6

The Food-Supply Dictatorship: A Rhetorical Analysis

A man forgot about nature in those days. Words thundered over the country, insistent summonses to struggle, impatient, exultant, accusing, threatening enemies. Millions clustered around these words as if they were magnetic poles. They were challenges to destroy and at the same time challenges to create. Those were days of sudden decisions and of constant agitation.

Konstantin Paustovsky, recalling spring 1918

In the period between May and July 1918 food-supply policy became one of the central political questions of the day and the subject of impassioned partisan clashes in the legislature of the soviet system, the Central Executive Committee. The debates occurred at the end of the brief period when the new soviet-based political authority was still a genuinely multiparty system. The food-supply decrees were not only a response to the food-supply Crisis but also an assertion of the viability of the Bolshevik vision. This assertion was not left unchallenged: the Bolsheviks had to defend the food-supply dictatorship in the new forums of the soviet system against those who remained loyal to other visions of the Russian revolution.

An understanding of the debates requires a close examination of the meaning of the key rhetorical terms employed by the contending parties. The attention given in this study to rhetoric should not imply that the contending parties were responding only to their own imaginary constructs. The severity of the crisis in food supply and the crisis of authority was no illusion; but a coherent collective response to circumstances is possible only after they have been given meaning by political leaders.[1] Rhetorical advocacy is needed to fit the response to any particular problem into the larger framework of a general political outlook. This task is especially important for a new political class whose claim to authority is based on a novel and untried political formula.

[1] Robert C. Tucker, Politics as Leadership Columbia, Mo., 1981), 49.

Divisions Among the Peasantry

Each of the parties had a different terminology to describe the peasantry, and each terminology implied not only a different way of dividing the peasants but different theories about relations among them. The debates of 1918 were conducted by socialist intellectuals with a long tradition of dispute on this question; they were alive to the nuances of terminology, and so should be the observer who wishes to understand them.

|

For the SRs, the center of attention was the laboring peasantry: groups above and below were residual and indeed not genuinely peasant. The laboring peasant was one who lived by applying his own labor to his own land; the kulak was one who did not live by his own labor but exploited others, either by hiring them or by using his strategic access to the cash economy (shopkeepers, usurers, and other middlemen). Similarly, the poor peasant was someone who was unable to live on his own land by his own labor. The poor-peasant group had no unity beyond this negative description since there were a wide range of reasons for someone's failure to succeed as a genuine peasant: he might make his living as a craftsman; he might be lazy or alcoholic; he might be suffering from a temporary poor harvest, or she might be a widow struggling on her own. Once land was equally distributed, members of this group would either become real peasants, leave the village altogether, or suffer the consequences of their refusal to work.[2]

This division of the peasantry was probably closest to the division made by the peasants themselves. The kulak, who (in the peasant's view) got rich not by honest labor but by manipulating the cash economy and duping his neighbors, was indeed the peasant's enemy. Since the kulak embodied the individualizing influence of the market (which affected both agricultural

[2] The clearest exposition of the Left SR view is V. Trutovskii, Kulaki, bednota i trudovoe krest'ianstvo (Moscow, 1918). The origins of the SR outlook are described in Maureen Perrie, The Agrarian Policy of the Russian Socialist-Revolutionary Party (Cambridge, 1976).

products and land), the SRs felt that he was subverting peasant solidarity. The SR definition of the kulak also reflected the abstractions of the socialist intellectual when it put the usurer on the same footing as any peasant who hired labor. It is my impression that a peasant who hired a number of workers but worked in the field himself was not regarded automatically as an enemy by other peasants. The peasant made his division not by the SRs' abstract concept of exploitation but by whether a person truly earned his living, which he could only really do by physical labor. It is also my impression that the SR division was already dated by 1918. The kulak of old—usurer, shopkeeper, grain dealer, or land speculator—was a transitional figure at a time when the village was making the painful move to integration within the market economy. As that integration proceeded and the peasantry as a whole became more attuned to the market with its dangers and opportunities, the kulak was less able to exploit a monopoly position or peasant ignorance, and he gradually developed into a normal and useful part of the village scene.[3] But compared to the social democratic analysis, the SR view may be a better place to start a sociology of the Russian village.

The social democrats—Bolsheviks and Mensheviks—gave their main attention not to the central group of peasants but to the groups below and above. It was these groups, they believed, that had reality and the central group that was residual. This view resulted from their absolute confidence that the peasantry was undergoing a process of class differentiation (rassloenie ) that would eventually end the existence of the peasantry as such and leave only a rural bourgeoisie and a rural proletariat. The "middle peasant" was simply someone who was not yet a member of these two groups.[4] The difference between the Menshevik and Bolshevik views consisted in a tactical question: to what extent could this process of differentiation be useful to the revolution? The Mensheviks tended to look on the middle peasant as a future member of the rural bourgeoisie and therefore wished to make no concessions to him for fear of strengthening the enemy;

[3] See the descriptions of the Russian village by Ernest Poole in "Dark People " and The Village: Russian Impressions (New York, 1918). For SR ambivalence about the kulak, see Perrie, Agrarian Policy , 74-85. See also Teodor Shanin, Russia as a "Developing Society" (London, 1985), 156-58; Manfred Hagen, Die Entfaltung politischer Offentlichkeit[Öffentlichkeit] in Russland 1906-1914 (Wiesbaden, 1982), 51-52.

[4] See Chantal de Crisenoy, Lenine[Lénine] face aux moujiks (Paris, 1978), and Kingston-Mann, Lenin and Peasant Revolution . De Crisenoy might be said to adopt a Left SR standpoint. She brings out one central point better than Kingston-Mann: Lenin felt the "rural poor" had socialist revolutionary potential only insofar as they were proletarians, not peasants. For a discussion of the debate over rassloenie, see Teodor Shanin, The Awkward Class: Political Sociology of the Peasantry in a Developing Society (Oxford, 1972).

they considered the rural proletariat too isolated in rural society to be of much use as an ally of the working class.

The Bolsheviks (that is, in this case, Lenin) postulated a double soul within the middle peasant: one yearning toward the delights of being a petty bourgeois and the other accepting the honorable and progressive status of proletarian. This double soul allowed the party to use the revolutionary energy of the peasants' fierce desire for land to destroy the tsarist regime without fear of strengthening an implacable enemy, for soon the middle peasant would see that mere possession of land could not give him the secure petty-bourgeois status he longed for. In the second stage of the revolution independent organization of the rural proletariat would provide a pole that would attract and strengthen the proletarian side of the middle peasant's soul.

Nonetheless, the Bolsheviks were intensely suspicious of the middle peasant. The Left SR V. Trutovskii made fun of the Bolsheviks by remarking accurately that "it is ridiculous to look around every minute at the laboring peasantry, [asking] as the Bolsheviks do, Won't they suddenly deceive us? Won't they suddenly follow the kulaks?" But while the Bolsheviks always worried about this, the Mensheviks had no doubts at all: they knew ahead of time that the middle peasant would follow the kulak.[5]

All of these clashing schemes are based on the assumption that class can be used to predict political behavior, even though each party had a different theory about the nature of those classes. But class interpretations—especially ones worked out a decade or so earlier—are not helpful in understanding behavior in a time of troubles. Party intellectuals saw the selfprotective reactions of localism as emanations of a class nature rather than understandable responses to a breakdown in social order. But the division between grain consumers and grain producers was more important in 1918 than the class divisions postulated by the intellectuals. There was no particular connection between those who happened to have access to grain in the spring of 1918 and any long-term class dynamics however interpreted. The debate over food-supply policy was therefore conducted in language that was not appropriate to the subject at hand.

The Bolshevik scheme may have been the least descriptively accurate of the three, but it was also the most useful as a basis for political action. The doctrine of the double soul (like many other Leninist concepts) allowed political flexibility while preserving the appearance of doctrinal consistency. The Bolshevik view was that the middle peasant wavered throughout the civil war as one side or another of his soul gained the upper hand

[5] Trutovskii, Kulaki , 13. For the Menshevik view, see Martov's remarks in the Central Executive Committee, 20 May 1918, 300-301.

until he was finally persuaded that Bolshevik firmness could be relied on. A more realistic view shows the peasant as remarkably persistent in protecting his own basic goals—which were not necessarily the ones attributed to him by socialist intellectuals—with whatever means were available. It would also show the Bolsheviks in an undignified flurry of retreats, compromises, and maneuverings culminating in the decriminalization of the grain trade in 1921. Still, the doctrine of the double soul allowed the Bolsheviks to maneuver.

