Chapter Six—

Modernism Reconsidered:

Style and Ideology in the Neoclassical Revival

The Diverse and protean style moderne, ranging from the Secession to the neo-Russian to austere rationalism, stimulated an equally protean reaction that embodied not simply a rejection of the style but an evolution of it. During the first decade of the century, the moderne was replaced by a renewed interest in historicism—in itself related to the neo-Russian variant of the moderne—as well as a vigorous revival of neoclassicism that, particularly in large commercial buildings, was often little more than an extension of the moderne with different stylistic markers. In the design of private houses, the neoclassical revival adhered more rigidly to the precepts of Russian neoclassicism (the Empire style) established during the 1820s and 1830s.

The neoclassical revival encompassed both artistic and intellectual life in the decade before the revolution. The Acmeist poets, for example, rejected the Symbolists, whose "decadent" aesthetic mannerisms are analogous to the early decorative motifs of the style moderne, which was also labeled decadent in Russia (see chapter 2). In music, moreover, Stravinsky and Prokofiev turned to the clarity and precision of classicism during this period. Although extensive comparisons of the arts would be misleading because of chronological and stylistic differences, Russian culture before the First World War included not only futurism and modernism but also an aestheticism, defined by its classical sympathies, that prevailed in several art forms—not the least of which was architecture.

The journal Apollon stood in the forefront of the neoclassical movement. It began to appear in 1909, edited by the poet and critic Sergei Makovskii. Although it was primarily a literary journal with a strong interest in the visual arts, in the very first issue Georgii Lukomskii characterized the new classicism in Moscow's architecture:

"Classical" tendencies in architecture have replaced the sinuously agitated, "temperamental," and riotously "dashing" modernistic efforts of architects like Kekushev, as well as the simplified structures faced with brilliant walls of yellow brick of architects like F. Shekhtel.

This is reassuring.[1]

By 1913 Apollon was publishing lengthy articles, copiously illustrated, on the neoclassical revival and its ideological significance. It defended the revived classical form in Russian architecture as an expression of nobility and grandeur opposed to the questionable (bourgeois) values of the new style.

The neoclassical revival in Russia began just when the style moderne had entered its most productive phase.[2] In view of the rapid shifts in architectural style at the beginning of the century, it is not surprising to find that the architect responsible for reappraising the

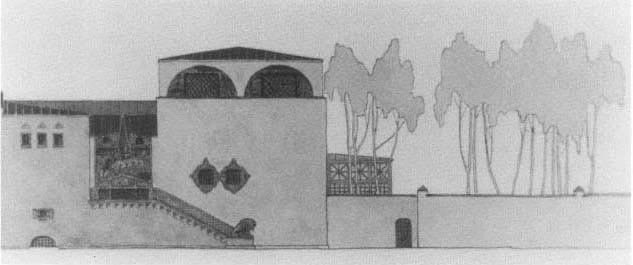

Russian Empire style was Ivan Fomin (1872–1936), one of the most gifted young architects and designers in the style moderne and an assistant to Fedor Shekhtel. Fomin's paripatetic career, like that of many of his contemporaries, was influenced by political events, such as student protests and disturbances in Petersburg's institutes of higher education. After one such incident in 1896 Fomin interrupted the studies he had begun at the Academy of Arts in 1894; he spent a year in France and returned to Moscow as an architectural assistant. His architectural mentors at the turn of the century included Kekushev and Shekhtel, a discerning judge of ability who recommended Fomin to Ilia Bondarenko for work on the Russian pavilion in Paris (1900).[3] Fomin also helped to design the interior of the Moscow Art Theater and both organized and contributed to the Moscow exhibit of architecture and the decorative arts in the new style (December 1902-January 1903).[4] His sketches for designs of houses in the modern style were considered brilliant: one was reproduced in the Zodchii article "Contemporary Moscow" (1904); others appeared in the Moscow and Petersburg architectural annuals, which included Fomin's work in almost every issue (Fig. 253).

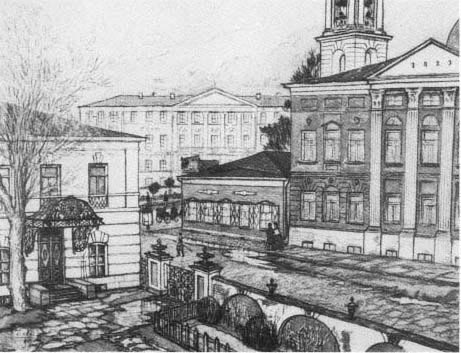

His work in the new style remained almost entirely on paper, with notable exceptions such as his furniture designs for the 1902 Moscow exhibit (discussed in chapter 2). Because of his interrupted education, he had no architectural degree or certificate at the beginning of the century, and his sketches of modern houses were incomprehensible to contemporary Moscovites. Fomin had gone beyond the moderne without participating in the movement; but his attention was soon redirected. In 1902 Aleksandr Benois published "Picturesque Petersburg" in Mir iskusstva , on the need to resurrect Petersburg's neoclassical architectural heritage. The article provoked a furious response from the modernist Pavel Makarov (see chapter 2); and, as Makarov had feared, the article had contemporary ramifications beyond the preservation of architectural monuments.

In 1903 Fomin entered a design competition for a country house in the classical style on the estate of P. P. Volkonskii. Although Fomin's modernized interpretation of classical elements was unlike his neoclassical work to come, he was already at the point of abandoning the style moderne (Fig. 254). In 1904 he published his own panegyric to the neoclassical architecture of Moscow. His emotional description deliberately opposed the rationalism of modern architecture:

The poetry of the past! An echo of the inspired moments of the old masters! Not everyone can understand the feeling of sadness at the faded beauty of the past, which at times gives way to an involuntary thrill before the grandiose monuments of architecture, Egyptian in their force and combining strength with the delicacy of noble, truly aristocratic forms.

. . . multi-storied buildings are already replacing these amazing structures from the epoch of Catherine II and Alexander I. Because so few of them remain, they are all the more valuable; I love them all the more.[5]

Fomin's article was accompanied by excellent photographs, but as a brilliant draftsman he himself sketched Moscow's neoclassical monuments and reproduced them in a series of postcards. The success of this venture and the critical acclaim of his article led him to write more extensive essays on the history of Russian neoclassicism after he completed his formal architectural training. He returned in the fall of 1905 to the Academy of Arts, where he was accepted for advanced study in the architectural studio of Leontii Benois. Benois played a major role in the career of many Petersburg architects, including some of the most talented representatives of the style moderne; but Fomin may have found Benois's classical-Renaissance sympathies especially congenial, for he had moved irrevocably into a period of neoclassical aestheticism.

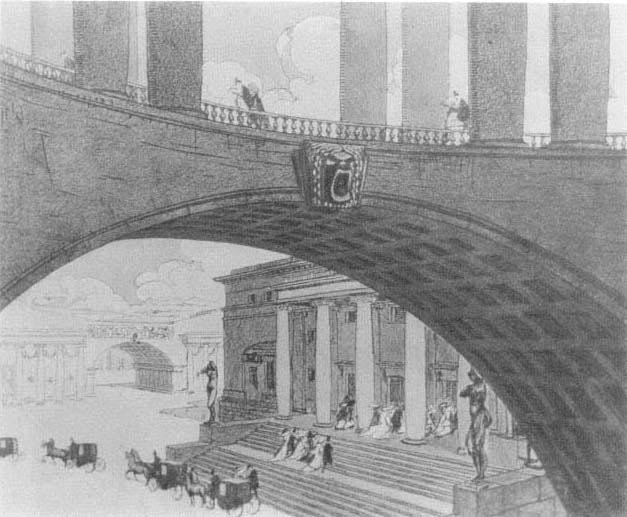

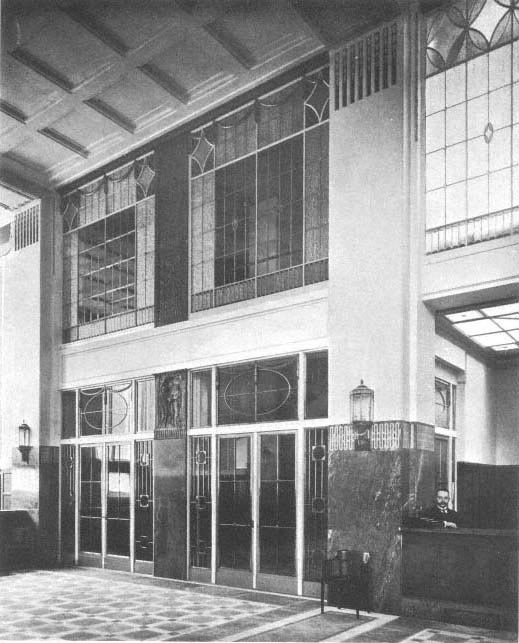

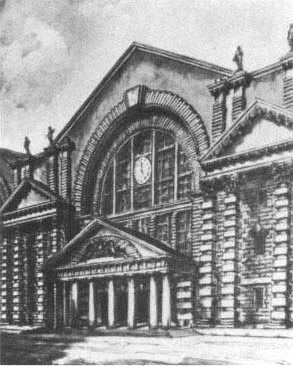

The results of this shift appeared in Fomin's masterful student sketches, including his 1909 diploma project for a resort or mineral baths (kurzal ) on a heroic scale (Fig. 255). On a more practical level, Fomin designed a series of rooms for the apartment of the Pomer family on Vasilevskii Island. His treatment of structure and contour was modern, but the classical details, clarity of outline, and symmetry of the furniture ensembles (all painted white) demonstrated a classical sensibility (Fig. 256).

More significant was Fomin's participation in preparing an exhibit for the Petersburg Society of Civil Engineers that was to survey Russian architecture during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The scholarly and archival work involved proved overwhelming, and the exhibit, originally scheduled for 1908, did not open until 1911. In 1908, however, Fomin published a statement of the exhibit's purposes in what had become his preferred journal, Starye gody (Bygone years).[6] He explained

Fig. 253.

