PART TWO—

IDENTITY AND CONSTRUCTIONS OF COMMUNITY IN BANARAS

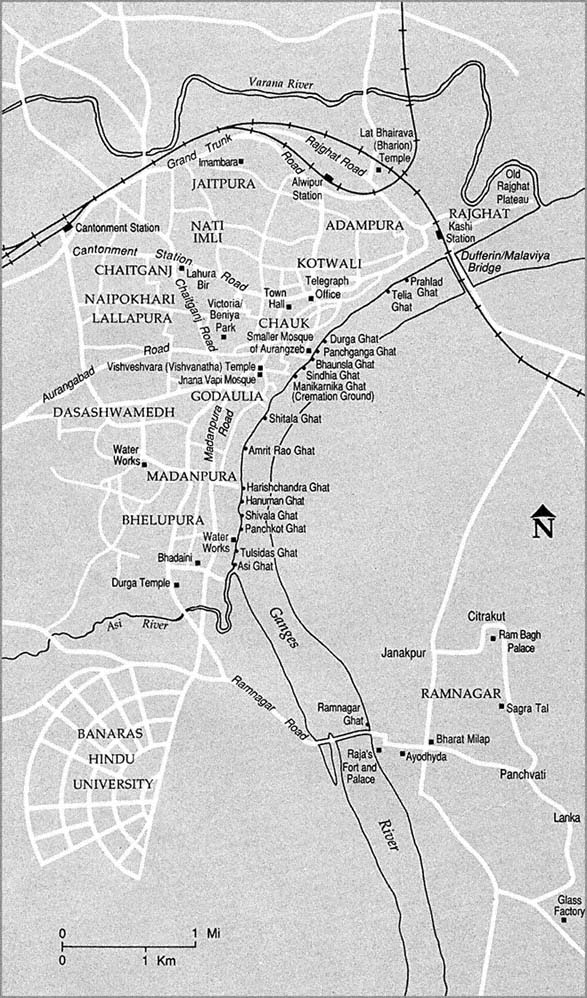

Map 5

City of Banaras. Places marked on this map are sites important in the 1890s and after.

Where necessary, they have been identified by the names used in both the British and

post-independence periods.

Introduction to Part 2—

Identity and Constructions of Community in Banaras

The following two chapters focus on local communities in Banaras. Although approaching the subject from different vantage points, they both address a process central to South Asian social history: the formation of collectivities, through the various affiliations by which Banarsis identified themselves, and the potential inherent in such formation for popular support of political, religious, and social movements. The constituent elements of this process were a series of interrelated choices made by individuals: on place of residence, means of livelihood, forms of leisure, and participation in ceremonial, ritual, and other collective activities (see map 5).

Through such choices individuals defined their own identities. Taken together, these individual actions also constituted what we may call constructions of community ("construction" emphasizes the active and largely self-conscious involvement of participants in the process). That is, in the aggregate, such actions delineated the outlines of a community by underscoring the particular affinities shared by members of the group. Given the wide variety of affinities from which urban residents might choose, such constructions could vary from moment to moment or context to context, depending on circumstances that changed often and regularly: community identity was neither static nor marked by a lineal development. Moreover, particularly in moments of conflict, residents chose to identify with particular groups often in contradistinction to an "other"; this, too, could change over time.

Conceptualization of the north Indian city as a congeries of communities whose interaction constituted the basic line of historical narrative not only is the underlying premise of this volume but also suggests the way residents of Banaras often perceived themselves. A recent biraha[*] song text collected by Marcus, for instance, chronicles the events relat-

ing to a temple theft in Banaras. Public outrage, the lyrics tell us, was expressed symbolically through a series of parades, each one representing a particular "community" in Banaras (and we might note the differing bases for identity implied by this list):

Seven big parades went and demonstrated at the chauk police station.

One day the parade consisted only of women, only of women, only of women. . . .

The deaf and dumb, lepers and beggars took out a parade; political leaders organized their parade;

Astrologers, students, and sadhus went ahead, and demonstrated at the chauk police station.[1]

The conscious choices of community affiliation made by participants thus provide points of entrée for scholars interested in the shared values and organizing principles embraced by constructed communities. These essays use as entrée variations of local identity, examining the process at its most basic units, in the small communities of occupation, neighborhood, and local belief system. There were other ways of constructing communities as well—identities that reached beyond these most localized forms. Several of these have been touched on in other chapters in this volume. Most notable, perhaps, were those of gender and that intriguingly prevalent form of association, the akhara[*] . In part to encourage further research on such subjects, we summarize briefly here what we know of these topics, before turning to neighborhood, work, and leisure—the vantage points used to view community delineation in this part.

Organizing Expressions of Identity

Generally speaking, the literature has discussed women in South Asia from a variety of viewpoints, but has not yet dealt adequately with the special place for women in Indian popular culture activities.[2] Indeed, we may suspect that, once sufficient research has been done, the "popular culture" of women may well constitute a rather different world from that presented in this volume. As Narayana Rao recently argued, this separation seems to result, in part at least, from the different emphases and worldviews of women (N. Rao 1988). Discussing the "domestic" versions of stories from the Ramayana presented in the women's quarters in South India, Rao noted that both the sections of

[1] Translation provided by Scott Marcus. [See chapter 3 for narrative "notes" interspersed by various singers in this folk song.]

[2] This may emerge as especially significant in Banaras, since the number of women there was unusually high, swelled by the widows who migrated to spend their final years in Banaras.

the narrative that are selected out for retelling, and the interpretations of behavior implicitly conveyed through these oral presentations, differ strikingly from the public (male?) versions discussed in this volume. In the women's version the heroes are not larger than life: all demonstrate typically human character flaws (illustrated by Rao in a particularly revealing scenario in which Varuna's laughter is taken by each listener as a judgment on his personal shortcomings). And in contrast to the public presentations of the epic where the action ranges across the subcontinent, the women's Ramayana, not surprisingly, presents an enclosed world both loving and tension-filled, much resembling the domestic structures of an extended family.

Another important contributor to the separation of women's popular culture from that studied here will be the fact that, in many cases, the activities occurring in public spaces, and at late-night hours, were considered inappropriate venues for women. Women did not attend the performances of street theatre described in chapter 2. They seldom constituted more than a small part of the audience for biraha[*] performances, and then only appeared in the early-morning period, when they could stop to listen on the way back from their walks to the open areas of the city for defecating. Devotion, however, lent a legitimacy to public activities, serving as a rationale for women's participation. They figured largely in temple shringar s[*] and among Bir[*] worshippers. Lutgendorf notes, too, that they not only swelled the audiences for katha[*] (in any case, a safer venue because staged "indoors"), but even figured occasionally among the exegetes.

As the biraha lyric suggests, however, women did, sometimes, even publicly mobilize to present their opinions. After marching to the chauk police station, this song goes on, they symbolically enacted their displeasure with police inaction, by presenting to the police a tray with women's "petticoats" and jewelry, thus suggesting that—since they were so ineffectual in the public world—the police might as well take on women's roles and dress.

The implications in Hess's work on Ramlila[*] , too, suggests that women did have certain, albeit specialized, places in public activity. "A large majority of the audience [is made up of] men, but many women come in the course of the month. Usually an informal 'women's section' takes shape. Women are not strictly required to stay there, but most of them do, along with the children they often have in tow" (Hess 1987:3). Most striking, many of the women observing the Ramnagar Ramlila do so at the side of the actor representing Sita[*] . During her exile, they remain with her in a remote part of the city, removed from the main drama being enacted elsewhere, for days on end (Schechner and Hess 1977:55). Clearly this reformulation for women of the very nature of public spaces, and of the nature of participation in collective activities,

will require much more work before we can understand the meaning of this specialized world of women within the urban environment.

Similarly, no systematic discussion and analysis of the structure or functioning of akhara s[*] has yet been made, although analyses specific to music and medicine point the way (see Neuman 1980; B. Metcalf 1986), buttressed by the implications of work on sannyasis and courtesans.[3] The essays in this volume suggest an outline that, while still shadowy, conveys some of the significance of this organizational form. Based on a recruitment of members who joined voluntarily, akhara s nevertheless expressed connections between members in fictive kinship and familial terms. They relied as well on variations of the guru-chela relationship to connect teachers/leaders to members/followers.