In 1917 and 1918 the Bolshevik view of the peasantry went through substantial changes under the impact of the food-supply crisis and the partisan debates of the spring of 1918. Bolshevik rhetoric moved away from a bipolar model that emphasized the conflict between bourgeoisie and proletarian to a tripartite model that underlined the crucial importance of a large swing group within the peasantry. At the same time the claim that a revolutionary majority existed among the peasantry was quietly retracted as it became clear that the food-supply crisis could not be solved simply by expropriating a small minority. The Bolsheviks also took over a number of terms associated with the SRs and afterward discarded some (laboring peasantry ) and retained others (kulak ). A detailed examination of these changes will show how rhetoric can serve as a barometer of the pressures exerted on political activists.

Before 1917 kulak was used by Lenin in its classic strict sense of village middleman between the peasants and the larger cash economy. It was then a small subset of well-off peasants , one that was not of great interest for revolutionary strategy. Lenin saw the kulak as the exploiter of even the protobourgeois well-off peasant and assumed therefore that he would be disposed of in the first phase of the revolution, when the peasantry was still acting as a united group. (The association of the term kulak with the SRs probably made it even less attractive to Lenin.)[6]

The Bolsheviks adopted kulak in 1918 partly because the word had become more popular in 1917 in connection with the food-supply crisis. The kulak in his role as shopkeeper and small grain dealer was one of the "dark forces" who opposed the grain monopoly. As a grain speculator who brought up and hoarded grain, he was seen as both a cause of the shortage and a potential solution to it. Of course, this use of kulak by frightened and famished city dwellers was emotional and vague. The political coalition between Left SRs and Bolsheviks also influenced Bolshevik terminology. While this coalition was in effect (October 1917 to March 1918), the Bolsheviks adopted SR terminology in deference to their partners, who

[6] Lenin, PSS , 1:18, 227, 259; 2:426-27, 535-36; 7:158, 189.

were assumed to be the specialists in the peasant wing of the revolution. After the Left SRs quit the government, and as relations between the two parties degenerated into open conflict, the Bolsheviks used SR terminology to bait the Left SRs and to steal their thunder.

Kulak was the correlative term of laboring peasantry . The latter term implied the SR view of the revolutionary potential of the great majority of the peasantry, a view the Bolsheviks were pleased to make their own for a time. But the Bolsheviks differed with the Left SRs on the meaning of this revolutionary potential. For the Left SRs, it meant one could rely with confidence on the spontaneous action of local forces; for the Bolsheviks, it meant that the majority of the peasantry would accept the discipline of the central workers' and peasants' authority. The Bolsheviks' assertion that they believed in the revolutionary discipline of the vast majority also fit in with their assertion that they could alleviate the food-supply crisis by expropriating the large reserves of a tiny minority.

Since the Bolsheviks still wished to talk in terms of a clear class struggle in which a large majority was pitted against a small minority, it would have spoiled this picture to dwell on the existence of a large swing group among the peasantry. The evolution of Bolshevik rhetoric can therefore be traced by the attention given to the middle peasant. In Lenin's writings of 1917 the middle peasant is conspicuous by his absence, and all the attention is concentrated on the two poles of attraction at either end of the class spectrum. On the bourgeois side, Lenin's original term well-off peasant is replaced simply by rich peasant after April; the term kulak is used in 1917 rarely and almost always in connection with the price-doubling decree. (As late as April 1918 food-supply official D. P. Maliutin defined the kulachestvo as the private trade apparatus.)[7] On the proletarian side, the original term batrak (rural laborer) was felt to be insulting—this should have been a clue that something was wrong with the political dynamics of the model—and was dropped after April 1917 in favor of sel'skokhoziaistvennyi rabochii (agricultural worker).

The rest of the peasantry was seen as tending toward these two poles. For those closer to the proletarian side, a new term was coined: bedneishee krest'ianstvo , or "poorest peasantry." This term was criticized both by Left SRs and Mensheviks for vagueness, and it is hard to escape the conclusion

[7] Prod. i snab . (Kostroma), no. 2 (May 1918): 24-26. Kulak did not usually mean "well-off peasant" in 1917. Pershin notes that the proceedings of the Main Land Committee in 1917 reveal no mention of the kulak. Pershin, Agrarnaia revoliutsiia , 1:311. Uses of the word kulak in 1917 can be found in Ek. pol. , pt. 3, doc. 94, 228, 260, 262, 272, 274; Sukhanov, Zapiski , 3:196; Lenin, PSS, 34:184, 235.

that it was precisely this vagueness that commended it to the Bolsheviks. The poorest peasantry was defined mainly by its assumed willingness to accept proletarian political leadership. It included peasants who owned some land but not enough to avoid the necessity of hiring themselves out. In Lenin's eyes this characteristic made them not incomplete peasants but incomplete proletarians or "semiproletarians."

In 1917 Lenin implied that the peasant-as-such, the peasant owner (khoziain ), would follow the lead of the well-off peasants. One of the few explicit references to the middle peasant I have found in Lenin's 1917 writings refers to him as a little capitalist on the side of the well-off peasant. But in general the Bolsheviks downplayed the question of possible peasant allies of the well-off peasant, and the picture drawn in 1917 is of a sharp unambiguous clash between the majority of poor peasants and a minority of rich peasants.[8]

Lenin's emphasis on class conflict within the peasantry is accompanied by scorn toward the populist "laboring principle" that postulated the solidarity of the peasantry as a whole. It is thus a surprise to see laboring peasantry used as a synonym for the poorest peasantry soon after the October coup. But this terminological concession to his Left SR coalition partners did not mean that Lenin abandoned his two-part conflict model: the laboring peasantry simply stood in for the poorest peasantry for a while. The high point of Bolshevik acceptance of this vocabulary was in late May: in response to Left SR criticism, the Central Executive Committee employed laboring peasantry in a resolution (although Sverdlov still felt that poorest peasantry was "more exact"), and the Left SR term was also used in one of the food-supply dictatorship decrees. But under the pressure of events in the spring and summer of 1918 the differences between the two conceptions of the peasantry became more pronounced, and the referent of laboring peasantry in Bolshevik rhetoric slowly gravitated from the poorest peasantry to the middle peasantry and finally to the rich peasantry, at which point the Left SRs were accused of defending the kulaks.[9]

A term that became central to Lenin's rhetoric starting around April 1918 expressed the Bolshevik conception of the peasantry: melkoburzhuaznaia stikhiia , or "petty-bourgeois disorganizing spontaneity." To some extent this is simply a Marxist euphemism for backward peasantry. A Menshevik writer scornfully observed that Lenin avoided the very word peasant in his discussion of stikhiia .[10] This avoidance was probably of set

[8] Lenin, PSS , 31:21-22, 52, 64, 92, 113-15,136, 163-68, 188, 241,272,419; 32:44, 166, 184-86; 34:184, 235, 330, 400-401.

[9] Lenin, PSS , 35:64; 36:504; Ia. Sverdlov, Izbrannye proizvedeniia (Moscow, 1976), 181-84.

[10] Vpered , no. 71, 25 April 1918 (Martynov). Martoy called it the "new Leninist word." Vpered , no. 72, 26 April 1918.

design, for in the drafting of the decree of 13 May the word peasant is dropped from any accusatory formulation: "peasant predator" is changed to "village kulaks" and the phrase "not one pood will remain in the hands of the peasant" is softened to "in the hands of its holder." But the concept of disorganizing spontaneity meant that the kulaks were more to be feared than the Left SR outlook allowed, since they were not simply an unpopular minority facing a spontaneously revolutionary majority but also the most vivid expression of a disease to which the whole peasantry was susceptible.

