Five—

Senex

Walchensee

Almost eighty, or nearly one-third, of all Corinth's pictures between 1918 and 1925 were painted at the Walchensee. His etchings and lithographs of the lake during the same period include no fewer than five print cycles; and he produced, in addition, an impressive number of watercolors and drawings of the subject. The paintings of the Walchensee won immediate acclaim and sold well. When Erich Goeritz, a wealthy textile manufacturer from Chemnitz who owned one of the major private collections of Corinth's works, wanted to purchase two Walchensee landscapes in September 1921, he learned, even before he could discuss prices, that the paintings had already been sold. "I am distressed," he wrote to Corinth, "but please remember me in the future, because I must have a Walchensee landscape to round out my . . . collection."[1] According to Corinth, "every Berliner" wanted to have a painting of the Walchensee; and museums and galleries were eager to acquire Walchensee landscapes "by any means."[2]

Corinth's earlier landscapes were the result of a portrait and figure painter's sporadic excursions; this new preoccupation marks a major departure. The popularity of these landscapes and the attendant financial rewards, however, were not necessarily the primary reason for their sudden preponderance. Neither did the lake serve merely as a convenient visual stimulus for Corinth's creative energy, although there are Walchensee landscapes that retain all the freshness and immediacy of the painter's sensory perceptions. But for the most part the mountain landscape at the Walchensee clearly satisfied a more profound need. Unlike the analytical Cézanne, who in his long series of paintings and watercolors of Mont Sainte-Victoire was concerned above all with problems of form, Corinth looked at the lake as into a mirror in which he discovered a reflection of his innermost sensations; or, more accurately, he projected his own feelings into the evocative landscape. This synthesis of visual sensation and inner vision allowed landscape painting to become finally an integral part of his work.

In the course of sixteen trips to the Walchensee Corinth painted the lake in all seasons, at all times of the day, and at night, when the moon stood high above the mountains. Collectively, these works epitomize the eternal cycle of nature; Corinth's sense that he was himself a part of it can be seen from the self-portraits and the portraits of members of his family that he painted against the backdrop of the lake and its environs.

The Walchensee, or "Lake of the Volcae," from the name of Celtic tribes that had originally settled in the region, lies about forty miles south of Munich, close to the Austrian border near Mittenwald, on what used to be called the Italian Road. On September 7, 1786, Goethe had passed the lake on his way south and stopped briefly to make a drawing of the small twelfth-century chapel that still stands near the southern shore; it is visible in the far distance in several of Corinth's paintings.[3] The most spectacular approach to the Walchensee is from the north, via the town of Kochel on the picturesque Kochel See, by way of the winding loops of the Kesselberg Road, which at its highest elevation provides the first glimpse of the lake, bordered by dark, wooded slopes and backed by the bare cliffs of the Karwendel massif and the Wetterstein. The road continues along the western shore of the lake, wedged between the water and the mountains that descend rapidly into the lake. Nineteenth-century travel books noted the changeable character of the Walchensee, somber in the foreboding stillness of a cloudy day (the monks at nearby Benediktbeuren called it the lake of silence), glistening in the sun.[4] Corinth, too, responded to the lake's many moods, his sensibilities sharpened by his visual acuity:

The lake changes from one mysterious color and mood to another. It can sparkle like an emerald, turn blue like a sapphire; suddenly amethysts glitter amid the mighty setting of the old black firs whose reflections in the clear water are darker still. . . . The Walchensee is breathtakingly beautiful when the sky is clear but ominous when the powers of nature are raging. . . . They call it the lake of suicides. Down in the valley stands a small locked shed in which the victims of the lake are gathered. The black reflections on the water only make the horror still more dreadful.[5]

The elemental character of the Walchensee, so unlike the domesticated ambience of the Starnberger See where Corinth had so often spent time in the 1890s, clearly played a major role in his turn toward landscape painting. Although modern tourism has diminished the magic of the remote mountain lake, in 1918 the region was still largely unspoiled. The small hamlet of Urfeld, nestled in the northernmost corner of the lake, had two hotels, Fischer am

Figure 156

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee: Village Street , 1918. Oil on canvas, 28 × 42 cm,

B.-C. 739. Formerly Kunsthalle Bremen (painting lost).

