12

The Pre-Columbian Survivals

The Masks of the Tigre

O jaguar, most noble, slyest of all the beasts of ancient Mesoamerica, deified for thousands of years by the Olmecs and Zapotecs, by the peoples of Teotihuacán, Tula, and Mexico-Tenochtitlán: fight on wildly in the fray; die on a thousand times in our village fiestas.[1]

The jaguar—as a symbol of the earth, rain, and fertility—did not die with the Conquest but ironically continues to die every year in the festivals in and through which the indigenous folk religion of Mesoamerica exists. This annual death is, as it always has been, representative of the death that precedes rebirth in the eternal cycle of life and death. Thus, the jaguar mask central to the widespread Danza del Tigre in its many variations (to which Fernando Horcasitas refers) provides the best example of the survival of the mask and its underlying assumptions in indigenous ritual. What Gibson says of pre-Columbian survivals generally—that while a continuity of existence from pre-Columbian times is difficult to demonstrate, "it may be assumed that the pagan components of modern Indian religions have survived in an unbroken tradition to the present day"[2] —is specifically true of today's jaguar mask and its accompanying ritual; without exception, scholars accept Horcasitas's contention that "from all indications, la Danza del Tigre has pre-Hispanic roots."[3]

The earliest evidence we have for the existence of the mask and the dance, while colonial, strongly suggests their pre-Columbian origin. In 1631, the Inquisition prohibited the Danza del Tigre in Tamulte, Tabasco, since "it contained hidden idolatry offensive to our Religion." Specifically, dancers "disguised as tigres " fought, captured, and simulated the sacrifice of a dancer dressed as a warrior in "a cave called Cantepec"; the simulated sacrifice was followed by an actual sacrifice of hens.[4] On the basis of this and other evidence, Carlos Navarrete concludes that "popular 'animal dances' [often] concealed ancient pagan rites."[5] That those rites in this case are involved with the provision of water from the world of the spirit is demonstrated by the ritual's familiar combination of thematic motifs. The union of blood sacrifice, the cave, and a human being disguised as a jaguar (tigre , in the context of indigenous ritual, means, and is generally translated as, jaguar) in this ritual configuration recalls the pre-Columbian rain gods and their ritual propitiation at the time of the coming of the rains. The central position of the jaguar mask makes the connection clear; and that colonial mask was the forerunner of the numerous jaguar masks worn today, 350 years later, masks which are visually reminiscent of their pre-Columbian predecessors.

The modern mask, in most of its variations, generally displays the features of the pre-Columbian, jaguar-derived rain god masks—prominent fangs, a pug nose, round eyes with prominent eyebrows, and often a large, though not bifid, tongue dangling from its mouth. In many cases, the wearer looks out of the mask through the open mouth,[6] an unusual arrangement in modern masks but one reminiscent of pre-Columbian practice. Thus, both the earliest evidence of tigre mask ritual and the appearance of the masks themselves suggest a pre-Columbian origin.

Probably the most widespread and surely the best-documented ritual dance-drama is the Danza de los Tecuanes found primarily in the central Mexican states of Guerrero and Morelos.[7] It recounts "the hunting and killing of a tecuani or jaguar" who has devastated the local village. The version detailed by Horcasitas in 1979 begins with the wealthy landowner, Salvadortzin, and his assistant recruiting hunters, among them an archer, a tracker, and Juan Tirador, the marksman who will

finally shoot the jaguar. Once they are recruited, Salvadortzin gives them their charge:

Viejo Rastrero! Old Tracker! I want you to hunt and kill the tiger because the tiger's been doing a lot of damage. The tiger's ruined seven villages, the tiger's destroyed seven hamlets, the tiger's finished off all the good cows, the tiger's eaten up all the good donkeys, the tiger's eaten up all the good bulls, it's eaten up all the good goats, it's eaten up all the good sheep. It's even devoured all the good girls who go to the well for water, man! I'll pay you well to go get the tiger, man![8]

In a similar speech delivered by Don Salvador to his mayordomo in the version of Texcaltitlán in the state of Mexico, the landowner says the tigre is consuming the yearling bulls, the calves, the lambs, the kids, the piglets, and the rabbits, to which the mayordomo responds, "We are going to die of hunger."[9] Thus, the wild animal, the jaguar, is destroying the domesticated animals that support human culture by providing food in an orderly and regular manner and is serving here the same structural function it had in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica from the time of the Olmecs; it is still generally symbolic of the untamed forces of nature that must be brought into harmony with the order underlying human society.

And it is through the accoutrements of human society that that order is achieved. Salvadortzin questions Juan Tirador, who will kill the jaguar, about his looks and then about his weapons:

"Juan Tirador, they tell me that you are brave. They tell me you are a good hunter. Is it true that you have a strong heart? Is it true that you have a big mustache? Is it true that you have a bushy beard? Is it true that you are handsome and have rosy cheeks?" All this is in reference to Juan's wooden mask. To each of these questions he answers "Yes, yes. True, true." "Is it true you have good weapons?" Juan Tirador then describes his hunting equipment, which is that of a small army: traps, cords, pistols, shotguns, munitions, rifles, muskets, bullets, cartridges, machetes, knives, daggers and so forth.[10]

The answers seem deliberately designed to point up the difference between the "natural" mask and claws of the jaguar and the "civilized" mask and weapons of the hunter and thus reiterate the opposition of nature to culture suggested by the destruction of the domesticated animals by the wild jaguar. And this theme is found in other details of the dance-drama. Much is made, for example, of the wealth of the landowner and the paying of Juan Tirador, a motif emphasizing the social structure in opposition to the natural behavior of the jaguar: the hunter kills as a profession, the jaguar as an expression of his being. The emphasis on the dogs used by the tracker suggests the theme of domestication in another way: domesticated animals can be used to subdue wild animals as well as be destroyed by them. And the final skinning of the jaguar to make various items of clothing for the hunters and the dogs demonstrates that nature is not only potentially destructive but can also be useful to human society when brought under control. It is fair to say that the drama turns on the underlying opposition between nature and culture and in the killing of the jaguar, illustrates the necessity of "domesticating" wild nature.

The final speech of the variant enacted at Tlamacazapa, Guerrero is fascinating in this regard:

"But wait, Juan Tirador," shouts the Governor. "The jaguar is so big that I will give you a piece of skin for your coat, for your vest, for your belt, for your shirt, for your pants, for your leather jacket, for your chaps, for your trousers, for your leggings, for the case for your weapons. Even for the shoes of your puppies! Even for your mask, man!"[11]

The dead jaguar (a human being wearing a mask) thus becomes a mask for the hunter in a startling switch ending the dance and making clear both the sophistication of this tradition of mask use and the awareness within the drama of the metaphoric nature of the mask, for the shoes for the puppies and the mask, the last of the items enumerated, are the only items not part of everyday life outside the drama; what was formerly wild can be used to support culture and in that use becomes a "mask" to cover the inherent "wildness" of all life. That this theme should exist in a dance-drama whose central character wears the mask of a tigre, or jaguar, indicates clearly that the symbolic merging of man and jaguar in the were-jaguar masks of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica continues, albeit in altered form, and that the were-jaguar still stands as a metaphor for the sustenance of man by the world of the spirit through the fertility of nature.

