3. Jewish Education

Just as the author's Hellenistic education has been overestimated, the breadth of his Jewish education has not yet been properly appreciated.[77] This appears from the references to Jewish ritual practices. Some of them allude to the priests; others to the Temple. With regard to the priests we have established above the accuracy of the statements about their abstention from wine in the Temple and their indulgence in rituals of purification "night and day" (Ap. I.199).[78] To these must be added the reference to the tithes. The author states that the priests receive "the tithe of the produce" (I.188), while according to the Pentateuch tithes were to be given to the Levites (Num. 18.21, 24). The sentence has been much discussed, and scholars have tried to apply it to the controversy over the authenticity of the book.[79] Taken by itself, it can support neither of the two opposing views.[80] The conclusion that the book was written in the time of the Hasmonean kingdom puts the sentence in the right perspective: it records the practice of the Hasmoneans, which

[74] On the Greek of Pseudo-Aristeas, see the comprehensive study of Meecham (1935) 46ff., 154ff., 311ff.; cf. Tcherikover (1961a) 320.

[75] See the analysis of its style by Gärtner (1912); Reese (1970) 1-30; Winston (1979) 14-18.

[76] On the author's Greek education and knowledge of the Greek language, see Tcherikover (1961a) 350-51, 356-58.

[77] The scholars who hold the author to be a priest (see pp. 145-46 and n. 16 above) mention only the reference to the stones of the altar (para. 188; see esp. Wacholder [1974] 270). The only detailed discussion of the account of the Temple is by Zipser (1871) 79-88, who accepts the book as authentically Hecataean. His analysis is, however, sometimes inaccurate, and he often draws the wrong conclusions.

[78] See pp. 144-45 above.

[79] See esp. Schaller (1963) 22-26; and the response of Gager (1969) 137-38.

[80] So, rightly, M. Stern (1974-84) I.41; Holladay (1983) 326 n. 13.

was contrary to the rules of the Pentateuch. The new practice may already have been introduced before the Hasmonean period, but this cannot be proved. It can only be said with certainty that the Hasmonean rulers insisted on compliance with the new practice and employed tough administrative measures to enforce it.[81] We thus see that in this case Pseudo-Hecataeus follows the current practice of his age, and not the old written law.

The number attributed to the Jewish priests (Ap . I.188) also deserves attention in this context, although it is irrelevant to the question of the author's education. Pseudo-Hecataeus states: "All the Jewish priests who receive the tithe of the produce and administer public matters number at most about one thousand five hundred." This estimate considerably falls short of the number of priests at the time of the Restoration (Ezra 2.36-38). It has therefore been assumed that the figure approximately reflects the number of the Jerusalem priests alone (cf. Neh. 11.10-14; I Chron. 9.13).[82] The statement, however, refers to "all the priests." As the sentence qualifies the priests as those who are engaged in public matters, it behooves us to accept the alternative that Pseudo-Hecataeus gives only the number of the priests who were occupied in public administration.[83] This interpretation gains support from the context: the sentence does not appear in the framework of the account of ritual duties of the priests and the Temple, but follows the passage that elaborates on the leadership and administrative skills of Hezekiah the High Priest (Ap . I.187). The number quoted cannot be verified, but integration of such a number of priests in the royal administration of the Hasmoneans in the generation of Pseudo-Hecataeus does make sense, especially in view of the pro-Sadducean policy of Alexander Jannaeus and his father, John Hyrcanus, in his last years.

The author's knowledge is rather impressive when referring to cult objects of the Temple. Two points deserve attention. First, his version does not contain any allegorical interpretation or any Hellenistic feature. This stands in sharp contrast to Philo, Pseudo-Aristeas, and Eupolemus, the Jewish Hellenistic authors who elaborate on the Temple's

[81] See, e.g., Alon (1957) 83-92; Oppenheimer (1977) 38-42; Bar-Kochva (1977) 185ff. Cf. M. Stern and Holladay, locc. citt . (n. 80).

[82] < So Büchler (1895) 49; M. Stern (1974-84) I.42; Doran (1985) 917 n. d.

[83] Similarly Schlatter (1893) 94; Klein (1939) 37-38.

cult objects.[84] Second, the fragment basically accords with the available information about cult objects of the Second Temple. They partially differed from those known from the time of the First Temple. This shows that the author drew his information not from the Pentateuch or the Books of Kings, but from contemporary reports.

