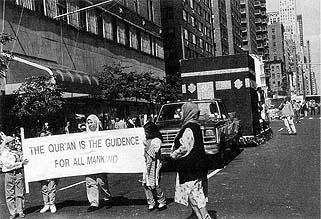

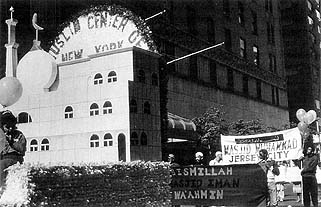

2. Claiming Space in the Larger Community

7. Island in a Sea of Ignorance

Dimensions of the Prison Mosque

Robert Dannin

with photographs by Jolie Stahl

“Islam allows you to look beyond the wall.”

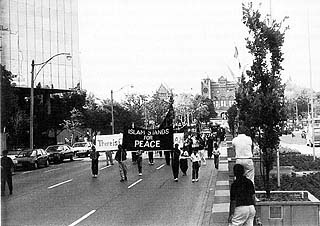

The spatial metaphors in the title and epithet above suggest significant dimensions of the role of Islam in the lives of African-American prisoners. Islam, unlike the “sea of ignorance,” offers an autonomous source of education and discipline in all aspects of life. Islam, moreover, situates the prisoner not only in the context of the controlling prison but in a context that reaches, ultimately, worldwide—“beyond the walls.” At its best, Islam has provided prisoners with order, community, and purpose.

In 1992, the New York State Department of Corrections (DOCS) counted 10,186 registered Muslim inmates in eighty-two different prisons, annexes, and reception centers, a significant increase over the 7,554 counted only three years earlier. African-American Muslims constitute more than 16.9 percent of the total state prison population of more than 60,000, and more than 30 percent of all incarcerated African-Americans.[1] In other populous states, such as New Jersey, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Texas, and California, one can confirm the same trends toward Islamic conversion and its institutionalization in the form of permanent mosques, special dispensations for the faithful, and the professionalization of a corps of Muslim chaplains paid by the state to assist with counseling and services.[2]

Green Haven is a maximum security prison located 80 km north of New York City in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains. Rising from the abundantly lush slopes of upstate farmland to disrupt the traveller’s gaze, the fortresslike prison evacuates its surrounding ecology. The rectilinear form signifies an urban intrusion. Once inside its tomblike labyrinth, sectioned by iron gates, one confronts the reality of Foucault’s “complex social machine” defined by the principles of labor, detention, and surveillance. According to a former inmate, the prison is designed to subjugate the prisoner totally. He is fixed within an architecturally determinate structure of corridors, yards, blocks, and cells, where all quotidian movements are programmed months or even years in advance.

But if one tries to extend the Foucauldian idea of the prison as a simulacrum of the medieval monastery (Foucault 1979), there is a realization that something has changed, because this architecture conducive to introspection and Christian rebirth has increasingly become a place of mosques and communal prayers. The predictable monastic effect has been achieved, but somewhere its content has been subverted. As late as the 1930s, when the access and flow of information could be restricted, it might have been possible to influence the spiritual conduct of inmates and perhaps to limit their acquaintance with anything but the most traditional Western religions. However, by most accounts the Islamic din is now entering its fourth decade in American penal institutions. The significance of this is that the ideals of rehabilitation have been changed by those inside prisons. This is a radical departure from previous models of reform by even the most liberal criminologists (Baker 1964; Brody 1974).

Islam offers a counterdiscipline, a counterforce to the prison’s own ideal of stringent discipline (Cloward et al. 1960). In the words of a young Los Angeles gangbanger:

This attractiveness of the “discipline” of Islam in the context of a repressive mechanism conforms to Foucault’s understanding of the fluidity of power—its direction never quite corresponds to the purpose for which it was initially employed. Islam’s popularity in the prison system rests in part on the way in which qur’anically prescribed activities structure an alternative social space that enables the prisoner to reside, as it were, in another place within the same confining walls.Islam has changed my life tremendously. It has caused me to be disciplined to an extent I never thought possible. I came out of a culture that reveled in undiscipline [sic] and rebelliousness, so to go the opposite direction was major for me.…I firmly believe and see that for the 1990s and beyond, Islam will be an even more dynamic force and alternative for many prisoners, especially the confused youth, who are more and more receptive to the teachings of Islam and the self-esteem it provides them in abundance, not to mention the knowledge.[3]

| • | • | • |

Masjid Sankore: “Medina” for New York’s Prisons

Founded in 1968, Masjid Sankore became the first recognized Islamic institution in a New York prison. Its founders were several African-American converts who in the late 1960s collectively sought assistance from Muslims outside the prison in a crusade to ameliorate their conditions of worship. They turned particularly to the leaders of Brooklyn’s indigenous Dar ul-Islam movement, who soon were making regular visits and offering assistance in negotiating with the prison administration, as well as with the outside world. Eventually, the Muslims won the warden’s approval to establish a permanent prayer hall and named their mosque after an ancient African center of Islamic teaching in Timbuktu, Mali.

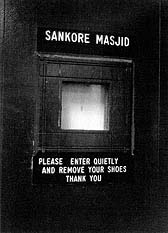

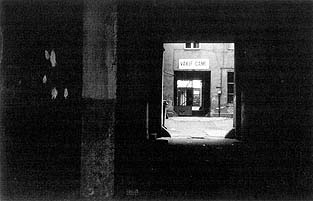

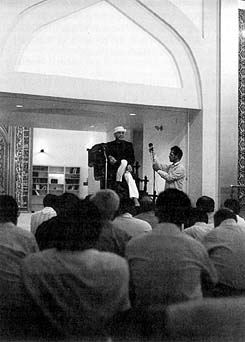

Sankore rapidly outgrew its initial cramped space, eventually taking over the prison’s old tailor shop, a comparatively spacious area with real pillars. The prisoners devoted much time and effort organizing the space into a genuine masjid and a place of refuge from the drab confines of the rest of the prison. “When you walked in there, it was another world. You didn’t feel like you were in Green Haven in a maximum security prison. Officers [guards] never came in. It was like going into any other masjid on the outside; you felt at home,” commented Sheikh Ismail Abdul Raheem, one of the first emissaries from the “Dar” movement to visit Sankore. The door to the mosque announced a transition to a different space (fig. 23). Once inside, it provided space for quiet, interaction, and, above all, communal prayer (fig. 24).

Figure 23. Door to Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

Figure 24. Friday prayers at Masjid Sankore, Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

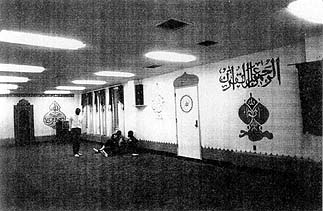

Sheikh Ismail also recalled that, in the early years, both the Sunni Muslims and the Black Muslims (Nation of Islam) practiced a cadenced march through the corridors as if to mark out their own militant counterdisciplinary tradition. That was the only thing they shared, however. The Nation sought and demanded its own mosque, which after 1976 became the American Muslim Mission Mosque (fig. 25), known as the Masjid ut Taubah (the Mosque of Repentance). Today, the American Muslim Mission and the Nation of Islam compete fiercely with the Sunnis for new initiates at Green Haven. Because of official policy, life-sentence prisoners as well as those viewed as potentially disruptive to the prison regime are transferred every few years in and out of the ten different maximum security prisons in the state. Thus as time went on, alumni of Sankore spread their Islamic fervor throughout the correctional system. Simultaneously, the Nation of Islam and orthodox Sunni groups like the Dar ul-Islam Movement won further concessions on behalf of Muslim inmates. In these negotiations with authorities, the Dar’s “Prison Committee” used Masjid Sankore as the standard against which Islamic religious freedom in prison was measured.

Figure 25. The American Muslim Mission mosque, the Masjid ut-Taubah, in Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

By 1972, the official status of Muslim inmates was further enhanced by the role they had played during the bloody Attica uprising of the previous autumn. Contrary to their image as militant radicals, the Muslims in Attica protected their guards and used their power as a disciplined, self-governing inmate organization to reestablish order during a period where the entire prison society was threatened with permanent anarchy. For the first time in history, inmates formed a disciplined syndicate, visibly identifiable by their prayer caps (kufa) and manicured beards, whose outlook was linked neither to the old criminal subculture nor to the rebellious militant ideologies of the epoch. Consequently, the embattled Department of Corrections offered them a modicum of legitimacy and surrendered some of its own power to govern the prison in a tacit alliance with the Muslims.

