13

The Syncretic Compromise

The Yaqui and Mayo Pascola

I was once told by an elderly pascola that the patron of all pascolas was Jesus Christ, and that for this reason pascolas wore loincloths and went barechested just as He did at the crucifixion. . . . Another dancer stated that all pascolas were goats, and mentioned that the flaps on the back of the loincloths were the hair on the animals' flanks. In addition, some Yaquis believe that the original pascola came from the devil and was persuaded to remain in the service of God.[1]

This statement indicates a significant difference between the pascola masks and dancers of the Yaqui and Mayo of northwest Mexico and the southwestern United States and the tigre masks and dancers of central and southern Mesoamerica in their relationship to pre—Hispanic forms and symbols. The roots of the tigre are clearly pre-Columbian, even though that mask and character may at times be found involved in syncretic ritual, but the pascola's heritage is not so easily determined, in part because of the problems involved in ascertaining the exact relationship between the cultures that lived on the fringes of Mesoamerican civilization and those of Mesoamerica proper. It is generally felt by Mesoamericanists, though it cannot be conclusively demonstrated, that the masked dance found in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico, along with other ceremonial forms and paraphernalia, diffused from Mesoamerica proper accompanying trade, probably during or immediately after the period of Toltec hegemony.[2] But the precise source of the pascola's indigenous traits has been difficult to determine.

A greater source of difficulty arises from the degree to which both mask and ritual exhibit the effects of the syncretic fusion of Christian and indigenous traits. The distinctive mask bears both Christian and indigenous symbols, and the ritual in which the masked dancer is involved gives him a bewildering array of roles. He is, perhaps primarily, a ceremonial host whose function is to involve the audience and guide its experience of the sacred during the course of a particular type of indigenous ritual, but he is also a clown, deeply involved in the carnivalesque inversion of values which may very well have medieval Christian roots and all of the fertility implications we have seen in the Oaxacan tejorones. Third, he is an actor, taking part in "skits" with fertility-related themes which often involve the deer dancer, as well as playing a role in the monumental Christian drama of Lent. Finally, he is a dancer whose dances are a fundamental part of the indigenous ritual he hosts.

Perhaps these difficulties arising from the pascola's cloudy origins and numerous roles might be mitigated by understanding how the Yaqui and Mayo have been able to create a viable religion from the fundamentally opposed Christian and pre-Columbian traditions of spiritual thought and practice which constitute their heritage. As we shall see, that "new" syncretic religion has a number of fundamental features directly traceable to pre-Columbian antecedents, chief among them the use of the mask as a central metaphor for the relationship between spirit and matter, between man and the gods—or God. That pre-Columbian metaphor and the view of reality it communicates has survived intact in a new context that is nominally Christian, but a Christianity reworked to fit indigenous patterns of thought. Edward Spicer suggests the syncretic nature of that reworked Christianity in the conclusion to his argument that it is a "new religion." He says, "We may sum the matter up without going into the meaning deeply by pointing out merely that a Pascola dance is required at each of the important devotions on the Christian Calendar."[3]

It is clear to Spicer, and equally clear to us, that the masked pascola dancer of the Yaqui and Mayo[4] unites in his dedication, in his movements, and in his mask and costume the two traditions that have shaped the world view and ceremonial life of all of the indigenous peoples of modern Mesoamerica. Indeed, the pascola is the clearest example of the particular way in which the Yaquis and Mayos have fused the Christian and indigenous traditions in their ceremonial lives, an important fact because it is through those ceremonial lives that the Yaquis identify themselves as Yaquis and the Mayos as Mayos.[5] That sense of identity is often related specifically to the symbolic pascola. According to N. Ross Crumrine, for example, the Mayo believe that "the paskolam are the best of all Mayos because they are the most characteristically Mayo in their behavior and speech, always praying and giving hinakabam [ritual speech] in Mayo and participating in church processions."[6] Similarly, Spicer indicates that in the Arizona Yaqui village of Pascua in the 1930s the pascolas were seen by some as "the most distinctive of Yaqui institutions"; he quotes a maestro as saying, "Wherever you have pascolas, there you have Yaquis."[7] Their symbolic importance to the cultures in which they are found and the clear sense within those cultures that they demonstrate a syncretic fusion of Christian and native spiritual traditions makes them an excellent example for us of the way the tradition of Mesoamerican spiritual thought has fused with European Christianity in masked ritual—and a particularly fascinating one since they exemplify the continuing importance of the mask as a powerful central metaphor for the spiritual foundation of material life.

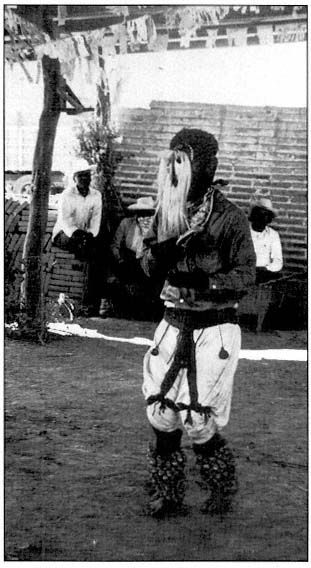

The pascola's syncretic nature can be seen in the way a Mayo or Yaqui becomes one who "dances pascola " (pl. 65) and wears the characteristic mask (pls. 66, 67). While "any adult male Yaqui [or Mayo] can become a pascola,"[8] often as the result of a youthful fascination leading to apprenticeship to a practicing pascola, such a prosaic description obscures another set of beliefs widely held by Yaquis and Mayos. Among the Mayo, although it is

denied by individual practicing paskolam, the recruitment of paskolam is said to take place as a result of a supernatural experience in which a paskola visits a cave in the mountains and talks to an old man with a white beard. The paskola is sometimes said to sell his soul to the old man in exchange for the power to dance well. . . . Paskolam, when they die, are almost universally believed to go and live in the mountains or forest with this old man. The paskola, closely acquainted with the animals of the forest, may see the otherwise invisible huya ania (sacred forest) and such sacred animals as deer, pigs, and goats. The commander of the huya ania may take the form of one of these animals who are his children.[ 9]

Pl. 65.

