PART THREE

RITUAL AND KINSHIP

7

The Magic of Capitalism and the Mercantile Elite

Magical Capitalism

Most efforts to describe Nakarattar business point to Nakarattars' ascetic life style and their total commitment to business, in short, to a Hindu version of Weber's Protestant ethic (Day 1972; Mahadevan 1976; Siegelman 1962; Thurston 1909). Mention is made in passing of their massive religious endowment, of their construction of lavish houses in their homeland of Chettinad, and of their extravagant dowries. But such apparently nonbusiness, nonprofit activities are not integrated with the otherwise totalistic Nakarattar business ethic. Indeed the question of how these activities are integrated is scarcely treated.

The most important exception to this generalization is provided indirectly by Milton Singer's (1972) effort to develop a non-Weberian interpretation of Hindu industrialists in 1960s Madras. Yet even here, despite trenchant criticism of many of Weber's arguments and a powerful analysis of the positive role of joint families in industrial organization, Singer ultimately offers a Weberian apologia for the coexistence of Hindu ritual and capitalist practice. Along with Weber, Singer apparently assumes that ritual and business are inconsistent and suggests that Hindu businessmen compartmentalize their religious life from their business life, conducting worship in their homes and temples in as minimal fashion as possible. Moreover, he suggests that religious endowments and other ritual gifts represent compensatory devices by which businessmen pay other people to worship for them. He labels this rather Catholic interpretation of Hindu religious gifting as vicarious ritualization .

To my knowledge, no one has taken issue with Singer on this interpretation. Yet it depends crucially on three problematic assumptions. They involve, respectively, a mistake about historical fact, an ethnocentric view of religion, and a failure to appreciate the radical but incomplete transformation of Hindu religious endowments under colonial and postcolonial rule.

Historical issues arise in Singer's implicit assumption that religious endowment, as a form of vicarious ritualization, is a novel ritual response to a novel business climate. Yet it is clear from published South Indian cases of religious gifting in eleventh-century Chidambaram (Hall 1980; Spencer 1968), fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Tirupati (Stein 1960), seventeenth-century Palani (Rudner 1987 and this chapter, below), and nineteenth-century Madurai and Ramnad (Breckenridge 1976; Price 1979) that this assumption is wrong. In each of these cases, various forms of religious gifting constituted mechanisms by which merchants and mercantile communities entered a new locality, created viable social identities, and gained authoritative entitlement for their commercial enterprises. It is also quite clear that temples which received merchant endowments acted as capital-accumulating institutions, that mercantile leaders were frequently able to exercise control over temple expenditure and investment, and that this control included reinvestment in the business enterprises of the merchants themselves. In other words, religious endowment has been a central component in Hindu business practice since long before the age of instant communication, rapid transportation, and capital-intensive industry.

Moreover, the problem with interpreting religious endowment as vicarious ritualization goes far beyond incompatibility with historical fact. At its core, such an interpretation relies on an ethnocentric assumption that religion is, by definition, other-worldly and that it interferes with secular, this-worldly business concerns. Conversely, such an interpretation implies that mundane goals such as profit making interfere with genuinely religious ends such as attaining or proving salvation. From this broadly Weberian perspective—and Singer must be included among the Weberians in this regard—just such a dichotomy between secular and transcendental realms was the stimulus to Protestant ascetic individualism, in which all this-worldly profits were directed toward the public good so as not to interfere with the other-worldly goals of the individual. But it does not follow from this argument that in religions where ritual action is magical , in the sense that it is directed toward this-worldly ends, it is incompatible with personal asceticism or even individualism.

This chapter examines crucial connections between this-worldly Nakarattar ritual—both religious and secular—and more "formal" Nakarattar commercial activities in two historical periods separated by

three centuries. In addition, it illustrates the continuing role of the Nakarattar elite in South India's political economy. The exercise will demonstrate that in both historical periods, members of the Nakarattar elite made rational use of economically "irrational" ritual in their capacity as central links in a collectively oriented, political economy, whose participants included the Nakarattar caste as a whole, noncaste investors, religious and educational institutions, and political authorities.

Nakarattar Worship and Trade in Seventeenth-Century Palani

Palm-leaf manuscripts (olais ) maintained at Palani Temple in Madurai District make it possible to reconstruct the way the Nakarattar caste carried out its business and participated generally in seventeenth-century South Indian society. These manuscripts, which constitute the Nakarattar Arappattayankal (The Six Nakarattar Deeds of Gift),[1] confirm Nakarattar oral tradition that the caste was primarily involved in the trade of salt. In addition, the records provide important information about the mechanics of trade and particularly about the crucial connections that existed between trade and religion.[2]

|

The "deeds" (pattayams ) tell a story, beginning in 1600, of the initiation and growth of Nakarattar trade in the pilgrimage/market town of Palani and of the concomitant growth in Nakarattar ritual involvement and religious gifting to Palani Temple. The story begins with the arrival in Palani of Kumarappan, a Nakarattar salt trader from Chettinad, "The Land of the Chettis." The manuscripts describe his first contact with a Palani Temple priest, his initial worship (puja ) of the temple deity, the growth of his commercial activities in the temple market, and his endowment of the temple and subsequent installation as a trustee (dharma karta ) of the endowment.

According to these texts, Kumarappan was the first Nakarattar to establish trade in the salt-deficient region of Palani. He stayed in the house of the Palani Temple priest and operated his business in the street outside the priest's house. From the beginning, he marked up his margin of profit by one-eighth and gave the markup as an offering and tithe (makimai ) to the deity of Palani Temple, Lord Velayuda (a manifestation of Murugan). Food paid for by Kumarappan's makimai was prepared by the priest's wife and offered to the deity by the priest. Afterwards it was distributed as sacramental food (prasad ), first to the priest and then to Kumarappan, his employees, and local mendicants (paradesis ). In addition, Kumarappan paid the priest and his wife each a small sum of money (two panams ).

In other words, even at this early stage, commerce entailed much more than simply opening up a shop in the local marketplace and setting prices for goods according to local conditions of supply and demand. In particular, it involved establishing a relationship with the deity of Palani, mediated by the deity's priest. Kumarappan satisfied this condition by undertaking regular acts of individual worship (arccanai ) on a monthly basis each time he returned to Palani to trade.

Kumarappan not only expanded his own salt trade in Palani during the next few years but also, in the fourth year, was instrumental in bringing five additional Nakarattar salt traders into the community. Kumarappan arranged for each of them to emulate his lead and mark up their profit for makimai given as part of individual worship of the Palani deity conducted by the temple priest. In the first deed of gift, Kumarappan attests,

"The gift of food has been on the increase since I first came here. My profit goes on increasing from the time Parvati [the priest's wife] started cooking for us. Until now the funds that accrued by way of profit markup for the Lord were eighty-five rupees. This time I got forty-two panams through profit markup. Thus there is a total of rupees 96-4-0 for the Lord." So thought Kumarappan. This way the Lord made a profit and the sons of Chettis also made a profit. The Nakarattars came to know of this. Some of them started working for wages for the Lord and some for Kumarappan of Nemam. Four for the Lord and two for him. This way they came selling salt, stayed in Pandaram's house, and ate what Parvati cooked for five or six years. Through markup and straight profit the Lord gained one hundred to one hundred and twenty varakans [one varakan = Rs. 3.5].[3]

News of the successful Nakarattar business venture reached a local chief in political control of Palani (the Nayak of Vijayagiri) and the Pandyan king of Madurai (Tirumali Nayak), who was sovereign over the Tamil kingdom encompassing Chettinad and Palani. News of Nakarattar

trade also reached the Saivite sectarian leader, Isaniya Sivacariya, whose monastery was located in Piranmalai at the western edge of Chettinad. The sectarian leader was guru both to the Pandyan king and to all male Nakarattars. He proposed that Kumarappan should arrange for an annual pilgrimage, sanctioned by the Pandyan king, to celebrate the deity's wedding on a date in the Tamil month of Tai (corresponding to January–February in the Roman calendar).

