Chapter Eight

Bhaktapur's Pantheon

Introduction

The city of Bhaktapur contains many material representations of gods, a witness to its long history and to close contacts since its earliest days with India, that great incubator of forms of divinity. The multitude of gods whose representations have persisted in Bhaktapur and the Kathmandu Valley are of great importance to the historian of South Asian religion and of art,[1] but only some of them are alive at present, foci of action, meaning, and emotion. The others are dormant, perhaps to be revived for some future fashion or need.[2]

It is precisely because Hindu deities can be induced into material objects, the "idols" of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic iconoclasts, that they are able to serve the purposes they do in the construction of Bhaktapur's mesocosm. Those objects can be anchored in space or moved through it. They are constructed of meaningful elements and emerge as units of meaning in themselves. They have their own semantic import, their direct implications for meaning, but they are so constructed that their various similarities and contrasts can be used to build a structure of meaning within an overall civic pantheon, the coherent total domain of the gods. That structure helps map the city's symbolic space and its conceptual universe. The crafted gods, the "idols," are joined by more shadowy supernatural figures, some vaguely represented in astral bodies, some in natural stones, and some m the shifting and vague form of ghosts and spirits. These latter figures have their own uses—the

various kinds of embodiment that the members of the large realm of divine and spooky beings have, considerably influencing their meanings and uses.

As usual, we are primarily interested in the level of civic order; hence we are concerned here in the way the deities are used by the public city. Many of Bhaktapur's component units have their own internal deities; most, but not all, of them (an exception, for example, is the deified figure Gorakhnath, the tutelary deity of the Jugis) are versions of the same deities used as the city's public deities. We will comment on some of these component units, on the interior deities of the household and the phuki , and have included some remarks on the special deities of the Brahmans and of the "royal center" and on the ghosts and spirits of importance to individuals.

We will begin by presenting the city's urban divinities in considerable detail. This will give us a basis for considering exactly what it is they contribute to Bhaktapur's mesocosmic organization and how they are able to do it.

Approaches

In the course of the field study we began our investigation of Bhaktapur's divinities with attempts to locate and list as many of the city's active shrines and temples as we could. By "active" we mean those locations that are regularly used by some group of people in Bhaktapur, and that may have some attendant priest. (Some shrines with a priestly attendant have no significant public use or meaning.) Any of the many "inactive" shrines and temples, relics of some past period, may be loci of casual or private devotion by passersby, but they are not important to the city in the same way as the active ones that concern us. The active shrines and temples were mapped on detailed aerial maps of Bhaktapur, which gave us a first basis for approaching the spatial location and implications of groups or categories of divinities. Subsequently, Niels Gutschow put at our disposal maps that he and his associates prepared of temples and shrines, and we have used them, when noted, to amplify, supplement, and correct our own materials. These surveys were supplemented by discussions with religious experts on various aspects of the divinities and by materials on their use (presented in later chapters and appendixes) and on their personal meanings to various individuals.

In this chapter, and throughout the book, we have chosen to give divinities their Sanskrit names, rather than either the Newari approximation of that name or the popular Western equivalents. We use the Newari form in a few special cases where it has only an attenuated connection or no connection with a Sanskrit form.

Divinities: Housing and Setting

We have used "temples and shrines" as a covering phrase for the various settings in which the divinities are found, but that setting is more complex. Local usage differentiates "temples" (dega :, from Sanskrit, devagrha[*] ); "god-houses" (dya: che[n] ); pith (Sanskrit, pitha ) "hypaethral shrines"; and an otherwise nonspecified residual of "gods' places"—stones, fountains, trees, and so on. There is also a class of supernatural beings, ghosts, and spirits who have no anchored setting, airy nothings lacking a local habitation, if not a name. This lack of a home, like the vagueness of their form, is an essential aspect of this latter group's meaning and use.

1. Temples, dega:s.

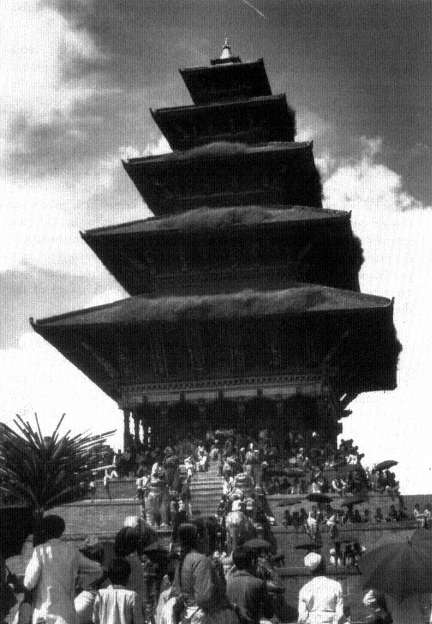

These are buildings of various degrees of elaborateness (see fig. 10), acting as foci for the worship and the spatial influence of the particular god (or gods) they contain. They add to the meaning of their contained god their own symbolic meanings (Kramrish 1946). The historical connections and stylistic and structural features of Newar (and Nepalese) temples have been treated in monographs by Weisner (1978) and Bernier (1970) and as part of larger studies by Korn (1976) and Slusser (1982). Bhaktapur has two kinds of temple buildings with very different external appearances: the traditional Indian form and the tiered-roof "Nepalese" temple, which somewhat resembles the "pagoda" temples of China and Japan. These two local styles are not differentially named, and they do not differ in function.[3]

Mary Slusser (1982, 128) writes of the Newar temple (her remarks applying to Hindu temples in general):

The dwellings of the gods of Nepal are quite unlike those in many other parts of the world that are designed to house both the divinity and a congregation assembled to worship. Despite many collective sacred rituals, Nepali worship is fundamentally an individual matter. The temple, therefore needs to make no provision for a congregation. With notable exceptions, the worshiper ordinarily does not penetrate the temple at all. He tenders his offerings

Figure 10.

A Newar-style temple. The Natapwa(n)la temple m Ta:marhi

Square.

through a priestly intermediary from whom, in return, he receives the physical sign of the god's blessings (prasada ). Further, not only is the god within the temple an object of worship so is the temple itself.

The "notable exception" for Bhaktapur includes some of the events at the royal temple complex, Taleju, where large numbers of people are involved as actors and congregation. But Slusser's remarks generally characterize Bhaktapur's other dega: s. In Bhaktapur, as we shall see, the proper loci for "congregations" are in other spaces.

2. God-houses, dya: che(n)s.

Although dega: , "temple," is ultimately also derived from a Sanskrit phrase for "god's house," the dya: che(n) (literally in Newari "God's house," dya: , god, plus che[n] , house) is where portable images of divinities are kept. These images are carried outside for various rituals, processions, or festivals, and then returned to the house. Some of these buildings are quite elaborate in themselves. Although many important portable gods have their own god-house, many portable images are kept within a temple, where they are separate and distinguished from the fixed temple image of the divinity.

3. Shrines.

There are many figures representing divinities in Bhaktapur that are not enclosed by buildings. These may be free standing statues or simply carved or natural stones. The latter shrines are "aniconic." Often arches or canopies are placed behind or over these representations. Included here are the "hypaethral" or open-to-the-skies shrines of the nine Mandalic[*] Goddesses. These shrines are pith (Sanskrit pitha ), a class of shrines of certain Tantric goddesses in the classic Hindu tradition marking places where pieces of the goddess Sati's dismembered body fell from the sky (see below). Slusser (1982, 325) claims that some temples of the Newar Tantric goddesses reflect such hypaethral origins:

Many [goddesses] have only hypaethral shrines. Still others have had temples built over what were obviously once typical hypaethral shrines. Characteristically, the sanctums of such later-day enclosures are very open, the temple's multiple doorways or colonnades permitting an unobstructed view, and the sanctum itself often sunken well below the present ground level. These sunken and airy sanctums have much to say about the antiquity of many of these goddesses and their ultimate chthonic origins. Symbols of such divinities should be open to the skies and woe to the misguided votary who closes them in.

4. Non-Newar Hindu structures.

Bhaktapur has many Buddhist religious structures—stupas, vihara s (religious centers derived from monastic precursors), and god-houses, as well as non-Newar Hindu centers (matha[*] s) for holy men, which are peripheral to our present concerns.