Mayo Pascola dancer, La Playa, Sinaloa (photograph taken

with permission by James S. Griffith, reproduced with his permission).

The Yaqui have a similar belief:

There is . . . a strong connection between the pascola arts and a mystic region called the yo ania, or the enchanted land. The yo ania is a region that lies within the hills and can be entered through caves. It is a dangerous place, and although pascola skills may be learned through contact with it, one does so at the risk of one's soul. Closely associated with the yo ania are several animals including a large goat and a snake. Both of these appear in the power dreams through which a boy can learn that he is to become a pascola.[10]

Thus, both Yaqui and Mayo believe, metaphorically at least, that the pascola dances as the result of a "calling" originating in a world of the spirit,

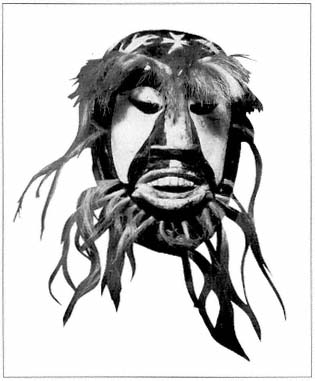

Pl. 66.

Yaqui Pascola mask, Pimientos, Sonora

(collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

which, while quite different from that generally imagined by Christians, has a number of Christian overtones. Composed of several aspects, the spiritual realm of the Yaqui and Mayo has proved difficult for scholars to understand fully as it exists in an essentially oral tradition that has been in a state of flux for hundreds of years as a result of its gradual syncretic "accommodation" of, or to, Christian views.

The precise relationship between the concepts of the yo ania and the huya ania, for example, is not clear although we can discover a basic distinction. For both Yaqui and Mayo, the term huya ania refers to what we would call the natural environment surrounding areas of human habitation, but while we think of nature as material, "the spiritual conceptions of Yaquis regarding the yo ania and wisdom derivable by learning about it are not consistent with the purely material view of nature, rooted in medieval Christianity, taught in schools and underlying the Western conception." From the indigenous perspective, "incorporeality" rather than materiality is "the very essence of the huya ania ." And that incorporeal essence, in Spicer's view, is the yo ania, a "power suffused through the huya ania ." [11] Looked at in another way, the yo ania is the "rich poetic and spiritual and human dimension of the area surrounding the Yaqui villages."[12] Within this realm lies the source of the pascola's power to manifest the sacred, and as the quotations from Crumrine and Griffith and Molina cited above both suggest, there is an ambivalence within Yaqui and Mayo thought as to whether the nature of that source and the spiritual power it can grant is good or evil.

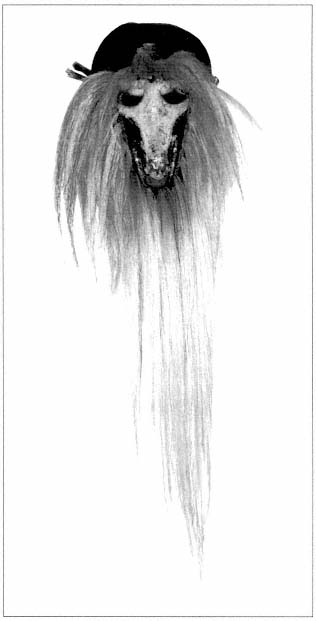

Pl. 67.

Yaqui Pascola mask, Pimientos, Sonora, detail.

That ambivalence probably results from the fusion of indigenous and Christian beliefs as it is likely that the initial impetus to link the spiritual power of the pascola to the devil came from the Jesuit priests who ministered to the Yaquis for 150 years after the Conquest. The Christian overtones are striking: the yo ania is imagined underground, presided over by a lord to whom one can sell his soul for earthly power,[13] and inhabited by animal spirits such as snakes and goats traditionally associated with the Christian devil. But these animal spirits are not necessarily evil; side by side with this Christian view that leagues the pascola with the devil, the Yaqui and Mayo have also retained what must surely be the pre-Hispanic idea of the yo ania.[14] Beals, in his early research among them, found that "the pascola dancer, in no sense and at no time appears to have any association with evil, even when masked, despite his connection with the woods."[15] The terms of that "connection" are clear: the power of the pascola "derives directly from the beings of the huya ania ."[16] These beings appear in animal form to men in dreams or "in something more properly describable as a vision. . . . There was, for example, a conception of a mountain sheep who gave dance power to a human Pascola ." But this was not a natural animal; "perhaps it was the essence of all mountain sheep."[17]

The denizens of the huya ania who confer power on the pascola are thus connected either with the devil or the essence, or life-force, of living things in the world of nature. While these two views—Christian and indigenous—are contradictory in moral terms, they are congruent in other, more important, ways. Both view the huya ania as the repository of essential power, and both see the

masked pascola as the agent through whom that power enters the human world. Fundamentally, this is the classic pre-Columbian view of spiritual reality described in Part II, despite its incorporation of Christian elements. Essential reality is still seen as spiritual and as "hidden" or "inner," and the unique mask of the pascola still functions, as masks always have in Mesoamerica, as a metaphor for the way in which that spirit can be brought into this world.

That the Yaqui and Mayo, as cultures and at times individually, can see this spiritual power that animates the pascola as both good and evil, that is, from both Christian and indigenous standpoints simultaneously, is not a measure of their ingenuity but an indication of the reformulation of the Christian hell and devil in indigenous terms. While Christianity defines the devil as the principle of evil, an abstract conception associated always with the separation of man and nature from God, the tendency among the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica has been to associate the devil with powerful natural forces—sexuality and violence, primarily—that can disrupt the order on which human culture rests. The problem, then, is not to "overcome" the "evil" power of the devil but to harness it. The "devilish" forces must be harmonized with the demands of human culture through ritual; their destruction, if even conceivable, would be unthinkable as they are the very forces that, when controlled, sustain human life. The pascola, and other masked ritualists, are engaged in that dangerous but vital task of ritual control.

