II

The first returns from a Virginia no longer ruled by the Virgin Queen, the Jamestown settlement, struck officials of the newly created Virginia Company as putting Raleigh's golden dreams to shame. Writing to Salisbury about the "say" of Virginian gold that Captain Christopher Newport had brought home with him, Sir Walter Cope (1607) is ecstatic:

If we may believe either in words or Letters, we are fallen upon a land, that promises more, than the Land of promise: In stead of milk, we find pearl. & gold in stead of honey. . .. There is but a barrel full of the earth but there seems a kingdom full of the ore you shall not be fed by handfuls or hatfuls after the Tower measure [a sarcastic reference, apparently, to Raleigh and Guiana41 ] But the Elizabeth Jonas & the Triumph & all the Ships of honor may here have the bellies full. (Barbour, Jamestown Voyages 1:108)

The next day, however, Cope rubs his eyes a little more determinedly: "Coming this day to Seal up under our Seals, the golden mineral till your Return It appeared at sight so suspicious That we were not satisfied until we had made four Trials by the best experienced about the city. In the end all turned to vapor" (111). This particular transformation of American trifling (a barrelful of earth yet a kingdomful of ore) into smoke was both cheaper and quicker than the Elizabethan delusions of Frobisher or Raleigh, and seems to have made the Virginia Company even more cautious in its public assertions than Elizabethan colonialists had been; but it did little good for Jamestown itself. Looking back over Virginia's recent history, William Crashaw (1613) sounds as exasperated as almost every earlier pamphlet on the colony when he asserts that "amongst the many discouragements that have attended this glorious business of the Virginian plantation: none hath been so frequent, and so forcible, as the calumnies and slanders, raised upon our Colonies, and the country it self" (Whitaker, Good Newes , A2r). The author of The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia (1612)—either Captain John Smith or a group of his disciples42 —is

Figure 8.

Some vengeful Indians pour molten gold down a greedy Spaniard's throat.

From Theodor de Bry's America part 4, Frankfurt, 1594.

(By permission of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

more specific: the author, like Harriot, complains that not finding gold as the Spanish had is what "hath begot us (that were the first undertakers) no less scorn and contempt, than their noble conquests and valiant adventures (beautified with it) praise and honor" (Smith, Works 1:257).

From the start, in fact, Smith's Proceedings frames itself as an apology, though in the end the inability to find gold proves almost too distant a "defailment" (203) to excuse: the Proceedings has a hard enough time explaining why Jamestown had such trouble locating the one asset of which Virginia could supposedly boast, its fruit. The conquistadores were said to have gone hungry too, insatiably so, but as a plate in Theodor de Bry's America part 4 (1594) made famous, the Spanish had starved for gold (see figure 8). De Bry means of course to mock the Spaniards' "holy hunger" (Eden, Decades , 185);43 yet for many English readers, a life "rich in gold,

but poor in bread" (108-9) must still have seemed an enviable one. To Raleigh himself, for instance, gold remains the only American want that counts: at one point in his journeys, says Raleigh, "nothing on the earth could have been more welcome to us . . . than the great store of very excellent bread which we found in these Canoas "—nothing, that is, "next unto gold" (Discoverie , 43). The Jamestown settlers, however, were often reduced to a far more literal and all-consuming hunger. On one occasion, recorded only in George Percy's manuscript "Trewe Relacyon" (1612), it even drove the Indians to aggravate the particular indignity of de Bry's Spanish tragedy: "Lieutenant SICKLEMORE and diverse others were found . . . slain with their mouths stopped full of Bread being done as it seemeth in Contempt and scorn that others might expect the Like when they should come to seek for bread and relief amongst them" (265).44

And yet the bulk of both the Proceedings and Smith's earlier True Relation (1608) concerns what one would have thought the humiliating subject of Smith's labors to secure food for the colony any way he could. Moreover, not only do the narratives occasionally acknowledge their pecularity in this regard—"Men may think it strange there should be this stir for a little corn, but had it been gold with more ease we might have got it; and had it wanted, the whole colony had starved" (Works l:256)—but Smith at one point goes so far as to make the invidious Spanish comparison himself: "the Spaniard never more greedily desired gold than he victual" (212).45 In fact, Smith and his disciples seem to consider his heroism comprised as much by his bravery in voicing the scandals that others suppress as by his more practical accomplishments. For honesty, Smith repeatedly claims, is the best colonial policy: having recounted a mutiny at Jamestown, he remarks, "These brawls are so disgustful, as some will say they were better forgotten, yet all men of good judgment will conclude, it were better their baseness should be manifest to the world, than the business bear the scorn and shame of their excused disorders" (212). At the same time, however, such boldness certainly irritated his enemies, and helped expose him to attack: according to the Proceedings , many disgruntled colonists "got their passes [home] by promising in England to say much against him" (275). But then Smith insists on outfacing slander against himself as well. At the start of the col-

