1—

Introduction

In things there is nothing more manifest than having results, and in argument there is nothing more decisive than having evidence.

Wang Chong (A.D. 27–ca. 100)

"I'm afraid we're pretty much the same thing, over and over," remarks a bald, chinless, hook-nosed gentleman of his ancestral portraits. Indeed, only the variegated clothing hints at generational, but not genetic, differences among the framed figures of Gahan Wilson's New Yorker cartoon (fig. 1). Confounding Mendel's Law, identical bald, chinless, hook-nosed faces stare down from the walls at their still-ambulatory replica.

The witty cartoon challenges the common view that a portrait is merely a record of one never-to-be-replicated being, the document, like a passport photo, warts and all, of a unique individual. It is a pictorial translation of a grander statement by Gertrude Stein:

People really do not change from one generation to another, as far back as we know history people are about the same as they were, they have had the

1.

Drawing by Gahan Wilson;

© 1985 The New Yorker Magazine, Inc.

same needs, the same desires, the same virtues and the same qualities, the same defects, indeed nothing changes from one generation to another except the way of seeing and being seen . . . . The creator in the arts is like all the rest of the people living, he is sensitive to the changes in the way of living and his art is inevitably influenced by the way each generation is living.[1]

Alike we may all be; yet the commonplace view cannot be denied. For the portrait, by any definition, is always particularistic, your ancestors or mine. One function of portraiture, then, must be to document that particularity. However, its other functions—aesthetic and social—affect, and may even subvert, the depiction of that unique phenomenon. It is that very tension engendered by the necessity to serve multiple, often conflicting, functions that invests the study of portraiture with enduring interest.[2]

Recent archaeological finds in China offer an opportunity to investigate some of these tensions anew. If modern portraits, both literary and pictorial, are prime examples of Stein's insistence on the changing ways of seeing, so, I suggest, are these portraits of a different time and place. At the same time, they prompt a reexamination of old issues within the field of Chinese art history or of preconceptions firmly held—often most firmly when visual evidence was lacking. Drawing on new pictorial evidence, this study will consider the problem of early Chinese portraiture, its nature and functions.

The discovery of a brick tomb with portrait reliefs datable to the late fourth or early fifth century of this era was reported in 1960.[3] Accidentally unearthed near the Xishan Bridge outside present-day Nanjing, in Jiangsu province, the tomb contained relief-murals of eight figures, each named by inscription (figs. 2 and 3). Seven of the figures depicted are historical personages, famous in Chinese history and literature as the Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove (Zhulin qixian ). The eighth figure, one Rong Qiqi, is not historical but legendary, a famous figure in Chinese literature.

The reliefs, heralded as a unique find in both construction method and subject matter, were widely discussed—as the only examples of Jin–Liu-Song (A.D. 317–420, 420–479) portraiture, as compositions that differed dramatically in form and style from Han dynasty tomb art, and as authentic examples of the styles of various Jin-Song painters.[4] They ceased to be unique, however, when the finds from an imperial tomb excavated in 1965 in Danyang county, Jiangsu province, suggested that another portrait-mural of the Seven Worthies may have existed.[5] Although pictorial evidence had long since disappeared, its identification and location on the long walls of the main chamber were determined by the presence of a brick engraved in intaglio with the characters Xi xia xing, a reference to one of the Seven Worthies, Xi Kang.

The assumption of a second, similar, mural grew firmer when two more royal tombs excavated in 1968 in the Danyang area yielded pictorial evidence of the Seven Worthies as well as inscribed bricks naming the same personages (figs. 4–6).[6] Despite their poor and fragmented condition, it is clear that these Danyang depictions of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi follow the basic composition of the Nanjing mural, although we shall observe minor differences that are significant for this study. By consensus, all three of the imperial Danyang tombs are datable to the late fifth century—that is, to the Southern Qi dynasty (A.D. 479–502).