In this sense, these rituals and the masked ritualists who participate in them are really forces for "good," and it is fascinating that among the Yaqui of Arizona, for example, Spicer has identified a process, which he calls "sanctification," that is gradually reformulating the vital power of the huya ania in Christian terms—but as good rather than evil.[18] This process can be seen particularly clearly in the case of the pascola[19] due to "the irrelevance of the [pascola's fundamental] animal associations to the present ceremonial system."[20] By the 1930s, Spicer found "some association" between the pascola and Jesus,[21] an association referred to in the quotation with which we began this chapter. As he points out, a Yaqui "does not become a pascola as a result of a manda, or promise, to any deity, [and] thus there is no patron of the pascolas " such as exists for the other masked dancers, such as the matachini or fariseos , who participate in Yaqui and Mayo ritual. Nonetheless, individual Pascuans frequently said "that Jesus is the patron of the pascolas. "[22] And this linkage of the pascolas to Jesus can also be found among the Mayo who, according to Crumrine, believe that pascolas were present at the birth of Christ,[23] a thinly veiled historical reference, perhaps, to the existence of the indigenous religion before the Conquest.

A further step in this process of sanctification may be seen in an aspect of the huya ania referred to in the songs that accompany the deer dancer, an aspect called the sea ania , or "flower world," which has come to be seen by some Yaquis as opposed to the yo ania. For them, "the sea ania has become aligned with Christ and Heaven, the yo ania has become associated with the Devil and Hell."[24] But this seems to be a recent development; earlier, Spicer found a different conception. In the deer songs, "one frequently mentioned, now mysterious, place . . . is called seya wailo, which is not translatable by 20th-century Yaquis, but which they generally agree probably has some reference to a place of flowers." In this connection, he notes that seataka, a term used to denote the huya aniaderived power of the deer and pascola dancers also refers to flowers. And, he continues,

there is a further and curious meaning of flowers among Yaquis which appears, perhaps through recent reworking, to link all the important realms of meaning into a single one. Twentieth-century Yaquis sometimes give as the primary meaning of sewa, "grace of God." They hold that flowers are symbolic of grace, because when blood fell from Christ's wound to the ground, flowers grew on the spot.[25]

Thus, the pre-Columbian symbol par excellence of the life-force-blood-has come, among the Yaqui and Mayo, to be seen as equivalent to the symbol for the comparable Christian conception. God's grace, symbolized here by flowers, the mysterious force that enables human life to continue, is metaphorically nourished by the sacrificial blood of Christ, and the flower is the symbol of the sustaining quality of that sacrificial blood and provides the root metaphor for the domain of the world of the spirit to which the pascolas and other ritual dancers are being assimilated. Their dance is conceived as the necessary ritual action that enables "God's grace" to move from the world of the spirit to man's world; the fundamental pre-Hispanic relationship between man and the world of the spirit on which it depends has not changed but is now being given a Christian rationale.

Changes in Yaqui society have made this reformulation of the mythic relationship between the pascola and the now widely accepted Christian view of the world of the spirit necessary. As long as the indigenous conception of the huya ania retained a standing equal to the Christian conception of the world of the spirit, Yaqui and Mayo spiritual thought could accommodate an association of the pascolas with the devil as their simultaneous connection with the huya ania provided a sufficient basis for their profoundly sacred nature. As late as the 1950s there was still "unquestionably a certain

sacredness for some of the older men" attached to the deer and pascola ritual due to "their relation to the persistent, aboriginal non-Christian stream of tradition in Yaqui culture, [26] a source of sacredness particularly clear in the still earlier ideas of a resident of Pascua:

The pascolas and the deer-dancer have the power of all kinds of animals; they get this power, according to myth, from streams of water in the mountains or out in the country somewhere. Each pascola does not get it there now, but that is where it came from originally. . . . This is different from the matachini and fariseos. They are connected not with animals but with the Virgin and Jesus. . . . But, nevertheless , [the pascolas]. . . are part of "our religion," too.[ 27]

Nothing could demonstrate the vital importance of the masked pascola to contemporary Yaqui and Mayo spiritual thought and ritual practice, that is, "our religion," more clearly than the fact that rather than being discarded as outmoded, the pascola ritual action is being given a new, "sanctified" mythic foundation and that still today pascola dancers "always play a significant role in processions and are felt to be an integral part of almost every religious ceremony in the Mayo valley. [28] But an understanding of the full significance of the pascola's ritual importance and his ability to link the indigenous and Christian strands from which Yaqui and Mayo religion are woven requires a recognition of two very different, and in some senses opposed, types of Yaqui and Mayo ritual, one rooted in the Christianity brought by the Conquest, the other growing from the indigenous past. The ritual most clearly Christian is centered on the church, which "in Yaqui [and Mayo] thought is the residence of Jesus and of Mary and of the saints" and the focal point of community-wide ritual. It is linked "through ceremonial labor" to "every household in the community," and these households replicate, in their physical plan and, more important, in their ritual functions, the structure and function of the church. That ceremonial life of the household takes place in the context of the pahko and contains a number of clearly indigenous elements.

While pahko is generally translated as "fiesta," Spicer feels it is more precisely defined as a "joint religious ceremony" uniting church and household,[29] a unity apparent in the physical structure housing the household ritual and in the ritual itself. To give a pahko, a household must construct a ramada, called the pahko rama, which is divided into two sections, one of which has a table that will serve temporarily as an altar to hold the santos brought from the church for the occasion while the other is prepared for the pascolas and the deer dancer, if there is to be one. Thus, half the pahko rama will be devoted to church-based ritual brought to the household and the other half to the huya ania-related ritual of the pascolas. The pahko rama unites the indigenous with the Christian under a single roof but carefully distinguishes one from the other.