Gods With Temples and Shrines—Some Numbers

Shrines and temples are the seats of one segment of Bhaktapur's super-naturals, the "Puranic[*] deities" of classical, post-Vedic Hinduism. By our count and criteria there are about 120 active shrines and temples within or just outside the boundaries of Bhaktapur. They are one of the two sets of spatially fixed representations in the public city; the other is a numerous and heterogenous class of "deified stones." The shrines and temples are distributed among these deities as follows, with the number of shrines and temples given in parentheses: Visnu[*] (29), Siva (28), Ganesa[*] (24), Sarasvati (3), Bhimasena (3), Nataraja (2), Hanuman (2), Krsna[*] (2), Rama with his consort Sita (3), Bhairava (1), Jagannatha (2), Dattatreya (now regarded primarily as a combination of Siva and Visnu[*] ) (1), and the group of dangerous or Tantric goddesses that includes some fourteen major named forms (26). We thus have some twenty-six classical Hindu divinities represented in public urban space. Eighty-two of these shrines and temples have various kinds of temple priests, pujari (see chap. 10). The other structures do not have pujari. s We will discuss the spatial locations and the uses of the various temples and shrines later in this chapter and elsewhere in this book, but we may note here that about one-quarter of the temples and shrines are primarily related to the city as a whole, while the rest are related to one or another of the city's major constitutive spatial divisions.

Sorting Supernaturals—Some Preliminary Remarks

To consider a particular divinity as a member of a pantheon or of some larger domain of supernaturals in a certain community during a certain segment of that community's history is radically different from considering that divinity throughout its long history and its South Asian (and beyond) areal variations. Siva as a member of Bhaktapur's pantheon is not the same as the Siva considered in a general and unrooted

sense, through, say, a compendium of his various mythological accounts and his historical usages and forms throughout South Asia.

When Hindu divinities are considered from an historical or South Asian areal viewpoint, they have a very great number of accumulated forms, names, meanings, myths, aspects, philosophical implications, and contradictions. Several attempts have been made at encyclopedic approaches to the whole Hindu pantheon (e.g., Banerjea 19.56; Mani 1975; Rao 1971; Daniélou 1964) and to individual divinities or to some of their aspects (such as O'Flaherty's exhaustive survey of materials on asceticism and eroticism in the mythology of Siva [1973]). Bhaktapur has selected only certain deities from the Hindu tradition for emphasis. For the particular deities it has selected, it further selects and emphasizes only certain aspects of their potential—variously realized elsewhere—for meaning, form, and use. For some of them Bhaktapur sometimes even adds its own attributes, perhaps borrowed from other deities, sometimes ancient local ones.

It is possible for some purposes to consider Bhaktapur's pantheon as a sort of museum, a collection of divine South Asian flotsam that has drifted into the Valley. We cannot avoid our general knowledge of important aspects of the meaning of the divinities in space and time beyond the city, a knowledge shared by the people in Bhaktapur who introduced these figures and who continue to use them, but what is important for us is what is done with the deities in Bhaktapur, their local uses and relations.

The sorting of Bhaktapur's divinities and other assorted "supernatural" figures that follow in this chapter is a sorting, then, for that purpose. We will sort the supernatural beings into several large groups that have morphological and functional contrasts. The groups are:

1. "Major city gods."

These are familiar major gods of Puranic[*] , post-Vedic, Hinduism. They have, at least in some of their important city forms, anthropomorphic or creatural forms, and are located in named temples and shrines known to the city as a whole. These "major city gods" are divided into two contrasting groups, "ordinary gods" and "dangerous gods." The latter require blood sacrifice, are attended by a special class of priests, and are the loci of a special set of ideas and procedures (chap. 9).

2. "Stone gods."

This is a group of deities represented by natural stones. They are related to other natural objects (as opposed to objects created through human craft, like statues) that have divine properties

(springs, lakes, ponds, trees, etc.) but, in contrast to such other natural divinities, have systematic placements and usages.

3. "Astral divinities."

These are associated with the sun, moon, and various heavenly objects and events; are associated mostly with astrological ideas and practices; and have their own special priests.

4. "Ghosts and spirits."

These are a miscellaneous group of vague entities that may be usefully introduced here, and that have some significant contrasts with the other supernaturals.

Major Gods: The "Ordinary" Deities

We have characterized the "major gods" of Bhaktapur as being derived from the most salient and important gods of the early Hindu Puranic[*] tradition, of being situated in temples and shrines of city-wide importance, and of having anthropomorphic forms (some having a mixture of anthropomorphic and animal features). These gods are foci of ideas and symbolic enactments concerning the representation and integration of the city as a whole and of its larger constituent units.

Within this group of "major gods" there is an essential and sharp contrast of two subgroups. One of these is a group of gods who are (when necessary) attended by Brahmans or "Brahman-like" priests (chap. 10). These gods are never offered blood sacrifice or alcoholic spirits. Their icons are in the form of idealized human types, or humanized animal forms. The central divinities in this group are male. The other group of major gods are (when necessary) publicly attended by a special class of priests, the Acariya. These gods are offered blood sacrifice, meat, and alcoholic offerings. Their icons are often in the form of demonic, bestialized human forms, marked by bulging eyes, fangs, and sometimes extreme emaciation. They are sometimes represented gar-landed with necklaces of human heads or skulls, and carrying a human skull cup for drinking blood in one of their many hands. Sometimes these gods are represented as exaggeratedly erotic forms with the faces of beautiful young women and with full breasts. These kinds of gods are predominantly female. When it is necessary to distinguish these two groups in speech, the first are sometimes called "ordinary" gods, and by some Brahmans (mistakenly in historical perspective) "Vedic" gods. The second group are sometimes called "dangerous" gods (in contrast to "ordinary") or "Tantric" gods (in contrast to "Vedic"). There are other significant contrasts in the nature, internal relations, uses, and

significance of these two groups of major divinities, but these remarks will serve to introduce them.

Within the two groups of major gods (as within the other groups of divinities) each particular divinity has his (or her) own personality and significance derived in part from his history, from his present relations with others of Bhaktapur's divinities, and from the uses to which Bhaktapur puts them.

Siva

When people in Bhaktapur are asked which of the Newars' two "religions" they adhere to, a question that is usually phrased as which path, or marga they follow, those whom we have been designating as "Hindus" in contrast to Newar "Buddhists," answer by saying they are Sivamargi, followers of the path of Siva ("Siba" in local pronunciation). Siva (see fig. 11) is most commonly referred to in Bhaktapur as Mahadya :, the Newari version of the Sanskrit Mahadeva , the great god. He is represented in a variety of anthropomorphic images, and as the abstract phallic linga[*] . Siva's status in Bhaktapur is considerably more complex than that of the other benign gods in that he has several levels of meaning. His most striking aspect is that while he is pervasively present as an "idea," as one of the central references helping to locate and explain in various ways the other city gods, he is in comparison to them distant, relatively absent from the concrete arrangements and actions of city religion. Siva's meanings may be distinguished approximately as follows.

1. Siva as the creative principle.

For some more theoretically inclined people in Bhaktapur Siva is the creator god, out of which all the forms of gods (including a particular concrete divinity also called "Siva") are generated. This is a theoretical and philosophical position. In other contexts, as we will see, Devi, the "Goddess," is thought of and praised (by the same people) as the supreme creative force. For the most part the basic, divine, creative principle, called the brahman or paramatman in sophisticated theological discussion, is amalgamated to a general featureless deity, neither male nor female, neither Siva nor Goddess, vaguely conceived as a combination of all gods. This condensed divinity is what some, at least, people have in mind when they think of "god" in some general way, often in such thoughts or phrases as "god help me," in the face of some problem. This generalized deity is called

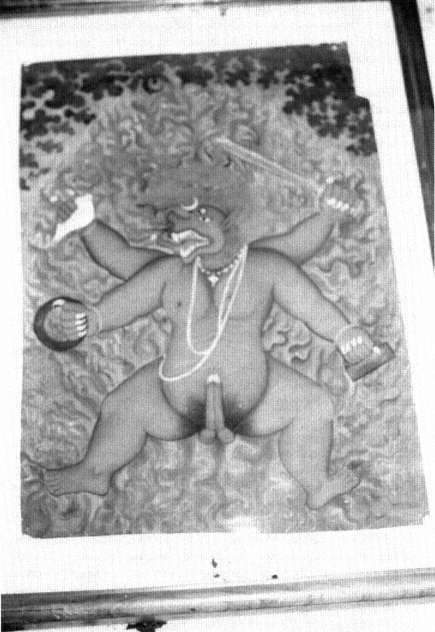

Figure 11.