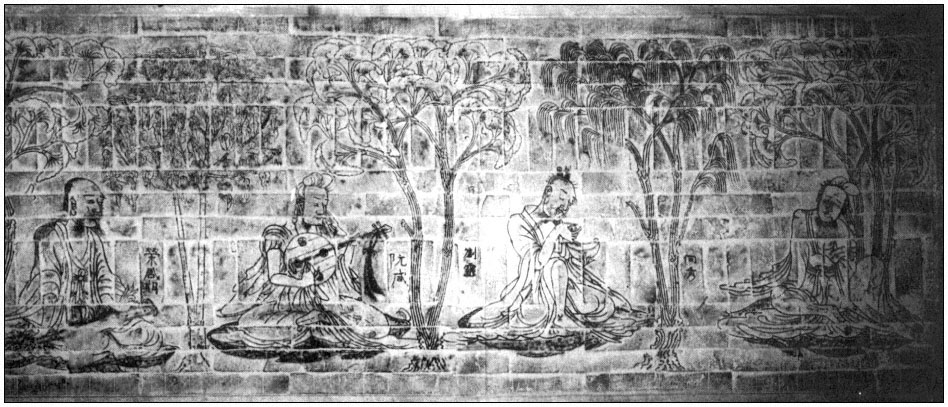

2.

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi.

Rubbing of a brick relief from the south wall, tomb at Xishanqiao, Nanjing,

Jiangsu province. Late fourth–early fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

With the discovery of three sets of portraits of the same personages spanning a period of some fifty to one hundred years (and the probable existence of a fourth at the time of entombment), we may conclude that we confront no idiosyncratic choice of tomb décor. Rather, we possess a set of portraits that testifies to a convention or fashion during that period known as Nanbeichao in a specific region of China.[7] In that sense, the set of three mural-portraits is unique and offers a fresh opportunity to examine, within narrow but detailed limits, a traditional category of art history, that of portraiture.

Although a much-studied art form in the West, portraiture has received comparatively scant attention in traditional Chinese art history, and Western scholars of Chinese art have rarely shown enthusiastic interest in the genre.[8] Few studies devoted exclusively to the subject have appeared in this century. In 1912 Berthold Laufer published a study of portraits of Confucius. William Cohn produced a slim volume devoted to portrait painters of East Asia in 1922, and S. Elisséev examined portraiture of the Far East in 1932.[9] Thereafter the pattern of once a decade dissolved. Only in 1960 did Max Loehr turn his attention to the subject of early portraiture, thereby barely anticipating the publication of the first Seven Worthies mural.[10] Loehr's paper thus truly stands as the seminal study for work that followed, most notably Ellen Johnston Laing's "Neo-Taoism and

3.

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi.

Rubbing of a brick relief from the north wall, tomb at Xishanqiao,

Nanjing, Jiangsu province. Late fourth–early fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

'The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove' in Chinese Painting." More recently Hou Ching-lang published a study of portrait painting of the early Western Han period.[11]

Compared with the body of scholarly literature on Western portraiture—even for any one period, say, Roman or Renaissance portraiture—these are scant gleanings. Yet extant historical documents attest to Chinese portraiture for the early periods, and extant pictorial documents affirm that the art of portraiture existed at least as early as the Han dynasty (206 B.C. –A.D. 220). An inquiry into the nature of that portraiture for one period, the Six Dynasties, and one

place, the region of modern Jiangsu, seems therefore to be both in order and unlikely to exhaust the topic.

When, however, we turn for guidance to the literature of Western art for definitions and models we may experience bewilderment. For little consensus exists as to precisely what "portraiture" as an art form may be. Consulting the Encyclopedia of World Art, for example, we find that, in the broadest sense, portraiture is "the representation of an individual, living or dead, real or imagined, in drawing, painting, or sculpture, by a rendering of his physical or moral traits, or both." The key word, apparently, is "individual."[12]

The Encyclopedia further tells us that portraits offer a "veritable anthology of the ways of conceiving of man"; that the different

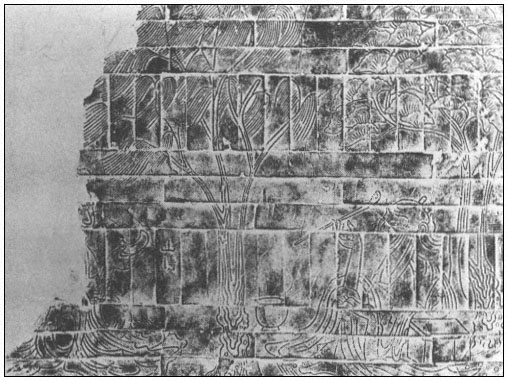

4.