Following the Attica riot, DOCS designated Green Haven, the scene of similarly explosive tensions, a “program facility,” where emphasis was placed on learning and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment. College courses, vocational training, substance-abuse programs, work release, and family-reunion visits resulted directly from a negotiation of inmate demands and the actions of newly appointed liberal administrators. Muslims were situated at the center of these activities and forced the administration to submit to literal interpretations of laws pertinent to religious freedom for prisoners. During this period, they asserted the right to perform daily salāt, and they even achieved relative financial autonomy by importing and selling legal commodities from the outside. Masjid Sankore instituted classes in qur’anic instruction and Arabic. Prisoners throughout the state referred to Green Haven’s masjid as the “Medina” of the system—a place of hijra in the sense of retreat, refuge, and reconstruction. According to records from the Islamic Center, Sankore had more converts to Islam than any other mosque in America during the years 1975 and 1976. Some of the converts were outside guests or even corrections personnel, who would often volunteer to work Sankore religious events without pay (Mustafa et al. 1989). Other successful prison mosques were eventually started in Attica, Auburn, Clinton, Comstock, Elmira, Napanoch, Ossining, Shawangunk, and Wende. A family reunion visit at Wende is shown in figure 26.

Figure 26. Shu’aib Adbur Raheem, a former imam of Masjid Sankore, and his wife during a family reunion visit at Wende Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

| • | • | • |

The Conversion of Black Power Militants

If Attica provoked a period of liberalization inside these largely uncontrollable institutions, it also stimulated intensification of the covert domestic war led by the FBI against black revolutionaries, who were held responsible for the prison uprisings, as well as for waves of bombings and armed attacks on government targets. In New York, at least a dozen Black Panthers were jailed with sentences of 25-years-to-life. The decapitation of the entire political spectrum of the black movement, including the assassinations of Malcom X in 1965 and Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, led to a general crisis of demoralization among urban blacks. Aided by the Islamic conversion of H. Rap Brown, the imprisoned leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee,[4] an alternative began to attract numerous revolutionary figures whose apprehensions about religion were assuaged by the teaching that “Islam was not inconsistent with their revolutionary goals.” Like Brown, who changed his name to Jamil Al-Amin, they turned their grassroots skills for mass organizing toward Islamic da‘wa (propagation) and soon began to offer the Qur’an to fellow inmates as a substitute for revolutionary or African nationalist literature. The programs of former militants came to envision personal rebirth as a prerequisite for social transformation, a position supported by the passage, “Verily, never will Allah change the condition of a people until they change it themselves with their own soul” (Qur’an 13:11 or 8:53).

The tremendous effect of these words on Black Power advocates is reflected in the testimony of a member of the Black Liberation Army, sentenced to life imprisonment in 1973:

I was a very determined socialist when I was placed in jail with another black leader. He had already accepted Islam, and I was confronted by his daily prayers. At first I could not understand why he was praying to a god who, I felt, had abandoned black people. We argued and battled, but eventually Islam helped me become more relaxed. It relieved a burden because I had become frustrated by the failure of the political movement. And then you read the ayat in the Qur’an where Allah told the Prophet, “Maybe we might show you a victory in your lifetime. Maybe we won’t, but you must keep striving.” So then you start to see things in a broader perspective, outside of yourself as an individual. It was then that I realized that black revolutionaries didn’t suffer a major defeat, but that we were part of an ongoing process that would eventually culminate in victory.[5]

Prison, it can be argued, is a bizarre and violent “university” for those who reach maturity behind bars. There the brutality and corruption of the street are magnified to gargantuan proportions. Even to the extent that he complies with the rules of incarceration, the prisoner becomes entangled in a world of material desires and moral prostitution. From the lowly prisoner up to the warden, by way of the prisoners known as “big men,” snitches, guards, program instructors, and bureaucrats, prison is a pathological society asserting a unique institutional order. This regime codifies various methods used to alter and perhaps destroy the inmate’s physical and psychological integrity. It forces him to regiment his personal habits and behavior in accordance with the social ecology of the prison. In preparation for his eventual release on parole, the inmate studies a “curriculum” of ruse and discipline. He learns few of the many skills necessary to lead a law-abiding life back on the street. Even worse, as part of his daily transactions in the prison environment, the prisoner is subjected to a hierarchy of physical brutality, psychological manipulation, and frequent homosexual rape. The prison is an administrative-bureaucratic space that marks every aspect of the inmate’s existence unless he can use his minimal rights to circumscribe an autonomous zone whose perimeter cannot officially be contested.

| • | • | • |

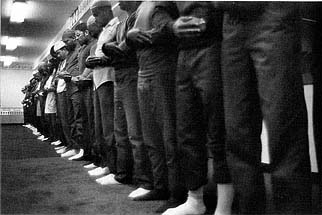

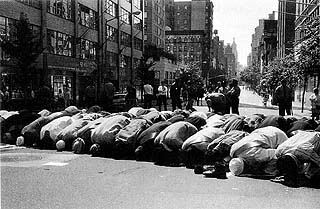

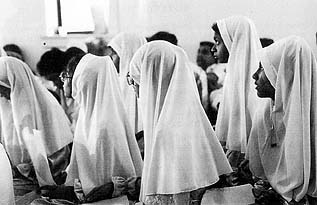

A New Pedagogy of the Incarcerated

Acting through the principle of freedom of worship, Islam meets these conditions and shows a remarkable capacity to redefine the conditions of incarceration. A new Muslim repeats the attestation of faith, the shahada, before witnesses at the mosque. His Islamic identity then means a fresh start, symbolized by the choice of a new name, modifications in his physical appearance, and an emphasis on prayer. He is linked to his Muslim brothers worldwide, as suggested by frequent representations of Mecca in the mosque’s decor, for example in the mosque shown in figure 25 above. More immediately, he is linked to his fellow Muslim prisoners. Inmates like those at Masjid Sankore, thanks to communal prayer, qur’anic and Arabic scholarship, and invocation of shar‘ia have been able to exercise significant group control over their fellows. Historically, Christian prison reformers envisioned conversion as cloistered reflection or silent prayer. Islamic teaching, however, changes self-image and social relationships primarily through communal prayer and qur’anic recitation, which establish ties of identification and action between the Muslim believers and the sacred texts of the Qur’an and Sunna. Through religious practice,[6] the prisoner distances himself from the outside world, conceptualized as dar al-harb, and migrates (hijra) toward the ideal of dar al-Islam, defined not by territory but by Islamic practice. The greater the capacity of the prison jama‘a (congregation) to establish the privilege of congregational prayer, the greater the potential effect upon the individual Muslim. It is an impressive sight to see 50 or 100 prisoners bowing and kneeling in prayer in the middle of a prison exercise yard or in a room isolated within a maze of corridors and cells, as in figure 24, above. Since 1973, after consulting the Islamic Center in New York, DOCS has recognized four holidays: Hijra (New Year’s Day), Maulid al-nabi (the Prophet’s birthday), ‘Id al-fitr (feast commemorating the end of the Ramadan fast), and ‘Id al-adha (feast of the sacrifice). During the Ramadan fast, Muslims can requisition halal meat and are permitted to use the kitchen to prepare iftar meals. For breaking the fast, they are also permitted exceptionally to take some of the food back to their cells.

The Muslim’s cell can be recognized by the absence of photographic images and the otherwise ubiquitous centerfold pinups of naked women. When a man becomes a shahada (convert), he gradually learns the proper etiquette for a Muslim inmate. To reorganized personal space corresponds a changed attitude toward his body for the new Muslim. He tries to avoid pork and other non-halal foods; some prisoners even object to the use of utensils that have touched forbidden foods. The issue of providing halal diets to Muslim prisoners in New York State has been in litigation for many years, with the state now using the excuse of budgetary constraints to refuse. The convert also becomes concerned with wuzu (ablution), here transformed into a code of personal cleanliness and grooming. In addition to their kufa (skullcaps), beards, and djellabah (long shirts), the Muslims are usually well scrubbed, and, as advised in the orientation booklet, often wear aromatic oils when entering the mosque. The use of personal toiletries defines the Muslim’s body as different from the sweaty, disciplined body of the ordinary prisoner. Cigarette smoking is also frowned upon among orthodox Muslims.