Similar care is taken in the ritual activity that begins with the formal procession of the "church group," perhaps including matachin dancers, from the church to the pahko rama. There they are ritually welcomed and directed to the "altar" on which they place the santos and which they arrange for their devotions during the night. These devotions will be performed simultaneously with the pascola activities taking place in the other section of the pahko rama. It is no doubt significant that the two types of ritual activities are not synchronized but proceed as if each were the only activity taking place. Again, the two strands of ritual are brought together but kept separate. In fact, "formal structuring is maintained during rests as well as when the ceremonial labor is being performed"; there is no mingling even then of church-related with huya ania-related ritualists. When the nightlong ritual activity has been completed, the church group formally takes its leave and marches "in formal procession back to the church" carrying the santos.[30]

The pahko's uniting of church and household while keeping the indigenous distinct from the Christian is significant to an understanding of the pascola because his primary ritual activity occurs in the indigenous ritual of the pahko, and it is on that base that his other ritual activities are built. The depth of the relationship between pascola and pahko becomes clear when one realizes that the term pascola is derived from pahko'ola , which literally means "old man of the pahko" and refers directly to what must be the aboriginal role of the pascola as the ceremonial host during the pahko who must ensure the meaningful involvement in the ritual activities of those attending. The crucial importance of this role is apparent in the almost mystic value attached in Yaqui thought to the participation of all community members, collectively known as the pweplum , "out to the last one," in all political, social, economic, and ceremonial matters. Similarly, the Mayo "argue that one must repeatedly see what is done in a given ceremony 'with his or her own eyes.'"[31]

In its aboriginal formulation, the function of the masked pascola must have been to bring his intensely personal experience of the world of the spirit to his community through ritual activity, which, though it might be seen as the individual activity of the ritualist by outside observers, was defined by the Yaqui and Mayo themselves as essentially communal. Even today it is felt that "the sacred chants and dances would have no significance if they were not attended to and witnessed to by the townsmen in general."[32] The pascola's ritual activity thus takes place at the conceptual

interface between man, as represented by the community of communicants, the pweplum, and the world of the spirit, which his visionary experience enables him to bring to the pahko. In the classic fashion of the shamanistic spiritual tradition of which he is a part, the pascola journeys to the world of the spirit in the service of his people, and as we have seen in our consideration of Mesoamerican ritual practice, that journey across the interface of matter and spirit is metaphorically represented by the mask, which allows inner spiritual reality to be made "outer" and thus available to the community; were that spiritual reality not so manifested, it would have no reason to exist. This shamanistic conception of the relationship between man and the world of the spirit is, perhaps, the reason that "the fundamental orientation of Catholic Christianity, namely, salvation of the individual soul and the objective of heaven had not been incorporated into the ceremonial system."[33] The masked pascola's concern is communal rather than individual, and in his role as ceremonial host and clown, he serves the most basic spiritual needs of the Yaqui and Mayo people, as they define them. Steven Lutes, an anthropologist who himself "danced pascola," explains the goal of this service.

The final personal goal at a fiesta is to emerge with a stronger heart and soul, something that happens during a special state of being, induced by all the forces of the fiesta taken together. Both the people and the community as a whole should go from the fiesta with renewed and bolstered power to lead their lives as their lives should be led.[34]

But the pascola not only serves as host and clown; he also dances. Through an examination of his function in that role, we can begin to understand the structure of pahko ritual and see how that structure is fundamentally involved in bringing the community into communion with the world of the spirit. The pascola's dances are a fundamental part of the complex structure through which the pahko achieves this essentially spiritual goal. Part of that structuring grows from the interplay between the deer dancer, when he is present, and the pascolas. While the ritual clowning of the pascolas with the audience provides one emotional level of the fiesta experience, the intensity and seriousness of the deer dancer, who does not even speak much less interact with the audience, "suggests the mysteries of a difficult and compelling discipline, as it somehow lifts viewers with dancer to a sense of repose through its very intensity of movement," a "sense of repose" that "transports" the audience "from the human world into the yo ania."[35]

Larry Evers and Felipe Molina describe the complex interplay between pascola and deer dancer, between clowning and seriousness, between lighthearted banter and silent, sacred intensity as creating a "pace" for the pahko which is "oceanic, ebbing and cresting throughout the long night,"[36] but, as they realize, the pascola's ebb is no less necessary, and no less sacred in the totality of the pahko, than the deer dancer's crest. Thus, pascola and deer, while they may seem to be working at cross-purposes on different emotional levels, are integral parts of the pahko as a whole, united in the psychologically complex nightlong sequence of events that serves to manipulate the audience's experience of the sacred in order to renew in them their essentially spiritual power "to lead their lives as their lives should be led."

Even more fundamental to the achievement of that goal than the structuring provided by the contrast between deer and pascola is the sequential ordering of the stages of the pahko experience which suggests both the pahko's meaning and its purpose. It is divided "into three distinct phases: one from the opening until 'when the world turns' at midnight, one from midnight till dawn, and one from dawn until the close of the fiesta,"[37] and it is "the order of dancing and the kind of dancing .. prescribed" for the pascolas[38] which most clearly marks that tripartite division, a division as clear to the audience's ears as its eyes since "the tonal classifications of Yaqui music fall into three separate melody types. Each is reserved for the appropriate period of the all-night ceremonies—evening, midnight, and dawn—and each accompanies particular dance patterns."[39]

In the beginning stage of the traditional pahko, prayers are offered by the pascolas first to the santos brought from the church and then to animals, and the pascolas' first movements are awkward as they move metaphorically from the enchanted world of the huya ania to the "strange" world of man. These actions mark the beginning of the penetration of the sacred world represented by the pascola into the everyday world of man and the Christian world of the church. By the time "the world turns" at midnight, the pahko rama has become that enchanted world. Then follows

a traditional sequence of Pascola pieces which must be danced to after midnight. These are for the most part about or dedicated to various kinds of animals, and from them sometimes the Pascolas take their cues for variations in their dances. It is into a world not of the church-town, but of the huya ania that the Pascolas induct the townspeople who watch them.[ 40]

Thus, the ritual experience, like the deer singers' songs, is

an expression of the equation upon which the aboriginal part of Yaqui religion is based. That equation links the gritty world of the pahko rama with the ethereal flower world [the sea

ania], a world seen with one unseen, a world that is very much here with one that is always over there.[41]

Again, we have the mask as a central symbolic device in ritual activity designed to "lift the mask" of the material world to allow an experience of the "hidden" world of the spirit. Under that mask, the individual Yaqui or Mayo sees what the peoples of Mesoamerica always saw—the essentially spiritual force that is constantly at work creating and sustaining life. In Mayo terms:

