Mass Dancing

Because of the difficulties of institutionalizing Ausdruckstanz within the subsidized theatres, sizable sectors of the modern dance and body culture phenomenon pursued strategies of group movement that functioned independently of the official theatres, whose expectations and conventions set too many limits on bodily expressivity. These sectors promoted the so-called movement choirs. Movement choirs attempted to construct a dynamic image of community that preserved the amateur status of the performers yet transmitted a convincing, almost ritualistic aura of modernity, grounding an idealized communal identity in a common appreciation of bodily expressivity. Indeed, these lay productions probably appealed more to persons who performed in them than to those who watched them. Much of the pleasure of participating in movement choirs derived from improvisations performed in "appropriated" spaces not usually designated for performance, and in this sense mass movement escaped the constricting regulation of the body associated with literary narratives, although plenty of people did devise scenarios to celebrate the movement choirs.

Laban has received much credit for introducing the concept of the movement choir in Stuttgart around 1920, but the origins of the genre were actually more obscure and apparently owed more to the theatre than its promoters tended to acknowledge. Part of its appeal derived from the enormous publicity generated by the curious, lavish revival of Handel's operas and oratorios, initiated on an annual basis in Göttingen in 1920 and supplemented by numerous professional productions in Hannover and Münster starting in 1923. The driving figure behind the Handel productions was Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard (1889–1954), a master of "mass-suggestive effect," according to a review of a 1924 Handel production (Peusch 99–100). Beginning in 1920, Niedecken-Gebhard staged the old operas (and oratorios) in a radical, antihistoricist style in which the chorus moved

in bold and complex configurations on expressionistically abstract architectural forms such as elevated platforms, stairways, and ramps. With such choreography, the archaic, rococo music and the old stories seemed to awaken a powerfully modern image of dynamic communal identity. No one who examines stills of these and many other Handel productions from this period can fail to observe a sleek, streamlined break with the operatic performance traditions of previous centuries. The chorus did not perform opera dances or pantomime or even choreographed acting—it performed "mass movement," acting as a dynamic, pulsating organism rather than as a mechanically precise corps. More important, the Handel productions showed that mass movement did not exist exclusively apart from theatre, from interior spaces, from elaborate texts, or even from old stories in a highly "domesticated," classical mode. Mass movement appeared to be latent not in the text but in the idea of performance as the foundation for constructing a modern communal identity. Niedecken-Gebhard enjoyed a busy career directing operas in Hannover, Münster, Berlin (1929–1932), and even the Metropolitan Opera in New York (1933); perhaps it is not surprising that he also assumed responsibility for staging some of the most stunning of the Nazi mass spectacles in the 1930s.

Nevertheless, the great majority of movement choir activities occurred outside conventional theatrical spaces, preferably in the open air or in large studios. Mass movement strove more often than not to achieve powerful dramatic expression without being theatrical. Though the Nazis brought mass movement to unprecedented dimensions (largely after 1933), during the 1920s the public consistently identified this aesthetic with left-wing or emancipatory political aims sponsored by the social democrats, the labor unions, the Nacktkultur clubs, the gymnastic organizations, and liberal bourgeois cultural and religious associations. At the 1930 Munich Dance Congress, Otto Zimmermann, leader of a Leipzig "proletarian lay group" called Der Tanzring, presented Achtung! Wir schalten um!, a "satiric dance play" with jazz music by Hermann Heyer that contrasted idealized communist lay movement with dilettantish, ineffectual, bourgeois lay movement.

Mass movement, however, appealed to a wide range of political ideologies, and it is misleading to assume that the aesthetic inherently embodied a totalitarian vision of communal identity. Laban was obviously the most persuasive spokesman for the aesthetic. By the late 1920s, Laban movement choirs affiliated with dance schools alone numbered nearly one hundred, and the generic concept of the movement choir operated in an even wider range of contexts. At the 1928 Essen Dance Congress, Laban spoke about "the choric artwork," declaring that "the lay dance choir is a rediscovery of a much earlier artistic community" in which mysterious ritual was the foundation of social unity and "the spectator play[ed] a secondary role." The reason the lay choir remained suspicious of theatre was that effective mass

movement required large performance spaces that undermined interest in solo or individualistic performances. The pleasure of watching mass movement resembled the joy of watching a "great orchestra" perform; yet "the choric artwork can only be a mirror of our social and ideal will" (MS 88–89). The movement choirs owed as much to gymnastics as to dance techniques, but at the 1930 Dance Congress in Munich, Laban asserted that the value of the aesthetic did not depend on either gymnastic or dance skill. Its value was pedagogic: participation in a movement choir changed the mental, emotional, and physical identity of the performer, enhancing an idealized sense of belonging to an "artistic community" ("Kunstgemeinschaft") (96–98; also Laban, "Vom Sinn"). Laban denounced the undisguised propagandizing of "false" movement choirs, but it was perhaps impossible for the aesthetic to thrive outside of an overt political stance as long as its value resided largely in the power of indoctrination. Mass movement evolved primarily through teachers in classrooms.

Laban himself loved to improvise endlessly with lay choirs. He delighted in devising increasingly convoluted rhythms and configurations of a large group of bodies. Mass movement did not imply synchronized or unison movements; Laban liked to see how a group could maintain unity of identity while containing all manner of different, individualized movements (Figure 63). Mass movement activity resembled Dalcrozian rhythmic gymnastics in its seemingly infinite capacity for improvised variations and for Laban, at least, it became even more exciting without music or text. The improvisational dimension revealed how membership in a group heightened individual freedom. It may seem difficult to comprehend how a powerful sense of communal unity could arise out of improvisation and the abandonment of a guiding, prescribing text, especially because the movement choir leaders, including Laban, did not theorize their methods at all lucidly or systematically (for communal identity was a "mysterious" phenomenon). But the secret of the mass movement improvisational aesthetic lay, I believe, in its gymnastic foundation. An excellent American book by Bonnie and Donnie Cotteral, Tumbling, Pyramid Building and Stunts for Girls and Women (1931), explains (often with photographs and stick-figure diagrams) numerous rolling, balancing, and mounting positions by which bodies in pairs or trios may support each other to create a lively image of bodily interdependence. These include, among many others: the wheelbarrow, the camel walk, the eight-legged animal, the saddleback, the horse and rider, the Jack in the box, the Andy over, the Indian wrestle, the churn the butter, the wring the dish rag, the Siamese twins, the human bar, the archway, the merry-go-round, the treadway, the skin, the snake, the opening of the rose, the opening of the double rose, and thirty distinct pyramid constructions for between six and fourteen girls. Although performance of these stunts entailed rhythmic "counts," music was completely optional and

used apparently only for competitive demonstrations. Most significant, a group could combine stunts with almost infinite variety, and maneuvers designed for pairs or trios could be combined within a larger group to produce a more complex effect.

Of course, one may question what such mathematically driven improvisation says in a deeper sense, other than revealing the intricate coordination and physical trustfulness defining the ideal group. For this reason, Laban subordinated gymnastic aims to the more complex task of constructing a dramatic, emotion-laden, mystical message. This task required not only stunts but symbolically loaded gestures, so that the meaning of group movement derived from semiotic analysis, from a self-conscious manipulation of signs rather than positions. However, the movement choirs seemed unable to produce a solid theoretical apparatus such as Delsarte had introduced in the nineteenth century, and even Laban became distracted by an obsession with "objectifying" movement to the point of draining it of all content. The most powerful source of emotion (and therefore meaning) is conflict. But the movement choirs resisted situating conflict within the group, so afraid were they of undermining their utopian image of the community. (It was a mistake Wigman managed to avoid in her generally small group works.) Consequently, the movement choirs tended to associate conflict with a force external to the group: prudery, capitalism, fascism, communism, technology, industrialization, urbanization, and so forth, often designated more by implication than by any serious embodiment and against which the group appeared as a liberating antidote, a utopia in microcosm.

Significant Theorists of Mass Movement

In Hamburg (1922–1927) and then in Halle (1927–1933), Jenny Gertz (?–1966), a Laban student, achieved unrivaled distinction for her movement choir work with children and teenagers, male and female together. Most of her students came from the proletariat, and for several years she maintained close connections with both the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party, but in the early 1930s she drifted more decisively toward communism. Nudity was central to her pedagogic method, and photographs of her nude students performing outdoor movement choir improvisations are among the most beautiful images of group action produced during the Weimar Republic. Equally unique was her dramatic use of speech to develop bodily expressivity. She would require her students to respond in an imaginative, sometimes complex, but seldom uniform fashion to almost surrealistic commands: "run loudly," "become big very quickly, then slowly become very small again," "be a very small package on the floor, tightly bound," "be noisy people when two cars have collided," and so forth.