The collective worship of the pilgrimage and marriage festival was significantly different from the individual worship in which Kumarappan and the other Nakarattars initially engaged. Individual worship (arccanai ) established a more or less private relationship between trader and deity, mediated by the priest. But the pilgrimage established a collective festival (tiruvila ) and generated a system of ritual transactions between all the notables of the Palani community: not only traders, priests, and deity, but local chiefs, paramount kings, and sectarian leaders. By participating in the annual festival, each of these notables recognized and ritually sanctioned the social identity of all of the others.

For Kumarappan, the annual pilgrimage took on significance far beyond what it offered to his fellow Nakarattar salt traders. Kumarappan was the founder and organizer of Nakarattar trade and worship in Palani. He was the person to whom the sectarian leader went in order to establish the pilgrimage for the first time. He was the person who made preparations for lodging, transportation, food, and worship for all of the pilgrims. He even conveyed the Palani priest to the sectarian leader's monastery for the beginning of the pilgrimage. Finally, and significantly, Kumarappan was entrusted with collecting and managing all funds donated by the pilgrims as regular fees at recurring rituals of monetary gifting during the pilgrimage, and ultimately with managing an endowment (kattalai ) initiated by Kumarappan to maintain the pilgrimage in perpetuity.

As manager of the endowment, Kumarappan was not only the master of ritual ceremonies, but also the chief executive of what amounted to a joint business venture with the deity of Palani. His managerial position carried, in addition to ritual honors, the responsibility of investing all funds endowed for worship of the deity. There was no specification or limit as to how these investments should be made. His appointment as dharma karta —the executor of important collective rituals—was recognized by kings, sectarian leaders, and priests, but his actions were sanctioned only by the deity himself. Kumarappan shared some honors with other notables who were similarly generous in contributing to temple endowments. But his special status reflected not only his generosity (vallanmai ) but also, and perhaps more importantly, his fiduciary trustworthiness

(nanayam ) and his commitment and effectiveness as a businessman. The honors he received did not simply recognize his worship of the deity (in either private or collective forms). Nor were they given in recognition of his personal offerings to the deity as a part of worship (in makimai or kattalai ). Rather, Kumarappan's honors recognized his special role in stimulating and managing the worship and donations of other Nakarattars. In effect, the collective worship at Palani constituted Kumarappan as a leader of the Nakarattars, and empowered him to act as trustee of all funds donated to the deity. His honors were the emblems of his office.

Temples as Political Institutions in the Seventeenth Century

The preceding interpretation of Nakarattar religious gifting at Palani fits within recent historiographic interpretations of South Indian temples as not simply architectural structures but also institutions that carried out two important social functions in South Indian society: (1) a group formation function, as the focus for collective acts of capital accumulation and redistribution; and (2) an integrative function, as political arenas for corporate groups formed by collective redistributive action. Although little attention has been paid to the role of individual gifts (arccanai ) in this regard, the operation of collective gifts (kattalai ) has become increasingly clear.

In a definitive paper on the ritual and political operation of South Indian temples, Appadurai and Breckenridge (1976) address the group formation function of temples. They integrate anthropological insights about the association of political chieftainship and economic redistribution with case studies of temple donors and their identity as leaders of various corporate groups, including families, castes, guilds, kingdoms, and even business corporations. Interpreting endowment to a temple as a form of collective gift, the researchers summarize their findings about endowment as follows:

(1) an endowment represents the mobilization, organization and pooling of resources (i.e., capital, land, labor, etc.);

(2) an endowment generates one or more ritual contexts in which to distribute and to receive honors;

(3) an endowment permits the entry and incorporation of corporate units into the temple (i.e., families, castes, monasteries or matam -s, sects, kings, etc.) either as temple servants (stanikar -s, managers, priests, assistants, drummers, pipers, etc.) or as donors;

(4) an endowment supports, however partially and however incompletely, the reigning deity. But, because the reigning deity

is limited since it is made of stone, authority with respect to endowment resources and ritual remains in the hands of the donor or an agent appointed by him or her. (Appadurai and Breckenridge 1976: 201)

In other words, an endowment entails collective action, ritual designation of a leader, allocation to that leader of authoritative control over collective resources, and recognition of the group as a corporate entity represented by the distinctive role of its leader on various occasions of worship to the deity. Appadurai and Breckenridge, however, draw their conclusions about the group formation function of endowment primarily from research on practices in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. My interpretation of the seventeenth-century deeds of gift from Palani builds on their interpretation and demonstrates that such processes were also in play at least two hundred years earlier.

Complementing these findings about the role of temple endowment in group formation, studies on the overall political role of temples in South Indian society during the Vijayanagar period (1300–1700) make it clear that temples served a second political function (Appadurai 1981a; Mahalingam 1967; Stein 1977, 1980). Specifically, temples played an integrative role in regional politics by providing an important interactional arena for extralocal sovereigns, leaders of local corporate groups of various kinds, and religious sectarian leaders. Appadurai's (1981) work on Vaish-navite sectarian movements offers an especially useful takeoff point for the present study. It develops a model of mutual recognition and legitimization between extralocal sovereigns and local sectarian leaders mediated by temples in the seventeenth century. According to Appadurai,

Warrior-kings bartered the control of agrarian resources gained by military prowess for access to the redistributive processes of the temples, which were controlled by sectarian leaders. Conversely, in their own struggles with each other, and their own local and regional efforts to consolidate their control over temples, sectarian leaders found the support of these warrior-kings timely and profitable. (1981: 74)

Such political interpretations of worship have recently been subject to criticism by C. J. Fuller, who argues that they are based on an interpretation of puja (worship) as an asymmetric exchange between god and devotee that ultimately reduces puja entirely to politics (1992: 81). Fuller disagrees with this premise, arguing that devotees exchange nothing with their gods in acts of worship. Instead, they express devotion with various offertory actions (upacharas ) which the gods find pleasing. In Fuller's view, the gods never actually either consume or alienate these offerings.

As a consequence, the gods are under no obligation to reciprocate by making any counterprestation to their devotees. Yet, out of pleasure with their devotee's devotion, they bless the offering--which the devotees, not the gods, subsequently consume.[4]

Fuller recognizes that temple rituals include a distribution of divinely transvalued offerings (prasad ) and honors (maryatai ). But, contrary to many standard analyses (e.g., Babb 1975), he insists that these sacralized offerings should not be confused with tangible leftover substances (jutha ) from divine consumption (Fuller 1992: 77). Further, he insists that the ritual distribution of prasad and maryatai is completely separable from the performance of the various upacharas, the offertory rituals which Fuller designates exclusively as worship (puja ). Finally, he insists that, unlike the distribution of prasad, the offering of an upachara is free from the taint of politics. For Fuller, the root Hindu metaphor for understanding puja reflects not the political relationship between king and subject but the domestic relationship between husband and wife, exemplified by the wife's preparation of meals and her consumption of leftovers (1992: 78–79).

Fuller, it seems to me, goes too far in separating the political aspects of ritual located in the distribution of prasad and maryatai from the domestic aspects of devotional offerings in puja . To begin with, his appeal to the relationship between husband and wife as a root metaphor for understanding upachara calls the whole issue into question since, as he recognizes himself, the wife does consume her husband's leftovers. Secondly, the redistributive model proposed by Appadurai and Breckenridge is not limited to interactions between priests and deities. On the contrary, whatever goes on between priest and deity, the Appadurai-Breckenridge model is primarily concerned with a system of indirect exchanges between devotees. (Indeed, it could be argued that the Appadurai-Breckenridge model is problematic because it leaves priests, as mediators with gods, entirely out of the picture!) According to Appadurai and Breckenridge, the system is initiated by a donative group which pools its resources and presents an offering to its leader. This leader, in turn, presents the collective offering to a priest, who (not to beg the issue) does something which sacralizes the offering in a ritual interaction with the deity. The priest then returns the sacralized offering to the leader of the donative group, who then distributes it to his followers. Fuller addresses neither the obvious questions that arise about his interpretation of husband-wife relations as lacking exchange or the irrelevance of the mechanics of sacralization for the exchange processes that concern the Appadurai-Breckenridge model. As a consequence, his rejection of a model of exchange between devotee and

deity and his refusal to identify prasad and maryatai with jutha must remain controversial for the time being.