Siva as a fertility god.

simply dya:: , or sometimes addressed with some honorific Sanskrit appellation, as Paramesvara, Isvara, Bhagavan, and the like. This generalized deity—unlike the traditional idea of the brahman —is aware of the individuals who call on it, and may help. It is not represented in civic symbols or ritual enactments, and represents a "monotheistic" potentiality that must in all likelihood wait for the breakdown of Bhaktapur's present religious system and its eventual "modernization" to realize its social potential.

2. Siva, first among the gods.

A more common phrasing of Siva's greatness is that he is the most important of the gods, the one whom the others respect. This importance is not based on his power, however, nor on his concrete uses in Bhaktapur. He is not like Indra had been in an earlier stage of Hindu belief, the "king" of the gods. His importance, like that of the central, "full" form of the Tantric goddess seems to have something to do with his centrality as a generator of or container of the contrasting meanings of the lesser divinities.

3. Siva as the generator of the dangerous gods.

Siva is, in ways that we will note below, one of the "ordinary" gods. However, he is the agent by which in one context and conception the "dangerous" gods are generated. Many prominent symbolic forms in Bhaktapur concern this generation. They include the idea of Siva's emanation Sakti (below) as well as other types of transformation. Much, but not all, of the symbolism of the linga[*] is related to this transformation, as is much of the symbolism of Tantra. We will return to this in our consideration of Sakti, the dangerous divinities and Tantra (chap. 9). In other contexts, as we shall see, the "dangerous gods," particularly the central, generating forms of the goddess, are conceived as existing independently of Siva. In such contexts Siva becomes quite peripheral, the goddess becomes the central creative force, and Siva's importance or presence becomes greatly attenuated.

4. Siva as one of the group of ordinary gods.

At this level Siva is one of a community of divinities related by the ordinary social ties of family and friendship. The central group of ordinary gods are Parvati, Ganesa[*] , Visnu[*] , Laksmi, Sarasvati, and some secondary divinities associated with Visnu[*] . Parvati is Siva's wife or consort, Ganesa[*] is his son, Visnu[*] is Siva's essential friend, and Laksmi is Visnu's[*] wife. Sarasvati

stands outside these relations. Siva is sometimes represented as a young man with a moustache (see color illustrations). In this form he is thought of as an unattached and dreamy young bachelor. Sometimes he is shown with his consort Parvati to his left, his arm tenderly around her shoulder. He is absent-minded, a dreamer, stumbling in his abstraction into socially dangerous errors from which his friend Visnu[*] must extricate him. He dresses improperly, like a jungle dweller, and sometimes goes naked. He moves at whim from place to place. He is usually gentle and benign in his abstracted way unless roused to fury, and that fury is elemental and potentially randomly destructive. Sometimes he incarnates his vehicle, the bull Nandi. Sometimes he is found in deep meditation on Mount Kailash in the mountains to the north of Bhaktapur. Sometimes he is found in the cremation grounds, or even in the refuse dump in the inner courtyard of the house. His destructive power can be focused and put to use against impersonal and external dangers to the city, but in this transformation we are soon no longer dealing with Siva, something new arises.

Siva represents the human tension between self-absorption and asocial sexuality on the one hand and social involvement taming such problematic states and passions on the other. As Parvati's consort and Visnu's[*] friend, he is under the socializing restraint of those social relations, he needs them. Siva alone—adolescent, yogi-like, alternating between sexual passion and ascetic self absorption—is recognizable both as forest dweller who has escaped from the city and as one important aspect of the man of the city. As the Mahabharata says of this Siva (quoted in Atkinson 1974, 721) [from the Mahabharata , Anusasana Parva, chap. 14]; cf. Mani 1974, 808).

He assumes many forms of gods, men, goblins, demons, barbarians, tame and wild beasts, birds, reptiles, and fishes. He carries a discus, trident, club, sword and axe. He has a girdle of serpents, earrings of serpents, a sacrificial cord of serpents and an outer garment of serpents' skins. He laughs, stags, dances and plays various musical instruments. He leaps, gapes, weeps, causes others to weep, speaks like a madman or a drunkard as well as in sweet tones. With an erect penis he dallies with the wives and daughters of the Rishis.

Siva's essence is in his transformations, which make him both elusively shifting and generative. As O'Flaherty (1973, 36) notes, he is both a yogi and its antithesis, the lover of Parvati. She adds, however, in regard to this and other apparent oppositions in his mythology:

The mediating principle that tends to resolve the oppositions is in most cases Siva himself. Among ascetics he is a libertine and among libertines an ascetic; conflicts which they cannot resolve, or can attempt to resolve only by compromise, he simply absorbs into himself and expresses in terms of other conflicts. . . . He emphasizes that aspect of himself which is unexpected, inappropriate, shattering any attempt to achieve a superficial reconciliation of the conflict through mere logical compromise. . . . Siva is particularly able to mediate in this way because of his protean character; he is all things to all men.

But this protean character in itself limits the semantic possibilities of Siva in Bhaktapur. There is one thing he cannot be to all men, that is a fixed character, and that provides his major contrast to Visnu[*] , who is fixed in his purposes and his conventional forms.

Yogi , bachelor, friend, and husband are all Siva, but Siva disappears in his supernatural transformations. When he has been transformed into his dangerous form, Bhairava, when he emits his sakti ("power"; see chap. 9) or the goddess Devi, these dangerous forms are immediately thought of as independent actors. They have their own myths, legends, and histories. In thought and action they are for the most part disconnected from Siva, except for vestigial traces and markings—a Siva mask carried but not worn, Siva's vertically rotated third eye sometimes, but not always, placed on their foreheads (see color illustrations). And in a further limiting and bounding of the protean Siva to his proper human-like area, it is the "goddess" herself—although in some contexts thought of as generated by Siva—who becomes the shifting, generative force. While Siva's generative activities, the center from which he moves are in the social world, and are related to recognizably human activities and modes of a certain sort—the lover, the adolescent, and ascetic, intoxicated or ecstatic states—it is another figure, the "goddess," who is the center of generation in a much more radically extrasocial world, the world outside the city and its order. Thus, although Siva represents a bridge to the world beyond the city, and beyond all cities, those bridges become burnt for the most part once crossed, and as his transformations come to life, Siva, overtly in Tantric imagery, becomes a corpse. His ongoing and continuing life in Bhaktapur is as a representative of that dimension of the social person which is valued, although in tension with social and moral order. In his transformations to representations of the extrasocial world, Siva becomes almost forgotten. Similarly, when thought of as a creator God, this cosmic Siva is also lost from view when his creation is being considered. In his own anthropomor-

phic right, however, he represents a complex of traits which are unified in being thoroughly human, but in one way or another problematic for social order. This Siva provides problems which must be dealt with by his friend Visnu[*] at the service of the moral community. It is important to emphasize that from the point of view of the corpus of South Asian myths about the relations of Siva and Visnu[*] this is a local choice of emphasis. There are, for example, South Asian stories where it is Siva who must free Visnu[*] from some passionate bondage (e.g., O'Flaherty 1973, 41). Bhaktapur, in fact, develops selected meanings suggested by the major persisting myths and representations of the two gods. Their relation is epitomized in one of the local interpretations of the complex symbol of Siva's power, the linga[*] , whose more central meanings are related to the idea of Sakti (below here, and chap. 9). The linga[*] consists of a column at whose base is an encircling band. In this interpretation of Siva as a component of civic order (rather than as the generator of cosmic forces), the upright column represents Siva and his explosive and expanding energies and the encircling band at the base represents a restraint placed by Visnu[*] around that column of energy to protect, control, and channel it.