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi.

Rubbing of a brick relief from the west wall, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

portrait styles of, for example, Van Eyck and Titian may have been determined as much by different moral attitudes as by different artistic personalities. Moreover,

conventions of costume and gesture may loom as large as—or larger than—physiognomical fidelity. The attributes or signs used in a portrait must always be considered in their historical and social context, since [their] significance can vary with different epochs and cultural traditions. The new and more complex classifications of portraiture that are needed must be based as much on the varying functions of portraiture as on the changing fashions in iconography and style.

Are there, then, no limitations, other than that the work of art must depict, in some way, an individual? An exhaustive search of the scholarly literature for definitions of portraiture itself poses a topic for research. Yet a few selected comments may offer further guidance.

J. D. Breckenridge, for example, grapples with the problem of definition in his study of ancient portraiture and confesses that avoiding the issue may be the better part of valor.[13] Reviewing the literature, he examines the essential requirements for a "true portrait" set forth by Bernhard Schweitzer:

1) It must represent a definite person, either living or of the past, with his distinctive human traits. 2) The person must be represented in such a manner that under no circumstances can his identity be confused with that of someone else. 3) As a work of art, a portrait must render the personality, i.e., the inner individuality, of the person represented in his outer form.[14]

Recognizing the pitfalls of these criteria, Breckenridge suggests that, at least for studies of ancient portraiture, Richard Delbrück's definition may be more viable: a portrait is "the representation, intending to be like, of a definite individual."[15]

"Intending to be like" thus joins "individual" as a key word or phrase. However, "the criterion of the 'true' portrait . . . is in no sense merely literal accuracy or fidelity to optical appearances; on the contrary, the creation of a successful portrait . . . will call for some manipulation of visual appearances on the part of the artist."[16] Fidelity? Manipulation? One is reminded of Lysippus's remark that a good portrait depicts men not as they are but as they should be.

What then of "likeness" or resemblance—those presumably chief criteria for judging a contemporary "portrait"? E. H. Gombrich considers their meaning in a series of papers, the most notable being "The Mask and the Face."[17] Perceptions of resemblance vary, he reminds us in that paper. As he remarks in "Action and Expression in Western Art," the problem for the traditional arts is that they lack "most of the resources on which human beings and animals rely [for recognition] in their contacts and interactions. The most essential of these, of course, is movement."[18] The maker of the portrait must therefore find pictorial substitutes—schemata—for these resources if the observer is to recognize the individual portrayed. What Gombrich calls the correct portrait "is not a faithful record of a visual experience but the faithful construction of a relational model."[19]

The portrait, then, is a construction intended to be like an individual—in short, an illusion, that very illusion rejected by Plotinus

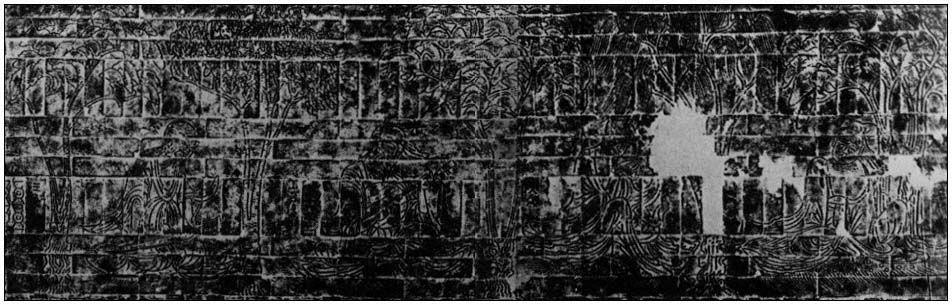

5.