Fortunately, the precise status of upachara rituals does not affect the general arguments I have made about the entire redistributive sequence of temple rituals, of which upacharas form only one part. Upacharas , after all, represent the liminal offertory phase of a long ritual sequence, which begins with purificatory acts that remove devotees from everyday life in preparation for interaction with the gods and which ends with the asymmetric distribution of prasad and maryatai that reconstitutes society. No one would disagree that it is possible to isolate phases of separation, liminality, and incorporation in any ritual sequence (van Gennep 1909; Turner 1977 [1969]). It is not clear, however, that any such phase should be viewed as exclusively either political or domestic. Moreover, if the entire sequence of rituals is taken into account—and it is the entire sequence that concerns us in interpreting both arccanai and tiruvila forms of worship—then it is impossible not to observe the pattern of collective pooling and redistribution that lies at the heart of the Appadurai-Breckenridge model.

I agree with Fuller that this model is overly dominated by a political perspective. Appadurai's analysis, in particular, focuses precisely on the role of kings and sectarian leaders in society—an emphasis which, in its concern with kingship, reflects a resurgent theme in South Indian studies that has disinterred the work of A. M. Hocart (1950) on Indic society as a kingship-centered ritual polity (see also Breckenridge 1977; Dirks 1988; Price 1979). The correction, however, lies not in denying any role for politics in religious ritual but in seeing how politics participates in ritual. Puja involves a variety of actors in Indian society. By taking them into account, in their variety, it becomes possible to explore nonpolitical dimensions of puja without rejecting the role of politics.[5] In the present context, my analysis of events at Palani demonstrates how an actor who is neither king nor sectarian leader, but an itinerant trader, used both integrative and group formation properties of collective rituals, and also the less-encompassing rites of individual gifting and worship, to enter the local polities and market towns of South India. Given the political bias of the Appadurai-Breckenridge model and given Fuller's misgivings that it is blind to Hindu devotionalism, it is important to emphasize that neither the political perspective represented in Appadurai's work nor the economic perspective represented here denies or excludes the more soteriological concerns that have traditionally defined Western understandings of religion. On the contrary, my central argument continues to emphasize the inseparability of religion, politics, and economics.

Purity, Protection, Trust, and Mercantile Elites

Kumarappan, who led his mercantile castemates into the ritual/market center of Palani, displayed the markers of leadership worn by leaders of any group in caste society. He was the yajaman: the sacrifier (Hubert and Mauss 1964) who collected his group's pooled resources, offered these resources in his capacity as the group's ritual representative at the court of a godlike king or kinglike god, and then received and redistributed the resources (sanctified by contact with king or god) back to his group. The ritual process constituted Kumarappan as the group's leader and, indeed, constituted and reconstituted both the leader and the group itself on every occasion of its performance.

This Hocartian model is extremely useful, but extremely general. Caste society is portrayed as a segmentary society bound together by rituals of religious gifting in which all take an equal part. Viewed from its perspective, the leaders of any group are identically sacrifiers: replicas of one another and ultimately replicas of the king who is sacrifier for all of society. But this very generality raises a crucial question. If the ritual representatives of any group in society are equally sacrifiers for their groups and, in this respect, replicas of each other, what distinguishes their ritual roles and the ritual roles of the groups they represent?

Answers to this question that are available in the literature are partial at best. The most prominent one concerns just the ritual role of priests and no other ritual specialty. The answer, alluded to by Hocart himself (1950) and developed in some detail by Hubert and Mauss (1964), distinguishes priests from sacrifiers on the basis of their role as sacrificers —that is, as ritual specialists whose specific function is to convey the offering from sacrifier to king or deity. Ethnographic studies exploring the role of the priest in Indian society have focused most often on Brahman priests (Appadurai 1983; Babb 1975; Fuller 1979; Harper 1964), although a few have focused on non-Brahman priests (Claus 1978; Dumont 1957a; Inglis 1985; Parry 1982). In either case, the analyst's attention has been drawn to aspects of the priest's identity that qualify him for this special role: his ritual purity in the case of Brahmans, and his impurity in the case of non-Brahmans.[6]

Such studies lead in turn (it seems inevitably) to a Dumontian conception of caste society as structured by principles of hierarchy—narrowly construed as group ranking along a status dimension of relative purity (Dumont 1980 [1970]). Yet the fact of the matter is that ritual purity primarily concerns only a single ritual identity: that of the sacrificial or mediatory priest.[7] Hindu values of relative purity are largely irrelevant to

other identities involved in the processes of religious gifting—including, notably, processes of endowment to Hindu temples. Purity or impurity may qualify an individual to act as a priest. It may even provide sufficient ground for denying entrance of an entire group to the donative and redistributive processes that constitute a temple community (for case studies, see Breckenridge 1977; Hardgrave 1969). But once a group is recognized as a legitimate participant in a temple's transactional network, relative purity is not necessarily relevant for assessing its ritual relationship to other groups (Appadurai 1981b). We are again left with the question of what distinguishes the ritual roles of different groups and their representatives in the court of king or deity and in society as a whole.

As we have seen, a Hocartian alternative to the focus on priests and purity focuses on the identity of the king as royal donor. In Hindu contexts, gifting—especially endowment—operates to integrate any actor into the moral community of a temple. Generosity (vallanmai ) is the moral obligation (dharma ) of any wealthy man. Accordingly, it is necessary to identify the particular quality that sets the king apart from other sacrifiers. Case studies of South Indian kingdoms suggest that the quality that distinguishes kings from other donors is their additional status as royal protector (paripalakkar: Breckenridge 1977). The Nayak of Vijayagiri embodies this role in the history of Palani.

Taken together, the Dumontian and Hocartian approaches identify and distinguish the ritual identities of two separate transactors in networks of religious gifting. But even in combination, they provide definitions only of the identities of kings and priests. In my analysis of Nakarattar entry into Palani, I have provided an analysis of the ritual identity of still one more transactor in a temple's ritual network, the elite merchant: an identity that has received remarkably little attention, given its importance for temples and for South Indian society generally. Kumarappan's identity in the network of interacting identities that made up a seventeenth-century temple was that of endowment manager. His salient status in this capacity (and, in later times, the salient status of temple managers and trustees) was evaluated along a dimension neither of relative purity nor of kingly protection, but of fiduciary trustworthiness. In his capacity as trustee, Kumarappan transacted with the deity and with other members of the temple community. In return he received a rightful and tangible share of the endowment that he managed. In the history recorded by the Palani manuscripts, this share took form of the temple's reinvestment of Kumarappan's and others' donations back into Kumarappan's business. This, in turn, led to further endowments to the temple and increased Nakarattar involvement in the Palani economy.

Worship and Commerce

In sum, the history of Nakarattar religious gifting at Palani temple exemplifies Nakarattars' involvement with temples throughout precolonial South India. Religious gifts performed not only religious and political functions but also distinctive economic functions, including the acquisition and reinvestment of funds in mercantile enterprises. Just as there was no separation of religion and politics—indeed, in many ways, worship was politics—so, too, there was no separation of religion and economics. The Nakarattar caste and other castes of itinerant traders engaged in worship as a way of trade, and they engaged in trade by worshiping the deities of their customers. The system as a whole constituted a profit-generating "circuit of capital" in which the circulating capital comprised a culturally defined world of religious-cum-economic goods. Nakarattars "invested" profits from their salt trade in religious gifts. Religious gifts were transformed and redistributed as honors. Honors were the currency of trust. And trustworthiness gained Nakarattars access to the market for salt. Elite Nakarattars acted as intermediaries between the various institutions that controlled production and access to salt, money, gifts, and honors.

As commerce expanded in the seventeenth and subsequent centuries, so did the demand for and supply of money. The Nakarattar caste, already specialized around activities of money accumulation and investment, was preadapted to take advantage of this commercial expansion. Its territorial isolation placed it at a temporary disadvantage relative to coastal castes that first established links with the growing international trade, especially the trade in textiles. But Nakarattars' ritual techniques for penetrating new markets, pooling capital, and transmitting money would very quickly overcome the early geographic advantages of their competitors.