There are about thirty active Siva shrines and temples in Bhaktapur. Of these, fourteen are found m four clusters outside the traditional boundaries of the city to the south near each of the bridges to which the city's southern and southeastern roads and paths lead. Another nine are grouped in the two central squares of the town, the Laeku Square in front of the palace and the Ta:marhi Square, both of which, it may be recalled, are (in different contexts) centers of the city. These central shrines and temples were built by the Malla kings and by wealthy families and thar s (such as one group of shrines built by the Kumha:, the potters) as variously motivated acts of private devotion to Siva. Many of the structures outside of the city are of relatively recent post-Malla origin, and it is said they were built there because there was more available space on which to build. Some of these shrines and temples have attendant priests whose stipend is funded by grants of land that were set aside for this purpose at the time of the building of the structure, but may have no other worshipers. Others are the object of worship of descendants of the founding group, or sometimes by people who have made a pledge to worship Siva, perhaps at that particular shrine, in exchange for the fulfillment of some wish. One of the largest and most visually impressive temples in the northern half of the city is devoted to the divinity Dattatreya (Newari, Dattatri), who is thought of as a corn-

bined incarnation of Visnu[*] , Brahma,[4] and Siva. In the Dattatreya temple Visnu[*] is iconographically dominant, but Siva is thought of as the main power embodied in the temple. The temple priests are non-Newars (Jha Brahmans), and the inner sanctum is closed to Newar Brahmans. The temple's main function is as a pilgrimage center for non-Newar Shaivite devotees from India and other parts of Nepal.

For the Newars of Bhaktapur, the Siva shrines and temples, in marked contrast to those of certain other major divinities, are not used to designate any of the internal structural features of city organization. Correlated with this is that there is only one minor annual festival (Madya: Jatra; see chap. 13), specifically devoted to Siva. The great Siva festival for the Newars of Bhaktapur and elsewhere, as well as for Nepalis and for many Indians, has its center out of Bhaktapur (and of the other major Newar cities) at the great Valley shrine complex of Pasupatinatha devoted to Siva as the "Lord of the Beasts," during the major South Asian Shaivite festival, Sivaratri, in the late winter. Bhaktapur itself on that day is a secondary focus for some Shaivite pilgrims, and some of the city's men perform an unusual—in contrast to other forms of local worship—type of devotion to Siva spending the night by fires along the city's public streets, sometimes smoking cannabis, in an enactment that, with its associated legends (see chap. 13, "Sila Ca:re" and our discussion there) illuminate Siva's meaning as a bridge to a transcendent realm.

In Bhaktapur there are several divinities with limited functions, and with names and attributes of their own sometimes said to be "forms" of Siva. There are some statues in stone of a figure with an erect penis locally identified as Siva which are worshiped by families who wish children or specifically a son (fig. 11). Siva is worshiped in the rite of passage of people in their seventy-seventh year as Mrtyum[*] Jaya, the god who conquers time and prolongs life. He is sometimes said to be Nataraja, the god of the dance, who is worshiped by musicians and actors. (Nataraja as the Newar god Nasa Dya: has accumulated, as we will note, other meanings and uses.) Siva is the god buried in the inner courtyard of houses who destroys the wastes thrown there. He is Visvakarma (Newari, Biswarkarma), the god of crafts and trades, who gives power to the tools and implements of the various traditional and modern crafts: the barber's razor, the driver's truck, the farmer's tools.

Siva's meaning in Bhaktapur's supernatural domain is deeply affected by his position in the larger system. We have introduced some

of this, but we must turn to the other members of the domain, each of whom provides context for the others.

Visnu-Narayana[*] And His Avatars

Visnu[*] is usually referred to in Bhaktapur by one of the names historically associated with Visnu[*] , Narayana[*] (Newari, Narayan). Visnu[*] (as we will here refer to this divinity for comparative convenience) belongs centrally to what we will call the "moral interior" of Bhaktapur. Although other gods may be addressed on their special days or for particular unusual problems, Visnu[*] and Laksmi, his consort, are at the loci of ordinary household prayer. Visnu[*] is that fragment of divinity that dwells in individuals as their soul or atma , in the Newar version of the ancient South Asian correspondence of soul and cosmic divinity.

Although there are several and conflicting ideas about the possible fates of the soul after death and about various heavens, and a number of theories as to what determines a person's postdeath state, the focus of most belief and action in regard to personal fate after death centers on Visnu[*] . In the ceremonies devoted to dying, attention is focused on Visnu[*] , and the dying person must pray to Visnu[*] , meditate on him, and address his or her last words to him. In the kingdom of the Lord of the Dead, Yama Raj, it is Visnu's[*] representative who argues the case for the deceased in front of King Yama. This case is based on the individual's merits and sins, virtues and vices, in relation to his following or violating the moral law, the Dharma. Those who follow the Dharma can expect to go to Visnu's[*] heaven. To get to Siva's heaven one must make Siva a focus of meditation, another and radically different path to salvation from the moral path of following the social Dharma. In Visnu's[*] heaven one keeps one's social identity and is joined with one's family in reward for one's social virtue. The salvation associated with Siva and the Tantric gods, moksa[*] , has, in contrast, a problematic and uncanny relation to the social self.

Visnu[*] is represented in Bhaktapur by idealized, princely human forms. Occasionally he is represented in the forms of one of his incarnations, or avatars . He is also represented occasionally by small, rounded stones, locally called salagrams.[5] In contrast to other places in South Asia, Visnu's[*]avatars (Sanskrit, avatara ) in Bhaktapur have minimal cultic significance in themselves and are of major importance only as aspects of Visnu[*] .[6] In contrast to Visnu's[*] twenty-nine active temples and shrines in Bhaktapur, only two temples are actively devoted to Krsna[*]

and three to Rama and his consort Sita (see fig. 12). One of the two Krsna[*] temples is in Laeku Square, and was one of the temples built by the Malla kings for their personal merit. It is attended by a Rajopadhyaya Brahman and contains a portable god image, which is carried around the city once a year. The other temple, in the northern part of the city, has no priest and is used in a casual way by some local people or passersby. Both of the active Rama temples are outside the city boundaries at places where roads meet the river. One of them is part of a complex of temples built by the potter thar , the Kumha:s, living in the southern half of the city, and is attended by Kumha:s and people living in nearby areas. The other, to the southwest, is of some general importance once a year, in connection with the worship of one of the Eight Astamatrkas[*] , Varahi.[7] There are two Hanuman temples associated with the southwestern Rama temple that are visited by many people on the same day of the annual festival calendar as that temple. Hanuman, a divinity in monkey form associated with Rama in the Hindu epics, is also represented in other Visnu[*] temples. Newari art represents still other of Visnu's[*] avatars (particularly Vamana, and Narasimha[*] ), as it also represents Visnu[*] in relation to his cosmogenic aspect,[8] but these representations have no contemporary uses.

The conception of Visnu's[*] avatars is closely related to the idea of Visnu[*] as the divine portion, the atma , of each individual. The avatars represent the incarnation of a portion of Visnu[*] into the ordinary world, as part of a mixture that is in part human (or animal) and part divine.[9] Visnu's[*]avatars are not only incarnated in human or animal forms, but by and large they lead recognizable social lives, albeit with legendary heroic powers.[10] The lives of the incarnations were furthermore located in real space and historical time. These lives were lived for the purpose of reestablishing some desirable social order for humans or for the gods after that order's derangement through some antisocial force usually personified as a "demon" or antigod, an Asura . This is in marked contrast to the case of Siva, whose transformations, such as Bhairava and the Goddess, are emanations in which Siva's identity is transformed and lost, and which are themselves "demonic" forms of the same sort as Asuras . Rather than exist through a unique lifetime, as Visnu's[*]avatars do, Siva's transformations appear and are "reabsorbed" in some contexts or, in others, are as eternal as Siva himself. Although they can defeat the Asuras and other forces of disorder, they are, in themselves, dangerous and problematic to the orderly social world, and must be controlled in turn. In another significant contrast, while Siva's emana-

Figure 12.

Rama and his consort Sita. Note the difference in size.

tions (or in some versions the emanations of Parvati herself) defeat other demons through brute magical force, Visnu's[*]avatars characteristically restore order through cunning and other social skills allied to their divine power.

In Bhaktapur's stories it is Siva in his wanderings and absent-mindedness who is either sometimes dangerous himself, or who allows some devotee to accumulate through meditation and austerities some god-like power, which he then uses in defiance of the gods' order for his own selfish purposes. Visnu[*] must undo the damage, calm Siva, overcome the magic power of Siva's devotee, and restore order. In this contrast Siva is the passionate, romantic dreamer for whom social propriety is a burden. Visnu[*] represents sobriety, decency, and order. The pair represent a familiar universal tension within societies and within individuals.