His account opens with the stone altar. According to Pseudo-Hecataeus it was made of unhewn stones, placed outside the main building, and measured "twenty cubits long and ten cubits high" (I.198). At the time of the First Temple there were stone altars only in the provinces. The offering altar in the Tabernacle and the First Temple was made of bronze. It was replaced in the visionary temple of Ezekiel and at the time of the Second Temple by a stone altar.[85] The altar was placed near the entrance to the shrine (Jos. Bell . V.225; Philo, Spec. Leg . I.274). The construction of this altar of unhewn stones, based on the Torah instructions for provincial stone altars (Exod. 20.25; cf. Deut. 27.5-6),[86] is known from the period before and after the defilement of the Temple by Antiochus IV (I Macc. 4.47; Josephus, loc. cit. ; Philo, loc. cit. ; Middot 3.4).

No less instructive are the measurements quoted by Pseudo-Hecataeus. They equal those of the bronze altar, its predecessor, built by Solomon, as listed by II Chronicles (4.1), and differ from both the much smaller bronze altar of the Tabernacle (Exod. 27.1) and the visionary altar of Ezekiel (43.13-17). According to Josephus, the stone altar of the Herodian Temple measured 50 x 50 x 15 cubits (Bell . V.225), but the Mishna gives other measurements: for the lower base, 32 x 32; and for the upper surface, 24 x 24 (Middot 3.1). The latter information, which originated from a knowledgeable eyewitness,[87] is much more detailed and elaborate, and may therefore be more accurate. As far as the pre-Herodian stone altar is concerned, the only direct piece of

[84] See Philo's allegorical interpretations of the cult objects in Spec. Leg . I.74ff., and esp. Quaest. Exod . II.52ff. For the Hellenistic features in Pseudo-Aristeas, see paras. 50ff.; and in Eupolemus: Lieberman (1962) 173.

[85] See the survey of M. Haran in Encyclopaedia Biblica (Jerusalem, 1962) IV.772-73; Yadin (1977) I.186. Cf. esp. Exod. 38.1-7, I Kings 8.64, Ezek. 9.2; and the references below.

[86] Cf. pp. 149-50 above.

information that may be relevant[88] is the number, 20, that survived in a fragmentary account of the stone altar in one of the Qumran Aramaic scrolls.[89] In addition to that, the author of the Books of Chronicles may well have based the measurements of Solomon's bronze altar on the size of the stone offering altar of his time, in the late fifth century, as he frequently does when his source, the Books of Kings, does not contain the necessary information.[90] It seems probable, therefore, that Pseudo-Hecataeus indeed properly recorded the measurements of the stone altar of his time. That he relied on the information given in Chronicles is a less acceptable possibility: readership of this book was always rather limited. Philo, for instance, hardly ever refers to any biblical book outside the Pentateuch.[91]

The next item is a golden altar, located in "a great edifice" (Ap . I.198). The reference is to the golden incense altar (Exod. 30.1-10) that was placed inside the Temple.[92] The existence of this altar, known from Philo and Palestinian Second Temple sources,[93] is not recorded by Pseudo-Aristeas, who was familiar with Jewish religious practices and elaborates on the Temple and its objects. It is noteworthy that even the Mishnaic

[88] The minority opinion of Rabbi Yosi in Middot 3.1 about the upper surface of the altar in the time of the Restoration (24 x 24 cubits) is an attempt to harmonize conflicting biblical references (including Ezekiel) and give the impression of a continuity between the periods. This appears from his terminology and argumentation. Rabbi Yosi ("the Galilean") belongs to the generation of the Bar-Kokhva Revolt, and his original comment underwent a later adaptation (see Epstein [1957] 36).

[89] See Yadin (1997) I.186, referring Baillet et al. (1962) 88-89.

[90] The description of the Book of Chronicles as a midrash of the Book of Kings has been commonly accepted. The question is only whether and to what extent the author supplemented it by reliable sources for the period of the First Temple. See the survey of research in Japhet (1977) 334-36. For a new wave of contributions reviving the old extreme negative view, see Welten (1973); Mosis (1973); North (1974); Mackenzie (1984). Cf. Na`aman (1989).

[91] On Philo's use of biblical books, see Knox (1940); Borgen (1981) 55, (1984) 258.

