Losing Ground:

Changing Contexts, 1930–1970

Although urban renewal alone is often blamed for the SRO crisis, earlier and more diffuse forces also sharply affected the residential hotel market. These included work place shifts caused by the depression, World War II, and office expansion, as well as shifts in highway and parking construction, American traditions of retirement, and the treatment of mental illness.

New Migrations

The depression was a boon to anyone who had inexpensive housing to rent; especially for inexpensive hotels, hard times meant steady and often overflow business. In skid rows, older and more desperate casual workers piled up. Among the many new urban residents were married men from farms and small towns who left their families to look for work in the city and young girls who shared rooms while they worked as secretaries, putting off college or starting a family. While managers of San Francisco's expensive hotels worried about staying in business—occupancy rates at the better hotels often fell below 60 percent—owners of Western Addition rooming houses found that by cutting repairs they could maintain an after-tax income ranging from 8 to 17 percent.[2]

After 1939, employment surges for World War II production overwhelmed every price level of hotel housing in America and led to the all-time peak in hotel residents. At the better hotels, managers gave priority for rooms to foreign diplomats, production contractors, and military officers in special training. Occupancy rates averaged more than 82 percent, higher than the best rates of the 1920s. However, at many good hotels social elegance and lavish meals faded.[3] Elsewhere in the city, landlords—with the blessing of local and federal emergency housing offices—hastily converted buildings into rooming houses or cheap lodgings. In the districts close to San Francisco's downtown, conversions created hundreds of new rooming houses.[4] Rosie the Riveter and her male colleagues found themselves in emergency dormitory and barracks-style housing, often modeled on traditional lodging and rooming houses. In addition, one nondefense worker moved to the cities for every war-related worker; more than half lived in single-person households, and most were under thirty years old. These wartime conditions caused social workers to worry that one-fourth of the young

Figure 9.1

Geary Street in the early 1950s, before urban renewal. A commercial

node in a hotel district in the Western Addition, San Francisco.

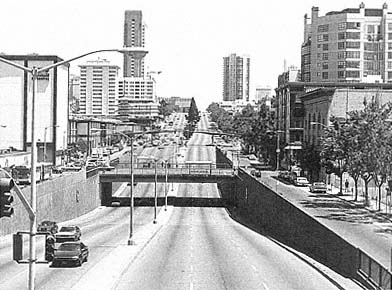

Figure 9.2

Geary Street at the same location, 1992, after urban renewal. A few older

buildings, middle right , survive, but the new rules of land use, building type,

and transportation have eliminated the former rules of the street.

male migrants were "living in flophouses and cheap hotels in the worst sections of the city." In racial ghettos where restrictive covenants constrained expansion, the influx of new minority war workers often meant severe overcrowding.[5]

Ten years after the wartime boom, residential hotel life was beginning to wane in the older expensive hotels, which were catering more to conventioneers than to smaller numbers of local elites. Rent controls imposed on hotel keepers during the war had also made them wary of permanent residents. At the new palace and midpriced hotels of the 1950s and 1960s, owners looked strictly for transient and convention business. To keep prices down for the new clientele, managers ordered chefs to find additional ways to trim the elegance of their menus and service; culinary talent scattered, and private restaurants took up more of the deluxe dining business.[6] The conversion of most top hotels to strictly tourist business helped to stop a 150-year pattern—the generational shift of elite permanent guests from a fading hostelry to the next largest and more socially prominent hotel. The dwindling population of middle and upper class hotel residents entrenched themselves where they were. The middle-aged and elderly high-income residents tended to collect at fewer and older hotels that maintained more traditional dining service and avoided conventioneers. The new social elites, if they lived downtown at all, usually did so in exclusive apartments perched on top of parking garages. The entrenchment in palace hotels cut into the former glamour of hotel life as the number of glittering and notable permanent guests declined. It also interrupted the process of filtering. Fewer good residential rooms were being vacated; hence, fewer residential rooms filtered to a lower price range.

Even after World War II, the rooming house market flourished as a result of the continuing influx of single and mobile young adults, most without cars. Organizations of boarding homes for women remained active into the mid-1950s. In 1951, the creators of the science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still could present rooming house life lived by a single mother. The suburbs held few housing opportunities for these young people; suburban jobs and the new, boxy blocks of inexpensive suburban apartments would not be created in sufficient numbers until about 1960. Meanwhile, in neighborhoods near colleges and technical schools, the boom in enrollments during the 1940s and 1950s kept whole blocks of rooming house establishments busy. Yet

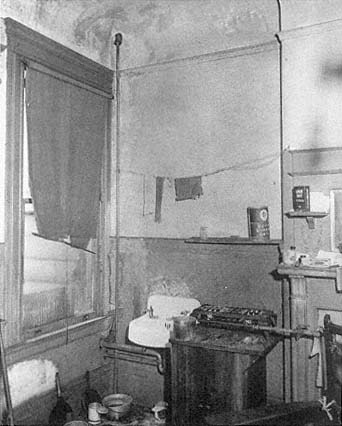

Figure 9.3

Jerry-rigged sink and hot plate, Western Addition, 1949.