The ranks of the revolutionary majority were being thinned at the same time by a new definition that eliminated anyone with a grain surplus. This definition helps answer the question, Who was the intended constituency of the Committees of the Poor? Were the middle peasants included from the outset? In various decrees and resolutions both poorest peasantry and laboring peasantry were used to indicate the constituency of the new committees. The Left SRs told the Bolsheviks that notwithstanding these formulations, the committees were obviously based on "your batraki " and represented Lenin's old strategy of organizing the agricultural wage laborer.[11]

Some Soviet historians maintain that on the contrary the Committees of the Poor were meant to include the middle peasant. They point to Lenin's correction of the decree setting up the committees: in place of the original definition of a poor peasant he substituted a more inclusive definition that left out only "notorious kulaks." This argument overlooks the fact that Lenin's definition also excluded anyone with a grain surplus.[12]

The Bolsheviks were indeed eager to cloud over the differences between the image of a revolutionary class struggle of the majority against the minority and the reality of enforcing the grain monopoly against much larger groups. Tsiurupa faced up to the terminological difficulty when he responded to a statement by a Left SR speaker that many peasants with surpluses could not be called kulaks: "What happens to these surpluses? Clearly they must be handed over to a state storehouse. Anyone who has surpluses and does not hand them over to a storehouse is subject to confiscation—to him will be applied the same measures that are applied to the kulaks. How can you fail to understand that anyone who has surpluses and hides them and is evasive is of course subject to pressure, no matter who he is."[13] This statement reveals that the kulak was not yet simply equated with the uncooperative possessor of a grain surplus—at least not

[11] Kamkov, Fifth Congress of Soviets, 74-77.

[12] Osipova, "Razvitie," 61; Mints, God 1918 , 387-88. Lenin's definition includes newcomers (prishel'tsy ), who were important for centralizing purposes and in many cases actually ran the Committees of the Poor.

[13] Central Executive Committee debates on the Committees of the Poor, 11 June 1918, 407-9.

in a debate that was relatively sophisticated. But it also shows a terminological gap for this uncooperative peasant, who lay somewhere between the categories of poorest peasantry and kulak.

Thus the original conception of the Committees of the Poor depended on a bipolar conflict model of the peasantry since the middle swing group had not yet achieved rhetorical prominence. The constituency of the Committees of the Poor was supposed to be as inclusive as possible, but only on the assumption that the majority of peasants was revolutionary in the Bolshevik sense—hence they would fight the disorganizing spontaneity of the petty-bourgeois kulaks and accept the organizational discipline of the center. In particular this assumption meant that they would hand over grain surpluses to the authorities. But it turned out that there was no such revolutionary majority. The Bolshevik leadership registered this fact by moving from a two-part conflict model to a three-part neutralization model. July 1918 marked the return to Bolshevik rhetoric of the middle peasant, who became the center of strategic attention.

The first appearance of the middle peasant was in response to the accusation of the Left SRs that the food-supply dictatorship was aimed (in practice if not in theory) against the broad mass of the peasantry. Maria Spiridonova, leader of the Left SRs, asserted in early July that the Committees of the Poor had alienated a peasant majority that otherwise consisted of natural supporters of a revolutionary regime: "[This legislation] strikes hard [bol'no b'et ] not at the kulak but . . . at the broad masses, the strata of the laboring peasantry."[14] The Bolsheviks were defensive on this point, and in their resolution on food supply they echoed Spiridonova by using the same expressive word, bol'no , but refused to admit that a naturally revolutionary laboring peasantry had been alienated. Instead they used a hybrid transitional term when they granted that certain unworthy worker detachments had indeed "hit hard [bol'no udariaet ] at the middle laboring peasantry," as well as at the kulaks, and that these abuses must be corrected.

In his speech following Spiridonova's, Lenin used the three-part model to retain the idea that the enemy was a small minority even while admitting that the majority was not automatically revolutionary:

A thousand times wrong is he who says (as do sometimes careless or thoughtless Left SRs) that this is a struggle with the peasantry. No, this is a struggle with an insignificant minority of village kulaks—this is a struggle to save socialism and distribute bread in Russia. . . .

It is untrue that this is a struggle with the peasants. Any-

[14] Fifth Congress of Soviets, 5 July 1918, 58-59.

one who says this is the greatest of criminals, and the greatest of misfortunes will happen to the person who lets himself [or herself] be hysterically carried away to the point of saying such things. No, we are not only not struggling with the poor peasants, we are also not struggling with the middle peasants. In all Russia middle peasants have [only] insignificant grain reserves.[15]

The speech goes on to paint an unconvincing portrait of the middle peasant as "our most loyal ally" who has the "sound instinct of a laboring person" and who will not only sell his grain at the official price but even admit the justice of having to pay higher prices than the poor peasant for industrial items.

Lenin's ambivalent view of the middle peasant is also shown by a statement at the end of July: "There is no longer a single village where a class struggle is not taking place between the poor population of the village, along with part of the middle peasantry that does not have any grain surpluses, that ate them up long ago, that does not participate in speculation—a class struggle between this overwhelming majority of the toilers and an insignificant handful of kulaks."[16] We are naturally led to ask, What happened to the other part of the middle peasantry? And does the middle peasant reject speculation only because he has nothing at present to speculate with?

In July 1918 a new wave of peasant revolts occurred at the same time as the prospect of a long, hard-fought civil war opened up. What Lenin later called the July crisis forced him to move the middle peasant to center stage. The so-called kulak revolts led him to admit that owing to peasant darkness "in many cases everybody [in the village] is united against us." The civil war meant that even more pressure would have to be put on the war-weary peasantry, yielding a new definition of the problem: "The kulaks know that the struggle is over the middle peasantry, for whoever obtains the support of this large section of the Russian peasantry wins." The key to success was thus no longer the enlistment of a revolutionary majority. Following from this new definition of the problem, the decision was made on 2 August to make "neutralization" of the peasantry the basis of food-supply policy, and shortly thereafter Lenin made the first public reference not just to avoidance of conflict but also to concessions to the middle peasant.[17]

Under the impact of the rhetorical evolution of 1917 and 1918 key

[15] Lenin, PSS , 36:507-11.

[16] Lenin, PSS , 37:11 (19 July 1918).

[17] Lenin, PSS , 36:504; 37:14; 36:532; 37:37.

Bolshevik terms for the peasantry took on new meaning. The term middle peasant of August 1918 was not the same as in Lenin's previous scenarios in which the middle peasantry would soon be attracted to one pole or the other on the class spectrum. Moreover, the food-supply crisis and the civil war forced the Bolsheviks to deal not with the peasant as protoproletarian but with the peasant as peasant. The attitude toward the peasantry often seen as originating after the civil war and in reaction to it should be seen as originating during the civil war and because of it.

When the decree on the Committees of the Poor appeared, poor peasants could still be taken to mean the vast majority of the peasantry. Only later, when it became clear that the peasant majority would never be eager supporters of Bolshevik food-supply policy, did the term shrink to include only those whom the Bolsheviks continued to regard as their natural allies and as semiproletarians, namely, landless and destitute peasants. Once this happened, class conflict in the village meant everybody against the poor, not everybody against the rich. As this balance of forces did not help foodsupply policy, the Committees of the Poor were abolished. These policy changes show that at no time did the Bolsheviks seriously try to realize Lenin's pre-October vision of a socialist transformation of the village based on independent organization of the rural proletarians and semiproletarians.

Kulak had now become the permanent name for the Bolsheviks' reprobate class. (The Calvinists divided up mankind much as the Bolsheviks divided up the peasantry: the reprobates, who are surely damned; the elect, who are surely saved; and the redeemed, who are caught in between.) The connotations of the term kulak by now contained many not entirely compatible elements: the SR image of a parasitic and exploitative minority roundly hated by the peasantry as a whole; the Bolshevik image of an economically progressive capitalist class that offered an attractive alternative political leadership to the village; the image created by the food-supply crisis of a ghoul who laughed at the groans of the starving and wanted to choke the revolution with the bony hand of hunger.

