At the Académie Julian

Corinth arrived in Paris in early October 1884 and enrolled in the Académie Julian. Founded in 1868 by Rodolphe Julian, a minor painter who exhibited at the Salon des Refusés in 1863 and several times between 1865 and 1878 at the Salon proper, the Académie Julian was not an academy in the traditional sense but a place where students could draw and paint from the live model and profit, if they so desired, from an informal weekly critique. Although Julian had originally opened the school to prepare students for the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts, by the early 1880s the two schools had become rivals. The Académie Julian was especially popular among students from abroad, even though they paid tuition there whereas study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts was tuition free. Because the école was unable to admit all ap-

plicants—and because French taxpayers resented financing the training of foreigners—the Ministry of Fine Arts required foreign applicants to take a French language test so rigorous that only a few managed to pass it. Julian, by privately engaging teachers from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, including such famous pompiers as Adolphe Bouguereau, Tony Robert-Fleury, Gustave Boulanger, and Jules Lefebvre, helped foreign artists to circumvent the language test: on payment of hard cash, they could study under the école's leading masters without having to be admitted to the school itself. Moreover, because the "visiting professors" were usually also on the Salon juries, Julian's students stood to benefit substantially when they submitted their entries for acceptance to the annual Salon exhibitions.

Besides foreigners, the student body included young painters who rejected the école on principle and availed themselves of Julian's facilities because they could draw and paint there without much interference. Even at Julian's some of these students defiantly turned their paintings to the wall when the teachers came to offer their critiques. Many older artists kept returning to the Académie Julian because there they could count on having professional models to work from. According to one observer, only at Julian's did one find that "unique flesh, hearty and fair, with that particular touch of a supple glimmer."[42]

Julian's enterprise turned out to be highly successful. He eventually opened branch academies throughout Paris, including several studios for women. Over the years the foreigners at Julian's included the Russian Marie Bashkirtsev; the Englishman George Moore; the Swiss Félix Vallotton, Cuno Amiet, and Giovanni Giacometti; the Spaniard Ignacio Zuloaga; and the Finnish painter Aksel Gallén-Kallela. Among the Germans were Ludwig von Hofmann, Max Slevogt, Ernst Barlach, Georg Kolbe, Emil Nolde, Käthe Kollwitz, and Paula Modersohn-Becker. The better-known Frenchmen who attended the Académie Julian include Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Fernand Léger.

Each of Julian's branch academies consisted of a group of hot, airless rooms crowded with noisy students whom a massier —a senior student responsible for sundry tasks in the atelier—was expected to restrain from the most flagrant disorder. The walls of some studios were covered with palette scrapings and caricatures; others, more decorous, were adorned with framed student drawings; still others displayed signs with such famous pronouncements by Ingres as "Le dessin est la probité de l'art," "Cherchez la caractère dans la nature," and "Le nombril est l'oeil du torse."[43]

Corinth attended the "little studios" at 48, Faubourg Saint-Denis, where his teachers were Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) and Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911). On his arrival he was greeted with deafening noise, followed by caustic remarks intended to unnerve a newcomer. Troubled by the attention, Corinth though it wise to keep his East Prussian origins a secret and responded to his fellow students' insistent questioning about his background and training by implying that, having studied in Munich, he was a "Bavarois." He was formally initiated into the group at an "altar" of atelier stools quickly set up for the occasion, a ceremony recorded in an old photograph.[44] A few days later he was sketched in caricature on the studio wall in the uniform of a Bavarian soldier against a red background and with bloody hands. The pithy inscription under it, "Quand même" (in spite of everything), indicated that for his French fellow students he was still a German.[45] As it turned out, however, Corinth got along well with everyone, partly, it seems, because his massive build and unmistakable physical strength commanded respect. Yet le gros Allemand , as he was called, never formed a real friendship with any of the French students. Nor did he ever mention Gallén-Kallela, who studied at Julian's at the same time. His closest acquaintances included another East Prussian, Franz Lilienthal; the Bavarian Ludwig von Zumbusch; and four young Swiss painters—Emil Beurmann, Louis Calame, Emil Dill, and a fellow from Zurich named Blaas. In his memoirs Corinth disguised the identity of his friends: Zumbusch is von Sambitsch, Lilienthal is Blumenthal, and Beurmann is probably the Swiss Mauerbrecher. Dill, Calame, and Blaas are not mentioned, although the latter two are commemorated in portrait drawings.[46]

