7—

A Libelous Affair:

The Querelle de la Belle Dame sans merci and the Prospects for a Legal Response

Her voice—of all her admirables the admirablest, the very pitch and timber of La Belle Lettre sans merci.

John Barth, Letters

In late-medieval France, the feme/diffame problem took another important turn legally. What had prompted Jean LeFèvre's conversion and Christine de Pizan's ethical critique of Jean de Meun's Rose could also occasion juridical accusations. The problem of damaging women's names, indeed one might say of "de-naturing" them (di-ffame ), became a matter of litigation and public redress. Writers and poets could be charged according to a legal definition of defamation.

Formulating the problem of defamation in legal terms taps into an immense body of speculation that extends all the way back to Justinian's Code and Roman law. The canonical conception described defamation as an unjust harming of another's reputation (injusta alienae famae laesio ).[1] This harm could take many forms and occur in many places. As Justinian's Code outlined it:

Si quis famosum libellum sive domi sive in publico vel quocumque loco ignarus reppererit, aut corrumpat, priusquam alter inveniat, aut nulli confiteatur inventum. Sin veto non statim easdem chartulas vel corruperit vel igni consumpserit, sed vim earum manifestaverit, sciat se quasi auctorem huiusmodi delicti capitali sententia subiugandum.[2]

If anyone should find defamatory material in a house, in a public place, or anywhere else, without knowing who placed it there, he must either tear it up before anyone else finds it or not mention to anyone that he has done so. If, however, he should not immediately tear up or burn

the paper, but should show it to others, he is notified that he will be liable to the punishment of death as the author.

Defamation involves an attack on a person enacted symbolically. The fact that it targets the symbolic entity of a reputation and not a body does little to diminish its seriousness. In such a world, where words were not yet sundered from deeds, defamation was tantamount to physical assault. Hence the defamer or the one who collaborates in defamation is subject to corporal punishment—even death. As medieval canon and customary law continued to propound Justinian's statute, its stringent force varied little: in Gratian's rendition, defamation was a verbal infraction and the defamer, a criminal who must take a beating.[3]

When it comes to the cause of a poet, this prevailing medieval conception of verbal injury poses a variety of questions: in what way is a speaker or writer accountable to the public?; are texts actionable?; if so, how are they rendered liable for damages? It also raises key issues concerning the social parameters of discourse and the controls developed to enforce them. At stake is that charged rapport between language and action—the relay between verbal representation, its effects, and the public regulation of both. For jurists and poets of the late Middle Ages, defamation offered a crucial model for reckoning with the power of discourse. Since it attempts to account for the influence of linguistic forms on its audiences and the public domain as a whole, defamation charts the boundaries of responsibility: the place where a party assumes, in legal terms, liability.

Nowhere is the juridical problem of defamation of women more clearly articulated than in the controversy provoked by Alain Chartier's Belle Dame sans merci .[4] The title of this fifteenth-century courtly poem hints at the Querelle that ensued. Portraying the lady as merciless prompted immediate and vehement reactions. In fact, Chartier's Belle Dame seems to have polarized the court of Charles VII, where it first circulated in 1424. It touched off a far more acrimonious debate than the Querelle de la Rose a generation earlier. This is hardly surprising, given the state of civil war in France at the time: internecine rivalries between Armagnac and Burgundian factions divided the royal court where Chartier served as secretary. A group of anonymous courtiers lodged the first complaint, objecting to the way the poem acts to "disrupt the quest of humble servants, and snatch from you [women] the happy name of mercy" (rompre la queste des humbles servans et à vous tolir l'eureux nom de pitié; Laidlaw, 362). Chartier answered with his own Excusacioun aus dames , patterned after Jean

de Meun (Rose , lines 15129–212). It was the second work that sparked a woman's response. And La Response des dames faicte a maistre Alain , attributed to "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie," launched an indictment of defamation.[5] The confrontation between Chartier's Belle Dame / Excusacioun and the Response des dames brought out the legal problem of the text's public accountability. It is difficult to ascertain if and how this confrontation was ever adjudicated. The Querelle de la Belle Dame continued to be played out in the years thereafter; a flurry of poems were composed in defense of Chartier's poem. Yet despite its inconclusiveness, the affair retained its legalistic tenor.

With its legal conception of defamation, this little-known Querelle pushes our investigation into the symbolic domination of masterly writing about women still further. We should first recognize it as another disputational encounter between a well-known courtly text and a woman's response, this time involving a poet in his prime. Yet the recourse to legal models in the woman's response to Chartier's Belle Dame changes the very terms of such a disputation. Invoking the law of defamation adds a novel and powerful criterion to the medieval critique of masterly representations of women.

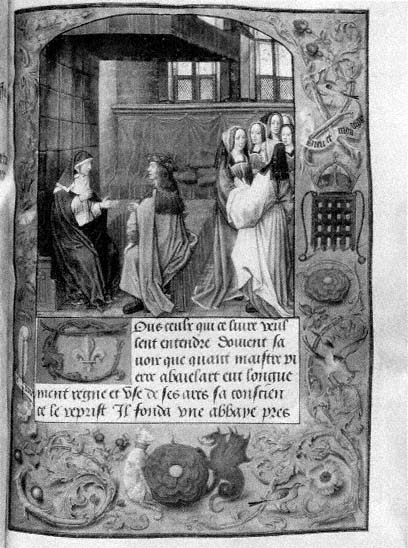

At the same time, the Querelle de la Belle Dame highlights the considerable difficulties in interpreting the woman's response in any disputation. The major pitfall, as ever, is the stereotype of the defaming woman.[6] In the reception of the Querelle de la Belle Dame , this stereotype comes through in the efforts to identify the respondents with the damoiselles d'honneur so frequently depicted in contemporaneous manuscripts (Figure 13).[7] While there are favorable images of a close-knit circle of loyal women—such is the case of the Champion des dames miniature—there are also unfavorable images. The identification of "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie" with such damoiselles reproduces the negative portrayal of them found throughout chronicle literature of the early fifteenth century.[8] It stigmatizes them with the clichéd reputation of damoiselles d'honneur as gossips and bad-mouthers. The modern critical tendency to name the respondents as such women of the court reconfirms unwittingly the favorite clerical exemplum of damoiselles for calumny.[9]

Secondly, the reading of the Querelle de la Belle Dame as a politicized literary game elides the specific character of the woman's response.[10] It is based on the premise that the respondents are figures caught up in the intrigues of courtly ritual. It takes them to be pawns in the hands of more powerful political players.[11] Whether the respondents are allied with the Armagnac or Burgundian camp, whether they are deemed actual women or figurative ploys manipulated by these camps, the result is much the

13. A circle of dames and damoiselles d'honneur. Le Champion des dames .

Grenoble, Bibliothèque Municipale, BM Rés. 352, fol. 384 verso.