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi.

Rubbing of a brick relief from the east wall, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

for its irrelevance to reality. For the art historian, however, that illusion, that deliberate construction, "reaches beyond reproduction to metaphor whose possibilities can be explored and whose real meaning is to be extricated with the established techniques of formal and iconographical analysis."[20]

It is a beginning. The Seven Worthies murals are portraits intended to be like specific individuals. We know this, not because the viewer recognizes the figures at a glance (although he may), but because he recognizes the name attached to each figure. To put it more accurately: because a name is attached to each figure, the viewer recognizes it as a portrait.

The question then is, In what ways were these portraits intended to be like the eight individuals identified by inscriptions?

I shall use both formal and iconographical analysis to explore the metaphors from the Chinese point of view. For if we hope eventually

to place Chinese portraiture within a general rubric of Portraiture, we must first determine what it meant within its own specific rubric. What meaning and significance, that is, did the Seven Worthies murals have to the people who commissioned them or to those who viewed them? This we cannot know until we know much about the patrons themselves—their sensibilities, their tastes, and the conditions that formed those tastes. As Gombrich reminds us, "The form of a representation cannot be divorced from its purpose and the requirements of a society in which the given visual language gains currency."[21]

In the following pages I shall demonstrate that the few Nanbeichao portraits available for study are character portraits—portraits that render a man's moral traits—made for the purposes of admiration, identification, and emulation. Like their Han dynasty predecessors, they are exemplary portraits, and they employ surprisingly similar pictorial devices to convey their messages. But some of these messages have changed. What is new for this later period of Chinese history is not the depiction of character but the nature of the character depicted. What was its visual language and among whom did it gain currency?

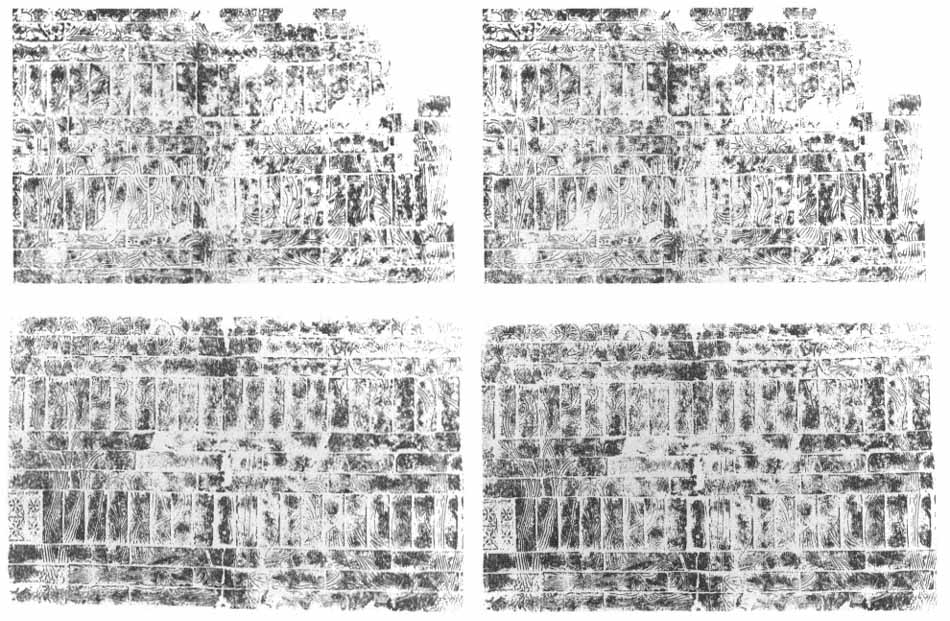

6.

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi. Top left and right, west wall panel; bottom left and right, east wall panel.

Rubbings of brick reliefs, tomb at Jinjiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Wenwu 1980.2.)