The children often inserted their own voices to make the "sound" of a movement. Gertz could combine these tiny body dramas into larger structures, and children themselves might lead the group (Losch 81–87). In collaboration with her friend Rose Mirelmann, Gertz did produce such "choric dramas" for young people as Schwarz-Rot (1930) and Revolutionspiel (1932), propagandistic celebrations of communist idealism. But the Gestapo shut down her school and compelled her to seek exile in Prague, where Mira Holzbachova, another student of Laban, was a prominent communist dancer. Just before the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia, Gertz migrated to England, where she continued to teach children's dance until 1947, when she returned to Halle.

Otto Zimmermann forged a much more "determined" relation between speech and movement than prevailed in Gertz's free-spirited pedagogy. He directed Der Tanzring, a communist movement group in Leipzig, which had witnessed a very turbulent period of red mass spectacles in the early 1920s (Pfützner). For the 1929 Festival of Speech and Movement Choirs in Leipzig, Zimmermann took spoken words from the Internationale and assigned to them specific physical, unison movements. For example, the words "clean table" produced "from sideways position left, right arm swinging wide to the left side in pumping motion"; "power to the oppressed" provoked "right arm stretches spaciously right and sidewards through the space, making a right-pathed circle"; "armies of slaves, awake!" meant "stride forward toward the spectating masses, great lifting movement of both hands deep and high" (Losch 338). But this sort of synchronicity of word and movement appealed to people for whom group solidarity was incompatible with internal variation and, indeed, improvisation. Yet this strategy tended to prevail in the production of large-scale dramatic works written for movement choirs, such as Bruno Schönlank's, staged by Vera Skoronel and Berthe Trümpy at the Berlin Volksbühne (1927–1928), whose movement choir contained seventy persons.

By contrast, Martin Gleisner (1897–1983), an actor under Max Reinhardt and from 1922 on a close associate of Laban, acknowledged that the power of group identity depended on "structured work" and advocated a position between text-driven performance and full improvisation (VP 43–46). From 1925 he directed a Laban-school in Jena with a social democratic–communist orientation: "[T]he movement choir, through the creation of group artworks, is in the strongest sense social " but must not exclude "the bizarre, the dark, the grotesque," for the path to freedom allows the layman "to express everything that is within him" (Gymnastik, October 1926, 150–151). Gleisner's book, Tanz für alle (1928), explained (not very systematically) his pedagogic-aesthetic approach. He sought to create an inherently socialistic form of group dance unique to the movement choir, which entailed deemphasizing gymnastic devices. He wanted a

dance form designed explicitly for performance at festivals of a political character. To achieve this aim, he followed a twofold strategy. First, to establish the social identity of group movement he drew upon old folk dances, especially round dances, and repudiated contemporary social dances, for "the ballroom of our days is a symbol of the anarchistic, bourgeois society of our time" (Gleisner 73). Second, he sought to transform labor-related motions such as sweeping or digging into dance elements and thus to collapse the difference between labor and dance. He also liked to have as many as five discrete groups interacting with each other in a wide-open space, in different modes of movement, until they became one group.

All of Gleisner's "choric artworks" appeared at political festivals, but the documentation on them has largely disappeared, so it is difficult to say what sort of "structured" message he transmitted. Rotes Lied (1929), created to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the German Workers' Singing Federation in Berlin, was probably his most visible work. It was a vast production performed for more than 40,000 spectators in a football stadium. The hour-long piece required separate speech, song, and movement choirs, with a full orchestra playing sections of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony and Tchaikovsky's Pathetique Symphony, as well specially composed marches and folk dances by Alexander Levitan. The speech choir contained 50 speakers, while the singing choir numbered 2,000 and the movement choir 1,000. The choreography "was not illustrative, but rhythmically defined" because the narrative was so abstract. The three-part structure apparently described the power of the group to survive destruction and disintegration and reemerge triumphantly in ecstatic folk dances or monumental marches with red banners (Losch 331–333).

As a socialist and a Jew, Gleisner obviously had no future in the Third Reich, so he migrated to Holland, where he became prominent as a leader of often huge socialist movement choirs, publishing a Dutch translation of his book (1934) and working with the Flemish dancer Lea Daan. In Antwerp, Gleisner and Daan collaborated on a group movement piece, People and Machines (1936), and then produced a film of it, a fragment of which still exists. Images show men and women in worker and peasant garb, respectively, making heavy, lurching, swaying movements in synchrony to signify "toil," but the sexes do not make the same movements. The film fragment does not make clear what sort of music Daan employed. What makes the film unusually compelling is its use of cinematic technique. The camera moves in close to the dancers, films them at low angles from the side and the back, from high angles, and with low angle tracks and pans. The mass bodily movement techniques are designed to be seen from great distances in large spaces, but the camera brings the spectator in close, conveying a peculiar feeling of heroic, monumental physicality and, at the same time, a sense of oppression. It is a rare example of uniquely cinematic rhythms in

which camera movement and editing "dance" with the movement of dancers themselves rather than merely watching them, an effect that only Hollywood's Busby Berkeley had mastered at that time. Eventually Gleisner emigrated to the United States, where he specialized in teaching movement expressivity to older people.

The socialist aesthetic of People and Machines was obviously remote from the Catholic-socialist aesthetic of the massatooneel, which entirely dominated the movement choir phenomenon in Holland and Flanders, where lay public productions were favored on a scale the Germans would hardly have considered revolutionary. The Dutch Catholic girls' association, De Graal, for example, staged Pinksterzegen (1931) with 10,000 girls divided into nine movement choirs of 250 to 4,800 girls each and each choir, representing such things as "seraphs and cherubs," "Grail cadettes," and "October and the Komsomol children," assigned specific, bold colors (Van der Poel 25). The Brussels Credo! (1936), directed by Lode Geysen for the Flemish Catholic Socialist Federation, involved 20,000 performers in a stadium filled with 150,000 spectators. The Dutch-Flemish lay choirs also employed Soviet-inspired constructivist scenography and complex, spectacular scenic technology, which, German socialists tended to feel, undermined the original focus on the body as the source of communal identity. Moreover, distinguished Dutch and Flemish authors such as Henriette Roland Holst, Martinus Nijhoff, and Michel de Ghelderode, composed the texts for movement choirs, and these inscribed the integration of speech, song, and movement with such monumental "structure" that the improvisational pleasure of the German movement choir scarcely emerged (Boon; Van der Poel; Roland Holst) (Figures 64–65). In Holland and Flanders, the socialist movement choir enjoyed a prosperity (or grandeur) in the 1930s that it never had enjoyed in Weimar Germany, but for an improviser like Gleisner the Catholic vision of utopia, immensely inclusive though it was, perhaps excluded too much "the bizarre, the dark, and the grotesque."

Totenmal

The validation of the movement choir aesthetic seemed assured when various of Laban's students incorporated it into theatrical or professional productions. Rogge, Jooss, Skoronel, Feist, Loeser, Knust, and Laban himself produced professional stage works that applied movement choir technique, even though public performance was a secondary aim of this concept. Ironically, the most ambitious and complex use of the movement choir came from a Laban student who displayed little confidence in it as an expression of modernity, Mary Wigman. In 1930, at the Munich Dance Congress, she premiered Totenmal, a work of spectacular ambiguity and fascination. The eight-part "dramatic choral vision for word, dance, and light," written by the

Swiss expressionist Albert Talhoff, called for six separate choirs representing, respectively, the spirits of fallen soldiers (two choirs) and their wives, mothers, sisters, and lovers. The eight parts, or "compositions," included five "halls" and three interludes, with each hall signifying emotional conditions—calls, forgetfulness, expulsion, echoes, and devotion. Of the six choirs, one, the Celebration Choir, consisted of two parts: one part spoke within the halls, and the other part, situated around two "light altars," spoke in close proximity to a color organ. A female dance choir (Tanzender Chor I) and a male dance choir (Tanzender Chor II) never spoke and only danced. A Speech-Orchestral Choir, like the Celebration Choir, contained voices of both sexes. Both of these choirs occasionally spoke in unison or broke into as many as ten groups of voices; one of these groups, for example, consisted of a boy choir. The Instrumental Choir, which played percussion instruments and music (drums, cymbals, bells) composed by Talhoff himself, sometimes spoke or screamed. From out of these choirs came eight figures who spoke numerous solo verses. Another five figures danced without speaking; these included a male Demon and a female Dance-Play figure, performed by Wigman.

It is not clear from Talhoff's text what the total number of voices was for either the choirs or the groups within them. Some of the groups appear to have consisted of voices from more than one choir. The idea, apparently, was that neither the language nor the voices that spoke it belonged entirely to any one community. It was a very complex perception of voice. However, Talhoff's text offered no great distinctions among the voices spoken within it. The strongest distinction within the text was that between Talhoff's language and the quoted language of the actual letters written by soldiers who had died.