In respect to a prisoner’s repressed sexual desire, the Islamic regime acquires double significance in its strict opposition to homosexuality. Certainly, it upholds qur’anic injunctions and encourages the sublimation of desire into a rigorous program of study and prayer. More subtly, however, a man’s adherence to these injunctions illustrates counterdisciplinary resistance to one of the more overt dominance hierarchies encountered in prison life. Sexual possession, domination, and submission represent forms of “hard currency” in prison. Thus by asserting the distinction between halal and haram, between what is permitted and what is forbidden, the Muslim community simultaneously follows Islamic law and negates one of the defining characteristics of prison life.

The most contentious issue regarding the prisoner’s body involves surveillance and personal modesty. For example, during the 1970s, the Prison Committee worked with the state to arrange special times for Muslims to shower as a way to ensure privacy. Eventually, DOCS designated Thursday nights for Muslims to coordinate showers among themselves. A related yet unresolved issue is the “strip search,” when men are forced to strip naked and submit to an inspection of their body cavities. Many prisoners refuse to undergo this procedure. Consequently, they file grievances, risk being “written up,” sent to the “hole,” or even beaten if they refuse too vehemently. Lawsuits have been filed, but the courts have backed up the wardens, who insist that security issues take precedence over freedom of religious expression.[7]

The Muslim community generates a certain degree of physical, emotional, and even biological relief from the grinding prison discipline. This extraordinarily synthetic capacity to alter the cognitive patterns of an inmate’s world may even carry over into the realm of taste (halal diet), sight (reverse-direction Arabic script, calligraphy, absence of images, geometrical patterns, etc.), and smell (aromatic oils, incense). By staking out an Islamic space and filling it with a universe of alternative sensations, names, and even a different alphabet, the prison jama‘a establishes the conditions for a relative transformation of the most dreaded aspect of detention—the duration of one’s sentence, the “terror of time.” No other popular inmate association has proved itself capable of redefining the prison sentence in such a long-term way, for in its most successful manifestation, Islam has the power to reinterpret the notion of “doing time” into the activity of “following the Sunna of the Prophet Muhammad.”[8] Prisoners spend much of their time engaged in qur’anic study, conducted according to a nationwide curriculum, moving through various levels from elementary instruction in beliefs and behavior (‘aqida and adab) to advanced scholarship in law, qur’anic commentary, and theology (fiqh,tafsir, and kalaam). There is even a course in leadership training to prepare prisoners for their roles as imams in other jails or on the street.

Materials for these classes, including cassette and video tapes and books, were initially donated by concerned Muslim organizations, but for the past ten years, Muslim inmates themselves have earned surprisingly large amounts of cash through their monopoly of the distribution and sale of aromatic oils, incense, and personal toiletries throughout the prison system. These funds are also used for the elaborate carpentry and calligraphic painting that is done in their mosques, as well as for the catering of ritual feasts for the Muslim ‘Id-al fitr and ‘Id al-adha holidays. They contribute to the sponsorship of intramural cultural events, which are often staged for the purpose of da‘wa. Sankore even published a critically acclaimed newsletter, Al-Mujaddid (The Reformer), which has found its way to important readers throughout the Muslim world sparking international concern for Sankore’s inmates, as well as donations in the form of Qur’ans and other literature, from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan. Sheikhs, diplomats, and other emissaries from Muslim countries traveled to Green Haven to visit Sankore. Even the late Rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the Jewish Defense League, met with Green Haven’s Muslim community to thank them for the hospitality extended to a Jewish inmate who was welcomed to conduct Hebrew prayers in a corner of the mosque after being ostracized by his own synagogue. The prison mosque is not only the center of religious instruction but also serves as an alternate focus of authority within the prison. Its power is determined mainly by its large membership, who legitimize the influence of their chosen leaders with respect to the larger inmate hierarchy, encompassing representatives of powerful ethnic gangs such as the Mafia and the Chinese triads, or white fascist parties such as the Aryan Brotherhood and the Ku Klux Klan.[9] For example, in the late 1970s, Sankore’s inmate imam was Rasul Abdullah Sulaiman, who came to prison already possessing some of Malcolm X’s charisma because he had been a prominent member of the latter’s entourage. He quickly rose to such a powerful position within the prison that he had his own telephone and traveled around the place at will, accompanied by a corps of surly bodyguards. He arranged the visits of outside Muslim dignitaries, brought family and friends of the prisoners into the masjid for prayer every Friday, and reportedly even constructed a network of small bunks inside the mosque for conjugal visits after jum‘a (Friday prayer).[10]

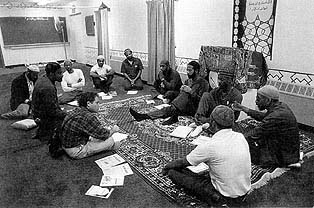

This was the period when Sankore achieved its reputation as the most important center for Islamic da‘wa in America. Before his release in 1980, Rasul married the mother of a fellow inmate, and his new “stepson” was elected imam. This union resulted in the effective and orderly transition of power in the mosque after Rasul’s release on parole. “Sheiks” who study tafsir, fiqh and Hadith, moreover, use these skills to play a role in councils (majlis) to resolve conflicts and keep the peace (fig. 27). They challenge the secular jailhouse standard of status based on physical strength or a manipulative intellect.

Figure 27. The Majlis ash-Shura, or high council, of Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y., with the author, 1988. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

It is possible to explore the deeper implications of the Islamic pedagogy of African-American prisoners if we look at the process of Islamization as a negotiation between the prison authorities and the Muslim inmates where the state’s logic of institutional order meets the fundamentalist doctrine of Pax Islamica, according to which the world consists of only two domains, the dar al-Islam, literally, the House of Peace, and the dar al-harb, the House of War, which is identical with non-Muslim territory. The reorientation and purification of personal space is made possible for the Muslim prisoner through a serious counterdisciplinary regime. Once he is known as a Muslim, the prisoner has little choice but to follow this new set of rules or else he risks at least the disapprobation of his fellow inmates and possibly a physical lashing. Non-Muslims who have been around long enough to understand the alternative set of rules will even admonish the novice convert (mubari) if he is derelict in performance of his obligations.

As enforced by the incarcerated community in general, the shar‘ia becomes an autonomous self-correcting process administered by and for Muslims. “A Muslim’s blood is sacred. We will not allow anyone to shed a Muslim’s blood without retaliation. The prison population knows this and would prefer for us to handle our situation.”[11] So widespread is the fierce reputation of the incarcerated Muslim that the most ruthless urban drug dealers carefully avoid harming any Muslim man, woman, or child lest they face extreme prejudice during their inevitable prison terms.

If this capacity to purify and control Islamic space is remarkable in its consistency, it is not without problems. Inmates may come to Islam merely for protection, not to find a new life. Or they may mistakenly believe that they can absolve past misdeeds and change themselves simply by changing their names and reciting the kalima shahada. They then give the outward appearance of devotion but end up returning to prison having committed the same crimes. Generally, however, low recidivism rates and success in the rehabilitation of drug and alcohol addiction, win tolerance, even approval, for Muslims (Caldwell 1966).

The numbers of practicing Muslims remain significant and their influence continues to rise among the transient populations who fluctuate between prison and the devastated streets of America’s urban ghettos. This calls to mind a comment to the effect that all African-American youths have at least some familiarity with Islam, either through a personal encounter, a relative, a friend, a fashionable item of apparel, or, as is more frequently the case today, in the form of rap music poems.[12] Islam constitutes a cultural passport, whose bearer may exercise the option to depart the anomic zone of ghetto life for destinations mapped out by the Qur’an and Sunna. Nowhere is this option more evident than inside a maximum security prison, where the literal interpretation of the Prophet’s hijra functions as a utopian itinerary and an alternative vision of truth and justice. It insulates the prisoner against the dulling experience of incarceration by inducing him to a regime of five daily exercises (salāt), consisting of a series of obligatory prostrations, that not only transforms the physical relationship to his immediate personal space but also restructures time according to a daily, weekly, and annual calendar of rites that correspond neither with the prison nor with American society at large.

In this sense, Islamic pedagogy has an invigorating effect upon the prison convert. The Qur’an becomes his instructional manual of counterdiscipline. Its study opens more than new scriptural potentials and interpretive traditions, more than simply a new grammar, phonetics, and vocabulary (Arabic), but also an impenetrable code whose messages elude all but the most devout. As a consequence, this counterculture is not simply a ritual of distraction but an ontological reconstruction occurring within a well-defined space, dar al-Islam, characterized by a common set of sensory values evident in smell (aromatic oils, incense); sight (elimination of literal and plastic art forms, elevation of figurative and stylized forms); sound (qur’anic recitation), taste (halal diet) and touch (promotion of strict interpersonal modesty). New intellectual values focus upon the Islamic sciences, particularly fiqh, and new ideas about geopolitics and history from an Islamic perspective.