Photo: Stickelmann.

See and Jäger am See. There were a few vacation homes and a tiny post office, but no shops. Provisions had to be obtained in Kochel; from there the only access to Urfeld was on foot or by horse-drawn vehicle.

Corinth painted his first Walchensee landscapes from the balcony of the Hotel Fischer am See. According to Charlotte Berend, the earliest of these is a small canvas depicting several rooftops and a view of the Hotel Jäger am See facing the north shore (Fig. 156).[6] Two other paintings extend the view progressively across the lake to the east (B.-C. 738) and southwest (B.-C. 737), completing the panorama of the Walchensee as seen from Urfeld. The three paintings share the same degree of objectivity. Corinth was no doubt attracted to the physical beauty of the setting, but he remained as yet a dispassionate observer. His gaze followed the shoreline almost cautiously, as if he felt it necessary to get to know the terrain by taking a careful inventory of it, right down to the pedestrians in the village street and the fishermen in their boats. Both a watercolor, dated July 20, 1918, and the earliest etching of the lake

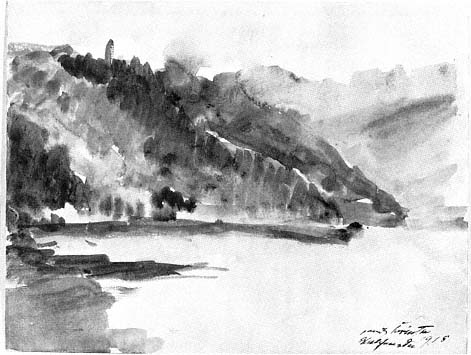

Figure 157

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee , 1918. Watercolor, 21.0 × 27.5 cm, The Galerie

St. Etienne, New York.

(Schw. 348) show the same view as one of the first paintings (B.-C. 737) and are similarly objective.[7] The importance of Corinth's watercolors in maturing his conception of the Walchensee in his paintings is evident from two further examples, both of which stand out for their expressive character. In the view toward the slopes of the Jochberg across the northern end of the lake (Fig. 157) the washes have been applied in broad, simplified patterns ranging from pink and purple to deep brown and blue, interspersed with touches of ultramarine and a cool lime green. The watercolor not only describes the terrain but also expresses a sentiment at once tender and forceful. Even more striking is Mountain Landscape with a Full Moon (Fig. 158). In it Corinth responded to the primeval character of the landscape, subordinating all incidental details to the independent language of the colors. The moon high above the Karwendel massif touches the sky with pink and white; the lake and the mountains are enveloped in unifying hues of purple and blue; and the vigorous

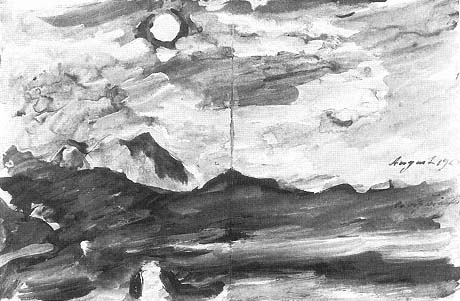

Figure 158

Lovis Corinth, Mountain Landscape with a Full Moon , 1918. Watercolor and

gouache, 20.7 × 31.5 cm. Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie,

Hannover (KM 164/1949).

brushstrokes invest the landscape with an intensity that belies the nocturnal calm. With this, his first night landscape of the Walchensee, Corinth discovered what is probably the lake's most haunting mood. Heinrich Noë, the most indefatigable of the nineteenth-century travelers who visited this Alpine region, described such a moonlit night, when the mountains are illuminated by a "mysterious glow" and the lake is at once "like molten gold" and "black as a raven"; when "clouds hover above the mountains of the southern shore," and "long white veils of fog . . . [that] flow down from the Karwendel . . . are caught in the many tree tops and disappear in the darkness of the lower forests."[8]