In this huge dance, literary language did not construct characters in any way that we might expect from a dramatic text. Instead, Talhoff's expressionistic verse turned the bodies that spoke into abstractions. Whether in a choral or a solo mode, the speaking body projected an anonymous, generic identity. The language created different communities of voice that nevertheless spoke the same types of language and (pacifist) sentiments. No single body seemed powerful enough to express any sentiment unique unto the speaker; each body (and voice) seemed but a fragment of a larger, more abstract communal identity. Despite the communality of desires signified by the interlocking choirs and solo speakers, the dominant mood of the piece was one of profound loneliness, of the living (both genders) separated irrevocably from the dead (male) and vice versa. The distribution of speech among so many choirs, groups, and soloists produced an extremely complex, antiphonal sound world. Wigman treated this sound world as a musical accompaniment to dance movements. Though the choirs and speakers were by no means static, the piece strongly differentiated between

their movements and those of the dancers. Choirs swayed, undulated, or extended their arms but otherwise never moved with the freedom or complexity ascribed to the Demon or the two Dance Play figures. Just as the realm of the dead was immutably "other" than that of the living, so speech remained in tension with movement. Because, however, the text motivated the dance, one must assume that, in this case, language "controlled" movement or shaped it according to its own rhythms. But the text did not make clear how bodily movement "translated" the spoken language that accompanied it. The free verse wildly shifted rhythms from speaker to speaker. For example:

SPEECH AND GESTURAL FIGURE II:

No!!

from the ten million dead

the dead

the dead

for you it is the path out of hate and need assigned

all their peoples

make them holy

holy

beacons of this planet (Darkness .)

CELEBRATIONAL CHOIR:

And no one guesses

that now at last before God and the world

without question

and for murder

hammer of death

falls on all those of this earth—!

INSTRUMENTAL CHOIR:

VOICES:

oh save

save

the light of the world!

light of the world!

the world

world

(Talhoff 71)

To intensify the anonymity and abstraction of the body, all the performers wore eerie masks designed by Bruno Goldschmidt. But whereas the costumes and masks of the males were identical, those of the females were differentiated according to eight archetypal, "feminine" emotions. Mask type determined movement type. Performing before the various choirs was a

lone, unmasked woman (Wigman) who attempted, unsuccessfully, to resurrect the dead through dance. Speech did not issue from her or her counterpart, the shrouded male Demon. The choirs and figures recited Talhoff's verse lamentations for the dead and messages from the dead, and they occasionally exhorted the audience not to forget the dead. Integrated into Talhoff's language were fragments of actual letters written by English, French, and German soldiers who died in World War I. The solo speakers of these fragments were male and invisible, speaking in chanting, Sprechstimme style, individually, from concealed booths.

The sixth composition concluded when Wigman, having apparently revived the dead by persuading the male movement leader to imitate her gestures, became separated from her partner by a sinister male Demon (masked), who compelled her, through dance, to retreat into the shadows. The final (eighth) composition did not involve bodily movement at all: the male and female speech choirs stood rigidly with arms upheld while a color organ bathed the scene in blazing red light and the Celebration Choir thunderously exhorted the audience to believe that God's love will triumph over destructive human impulses toward war. The final "Amen" produced a strange ending. The lone woman appeared to have danced herself to death trying to revive the dead. Yet the sign for triumph over death was a tableaulike image of monumental stasis, with a multitude of bodies frozen in the almighty refulgence. In the end, light and sound were dynamic, not the bodies.

In Totenmal, speech signified a kind of "deadness" but not death itself. Death here had a "demonic" male body, which danced . The (male) dead themselves appeared statistically uniform, but Death was dynamic. The dance of Death was indeed of such power that it vanquished the woman dancer, overshadowed the dance of Life. Yet it was the woman's dance that invited or provoked the appearance of Death. Wigman thus represented Death as a kind of male shadow of the feminine body: dance does not conquer death but drives the dancer toward it, "heroically." The dance culminates in complete stasis, with the male and female bodies of the speech choirs standing perfectly still, the woman dancer and movement choirs absent, and the dynamic configuration of bodiless light accompanied by bodiless dead voices. If we can't see the woman, we can't see death; we can only see the dead, that final condition in which language, speech, and voice are all coordinates of a triumphantly immobile, rather than invisible or repressed, body. Death is movement toward a final stasis.

Dance, then, is not a release from death—it is an exposure of it. Movement makes us see that which is otherwise hidden from us: namely, the view that death is in life rather than opposed to it. For the feminine body, death is "masculine" insofar as it is demonic, a figure of desire, another body exposed by the dancer's effort to use her body to bring things to life. The

lone dancing body of the woman motivates a multiplicity of other bodies that are communal, male and female, speaking and moving, historical yet archetypal, dead yet alive, physical and metaphysical, choric yet suffused with a profound sense of loneliness, abandonment. These bodies are masked, for the other is in itself the mask of identities hidden within the body that is most naked, the unmasked body of the lone woman dancer. By keeping her face unmasked and by wrapping the rest of her body in a medieval-like gown, Wigman effectively dramatized the perception of the "real" or "authentic" body as an intensely death-conscious vortex of tension between exposure and concealment. The chief sign of loneness is nakedness (of the face); the chief sign of otherness is speech; and the chief sign of the dissolution of difference between lone being and the others is movement (KT: Manning 148–160; Prinzhorn, "Grundsätzliches").

Totenmal was probably the most controversial dance work produced during the whole of the Weimar Republic. It provoked a turbulent critical response throughout the country and fascinated audiences during a ten-week run in Munich; some haunting film footage survives. The idea of community signified by the elaborate interlocking of choirs and groups seemed fantastically complicated and saturated with a political ambiguity further intensified by Wigman's unresolved dramatization of tensions between the solo body and the group. Few people were ready to acknowledge that communal unity was an illusion, a matter of masks and generic identities; few people were ready to acknowledge that Death was somehow behind the illusion of unity. But what most touched many spectators was Wigman's monumentally tragic sense of an absent, vanished, or dead maleness, which left the curious impression of a world bereft of heroic identity except for the lone and abandoned female figure.

The political significance of the piece lay in its power to divide audiences rather than unite them. In Schrifttanz (3/3, November 1930), Alfred Schlee, one of the journal's editors, declared that Totenmal had "brought disrepute upon the idea of the ritual theatre" and that Wigman had "wasted her talents on this amateurish creation." "At a time when a number of theatres are fighting for their survival, one single work consumed the amount of money which would have secured a theatre's budget for an entire year" (VP 87). Josef Lewitan, editor of Der Tanz (3/8, August 1930, 15) condemned the piece as "unworthy" of Wigman and asserted that "for dance art and dance evolution Totenmal offers virtually nothing" in "times of direst need," when 100,000 marks might well serve a less "dilettantish" project. But Friedrich Muckermann, a Catholic priest who had addressed the Dance Congress as a proponent of lay movement choirs within the Church, praised Totenmal for its powerful Christian sentiment (Der Gral, 24/8, May 1930, 675). Hans Brandenburg also endorsed the work (Der Tanz, 3/6, June 1930, 5), but he was in a delicate position, having already prophesied (Schrifttanz, 3/1, April

1930) that the piece would inaugurate a new form of dance theatre and choric art. In Der Ring (3/36, 623–628), a "conservative cultural journal" (as it described itself on the masthead), the great psychologist Hans Prinzhorn wrote possibly the most detailed description of a Weimar-era dance performance ever published. Prinzhorn condemned the production for being underrehearsed and relying on a tedious, painfully naive text, then systematically criticized all the multimedia performance elements. Yet he praised Wigman's "dramatic" choreography and dancing, which he said were in tension with the stereotyped message of the text: through movement, Wigman freed perception from "schematized" concepts of action within social reality. He complained that the whole production offered an inadequate understanding of the war's significance and provided no insight into the value of the sacrifices made by all the soldiers who died in it. Prinzhorn blamed Talhoff's script for nearly all of the problems, but when, under the auspices of the Social Democratic Party, Lola Rogge staged sections of the text in Hamburg in 1931, in a far less ambitious or innovative manner, the press response was uniformly enthusiastic.

Wigman never again attempted such a grandiose dance, but neither did anyone else. (Her student Margarethe Wallmann did attempt complicated choric dances, though not an interlocking image of community, in Orfeus Dionysos, also performed at the Congress.) From Wigman's perspective, the problem with Totenmal was logistic: inadequate rehearsal time, an inadequate performance space, inadequate technical support, and, worst of all, inadequate talent within the choirs. Totenmal exposed the limit of the movement choir and of mass dancing generally to signify communal identity. From then on, a large, inclusive representation of community depended less on complexity of group movement and bodily expression and more on the technological complexity of a huge visual design.

