Latin American Protest Songs

The polemic against rock music was not limited to Mexico but was becoming widely expressed throughout Latin America. Rock was regarded by many on the left as the direct manifestation of an imperialist strategy to depoliticize youth while fortifying transnational capitalist interests. This leftist critique emerged in the context of the nueva canción movement and a renaissance of folk and protest music generally. While its intellectual and artistic origins were rooted in the cultural politics of earlier periods, the New Song movement was semiofficially launched at a 1967 conference held in Havana, Cuba, titled "Encuentro de la Canción Protesta" (Gathering of Protest Song). Reflecting a category of music attuned to the revolutionary and social protest movements that were occurring throughout the continent, New Song—referred to as nueva trova in Cuba, but also canción política (political song), canción popular (popular song), canción comprometida (committed song), and other such terms elsewhere—incorporated musicians from across Latin America. Especially prominent were Pablo Milanés, Silvio Rodríguez, and Noel Nicola (Cuba), Víctor Jara, Violeta Parra, and the group Inti Illimani (Chile), Mercedes Sosa and Atahualpa Yupanqui (Argentina), Daniel Viglietti (Uruguay), and Amparo Ochoa and Los Folkloristas (Mexico).[108] This "countersong," as one author dubbed

it,[109] variously used or combined traditional musical repertoires from Latin America to back lyrics that explored political, philosophical, and sentimental themes. It was an eclectic genre of music whose songs "questioned North American imperialism, economic exploitation, social inequality, and cultural alienation, along with themes that proclaimed a free and just future."[110] Pan-American solidarity—not with, but against the United States—was implied, if not overtly stated, in many of these songs.

As nueva canción gained ascendancy, commercialized popular music, especially rock, was increasingly slandered for its associations with imperialism.[111] This was ironic, because rock (especially the Beatles) had influenced some New Song musicians, such as Silvio Rodríguez. Nonetheless, in the context of the politically charged early 1970s, when various regimes throughout Latin America were openly hostile toward the United States and faced attacks from right- and left-wing elements, mass culture was readily conflated with imperialist designs and influence.[112] The critique of rock in part focused on the links between electronic music and economic and technological dependencies, ideas expressed, for example, in a roundtable discussion of music, nationalism and imperialism organized in Cuba in early 1973. As one participant commented, "I'm not against electronic music, but one has to be conscious of the technological element that creates dependency.... In this sense, one has to stimulate a genuinely Latin American culture with the elements at our disposal. It's necessary to be conscious that a culture weak in its creation, imprecise in terms of its authenticity, is always an easy prisoner for whatever type of imperialist penetration."[113] The various manifestations of "imperialist penetration" were suggested by an earlier conference also held in Cuba. In the "Final Declaration of the Meeting of Latin American Music," musical traditions were likened to raw materials that must be protected from relationships of dependency with the metropolises: "As with other deeply rooted popular and nationalist expressions, but with particular emphasis on music for its importance as a link between us, the colonialist cultural penetration seeks to achieve not only the destruction of our own values and the imposition of those from without but also the extraction and distortion of the former in order to return them, [now] reprocessed and value-added, for the service of this penetration."[114]

A clear example of this process of "value-added" marketing, which at the same time pointed to the complicated processes of transnationalism, was the impact of Simon and Garfunkel's song "El Condor Pasa." The song, credited as an "arrangement of [an] 18th c. Peruvian folk melody" was popularized by the folk-rock duo through their highly successful album Bridge over Troubled Water (1970). (Re)exported to Latin America at the start of

