2

The Premodern Heritage

Compared with their European and British counterparts, American cities retain far fewer characteristics to identify them with the very earliest cities. In fundamental ways urban Americans live in a New World. Modern U.S. cities, both in their pasts and in their prospects, have a dual relationship to the ancient city. On the one hand, they build, change, and evolve in seeming contradiction to and ignorance of all ancient traditions, taking as their models only one another. On the other hand, until as recently as the early eighteenth century, they had at least one foot anchored in the ancient past.

As social and spatial forms, cities have had a continuous 5,000-year history. That is, for the past 5,000 years there have been cities, even though no single city has been in continuous existence for that long. Damascus, with the longest history as a city, is some 4,000 years old. Millennia of human experience with cities has made their physical forms, their social traditions, and the conceptual framework in which we comprehend them all an essential part of our culture. Most people "know" and have "known" what cities are.

A long evolving growth in the understanding and imagery of cities has been disrupted and challenged in the past 300 years. John Winthrop used the then easily visualized metaphor of a "city upon a hill" in his famous sermon to the early Massachusetts Bay colonizers to give them a clear model of their enterprise. His metaphor is not quite so clear to us in the twentieth century, but for Winthrop's listeners, it evoked an image stretching back thousands of years before Christianity. If he had said "castle upon a hill," our instant image would be close to what he meant, for he evoked a

walled, defended city, busy and wealthy with trade, dominating transport routes and the surrounding agricultural lands and villages. The rise of the nation-state and industrial capitalism have transformed the urban landscape, so that virtually all the cities we know today differ radically from their historical predecessors. This is one reason Lewis Mumford could position the medieval city as a critical counterpoint to the modern city. Yet the way we think about cities is grounded in a history extending back well beyond the lifetimes of our own New World cities. To clearly see the city in its new forms, we must understand it in the context of the distant past. The very old and the very new must be held up together in order to build our historical concept of the city.

The Classic City

Social scientists have termed the simultaneous emergence of the city and writing, around 3000 B.C. in what is now Syria, the "urban revolution." This revolution was facilitated by two elements necessary to ensure a regular and permanent urban form. The first, a self-sustaining and self-conscious bureaucracy, represented and effectively implemented the power of the state. And the second, writing, enabled the encoding and transmitting of state power both across space and through time. Writing, of course, was most effective when generalized and exported at the least to the geographic perimeters of a city's influence. Without its writing system a city could not transmit orders effectively, remember transactions, establish or enforce distant property relationships. The state, a regular and organized system of finance and defense, had to inhere within the city walls, and the actual walls formed an important part of the state's working system. Without its walls, a city could not protect its inhabitants, its economic base, or its power to extract taxes. These two prerequisites for urban life, a state and writing, in turn fostered those activities we more usually associate with city life—religious leadership, intellectual advancement, commerce, warehousing, industrial or craft processing of varied bulk materials, and specialization in a broad range of human endeavors.[1]

The city represented privilege and power, even for its poorest and most powerless inhabitants. Until the rise of the nation-state, rural peoples always lived with an element of danger, whether from

attack by bands of robbers, invading armies, or members of the local military. Additionally, the vagaries of weather, of crop failure, and of natural disaster always threatened. Rural life never had the variety, complexity, and richness represented by city life. In contrast, the most menial inhabitants of a city shared its military protection, enjoyed the benefits of an economic life more predictable than that on the outside, and participated at least marginally in the city's rich and varied life. The image of the rural took on the positive aspects so familiar to us only as cities became the dwelling places for the masses in the eighteenth century. Thus, in the western world, from 3000 B.C. until about 250 years ago, city dwellers constituted an elite class.

Once achieving its urban locus, state power could attain a high level of permanence and stability, which in turn enabled the state to exact taxes regularly on the surrounding countryside. We often imagine that cities emerged naturally as agricultural productivity increased and liberated a proportion of the population to join the urban workforce. However, recent research has established that a level of agricultural productivity high enough to support a nonagricultural, urban population had been present for a long period before the urban revolution. In fact, the best evidence hints that even preagricultural hunting and gathering societies have the physical potential to produce food surpluses. The technology of food production did not in itself create the capacity for city growth. Rather, political organizations enabled and encouraged technologies to support non-food producers—city dwellers. The urban revolution brought about for the first time an efficient means of levying taxes. City-based political organizations extracted surpluses from food producers, rather than allowing them to produce less and have leisure time.[2]

The urban revolution created permanent cities, and it also gave them their basic look. Walls were a fundamental and distinctive feature of the city, as necessary as people. Visually distinct from the surrounding countryside, walled cities looked like spreadout castles, which in fact they were. Massive stone walls and embankments made them defendable, and a limited number of entry gates ensured that relatively few officials could control and tax those entering or leaving the city. Because the cost of building and maintaining walls was enormous, city officials limited their circumference: hence city areas tended to be compact. Walled cities

persisted as the major form of urban settlement until about the sixteenth century. That the appearance of cities changed so little in almost 4,500 years testifies to their efficient design and functionality. That it has proved so volatile in the modern era testifies to the city's new and multiple functions.

The Rise of the Nation-State

It may be argued that there have been no more than two dramatically different kinds of cities: the first, which incorporate the apparatus of the state, and the second, which do not. The physical shape, political structure, and economy of the first type of city cannot be separated from its nature as the state: centralized, rationalized, and regularized political power. About four centuries ago, the state began to escape from its urban base, leaving behind the modern city and changing forever the nature of both. Nothing symbolizes this split better than the palaces of the two Western monarchs who also began the political construction of the modern nation-state. Louis XIV built his palace, Versailles, near but not in Paris; similarly Henry VIII located his Hampton Court Palace near, but not in, London. In a sense, these two monarchs recognized the need to "capture" and appropriate the political and military power of the city.

This dissociation of the state from the city slowly beginning in the sixteenth century marked a significant dividing point in world urban history. Customarily the rise of the nation-state from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century is cast in the conceptual framework of politics and economics. But it may be more useful here to regard the growth of the nation-state as both freeing the city from its limiting burdens of statehood, and at the same time subjugating it to a state with often separate and conflicting interests and goals. A particularly liberating influence, for instance, was the greater flexibility cities gained once they no longer had to be large enough to support a permanent military. The only precedent for this had been almost 2,000 years earlier, when the Roman Empire had allowed secondary, specialized cities to develop, but the decline of the empire left such cities vulnerable. The rise of the nation-state achieved similar results: small cities, specialized cities, undefended cities could thrive. They invested their limited resources elsewhere than in costly walls. Nonhistorians like Mum-

ford often link the rise of the modern city to the industrial revolution, even though historians of that revolution stress its rural nature; this erroneous thinking occurs because all these broad changes did have many interrelationships and because city history is almost never considered in the political context of the nation-state.[3]

This dichotomous world urban history has a demographic and economic analog. When cities embodied the state they probably never held more than 3 to 5 percent of the total population of their geographic region. When the state and the city separated, the proportion of people dwelling in cities began its drift upward. And although cities retained their power as centers of economic activity, particularly commerce, factories and industrial enterprises began to appear in the countryside, near sources of water power. Industry never had quite the same powerful ties to urban centers as commerce did, and an uneasy relationship between the two existed from the time of the earliest factories up to the present, when automobile manufacturers are more likely to build new factories near small towns than near large, "industrial" cities.