Courtesy of the Bibliothèque de Grenoble, France.

same. Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie are seen as formidable opponents to Chartier when women are linked deterministically to defamation. This dismissive reading of the Querelle de la Belle Dame rides on the cliché that women are exemplary defamers.

If our analysis of the woman's response has demonstrated anything, it

is the imperative of breaking out of the vicious circle that defines women's language pejoratively. In the case of the Querelle de la Belle Dame , this means shifting the focus away from the respondents as women—ergo, as defaming women. Such a focus has reinforced commonplace medieval views of the feminine and obscured the innovation that is the Querelle 's central strategy: pursuing a defamatory text legally. By moving attention away from the gender typecasting, we can better gauge the effects of the woman's response in this Querelle . Whether "Jeanne," "Katherine," and "Marie" represent women or men is not the determining issue. What matters more is the consequence of their interventions. If we attend to what I have called the chiasmic link between respondent figures and their context, we are in a better position to discern the implications of their legal charge of defamation.

The Sting of Verbal Injury

The medieval law of defamation hinges first and foremost on the concept of injury (laesio/iniuria ).[12] The Response des dames to Maître Alain's Belle Dame involves testing such a principle of verbal injury on a particular figuration of women. It attempts to assess the connection between the representation of something hurtful and hurtful representation. The Response des dames does not object to the portrait of the pitiless lady but to the transfer of such a portrait from a specific female persona to other women. It questions how the poet gets from the figure of a merciless lady (dame est sans mercy, line 4) to representing existing women as cruel (nous sommes crüelles, line 19).

On closer inspection, we discover that the contested figure is an unattached woman:

Je suis france et france vueil estre,

Sans moy de mon cuer dessaisir

Pour en faire un autre le maistre.

(lines 286–88)

I am free and wish to remain free, without relinquishing my heart to make another its master.

Repeated obsessively throughout the Querelle , Chartier's version of a woman's liberty gets to the core of medieval representations that code female separateness as merciless.[13] When read conventionally, it converts women's freedom into an instrument of torture for men. That woman speaks her freedom wounds her male interlocutor; that she speaks a desire to have no master is liable to kill him. The Belle Dame 's claim brings out

the tortuous impulses informing so much of medieval amorous discourse. Yet read another way, her claim also stands as the credo of a free agent. It suggests a noncommittal stance, one that identifies the woman on her own terms, in relation to no one else. The crux lies in the fact that Chartier's poem allows for both readings. It showcases a woman able to claim her franchise , yet it reprimands her for her liberty's cruel ends—the lover's death.[14] It should not be forgotten that this "free woman" is also set up as a negative exemplum to Chartier's audience:

Et vous, dames et damoiselles

En qui Honneur naist et asemble,

Ne soyés mie si crüelles,

Chascune ne toutes ensemble.

(lines 793–96)

And you, ladies and young women, in whom honor is born and resides, never be so cruel, not one of you, nor all of you together.

According to the Response , what risks being defamatory is the depiction of a woman's freedom as nefarious. It is this perverse figure of her independence that appears objectionable. This finding is highly ironic. As any reader of medieval love poetry knows, there could be no more banal portrayal. Before Chartier, there was a good two-century run of the merciless female type. Yet it is the one element distinguishing Chartier's variation on a hackneyed image that changes the picture. A female persona who is both liberated and a murderer brings to a head the problem of injurious representation. She epitomizes the cause of verbal injury.

I should mention that such a contested figure of la femme france may well carry another political charge. Chartier's figure also conjures up the female personification, La France . During this period of foreign occupation and deep civil unrest, her freedom was most certainly under attack. As Chartier portrayed her in the Quadrilogue invectif , she was the butt of considerable verbal abuse.[15]

By singling out Chartier's negative characterization of a woman's franchise , the Response points to a transfer mechanism whereby the exasperation of men is displaced onto women. In the poetic economy of the Belle Dame , such a mechanism dictates the fate of the lover and his final denunciation of the woman. Yet as the Response des dames maintains, it also applies to the condition of the poet: "don't assign your madness to women" (ne charge point ta frenesie aux femmes, line 15). Chartier's "madness" is the corollary of the lover's characteristic malaise. To put it another way, this "male malady" is an animus driving the text of the Belle Dame as much as it drives the lover's hostile speech acts toward the free-standing woman. It functions as the motor of the poem. By identifying frenesie as

an animus of Chartier's work, the Response des dames takes the allegation of defamation one step further. Not only does it field the threat of verbal injury, but it attempts to explain its processes. It offers a reason why a language defamatory toward women occurs.

Here we can discern the fundamental difference separating the Response des dames from the courtiers' complaint against the Belle Dame sans merci . Whereas the Response tackles the issue of verbal injury legalistically, the complaint is concerned only with the ways Chartier's persona threatens the courtiers' poetic models and social role. The terms of their objection quoted above make this clear. "The quest of humble servants" takes precedence over "the woman's happy name of mercy." The rituals of courtly life, as men perform them, outweigh the value of a woman's reputation. Or to invoke another expression of the galants , "the damage to and estrangement of the humble servants" caused by the Belle Dame is more serious than "the diminishing of the women's power" (dommage et esloingnement aux humbles servans et amandrissement de voustre pouoir, 362). For all the anguish experienced on behalf of women, the courtiers' challenge to Chartier's work comprises a self-absorbed lament. Caught in this narcissistic bind, it can never address the problem of injurious language. While its rhetoric may imply it, its argument never pursues it.

Emblematic of the Response 's focus on verbal injury is the scorpion image:

Tu es ainsy comme l'escorpion.

Tu oingz, tu poins, tu flattes, tu offens,

Tu honnoures, tu fais bien, tu le casses,

Tu t'acuses et puis tu t'en deffens,

Tu dis le bien, tu l'escrips, tu l'effaces.