Corinth made up his mind to remain in Paris for at least three years "to learn whatever there was to be learned";[47] even after eight years of study in Königsberg and Munich he apparently believed he could progress further only at still another academy. Moreover, he resolved to return to Germany only when he had distinguished himself at the Salon.

Although he was in Paris, Corinth remained unfamiliar with the works of the French Impressionists. He arrived too late for the memorial exhibition of Manet at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, although he was in time for the next show, the large retrospective held in 1885 for Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose pseudo-impressionist brushwork and diluted colors may have embodied for Corinth the latest word in French modernism. On his frequent visits to the fashionable galleries of Georges Petit, a veritable sanctuary of academic art, Corinth admired the fabulous naturalism of Meissonier,[48] but since he spent the summer of 1885 vacationing in the Black Forest and that of 1886 on the Baltic seacoast near Kiel, he missed Monet's and Renoir's paintings at Petit's

fourth and fifth expositions internationales . Most likely Corinth encountered Impressionism only in the extreme form of Neo-Impressionism when in December 1884, seemingly by chance, he walked into the Salon des Indépendants,[49] where he saw works by Seurat, Signac, Guillaumin, Cross, and others, including a landscape sketch of the island of La Grande Jatte, a first study for Seurat's large painting.

Corinth's unfamiliarity with Impressionism is not really astounding, for French hostility toward German artists in Paris seems to have fostered a provincialism that did much to exclude them from the inner circles of the then developing avant-garde. Max Liebermann's earlier experience in Paris and Barbizon from 1873 to 1878 was similar,[50] although he must have known of the Impressionists, especially since Lepic participated in the first historic exhibition at Nadar's in 1874 as well as in the second Impressionist show in 1876.

Corinth, at any rate, craved the recognition only the Salon could confer. Having determined to remain in Paris until he had exhibited something at the Salon and possibly won at least a mention honorable ,[51] Corinth found his inspiration in the Louvre and in the Musée du Luxembourg, then the repository of important works that the French state had acquired from the country's leading academicians. The Académie Julian, too, seemed to offer a road to success. Corinth took particular pride in having peers like René Ménard and Etienne Dinet in the studio; both men were already hors concours , having sufficiently distinguished themselves so as not to require prior approval to exhibit their works at the Salon. And he was especially delighted to discover that the young history painter Georges Rochegrosse, whose painting of the slaying of Aulus Vitellius he had admired in Munich in 1883, was working in the neighboring studio of Boulanger and Lefebvre.[52]

Robert-Fleury's impact on Corinth's development is difficult to measure. In the course of his weekly critiques Bouguereau, however, soon developed a liking for le gros Allemand and after the success of The Conspiracy in London, saw that the painting was accepted at the Salon of 1885. Corinth rejoiced at this auspicious development. He wrote in Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben :

In all of Paris there was no one happier than the East Prussian Heinrich Stiemer [Corinth's pseudonym]. He was strutting around like a dandy and intended to get himself a genuine Parisian suit. He stopped in front of every shop to see what else he might buy; . . . each window reflected his massive figure in an entirely new light. "This then is the way a man looks on his first step to fame," he kept telling himself. He was sure now that he would catch up with that fellow Rochegrosse. That no longer worried him.[53]

Figure 14

Adolphe William Bouguereau, A Nude Study for

Venus , c. 1865. Pencil heightened with white,

46.2 × 30.3 cm. Sterling and Francine Clark Art

Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts (1578).

In his autobiography he wrote that acceptance at the Salon seemed "a promise for my art in the future . . . that everything would turn out in the best possible manner."[54] Unfortunately, his painting was displayed near the ceiling. It hung so high that it seemed to him no bigger than a postage stamp— and apparently had as little effect on the public and the critics.