[92] I Kings 6.22, II Chr. 4.19, I Macc. 4.49; Jos. Bell . V.215.

[93] 3. In addition to the sources mentioned above, see I Macc. 1.21; Jos. Bell . V.225; Philo, Spec. Leg . I.274; Temple Scroll, col. VIII (see Yadin [1977] II.23-26; the column describes the incense altar, though the word "gold" has not survived in the few barely legible lines that have come down to us).

tractate Middot, devoted to the Temple, fails to mention the golden altar. Only Mishna Hagiga (3.8) alludes to it.

Together with the golden altar, the author lists the celebrated golden lamp, which is mentioned by many Jewish and gentile sources. This is followed by the statement that the gold of these two objects weighed two talents (Ap . I.198). The lamp of the Tabernacle is said to have weighed one talent (Exod. 25.38-39), but there is no indication as to the weight of the gold of the incense altar. Pseudo-Hecataeus may have conjectured or known that the weight of the gold cover of the altar was equal to that of the lamp. At the same time I would not rule out the possibility that the original text referred only to the weight of the lamp. The Temple Scroll indeed states that the lamp, together with its various utensils, weighed two talents (col. IX, line 11). This may be an interpretation of the biblical verse,[94] but it can also accord with the real weight of the lamp and its utensils at the time of the Second Temple.

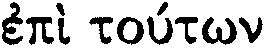

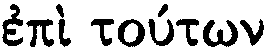

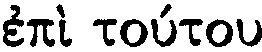

The allusion to the incense altar and the lamp ends with the sentence "Upon these [

Following the account of the main objects of the sanctuary, the author stresses that there were no statues, votive offerings, plants, or grove in the Temple (Ap . I.199).That statues were forbidden everywhere in the Temple does not require references, and an explicit prohibition on planting trees within the Temple precincts is known from the Pentateuch (Deut. 16.21) and seems to have been strictly

[94] See Yadin (1977) II.28-29 on the dispute over the interpretation of Exod. 25.38-39.

[95] See, e.g., Jos. Ant . III.199; Tamid 3-9, 6.1; BT Yoma 39b; Sabbat 39a-b. The practice in the Tabernacle was probably different; see Exod. 30.7-8, Lev. 24.2-3, I Sam. 3.3. But see Exod. 27.20.

[96] See Philo, Spec. Leg . I.285; and see Lev. 6.9, 12, 13. Cf. II Macc. 1.19-22; Maimonides, Temidim II.1.

observed.[97] The reference to votive offerings requires more elaboration. Oriental and Greek temples abounded with these objects. They were carefully registered in official lists, some of which have come down to us.[98] For a monotheistic religion, which also rejected material representation of the divine, votive offerings must have presented an obvious threat. Though the Pentateuch regulates only dedications to the Temple treasury (Lev. 27.1-8, 16-24, 28), there is no explicit prohibition on the public display of votive offerings. On the contrary, Moses is said to have constructed a bronze serpent (Num. 21.8-9), which indeed was soon sanctified and acquired a cult of its own. There is sufficient evidence that votive offerings were not entirely absent from the two Temples, but the impression is that there were not many of them, nothing similar to the numbers found in pagan temples.

At the time of the First Temple we read only of the bronze serpent, which was finally destroyed by King Hezekiah (II Kings 18.4). The weapons of King David were also placed in the Temple (II Kings 11.10; cf. I Sam. 21.9). One may assume that at least during the time of the kings who introduced pagan cults into Jerusalem and the Temple, greater numbers of votive offerings were to be seen.

The only extant piece of information about votive offerings in then pre-Herodian Second Temple refers to "crowns" (I Macc. 1.21-22, 4.57).[99] They were placed there already at the time of the Jewish Restoration (Zech. 6.9-15, Middot 3.8). As they are the only items mentioned besides the ordinary Temple cult vessels later plundered by Antiochus IV, it may be that there were no other costly votive offerings in the Temple. If this is correct, it indicates that in the wake of the increasing monotheistic strictness at the time of the Restoration there was opposition to the display of votive offerings in the Temple. The crowns may have been regarded as a special case since they symbolized

[97] The references quoted to support a contrary view by Zipser (1871) 86-87 are irrelevant for the Temple itself. The prohibition is also mentioned by Philo, Spec. Leg . I.74; Leg. Alleg . I.48-52.