In other words, until the transition that had begun by in the seventeenth century and still continues in some regions of the world, fewer than one person in twenty had ever experienced urban life. It has been pointed out that the preurbanized world was one where few people ever even saw a crowd of strangers, much less lived in proximity to them. Today, in contrast, the number of people who experience solitude, or spend their lives in small communities where everyone knows each other, has diminished to tiny proportion. In some parts of the United States, the ratio of rural to urban dwellers has almost completely reversed the long-standing and ancient norms, so that in New Jersey and California, only one person in ten lives outside of a city. And 17 million people, a population not reached by England until the middle of the nineteenth century, live in the metropolitan region clustered around New York City.[4]

The Colonial Fringes

In the seventeenth century the North American colonies made their modest urban start, just at the moment when what might be termed the second urban revolution had begun. Like the first rev-

olution nearly five thousand years earlier, the second had a political basis, one that used and encouraged technological change to create new urban forms, which in turn organized and perpetuated new forms of state. In the nation-state, the city finally became the primary residential site for most of the population, and agriculture became an industry like any other. In a sense, the city itself became a part of the technological and economic apparatus during the second urban revolution.

In any economic system not based purely on subsistence agriculture, the city has built-in advantages for many economic activities. It has economies of scale—the lowered costs of economic activities which can occur when performed on a large scale—and economies of agglomeration—savings which are made possible when economic activities take place near one another. For instance, a cluster of several or many waterpowered mills fosters specialists in waterwheel technology. Likewise, shipmakers who have access to nearby moneylenders can more easily finance new ventures than those who do not. City-based economies of scale and agglomeration encourage an exponential increase in communication and creativity. In nineteenth-century America, inventors clustered in medium-sized cities; Yankee ingenuity apparently did not find rural places as fertile as urban ones.[5] In the new kind of cities, change became the constant, so that urban forms, institutions, and populations reorganized quickly and sometimes unpredictably. Recently, for instance, the rise of "doughnut" cities in the northeastern United States—cities with abandoned inner cores—has reversed all prior expectations of urban shape; rarely before would one have found the city center abandoned.

American colonists began building their cities at a time in world history when it was possible to break sharply with the past, helping to assure that premodern forms of urbanization would not occur. Had the colonization occurred, say, in the thirteenth century, the resulting cities might have taken settlement forms more like medieval British country towns. But to the extent that the state and city were still intertwined in the seventeenth century, London, Paris, and Amsterdam asserted their metropolitan dominance over the colonies. Consequently, the premodern model of city growth never made a lasting imprint upon North America. And because the conquest and colonization of the North American continent occurred as an aspect of the creation of European nation-

states, the colonies grew under the protective wing of major empires in a kind of stateless limbo, a rare circumstance. Within a few decades, the Constitution, although written to ensure a nation-state with decentralized power and to protect a land of farms and villages, nevertheless provided for the expansion of a highly urban nation. Jefferson's often cited antipathy to cities as "sores on the body politic" came out of this vision of a nation-state independent of cities. And when, by the mid-nineteenth century, urban entrepreneurs could avail themselves of the military and economic protection of a new nation-state, they did so with unprecedented gusto, quickly building a system of cities on a new basis.[6]

In fact, much as they might have desired otherwise, Europeans colonizing the New World could only partially replicate the world they had left behind. Their failure to reproduce their former urban environment exactly encouraged change and forced innovation. These deviations from tradition were to become important, even though up through the nineteenth century American cities would appear to be no more than inadequate imitations of the "real things." To cultures incapable of understanding the new forms of cities under construction, the innovations could be interpreted only as chaos and confusion. Almost from the outset the New World cities differed from the traditional city, which made them difficult for Euro-Americans to comprehend or analyze.[7]

Colonial City Form

Colonial cities did have to attend to self-defense. Most important, they had to have militias, entailing the election of a drummer "to doe all Common service in drumming for the Town on Trayning dayes and watches." Not until the constitutional government of the United States was established did they lose this responsibility. But colonial cities avoided the customary city wall systems that required costly capital outlays in the Old World. Certainly New Amsterdam had its famous wooden palisade, which gave the world a Wall Street. But this wall resembled more the temporary stockade of a military outpost than the full-blown walled cities its Dutch settlers had known. Eighteenth-century St. Louis, which the French fortified in 1780 with a ditch, wooden palisade, and stone gates, had some of the appearance of a walled city, but the wall quickly disappeared when the city began to act

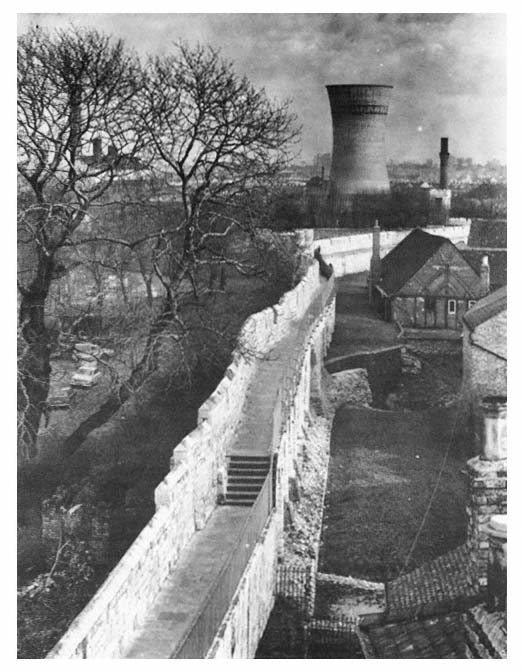

York Wall, Cross Section.

York's impressive wall, in this cross-section, reveals a succession of

fortifications since Roman times. The diagram of York's wall suggests just

how costly and formidable the medieval city wall actually was. It is no

wonder that they stood long after they were no longer needed, even though

their surfacing stone was valuable and thus often hauled away for other

building purposes.

Source: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, An Inventory of the Historical

Monuments in the City of York, vol. 2, The Defenses (London: RCHM, 1972), 114.

York Wall Today

A tourist attraction in contemporary York, this photograph suggests the

wall's monumental presence in a medieval city.

Source: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, An Inventory of the

Historical Monuments in the City of York, vol. 2, The Defenses

(London: RCHM, 1972), pl. 41.

an entrepôt rather than as a fortified trading post on the hostile edge of the French empire. Using deliberately loose criteria, one geographer has identified a total of eleven settlements in the United States that had some form of fortification, but after the most generous allowances he concludes that the lack of influence of walls "may be a characteristic feature of cities in the United States."[8] Certainly no American city invested in the enormous capital infrastructure represented by the massive and sophisticated wall systems of British and European cities.

Max Weber in The City argued that the rise of the modern city helped foster a spirit of capitalistic individualism. With this flourishing came a concurrent decline in the distinctive cultures of individual cities and of individual identities tied to these cultures.[9] The liberation of the city from the demanding requirements of defense and autonomous statehood made possible a new and far less responsible role for the individual in the fabric of urban life. American cities epitomized this tendency. Throughout the colonial period cities decreased their demands on the individual as citizen and urban resident and created a laissez-faire economic and social environment. Dubbed "privatism" by Sam Bass Wamer, this spirit made cities the stages on which individuals and interest groups pursued their own private goals.[10] The new freedom from the responsibilities of statehood thus affected the individual within the city as well as the city itself. One result of this increased individual freedom was an inconsistency and irregularity in the appearance of cities.