ony, for example, when he was held prisoner on suspicion of treason, his enemies

pretended out of their commiserations, to refer him to the Council in England to receive a check, rather than by particulating his designs make him so odious to the world, as to touch his life, or utterly overthrow his reputation; but he much scorned their charity, and publicly defied the uttermost of their cruelty. (207)

Later in his life, as we shall see, the implicit correlation here between colonist and colony will become explicit: no longer Elizabeth or even James but the slandered Smith becomes, in his own writings, the best synecdoche for slandered Virginia.

It is no surprise, therefore, that Smith's policy of outfacing slander proves inseparable from his dedication to the dirty business of actual plantation. As prone as other colonial advocates to extolling Virginia—"Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man's habitation being of our constitutions"—Smith must always add a caution to dreamers—"were it fully manured and inhabited by industrious people" (144)—because the scandalous truth he believes most needs facing is that colonization requires work. Even before becoming the colony's president, for instance, Smith along with a cohort "divided betwixt them, the rebuilding our town, the repairing our pallisadoes, the cutting down trees, preparing our fields, planting our corn, and to rebuild our Church, and recover our store-house" (219). Smith's famous hostility toward the idle gentlemen of the colony, those "holding it a great disgrace that amongst so much action, their actions were nothing" (175), is matched on the gentlemen's side, however, by their identification of his "base" speech and views with his low social status: the courtly Edward Wing field declares about Smith, for example, that "it was proved to his face, that he begged in Ireland like a rogue, without license, to such I would not my name should be a Companion" (Barbour, Jamestown Voyages 1:231). As a result, the contemptuous slander that seems most to beset Smith is the odd charge that he appears, in effect, too interested in settlement; he first becomes a prisoner, in fact, "upon the scandalous suggestions of some of the chief (envying his repute) who feigned he intended to usurp the government, murder the Council, and make himself king" (Smith, Works 1:206-7; cf. Percy, "Trewe Relacyon," 264).

For the gentlemen (and the Virginia Company) want, as always, something better than settlement.46 Again and again Smith deplores the "golden promises" that allow the colonists "no talk, no hope, no work, but dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, load gold" (218); what debases a settler, to his mind, is not the "necessary business" of colonization thus "neglected" but the "dirty skill" of gold digging (219). And the best proof for Smith that the colony's gold lovers, not its laborers, are the ones made savage by colonial life is the gold lovers' inability to master the savages they encounter. Virginia's gentlemen seem to Smith incapable of appreciating that, just as they themselves will do anything for gold, so the equally "idle" Indians will do anything for "baubles of no worth" (257), on one occasion suffering "pains" for Smith that "a horse would scarce have endured, yet a couple of bells richly contented them" (73).47 The gentlemen, that is, cannot fathom a naïveté they share. In fact, their own idleness makes them so addicted to trading for food rather than growing it that, like the foolish English consumer or conventional savage, they would willingly sacrifice their own valuables:

Of . . . wild fruits the Savages often brought us: and for that the President [Smith] would not fulfill the unreasonable desire of those distracted lubberly gluttons, to sell, not only our kettles, hoes, tools, and Iron, nay swords, pieces, and the very ordnance, and houses, might they have prevailed but to have been but idle, for those savage fruits they would have imparted all to the Savages; especially for one basket of corn they heard of, to be at Powhatan's, 50 miles from our fort, though he [Smith] bought near half of it to satisfy their humors, yet to have had the other half, they would have sold their souls, (though not sufficient to have kept them a week). (264)

By this account, minds hungry for gold ultimately mean the same thing as souls reduced to a paltry half-basket's worth of "savage fruits."48