Project sketch for an artist's house. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1906.

Fig. 254.

Project sketch for house of Prince Volkonskii. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1906.

Fig. 255.

Project sketch for a resort. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1909.

confidently that the exhibit would help to overcome the neglect of post-Petrine architecture and argued that modern architecture lacked some essential force present in even the work of less distinguished artists from the neoclassical era:

[Their work] characterizes the epoch even more than the work of first-class artists. In it one grasps the basis, the elements that are the essence of the style. . . . When the style was being formed, all the masters in the capital and the provinces worked toward the same end, not fearing to imitate one another. And in this is the guarantee of strength.

In our time, on the contrary, everyone scurries about trying to be individual; everyone wants to invent "his own," to do things deliberately not like others. As a result, there is no reigning style, nor does one see even those guides (vozhaki ) who might in the future stand at the head of a movement deserving expression as something new.[7]

Fomin thus established a tone that would underlie all further ideological claims on behalf of the neoclassical revival. Rather than shapeless individuality, neoclassicism provided the nobility of an immutable idea to be shared by all. The totalitarian implications of this thought were then far removed from his thinking, but

Fig. 256.

Interior design for Pomer apartment, Petersburg. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestvat

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1908.

Makarov sensed that the new style threatened individualism, even as he underestimated the appeal of a return to classical forms. The "unifying idea" loudly called for at end-of-the-century architectural congresses was about to be expressed in a form that no congress participant would have dared suggest: neoclassicism.

In the spring of 1909 Fomin won the graduation prize at the academy and was awarded a year's travel abroad, which he spent, not surprisingly, in Greece, Italy, and Egypt. On returning in 1910, he continued as chairman of the committee for the architectural exhibition, which opened at the Academy of Arts in March 1911. The display of architectural drawings and models from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was not an end in itself, however; the research findings that underlay the enterprise were published or preserved in museum collections. The most important publication was Fomin's own survey of Petersburg neoclassicism in the multivolumed History of Russian Art , edited by Igor Grabar.[8]

By 1911 the reappraisal of neoclassicism had been generally accepted, largely through Fomin's efforts. The return to the classical model in the architecture of Petersburg and Moscow, however, had variant forms. Accord-

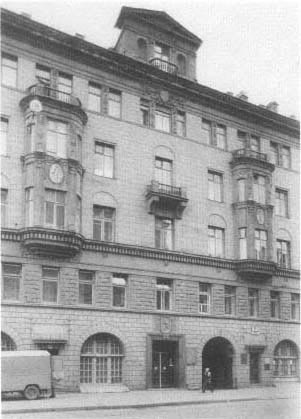

Fig. 257.

Second Mutual Credit Society building, Petersburg.

1907–1908. Fedor Lidval. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1909.

ing to one interpretation, it first appeared as a modification and outgrowth of the style moderne; in a second phase it followed prototypes from the Italian Renaissance and Russian neoclassicism of the early nineteenth century.[9] But both stylization and modernized adaptation characterized neoklassitsizm throughout the decade 1905–1915, when it developed as an extension of modernism, an expression of nostalgia for bygone cultural values, and a reformulated sense of imperial monumentality on a modern urban scale.

As noted in chapter 5, Petersburg was especially receptive to the classical orders in its commercial architecture based on structural principles that had first appeared in the moderne. The design by Virrikh, Krichinskii, and Vasilev for the emporium of the Guards' Economic Society (see Figs. 234–236), for example, integrated classical elements into one of the city's most advanced functional commercial structures. Nikolai Vasilev, once a practitioner of the flamboyant style moderne, explored a simplified, modernized form of classical tectonics even more radically in projects like the passage on Liteinyi Prospekt (1911–1913) and the Noblemen's Assembly (see Figs. 237, 238).

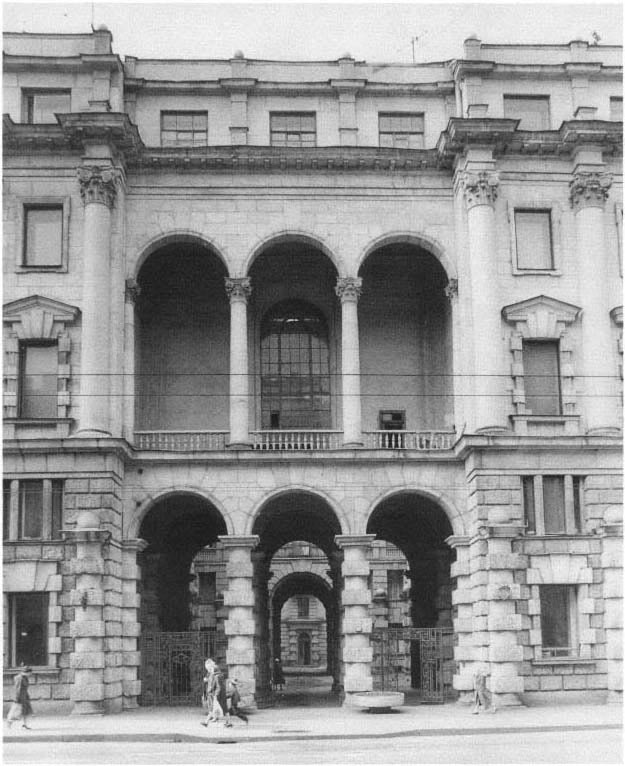

Fedor Lidval, who became a leading practitioner of the neoclassical revival, built two banks in the style between 1907 and 1909. Although the one for the Second Mutual Credit Society (1907–1908) on Sadovaia Street is the more austere of the two, its design is richly articulated, from its three open bays on the ground level, whose massive piers establish visual support for the upper stories (Fig. 257), to the dark rusticated blocks of the central stories and the central window shaft, surmounted by the light granite ashlar blocks of an undecorated pediment.

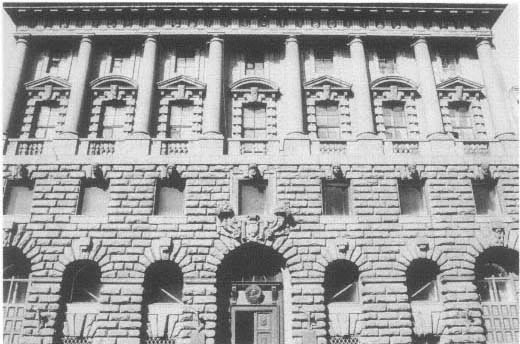

Lidval's Azov-Don Bank (1908–1909) has a larger and more complex facade, centered on four three-storied Ionic columns that frame the central banking hall (Fig. 258). Above the columns, rectangular windows, without mullions, are separated by oval medallions carved in relief by the sculptor Vasilii Kuznetsov, who also created the frieze of laborers on the lower level.[10] In both banks Lidval exploited the texture and color of granite as well as the sculptural qualities of natural stone in the decoration of the facade, and in both he used iron structural components in the large transaction halls (Fig. 259).

Lidval applied modern construction methods to clas-

Fig. 258.

Azov-Don Bank, Petersburg. 1908–1909. Fedor Lidval (Brumfield L-50).

sical architectonics to suggest the solidity and strength of major financial institutions. Georgii Lukomskii was quick to see the implications of Lidval's work. In his commentary in the first issue of Apollon , he noted the transition in Petersburg from buildings too light for their environment (Lidval's early apartment buildings) to monumental structures appropriate to an imperial capital—structures like the Azov-Don Bank:

Though fashioned in the style of our "Empire," this building is, by virtue of its material and the very articulation of the stone surface, more harsh in its lines, more "foreign" in its forms. Its style approaches that of buildings of the German "Empire" (theaters in Leipzig and Danzig), while in the resolution of structure it is [closer] to the Swedish-Finnish "new" type of building (banks in Stockholm and Helsingfors).[11]

The reference to Helsingfors is especially apposite in view of the publicity given the designs of financial institutions by Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen as well as other Finnish architects. Although such designs had little to do with neoclassicism, the use of natural stone by these architects anticipated a development in Petersburg. Lukomskii noted that the extension of railway lines to quarries in Russia and the lowering of tariffs for transporting stone provided an abundance of "material for the facing of structures in the capital." Although the use of natural stone militated against the richness of detail and form characteristic of Petersburg's Alexandrine neoclassicism—or Empire style—with its intricate stucco detailing, Lukomskii found compensations in the unmistakable "monumentality" of Lidval's Empire colonnade on the Azov-Don Bank.

To be sure, the new classical style had entered the service of an empire of commerce; Lukomskii commented on this fundamental shift in economic power. The Azov-Don Bank had "none of the 'nobility' of our Empire structures" because "the goal of a bank—a bourgeois palace—excludes it."[12] Lukomskii was less ambivalent in appraising the building of the Second Credit Society, whose subtler relation of parts suggests the genius of Russian neoclassicism in its final phase. Even without "noble perfection" Lidval's adaptation of neoclassical elements promised the new approach to architecture Lukomskii fervently desired: "Lidval's structures are the

Fig. 259.

Azov-Don Bank, interior. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1909.

Fig. 260.

Siberian Trade Bank, Petersburg. 1909–1910. Boris Girshovich (Brumfield L78-29).

type that, in all likelihood, will harmonize the 'new' construction with the principles and traditions of historical architecture in Petersburg."[13]

Lukomskii's essay on Lidval's work, with its carefully chosen, superbly reproduced photographs, helped to disseminate the aesthetic principles of the neoclassical revival. Other commentary followed rapidly as the style matured; but Lidval was among the first to meld rational structural innovation and the aesthetics of monumental architecture.