While the dance-drama of los Tecuanes lacks most of the earth and fertility symbolism associated with that pre-Columbian were-jaguar, a closely related variant in which essentially similar masks are employed retains that symbolism, as its name, los Tlacololeros , suggests. The name is derived from tlacolotl , Nahuatl for a plot of land,[12] and the dance "dramatizes the efforts of men to cultivate their fields and their struggle against the tiger that ambushes them and threatens to destroy their human labor."[13] The two dance-dramas seem to have divided the two forms of domestication characteristic of agricultural life—that of animals and the land—into two separate, but clearly related, dances that coexist in the state of Guerrero; perhaps the single colonial source of these modern variants[14] united the two forms of domestication.

While los Tecuanes is almost wholly involved with animals, los Tlacololeros deals with the agricultural cycle. As the drama begins, the jaguar

taunts the spectators while the ten or twelve tlacololeros, all similarly dressed and masked and each named after a particular plant, prepare a plot of land and plant a seed, after which they complain to the chief of the hunters of the jaguar who threatens their agricultural efforts. In response to these complaints, the chief uses a dog, la Perra Maravilla , to track the jaguar, and when he is brought to bay, often in a tree, the chief finally kills him. After the hunt, as in los Tecuanes, there is a good deal of discussion of the size of the jaguar. The tlacololeros then burn the plot of land in preparation for the next planting. While the land is burning, pairs of dancers whip each other, often violently, on their padded costumes, the sounds of the whips simulating the sound of the fire. Often a clownlike character carries a dessicated squirrel with which he torments the other characters and the audience.[15] Thus, all the elements of the cycle of life, especially as it applies to agriculture, are here, and the theme of life coming from death with its complementary notion of the necessity of the sacrifice of life is clearly evident. Often, though not always, los Talcololeros is presented as a part of rain-petitioning ceremonies,[16] providing yet another link to the agricultural cycle and to the were-jaguar mask of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

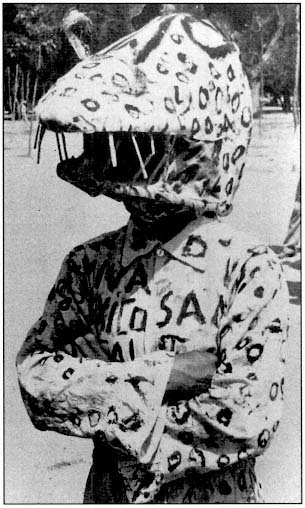

Pl. 63.

Mask of a Tigre, Guerrero. The wearer of the mask

may be seen through the mask's mouth.

Pl. 64.

Masked Tigre, Dance of the Tecuanes, Texcaltitlán,

State of Mexico (reproduced with the permission of FONADAN).

The tigre masks employed in the dances of Guerrero and Morelos range from carved and lacquered wood masks (pl. 63), often magnificent creations, to mask helmets made by covering a reed or wire frame with painted cloth (pl. 64).[17] Different as the masks are, however, their common origin can be seen in their remarkably similar, though differently interpreted, features. Always, for obvious reasons, the mouth is the focus of attention. Large and generally fanged, it often has a protruding tongue and sometimes provides the opening through which the wearer sees. In such cases, the face of the wearer can be seen within the mask exactly as the opossum mask helmet from Monte Albán (pl. 34) symbolically revealed its wearer within. The nose of the tigre mask is generally a feline pug nose, and the eyes are often distinctly circular and goggle shaped, though not always. The masks generally bristle with clumps of hair, eyebrows, and mustaches of hog or boar hair and are usually painted yellow with black spots. The masks comprised of these features range from relatively realistic portrayals of the jaguar to highly stylized ones, but they all emphasize at least some of the features we have seen in the jaguar-derived pre-Columbian rain gods from the Olmec were-jaguar[18] to the Oaxacan Cocijo, the Tlaloc of central Mexico, and the Maya Chac.

Although there is some regional variation, masks essentially similar to these represent the jaguar in ritual throughout Mesoamerica, and other elements of los Tecuanes and los Tlacololeros consistently appear along with the familiar mask.

First, the tigre seems always to be accompanied by boisterous, generally sexually based humor. At times, the jaguar interacts with the spectators, teasing and taunting them; at times, the performance includes a ritual clown, often carrying a stuffed animal, who engages in sexual foolery; and at other times, the various characters within the drama involve themselves in similar antics. Whatever form it takes, however, there is always humor. As Horcasitas puts it, "The dance is a comedy, yet it would show disrespect to omit it from the village fiesta. It is holy and funny. Religious feeling here is expressed in merriment, not in gloom."[19] That the dances are thought of as religious is indicated by their being preceded and concluded by specifically religious ritual and by their often being presented in the courtyard of the church. But the generally sexual nature of the humor is obviously related to the fertility theme of the ritual drama and is remarkably compatible with its basic nature/culture opposition as it suggests that human sexual proclivities must be controlled for culture to exist. In this connection, it is significant that male participants are generally required to observe a period of sexual abstinence that provides the opposite extreme from the wild sexuality of the humorous elements of the drama. The message is clear: normal human life within a culture is characterized by what the culture defines as normal sexual activity—neither the abstinence of the ritualist nor the wild abandon of the tigre and other characters.

Along with the humor that functions in the context of the nature-versus-culture oppositions, the tigre performances of modern Mesoamerica almost always involve a series of up/down oppositions. In the version just described, the jaguar climbs a tree where he is finally killed. Other versions are more spectacular; in a variant performed at Texcaltitlán, Guerrero, for example, the jaguar first climbs a tree in an attempt to escape the hunters and then climbs a rope extending from that tree to the top of the nearby church tower.[20] Conversely, the tigre is often involved with caves. These up/ down and in/out oppositions seem clearly related to pre-Columbian pyramid/mountain and temple/ cave ritual and assumptions, especially since the summits of mountains and the inner reaches of caves, as we have seen, were intimately associated in myth and ritual with the provision of rain by the gods. Significantly, the tigres are often involved with church towers, that is, contemporary, religiously defined "summits."