The akhara[*] form emerges as the basic unit for a number of very different activities, including "physical culture" clubs, medicine, and even the organizational structure used by mendicants, but preeminently for the organization of cultural performances—particularly in music (both classical and folk), theatre, and the mastery of courtesans over poetry, musical instruments, singing, and dancing. (For a discussion of the timing of the elaboration of this organizational form, see the introduction to Part 1.) Of these, we are most familiar with akhara s in the form of physical culture clubs, which encouraged athletic prowess in wrestling, sword and stick performances, and the like (e.g., Chandavarkar 1981; and examples cited in Chaudhuri 1951).[4] These clubs often performed during ceremonies and processions; they also could form the basis of marauding gangs during communal clashes.[5]

Akhara s[*] fulfilled other significant functions as well. The discipline of of the guru-chela relationship proved important, as chapter 3 suggests, as a method not only for perpetuating but also for controlling quality as well as the dissemination of material. It is not irrelevant that biraha[*] performers could not sing materials created by a rival akhara , or have their materials printed. Beyond neighborhood, akhara s provided a basic unit for mobilizing for collective action of various kinds; depending

[3] See especially Veena Talwar Oldenberg's essay on the forms of resistance practiced by Lucknow's courtesans, organized through a gharana[*] structure that enables them to train the next generation as well as pass property to their daughters (V. Oldenberg, 1987). Significantly, Oldenberg draws parallels between this organization and that of sannyasis discussed by Romila Thapar 1978:63–104.

[4] It is in connection with this function that gunda s[*] (urban hoods) most often became affiliated; in the workshop discussion, volume contributors suggested that the British pre-occupation with this gunda[*] connection gave akhara s and their members a bad name; yet contemporary informants assured Kumar that they regarded such skilled athlete members as "heroes," not petty criminals.

[5] Evidence is particularly strong for this role in cities with large gunda populations, such as Calcutta and Kanpur (see Basu undated; Freitag 1989).

on the eclecticism of the membership (some akhara s[*] were more heterogeneous than others, drawing members from a broader social base and geographic area), akhara s represented a potentially diverse and distinctly voluntary form of social organization. They may even, as one scholar has recently suggested, have proved particularly important as an alternative form of society for groups like women and sadhus, thus providing structures to control and use resources, as well as refuge from the world dominated by traditional social structures (Oldenberg 1987). In any case, local perceptions of such akhara s awarded them great significance. A recent essay discussing the "histories" written by its residents of an eastern U.P. qasba[*] , for instance, shows us that two of the thirteen events deemed "important" by one author involved disputes between teams of wrestlers (G. Pandey 1984:244).

If akhara s provide an important point of entrée for discussing the nexus of various cultural activities and local social organization, neighborhood provides another important avenue of analysis. Approaching the subject from one vantage point within the neighborhood, Coccari examines the muhalla[*] as a base for forming and expressing identity through worship of particular neighborhood Birs[*] . Her discussion of local deities also suggests the process, discussed by Marcus as well, by which activities originating with one caste or subcaste (in this case, Ahirs or Yadavs[*] ) become generalized to lower-class culture, thus incorporating ever-larger numbers of people. Coccari and Kumar note two important characteristics of this expansion: first, the sheer number of activities and occasions have been expanding significantly in the last decade or two. Implied by this increased activity is an elaborated and inclusive lower-class culture that gradually is laying claim to the public spaces of north Indian cities. Second, expansion of such activities has tended to take forms, such as the worship of neighborhood deities, that elicit little orthodox or upper-caste opposition. Thus it appears that a discrete world may be in the process of being fashioned, one that underscores by its very separateness the differences now perceived between upper- and lower-caste urban culture. A third point might be noted as well: the dispersion of this lower-caste urban culture through the movement to industrial centers of up-country workers, particularly weavers. Indeed, one of the more striking aspects of the work of Chandavakar (1981) on Bombay millworkers' neighborhoods, and Chakrabarty (1976) on the popular culture of Calcutta bastis[*] , is the extent to which collective ceremonial activities resemble those the mill-workers left behind them in U.P.

This would present a very different pattern from that prevalent in Banaras throughout the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century, a phenomenon examined in greater detail in Part 3. Yet there are

still, at present, some indicators of ties to upper-caste values (or, perhaps more accurately, to values shared by upper and lower castes), for these local forms of worship focus on bir[*] figures that combine warrior and saintly paradigms—a combination historically important in Banaras through the dominance of the Gosains, the group of soldier-trader mendicants discussed in the introductory essay on political economy. The meaning inherent in such symbolic public activity is, however, quite complex. Popular support, for instance, may be inferred from the wholesale audience participation by the lower castes in the Ramnagar Ramlila[*] . We noted earlier Hess's point that the messages of the Ramcharitmanas[*] are multistranded, with inherent tensions between egalitarian and hierarchical values. Such complexities doubtless enable its participants to pick and choose those they support. How this works is suggested by a conversation Hess reported with Mahesh Prasad Yadav, "one of the most deeply committed, long-time devotées at the Ramnagar Ramlila, and a member of the Yadav[*] or milkman caste (associated with the Shudra varna , though he was prosperous and highly respected)." She asked him what he thought of the Manas[*] line, "A drum, a peasant, a Shudra, an animal, a woman—all these are fit to be beaten." He replied:

I don't believe that. I am a Yadav. When people say [using an honorific], "Panditji, Panditji" to me, I say, "Listen brother, don't call me Panditji. I am a Yadav." . . . Look: karama pradhana[*]vishva kari rakha[*] [the world is based on the law of actions]—this is in the Ramayana . It is not written jati[*]pradhana vishva kari rakha [the world is based on the law of caste]. Write it down, in this one verse is all meaning. Not jati pradhana . (Hess 1987:25)

This devotée, then, simply chose from the larger whole which verses he would credit as authentic. We may assume that other participants do much the same, basing their selections on the insights they have gained by their experiences as members of particular groups with certain kinds of identities.

Hess's Yadav informant makes it clear that, in this context, his caste (jati ) identity as Yadav was important (and thus that he should not be given titles inappropriate to his station in life). So too, however, were his actions. Many of these actions would have been organized through the devotional, recreational, occupational, and residential structures of urban life. Residence—neighborhood—meant many things. In the Banaras of these essays, residence patterns in many muhalla s[*] (particularly of artisan and service castes) tended to be coterminous with occupation; similarly, caste or class affinities may have substituted as a shared basis for residence for those among the elite. Primarily because of migration patterns into a city, muhalla[ *] residence patterns also often, but not entirely, coincided with extended kinship patterns, regional and linguistic

affinities, and even natal village origins. Shared religious beliefs often followed from these other affinities.

Although in the eighteenth century the boundaries of a muhalla[*] could be traced by the actual construction pattern—that is, a muhalla coincided with a single, coterminous building (Blake 1974)—the concept evolved so that even this basic attribute could not define the functional boundaries of a muhalla later on. Instead, the boundaries of a muhalla were often perceptual, unofficial: the neighborhood did not correspond to any official unit such as "ward." At the same time, however, muhalla s[*] did have a formal role in self-government, with spokesmen pronouncing their decisions affecting taxation and organizing themselves for collective activities such as processions and neighborhood-based religious observances. Muhalla s[*] had unofficial roles as well, often channeling competition and conflict along these lines of identity. One Muslim weaver muhalla in Banaras, for instance, generally saw itself in opposition to another located elsewhere in the city: in this case, their shared occupation functioned as an avenue to channel competition—a competition in which specific neighborhood identity, instead, provided the basis for fellow-feeling (see chapter 5).

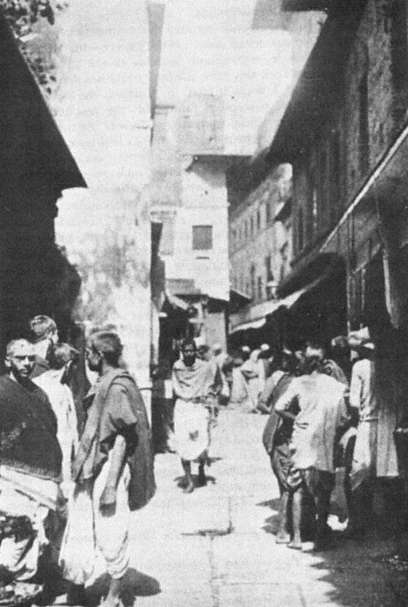

Expression of a coherent and self-conscious identity at the neighborhood level emerged particularly in leisure-time activities and in collective religious observances, as chapter 4 suggests.[6] Much associational activity featured neighborhood residents as "audience," and in connection with this role, the public space of the muhalla figured prominently. As is noted by Chandavakar, "Street life imparted its momentum to leisure and politics as well; the working classes actively organized on the street. . . . Thus, street entertainers or the more 'organized' tamasha players constituted the working man's theatre. The street corner offered a meeting place. Liquor shops frequently drew their customers[,] and gymnasiums [i.e., akhara s[*] ] their members[,] from particular neighborhoods."[7] Indeed, both Chandavakar and N. Kumar (1984) have documented the extent to which recreation for lower-class males frequently consisted simply of "roaming" the streets of the muhalla (see fig. 9).