Smith himself, on the other hand, ostensibly proportioned to the baseness of scandal, labor, and ungentlemanliness, presents himself as simply indifferent to material representations of his own value. As he declares in the dedication of the work prefixed to the Proceedings , his Map of Virginia : "Though riches now, be the chiefest greatness of the great: when great and little are born, and die, there is no difference: Virtue alone makes men more than men: Vice, worse than brutes" (Works 1:133).49 The practical up-

shot of this chaste idealism is that Smith, recognizing trifles for what they are, can most ably employ them. In a famous trading incident with the local Indian lord Powhatan, Captain Christopher Newport, the leading light of the colony's gold party,50 makes grand gestures that, according to Smith, only reduce Newport to the savage's level: "Thinking to out brave this Savage in ostentation of greatness, and so to bewitch him with his bounty, as to have what he listed," Newport ends up getting corn from Powhatan "at such a rate, as I think it better cheap in Spain, for we had not 4. bushels for that we expected 20. hogsheads."51 Smith, however, then

glanced in the eyes of Powhatan many Trifles who fixed his humor upon a few blue beads; A long time he importunately desired them, but Smith seemed so much the more to affect them, so that ere we departed, for a pound or two of blue beads he brought over my king for 2 or 300 bushels of corn, yet parted good friends. (217)52

In one stroke, by the mere pretense of trifling attachments, Smith both acknowledges the scandalous hunger of the English and demonstrates their high-minded superiority to it.

Perhaps the most dating presentation in the Map and Proceedings of this particularly "disgraceful" brand of sprezzatura appears, appropriately enough, in some frivolous-seeming preliminary material, a brief vocabulary of Indian words (136-39). What looks frivolous about the vocabulary, besides the "savage" words themselves,53 is that Smith lists too "few" of them to make the vocabulary useful,54 makes jokes about the list (for instance, by inserting among the words for land, stone, water, and fish the Indian term for cuckold), and then ends with a peculiar dramatic dialogue between himself and an Indian55 (I quote only the English lines):

I am very hungry, what shall I eat?

[W]here dwells Powhatan?

Now he dwells a great way hence at Orapaks.

You lie, he stayed ever at Werowocomoco.

Truly he is there I do not lie.

Run you then to the king mawmarynough and bid him come hither.

Get you gone, and come again quickly.

Bid Pocahontas bring hither two little Baskets, and I will give her

white beads to make her a chain.

(139)

It is not only by the mention of hunger that the passage seems to court the slander the Proceedings is meant to answer, for the reference to Pocahontas raises what the Proceedings treats as the most serious charge against Smith, the slander that he had proven himself so debased as to want to live not just like a savage but with one. Even the later passage recording this charge wavers between repudiating and entertaining it:

Some prophetical spirit calculated he had the Savages in such subjection, he would have made himself a king, by marrying Pocahontas, Powhatan's daughter. It is true she was the very nonpareil of his kingdom, and at most not past 13 or 14 years of age. Very oft she came to our fort, with what she could get for Captain Smith, that ever loved and used all the Country well, but her especially he ever much respected: and she so well requited it, that when her father intended to have surprised him, she by stealth in the dark night came through the wild woods and told him of it. But her marriage could no way have entitled him by any fight to the kingdom, nor was it ever suspected he had ever such thought, or more regarded her, or any of them, than in honest reason, and discretion he might. (274)

The similarity to Raleigh is striking, with the equally striking difference that now Raleigh's exceptional Indian woman has a name. The conclusion to the passage demonstrates just how closely Smith's professed ambivalence toward Pocahontas resembles Raleigh's self-restraint: "If he would he might have married her, or have done what him listed. For there was none that could have hindered his determination."56 In the vocabulary itself, the inter-play between hunger at the beginning and Pocahontas at the end increases the sense of Smith's indebtedness to Raleigh: where the disgraced Raleigh used the "threat" of intermarriage to help represent its alternative, gold lust, as chastity, Smith might be thought to dally with Pocahontas so as to distract his readers from his need for food. Yet, as Smith himself will admit, it is one thing to desire gold and another to desire food; and ultimately the difference between the two is only made more pronounced by Pocahontas's inclusion in the little narrative that Smith's hunger motivates. As the Proceedings will show, the entirety of the dialogue, not just its first line, concerns the colony's food problems: Powhatan moved to Orapaks in the hope of cutting the English off from his own provisions (147, 173, 256, 261); the baskets Smith

wants from Powhatan's still obliging daughter are baskets of corn (212, 246, 250, 251, 255, 264); and the beads he promises Pocahontas are only "such trifles" as have always "contented her" (True Relation , 95).57 Just as at one point Smith releases some Indian prisoners to Pocahontas, "for whose sake only he feigned to save their lives and grant them liberty" (221; my emphasis), so in the vocabulary's dialogue, it would seem, Smith only trifles with Pocahontas, as with all baseness, to his advantage.