The Emergence of Provincial Politics

From the Nakarattars' seventeenth-century entrance into Palani, I now want to shift attention to their twentieth-century entrance into the city of Madras. The database for the later period is naturally much richer, and the picture of Nakarattar activities much more complicated. Before attempting to sketch this picture, I provide some background information about overall trends in colonial politics. During the last few years, a number of influential historians have called attention to an evolutionary dimension in nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonial Indian politics. The evolution they describe reflects a decentralization of British power and the development of representational forms of Indian government.[8] The trend was officially initiated by passage of the Ripon reforms in 1884 and 1892. But

it is generally agreed that Indian colonial government resisted the spirit of the Ripon proposals until passage of the Morley-Minto Act of 1909, the Montague-Chelmsford reforms of 1921, and the Government of India Act of 1935.

The details of these government acts need not detain us. Their cumulative effect was to provide for Indian nominations and elections to municipal, district, and provincial governing bodies, with local and district boards electing members of the provincial legislative assembly, and the legislative assembly and chief minister nominating members to local boards. These institutional changes, in turn, encouraged participation of local elites in the provincial government in order to retain and, in some cases, increase political power in their home districts and municipalities.

From the British point of view, the changes represented a decentralization and sharing of power with indigenous elites. From the Indian point of view, however, the changes are more accurately viewed as a move toward centralization. Rural elites, whose bases of power had been focused on villages, towns, small administrative units called taluks , or the kingdomlike (or chiefdomlike) landed estates called zamins , began to participate (directly or indirectly) in integrated political action in the provincial capitol of Madras City.

This is not to say that precolonial local polities were unintegrated in regional and pan-regional networks. But our understanding of precolonial political integration remains tentative at best.[9] Consequently, it is difficult to tease apart features of the evolutionary model of colonial decentralization and "Indianization" that concern genuine integration of imperial/ provincial politics and local politics from features of the model that merely reflect a British style of integration. In particular, it remains remarkably difficult to compare the degree of integration maintained by colonial governments, in both their centralized and decentralized phases, with the degree of integration maintained by an enormously varied assortment of indigenous temples, religious sects, and chiefs and kings ruling over pre-British chiefdoms and empires.

The Creation of "the Public" and the Question of Privilege

In the present context, the comparative issue arises in attempting to evaluate the changing role of mercantile elites in commerce, worship, and politics. In what follows, I examine some notable ruptures and an important continuity in the political style of elite Nakarattar merchants between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, particularly with regard to elite religious gifting and its nineteenth- and twentieth-century secular counter-

parts. As we have just seen, religious endowment (kattalai ) in the seventeenth century was meaningful as an offering in a collective act of worship (tiruvila ). It represented one component in a paradigm of religious gifting and should be understood, in part, in opposition to merchant tithes (makimais ) offered in individual acts of worship (arccanai ). A temple manager (dharma karta ) who managed endowments in the interests of the deity did so by virtue of his own business acumen and wealth. As the deity prospered, so did the temple manager; as the temple manager prospered, so did the deity. There was no necessary separation in the interests of the two. On the contrary, deity and temple manager were mutually dependent.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, however, as the British consolidated and centralized their power, all institutions that played an important role in the apparatus of government underwent a transformation, including temples.[10] Initially, early nineteenth-century district collectors, the primary agents and directors of British rule, acted as kingly donors and protectors of Hindu temples, supporting and even acting as dharma kartas . Gradually, under a series of reform-minded government acts, the collectors acceded to missionary pressure and attempted to withdraw from governmental involvement in Hindu worship. But the more they struggled to free themselves from participating in temple politics, the more entangled they became: withdrawal entailed finding suitable native trustees to oversee endowments for which the British collectors had held responsibility; finding suitable trustees entailed setting standards for suitability; and setting standards entailed defining the role of the trustee, of the trust, and ultimately of the deity itself.

Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, temples became encompassed in Anglo-Indian law under the general category of religious and charitable institutions.[11] The social meaning of endowment took on British values, focused around ideals about secular philanthropy and Christian religion. Religious gifting came to be considered, by extension from British norms, as transcendental or other-worldly in orientation—a development with particularly dramatic implications for the evolving colonial conception of a deity and its chief devotee, the dharma karta . On the one hand, the deity itself came to be viewed as a kind of public property; access to it, as a public right; endowments to it, as public trusts. On the other hand, the dharma karta came to be defined, in the first instance, as the trustee of a public fund, with fiduciary responsibility for the deity. From this new perspective, if religious gifting had (by definition) the "nonreligious" side effect of creating an investable fund of capital, such a fund was considered a public resource, not the karmic property of private shareholders in a venture undertaken by deity and devotees. Under law, a

trustee might receive a fee for services or expenses, but under no circumstances should he receive a share of the trust fund over which he had control, for this would have involved him in a conflict of interest with the deity and with the public good.

In sum, the colonial reinterpretation of religious endowment as a form of philanthropy separated the interests of deity and trustee and gave an entirely new meaning to religious gifting. Worship in the colonial period was interpreted by law as either private or public —a significant difference from the precolonial distinction between individual and collective worship. It does not follow from this change, however, that precolonial values no longer played a role in colonial (or postcolonial) society. In what follows, I will suggest that they simply disappeared from view. Moreover, although officially banned from large-scale, "public" temples, precolonial values continued to operate in the myriad "private" temples that fill the Indian landscape. Indeed, there are good reasons to believe that these values are still operating invisibly—albeit illegally—in institutions officially classified as public including public institutions that are secular rather than religious. This, at least, is the view that underlies my interpretation of the following account of Nakarattar gifting, religious and secular, in the twentieth-century port city of Madras.

The Case of Raja Sir Muthia and the Politics of Madras, 1928–1969

Nakarattars' commercial interests in Southeast Asia involved them in such Tamil port cities as Tuticorin and Dhanuskodi from at least the beginning of the nineteenth century. But they played no significant role in Madras City until the construction of a modern harbor in 1896. Accordingly, and justifiably, accounts of Madras City politics before their arrival make no mention of them. Less justifiably, Nakarattars are also largely absent, or underappreciated, in twentieth-century studies. The absence seems attributable to an overwhelming historiographic bias toward questions about the Indian nationalist movement. And even studies that focus on the loyalist Dravidian Renaissance and anti-Brahman movements (which I touch on, below) do not address the issue of specifically mercantile political interests.

Nevertheless, once the Nakarattars had been lured into Madras by the newly built harbor, they began to participate in city politics in a major way: for example, by forming a caste association with special representation on the legislative council and port trust, and by establishing and dominating an Indian Chamber of Commerce, which also had representation in government administration. Nakarattars are thereby distinguished

from mercantile elites in preceding eras, who seem to have been eclipsed not only by Nakarattars, but also by rising administrative and professional elites (Suntharalingam 1974). Nakarattars are also distinct from the rural elites with whom they shared the Justice party in the 1920s and 1930s. In this respect, the Nakarattars represent a kind of hybrid elite, combining properties attributed to both the emerging bourgeoisie and the traditional rural magnate.