The twenty-nine Visnu[*] temples and shrines are distributed around the city in close proximity, for the most part, to the city's main processional route. Of these, two are large temple complexes—one immediately south of the upper-lower city axis, and the other in the eastern part of the upper city. Although these two largest temples are located in the lower city and upper city, respectively, they are not considered representative of these city halves in the way that other space-marking deities represent spatial units, and there is no special religious activities that tie them to the halves as such. All these temples are attended optionally by people in their vicinities, sometimes for casual prayer, sometimes in quest of support in some undertaking. Usually Visnu[*] is worshiped not in a temple or shrine but at home. Visnu[*] , along with his consort Laksmi, is, as we have noted, the usual focal god of the household, the focus of most of the ordinary household puja s. They represent the ordinary relations, the moral life of the household, in its inner life. As we will see, for the family Visnu[*] contrasts with another quite different kind of deity, the lineage deity, most often a form of the Dangerous Goddess, which binds the households of the phuki group into a unity and protects them against the dangers of the outside (chap. 9).

Visnu[*] resembles Siva in not being used, in contrast to certain other gods, to mark off the city's important spatial units. He is, as we shall argue, not the proper kind of a divinity for this for Bhaktapur's purposes. Visnu[*] has no major festival in the public city space. He is a major focus of household worship throughout the year, and of special household and temple worship and of out-of-the-city pilgrimages on some

annual occasions, particularly during the lunar month of Kartika (Newari, Kachala, October/November) as he is elsewhere in South Asia at this time.

In recent decades the worship of Visnu-Narayana[*] at the two major temples with music and dancing and without the mediation of a priest in expression of an individual direct devotion to the god free from the spatial, temporal, and social orderings of Bhaktapur as a city, has been growing. Visnu[*] and his avatars have become the object of bhakti , loving devotion, a focus for private salvation and private emotion. Here he is not functioning as a component in a complex system of urban order, but as the kind of personal god who arises when such a city-based system begins to break down. This is no longer the Visnu[*] who is Siva's complement. This is, to recall our conceits of chapter 2, a transcendent "postaxial" Visnu[*] .

Ganesa[*]

Siva in Bhaktapur is a bridge joining different forms of divinity. Ganesa[*] (Newari, Gandya:), an elephant-headed god, is a bridging and transitional figure of a different kind; he provides in several ways for human entrance into the area of the divine. As such, we may contrast him with other divinities, dangerous and uncanny, who are at the threshold of the human moral world and the orderly divine world into areas of chaos and danger. Properly for such uses, he is as attractive in his person as they are horrifying.

Let us consider some aspects of Ganesa[*] as an entrance. As is generally the case in South Asia, one prays first to Ganesa[*] before praying to any other god or before undertaking any important religious activity. The worship of Ganesa[*] is necessary for effectiveness, siddhi , in the worship and manipulation of other divinities. This is an aspect of a more general attribute of Ganesa[*] as "the overcomer of obstacles" (Mani 1975, 273):

Ganapati[*] [Ganesa[*] ] has the power to get anything done without any obstructions [and has] also the power to put obstacles in the path of anything being done. Therefore, the custom came into vogue of worshiping Ganapati[*] at the very commencement of any action for its completion . . . without any hindrance. Actions begun with such worship would be duly completed.

It is necessary to worship Ganesa[*] before both ordinary and Tantric puja s. This is connected with one of his unique features in Bhaktapur,

specifically, that he can be either a dangerous or an ordinary god.[11] Any image of Ganesa[*][12] may receive either the worship and offerings that are proper for the ordinary divinities (e.g., grain, yogurt, cakes) or the blood sacrifices and alcoholic offerings that are proper for the dangerous divinities. (He has, however, a particular animal that is uniquely proper for sacrifice to him: the khasi , or castrated male goat, another image, perhaps, of his marginality.) He is the entrance to these two different realms, otherwise often placed in opposition.

In some settings his image[13] may indicate, represent, or suggest a Tantric emphasis. It may show Ganesa[*] with many arms, and he may be seated next to his Sakti, variously identified as Siddhi (the personification of his power for effectiveness) or Rddhi[*] , "prosperity, wealth, good fortune." In his dangerous form he is sometimes called "Heramba," and thought of as a guru who instructs and therefore introduces students in Tantric knowledge.

There is still another sense in which Ganesa[*] is the entrance into the religious realm. As a benign, humanized animal, a sweets-loving child, the child of Siva and Parvati in their domestic imagery, he is a favorite of children, and in the memory of some respondents was the first god form to whom they became attached—in contrast to others whom they feared as children—and it is Ganesa[*] who (at certain specific temples) is prayed to for help to children who are slow in learning to walk or talk.

As he is elsewhere in South Asia,[14] Ganesa[*] is the divinity of entrances in space as well as in temporal sequences. He is conceived to reside on one side of gates and arches (usually on the right side) while his "brother," Kumara (who has little other significance in Bhaktapur, except in connection with the Ihi , the mock-marriage ceremony) is imagined to be on the other.

Ganesa's[*] shrines and temples are the main fixed divine markers of the twa:s , the village-like units in the city and of some of their component neighborboods (map 13). This local areal Ganesa[*] , or sthan Ganesa[*] (from sanskrit sthana , place, locality), is considered common to the twa: . Although, as we have noted, a particular twa: may have one or more other divinities that in some sense "belong" to it and are its particular responsibility and that may be celebrated in some annual twa: festival, every twa: has its sthan Ganesa[*] . Everyone in the twa: worships here before important out-of-the-house ceremonies and during all rites of passage for members of the household. Thus Ganesa[*] is one of those divinities who have an important relationship to a significant component of urban space, as Visnu[*] and Siva do not. The great majority of

Map 13.

The distribution of Ganesa[*] shrines in the city. The shrines are distributed throughout the city, with most of them on or near

the pradaksinapatha[*] . Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

these twa: shrines are located on the city processional route (see map 12) which connects the twa: s, and thus these individual centers are tied into the larger city.

There are a number of Ganesa[*] temples and shrines, some within the city boundaries and some without, which have specific purposes that can be accomplished only at that particular location with its particular Ganesa[*] . People go to Balakhu Ganesa[*] if they have lost something and wish help in finding it. Children who are slow in learning to talk are taken to a temple just outside of the city to the northeast, Yatu (Nepali, Kamala) Ganesa[*] . One shrine, that of Chuma(n) Ganadya:, is worshiped by the entire city during the solar New Year festival, Biska: (chap 14). All these shrines are also worshiped by local neighborhood people.

The most important Ganesa[*] shrine outside of the city for the people of Bhaktapur is Inara Dya: (Inara God),[15] known in Nepali as "Surya Vinayaka." This shrine, set on a forested hillside south of Bhaktapur, is visited regularly once a week by many people on one of Ganesa's[*] special days of the week, Tuesdays or Saturdays. These trips are considered as both a religious undertaking and an outing. Family members or a group of young friends will go to the shrine taking food with them. In addition to his general function as an overcomer of obstacles ("Vinayaka"), and a first object of worship before approaches to other gods, Inar Dya: can also help children who are slow in learning to walk. According to Slusser, Surya Vinayaka is also "widely consulted as a curing god by the deaf and dumb" (1982, 263). This shrine is not only attended by people of Bhaktapur but also is an important shrine for the Kathmandu Valley both for Newars of other places and for non-Newar Hindus. It is sometimes considered one of four Ganesa[*] temples forming a kind of mandala[*] in the Kathmandu Valley, and which are sometimes visited in sequence (Auer and Gutschow n.d., 17; Slusser 1982, 263).[16]

A Note on Yama

Yama Raja, the ruler of the "kingdom" where in some versions of the adventures of people after death they go to await the fate that the results of their moral behavior, their karma , and/or the proper performance of death rituals secures for them, and who presides over the hell where the perpetrators of some enormous sin must remain for some equitable period, is not properly a member of the urban pantheon in the same way as the other figures we are considering here. He is the personification of death, but a certain kind of death or of death viewed

in a certain way. As such, he belongs among the "ordinary" deities, is in contrast to the dangerous deities, and should be noted here. The dangerous deities can kill, but that is not associated with the sort of dying that Yama is concerned with. Yama, or his messengers, come to collect people in "ordinary" dying. He is a moral agent, part of the ordinary religion of Bhaktapur and is related to the worship and meanings of the ordinary deities (some of whom preside over the heavens where Yama will most likely send the dead individual if he or she is not to be reincarnated back into this world). In either one of the various heavens or the usually foreseen rebirth, the individual will live a pleasant social life, in consort with his or her loved ones (if in heaven) or perhaps with their transformations (in a rebirth). There are other "religious" representations of death—or, more precisely, of being killed—in Bhaktapur that are not within the moral realm. These are within the realm of the dangerous deities or the malignant spirits, within realms where accident and power, not moral behavior, prevail. Against them only avoidance or powerful "magical" devices (chap. 9) might prevail. Yama's judgment and the timing of his visit can, however, be affected not only by good behavior, but also by affection and solidarity in the family, and various kinds of distractions and social deceits can be used to confuse or distract him or his messengers and deflect him.