These values have compelled many African-Americans to review traditional interpretations of their ethno-history, literature, and folklore. Through the prism of Islam, the African-American Muslim invokes a new hermeneutic of power: historically captured, enslaved, and transported to the New World, then miseducated and forced to live an inferior existence, the African-American must enshrine powerlessness even in the act of remembrance, celebration of, or reverence for his ancestors. But his conversion to Islam adds new dimensions to that history, particularly as it emphasizes the presence of African Muslims and nonslave populations, as well as evidence of resistance to Christianization.

Islam symbolizes the aggregate value of authentic African-American culture. In the past, dance, music, fashion, narrative, and even certain forms of Christianity (e.g., Afro-Baptism) have served to mediate, if not transcend, social, racial, and economic oppression. As revealed through the experience of prison da‘wa, Islamic discipline has the power to effect this ontological transformation through a series of counterdisciplinary measures. In terms of social relations, Islam teaches that those who lack the power to transform their material conditions need only reflect upon the ideal qur’anic past in order to see themselves as contemporary actors in a world whose rules of social distinction are neither tangible nor fixed unless they are divine. In this way, Islam deals with class, ethnic, and racial differences—even those as widely divergent as between freedom and incarceration—by collapsing the past, the present, and the future into a simultaneity of space and identity. To the extent that Islam succeeds in America’s prisons, it offers a closed but definitive response to the modern dilemma of justice in an unjust world.

By instituting a strict code of behavior and by networking with other prisoners, the Sunni Muslims established a unique identity. While they are predominantly African-American in membership, there are now a few Arabic- or Urdu-speaking prisoners, and more recently a handful of Senegalese Muslims. Green Haven today, however, as noted above, is divided between two mosques, Sankore and ut-Taubah. The Muslims at ut-Taubah have pledged bay‘a to Warith D. Muhammed, whose imams are always the civilian chaplains appointed by DOCS.

In Attica Prison, the Muslim communities united in 1985 under the aegis of a strong Sunni presence, but there, too, the administration is seen as fomenting disputes, and the community remains unstable because of ongoing differences between Sunnis and members of Farrakhan’s resuscitated Nation of Islam. The Sunni Muslims, who labored to unify Islam under a homogeneous practice, are seeing their space fission once again. “The Nation of Islam has recently been restructured and separated from the Sunni community.…There are approximately three hundred Muslims in the facility” (Rahman 1989). Less than twenty-five miles from Attica at Wende Correctional Facility, similar issues plagued the unified jama‘a (Raheem 1991).[13]

For all these problems, the goal has always been to create a territory that is neither “of the prison” nor “of the street” but a “world unto itself” defined by the representational space that is common to Muslims worldwide. The profundity of this spatial vision is evident in the metaphor, quoted in the title above, used by one prisoner serving a 25-years-to-life sentence: “In here the Muslims are an island in a sea of ignorance.” Islam’s attraction for prisoners lies in its power to transcend the material and often brutally inhuman conditions of prison. Although it may seem to some just another jailhouse mirage, the Muslim prisoner sees entry into that space as a miracle of rebirth, and one that may even spread from the prison to the street.

Notes

1. The prisons we visited during this study with their 1992 Muslim populations (1989 in parentheses) were Sullivan 84 (112), Green Haven 348 (286), Auburn 310 (234), Attica 388 (327), Wende 125 (74), and Eastern 175 (135). We did not include Riker’s Island, with its active Muslim missionary activity, nor the some 305 Muslims registered among female inmates at various institutions.

2. There are an estimated one million African-American Muslims in the United States today.

3. Letter from Mujahid al-Hizbullahi, 1991.

4. By the late 1960s, SNCC was militant and advocated armed revolution despite its name. H. Rap Brown was the alleged author of the famous phrase, “Violence is as American as apple pie.” He was hunted down and shot by New York police under the same conspiracy law that produced the famous Chicago 7 trial.

5. Interview with Sheikh Albert Nuh Washington on April 11, 1988.

6. Our formulation of the notion of “counterdiscipline” relies on the ideas expressed by De Certeau, especially his discourse on the impact of scriptural recitation.

7. One might argue that the prevalence of advanced electronic detectors, used especially to screen incoming visitors to the prison, obviates the need to continue the strip search unless it is being retained for its general disciplinary effect of symbolic submission and acknowledgement of the state as the ultimate authority over a prisoner’s body.

8. Such formulas are not uncommon in our own secular experience. For example, the practice of substituting an odometer (which measures distance or space) for a chronometer is common during long-distance commercial air travel. An airline pilot rarely mentions travel time. Usually, he refers to time only immediately after takeoff and just prior to landing. On the other hand, he may refer to visual landmarks periodically throughout the flight as a way of representing the distance traveled. Obviously, this practice evolved as a way of easing the journey by relieving the passengers of the “terror of time.”

9. Ironically, the KKK has become a model for cooperation between white prisoners and guards. It is often referred to as the guards’ “labor union.”

10. In the course of this study, we have met at least three children who were conceived inside Green Haven prison.

11. Remark by Jalil A. Muntaqim, a former member of the Black Liberation Army and akhbar (secretary of information) of Sankore.

12. A sampling of the fusion of Islam, the prison experience, and early rap music can be heard on tracks such as “Blessed Are Those Who Struggle” (The Last Poets, Delights of the Garden [New York: Celluloid Records, CEL 6136, 1987]), “Oh My People” and “Hold Fast” (The Last Poets, Oh My People [New York: Celluloid Records, CEL 6108, 1987]), and “Time” (The Last Poets, The Last Poets [New York, Celluloid Records, CEL 6101, 1984]). Another recording, Hustler’s Convention (New York: Celluloid, CEL 6107, n.d.), develops the classic prison “toast,” the prisoner’s autobiographical narrative.

13. For background on the Nation of Islam, see Marsh 1984; Jamal 1971; Malcolm X and Alex Haley 1966; Perry 1991.

Works Cited

Baker, J. E. 1964. “Inmate Self-Government.” Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science 55, 1: 39–47.

Brody, Stuart. 1974. “The Political Prisoner Syndrome.” Crime and Delinquency 20 (April): 102–11.

Caldwell, Wallace F. 1966. “A Survey of Attitudes Toward Black Muslims in Prison.” Journal of Human Relations.

Cloward, Richard A., et al.1960.Theoretical Studies in the Social Organization of the Prison. New York: Social Science Research Council.

De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1979. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977. Reprint, New York: Vintage Books.

Jamal, Hakim. 1971. From the Dead Level: Malcolm X and Me. New York: Random House.

Malcolm X, and Alex Haley. 1966. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Ballantine Books.

Marsh, Clifton. 1984. From Black Muslims to Muslims. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press.

Mustafa, Khalil, et al.1989. “Overview Revealing the Premeditated Overthrowing of the Sankore Masjid Green Haven Correctional Facility and Those Similarly Situated Throughout New York State Correctional Facilities.” Unpublished report.

Perry, Bruce. 1991. Malcolm. Barrytown, N.Y.: Station Hill.

| • | • | • |

Interviews

Raheem, Sheikh Ismail Abdul. 1991. Interview with the author, Brooklyn, N.Y. February 12.

Raheem, Shu’aib Abdur. 1988. Interview with the author, Alden, N.Y. November 26.

Rahman, Da’ud. 1989. Interview with the author, Attica, N.Y. July 17.