(lines 24–28)

You are thus like the scorpion. You speak unctuously, you sting; you flatter, you attack; you honor, you do good, you destroy it; you accuse yourself and then you defend yourself; you say the right thing, you write it, you erase it.

This figure captures the menace of words; indeed, it is a canonical image used to describe slander.[16] In keeping with medieval bestiary lore, the scorpion illustrates a type of poisonous harm: its sting could be fatal. With one deft metaphoric stroke, then, the Response des dames turns Chartier's persona of the murderous Belle Dame back on itself. It shows its baleful influence to register not on lovers and courtiers but on the public of women. At the same time, the Response 's scorpion image is seen to injure discreetly and deceptively. Unlike the animalistic images that assault the Bestiaire respondent, it attacks under cover. This aspect of the image gives

us a clue to the resistance the Response faces. It implies Chartier's denial of the very notion of verbal injury. Let us not forget, the women's text responds to the Excusacioun as well as to the Belle Dame , and it is Chartier's second text that elaborates strategies for outmaneuvering the Response 's subsequent charge of defamation. The scorpion's flailing motions, the swift turnabouts in position, suggest the evasiveness of the Excusacioun . One example will make the point. In the God of Love's interrogation of the besieged poet, Cupid asserts:

Tu fais et escriz et envoyes

Nouveaulx livres contre roes droiz.

Es tu foul, hors du sens ou yvre,

Ou veulx contre moy guerre prendre,

Qui as fait le maleureux livre,

Dont chascun te devroit reprendre,

Pour enseigner et pour aprendre

Les dames a geter au loing

Pitié la debonnaire et tendre,

De qui tout le monde a besoing?

(Excusacioun , lines 23–32)

You compose, write, and send off new books against my laws. Are you mad, out of your mind, or drunk? Or do you want to wage war against me? Who has composed this accursed book from which each person must gain from you how to teach and instruct ladies to banish that elegant and tender Pity, of which everyone is in need?

To which the writer of "this accursed book" replies:

Leur serviteur vueil demourer

Et en leur service mourray,

Et ne les puis trop honnourer

N'autrement ja ne le vourray;

Ains, tant qu'en vie demourray,

A garder l'onneur qui leur touche

Employeray ou je pourray

Corps, cuer, sens, langue, plume et bouche.

(lines 145–152)

I wish to remain their servant and die in their service [of women]. And I could not honor them any more, nor vow to it in any other way. So, for as long as I shall remain living, I shall use as I can, body, heart, senses, tongue, pen, and mouth to guard their honor from whatever concerns them.

By placing this critique in the mouth of the God of Love, Chartier shifts the burden of responsibility. Indeed, by representing the writer as apologetic

to Cupid alone, he makes the writer subject to a mythic authority. Chartier and his poem will stand corrected only before the supreme literary arbiter of the law. With such a scene, Chartier tries to neutralize the courtiers' complaint and the Response des dames . Yet in the terms of the Response 's scorpion image, the shifts between admitting the damaging quality of the Belle Dame and protesting the poet's honorable service of women accentuate the injuriousness of Chartier's writing. They substantiate the injury. The fact that the Excusacioun accommodates both the flattery and the attack, the acknowledgement of guilt and the implicit disavowal of it, epitomizes its continuing harmfulness. Moreover, this vacillation applies to the relation between the Belle Dame and the Excusacioun as well. By entertaining the problem of harmful representation only to leave it in suspense, the second text aggravates the danger of the first. Read together, Chartier's poems exacerbate the injury.

A Literary Disclaimer

We come here to a key stage in our inquiry into the effects of the women's legal charge of defamation. In the confrontation between the Response and the Excusacioun , we can detect signs of the struggle over the criterion of verbal injury. These two texts signal changes in the conceptualization and social uses of defamation in French late-medieval culture. On the one hand, the Response 's extremist language signals the power invested in the legal principle of verbal injury. On the other, the Excusacioun 's evasiveness intimates the strategies being developed to block it. If the Response is legitimated by long-standing juridical and philosophical conceptions of defamation, it also faces tactics designed to deflect the allegation of injurious language, tactics that have everything to do with the status of literary discourse.

In order to clarify changes in the concept and use of defamation, compare the various medieval terms that I have introduced over the last three chapters. Justinian's formulation in the code inherited by the Middle Ages leaves considerable latitude as to the form defamation takes. It can involve spoken language (verba ), written material (scriptura ), even pictures (imagines ). The Ciceronian description, well known in late-medieval France, concentrates specifically on the song (carmen ). As we discussed in chapter 6, the abusive language (flagitium ) of the song is attributed to the particular talents of poets (ingenium poetarum ). Defamation thus enters into the province of the literary arts. Augustine's commentary on Cicero underscores this link between the defamatory and the literary even further. In the City of God passage read widely in the late Middle Ages, the defama-

tory work of the poets is characterized specifically in fictive terms (conficta a poetis ). What is potentially defamatory is poetic confabulation—fiction.

It is not at all clear that medieval commentators capitalized on these various distinctions. Yet the continuing repetition of distinctions made in high-medieval commentaries signals a new preoccupation with classical arguments over the accountability of poetry. The fact that they dwell on the defamatory cantilenus (song) and libellus (little book, pamphlet) points to their concern with the opposition between the autonomy of poetic/fictive forms and the regulatory mechanisms of the law.[17] The claim for the inviolability of literary language is already visible in these terms.[18] Equally discernible, however, is the opportunity for legal recourse against defamation committed by poets.

The two poles of this argument may well remind us of today's controversy over what constitutes "free speech."[19] While such a notion is certainly foreign to the Middle Ages, there is a way in which the confrontation between Chartier's Excusacioun and the Response raises the question of what is "free" language and what is actionable, injurious language. Both debates, the contemporary and the medieval, revolve around the principle of words as harmful. And in the process, they both come up against that most hallowed version of free speech: literature. The problem lies in establishing whether the particular character of the literary or the fictive renders it inviolable and safe from any public action. In one version of the contemporary debate, the feminist legal theorist Catharine A. MacKinnon has argued for the need to elaborate anew the principle of verbal injury in relation to various sacrosanct categories of "free speech."[20] To do so offers one way to establish legal grounds that would enable women to sue the "free speech" of others that proves offensive to them. The fierce opposition mounted against MacKinnon's argument gives us an indication of just how entrenched the notion of an inviolable language is in contemporary jurisprudence. In the debate as the Querelle de la Belle Dame rehearses it, such a notion is only beginning to take shape. The Response runs up against an early version of the argument for making certain types of language free from legal action. It contends with a nascent defense of literary language as legally unactionable. In spite of their differences, when these two debates are placed side by side, they set into relief the enormous stakes involved in establishing the damage of words and proving legal liability.