Yama is variously represented in the annual calendrical sequence, most centrally in the course of the lunar New Year's sequence (chap. 13). He is there representative of what we will call the "moral beyond" of the household, not the "amoral outside," which is vividly represented in other annual symbolic enactments in relation to other deities.

The Ordinary Female Divinities: Laksmi, Sarasvati, And Parvati

In a later section we will be concerned with a cluster of ideas about "the goddess," a form sometimes conceived of as an emanation of Siva, as his "Sakti," and sometimes as an independent divinity having many names and forms. The word "Sakti" is often also used in Bhaktapur to refer to the consort, the female companion, of a male god. In this sense it means little more than wife, constant companion, or lover. There is a sharp distinction in cultural definition, personal meaning, and associated religious action between those ordinary goddesses who are the consorts of ordinary gods and important foci of ordinary religion, and those other goddesses, emanations of Siva or aspects of some form of

the Tantric goddess, the Saktis par excellence , the objects of Tantric worship.

The three ordinary goddesses are Laksmi, Sarasvati, and Parvati. Of these, only Sarasvati has her own temples. Laksmi and Parvati are respectively represented m the temples of Visnu[*] and his avatar s (with the consort of the particular avatar being sometimes considered an incarnation of Laksmi) and of Siva in his anthropomorphic forms. In contradistinction to Sarasvati and to the Tantric goddesses, they are secondary figures in the external city religion. Their abode and realm is in the household.

Sarasvati (Sasu Dya: Sasu God, in Newari) has four major shrines in Bhaktapur. These shrines may be worshiped as a personal act of devotion by local people and passersby, but her main special meaning is as the goddess of learning, to whom all people who are engaged in studies of one kind or another (in recent times particularly modern school studies) come to pray. Sarasvati can grant them effectiveness or siddhi in learning, as Ganesa[*] does to children for walking or talking. Her main temple is just to the south of the city across the river. All school children go to this shrine, the Nila (Blue) Sarasvati on the same day, or Sri Pa(n)cami, once a year (chap. 14). Sarasvati is usually represented in an ordinary, if idealized, human form, like the other ordinary goddesses (identifiable by her swan vehicle and her "lute," the vina[*] ). She was formerly embodied in all books, and now still in those that are not specifically modern and secular. In a major Puranic[*] tradition Sarasvati is considered as the daughter and sometimes the consort of the god Brahma. In Bhaktapur she is conceived of as an independent goddess.[17]

Laksmi (Newari, Lachimi) is a major household divinity, but she has no public shrine or temple, although she is understood to be present in Visnu's[*] temples as his consort, or as incarnated as Radha or Sita, the consorts of his major avatar s. She is understood to be nevertheless a goddess in herself, although she has in Tantrism some theoretical and cultic connections with goddesses such as Vaisnavi[*] and Varahi through shared associations with Visnu[*] . As everywhere in South Asia, as a household goddess, Laksmi is the promoter of the proper ends of the household—fertility, success in the household's economic activities, accumulation of food and wealth. She is the object of daily prayer and must never be neglected. She, like Visnu[*] , is a protector of ordinary life. She has one annual festival in Bhaktapur, which is during one day in the course of the five-day lunar New Year festival (chap. 13).

With Parvati (Newari, Parvati or Parbati) we approach the complex

web of ideas joining Siva, Sakti, and Newar Tantrism. Although Parvati is, as we shall see, one bridge to these ideas, she is for the most part an independent Goddess in her own right, one who belongs firmly to the ordinary realm. Parvati as a household figure is Siva's loving bride—the ideal wife—and the daughter of Himalaya, the personified mountain range. As Himalaya's daughter, the Kathmandu Valley, that is, the traditional Nepal of the Newars, is her paternal homeland, and she has special concerns with it, particularly with its Newar women. Like Laksmi, Parvati has no independent external representation in her own shrine, nor any external ritual significance for the public city.[18] She is a focus of some romantic fantasy (as is Krsna's[*] consort Radha in other parts of South Asia), represents married romantic love for the household, and is prayed to by women for the welfare of the household (with perhaps a less material emphasis than Laksmi) and for the birth of sons. Although she may change into dangerous forms in the legends of the Goddess she, like Siva when he emits his Sakti, is lost in the form, and (as we shall see below, as the Devi Mahatmya , one of the main sources of Bhaktapur's ideas and imagery about the Goddess suggests) is unaware that she has an alternate wild and demonic state.

The Transition to the Dangerous Divinities

The dangerous deities, which we are now ready to discuss, are in many contexts and for many purposes considered as independent deities. The "Goddess" who in some contexts is thought to derive from Siva, in others is not only independent and self-created but also usurps his role as the creator deity. For certain purposes in Shaivite and Tantric Bhaktapur, however, Siva is considered as their source. One aspect of this idea is related to the conception of Siva/Sakti, which is of basic importance in Tantric theory (chap. 9). Sometimes Siva is thought to transform himself into another god, such as Bhimasena. Sometimes Siva is thought to be first transformed into his dangerous form Bhairava, who may then, in turn, generate other dangerous gods. Siva's transformation into Bhairava is described as not a transformation of himself, but rather as a sending out of a force or power from within himself, an emanation, a ni:saran . Emanation is also the way in which the dangerous goddesses are said to be generated, as Siva is conceived as generating a powerful form of the goddess, who then, in turn, generates or is transformed into subsidiary forms.

We are now concerned with relations of a different kind than those that obtain between the "ordinary" gods. Those were familiar and relatively fixed social relations: spouse, child, friend. These relations are relations of metamorphosis and emanation and are often shadowy and uncanny. Their proper worship, uses, and meanings differ from those of the ordinary deities. They belong to a different realm of the world and of the mind.

Major Gods: The "Dangerous" Deities

The major divinities that we are categorizing as "dangerous" have many features of representation, conception, and usage, that separate them from the residue of "ordinary" gods. We have borrowed a salient Newari verbal distinction where when it is necessary to refer to the set as a whole they are refered to as gya(n)pugu , "dangerous." When such distinctions are necessary, the "nondangerous" divinities are often distinguished from the gya(n)pugu ones by one or another term for "ordinary," such as the Sanskritic term sadharan .[19] The contrast between the two sets, "ordinary" and "dangerous," responds to, reflects, and helps create important distinctions and complementarities. As we will see throughout this study, the two sets of deities are related to distinctions of inside and outside, of morality and power, of Brahmans and kings, of civil logic and dream logic, and of realms in which purity and pollution create distinctions and those within which they are irrelevant—in short, to some of the fundamental distinctions in Bhaktapur's conceptual world. The two sets not only represent these tensions and contrasts, they can be used to show relations of various sorts among them.

There are many more or less concrete markers of the contrast between the two sets of deities, their appearance, positions in the city, associated myths and legends. Some of these markers might (extremely rarely) be ambiguous; a benign deity may, for example, have a horrible form (such as Visnu's[*]avatar Narasimha[*] ). But there is one differentiating sign that people are forced to pay attention to, and that ensures the proper classification of any of these deities that they may have to encounter. This is what they are to be offered in proper worship. The dangerous gods should be given animal flesh and alcoholic spirits,[20] the ordinary gods, (including Ganesa[*] in his non-Tantric aspect) must never be given such foods. In ordinary speech the emphasis is on the "deities who drink alcoholic spirits," rather than on their acceptance of meat.

Alcoholic spirits in this context are specially named, nya (n ) rather than the usual term aela .

We will begin our discussion with the dangerous female divinities. Among the ordinary gods, the male gods are central and predominant and the female goddesses are peripheral to them; among the dangerous gods, the female divinities are predominant in quantity, complexity, and centrality in symbolic action.