The tigre dances also share a fundamental involvement with violence. The central character, the jaguar, is violent in his destruction of other characters and is finally disposed of violently, and dramatic violence often occurs between the other characters. Moreover, the violence within the drama often provokes very real violence among the spectators. Because of the large amounts of alcohol consumed by festival participants and the emotions aroused by the dance-drama, real blood is often shed and, not infrequently, participants are killed. But this is expected and, in a strange way, seen as desirable. Véronique Flanet, in discussing the festivals in the Mixteca, says that a fiesta is not deemed successful if no one has been killed. She quotes typical remarks: "Last year's festival was much better; there were seven people killed," or "When no one is killed, there is nothing worth mentioning about a fiesta."[21] This emphasis on, and expectation of, bloodshed and violent death—both within the ritual performances and without—may seem barbaric to us and to the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of modern Mexico, but as an integral part of the ritual fertility festivities, it reflects the fundamental connection in the Mesoamerican mind between sacrifice and fertility. Seen in this way, it is in perfect accord with other modern practices and assumptions with the same pre-Columbian roots. One thinks, for example, of the penitentes throughout Mesoamerica and the bloody depictions of Christ in indigenous art.

While a number of other ritual dances involve tigre-masked characters, none demonstrates the characteristics connected to the pre-Columbian past more clearly than the combat of tigres enacted on May 2, el dia de la Santa Cruz , at Zitlala, Guerrero. To call this a ritual combat between members of opposing barrios should not suggest that it is in any sense a mock combat; the fighters "trade blows until they are gravely wounded."[22] The practical function of the leather mask helmet (colorplate 12) is to protect the wearer's head from the blows delivered by his opponent's rope-covered cudgel, but the nature of the mask and cudgel indicates their pre-Hispanic origin and the pre-Columbian roots of the ritual. Formed of a single piece of heavy leather folded at the top with the sides laced together,[23] the mask helmet completely covers the wearer's head down to the nape of his neck. Protruding from the top, at the ends of the fold, are prominent ears, and a nose formed of a rolled piece of leather divides the front of the mask from the top to just above the mouth. On either side of the nose are the eyes made of mirrors or tin and outlined with remarkably gogglelike circles of leather. The lower part of the mask is dominated by the oval mouth that the wearer sees through which is also formed of leather and contains leather teeth and a prominently protruding tongue. The front of the mask bristles with clumps of inserted hog or boar hair, and the whole construction is painted either yellow or green and spotted with small black circles.[24] While its overall appearance is quite different from the masks used in los Tecuanes and los Tlacololeros, its individual features are remarkably similar, a fact suggesting a common source from which the varied masks evolved. The cudgel wielded by this masked combatant is a length of

stiffened rope wound at the end with more rope to form what has proved at times to be a lethal weapon, a weapon reminiscent of the pre-Columbian macuahuitl used by Aztec warriors.[25]

The description of the mask suggests its close relationship to the jaguar-derived, pre-Columbian rain gods, especially Tlaloc. Most reminiscent of the Aztec god, of course, are the goggle eyes, but the nose, too, is very close in appearance to the nose formed of twined serpents often seen on Aztec images of the god. The mouth looks like the Tlaloc mouth with the upper and lower lips meeting to form an oval, and the protruding tongue, while not bifid, suggests those commonly found on masks of the rain god. It is perhaps significant to an understanding of both the pre-Columbian masks and this one that the serpent-related characteristics of the rain god mask, possibly excepting the nose, added by the inheritors of the Olmec were-jaguar have disappeared.

And the substance of the ritual as well as the appearance of its participants has pre-Columbian roots. As both Cruz Suárez Jácome and Roberto Williams Garcia point out, the combat is an integral part of the ritual activities of the second of May, activities whose primary purpose "is to entreat the aires to send beneficent rains and abundant harvests." These aires are, like the pre-Columbian rain gods, quadripartite in nature with directional, color, and bird symbolism. The ritual "should be interpreted as propitiating the aires in general, and in particular entreating the aires of the East to deliver the beneficent rains and discouraging the aires of the North from sending hail, frost, and destructive rain." Significantly, the ritual is performed at roughly the same time as the Aztec festival of Huey Tozoztli dedicated to Tlaloc and serving a similar purpose.[26]

An understanding of these similarities between the modern festival and its pre-Columbian forerunner allows the full import of the comments of participants in and viewers of the combat to emerge. José Colasillo, an elder of the village of Zitlala, said that the combatants must fight as "a sacrifice for rain." Another member of the community made the idea even more explicit: "If we do not do this, God will not see the necessity to send the sacred waters." And another said, "Without our tiger fights, the sun might not rise, and the rains might not come. We must sacrifice with all our hearts."[27] These words suggest the human reality of Suárez Jácome's contention that the combat, as a necessary sacrifice, gives the rain-petitioning ceremonies greater force.[28] Thus, the pre-Columbian formulation equating blood with rain as the basis of a reciprocal relationship requiring man's sacrifice in return for the "sacrifice" of the gods may still be found in Zitlala. Now, of course, the Zitlaleño would say "God" rather than "the gods," but the underlying spiritual assumptions remain. As Juan Sánchez Andraka puts it, "the Aztec 'flowery war' persists"[29] and continues to provide the blood that nourishes the gods.

It is thus doubly fascinating that a portion of the rain-petitioning ritual of the second of May takes place in a cave on the Cerro Cruzco,[30] a mountain that rises above Zitlala. While that fact alone has pre-Columbian implications, this particular cave is the cave of Oxtotitlán containing the Olmec murals discussed above which has functioned as a fertility shrine at least since the time of the Olmecs a thousand years before the birth of the Christ, who gave his name to the religion now "accepted" by the people of the village. As the jaguar mask worn by the combatants makes abundantly clear, their Christianity rests on a pre-Columbian spiritual base.

But the situation is complex as these clearly pre-Columbian elements are embedded in a ritual with numerous Christian elements. In fact, May 2 is the Day of the Holy Cross, an entity that is even more important to the ritual than the tigres. "For the people of Zitlala, the cross is more than a symbol; it is a living entity, a feminine deity," and while the tigres figure importantly in the ritual, "their once-principal role has been subordinated to the cult of the cross."[31] The activities that culminate in the ritual on the Day of the Holy Cross begin in earnest on April 30 when three crosses, one for each of the barrios of Zitlala, are brought down to the river from the cave on the Cerro Cruzco. On the following day, they are "dressed" with special capes, in a manner reminiscent of pre-Conquest practice, prayed over, and decorated with offerings of candles, chickens, corn, copal, and garlands of flowers and bread. In this state, they are borne on special frames by unmarried young women on a circuitous route up from the river, through the village to the church. Along the way, the head of each household the crosses pass adds to the offerings. That night the crosses "rest" in the church while masked dances are performed outside. On the following day, the second of May, after the celebration of masses in the morning, the crosses are borne back to the river and carefully restored to their former place, now, however, without the offerings. At this point, the celebrants separate. Some carry the cross up a steep and rocky path on the Cerro Cruzco to the adoratorio while others participate in the combat of the tigres in the riverbed at the base of the mountain. Those who follow the cross engage in a complex set of activities, including the ritual sacrifice of chickens, on the mountain which results in a variety of foods to be given as offerings to the now newly "dressed" crosses.[32] Meanwhile, the tigres are rendering offerings of another sort.