Yet this otherwise plausible explanation of the passage discounts the real peculiarity of the Pocahontas line, whose change in tone and temporal inconsequence make it sound like a dreamy afterthought, connected to the previous dialogue only through information the text has yet to provide, and then still detached by Smith's evocation of merely "little" food baskets. One might claim that, by his pretense of affection for the savage girl he elsewhere fools, Smith is trifling with the reader. This view seems strengthened by the character of the epistle just prior to Smith's vocabulary, perversely dedicated by one T. A. "To the Hand": "Lest I should wrong any in dedicating this Book to one: I have concluded it shall be particular to none" (135). T. A.'s superiority to patrons soon becomes a flippancy toward readers in general: "If it [the book] be disliked of men, then I would recommend it to women, for being dearly bought, and far sought, it should be good for Ladies." The proverb here (Tilley, Proverbs , D12) invokes a whole field of antifeminist sentiment in which woman represents the naive trifler par excellence. In Robert Wilson's play The Three Ladies of London (1581), for instance, Lady Lucre grants her favor to the Italian merchant Mercatore only after he promises her "secretly to convey good commodities out of this country" for her sake:

And for these good commodities, trifles to England thou must bring.

As Bugles to make baubles, colored bones, glass, beads to make bracelets withal:

For every day Gentlewomen of England do ask for such trifles from stall to stall.

And you must bring more, as Amber, Jet, Coral, Crystal, and every such bauble,

That is slight, pretty and pleasant; they care not to have it profitable.58

But if T. A.'s use of the proverb suggests his disdain for the readers whom he considers either churlish or trifling, unable to appreciate the value of a book defending scandal-ridden Virginia, the rest of his epistle makes a surprising about-face on the subject not only of patronage but of trifle-loving women:

When all men rejected Christopher Columbus: that ever renowned Queen Izabell of Spain, could pawn her Jewels to supply his wants; whom all the wise men (as they thought themselves) of that age contemned. I need not say what was his worthiness, her nobleness, and their ignorance, that so scornfully did spit at his wants, seeing the whole world is enriched with his golden fortunes. Cannot this successful example move the incredulous of this time, to consider, to conceive, and apprehend Virginia, which might be, or breed us a second India? hath not England an Izabell, as well as Spain, nor yet a Columbus as well as Genoa? yes surely it hath, whose desires are no less than was worthy Columbus, their certainties more, their experiences no way wanting, only there wants but an Izabell, so it were not from Spain. (Smith, Works 1:135)

Now there are two kinds of women: the ones idler than men, trading substance for the insubstantiality more appropriate to them; or the ones wiser (and richer) than men, recognizing the substance in what appears insubstantial, as they too are greater than they appear. If England has the heroes—preeminently, of course, Smith who are capable of turning trifling Virginia to gold, it nevertheless lacks the patrons capable of believing in a colony that, like Smith himself, has been "traduced" as "base, and contemptible" (True Declaration , 6). "Only there wants but an Izabell, so it were not from Spain"—England, that is, only wants its "good Queen Elizabeth" (Smith, Works 1:403).59 In light of this longing, the delicacy with which Smith treats the Indian princess in whom he supposedly feigns interest betrays the complexity of his position as a Jacobean colonist. Pocahontas, that is, combines the foolish and the royal woman:60 already suggestig—as a virgin, not a virgin land the constriction of special relations between England and America, Pocahontas as royal virgin seems also to figure the displacement of sublime trifling from England, while as a savage virgin she represents the impossibility of locating such potentiality in America. In other words, the only option for Jacobean trifling as Smith sees it seems to be its internalization in the figure of the unsettled colonist himself the man John Davies

of Herefordshire calls "Brass without, but Gold within" (Poems , 320).61

For the Proceedings is not content merely to excuse the shortcomings of the colonists: "Peruse the Spanish Decades, the relations of Master Hakluyt," it challenges, "and tell me how many ever with such small means, as a barge of 2 Tons; sometimes with 7. 8.