As the Response lays claim to these stakes, it accentuates the problematic status of the literary. This is already evident in the scorpion image when the women remark Chartier's habit of speaking well, writing, and effacing: "tu dis le bien, tu l'escrips, tu l'effaces" (line 28). Their turn of phrase sums up the poet's self-serving vacillation. Yet there is something

further disclosed by the link between writing and effacement. In fact, if we look to one of Chartier's cameo portraits of the writing process, writing appears to constitute a form of effacement:

Et s'enfermë en chambre ou en retrait

Pour escripre plus a l'aise eta trait,

Et met une heure a faire un tout seul trait

De lettre close.

Un peu escript, puis songe et se repose,

Puis efface pour mettre une autre chose.

Le Débat des deux fortunés d'amours (lines 322–27)

And he shuts himself up in a room or in isolation so as to write more easily and at leisure. And it takes him an hour to do a single stroke of a private letter. He writes a little, then dreams and relaxes. Then he erases so to put something else.

What is on one level an astute description of the rhythms of revision points on another to the way writing can efface what it represents. The visible and the invisible, the assertion of a point and the denial: writing accommodates both these possibilities in its own characteristic white space. In critiquing the Belle Dame and the Excusacioun together, the Response is alert to this prospect. It recognizes in the notion of writing that effaces a strategy for dodging responsibility for the injuriousness of its language. If writing is capable of erasing what it represents, how can one determine verbal injury? Or to put it in terms introduced by the Response , how can anyone pinpoint defamatory writing when it relays "a double language" (line 63)?

The Response 's criteria of effacement and doubleness become all the more telling when we look at the structure of Chartier's Excusacioun . His apology is set up as an "if" clause:

Se vous ne lisez et voyez

Tout le livret premierement. . . .

(lines 123–24)

If you do not first read or look at the whole book. . . .

S'en doit tout le monde amasser

Contre moy a tort et en vain. . . .

(lines 213–14)

If everyone should gather against me wrongfully and in vain. . . .

S'ilz en ont rien dit ou escript

Par quoy je puisse estre repris. . . .

(lines 222–23)

If they have said or written anything by which I could have been accused. . . .

The Excusacioun reads like a series of conditionals culminating in one particularly audacious one: "If I dared to say or imagine that any lady was merciless, I would be a false liar, and my word injurious" (Se j'osoye dire ou songier Qu'onques dame fust despiteuse, Je seroye faulx mensongier Et ma parole injurïeuse; lines 177–180). Such an "if clause" enables the narrator to protect himself by appearing to assume the blame. Admitting to the crime of slander within brackets that stay firmly closed is his way of exonerating himself of the charge. And the form that self-exoneration takes—the "if" condition—is the classic paradigm for literary discourse. From Aristotle straight through to Wittgenstein, the literary is distinguished by its framework of double meaning, one that aligns it strucrurally (although not functionally) with the lie and the dream.[21] In Chartier's case, the Excusacioun attempts to defend the Belle Dame on the grounds not only that the figure of the cruel woman is mendacious, but also, implicitly, that as a literary object it is tenable. The heuristic parentheses of literature seek to render the Response 's accusation of defamation irrelevant, and they do so in the same terms as a dream.[22] By opening up an oneiric space between truth and falsehood where his writing becomes double, Chartier's Excusacioun tries to vindicate the Belle Dame as a literary form that cannot, by definition, defame women.

This strategy recalls Pierre Col's argument in the Querelle de la Rose concerning the distinction between poet and persona.[23] There too a space is opened up in which characters as objectionable as la Vieille are legitimized and at the same time disassociated from Jean de Meun. The hypothetical status of the persona defended by Col is another version of the "if" clause exploited by Chartier, and the rationale behind these two positions is similar: to liberate the writer from liability. While the Parisian humanists, like Chartier, understand language to carry with it the power to injure, they award poets a special dispensation from it. Such is poetic license.

Chartier, however, pushes this privilege further. He maintains:

Quant un amant est si estraint,

Comme en resverie mortelle,

Que force de mal le contraint

D'appeller sa dame crüelle,

Doit on penser qu'elle soit telle?

(lines 201–5)

When a lover is so anguished as in a fatal reverie, when the force of malaise constrains him to call his lady cruel, why should one believe she is so?

Here the emphasis has already shifted from the relation between the poet and his figures to the figures' believability. At first glance, such a standard of believability suggests the common criticism of reading à la lettre . Once again, it appears, women are deemed incapable of deciphering the figurative, let alone of detecting its presence. Chartier's respondents join the long line from Andreas Capellanus's women through Christine de Pizan who are typed as crude and naive readers. Yet by the early fifteenth century, "believability" referred less to the opposition between the letter and the figure, and hence to women readers' difficulty in navigating it, than to the idea of verisimilitude.[24] It signaled that revived classical notion central to the humanists' apologies for poetry.[25] Chartier's question, "why should one believe she is cruel?" lies somewhere on the cusp between theories of figurative writing and theories of the literary as a distinct type of writing.[26]

This transition distinguishes Chartier's part in the Querelle de la Belle Dame . The fixation on figura , invariably linked to a clerical disapprobation of fables, was subsiding. Rising in its place were the various classical theories that charted a separate and autonomous terrain for the literary. Such an orientation is not surprising. We have only to recall the early-fifteenthcentury French vogue of Boccaccio's writings on "the fervent and exquisite invention of poetry," or the Petrarchan formula of velamen figmentorum (veil of fictions).[27] As we have discovered, the Querelle de la Rose was already significantly indebted to all these new articulations of the power of poetry.[28] Yet in the Querelle de la Belle Dame , these various articulations are exploited in such a way as to assert the distinct ontological status of Chartier's poems. Moreover, this assertion serves as the ultimate legal disclaimer. Informed by the impressive repertory of apologies for poetry, Chartier aims to exculpate his writing ontologically from all liability.