Of all the members of the Nakarattar elite,[12] the best known, most politically active individuals belonged to the S. Rm. descent line (kuttikkira pankali ). Its most famous branch came to prominence through the business, political, and philanthropic acumen of S. Rm. A. M. Annamalai, who was ultimately recognized by the colonial government with the title "Raja Sir." The notoriety he won for his family and the hereditary title itself are often misconceived as indicating that the house of S. Rm. A. M. constituted a royal Nakarattar dynasty. In fact, the title is a relatively recent British creation. It was not granted to Annamalai until the middle of the twentieth century, and it pertains to his "rule" only over the newly formed village of Chettinad, not over the Nakarattar residential homeland as a whole. There were many other Nakarattar families with equal or greater economic wealth, if not the same political clout—both other branches of S. Rm. and families from totally different descent lines as well. Nevertheless, the history of the S. Rm. A. M. lineage, and especially the careers of Raja Sir Annamalai and his son, Raja Sir Muthia, illustrate both changes and continuities in the role of a South Indian mercantile elite.[13]

On their own behalf and as managing agents for many client Nakarattars, the S. Rm. A. M. lineage controlled businesses in Tamil Nadu, Ceylon, and Burma since at least the middle of the nineteenth century and had offices in Madras City before the advent of the twentieth century. In 1908, Annamalai—with a group of primarily Nakarattar bankers—founded (and took control of) the Indian Bank as a joint stock company in Madras, taking over the niche left after the failure of the British Arbuthnot's Bank.[14] They were involved in the grain, cotton, and salt trade of Madras during the first half of the nineteenth century,[15] and during the twentieth century they further expanded their commercial activities into new areas, including formal, Western-style banking; insurance; textile spinning and weaving; and construction. They operated a powerful agency in nineteenth-century Columbo which became a base for their later involvement in the twentieth-century Ceylonese cement and construction industries (Weersooria 1973). They were among the first Nakarattars to establish a banking agency in nineteenth-century Burma, where they became one of

the largest Nakarattar firms, with many branch offices outside Rangoon, in the Burmese interior. In the twentieth century they have made enormous profits in Burmese timber and oil.

Not surprisingly, members of the S. Rm. A. M. lineage took a keen interest in the political opportunities offered by evolving colonial institutions in Madras. Frequently, these involved profound changes, not just in location (i.e., the establishment of a major agency house and palatial residence in Madras City), but also in political instrumentality. The politics of gifting continued from the seventeenth century on. So did a politics of litigation, which became a central feature of Indian life in the nineteenth century (cf. Breckenridge 1977). In the twentieth century, both of these activities were encompassed by the politics of colonial government.

S. Rm. A. M. Annamalai was among the first Nakarattars—and indeed among the first Indians—to take advantage of the new opportunities. From 1909 to 1912 he was mayor of the municipality of Karaikudi. In 1913, he was elected for the first time to the Madras Legislative Council. I do not have a full record of the total number of terms Annamalai spent as a member of the legislature. In 1920, he served in the Council of State in New Delhi as one of four representatives from Madras Presidency. And in 1923, he may be found winning reelection to the Madras Legislative Council.[16]

From 1920, Annamalai was on the board for the Imperial Bank. At some point in his career he was given the title Rao Bahadur, and later received the title Raja Sir for his political role and financial support in creating a Tamil University at Chidambaram, fittingly named Annamalai University. He was also deeply involved in the Tamil Icai movement: he founded the Raja Annamalai Music College in Chidambaram in 1929, placed it under control of Annamalai University in 1932, and endowed prizes for writing textbooks on Tamil music (Arooran 1980). All of these public and business positions indicate but do not exhaust the extent of his influence in the Madras Presidency, which grew even more powerful after the carefully orchestrated political debut of his son, Muthia.

In 1928, Muthia was appointed to the Madras Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee at the age of 23. From 1929 on, he was a council member in the corporation of Madras. In 1931, the council voted him its president and repeated its choice in 1932. During this period, I am told, Annamalai brought pressure to bear upon the Legislative Council to alter the charter of Madras from corporation to municipality and concomitantly to alter its leadership from a relatively weak council president to a powerful city mayor. This does not seem unlikely because 1933 witnessed Madras City's first mayoralty election. The elections were postponed six months,

until after Muthia's twenty-fifth birthday; the minimal age required of the municipal mayor was twenty-five. Muthia was elected.[17]

Throughout his career, Muthia was active in party politics. He served as Chief Whip and Chairman of the Justice party, where he became known as an independent, pragmatic political moderate. Publicly, he was a staunch Dravidianist and provided strong support for the pro-Tamil movement, both politically and also through endowment and guidance of Annamalai University (Arooran 1980). Behind the scenes, he served his own interests and protected his power base without too much concern for party loyalty or for public canons of political ethics. During the 1934 Legislative Assembly election, Muthia withheld support from Justice party candidates R. K. Shanmugam Chetty (not a Nakarattar) and A. Ramaswami Mudalier. The Justicites lost and the Justice leader, the Raja of Bobbili (the owner of a large, multivillage estate), dismissed Muthia from his position as party Whip. Four months later, Muthia sought revenge: he filed a motion of no confidence in his own party's ministry. Lord Erskine, Governor of Madras, describes what happened next in correspondence to the Governor General of India, Lord Willingdon:

If he were to use ordinary political methods ... nobody could object, but he has set about getting his revenge by what can only be described as mass bribery.... He is reputed to have spent Rs. 30,000 up to now and to be quite prepared to spend another 30,000 as well.... I must say that I thought I knew something about playing funny politics but I must take off my hat to these Indians. They are past masters at the art. The last few days have been an orgy of corruption and intrigue.[18]

Muthia's no-confidence motion failed despite his efforts at "mass bribery." But the setback was only temporary. By 1936, Bobbili needed his support in the face of threats from still other Justice factions and made the redoubtable Muthia a minister in his government.

The effectiveness of the S. Rm. A. M. family's political power is also indicated by the history of protests from dissident Nakarattar factions. For example, in 1937 a Nakarattar meeting in Ramnad denounced the S. Rm. A. M.—controlled, Justicite Nakarattar Association as unrepresentative and pledged support for the increasingly powerful Congress party, the party of Mahatma Gandhi (Hindu , Feb. 2, 1939, cited in Baker 1976: 301). By 1938, the Justice party was out of power and the Congress party had formed its own ministry, but Muthia still had considerable influence. As leader of the Legislative Assembly, he was said to have made a deal with the Congress party government over taxes (peshkash ) on his large landed estates and was censured by the Self Respect Conferences held in Tanjavur and Madurai in 1938.[19]

Such an apparent blow as the 1934 dismissal or the 1938 censure might have weakened the political influence of another man. But, as his political longevity suggests, public office and party position were only two features of Muthia's strength. For changes in the institutional structures of colonial government had not replaced precolonial ritual politics, but blended with them, transforming and being transformed in a complex and mutually adaptive process. In particular, Indian leaders still depended on cultural processes of legitimization to sanction their political authority.

Junctures and Disjunctures in the Culture of Elite Endowment

In keeping with the pattern of the mercantile elites that had operated three hundred years earlier in Palani, Annamalai and Muthia were massive donors to their clan and village temples and to temples serving the local community wherever they did business. But, in addition to these acts of religious gifting, they adopted British notions of public service and philanthropy, involving themselves, from the 1920s onward, in educational projects and works of municipal improvement. At the same time, they transformed the basically European values underlying these activities and harnessed them to a regionally and linguistically based movement of Tamil separatism and revitalization.

It would be a mistake to view the wedding of Tamil and British values as an effect of British policy on a totally reactive Indian population or to isolate that wedding from other processes in Madras society with which it was deeply involved. On the contrary, the roots of the movement for Tamil revitalization can be found in battles fought by early nineteenth-century elites who embraced the British cause of secular education, in part as a weapon in their religious fight against Christian missionaries (Suntharalingam 1974).

As early as 1839, the Governor of Madras, Lord Elphinstone, had promulgated a "Minute on Education," in which he stated, "The great object of the British Government ought to be the promotion of European literature and science among the natives of India.... All funds appropriated [for educational projects] would be best employed on English education alone" (cited in Suntharalingam 1974: 59). The Madras elite who endorsed these goals were largely composed of mercantile families who had maintained a long history of involvement with the British in Madras City. Throughout their history, they had participated in religious and philanthropic activities that combined the responsibilities of trustee described in the case of Kumarappan at Palani with the responsibilities of kingly protector represented by the Palani chief, the Nayak of Vijayagiri.[20] In per-

forming this dual role they fought against Christian missionary efforts to influence colonial policies about Hindu religious practices, and they supported colonial aspirations to separate government policy from religious dogma and controversy. Ironically, as part of their support, they began to channel some of their endowment activity away from Hindu institutions and into secular, British-style schools and colleges (Basu 1984).