8. A Place of Their Own

Contesting Spaces and Defining Places in Berlin’s Migrant Community

Ruth Mandel

In a mosque in Berlin, located in a cavernous, unheated former textile factory, now subdivided and shared by a dozen migrant families, a Turkish Sunni hoca (religious leader, teacher, or preacher) told me that he and many other migrants intend to remain in Europe until the last European Christian has converted to Islam. This vision of the transformation of Europe to a landscape populated with Muslims and ruled by Islamic law is not, however, the only one held by migrants from Turkey. For example, some of the minority Alevis from Turkey, in radical contrast, extol the virtues and tolerance of their newfound European homes. These two divergent visions of “place” have created in Kreuzberg—the so-called Turkish ghetto of Berlin—a highly variegated ecology of Muslim experience. For some, Christian Europe is a land of infidels, and most certainly experience religious hardship there. For others, Europe is, rather, a land of opportunity. In this essay, after describing Kreuzberg, I address the complex expressions of Islam among Sunni and Alevi migrants, and discuss some of the ways in which these expressions change as a result of migration.[1]

| • | • | • |

Demography, Zoning, and Square Meters

German discourse about the “foreigner problem” often claims that the high Turkish birthrate will eventually overwhelm Germans demographically, particularly given the negative birthrate among the native German population.[2] Berlin’s foreign population remains the highest in Germany. West Berlin experienced a decline in population over the fifteen years encompassing the early 1970s to the mid 1980s, with the number of residents falling from 2,268,718 in 1973 to 2,156,209 in 1986. However, West Berlin’s foreign population grew from 178,415 to 257,916, about 12 percent of the whole. Despite alarmist rhetoric, however, Turks in Kreuzberg made up only 19.3 percent of the quarter’s legal residents in 1983: of a total population of 139,590, 28.7 percent, or 40,025 residents, were foreigners, of whom 26,952, or 67.3 percent, were Turks. In the next three years Kreuzberg’s foreign population barely changed, standing at 40,087 in 1986, compared to 110,490 Germans (West Berlin Municipal Government 1986). By 1992, the population of West Berlin was 2,163,040. However, German/German unification drove the figure for the new, united Berlin up to 3,456,891 in 1992, of whom 3,070,980, or 88.8 percent, were German. Of the 11.2 percent who were registered foreigners in 1992, 138,738, or 36 percent, were Turks, who thus comprised 4 percent of the city’s total population.

There are far more Turks in Kreuzberg than official figures indicate, and their number would no doubt be larger but for restrictive zoning laws regulating the whereabouts of foreigners. These laws, enforced by the Ausländerpolizei (Aliens Police), identify three quarters of the city—Kreuzberg, Wedding, and Tiergarten—as off-limits to the least desirable foreigners (those from the Third World). These are the three districts with the highest percentages of Turkish residents, with 19.3 percent, 13.7 percent, and 10.2 percent respectively. This restrictive regulation has been only partially successful. Informal restrictive covenants effectively prevent foreigners from renting housing outside these three neighborhoods, forcing them to circumvent the zoning laws. Housing has thus been a perpetual problem for the Turks of Berlin, with people shifting among several occasional and illegal residences. A Turk may be registered with the Ausländerpolizei at an address in a quarter that is not off-limits, perhaps the home of a sympathetic friend or relative, while actually living in Kreuzberg in a flat legally registered to others.

Turks also suffer because of the legally required minimum number of square meters per inhabitant in every flat set in 1977 (Castles 1984: 79).[3] Turkish families commonly fail to meet this requirement, based as it is on German, not Turkish, habits. Turks resort, therefore, to some form of false residency registration. It is not uncommon for a Turkish family of, say, seven, perhaps including three generations, to live, eat, and sleep in two rooms. Turks often sleep on dösek, futonlike mattresses, laid side by side at night and folded up and stacked in a corner by day, when the room becomes the living and dining room.

A visitor usually can ascertain if indeed this is the sleeping arrangement in a Turkish home by the presence or absence of the telltale alarm clock on a low shelf of the requisite huge breakfront in this multipurpose room. (Many migrants work very early shifts on construction jobs or in factories and rely on alarm clocks to waken them at 5:00 a.m.). The breakfront is considered a highly desirable piece of furniture in migrant homes, and is used for displaying china, souvenirs, plastic flowers, family photographs—particularly wedding photos—and countless knick-knacks. In front of the sofa, often used for sleeping at night, there will generally be a long, low table, around which the family gathers for meals. Several adults and children might sleep side by side on the floor of one such room. Moreover, space can always be made for guests. Reactions from the Turks to the space requirement range from confusion to embarrassment, as they realize that they are being legally—and morally—sanctioned for what they take to be normal behavior.

| • | • | • |

Landscapes of Kreuzberg: the Structural, the Social Structural, and the Antisocial

It is no accident that Kreuzberg, the “Turkish ghetto,” is the least-renovated district in western Berlin. In the former West Berlin, it was surrounded on three sides by the Berlin Wall. Today, in Germany, Turkey, and indeed in many circles throughout Europe, the name Kreuzberg connotes a very specific set of images and associations, which revolve around its reputation as “Kleine Istanbul,” Little Istanbul. However, its notoriety was already established long before the Turks’ arrival in the 1960s, for Kreuzberg has been politically marked for centuries (cf. Spitalfields: Eade, this volume). In the seventeenth century, French Huguenot refugees found asylum there. In the nineteenth century, indigent, landless immigrants from Silesia, Pomerania, and eastern Prussia came in search of work. At the turn of the last century, the district served as home to industrial workshops and small factories, as well as to the workers employed in them. A particular form of building structure was erected to serve these working and living needs. This multilayered, structurally dense and complex configuration was known as the Hinterhaus (back/rear house, or building), designed around a series of Hinterhöfe (back/rear courtyards). This living/working arrangement distinctly delimited a highly stratified social ordering, in brick and mortar, of classes and functions. The rear buildings, unlike those in front, were built of plain brick, lacked direct access to the street and to sunlight, had no private toilets, and were invariably noisy and crowded.

Thus, although they lived in contiguous structures, different social classes experienced vastly different lifestyles. Large courtyard buildings, typically about six stories, opened up to secondary and sometimes tertiary and even fourth courtyard buildings. Sometimes an additional building might jut off one of the sides, or stand free in the middle of the courtyard; this might be a factory or workshop. The spacious sunnier apartments facing the streets were reserved for the wealthy workshop and factory owners. Often these apartments would consist of an entire floor of the building—in other words, the four sides of a square, constructed around the inner courtyard. The workers’ flats in the Hinterhäuser behind the main building and courtyard were smaller, darker (in an already dark city, with fewer sunny days than most in Europe) and hidden from street view.

These are the buildings in which Berlin’s Turkish migrants typically live. Many of their mosques, community, and political organizations are located in such buildings as well (fig. 28). Today, most of the flats have been repeatedly subdivided and allowed to fall into disrepair. Although many façades, and some interiors, have been beautified in a public renovation project undertaken in Kreuzberg in the past decade,[4] in the courtyards beyond the often grandiose entrances, the inner Hinterhaus of run-down, dark, dank buildings remains. These façades are not decorated with elegant Stücken (decorative stucco reliefs) like the adjacent streetside buildings, but instead stand in quasi-ruin, occasionally still pockmarked with bullet holes from World War II.

Figure 28. A Berlin mosque seen through a Hinterhof courtyard. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

For many migrants from Turkey, the space of the inner courtyards, where children play and adults socialize, defines their social life. Some apartment houses are known for the regional homogeneity of the residents. Upon entering some of these unrenovated apartment buildings, one is often confronted with the lingering odor of urine emanating from Aussentoileten, tiny shared “water closets” located in the stairwell between floors. In many, there is no central heating, no hot water, and only one cold-water tap. Coal dust in the air settles on clothing, under fingernails, and, of course, in the lungs.

The Germans who live in Kreuzberg are themselves among the powerless: elderly pensioners; alcoholics; the indigent; visual and performing artists seeking loft space for studios, theaters, or cinemas; or other members of counterculture groups, who fall into roughly two categories, the punks and the Alternativen, the latter being the remnants of the Acht-und-sechzigers—the “sixty-eighters,” an expression that refers to the politicized radical activists of the highly charged times surrounding 1968, now closely associated with the Green Party, health food, and communes.[5]

Although for many it is the thriving alternative scene that has lent Kreuzberg its notoriety, for others it is the presence of the Turkish Ausländer (foreigners)—people brought to Germany as Gastarbeiter (guest workers)—that defines Kreuzberg’s identity as Kleine-Istanbul. The large number of Turks who ride the subway into Kreuzberg have given it the sobriquet “Orient Express.” The train’s final stop is a few blocks from Mariannenplatz, a large park favored by Turkish women and families for picnics. Nicknamed Turken-wiese, the “Turkish pasture” or meadow, this park lies in front of a former children’s hospital, since transformed into Kreuzberg’s Künstlerhaus Bethanean, an artists’ center, often catering to the local Turkish community, which sponsors exhibitions, concerts, theater, and a Turkish children’s library. In addition, it provides studio space to local artists and housing and studio space for temporary foreign artists-in-residence. Mariannenplatz is a popular site for summer outdoor concerts and festivals—alternative art and music fairs, “foreigner festivals,” and the like. Political posters and notices of demonstrations are commonplace. Although Kreuzberg may no longer mark an international frontier, the Turks who live there regularly cross a perilous divide separating two different worlds. They navigate between their worlds, not only when they make the annual vacation trip to Turkey each summer (Mandel 1990), but daily when they leave the Turkish inner sanctums of their cold-water flats, their Turkophone families and neighbors, their Kleine-Istanbul ghetto to enter the German-speaking work world and marketplace, where the characteristic economic relations between “First” and “Third” worlds are linguistically, socially, and cultural reproduced.