We have made a commitment or an obligation with the earth. We move above the land, we make earthen pots and plant the land. To Our Father (Itom Achai) we ask the favor, that we be able to easily till (break up) the land. Thus we eat from the body of the land. In exchange for this favor at the time of our death the earth will eat us. We have a commitment with the earth. We have an obligation to Itom Achai. We are baptized Christians and not animals. Thus we have this commitment to Itom Achai. When humans die the earth will eat us up, but God will restore us.[42]

Or as the Yaqui deer singer, Don Jesus, put it, "That is the way we people are; we are made to die."[43] But while individuals die, life is eternal. Contained metaphorically within the huya ania, that eternal life-force shows itself through the ritual events in the pahko rama. The ritual experience of that force enables those who participate to "secure their existence, enjoy themselves, and . . . see and feel the truth of their beliefs."[44]

That fundamental theme of rebirth can be seen in the pivoting of the pahko on the moment "when the world turns," the moment of midnight marking the death of one day (or "sun"), and the birth of the next as the sun passes the nadir in its nightly journey. Significantly, in the phase of the pahko beginning at midnight, various "skits" in which the pascolas dance as animals—denizens of the huya ania—take place. The most popular of these[45] involves the killing of the deer by the pascolas who impersonate either animals or hunters and dogs. In this skit, "the pahkolam's burlesques and the deer singers' song sets come together to provide an expression of the very core of the ritual of the deer dance that is as powerful as any we know."[46] This power comes directly from the theme of rebirth, a theme connected here with the sea ania aspect of the huya ania.

The deer continues to speak [through the songs of the deer singers] as he is carried back to the kolensia, his favored haunt, and laid out there on a bier of branches gathered from each plant in the wilderness world [huya ania]. The transmogrification of the deer that occurs there as his physical body is divided is imaged in the final five songs of the set. A tree asks for the deer's tail:

Put a flower on me

from flower-covered person's flower body

As his flesh is roasted, his hide tanned, and his innards thrown to glisten in the patio, no doubt awaiting the vultures who gathered to talk about him earlier, the deer speaks:

I become enchanted

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I become flower.

This graphic sequence of images of death and rebirth indicates, in the words of Don Jesus [the deer singer], that "the deer's spirit stays in the wilderness."

The last song of the set describes the now-dead deer in contrast to a stick that is actually one of the pascolas, a creature of this world in the drama:

Over there, I, in the center

of the flower-covered wilderness,

there in the wilderness,

one, good and beautiful, is standing.

But one stick,

not good and beautiful,

is standing.[47]

The death of the deer thus frees his essence, a metaphor for the life-force, to return to its source "over there" in the huya ania. More important, this ending separates spirit—the deer essence "over there" in the sea ania—from matter—the nonliving stick that is "here" in this world. The commentary of the song is direct and to the point: spirit is "good and beautiful" while matter unsupported by spirit is "not good and beautiful." Goodness and beauty are complementary inner qualities that, when present, can be expressed externally or can be worn as a mask to reveal the features of the spirit in the way that the deer dancer wears the deer head atop his own and the pascola wears the mask over his face. The return of the deer, through death, to the huya ania completes the cycle of the pahko when this skit is performed as the obligatory first deer song describes "saila maso, little brother deer, as a young deer, a fawn. During the night of the pahko he will grow up. In this song we talk about him coming out to walk around and to play in an enchanted opening in the flower world":

Over there, in the flower-covered

enchanted opening

as he is walking

he went out.

Flower-covered fawn went out,

enchanted, from each enchanted flower

wilderness world,

he went out.[48]

The striking similarities in language and imagery between the first and last songs are not coincidental. The singers and the audience know their import: the essence of the deer, for it is that which lives in the flower world, cannot die. It will return

to the "gritty world" of the pahko rama each time the performers and audience gather. And like the deer, life, sustained by spirit, can be counted on not to end.

That this image of rebirth is meant to conclude the pahko is clearly suggested by another skit performed in the latter stages of a pahko which enacts the coming of the rain. Like "the killing of the deer," this skit is often performed at a lutupahko, a pahko performed a year after the death of a family member to release "the family from mourning even as it releases the spirit of the departed from this world."[49] Significantly, "the coming of the rain" is performed only when "the killing of the deer" is not; clearly, they are seen as serving the same function and having the same theme since "water in any form is rare in the Sonoran desert, and it is rain that prompts the miracle of rebirth in this wilderness world."[50] Carleton Wilder suggests that "the direct causal relationship between rain and flowers is explicit in these songs. Flowers are a manifestation of rain."[51] But for the Yaqui, as we have seen, flowers are symbolically a manifestation also of Christ's blood spilled on Calvary. And underlying these two symbolic meanings, flowers symbolize the essence of the huya ania—what we have been calling the life-force. Thus, we have the basic Mesoamerican formulation again, this time in a rather different form. The sacrifice of blood is reciprocated by the coming of the rains. Man, or in this case a life form conceptualized as being in man's world for the moment (Christ or the deer), must be sacrificed so that life may continue. This is the "lesson" of the pahko experience. In the enchanted world beneath the mask of "natural" reality, a world that exists within the "gritty" world of nature, within the community as a whole, and within the microcosmic individual, the essence of spirit is always at work creating and sustaining life.

But the pweplum cannot remain in the enchanted realm of the pahko, and just as the pascola brings them into that communion with the realm of the spirit and guides their experience of it, so the pascola must return them to the everyday world. The second turning point, the one that occurs at dawn, begins this phase of the pahko with the ceremony finally coming to a close as

the senior Pascola stands before the crowd and gives a sermon, an apology devoted largely to asking the pardon of God for any offenses that the Pascolas and their associates may have committed during the night. He says that they may have been irreverent in their jokes, obscene in their antics, careless of propriety in their reference to saints, even sacreligious regarding their own animal sources of power. . . . In this way the Pascolas express their courtesy and humility before God, but only after an active night of taking the crowd into their world of the huya ania and its ways so different from those of the town.[52]

Thus, the ritual of the pahko, by its very structure, allows the Yaqui and Mayo, "out to the last one," a very personal experience of the sacred, an experience through which the masked pascola, as host, enables each individual to lift the mask of the mundane world and see the enchanted, sacred world beneath "with his or her own eyes." Only one may wear the mask, but through the ritual experience all participate in its metaphoric implications.