Liable for Libel

This point is not lost on the Response des dames . If the women's text engages first with Chartier on the score of verbal injury, it goes on to attack the ultimate defense that his poems are only literary compositions. In other words, it takes on directly the thorny problem of their ontological status:

Tu dis moult bien, que on ne doit pas croire,

Pour cuidier toy et ton livre excuser,

Et que l'effort d'amours t'a fait recroire

De bien parler et de bon sens user.

(lines 73–76)

You say well that in order to trust you and pardon your book, one shouldn't believe it, and that the force of love made you give up on speaking well and using your good sense.

The fundamental critique is this: how can Chartier query the believability of the cruel woman persona by bracketing it literarily and make his own defense believable? Put another way, what is the difference ontologically between the Excusacioun and the Belle Dame ? Why should his readers believe in one any more than the other? Having chided them for their interpretative naïveté, how can he expect them to give credence to his Excusacioun written in an identical mode? In effect, the Response catches Chartier at the game implicit in all literary discourse. To use the women's turn of phrase, the literary "doubleness" enabling him to admit the "falsity" of his female representations in one poem need not destabilize his writing per se. Literature's double standard authorizes him to denounce his writing as duplicitous by the same means that it equips him to defend it. The paradox is that it can change ontological footing, entertaining empirical truth claims together with literary ones. Yet here is where we need to be most conscious of our own conceptions of literary discourse, as well as of our aptitude to interpret the Querelle de la Belle Dame accordingly. Whereas most readers today take such a game for granted, it was by no means a given in the early fifteenth century. Indeed, the Response des dames would not credit such an understanding, blocking the logic that allows for the Excusacioun to be "true" and the Belle Dame "false." Their text refuses to accord ontological autonomy to Chartier's texts as literary objects—under certain circumstances. More precisely, it rejects the notion of literary autonomy as grounds for the writer's evasion of accountability. This is not to say that the idea of the autonomous literary work escapes the Response des dames ; such a position would reinforce the common, condescending identification of women readers as literalists.[29] On the contrary, while the Response grants the particular ontology of the literary text, it repudiates it as a means of denying public, legal responsibility. According to the Response des dames , "literariness" is not a valid disclaimer, nor can it be invoked so as to have one text render null and void another. Chartier's writing is still accountable before its audiences. This is all the more so in light of the prestige of the written text and its wide public circulation.[30]

That the Response rejects the ontological argument underscores the force of its defamation charge. It is a power we can best gauge in two ways. First of all, the Response des dames meets the challenge of the Excusacioun by criminalizing the charge of defamation. It changes radically the legal process by which language injurious to women can be held accountable.

Such an action gains another dimension when we contrast it to other actions taken at the Châtelet court in Paris during this period. The causes concerning paroles injurieuses abounded.[31] They involved women and men, bourgeois and noble alike. Even corporate entities such as the University served as plaintiffs.[32] No social group in the city was excluded from this trend. Yet no matter how notoriously litigious fifteenth-century French society is taken to be, it is remarkable to consider that an expletive spoken in public could be common and sufficient grounds for legal complaint.[33] Expressions such as putain, maquerelle (slut, whore) or maquereau, ruffien (pimp, lush) could bring a defendant into court.[34] While the legal theory of defamation interpreted by canonists hinges on a far graver verbal assault, on the false imputation of a crime, the surviving record leaves open the possibility for many forms of verbal abuse.[35] So deep-seated was the understanding that abusive language is actionable that any number of citizens rose swiftly to the challenge of a slur. This phenomenon built stronger and stronger momentum, occasioning by the early sixteenth century a veritable explosion in litigation.[36] Defamation was an exemplary late-medieval cause.

Women were no strangers to this spirited legal scene. As coplaintiffs and defendants, they were as engaged as any other group in pursuing their defamers and seeking public redress.[37] And given the frequency with which the crime of defamation was accompanied by the threat of physical attack, their taking action was not uncommon. As Christine de Pizan and the three Belle Dame respondents noted, when injurious language is hurled at women, it frequently involves a violent follow-through. In the causes that come down to us, la femme diffamée also risks bodily abuse. Such instances by no means offer an equivalent to the charge of "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie." Nor indeed should we be looking for one. Whether a replica of the respondents' case is visible or not is irrelevant for our argument. What is significant is the surrounding circumstances that confirm the idea of citizens suing on the basis of defamation. That such an act involves a crime marks an important correlation between the Response des dames and the Parisian legal record. That it involves a crime of writing sued for by women signals the novelty of the Response , and the second powerful influence that it exercises: libel.

The Response to Alain Chartier introduces a case of defamation that we recognize today as peculiar to written and pictorial texts. And it does so in a manner that plays adroitly with the multiple, fluid meanings of the medieval term libelle . Put another way, the women's text spans a rich, semantic complex whereby libelle , that simple, all-purpose word for book, refers to writing as artifact, type of infraction, and formidable legal instrument. Exploiting this full range of meaning, it focalizes the legal

encounter between a text deemed defamatory and its aggrieved female public. Furthermore, it addresses its two chief aspects—the occurrence of defamation and the legal process for pursuing it. To elucidate the many different ways the Response realizes the term libelle , let me tease out here its various implications.[38]

One common meaning in the late-medieval context appears in the juridical expression libelle diffamatoire (defamatory writing). A straightforward translation of the Roman term libellus famosus , it denotes those instances of defamation committed in written form. And as such, it stigmatizes them as illegal.[39] This term hangs thick in the various Querelles we have considered thus far. Indeed, it was part of the juridical jargon and apparatus that stamp the writings of almost every Parisian intellectual at the time.[40] A few examples are in order. In Jean LeFèvre's Livre de leesce , the narrator converted to the cause of women labels all clerical texts after Matheolus "libelles diffamatoires" (line 3522). In the controversy over Jean de Meun's Roman de la rose , Jean Gerson inveighs similarly against such works:

Aucun escripra libelles diffamatoires d'une personne, soit de petit estat ou non—soit neis mauvaise—, et soit par personnaige: les drois jugent ung tel estre a pugnir et infame. Et donques que doivent dire les lois et vous, dame Justice, non pas d'ung libelle, mais d'ung grant livre plain de toutes infamacions, non pas seulement contre homes, mais contre Dieu et tous sains et saintes qui ainment vertus?