Ritual and neighborhood identity were closely connected as well.

[6] Perhaps the most important form of identity was gender, which dictated that women's activities would be very different from those described here, since most associational activities occurred in public spaces (see chapters 2 and 3 in this volume).

[7] While the physical reality of the Bombay basti s[*] of millworkers differed greatly from the urban neighborhoods of weaver artisans in U.P., the workers in Bombay brought with them from north India certain notions about association; thus their leisure-time activities, even transplanted and characteristic of males away from their extended families, tell us something about the process by which neighborhood served as a focus for identity and collective activity. (Chandavakar 1981:606–7.)

Fig. 9

A neighborhood street in Banaras in about 1910. C. Phillips Cape, Benares, the

Stronghold of Hinduism (Boston: Gorham Press).

While some activities remained confined within the muhalla s[*] and made important statements for their occupants, many were extra-muhalla[*] in nature. These larger collective activities depended on muhalla contributions in money and manpower; examples of both types of ritual activities are examined in chapters 4 and 5.

The World of Work

Nita Kumar, too, uses a local focus to trace the overlapping identities invoked, in varying circumstances, by Banarsi weavers who are also Muslims: at what moments, she asks, do they perceive their preeminent community to be (respectively) that of weavers? that of Muslims? that of Banarsis? While Kumar and Freitag (see Introduction and Part 3) may not agree completely on the nature or context of this process of identity formation, they both recognize the centrality of the process for the social history of Banaras. From their work, in any case, it is possible to trace in outline, at least, the relationship of a particular lower-class group to an urban place and its culture, and to begin to delineate the process of identity formation and construction of community within this central-place idiom.

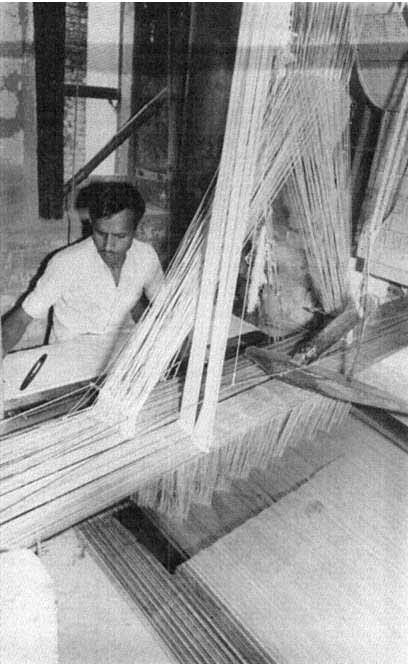

In a very illuminating contribution that could not be included here, American artist Emily DuBois detailed for the contributors the material world of the weavers that she encountered when she researched brocade weaving in Banaras in 1981.[8] Beginning with a historical summary of the changing patterns of courtly consumption, she showed us the implications of this form of patronage for the survival and relative security of Banarsi artisans. In particular, her discussion of changing styles (influenced primarily by courtly culture), and of the vicissitudes of the changing economy of weaving (affected by larger technical and economic trends) demonstrates the connections between the everyday lives of weavers and the imperial order. Indeed, the extraordinary longevity of the appeal of Banarsi brocade may go far to explain the social stability and integration of Banaras's weavers in the city's political economy. Further, we may see certain parallels in her discussion of changing patronage with the history traced in Part 1 of patronage for performance artists. That is, there is a very similar movement from the central role played by the Mughals to the importance of the successor-

[8] Emily DuBois (B.F.A. from School for American Craftsmen, M.F.A. from California College of Arts and Crafts) is a studio artist and teacher of weaving and related arts, whose honors include a 1984 National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist Fellowship. Her research of brocade weaving in Banaras was sponsored by the Berkeley Professional Studies Program in India, 1980–81, and resulted in a description of the technical aspects of the weaving published in DuBois 1986.

state courtly culture for survival of the handloom industry; from the consistent consumption patterns of Indian brides over several centuries to the new, self-conscious efforts of the independent Indian government to preserve and extend the art and skills of handloom weavers: patronage has provided the key element in the survival of the Banarsi style of weaving. Even for vast numbers of weavers who remain unaware of the role played now by the Weavers' Service Centers (N. Kumar 1984), the impact of the government on their livelihood has been far-reaching, as it has expanded foreign and domestic markets and trained personnel to manage the marketing of handloomed cloth.

Equally important has been the Banarsi context in which handloomed cloth is produced. The independence enjoyed by the Muslim weavers of Banaras has fostered a very special and individual sense of self among these weavers, who take great pride in their "freedom" and control over their work conditions, particularly, in the fact that they have been able to continue to work in their homes or in the relatively small karkhana s[*] that characterize the workplace. The description of the nature of the work provided by DuBois conveyed the degree to which weavers do control their work time and rhythm; but it also suggests the interdependent relationships they have with zari (gold-wrapped thread) producers, their women who wind the silk thread, and especially the merchants and middlemen who supply them with credit, yarn, some of the marketing outlets, and even many of the designs they use. Only by understanding this complex of working conditions can we fully appreciate the world of Banaras weavers.

DuBois's detailed discussion of the physical world and procedures of weaving provides us with a richer understanding of what identification as "weaver" meant: it enables us to connect elements of identity to the material processes in which weavers are involved daily. For that reason, we have included here the section of her essay describing that world as she was permitted to enter it (which nicely complements the description provided by Kumar in Chapter 5):

There are several areas in Banaras where brocade weavers traditionally live and work. On the northern edge of the city is a neighborhood called Rasulpura, not far from the Weavers' Service Centre in Chowkaghat. Quite different in character from the central city, Rasulpura has the character of a small Muslim village. The area lies a little apart. A dry road leads past a mosque, an expanse of open ground where men prepare the warps for their looms, then into the narrow streets and closely walled houses. In a courtyard one man sets the hooks on a jacquard box while in the balcony above several women are winding silk threads onto reels. An open window reveals a cool dark room filled completely with looms. It appears that in almost every home people are making the brocades for which this city is famous.

The loom traditional to Banaras brocade weaving is the pitloom, which is still used today. A hollow is dug into the dirt floor underneath the front of the loom. The weaver sits on a bench at floor level with his feet in the pit containing the treadles. The harnesses and other hanging parts are suspended from the ceiling, while the horizontally stretched parts are attached either to the walls or to posts built into the floor. Thus the entire room becomes the loom. In brocade weaving, two men work together, the weaver at the front of the loom and the helper or drawboy on a plank placed above the warp at the back of the loom. The jacquard and jala[*] mechanisms are attached behind the two or more standard harnesses used to weave the ground cloth.

While brocade may be woven on looms of various types, it is the jala drawloom system that makes Banaras brocade unique. The character of the design elements and their layout within the boundaries of the fabric which so readily define a sari as Banarsi, are in great part a function of the capabilities of the jala . Even when used in conjunction with the jacquard, jala is preferable for smaller motifs with 2 repeats. It is easier to design a naqsha[*] than to punch jacquard cards, easier to set up the jala and to store it, and in some ways it allows for more flexibility of design. The weaver can select the sequence (forward or reverse) and therefore the direction of the motif, and can choose to weave some or all of the repeats of the motif on the fabric. (For details on the weaving processes, see DuBois 1986.)

One home-based workshop in Rasulpura is operated by some eighty-five members of an extended family, supervised by the master weaver Anwar Ahmed Ansari, a man in his fifties who learned weaving within the family. What makes him different from most master weavers is that he received advanced training at the Weavers' Service Centre and continues to maintain business connections there.[9] As in all the weavers' homes, the weaving, dyeing and other tasks done by the men are all carried out in several loom rooms and open courtyards at ground level, while upstairs the women work at silk reeling and fabric finishing as part of their daily housework. There are eleven children from the family presently learning weaving as well as more than twenty related operations. The karkhana[*] also hires weavers from outside the family, some Muslim and some Hindu, and sometimes employs a designer/weaver who was trained at the Weavers' Service Centre. The master weaver owns a collection of brocade designs from outside sources. In addition to weaving brocade saris and yardage, this workshop occasionally takes on projects such as weaving jute and wool wall hangings developed through the Weavers' Service Centre with contemporary designs intended for export. Orders for brocades may also come through the Weavers' Service Centre as well as from private commercial sources.