The Dangerous Goddess and Her Transformations

Among the community of ordinary divinities are female divinities, various "ordinary goddesses" including Siva's consort Parvati. However, South Asia has had goddesses of a different sort who separate and coalesce in the course of history, in the course of individual mythic accounts, and in the conception and action of Bhaktapur. The coalesced figure is the Goddess, whose names, aspects, forms, and allies in Bhaktapur we will sketch in the following sections. In her most powerful and dangerous form as depicted in the Markandeya Purana[*] , a scripture that contains one of the major sources of Bhaktapur's imagery of the Goddess (P. K. Sharma 1974, 46 [emphasis added]):

She is a goddess warrior, incarnating herself on earth by using various devices at various crucial moments m order to destory the demons who were formidable challenges to the denizens of heaven. Indeed, in her perfect nature, she has been described as the most beneficent; but her fierceness as a martial goddess, equipped with the sharpest weapons and reveling in her terror-striking war-cries, is definitely a different tradition from that of Parvati-Uma, whom we always find fir an altogether different setting .

The goddesses whom this goddess spawns or is ready to absorb are often represented as similar to the "formidable" demonic forms that they oppose, a similarity that helps explain their effectiveness in combating them. In some conceptions, such as the legends associated with the Nine Durgas (chap. 15), it is clear that the dangerous deities are sometimes, in fact, demonic entities that have been captured by "magical" power, often by some expert in Tantric spells, and then eventually forced into the service of the human community. As such, they may have fangs, cadaverous sunken cheeks and bodies, garlands of skulls or decapitated human heads around their necks, or cloaks of flayed animal or human skins over their shoulders. They have multiple arms, bearing weapons and carrying a human calvarium as a drinking cup, understood to be full of blood. Sometimes they are represented as beautiful, full-

breasted figures of an almost hallucinatory sexual desirability, but the many arms of these representations bear the same murderous weapons as the frankly horrible forms, and like those forms, they, too, demand blood sacrifice. The beautiful forms are simply another manifestation of the same dangerous kind of goddess.

There are at least twenty-five major temples and shrines devoted to these goddesses, who have eleven major forms and a number of minor ones, all systematically related in a number of conceptual schemes activated in various contexts. Classification is complicated in that the same manifest goddess may have different names (as do most important Hindu gods), and conversely by the fact that the same name (Mahakali, for example) may represent different aspects of the Goddess in different contexts. The goddesses' main usages in Bhaktapur's civic religion may be divided into four interrelated emphases, each with its centers, members, and ritual forms and each with its particular major implications for Bhaktapur's civic organization. We will designate them as (1) the goddesses of the mandalic[*] system, (2) the goddesses of the Nine Durgas' annual dance cycle, (3) the generalized protective goddess usually referred to as Bhagavati, and (4) the political goddess Taleju and her related goddesses. Some individual goddesses, or at least some individual names of goddesses, may belong to more than one set, but much of their significance is largely determined by their membership in the particular set under consideration.

Each group of goddesses has a central member who represents a maximum concentration of what we may term "potential power." This goddess form is most general, full, and abstract. When there are other goddesses around her, they are more limited. Their manifestations, functions, and power are more shaped to the concrete needs of a particular event, a subsection of space, a particular set of ritual and symbolic functions. They are less omnipotential; they do some specific work in the world.

The Mandalic[*] Goddesses

In the previous chapter we introduced the eight goddesses who protect the boundaries of Bhaktapur while also each one having a special segment of the city under her protection—the city being divided for this purpose into eight peripheral octants and a central circle with its own, a ninth, protective goddess (see maps 1 and 2 above). These goddesses protect the city, in the words of one humble citizen, from "ghosts, evil

spirits and diseases like cholera." Others add earthquakes, invasions, destructive weather, and other disasters. As do all the dangerous gods, these goddesses protect the city against those external disorders that threaten the ongoing life of the city. That ongoing life has within itself its own protective resources, resources that may most generally be thought of as "moral." We have discussed these goddesses in relation to space, here we will, with some overlap, consider them as members of the pantheon.

The eight peripheral goddesses are often referred to in Bhaktapur as the Astamatrkas[*] , the "Eight Mothers."[21] In less elegant Newari they are sometimes called the pigandya: ,[22] the group (gana[*] ) of gods (dya: ) living in the pitha , a special sort of open shrine. The ninth goddess at the center of the city when it is conceived as a mandala[*] , is included or not in the set, depending on whether the emphais is on the outer protective boundary or on the internal space that is being protected.

The eight goddesses at the periphery have each the same basic function in her proper space, although some have additional specialized functions. They are, to introduce an important classificatory principle for the dangerous gods, all at the same level. The goddess at the center has the same protective function as the peripheral goddesses for her central mandalic[*] section, but in addition, as we have noted in chapter 7, she concentrates their individual powers in an eightfold increase at the center of the mandala[*] . She is thus, in this way, something more than any of them separately, she is at a higher level. This contrast is reflected in the traditional characteristics of the particular goddesses chosen for placement at the center and at the periphery. The central goddess, Tripurasundari, is (in contrast to the peripheral goddesses) not one of those goddesses designated as "mothers," matrka[*] s, in the Hindu Puranic[*] tradition. As we will see (below here and chap. 15), the legends and scriptural accounts of the Matrkas that are significant in Bhaktapur (and elsewhere in South Asia) treat the Matrkas as components or limited or lesser aspects of some complete, full, maximal form of the goddess, often called "Devi." Tripurasundari is a version of that complete, omnipotential goddess, characterized in some of the Upanisads[*] (the Tripura Upanisad[*] and the Tripura Tapini Upanisad[*] ) as the "primeval embodiment of Sakti that gives birth to the world" (P. K. Sharma 1974, 21).

We will introduce the Mandalic[*] Goddesses in the order in which they are worshiped during the succeeding days of the autumn harvest festival of the Goddess, Mohani, an order that begins with the eastern goddess

(map 2), follows the boundary of the city in the auspicious clockwise processional direction, and proceeds on the ninth day to the central summating central shrine of Tripurasundari.[23] The goddess to the east, the first in the sequence, is Brahmani (Newari, Brahmayani); to the southeast, Mahesvari (Newari, Mahesvari); to the south, Kumari;[24] and to the southwest, Vaisnavi[*] (Newari Vaisnavi[*] , often written and pronounced "Baisnabi"). The goddess of this particular location is on one occasion during the year—the complex spring solar New Year festival, Biska:—taken to be a quite different goddess, Bhadrakali[*] . To the west is Varahi (Newari, Barahi:), to the northwest is Indrani[*] (Newari Indrayani:), to the north is Mahakali, and to the northeast is Mahalaksmi[*] (Newari Mahalachimi).

These peripheral goddesses are, with one only apparent substitution, familiar representatives of the various Puranic[*] sets of "mothers" (P. K. Sharma 1974, 234), but are for the most part connected in their membership and in the exact order in which they are arranged to a particular traditional Hindu text, which is the basis for much of Bhaktapur's imagery of the Goddess, the Devi Mahatmya . In the account of the Devi Mahatmya the Saktis, goddesses emitted from the various gods of the pantheon, either fight as assistants to the goddess Candika[*] , considered a transformation of Parvati, or become absorbed into her to augment her power.

In one passage of the Devi Mahatmya (VIII, 12-20), which we will discuss at some length below, the Saktis of various gods who come to join the full goddess, Devi, are listed in sequence. The first five goddesses in the protective ring formed by Bhaktapur's Astamatrkas[*] (starting with Brahmani to the east and proceeding in a clockwise direction), are arranged in the same sequence: Brahmani, Mahesvari, Kumari, Vaisnavi[*] , and Varahi. Bhaktapur leaves out the Devi Mahatmya 's sixth goddess (Narasimhi[*] ) and proceeds to its seventh, Indrani[*] . The Devi Mahatmya , like many of the Hindu sources, lists only seven mothers. Bhaktapur uses six of them and adds at the end two more, Mahakali and Mahalaksmi[*] , commonly listed members of the Matrkas as given in other Puranas[*] . Mahakali is also known in Bhaktapur as Camunda[*] , a form of the goddess in her most terrifying aspect who also appears in the Devi Mahatmya as an honorific title given to the goddess form Kali as the slayer of two powerful Asuras Chanda[*] and Munda[*] (Devi Mahatmya , VII, 25; Agrawala 1963, 101). Mahakali and Mahalaksmi[*] , among the Mandalic[*] Goddesses, are just two ordinary Matrka[*] , although in other uses of the Goddesses in Bhaktapur, Mahakali's asso-

ciation with Kali-Camunda[*] and some of the legendary attributes of Mahalaksmi[*] are given some special significance.[25]

Like several other divinities in Bhaktapur, the nine Mandalic[*] Goddesses have "houses," literally, dya che(n) or "god-houses" situated within the city (map 2). Portable images of the goddess are kept at these buildings, and daily puja s are held there, conducted by a Tantric temple priest, an acaju . These dya che(n) images are carried in various processions during the year, particularly during the course of the solar New Year festival, Biska: (see chap. 14). Sometimes there is worship by a group of worshipers in the god-house rather than the pitha shrine, if the participants wish to keep the ceremonies secret, as is often the case in Tantric worship.