the revival in folk-protest music, Simon and Garfunkel were, ironically, responsible at one level for the commercial success of Mexico's own resurgence in folk music. As Luz Lozano reflected, "I've thought for a long time, 'How did that folkloric thing get started?' And I would say that it was with that song ['El Condor Pasa']. Or at least, it contributed a lot. It was the image that we had of [Simon and Garfunkel]. It was more than just them, like a triangulation: them, the Andes, and here, us.... I didn't know the song before [they recorded it]. I think that after that, the [movement] started to emerge here."[115] In Mexico (as in Cuba, Chile, and Peru) the political regime directly and indirectly supported the New Song movement and a shift toward folkloric cultural expression generally. Institutionalized performance spaces that once restricted rock, or were off limits altogether (such as the Palacio de Bellas Artes), now welcomed national and foreign New Song and folk artists. In one example, the Venezuelan-born singer, Soledad Bravo, whose work was described by Excélsior as an "impassioned [reflection] of themes rooted in Latin American folklore," was invited to perform at the Poliforum Siqueiros in Mexico City, a recently opened fine arts space named for the once-imprisoned, communist muralist Alfaro Siqueiros.[116] At the same time, the early 1970s witnessed a proliferation of music cafés called peñas , which offered a space for live folk-music performance. Unlike the cafés cantantes of the mid-1960s or the later hoyos fonquis, the peñas did not face the threat of arbitrary closure. On the contrary, the Echeverría regime went out of its way to express its support for this shift toward Latin American folk and protest song. As Federico Arana explains, "there was a clear and convenient symbiosis" between the folk-protest singers and the regime. "The proof that [the performers] weren't dangerous for the government is that they were never censured and never lost the government's support" (see Figure 17).[117]

The most ideologically articulate of the Mexican performers popularized during this period was the group Los Folkloristas, who recorded on the Discos Pueblo label, which became an extension of the group itself. The chosen name of the recording label reflected its broader mission: "[To] [g]ive diffusion to folkloric music and all the new forms of Latin American song, in their most genuine representations, exempt of all concession to the dominant commercialism... [To] [o]ppose the mounting imperialist cultural penetration [with] the voice of our peoples, as a necessity for identification and affirmation."[118] While Los Folkloristas had been in existence since 1966, not until the context of the early 1970s did they gain widespread recognition. To this the state lent a direct hand by donating space previously occupied by the National Symphony for the founding of Discos

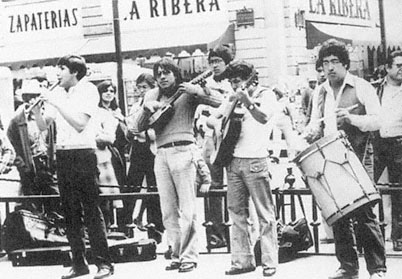

Figure 17.

With official sanctioning, folkloric groups such as this one popularized

the indigenous sounds of the Andes and other regions in the early 1970s. Source:

Federico Arana, Roqueros y folcloroides (Mexico City: Joaquín Mortiz, 1988), 48.

(Photograph by Olga Durón; reproduced courtesy of Federico Arana)

Pueblo and an indirect one by making concert halls such as the Palacio de Bellas Artes available for performances.[119] Moreover, when a scheduled concert at the National Auditorium was canceled at the last minute by capital-district authorities, President Echeverría intervened personally, stating: "It's very important to me that those young people perform." Echeverría then proposed an additional concert by the group in celebration of Teachers' Day (15 May), an event that was carried live by Telesistema.[120]

As one informant suggested, "One can see how things coincided: El Condor Pasa, the peñas, Los Folkloristas. I mean, they're a group that has been around for a long time. They had plenty of gigs, but they weren't popular. It took the impact of something foreign for them to become accepted."[121] While her statement perhaps overly credits the foreign impact of Simon and Garfunkel, the commercial success of "El Condor Pasa" was not overlooked by the group itself. Before each performance of the song Los Folk-loristas "would give this veiled indictment of the commercial forces that had prostituted that wonderful music—meaning, the Simon and Garfunkel thing."[122] Iván Zatz-Díaz, a fan of the folk and New Song movement, recounted: "This sound engineer [my neighbor] ... his contention was, 'Say

what you will, but these guys [Simon and Garfunkel] have made South American music a thousand times more popular than Los Folkloristas ever could. So what's so wrong with that? It's a wonderful version.' And so on and so forth. And I kind of agreed with it, to a certain degree. I still like the Simon and Garfunkel version of 'El Condor Pasa' very much."[123] The radical ideological stance taken by Los Folkloristas was directly extended in their opposition to rock music: "[We are] [p]ledged to spread the best music of our continent, [we are] dedicated to the youth of our country who have discovered their own music [canción ], [we are] opposing it to the colonizing assault and alienation of Rock and commercial Music,"[124] the group announced in a statement.