According to Anwar Ahmed Ansari, two workers can produce a sari in about a week. The work is somewhat seasonal, particularly for wedding

[9] This is also, of course, a much larger operation than that engaged in by most of the weavers in Banaras. See chapter 5.

saris, but generally steady. Weaving may be done to fill specific orders or on speculation. After the sari is removed from the loom it may be given to other workers who press, size and polish it by machine rolling. Often the shopkeepers prefer to keep unfinished saris in stock, which are only polished after being purchased by the customer.

We might note that the weavers' connections to the larger world through their weaving includes more than these merchants and the producers of the materials they use. In Banaras today, designs, too, come from various sources. Master weavers may have collections of old designs or may purchase new designs from traditionally trained designers or from merchants or middlemen. The government-sponsored Weavers' Service Centre in Banaras is another important source.

Since 1952 with the constitution of the All India Handloom Board, the central government of independent India has taken an active role in revitalizing the handloom industry in India, building on the colonial government's experiments of the 1930s and 1940s. Members of the Handloom Board represent various interests including handloom weavers, exporters, cooperative banks, mill industry and central and state governments, with programs administered by the Office of the Development Commissioner under the Ministry of Industry. The programs are geared primarily toward weaving of simple cotton cloth by rural, relatively unskilled workers, the largest cottage industry in India second only to agriculture in the village economy. By contrast, Banaras brocades have always been woven by highly skilled artisans and served by specialized markets, and so were not as affected by the competition from industrialized Britain nor targeted for development by the Indian government.

While supportive schemes of the All India Handloom Board—as weavers' cooperatives, direct subsidies on production and sales, and setting up of pre- and post-loom facilities—did not directly affect brocade weaving, the establishment of the Weavers' Service Centre in Banaras has made a profound and subtle difference. Set up in 1956 by the All India Handloom Board, there are presently twenty-one Weavers' Service Centres throughout India, including the one in Banaras. The Weavers' Service Centres contain three sections: artist studio, dye lab, and weaving section; the work done in each has made technical differences in the physical processes and end results of the weaving. Once again, it reflects the impact on weavers of governmental patronage, this time suggesting an interplay between a "national" culture, and the long-lived local one of brocade production.

These discussions of neighborhood, leisure, and work patterns, then, enable us to begin sorting out upper and lower caste/class values, belief systems, and behavior in a north Indian urban setting. Within the range of approaches and subject matter presented in this part are embedded a number of important issues discussed throughout the volume. Taken together, the essays are richly suggestive of the ways in

which Banarsis use identity to mobilize for work and leisure.[10] Such mobilization, in particular, is an important subject for this volume as it demonstrates most directly the connections between popular culture and the power relationships that affected larger events in the history of Banaras and colonial South Asia. The processes and value systems expressed in the culture shared at this local level constitute building blocks contributing to the events we think of as "history," including popular values and assumptions; ways of expressing as well as solidifying constructions of community; the role of the neighborhood and other voluntary associational activity in mobilizing Banarsis for action. These building blocks will recur in Part 3, where their connections are traced to broader issues and contexts.

[10] See Preface to this volume and Eileen and Stephen Yeo (1981) for more discussion of this issue.

Four—

Protection and Identity:

Banaras's Bir[*] Babas as Neighborhood Guardian Deities

Diane M. Coccari

One can hardly walk the streets, narrow alleyways, and suburban lanes of Banaras without noticing the many small shrines that are the objects of ongoing ritual attention. Iconic and aniconic images rest on raised platforms, nestle in the roots of large holy trees, are set into the niches of boundary walls, or are housed in simple temple structures. Many of these images are familiar: the ubiquitous lingas of Shiva, representations of Ganesha, Hanuman, Bhairava, Durga, Kali[*] , Sitala Mata, the recently popular Santoshi Ma. There are goddesses with unfamiliar names (Sambho Mai, Saiyari Mai), memorials to ascetics ("Babas"), and other shrines dedicated to the memory or power of the human dead: the satis, bir s[*] and brahm s.

The Birs[*] —also called Bir Babas[1] —appear to be the most numerous among these. The city of Banaras contains hundreds of Bir Baba temples and shrines, many showing signs of recent construction or repair (see fig. 10). Once alerted to the existence of these shrines and the range of their iconography, one suddenly sees them everywhere. Extending the search to rural areas around the city, one discovers few villages that do not contain a Bir shrine that is focal for a significant part

[*] Research for this article was conducted between September 1980 and May 1982 under the auspices of the American Institute of Indian Studies. See also Diane Marjorie Coccari, 1986. Thanks to Sandria Freitag and Philip Lutgendorf for their comments and suggestions.

[1] Bir : Sanskrit vira[*] , a "brave, eminent man, hero or chief" (Monier-Williams 1899:1006). Baba[*] is a term of endearment or respect for a male family member—a son, husband, father, paternal grandfather—or of deference for an ascetic or very old man (R. C. Varma 1966:114).

Fig. 10

Lahura Bir's[*] annual decoration ceremony; wife of the pujari[*

] (officiant) fills in. Photograph by Diane Coccari.

of the population. Who are the Bir Babas, what do they mean to the Banaras people, and what is their place in the profuse and multifaceted pantheon of Banaras's deities?

Frequently dismissed by the scholarly and the lay community alike as subjects of minor importance, the Bir Babas offer a unique glimpse into the religious and social lives of a sizable portion of Banaras's Hindu population. The following will introduce the reader to the identity, iconography, and worship of the Bir Babas, and suggest what might be learned from the interdisciplinary study of these local deities.

The Bir[*] Image and Shrine

The Bir Baba images of Banaras and surrounding villages fall into four general categories: (1) aniconic mounds, cones, or posts, (2) imageless enclosures, (3) small, carved figures in bas-relief, and (4) images reconstituted from recovered, broken sculptural fragments. Among these, the aniconic mound-shapes and imageless shrines are most frequently encountered in rural settings, and the carved figures and sculptural fragments in the denser sections of the city. The ongoing process of urban expansion, however, has resulted in the incorporation of many rural-type shrines into the life of growing city neighborhoods.

The low mound or the taller, rounded cone is the fundamental form in this area of the propitiatory sthan[*][2] of the "untimely" or powerful dead, including brahm s (the ghosts of Brahmins), satis (virtuous wives who die on their husbands' funeral pyres), mari s[*] or bhavani s[*] (ghosts of females who die unnatural or untimely deaths), and the tombs or memorials (samadhis) of certain sects of ascetics. When questioned, informants invariably report the original form to be a low mound of packed clay, later remodeled by devotees with brick, clay and white-wash, metal, tile, cement, or stone. A bronze or silver mask may be attached to the aniconic form, effecting its transformation to iconic image. The Bir masks are similar in type to the city's main Kal Bhairava image (another composite of mask and rough stone), sporting royal headdresses and large moustaches typical of the South Asian warriorhero. Examples of this treatment are Lahura Bir—the namesake of a major city intersection—and Daitra Bir in Chait Ganj, said to be the younger brother of Lahura Bir. It is interesting that the mound or postlike images, even without anthropomorphic characteristics, are approached in worship as though they were a human frame: they are garlanded and the "feet" are pressed.

The small, imageless enclosures are understood to house the spirit of the Bir and provide a platform for offerings. These miniature templelike structures are often associated with large old trees (many the sacred pipal, bel , or nim[*] ) which may lend the figure its name, as Pipala Bir in Bari Gaivi, or Belawa Bir in Shankudhara. The proliferation of small shrines and images among the roots of sacred trees can be viewed as an expression of the underlying cultural conviction that trees themselves are venerable or are the proper abodes of godlings or spirits (yaksa s[*] , yaksi s[*] , daitya s, etc.) to whom the shrines are built to honor and placate. Many of these shrines house a Daitra Bir (from the Sanskrit daitya ), wit-

[2] Hindi sthan and Bhojpuri asthan[ *] derive from the Sanskrit sthana[*] , a "place, spot, locality, abode, dwelling, house, site" (Monier-Williams 1899:1263). These may also be called devasthan[*], bhutasthan[*] , or birasthan[*] , depending on the nature of the being believed to reside there.

ness to the continuity of this older tradition. Popular explanation of the association of shrine and tree often points to the accidental death of a climber. Tar Bir[*] on Lanka Road (tar[*] , a palmyra palm) is said to be a toddy-tapper (Pasi) who died in such a fall.

