the settings with self-conscious artifice — lowly tunes uplifted by northern wit, as it were — in ways that could appeal to Venetian intellects. Many prints of Venetian canzoni villanesche met with immense success — numerous reprints and many arrangements for solo lute.

Dialect songs likely formed part of the academy's fare, just as madrigals did. One collection of villotte was produced in 1550 by Willaert's close Netherlandish friend Antonio Barges and dedicated by Barges to Venier's cohort Fenaruolo.[46]

To the Magnificent and Reverend Monsignor Mr. Girolamo Fenaruolo, my lord:

Being the custom of almost everyone who wants to print some little thing of his to erect a defense against a certain sort of person who, either out of a bad nature or not to appear ignorant, censures the efforts of everyone, good and bad alike, I too on that account would have to address these flowers of mine (rather than fruits) to someone who by his profession had toiled and acquired more in music than in any other science. But all the same I will not do so. For in this case it's enough for me that I've forced myself as much as I could not to deviate from the teaching of the only inventor of true and good music, the most excellent Adrian, who was not only my most diligent teacher but the very best father to me. I therefore dedicate these little efforts of mine to you — you who are a friend and who, besides belles lettres and

[45] The primary work on lighter genres is that of Donna G. Cardamone, The "Canzone villanesca alla napolitana" and Related Forms, 1537-1570, 2 vols. (Ann Arbor, 1981), esp. Chaps. 5 and 6. On pp. 164ff. Cardamone discusses misgivings of northerners about the moral influence of part-songs in dialect, but their Counter-Reformational statements seem to have appeared only after the mid-fifties. Willaert first published a collection of napolitane (as they were sometimes called) with the printer Girolamo Scotto in 1544, but only a single gathering of the tenor part book survives (see Cardamone 2:35-36). In 1545 Antonio Gardane brought out a version of the same book, Canzone villanesche alla napolitana di M. Adriano Wigliaret a quatro voci . . . novamente stampate (RISM 154520), and one by Perissone, Canzone villanesche alla napolitana a quatro voci di Perissone novamente poste in luce. . . . Donato published a book of napolitane in 1550 (cited in n. 78 below).

[46] Full title: Di Antonino Barges maestro di cappella alla Casa grande di Venetia il primo libro de villotte a quatro voci con un'altra canzon della galina novamente composte & date in luce (Venice, 1550). Barges was maestro at the Casa Grande until 1563. He witnessed Willaert's will of 8 December 1562 shortly before the latter's death; see Vander Straeten, La Musique aux Pays-Bas 6:246.

gracious habits, are so adorned with that sweet virtue, and who gladly hear my works. Not that they were made with the goal that they might be printed, but rather composed at various times at the wishes of my different friends (although now perforce being sent out, so as to appear a grateful friend with little praise rather than an ungrateful musician with much). I also send you a few sweet compositions by the Magnificent Cavalier S. Andrea Patricio da Cherso, which I believe you'll like a lot. This, my sir, is how much I now give you evidence of the love I bear to you, and I do so ardently, being certain that you know clearly (and much better than many others) how true that thought is; for he who does what he can do does therefore what he ought. Not that anyone should therefore blame me for not sending them to the very worthy and gentle M. Stefano Taberio, since in sending them to you not only do I make a richer gift to M. Stefano, who loves you so much, but also to the gentle M. Marco Silvio, both of whom, living in you as you live in them, love and honor the one who loves and honors. I kiss your hand, my lord, and I wish for that dignity that your good qualities merit, begging you to be kind enough to sing these little canzonette of mine now and then with your Silvio and with those gentlemen, among the pleasantries and delights of the most merry Conegliano; and love me since I love and honor you. Antonino Barges.[47]

Barges's villotte — some of which are really villanesche alla napolitana, others Venetian dialect arrangements — were among the more northern, complex examples of light music. They justify his claim to be following closely his "ottimo patre," Willaert, and his linking of villotte with the seemingly high literary circle of Fenaruolo.