Slum conditions in this San Francisco neighborhood's

light house-keeping rooms had been exacerbated

by World War II overcrowding.

some supplies of rooms at this price range were literally losing ground. Middle-income families in houses and apartments less often needed to take in roomers. The roomers still in the market were less likely to be of the same race or ethnicity as the landlady, further discouraging rooming house life. In the better neighborhoods, many owners of small midpriced hotels converted their buildings to apartments by adding kitchens and private baths, often with public assistance. Particularly in tenement districts or racially transitional neighborhoods, overcrowding, poor management, and the accumulation of needed repairs turned hastily converted wartime rooming houses into slum housing (fig. 9.3).[7]

Making Room for Offices and Cars

The most overt pressure on residential hotels came from the expansion of downtown office and retailing districts, which began again in earnest with the urban renewal of the 1960s. The case of San Francisco is typical. A downtown growth coalition of retailers and real estate developers was expanding the

downtown to accommodate the huge increase in office work created by the immense investment wealth of California and the city's expanded role in Pacific Rim trade. In the 1930s, total office space in San Francisco had stayed nearly static. During the 1940s, developers doubled the city's office capacity, often using lofts and temporary space. During the 1950s, owners made the wartime increases permanent, and capacity grew another 30 percent, making San Francisco fourth in the nation in terms of total office space. By the mid-1970s, San Francisco was second only to New York City as a center of international commerce and banking, second only to Boston in its ratio of office space to population. For the millions of square feet of additional office buildings needed, developers began to bid for sites in the South of Market.[8]

Simultaneously, other government policies and private speculative investment patterns also eroded the basis for hotel living. The sheer primacy and publicly secured profits of suburban single-family houses overshadowed most notions of investing in downtown apartments or residential hotels. Continuing policies of redlining meant that lending institutions often refused loans to rooming or lodging house areas. Meanwhile, at least in San Francisco between World War II and 1960, a generation of hotel owners literally died out. Unlike the patterns of the past, the inheritors (who no longer lived in the city but in elite suburbs) sold the hotels their forebears had built. They invested the money in suburban real estate they understood or in other sectors of the economy. Those prosperous optometrists who still lived in San Francisco's Pacific Heights were more likely to band together to build a medical office complex in suburban Dallas than to buy anything in the South of Market.[9]

Transportation investments acted on yet another series of fronts. To connect the new suburban city with the rebuilt downtown, traffic engineers and automobile-owning consumers called for new freeways and plentiful parking. Downtown highway and garage building hit directly at rooming and lodging house areas, beginning as early as the 1930s. California's transportation engineers planted highway approaches and viaduct routes—first for the Bay Bridge and later for freeways—directly through San Francisco's South of Market and the Western Addition, demolishing thousands of hotel rooms.[10]

Although highway construction leveled lower-cost hotel blocks, the automobile was not inherently an enemy for people living in midpriced

and palace hotels, at least not in the short run. If anything, for the middle and upper class, automobiles could be a boon to living downtown. In the early 1920s, a study at a south side lakeshore hotel in Chicago found one-fourth of the permanent residents had cars. Where motels cut into downtown tourist business, hotel managers could cater to additional permanent guests. To compete with motels, hotel owners also obtained garages and prominently advertised their parking. Permanent guests with automobiles enjoyed garage access as well; some small hotels offered backyard or side yard parking (fig. 9.4).[11] Thus the automobile per se did not seriously affect hotel housing choice.