9, or but at most 15 men did ever discover so many fair and navigable rivers; subject so many several kings, peoples, and nations, to obedience, and contribution with so little blood shed" (258). So confident are Smith and his men in their own "small" abilities that they can risk invoking the possibility of their utter divorcement from England: angered by the company's replenishing Virginia only with delinquents, Smith exclaims, "Happy had we been had they never arrived; and we for ever abandoned, and (as we were) left to our fortunes" (269). The grandest manifestation of this self-reliant littleness is, of course, the lowly (and short) figure who comprehends the colony in himself (see figure 9). For Smith, indeed, the man best suited to colonial work is the one as beggarly-looking as he: "Who can desire more content, that hath small means; or but only merit to advance his fortune, than to tread, and plant that ground he hath purchased by the hazard of his life?" (343).

Yet this Spenserian intensification of trifling, which presents Smith as free from proportionment to objective correlatives such as gold or food or the English island, works in the end, as it had for Spenser, to undermine Smith's relation to any "ground" whatsoever. Though improvements on the laboring gentleman depicted by Raleigh, Smith's few planters maintain a crucial detachment from their work by its very voluntariness:

Let no man think that the President, or these gentlemen spent their time as common wood-hackers at felling of trees, or such like other labors, or that they were pressed to any thing as hirelings or common slaves, for what they did (being but once a little inured) it seemed, and they conceited it only as a pleasure and a recreation. (238-39)62

Indeed, the only matter Smith admits to be truly pertinent to him is his own heroically errant body; as he declares in the dedicatory epistle to the Map , anticipating T. A.'s own dedication "To the Hand": "My hands hath been my lands this fifteen years in Europe, Asia, Afric, or America" (133).63

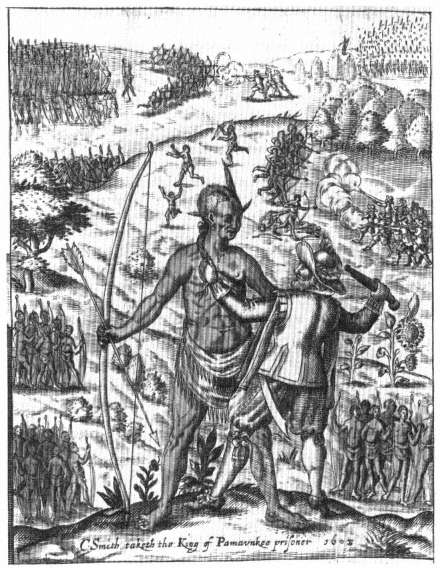

Figure 9.

"C[aptain] Smith Taketh the King of Pamaunkee Prisoner 1608," enlargement from

"A Description of Part of the Adventures of Cap: Smith in Virginia," in The Generall

Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles , by Captain John Smith,

London, 1624. The image of Smith dominating a larger Indian is echoed in the back-

ground by the image of English colonists, outnumbered, withstanding an Indian

attack. (By permission of the Beinecke Library, Yale University.)

A few years later in Smith's career, however, this self-possession begins to look less satisfying: writing in the Generall Historie (1624) about his experiences in both Virginia and New England, Smith complains that "in neither of those two Countries have I one foot of Land, nor the very house I builded, nor the ground I digged with my own hands, nor ever any content or satisfaction at all" (Works 2:326). The commendatory poems that once praised Smith's contempt for riches can now as easily bemoan his lack of reward: "Truth, travail, and Neglect, pure, painful, most unkind, / Doth prove, consume, dismay, the soul, the corpse, the mind" (51).64 Moreover, as a New World traveler superior to any grounds for praise other than himself, Smith becomes increasingly unable even to reach America, let alone possess it: leaving Jamestown due to a serious injury in 1609, he briefly journeys to New England in 1614, sets out again in 1615 but is forced to return for repairs, tries once more in 1615 but runs into pirates, then in 1617 his ships prove unable even to leave Plymouth harbor—and he never sails again.65 As his "Prospectus" for the Generall Historie concludes, after "the expense of a thousand pound, and the loss of eighteen years of time, besides all the travels, dangers, miseries and encumbrances for my country's good, I have endured gratis," "these observations are all I have" (Works 2:16).