Such a formulation of pahko ritual carries numerous Christian connotations, especially as it equates the deer killed by the pascolas with Christ, but it is important to qualify that equation. While "contemporary Yaquis often interpret the deer dancer as gathering the wilderness world into a symbol of earthly sacrifice and of spiritual life after death," it must be realized that "contemporary Yaqui culture brings the figure of the deer dancer together with the figure of Christ only implicitly and very tentatively."[53] Interestingly though, while the pascolas play only a relatively small role in church-related ritual and the deer dancer an even smaller one, the roles they do play in the most significant of those rituals are involved with the rebirth symbolized by the moment of Christ's death and resurrection and thus seem to grow directly out of the assumptions underlying pahko ritual. While the connection between their actions and the symbolism of Christ will no doubt remain implicit as the Christian and indigenous conceptions of rebirth are quite different, Yaqui and Mayo ritual does make that connection.

Significantly, the particular church-related ritual to which we refer is by far the most important of the year and is, in fact, "the most inclusive cooperative enterprise in which Yaquis engage as Yaquis.[54] It consumes Yaqui society for the forty days of Lent, reaching its climax in the dramatization of Christ's Passion. Although the lengthy ritual cycle is far too complex even to summarize here as it may contain over forty ceremonial events, each involving the interaction of a number of symbolic forces, it has been treated at length in both its Yaqui and Mayo incarnations by other scholars as has the remarkably similar Lenten drama enacted by the neighboring Coras.[55] In all of its variants, its focus is on the rebirth of life after death—the death of Christ, the "death" of his masked persecutors, and the "death" of the agricultural year—which is generated by the cyclical opposition of two forces. One must die for the other to be born. This festival, more than any other, demonstrates the truth of Spicer's contention that Yaqui religion has "a world view which includes a conception of interdependence between the natural world and the world of Christian belief."[56]

That such an interdependence is fundamental can be seen in the fact that while Yaqui church-related ritual seems to follow the normal Roman Catholic religious calendar and to include the usual ceremonial occasions, it is divided into two distinct segments in a seasonal way not associated with Catholicism. Winter and spring constitute one season, characteristically solemn in its ceremonial tone, while summer and fall comprise the other season, this one marked by a tone of gaiety and well-being.[57] These seasons, of course, are the divisions of the agricultural year: first the period of the planting, growth, and harvest of the crops, followed by the "dead," postharvest fallow time, leading to the sowing and germination of the new crop in June which ushers in the summer/fall season once again. The Easter ceremonial cycle falls roughly at the end of the fallow period and thus can be seen as heralding the beginning of the season of "birth," growth and eventual harvest, a view that fits nicely the drama of Christ's death and resurrection.

But the situation is somewhat more complex than that formulation would suggest. According to Spicer, the actual drama of the Lenten ceremonial is not centered on Christ's Passion but on "the obverse of the Passion, that is, the rise to power and ultimate destruction of the persecutors of Christ,"[58] a group known as the Infantry which includes the unmasked Soldiers of Rome and the masked chapayekas whom they command. As a group, they are opposed to the protectors of Christ, the Horsemen, who are aided in their holy cause by a number of other ceremonialists, chief among them the matachini, dancers who wear a symbolic flower headdress, and the Little Angels, a group of children. At a crucial point in the struggle, the forces of good are joined by pascolas and deer dancers.

The Soldiers of Rome and the chapayekas "are pursuing the most evil of purposes, [but] they are building their own doom, as everyone knows. In the unfolding of the story the steps which appear to lead to their complete triumph also lead to their destruction ... and the restoration of the order and goodness which they have so fearfully threatened."[59] Thus, the Yaqui, and the neighboring Mayo and Cora whose versions are essentially the same, have transformed the linear progression of the traditional Christian story into a cyclical drama. Evil is neither destroyed by good nor does good transcend evil; rather, it is transformed into good by the cyclical movement of time. This transformation can be seen clearly in the case of the chapayekas, the masked persecutors of Christ. These ritual clowns, far more sinister and dangerous than the pascolas,[60] delight in the graphic inversion of accepted values. Their coalition with the Soldiers of Rome "will result in some stupendously evil deed." But under the mask of each of the chapayekas, there is "the father of a family, a respected townsman. Moreover he is in some ways the most worthy of all men in the town because he has undertaken a very arduous task which works for the good of all."[61] Like Christ, he suffers for humanity, in this case the pweplum. Thus, in an exceedingly strange twist of meaning, these persecutors are themselves understood as undergoing a death and resurrection parallel to that of Christ, whom they kill. "Through [their] suffering and confession (death) comes purity and the resurrection, the return to life, of Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday."[62] The forty-day ceremonial period ends with the ritual rebaptism of the chapayekas and the burning of their masks. Evil has been converted into good by the transforming forces of water and fire. Since both persecutor and persecuted are involved in the same cyclical process, it is made clear that while all "evil" will become "good," that "good" must in turn become "evil" since everyone knows that the drama will be repeated the following year when the good townsmen must once again don the evil mask that will later be "converted into the intangible again by burning immediately after use."[63]

It is fascinating that these masks, like the masks of the pascola and the deer dancer, are clearly understood as having their source in the transcendent world of the spirit and are specifically returned to that world after their use in the time-honored Mesoamerican way of "spiritualizing" matter, in the case of the Yaqui and Mayo, by burning and in the case of the Cora, by floating down the river as the dancers wash away their emblematic body paint in what is both an actual and a ritual cleansing. The cyclical nature of the drama is clear, as is its relationship to the seasonal cycle. The Infantry epitomizes the sombreness of the winter/spring season as it symbolically kills the spirit of life, a spirit that is reborn in the risen Christ, the newly baptized chapayekas, and the soon-to-be-planted corn.