Of the twenty pictures Corinth is known to have painted in Paris, no fewer than fifteen are devoted to the nude human figure—a considerable increase over the two nudes he had painted during his preceding eight years of study, the Crucified Thief (see Fig. 10) and a half-length female nude (B.-C. 11), apparently also done in Löfftz's studio in 1883. The comparatively large number of nudes from Paris is not surprising, considering the emphasis at the Académie Julian on working from the live model. According to Hermann Schlittgen, who studied briefly with Lefebvre in 1886, "If the better works reminded one of anybody, it was Ingres. . . . to represent the nude figure as correctly as possible . . . was the goal of everyone."[55]

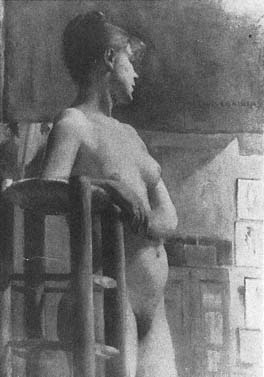

Figure 15

Lovis Corinth, Female Nude at Atelier Stool ,

1886. Oil on canvas, 73 × 50 cm, B.-C. 29.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

The nude was not only the focus of the curriculum at Julian's but also an important element in the oeuvre of Bouguereau, whose reputation rested on such a vast gallery of bathers and nymphs that some critics facetiously claimed he kept a studio of nudes the way others ran brothels.[56] Bouguereau continued the tradition of David and Ingres, except that he popularized the severe style of his predecessors by endowing his nudes with greater erotic appeal, an effect he achieved by allowing his models to retain a distinctly "real" look. The preparatory study for Venus (Fig. 14), one of the figures in the monumental ceiling decoration in the concert hall of the Grand-Théâtre in Bordeaux, is typical of Bouguereau's skillful combination of realism and idealization. The head is that of a contemporary woman; the body, however, is exactly eight heads tall, four each above and below the pelvic region.

Corinth's female nude of 1886 (Fig. 15) is one of several of his pictures that exemplify the careful observation of the human figure Schlittgen described. But in his drawings he generally moderated this factual approach by emulating

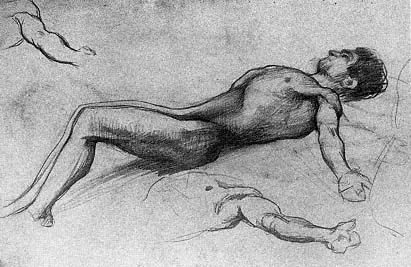

Figure 16

Lovis Corinth, Three Studies for

a Reclining Female Nude ,

c. 1884–1886. Charcoal and pencil,

44.7 × 29.5 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

Bouguereau's more agreeable style. Indeed, Bouguereau specifically encouraged Corinth to attend to his draftsmanship when he offered the criticism "Ce n'est pas mal, mais ce n'est pas bien dessiné" —an admonition Corinth never forgot.[57] Three drawings on folio 23 verso in the sketchbook in Kiel (Fig. 16) illustrate Corinth's efforts to idealize the figure of a reclining female nude. The rapid sketch at the bottom of the page is followed by a rendering in the center in which the figure's contours are indicated more specifically without suppressing the model's ample forms. In the uppermost drawing the body of the nude is charted once again in successive contours, but this time a reinforced outline reduces the awkward curvature of hip and shoulder to a smoothly flowing rhythm that gives continuity and greater refinement to the model's fleshy forms. In some drawings Corinth tried to work out a system of proportions like the one Bouguereau had used for the figure of Venus. In others, such as the study of a reclining female nude on folio 24 recto of the Kiel sketchbook (Fig. 17), he employed hatching and crosshatching and the alternative method of the estompe to give the figure added relief. The generally untidy execution, Corinth's inability to render the interplay of the limbs convincingly, and his consistent avoidance of such complex anatomical details as hands and feet confirm that Bouguereau's criticism was well founded.