The absence of traditional city forms made colonial American cities seem ugly, chaotic, and scattered to European visitors. Colonial cities did not even have names for their streets. In addition to their confusingly unconventional appearance, these New World cities were probably even smellier and dirtier than their British counterparts. Poor urban families raised pigs, which wandered the streets. Though prohibited by ordinance by the end of the eighteenth century, at least in Providence and New York City, pigs foraged freely well into the mid-nineteenth century. They thrived on the garbage, and on the animal and human excrement in the streets. In order to promenade, the elites of Boston and New York created special parks in the mid-eighteenth century, where railings excluded the omnipresent pigs, horses, and oxen.[11]

Excepting those few cities that had temporary walls, American

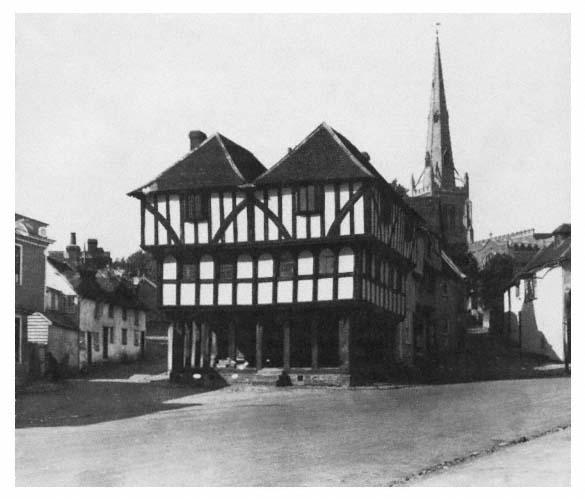

Thaxted Guild Hall, fifteenth century

The Thaxted Guild Hall was used as a market and town hall for this small,

unfortified market town. Market buildings such as the Thaxted Guild Hall

make an appropriate emblem of the city's political and economic functions.

Guilds and other groups of the city's governing bodies met in the

upper rooms, markets could be held in the open areas, and often the

buildings contained a jail.

Source: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, An Inventory of the

Historical Monuments in Essex (London: RCHM, 1966), 1:313.

cities did not even have proper boundaries demarcating their edges.[12] Ultimately, though, their very formlessness heralded a new era. Try as they might, they could not repeat British or European models. Even though their own image of what a "real" city should look and act like derived from English antecedents, colonial cities had to struggle to maintain even the barest of appearances. At the Newport Town meeting in 1712 it was argued that: "It is a universal and orderly custom for all towns and places throughout the world when grown to Some considerable maturity by Some general order to name the Streets, lanes, and alleys thereof."[13] The city had unnamed streets and to muster support for naming them, it had to appeal to its citizens' sense of world order and propriety. Neither reason nor tradition alone sufficed.

Colonial urban America's most important contribution to future urban development was, in a literal but quite important sense, negative. When the United States expanded in the nineteenth century, it had no ancient patterns of urban political dominance to stifle change and growth. Of the early cities, New York and Boston retained much of their preeminence, but neither retained exclusive rights typical of British and Continental cities. Neither had trade monopolies. Neither had extensive property rights beyond its boundaries. Dissenters of any kind could simply move elsewhere—and they did. Intracity trade competition reflected the cities' lack of broad chartered powers. Just as New England towns could not prevent political splits from turning into literal fragmentation, with dissidents forming new towns, New Yorkers in the early nineteenth century could not stop the upstart new city of Brooklyn.

Even when tradition was consciously followed, modifications created new forms in the colonies. Early city government often took strange turns. One case in point is the justly famous town meeting, which evolved from Boston's government in the 1630s. This new, potentially democratic form of local government derived from congregational church governance. Both mimicked local church and government in England, where the church vestrymen had administered much of the local law, and where the church governance had represented the village oligarchy. The transformation in the New World came from the rejection of the church hierarchy. The basic form of government remained, but the power now rested in the hands of all church members. Thus tradition, when combined with some slight variation in the composition of

the local church, could create a city government quite unexpected in form.[14]

New World Urban Patterns

Colonial cities did exhibit a systematic pattern of dispersal, of spatial arrangement with respect to one another, but they showed no signs of the remarkable urban transformation that would take place west of the Mississippi in the nineteenth century. In the colonial period there were small but functionally important cities with a scattering of smaller places: an unpredictable array of settlements preceded the predictable hierarchical ordering of village, town, city, and metropolis that would come to characterize the nineteenth century.

Five important urban centers existed in the colonies by the early eighteenth century, each dominating its coastal region. These cities supported no carefully articulated network of smaller places: they tended to engross all possible urban activities. Until about 1820, for instance, Philadelphia's "preponderance hindered the growth of other towns." Only those backcountry areas separated by land (rather than by navigable waterways) escaped the pull of the big city and developed urban functions.[15] On or near the coast, Boston, Newport, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston often had closer ties to London than to one another. Each linked their agricultural hinterland with London merchants and markets rather than forming a single American network. During the colonial period, each city's commercial and transshipping facilities reflected the individual character of the people and agriculture it served. From Puritan Boston to the somewhat more tolerant Newport, from Dutch New York to Quaker Philadelphia and Anglican Charleston, each city served as an undifferentiated service center, concentrating legal, mercantile, and shipping services and colonial wealth in a seaport entrepôt.

These colonial cities did not form a coherent hierarchy. As the geographer Walter Christaller proposes, one expects a mature urban network to form a set of interlocked hexagons, where urban centers of diminishing size, complexity and hinterland array themselves like a honeycomb around one another.[16] In such a system one would expect to find differentiated services at each level of urban settlement, with the urban network itself promoting opportunities

for singular economic specialization. In the colonies, the economic specialization of nineteenth-century factory towns like Lowell, Massachusetts, for instance, was nowhere to be seen, with the exception, perhaps, of a fishing port like Nantucket. Nor, while there were some smaller cities, like Nantucket or Salem, did the colonial cities conform to the spatial and power relationships that would order nineteenth-century urban geography.

Modern geographers conceptualize cities as being systematically related to one another within a spatial network of social and economic ties. Cities, in this view, exist in mutual interdependence, exerting as much, or more, influence on one another as they do on the surrounding hinterlands. This systematic perspective of regional geographers apprehends whole regions of cities and towns as aggregates of actors, radically dissociated from the immediate countryside. "The most immediate part of the environment of any city is other cities," Brian Berry asserted in the early 1960s. The questions such geographers address, not surprisingly, have been mainly oriented toward nonhistorical problems and explanations, testing, for instance, various hypotheses explaining urban hinterland formation or relating central communications dominance to the advantages of central urban locations.[17] In some ways this approach resembles the urban biographies writ large, for the notion of a city as one actor in a regular system of actors is indeed anthropomorphic. By looking at cities as aggregates of actors we can build a systematic, descriptive account of the development and change in the larger urban system, though it should be clear that such a historical description makes no claims to scientific status, unlike regional science, which studies the economic geography of cities and regional city systems.