The Christian elements of the festival are now more prominent than the indigenous elements, but the similarities between the two are far more fas-

cinating than their differences. Both are subordinated to the overall theme of sacrifice as an offering to the world of the spirit from whence comes life, and both involve the metaphor of the mask, a metaphor fundamental to the combat of the tigres. The combatants don the mask of the god, animate it with the force of their life, and then shed the symbol of that life-force, their blood, in voluntary combat. Thus, their blood becomes the "blood" of the gods, the rain, which enables man to live. But what is the "dressed" cross but precisely the same metaphor? By covering the cross with the things of this world, as the santos are often dressed in indigenous ritual imitative of the pre-Columbian dressing of the nude or nearly nude stone or ceramic figures we now see in museums, the cross itself becomes the inner life-force animating the clothing and giving vital force to the flowers and bread. It requires sustenance and provides sustenance. The treatment of the cross and its offerings reveals exactly the same reciprocal relationship between man and the world of the spirit as that revealed by the combat of the masked tigres.

These elements are evident in the events of the Day of the Holy Cross, but when that day is linked to its counterpart of September 10 when Zitlala celebrates the day of Saint Nicholas, they can be even better understood. Although that festival nominally celebrates the patron saint, it is actually a harvest festival.[33] The Indians of the region pay homage to the image of San Nicolás "according to the blessings received from him. When harvests have been plentiful, the shrine is visited by hundreds of the faithful."[34] Thus, the ritual of the Day of the Holy Cross in May seeks rain, fertility, and an abundant harvest, and the ritual of the Day of San Nicolás Tolentino in September gives thanks for their provision, if they have been provided. The activities surrounding that day of thanksgiving, while quite different from those of the earlier festival, are equally syncretic. And while the tigres play an important role, they do not engage in ritual combat, and the Aztec-derived cudgel with which they fight on the second of May is replaced by the teponaxtli, a cylindrically shaped pre-Columbian percussion instrument, which at least some of the villagers believe is "the voice of God, of the Celestial Jaguar, of the thunder and lightning."[35]

Sánchez Andraka describes an observer's experience of the eve of the festival vividly, if somewhat dramatically.

Fireworks shook the earth, all the bells were ringing, and the people filled the plaza and the atrium. The dance troupes began to arrive one by one. Los Moros. Los Moros Chinos. Los Diablos. Los Zopilotes. Los Vaqueros. Colacillo, the great healer of Zitlala, whose fame goes beyond the borders of the state, played the violin frenetically for Los Vaqueros. Colored lights shot into the sky and thousands of candles adorned the church. In the midst of all this, a strange sound could suddenly be heard, a sound of wood striking wood that silenced everyone and transported us to another epoch. The bells and the firecrackers ceased. Tap, tap, tap, tap. It was an imperious wooden voice that carried us beyond fear and the night. Tap, tap, tap, tap. It seemed to be the voice of a deity speaking to the people or invoking the heavenly bodies, the moon and the stars, which shone intensely this night. And then a long laugh and a yell. Everyone's eyes lifted to the church tower. Four shadows could be seen on the ledge of the first cornice. The tap tap of the teponaxtli and the laugh and the yell had come from there. Héctor shined his flashlight on them and others followed suit. The one who carried the teponaxtli over his shoulder was dressed in red with a red mask and very long hair. Another, dressed similarly but with a black mask, reverently beat the teponaxtli and continued yelling and laughing, but it was a mysterious laugh. At their sides were the impressively masked tigres—one bright yellow, the other dark yellow. They leaped from the first cornice and climbed to the second. The tap, tap, tap grew in intensity and changed in tone. Below was a profound silence. When the masked figures reached the third cornice, they were 30 meters above the ground on a ledge a scant 20 centimeters wide. From this ledge they climbed to the small cupola topped with the cross, one of them carrying the teponaxtli, the other beating it, and the tigres giving three cat-like leaps. Now the yell and the laugh were very strong. They decorated the cross with garlands of zempazúchil and then began to descend, incessantly tap, tap, tapping.[36]

At the base of the tower, the crowd awaited them, headed by a group of festively dressed young women holding garlands of flowers and bread to adorn the teponaxtli, which "moments before had been announcing the voice of the Celestial Jaguar from the cupola,"[37] when it appeared borne on the back of one of the tigres. When the other masked figures had descended, the four of them, bearing the now-decorated teponaxtli, led the crowd in a solemn procession toward the main altar of the church on which rested the gold monstrance containing the sacred host. On reaching the altar, the masked figures moved the monstrance to one side, depositing the flower- and bread-laden teponaxtli in the place of honor. Catholic hymns were sung and Catholic prayers said while the tigres executed silent, feline movements in honor of the enshrined teponaxtli. Following these acts of devotion, the tigres picked up the teponaxtli and led the crowd of worshipers, now a lengthy procession, through the streets of the village to the houses of the mayordomos and padrinos.[38] Such a description al-

lows us to feel as well as understand the syncretic unity of the experience woven, like the ritual on the Day of the Holy Cross, from strands of indigenous and Christian ritual. The indigenous symbols of mask and teponaxtli have merged with the Catholic symbols of cross and host to create a single, syncretic ritual experience for the participant.

There are obvious similarities between this activity on the eve of the harvest festival and the activities propitiating the aires at the beginning of the growing season. Both involve the masked tigres, a cross decorated with flowers and bread, and a procession through the town. In both cases, there is what clearly seems to be a conscious replacement of Christian symbols with pagan ones: in the harvest festival, the teponaxtli replaces the host in the central position on the altar as it has "replaced" the cross atop the tower; in the earlier ritual, the tigre combat "replaces," for some of the participants at least, the attendance on the cross as the culmination of the ritual activities. Thus, in both cases, a powerful indigenous symbol related to the jaguar is equated with Christian symbols, and in both, the ritual is fundamentally involved with bringing a religious symbol deemed to be a living thing down from a height to the temple, a practice with obvious overtones of pre-Columbian, pyramid-related ritual. These similarities show the depth and importance of the syncretic merging of the two traditions as the ritual redefines the most fundamental of symbols—the Christian cross and the indigenous mask—within the ritual context to accomplish that fusion.