This drawing, incidentally, calls attention to a practice popular among the French pompiers . By rapidly outlining a crouching male nude in the back-

Figure 17

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude (Study for Jupiter and Antiope ),

c. 1885. Pencil, 29.5 × 44.7 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

ground, Corinth transformed the original study of the live model, almost playfully, into a mythological composition. The mundane Parisian model has become Antiope about to be surprised in her sleep by Jupiter, who approaches in the guise of a satyr. Paintings of the nude had this particular advantage of being easily "finished" for the Salon by the addition of a few anecdotal details. Cabanel's famous Birth of Venus (1863; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and many a naiad by Jean-Jacques Henner are no more than paintings of nude models in which minimal accessories supply the requisite iconographic context. They are descendants of Ingres's La Source (1856; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and belong to a seemingly endless line of nudes shown at the annual Salons with predictable success. Both Löfftz's Christ Lamented by the Magdalene (see Fig. 9) and, as already noted, Corinth's own Crucified Thief (see Fig. 10) bear witness to the widespread popularity of this approach, although probably nowhere outside Paris was the custom pursued with the same verve. Bouguereau's painting of the Oreads (1902; private collection, Paris), which contains more than thirty-five such nudes, may be the most extreme example of this practice. Corinth, possibly inspired by Ingres's 1851 painting of the subject (Musée d'Orsay, Paris) as well as by Titian's problematic composition in the Louvre, the so-called Pardo Venus (c. 1535–1540/c. 1560), devoted at least six more pencil studies as well as an oil sketch (B.-C. 28) to the subject of Jupiter and Antiope. This composition may be related to the painting of a life-size

Figure 18

Lovis Corinth, Recumbent Male Nude , c. 1886. Pencil,

29.5 × 44.7 cm. Kunsthalle zu Kiel.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

"nymph" Emil Beurmann saw in Corinth's Paris studio, which he said Corinth was working on with the intention of sending it to the Salon.[58] This painting, if indeed it was ever completed, has long since disappeared. Corinth's hopes for it are suggested by his lighthearted gesture years later of repeating the composition where he concludes his account of the Académie Julian in Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben . There the recumbent nymph lies asleep as a satyr, now conspicuously goat legged and horned, approaches with manifest glee. To the ornate frame of the vignette is affixed a proud "Hors concours."[59]

Another motif Corinth was working on at this time was "a corpse of Christ on a red tile floor."[60] His brief but unequivocal description indicates his casual approach to the subject, and a preparatory drawing in the Kiel sketchbook (Fig. 18) confirms that this picture, too, was to have been an accurate, though somewhat idealized, study of a male nude whose posture would suggest the appropriate iconographic context. This drawing and the studies for Jupiter and Antiope suggest that Corinth's thematic interest was limited to a preoccupation with form as manifested in the model. Many years were to pass before he saw the human figure as a vessel of emotions whose expressive power transcended the impeccable rendition of nature as Ingres and Bouguereau understood it.

Whenever the students at the Académie Julian were not drawing or painting the nude, they were working on figure compositions that had to be completed without the aid of models. This practice allowed them to experiment with the arrangement of figures within a chosen format, to determine the distribution of light and shade, and to examine the effects of the colors they intended to use. Bouguereau, who saw to it that this practice was followed faithfully, usually posted a note near the studio door announcing the individual assignments. This might be a well-known but complex theme, such as "The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem," or something more erudite, like "The Scythian King Scylurus Admonishes His Eighty Sons."[61] Corinth's composition study of 1885, entitled Unity Gives Strength (present whereabouts unknown), derives from Plutarch's story, except that he reduced Scylurus's large family to five, a handier number.[62]

Several studies for a Lamentation, probably executed at about the same time, illustrate Corinth's efforts to achieve both variety and unity in a composition involving a similarly heterogeneous, though far less unwieldy, group of figures. They too demonstrate his continued reliance on the leading pompiers and can be traced to such prototypes as Henner's paintings The Dead Christ (1879; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) and Christ in the Tomb (1884; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lille) and Bouguereau's Virgin of Consolation (1877; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg).[63]