Within this systematic geographical framework the two basic modes of urban history may be incorporated: the new urban history, with more comparative and structural concepts, and urban biography, with its greater emphasis on unique locales and site characteristics. For instance, contemporaries made much of the rivalry between St. Louis and Chicago in the 1850s and 1860s. The major western city of the 1840s and 1850s, St. Louis nonetheless lost in the growth contest to what at first seemed like an upstart, Chicago. Both grew astonishingly. The population of St. Louis leapt from 16,469 in 1840 to 310,864 in 1870; that of Chicago exploded from 4,470 to 298,977 in the same decades. St. Louisans correctly

read the growth rates as portents of Chicago's bigger, hence brighter, future. By the turn of the century, Chicago had expanded almost six times, to 1.7 million people. St. Louis had not quite doubled, to somewhat under 600,000, and it was already lamenting its failure to become the population center it had aspired to be. This decline continued and by 1980, the city's population had actually decreased to 453,000, though its metropolitan area was home to 2.3 million. But although they competed for railroads, immigrants, and business, Chicago and St. Louis also needed one another. In the long run, Chicago's port and market benefited St. Louis, even though St. Louis no longer occupied its preeminent frontier position. Both cities grew together, mutually benefiting each other through the flourishing network of smaller cities and farms, tied by equally thriving water and rail transport, which grew between them. Both needed smaller cities, towns, villages. And even the most rural dwellers and farmers needed the cities. One study, for instance, has shown how the farmers surrounding mid-nineteenth century Madison, Wisconsin, choose to settle nearer rather than farther from town.[18]

Schematized by German geographers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the notion of urban networks has considerable relevance in helping us explore the dynamics of American urban expansion. Yet some of the more rigid theorizing of these geographers and location theorists lacks any historical sense and displays little relationship to reality.[19] Sometimes the models seem more prescriptive than descriptive, but they can nonetheless aid in historical understanding. A model that stipulates how cities should have been located, what size they should have attained given their location, and what their economic functions should have been, gives us some context in which to place the cityscapes that actually unfolded. The concept of networks does not so much attempt to explain, but rather to highlight and describe critical shifts in the structure of the city world, especially the kaleidoscopic urban changes of the nineteenth century.

There are two basic kinds of urban network. The first is not so much a network as a one-city system, with a primate city that dominates a region usurping all major urban activities and leaving an atrophied network of villages. Nineteenth-century Paris, for instance, contained the major financial, commercial, cultural, and political enterprises in France, and was the largest single place of

manufacture. It had a population of over a million people in 1850, five times greater than that of Marseilles, the next largest city. London, ever an anomaly, dominated Britain and indeed much of the world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although it never contained the heavy industrial and factory enterprises that we associate with many cities in the United States, its financial and mercantile services made it the center of the Western economic sphere. Primacy is not just characteristic of London and Paris: certain third-world cities today loom in disproportionate size and importance over all other cities. Mexico City, for example, had a population in 1980 of almost 15 million, six times greater than that of Mexico's second largest city, Guadalajara. In contrast, New York in 1983 was only slightly more than twice as large as Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States. And none of the three largest U.S. cities—New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles—is a predominant political center, as true primate cities are. While Americans are often aware of the dominance of big cities, they have not experienced the almost complete dominion of a true primate center, which draws politics, economics, culture, and population disproportionately to one place.[20]

Metropolis, City, Town, and Village

The second basic network, the fully developed urban network, in contrast to the primate city's dominating position, contains four functionally distinct kinds of cities and villages, all spatially, socially, and economically interrelated. The network centers on the metropolis, which by virtue of its central location has communication and transportation advantages over other cities. New York City, for example, had developed communication advantages over other coastal cities by the late eighteenth century, even when Philadelphia was still much larger. This superiority meant that information moved more quickly to and from New York than to cities often much closer to the source, whether abroad or within the United States. New York maintained this critically important commercial advantage into the nineteenth century. In 1817, for instance, it took information almost 25 percent longer to travel between New Orleans and Charleston than between New Orleans and New York.[21] By the middle of the nineteenth century New York's commercial dominance was clearly established, but the

communications advantages with which the city began marked it as a place of critical metropolitan importance.

In addition to its communications advantages, in an urban network the metropolis attracts any activity that is best carried out in a single location, whether the activity is military, political, religious, social, intellectual, or economic. The resulting growth gives the metropolis economies of scale and agglomeration. Therefore, economic activities that are more efficient on a large scale do best in metropolitan markets. Perhaps more important, the unique advantages of proximity mean that economic specialization and interaction can take place more readily in a metropolitan environment. The merchants' coffeehouses of eighteenth-century New York, for instance, epitomized these metropolitan advantages. In them merchants found shipping information, met potential trading partners and customers, and exchanged essential commercial information. By the mid-eighteenth century, New York City had a range of mercantile services that served shipping and attracted further business through specialized partnerships.[22]

Next in functional rank below the metropolis comes the city, symbolically mapped by geographers at the six points of a large hexagon around the metropolis. In a nation-state it is easy enough to imagine these cities as regional economic and political centers. The city has many specialized functions, lacking only those central activities which must be singular, a Wall Street, for instance. The city still offers economics of agglomeration and scale, though it cannot support the wide range of very specialized services in the metropolis. Thus it may have some specialized services equivalent to or even superior to the metropolis—medicine perhaps—but it lacks other specialized activities—international trading, for instance. Unlike the metropolis, which has an influence on the whole urban system, perhaps even a large portion of the world, the city has a more limited range of influence, extending only to that of the next city in the hexagon. This is why the city cannot have singular specialization as the metropolis does, for it lacks the complete communications and direct relationships necessary to have comprehensive and effective coverage.

Each city is surrounded by towns, again mapped as the points of smaller hexagons. The range of services and degree of specialization of each town reflect its even more limited hinterland, and hence more limited population. Towns may have some economies

of scale, but fewer economies of agglomeration. One expects them to have few specialized services, though a town may exist only to support a specialized economic activity—a mining town, for instance. A town may do some simple processing of raw materials, but more complex processing goes to the city. Even the new factories being built away from heavily industrialized regions in the 1980s—the Honda factory near Marysville, Ohio, for instance—are essentially just assembly plants.

Finally, arrayed around the towns are villages, places that provide only basic goods and services. They may have almost no economies of scale, and supply only simple marketing, perhaps some legal services, and schooling. They serve a limited area with a range of very basic services.

If we imagine the activities of a mid-nineteenth-century Ohio farmer, we can illustrate the functions of this four-tiered urban hierarchy. Probably weekly the farmer would have gone by wagon to the nearest village for short-term supplies, perhaps market news, or to attend church. The village was a good place to talk with other farmers and get political news. There might also have been a secondary school and a doctor. Probably he would have hauled his crops by wagon to the village to sell them, for by mid-century it was quite likely there would have been a railroad spur or a small canal, and grain elevator.

Monthly, perhaps, the farmer and his family might have gone to the nearest town in order to buy bulk supplies, more specialized equipment, clothing, and household items. The town probably had a flour mill and a brewery. Certainly the town's merchants would have also supplied the village businesses, and the town might well have been a center for legal and political services. Perhaps it would have been the county seat, with the court house.

The farmer may have visited the nearest city only once a year. But the city's influence would have been pervasive, for it wholesaled to all the towns and villages, trained medical and legal specialists, had central exchanges for the sale of agricultural produce, processed agriculture products, manufactured agricultural implements and furniture sold in the towns, and performed a host of specialized economic activities.