In the twentieth century, the battle against Christianity became irrelevant, and members of the mercantile elite (including Nakarattar notables) forged an alliance with members of the provincial landed elite, transforming the educational movement for use in their political war against the nationalist Congress party. The chief architect of this political strategy was Raja Sir Annamalai.[21] Like many other members of the Madras elite, Annamalai participated in new colonial forms of endowment in addition to more traditional forms of religious gifting. By 1912, Annamalai's brother Ramaswamy had founded a secondary school and had built roads and sewage facilities in the important Hindu religious center of Chidambaram. In 1920, Annamalai used the secondary school as the basis for founding Sri Minakshi College.

Annamalai never lost his admiration for British education. But it was at just this time that elite Tamil values concerning education took on a noticeably different orientation. Early British policies designed to provide an education entirely in English were overthrown by growing regional and linguistic separatism as Indian politicians began to build and move into the emerging arena of provincial politics (Arooran 1980; Baker 1976; Irschick 1969). During the 1920s and 1930s, Tamil separatism and revitalization—the Tamil Renaissance as it came to be called—formed the ideological basis for the Justice party (in which Raja Sir Muthia played a central role) by portraying the rising National Congress party as a bunch of North Indian Brahmans, who would impose their regional interests, their Sanscritic culture, and—worst of all—their Hindi language on the out-numbered Tamils of South India. The Justice party preferred British rule to the threat of Congress party rule. The British, for their part, had other priorities than English education for Tamils. But they were happy to find loyalist allies and willing to help the cause of Tamil culture, especially when their help could be channeled through institutions such as colleges and universities that embodied British values, even without the English language.

The Tamil Renaissance was strengthened by the 1921 Montague-Chelmsford Reforms, which gave the increasingly Indianized provincial governments more legislative and revenue powers (Baker 1976; Seal 1973; Washbrook 1976). In 1927, the Madras ministry, under leadership of

Annamalai's political ally, Chief Minister P. Subbarayan, formed a committee to "investigate the need" for a Tamil university (Madras Mail , February 1, 1927, cited in Arooran 1980: 48). One week later, the Chief Minister spoke at the anniversary of Minakshi College, asserting, "When the time comes for founding a Tamil University, Sir Annamalai Nakarattar [he had not yet received the title "Raja"] will, I hope, develop ... a real residential unitary University. I hope that the Sri Minakshi College will develop not only as a college but also into a Sri Minakshi University at Chidambaram" (Madras Mail , February 8, 1927, quoted in Arooran 1980: 50). In 1928, the committee submitted a unanimous recommendation for establishing a Tamil university outside Madras City, with centers located at Madurai, Tirunelveli, Tiruchirappalli, Coimbatore, Kumbakonam, and Chidambaram (Madras Mail, March 31 and April 5, 1928, cited in Arooran 1980: 132–133). Simultaneously, Annamalai offered an endowment of Rs. 200,000 "in furtherance of the scheme of a unitary and residential University at Chidambaram" (Madras Mail , March 30, 1928, cited in Arooran 1980: 133). In August 1928, the Madras Legislative Council introduced a bill to establish a single teaching and residential university at Chidambaram (Government of Madras, G.O. 365, August 24, 1928). In the following December, the bill was passed in the Council and received assent from the Governor of Madras and the Viceroy of India (Government of Madras, G.O. 605, December 21, 1928). As passed, the bill matched Annamalai's endowment of Rs. 200,000 and promised a recurring annual grant of Rs. 15,000. The government later raised its initial grant with an additional contribution of Rs. 70,000 for the University's endowment (Government of Madras, Education Proceedings 1928–29: 39).

Annamalai's role in founding the university at Chidambaram paralleled exactly Kumarappan's role in founding the Palani pilgrimage, and he received the identical reward. The university itself was named Annamalai University in his honor. He was appointed Pro-Chancellor with overall managerial responsibilities for the university's considerable endowment. Ultimately, he received the coveted title "Raja Sir" for his role in the university's creation.

Economic Power, Elite Endowment, and Political Authority

It is difficult to uncover the complex dynamic between economic power, elite endowment, and political authority, for elite manipulations of political office—either in government or in religious and charitable institutions —are not normally part of the public record. Despite this difficulty, the private uses to which Raja Sirs Annamalai and Muthia put their power

and authority are very much alive in the rumors and reminiscences of South Indians living in Madras today, in some cases sixty years after the event. The following discussion, then, is based on hearsay.[22] But the events it describes were common knowledge among the political cognoscenti when I did my fieldwork, and I am reasonably confident about the truth of the following account. At the very least, it accurately reflects a general Nakarattar perception and, more importantly, a general Nakarattar attitude toward elite members of the caste.

To begin with, the underlying basis of the S. Rm. A. M. family's power in Madras was the control of major sources for large-scale credit in the city, the Presidency, and throughout South and Southeast Asia, and Annamalai's and Muthia's influence extended to the Indian Bank, the Imperial Bank, the Reserve Bank of India, and, in short, to most of the major sources for credit and financial exchange available to Indian businessmen. In fact, the S. Rm. A. M. family's control of these banks stimulated two non — S. Rm. A. M. Nakarattar families, Sr. M. Ct. Chidambaram and Kalimuthu Thiagarajan, to found the India Overseas Bank and the Bank of Madurai, respectively. In any case, and particularly in the case of the Indian Bank, controlled by the S. Rm. A. M. family from 1908 to 1969 (when it was nationalized), every loan made by the bank is said to have cost the borrower a clandestine 2 percent fee. The fee was paid to Raja Sir Muthia, either directly, in the form of "black money," or indirectly, in the form of "white money" donated to philanthropic endeavors associated with the family name and under the influence of family members serving on their boards of trustees.

One of my informants offered the following example of the way in which Annamalai and Muthia could use philanthropy to benefit from a "white money" donation to public charity. The Maharajah of Tranvancore was one of the first persons (if not the first) to open temples to harijans in 1936. In 1938, Rajagopalacharia, head of Congress and Chief Minister of the Madras Presidency, unveiled a statue of the Maharajah in the High Court compound in Madras City. Raja Annamalai wanted to build an even bigger statue of himself opposite the Maharajah's statue. He built or caused to be built a music academy, Raja Annamalai Mandram, as a contribution to the renaissance of Tamil culture. After his death, according to his wishes, Muthia erected Annamalai's statue in front of the Mandram. It is twice as tall as the Maharajah of Travancore's statue, which it faces. It is built on government land, leased to the Tamil Music Association for 99 years from 1942 for one rupee per year. It was built by donations from the general public, although a large portion of these were actually from other Nakarattars. Rumor has it that the donations constituted a portion of Muthia's

clandestine 2 percent fee on loans made in Madras between 1936 and 1942. The academy is rented to the public for musical events and other large functions for Rs. 1,000–2,000 per day. My impression is that the profits (gross income less maintenance costs) are controlled by Muthia.

Another example is provided by the operation of Annamalai University.[23] During the course of my fieldwork in 1981, I asked a Nakarattar, who had been employed by the institution, why Annamalai University was so frequently subject to strikes by faculty and students. He responded with what I first took to be an irrelevant story about its dental school. Apparently, government funds for all university construction projects were deposited in the Indian Bank. The dental school was no exception. Although construction funds were deposited in the Indian bank, they were not disbursed until new funds for another large project were received. Meanwhile, of course, the bank, owned by the S. Rm. A. M. family, made use of the dental school funds. In the context of my question, my informant's story implied that Raja Sir Muthia, as Pro-Chancellor of the University, had deliberately adopted policies that would anger the students and instigate the strike. The strike slowed down the process of construction and hence the process of disbursements. As with many of these stories, it is difficult to judge the truth of the allegation and impossible to prove. But it is undeniable that Muthia's positions in the university, the Indian Bank, and other governmental bodies were fraught with potential conflicts of interest.