(Hicks, 72, xxiii)

Anyone who writes defamatory books of a person, whether of mean estate or not, whether not at all bad, whether through another character: the laws judge such a person infamous and worthy of punishment. And thus, what should the laws, and you, lady Justice, say about not just a small book [libelle ], but a huge book full of all sorts of vituperations, directed not only against men, but against God and all saintly men and women who love virtue?

And in the statutes of the Cour Amoureuse , that stylized Parisian Court of Love devised by Parisian courtiers, the following article is included: "All that is said is, whatever accursed delinquent who will have composed personally defamatory books or have had them made by one or others will be under pain of having his arms stripped" (Tout ce que dit est, sur peine de effacier les armes de tel maleureux delinquant qui telz libelles diffamatoires aroit fait en sa personne ou fait faire par autres, .I. ou pluseurs).[41] All three examples use the expression libelles diffamatoires as a way of pointing the finger at works judged abusive of women. Whether they situate those works in a clerical or courtly context, whether they denounce them

as a type of intellectual fantasm, in the case of LeFèvre, or as a debasement of chivalric ideals, in the Cour , or even as a threat to religious orthodoxy, in Gerson, the understanding of injurious writing remains much the same. Naming works libelles diffamatoires serves as a convenient derogatory label. It identifies them as publicly unacceptable and actionable within a classical and medieval rhetoric of liability. And because Gerson sets up an allegory of a court of justice, the specifically legal dimensions of the term are accentuated.

So far the Response des dames appears to abide by a common understanding of libelle . It is structurally consistent with LeFèvre's and Gerson's use, for it too singles out the existence of such damaging, misogynistic writing to condemn it. Functionally, however, in a text voiced by three women there is a profound difference distinguishing the Response 's naming of libelles diffamatoires . The Response des dames breaks out of the vicious circle of idolatry that fetishizes a female reputation the better to control it. It suggests other modus operandi that bespeak an alliance between women and the law. It moves beyond stigmatizing the defamatory writing ritualistically in a manner that has no bearing on the parties involved. For "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie" to identify such libelles is to represent a legal inquiry initiated by the women personally affected.

Here is where a second, major inference of the medieval term libelle enters in. It is important to remember that the Latin word for book was adapted during the earliest phases of Western jurisprudence to designate the writ publicizing an allegation.[42] It is the brief bearing a charge that would ultimately serve as an indictment. By definition a public document, the libelle brought an infraction out into the open and through the intervention of a magistrate gave it technical weight. Such is the predominant sense of the word as it emerges in the juridical lexicon of Old French. In the thirteenth-century Coutumes de Beauvaisis , Philippe de Beaumanoir offers this account:

Et pour ce, de ce qui plus souvent est dit en la court laie et dont plus grans mestiers est, nous traiterons en cest chapitre en tel maniere que li lai le puissent entendre. C'est assavoir des demandes qui sont fetes et que l'en puet et doit fere en court laie, lesqueus demandes li clerc apelent libelles ; et autant vaut demande comme libelle.[43]

And for this reason, we will discuss in this chapter, in such a way that laymen can understand it, what is most often said in secular courts and what is most needful. This is concerning complaints which are made and which you can and should make in secular courts, which complaints are called by the clerks libelles ; and a complaint is the same as a brief.[44]

Such a usage carries over into late-medieval parlance. So widely accepted is this connotation that it occurs even in satires of legal process. In the fifteenth-century Farce du maître Pathelin , the lawyer's blusterings make this clear: "How the tricky man toils long and hard over presenting his complaint!" (Comme le meschant homme forge de loing, pour fournir son libelle!" lines 1273–74).

The Response des dames thus delivers a libelle (legal brief) against the libelle diffamatoire (defamatory writing) of Chattier. It throws the book at the Belle Dame . Having challenged the writing formally, it realizes the next, crucial step whereby the women as plaintiffs accuse it legally—on their own account—of libel. The Response works to establish the liability of Chartier's poem and binds it to the legal requirement of ensuing investigation. Once a brief is lodged, the chances for evasions are severely restricted. Whether that brief is eventually upheld or dismissed, it has defined the crime of writing against which all further proceeding must be measured.

As a libelle , a little legal book, the women's Response also circulates oppositionally in the space of the city. Where Matheolus sends off the misogynistic Lamentations with an Ovidian envoi—"va t'en, petit livre, va t'en en la cité"—here the respondents are quick to launch their own libelle publicly. They promulgate it as a court order against another defamatory text in the civic domain that it appears to dominate.[45] The Response thereby claims its own place in the public square, just as it does in the civic discourse so prized by fifteenth-century clerical writers and humanists.

Libel, legal brief, little book: I have followed all the resonances of the medieval term libelle , including echoes with the English word "libel." These are echoes, let me emphasize, that hold neither in Old nor modern French. Libelle is not used, strictly speaking, to juridically designate a crime. But I have entertained this word play because it enables us to reach the heart of the Response des dames ' challenge. The libelle represented by this work recapitulates a wide and revealing semantic range that covers the literal meaning of written material, the extended meaning of defamatory writing, as well as the stiff, technical sense of a legal writ. The singular action this narrative takes capitalizes on the malleable and charged concept of defamation in the late Middle Ages, and it does so in a manner suggesting its particular advantage for women. Articulated in their voice, libelle —in all its senses—is not invoked lightly or hypothetically. It is performed by female personae who are not proxies but are themselves the plaintiffs. It becomes their legal instrument.

The Response des dames's libelle is shot through with a lurid language. There are notable allusions to hanging and burning, references to recanting

and the public disgrace of infamy (lines 6–8, 45–48).[46] The Response even types Chartier a heretic, much as Christine did with Matheolus and Jean de Meun (line 78).[47] Such a rhetoric resonates with the turbulence reigning in early-fifteenth-century Paris. Given the charged political tensions, the threats concerning heresy proliferated, and in an ecclesiastical context these could result in the rituals of book burning and execution.[48] The profound belief in verbal injury coupled with a fear of social chaos frequently sanctioned a violent end for the heretic and his works.[49] Mimicking details of these rituals, the Response participates in the inflammatory atmosphere of the times.