The Dance Congresses

The big dance congresses in Magdeburg (1927), Essen (1928), and Munich (1930) were remarkable and complex manifestations of mass dancing. The Magdeburg Congress, in conjunction with the great International Theatre Exposition in that city, was organized largely by Rudolf Laban, Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard, and Oskar Schlemmer. The event attracted about 300 people, but Laban and his disciples overwhelmingly dominated the proceedings. Wigman and her disciples refused to attend because Laban declined to offer them an opportunity to perform. Laban hoped the congress would further his aim of uniting all German dance organizations and institutions under a single federation, but achieving this on paper proved to have considerably less dramatic consequences than he anticipated. Nevertheless, the congress was quite successful insofar as it gave

Ausdruckstanz unprecedented media visibility. An intellectual-theoretical aura pervaded to a greater extent here than in the subsequent congresses. The Jena monthly journal Die Tat (19/8, November 1927) devoted an entire issue to publishing the bulk of the proceedings, and the journals Schrifttanz and Der Tanz emerged directly out of the congress.

The controlling theme of the congress was the institutionalization of Ausdruckstanz . Nearly all the papers and discussions focused on the historical, aesthetic, technical, and organizational difficulties of integrating modern dance into the theatre, the state educational apparatus, and large-scale institutional structures. Impressive lectures addressed dance music (E. Wellesz), dance criticism (H. W. Fischer), dance in the theatre (H. Brandenburg, H. Liebermann), and modern dance as a historical phenomenon (A. Levinson, F. Böhme, W. Howard, O. Bie). Oskar Schlemmer discussed abstract relations between dance and costume and presented models of experimental stages designed by the Bauhaus in Dessau; Laban showed films of his movement choir experiments; and Lothar Schreyer, Gertrud Schnell, Paul Et*bauer, and Gustav Klamt, among others, held a complicated dialogue on the nature of choreography. Unlike other congresses, this one featured extensive exhibition of costumes and set designs, reinforcing the perception of dance as an art defined more by fantasy than by the reality of the body.

But perhaps the most interesting feature of the congress was the series of open meetings conducted to identify the goals of a unified dance federation and the methods for achieving the goals. Some participants, including Berthe Trümpy, Charlotte Bara, and Olga Brandt-Knack, did not believe that modern dance would benefit much from a close affiliation with the theatre, the state, classical ballet, or even lay education. In other words, not everyone agreed that it was in the best interest of dance to construct a broad united front or to accommodate a wide variety of constituencies. Nevertheless, diverse sectors within dance culture expressed a willingness to support each other and to promote new ideas and new values for dance within existing cultural institutions. Laban dominated the congress performance scene with stagings of Titan, Die Nacht, and Ritterballett, and Vera Skoronel presented her mass dance Die Erweckung der Masse . Two evenings offered solo and ensemble pieces from twenty performers, including Hertha Feist, Harald Kreutzberg, Hilde Strinz, Josepha Stefan, Rudolf Kölling, and Ingeborg Roon. Curiously, Die Tat, in its eighty-eight-page report, did not discuss the dance performances at all, though it published most of the lengthy lectures.

Fritz Böhme coordinated the Essen Congress with help from Alfred Schlee, Kurt Jooss, and Ludwig Buchholz. This time Mary Wigman was present, along with Yvonne Georgi, Gret Palucca, Hanya Holm, and Rosalia Chladek. Wigman had formed (March 1928) a new dance federation,

Deutsche Tanzgemeinschaft, to compete with Laban's Magdeburg federation, so no one expected the congress, which attracted about 1,000 participants, to produce an image of professional, aesthetic, or political unity. Panels focused on the themes of dance in the theatre (again), dance notation, dance pedagogy, and (again) the theory of lay dance culture. Unlike Magdeburg, Essen attempted, midly, to situate dance modernism within an international context. Andrè Levinson, from Paris, was on hand again to defend the classical ballet tradition, as was the Javanese dancer Rodan Mas Jodjan. A special Sunday program offered "national" dances from England, Russia, Germany, Java, and Sumatra. The congress hoped to have the Soviet scholar Alexei Sidorow present a slide lecture on Russian modern dance, supplemented by performances of several Moscow modern dance groups, but at the last minute Soviet authorities refused to issue visas. These performances probably would have been the most exciting features of the congress, for knowledge of Russian modern dance during the 1920s was (and still is) frustratingly obscure. Mary Wigman presented her ensemble piece Die Feier , Terpis and Kröller presented ballets designed for the official theatres, and the Essen Municipal Theatre dancers, under Jooss, performed Honegger's Die siegreiche Horatier and Milhaud's Salat . An evening of solo dances included work by Kreutzberg, Chladek, Skoronel, Georgi, and Edgar Frank.

Patricia Stöckemann has spoken unfavorably about this congress, claiming that panelists brought nothing new to the discussion platform and bogged down in "formal things like the length of training time for dance teachers and dancers and the repeated demand for a [state-subsidized] dance academy . . . an artistic stagnation was obvious" (MS 75; also 72–90). From my perspective, the congress's atmosphere of stagnation resulted from the complete failure to address aesthetic issues or to present any analyses of actual performances. When theoretical discourse focuses exclusively on mundane details of pedagogic method, dance notation, and bureaucratic procedure in the theatres, one senses that dance is no longer an art or even a pleasure but an almost incidental aspect of career maneuvering.

The 1930 congress in Munich, jointly organized by Wigman, Laban, Böhme, Brandenburg, and several others, achieved an unprecedented and still unsurpassed scale in dance history. It attracted 1,400 participants from several countries and from numerous schools and theatres across Germany. Scholarly presentations were virtually absent, with only a few lectures on the old themes of dance in the theatre (Emmel, Brandenburg) and lay dance culture (Laban, Gleisner), although Böhme spoke perceptively about the social identity of the dancer. Joseph Lewitan, in Der Tanz (July 1930, 2), complained acidly about the lack of academic reflection, which at a medical congress would seem "grotesque." The major administrative objective of the congress was to formulate accreditation standards for dance academies.

This task proved unexpectedly easy to carry out, probably because it was not difficult to agree on broad categories of instruction—the real (undiscussed) problem was to identify values for dance, domains of meaning. But the great achievement of the congress lay in the huge number of performances from an astonishing variety of artists. Almost everybody of significance in the world of Central European modern dance appeared: Wigman, Laban, Kröller, Chladek, Maudrik, Gertz, Eckstein, Kratina, Loeser, Wallmann, Kraus, Palucca, Brandt-Knack, Klamt, Skoronel, Heide Woog, Dorothee Günther, Mila Cirul, Manda van Kreibig, Ellinor Tordis, to name only about half of the German groups, along with dancers from Holland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria, Poland, Bulgaria, and the United States. A special program featured solo pieces by thirty-five young dancers.

Stöckemann has also complained about this congress, saying that its "failing artistic impulse had a directly frightening and disillusioning effect . . . even the protagonists of the modern dance had hardly anything new to present" (MS 91). But this view seems to derive from the belief that the congress should have displayed a more urgent awareness of contemporary political realities or perhaps a more aggressively avant-garde image of dance, such as Schlemmer and the Bauhaus designers introduced at Magdeburg. If, however, one examines closely many of the works performed at the congress—as I have tried to do throughout this book—the impression emerges of substantial innovation and diversity within the world of modern dance. The congress did not exist to unify dance as a major power broker in the national cultural scene; on the contrary, it served to reveal the impossibility of unifying dance. The congress showed that the more dance expanded in a general, inclusive sense, the more it became fragmented into an enormous program of untheorized performances that supposedly spoke for themselves. The dancing body inescapably constructed patterns of difference, not structures of unity, despite the obsession with bureaucratic rhetoric emanating from nearly everyone who spoke.

Nazi Concepts of Mass Movement

A fourth congress, planned for Vienna, never materialized because of the Nazi takeover. Instead, Goebbels authorized the organization of German Dance Festivals, held in Berlin in 1934 and 1935. These were autumnal rather than summertime affairs and completely devoid of scholarship, lectures, or even panel discussions. Performances alone would purportedly reveal a uniquely German dance aesthetic. But these gatherings were much smaller in scale than the Munich Dance Congress. Georgi, Wigman, Kreutzberg, Maudrik, Kratina, Laban, Palucca, and Günther contributed pieces to the 1934 festival, held in conjunction with a large museum exhibit on dance in art, but the following year only Wigman, Palucca, Kreutzberg,

Maudrik, and Günther returned. Rogge, however, presented Amazonen; Helga Svedlund, ballet mistress at the Hamburg State Opera, gave her production of Ravel's Pavanne; and Lotte Wernicke, a Berlin lay movement choir director, premiered Die Geburt der Arbeit (music: Kessler), a "choric dance play" in six scenes that dramatized the "awakening of humanity and its path to various modes of labor which are the foundation of human community" (MS 159). The Nazi press had criticized some of the 1934 dances, including those by Wigman and Palucca, for being insufficiently or unimpressively German; the 1935 Rogge and Wernicke works were lauded as appropriate examples of "heroic" German bodily movement, but Goebbels apparently disliked Amazonen because it was too Greek in its iconography.