No other works from Paris shed further light on Corinth's early development. Those he completed in the summer of 1885 and 1886 while traveling in the Black Forest and in Holstein—landscape studies, oil sketches and more finished pictures of country folk, and two plein air portraits—are of only marginal interest. Most were conceived without regard to the tastes prevailing at the Académie Julian. In two exceptions from the summer of 1886, however— compositions known only from later descriptions—Corinth adapted his recent experience of working from the live model to plein air painting. He asked several old men from a home for the aged near the village of Panker in Holstein to pose nude for him in the woods, in the guise of Pan and other forest spirits. Corinth, oblivious to the men's physical discomfort in the brisk forest air, not to mention their reluctance to comply with his unusual request, apparently took delight in the effects of the sunlight flickering across naked bodies. Perhaps the forest interior of 1886 (B.-C. 43), in which a seated nude figure can be seen from the back, originated in this context. No other visual evidence has survived either of these plein air figure compositions or of a large picture Corinth painted inside the old people's home.[64] The men were smoking and reading; the women kept busy spinning or knitting. A soft glow, reflected from a wheat field just outside the window, pervaded the room.[65] Although Corinth

destroyed these paintings because he found fault with them, in the picture of the old people's home he had returned to the pictorial problem of interacting light and interior space that had first occupied him in The Conspiracy .

A renewed interest in this problem also prompted the lively figure composition Cardsharp (Fig. 19), one of the last pictures Corinth painted in Paris during the spring of 1887. Three cardplayers in a Paris bistro challenge and threaten a cheat; a waiter and an older man look on. Corinth, who had not exhibited at the Salon since the spring of 1885, may have hoped to repeat his London success with a work that offered a similar challenge, except that now he heightened the narrative suspense by emphasizing the transitory moment of the action, as Meissonier had done in a similarly charged picture entitled The Brawl (1855; Collection H. M. Queen Elizabeth II). Corinth's care in preparing the painting is evident from preliminary drawings.[66] It is not known, however, whether he submitted the work for acceptance to the Salon in 1887. In any case, the jury rejected all his entries, dealing him a devastating blow. This "misfortune," as he later called it,[67] led him to pack his belongings and return to Königsberg. He eventually destroyed the Cardsharp , apparently for the same reason that led him to overpaint the picture rejected in Antwerp.

Despite the disappointing finale to his studies in Paris, Corinth never ceased to respect the discipline he had learned at the Académie Julian, no matter how far his work digressed from the precepts of artists like Bouguereau. In his own teaching manual, published more than twenty years later, he repeatedly emphasized the importance of studying the live model and recommended that the nude be rendered accurately, as if it were but another three-dimensional object like those encountered elsewhere in nature in landscapes, animals, and still life.[68] This advice, true to nineteenth-century academic notions,[69] also confirms the nonpsychological approach to the human figure seen in Corinth's early drawings and paintings of the nude. Besides the concept of form exemplified in the live model, Corinth passed on to his students the principles of composition he had first learned at Julian's. To illustrate the "mental gymnastics" he felt every aspiring artist must learn to do, he published one of his Paris studies for the Lamentation in his teaching manual.[70] An artist approaching the story in Genesis 37:32, where the sons of Jacob bring their father the bloodstained coat of their brother Joseph, he explained, must begin the composition by visualizing gestures and expressions appropriate to the remorse and pity each of the brothers feels in anticipation of the old man's grief.[71] Even Corinth's good friend Walter Leistikow, in an amicable review of Corinth's teaching manual when it was first published in 1908, could not forgo an aside

Figure 19

Lovis Corinth, Cardsharp , 1887.

Oil; ground and size unknown, B.-C. 50.

Painting destroyed by the artist.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

about Corinth's eccentric approach: "Today, under the banner of Impressionism and a thousand other groping efforts to come up with something new and newer still, . . . Corinth writes a painting manual just as in the good old days when the blessed Saint Academicus was still absolute ruler in the realm of art."[72] When a year earlier Corinth's student Oskar Moll had told him of his plans to go to Paris to study with Henri Matisse, Corinth had gruffly replied: "What do you want to go to Paris for? The old Bouguereau is dead, and there is nothing new."[73]