Probably the farmer would never have gone to the metropolis, far-away New York in the early part of the century, Chicago in the latter part. But many of his children might well have migrated

there, traveling first to the nearby town, then the city, and finally Chicago, in search of jobs. And the city and town merchants certainly made trips to the metropolis. More important, their economic activities were filtered through the metropolitan center. Credit for major loans, for instance, often depended on metropolitan bankers and credit-rating services. And the agricultural goods, processed in the city or in the towns, often traveled to distant customers via the merchandising and shipping of metropolitan concerns, which produced the ships, directed the railroads, and coordinated the distant sales arrangements.

Thus, although the metropolis may have been invisible to the farmer, the urban network's influence pervaded both rural and urban life. Often its influence was manifested in antagonistic attitudes, people in rural places critical of the city's moral corruption and artificiality, and urbanites cynical about their simple country cousins. But these contrasts simply articulated aspects of the urban network which penetrated both rural and urban life, influencing occupational and residential choices and providing the very fabric of national economic life.

By the mid-nineteenth century, what is known to geographers as the rank-size rule obtained.[23] This rule predicts that in a large region, there will be one large city, several medium-sized cities, many smaller ones, and a plethora of villages, so that as the cities decrease in size ranking they become more numerous. Rank-size ordering stands in contrast to the distribution within a primate city system, in which one large city dominates and there are just a handful of smaller cities or villages. Instead, rank-size describes the honeycomb distribution typical of the four-tiered urban network-metropolis, city, town, and village—that established itself in the New World.

Colonial Cities: Between the City-State and the Nation-State

The strange urban network of the colonial era was neither a portent of things to come nor a remnant of the feudal old world. It remained a unique and relatively static order which lasted about 150 years. In his pioneering study of the five major colonial cities, Carl Bridenbaugh tended to lump them together. In so doing, he unintentionally highlighted an aspect of colonial urbanization that

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

symbolized its transitional nature, its temporal location between the millennia of the city-state and the coming era of the nation-state. Charleston in the south, Philadelphia in the middle, and New York, Newport, and Boston to the north all displayed social, economic, and Vocational similarities of theoretical importance, similarities that slowly disappeared in the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth (see table 2). In each city, a commercial class dominated affairs. This class defined itself in relationship to the metropolis of London and to a larger world of commercial centers. In its very name, one of Boston's two major seventeenth-century coffee houses for merchants, the London Coffee House, identified itself with the metropolitan center of mercantilism. And into the early nineteenth century, the

merchants of New York were an aggressively international group, both hosting their agents, "commercial exiles," and sending them out to a far-flung commercial world.[24] In the colonial era, the notion of an American urban hierarchy, of one city dominating the others, of competition between them for more business, never matched that which emerged later. So long as London and European cities dominated world trade, each American port related directly to transatlantic cities rather than to other U.S. cities.

In the colonial period, interurban specialization reflected little more than regional agricultural differences, from lumber and livestock in the North to tobacco and rice in the South. This suggests that uniquely urban economies had not yet begun to affect American city development. That is, given the economic advantages automatically accruing to cities because of their size (yielding economies of scale) and the combination of different activities (yielding economies of agglomeration) we would expect cities with initial advantages of size or location—New York or Philadelphia, for instance—to have begun early on to specialize and thus to have offered economic advantages over other colonial cities, even over distant London. This eventually did occur, but not until the end of the eighteenth century, when New York had begun to achieve its significant communications advantage over Philadelphia.[25]

That it took over a century for this specialization to develop suggests how different the colonial American cities were in their very nature from the New World cities of the nineteenth century. Truly the products of a time of major historical transition, colonial cities were the far-flung outposts of an empire which had as its center an ancient walled city—London—and which exercised primate dominance, though it no longer resembled a city-state, but rather a nation-state. Nothing makes this more evident than the lack of a single primate city at the beginning of the eighteenth century, or the communications dominance which New York achieved while still smaller than Philadelphia. England's colonial outposts in North America would eventually recreate the nationstate, but for U.S. cities there would be an enduring difference: the walls, traditions, and primacy of London would never take root in the North American urban scene.[26]

When one looks within colonial cities, their somewhat anomalous transitional status becomes even more evident, for they lacked the powerful guilds of English cities, but had not yet de-

veloped various newer modes of organizing power. In fact, in many ways they resembled English villages in their governance. No American city ever had the independence of cities with ancient charters, like London. The charters of many British cities, deriving from the early Middle Ages, gave them independence from state interference which lasted well into the period of the nation-state, though in somewhat diminished form as urban expansion occurred outside the old corporate boundaries.

London, and other chartered British cities, derived independence from their corporate status, which provided members of the corporation—the mayor, council members and various guilds—with highly concentrated power. By the eighteenth century London's corporate holdings and power expanded for miles around the chartered City. The powers of the City, itself only a mile square, extended well beyond the bounds of the old city walls, compounding the problems of governance, provision of services, and power. By the early nineteenth century, the Corporation of the City of London regulated Thames shipping for eighty miles, collected coal duties over a radius of twelve miles, and monopolized market rights over a seven-mile area. It vigorously protected these privileges, frustrating the governance of the metropolitan area, which extended for miles beyond the medieval city.[27]

American colonial cities, however, were able to act much more independently than many of the newer English manufacturing cities, which, like Manchester and Birmingham, lacked ancient charters and therefore had subordinate legal and political status. Their lack of any meaningful self-government contrasted dramatically with a London or Liverpool's independence. In the nineteenth century, the manufacturing elites of England's industrial cities had to struggle to achieve some political autonomy in order to accomplish the most modest aspects of urban governance. For instance, legislation in the 1830s authorizing English cities to create their own police forces affected neither Birmingham nor Manchester, where old manorial authorities resisted local efforts to create modern police forces.[28]

The powers of ancient charters, exerting significant constraints on nineteenth-century urban settlements, never seriously frustrated American cities. One might say, as historians used to say of the colonies themselves, that colonial American cities developed under conditions of benign neglect, for the political rela-

tionship of importance was between individual colonies and London. In colonial America, agricultural land defined wealth and status. Those who achieved urban wealth, like Boston merchant Thomas Hutchinson or the merchants of Salem and Charles Town, used their wealth to buy land, the "real" wealth of the colonies.[29] Their image of a proper city still looked back to the medieval city or to a world metropolis like London, to their formal pomp and visual displays of power in processions, costume, and legal jurisdiction—things that were clearly lacking in colonial cities.

Small places like Boston or New York were neither powerful enough to threaten the independent power of the colonial legislatures nor economically central enough to be seen as something special. Yet even in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries they actually were quite special, more so than the English provincial capitals with which their size and economic functions compare.[30] In retrospect it easy enough to see New York's natural economic advantages: its central coastal location, its year-round deep water harbor, and the Hudson River tapping a rich hinterland.[31] To see New York this way comes easily now because we no longer consider the east coast of North America as the trading fringe of a world centered in London, Amsterdam, or Paris. But in the seventeenth century, New York was, like Boston and other colonial cities, a colony planted on the edge of the wilderness, on the extreme edge of the world, underrated and ignored.[32] Today, the only comparable human colonizations would be those in Antarctica or perhaps those proposed for the moon.