The provinciality of the festival strategy was obvious even to Goebbels; he therefore endorsed the idea of an International Dance Competition, sponsored by the government itself, to coincide with the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The newly formed Reichsbund für Gemeinschaftstanz invited participants from Italy, Poland, Holland, Rumania, Greece, Bulgaria, Austria, India, Yugoslavia, Canada, Switzerland, and Belgium. (Martha Graham declined an invitation to attend because she disapproved of Nazi persecution of Jewish dancers.) The competition emphasized dances of a folk-national character, although the German entries (from Palucca, Wigman, Maudrik, Günther, Kreutzberg, and Kölling) displayed almost no connection to folk-dance forms. Laban promoted the lay movement choir concept as a modern form of folk dance, and he planned a large, four-part "choric consecration play," Vom Tauwind und der neuen Freude , involving 1,000 lay persons from thirty German cities, for performance in the new Dietrich-Eckart Amphitheatre. The piece derived its inspiration from Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra . Harry Pierenkamper directed the first part, "Kampf," employing choirs from Mannheim, Heidelberg, and Frankfurt; Albrecht Knust and Lotte Müller supervised the second part, "Freude," with choirs from nine cities. Heide Woog directed choirs from the Ruhr area in the "Weihe" section, and Lotte Wernicke led the entire ensemble in "Besinnung." As Marie Luise Lieschke, Laban's chief assistant for lay movement education, explained: "We have grown out of the I-and-You era into the We era—but not so that we are merely 'masses': we are a people's community [Volksgemeinschaft], led by the Führer, and our lay dance is education in this sense: to lead and become led" (Wir tanzen , 7). But when Goebbels, along with 20,000 others, attended a dress rehearsal of the production, he (apparently alone) expressed deep disappointment, regarding the piece as too "intellectual" and a dilettantish masquerade of Nazism that really had "nothing at all to do with us" (MS 166). He thus compelled the withdrawal from the competition of both the consecration play and Rogge's Amazonen . From this point on, Laban's relations with the regime became progressively colder, with Rudolf Bode rising to favor as the leader of movement education.

At the Olympic Games themselves, Carl Diem, coordinator of the entire event, had arranged for the performance of a gigantic festival spectacular, Olympischer Jugend , following the 1 August 1936 opening ceremony, watched by 100,000 persons. Directed by Hanns Niedecken-Gebhard, it was a nocturnal event in five scenes. It began with the tolling of the huge Olympic bell and the appearance of 2,500 girls, age ten to twelve, in white dresses, followed by 900 young men in different-colored gymnastic uniforms, then 2,300 teenage girls. Under powerful spotlights these huge groups performed an immense round dance choreographed by Dorothee Günther and Maja Lex to music by Carl Orff. Günther and Lex juxtaposed large, marching phalanxes of dancers against flowering, swirling circles of girls. The second scene, "Anmut der Mädchen," choreographed by Palucca, employed the teenage girls in a vast waltz, followed by a solo waltz, which Palucca danced herself. The music was again Orff's, after Palucca decided she could not dance to the excessively modern piece offered by Werner Egk. In the third scene, male athletes marched with flags from many nations, circling around bonfires and singing hymns composed by Egk. The fourth scene drifted into a tragic mood, commemorating heroic struggle and sacrificial death for one's country. For this scene, Kreutzberg designed a weapon dance for sixty male dancers carrying shields, all of whom "died" in the end; Wigman followed with a lamentational dance for dead heroes involving about sixty female dancers. Again, Egk composed the music for these pieces. The final scene, "Olympischer Hymnus," entailed the singing by everyone in the stadium of the "Ode to Joy" section of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony while the great spotlights, introduced by Albert Speer, panned across the field and soared upward in a stunning colonnade to the heavens.

None of this stirring spectacle appeared in Leni Riefenstahl's film masterpiece, Olympische Spiele (1938), because she and her cameramen did not think they had enough light to shoot the scenes (Downing 83). Instead, she inserted outdoor shots of nude female dancers, undulating "eurhythmically," as she put it, under a cloud-dappled sky. These images of bacchanalian dancing bodies served as the transition from the mythic, male world of classical athletic competition to the lighting of the Olympic flame (Diem's idea) in the twentieth-century stadium. This very mysterious effect dramatizes the unity of the athletic body to nature much more powerfully than the stadium spectacle. But Olympische Jugend dramatized far more vividly the integration of the athletic body into a vast image of community in which all bodies were minute compared to the great movement of the whole.

The assumption persists that, because a fascist government endorsed and promoted Olympische Jugend , mass movement and dancing are inherently expressions of totalitarian ideology (e.g., Manning, 195–201). However, the piece contained no Nazi iconography and glorified youth and Olympian

aspiration as the foundation of an international sense of community. Olympische Jugend treated athletic competition as a political ideology unto itself, to which all other ideologies remained subordinate, if not altogether eclipsed. Still, the relation between mass movement and totalitarianism demands clarification, for the Nazis obviously adopted lay movement choir techniques in the production of numerous propaganda spectacles, especially with the curious genre known as the Thingspiel , which flourished between 1933 and 1937. The Thingspiel derived its name from the Thing , or outdoor judgment space, designated by pagan-Teutonic tribes to decide communal problems. However, the Thingspiel was an expressionistic, multimedia genre designed for open-air performance employing speech choirs, movement choirs, singing choirs, narrators, and elaborate scenographic effects involving banners, marches, loudspeakers, spotlights, and projections. Although the Nazi Party sponsored nearly all performances of Thingspiele , the productions functioned at the civic-amateur level, often entailing thousands of performers supervised by SA and SS officials. The Thingspiel , "which frequently assumed the character of an oratorio," was apparently a genuinely popular genre: the Nazis built amphitheatres to perform the works in 62 cities but could not accommodate the demand for nearly 500 (Eichberg 139).

The texts for Thingspiele came from authors close to expressionism, including Richard Euringer, Eberhard Wolfgang Möller, Kurt Heynicke, Max Halbe, Heinrich Zerkaulen, Heinrich Lersch, Gustav Goes, Heinrich Harrer, Max Ziese. In the Thingspiel , the protagonist was always "the people" (embodied by choirs), who struggled, with simple, heroic pathos, against the evil inflicted by capitalism, bolshevism, Judaism, industrialization, unemployment, hunger, the "backstabbing" diplomats who contrived the Versailles Treaty, decadent intellectualism, gangsters, racial impurity, and the foolish, misguided administrators of democracy in the Weimar Republic. The salvation of the people depended on the emergence of the Führer, representatives of the SA or SS, or potent symbols of Germanic or Aryan heritage. Menz (340) contends that the Thingspiel represented the "revolutionary" phase of the Third Reich, which emphasized the socialism in National Socialism (although a faction around Alfred Rosenberg and opposed by Goebbels stressed reactionary glorification of archaic Teutonic mythology). The revolutionary phase came to an end with the production of Olympische Jugend . From that point on the party ceased to sponsor Thingspiele and drastically curtailed its authorization of independent productions, although Hans Baumann's Passauer Niebelungenspiel appeared as late as 1939. The reason for the policy change remains obscure, but apparently Goebbels felt the party could not maintain sufficient control over the utopian dreams ignited by these productions and over the large measure

of improvisation that prevailed within them (Eichberg 147). Such performances did not adequately prepare the people for the impending reality of war.

The Thingspiel was hardly a uniquely Nazi innovation. Menz (332–333) identifies numerous models for the genre, including Greek tragedy, medieval mystery plays, and the grandiose spectacles of Max Reinhardt; Eberhard Wolfgang Möller claimed that Brecht's Lehrstücke provided superb models for Thingspiele texts. But Eichberg points to more immediate precedents in the mass theatre of the Social Democrats in the Weimar Republic. Festival or "sacramental" plays, often on a huge scale, appeared at mass events sponsored by labor and socialist organizations in the early 1920s, with Leipzig (1920–1924) being an especially fertile site of innovation (Pfützner). Bertha Lask's Die Toten rufen (1923) and Gustav von Wangenheim's Chor der Arbeit (1923) and 7000 (1924) were notable examples before the First International Workers' Olympics in Frankfurt in 1925, which saw a vast production of Alfred Auerbach's Kampf um die Erde . A workers' festival of gymnastics in Nuremburg (1929) featured Mach dich frei! involving 60,000 persons in the spectacular drama of a great proletarian storm troop that "takes up the fight to free all intellectually, economically, socially, and politically enslaved people from their bondage." Yet another festival play, created by Robert Ehrenzweig for the Second Workers' Olympics in Vienna (1931), used 5,000 performers and dramatized the "revolutionary awakening" of the proletariat against "the oppressive ages of industrial servitude." In the final "storm of enthusiasm uniting the masses, the golden idol [of capitalism] sinks away, and from the platform come the lanterns of freedom—at first single torches in a chorus of joy, then bands and streams of light, which surround the high circle and expand and swell through the marathon gate to the accompaniment of the Internationale sung by 65,000. The torch procession, through the Prater to city hall, is joined by the audience" (Eichberg 143–144).