Lidval was not the first architect to design new banking space in Petersburg: in 1896–1898 Boris Girshovich had constructed the Azov Commercial Bank at No. 62 Nevskii Prospekt; and in 1897–1898 Stanislav Brzhovskii, the architect of the Vitebsk Railway Station, built the International Commercial Bank at No. 58 Nevskii Prospekt. In 1898 Leontii Benois reconstructed a building for the Volga-Kama Bank (No. 38 Nevskii Prospekt, rebuilt in 1948 with its earlier neoclassical facade); and in 1901–1902 he designed the Moscow Mercantile Bank (No. 46 Nevskii Prospekt) in the eclectic Renaissance style that characterized his work at the turn of the century.[14] Indeed, with minor variations, these bank buildings had the eclectic stuccoed facades typical of Petersburg architecture after 1850. The only significant use of a stone facade in the central district at the beginning of this century was Karl Shmidt's design for the Fabergé building.

Lidval's example rapidly changed that situation. In 1909–1910 Girshovich built the Siberian Trade Bank (No. 44 Nevskii Prospekt), which closely resembles Lidval's work, with its gray facade of granite ashlar and its modernized reference to classical motifs (Fig. 260).[15] Instead of Lidval's strongly centered approach, Girshovich's facade has a row of Corinthian pilasters stretched across it. The pilasters and the three-storied window shafts

Fig. 261.

Salamander Insurance Company building, Petersburg.

1908–1909. Marian Peretiatkovich, Nikolai Verevkin

(Brumfield L61-11).

give a vertical accent to the building; but horizontality predominates in Petersburg: the large cornice (originally with the name of the bank) limits the vertical development and provides a base for the top floor, decorated, in the manner of the Azov-Don Bank, with panels containing classical urns in high relief. The urns separate the plain rectangular windows without mullions (another device introduced by Lidval). Beneath the capped pediment, Girshovich, subtly quoting Lidval, placed a fan window with neoclassical tracery flanked by classical nudes. The contorted nudes seem to parody the heroic frieze of the Azov-Don Bank, and suggest a mannered play both on the decorative elements of the neoclassical era and on their revival.

From 1910 to 1914, when virtually every major Petersburg bank constructed new headquarters, the dominant presence in bank construction was Marian Peretiatkovich (another of Leontii Benois's many pupils), who approached classical monumentality through the Italian Renaissance.[16] In 1908–1909, with Nikolai Verevkin, he designed a building for the Salamander Insurance Company, with understated Renaissance motifs on a granite facade (Fig. 261). His unrestrained design for the Vavelberg Banking House (No. 7 Nevskii Prospekt), however, combined features of the Florentine quattrocento—such as the rusticated stone work of Michelozzo's Palazzo Medici—with the double arcade form of the Palace of the Doges in Venice (Fig. 262).

Because of its location at the corner of Nevskii Prospekt and Morskaia Street, the Vavelberg building can be seen in three dimensions. The architect's imitation of the palazzo style on the narrow facade included even the Medici coat of arms! The open arcade at ground level had been introduced by Shmidt in his Fabergé building, yet the grotesquely massive form of the Vavelberg building is unique—in sharp and obtrusive contrast to the great imperial monuments at the head of Nevskii Prospekt.

In Peretiatkovich's subsequent design for the Russian Bank of Trade and Commerce (1912–1914) on Morskaia Street, the references to the Renaissance palazzo reappear on the heavily rusticated granite surface; but

Fig. 262.

Vavelberg building, Petersburg. 1910–1912. Marian Peretiatkovich (Brumfield L84-19).

the narrow site gives greater focus to the facade, which ascends to a Doric portico enclosing the upper two stories (Fig. 263). This design, with its sense of proportion, was the most successful product of the architect's fascination with Italian architecture, which he had studied closely in 1906. He modified the style in the large City Institutions Building (1912–1913), whose facade shows elements of the palazzo but is defined by end blocks and a central tower that suggest such monuments of Petersburg neoclassicism as the Admiralty (Fig. 264).

Despite the professionalism of Petersburg's neoclassical revivalists, their work often reflects the tension between monumentality and the functional requirements of modern architectural design. These contradictions were ably noted by Marian Lialevich, the designer of the Mertens Building on Nevskii Prospekt (see chapter 5), who frequently collaborated with Peretiatkovich on neoclassical projects but who also acknowledged the significant innovations of the style moderne. Among his several publications, perhaps the most theoretically interesting was his response to "On Style and Pseudostyles," an article by the prominent critic and art historian Vasilii Kurbatov, published in 1908 in Zodchii . Kurbatov decried the pseudostyles that resulted from the "inability [of architects] to find new decorative and architectural forms as quickly as the conditions and demands of life change."[17] Despite their technical proficiency, architects had created no daring, aesthetically innovative style. Kurbatov hoped that an authentic style would develop in which social needs and technical innovations would merge; but his prognostications were either dogmatic—he insisted that "monumental" buildings should continue to be constructed of natural stone in the Roman manner—or simply misguided.

In response Lialevich defended nineteenth-century eclecticism: if life indeed creates the architecture suitable to its demands, there is no reason to posit preconditions for an appropriate style:

In linking the appearance of architectural forms with the qualities of steel and concrete, it seems that we so restrain our concept of the development

Fig. 263.

Russian Bank of Trade and Commerce, Petersburg. 1912–1914. Marian Peretiatkovich

(Brumfield L84-25).

Fig. 264.

City Institutions Building, Petersburg. 1912–1913. Marian Peretiatkovich,

Marian Lialevich.

Photograph ca. 1914.

of architecture as an art that we repeat the very mistakes we attribute to architect-theoreticians of the nineteenth century (Semper, Schinkel). . . .

A genuine style will appear not from the properties of steel and concrete but from more deeply based elements, from the strivings and ideals of society in the broadest sense [obshchestvennost ].[18]

Lialevich justified the style moderne as a "historical necessity," whose passing was entirely natural. The most important contribution of the moderne may have been its sense of freedom from normative, academic tendencies:

For the full reflection of life, art needs freedom. . . . It is horrible to think that after art had been able to spread its wings but had not defined the direction of flight, such [proscriptive] tendencies would force it back onto its academic course . . . Elevate the meaning of life—not by studying steel and concrete—and the work of human hands will change.[19]

After the revolution, Lialevich returned to his native Poland; but during his career in Russia at the beginning of the century, he worked in the style moderne and the neoclassical revival style as well as in a combination of the two. His response to Kurbatov implies a suspicion of the dogmatic aesthetic principles of classical, academic architecture. Fomin's comments in Starye gody that same year had advocated just such principles; and although his own work effectively interpreted these values, the architectural critics who promoted the neoclassical revival wrote in increasingly preemptory tones.

Despite the publicity given the neoclassical revival in commercial architecture, the style asserted itself most emphatically in Petersburg (and to a lesser extent in Moscow) in the design of apartment buildings. Lidval, once again, was at the forefront of stylistic change. Having defined the style moderne in apartment buildings at the beginning of the century, he was prepared to effect the transition to a style that placed less emphasis on texture and plasticity and borrowed elements from the classical era in Petersburg.

The first notable example was his reconstruction of an apartment house on the Moika Canal for the firm of the Nobel brothers (1909). The building is a model of restraint, in harmony with the scale and style of the adjoining structures in this historic central district of the city (Fig. 265). The neoclassical window pediments in alternating configurations on the first floor are the major decorative feature of the stuccoed facade; the undecorated ovals between the windows of the top floor refer discreetly to Petersburg neoclassicism.

Lidval exercised greater freedom in designing an apartment house on the Fontanka Quay for M. P. Tolstoi (1910–1912). The roughcast facade has a few understated motifs from the neoclassical and baroque styles (Fig. 266), but the building's form represents a "rationalist" development of the style moderne. Its dominant feature is the three-storied arch framing the entrance to the courtyards that lead to a street on the opposite side of the structure. The heroic entrance—unusual in Petersburg buildings—created a dynamic relation between the building and the streets on either side of it; the arches, with their flanking pilasters and obelisks, suggest the grandeur of Roman classicism. A similar approach characterized Lidval's design for the deluxe Hotel Astoria on St. Isaac's Square (1911–1912), a six-storied building with a few highly visible decorative elements, such as the classical urns and channeled pilasters along the austere granite facade.

In 1910–1912 Lidval designed an apartment house for E. L. Nobel—one of the Nobel brothers—at the eastern fringes of the city on Lesnoi Prospekt, across from a private residence Lidval had built for the same patron in 1910. The apartment building has the textural contrast of the style moderne, with rusticated stone on the ground level and roughcast on the upper floors, and the unadorned rectilinearity of modern functionalism. Classicism, however, reappears in the articulation of the large triple arch leading to the central courtyard.

The most ambitious application of classical elements in Petersburg apartment construction occurred on Golodai Island, a largely undeveloped area north of Vasilevskii Island across the narrow Smolenka River. In 1911 an English investment firm initiated a project, called New Petersburg, for a community to occupy much of the western part of the island (about 232,000 square sazhens).[20] The technical problems were considerable, since the low-lying area was subject to flooding and inadequately protected by a dike; with a special dredging and pumping system, the area was raised eight feet to the level of the dike with sand taken from the bottom of the Neva estuary. Because of the city's rapid growth, its

Fig. 265.

Nobel Brothers apartment house, Petersburg. 1909. Fedor Lidval

(Brumfield L86-6).

Fig. 266.

M. P. Tolstoi apartment house, Petersburg. 1910–1912. Fedor Lidval (Brumfield L40-9).

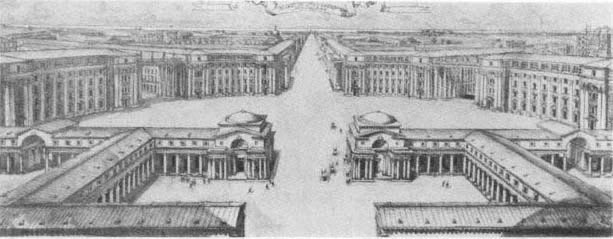

Fig. 267.

Sketch for New Petersburg (housing development on Golodai Island). Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1913.

dearth of housing and suitable land for construction, and the cramped and unhealthy environment of the central city, the entrepreneurs expected a good return despite the expense of improving the site.