But there are basic differences between the two ritual observances as well, the most important of which is the fact that the harvest festival does not involve the sacrifices that are the focal point of the earlier fertility ceremonies. In the latter, the tigres not only do not shed their blood in ritual combat, but as Sánchez Andraka states explicitly, the Zitlaleños believe that in the dangerous climb up the church tower, "no one has ever fallen."[39] And no chickens are sacrificed in connection with the offerings to the cross atop the cupola or to the teponaxtli. The reason for this difference seems obvious: this ritual activity is not done in reciprocation for the gods' sending of rain and thus does not require sacrifice. The difference points directly to the fundamental fertility symbolism of the two ritual situations and demonstrates that in the case of these two observances, at least, the merging of the two traditions leaves the fundamental purpose of the indigenous system intact since neither a Festival of the Holy Cross nor a Festival of the Patron Saint would normally be fertility related.

The two indigenous symbols central to the spiritual life of the people of Zitlala, the tigre mask and the teponaxtli, are both related to the jaguar: the mask images forth the jaguar's features, and the teponaxtli allows its voice to be heard. These indigenous symbolic forms manifest the sacred as they have always done for the peoples of Mesoamerica. They are animated by the force of the divine and are therefore seen as symbolically equivalent to the living cross, the other important spiritual symbol in Zitlala. Thus, the jaguar, through his mask, continues to provide a metaphor for the reciprocal relationship between man and the world of the spirit, a relationship through which the sustenance of man's life is provided by the force of the spirit. That this is true is indicated, in an interesting way, by Suárez Jácome. Enumerating the factors in the life of Zitlala which are changing these centuries-old customs and beliefs, she lists education, along with the influence of the priest, the civil authorities, and the economic system, as a factor. Now, she says, "it is believed by students that rain is a phenomenon of nature which is involved in a cycle independent of ritual, and the teachers (90% of whom are strangers to the community and to the culture) condemn the rites as barbaric."[40] These teachers, on behalf of "modern life," are attacking a set of assumptions wholly alien to their own culture and in so doing indicate clearly the nature of those assumptions. The jaguar's days are numbered, it would seem, at least in Zitlala.

The symbolic importance of the jaguar mask at Zitlala echoes what we have seen in the dance-dramas of los Tecuanes and los Tlacololeros. Superficially different from the activities of the tigres of Zitlala, beneath the surface they are the samerevealing metaphorically the reciprocal, sacrificial relationship with the world of the spirit through which man's life is sustained. While this jaguar symbolism is strongest in Guerrero and the closely related areas of Morelos and the state of Mexico where los Tecuanes, los Tlacololeros, and their variants flourish,[41] it can be found elsewhere as well, especially along the Pacific slope and in the neighboring highlands from central Mexico through Oaxaca and Chiapas to Guatemala. In the Mixteca along the Pacific coast of the state of Oaxaca, the area called the Costa Chica, carnival dances and antics are performed by a group of masked figures, los Tejorones , and among those dances is a tigre dance. Called in Mixtec El Yaa kwiñe , in its plot it is reminiscent of los Tecuanes,[42] although, due no doubt to the nature of carnival, the performers improvise a great deal.[43] Those improvisations, according to Flanet, usually have highly sexual, generally tabooed, implications that often provoke violence, leading, at times, to fights, serious injury, and even death. The tigre epitomizes the antisocial tendencies within the performance, representing the prohibited forces of violence and sexuality.[44]

Although the tigre plays only a part in the carnival activities of the masked Tejorones, its role defines the parameters of Mesoamerican carnival in

a significant way. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, in his penetrating analysis of the carnivalesque,

carnival is the festival of all-destroying and all-renewing time ... This is not an abstract meaning, but rather a living attitude toward the world, expressed in the experienced and play-acted concretely sensuous form of the ritual performance. . . . All carnivalistic symbols are of this nature: they always include within themselves the perspective of negation (death), or its opposite. Birth is fraught with death, and death with new birth.[45]

Such a formulation suggests the basis for an inclusion of the tigre and its sacrificial fertility symbolism within the pre-Lenten carnival festivities that are not generally thought of as agricultural festivals. Both agricultural fertility and the death and resurrection of Christ are potent examples of the principle of rebirth, of the eternal return of life after the death that necessarily precedes rebirth. We have seen the relationship of ritual violence to this symbolism in the paradigmatic case of the Zitlala tigres, which explains the violence, injury, and death, sometimes symbolic and sometimes very real, always associated with the masked tigres as the sacrifice of life to life so that life may continue in its eternal cyclical alternation with death. Blood must be shed in that process of renewal.

But the Mixtec carnival tigre seems not quite so directly related to fertility as his Nahuatl counterparts. The plot of the Costa Chica dance-drama is similar to los Tecuanes, the least obviously fertility-related tigre dance, and the actions of the Mixtec tigre in their extreme sexuality and violence seem more consistent with the inversion of values of carnival than with the dance-dramas associated with agricultural festivals. When he is not fighting his would-be killers or assaulting the cow or one of the other animal characters, he is preoccupied with sexual concerns, using "his principal attribute—his long tail—constantly: he masturbates with it, uses it sexually to violate the cow or one of the tejorones while the others assault him sexually, handling him now as a woman, now as a man and, with his complicity, imitating either homosexual or heterosexual coitus."[46] Such activities have obvious fertility implications, suggesting that in the Mixteca the tigre's role in essentially agricultural ritual has been modified to fit the carnival context. The tigre mask is surrounded by those of the tejorones and acts accordingly. J. C. Crocker points out the underlying general truth.

Clearly the complex meanings shown forth in any one mask are amplified, negated, and generally culturally debated through other masks, both those appearing simultaneously with it and those in other ceremonials. Furthermore, the mask's symbolisms are obviously enhanced by those meanings conveyed through other material objects used in the ceremony—the songs, lyrics, dance movements, special foods and drinks and drugs consumed only or mainly on such celebratory occasions.[47]

And as Flanet points out, the dominant activities of the Tejorones parody the social order in a deliberate inversion of accepted values and modes of behavior. Forming what she calls a "counter-society," they mask themselves and dress in rags, insult and ridicule spectators, both male and female, and assault them with sexual gestures; they also attempt to provoke the indigenous authorities who are watching by parodying their actions and behavior and do the same with the mestizo authorities and important citizens.[48] In all these activities, but especially in their attitude toward the authorities, they exemplify the classic themes of European carnival. According to Bakhtin, "the primary carnival performance is the mock crowning and subsequent discrowning of the king of carnival" in a parody of normal life. And that "parody is the creation of a double which discrowns its counterpart." Essentially, this "is the very core of the carnivalistic attitude to the world—the pathos of vicissitude and change." But it "is an ambivalent ritual expressing the inevitability, and simultaneously the creativity of change and renewal."[49] Although the details of the performance of the Mixtec Tejorones differ from those of the much earlier European carnival that Bakhtin describes, their parody of authority has much the same purpose. But in the Mixtec case, both the sexual byplay and the violence allow us to see clearly that their social level of interpretation is complemented by another level—that of agricultural fertility where sexual union and sacrificial bloodshed produce rebirth in a different sense. In both cases, order is restored after the individual cycle ends. Thus, at the very basis of the symbolism of carnival is "the cognizance of a cyclical time which is recurrent [and] capable of regeneration."[50] On each of its metaphoric levels, carnival opposes the wildness inherent in nature to the order necessary for the existence of human society and shows that that order must constantly be reborn from the reinvigorating wildness within nature and within man. It seems fitting that "the tigre is central to the Tejorones. "[51]