State capitalism and lass War

In Lenin's rhetoric the grain monopoly and the food-supply dictatorship were directly tied to the question of state capitalism. State capitalism in 1918 had little to do with what it came to mean after the New Economic Policy, or NEP, was introduced—namely, tolerance of market forms and other mixed-economy institutions.[18] Instead, the term before 1921 im-

[18] Laszlo Szamuely, First Models of the Socialist Economic System: Principles and Theories (Budapest, 1974), 58-59; L. D. Shirokorad, "Diskussii o goskapitalizme v perekhodnoi ekonomike," in Iz istorii politicheskoi ekonomii sotsializma v SSSR 20-30e gody (Leningrad, 1981).

plied organization of the national economy as a whole by the state. State capitalism was treated as a necessary historical stage in the prerevolutionary writings of both Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin. According to them, the internal laws of capitalist development were creating a movement away from the decentralized market toward state organization of the economy. This movement, accelerated by the demands of the war, was basically a progressive one, even though for the present the capitalists dominated the state and used its economic organization for their own ends. Lenin wrote in 1916:

When a large-scale enterprise becomes gigantic and systematically [planomerno ] organizes the delivery of primary raw material on the basis of an exact registration of mass data, providing two-thirds and three-fourths of demand for tens of millions of the population, [and] when distribution of these products to tens and hundreds of millions of consumers takes place according to a single plan (as does the American kerosene trust in both America and Germany)—then it becomes evident that what we have in front of us is socialized production, and not just "interlocking directorates."[19]

Even earlier Bukharin had discussed "state capitalism, or the inclusion of absolutely everything within the sphere of state regulation." He cited as an example the German food-supply dictatorship, under which "the anarchic commodity market is largely replaced by organized distribution of the product, the ultimate authority again being state power." Despite his eloquent denunciation of the militarized bourgeois state, he felt that the "material framework" of the state's organization of the economy could be used by the revolutionary proletariat.[20]

In 1917 this theory was easily fitted into the sabotage outlook: the otherwise inevitable progress toward all-embracing regulation of the economy was being thwarted by the frightened bourgeoisie. Lenin could use state capitalism as an argument for an armed uprising:

[19] Lenin, PSS , 27:425 (Imperialism ).

[20] N. I. Bukharin, Selected Writings on the State and the Transition to Socialism , ed. Richard Day (Armonk, N.Y., 1982), 16-17, 22-23, 32-33. See also Bukharin, Ekonomika perekhodnogo perioda (Moscow, 1920), 69-72; Bukharin and E. Preobrazhenskii, Azbuka kommunizma (Petrograd, 1920), 88-91. Lev Kritsman called the Supreme Economic Council the "proletarian inheritor of finance capital" (Geroicheskii period , 198). For a discussion of Bukharin's attitude toward the state, see Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution (New York, 1971), 31-32.

Well, what if, instead of a Junker-capitalist state, instead of a landowner-capitalist state, we tried to establish a revolutionary-democratic one that would destroy all privilege in a revolutionary way, fearlessly implementing the most complete democracy? You will see that state-monopoly capitalism under a genuinely revolutionary-democratic state will inevitably and unavoidably signify more than one step toward socialism! . . .

For socialism is nothing more than the very next step forward from state-monopoly capitalism. In other words: socialism is nothing other than state-monopoly capitalism that is made to serve the whole people and to that extent ceases to be a capitalist monopoly.[21]

In the spring of 1918, after the Brest-Litovsk treaty was signed, Lenin reverted to this theme, although he no longer used the term state capitalism . He argued that the new state authority now faced the "organizational task" of imposing "the most strict and universal registration and monitoring" and of creating "an extremely complicated and subtle network of new organizational relations, embracing the systematic [planomernoe ] production and distribution of products necessary for the existence of tens of millions of people."[22] Lenin had not abandoned the sabotage outlook, but the identity of the main saboteur had changed: "We must not forget that it is precisely here that the bourgeoisie—in particular the numerous petty and peasant bourgeoisie—will present us with the most serious struggle by undermining the monitoring we are establishing—for example, the grain monopoly." The postrevolutionary emergence of the peasant bourgeoisie as the main enemy of further progress toward socialism was consistent with Lenin's long-held views on the subject.[23]

Lenin thus seemed inclined to drop the term state capitalism , but it was reintroduced into Bolshevik rhetoric by the Left Communist opposition that had originally formed during the Bolshevik debate over the BrestLitovsk treaty. The Left Communists did not object to centralized economic organization in itself; their protests were primarily directed against the participation of capitalists in administration. They could not understand how the saboteurs of 1917 could be trusted with economic authority in 1918. They also objected to the "bureaucratic" nature of Lenin's centralizing policies, by which they seem to have meant hindrances to the participa-

[21] Lenin, PSS , 34:190-93. This whole passage is crucial. For other references to state capitalism in 1917, see 32:293-94; 34:160, 173, 310, 373-74.

[22] Lenin, PSS , 36:138, 171.

[23] Lenin, PSS , 36:182, 122, 131-32, 141.

tion of workers and the independence of local soviets. We can therefore assume that they were opposed to the food-supply dictatorship, even though they seem not to have proposed a food-supply policy of their own. The Left Communists remained loyal to the Bolsheviks' 1917 version of the enlistment solution—an unproblematic combination of state regulation and widespread participation, together with a great emphasis on capitalist sabotage.[24]

In response Lenin pugnaciously took up the term state capitalism and extolled its virtues, partly out of polemical verve. In his dispute with the Left Communists he quoted his own 1917 statements praising state capitalism, but he distorted his own earlier views by leaving this sentence out of his self-citation: "Socialism is nothing other than state-monopoly capitalism that is made to serve the whole people and to that extent ceases to be a capitalist monopoly." This statement concedes one of the Left Communists' central points, namely, a government monopoly used for the benefit of the people ceases by that very fact to be capitalist. But in his debate with the Left Communists Lenin wanted to drive home the similarities between state capitalism and socialism rather than the decisive political differences.[25]

Lenin could also use state capitalism to illustrate his new theme of the dangers of the peasant bourgeoisie. State capitalism was good because it was "something centralized, something allowing for calculation and monitoring, something socialized, and that is exactly what we lack, [for] we are threatened by the atmosphere [stikhiia ] of petty-bourgeois sloppiness."[26] The real enemy was not the "cultured capitalist," whose propensity for sabotage could easily be checked by the proletarian state authority and whose aid was necessary for economic regulation; it was the "uncultured capitalist," whose resistance to measures like the grain monopoly needed to be crushed "with methods of merciless violence."[27]

The term state capitalism soon became a liability for Lenin. It was serviceable enough in polemics within the Bolshevik party among sophisticated and like-minded socialist intellectuals but less effective in disputes between parties. Some of them, such as the Left SRs, began to act lefterthan-thou and say that the state-capitalist doctrine meant that the Bolshe-

[24] Lenin, PSS , 3d. ed. (Moscow, 1935), 22:569-71. On the Left Communist challenge, see R. V. Daniels, The Conscience of the Revolution: Communist Opposition in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, Mass., 1960), chap. 3.

[25] Lenin, PSS , 36:302-3; Bukharin, Ekonomika , 106-8; Leninskii sbornik 11 (1937): 369.

[26] Lenin, PSS , 36:255-56 (29 March 1918).

[27] Lenin, PSS , 36:305, 293-99.

viks were losing their revolutionary prowess. Others, such as the Mensheviks, began asking embarrassing questions about the justification of a soviet-based political authority and a socialist revolution if Russia was only at a state-capitalist stage. Worse, they began to contend that a capitalist stage implied such bourgeois democratic concepts as sharing power and imposing fewer restrictions on political opposition. Lenin dropped state capitalism and now began to argue that the "agonizing famine has moved us by force to a purely communist task."[28] But on closer inspection we find that this purely communist task is defined as the "correct distribution of bread and fuel, their intensified extraction, the strictest registering and monitoring of them on the part of the workers and on a general state scale."[29] The content of the terms organizational task, state capitalism , and purely communist task are thus all equivalent, given the different rhetorical contexts.