The general design for the project was entrusted to Ivan Fomin, who had built relatively little but had established a reputation as one of the most capable of Petersburg's neoclassical architects. He had demonstrated his ability to think in large terms in his 1909 diploma project (see Fig. 255); the influence of that project is evident in the sketches for New Petersburg, with its Roman arches, colonnades, and receding horizontal vistas (Fig. 267). Fomin fully intended to re-create the monumentality of imperial Petersburg in a housing development for what might be called the city's new middle class. Paradoxically, Kurbatov, in "On Style and Pseudostyles," had defended classical monumentality for major buildings but rejected it for housing, predicting the development of single-family suburban dwellings on the model of the English housing estate.[21]

Kurbatov's prediction proved inaccurate, while Fomin's vision turned out to be prophetic of Soviet architecture in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as of Western postmodern developments of middle-class monumentality (notably the work of Ricardo Bofill near Paris). But little of the New Petersburg project was built. In 1912 Fomin undertook the construction of one of the five-storied apartment blocks whose facades were to follow the curve of the semicircular entrance park. The buildings made heroic reference to Roman architectural motifs (the Claudius Aqueduct), with a rusticated facade segmented by four-storied Corinthian pilasters and a fifth, attic, floor above the cornice. The buildings were to have been linked by colonnaded arches, beneath which the major radial streets of the development originated.[22] Although the radial arteries have been preserved, the only remnant of Fomin's work is the one apartment building, since adapted for use as a school.

Another component of the project consisted of housing blocks on the major thoroughfare leading to the entrance square from the east. Fedor Lidval designed these buildings in 1912. In praising the New Petersburg project, Georgii Lukomskii compared Lidval's undistinguished designs with the German regency style and with provincial architecture in Holland during the reign of Louis XIV. Such labored comparisons suggest an eagerness to welcome the revival of neoclassicism, which restored timeless architectural values and proved adaptable to changes in the contemporary social structure—even to housing the working class. In Lidval's apartment buildings (only one building was constructed), Lukomskii noted,

The channeled pilasters, extending the height of the building, and the modest decorations and shallowly outlined frames of the windows will suggest that these are apartment houses primarily for workers.

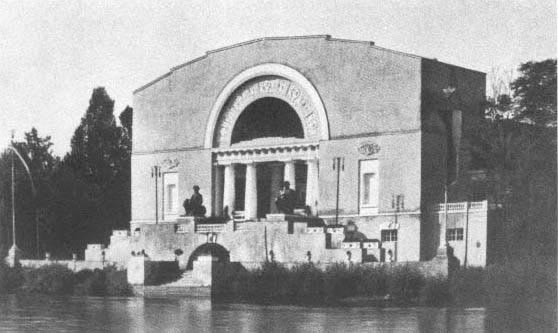

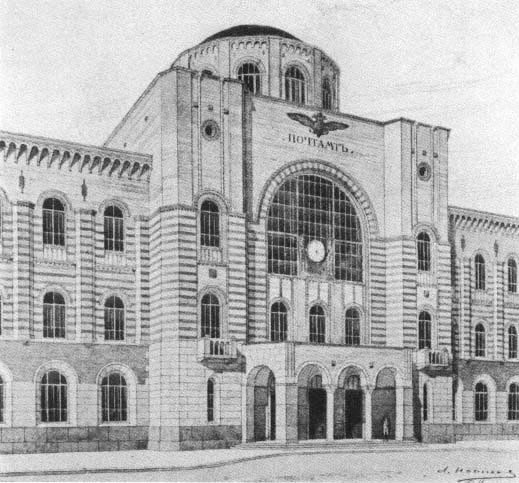

Fig. 268.

Project sketch for Nikolaevskii Station, Petersburg.

Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1912.

But not all the buildings planned for construction here will serve this goal. Once the second streetcar line reaches here, the more prosperous classes of Petersburg will flock to this part of town on the sea, with its open horizon.[23]

In the event, construction halted after the initial stages. Lukomskii's fervent support of the project reflected his desire for a "part of the city with a truly European appearance and a strict unity of classical architectural ensembles, situated on the shores of an open sea."[24] Whether reality could ever have matched the critic's vision, which included not only parks and seaside promenades but also tennis courts and soccer fields, is open to question. Even before the war, the project was impeded by the lack of transportation and other services to bring to the area the "more prosperous classes," on whom the investors depended for a return on their large outlay. In an ironic reversal, the completed fragments of the development were left primarily to the working class, presumably inured to primitive transportation.

Fig. 269.

Project sketch for Nikolaevskii Station. Ezhegodnik

Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1912.

When Fomin abandoned work on the New Petersburg project in 1913, he continued to devise neoclassical urban projects on a large scale, submitting a design for the rehabilitation of the area around Antonio Rinaldi's buildings for the Tuchkov Wharf (Tuchkov Buian, originally constructed in the 1760s).[25] Fomin had frequently used motifs from the work of Andrei Voronikhin, one of the greatest Russian architects at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The grand portico of Voronikhin's Institute of Mines, on the Neva embankment of Vasilevskii Island, figured in both Fomin's 1911 design for the competition to build a museum of the 1812 war and his project of 1912 to rebuild the city's main railway terminus, the Nikolaevskii (now Moscow) Station (Figs. 268, 269). The rusticity and scale of the three massive arched caverns in the project sketches suggest the work of Piranesi. Fomin did not win any of these competitions; nor did the projects themselves ever materialize. Almost all his completed work before the revolution consisted of private houses, of which more will be said later in this chapter.

Despite the failure of New Petersburg, the neoclassical revival style remained dominant in the design of apartment houses. New Petersburg may have lacked transportation, but the area along Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt had flourished since the beginning of the century, when the tramline appeared and Lidval completed his first major apartment complex. No comprehensive plan governed development, yet the buildings on the Prospekt and some intersecting streets shared an imposing scale and a look of prosperity unique to contemporary Petersburg; those of any distinction for the most part followed the neoclassical revival style. In 1913 Stepan Krichinskii, who had collaborated with Virrikh and Vasiliev on the building for the Guards' Economic Society and with Vasiliev on the Petersburg Mosque, built an imposing apartment house for the emir of Bukhara in the style of a Renaissance palazzo, with rustication on the ground floor and a triple arch for the entryway, which led to monumental courtyards (Fig. 270).

One of the largest apartment complexes on Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt was commissioned by the First Russian Insurance Company, which had already financed a number of such buildings in Petersburg and Moscow. The competition announcement stipulated the highest standards of comfort and hygiene. The apartments were to range in size from four rooms to twelve, with the majority between six and eight rooms; each was to have basic services (a kitchen, a pantry, a minimum of two water closets, a bathroom). In addition, the competition required living areas for servants, a garage area, and a laundry. Like the Pertsov apartment house in Moscow, this project encouraged the inclusion of artists' studios on the top floor. In stylistic terms the competition program specified that "the design of the building, on both exterior and interior, must be simple but refined and solid. The style of the so-called Decadence is not permitted."[26]

A group headed by Iulii and Leontii Benois submitted the winning entry, an imposing but conservative design that is the antithesis of decadence, or the style moderne. The Benois design centered on a large courtyard, open to the street (as required by the competition) and entered through a one-storied colonnade (Fig. 271). Lukomskii commented rhapsodically on the building's place in the ensemble of Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, which "gives hope that a part of the city really can be designed in the European manner."[27] Lukomskii had already expressed his wish that Petersburg attain the contemporary look of a modern, prosperous European city; such expressions belong to a sporadic preoccupation among Russian intellectuals with "catching up." But the distinction he attributes to this building is largely a matter of the high quality of its materials and furnishings:

How comfortable the slightly recessed windows of the bel étage, divided by fluted, gently profiled columns; how intimate the greenery that will grow around the balustrade and the balconies; how noble the wide courtyard set with fir trees! To be sure, the design of the building—with its careful, finely drawn details—cannot pretend to be a new word in architecture.[28]

Other architectural interpretations of the neoclassical revival on Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt not only were more original than that of the Benois brothers but also established patterns that would reappear in the 1930s. The leader in this development was Vladimir Shchuko, who graduated from the Academy of Arts in 1904 and, like Fomin, was awarded a diploma trip to Italy. Parallels in the two architects' early careers include the effect of Italian architecture on their work; their appreciation for the varieties of Russian neoclassicism, brilliantly reinterpreted in Shchuko's pavilions for the 1911 Rome and Turin exhibitions (Figs. 272, 273); and their sketches of classical structures, which belong to the realm of architectural fantasy.[29]

Although Shchuko built little in Petersburg, he had greater success than Fomin with large forms. In 1908–1910 he built his first apartment house, at No. 63 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, for Konstantin Markov, a military engineer and real estate developer who had done the initial design for the building. With its fifth story above the profiled cornice, the building represents a variation on the Italian Renaissance style, with Ionic pilasters inscribed in a facade of roughly finished ashlar (Fig. 274). The central portion of the facade is recessed from the sidewalk; the larger of the two wings has loggias on the interior corner. The decorative motif of carved panels bordering the loggias would recur in Shchuko's work and that of other architects in Moscow and Leningrad during the 1930s. Indeed, at Nos. 69–71 on the same street is Nikolai Lanceray's apartment house for the Institute of Experimental Medicine (1935–1936), replete with loggias.

Shchuko's debt to the Italian Renaissance is evident in the Markov building; and Lukomskii, whose critical writings demonstrate his own love for Italian culture, wrote approvingly of the creative path Shchuko had taken:

Fig. 270.

Residence of the emir of Bukhara, Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, Petersburg. 1913. Stepan Krichinskii

(Brumfield L71-80).

Fig. 271.

Apartment house of the First Russian Insurance Company, Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt,

Petersburg. 1911–1913. Iulii Benois, Leontii Benois (Brumfield L70-2).

Fig. 272.

Russian Pavilion at 1911 Turin International Exhibition. Vladimir Shchuko. Ezhegodnik

Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1911.