The pascola's role in this pivotal drama is small but significant. The climax of the forty-day ceremonial cycle comes not, as one would expect, with the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ but with the battle between the forces of evil and good for control of the church and town. In this symbolic battle, the Infantry—Soldiers of Rome and chapayekas—charges forward and is repulsed three times by the defenders, a significantly diverse group made up of the Little Angels, the children, coached by their godparents, who form the Angel Guard; the Horsemen who are the good soldiers; the Matachin Dancers "with their streaming red headdresses, called 'flowers'; and the Pascola and Deer Dancers beside whom is a high pile of flowers and new green leaves." When the attackers rush forward, the Little Angels emerge with their switches, the Horsemen with their weapons, "the Matachin Dancers dance, and the Pascola and Deer Dancers

reach deep into the piles beside them and throw handful after handful of flowers directly at the running attackers."

In the third rush all is lost. The chapayekas have been weakened by the power of the pelting flowers and the Matachin "flower" headdresses; by the good soldiers, who remain firm in their formation; and above all by the earnest spirit of the Little Angels. The chapayekas cast off their masks, in which their evil power resides, and throw them at the feet of the pyre, where the effigy of Judas is set afire.[64]

"Evil" has been defeated and its symbolic essence returned to the world of the spirit. Its defeat has come through the agency of the angelic innocence of the children, surely symbolic of the Christian world of the spirit, and the flowery weapons of the Matachin, pascola, and deer dancers, just as surely symbolic of the huya ania. Thus, the rebirth of Christ, of his persecutors, of the people of the town, of the seasonal cycle, and of the Yaqui spirit has simultaneously been assured. Significantly, the only part played by the pascola in the entire Lenten ceremonial cycle is directly related to that moment of rebirth.

The role of the pascola in the Lenten drama is thus consistent with, and no doubt grows from, his much larger role in the indigenous pahko ritual. In both, he is directly involved in a dramatic realization of the conception of rebirth. In both, he is connected directly with the moment of transition between the "death" of one phase of a cycle and the "birth" of the next; in the case of the Lenten ritual, the cycle is annual, while in the ritual of the pahko, the daily cycle of the sun provides the metaphorical structure. In both, he is intimately associated with the flowers that symbolize the underlying life-force—whether of the huya ania or God's grace—that provides the motive power for the cyclical movement. The masked pascola dancer therefore unites the two strands of Yaqui religion at their most important point of contact, their symbolization of the movement of the underlying life-force into the world of man and nature. Nowhere is this syncretic role of the pascola made more graphically clear than in a picture that Spicer presents of two pascola dancers kneeling and praying before a pahko rama altar containing a crucifix and santos. In the picture, the crucifix appears directly between the two pascolas' masks, which are worn at this moment on the sides of their heads. Spicer writes, "Before the fiesta begins for which they are preparing, the pascolas will also offer prayers to the Horned Toad and other animals."[65]

The juxtaposition of mask to crucifix in the picture results from a curious part of pascola ritual practice, a part that demonstrates again the tendency to bring Christian and indigenous practices together but to keep them distinct. In the ritual of the pahko rama, itself uniting Christian and indigenous ritual while keeping their separate identities clear, the pascola's dances are of two kinds: one is "an intricate stepdance accenting and embellishing the rhythm" of the music played by a violinist and a harpist, while the other consists of "pawing foot motions, peering gestures with the masked face, and complex rattle play" to the music played by a musician called a tampaleo who simultaneously plays a flute and a drum. When dancing to the music of the harp and violin, the pascola wears his mask on the side or back of his head, but when he is accompanied by the tampaleo, he wears the mask over his face.[66] Although neither Yaquis nor Mayos can explain the reason for this differing use of the mask, scholars generally have seen it as the result of a distinction between the music and dance of European origin and that derived from the indigenous background. True to this distinction, the pascolas in Spicer's picture wear their masks on the sides of their heads while engaging in Christian devotions. When the spirit of the huya ania moves through them into the sacred space of the pahko rama, that spirit "speaks" through the mask, which the pascola then wears over his face. For the mask is the inner reality, the reality of the enchanted huya ania, which ritual allows to emerge into the mundane world of man's daily life.

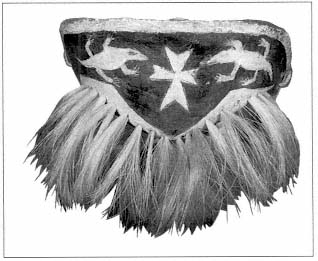

That pascola mask, although found in varied forms,[67] is always recognizable. It is generally small, dark, and decorated with symbolic designs, either incised, inlaid, or painted on.[68] Its features may be those of a goat (pl. 68) or a human being (pl. 66), but it will always have flowing strands of goat hair or horsehair forming a beard and eyebrows. The hair is sometimes so full that it partially obscures the mask's features, but

the hair and its motion are an important aspect of pascola mask aesthetics . . . [for] when a Mayo pascola shows his mask, he carefully unwraps the sashes that he uses to protect it, and smooths the hair out with his hands. Then, instead of sweeping the hair out of the way so that the visitor can appreciate the carved and painted wood, he holds the mask with the face slightly down, so that the hair falls freely. He then wags the mask back and forth, causing the long eyebrows to swing across the face. The value of a mask is seriously impaired when the hair is missing .[69]

As Lutes points out, all of the features of the mask are "symbolic elements,"[70] expressing in the small compass of the mask itself the meanings we have already seen in the ritual activities of those who wear the mask. Those symbolic features include references to animals, the clearest of which is to the goat as a number of pascola masks are made in the image of that animal, and it is even "said that all pascola masks represent goats."[71] Some believe that a pascola who wears such a goat

mask acquired his ability to dance directly from the huya ania,[72] perhaps through a dream in which a goat appeared as a representative of that enchanted world.[73] The importance of the goat symbolism to the pascola mask can be seen in the fact that although the chapayeka often wear masks with animal features, they never bear the features of a goat,[74] no doubt because of the goat's association with the pascola. The significance of the goat symbolism can also be seen in the fact that the goat-featured masks do not generally bear other symbolic designs that might compete for importance.

Such designs are found only on the masks that have human features, and they are images of other symbolic denizens of the huya ania. Mayo masks, for example, often have a zigzag design forming a border, a design that, according to Crumrine, represents a snake,[75] the serpent from the huya ania which may "appear in the power dreams through which a boy can learn that he is to become a pascola ."[76] Lizards, considered "one of 'the little animals of the pascola,'[77] are also frequently found decorating the masks (pl. 67), and it is no doubt through their association with the huya ania that they have come to represent "order and fecundity in nature"[78] and so to be an important symbolic feature of the mask of the pascola who is fundamentally involved with the ritual symbolism of rebirth. Along with snakes and lizards, the masks often contain stylized representations of flowers, which are, as we have seen, the most fundamental symbol within Yaqui and Mayo thought of the huya ania and of the life-force that metaphorically resides in that enchanted world.