| • | • | • |

Little Istanbul

Both Sunni and Alevi migrants from Turkey take great care to prevent the moral contamination that they believe threatens them in Germany particularly in the form of haram (forbidden) meat, pork. Helal (that which is obligatory or permitted) dietary laws, nearly unconscious in Turkey, have moved to the forefront of concerns in gurbet (exile). Clever entrepreneurs have used the fear of haram to their advantage and have had great success with their helal industries, which sell everything from “helal” sausage to “helal” bread. Elsewhere (Mandel 1988), I have discussed the explicit association many Turks make between pork and promiscuity, which lends still greater fervor to the conspicuous avoidance of German food, restaurants, grocery stores, and butchers. The result has been a proliferation of shops catering nearly exclusively to Turks. Like the British fish-and-chips shop pictured in figure 2, Turkish food shops in Germany typically put the word helal on their signboards, or even post a certificate guaranteeing helal meat.

One of the central Turkish commercial districts is near Schlesisches Tor, the terminus of the subway. The area boasts dozens of Turkish-owned and -operated businesses, carrying Turkish products for Turkish customers: bakeries, tailors, coffeehouses catering exclusively to Turkish men (for card-playing, gambling, drinking), butchers, greengrocers, grocery stores, restaurants, video rental shops, and Turkish travel agencies, some of which also perform several other functions, such as those of insurance agency, realtor, and translation bureau. There is a storefront office housing the Turkish branch of the German Social Democratic Party. Several “Import-Export” shops sell items such as the coffee cups and tea glasses favored by Turks, colorful shiny fabrics, assorted knickknacks, electronic goods, music cassettes, and jewelry. Some of these shops do an excellent business in items for the dowry and baslik, the brideprice.

German-owned shops close promptly at the legal time, whereas Turkish shops have gained a reputation for staying open late. This is widely appreciated, not only by Turks, but by working Germans as well. Furthermore, Turkish greengrocers have acquired a reputation for produce of much higher quality than that offered by their German counterparts. For example, the greengrocer (manav) I patronized received shipments of good fresh produce twice weekly from Turkey. Many Turks in Berlin, and, increasingly some Germans as well, shop at the weekly Friday Turkish open market (pazar) at the Kottbüsser Tor neighborhood of Kreuzberg, winding several blocks along a canal. Stands sell produce, dairy products, meat, flowers, bread, and spices, as well as olives, feta cheese, Turkish tea, and pork-free Turkish sausages. A major social event, this weekly outdoor market is reminiscent of markets held in Turkish towns and cities. Shoppers exchange news, gossip, glances, recipes, and information, and the mood is one of noisy chatter, bargaining, and busyness. Not far from the market are several mosques. In recent years, attendance at mosques has escalated, and after Friday prayers, the streets around them are filled with Turkish men, many identifiable as Muslim by their skullcaps or hats and characteristic beards.

The oldest mosque in Berlin is not in the heart of Kreuzberg, however. Founded in the nineteenth century, Turk Sehitliki Camii served Berlin’s small Muslim community as a house of worship and a cemetery, now overflowing to a huge adjacent area. Even so, many prefer to repatriate bodies for burial “at home.” Figure 29 shows the mosque’s minaret rising above the burial ground.

Figure 29. Minaret at Berlin’s oldest mosque and cemetery complex. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

Islamic organizations and parties coexist with the mosques and businesses in Kreuzberg. For example, Refah (Prosperity), Turkey’s main religious party, maintains an active storefront shop and local headquarters in the heart of Kreuzberg. It looks like a bookshop from outside, its windows stocked with books and pamphlets in Turkish on subjects like “Marriage and Wedding in Islam”; “Youth and Marriage: A Marriage Guide”; and “How to Pray” (a manual for children). Juxtaposed with this literature are banners and busts won in sports competitions by the organization’s teams. Inside, a few young men may be milling around drinking tea in the book-filled front room, some wearing Refa lapel pins. A heavy curtain separates the front room from an inside room, which is set up for meetings and lectures, with a large Turkish flag in the front.

| • | • | • |

Gurbet: Cinema and Exile

Given this physical setting, how do Turks view their life in Germany? In the mid 1980s, a very popular film called Gurbet told the story of the religious, obedient daughter of a migrant family who always wore total “Islamic” dress (kapali), complete with large head scarves and long coats. She associates with Germans, however, who introduce her to liquor, drugs, and miniskirts and rape her. Meanwhile, one of her brothers has become involved with organized crime and is shot. Another brother tracks down the wayward sister; the girl, afraid of what he will do to her, jumps from the top of a high building and kills herself. Germans are made out to be cold, indifferent, calculating, inhuman, and abusive as employers of Turkish workers. They are immoral and sexually promiscuous. The close-up camera work focuses on crucifixes, the breasts of braless German disco dancers, thighs of German girls in miniskirts, and the like. The entire migrant enterprise is portrayed as fraught with tragedy and shame. The Turks do ultimately return to Turkey, but they return either in their coffins, or bitter in mourning for their dead relatives, cursing the day they left their homeland and villages.

Frequent exposure to movies such as this surely play a role in the Turkish viewers’ fears of and attitudes toward Germans. The fear of foreignness reflected in Gurbet is, however, anything but novel. Rather, it is only a new variation of an old theme. Hundreds of similar movies made in Turkey depict nearly identical narratives; the only difference is that Istanbul, instead of Germany, is portrayed as the corruptor of innocence. The ratio expressing the cultural topography is: Turkish village : Turkish city :: Turkey : Germany.

The same values of home, safety, morality are associated with either one’s village or one’s homeland, and stand in sharp contrast to the immorality of gurbet, represented either as the evil city or Germany. Turkey is the village, and Germany the city writ large. Yet Germany is not Turkey and offers constraints and opportunities that shape religious and ethnic life in ways that may also be seen as positive.

| • | • | • |

Expressions of Islam Abroad: Alevis and Sunnis

For the migrants from Turkey, well-entrenched networks sustain an international movement of personnel that fosters what are seen as competing Turkish and Islamic identities. For example, a bilateral agreement permits the Turkish Ministry of Education to send Turkish teachers to the Federal Republic of Germany to teach public school courses in Turkish history, culture, and civics. These teachers have generally tended to be staunch supporters of Kemalism—by definition, laicists.[6] A lively competition for control of the indoctrination and education processes of the second generation has thus ensued, compounded in 1987 by a major scandal linking key officials in the Turkish government to Saudi Arabian funding of the export of Islamic religious education to Germany.

Many Turks in Germany already were observant Muslims before migrating. However, for others it is the foreign, Christian, German context that provides the initial catalyst for active involvement in religious organizations and worship. In part, this increased identification with Muslim symbols and organizations is a form of resistance (on women and head scarves, see, e.g., Mandel 1989: 27–46) against the prevailing norms of an alien society commonly perceived of as dangerous, immoral, and gavur (infidel).[7] The migrants’ marginality provides the context for explicitly religious expressions and concerns that might not be relevant were they part of society’s mainstream.

Migrants also have opportunities to participate in organizational, preaching, and educational modes that would be illegal in Turkey. All are free from legal constraints on religious activities. The minority Alevis in particular find in the diaspora an environment conducive to expressing their Alevi identity, free from what they perceive as the pressures of a repressive Sunni-dominated order in Turkey.

Repatriated Sunni migrants in Turkey frequently told me that it was in Germany that they had become religious (dinci,dindar); only there had they begun wearing head scarves and attending mosque. Anti-Alevi prejudices migrate along with Sunni Gastarbeiter. Direct contact may overcome some of these, but friendships between the two groups are generally thought of as exceptional. Sunni beliefs about the alleged immorality, ritualized incestuous practices, and impure nature of the Alevis are deeply ingrained. The second-generation young people thus rarely marry outside sectarian boundaries.

| • | • | • |

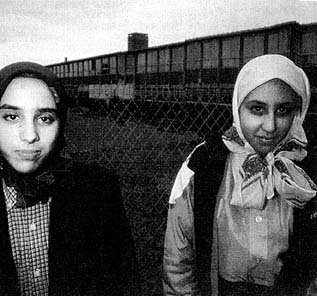

Head Scarves and Alevis

The official government position is that the majority, perhaps 80 percent, of Turkey’s nearly sixty million citizens are indeed Muslim and identify on some level with the Hanefi branch of Sunni Islam. However, it is estimated that approximately 20 percent of the population, some ten million, adhere to the “heterodox” sect of the Alevis.[8] Although the Alevis share many dogmatic tenets with Shi‘ism, they do not identify with the Iranian Shi‘a, the Syrian ‘Alawites, or any other Shi‘a group. For decades in Turkey, the Alevis have had reputations as leftists and communists of various persuasions.