A version of this complaint, however, had already appeared in the dedication to the Map : "Having been discouraged for doing any more, I have writ this little" (Works 1:133). Yet, he adds, his hands have always been his lands; even when he writes the Map , in other words, the only reward that the self-reliant Smith claims to expect proceeds from himself alone, from the hands that now produce not deeds but books.66 It would be a mistake to conclude, therefore, that Smith turns to writing only as a meager compensation for a life of "defailments." He had written at least one book, the True Relation , even as a colonist; and both the volume and the frequency of his later literary efforts make his career as a writer seem anything but an unnatural sequel to his career as a colonial trifler. The only English voyager to America before Smith to publish more than one tract about his adventures was Raleigh, who published two; yet Smith produced five wholly devoted to the New World A True Relation (1608), A Map of Virginia and The Proceedings (1612), A Description of New England (1616), New Englands

Trials (1620, 1622), and the Generall Historie (1624)—as well as one about his travels throughout the world—The True Travels (1630)— and three of advice to voyagers and planters generally—An Accidence (1626), A Sea Grammar (1627), and his last work, Advertisements for the Unexperienced Planters of New England, or Any Where (1631). Indeed, Smith proves almost as prolific a writer about America as the great editors Eden, Hakluyt, and Purchas, to whom he even prefers himself as an editor, on the basis of his actual colonial experience: "Had I not discovered and lived in most of these parts, I could not possibly have collected the substantial truth from such an infinite number of variable Relations" (Works 2:16; cf. 41, 44, and 3:288). At times, it is true, Smith worries that writing has taken the place of more vigorous labor on his part—as he says in a preface to the Description , "I confess it were more proper for me, To be doing what I say, than writing what I know" (Works 1:311; cf. 422)—and till the end he declares himself ready to make his words good, unlike those who "could better guide penknives than use swords" (Works 3:301). Yet he ultimately displaces the invidious comparison between his writing and his soldiering into the mouths of his inevitable detractors—"Envy hath taxed me to have writ too much, and done too little" (Works 3:141)—and decides instead that his books only complete the heroic picture of himself that his soldiering had begun. Conventionally modest about his literary abilities in the dedication of his Generall Historie , Smith wonders, "Where shall we look to find a Julius Caesar, whose achievements shine as clear in his own Commentaries, as they did in the field?" (Works 2:41); but a commendatory poem a few pages later declares, unsurprisingly, that one need look no further than Smith (50); and the identification becomes, in Smith's works anyway, a commonplace (317, and 3:47, 142, 145, 147)—he could not, after all, be a complete Caesar without his books.

In fact, the more Smith "disgraces" himself by merely writing, the more he grows to admire himself. "This great work [of colonization], though small in conceit, is," he declares, "not a work for every one to manage . . . [;] it requires all the best parts of art, judgment, courage, honesty, constancy, diligence, and industry, to do but near well" (Works 3:301; cf. 1:327-28). And, though Smith may, in exhorting James, claim that "nothing but the touch of the King's sacred hand can erect a monarchy" (2:43), he later asserts

of Virginia, New England, and Bermuda "that the most of those fair plantations did spring from the fruits of my adventures and discoveries" (3:13).67 According to his final work, the Advertisements , published more than twenty years after he last saw Jamestown, Smith's ostensible failure continues only to assimilate him to England's colonies all the more:

Now if you but truly consider how many strange accidents have befallen those plantations and my sell how oft up, how oft down, sometimes near despair, and ere long flourishing; how many scandals and Spanolized English have sought to disgrace them, bring them to ruin, or at least hinder them all they could; how many have shaven and cozened both them and me, and their most honorable supporters and well-willers, cannot but conceive God's infinite mercy both to them and me.

As the passage continues, however, Smith so overtakes Virginia in misadventure that he takes center stage:

Having been a slave to the Turks, prisoner amongst the most barbarous Savages, after my deliverance commonly discovering and ranging those large rivers and unknown Nations with such a handful of ignorant companions, that the wiser sort often gave me for lost, always in mutinies, wants and miseries, blown up with gunpowder; A long time prisoner among the French Pirates, from whom escaping in a little boat by my sell and adrift, all such a stormy winter night when their ships were split, more than an hundred thousand pound lost, we had taken at sea, and most of them drowned upon the Isle of Ree, not far from whence I was driven on shore in my little boat, etc. And many a score of the worst winter months lived in the fields, yet to have lived near 37. years in the midst of wars, pestilence and famine; by which, many an hundred thousand have died about me, and scarce five living of them went first with me to Virginia, and see the fruits of my labors thus well begin to prosper: Though I have but my labor for my pains, have I not much reason both privately and publicly to acknowledge it and give God thanks. (Works 3:284-85)