Fig. 273.

Russian Pavilion at 1911 Rome International Exhibition. Vladimir Shchuko.

Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1911.

Fig. 274.

Markov apartment house No. 63 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, Petersburg. 1908–1910. Vladimir Shchuko.

At left, adjacent to No. 63, is the second of Shchuko's buildings for Markov, No. 65 (Brumfield L73-36).

After his trip to Italy [in 1905], mainly to study Palladio in Vicenza and to take measurements of the work of Giulio Romano in Mantua, Shchuko became noticeably Italian, as is evident . . . in one of the facades of the Markov building on Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt. The second facade [No. 63], with its marvelous loggias, is already executed in the forms of the rinascimento ; the treatment of ornament is charming, displayed in the strip carving of the stone.[30]

The Markov apartment house at No. 63, however, is no simple stylization, for it combines classical elements in a monumental design that is neither historical nor modern. Shchuko developed a style appropriate for contemporary urban architecture, one that provided material evidence of the classical values propagated by Lukomskii:

The buildings designed by the architect V. A. Shchuko (Nos. 63–65 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt) were the first classical structures in the new sense of that word; and indeed, not only their general forms but their details were borrowed from the originals and applied to the new conditions of the apartment house.

Implementation itself, moreover, is beginning to play an important role: both the design and the working out of details matter.[31]

The most striking attention to detail appears, paradoxically, in the undecorated rectangular windows. Generally the windows of an apartment building advertised its interior comfort and aesthetic pretension. Yet Shchuko used the simplest of designs, recessed in a flat stone surface and without surrounds or mullions.

His subsequent, adjacent, apartment house for Markov (No. 65; built in 1910–1911) adopted a more histrionic approach in its massive articulation of the classical orders (Fig. 275). The attached Ionic columns rise four floors, from the second floor to the attic, which is designed like a colossal broken cornice. The shafts of projecting window bays are wedged between columns that balance practicality and architectural fantasy. Much as he had praised the loggias and the subtle details of No. 63, Lukomskii was even more impressed by the hypertrophied forms of No. 65, which seemed to prove that the classical orders could be applied on a scale commensurate with the needs of a modern city:

Undoubtedly Shchuko's greatest service is to have solved that most difficult problem of designing the facade of an apartment building. The corner building for Markov [No. 65] is superb in its integrity; the order of the columns is maintained through all the floors, one of which [the fifth] is even inserted between the breaks in the entablature. The device of the Casa del Diabolo in Vicenza has found a clever application. The details of the building are also executed successfully. The graceful capitals of the pilasters are superb. Less successful are the consoles of the first-floor balconies, in a baroque spirit that does not suit the architecture of Palladio.[32]

Shchuko, rejecting all trace of the moderne, had created a form that would prove influential in the second "revival" of neoclassicism (and concomitant rejection of modernism) in the 1930s. Although the second phase of the Markov apartments had its clearest influence in Ivan Zholtovskii's design for an apartment building on Marx Prospekt in Moscow (1935), the ramifications of Shchuko's neoclassicism appeared in many other, less obvious, forms during the retrospective phase of Soviet architecture—indeed, until the late 1950s. The artistic sensitivity of neither Shchuko nor Lukomskii, however, obscures the contradictions in their determined rejection of a modern architectural idiom. Lukomskii, seizing on the success of Shchuko's work, rejected a future he professed was inevitable in favor of a past he dared not relinquish.

With the disavowal of modernism, Russian architectural discourse again turned to the questions of guiding ideals and the threat of aesthetic chaos. When Aleksandr Benois published in 1910 an article entitled "The Death of Architecture," Kurbatov testily responded in his "Decline or Death?":

The decline of architecture in Russia! . . . How could it be otherwise when the major patron—the government—has not been guided by artistic demands since the mid-nineteenth century and when the wealthy during the same period have built nothing for themselves. That leaves apartment buildings. If you build them in the form of a box, with no decoration whatsoever, it would be no loss. . . . In Petersburg each of them screams, magnifying the cacophony.[33]

Fig. 275.

Markov apartment house, No. 65 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt. 1910–1911. Vladimir Shchuko. Ezhegodnik

Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1911.

At the Fourth Congress of Russian Architects, held in Petersburg in January 1911, Lukomskii succinctly defended the neoclassical revival as the proper style of the times. Having dismissed the style moderne as a rootless invention of "a little decade-long epoch of individualism," he noted with relief the return to eternal principles in architecture:

Convinced, after an epoch of agitated searching for a new form, new beauty and ornamentation, that bright achievements are impossible without new constructive devices and materials, architecture—like art—became ashamed of its irrationality. It is again joyously repeating and taking as its base the old national forms while waiting for the decisive discoveries of an iron architecture that has not yet found its superb form.[34]

In his sketch of the neoclassical revival, Lukomskii, like Aleksandr Benois, criticized the facile Empire motifs ("pastry-cake Empire") but approved the "stern taste of Italian [Renaissance] architects" exercised by Shchuko, Lialevich, Lidval, and Girshovich—all active in Petersburg.[35] Lukomskii's comments on the as-yet-undiscovered aesthetic properties of modern architecture were disingenuous; he overlooked advances in design that had

appeared in Moscow, particularly in the recent commercial buildings of Shekhtel. But then Moscow had been far more receptive to the style moderne and was correspondingly less active in the neoclassical revival.

Although many apartment buildings in Moscow followed the new fashion for neoclassical detail, few of them constituted coherent expressions of the revival style. Among the exceptions are the Shcherbatov apartment house, built in 1912–1913 by A. I. Tamanov (Tamanian) on Novinskii Boulevard, which resembles a hypertrophied version of a Moscow urban villa from the late Empire period (Fig. 276), and the I. E. Kuznetsov apartment house on Miasnitskaia Street (1910), another massive Empire design by A. N. Miliukov and Boris Velikovskii, assisted by the future Constructivists Viktor and Aleksandr Vesnin (Fig. 277).[36]

For Lukomskii, Moscow's aberrant preference for the style moderne was typical of the city:

Nowhere did these strivings for the new appear so curiously as in Moscow, where the bizarre refrains of this new movement achieved outlandish results and forms. As in the architecture of all the epochs that are so distinctly and willfully manifested in Moscow, so in the buildings of the new epoch there is a display of that peculiar Moscow variety.[37]

For Lukomskii, as for Lialevich, architecture developed not in materials and technical innovations but as an expression of the national spirit. Although many before him had reasoned similarly to justify a nationalist architecture, Lukomskii rejected the idiosyncratic variant of the Russian architectural tradition represented by Moscow and—surprisingly—located the national spirit in the move to Europeanize the country that was symbolized by the Western architecture of the imperial capital. Although the church was no longer creative, and the state and society had not yet produced a secular order for the new architecture to reflect, Lukomskii was optimistic: "For the time being we are again in an epoch of renewal, purification, peace, and diligent study, striving to apply this study to the needs of our days."[38]

In light of subsequent events few statements have proved more illusory; even during the relatively prosperous lull between 1906 and 1914, a psychic tension underlay the new architectural forms of Petersburg, compounded of bombastic assertion and grotesquerie. This trait, already mentioned as a characteristic of banks, appeared as well in the heart of the Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, whose elegant luster gave Lukomskii so much hope for the European future of the city.

By 1910 the upper reaches of the street had a crucial "anchor" in the square where Bolshoi and Kamennoostrovskii, the two major thoroughfares of the Petersburg Side, intersect. When the civil engineer and developer Konstantin Rozenshtein convinced city authorities to extend Bolshoi Prospekt northeast of the square to the banks of the Karpovka River, this small stretch, the equivalent of a few blocks in length, immediately became one of the city's most active building sites for new apartment houses.[39] The area adjacent to the square belonged to Rozenshtein, who required an imposing, assertive style for the two apartment houses he planned to construct on a trapezoidal site. By 1911 he had sketched the rough outlines of the two buildings; for the design of the facades he turned to the architect Andrei Belogrud, who had graduated from the Academy of Arts the preceding year.[40]

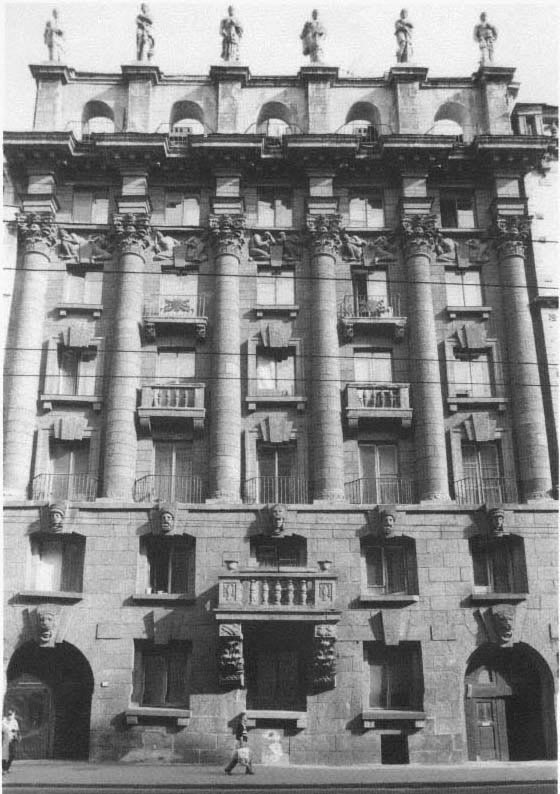

Belogrud's designs were shocking, even by the effusively "rhetorical" standards of the time. The first apartment house, at No. 77 Bolshoi Prospekt (1912–1913), was a variation on Shchuko's second Markov building; colossal attached composite columns dominate the facade (Figs. 278, 279). Whereas Shchuko's facade was wide enough to frame the columns, Belogrud's has only the six columns with flat square windows between them (Shchuko's design has projecting bays). Above the sixth floor a large broken cornice with massive dentils projects over the column shafts—but not as a culmination, as Shchuko would have had it, for above it six classical statues stand on a second cornice. The entire facade, surfaced in gray granite, is visually subordinate to this statuary.[41]

Although statues were common on Petersburg's baroque palaces, as on Renaissance structures (including, of course, those by Palladio), the grotesque concentration of them on an apartment house was unprecedented. The effrontery of the design gives the building panache, but the decoration is nonetheless disorienting. Even Fomin's design of New Petersburg had not projected such an incongruous use of Roman classicism. The pomposity of the facade is intensified by granite nude forms in high relief crouched between the capitals above the fifth story (cf. Girshovich's Siberian Trade Bank, Fig. 260). The tension expressed in these contorted figures is repeated in the massive keystones of the central windows.