It is customary to describe Lenin's outlook in the spring of 1918 as moderate and as the forerunner to NEP.[30] Moderate is an odd description of a rhetoric whose key term seems to have been merciless: "We will be merciless to our enemies and just as merciless to all wavering and harmful elements from our own midst who dare to bring disorganization to our difficult creative work of constructing a new life for the working people."[31] Neither would Lenin's "organizational task" have seemed moderate to the "uncultured capitalists" whose lives he intended to transform—and since Lenin saw lack of cooperation as sabotage, he was prepared to use violence. When in early May he summed up the basic idea of the food-supply dictatorship as "merciless and terroristic struggle and war with the peasant bourgeoisie and [any] other that retains grain surpluses," he once again showed the intrinsic connection in his thinking between class war and the task of imposing registration and monitoring.[32]

The Partisan Challenge

The Bolsheviks' rhetorical presentation of the food-supply crisis cannot be separated from the partisan challenge from the other socialist parties in the spring of 1918.[33] After the signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty,

[28] Lenin, PSS , 36:405.

[29] Lenin, PSS , 36:362.

[30] In Western writings this tradition goes back at least to Maurice Dobb, Russian Economic Development Since the Revolution (New York, 1928).

[31] Lenin, PSS , 36:235-36. See also 35:311-13 (January 1918).

[32] Lenin, PSS , 36:316 (first published in 1931).

[33] For a study of the partisan conflict in this period, see Vladimir Brovkin, The Mensheviks After October: Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dictatorship (Ithaca, 1987), esp. chap. 3.

that challenge concentrated its fire on the food-supply crisis. In March and April the Bolsheviks had been inclined to be self-critical and stress the problems arising from indiscipline on the part of their own constituency. But this stopped when Mensheviks in the Central Executive Committee debates began to use these Bolshevik statements as proof of the Bolsheviks' complete helplessness before the food-supply crisis. The Bolsheviks also became more defensive as the food-supply crisis began to chip away at their central base of support, the urban soviets. The interaction between partisan considerations and food-supply matters was intensified by the fact that two of the obstacles to centralized unification of the food-supply apparatus—the regional food-supply committees and the village soviets—were political strongholds of the Mensheviks and Left SRs respectively. Thus the Bolsheviks needed a rhetorical definition of the food-supply crisis that shifted blame away from themselves and as much as possible onto the shoulders of the other parties; accounted for the wavering and defections in the Bolshevik constituency; and promised a short-term solution to the crisis that would provide outlets for hungry workers other than sackmanism, speculation, and political protest.

These needs were met by the class-war definition of the food-supply crisis, which ran as follows. The Bolsheviks were not to blame for the foodsupply crisis. Rather, it was caused by the bourgeois war and was being further intensified by kulak hostility to the revolution. The only reasons anyone would be reluctant to hand over his grain was speculative greed and a desire to choke the revolution with the bony hand of hunger. The socialist parties who weakened soviet authority by criticizing the grain monopoly were objectively part of the counterrevolutionary front that also included foreign and Russian capitalists and the petty-bourgeois kulaks. Some workers indeed had lost their revolutionary good sense because of the famine and because of the infection from the old system's rotting corpse. But the truly conscious workers would continue to rally round the Bolsheviks and in particular join the worker detachments that would serve the revolution by confiscating the grain of the kulaks. Such action was not an attack on the village but participation in a class war within the village. The creation of the Committees of the Poor as the lowest rung of the centralized apparatus of the People's Commissariat of Food Supply represented not bureaucratism and old-regime police methods but the armed people.

These themes appear again and again in speeches by Lenin, Trotsky, Grigorii Zinoviev, Iakov Sverdlov, and others in the spring of 1918. (Not all the Bolshevik leaders agreed with the analysis of Lenin and Tsiurupa; Aleksei Rykov and Lev Kamenev in particular advocated a softer line.) A few citations will give the flavor of them. In late May Lenin offered an incisive one-sentence analysis of the food-supply crisis: "The famine does

not come from the fact that there is no grain in Russia, but from the fact that the bourgeois and all rich people are making a last decisive battle against the rule of the toilers, the workers' state, the soviet political authority."[34] Zinoviev, always the most straightforward and crude of the Bolshevik orators, elaborated further on the problems of bourgeois sabotage: "There is no doubt that this is a definite plan, worked out in the quiet of bourgeois offices a long time ago." And this, he continued, should not be news to anyone, for recall what Riabushinskii had said: "Gentlemen workers and sailors, you think to wear us out with bayonets and your majority, but remember, we have a way of controlling you: the bony hand of hunger, and it will smother your revolution." Zinoviev's speech is littered with references to "Riabushinskii's agents" and "Riabushinskii's program"—for example, in speaking of the necessity of "holy violence on those kulaks who fulfilled Riabushinskii's program." More important were the references to Riabushinskii's parties —that is to say, the SRs and Mensheviks, who opposed such holy violence.[35]

Bolshevik rhetoric on the food-supply crisis took place in a growing atmosphere of invective and threats against the other socialist parties. The tone can be sensed in Lenin's reaction to Right SR and Menshevik criticism of Bolshevik implementation of the grain monopoly: the only distinction between them and the openly capitalist Kadets is that the Kadets were straightforward Black Hundreds.[36] According to Lenin, the conclusion was obvious: only fools could dream of any kind of united front of all soviet parties.

But the Bolsheviks did not content themselves with rejecting the possibility of sharing power. They moved on to open threats against the other parties—threats that were soon carried out. In a speech in early June Trotsky warned that unless the parties stopped making trouble on the foodsupply issue, a terror would be unleashed against them. Up until then terror had been avoided, but "now the soviet political authority will act more decisively and radically. . . . Don't poison the worker masses with lies and slander, for this whole game might end in a way that is to the highest degree tragic." In another speech, after the inevitable reference to

[34] Lenin, PSS , 36:357 (O golode , 22 May 1918). The words last decisive battle are in Russian a clear allusion to the apocalyptic vision of the Internationale.

[35] G. Zinoviev, Khleb, mir i partiia (Petrograd, 1918), 22-30 (speech of 29 May in Petrograd). According to Trotsky, the kulaks were the "advance detachment of the counterrevolution . . . the support and hope of the counterrevolution." Lev Trotsky, Kak vooruzhalis' revoliutsiia (Moscow, 1923-25), 1:81-83, (speech of 9 June 1918) (hereafter cited as KVR ).

[36] Lenin, PSS , 36:402 (speech of 4 June 1918). I regard this statement as a masterpiece of invective even for Lenin.

Riabushinskii, Trotsky asked if there was any line that divided counterrevolutionaries, monarchists, exploiters, and kulaks from the Right SRs and Mensheviks. "No, there is no such line: they are united in one black camp of counterrevolutionaries against the exhausted worker and peasant masses." He then went on to wonder at the patience of the Moscow workers, who allowed, in what was supposed to be a workers' soviet, five to ten Right SR representatives.[37]

In this way the food-supply crisis, caused by a Riabushinskian conspiracy that included the other socialist parties, justified the repression of all political opposition. Class-war rhetoric also transferred any faults of the workers to the other classes. Thus Lenin explained away the cases where worker detachments got drunk and looted the peasants by stating that "when the old society perishes, you can't nail up its corpse in a coffin and bury it. It disintegrates in our midst; this corpse rots and infects us."[38] If the workers showed their dissatisfaction with Bolshevik performance on food supply by going out on strikes, Zinoviev could argue that "it could not be otherwise: in our petty-bourgeois country there would be groups that decide that the revolution means 'give, give, give' and to whom the revolution means two pounds of bread, complete provisionment, and so on." Zinoviev combined his condemnation of petty-bourgeois influence with a certain flattery of the conscious worker who was free from these influences and should be able to rise above desperate women workers and the average member of the mass (srednyi massovik ) and see the deeper causes of the food-supply crisis.[39]

The Bolshevik rhetoricians saw the food-supply dictatorship as an excellent example of the organizational task that the revolutionary movement had to solve, whether that task was called state capitalism or a specifically communist task. As Lenin said:

Our revolution has now come straight up against the task of implementing socialism in a concrete practical way—and in this lies its inestimable service. It is precisely now, and particularly in relation to the most important question—the question of bread—that the necessity [of these things becomes] clearer than clear: an iron revolutionary political authority; the dictatorship of the proletariat; the organization of the collection, transport, and distribution of products on a

[37] Trotsky, KVR , 1:68-72 (speech of 4 June 1918), 90-91 (speech of 9 June 1918). The Bolsheviks' attitude toward the Left SRs was more lenient: they were generally seen as sincere but stupid.