Barges pointedly avoided praising Fenaruolo's own musical skills, emphasizing instead his devotion to musicians and citing the genesis of the print's villotte among amateur appreciators like Fenaruolo and friends. Clearly he did expect that they could render their own performances of the songs, for he asked Fenaruolo to sing them "now and then" together with his other literary cohorts. Barges's expectation

[47] "Al Magnifico & Reverendo Monsignore M. Girolamo Fenarolo Signor suo. Essendo costume quasi d'ogn'uno che voglia mandare alcuna sua fatica in luce, proccaciarsi diffesa contra una certa sorte di persone, che o per lor trista natura, o per mostrar di non esser ignoranti biasimano cosi le buone come le triste fatiche d'ogn'uno. anch'io percio doverei indrizzar questi miei piu tosto fiori che frutti, ad alcuno che per sua professione piu havesse sudato & aquistato nella musica che in altra scientia. ma non lo farò altrimenti, perche in questo mi basta ch'io mi son forzato per quanto ho potuto, di non deviare dalla dissiplina de l'unico inventore della vera & buona musica l'Eccellentissimo Adriano il quale non solamente m'é stato diligente maestro, ma ottimo patre, Io dunque â voi che oltre le bellissime litere, & i gratiosi costumi, sete ancho ornato di questa dolcissima virtu mi sete amico, & udite voluntieri le mie compositioni dedico queste mie picciole fatiche, non gia fatte a fine ch'andassero alle stampe, ma in diverse volte a voglia de diversi amici miei composte quatunque adesso, (piu tosto per parer grato amico con poca lode, che ingrato musico con molta) sia forzato mandarle fuori. Mandovi ancora alcune poche ma soavi compositioni del Magnifico Cavalliero il S. Andrea Patricio da Cherso, le quali credo che molto vi piaceranno. Questo é signor mio quanto hora vi posso dare in testimonio dell'amore ch'io vi porto, & lo faccio arditamente essendo certo che voi (& assai meglio di molt'altri) conoscete chiaramente quanto sia vera quella sententia, che quello che fa quanto puote, conseguentemente fa quanto deve. Ne sia percio alcuno che mi biasimi, non le mandando al molto meritevole & molto gentile M. Stefano Taberio, percio che mandandole a V.S. non solamente ne faccio piu ricco dono a M. Stefano che tanto v'ama, ma insieme al gentilissimo M. Marco silvio, i quali vivendo in voi, si come voi in loro vivete, amano, & honorano, chi v'ama, & honora. Vi bascio la mano signor mio, & vi desidero quella dignita che meritano tante vostre buone qualita, pregandovi che mi siate tal'hor cortese di cantar queste mie canzonette con il vostro silvio, & con quei gentil'huomini, tra le amenita & le delitie del giocondissimo Conegliano: & amatemi per ch'io v'amo & honoro. Antonino Barges."

that his recipient would sing the pieces recalls those of Perissone and Parabosco in dedicating prints to Gottardo Occagna (see Chap. 3, pp. 53-60). Like Perissone, Barges claims not to have composed these works for print but for the pleasure of literary friends — Silvio, Stefano Taberio, and Fenaruolo. In any case, they were not so hard to negotiate as Perissone's five-voice madrigals, which required a firmer grasp of singing written counterpoint from part books.

Fenaruolo knew other musicians too, including Willaert, to whom he addressed a satiric capitolo in 1556, and Perissone, whose death he mourned with Venier, the dedicatee of Fenaruolo's posthumous canzoniere.[48] Venier's academy seems a likely setting for the sort of light music dedicated to Fenaruolo, since it was one of his main venues. Napolitane may even have been heard there in equal measure with serious madrigals, as was true at the Accademia Filarmonica of Verona from the time of its founding in 1543.[49]

With their earthy tones and often obscene Neapolitan or Venetian texts, these songs correspond musically to bawdy dialect verse composed by Venier himself and others in his circle, verse that formed the subject of a letter from Aretino to Venier in November 1549.