The majority of the carved Bir images are small bas-relief plaques depicting standing figures with an axe or a club in the right hand and a water pot (lota[ *] ) in the left. Newly carved or painted images reveal details obscured in the older images, such as beard and topknot, loin cloth, sectarian markings, and beads. Daitra Bir near the Women's College of Banaras Hindu University campus, the newly established Daitra Bir in Nawab Ganj, Sahodar Bir near the Assi Nala, Anjan Bir in Assi, Panaru Bir near Laksmi Kund, and Kankara Bir in Shankodhara are among the many examples of this type. Some, like Naukare Bir, next to the city's main Durga Temple, or Akela Baba on Banaras Hindu University campus, are seated in the lotus posture with weapons in hand. These Bir images, of a "martial ascetic" type, are nearly identical to those associated with small neighborhood samadhis (tombs) of ascetics throughout the city. The images of Macchodara Nath Baba in Macchodara Bag and of Mishra Baba on Luxa Road—both described by devotees as accomplished yogis—invite this comparison. While a number of Banarsi murti[*] sellers admit to offering this generalized type of image to patrons wishing to establish an ascetic's samadhi or the sthan[*] of a Bir or a Brahm, the conflation of elements of heroic and ascetic traditions is clearly at the root of these imaging practices. There is a great deal of similarity in the role these small shrines play in the lives of city neighborhood dwellers.

The broken images, often discovered during construction projects or fished out of the Ganges, are another kind of solution to the representation of a Bir's human form. The appearance of the fragment determines the iconography and occasionally the figure's name as well. Nangan Bir ("Naked Hero") of Bhadaini has the body of a Jain Tirthankara, and the well-known Mur Kata Baba ("Head-Cut Baba") on Durga Kund Road is a decapitated sculpture of, many think, the Buddha. These found images are said to be ancient deities who "reveal" their location to favored individuals in a vision or a dream, or emerge into the light of day under their own power (murti apne ap[*] nikli[*] or apne ap prakat hui[*] ). This revelation is evidence of the deity's renewed vigor and is itself the legitimation of the image's establishment and worship. The original identity of the piece is unknown and unimportant, as is the shastrik[*] convention that prohibits the use of a badly mutilated murti .[3] What is authoritative is the revelation of the image and the

[3] "If an image is broken in parts or reduced to particulars it should be removed according to shastrik rules and another should be installed in its place" (Kane 1973, 4:904).

subsequent proofs of power and efficacy the deity is believed to exhibit. Some Banaras Bir[*] images are said to have been established by Brahmin priests with the proper pratistha[*] ceremony, but most are set up by non-Brahmin priests or their finders with a simpler ritual dedication.

Several processes are at work, then, in the creation of Bir Baba shrines: a propitiatory sthan[ *] is established and worshipped in order to quiet the "untimely" dead, or a preexisting shrine is incorporated into the religious life of a new neighborhood; an older presence—often associated with a large, sacred tree—is given new life as a Bir Baba, or broken images from a former era are found ("revealed") and established by their finders.

The Identity of the Birs[*]

The most critical distinction in the Birs' ontological status involves their classification as "ghosts-spirits" (bhut-pret[*] ) or "deities" (devata[*] ). Some Banarsis maintain that the Birs are beings of the pret yoni , the "birth as a ghost," a painfully liminal condition which is neither of the gods, ancestors, or humanity. These ghosts or spirits suffered violent, unnatural, premature, or "untimely deaths" (akal[*]mrityu ), which rendered them unqualified for the normal rites of death, or incapable of being advanced to the world of the ancestors (pitri lok ) and beyond. Angry, jealous, and seething with unfulfilled desires, the ghost has no recourse but to harass or otherwise persuade the living to offer the desired attention. A ghost may appear to an individual in a vision or a dream, cause illness and other misfortune, or take active possession. People bothered in this way may seek the help of a professional exorcist (ojha[*] ) to remove or transfer the spirit to another individual or location, or perform rituals of appeasement, including the creation of a shrine to "quiet" (shanti[*]karna[*] ) the spirit.

Although the stories of most Banaras Birs are of untimely and violent death, the people who worship the birs[*] consider them "gods" or "deities" and not mere ghosts (ham devata mante[*]hai[*] —"We believe they are deities"). A bir's[*] power is generated by a violent and tragic death, channeled and transformed by the ritual establishment of a shrine, and further enhanced by worship. The bir is distinguished from lesser spirits because he is the powerful "master" (malik[*] ) who controls the supernatural activity within a particular domain. Birs are believed to be especially "awake" (jagta[*]hai ) among the local gods, and active in the fulfillment of human desires.

In addition, Bir worshippers take the vira[*] ("hero") part of the deity's description quite literally: most reported the Birs to be heroic "martyrs" (shahid[*] ) who sacrificed their lives in defense of family, friends, caste group, village, or religion. "Anyone who dies on the bat-

tlefield is a Bir[*] " is a repeated refrain. Many of the Banaras Birs[*] are said to have died at the time of the Mahabharata[*] war, in battles among regional, historical chieftains, fighting the Muslim armies of Aurangzeb, the English army of the Raj, or in more recent altercations with local enemies. While most of the Bir stories continue to be flavored by the bhut-pret[*] complex or a more archaic and local brand of heroism, an attempt is made to relate these events to wider and more universal values. Even if the circumstances surrounding the death of a Bir do not at first glance appear particularly heroic, the teller will expand upon the exceptional qualities of the individual or emphasize that the hero was tricked, outnumbered, or otherwise overcome by fate in order to be killed. The Bir's physical strength and size, leadership ability, bravery, fighting and wrestling prowess, loyalty, self-sacrifice, and devotion to God are extolled.

One example of righteous conflict and untimely death is the story of Bachau Bir, whose temple lies in the village of Sir Karhiya just outside Banaras Hindu University campus. Bachau's story is widely circulated in the Banaras area, assisted no doubt by the existence of a biraha[ *] song detailing the climactic events that resulted in Bachau's violent death. Bachau, an Ahir by caste, was a historical individual who lived in the early part of this century. Legend has it that his extraordinary strength and bravery were matched by honor and compassion. He was famous for saving the life of a village headman by killing a jungle tiger with his bare hands. Yet Bachau had many enemies, especially among the local Thakur caste. A dispute over land rights ignited this long-standing rivalry, and Bachau, who refused to bring a weapon to a confrontation with his enemies, was outnumbered and beaten mercilessly to death. The biraha song, written by an Ahir songwriter, concludes with the hero's ascension to Heroes' Heaven (bir[*]gati ) immediately upon his death (Coccari 1986:185–89, 249–52).

As was indicated above, the figure of the Bir is easily conflated with that of the entombed ascetic. The association of virility and asceticism is ancient on the subcontinent, and we are offered many examples—both mythic and historical—of warrior ascetics, yogis who become physically powerful as a result of ascetic observances, and heroes whose physical might implies disciplined spiritual attainment or "saintly" characters. There are Bir Babas in the Banaras area—such as Jog or Jogi Bir of Narayanpur village—who are described as yogis who met with violent ends, and others who achieved perfection as a result of the Tantric vira-sadhana[*] , the dangerous and empowering "Hero's Path." Both Bir and memorialized yogi are addressed as "Baba," their shrines—containing a mound or "martial ascetic" image—are nearly identical, and both are thought to be present and available to worshippers at the tomb or temple location. The nature of the presence of a Bir and an

entombed ascetic are theoretically distinct—the Bir[*] a deified ghost and the yogi in an immortal body or a disembodied consciousness—but this makes little difference in the outcome of worship of either figure. Both are petitioned by worshippers for the fulfillment of desires and relief from illness, misfortune, and infertility. The shrines are identified with particular neighborhoods or social groups and are publicly celebrated by these patrons in similar ways.

The Birs[*] are said to derive from any (especially low) caste, such as Teli, Pasi, Nat[*] , Bhar, Khatik[*] . Yet it is the Ahir caste, whose traditional occupation is keeping and breeding cows and buffalos and marketing their milk, who are most consistently identified with the Bir phenomenon. Typical of pastoral groups (see Sontheimer 1976) and because of the profession of cattle keeping and herding and the related activities of cattle raiding and protection, the Ahir possess an authentic heroic tradition in which they cherish a view of themselves as brave and mighty warriors and leaders among a collection of allied castes with whom they are found in village settings. This self-image is vividly portrayed in regional versions of the centuries-old Ahir oral epic Loriki[*] (see Pandey 1979, 1982; Kesari 1980; Elwin 1946:338–70; Grierson 1929:243–54) and in more recent evidence in the pronouncements and programs of the Yadav[*] movement.