The masked carnival dances of Juxtlahuaca in the Mixteca Baja provide a similar example of the tigre in a carnival context. In contrast to the highly structured and rather formal Festival of Santiago held on July 25, which is the only other festival involving masked dancers, "carnival performances . . . appear, seemingly spontaneously, on street corners, in the open plazas, and wandering from house to house." The tigre forms part of this festive spontaneity. As part of the Chilolos del Ardillo, there are two clowns. One, Mahoma del Ardillo (Mohammed of the Squirrel), "wears a hairy black-faced mask and carries a stuffed squirrel, . . . a gun and a hunting bag." The other, Tigre or Tecuani, "wears

a spotted jaguar suit and a dramatic feline mask." The two of them "enact a spoof of hunting with the Tigre as the ultimate victim." The strong sexual overtones associated with the Costa Chica tigre are present in the Juxtlahuaca carnival although associated not with these clowns but with the performance of the Macho who, in "courting" Beauty violates every sexual taboo by "yelling obscenities, speaking of sex quite explicitly, and . . . enacting numerous deeds." The implications of the sexual activity are complex since it is not lost on the spectators that the ostensibly female Beauty is actually a man wearing the mask of a woman.[52] Carnival at Juxtlahuaca thus contains the same elements found on the Costa Chica, although they appear in somewhat different form.

The carnivalesque actions of the Mixtec tigre barely mask his very real fertility connections. His sexual activity can be seen as metaphoric of the fertility his symbolic death will achieve, a view supported by the fact that similarly sexual activities, though not so extreme, are associated with the tigre dance-dramas of Guerrero and Morelos in which the tigre and other characters often tease the onlookers with comments relating to their sexual lives and capabilities. And according to Marion Oettinger, the festivities on the Day of the Holy Cross at Zitlala include a masked clown, not directly connected to the tigres, who teasingly menaces onlookers with "a large ceramic vessel in the shape of a penis. With this phallus, the clown moves about the crowd simulating sexual acts with men and women."[53] And the violence associated with the tigre, as we have seen in the case of Zitlala, must be seen as the blood sacrifice necessary for the propitiation of the forces that will ultimately send the rains and assure fertility. These motifs, so clearly related to fertility, are an integral part of the symbolic nature of the jaguar, accompanying that symbolic beast even in ritual, like that of carnival, not overtly related to agricultural concerns.

The tigre masks and tigre dances of the village festivals of Oaxaca are neither as numerous nor as significant as those of Guerrero and Morelos, and the farther one travels along the Pacific slope, as Horcasitas has noted,[54] the fewer tigre dances and masks one finds. The masks and characters that do exist among the Maya are usually involved in other dances, often revolving around the serpent or the hunting of a deer. That they have a long history is clear from the fact that the colonial dance with which we began our discussion was performed, and prohibited, in Tabasco. Mercedes Olivera B., after suggesting that such dances in Chiapas similarly have features of clearly pre-Hispanic origin related to "the earth, water, and fertility" and that they are related to los Tecuanes, notes that "other elements such as the deer and the serpent (calalá )" are involved in the dances.[55] She records descriptions of three versions of E1 Calalá , each of which involves one or more tigres and are clearly fertility related since "the dance is dedicated to Tlaloc, god of rain. "[56]

Similar uses of the tigre are to be found among the Guatemalan Maya. Horcasitas mentions various hunting dance-dramas involving the tigre,[57] and the description of one of them, a Deer Dance, by Thompson in 1927 reveals obvious similarities to los Tecuanes of central Mexico. Its pre-Columbian roots were suggested to him both by the appearance of the masks and by its being performed at roughly the same time of the year as similar pre-Hispanic dances.[58] David Vela categorizes such dances as "primitive forms of pre-Columbian dances" in contrast to the few dances such as the Rabinal Achi and the Baile del Tun which have survived virtually intact from pre-Columbian times,[59] and Lise Paret-Limardo de Vela also suggests a pre-Columbian source for the dance-drama on the basis of its dedication by the dancers to indigenous gods and its inclusion of a shaman who appeals to those gods for help for the hunters of the tigre.[60] But Gordon Frost, noting ParetLimardo's assertions, illustrates a jaguar mask from San Marcos with two crosses painted in black, like the mask's spots, between the eyes and on the forehead.[61] Thus, the Guatemalan tigre seems also to continue his pre-Hispanic existence within a syncretic framework.

While all of these masked jaguar impersonators among the Maya play important roles in fertility-related ritual, the year-ending rituals of the Festival of San Sebastián enacted by the Tzotzil Maya of Zinacantan, Chiapas, provide an example of jaguar characters with clear fertility implications playing a role in a much larger drama. Vogt, who describes the events of the festival in great detail, suggests that their complexity, resulting from the multi-vocal nature of the festival, makes understanding their symbolism difficult.[62] While its ritual may not be primarily related to fertility, there is within it a fascinating constellation of symbols suggesting that on one of its many levels it not only has fertility implications but is probably still today a fertility ritual. This level, of course, can coexist with the others because it is "saying" essentially the same thing but applying the common theme to this particular area of human concern. We will focus our attention here on that level, pulling out of the complex ritual those elements that relate to fertility, elements strikingly similar both to those found in the festivals of Guerrero which we have discussed and, in their subordination to other themes, to the Mixtec carnival of Oaxaca.