The Legacy of Colonial Cities

For twentieth-century urban America, the colonial period's major political and legal significance can be termed negative. The actual foundations of colonial cities did not provide models or even guides for what was to come, even though the colonists tried to reproduce their legal and political heritage. But, in their failure to reproduce European precedents, they provided a legal and political tabula rasa. The modern U.S. city does not have a linear, direct, or mechanical relationship to its colonial predecessors. But underlying conceptions that ended up making a significant difference to nineteenth- and twentieth-century urban development can be traced back to the colonial era. These legal and political ideas pre-

ceded even the barest hint of the modern city, demonstrating one of the themes of this book, that the foundations of modern U.S. cities were created unintentionally. These legal foundations were not conceived with the intention of buttressing the entrepreneurial cities of the nineteenth century or the bureaucratized entities of the twentieth century. Rather, they were conceived by a society in the cultural and intellectual center but on the physical fringe of Europe. The ancient city's heritage simply could not have very much impact in the New World.

When nineteenth-century Americans celebrated their escape from the feudal grip of Europe, they unwittingly celebrated the foundation of twentieth-century urban sprawl.[33] Colonial cities differed from their European predecessors physically as well as legally. The tiny and fragile settlements that were to become the seaports of the muscular New World two centuries later never had more than wooden palisades and ditches. The wood quickly rotted away and the ditches filled with rubble. No American city saw real defenses, twenty feet thick at the base, faced with smooth, finished stones, carefully engineered gatehouses, all fastidiously designed to resist sieges. Lacking such impenetrable boundaries, they had from the beginning a powerful influence countervailing the traditional city's power to control its own internal shape. This influence, land with no physical barriers, ensured that the city's outer limits were unfixed, receding, and therefore unpredictable. Only the center, a geometric concept, could be considered fixed.

It had not been uncommon for walled cities of the ancient and medieval world to spill over, in the sense that people lived and worked outside of the walls. Residential and economic development that was functionally urban also occurred outside of city walls. But those people on the outside did not share the same urban benefits as the privileged inner inhabitants of the city. They lacked political and economic power, holding no hope of ever becoming members of the city corporation. Politically, economically, and practically this aspect of city life stayed extra-urban and truly marginal until the late eighteenth century.[34] Walls put a definable edge on the city, which limited its horizontal expansion and flexibility much more than American cities were ever to experience. That those people who threw up shacks or shops outside the walls were defined as extra-urban suggests the rather precise limits to a walled city.

Flexible boundaries created new and unforeseen opportunities for American cities. As is evident in the colonial land grants that specified vague western boundaries, edges did not make as much sense in the New World as they did in the Old. Apparently cities could expand indefinitely, as did the colonial land grants and the individual land grants made by towns. Often when New England villages suffered divisive political splits, one faction simply moved away, founding a new village within a day's walk from the old one. Only capital and population limited the exploitation of the seemingly endless resource, land. And because traditional city walls represented an enormous capital investment, their absence freed capital for other uses. Most important, without defined and limited edges, American cities lost a critical constraint affecting their planning, the absolute need for control which walls had imposed. The external boundary of a city wall and location of gates had required cities to make explicit locational decisions; unwalled cities no longer faced such decisions. The absence of walls also removed what had been a major factor influencing locational choices of various kinds that had been made in reference to the edges rather than the center of the city. The center of a city, an abstract geometric concept, even when anchored by a green, a city hall, or some other physical marker, conveys little sense of location compared, say, to an imposing stone gateway tower on the edge. In an unwalled city locational factors, beginning with distance and anything else that might be defined as an amenity, became all-important in determining value, access, and choice. This contrasts dramatically with walled cities, for within their walls, virtually all locations were good.

The lack of walls had a new impact on urban land value. In a walled city, or a city begun as one, land at the fringe, beyond the wall, had marginal value because it was beyond the scope of the city's direct protective power. The value provided by the city's economic, political, social, and military functions overwhelmed the value of its land as space. Within the walls economic transactions were secure, as were warehouses and personal property. Once inside the walls, land closer to the city center did not have inherently greater value for urban uses, nor did it preclude residential use. If we construct rent density gradients for two hypothetical cities, walled and unwalled (fig. 1), we can see that the walled city has a flat, sharply stepped curve compared to the concave decline in rents

away from the center of the unwalled city. But land outside the city walls lost its urban utility, and its value as pure space was modest, probably little more than agricultural or village land. One might liken the difference to that of owning an automobile in a place with roads and a place without.

Colonial American cities began with new, unpredictable, and considerably less visible constraints than their European and British predecessors. Because state and military apparatuses were not tied to any particular urban locale, city locations had changing economic values. In a place with mutable boundaries the center defines utility and value, for the center alone is permanent. But no one had ever conceived of urban land utility this way before. Therefore, New World cities began with a subtle but highly significant difference. They did not, and still do not, look like Old World cities: they were not so compact; land use was less mixed. This difference would not be conceptualized for at least two more centuries, continually frustrating the contemporary understanding of the new cities. Older cities that had started out in walled form could tear down the walls, but predominating patterns of land use and attitudes toward urban space had already been solidly established. Similarly, the practical city government control of space had been well established, so that change and expansion could build along conscious, rational, and preexisting principles. To begin de novo , in a world where one of the most important limits no longer obtained, was and continues to be a difficult chore. To write free verse in an age raised on the sonnet posed a challenge of incomprehensible dimensions.

Although Old World city walls contained and constrained, their massive physical presence also gave clear witness to the concept of the city. By contrast, the more confusing urban form is one where there are no edges, where abstract principles derived from transportation costs and "frictions," that is, invisible impediments due to fragmented land ownership and control, from time to the center, primarily determine utility and hence value. It is this form of the city which so perturbs Jane Jacobs. And the dominance of the American city center has had an impact on the way geographers and historians have defined city growth eras. For example, the most widely accepted periodization of American urban development has been made on the basis of transportation eras and the effects of transportation on city design and location.[35] From the seventeenth

Figure 1.

Hypothetical Land Rent Values for Walled and Unwalled Cities

century on, American urban dwellers constructed their cities with the knowledge that there was always more space on the edges, making caution and control irrational. The amount of space for an activity could be balanced rationally against travel time to the center, with access to other goods and services also entering the equation. Should the government decide to exercise a very costly control over locational or building decisions, one could always move farther away, if necessary beyond the political scope of the particular city. Even today, the American visitor to Britain or Europe cannot help but be struck by the comparative differences in the edges of cities. American cities have no sharp demarcation between them and the surrounding countryside, but exhibit instead a slow decrease in housing density, an increase in auto wrecking yards and other space consuming enterprises, and in land used neither for farming nor for purely urban purposes. European and British cities cease clearly, often abruptly, and agricultural land usage begins immediately. Although in the late twentieth century planning boards firmly retain and reinforce this sharp differentiation, it is as ancient as the city itself.

Ultimately, in the United States, the freedom from a city space

restricted by walls introduced a new tyranny, that of the center. Powerful though often invisible, the center added many new complexities and problems to cities. The center could move, for instance, as a peninsular city like Boston expanded asymmetrically. The buildings, streets, water supply, and sewers, if any, could become inadequate to the changing demands imposed on the center by growth at the periphery. The center would therefore often appear to be problematic: inner city decay became one of the prominent urban problems by the 1960s. And so the tyranny of the center has become masked in our century by its apparent status as the passive victim of changes beyond its control. This paradoxical nature of the unbounded city is most obvious in the "doughnut" cities of the 1970s and 1980s, with their all-but-abandoned city centers.