[38] Lenin, PSS , 36:409 (speech of 4 June 1918).

[39] Zinoviev, Khleb, mir i partiia , 12-13, 18-20 (speech of 18 May 1918).

mass, national scale with a registration of the consumption needs of tens and hundreds of millions of people and with a calculation of the condition and results of production for this year and for many years ahead.[40]

The class-war definition of the food-supply crisis not only gave the "conscious workers" and other supporters of the soviet authority a visible enemy in the form of kulak saboteurs; it also gave the central authority a rod of discipline to apply to these same supporters since indiscipline in time of war is unforgivable. Thus Lenin, in the same paragraph as that of the passage just quoted, used the necessity of a grain monopoly to refute those who did not see the necessity of a state power in the transition from capitalism to communism—a state power that would be mercilessly severe not only to the bourgeoisie but also (perhaps more important) to all the "disorganizers of authority."

All these themes were combined in an appeal issued by the Council of People's Commissars on 29 May. After noting how the bourgeoisie was trying to use the famine to enslave the workers even further, the appeal went on to explain that the grain monopoly was needed to resolve the crisis. And if the monopoly was necessary, a further conclusion was inescapable: "Only the state in the person of the central authority can cope with this most difficult task." And the state could only do its job if independent purchases were not allowed, for this would merely represent one group of starving people tearing food away from another. "Sensible centralization" required discipline: "The grain monopoly will give positive results only when all directions coming from the center are unquestioningly fulfilled in the localities [and] when local organs of the authority carry out, not an independent food-supply policy, but the policy of the central authority in the interests of the whole starving population."

By way of compensation for this renunciation of independent purchases, the appeal opened the possibility of actively joining in a crusade against the kulak:

The kulaks do not want to give grain to the starving, and will not give any, no matter what concessions are made by the state.

Grain must be taken from the kulaks by force.

There must be a crusade against the village bourgeoisie. . . .

Merciless war against the kulaks!

In this slogan—salvation from starvation in the immediate

[40] Lenin, PSS , 36:358-59 (O golode , 22 May 1918).

future; in this slogan—salvation and deepening of the conquests of the revolution![41]

The worker detachments were also seen as a means of building a new state organization. Lenin called on the "advanced worker" in the foodsupply detachments to be a "leader of the poor, chief (vozhd ') of the village laboring masses, builder of the state of labor."[42] Trotsky exhorted the workers to emulate Western superiority in organization. Although all belligerents had been devastated by the war and were low on grain supplies, the Western countries had avoided famine by weighing available supplies to the last ounce and distributing them according to the directives of the state authority. As for Russia, "there is grain in the country, but to our shame, the working class and the village poor have not yet learned the art of administering state life."[43]

This perspective was a wider reflection of the food-supply officials' goal of using the worker detachments as a means of disciplining the food-supply apparatus. In a similar way the food-supply officials' professional view of the Committees of the Poor as a continuing base for the food-supply apparatus was generalized by the Bolshevik leaders, who saw the committees, potentially at least, as "secure cadres of conscious communists."[44]

The Committees of the Poor were an attempt to bypass or discipline the peasant village soviets, and class-war rhetoric performed its greatest service for the Bolsheviks in justifying this embarrassing attack on "soviet sovereignty." In practice the Bolsheviks were conceding the validity of the criticism of the whole idea of a soviet-based political order, namely, that local soviets were an entirely inadequate base for a centralizing "firm authority." By labeling the peasant soviets as kulak soviets, they could picture a retreat as a forward movement. A centralizing bureaucrat like Tsiurupa was happy to use revolutionary phrases about civil war to accomplish his own pressing purposes. In response to Left SR criticism of the attack on the local soviets, Tsiurupa said he would be happy to rely on the soviets, but "if the soviets call congresses that remove the grain monopoly and the fixed prices—if they refuse to carry out the state plan in the name of purely local interests—if they gather up grain in their own hands and continue to hold this grain in their hands—then it is clear that we must fight with such soviets, [and] we will struggle with such congresses right

[41] Dekrety , 2: 348-54.

[42] Lenin, PSS , 36:363 (22 May 1918).

[43] Trotsky, KVR , 1:76-77 (speech of 9 June 1918).

[44] Sverdlov, Izbrannye proizvedeniia , 181-84 (Central Executive Committee speech of 20 May 1918). This speech was given prior to the legislation on the Committees of the Poor, but its theme was the need for splitting the village.

up to imprisonment and the sending of troops, to the final and extreme forms of civil war."[45]

Class-war rhetoric also covered up a profound suspicion of the political tendencies of the poor peasants and a fear that the kulaks could provide an alternative leadership for the peasants. Food Supply Commissariat official Aleksei Sviderskii justified the "material incentives" given to peasant informers in these terms:

The village poor, not understanding their own interests or the existing situation, and in general very often not realizing what is really happening, very often act at the behest of the kulaks. They help and defend the kulaks so that no grain is taken, since [otherwise] they themselves will have no bread. The kulaks seek to use this; they start selling grain at a low price in an attempt to give the poor peasant an interest in having grain surpluses remain with the kulaks.[46]

So it seems that the only thing worse than a kulak selling at high prices is a kulak selling at low prices. The same analysis is given in more general terms in Sverdlov's speech: the reason, says Sverdlov, that we must hasten to split the village and integrate the peasants into our own organization is that otherwise the kulaks will get there first and unite the village against us. Perhaps because Sverdlov, an urban party organizer, was further removed from village realities than the food-supply officials, the incongruity in his speech between two images of the poor peasants is so pronounced as to be comic in effect. On the one hand, they were disciplined fighters for the revolution and worthy brothers in arms of the urban workers; on the other hand, they had to be kept by force of arms from turning into a drunken mob.[47]

Bolshevik class-war rhetoric was ultimately based on the essentially political nature of the Leninist terms for the peasantry: the peasants were divided according to their attitude toward the revolution and toward those who spoke in its name. It is inexact to say that these terms were politicized: they had never been anything but political. Their sociological content simply offered clues on where to look for friends or enemies. The kulaks could almost be defined as the natural organizers of village solidarity against the outside world, and as the above citations show, the Bolsheviks not only accepted this view but made it the basis of their policy toward the village.

[45] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyo , 9 May 1918, 259-61.

[46] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyo , 11 June 1918, 406-7.

[47] Sverdlov, Izbrannye proizvedeniia , 181-84.

If there is one term that sums up the interconnection between the themes I have been discussing, it is registration . Starting as a technical term, registration came to symbolize many of the hopes of the Bolshevik movement, and it was a constant refrain in Bolshevik rhetoric in 1918. It was first of all an integral part of the grain monopoly: enforcing the obligation to sell to the state all surpluses required accurate knowledge of each person's supplies. Moreover, the loss of the Ukraine and the deepening food-supply crisis made "clearer than clear" the need for "the strictest possible registration." But registration also linked the grain crisis to the general state-capitalist task of a centralized organization of the economy since the content of state capitalism could be briefly summarized as "registration and monitoring." This formulation also showed why statecapitalist organization was the threshold of socialism: a proper registration of available supplies was needed for truly socialist distribution. Not only grain was to be put on register; industrial items were also to be mobilized in this way and made available for commodity exchange, and this required more centralization of control over these items. In addition, registration pointed toward the class struggle since the kulaks and other disorganizers were hostile to registration and likely to sabotage it. The main purpose of splitting the village was to gain "alert eyes" for registration: the class war was primarily a war for information.