The epic world of the Loriki is one of many small kingdoms—Ahir, Rajput, and Aboriginal—vying for cattle, land, women, and power. It is a world in which the Ahir stand as equals to the "twice-born" warrior castes, where marriage by capture is the norm, and expressions of strength, bravery, loyalty, nobility, and honor are valued. Like many other epic traditions, it is a story of a flawed hero (Lorik) who meets with a tragic fate. Episodes of the Loriki are localized in the various regions that know the epic, and it is viewed—especially by rural Ahir—as a caste history to which many of their distinctive customs can be traced. The hero Lorik himself is seen as a historical hero of great stature and the Ahirs' most illustrious ancestor.

More sophisticated and urbanized Ahir eschew any connection with the Loriki and other rustic caste traditions, including wrestling (popular among the Ahir) and the singing of biraha[*] . These Ahir elites, many of whom support the Yadav movement, are anxious to distance themselves from the more archaic expressions of caste heroism in favor of Brahminical symbols and genealogical "histories" proving descent from the Yadu dynasty of Krishna. The Yadav movement has sought, among other things, to establish the Ahir as a bona fide martial race. The movement was launched during the turn of the century by the rulers of the royal state of Rewari, members of the Yaduvamsi[*] subcaste of Ahirs. The teachings of the Arya Samaj[*] were impetus to the growth of the movement, which adapted these to its own agenda of caste uplift

and political organization. In particular, many Ahirs adopted the "twice-born" symbol of the sacred thread in support of their claim to Kshatriya status. The Janeu[*] (sacred thread) movement was strong in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the 1910s and 1920s, and encountered opposition from powerful Thakurs and Bhumihar Brahmins (Rao 1979:134). Many Ahirs adopted Yadav[*] as a last name, and it soon became a reference category that served to associate many diverse regional cow- and buffalo-herding castes throughout the subcontinent. More recently Yadav organizations have agitated for a separate regiment in the Indian army, as have the other "martial races" of India (Rao 1964). Yadavs[*] have played leading roles in recent decades in "backward class" associations (Rao 1979:157–58).

In both the Loriki[*] and the Yadav movement we find expression of an Ahir heroic tradition, reflected also in the large number of shrines to deified Ahir heroes and their reputations as powerful guardians. The relatively high percentage of Ahirs in Banaras and surrounding districts may also help to explain the predominance of these shrines.[4] Unlike many caste groups in other regions of India (see, for instance, Blackburn 1981), the Ahir from the Banaras area—primarily worshippers of the Goddess and Krishna—do not center their religious life entirely around these deified caste figures. The Ahir Birs[*] do not necessarily become the foci of elaborate and organized cultic activity that reifies caste or clan identity or that represents a system of ancestor worship. It is possible that caste heroes played a more central role in the religious life of the Ahir in the past, and that the upwardly mobile aspirations of this caste and the Yadav movement's opposition to "local deities" have taken their toll. Yet the Ahir deities retain a certain stature among other low- to middle-ranked castes of the locality, and will often be adopted by them. A neglected image will be taken over by another caretaker, a revelation of special power will rekindle worship, an older shrine will be incorporated into a newly formed neighborhood. In this way the Ahir Bir[*] shrines of the Banaras area may move out of Ahir control to become the gods of all (especially lower) castes who possess great faith in the vigor and attentiveness of these beings.

Birs as Village Guardian Deities

In the countryside around Banaras (see fig. 11) the word for the village guardian deity is dih[ *] , used interchangeably with variants diha[*] and dihwar[*] . These are generic terms that signify the guardians or protectors of the entire village unit and do not refer to village deities in general,

[4] In 1931 the Ahir made up 12.5 to 25 percent of the total population of Ballia, Ghazipur, and Jaunpur districts, U.P., and Shahabad district, Bihar (Schwartzberg 1978:106).

Fig. 11

Karman Bir[*] (one of two), Banaras Hindu University campus. Photograph by

Diane Coccari.

many of which are perceived as guardians of more specific functions or smaller social entities. A dih[*] will often have a proper name, in which case a villager might say, "This is Karman Bir. He is the Dih Baba of our village." It appears that the term dih derives from the Persian deh or dih , meaning a town or village (Johnson 1852:585), but in the Indian context the word took on the semantic dimension of "haunt, the site or ruins of a deserted village, the dwelling place of the ancestors, a heap of earth or mound, the place where worship of the village gods takes place," and simply "village gods (gram[*]devata[*] )."[5]

The designation Dih[*] (Diha[*] or Dihwar[*] ) is most frequently used for the male guardian, or Dih Baba, but it may also refer to the female guardian or to the guardian pair, understood either as husband and wife or as two separate deities associated only in their role as protectors of village boundaries. Occasionally the female guardian will be referred to as Dihwarin[*] , a feminized form of Dihwar. This is true of the city's

[5] "dih- Haunt, place, dwelling, village, site of a deserted village. diha[*] - Heap of earth, mound, bank" (Platts 1960:576). "dih m. [Hindi] 1. habitation, settlement 2. small village 3. the ruins of a deserted village 4. mound 5. the place [sthan[*] ] where worship to the village gods takes place 6. the dwelling place of ancestors" (Sundardas 1965, 2:472 [my translation]); "3. village gods [gram devata ]" (Sundardas 1965, 4:1954–55).

Lahura Bir[*] Baba and his partner, Sitala Mata. A division of labor exists between them in which the Devi checks or manifests her afflictions (if she is a disease goddess) and the Dih[*] Baba controls other, more vaguely defined supernatural forces that influence the health and wellbeing of villagers. The Dih's partner may also be a more benevolent village goddess—a Sati or a related figure—sometimes said to be his wife. With either type of goddess, however, the Dih Baba appears to retain ultimate control; even Sitala must have permission before her anger (devi[*]ka[ *]kop ) may be loosed upon errant villagers.

Thus "Dih Baba" nicely expresses the guardian's identity with its village, as well as with its origin as mound deity—the enshrined remains of an ancestor, defender, or even human sacrifice ritually compelled to protect the village and thereby actualizing its existence as a sacred entity. What is suggested by the dictionary meanings of dih[*] corresponds perfectly with the statements made by residents about their village guardians: these deities were once living members of their community, now valorized as ancient heroes associated with a village's dim beginnings. The village Dih is said to be an "ancient" (pracin[*] ) deity whose shrine was established when the village itself was founded. What helps define a village as such is the existence of its guardian deity or deities, who control the ingress and egress of all supernatural forces and influences across village boundaries. Village people use the following expressions to describe the Dih Baba's function as guardian: he is the "village protector" (gaon karaksa[*]karne[*]wala[*] , raksak[*] or rakwari[*] ), the "head" of the village (malik[*], mukhiya[*] ), the village "police chief" (kotwal), or—by those familiar with the Sanskrit term—the "area or regional guardian" (ksetrapal[*] ). The Dih, as "head" of a village, performs similar functions to those of the human official, except that his realm of authority extends to minor village deities, ghosts, other more vaguely defined magical energies, and—by extension—those humans who would wish to manipulate these beings and forces. Any human act that attempts to propitiate, exorcise, or otherwise control the supernatural must begin with the Dih's permission and blessing, or the "work" cannot succeed.

Yet because the deity is ambivalent in character, one is not always assured of the desired results. One individual explained the Dih's authority in the following way:

Before any work begins, one must worship the village Dih. Every village has one Dih. The Dih must first give permission. A ghost must also ask the Dih's permission to enter the village. If the Dih is happy with you, he will not allow the ghost to enter the village. But sometimes the Dih will "eat" the offerings and still allow the ghost to enter the village.[6]

[6] Personal interview with Bhagat Channu, Adityanagar, Dec. 11, 1980.

