Epitaph: Cenotaph: Epigraph

Thel future can give an ironic tone to/ the sentence.

—Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp's dismantling of the hegemony of vision in Given , as indexical and institutional givens, resituates the position of the artist. By questioning the criteria defining the construction of the visible, Duchamp challenges the immortality of both the work of art and the artist as sanctioned by the museum. In Given this visual immortalization no longer supplants the mortality of the artist by substituting itself for it. Echoing Duchamp's

statement that "men are mortal, pictures too" (DMD , 67), Given stages the shared mortality of the artist and the artifact. In doing so it destabilizes both the authorial persona and the work: it delays them both by encrypting them in a snapshot, postponing life and death in the illusory temporality of the future-perfect. It is this postponement of pictorial and artistic intent that opens up Duchamp's works to future forms of artistic appropriation, anticipating the developments of postmodernism.

Arturo Schwarz describes Duchamp's death in the same terms that he used to describe his life, as an unannounced, informal departure:

The following morning I found him on his bed, fully dressed, and wearing his favorite tie. Beautiful, noble, serene. Only slightly paler than usual. A thin smile on his lips. He looked happy to have played his last trick on life by taking a French leave. No better ending to no better life. His last masterpiece.[47]

Duchamp's "departure" is presented as being consistent with his life, a French leave that evacuates the drama of death by its informal character. This "departure," which Schwarz assimilates too readily to the reality of a work of art (as Duchamp's last "masterpiece"), marks the accidental confluence of life and death of an artist whose focus had been the mortality of both art and artist.

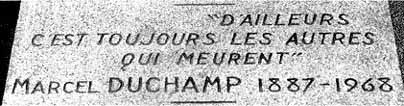

Anticipating the desire for canonization that haunts the fate of the artist as a historical character, Duchamp explicitly questions the necessity of such fictions: "The idea of the great star comes directly from a sort of inflation of small anecdotes. It was the same in the past. It's not enough that two centuries later we have to look at certain people as if they were in a museum, the entire thing is based on a made-up history" (DMD , 104). For Duchamp, the effort to canonize historical figures amounts to the "inflation of small anecdotes" in a process corresponding to museumification. It is exactly this process of mummification that Duchamp actively resisted, both in his life and in his works. As if anticipating this desire, Duchamp plays one last joke on the spectator with his epitaph: "and besides/ it's only the others that die" (fig. 86). Engraved on his tombstone, this statement affirms the fact of death as an impossible experience. Impossible, if only because we can only witness the death of

another and not our own. Duchamp's epitaph haunts the spectator by evoking, through our utterance of it, Duchamp's lifelike presence. Although it may be construed as a denial of death, this statement challenges the facticity of both life and death as fundamental givens. This epitaph ironically recasts the relation between life and death, engraving the shadow of life into the traces of death. Duchamp's death is notorized, as it were, by his testamentary statement. Like François Villon's literary testament, Duchamp's epitaph casts a retrospective light on a grave whose significance is defined not by how one dies but by how one lives.[48] Duchamp's humorous epitaph derealizes the gravity of death by suggesting that its reality is no less subject to humor than life itself.

Duchamp's epitaph points to another cenotaph—Given —the lifelike assemblage of the immortal mannequin simulating life in the artificial confines of the museum (the "cemetery" of visual artifacts). If Given holds its viewer at a fixed distance, this distance becomes both the interval and the delay marking the separation and/or continuity of life and death. It is the last "hinge," the sign of "Life on credit" (Notes , 289), to use Duchamp's own words. Given , an apparent "snapshot" of life, is engraved with the imprint of its negative, of death obversely reiterating its outline. Within it is inscribed the figure of the artist in movement, the double signature Rrose Sélavy , alias Belle Haleine : Eau de Voilette , androgynous embodiments of the art of "heavy breathing."[49] Delayed in the interval between these signatures, Duchamp "breathes," he lives (Sélavy or c'est la vie ) not as himself but as an alias, ready-made for a rendez-vous with the spectator.

So how does one take leave from Marcel Duchamp? Duchamp's comment about his own taking leave from his dying friends Francis Picabia and Edgard Varése (1883–1965) provides a humorous, yet poignant reminder. His response to Pierre Cabanne captures with ironic simplicity his recognition of both the pathos and the reality of death:

Duchamp: It's hard to write to a dying friend. One doesn't know what to say. You have to get around the difficulty with a joke. Good-bye, right?

Cabanne: You cabled, "Dear Francis, see you soon."