In the long run, however, and for the majority of hotel residents, automobiles and hotel life did not mix. The residents of downtown rooming and lodging house neighborhoods found themselves looking out at freeway ramps or giant ditches built for six lanes of traffic, or contending with traffic noise and exhaust generated by automobiles on new through-roads and one-way pairs of downtown streets. In the areas of former single-family houses that owners had converted to rooming houses by the 1950s, parking became a major issue. Planning authorities wrote that parked cars without proper off-street spaces automatically caused blight. Neighbors harangued rooming house owners to provide off-street parking so their tenants' cars would no longer clog the streets or fill unsightly vacant lots (fig. 9.5).[12]

Other Changes for Hotel Tenants

As suburban employment surged for people with cars, the situation for non–car-owning residents of cheap rooming and lodging houses became grimmer. White-collar work continued to boom downtown, but blue-collar work did not. As part of the shift of use from streetcar and railroad to automobile and truck, workshop employers and shipping firms moved to outlying highway locations. San Francisco's port lost cargo traffic to more modern ports; buildings in San Francisco's South of Market became underused. Elsewhere in the downtown, employers were eliminating jobs through mechanization. Supervisors called for steadier family-tied workers instead of politically volatile, floating groups hired for short periods. Adoption of shorter workdays meant that more employees had time for commuting to more distant homes. These factors drastically changed the needs for downtown housing and the social roles of workers' districts. Younger laborers and family men did not pass through the skid

Figure 9.4

Small residential hotel with automobile

parking in the back. The Hotel Eddy,

with about 16 units, was a concrete

frame structure built in the early 1920s

in San Francisco's Western Addition. The

two carports at the back sheltered 10 cars.

Figure 9.5

Informal parking lot adjoining a rooming house in Omaha, Nebraska, 1938.

row as often as they had in the 1940s. Older, hard-to-employ men and the home guard were no longer a substrata but a primary proportion of the population (fig. 9.6). By 1960, welfare departments were referring more unemployed downtown people—especially the elderly—to hotels for temporary housing that tended to become permanent. As Joan Shapiro has written, this was often the beginning of an unplanned and unwilling interdependence between social services and hotel owners.[13] In 1961, officials from Minneapolis, Kansas City, and Norfolk seemed confident that demolition of several blocks of their respective

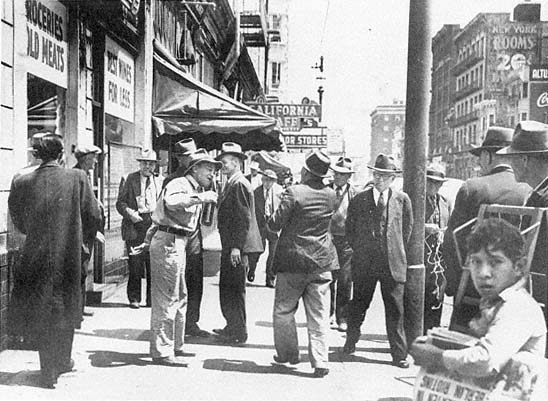

Figure 9.6

Older postwar population left on Howard Street in San Francisco's South of Market, 1953.

skid rows had permanently scattered their residents.[14] Enough vacancies still existed so that, indeed, most people displaced from the cheapest lodging houses could find some other place to live, probably at a higher proportion of their income or savings.

At middle-income levels, the national redefinition of old age brought other changes in the residential hotel market. Social security began to supplement retirement incomes in 1935. Fewer elderly men and women lived with their children, and people over sixty-five years of age began to create a new consumer market. Commercial care for the elderly and the supply of units in bona fide retirement communities improved markedly between 1940 and 1970, competing with yet another role played by midpriced hotels and rooming houses.[15]

A sudden influx of former mental hospital patients constituted a massive change for SRO tenancy. In the mid-1960s, the well-intentioned (and budget-cutting) decision of many states to mainstream mental hospital populations had been coupled with promises of half-way houses and group homes. Modern psychiatric medicines made this release possible. In California, the population of the state mental hos-

pitals declined from 37,000 to 7,000 between 1960 and 1973. However, the halfway houses were never established. Patients were essentially dumped into downtown hotels where neither hotel staff nor residents were prepared for the care required by these new neighbors. In conversation, tenants and managers alike often mention the arrival of publicly supported but inadequately served mental patients as the last blow to pleasant SRO life downtown. As one hotel owner put it, "Suddenly you weren't managing a building; you were running a nut house."[16]

In spite of all these shifts, not all residential hotels were dying. Through the 1960s, hotel rooms at every price range were a smaller but still surviving and viable housing market. A sizable population of healthy, usually single, and often elderly people still lived downtown in hotels and chose that style of housing. By the late 1960s, the formerly ample supplies of lodging house rooms were filling up. In the cheapest hotels that remained open in 1970, the arrival of new desperate tenants and the departure of the better tenants (for better hotels, apartments, or suburban life) left thousands of hotels packed with what one social worker in the mid-1970s described as "a human residue of the elderly and poor."[17] Ironically, the market-driven declines in hotel life were largely intended and carefully planned as part of the official rebuilding of downtown.