Oddly, and yet characteristically, the separation here between the "fruits" of the colonies and Smith's "labor" for them constitutes, in this context of Smith's glorious ills, not so much a lamentation as a boast. It stakes Smith's exclusive claim to the colonies at the same time as it frees him from any proportionment to them. If earlier in his career he had described the colonies, in terms marking his alienation from England, as "my wife" (and also "my children. . . my hawks, my hounds, my cards, my dice, and in total

my best content, as indifferent to my heart as my left hand to my right") (1:434), this identification by the end of his life has come to mean that such "marriage" ties restrict everyone except the long-suffering (and otherwise bachelor) Smith himself.

In place of the material substance or "content" Smith persistently confesses himself to lack, however, actual women become more, not less, important to him. His ill fortune, that is, causes him increasingly to advertise his dependence on noble ladies, Isabelis who see the value in ostensible poverty and so "record" his "worth" (3:145). As Smith explains to the Duchess of Richmond and Lenox, in a passage matching the list of his woes in the Advertisements ,

Yet my comfort is, that heretofore honorable and virtuous Ladies, and comparable but amongst themselves, have offered me rescue and protection in my greatest dangers: even in foreign parts, I have felt relief from that sex. The beauteous Lady Tragabigzanda, when I was a slave to the Turks, did all she could to secure me. When I overcame the Bashaw of Nalbrits in Tartaria, the charitable Lady Callamata supplied my necessities. In the utmost of many extremities, that blessed Pocahontas, the great King's daughter of Virginia, oft saved my life. When I escaped the cruelty of Pirates and most furious storms, a long time alone in a small Boat at Sea, and driven ashore in France, the good Lady Madam Chanoyes, bountifully assisted me. (Works 2:41-42)

That blessed Pocahontas"—no longer, it seems, can Smith afford his former irony toward the women who supply Elizabeth's lack.68 Yet the sheer number of these "incomparable" women continues to weaken Smith's attachment to any one of them in particular; if anything, indeed, the attachment is on the side of the woman, like Tragabigzanda, who hopes to make Smith her husband (3:186-88, 200), or Pocahontas, who later calls Smith her father.69 A canny parody of Smith published the same year as the Advertisements , David Lloyd's Legend of Captaine Jones (1631), ridicules Smith's pose of embattled chastity by referring not only to Jones's "grace with thy great Queen Eliza" and then to "thy London widow next in love half-drown'd, / Which thou refus'dst with forty thousand pound," but, most tellingly, to "th'amorous ways / The Queen of No-land us'd to make thee King / Of her and hers" (16-17).70 Yet in mocking Smith by transforming him into a Spenserian knight, Lloyd only reveals the extraordinary degree to which the chaste

Smith has indeed answered Spenser's call for an Englishman at once sublimely motivated by a transcendent love and yet not exclusively attached, either to Elizabeth or England—resisting even the Queen of No-land.

The problem is that Smith answers Spenser's call only too well, transforming every attachment into the semblance of one, into a proof of his own incomparable potentiality; one might say, in fact, that where Spenser hoped to see his books realized as colonies, Smith ends up realizing his colonies as books. If for some readers Smith's adventures could therefore look so detached from the material world as to seem "above belief," even "beyond Truth,"71 for others such ungrounded mobility could also end up an ideal in itself: The True Travels arose, Smith says, when some noble readers asked him "to fix the whole course of my passages" not just incidentally, in a colonialist tract, but "in a book by itself" (Works 3:141). Even the tracts, however, reflect the increasing conration of Smith's travails and writing that leads to these solitary "passages" of the Travels . A commendatory poem to the Generall Historie praises Smith for imparting America "to our hands," "There by thy Work , Here by thy Works " (Works 2:52), and Smith goes on to acknowledge the continuity between these two modes of colonial labor: "Thus far," he exclaims at the end of book 4, "I have traveled in this Wilderness of Virginia" (Works 2:333). Indeed, Smith later suggests that his writing is the greater labor of the two: continuing the history of the colonies in his Travels , Smith declares that "I have tired my self in seeking and discoursing with those returned thence, more than would a voyage to Virginia" (Works 3:215).72 So untrammeled by a material relation to the colonies has Smith's indelicate labor for them become that he no longer requires any other field of honor as a colonist than the still more scandalous "lands" of his "hands"—not his work but his Works .