Many, if not most, of the anti-Alevi allegations revolve around morality and women. In Germany, one of the symbolic markers of religious affiliation that has grown in importance is the head scarf. The closer the scarf is to a totally covering veil, the higher its piety/prestige value. Therefore, one mode used by observant Sunnis to differentiate themselves from the Alevis is by the type of headgear one wears or has one’s wife and daughter wear, since a woman’s public appearance directly reflects on her male relatives. Many observant Sunnis are offended by Alevi practices. They speak disparagingly of Alevi women and girls parading about without this symbolic barrier of cloth, an ostensible protector, announcer, and definer of morality.

Alevi women in Germany frequently do not wear scarves. This is especially true of those who were born in Germany or who came as children. Their middle-aged mothers might wear kerchiefs (loosely tied, revealing hair) on the street, but never a complete three-layer semi-veil. This lack of concern for scarves resonates with the Alevi belief system, which privileges inner qualities over external practices and display such as dress. Indeed, the Alevis, like the Shi‘a generally, practice taqiya, dissimulation (in relation to sectarian affiliation). Following the doctrine of dissimulation, Alevi women need not keep their scarves on to keep their identity intact.

Interestingly, the act of shedding the scarf, an act not particularly significant to Alevis, becomes imbued with meaning for some Germans. This is because the Turkish women’s head scarf has entered German discourse as an important symbol, signifying the will and capacity to integrate (cf. Bloul, this volume). Conservative advocates of repatriation point to the head scarves as proof that Turks are fundamentally incapable of fitting into German society. Others, some of whom might defend the continued presence of Turks on German soil, see the scarf as a marker of backward, patriarchal oppression of women, and try to persuade the wearers to change in order to fit in. A minority among this latter group of German liberals are aware of the differences between Sunnis and Alevis. They are quick to appropriate the Alevis for their own political project and to use them as an example of Turks who “successfully integrate.” Thus, both wearing and not wearing scarves are political and polysemic statements in both German and Turkish societies (Mandel 1989).

| • | • | • |

Alevis and Sunnis: Separate Spaces in a Shared World

The migrant diaspora context does little to alleviate the already deep-set antagonisms, suspicion, and animosity between Sunnis and Alevis. In fact, if anything, many Sunnis become still more hostile toward Alevis. The unchecked politicization of mosque-centered religious preaching that proliferates in Germany is often directed against infidel immoral Germans, communists, and, by extension, Alevis. Abroad, located as they are in an environment that is characterized as haram, it is easy for anti-Alevi Sunnis to make the association that these heretical Muslims would not only join forces with Germans of the political left but adopt German moral codes as well. Berlin supports dozens of mosques, which focus sectarian identity. The Mevlâna mosque (fig. 30), for example, is located in a modern Berlin-style high-rise, shared with numerous doctors’ practices and residential apartments. Named for the Mevlevi dervish order founded by Jalal ud-din Rumi, a medieval Persian poet who settled in Konya, this mosque is associated with Sufi devotional practices. The signboard depicts Rumi’s mausoleum in Konya.

Figure 30. Concrete apartment/office block with names of residents (several doctors’ practices) and the Mevlâna Camii mosque, Berlin. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

The Sunnis and Alevis generally live and operate in very different social circles. It is rare for individual Sunnis to be invited to an Alevi wedding or circumcision celebration—or vice versa. When a Sunni friend of mine in Berlin was asked by an Alevi friend and neighbor to be the kivre (circumcision sponsor; godfather) of his son, the novelty generated quite a bit of gossip. Alevis try to do as much business as possible at Alevi-owned establishments, a preference reinforced by regional identity for both Alevis and Sunnis. In Berlin in 1990, for example, a large group of Alevi families collectively pooled their resources in order to open a private wholesale store. Some claimed that they had been excluded from similar Sunni-owned ventures and therefore wanted their own. Both in Istanbul and in Berlin, I often was astonished at the extent and intricacy of how the Alevi networks functioned. Particularly in Turkey, since Alevis are the minority group, they are more sensitive than Sunnis to the subtle clues and signs that indicate who is who.

Alevis may conceal their identity, as did Haydar, a young Alevi man from eastern Turkey in trying to appeal to Sunni customers in his video shop. In 1985, approximately seventy Turkish video rental shops in West Berlin catered to tens of thousands of clients demanding new films several times a week.[9] At Haydar’s shop, the clientele ranged from young children not tall enough to reach the counter to fatigued working people on the way home from work to single young people congregating to socialize. Relatives and friends of the shop’s owner often dropped in, including several young male cousins and their friends, who would sit in the shop learning to play the lutelike saz, associated with Alevi mystical poetry, under Haydar’s tutelage. At times when he had to work at a second job, his wife, Havva, ran the store.

During the Şeker Bayrami holiday (celebrated at the end of Ramadan), Haydar had a bowl of the conventional candies to give to customers, as well as limon kolonyasi (lemon cologne) to squirt on their hands.[10] Although Haydar offered me some candy, he and his cousins refused to partake of it, his nephew explaining, “We don’t celebrate it—it’s not our holiday. Kurds don’t observe Şeker Bayrami.” When I asked, he admitted that he had meant Alevis, not Kurds. Perhaps he thought that I, a foreigner, might know what Kurds were but not Alevis.[11] He may have been testing me; or, he may have preferred not to implicate himself and his relatives as Alevis.

The very act of providing Bayram candy for Sunni customers was telling. Not only would it please them, it was a good business practice. Consonant with the Alevi practice of dissimulation, Haydar could “act” Sunni; he feared that had he not tried to “pass,” he might have lost customers, who would have taken their business to a Sunni.

| • | • | • |

From Ritual to Revolution

Alevi and Sunni attitudes to their stay in Germany seem to differ. More Alevis appear to stay. Not only have Alevis left behind their minority religious status, they also have left a particularly difficult political and economic situation. Many are from the poor eastern, Kurdish regions that have been under martial law and suffered protracted civil war. Thus Alevis tend to see themselves as staying in Germany indefinitely. They are more apt than Sunnis to invest in nicer and costlier flats, while Sunnis might stick to a slum and a simple diet of beans, rice, and bread in order to save their money for investment in property or a business in Turkey. I contend that Alevis, by virtue of their historical tenacity in the face of centuries of repression, massacres, and discrimination, see in Germany, not a land of infidels whose influence is to be feared and avoided, but rather a land of opportunity and tolerance, neither of which they have found in Turkey.

Today, in Europe, several Alevi groups conceive of themselves in explicitly political—and national—terms. Perhaps the most extreme, a group calling itself “Kizil Yol” or Red Path, advocates the founding of “Alevistan,” or a nation of Alevis. Taking its model from the struggles of Kurdish separatists for the establishment of an independent Kurdistan, these followers of the Red Path are criticized by some on the grounds that Alevilik (Aleviness) is a religion, not a nationality. Most Alevis would not support this nationalist expression of Alevilik, and Kizil Yol is far from representative. Nonetheless, the notion of “Alevistan” is compelling, for it suggests the emergence in the diaspora of a consciously discrete identity that gravitates around a fantastic center.

Thus, it is precisely because of their absence from Turkey and their presence in gurbet, in diaspora, that some Alevis have begun to refashion their identity. Moreover, this condition has afforded them the political and conceptual freedom in which to imagine a nation-state for themselves. In terms of notions of place, it is important to note the influence of the discourse of Western nationalisms, and particularly the idea of the nation-state. For what is perhaps the first time, Alevis have begun to conceptualize themselves in terms of place, in a jargon borrowed from the West—territory.