Duchamp: Yes, "see you soon." That's even better. I did the same

thing for Edgard Varèse, when he died a few months ago . . . . So I simply sent, "See you soon!" It's the only way of getting out of it. If you make a panegyric it's ridiculous. Everyone isn't a Bossuet. (DMD , 87)

Thus we take leave of Marcel Duchamp, without a panegyric, like an old friend in whose honor we send our own telegram "Dear Marcel, see you soon!"

Fig. 86.

"And besides/ it's only the others that die" ("D'ailleurs c'est toujours les autres

qui meurent"). Epitaph on Marcel Duchamp's tombstone in the cemetery in Rouen.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In conclusion, Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas , Duchamp's testamentary installation, emerges as an assemblage, the living corpus of his previous works. Despite its figurative character, its gross naturalism, and its staged voyeurism, this work posthumously exhibited to the public functions as a testamentary work insofar as it is a compendium that references his previous works. It embraces the trajectory of the nude as a pictorial genre from its earliest embodiments in Nude Descending a Staircase , through its passage in The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass ), and its fragmentary reembodiments in such sculptural works as Female Fig Leaf and Wedge of Chastity . Just as The Large Glass reproduces and transposes his previous pictorial works on glass, so does Given restage artistic conventions by reproducing and literalizing them through their exaggerated realism. This corpus cannot be assimilated to a corpse, since what is dead and rendered obsolete in this installation is the spectator's gaze. The obscenity of the spread-eagled nude lies less in its outward appearance than in the fact that it deliberately

stages the spectator's look as an apparatus of display. The violence of the nude concerns less the way it looks than the violence that is made explicit by the pictorial history of the gaze as a mode of objectification.

If painting was stripped bare and rendered transparent in The Large Glass , in Given the nude, as the subject matter of painting, returns with the dead-weight literalness and opacity of an object whose density incarnates the figurative conventions of classical painting. The nude as subject matter of painting thus emerges as a reflection on the matter of painting, restaging the rules that define its specificity as a genre. By literalizing the mimetic impulses of painting in a three-dimensional installation, Duchamp dismantles its generic specificity by its affiliation and contextualization through other media, such as photography, sculpture, and language. Thus the reliance on painting as a medium for reproduction becomes the stage for enacting through literal reproduction the possibility of its demise. The simulational logic of Given restages the conventions that define art in order to generate objects that are the obverse of readymades. Whereas the ready-mades look like ordinary objects that are redefined as art, the landscape and nude in Given look like art in a grossly exaggerated sense only to challenge its conditions of possibility. While the ready-made is the perfect copy of an object because it is the object itself, the objects in Given are literal renderings of conceptual prototypes—they are projections of the rules governing pictorial mimesis. In both of these cases Duchamp uses reproduction as a way of expropriating objects of their visual appearance through a strategy of redundancy and repetition whose logic is akin to puns. By literalizing the figurative ambitions of painting, either by generating perfect copies or perfecting its conceptual prototypes, Duchamp brings painting face to face with its conditions of possibility. While The Large Glass brought painting into the realm of transparency by drying out conceptually its pictorial intent, Given returns to notions of figurality as a rhetorical projection of painting, which makes tangible its otherwise invisible conventions.

If The Large Glass held a mirror up to painting by reifying its visual appearance, that is, by reducing the spectator's gaze to gas, then Given recondenses the gaze, making visible its material properties. The water and gas alluded to in the subtitle of Given suggest Duchamp's intervention, his recondensation of the spectator's gaze. Just as The Large Glass

unpacked through its transparency pictorial appearance, so does Given unpack the spectator's look as a ready-made, or given of pictorial conventions. Whether it is a question of challenging pictoriality through the logic of the ready-made, or of returning to figurality as a way of uncovering its ready-made character as a given, Duchamp persists in questioning and challenging the limits of the pictorial as a system of representation. Duchamp's originality consists in the discovery that the way out of painting does not involve the movement from figuration into abstraction, since such a move would still preserve the material properties of the pictorial medium. Rather, finding a way out of painting means reframing it in the mode of reproduction, a strategy where the figural emerges as a rhetorical condition of painting dispossessed of its outward appearance. Staging its complicity with the viewer's gaze, with painting understood in the mode of a peep show, Given as an installation disassembles and reassembles the gaze, freeing it from its constraints by delaying its impact. Recontextualizing painting through its generic crossover into other media, Duchamp de-essenrializes the referentiality of gender, and by extension, that of art. In so doing, he once again reactives the interval that separates art from nonart.