By the same token, this extremist language is a defining element of polemical logic. As we discovered with the Querelle de la Rose , it is the gesture of challenge and disputation. No point is made neutrally, nor are its consequences underplayed. In the case of the Response , this language full of menace also points to the particular force of its polemic. It underscores the seriousness of its legal charge. Here again is the idiom of absolutist power, which enables women respondents to exert rhetorical influence they would not otherwise possess.

But it does not convey the spirit of the public redress the Response des dames seeks. For one thing, it does not presume to ban Chartier's writing. In delivering the brief, the respondents maintain: "For you write as you shall want to write" (Or escrips ce que escripre vouldras, line 80). At some level, they acknowledge the incorrigible continuity of poetic composition, its boundlessness. Insofar as the Response makes no claim to prohibit Chartier from writing, its libelle motion does not carry with it any program of enforcing textual conformity. After all, it challenges a text that, however politically precarious, remains the paragon of poetic orthodoxy. Its ambition is to explode such orthodoxy. Its chief concern lies in the harmful consequences of a dominant mode of representation. It seeks to adjudicate those consequences to the satisfaction of the aggrieved parties involved without eliminating the writing outright.

So it is that the Response accentuates the open-endedness of its litigation. Any libelle is caught in the rounds of charge and countercharge, and the Response is no exception. It anticipates a later stage, where Chartier would be confronted with the respondents' advocates (lines 101–4).[50] In its conclusion it promises an ongoing exchange between the women plaintiffs and the poet. Such an exchange would entail not only negotiation but further writing. To issue a libelle against a crime of writing, let me repeat again, occasions more and more text, a prospect in perfect keeping with the Response 's purposes. In the attempt to reconcile injurious textual representation and offended parties, the prerogative to write is by no means destroyed. Nevertheless, the libelle for libel still stands. The peculiar, novel

power of the women's Response resides in its legal action that confronts a writer with his public.

A Matter of Fiction and Treason

That the Querelle continued after the Response des dames suggests the strong impact of its libelle . In the decade following the Belle Dame , five other works appeared that sought to undo the charge of defamatory libel levied against Chartier.[51] At the center of these works is an interrogation of the Belle Dame persona. She is put on trial—over and over again. Such a scene enables these works to answer the Response's libelle : it makes the literary character and not the writer accountable. Yet it also discloses the ongoing struggle with the defining issues of the Querelle : the writer's liability for verbal injury and the ontological standing of his book. As we shall see in the two following examples, the poets in Chartier's circle experimented obsessively with deflecting the charge of defamation. This experimentation hints at the tensions remaining over the writer's responsibility and the sovereignty of his literary text. It discloses frustration over the fact that these questions are unresolved or unresolvable. To what degree this exasperation is vented on the women respondents should become clear.

In the trial of the Belle Dame mounted by the poem La Cruelle Femme d'amour , the issue of Chartier's liability is met head-on. When the allegorical figure Truth is called as a witness to vouch for the woman, she balks, stating:

Celle qui se mist en mon nom

Pour ceste cause soustenir

Ne fu aultre que Fiction:

Poeterie la fist venir

Et ma semblable devenir;

Et se transmua Faulseté

Pour sa trahison parfurnir

En la semblance Leauté.

(lines 329–36)

The one who took my name to support this cause was none other than Fiction. Poetry made her come and become like me. And Falsehood changed herself into a semblance of Loyalty to accomplish her treason.

The Cruelle Femme supplies the missing component that hovers over the entire Querelle : Fiction. On first glance, Fiction appears to be the standin for Truth, and a fraudulent one at that. The chief alliance thus unites Fiction, Falsehood, and the Belle Dame . Yet given the Cruelle Femme 's intricate allegory, which sets the courtroom scene within several dream

frames, we must interpret this configuration carefully. Although the humanist understanding of poetry is invoked pejoratively here—that is, to distinguish a false portrait of a woman from a true one—it serves to valorize Chartier's text. Fiction functions here in her tantalizing duality: as falsehood and as distinct discursive mode. She recoups the standard clerical disapproval of deceptive fiction together with the emancipatory concept of fiction as the highest exaltation of truth. Indeed, she plays one off against the other. Consequently, the Cruelle Femme can accommodate the charge of defamatory representation, appearing to appease the women respondents in the very act of marking out a separate sphere for the fictive. By admitting that Chartier's Belle Dame is cruel and not even a lady, La Cruelle Femme en amour appears to credit the Response 's charge. It entertains the poet's liability. Yet by making that admission through Fiction, transformed now into a positive, potent term, it checks that liability from ever being established legally. What we most commonly think of as an early modern concept of fictionality is introduced here as a means of making the Belle Dame legally inviolable. The Cruelle Femme defends Chartier's poem on ontological grounds.

We have here the most explicit and technical reply to the claims of verbal injury in the Response des dames . The Cruelle Femme explicitly names a principle already apparent in the Querelle de la Rose and prominent in Chartier's Excusacioun . The double epithet it thus introduces—Poetry/Fiction—places the notion of a literary ontology squarely in the technical vocabulary of a philosophical debate that is more or less foreign to Chartier's own work.[52] Furthermore, the pronounced legal frame brings out the often-overlooked fact that Fiction also represents a juristic formula.[53]Fictio figura veritatis was at the center of several canon legal debates during the late Middle Ages.[54] As a concept in the Cruelle Femme , then, Fiction commands particular influence, benefiting from a specifically legal meaning as well as from a poetico-philosophical one.

Reinforced doubly, the ontological vindication of fiction would appear to win the day. In a shrewd move, one legal premise of fictio figura veritatis blocks another—the Response 's claim of laesio/iniuria . Yet if we note the subsequent development in the Cruelle Femme , this is far from the case.[55] No matter how strongly the case for fiction's sovereignty has been propounded, there lingers the suspicion that it does not completely nullify the Response 's legal claims. In some fundamental way, the criterion of an autonomous literary object fails to dispense with the issue of accountability for damages. This failure has less to do with the irregular currency of the Poetry/Fiction theory in fifteenth-century France than it does with the uneasy fit between the theory and the legal doctrine of defamatory writing. Once again we discern the irreconcilability of literature and libel at this particular

historical moment. It prompts still more exaggerated defenses of Chartier.