A confrontation in Peru in late 1971 neatly illustrated this process of rock's politicization and demonstrates perhaps a broader generalization of the Mexican phenomenon. At the time, Peru was in the grips of a nationalist, military-led government that had come to power in a coup in 1968 aimed at preempting guerrilla victory by implementing a radical, leftist policy agenda. Carlos Santana was scheduled to perform eight benefit concerts in Lima for victims of a 1970 earthquake. The rock group was met by 3,000 fans and an official greeting by the mayor of Lima, who "gave [the band] a scroll welcoming them to the city." However, the powerful student union at San Marcos University, where the concerts were to take place at an 80,000-seat soccer stadium, protested that the scheduled event was "an imperialist invasion." Two days before the opening performance, the stadium stage mysteriously burned to the ground. With that warning, the Ministry of the Interior canceled the tour altogether. The band had their luggage and instruments confiscated, and they were promptly ejected from the country, accused of "acting contrary to good taste and the moralizing objectives of the revolutionary government."[125] By comparison, the folk-protest song movement was openly backed by the Peruvian military regime, which actively sponsored performances and media diffusion for national and foreign artists through its National Institute of Culture.[126]

The ramifications of the surge in folk-protest song and the Mexican regime's support for this movement were not the total elimination of rock but rather the further class and cultural bifurcation of rock's reproduction and reception. Native rock, as we saw above, survived by going underground. As Simon Frith might claim, it returned to its working-class roots, where it was sustained into the 1980s.[127] Foreign rock, on the other hand, though dashed by the impact of disco, was reinscribed as vanguard culture among the middle and upper classes, who continued to purchase albums and stay attuned to transformations in the rock-music world. At the same time, La-

tin American folk music and nueva canción also found a wide reception among middle-class youth, especially among students.[128] As Luz Lozano explained, "[The music] said things more clearly. You knew more of the lyrics from the songs. You knew more about the situation of peasants, workers, and so you liked it more. But that didn't mean you stopped liking the other [rock]. But you related more to the social thing. Besides, it was the fad."[129] What was problematic about folk-protest music in part, however, was that it shifted the attention of protest away from the government and toward the more abstract (at times, less abstract) notion of imperialism generally. Furthermore, it reinforced a concept of cultural authenticity that played directly into populist rhetoric, even while serving to disseminate traditional folk music to a broader audience. Finally, live performances reinscribed the boundaries of respect and discipline between audience and performer that rock worked to undermine. "Even when they're helped out with their elaborate sound equipment," writes Federico Arana, "the folk performers demand silence and composure from their audience. For rockers, in contrast, the more intense the audience participation, the better."[130]

The polemic against cultural imperialism also served the Mexican regime in its efforts to derail the incipient class-based alliance that native rock had sought actively to forge. Among the middle and upper classes both nueva canción and foreign rock encountered a wide reception at the expense of native rock, música tropical, and Mexican baladistas, all of which became to a significant degree associated with the lumpen, naco classes. As Iván Zatz-Díaz recalled the cultural polemic that developed:

There were always [student] factions who would reject one form of music or another. For the bulk of us there was a lesser or greater degree of eclecticism, but it was there nonetheless. We did listen to rock, we did listen to folk music.... The only music that I poo-pooed, and most of us poo-pooed, were say the cumbias and the boleros. That kind of stuff was the music of the nacos. And God forbid we would be listening to naco music, you know. I guess it also became kind of a 'naco' thing to do to listen to Radio Mil [which played refritos]. So we stopped listening to the Spanish version. We would only listen to the original versions on Radio Exitos or La Pantera. That was really much more of a clash, if you will, than whether you were listening to the music of imperialism or not. Because that was still an open question. Was John Lennon a revolutionary force, or an imperialist force?[131]

Jaime Pontones, later an important rock disc jockey in Mexico City, spoke of "studying Marxism like crazy and listening to rock, not exactly in secret but in my home, because all of my friends didn't listen to rock anymore;

they [only] listened to Latin American Music."[132] In an interesting twist, rock in Spanish (that is, refritos) had become inverted from its former status as "high culture" during the early 1960s to become "low culture," or naco, by the 1970s.