In Turkey, anti-Alevi repression is felt in multiple realms, in explicitly political activity, and also in the religious domain. In particular, the Alevi practice of their central communal ritual, the cem (pronounced “gem”), was until recently outlawed.[12] The cem is the secret communal Alevi-Bektasi ritual of solidarity and “collective effervescence,” involving song, music, and dervish trance dancing, as well as a reenactment of the martyrdom of Husain (cf. Schubel, this volume). As part of Atatürk’s secularization policies, a law enacted in 1925 closed down all tarikats—religious, often dervish, orders—and forbade their ceremonies and practices. Even prior to this ban, the Alevis were forced to practice the rite of cem in secret. The clandestine nature of the cem is not only suggestive of a restrictive and oppressive political and social climate but resonates as well with the dissimulation condoned and practiced by the Alevis. In addition, the ceremony itself reproduces an identification with the oppression and martyrdom of ‘Ali, Hasan, and Husain.

In this diaspora, the celebration of the cem ritual provides a collective grounding for displaced Alevis. Similarly, it offers a familiar and emotionally charged mytho-historical charter, providing and suggesting an associated code for conduct. In recent years it has been celebrated approximately on an annual basis, although in a novel form and setting. A cem that I attended took place in a run-down working-class district of Berlin whose population boasts a high proportion of foreign—primarily Turkish—residents. It was held in a large hall, deep in a complex of large, old Hinterhäuser (like that in fig. 28), now converted and rented out for discos, parties, and the occasional religious ritual.

This cem was attended by about three hundred people, fairly evenly divided among genders and generations. It was complete with the sacrificed animal, divided, cooked, and eaten together. All presented niyaz offerings of food to the presiding dede. Several musicians played the baglama, or saz, throughout the ceremony. After the emotionally charged dousing of the candles (for the twelve imams and martyrs) came the semah, a type of music and dance associated not only with the Alevis but with dervishes generally. There are many varieties of semah, and the men and women who rose to dance to saz music represented stylistic and regional variants. The music is highly rhythmic, begins slowly, then speeds up as the dancers enter a dervish, or ecstatic trance state.[13]

The ritual and the feast are geographically movable. The organizers had brought the proper decor and affixed it to the wall behind the pirs (who are members of holy lineages). This consisted of pictures of Ali, Hasan, Husain, the other imams, Haci Bektash, the Bektashi Pir Ulusoy, and, to be safe (again, dissimulation), there was a large portrait of Kemal Atatürk. Above all these hung the Turkish flag.

Not only did this Berlin cem occur in an unconventional space, the time continuum was radically transformed as well by the addition of a novel element: video. Three video cameras had been set up, with blinding lights, all operated by amateur cameramen. No one thought it peculiar or paid the cameras any heed. The multiple recordings of the ritual on videocassette offer new meaning to the concepts of participant, observer, and event. For example, a few days after the cem, I was in an Alevi home, and someone suggested they watch it on the VCR. It was put on, but after about five minutes the father of the family demanded that it be turned off. He could not tolerate the children laughing and playing in one part of the room and his cousins on the sofa next to him gossiping about what some of the people in the video were wearing. For him, the only way to watch it was to recapture the intensity and sober ambiance of the ritual itself.

Despite the warehouse environment and the foreign context, it is at events such as this cem that Alevi identity renews itself for the migrants and their children. Much of the novelty lies in the very composition of the group participating—for example, the juxtaposition of pirs from diverse regions of Turkey, all seated at the place of honor, the post, with the officiating dede—some of whom had only become acquainted with one another at the cem itself. Until very recently, such a cem probably would not, could not, take place in Turkey.[14] Yet in the diaspora, highly effective informal networks forge a community of a sort that has never existed at home, as it attempts to worship and celebrate in concert.

Conversely, in the diaspora context, some leftist Alevi activists have again reinterpreted the meaning of the cem. A young leftist Alevi man in Germany explaining the cem in terms of the progressive nature of Alevilik said to me, “Without women there can be no cem; without women there can be no revolution.” Thus, the cem becomes the metaphor and template for social change. Quintessentially polysemic, the cem emerges as a ritual act, either reactionary or revolutionary,[15] depending on the context and interpretation. In its very practice, then, it assumes historical importance as an expression and assertion of an identity that must struggle to survive against odds at home and abroad. In that assertion, historical meanings and relations are assimilated and reinterpreted in a new, contemporary context—for example, “revolution.”

Migrant Alevis have in many ways successfully reversed their hierarchical subordination to Sunni Turks. While steadfast in their Aleviness, they identify with and admire many aspects of German society that Sunnis find threatening. Modeling themselves on certain German, Western modes, they pride themselves on how modern they are, as opposed to the “backward” Sunnis. They point to what they see as their more “democratic, tolerant, and progressive” stance, and to the “marked” village clothing many Sunni women wear: flowing salvar pants, head scarves, and so on. Finally, Alevis tend to be more politically engaged in leftist politics and syndicalism than Sunnis, and, through such activities, have greater contact with Germans. This greater contact with Germans reinforces their self-image as “tolerant.”

The differences between Sunni and Alevi attitudes can be seen in the way the two groups speak of Germans. Alevis referring to Germans will say, for example, “They’re people, too,” whereas Sunnis tend to be critical and dismissive of Germans, commonly disparaging them as gavur. Although still peripheral with respect to Sunnis, the Alevis may be slightly less marginal than Sunnis in relation to mainstream German society. As a consequence of their greater acceptance of German ways and people, they have become more accepted by Germans than are many Sunnis. The status of Alevis is also raised in the eyes of Germans by the fact that they characteristically do not attend mosque, and perhaps also by some aspects of the practice of dissimulation.

While Alevis abroad are doubly marginal, with respect to both Germans and Sunni Turks, their relative position vis-à-vis Sunnis has undergone a transposition. In Germany, Sunni dominance has become less and less relevant as a reference point. Alevis had traditionally defined themselves primarily in opposition to Sunnis, and always in relation to them; now, in Germany, they have in some respects gradually replaced Sunnis with Germans as their salient other. Whereas some Alevis in Germany have taken advantage of Western freedoms to adopt a more inward, communal orientation, unfettered by past political and social constraints, others have opted for an ecumenical stance, and still others choose to dissociate themselves from anything they perceive as religious.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion: Toponomy, Almanyali, and New Identities

The migrants’ experience of Kreuzberg both derives from and helps to shape its physical reality. Ultimately, despite their presence in “Gavuristan,” the land of the infidel, surrounded by all sorts of things profane and haram, the Turks manage to create and define a world for themselves. The world they construct lies on frontiers ranging from culinary to linguistic, from sartorial to domestic. These markers serve as functional borders delimiting a new center, which, differentially and subjectively interpreted, defines the meaningful expressions of Turkish identity abroad.

This essay has been concerned with the ways migrants from Turkey fit into the existing urban social and physical structures, and have helped to refashion, challenge, and revalorize the German definitions. Paralleling the defining German nicknames “Little Istanbul,” “the Orient Express,” and “Turkish pasture,” some Turks have their own code names for parts of Berlin as well. Istambulis sometimes use the names of the Istanbul neighborhoods for functionally analogous neighborhoods of Berlin: “Caǧaloǧlu” for a section of Kreuzberg that has Turkish printers, publishers, and bookstores; “Bebek” for the elegant Grünewald neighborhood of Berlin; and Kreuzberg itself might be referred to as Turkey or Istanbul; and “Beyoǧlu” serves as the nickname for the main shopping district in Berlin; an old, out-of-commission covered train station, now converted to Turkish shops, advertises itself as “Türkische Bazaar.” An indoor shopping area in Kreuzberg calls itself Misir Çarşisi—Egyptian Market—the Turkish name for the famous spice bazaar in the old part of Istanbul.

The ability to name itself or be named by others is not the only measure of control over the construction of a community or the definition of group boundaries. In the process of creating and recreating itself, the community does so, on the one hand, in implicit opposition to the German context—in defiance of the official definition of Germany as a nonimmigration land, one implicitly unsuitable for pluralism—and, on the other, against pressures to assimilate. By redefining, or renaming parts of the German urban environment, these Turks are staking a claim and appropriating it for themselves—and on their own terms.

The extensive degree of commercial self-sufficiency is another way the migrants have recreated the place for themselves, and in their own terms. Thus, one need not know a word of German to buy insurance; rent a video; buy pide bread, olives, or helal meat; talk to a child minder at a day-care center; deal with a travel agent; and so on. Thus the motivation for many of the migrants to learn German remains minimal. In addition, the prevailing ideology that most everyone shares remains the “myth of return.” For many, if not most, migrants, Kleine Istanbul is not home. They dream of their final return to Turkey, plan for it, save for it, talk of it. And in their summer vacations, they rehearse it, returning for a month or five weeks.