Just as the coarseness of rustic food often incites the appetite to gluttony, Signor Domenico — more than the great delicacy of high-class dishes ever moved to the pleasure of eating in such a way — so too at times the trivial aspects of subjects in the end sharpen the intellect with a certain eager readiness, which as fate would have it never showed itself with any epic material. So that in composing in the Venetian language, style, and manner in order to divert the intellect, I especially praise the sonnets, capitoli, and strambotti that I have seen, read, and understood by you, by others, and by me.[50]

[48] Remo Giazotto has published eight sonnets concerning numerous members of Willaert's circle and assigned their authorship to Fenaruolo; see Harmonici concenti in aere veneto (Rome, 1954). Inexplicably, no other reference to the book said to have contained the sonnets can be found, including by the staff at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Rome (private communication). I have searched over forty libraries in Italy and many others elsewhere in Europe and in North America.

[49] See Giuseppe Turrini, L'Accademia Filarmonica di Verona dalla fondazione (maggio 1543) al 1600 e il suo patrimonio musicale antico, Atti e memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura, Scienze e Lettere di Verona, no. 18 (Verona, 1941), p. 184, Appendix A, passim; and the newer publication, idem, Catalogo delle opere musicali: città di Verona, Biblioteca della Società Accademia Filarmonica di Verona, BMB, ser. I, no. 18 (Bologna, 1983). See also Cardamone, The "Canzone villanesca alla napolitana" 1:175-78.

[50] "Sì come bene ispesso; la grossezza de i villani cibi, ò Magnifico S. Domenico; incitano l'appetito a una avidità di gola, che altra delicatura di signorili vivande, non mai la mossero al piacere del mangiare in tal' modo; così alle volte il triviale de i suggetti infimi aguzzano lo ingegno, con certa ansia di prontitudine, che in sorte d'alcuna Heroiche materia non dimostròssi mai tale. Sì che nel comporre per recrear' lo intelletto in lingua, in stile, & in foggia Venetiana, laudo sommamente, i Sonetti, i Capitoli, & gli Strambotti, che ho visti, letti & intesi da voi; da altri, & da me" (Lettere 5:218'). (Aretino's trio of triads in the last sentence — lingua / stile / foggia; sonetti / capitoli / strambotti; visto / letti / intesi — undoubtedly plays on Venier's correlative technique.) Girolamo Ruscelli also mentioned Venier's capitoli satirizing pedantry (now apparently lost), in Del modo de comporre in versi, nella lingua italiana (Venice, 1559): "Molto vagamente pur' in quest' anni stessi hanno il mio Signor Domenico Veniero, et altri nobilissimi ingegni introdotto di scrivere in versi Sciolti, & di Terze rime, alcuni soggetti piacevolissimi, & principalmente volendo contrafar la pedanteria. . . . & non so se questa, nè altra lingua habbia sorte di componimento così piacevole. De' quali io ò in questo stesso volume, ò (se pur questo venisse soverchiamente grande) in qualche altro spero di farne dar fuori alcuni, che sieno per pienamente dilettare ogni bello spirito" (Even in these very years my Signor Domenico Venier and other most noble talents have very charmingly introduced writing in blank verse and terze rime on some very light subjects, principally wanting to make a burlesque on pedantry . . . and I don't know if this, or any other language may have a sort of composition so pleasing. Some of these I, either in this same volume, or [should it yet become excessively long] in some other one, hope to issue, so that they may delight utterly every beautiful spirit); p. lxxviii.

Until recently nothing else has been known of this aspect of Domenico's literary activity (unlike that of his brother Lorenzo and nephew Maffio, both famous dialect poets). But a codex at the British Library, MS Add. 12.197, preserves a full-length autobiographical canzoniere in dialect composed as an exchange between Domenico Venier and another nobleman named Benedetto Corner.[51] The collection turns on the two men's relations with a woman named Helena Artusi, whom both claim to have "chiavà" (screwed). The opening sonnet "del Venier a i Lettori" describes the authors of the poems: "One has the name Domenico, the other Benedetto; one comes from ca' Corner, the other from ca' Venier, and is sick in bed" (Un ha nome Domenego, e Benetto / L'altro; questo si se da ca Corner; / L'altro è da ca Venier, ch'è gramo in letto; vv. 9-11).[52]

The collection is organized as a risqué canzoniere, a low dialect countertype to Petrarch's Rime sparse. Some of the poetic forms stand outside, in some cases beneath, the Petrarchan canzoniere, including capitoli, sonnets "con ritornelli," madregali, madrigaletti, and barzellette; others — canzoni and sonnets "senza ritornelli" — are standard Petrarchan types.[53] Many are in dialogue, mainly with Helena, and a few mention various contemporaries — a "Cabriel Moresini" and the mid-sixteenth-century poet "Domenego Michiel," for example.[54] In order to expand the conceit into a larger social-literary exchange, they also pin Helena's name as alleged author to fictitious rejoinders to their own defamatory verse.