Likewise, when the installation of another deity is to take place in the village or the home, it must be accomplished with permission from the Dih[*] Baba. At the time of a village wedding, part of the worship of all important family and village deities by the couple includes offering the ceremonial thread (kangan ) or the groom's headdress (maur ) at the shrine of the Dih. At the birth of a child—especially a son—offerings will be made at the shrine. Similar rituals are performed when a special desire has been fulfilled by the guardian deity (see also Planalp 1956:190–91). The Dih is ideally worshipped by the entire village once or twice a year, but human nature and village politics may make this difficult to accomplish. If this neglect results in misfortune, disease, or disaster for all or part of the village, special ceremonies must be conducted to correct this lapse in ritual responsibility. In 1982 the village of Kojawa, immediately flanking Banaras, collectively worshipped its Dih when great hardship was caused by monsoon floods.

In India it is not uncommon for vira[*] types of deities, including pan-Indian mythological figures and deified local or quasi-historical martial heroes, to function as village guardians. Local manifestations of the "Monkey God" Hanuman, Bhairava, or the powerful Pandava Bhima or Bhimsen are examples of the first; martyred Muslim generals, warriors of a bona fide Hindu martial caste, tribal chieftains, or other local figures who attained the status of "hero" before or after their deaths are examples of the latter. As deities, the once-living vira s[*] continue their rightful occupation after death; those who ruled and protected while living are expected to continue this service in exchange for the honor and worship of the local population. The hero is empowered as a deity through martyrdom and sacrifice; this abundance of power is then channeled by worship to serve the living.

Consistent with this, in many of the villages immediately surrounding the city of Banaras, a Bir[*] fulfills the function of male guardian deity, or Dih Baba. These Birs[*] are valorized by believers as courageous leaders and fighters, as individuals who championed the powerless. But even without these overtly martial overtones, the Birs clearly fall within the tradition of the "mound deity" described earlier, the original ancestor or martyr ritually enjoined to the protection of the living. There are also rural Birs that do not function as Dihs[*] but remain family, lineage, clan, or caste deities, still identified with those groups who originally established the shrines. Others are village deities of more specialized function, such as protectors of fields and livestock. By contrast, in the city of Banaras, the identification of Dih and Bir is almost complete: every Dih this writer surveyed was a Bir, and almost every Bir was reported to be a Dih of some area, however small.

The Banaras City Neighborhood Guardian

The urban counterpart of the village guardian is the Banaras neighborhood Bir/Dih[*] . This urban Dih[*] , often but not necessarily paired with a goddess, is conceived in almost identical terms as the village guardian except that its territory is the considerably smaller and more intimate unit of the city neighborhood. This deity is described as "the god" or "protector of the neighborhood" (mahal ka[*]devata[*] , muhalla[*]ka rakwari[*] ) rather than of the village. There are hundreds of Bir/Dih shrines in the city of Banaras. Every section or minutely divided subsection of the city seems to boast its own "Bir/Dih Baba" or Dih pair, integral to that neighborhood's conception of itself as a discrete and bounded unit within the larger and sometimes intersecting official and historical divisions of the city.

Like the village deities, the urban Bir/Dihs[*] control the boundaries of their domains, especially with regard to the exit and entry of the intangible agents of illness, misfortune, and disease. They are approached for blessings as part of any major undertaking—ritual or otherwise—and are propitiated when trouble occurs. The Birs[*] are the appropriate deities to seek out if one feels harmed by the "evil eye" (bura[*]take[*] ), they are plied with the "heart's desires" (manokamana[*], manauti[*] ) of local people, and they are important to the work of ojhai[*] : exorcism and divination. People will boast of their own Bir[*] as the most powerful among the neighboring Birs with whom they are familiar. Some of the neighborhood Birs are known to all of the city residents or are seen to specialize in certain kinds of rituals or cures. Both Tar Bir of Lanka and Daitra Bir of Chait Ganj are said to cure a disease that causes the hands to shake, and the Siha Bir shrine—across the river in Ramnagar—is famous among the villages and neighborhoods on the south side of Banaras as a place where ojha s[*] perform tantric ritual.

These guardians are often conceived in very personal terms. The neighbors of Nangan Bir in Bhadaini refer to the deity as their "son-in-law" (damad[*] ). Many Birs are said to have a special fondness for children. Neighbors talk of their guardian's love of children, and the shrines are often a place where children as well as adults congregate. An elderly neighbor of the Anjan Bir shrine in Assi related how he, as a frightened child, was guided home safely by the Bir Baba. If one merely invokes the name of the guardian deity, it is said, he will dispel all fear and see to the safety of the traveler. It is told how a neighborhood Bir would help laborers carry their heavy loads when they stopped to rest near the shrine. The Bir is especially active at night. He patrols the boundaries of his district, wrapped in a black blanket, visiting and smoking ganja with neighboring Bir friends and brothers. If

one listens carefully, one may hear the hollow sound of his wooden sandals (kharau[*] ) on the cobbled alleyways of the city. The Bir[*] shrines of the city are often associated with a large shade tree under which people may congregate. Many shrines in open areas of the city have a water tap and a small wrestling or exercise ground.

Worship of the Birs[*]

The lower end of the caste spectrum makes up the largest portion of Bir worshippers, from middle-ranked herdsmen, agriculturalists and artisans, and groups of aboriginal ancestry, to those considered "untouchable" or Harijan. These include Ahir, Gaderiya[*] , Kunbi[*] , Kurmi, Kumhar[*] , Mali, Pasi, Bhar, Rajbhar[*] , Kol, Gond, Manjhi[*] , Mallah[*] , Khatik[*] , Teli, Dhobi, Dom[*] , Chamar, Rai[*] Das[*] , and so forth. A small percentage of middle- and high-caste members, including Brahmins, are devotees of particular Bir Babas as well. This is especially true of older community shrines that house venerable local deities viewed as protectors of all rather than identified with particular castes or occupational groups. The uneducated are most numerous among Bir worshippers, but the reputation of certain shrines may draw considerable attendance from the ranks of the educated, including the more Westernized middle class.

Women are equal in number to men among the devotees, although they are less likely to hold priestly roles. The faith of women in Bir Babas is displayed most dramatically during the large religious fairs (melas) of regionally famous Birs, when female pilgrims attend in the tens of thousands and far outnumber the men present. This may be witnessed at the annual melas of both Bechu Bir (near Aharaura, Mirzapur) and Kedariya Bir (outside the city of Jaunpur). Fertility ranks high among female concerns, but many come also to work through or be relieved of ghost affliction.

Worshipped chiefly by the neighbors of a shrine, the urban Birs are attended most frequently on Tuesdays and Sundays and during seasons of festival activity. Individual petitioners approach the Birs privately with their special needs or desires (manauti[*] ) with an initial offering when the deity is confronted with a request, and a vow (manauti manana[*] ) to perform further services or ritual offerings if a wish is fulfilled (manauti puri[*]ho jana[*] ). The requests are familiar: the cure and prevention of illness, help with family problems and disputes, aid in finding a lost object, removal of the obstacles to fertility, the finding of a job, success in a court case or in the outcome of an exam. A supplicant will salute with folded hands (pranam[*] ) or prostrate before the image, and offer sweets, flowers, incense, and dhar[*] : a "cooling" mixture of

five dried and powdered fruits mixed with Ganges water and poured from a lota[*] before the image. Substances of a more tamasik[*] quality are also acceptable to the deity: camphor, cannabis, liquor, cut nutmegs or lemons (the simulacrum of blood sacrifice), and the slaughter of cock, pig, or goat. These latter substances are considered more potent and dangerous, and are offered by those who subscribe to "tantric methods" (tantrik paddhati se ) of pleasing and coercing the deity. The Bir[*] Babas are said to accept these offerings (literally to "eat" them), and are especially fond of ganja, which is smoked frequently by men in the vicinity of some shrines. Numerous among the private petitioners are the healers and exorcists (ojha[*], sokha[*] , guni[*] ) who depend upon the cooperation of the Bir Babas in their dealings with the spirit world.

It has become very popular of late to organize a varsik[*]shringar[*] , an "annual decoration" ceremony in imitation of the annual festivals of the city's major temples. The small shrines are whitewashed, painted, and elaborately decorated with flowers and strings of electric lights; arati[*]puja[*] , all-night performances of folk and devotional music, and even martial competitions among some of the city's wrestling akhara s[*] are financed by neighborhood donations. Kumar notes an upsurge in the number of shringar s[*] of small neighborhood shrines in recent years, evidence of the increasingly popular nature of public celebration (N. Kumar 1984:200–210). The annual shringar s of Bir temples are foremost among the occasions to celebrate neighborhood identity.