If the exercise of philanthropy to and political authority over public institutions produced economic profits, it is also the case that economic power contributed, in return, to the exercise of political influence. In 1909, Annamalai formed the Southern India Chamber of Commerce—a lobbying organization that represented the rising interests of Indian businessmen in Madras. He and his family have controlled the chamber ever since. In this regard, it is significant to observe that it is members of the S. Rm. A. M. family who have actually headed the chamber for the longest periods of its history, and that it is Annamalai and Muthia who have headed the chamber during its celebrations of Silver and Golden Jubilee years.[24] By controlling the chamber, the S. Rm. A. M. family gained not only direct influence on the Madras Legislative Council, by control of the chamber's reserved seat, but also indirect influence, by control of other institutions that also had input on the Legislative Council and that directly affected every aspect of the economic life of Madras. Indeed, to this day, the Chamber—dominated by Raja Sir Muthia until his death in 1984—has representatives in the railroad, port trusts, Telephone Advisory Committee, universities, and various consumer advocacy bodies.

Control of the private social clubs of Madras City's elite was a further bulwark for S. Rm. A. M. family political and economic power. The institutions included the Madras Race Club, the Cricket Club of India, the Indian Hockey Federation, the Cosmopolitan Club, and the Gymkhana Club. In each of these sodalities, Annamalai and Muthia exercised control over membership. I gathered no information about the exact mechanisms of this control or about the kinds of social pressure that this control brought to bear upon the notables of Madras. But since these institutions largely constituted the interactional arena for Madras elite society, I assume the influence was considerable.

There were also direct benefits to be gained. For example, in the early 1930s, Muthia (who was then Mayor of Madras City) opened the Lady Willingdon Club, a recreational club for the one hundred elite ladies of the city (Willingdon had been Governor of Madras and was later Viceroy of India). Membership in the club was determined by a nominating committee controlled by the S. Rm. A. M. family. Annamalai and Muthia donated fifty acres of land to the club. The land, however, was half of one hundred acres of city land that Muthia, as mayor, had leased jointly to himself and his father at one rupee per year for ninety-nine years. Under the circumstances, and in the worthy cause of a social club named after his wife, Governor Willingdon naturally went along. Muthia retained control of the land until his death.

It is interesting to note that although the Lady Willingdon Club presently appears rather run-down, the other fifty acres are quite nicely kept up and contain various institutions, all ostensibly flowing from S. Rm. A. M. family largess. They include the Rani Meiyamma Club (named after Annamalai's wife), the Raja Annamalai building, housing offices for Air India and Indian Airways (since 1980), and an institute for research into Tamil, Sanskrit, and other Indian languages. As with Annamalai University and the Madras music academy, the Annamalai Mandram, one payoff of S. Rm. A. M. family philanthropy was an enhanced public image derived from naming public buildings after Raja Sir Annamalai. In addition, or so it was suggested to me, the S. Rm. A. M. family may have received other payoffs. In particular, it is questionable how much of the contributions for other developments on the leased one hundred acres came from S. Rm. A. M. family pockets, and how much came through skillful manipulation of still other public institutions. For example, in the case of the Raja Annamalai Building, two years' rent for the airline companies was taken in advance from the Government of India and deposited in the Indian Bank controlled by the S. Rm. A. M. family since the early decades of this century, on whose board Raja Sir Muthia sat until

1969, and over which he was rumored to have considerable influence until his death. The actual funds for construction came from an interest-paying loan from the Indian Bank. The advance rent given by the government was used as security. The total sum (roughly ten times the advance rent) was then paid to the raja's own contracting company, South India Corporation (one of the largest contractors in South India), which then built the Raja Annamalai Building.

The case of the Sanskrit Institute is more complicated yet. Beginning in 1966, in honor of Madras Governor K. K. Shah's interest in Sanskrit studies, Raja Sir Muthia manipulated various endowments over which he had influence to provide Rs. 500,000 as seed money to build the institute. Rumor has it that Muthia's payoff came in the form of government contracts by the grateful Shah to companies of Muthia's choice, especially his own Chettinad Cements. Muthia more than made back his philanthropic investment, which, in any case, had been carried out with ostensibly public money. As in the previous example, the essential point is the control of public resources (at local, provincial, and national levels) for private gain, and the use of social ties with political authorities over long periods of time (from Governor Lord Willingdon, who initially acquiesced in and sanctioned the leasing of city land, to Governor K. K. Shaw, who acquiesced in and sanctioned construction of the Sanskrit Institute).

The Historical Continuity of South Indian Mercantile Elites

Whatever the truth of these popular if (perhaps) apocryphal stories, they raise a number of questions about historical continuity in the commercial role of religious gifting and secular philanthropy. There is no denying the major changes that took place between the seventeenth and the twentieth centuries with respect to the social organization of political institutions and the cultural construction of political values. Yet dramatic disjunctures in South Indian politics mask an underlying continuity in South Indian commerce, particularly in the role of elite merchants, which integrates both domains of social action. Kumarappan, in the seventeenth century, and Raja Sirs Annamalai and Muthia, in the twentieth century, epitomize this continuing role of the mercantile elite over very long periods of South Indian history.

I do not mean to imply that all South Indian mercantile elites operated identically at all times and in all places. In the precolonial period, elite merchants acquired titles and offices such as "Salt Chetti." During the colonial period, they acquired titles and offices including Rao Bahadur, Zamindar, Raja, Mayor, and Minister. Other periods offered different

titles and offices. In addition, different historical periods provided alternative opportunities for participating in commercial, political, and religious institutions. There were different local and extralocal political forces subject to brokerage, different extralocal financial resources available for local use, and different extralocal markets for local producers. Finally, the resources and organization of an elite merchant's caste varied considerably, depending upon his identity as Nakarattar, Komati Chetti, Brahman, Mudaliar, Nadar, or Kaikkolar. Nevertheless, although the specific mix of ingredients for elitehood varied, the underlying structure of recognized leadership within caste or kin groups, political control of business-oriented local polities, powerful economic brokerage between local polities and extralocal authorities, and large-scale religious and charitable endowment remained constant.[25] Taken together, these qualities constituted structural prerequisites for trust (marravan nampikkai ) and trustworthiness (nanayam ), and these in turn constituted the moral basis of credit on which all mercantile activities were based. Indeed, the relationship between mercantile trustworthiness and economic power was reciprocal and functional. Religious gifting and secular philanthropy—far from constituting irrational expenditures for other-worldly ends—were investments in the conditions that made worldly commerce possible.

Plates

The plates in this book range from images of people to images of houses and temples to images of life-cycle ceremonies. They are drawn from a variety of sources, including Nakarattar publications and other documents of the colonial period as well as photographs of contemporary architecture and rituals.

The Public Image

Nakarattars were known to colonial society as archetypal merchant-bankers. Plate 1 portrays a Nakarattar banker in Colombo, a visage known by Nakarattar clients throughout India and Southeast Asia. Plates 2 and 3 show S. Rm. A. Muthia Chettiar, the most visible representative of the Nakarattar community to the colonial government, in two of his most prominent roles: in Plate 2 as Mayor of Madras (1932) and in Plate 3 as Minister for Education, Health and Local Administration (1936–37). See Chapter 7.

Plate 1.

A Nakarattar banker in Colombo (1925).

Reprinted from Weerasooria (1973)

by permission of Tisara Prakasakayo Ltd.

Plate 2.

Raja Sir Muthia as first Mayor of Madras (1932).

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 3.

Raja Sir Muthia as Minister for Education,

Health and Local Administration (1936).

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Political Constituencies of Raja Sir Muthia

As with Plates 2 and 3, Plates 4 through 8 are reproduced from the commemorative volume published for Raja Sir Muthia's sixtieth birthday celebration (shastiaptapurti kalyanam ), and date from the period before he received his knighthood and the title "Raja Sir." The photographs illustrate many of the Raja's political connections, discussed in Chapter 7: the Banking Enquiry Committee on which he served in 1929 (Plate 4), the Justice party upon his election as Chief Whip and Chairman in 1930 (Plate 5), prominent supporters from Karaikudi on the occasion of his election as Mayor of Madras in 1932 (Plate 6), members of the South India Chamber of Commerce in Madras, likewise posing with him at a reception in celebration of his election in 1932 (Plate 7), and finally, his father, Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar, with members of the Indo-Burma Chamber of Commerce in 1935 (Plate 8).

Plate 4.

Banking Enquiry Committee (1929); Raja Sir Muthia second from right.

Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 5.