But for all of folk and protest music's pretensions of working-class solidarity and peasant struggle in the triumph over the bourgeoisie and imperialism, the music was simply not that popular among lower-class urban youth. This was true even in the case of Chile, a central player in the birth of the New Song movement. One study, for example, concluded that the music was most popular among students, professionals, and state employees; whereas housewives, workers, and the unemployed demonstrated the lowest disposition toward its consumption.[133] In Mexico, student organizers came to discover that folk protest music was not sufficient for attracting large audiences at rallies. As José Enrique Pérez Cruz recalled of student-organized protests during the 1970s: "Sometimes at the rallies, as there wasn't always a heavy draw with protest music, they also invited rock bands. And for those rallies a lot of people definitely came."[134] Indeed, this reflected a deeper class antagonism that the native rock movement had sought to transcend. Ramón García spelled out the impact the New Song movement had on those from the lower classes: "[T] hat was what the students listened to." He continued:

They listened to that type of music, and so that's where the separation [in the movement] occurred. Because a lot of students also were part of the rock movement, but because rock made them feel special. Maybe it was what they needed, that is, freedom. But they weren't so oppressed. But then when all that protest music came, then the rockers, we stayed on one side, and those who listened to protest music were another class of people. But for the rockers, none of that mattered. Because really, the rhythm didn't interest us very much.[135]

By linking native rock to cultural imperialism, Echeverría hoped to coopt the middle-class, student element of the counterculture, promoting the folk-protest song movement as a Latin American "equivalent." In this way, Echeverría literally tried to nationalize La Onda by identifying cultural and social protest with a romanticized, unifying, anti-imperialist discourse. In this he seems to have been at least partially successful. This strategy undermined the mounting interclass alliance that was forming around La Onda Chicana, while marginalizing Mexican rock by driving it into the hoyos fonquis. Ironically, however, the quashing of La Onda Chicana in the name of combating cultural imperialism opened the way for foreign rock to establish itself as a dominant pop idiom. Thus by 1975 nueva canción, folk-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

protest, and foreign rock music all coexisted in commodified form, but the commercialization of native rock had virtually disappeared (see Table 2).

In retrospect, it appears that La Onda Chicana was destined to disappear, despite the moderate levels of support by the mass media and fans. Echeverría may have been willing to allow for a greater degree of expression under the terms of his apertura democrática, and perhaps he even viewed the channeling of youth energies toward the counterculture with optimism. But the backlash itself was inevitable. This was true for several reasons. For one thing, middle-class values were still overwhelmingly conservative, especially in the provinces and rural areas. The image of youth openly flaunting buenas costumbres was an affront to parental authority that struck at the heart of the patriarchal family. Second, intellectuals on the left also viewed the counterculture with alarm. While less concerned with the undermining of family values per se, they understood La Onda Chicana as the epitome of cultural imperialism. In a sense, it would have been difficult for them to see otherwise. Given the context of the times, "dropping out" of society suggested the clear imprint of U.S. influence. Finally, the folk-protest revival that was sweeping Latin America overwhelmed the appeal of native rock as vanguard culture, at least among the middle classes. Mexican rock had simply not yet achieved a high enough level of musical respect to assure it a competitive place among popular

tastes. (The arrival of disco, cumbia, and salsa music also contributed to the displacement of native rock.) Ironically, the principal supporters of La Onda Chicana seemed to be the mass media. But with the obvious political ramifications of continuing to promote Mexican rock after Avándaro, there was simply little reason for business executives to put their necks on the line. The market was not yet there. President Echeverría's strategy of repression, coupled with a discourse of cultural nationalism, was thus an ingenious means of responding to the crisis of legitimacy facing the PRI in the early 1970s. But Mexican rock had not disappeared as a wedge and mirror lodged within society. Left to ferment in the barrios, rock music would eventually rear its defiant head once more, only this time in the voice of the truly marginalized.