However, the proper and usual seats of the worship of the Mandalic[*] Goddesses are their pitha s, open, roofless, imageless shrines, which are the mandalic[*] markers. The nine mandalic[*]pitha s are very vaguely associated with the idea of the Devi pitha s, the 108 places in South Asia where pieces of Siva's wife Sati fell to earth (cf. Banerjea 1956, 495n.; Mani 1975, 219). These places became sacred to the Goddess. While the mandalic[*]pitha s are associated only by some metaphorical extension with the Devi pitha s, for the Newars the important "true" Devi pitha is that of Guhyesvari[26] in the major Valley cult center Pasupatinatha, where in esoteric doctrine Sati's vagina fell to earth.[27] There is no esoteric connection between the Guhyesvsari Devi pitha and the mandalic[*]pitha s.

The mandalic[*]pitha , as we have noted, are the required foci of attention and worship for families during important rites of passage, and for the city as a whole during the course of the Mohani festival sequence.

The Nine Durgas

Historically in South Asia, various groups of dangerous goddesses have been grouped together as the Navadurga, the Nine Durgas (Banerjea 1974, 500n.; P. K. Sharma 1974, 231-233). Slusser has written that, "in practice . . . the Nepalese Naudurga [Navadurga] are synonymous with the Astamatrkas[*] , to which a variable ninth manifestation is joined to complete the set. Thus, when the Nepalese speak of the Naudurga, they in fact refer to the Astamatrkas[*] " (Slusser 1982, vol. 1, p. 322). This is not true for Bhaktapur, where the distinction is essential. There the Nine Durgas refer to a group of divinities, represented primarily as masks (see color illustrations) who possess the bodies of a group of

dancers during an annual sequence that each year begins at the harvest festival of Mohani and lasts for the following nine months. We will be concerned with this sequence at length in chapter 15. The Nine Durgas have close relations with the Mandalic[*] Goddesses, as they do with the other major forms of the goddess in Bhaktapur, but they have, as we will see, their own legends, meanings, membership, and iconography. Although they share some of the same names with the Astamatrkas[*] and some of their reference to the Devi Mahatmya they differ in the meanings of the deities common to both sets, in other of their members, in their legends, and in their uses.

The Nine Durgas group share seven members with the Astamatrkas[*] : Mahakali, Kumari, Varahi, Brahmani, Vaisnavi[*] , Indrani[*] , and Mahesvari.[28] Of these the last five have very subsidiary roles, and are peripheral to the main actions of the cycle. The group also includes the male divinities Ganesa[*] , Bhairava, and Seto Bhairava and the goddesses (often thought of, however, as a male and a female) Sima and Duma.[29]

These twelve deities are represented as masks, and are worn by the dancers who through possession become the gods they represent. There are also two other gods associated with the group of the Nine Durgas. One is Siva, who is represented as a small mask without eyeholes that is carried by one of the dancers. He is not present as a possessed dancer nor as a performing god. Finally the entire group of gods have their own god, whose portable image they worship. She is generally known as the Sipha goddess, after the red leaves of oleander (sipha ) placed as a garland around her metal image. She is known to religious specialists as Mahalaksmi[*] . Mahalaksmi[*] is one of the equally ranked peripheral goddesses of the Asttamatrkas[*] —although, as we have noted, she is not one of the Devi Mahatmya s "seven mothers"—and is placed in the eighth and last peripheral position. As the Nine Durgas' own goddess she is in a superior position to them, as Tripurasundari is to the Astamatrkas[*] represents the "full goddess"; the other performing members of the group are special manifestations. There is another important hierarchical distinction within the Nine Durgas. As we will see when we discuss them in detail, the predominant form In the group of mask-gods is Mahakali, the "Goddess" in her most frightening form. We will return to these hierarchical relations later.

The Nine Durgas, in contrast to the Mandalic[*] Goddesses, are characterized by movement (map 14 [below, chap. 15]). Their original home (chap. 15) was, in legend, a forest outside Bhaktapur. They have now, however, an elaborate temple-like god-house in the city. During

Map 14.

The sites for the sequential Nine Durgas dances dramas or pyakha(n)s within Bhaktapur throughout the year. The numbers

show the sequence in which the dances take place. Map courtesy of Niels Gutschow.

the nine months of their annual existence, the masks of the dancers and other ritual equipment are kept there when not in use in their sequential visits to the city's neighborhoods.

Taleju, Bhaktapur's Political Goddess

An integral part of Bhaktapur's Malla palace complex of buildings and courtyards[30] is the temple of the goddess Taleju. The temple is approached through an elaborately decorated outer "golden gate" leading from Laeku Square, and is built around a set of inner courtyards which are closed to non-Hindus.[31] Taleju was the lineage goddess of the Malla kings. As such, she was one of the many tutelary divinities of the bounded and nested units of which Bhaktapur is constructed, divinities chosen by individuals or "given them" by their guru s, lineage divinities, divinities of guthi and associations of various sorts, special thar deities, and so forth.

As the Malla king's lineage deity and located in his palace compound, Taleju became a dominant city deity as manifest in the various symbolic enactments centering on her temple, reaching a dramatic climax during the festival that most clearly and dramatically portrays the various aspects of the Goddess and their relations, the harvest festival Mohani. Taleju is the dominant goddess and, in fact, deity, of Bhaktapur in those contexts where the centrality of royal power is being emphasized. She has survived the replacement of the Malla dynasty by the Gorkhali Saha dynasty as, for Bhaktapur, a powerful symbolic representation of traditional Newar political forms and forces, one that persists alongside of the new symbols and realities of modern politics.

There are extensive legends about the introduction of Taleju into Bhaktapur combining aspects of history, myth, and explanatory speculation about local topography and about aspects of the symbolic enactments that are associated with Taleju. The sketch of a version of the story that follows is derived from a lengthy written version provided by a Bhaktapur Brahman who works as a public storyteller, and is based on his public stories. His account begins with a short summary statement situated within the secular realm, and having to do with power and politics. "The Sultan Gayasudin Tugalak," the account begins, "having gained power in Bengal, attacked the town of Simraun Gadh[*] . The king of Karnataka[*] , Harisimhadeva[*] , having been defeated by Gayasudin, ran away to Nepal with his soldiers and captured Bhaktapur from King Ananda Malla, who had been its ruler. Then Hari-

simhadeva[*] established the goddess Taleju in her [supernaturally determined] proper place in Bhaktapur. The place where the Goddess was ritually established is called the Mu Cuka [the main courtyard of the Taleju temple]. The goddess Taleju was brought by King Harisimhadeva[*] from Simraun Gadh[*] ."

Now the account abruptly shifts from legendary history to the mythic and epic realm of Hindu tradition. "Once the Yantra of Taleju had been kept in Indra's heaven. [The Yantra is the powerful mystic diagram that embodies the goddess in this account, and is the only way she is represented in this account aside from her appearance as an anthropomorphic form in dreams]. There the god Indra worshiped her properly [her proper worship is an issue in the account]." Now (to continue in a paraphrase of the account) Taleju was stolen from Indra by Meghanada, the son of Ravana[*] , the demon king of Lanka, in the course of Ravana's[*] attack on heaven. Taleju was taken to Lanka and worshiped there. When Ravana[*] was defeated in Lanka by Rama, the hero of the Ramayana , Rama took Taleju, in the form of her yantra , to Ayodhya, his capital in India. In time the goddess Taleju appeared to Rama in a dream and told him that be must throw the yantra in the river Sarayu, which flowed past Ayodhya because no one would worship and sacrifice properly to her after his approaching death. After five or six generations a descendant of Rama, King Nala, found Taleju's yantra in the water, and brought it to his palace, but he did not worship her properly (which would have been with blood sacrifice), and had to return her to the river. Subsequent kings of Ayodhya, Nala, Pururava, and Alarka, had the same experience, each finally returning her to the river. The kings of this dynasty, the Solar Dynasty, were finally defeated by the Mlechhas (non-Indo-Aryan barbarians).