These huya ania-related symbolic features sometimes appear, but sometimes they do not. The only symbolic design that must appear on a pascola mask, interestingly enough, is a cross (pl. 67). It is said by both Yaqui and Mayo to be necessary, along with whatever other decorations are found on the forehead of the mask, "to keep danger away from the pascola while he is dancing." For that reason, masks carved to be sold to outsiders often lack the forehead cross. That necessary symbolic feature of the mask illustrates clearly its fundamentally syncretic nature. While it is seen by both Yaqui and Mayo as a Christian cross, it is, at the same time, felt "to represent the four directions and also the sun."[79] In this connection, it is significant that the cross that appears on the masks is often a Greek Cross, or quincunx, which, as we have seen, has been the quintessential representation of the "shapes" of space and time in indigenous thought from the earliest times. This visual similarity is particularly important as there is a great deal in pascola ritual which is linked to these concepts of the quincunx.

Pl. 68.

Mayo Pascola mask, San Miguel, Sinaloa

(collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

The ritual of the pahko pivots on midnight, the nadir in the sun's journey and one of the four points of the sun's daily path which are represented by the ends of the arms of the quincunx. Significantly, that is the least likely of the four "cardinal" points marking the sun's diurnal course to occur to the nonindigenous mind, thereby suggesting the indigenous nature of this conception of the "shape" of time. Midnight and its opposite, high noon, represent the vertical axis of the quadripartite quincunx symbolizing that "shape," and as we have seen, it is that vertical axis that links the enveloping world of the spirit to man's world. The shamanistic "breakthrough" from the earthly plane to the upper or lower world of the spirit can come only on this vertical axis. Here it occurs at midnight.

And the directional implications of the quincunx are associated with the pascola ritual as well. These implications, and their syncretic formula-

tion, can be seen clearly in Molina's description of a part of the traditional opening ritual of the pahko among the Arizona Yaqui.

When they had finished dancing to the tampaleo they started to bless the ground. They stood toward the East, home of the Texans, and they asked for help from santo mocho'okoli (holy horned toad). Each pahkola marked a cross on the ground with the bamboo reed with which the moro had led him into the ramada. Then they stood toward the North and said: "Bless the people to the North, the Navajos, and help me, my santo bobok (holy frog), because they are people like us, " and they marked another cross on the ground. Still they stood towards the West and said: "Bless the Hua Yoemem (Papagos) and help me my santo wikui (holy lizard)" and they marked another cross on the ground. Finally they stood towards the South and said: "To the South, land of the Mexicans, bless them and help me my santo behori (holy tree lizard)" and they marked the last cross on the ground.[ 80]

The pre-Columbian assumptions implicit in this ritual action are striking. Most obvious is the association of the cardinal points with a particular "god," as we might call the denizens of the huya ania, and a particular people. That identification locates the Yaqui in general and this ritual action in particular in the center of the quincunx which is, of course, the symbolic center of the universe, the point metaphorically described in pre-Columbian spiritual thought as the navel of the universe. Like its timing, the metaphoric location of the ritual enables the participants and the community to accomplish the "breakthrough in plane" from man's middle world to the enveloping world of the spirit that has always been the focus of Mesoamerican ritual.

The syncretic nature of the cross, the ritual, and Yaqui and Mayo spiritual thought is emphasized by the fact that these crosses are inscribed on the ground just after the pascolas pray before a crucifix on the altar in the pahko rama. The cross, in both its incarnations, refers to the meeting point of spirit and matter just as it had in Mesoamerica from time immemorial. And the ritual activity, as always, is calculated to bring those two realms together. Thus, it is significant that the masked dancer is seen as protected by the cross from the harm that might befall him in his liminal movement from the plane of matter to that of spirit and even more significant that the cross he wears around his neck is not sufficient; he must have the cross inscribed on the mask itself. Implicit in this necessity is a recognition of the crucial role the mask plays in this meeting of matter and spirit. And also implicit is the metaphorical statement made by the mask of the pascola. It is the same statement made by every mask in the Mesoamerican tradition: essential reality is spiritual and inner, but through ritual, it can be made outer. The mask displays that reality and thus allows the enveloping world of the spirit to enter the world of man. And conversely, by wearing the mask, man enters the world of the spirit, in this case the enchanted world of the huya ania.

Lutes recounts and comments on the words of an elder pascola: "If you continue this road of the paskola, where our hearts speak directly with each other, you will understand more of the clown and find its secrets. My mask has its own demonio and I would not part with it for any other." And that demonio is "a spirit or efficacious power within the physical form."[81] Thus, it is apparent that the mask continues, even in syncretic ritual and thought, to function as a metaphor for the most basic of Mesoamerican culture's spiritual conceptions and that the members of that culture are profoundly aware of its metaphoric meaning.

This metaphoric meaning is the same for the Yaqui and Mayo as it was for their distant forebears at the beginnings of Mesoamerican civilization. As we have seen, the masked impersonators whose features were carved into and painted on rock by the Olmecs were allowing the sacred world of the spirit to move through them into man's world in the same way as the Yaqui and Mayo pascola. Contemporaneously with those Olmec ritualists, the masked dancers of the village cultures of Mesoamerica were engaged in their own simpler, but equally profound, ritual. It is certainly coincidental that the pottery replicas of those masked dancers of Tlatilco could be mistaken for Yaqui or Mayo pascolas—they were the same small masks (pl. 44) and the same cocoon rattles wrapped around their legs—since the separation in time and space between the culture of Tlatilco and the cultures of the Yaqui and Mayo would rule out any direct connection. But it is an intriguing coincidence because it is not only the outward form that coincides. As we have seen, those dancers, separated by almost three thousand years, are dancing to the same set of spiritual assumptions. Their masks cover and reveal the same enchanted world of the spirit.