Fig. 276.

Shcherbatov apartment house, Moscow. 1912–1913. A. I. Tamanov (Tamanian).

Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1912.

Fig. 277.

Kuznetsov apartment house, Moscow. 1910.

A. N. Miliukov, Boris Velikovskii (Brumfield M154-16).

Fig. 278.

Rozenshtein apartment house, Petersburg. 1912–1913. Andrei Belogrud (Brumfield L89-28).

Fig. 279.

Rozenshtein apartment house plan.

In his second apartment building for Rozenshtein, at No. 35 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt (1913–1915), Belogrud replaced the Renaissance forms with a rustic interpretation of medieval provincial Italian architecture (Figs. 280, 281). Although pretentious, the building nonetheless fits its site, on a large city square. The two towers flanking the main entrance suggest medieval town fortifications, but the picturesque quality derives primarily from the rusticated quoins and lancet window surrounds on the massive stuccoed walls.

Although Belogrud later handled the rustic Italianate form with restraint, eclectic decoration still prevails in the second Rozenshtein building.[42] As a result, Rozenshtein's development project, dominated by Belogrud's strikingly different designs for two major structures (a third was further up Bolshoi Prospekt) produced what critics called a cacophony of styles (Fig. 282). Even Lukomskii, who approved the Italian character of Belogrud's work, doubted the aesthetic wisdom of construction guided only by speculative commercial interests:

One must regret . . . that in this area, where a new city might gradually form, no general plan was worked out in advance, and now this "fortunate" street presents a conglomeration of buildings in all styles, from the medieval to the moderne. And how can one fight this evil [a variety of styles and devices] when the same architect [Belogrud] constructs in one area, in two to three years, three buildings of undoubted architectural interest but all in a different character? This means that eclecticism still looms large, or that even a good master must resort to various styles to satisfy various commissions.[43]

Although Lukomskii was responding specifically to Belogrud's work, his rhetoric suggests both postrevolutionary regulatory goals and Soviet attacks on "chaotic" design and construction under capitalism. The cult of individualism both Fomin and Lukomskii had criticized in the style moderne now flourished in the neoclassical revival—even in its "Italian" branch. Having ignored the economic implications of the fashionable Europeanized Petersburg he envisioned, Lukomskii revealed his unease with the entrepreneurs essential to the development of private apartment buildings.

Developers like Rozenshtein competed for the same prosperous clientele that had stimulated the construction of apartments in the new style. The stylistic identity of each building advertised its amenities—and justified the price of a fashionable address. In praising the

Fig. 280.

Rozenshtein apartment house, No. 35 Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt. 1913–1915. Andrei Belogrud

(Brumfield L-49).

Fig. 281.

Rozenshtein apartment house, No. 35 Kamennoostrovskii

Prospekt. Plan. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1915.

Fig. 282.

Rozenshtein apartment houses (Brumfield L89-25).

Fig. 283.

House of Prince A. V. Obolenskii, Lake Saimaa, Finland. 1911. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik

Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1913.

classical monumentality of contemporary urban housing—particularly in unrealistic projects on the scale of New Petersburg—Lukomskii attempted to impose a precapitalist architectural ideal in a capitalist environment. That he did so consciously is evident in his comments on Fomin in a survey of neoclassical architecture in Apollon :

The unquestioned beauty of Fomin's work is close to the very basis of Old Petersburg; so it is unforgivable not to make use of this master! Moreover, Fomin's art does not at all correspond to the contemporary economic spirit of calculation and triviality, of contemporary cheapness and bad workmanship; this, of course, makes it difficult for him to work on the construction of apartment houses. Therefore, . . . the development of an entire area of the city [Golodai Island], with new apartment houses and other structures . . . wholly based on splendid traditions and implemented so that not one detail would detract from the impression of the whole, is not, it seems, to be realized.[44]

One might dismiss Lukomskii's views as those of a disgruntled aesthete did they not express a fundamental intellectual opposition to capitalism itself in Russia.

Indeed, the most refined evocations of a heroic past in Fomin's work, and that of the neoclassical revival generally, were in private mansions, an architectural genreremote from the major concerns of contemporary urban architecture. Fomin, the undoubted master of this genre in Petersburg, created houses and interiors derived primarily from the late Empire style in Russia, but modified to exaggerate certain tectonic features and simplify decorative elements of the exterior. His talent for interior work had already appeared in his furniture designs as well as in the Pomer apartments; many of his early neoclassical projects were interiors. In 1909 he began the interior of the house of Princess Maria Shakhovskaia (on Fontanka Quay at the Anichkov Bridge), completing it after his return from Italy in 1911. At the same time, he rebuilt a country villa for Prince A. V. Obolenskii on Lake Saimaa (in Finland) that interpreted the classical style in the manner of early Petrine architecture (Fig. 283). In 1912 he constructed a more typical

Fig. 284.

Polovtsev dacha, Stone Island, Petersburg. 1911–1913. Ivan Fomin (Brumfield L-45).

neoclassical country house for Prince A. G. Gagarin on his estate of Kholomki (east of Pskov).[45]

Fomin's greatest achievement in the neoclassical revival took shape on Stone Island, where a number of private houses had been built in the style moderne. The site of Fomin's house for the prominent diplomat A. A. Polovtsev was perhaps the most desirable on the island: directly across the Middle Nevka River from Rossi's magnificent Elagin Palace. Karl Shmidt conceived the original plan for the project in 1909, adopting the new fashion of neoclassicism; when the senior Polovtsev died, his family hired the more talented Fomin to produce a new design.[46] Drawing on motifs of the Russian Empire style, Fomin applied them on a large scale—as though he could reaffirm classical values only by amplifying them.

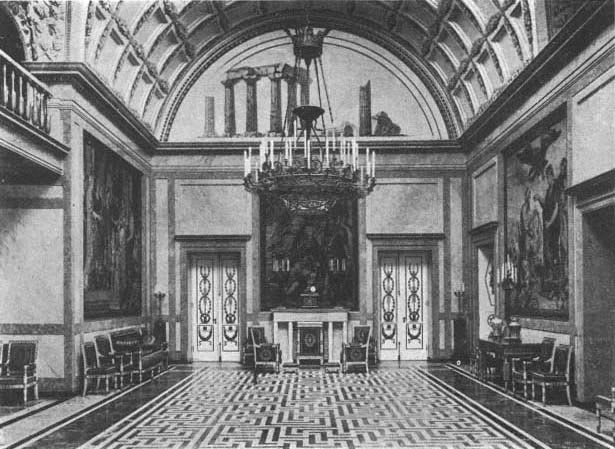

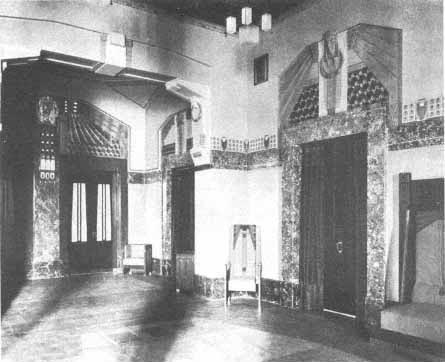

The courtyard facades follow a late eighteenth-century design, but the central structure and its relation to the parts are grander than in even the most luxurious neoclassical houses (Figs. 284, 285). Both the wings and the central structure contain an Ionic colonnade with a simple entablature and oversized dentils that mark the upper level of the two-storied structure. A double-columned portico, extended forward on either side, frames the central enfilade, whose pediment rises above the rest of the structure. The entrance is defined by a semicircular niche with a coffered ceiling that serves as a light trap.

The attention to detail and the scale—more appropriate to a museum than a dwelling—continues on the interior, where a circular vestibule leads to the heroic Gobelin Hall (so named for the five tapestries it contained, with its chandelier and arched, coffered ceiling; its gilded white doors in the Empire style; and the pattern of the black and white marble floor (Fig. 286). Distant echoes of Pompeii (excavations there were discussed in Zodchii ) are reinforced by wall paintings of classical ruins (in the style of Paestum) on the lunettes beneath the vault.[47]

Beyond the double doors is the White-Columned Hall, whose scagliola columns support a ceiling of three vaults, the main one preserved from the early nineteenth-century dacha of Baron Ludwig Stieglitz originally on the site.[48] The Italian ceiling, apparently preserved from this dacha, is comparable to that of the great White Hall in Carlo Rossi's Mikhailovskii Palace, whose design, however, is more elaborate. The main enfilade concludes with a semicircular conservatory, from which the Elagin Palace across the river can be seen.

The other rooms of the main structure show the

Fig. 285.

Polovtsev dacha plan. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1916.

Fig. 286.

Polovtsev dacha, Gobelin Hall. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1916.

Fig. 287.

Abamalek-Lazarev house, Petersburg. 1913–1915. Ivan Fomin (Brumfield L-46).

same attention to spatial design and decorative detail, though on a smaller scale. This house (the Polovtsevs had an equally palatial residence in the city) might well have been the greatest built in Petersburg at the beginning of this century—and one of the last. The extensive interior decoration, which involved the work of Roman Meltser and the painter Ivan Bogdaninskii, was completed in 1916; since the revolution, its grand halls and rooms, with wall and ceiling paintings preserved, have been used variously as a retirement home and a sanatorium.