It may seem paradoxical that Venier, like the madrigalists, should have simultaneously practiced two such opposed stylistic levels with equal zeal. But it was not so

[51] Perhaps this Corner is the one Aretino called "il Cornaro patron mio" in the same letter excerpted in n. 50 above.

[52] The manuscript, which I chanced upon at the British Library, had never been discussed in any secondary sources until I shared it with Tiziana Agostini Nordio. She examined my film of the manuscript, corroborated my suspicion of its authenticity, and pointed me to the Aretino excerpt cited above. She has since published a descriptive account of the manuscript, "Poesie dialettali di Domenico Venier," Quaderni veneti 14 (1991): 33-56, listing the identifications of Briquet numbers that I made based on my watermark tracings and supplying some information on Helena Artusi (pp. 37-38). I might modify the last of these with the information that Artusi's death was lamented in a sonnet set by Giovanni Nasco and printed in his Second Book for five voices in 1557, "Hor che la frale e mortal gonna è chiusa" (see Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:460), providing a probable terminus post quem of 1556/57 for the codex. Some of the poems ascribed to Maffio Venier (Domenico's nephew) in I-Vnm, MSS It. cl. IX, 173 (6282), probably belong to Domenico, as indicated by their references to his physical condition; see Antonio Pilot, "Un peccataccio di Domenico Venier," Fanfulla della domenica 30 (1906; repr. Rome, 1906). (Though evidently unaware of the British Library MS, Pilot points out, pp. 6-8, that the Marciana codex exchanges dialect verse with a Corner, refers to a Helena, and to Venier's illness.)

For a discussion of dialect verse generally among the Veniers see Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan, pp. 17-19, 37-38, 51-57, 186-89, and passim; and Bodo L.O. Richter, "Petrarchism and Anti-Petrarchism among the Veniers," Forum italicum 3 (1969): 20-42.

[53] All of these are detailed in the prefatory sonetto caudato on fols. 1'-2.

[54] Michiel is surely not the Domenico Micheli of Bolognese musical fame, but a poet anthologized at midcentury. The latter has sixteen poems published under the name "Domenico Michele" in the Libro terzo and Libro quarto (1550 and 1551) of the Rime di diversi series — in all fifteen sonnets and one capitolo. One of the sonnets in the Libro terzo is dedicated to Venier.

in the world of Renaissance styles and conventions, epitomized by the Venetians' pragmatic acceptance of such contradictory modes and their arduous attempts to explain and order them by appeal to Cicero. As early as 1541 a composer called Varoter — apparently a Venetian nobleman fallen on hard times — dedicated his four-voice villotte to no less a patron than Duke Ercole of Ferrara with the apologia that "just as a man whose ears are filled with grave and delicate harmonies, satiated as at a royal banquet, feels a desire for coarse and simple fare, so I have prepared some in the form of rustic flowers and fruits."[55]

It is hardly surprising that a prominent patrician and former senator would have kept such activities close to the vest. Venier was a figurehead in a different sense from Willaert. The civic ideals that the chapelmaster was expected to reflect in his official capacity were ones that Venier was obliged to embody as their very font. While Venier and his noble friends might act in paradoxes among one another, these were not for everyone to see. Unlike professional, salaried musicians, they sent works to the press not as the servants of consumer audiences but as representatives of their class. And what they did not send the press — whether high or low — was as much a register of class differences as what they did. The pervasive presence of a variety of stylistic registers through all social classes should therefore not be taken as erasures of class differences at the base of social structure. On the contrary, the modes in which styles, and the tropes and dialects attached to them, circulated on the whole maintained, rather than surrendered, the claims of class.

Improvised Song