In the wake of Fiction's mock denunciation of the Belle Dame persona, the Cruelle Femme represents her as convicted of the most heinous crime. The God of Love pronounces that she has committed lèse-majesté—an infraction for which she is to lose her own proper name (lines 747–52). To find the Belle Dame guilty of treason is to throw one last sop in the direction of the women respondents. Condemning the literary persona is meant ultimately to appease them. Yet this "condemnation" also signals the frustration of Chartier's defenders over the sheer intractability of the liability question. The more numerous the arguments for the fictive text's unaccountability, the more unavoidable a text's responsibility to its community appears. The more sophisticated those arguments, including even the "Fiction as Poetry" theorem, the more unyielding the question of verbal injury remains. Let us not forget that the crime of treason, "lèse-majesté," is itself formulated as a wounding (lèse ) perpetrated through words: "de sa bouche a arresté."[56] The final recourse left to Chartier's defenders involves recasting the charge of verbal injury and foisting it back onto those who raised it.

Here is where we can detect that the ultimate object of the Cruelle Femme 's accusation of treason is "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie." According to this poem, the Response des dames dared to attack the work of a royal poet. As many critics have suggested, late-medieval intellectuals were deeply preoccupied with treason and the damage done to sovereignty—so preoccupied, in fact, that the problem was easily transferable.[57] Any number of social phenomena were associated with treason. It is in this sense that Jean de Montreuil attempts first to interpret Christine de Pizan's critique of the Rose as an attack on the integrity of the master.[58] And it is in this sense too, that Chartier's defenders use the charge of treason to accuse the respondents implicitly of another form of injuriousness. By introducing the crime of lèse-majesté, they turn the tables on the Response des dames and thereby try to exit the intractable Querelle over liability with the law on their side.

Such a gesture should be familiar by now. Targeting "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie" in this manner reconfirms the stereotype of women as defamers. To characterize them as treasonous is another way of defining their own language as inherently damaging and dangerous. Indeed, it casts their language as nothing less than demonic.[59] As Le Jugement du povre triste amant banny , another poem in Chartier's defense, appraises it, women's defamation holds dire consequences for the entire body politic: "For when they want to attempt to be hurtful, everyone is devastated" (Car quant vouldroient tascher a nuyre, / Tout le monde seroit gasté; lines 831–32).

This ploy of labeling the women treasonous and by implication defamatory was intended to shift the focus of the Querelle away from the outstanding problem of the poet's legal liability for his writing. Rhetorically, it may well have worked. The controversy seems to have trailed off at this stage. Yet that it comes to the point of invoking the gravest crime against women is revealing, for it suggests the disturbing power the Response des dames as libelle could have exercised.

What, then, are the consequences of the Response des dames ? The inconclusiveness of the Querelle around Alain Chartier's writing should not fool us into concluding that there were none or that the consequences were ineffectual. However short-lived the incident, it represents an important step toward legal recourse. In fact, it appropriates legal recourse as a mechanism with which to combat the symbolic domination of women through a masterly poetic discourse. It manipulates the prevailing laws of defamation in such a way as to stigmatize the individual writer involved and to put his writing—symbolically—in the dock. Given how influential the legal regulation and rhetoric of defamation was in fifteenth-century France, the Response 's deft play with the law proves all the more provocative. It is, let me underline, first and foremost a form of play. It does not substantiate a case of three women plaintiffs suing for damages. But exploiting ludically the legal apparatus concerning defamation does elicit other strategies for challenging publicly the dominant representation of women. This, as the Response suggests in jest, is in the unlikely event that their words will come to blows: "For it will never happen that woman will fight you" (Car point n'affiert que femme t'en combatte; line 88).

To play with the power of the law was by no means the principal strategy available to the woman's response. As we have seen in the previous chapter with Christine de Pizan, there was always the possibility of assuming the symbolic register of the masterly poetic discourse on women and thereby disputing the problem of its domination on its own grounds. The woman's response could generate its own brand of symbolic structures, sometimes in notably learned form. In the terms of the Querelle de la Belle Dame , it can co-opt the fictive for its own purposes. This is something that Christine de Pizan also demonstrates ably when she claims: "I shall say, through fiction, the fact of this transformation, how it was I became a man from a woman."[60] But what distinguishes this Response des dames is its complementary choice of exploring a legal option. In the wake of the experiments legitimated by the Querelle de la Rose , the Response confronts fiction with the law. To mimic filing a libelle for defamation provides another formidable means of disputing the symbolic domination of

women. For it charts a space between the absolute, unqualified freedom of discourse and arbitrary censorship, between bearing no responsibility whatsoever to the public and being utterly beholden to the prevailing authority. In this sense, it pioneers a middle ground made possible through litigation, a ground where the underrepresented can render public the time-honored recurrence of verbal injury to women and seek compensation. In the most far-reaching sense, such compensation would not comprise an empirical computation of damages. Rather, it promises the practice of changing the masterly discourse on women. It involves forging another discourse, shaping other images of women that would not prove so confining. To make over Chartier's own expression, it would launch a freer figuration of women. I risk this formulation on the basis of an image in the Response des dames :

Tu trouveras et le verras au fort

Que leaulté, doulceur, bonté, franchise,

Portent la clef du chastel ferme et fort

Ou honneur a nostre pitié soubzmise.

(lines 53–56)

You will find and you will see well that loyalty, gentleness, goodness, freedom, carry the key to the strong and stout castle where honor yields to our mercy.

Always in the terms of the prevailing symbolic language, the Response forecasts a moment when franchise (freedom) would typify women. And this would provide "the key to the castle"; that is, according to the trope of woman as castle, it would legitimize a different code of representing women, unlocking them from the decorous yet tyrannical one that holds them. Such a key has no single owner. This passage can be read as referring to Chartier and the existing cadre of court poets or to women as purveyors of discourse. Whichever the case, the discursive stronghold can be broken through, replaced by a discursive model that figures women more freely. Such a figurative prospect is still framed here by other symbolic structures that are less than favorable to women: the catalogue of feminine virtues, the code of honor, and the posture of the idol. But that is why it is projected in the future tense; that is also why it is couched in an enigma—la clef —a common password for outmaneuvering hostile readers.[61] If a freer figuration of women is presented so enigmatically, it is because it is far from being realized. If it is alluded to at all, it is because in this highly divisive, highly sophisticated milieu of fifteenth-century Paris, it is nonetheless conceivable.

14. Héloïse instructing courtiers in Capellanus's lessons on love.

London, British Museum, Royal 16.F.11, fol. 137.

By permission of the British Library.