Critique of the Food-Supply Dictatorship

The rhetoric used by the Bolsheviks to present and justify the foodsupply dictatorship reflected their whole view of the revolution. The same can be said of the critique of the Bolshevik program put forth by the Left SRs and the Mensheviks, who constituted the loyal soviet opposition at this point and were still able to present their case in the Central Executive Committee. These two opposition parties were themselves deeply opposed in outlook, and it is probably true that each of them had more in common with the Bolsheviks than they had with each other. But their critique of the food-supply dictatorship had one point in common: they both lashed out at the Bolsheviks' primitivism and propensity to solve complex problems by means of crude force and heavy-handed centralization. The two parties had very different ideas about where the important complexities lay, and each defended the claims of their own specialists to be able to handle these complexities. The Left SR specialists were members of the SR-dominated village soviets, whom the Left SRs regarded as experts in peasant class relations, whereas the Menshevik specialists were economists and foodsupply experts like Groman.

The essence of the Left SR position was the defense of the independence of the village soviets, the latest incarnation of the village solidarity that the populist tradition had always celebrated. The Left SRs felt that the kulaks were an isolated and hated minority and hardly likely to dominate free soviets. The majority of the peasants—the "laboring peasantry"—genuinely supported worker-peasant sovereignty, and it was a mistake to stifle their initiative by imitating tsarist bureaucratism or, even worse, to antagonize them by sending out requisition squads. The proper course was rather to carry out energetically the laws on land equalization and to rely on the "state sense" of the local democratically elected authorities. Let policy be determined at the center, the Left SRs argued, but let it be carried out in a decentralized manner.

What particularly pained the Left SRs was the Bolsheviks' irresponsible use of the SRs' two-part division of the peasantry. The SRs used the model to emphasize the unity of the majority of the peasantry; the Bolsheviks temporarily adopted it to stress the sharpness of the split within the peasantry (without the fuzziness created by the assumption of a large swing group in the middle) and thus to stress the necessity and expediency of resorting to splitting tactics and the use of force. But the Bolsheviks were hardly likely to apply force constructively, said the Left SRs, as long as they relied on such a vague and inaccurate understanding of the kulak as they displayed in the Central Executive Committee debates. Obviously not everyone with a marketable surplus was a kulak: only those totally ignorant of the village would so believe. Who was or was not a kulak was a question to be decided by knowledgeable experts, namely, the local soviets, who would decide "on the basis of a whole range of complicated and delicate considerations" of which only locals could be aware. But the Bolsheviks proposed to send detachments composed of the dregs of the working class, people whose hunger had overcome their sense of honor to such an extent that they were ready to attack the laboring population of the villages.[48] Of course force should be applied against the real kulaks, acknowledged the Left SRs, but to do that in a crude and ignorant way would surely lead to a general throat cutting and discredit the revolutionary authority.

The Left SRs asserted that if the Bolsheviks were absolutely determined to split the village along class lines, they should do it in a respectable way and divide the classes by means of production (land and equipment), not by means of consumption (grain surpluses). As a result of Bolshevik bungling and paranoia about kulak influence on the peasantry, the exact opposite of

[48] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 9 May 1918, 254-56 (Karelin).

what they intended would be achieved: the otherwise isolated kulaks would get a new lease on life as the village formed a united front against what would be perceived as a marauding band from the cities. As the Left SR B. V. Kamkov summed it up: "Out of all the ways to fight with the famine, [the Bolshevik food-supply dictatorship] is the least likely to achieve its aim. . . . You do not know the village and you do not know how to fight the kulaks and as a result you are supporting them."[49]

Beyond these tactical arguments, the Left SRs had a deeper objection to what they regarded as Bolshevik dogmatism. They felt that the Bolshevik class-war rhetoric betrayed a willingness to shove alien urban schemes down the throats of the villagers. The Left SR V. A. Karelin interpreted the Bolshevik slogan class war in the villages to mean "up against the wall, I'm applying the principle of class struggle to you."[50] And Spiridonova parodied Bolshevik determination to clothe their emergency measures in revolutionary rhetoric: "Comrade Bolshevik-peasants, take these thick books of the Marxists and you will understand why punitive expeditions are being sent out." At bottom was the vindication of the peasants' right to full political and cultural equality with the urban workers: "We declare that the peasantry also has an independent way of life and a right to a historical future."[51]

The Mensheviks did not share the Left SR enthusiasm for the local soviets and wondered why the Left SRs could not see the necessity of preserving the "ties that united the different parts of Russia into one integral organism."[52] Although accepting the Bolshevik goal of centralization and organization, the Mensheviks felt that the Bolsheviks were entirely incapable of achieving it because of their political methods. The heart of the Menshevik critique was the assertion that Bolshevik exclusiveness and demagoguery on the political level made effective economic organization impossible. The Bolsheviks rejected a broad socialist coalition, harassed the opposition press, restricted the electorate, and in general resorted to "civil-war methods." At the same time they proclaimed "all sovereignty to the soviets," a policy that had the predictable result of destroying the ability of the center to carry out effective policy. And in their desperate attempt to save the situation, the Bolsheviks continued to refuse to share power; hence recentralization led to heavy-handed and ineffective bureaucratism.

[49] Fifth Congress of Soviets, 5 July 1918, 74-77.

[50] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 9 May 1918, 262.

[51] Fifth Congress of Soviets, 5 July 1918, 58-59. "Independent way of life" is a desperate paraphrase of zhizneustoichivo .

[52] Central Executive Committee, 9 May 1918, 256-58 (Dan).

Certainly localism was a problem, but the Bolshevik diagnosis of that problem as stemming from kulak influence was simply mythology. Any democratically elected local government would show the same localist tendencies, said Iulii Martov, and there was only one weapon against them: "independent and free deliberation, and most important, the independent manifestation of public opinion." Unwilling to countenance this openness, the Bolsheviks overreacted to localism: "Without enlistment of the broad masses [that is, without universal suffrage], you will be tossed like a squirrel in a treadmill between ultra-anarchist ideas and a bureaucratism that sounds like a sour joke in the ear of the workers to whom you promised to give 'all sovereignty to the soviets.'"[53]

One political advantage of the Mensheviks was that their specialists in food supply and other economic areas were clearly a more prestigious group than the Bolsheviks could produce—indeed in 1917 the Bolsheviks had simply taken over the program of Groman and his followers. The Mensheviks tried to press their advantage by stressing the technical incompetence of the Bolsheviks: what good was centralization if the Bolsheviks did not have the bureaucratic wherewithal to make use of the opportunity? "Why your bureaucrats [chinovniki ] should be more skillful and intelligent than the old ones, we do not know: practice has shown that they are much more venal, more dishonorable, and more corrupt than the old bureaucrats." (The speaker here, Rafael Abramovich, was called to order at this point by Sverdlov.)[54]

The Bolshevik response was to extol the virtues of the "modest workers [rabotniki ]" who were "pushed forward [vydvinutye ] by the masses." Lenin admitted that "the workers begin to learn slowly and of course with mistakes—but it is one thing to spout phrases and another to see how gradually, month after month, the worker [rabochii ] grows into his role, starts to lose his timidity, and feels himself the ruler."[55] A remark made by N. Orlov about the first food-supply congress in January expresses the underlying clash of attitudes:

One of the authoritative food-supply officials [Groman?] attached to the group that walked out of the Congress announced in a session of the socialist group of employees of the old Ministry of Food Supply that members of the Congress

[53] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 27 May 1918, 328-30 (Martov).

[54] Central Executive Committee, 4th sozyv , 27 May 1918, 330-32. Abramovich's attack was even more embarrassing because he quoted an intra-Bolshevik party circular confirming his analysis.

[55] Shlikhter, Third Congress of Soviets, 15 January 1918, 71-72. Lenin, PSS , 36:515, 5 July 1918.

"were people who sincerely despised all knowledge and hated all bearers of knowledge." In that heated time, it was difficult to expect an objective appraisal from people, especially from those who had chosen the enviable part of "sincerely not understanding" any creative outburst and who were deeply contemptuous of people striving to realize their desires in reality.[56]

The Mensheviks felt that energetic ignorance was no substitute for competent experts responsive to informed public opinion. The Bolsheviks were returning to an illusion of tsarism when they relied on giving wide power to commissars—a sort of food-supply governor-general—and sending them out as troubleshooters, acting in defiance of economic laws and the need for careful coordination.[57] Given their reliance on these methods, the Bolsheviks were incapable of actually carrying out the grain monopoly. Although the Mensheviks were even more closely associated than the Bolsheviks with the monopoly and the need for extensive economic organization, they reluctantly concluded that a paper monopoly was worse than none at all: why prohibit the people from providing for themselves if the government is incapable of providing them with the food they need? The Mensheviks therefore advocated certain concessions in regard to prices and the right of independent purchase; the Bolsheviks seized on these and called the concessions a capitulation to the capitalists and the kulaks.