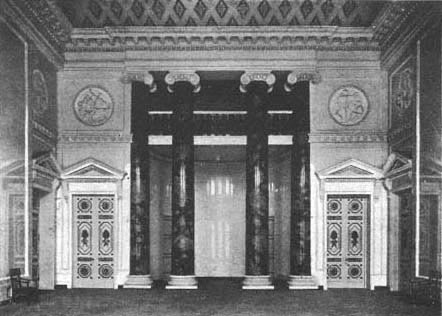

In 1913–1915 Fomin built the second of his neoclassical revival houses, for Prince S. S. AbamalekLazarev at No. 23 Moika Quay. In effect the house, in a densely constructed central area of the city, included three buildings from the eighteenth century; each had its own distinctive facade on the Moika and on Millionaia Street (the west side of the lot). Fomin's commission was to rebuild a four-storied structure on the Moika, with a neoclassical facade and greatly expanded state rooms (Fig. 287). On the stuccoed surface six Corinthian pilasters extend from a rusticated ground floor to a third level, whose small windows are barely noticeable between the Corinthian capitals. The pilasters frame five medallions with plaster reliefs of dancers in classical attire. Though faithful to the spirit of the Empire style, the details are so prominent in the constricted space of a Petersburg townhouse that they comment on, rather than reproduce, the old style.

The classical features on the interior are similar to those of the Polovtsev house but are even more ingenious in view of Fomin's spatial limitations. Most of the smaller, private, rooms were in the other parts of the structure; Fomin designed a grand staircase, a banqueting hall, and a theater—all luxurious re-creations of the nineteenth-century neoclassical ambience, with coffered ceilings, false marble columns, delicate parquetry, plaster relief medallions, and wall and ceiling paintings (Figs. 288, 289). Here, as at the Polovtsev mansion, Fomin enshrined a past epoch in what is virtually a museum setting.[49]

In retrospect Fomin's burst of creativity in designing neoclassical revival mansions and interiors seems like an effort to accomplish as much as possible in his elegiac

Fig. 288.

Abamalek-Lazarev house. Sketch of dining hall. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1913.

Fig. 289.

Abamalek-Lazarev house. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov ,

1916.

style before the deluge. In addition to the work just discussed, he constructed at least four estate houses in Finland and in Podolsk Province, as well as a number of other interiors in Petersburg—including those for houses of the Ratkov-Rozhnov family, Count Ivan Vorontsov-Dashkov, and Senator D. B. Neidgardt.[50] Each of these interior designs is notable for decorative details and applied techniques based on an exhaustive study of the Russian neoclassical style (Fig. 290). At the same time, each displays the abstract, cerebral quality of a stylization.

Other Petersburg architects also excelled in designing neoclassical revival houses. Although Georgii Lukomskii criticized Marian Lialevich's Italian villa for M. K. Pokotilova (1909) on Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt (Fig. 291) for its "timid proportions" and "excessively precious and saccharine handling of details," it represented a first step toward Lialevich's mature use of classical elements in the Bykovskii apartment building and in his work for Mertens.[51] A nobler effort, not mentioned by Lukomskii, was Andrei Ohl's exquisite townhouse for T. V. Belozerskii on Bolshaia Dvorianskaia (1913). Like many of his contemporaries, Ohl had moved from the style moderne to the neoclassical revival; although his dacha for V. A. Planson on Stone Island (1912; destroyed in 1968) showed both modern and classical elements, the Belozerskii house offers an assured interpretation of neoclassicism in the manner of Matvei Kazakov, whose late eighteenth-century mansions in Moscow are the quintessential expression of this style of domestic architecture.[52]

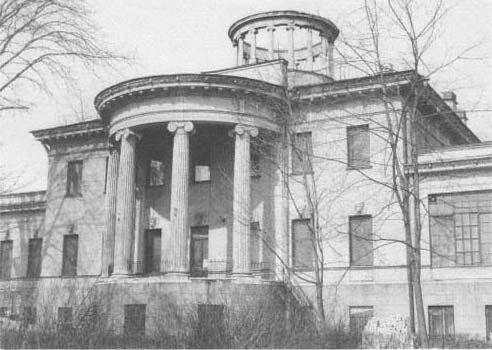

The greatest concentration of neoclassical revival houses is on Stone Island, whose rapid development during the years just before the war produced a wide range of interpretations of the style. In 1913 Vladimir Apyshkov built a grand mansion for S. N. Chaev. The architect's earlier style moderne townhouse for Chaev (see Figs. 208–211) represents one extreme of fashion and the mansion, with its circular, open colonnade above a large Ionic portico, another: the monumentality of Palladian architecture (Fig. 292). Not far from the Chaev house is the F. Mertens mansion (1911) by Lialevich; both houses are abstracted compilations of classical devices, primarily Italian; unlike Fomin's work, they bear little resemblance to Russian prototypes in the Empire style. Somewhat smaller but no less luxurious is Nikolai Verevkin's Italian Renaissance villa for Elena Krilichevskaia (1914) in the central part of the island (Fig. 293).

Although Italian imitations predominated in the last phase of construction on Stone Island, the Russian neoclassical, or Empire, style appeared in Moisei Siniaver's design for the M. A. Vurgaft mansion (1913) and in Mikhail Devishin's smaller dacha (1914) for Doctor V. M. Bekhterev, the noted Russian neuropathologist.[53] The Bekhterev house combines the complex plan of the style moderne (as in Shekhtel's neoclassical house) with such classical elements as the channeled Greek Doric columns of the entrance porch and, to the right of it in Figure 294, the exterior of the sitting room. Although plaster motifs from the Empire period decorate the elevated pediments of both the main and south facades, the structure itself and the eaves suggest a late nineteenth-century cottage rather than an Empire-style country house. This charming design, by a virtually unknown architect, demonstrates the pervasiveness of the neoclassical revival in even modest, "vernacular" architecture. Whereas Fomin's neoclassical work was commissioned primarily by the Russian nobility, most of the other houses were built by "new money," presumably emulating the social values of the ancien régime.

The neoclassical revival style was applied less extensively in Moscow than in Petersburg, yet it served Moscow effectively as a monumental expression of new wealth and cultural respectability. No critic promoted the revival there as the representation of social stability through classical architectural principles. Moscow accommodated the style as the latest fashion. The most prominent of Moscow's new classicists was Ivan Zholtovskii, who graduated from the Academy of Arts in 1898 and the following year joined the faculty of the Stroganov Institute, where his colleagues included Fedor Shekhtel. Zholtovskii's first major work, the headquarters of the Racing Society in Petrovskii Park (1903–1906), demonstrated both his self-assurance and his original approach to classical form (Fig. 295). Elena Borisova has argued persuasively that the Racing Society building embodies not a single interpretation of Russian neoclassicism but a combination of Empire and Renaissance forms (the latter on the interior) that owes much to the stylistic experimentation of the style moderne.[54]

The power of architecture to express wealth is no-where demonstrated more amply than in Zholtovskii's mansion for Gavriil Gavriilovich Tarasov on Spiridonovka Street (1909–1912). Tarasov's father and two uncles made a fortune in the wholesale trade of manufactured goods in southern Russia (Ekaterinodar) and

Fig. 290.

Project sketch for house of N. V. Spiridonov, Finland. Ivan Fomin. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1913.

Fig. 291.

Pokotilova house, Kamennoostrovskii Prospekt, Petersburg. 1909. Marian Lialevich (Brumfield L71-86).

Fig. 292.

Chaev house, Stone Island, Petersburg. 1913. Vladimir Apyshkov (Brumfield L49-10).

Fig. 293.

Krilichevskaia house, Stone Island, Petersburg. 1914. Nikolai Verevkin

(Brumfield L49-6).

Fig. 294.

Bekhterev house, Stone Island, Petersburg. 1914. Mikhail Devishin (Brumfield L49-3).

Fig. 295.

Moscow Racing Society. 1903–1906. Ivan Zholtovskii. Ezhegodnik Obshchestva

arkhitektorov-khudozhnikov , 1907.

subsequently moved to Moscow. Like many of Russia's wealthy merchants, the Tarasov brothers were legendary eccentrics, but the second generation moved rapidly into the cultural world.[55] Indeed, it would be difficult to imagine a more assertive statement of high culture than Zholtovskii's design of the Tarasov mansion, modeled on Palladio's Palazzo Thiena in Vicenza. According to the merchant chronicler Pavel Buryshkin, it "immediately became one of the landmarks of Moscow."[56]

No other Moscow house resembles it; and though the form, derived from the Renaissance, might seem a comic pretense on the part of a family from the southern steppes, the association with the merchants of Renaissance Italy has a certain logic (Fig. 296). With its heavily rusticated granite facade and chiseled Latin inscriptions—including one beginning Gabrielus Tarassof Fecit—the mansion symbolized the arrival of the merchant class; yet, as with the Petersburg banks of Peretiatkovich and Girshovich, such massive pretentiousness undercut the very notion of social stability. The lavish interior includes extensive wall and ceiling paintings by Ivan Nivinskii and Evgenii Lanceray.[57]

Lukomskii, of course, approved of the house as a brilliant interpretation of Renaissance forms:

It is already evident how well the mansion blends with the Moscow landscape surrounding it, consisting of stylistically varied imitations—the "Gothic chambers" of the Morozovs, the Vienna "moderne" of the Riabushinskii house [both by Shekhtel]. This new, seemingly authentic, Italian palace is a valuable ornament in this architectural mosaic.[58]

Lukomskii here seems to recognize tacitly the distinctiveness of the detached house as an expression of Moscow's individualistic, entrepreneurial culture.