All these productions plainly resembled the Thingspiel in their open-air deployment of marches, flags, loudspeakers, speech and movement choirs, narrators, generic identities, expressionistic language of pathos and euphoria, torches, gigantic emblems, protagonization of "the people," audience participation, and narratives focused on the struggle of the masses to overcome abiding indignities (Rühle 35–40; Bartetzko, 133–143). On the formal level, then, the Thingspiel was scarcely revolutionary. But even after it waned, around 1936, the Nazis continued to stage vast mass spectacles similar to the awesome 1934 party rally documented so ominously in Riefenstahl's famous film Triumph of the Will (1935). With the success of Olympische Jugend , Niedecken-Gebhard, still busy staging Handel operas, became probably the most significant director of mass spectacles in the Reich, supervising the gigantic nocturnal Olympic Stadium celebration (1937) of Berlin's

seven hundredth anniversary. This event involved 5,000 schoolchildren and 7,000 members of the army, Gestapo, Labor Service, SS, Nazi women's auxiliary groups, and Hitler Youth, along with 360 dancers performing folk dances, death dances, waltzes, sword dances, harvest dances, and soldier dances choreographed by such people as Berthe Trümpy, Marianne Vogelsang, and Reich folk dance expert Erich Janietz (Figure 66). In 1938, Niedecken-Gebhard produced Volk in Leibesübungen for an athletic festival in Breslau, this time calling on Dorothee Günther, Marta Welsen, Berthe Trümpy, and Günther Hess to handle choreographic assignments; the piece concluded with a triumphant entry march of flag-bearing army troops under an immense dome of light. Glückliches Volk (1938), presented at the Berlin stadium, showed an idealized, Biedermeier world of graceful, waltzing women (300 of them) protected by an ever-vigilant, heroically disciplined military. Triumph des Lebens (1939), the last of the mass spectacles, was staged in a Munich stadium and again paired "manly strength" and "womanly grace" in gigantic folk dances and marches involving 1,000 girls and several thousand uniformed men. The pieces were choreographed by Günther, Peters-Pawlinin, Trümpy, and instructors from the Elisabeth Duncan school; Maja Lex and Harald Kreutzberg performed solos, and, as usual, the thing concluded with a monumental hymnic surge of humanity toward the swastika (MS 146–149).

Goebbels favored these productions because they adopted the model of the 1934 party rally in Nuremburg, which in itself was an enormous elaboration of the Nazi performance aesthetic before 1933. This aesthetic did not tell stories of struggle and revolution but stressed the reality of the moment . The mass spectacle did not merely imagine utopia but embodied it through manifestations of power and perfection embedded in, rather than signified by, the act of performance: the mystic figure of the leader, gigantic emblems (eagle and swastika), torches, bonfires, spotlights, flags and drums, loudspeakers, dramatic uniforms, the continuous movement of countless bodies across a vast space, and sudden moments of reverential stillness. Individual bodily movements were simple (march-step, salute), synchronized, and unisonal yet nevertheless capable of creating complex designs, such as an enormous, swirling swastika produced by streams of torch-bearing columns. But on a formal level, mass movement on this scale did not differ significantly from the lay movement choirs of Laban and Gleisner. The appeal of mass movement lay in its power to turn simple action into a large-scale, transformative end in itself, a destiny rather than a referent of an imaginary existence. Laban's improvisations with movement choirs shared this reverence for action with the militarized, machine-precise synchronizations of the Nazi mass performance aesthetic, for action in this sense strengthened and ultimately expanded the identity of any group. The totalitarian identity of mass movement therefore does

not reside inherently in the formal qualities of such movement in itself but in the content of the movement, in those symbols and emblems imposed upon the movement that identify action with a "total" vision of community; the symbol, not the movement, subsumes all difference. The same mass movement devices can make a swastika or a star; totalitarianism is not inherent in either. However, the swastika rather than the star became a totalitarian symbol because it urged people to act on behalf of a community that invariably valued sameness over difference.

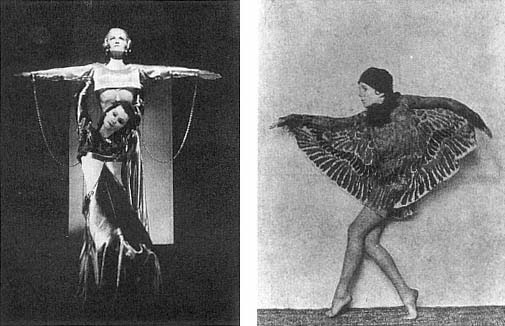

Left: Figure 47.

Mila and Elia Cirul performing Paris, 1935.

Photographer unknown, from AI 21.

Right: Figure 48.

Niddy Impekoven performing Der gefangene Vogel , ca. 1919.

Photograph by Hanns Holdt, Munich, from HB, plate 99.

Figure 49.

Gret Palucca performing one of her

famous leaps, Dresden, ca. 1927.

Photograph by Charlotte Rudolph,

from a contemporary postcard.

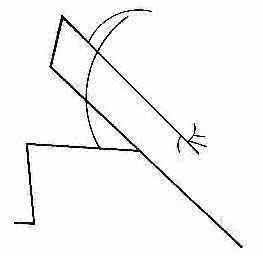

Figure 50.

Gret Palucca dancing. Drawing by

Wassily Kandinsky, from Tanzkurven

zu den Tänzen der Palucca (1925).

Figure 51.

Valeska Gert in a typically impudent pose, Munich, ca. 1922.

Photograph by Hanns Holdt, from Fritz Giese,

Körperseele (1924), plate 75.

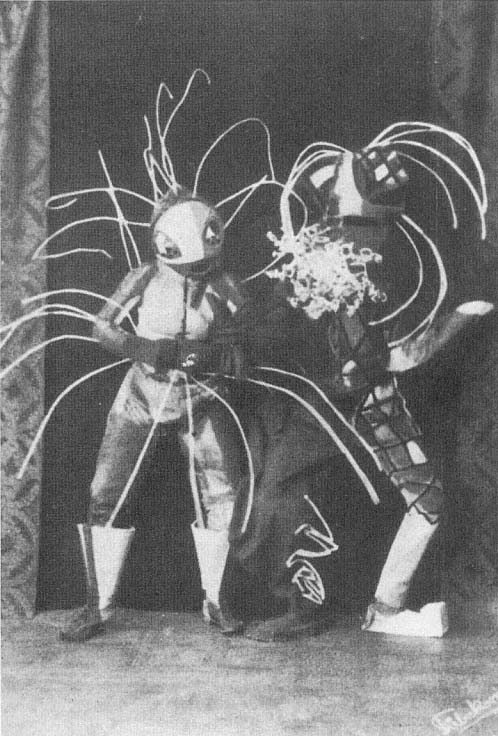

Figure 52.

Walter Holdt and Lavinia Schulz performing as "Tobaggan" and "Springvieh,"

Hamburg, ca. 1922. From Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe.

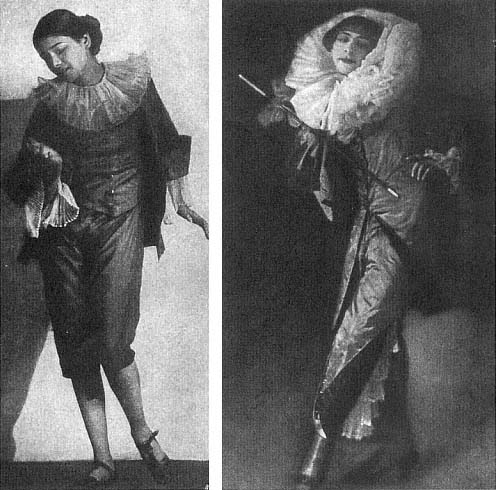

Figure 53.

Clotilde von Derp and Alexander Sacharoff, ca. 1917.

Photographed by Hugo Erfurt and G. Puschtivoi, from HB, plates 48 and 55.

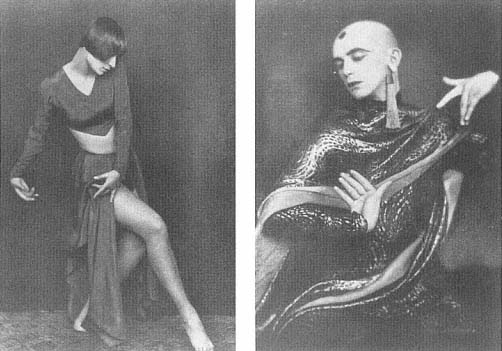

Left: Figure 54.