Just as Bolshevik political methods made economic recovery impossible, Bolshevik economic methods made further political degradation inevitable. In particular, the accelerating inflation provided an economic analogue to the disintegration of central authority. Semyon A. Falkner, one of Groman's group, argued that the inflation created an irresistible economic pressure to break the increasingly unrealistic prices fixed by the state and that this pressure realized itself in the sackmen:

True, the fixed price usually entails a personal responsibility for breaking it, established by penal sanction in the law. But the realization of these threats requires a powerful state organization that penetrates into all cells of the social organism, [It must be] powerful not only from the physical volume of forces and means at its disposal but from the psychological training and unbribability of its agents.

But it is in the epoch of revolution and the reconstruction of the state mechanism that these forces are weakened and the

[56] Orlov, Rabota , 38.

[57] Central Executive Committee, 9 May 1918, 256-58 (Dan).

threats merely hang in the air, only haphazardly striking down this or that chance victim.[58]

This description of a coercive apparatus that is both all-embracing and ineffective does seem to apply to the Cheka, which never succeeded in damming the pressures leading to a speculative black market.

A brief mention should be given to critiques advanced by the Right SRs and the Kadets. Only one Right SR put in an appearance during the Central Executive Committee debates on the food-supply dictatorship. This speaker, Disler, boldly accused the Bolsheviks of creating the famine—through the inflation that they had intensified in a desperate attempt to stay in power, through the Brest-Litovsk peace, which deprived Russia of grain areas, through the civil war provoked by Bolshevik methods (the Czech troops in Siberia had just revolted), and finally through the proposed foodsupply dictatorship: "These armed detachments will be able to alleviate your thirst for blood, but not the hunger of the population." At this point, as can well be imagined, Disler was deprived of the floor.[59]

I take the Kadet critique from a pamphlet written in England in early 1919 by the emigre[émigré] Ariadna Tyrkova-Williams. She viewed the Provisional Government's original grain monopoly as a painful wartime necessity, one that later turned out to be a mistake since it was clearly beyond the capacity of the government machinery. The Bolsheviks retained it even after the peace treaty for ideological reasons, although they rejected most other Provisional Government reforms. Tyrkova-Williams also attacked the harassment of the sackmen train passengers by the lawless blockade detachments. (None of the socialist parties raised this point in the spring Central Executive Committee debates, although it had been going on since January.) Similarly, Tyrkova-Williams did not condemn the Committees of the Poor because they distorted the class struggle: rejecting the idea of class struggle altogether, she maintained that the Committees of the Poor were making orderly life impossible by introducing violence into village affairs and giving an opportunity to the village rabble to settle accounts: "Vio-

[58] Trudy pervogo s"ezda , 31 May 1918, 395-404. To combat inflation and the incoherent system of fixed prices, the Gromanites brought up their old program of an economic regulatory council (to be called the Price Center) on which the various economic interests would be represented so that an "equilibrium" would be established.

[59] Central Executive Committee, 4 June 1918, 386-87. This was a joint meeting with the Moscow Soviet and worker groups. The next speaker was Trotsky, who erupted with rage at the implied charge that he was responsible for the Czech uprising; in a speech later that week he called for the removal of the Right SRs from the Moscow Soviet. According to Osipova, the SRs were instigators of peasant revolts. Osipova, Klassovaia bor'ba , 317ff.

lence was everywhere rampant, there was no one to complain to, and in any case complaint was useless. When utter lawlessness reigns, people do not complain but fight over their differences." In sum, "The commissaries themselves are powerless amid the anarchy they have created."[60]

How should we evaluate the critique advanced by the parties of the soviet opposition, the Left SRs and the Mensheviks? It cannot be doubted that many of their criticisms of the Bolshevik food-supply dictatorship were well aimed and that the Bolsheviks were forced, in practice if not in words, to recognize the accuracy of their predictions. The "class struggle in the village" did turn into a "throat cutting"; the worker detachments did disintegrate into drunken bands; bureaucratic red tape did damage commodity exchange with the village. But the positive alternatives put forth by the opposition parties were also weak, especially those of the Left SRs, who wanted to rely on independent local soviets and saw a complete solution only in a revolutionary war against Germany to regain the grain-rich regions. The Menshevik contention that only extensive economic regulation in the style of Groman could solve the problem may have been correct, but it was an irrelevant counsel of perfection under the circumstances. The Mensheviks had begun to understand this flaw and were advocating a retreat from attempts to enforce the grain monopoly in its full rigor. The real question is whether Menshevik demands for a government of socialist unity and for unfettered political freedom were compatible with the imperative of imposing order.

Impractical as the positive suggestions of the Left SRs and the Mensheviks may have been, they were at least couched in language that corresponded to the actual content of the proposed programs. The same cannot be said of the Bolsheviks: the rhetorical dissonance between the class-war rhetoric and the actual program of disciplined centralization was vast and difficult to bridge. Having staked their political reputation on "all sovereignty to the soviets," the Bolsheviks could not say out loud that as predicted, it had all been a terrible mistake and sovereignty would now have to be taken away from the soviets. Their rhetorical cover-up was something more than the usual political hypocrisy and euphemism, and it had important consequences. One has already been mentioned: the opposition parties had to be excluded from the soviets so that they would not "sow panic," that is, so they could not point out that the Bolsheviks' new rhetorical clothing was threadbare. The Bolsheviks were caught in a bind:

[60] Tyrkova-Williams, Why Soviet Russia Is Starving , 11-13, 5-8. The Mensheviks also saw the village soviets as one armed group lording it over the rest. Tyrkova-Williams is somewhat coy about Kadet responsibility for the introduction of the grain monopoly in the first place.

their effort to overcome the crisis of authority depended on public loyalty to a political formula that they themselves no longer fully believed in.

The debates over the food-supply dictatorship in the spring of 1918 have special historical resonance because they mark the point where three visions of the Russian revolution finally parted ways. The intensity with which the Russian intelligentsia believed in the idea of revolution had come in large part from the clash and interplay of these partially conflicting visions of the tasks of the revolution. The spring of 1918 was the end of the road for two of these visions. The revolutionary vision defended by the Left SRs contended that the Russian peasant had something of positive value to contribute to the Russian future. The vision of the February revolution defended by the Mensheviks asserted that the Western model of constitutionalist civilization—not just the technological and organizational dynamism admired by the Bolsheviks—contained many things that Russia must adopt if it were to reach greatness. These visions could not survive the pitiless environment of the time of troubles. The food-supply crisis of 1918 revealed the impoverishment not only of the Russian people but also of the Russian revolution.

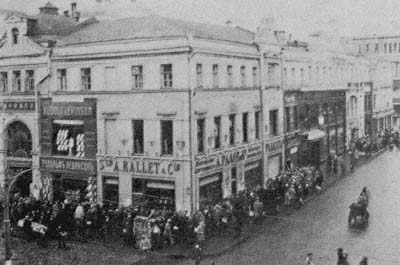

1. Bolshevik propaganda poster, 1920: "The workers and the peasants are

finishing off the Polish gentry and the barons, but the workers on the home

front also have not forgotten about help to the peasant economy. Long live

the union of the workers and peasants!" At the bottom: "Week of the

Peasant." (From N. I. Baburina, ed., The Soviet Political Poster, 1917-

1980, from the USSR Lenin Library Collection [Harmondsworth:

Penguin, 1985], plate 18.)

2. Bolshevik propaganda poster, 1920: "Without a saw, axe, or nails you

cannot build a home. These tools are made by the worker, and he has to

be fed." (From N. I. Baburina, ed., The Soviet Political Poster, 1917-

1980, from the USSR Lenin Library Collection [Harmondsworth:

Penguin, 1985], plate 21.)