South India League Federation (Justice Party) on Muthia's election as

Chief Whip and Chairman (1930). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 6.

Supporters from Karaikudi Municipality on Muthia's election as Mayor

of Madras (1932). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 7.

Supporters from South India Chamber of Commerce on Muthia's election

as Mayor of Madras (1932). Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 8.

Raja Sir Annamalai Chettiar (seated, right) in England with members

of the Indo-Burma Chamber of Commerce (1935). Reprinted from Annamalai

University (1965).

Houses

The hybrid Anglo-Indian political style reflected in colonial dress and title are also reflected in the magnificent vernacular architecture of Chettinad. This style is illustrated in the increasingly elaborate Nakarattar versions of the Anglo-Indian bungalow, aptly described as "country forts" (nattukottai ). Chapter 6 draws attention to the valavu (the central courtyard, surrounding corridor, and double rooms for pullis or conjugal families) from which many Nakarattars derive the name for their joint families. A floor plan for a relatively simple Nakarattar house (Plate 9) illustrates this feature along with an outside veranda for guests in the front of the house, a small courtyard in back for cooking, and a separate room for women "polluted" by various life-cycle crises.

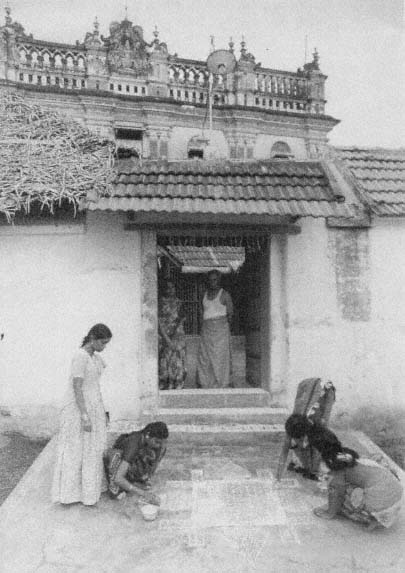

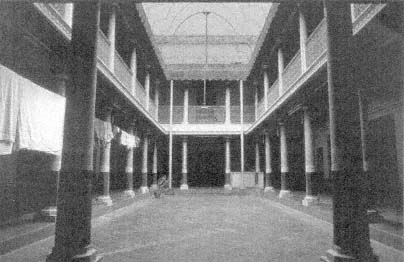

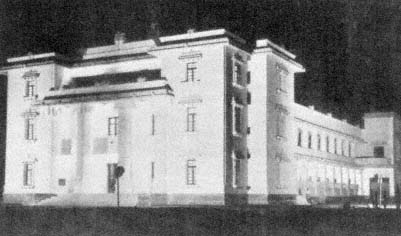

All Nakarattar houses share this division into a front "male" section, a central ceremonial section, and a rear "female" section. From the last quarter of the nineteenth century on, however, Nakarattars elaborated on this common theme, adding on extra rooms around the central core and incorporating a variety of colonial architectural motifs, ranging from Mughal-inspired towers to niches with sculptures of Queen Victoria. Such elaborations are depicted in the floor plan of a more elaborated Nakarattar house (Plate 10) and in the following four photographs of Nakarattar houses. Plate 11 captures the facade from a relatively simple Nakarattar house in Attankudi. Plate 12 shows the daily activity of Nakarattar women drawing a kolam (auspicious design) in the street before the front entrance to their house. Plate 13 is reproduced from Raja Sir Muthia's sixtieth birthday celebration commemorative volume and shows his highly elaborate Chettinad "Palace." Plate 14 captures a detail from a gateway to the palace in which the demon devotees of Lakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth, have been replaced by British soldiers. Plate 15 shows the central courtyard in the Chettinad Palace's elaborate two-storied variant of the Nakarattar house. Further analysis and photographs of Nakarattar houses may be found in Palaniappan (1989) and Thiagarajan (1983, 1992).

Front (Male) Section of House

1. Veranda.

Central, Ceremonial Section of House

2. Hal vitu or vitu: first courtyard; literally, "hall house."

3. Tontu: columns.

4. Melpati, tinnai: a raised platform on which people sit, usually under the veranda or on either side of the door of the house.

5. Valavu: aisle or corridor surrounding central courtyard; central section of house including central courtyard, aisle, and inner and outer rooms; entire house.

6. Ull arai: pulli's inner room for puja and storage of dowry items.

7. Veli arai: pulli's outer, "conjugal" room.

Kirpati: raised sitting platforms in front of each arai (not shown).

Back (Female) Section of House

8. Kattu: second courtyard, women's courtyard; where grains are dried, foods are prepared, and water is stored.

9. Samayal arai: kitchen.

10. Kutchin: a small room for women during their menses and for girls during their coming-of-age ceremony.

11. Veranda.

12. Pin kattu: open garden space with or without well.

Tottam: garden (not shown).

Kenru, keni: well (not shown).

Plate 9.

Plan of ground floor of a "simple" Nakarattar house.

Source : Thiagarajan (1983).

Front (Male) Section of House

1. Munn arai: front room.

2. Murram: courtyard.

3. Talvaram: corridor.

Central, Ceremonial Section of House

4. Kalyana kottakai: marriage hall.

5. Patakasalai, tinnai: the "public" room in a house.

6. Bhojana salai: dining hall.

7. Veliarai: outer room.

8. Ullarai: inner room.

9. Irantam maiya arai: second central hall.

10. Murram: courtyard, roofed or covered with grill work.

Back (Female) Section of House

11. Murram: courtyard, roofed or covered with grill work.

12. Talvaram: corridor.

13. Kalanjiyam: store room.

14. Samaiyal arai: kitchen ("cooking room").

15. Pin kattu: backyard.

16. Keni: well.

Plate 10.

Plan of ground floor of an "elaborate" Nakarattar house.

Source: Palaniappan (1989).

Plate 11.

Nakarattar house, Athankudi. Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 12.

Women drawing kolam (auspicious design) in front of Nakarattar house.

Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 13.

Raja Sir Muthia's "Palace" in Chettinad. Reprinted from Annamalai University (1965).

Plate 14.

Detail of gateway to Chettinad Palace, showing Lakshmi and British "Guardians."

Photo by Peter Nabokov.

Plate 15.

Interior courtyard of Chettinad Palace. Photo by Peter Nabokov.

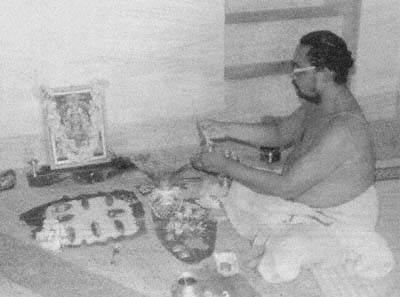

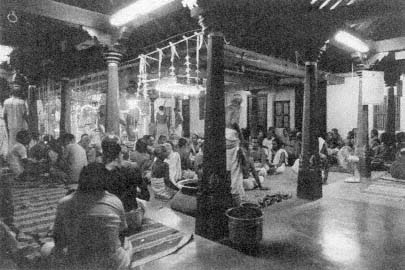

Temples and Charitable Endowments

Nakarattar house construction in Chettinad shares much in common with house construction in other parts of South India (see, e.g., Daniel 1984, Moore 1990) and indeed with other architectural forms—most notably, temples. All such forms are influenced in varying degrees by a complex set of iconic architectural principles based on Hindu religious ideas about cosmic creation, sacrifice, and regeneration (cf. Beck 1976b; Daniel 1984; Kramrisch 1946; Meister 1983, 1986; Michell 1988; Moore 1990; Varahamihira 1869–74: Chs. 53, 56). The central idea is that properly designed buildings (kattitam: literally, "bounded spaces") represent an image of the personified Hindu universe in microcosm: creation spreading outward toward the eight cardinal directions from a central point where formless divinity is manifest, worshiped, and celebrated in ritual. The center/periphery contrast already noted for Nakarattar houses constitutes only a specific version of this core theme, which is expressed most dramatically in the relationship between the sanctum of the temple (Sk: garbagrihya , Tm: karpakkirikam: literally, "womb room") and its outer walls (cf. Meister 1986).