The other major example of the neoclassical revival as an expression of new wealth in Moscow was the design by the firm of V. D. Adamovich and V. M. Maiat for the mansion of Nikolai Vtorov (completed by 1914). Adamovich and Maiat, both as a team and individually, were prolific architects who worked in a variety of styles (see Fig. 100). Their major work involved the design of classically inspired houses for the very rich, including two of the Riabushinskii brothers: Vladimir and Nikolai. The house for Nikolai Riabushinskii, in Petrovskii Park, provided a setting for the outré style of life maintained by this leading proponent of the artistic avant-garde.[59] Though decorated in a modernist fashion inside, the exterior was that of a conservative neoclassical villa whose white stuccoed walls belied the sobriquet of the house: "the Black Swan" (Figs. 297, 298).

The Riabushinskii brothers' wealth, however, paled in comparison with that of Nikolai Vtorov, whose father, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich, made a fortune through wholesale trade in Siberia. Nikolai—like the Tarasovs—resettled in Moscow, where he continued the Vtorov firm's interest in wholesale distribution while expanding into banking and manufacturing.[60] The design of the Vtorov house, derived from Moscow's neoclassical mansions of the early nineteenth century (particularly the work of Domenico Giliardi and Osip Bove), seems to have been inspired by a wish to re-create the Empire style on a scale twice as large as the original (Figs. 299, 300). The main hall, around which the house is organized, is almost 25 meters high, with an enormous silver and crystal chandelier suspended from its midpoint. The other rooms, in the rococo or neoclassical style, display equally luxurious decorative details that are scrupulously maintained in what is now Spaso House, the residence of the American ambassador to the Soviet Union.

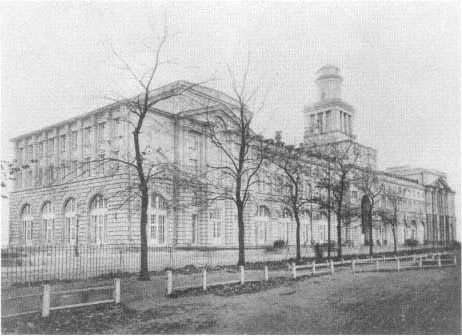

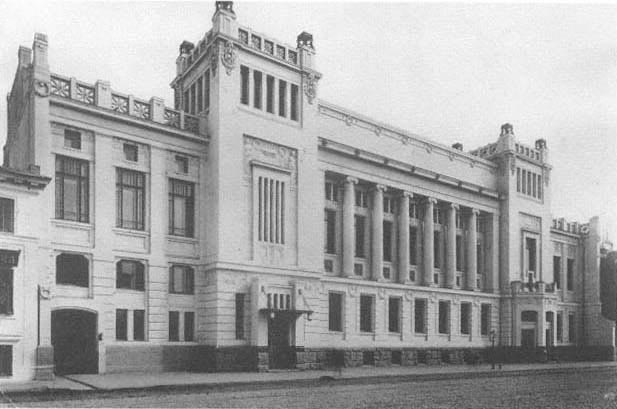

Although other examples of the neoclassical revival in Moscow's mansions, such as the Mindovskii house by N. G. Lazarev (Fig. 301), offered little more than Adamovich and Maiat's competent reworking of a historical style, the revival achieved a measure of originality in large-scale public architecture, particularly the work of Ilarion Ivanov-Schitz, who used a modernized form of classical tectonics. The recessed Ionic portico of his Merchants' Club on the Dmitrovka (built in 1907–1908; now the Komsomol Theater on Chekhov Street) is flanked by square towers with classical elements whose form owes much to the Vienna Secession (Fig. 302). The advanced style is even more evident inside, where decorative shapes—streamlined, abstract—resemble those of contemporary Viennese design (Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos) and anticipate modern design in the West during the 1920s (Figs. 303, 304).[61] Ivanov-Schitz used a similar blocklike, classicized form on a much larger scale in his building for the Shaniavskii People's University (Fig. 305).[62]

The most versatile and productive adherent of the neoclassical revival in Moscow was Roman Klein, whose major contributions to the Russian Revival style (the Middle Trading Rows) and the moderne (the Muir and Mirrielees store) have already been discussed. Of some

Fig. 296.

Tarasov house, Moscow. 1909–1912. Ivan Zholtovskii (Brumfield M103-3).

sixty buildings he completed in Moscow, the majority follow a variant of classicism—a reflection of his trip to Italy in 1882, a year after his graduation from the Academy of Arts. The most prominent of these buildings was the Museum of Fine Arts, established by Professor Ivan Tsvetaev (father of the poet Marina Tsvetaeva) under the auspices of Moscow University. In 1897 Klein won the design competition, sponsored by the Academy of Arts. A large part of the unfinished building was damaged by fire in December 1904; and from 1906 to 1908 further work was threatened when a financial depression affected the largess of Iurii Nechaev-Maltsev, a leading glassware manufacturer in Russia and the major private donor to the museum.[63]

In 1912, Klein received the title Academician of Architecture from the Academy of Arts in recognition of his work on the monumental structure (Fig. 306). Indeed, with its combination of Greek and Roman elements and the highly professional finish of both its interior and its granite- and marble-clad exterior, it is comparable to contemporary museums and public buildings erected elsewhere in Europe and in America. The eclectic design has been justified as an effort to incorporate elements of classical architecture into a museum originally intended for ancient and Renaissance art (see Plate 38).[64] Klein had studied the latest forms of museum construction in Europe, and he built a temple to the arts that expressed civic pride and private patronage, thus pleasing his benefactor, Nechaev-Maltsev, and creating what Lukomskii would have called approvingly a "European" building, noticeably different from the public and commercial buildings whose neoclassicism derived from the local Empire style.

Klein's building for the Institute of Mineralogy and

Fig. 297.

Nikolai Riabushinskii villa, Moscow. Ca. 1909. V. D. Adamovich, V. M. Maiat.

Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1910–1911.

Fig. 298.

Nikolai Riabushinskii villa. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1910–1911.

Fig. 299.

Vtorov house, Moscow. 1912–1914. V. D. Adamovich, V. M. Maiat. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1914–1916.

Fig. 300.

Vtorov house, main hall (Brumfield M140-14).

Fig. 301.

Mindovskii house, Moscow. Ca. 1908. N. G. Lazarev. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

Fig. 302.

Merchants' Club, Moscow. 1907–1908. Ilarion Ivanov-Schitz. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1909.

Fig. 303.

Merchants' Club, vestibule. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo arkhitekturnogo

obshchestva , 1909.

Fig. 304.

Merchants' Club, meeting room.

Photograph ca. 1908.

Fig. 305.

Shaniavskii People's University, Moscow. 1910–1913. Ilarion Ivanov-Schitz.

Photograph ca. 1914.

Fig. 306.

Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. 1897–1912. Roman Klein. Moskovskii arkhitekturnyi mir , 1913.

Fig. 307.

Institute of Mineralogy and Geology, Moscow. 1914–1918. Roman Klein (Brumfield M55-6).

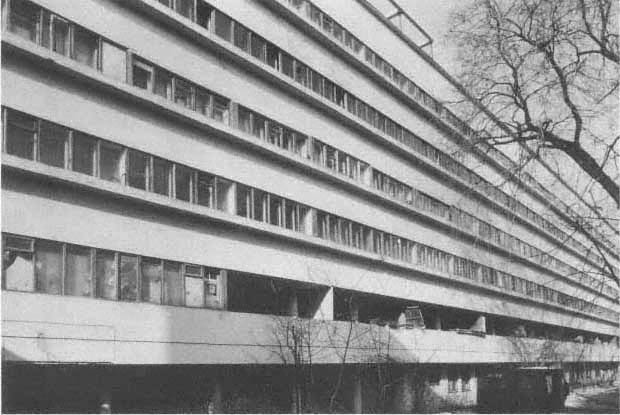

Geology, constructed in 1914–1918, exemplifies precisely the local Empire style; it follows faithfully Giliardi's post-1812 reconstruction of the main building of Moscow University, in the adjacent block (Fig. 307), whose renovation Klein was supervising at the same time. But he did his most ambitious work in the retrospective manner at Arkhangelskoe, near Moscow, where he constructed a mausoleum (1911–1916) for the Iusupov family in the Palladian style, with a domed chapel and curved double colonnade extending from either side.[65] The design and materials (including gray granite and marble) were of the highest quality, and the building has been carefully maintained in its cold magnificence (Fig. 308). Ivan Nivinskii, who had directed the wall painting of the Museum of Fine Arts, decorated the interior (see Plate 39).

Klein's later work drew on a number of historical styles. His building for the Moscow Choral Synagogue had a neoclassical exterior and a Byzantine interior.[66] The facade for his Coliseum Cinema on Chistoprudnyi Boulevard (1914) suggests a classical temple (freely interpreted), with a semicircular Ionic portico and a recessed entrance framed by a large arch beneath the central pediment (Fig. 309). Although the neoclassical reference is clearly stated, the articulation of volume and the oversized decorative motifs derive indisputably from the style moderne (as in Fomin's early designs for country houses). No movie house in Petersburg was so impressive; and one might speculate on the expectations placed upon the new art medium in the creation of such a monumental structure.[67]

Indeed, by 1910 Moscow was being refashioned by monumental neoclassicism as classically inspired structures arose at dominant points in the city landscape. Klein's Museum of Fine Arts and Ivanov-Schitz's Shaniavskii People's University are two of the many examples of neoclassical revival buildings on squares or near major intersections. Another example is Sergei Solovev's building for the Higher Women's Courses (1910–1912) on Malaia Pirogovskaia Street, near the

Fig. 308.

Iusupov mausoleum, Arkhangelskoe. 1911–1916. Roman Klein (Brumfield MR13-8).

Fig. 309.

Coliseum Cinema, Moscow. 1914. Roman Klein (Brumfield M132-1).

Fig. 310.

Project sketch for Kiev Railway Station, Moscow. 1914–1920. Ivan Rerberg. Ezhegodnik Moskovskogo

arkhitekturnogo obshchestva , 1912–1913.

Novodevichi Convent, with its elongated wings extending at an acute angle from a large corner rotunda in the Doric order.[68] The main auditorium in the space between the wings was more elaborately fitted in the Corinthian order.