Nevertheless, the center remains a battered but still dominant tyrant in the twentieth century. We have come to accept its dominance as the one "natural" point in the city and to see the walls of the ancient city as artificially confining. That land utility and therefore value should decline as distance from the center increases has become an axiom of urban economics.[36] The center's dominance also meant that the edges of the city took on particular material characteristics analogous to this economic law. The cross-sectional profile of a nineteenth-century city looks like a tent, supported in the middle by the American invention, the skyscraper (usually dated to William Le Baron Jenney's 1885 Home Insurance Building in Chicago), in contrast to the boater hat shape of the medieval city. Only an expansionist development of peripheral land for low-density usage made much economic sense. The most picturesque suburban edges upwind of urban smoke went to high-cost, low-density housing, as wealthy residents could expect to have the time to commute to the center. Individual buffers of land around each house provided the best control over neighbors. For these reasons, suburbanization, mostly of the wealthy, began very early in the nineteenth century, even before horse-drawn street railways made commuting simple.

The Edge of Town

On the other, less desirable, edges of cities, noisome and polluting economic activities (slaughterhouses, for instance) and poor

people found space for small enclaves. Intentionally or not, all these activities on the edge of town existed beyond the control of the city government. In a new country, the simplicity of low-density, outward expansion preempted any rigorous physical planning. Some planning historians identify the cause of these planning failures as the primacy of private profit, a decline from "community enterprise."[37] But planning was almost universally derived from old patterns in Europe, which had been created under the tremendous constraints of preexisting property rights and physical structures like walls. In the colonies, grand schemes on paper were destined to fail, as these constraints simply did not exist. While American cities were to gain many very important advantages over their European predecessors, they began with this persistent, invisible, planning disadvantage that masqueraded as a natural freedom.

More important than the sheer presence of residences and economic activities beyond the city's political boundaries was their subtle, continuous, and pervasive pressure in helping urban activities to escape from any city control which became costly, inconvenient, or coercive. One could simply move beyond the reach of city government, while still benefiting from its nearby presence. This had been impossible in the walled city era, when all of a city's economic, military, and political attractions had been contained within its walls. Land beyond the city boundaries had a unique allure in the New World, offering proximity to the city's economic and locational advantages, but freedom from its obligations. Even rural New England towns, which retained a great deal of nominal power over the distribution of large tracts of agricultural land, saw their central power slip away because of this allure.[38] Free from the costly burdens of protection and control born by their predecessor city-states, American cities at the same time competed with their own very boundlessness to gain control over their internal shape and destiny. What American cities had that made them unique was the power to grow, to compete with one another as economic units.[39] U.S. cities lacked the political autonomy of ancient British cities on the one hand. Yet, on the other, they had more power than the new industrial cities of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain. Their circumstances have in this way been complex and consistent over the course of three and a half centuries, expansion and growth defining the appropriate model for a

city to follow. American cities could intentionally make themselves denser, bigger, richer, and taller, but they could not control their appearance.

Early nineteenth-century residential suburbs symbolized the attraction of the edge. Suburbs as elite residential locations are unique products of the modern era of unwalled cities.Through almost two centuries of colonial expansion, the elite had often chosen to live in the cities. But at the very moment that cities began to expand at the end of the eighteenth century, to take more than their traditional 5 percent of the population, those few who could afford to, began to move out, building themselves large rural estates.[40] Cities were a necessary evil to which the elite accommodated themselves: whenever their negative aspects began to over-shadow their positive aspects, those who could afford to withdrew to suburbs, retaining access to urban power but rejecting the cities themselves.

Colonial Urban Society

New England towns often escaped the complex fate of growth, expansion, and central decay. The social conditions and economic costs of their success are illuminating.[41] These compact towns, which are rewarding to visit in the late twentieth century, contain artful arrangements of square and meeting house, with residential housing casually but closely interspersed. Their abrupt separation from the fields beyond was recognized and commercially exploited as a planning and esthetic delight as early as the mid-nineteenth century.[42] Many towns made successful transitions from farming villages to wealthy suburban villages in this period, luring wealthy urban residents. Why didn't these towns suffer the fate of cities, expanding into the suburbs and letting their centers decay?

The classic New England town began in fact as a farming center. The primary factor of the farmers' production, arable land, ringed the town and provided the first economic impediment to residential expansion. Town statutes discouraged or forbade living away, so that farmers tended to live in the town and walk to their fields, which were often scattered rather than contiguous. Expansion of the town would have meant a longer distance to walk to the fields. Moreover, the fields were economically vital to the townspeople, so that unlike a city, the edge of town was not the

Astor's Suburban Home, New York, 1802.

While wealthy people lived near the center of early nineteenth-century

cities, the notion of a suburban dwelling had already become fashionable.

John Jacob Astor's home embodies the suburban virtues—near the country,

the land not used for productive agricultural purposes, yet also close to

the city's economic, political, and social attractions. By the middle of the

nineteenth century, this estate was venerable enough to be considered a

historic monument.

Source: Photo Library, Museum of the City of New York.

end of the townspeople's activities, but rather a continuation of them. Finally, the agricultural production that supported the town also limited its population. The town had to be relatively self-sufficient in food production, which meant in turn that its population could grow no larger than the fields allowed.

Several New England town studies have established that by the third generation of settlement, younger sons and daughters had to leave in order for their older siblings to retain enough land to survive. Population pressure grew to crisis proportions by the 1690s, and the idyllic stability of the town was achieved only at the cost of social repression, economic tension, and out-migration of sons and daughters. Town constables "warned out" transient paupers, community coming at the cost of conformity. The towns literally traded growth for stability. Today, when we visit these towns we marvel at their beauty, proportions, and tranquility, unable to imagine the family stress and severity required to produce such enduring stability. The departure of many brought community for few.[43]

As the seaport cities grew bigger they retained their differences from older European cities and from one another. Unlike the classic New England villages, they contained heterogeneous populations and were vulnerable to economic fluctuations. Wars precipitated social crises of varying dimensions in the three major colonial cities. Boston, for instance, particularly suffered from the loss of many men during King George's War (1744–1748), leaving for a time three married women to every seven widowed. Consequently, Boston's almshouse filled, while in Philadelphia only a handful of persons received relief in either the almshouse or in their own homes. In all the major colonial cities in the eighteenth century, population growth brought increased numbers of poor people. Philadelphia, Boston, and New York built almshouses for the destitute, rather than continue paying other poor people to board the sick and destitute.[44]

Within these port cities, elite groups established themselves and grew entrenched in their power, in parallel with an equally well-established and traditional laboring class. City governments attended to political and economic functions which mirrored, on a larger scale, those of village and town governments: regulating markets, selecting menders of fences, and passively operating within traditional categories.[45] These major cities served as im-

portant communications centers, their small but critical urban masses playing a major role in bringing on the Revolution. Throughout the late eighteenth century, the coastal cities provided the all-important sites of national governmental growth.

Even the minute, swampy, and crude city of early nineteenth-century Washington, D.C., provided a critical communications nexus.[46] The elected officials and tiny staff of the early federal government considered their tenure in the city temporary, and few took up permanent residence there. Instead they stayed in boardinghouses, and these boardinghouses quickly acquired importance because they provided a communications basis for government personnel, an otherwise disparate group from all over the country. Thus a city which on the surface served as little more than a camp began to exert a central power in the young republic.