Yvonne Georgie, Hannover, 1926. From a contemporary postcard.

Right: Figure 55.

Harald Kreutzberg as the Master of Ceremonies in Gozzi's Turandot ,

Berlin, 1927. From Emil Pirchan, Harald Kreutzberg (1941), plate 20.

Figure 56.

Vera Skoronel. Photo

by Suse Byk, from RLM, plate 39.

Figure 57.

A scene in Skoronel's Tanzspiel , 1927. Photo by Suse Byk, from RLM, plate 43.

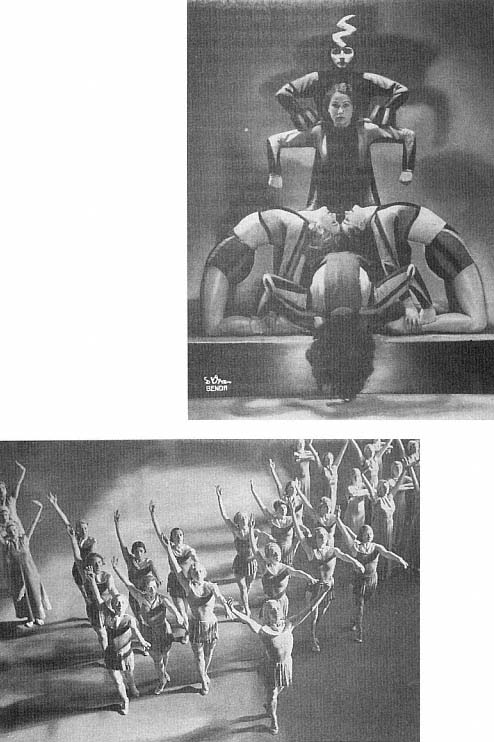

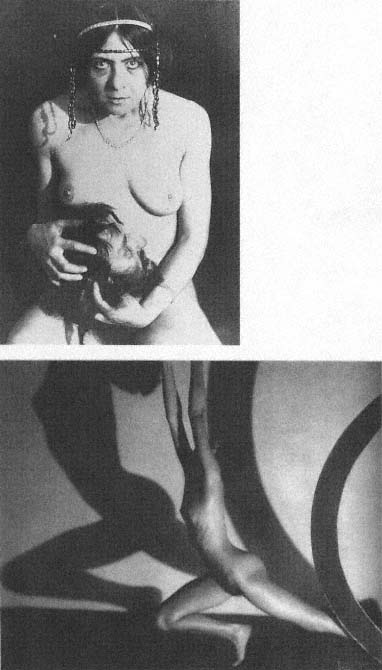

Top: Figure 58.

Scene from Hertha Feist's Die Berufung , Berlin, 1927–1928.

Photo by Suse Byk, from RLM, plate 5.

Bottom: Figure 59.

Unidentified dance performed by students of Jutta Klamt, Berlin, ca. 1928.

Photo from the Joan Erikson Archive of the Harvard Theatre Collection.

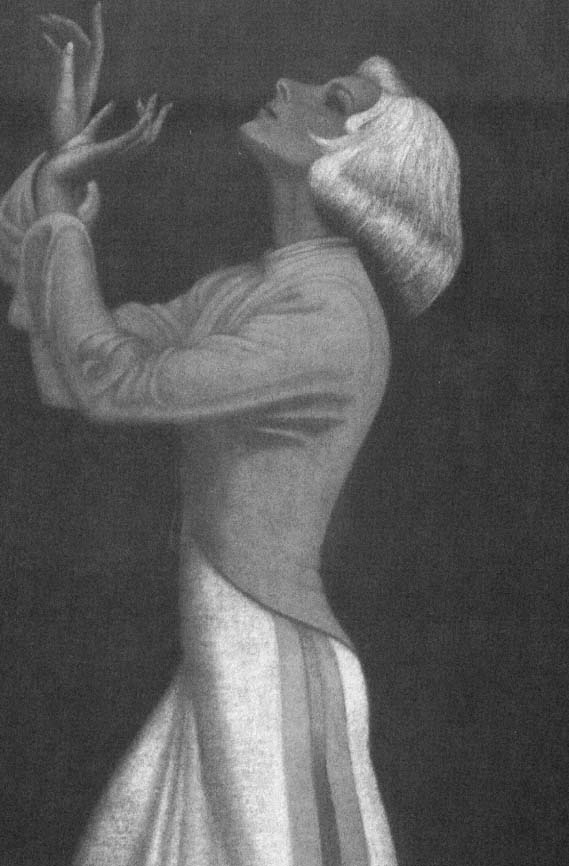

Top: Figure 60.

Gertrud Bodenwieser's Dämon Maschine (1924).

Photograph by D'Ora Benda, from Faber, Tanzfoto (1991), 69.

Bottom: Figure 61.

A Scene from Lola Rogge's Amazonen (1935), with Gerti Maack,

as Penthesilea, leading the Amazons. Photo by

Estorff-Volkmann, from Stöckemann, Lola Rogge (1991), 88.

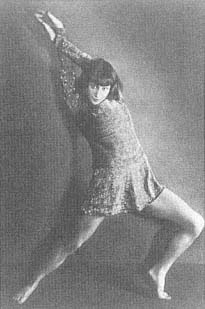

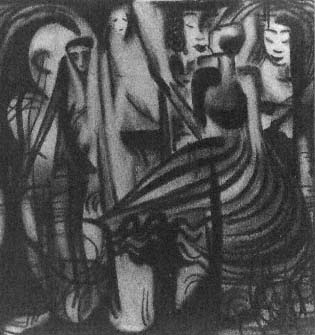

Figure 62.

Convoluted configuration of group movement, with individualized

bodies of group members, in Margarethe Wallmann's dance drama

Das jüngste Gericht , Salzburg, 1931. From the Theatre Collection of Cologne University.

Figure 63.

Mass movement. Students from the Margarete

Schmidts school in Essen, 1927. From RLM, plate 64.

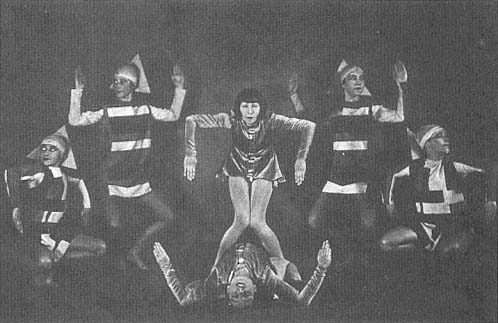

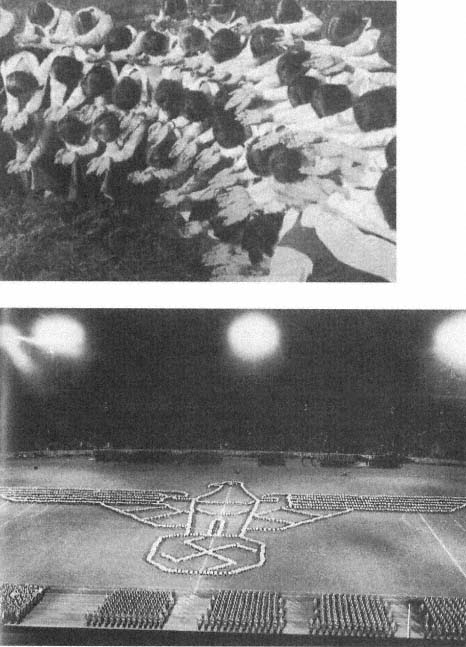

Figure 64.

Image of ecstatic mass movement in the Flemish massatooneel.

Tota Pulchra es! , Moorslede, 1935. From Jozef Boon,

Spreekkoor en massatooneel (1937).

Top: Figure 65.

Flemish mass movement. Het werk onzer handen!, Antwerp, 1935.

From Jozef Boon, Spreekkoor en massatooneel (1937).

Bottom: Figure 66.

Spectacle celebrating "Berlin in seven hundred years of German history"

at Olympic Stadium in Berlin, 1937. From the Theatre Collection of Cologne University.

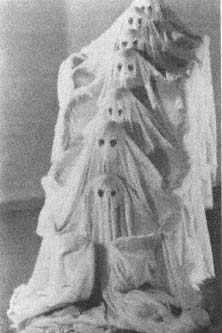

Figure 67.

An example of Jaap Kool's effort to integrate movement

notation with music notation, here for a dance by

Grit Hegesa. From Kool, Tanzschrift (1927), 24.

Figure 68.

The "shadows" section of Mary Wigman's Der Weg (1932).

Photo by Albert Renger-Patzsch, from MWB 83.