[98] On votive offerings in the Greek world, see Rouse (1902), which still remains the standard work on the subject.

the authority of the High Priest as well as hopes for the return of the Davidic dynasty.[100] At the same time, allowance must be made for the possibility that the paucity of references to votive offerings in the pre-Herodian Temple is only accidental.[101]

Much more information about votive offerings is available for the Herodian Temple. A huge golden vine was located at the entrance (Jos. Ant . XV.394-95, Bell . V.210-12; Tac. Hist . V.5), and small private donations were placed on it (Middot 3.8). The vine seems to have symbolized first and foremost the Jewish nation.[102] A golden chain donated by Agrippa I was hung in the forecourt of the Temple (Jos. Ant . XIX.294). and the above-mentioned crowns were displayed inside the shrine. The presence of votive offerings in the Temple is also explicitly mentioned in the New Testament (Luke 21.5).[103] Phil, who mentions the prohibition on trees within the precincts of the Temple, does not refer to the question of votive offerings, although he endeavors to offer an allegorical explanation for the bronze serpent.[104]

[100] On the textual question involved in the interpretation of Zech. 6.11, 14, and the meaning of the two crowns, see, e.g., Kaufman (1937-56) VIII.262-66; Uffenheimer (1961) 117-18; Meyers and Meyers (1987) 349-50, 362-64.

[101] Jos. Ap . II.48, if it is to be trusted, does not say that the votive offerings were exhibited in the Temple. They could have been kept in the treasury, as was done with private donations (see n. 103 below). Goodenough's conjecture ([1953-68] V.99-103; already anticipated by Zipser [1871] 86) that the huge vine of the Herodian Temple actually replaced the vine donated by Aristobulus II to the Romans (Jos. Ant . XIV.34-36) is unwarranted. Moreover, if the reading of the MSS "from Alexander the Jew" is correct, that vine could not have been taken by Aristobulus from the Temple. On the textual question and the historical interpretation, see M. Stern (1974-84) I.275.

[102] First suggested by Holtzmann (1913) 87ff. Cf. Isa. 5.1-5, Jer. 2.21, Ezek. 17.5-8, Ps. 80.9-12. However, the vines on Jewish coins and ossuaries need not be understood in the same sense. On the symbolism of the vine, see also Goodenough (1953-68) XIII passim . The golden chains mentioned in Middot 3.8 may have their origin in the description of the Tabernacle (Exod. 28.14).

[104] On trees, see n. 97 above. On the bronze serpent, see Philo, De Agricultura 97. Cf. Sap. Sal. 16.5-6.

The statement in Pseudo-Hecataeus, which refers to the pre-Herodian Temple, may then be basically correct, or it may reflect a strict sectarian approach that opposed votive offerings. The danger of votive offerings' tending to acquire a cult of their own was certainly well known to Diaspora Jews. The wish to avoid any resemblance between Jewish and gentile cults is evident in the statement under discussion. Moreover, it may well be that the author wished to express a negative opinion about the practice of the Oniad temple in Leontopolis. Josephus stresses that Onias IV decorated his temple with votive offerings (Bell . VII.428). In a letter said to have been sent by Onias IV to Ptolemy VI, asking for permission to build a temple in Leontopolis, the site chosen for the temple is praised for being "most suitable, ... full of [a variety of] colorful trees" (Jos. Ant . XIII.66). Whether the letter is authentic or not, it may indicate that the trees were later left in the precinct of the temple. If this is true, the reference to the absence of trees in the Jerusalem Temple is also meant to deplore the practice in Leontopolis.

In view of the author's relatively abundant knowledge about the Temple, the absence from the list of the golden table ("show-bread table"), one of its three most celebrated cult objects (Jos. Bell . V.216, Menahot 11.5),[105] is rather surprising.[106] I would venture to guess that he was reluctant to refer to the golden table because of the detailed (and imaginary) account by Pseudo-Aristeas, his older contemporary, about its design, construction, and decoration by the artisans of Ptolemy II (paras. 51-72). Pseudo-Hecataeus, who was strongly against gentile influence in religious matters, must have been uneasy both about the role of a Ptolemaic king and workmen in constructing one of the holiest objects of the Jewish Temple and about its sources of inspiration in pagan art, no matter which table was in fact used in his time.[107] He may have felt that listing the table

[105] The golden table was also commemorated on Jewish coins from the short reign of Mattathias Antigonus (see Meshorer [1982] I pl. 55 nos. Z.1-3).