Colonial Cities and the Economy

The most important urban development of the late eighteenth century, however, was not to be found in the role cities played in the political affairs of nation building. Rather, their crucial role was to be leaders in promoting and shaping economic growth. A seemingly minor aspect of the federal government's late eighteenth-century move to Washington provides a clue. In an attempt to drum up land sales in the rural District of Columbia and to encourage residential settlement as a more seemly alternative to the transitory habit of boarding, the government sponsored a land auction. In 1793 George Washington led a procession with two brass bands and Masons in full costume across the Tiber to a barbecue and land auction at which he purchased the first four lots of the new capital's undeveloped swampland.[47] Even this bit of sales promotion failed to spark the desired land sales in the District, which remained an uncouth, muddy, and sparsely populated embarrassment throughout most of the early nineteenth century. But self-promotion, boosterism, and a constant attention to the economic main chance soon came to characterize the young nation's cities.

Most eighteenth-century cities had made no attempts to promote themselves, for they saw themselves as regulatory entities, controlling access to urban privileges. They had "police" powers of control within their boundaries. Like princely rulers, they could watch over their inhabitants' economic as well as social behavior,

though cities in the Massachusetts Bay Colony tended to emphasize the social over the economic. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to become a full urban citizen, a "freeman of the city," was to ascend to privileged status. To practice most urban trades, in all the colonies but Massachusetts, one had to purchase freemanship, a fee that assured the city revenue and control over trades. (Massachusetts Bay Colony cities had to collect taxes to augment their lack of revenues from markets and fees.) Freemen also ran the city governments, making them resemble something like twentieth-century chambers of commerce. In Boston, so often an exception, the town meeting made decisions, thus basing the franchise on property ownership rather than freemanship.

Power and its ruling elites—religious, military, and economic—were essentially one; modern scholarship emphasizes the unitary nature of colonial elites, linked and intertwined by personal and family relationships. Michel Foucault's investigations of state power have evoked a notion of precapitalist princely power that commanded absolutely: the monarchy emphasized its power in confrontation with individuals. But modern bureaucratic power, he argues, has become a faceless, nameless, and pervasive presence, constantly defining and observing the individual's life course from birth to death.[48] Though artfully constructed, Foucault's dichotomy bears little descriptive resemblance to either the modern or the colonial city. Limited by the colonial governments, local governments never had the absolute power they might have wished for. Contemporary local government in the United States, while pervasive, has not sought to permeate the individual's life. Perhaps this has occurred on the state and national level, where most transitions in life are registered or regulated, from birth to marriage through retirement and death. But just as the city was never the locus of princely power in the United States, it is not now the locus of bureaucratic power. Thus Foucault's metaphor helps us think about the way confrontational power and bureaucratic power differ, more than it helps us describe the differing kinds of city. Moreover, his model helps us consider how colonial city governments essentially reacted to a defined range of events and situations. The nature of the reaction took the shape of state power confronting an individual's actions: for instance, a shop owner built out onto the public road, and the town officers ordered him to remove the building.

The significant exception to a reactive stance came in the market, where medieval traditions held sway into the nineteenth century. The market, the traditional center of the city for thousands of years, epitomized in a most literal way the political, economic, and social nature of a city. Historians consider the Greek citystate's agora representative of an aesthetic and political pinnacle of the urban market, for in the agora the city transacted its politics, created vital trade centers, and debated intellectual issues. The functions epitomized by the agora continued in European markets after the fall of Rome, through the Middle Ages, and arrived in North America with Western European colonization. Colonial city governments vigorously exercised their economic powers, setting prices and wages as only the federal government occasionally undertakes in the twentieth century. Except for Boston, they maintained and supervised the marketplaces, setting and enforcing standards of quality, for instance, as well as prices.

City governments literally owned their marketplaces. A physical locus, whether an open place or a building, had to exist for the city to regulate prices. The city minimally maintained the place, protected it if need be, and exerted complete control over trading privileges. It often extended its market control and ownership to other commercial facilities, such as docks and warehouses. The market brought agricultural produce to urban customers, it dispersed urban manufactures to rural customers, and it served as the central place of communication to a broad public. In it the city role of policing public behavior saw daily exercise, and in it the urban economies of scale and agglomeration worked at their most basic levels.[49] The market. although symbolizing the city's economic functions, was no longer a literal requirement for a rich and complex urban economy, but rather an ancient form within which to organize and regulate that economy. Marketless Boston, which mandated door-to-door trading, made this clear, though one wonders if the lack of the market did not in some ways work against economies of scale; one thing was clear—the lack of a market was highly inconvenient for both buyers and sellers.

Not only did the marketplace capture the city's ancient symbolic aspects but its careful regulation and its privileged and protected economic activities highlighted the politics of the trading economy. It was a simple and visible political economy. To be awarded the privilege of trading in the market, stall holders paid

the city fees. If they violated the rules of the market, sold underweight bread, for instance, they paid fines or lost their trading privilege. In 1686 the Albany Mayor's court confiscated a nonfreeman trader's wampum and deer skins, exacting a fine for trading in violation of the city's monopoly over both the participants and places approved for Indian trade. Philadelphia imprisoned a nonfreeman who set up as a butcher in 1718. New York explicitly made exceptions as an indirect means of providing welfare, for instance giving nonfree Widow Robinson in 1708 the privilege of following "any Lawful Trade or Employment within this Corporation for better Obtaining a livelihood for her and her family."[50]

The demise of city market regulation in favor of free trade began between 1800 and 1830. In an analysis of city statutes and ordinances, Jon C. Teaford has traced the replacement of the responsive city with what he calls the late eighteenth-century "expansion of municipal purpose." Until as late as 1821 New York City had set the price of bread, and not until 1829 did the first butcher break away from the city-mandated market sales stall and set up a private shop. These changes all involved state legislative and city battles over the inviolability of the city charters and, as with the expansion of the franchise, the city corporations gave up each element of their old regulatory power only with a struggle. Yet the same legislatures that took away the privileges of the old charters gave the cities a far greater power, the power to gain revenue from taxes.[51] Thus an apparent loss of power proved in the long run to be the creation of a new power.

Thus early American cities were pale imitations of those in the Old World. The premodern or colonial era selectively retained certain deep similarities and continuities with ancient cities from the time of their first emergence around 3000 B.C. Containing about 5 percent or less of a region's population, these cities functioned as commercial and political centers. By the time Europeans colonized America, Europe's cities were no longer city-states, for the nation-state had taken over their military and political functions; but European and British cities retained many of the formal assets and liabilities of their medieval predecessors. The new American urban network built rather slowly for about two hundred years, yet it did so with increasing independence from old forms. Whether they wanted to or not, the colonists could not replicate the cities

The Columbus, Ohio, Market, circa 1850.

Compare this structure with its medieval predecessor the Thaxted Guild

Hall. The ground floor can be opened to admit movement of goods, while

the upper rooms have diminished in size and functional importance, as

the city now has a separate building for governmental offices. But the

exaggerated scale introduced by the artist suggests a sense of size and

power similar to that conveyed by Thaxted's Guild Hall. Columbus erected

its first market building in 1814. It was so quickly and poorly constructed

that the town council declared it a nuisance after three years and ordered

another built. This picture shows yet another market, at least the city's third.

Source: from Jacob H. Studer, Columbus, Ohio, Its History,

Resources and Progress (Columbus: Jacob H. Studer, 1873), 45.

of the Old World. Explosive, crude, vigorous, and innovative in their failed imitations, by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century U.S. cities began to produce truly new urban environments.