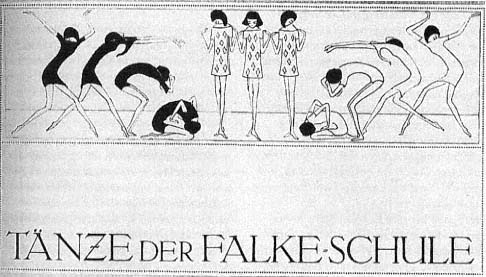

Figure 69.

Poster designed by Ursula Falke announcing dances performed by students

of the Falke sisters' school in Hamburg, 1917, from Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe.

Figure 70.

A woman dancing while wearing glasses. Expressionist

painting by Hugo Scheiber, Berlin, ca. 1928, from Darany,

Hugo Scheiber. Leben und Werk (1982).

Figure 71.

Erika Vogt. Painting in "Neue Sächlichkeit" style by Fritz Uphoff, Worpswede, 1930,

from Küster, Kunstwerkstatt Worpswede (1989), 159.

Figure 72.

Luise Grimm's woodcut Tanzszene, Berlin, 1923.

From Ruthenberg, Luise Grimm (1985), 52.

Figure 73.

Mary Wigman and her dance group. Charcoal

drawing by Luise Grimm (1924), from

Ruthenberg, Luise Grimm (1985), 59.

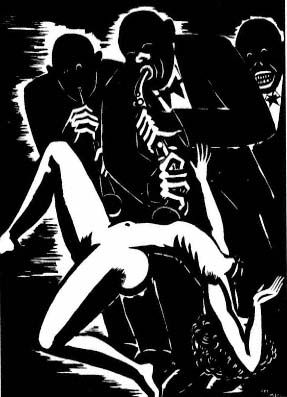

Figure 74.

Jazz (1931). Woodcut by Frans Masereel,

from Galerie Bodo Niemann, Berlin.

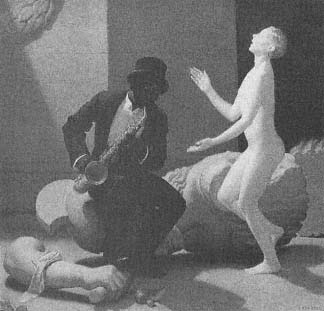

Figure 75.

The Breakdown (1926). Painting by John

Bulloch Souter, from Bourne Gallery, London.

Figure 76.

Toni Freeden cradling the steel sculpture of her

head by her husband, Rudolf Belling,

Berlin, 1925. From Nerdinger,

Rudolf Belling (1981), 205.

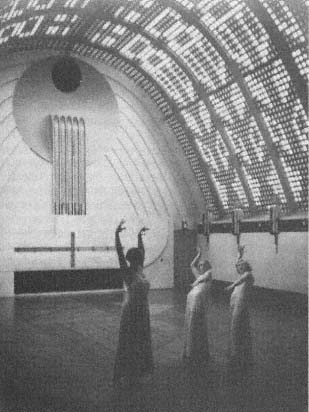

Figure 77.

Dancers rehearsing in the Himmelssaal of the

Atlantis House in Bremen, 1930.

From Golücke, Bernhard Hoetger (1982), 97.

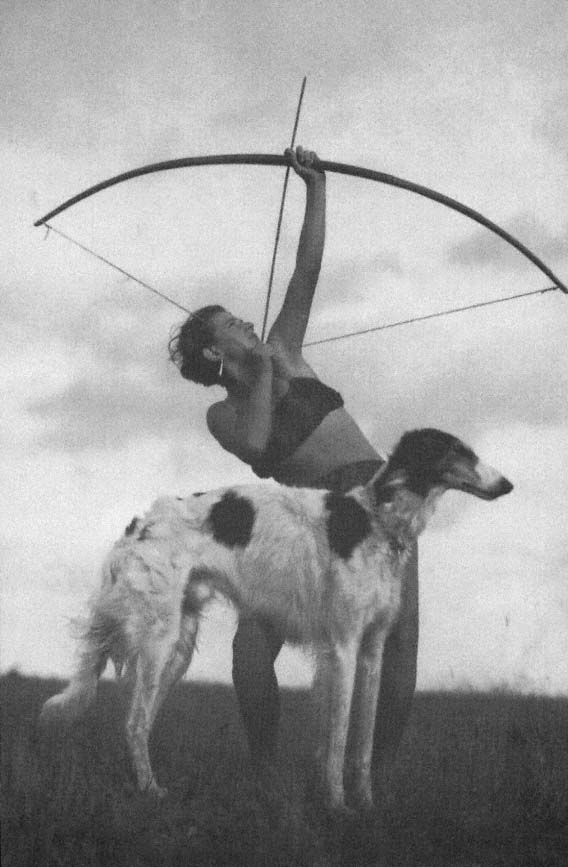

Figure 78.

An example of the dramatic athletic photography of Gerhard Riebicke, Berlin, ca. 1930.

From Wick, Hunde vor der Kamera (1989), 80.

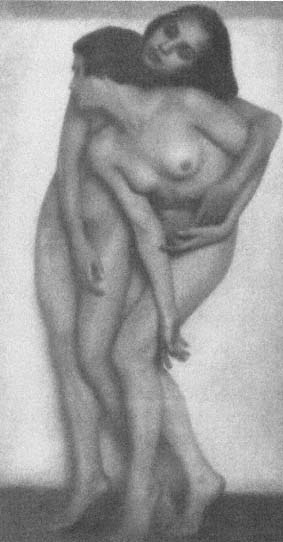

Figure 79.

Study of Russian dancers , Vienna, 1926.

Photograph by Rudolf Koppitz, from Faber, Tanzfoto (1991), 61.

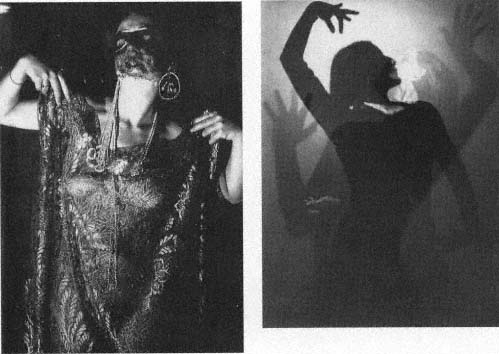

Left: Figure 80.

Experimental dance. Photograph by Marta Vietz, Berlin, ca. 1931,

from Frecot, Marta Astfalck-Vietz (1991), 21.

Right: Figure 81.

Dore Hoyer, Dresden, 1934. Superimposition photograph

by Edmund Kesting, from Galerie Bodo Niemann, Berlin.

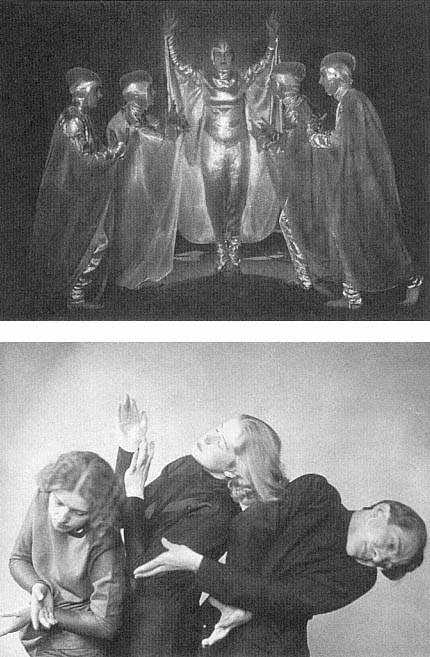

Top: Figure 82.

Olga Gzovska, performing her Salome dance, Prague, 1912.

Photograph by Frantisek Drtikol, one of a series documenting the entire

dance and published as a folio, from Museum of Applied Art, Prague.

Bottom: Figure 83.

Untitled photograph by Frantisek Drtikol, Prague, 1928.

From Birgus and Brany, Frantisek Drtikol (1988), plate 68.

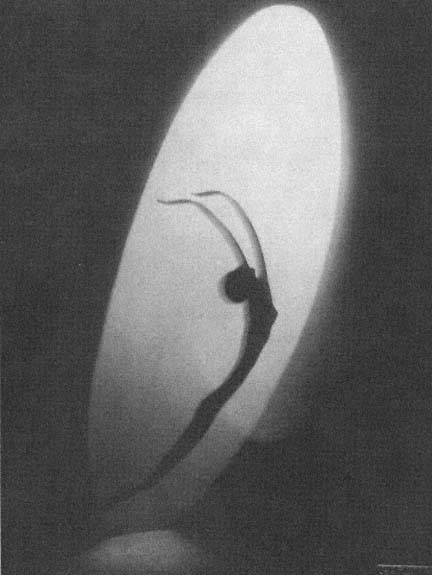

Figure 84.

Composition photograph by Frantisek Drtikol using paper figure,

Prague, 1930, from Birgus and Brany, Frantisek Drtikol (1988), plate 83.