The focus of the ritual is the annual "changing of the guard" of the town's cargoholders, a focus clearly indicated by the attire of those officials. While the newly installed cargoholders wear the regalia of their offices, the outgoing officials im-

personate what Vogt calls "mythological figures." Among them are jaguars "dressed in one-piece, jaguarlike costumes of orange-brown material painted with black circles and dots. Their hats are jaguar fur. They carry stuffed animals in addition to whips and sharply pointed sticks [and] . . . make a 'huh, huh, huh' sound."[63] Except for their lack of a mask, the similarity between these figures and the masked tigres of Guerrero is striking, and the stuffed animal is a common feature of the tigre dances we have discussed. Interestingly, these figures' identifying hats display masks as they were often displayed in the headdresses worn in pre-Columbian ritual, and the other characters display other variations typical of pre-Columbian mask use: the Plumed Serpents of the festival wear hats that are masks; the White Heads wear forehead decorations that are often described as masks; and the Blackmen wear cloth masks over their faces.[64]

Not only the appearance of the jaguars and their relationship to the metaphor of the mask but the extensive sexual humor of the festival, humor in which the jaguars are directly involved, recalls the central Mexican tigres generally and the Mixtec carnival specifically. In the most graphic of terms, for example, the jaguars accuse officials of neglecting their duties to engage in sexual activity and use their stuffed animals to represent the negligent officials' wives in similarly graphic parodic actions.

Stuffed female squirrels [are] painted red on their undersides to emphasize their genitals and adorned with necklaces and ribbons around their necks. The men carry red-painted sticks carved in the form of bull penises, which, to the accompaniment of lewd joking, are inserted into the genitals of the squirrels. The squirrels symbolize the wives of those religious officials who failed to appear for this fiesta and complete their year of ceremonial duty.[ 65]

Sexuality is also emphasized in the jaguars' climbing and descending from the Jaguar Tree as their "genital areas are playfully poked with the heads of the stuffed animals."[66]

That ascent and descent of what is in this case an artificial tree, a branched pole set up for the festival, is another familiar element of tigre ritual, and in the festival of San Sebastián, it is clearly fertility related. After circling the tree three times and leaving their stuffed squirrels on the ground, "the two jaguars, followed [hunted?] by the Blackmen, climb to the tree's uppermost branches. Laughing and shouting, they spit and throw pieces of food at the crowd, supposedly 'feeding' the stuffed animals."[67] The fertility implications seem obvious as food and saliva "rain" down on the spectators from the jaguars. It would, in fact, be hard to imagine a more literal rendering of the "gods" sending rain and sustenance. That this takes place from the Jaguar Tree, in which the tigre is killed in Guerrero, and that the jaguars are pursued up it by the Blackmen suggests sacrifice here, just as it does in Guerrero.

The significance of this episode is enhanced by its being one of two similarly structured episodes in the festival. The other takes place at Jaguar Rock, a large boulder.

At the base of the boulder is a wooden cross, where the Lacandon, flanked by two jaguars, places four white candles and lights them. The others join the Lacandon and Jaguars to kneel, pray, and finally dance in front of the candles and cross. Then the Jaguars and Blackmen climb on top of the boulder and the Jaguars light three candles in front of a cross there. The Jaguars and Blackmen subsequently set fire to a heap of corn fodder and grass on top of the rock and shout for help as they toss the stuffed squirrels down to their fellows on the ground, who in turn toss them up again. . . . The grass fire on the boulder signifies the burning of the Jaguar's house and the death of the Jaguars; the two Jaguar characters descend from the rock with the Blackmen and crawl into a cave-like indentation at the base of the rock to lie still, pretending to be dead. As the Jaguars lie there, the Lacandon pokes or "shoots" at them with his bow and arrow and then turns to seize two Chamula boys from the onlooking crowd. He brings them near the prone Jaguars and "shoots" the boys with his bow and arrow. Symbolically, the Jaguars are revived by the transference of the souls of the Chamula boys to their animal bodies and they leap up, "alive" again, to drink rum, [and] dance awhile.[68]

All of the elements of fertility ritual are present, but in a configuration now emphasizing rebirth rather than the provision of sustenance; the key to the ritual's emphasis is the revival of the Jaguars, which is also, paradoxically, a rebirth of the boys who have been "shot," or sacrificed, so that the Jaguar, or "god," might live. Their souls do not die but live on in altered form. Since all this is clearly related to the burning of the grass and corn fodder, in a land of slash-and-burn farming, it is obvious that such burning, or "death," must precede the rebirth of the corn. And that burning is said to cause the destruction of the Jaguar and of his house, a ritual demonstration of the essential fact that while particular living things may die, the life-force does not; it can be counted on to revivify nature. That these Jaguars do not wear conventional masks but are involved with all the variations of mask use is fascinating since the ritual depends on the central metaphor, which has, at least since the time of the Olmecs, been symbolized by the mask. Here again we see the natural world as the equivalent of a mask, lifeless until it is animated by the

force of the spirit and projecting in its symbolic features the "face" of the world of the spirit.

It can also be seen that the events at Jaguar Tree and Jaguar Rock are related to essentially pre-Columbian metaphors in their employment of up/ down oppositions. In both cases, the ritual emphasizes the tops of Tree and Rock. It is from the Treetop that sustenance flows, and it is atop the Rock that the death—or sacrifice—of the Jaguars takes place. Such activities correspond to pre-Columbian myth, in the connection of mountaintops with rain, and ritual practice, in the location of sacrifices in the temples atop pyramids. Furthermore, the episode at Jaguar Rock opposes the top of the Rock to the "cave": sacrifice takes place above and revivification below. These metaphorical uses of heights and caves did not end with the Conquest, nor are they presently to be found only in Zinacantan. In varied forms, they are central to the ritual associated with the mask of the tigre from Guerrero to Guatemala.

These similarities between the festival of San Sebastián and the tigre dances of central Mexico are rather general, but there is another similarity that is so specific as to be both amazing and quite difficult to explain. Central to both Zinacantan's Festival of San Sebastián and Zitlala's Festival of San Nicolas is a sacred teponaxtli. Zinacantan's is called the t'ent'en, and it normally "rests" in a small chapel. For the festival each year,

the drum is ritually washed in water containing leaves of sacred plants, . . . reglued, and decorated with bright new ribbons. The similarity between its treatment and that of saint images is striking. Like a saint it is referred to as "Our Holy Father T'ENT'EN"; . . . before its major ceremonial appearance, it is washed and "clothed. " The drum is involved in only two rituals each year: the fiesta of San Sebastián and the rain-making ritual, for which shamans must make a long pilgrimage to the top of Junior Great Mountain south of Teopisca. Its appearance at any other fiesta is forbidden.[69]

While it is not suggested in the discussions of either Vogt or Victoria Bricker that the t'ent'en provides a voice for the gods as does the teponaxtli of Zitlala, Vogt does say it is believed "that the t'ent'en has a strong and powerful innate soul" and that it is "continuously played and carefully tended throughout the fiesta period."[70] This essential similarity suggests another. The employment of the t'ent'en indicates that, on one level at least, the Festival of San Sebastián is to be "paired with" Zinacantan's rain-making ritual in much the same way that Zitlala's harvest festival provides a complement to its rain-petitioning ritual, for the San Sebastian festival also completes the annual cycle and inaugurates the beginning of a new year.