Protection and Identity

The Bir shrines of the city of Banaras are in one sense a transposition of a rural deity onto the urban environment; in the role of Dih[*] Baba the Birs[*] are a projection of the idea of the bounded, guarded microcosm of the village onto the city neighborhood. This is not to say that Kashi—the ancient name of Banaras—is lacking in guardian deities, but that the Bir Babas are an additional set of these. Diana Eck has ably described the classical mandala of protective deities of the city of Banaras—the Ganeshas, Bhairavas, Devis, Yakshas, and so forth, which guard the borders and regions of the sacred city (1982:146 ff.). The Birs complete this complex mandala of guardianship; they are the protectors of even more minutely divided and subdivided bits of inhabited territory—the most personal, immediate, and responsive among the guardians of the microcosm. The establishment, worship, and celebration of Bir shrines is eloquently expressive of the need of people in the growing and ever more densely crowded city environment to continue to remap and redefine the boundaries of where they live, carve an or-

dered space out of the city's chaos, and protect that intimate space through the worship of a boundary deity.

Some of the urban shrines are clearly the foci of identity for specific social groups, if not of attempts to establish an alternate power base or resistance to traditional authority. When a neighborhood Bir[*] shrine is relatively old, it is more likely to be viewed with fondness and respect by all of the local residents, regardless of caste. These deities might be viewed by the upper castes as legitimate, albeit minor gods: the "watchmen" or "servants" (chaukidar, chaprasi[*] ) of the major deities. Yet a large portion of the shrines surveyed in Banarsi neighborhoods in 1980–1982 were established or reclaimed within the last twenty to thirty years. These relatively recent shrines are more likely to be identified with narrower segments of the population; this is especially true in the new neighborhoods that are forming on the outskirts of the city.

As has been suggested, this vision of the neighborhood Bir/Dih[*] Babas and their consecutive domains is strongest and clearest among the lower classes. Many of these new shrines are found in low-caste neighborhoods or by low-caste people in mixed neighborhoods. Some of the shrines are the only sanctified areas in the entire neighborhood, places of worship and congregation for groups of people who may have no such location to call their own. Not infrequently a Bir temple is championed as the patron deity of a coalition of low castes, hoping to exercise their collective power to save or develop a cherished bit of ground. The Daitra Bir shrine in a small Harijan neighborhood near Nawab Ganj is one example of this process. In 1981 the Raidas caretaker told how he and other neighbors cleared the area and established the small shrine of the Bir in an effort to improve their neighborhood and resist the ownership claims of a local landlord. In a similar way a local group may attempt to enhance its prestige or foster its political interests by sponsoring the building of a new neighborhood Bir temple, or an occupational group will patronize a temple near the workplace. Many of these newer shrines are the objects of ongoing litigation by way of determining land rights and ownership. These sorts of tensions are typical of the politics of newly constructed or activated shrines, a frequent occurrence in this rapidly growing city. The Birs[*] are not the only personalized neighborhood deities around which a sense of neighborhood solidarity may be built, yet the Bir Babas as territorial guardians are the natural candidates for this role.

Because they originate as the honored or powerful dead of particular communities, Birs are easily enshrined without help from the orthodoxy. Individual shrines have been ritually installed and worshipped by Brahmin priests, but this is clearly not the norm. The Birs are discov-

ered by or revealed to "small people" (chote log ) in a vision or a dream and may be enshrined by them with the simplest of ceremony. The stories of the Birs[*] themselves are of low-caste heroes and martyrs: champions of the castes from which they spring and to whom they belong. The stories of some Birs reveal the tensions between these castes and the orthodox and powerful. The Bir[*] cult displays in many respects a self-consciousness and even rebelliousness vis-à-vis Brahminical modes of worship and ritual. The participants in this tradition are proud of the fact that anyone may directly worship the Birs—even an untouchable—without the necessity of a priest or other intermediary.

The political use of these temples, as well as the challenge they represent to traditional authority, does not go unnoticed. Some point to the recent increase in wealth and political clout of members of the Ahir caste as reason for the growth of many shrines. One Brahmin pandit spoke about the proliferation of city Bir shrines as a degeneration of Dharma. He said that it was the traditional responsibility of the Raja (and now the "government," sarkar[*] ), to use his authority (danda[*] , lit., "staff") to protect Dharma. But this is no longer done. He explained that any "hoodlum" (gunda[*] ) can now establish a temple for his own purposes.[7] One need only witness the annual procession through the city of the devotees of Ravi Das—the patron saint of the untouchables—to know that there is reason for anxiety over the potential power of the organized lower classes (see Juergensmeyer 1982). Yet formal opposition to the building of a temple—a sanctified and holy place and the seat of a deity—is not offered lightly. Disputes over these small temples and shrines tend to be carried on as ostentatiously as possible in the public eye, and it is not easy for a Hindu to put himself on record in opposition to a place of worship, whether or not he concedes the stature of the resident deity. Yet in another sense, the Bir cult—associated as it is with the lower classes—may possess inherent limitations to upward mobility, something perhaps more easily accomplished outside the orthodox stronghold of Banaras. I saw no evidence of Bir Baba shrines in the process of identification with a "Sanskritic" and pan-Indian deity such as Shiva—a reasonable option considering the aniconic representations of both deities and the "vira[*] " aspect of Bhairava in the Shaivite pantheon.

Conclusion

The Birs in the city of Banaras are almost always said to be the Dih[*] Babas, or guardian deities, of specific neighborhoods, a formal expression of their identity with and patronage of a group or area. Moreover, this

[7] Personal interview with Pandit Ram Puri Divedi, Sept. 25, 1981.

urban Dih[*] Baba appears to be a projection of rural patterns of sacred geography, another example of the penetration of a rural world view with its gramadevata[*] into the urban environment in the minds of lower-caste people, and witness to the connectedness of rural and urban areas.

The appeal of the Bir[*] Babas to their worshippers has many facets: issuing forth as the deified dead of the lower classes, the Birs[*] are directly identified with those whom they champion. They are among the immanent and "awake" deities in whom people hold their faith in the degenerate age of the Kali[*] Yuga. The establishment, worship, and celebration of the shrines require no orthodox mediation; at the same time these activities are difficult to oppose overtly. The increasingly conspicuous celebration of Bir Baba shrines and the growth in the actual number of shrines is no doubt part of the trend toward lower-class patronage of public events and celebrations noted by Nita Kumar (1984), with the Birs providing a religious and organizational focus for social groups who lack other appropriate objects of patronage.

Five—

Work and Leisure in the Formation of Identity:

Muslim Weavers in a Hindu City

Nita Kumar

The most renowned and commercially important product of Banaras is the "Banarsi" sari, with a history of many millennia behind it and a working force that includes almost 25 percent of the city's population. These weavers are proud craftsmen who trace their presence in the city to anywhere between three hundred and a thousand years. They are Sunni Muslims, articulate about their beliefs, rituals, and religiosity. They refer to themselves as "Ansari" rather than by their old "caste" name, Julaha[*] , and consider the new name replete with suggestions about their character and behavior. They have no economic or social ties in the countryside or other cities, and call themselves unequivocally "Banarsi" ("of Banaras").

The characterization of their identity is not a simple task. If we begin with a consideration of them as an occupational group, that is what they primarily seem to be. If we discuss them first as "Muslims," we will find ample data to support a case for their religious or "communal" identity. They may further be labeled "urban," "lower class," the "poor," and perhaps a "closed social community." This chapter looks at different manifestations of identity, using the methods of both history and anthropology. The routine of work reveals the common elements of poverty, insecurity, and illiteracy, as well as the more positive aspects of a high level of skill and a lack of regimen in the workday, which are common to all artisans. The patterns of leisure demonstrate the common attachment to place and tradition, the practical demonstration of freedom, and the priority given to individual preference, taste, mood, and occasion in deciding the use of time. A consideration of the two—work and leisure activities—together, enables us to construct a suitably complex picture of what it means to be a Muslim weaver in the Hindu pilgrimage center of Banaras.

The Weaver as Artisan

The first thing that defines a weaver is his work. The technological dimensions of the work consist of the difficulty of operating the pit loom, of weaving jacquard designs, and of maintaining unfaltering originality in every piece woven (see fig. 12). The stories and legends about the incomparability of the Banarsi sari and its attractiveness for all people in all times are part of the weaver's way of conceptualizing himself. The first reaction of the weaver to a question about his place in society is to bring down the three-by-one-foot cardboard boxes that house the Banarsi sari, if he is a prosperous or master weaver, or to open up the weaving side of the loom to reveal the precious product being created there, if he is too poor to have anything in store.