[106] It is less likely that Josephus omitted a reference to the table (cf. Schlatter [1893] 94). After describing the vessels, the quotation goes on to note the absence of statues, plants, and votive offerings.

[107] On the possible influence of the Dionysian cult, see Büchler (1899) 198-99 n. 28; and on the similarity of certain features with those of utensils described by Callixenus (Athen. V.196ff., esp. 199b-c), see Hadas (1951) 47-48. But see Fraser (1972) I.697, II.975 n. 133. Cf. Rice (1983) 72. There is no resemblance between the table of Pseudo-Aristeas and that of the Pentateuch, the Hasmonean coins, and the Mishna (contrary to Meshorer [1982] I.95-96: the legs are different; there is no figure for the width in Pseudo-Aristeas, and his table is not necessarily rectangular [see paras. 58-60]). Be the historicity of the report of Pseudo-Aristeas as it may, the show-bread table was stolen by Antiochus Epiphanes in his outburst to the Jerusalem Temple in the year 168 (I Macc. 1.22), and a new one was brought to the Temple shortly after its purification by Judas Maccabaeus in 164 B.C. (ibid. 4.49).

would also require some reference to the story circulated among Egyptian Jews concerning its origin, and therefore preferred to omit it altogether.

Another omission can enhance our appreciation of the author's knowledge of the Temple in his day. He does not mention the Ark of the Covenant. The ark played a central role in the Tabernacle and the First Temple, but disappeared at the time of the Babylonian exile and was not replaced in the Second Temple (Sekalim 6.1; cf. Jos. Bell . V.215-21). We see again that Pseudo-Hecataeus did not rely uncritically on the Bible, but based his information on up-to-date knowledge.

The author's acquaintance with Jewish traditions and cult, on the one hand, and his mediocre Greek style and ignorance of "Greek wisdom" and mantic practices, on the other, naturally raise the question of his mother tongue. Analysis of two "sensitive" cult terms suggests that Pseudo-Hecataeus used the Hebrew original of the Holy Scriptures and not the Greek translation. Thus he calls the temple altar bomos (Ap . I.198) after applying the same term to pagan altars (I.193). In the Septuagint the word designates only gentile altars. Wishing to distinguish the latter from the legitimate altars of the Jewish God, the translators invented the term thysiasterion for the Temple altars. They were even careful to differentiate between pagan altars and the "illegal" Israelite altars (bamot in Hebrew) located in the provinces, which were so deplored by the Books of Kings, and consistently refrained from employing the Greek bomoi (despite the obvious similarity with the Hebrew), always using the literal translation hypsela .[108] The other case is the word neos , which is used by Pseudo-Hecataeus to designate gentile temples (I.193),[109] while the

[108] See the discussion in Daniel (1966) 27-53.

[109] The word neos in para. 196, which refers to the Jewish Temple, appears in an introductory sentence phrased by Josephus, but it could be influenced by a similar usage in Pseudo-Hecataeus.

Septuagint reserves it for the Jewish Temple alone (also in the forms naos and naios ).[110]

The terminology of the Septuagint influenced early Jewish Hellenistic authors like Pseudo-Aristeas and Jason of Cyrene, who applied only naos , and even the Jewish neologism thysiasterion , to the Jerusalem Temple and altar, respectively, though they wrote an idiomatic and sophisticated Greek and the former even pretended to be a gentile author.[111] As Pseudo-Hecataeus demonstrates extreme zealousness against pagan altars and temples and devotion toward the Jewish faith and cult, one cannot believe that he had been brought up on the Septuagint or that he used it regularly. The concurrent use of identical Greek terms for the Jewish and pagan cults would have imposed difficulties mainly in respect to religious services in synagogues. The conclusion is therefore that Pseudo-Hecataeus was brought up on the Hebrew Bible, and used it in religious ceremonies and for study and reference. He would not have felt the need to differentiate in Greek between Jewish and pagan altars and temples, and would have had no theological inhibitions on this point. It is, however, difficult to affirm that Hebrew was his mother tongue or the language he used daily at home.