That final similarity suggests that the Chiapas and Guerrero festivals have similar fundamental purposes. Vogt speculates as to the general meanings of this festival.

Why does the richest ritual segment of the annual ceremonial calendar occur in December and January? The period corresponds to the end of the maize cycle. . . . [In addition] the period of Christmas to San Sebastián—from the point of view of either the Catholic saints' calendar or the movements of the sun—is the time of transition from the old to the new year. . . . It is my thesis that the Zinacantecos are first unwiring, or unstructuring, the system of order and then rewiring, or restructuring, it, as the cargoholders who have spent a year in "sacred time" in office are definitively removed from their cargos and returned to normal time and everyday life.[71]

Thanks to Vogt's careful and lengthy observation of Zinacanteco customs and to his painstaking analysis of their ritual, we can begin to understand its almost incredible complexity and by extension, that of its counterparts throughout Mesoamerica. That complexity here, as in all the cases we have examined, makes sense within its cultural context only because it is organized around a fundamental theme relevant to many levels of experience. In this case, the theme of death and rebirth provides the organizing principle. We have the "deaths" of the calendar year, the cargoholders' year in office, the Catholic saints' calendar, and the agricultural cycle. But in each case, there is a rebirth. Thus, "fertility," the force that "causes" birth, is the driving force the festival celebrates; and the omnipresent sexual humor, some of it directly involving birth, refers quite directly to that force, while the up-down oppositions and the symbolic use of the cave are related to it in an equally clear, if somewhat more symbolic, fashion. As we would expect, the jaguars are right in the middle of these activities symbolizing fertility, and, more unexpectedly, the teponaxtli also plays a central part.

There are, then, a significant number of fundamental similarities between the ritual of the Festival of San Sebastián and the rain-related fertility ritual involving the tigre-masked dancers of central Mexico. Both Bricker and Vogt see this ritual as rain-related, but neither sees the Jaguars as important in that regard. On the basis of their understanding of pre-Columbian thought, both see the costumed figures identified as k'uk'ul conetik (literally, plumed serpents),[72] as central to the rituals' rain symbolism. Vogt associates them with Quetzalcóatl whom he sees as a "deity of new vegetation,"[73] and Bricker relates them to the Ehécatl aspect of Quetzalcóatl since Ehécatl symbolized for the pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico the winds of the rain storm which sweep the roads clear for the coming of the rains. She identifies another group of characters in the festival, the White Heads, with Tlaloc on the basis of a tri-lobed

device worn on their foreheads which she sees as similar to tri-lobed designs associated with Tlaloc in the art of Teotihuacán and Tenochtitlán.[74] To us, of course, these seem roundabout ways of demonstrating the clearly pre-Hispanic roots of the fertility aspect of this ritual. The key is not really the plumed serpent but the jaguar, the source of attributes for the mask of the rain gods of Mesoamerica from time immemorial. That this is the real connection between this ritual and rain is demonstrated conclusively by the numerous similarities, some amazingly precise, between this ritual activity and the fertility ritual of central Mexico which revolves around the tigre-masked impersonator of the jaguar; the plumed serpent plays no role there.

The striking similarities between the jaguarrelated fertility ritual of such widely distant villages is obviously the result of evolution from a common source rather than direct contact, but the clear differences indicate that that source lies relatively far in the past. How far is indicated by what is known of the history of Zinacantan and by the fact that the activities of the Jaguars here and the features of the Guerrero tigres whose activities are so similar point to a central Mexican source. Vogt believes that whatever central Mexican influence there was in pre-Conquest Maya Zinacantan came during the time of the Toltecs,[75] the time of the dispersion of central Mexican religious forms generally, and of Tlaloc-related symbols particularly, throughout Mesoamerica. Positing a Toltec-period beginning for the jaguar symbolism of the fertility ritual would certainly fit Bricker's identification of the Plumed Serpents here with Ehécatl as that aspect of Quetzalcóatl was often associated with Tlaloc in the context of the rain storm by the Aztecs, an association we can safely assume was part of their Toltec heritage. Only such a historical development, it would seem, could explain the numerous and remarkably precise similarities between Zinacanteco ritual and that of Zitlala and other distant communities.

One can only conclude from all of this evidence that the contemporary jaguar-masked or costumed impersonator has a long history, going back at least three thousand years to the Olmecs. In addition to tracing the development of the features of mask and costume, we can also ascertain that the symbolic meanings associated with that metaphoric disguise have remained constant. These contemporary "jaguars" are still involved with maintaining, through ritual sacrifice, the order that guarantees the coming of the rains at the proper times and in the proper amounts; they are still involved, at least in Zinacantan, with the symbolization of the divine basis of rulership; and they are still fundamentally involved with symbolizing the opposition between nature and culture and the necessity for man to resolve that opposition so as to create and maintain a culture within which fully human life can exist. Such realizations not only help us to understand the vital role the metaphor of the mask has played and continues to play in indigenous Mesoamerican thought but also enable us to see both the continuity of that thought and, equally important, its continuing complexity and sophistication.

While the mask of the jaguar provides the fullest, the most compelling, and the most fascinating evidence for the continuity of metaphorical mask use from pre-Columbian times to the present, it is far from being the only example. Two other types stand out although there are numerous specific masks with clear pre-Columbian roots. The masks and dance of los Viejitos as they exist throughout Tarascan Michoacán are widely recognized as having pre-Conquest roots in their symbolization of the relationship between age, or the end of the cycle of life, and the rebirth of youth.[76] And Tarascan ritual also involves los Negritos , black-masked figures whose history, while clearly pre-Hispanic in part, is more difficult to trace. Compounding the difficulty of understanding the Negrito mask is the fact that it is not one mask: there are black-masked figures throughout modern Mesoamerica, and the masks they wear are quite unlike each other. There are two Tarascan masks that differ in both appearance and function; the Tejorones of the Mixtec carnival wear small black masks with Negroid features displaying contrasting white areas of striking design, but there are also quite different Negrito masks in Oaxaca. Among the Totonacs in Veracruz there is still another variant, this one involved in an agricultural drama portraying the conflict between the black-masked Negro and his boss who wears an identical mask that is white. And there are a number of other variants as well as unmasked Negritos who wear elaborate costumes.[77] While some of them surely have pre-Columbian roots, others may not; their common color is not clearly illustrative of a common heritage.

What is abundantly clear is that the tradition of masked ritual, as well as particular masks, survived the Conquest and that the particular survivals carried within their symbolic features the same meanings they had embodied in pre-Columbian society. More important, the continuing tradition of mask use allowed the mask to retain its centrality as a metaphor for the most fundamental relationship between humanity and the world of the spirit that created and sustains human life.