Charlotte Berend recognized how deeply the haunting beauty of the Walchensee impressed Corinth. When he told her during one of their walks in the countryside that he had recently sold a painting for the substantial sum of thirty thousand marks, she seized the opportunity: "Give me the money; I am

going to build you a house here."[9] Corinth, not wishing to be burdened with the task of overseeing such a project, was reluctant but agreed when Charlotte promised to shoulder the responsibilities of planning and supervising the construction. Work on the two-story house, built of wood in the local Bavarian style, began about a year later, in August 1919. By October of the same year Haus Petermann, as the chalet was fittingly called, was nearly completed. Charlotte had selected a site on the west slope high above Urfeld and had prudently acquired adjoining land to ensure an unimpeded view toward the south, facing the Karwendel and the Herzogstand. With a balcony and a terrace in front, the house overlooked virtually the entire panorama of the lake, all the way from the Jochberg in the northeast to the Wetterstein in the extreme southwest.

For the gable of the house Corinth painted in the summer of 1919 a large, expressive Pietà (B.-C. 754). He seems to have intended eventually to cover all the exterior walls with paintings, an idea that his family greeted with something less than enthusiasm—understandably perhaps, given the grim character of the initial piece of decoration. In 1920 only two more large panels were completed, depicting the evangelists Matthew and Luke with their respective attributes (B.-C. 788). In a more lighthearted vein, in 1919 Corinth painted a gouache triptych for the living room: Helios, preceded by Aurora scattering flowers, guides his chariot into the sky above the Jochberg; the allegory is flanked by a girl and a youth, both dancing, dressed in Bavarian peasant costumes.[10] In 1921 he painted a nymph surprised by a satyr (B.-C. 817) on the bathroom door and adorned an octagonal table top with flowers (B.-C. 822).

In the summer of 1919 Corinth painted four more pictures of the lake itself. Three of these show the view from the balcony of the Hotel Fischer am See (B.-C. 767, 769, 771); the fourth (B.-C. 768) may have been painted from the elevated building site for the future Haus Petermann. In the course of a return visit in October, Corinth painted the lake for the first time from the terrace of the nearly completed new house (see Plate 24). This painting anticipates in several ways his more mature treatment of the subject. The landscape encompasses enough details to assure topographical accuracy, but the emphasis is on the coloristic harmony that evokes the cool brilliance of an autumn day. The hues range from the yellowish green of the meadow in the foreground to the blue-green of the lake and the pale shades of violet in the distant mountains, capped with the white of an early snow. The larch tree in the lower left, which still survives at the edge of the meadow where the slope begins to drop off sharply toward the lake, appears for the first time in this painting, as do several younger trees closer to the terrace, providing vertical accents to the

predominantly horizontal configuration of the terrain. The landscape does not yet share the painterly freedom of the preceding watercolors, but the summary treatment of the major scenic components invests the picture with a monumentality that belies its relatively small size.

The Corinth family returned to Urfeld for the Christmas holidays, at which time Corinth painted his first two Walchensee snow landscapes (B.-C. 773, 775). A print portfolio suggests the extent to which the Walchensee had by then become an integral part of his life and work. The subject of the portfolio is the painter and his family circle. Entitled At the Corinthians , the group of fourteen etchings (Schw. 380) juxtaposes Haus Petermann with the Corinths' home and studio in Berlin and includes four additional prints done at Urfeld in the autumn of 1919: Thomas rowing on the lake; Wilhelmine at breakfast on the terrace; a sheet with sketches of both children in Bavarian costumes; and Franz, the handy man, who looked after the daily chores.

In subsequent paintings of the Walchensee Corinth explored vantage points other than those easily accessible from the house, such as the pass up the Kesselberg Road (B.-C. 811) or the slope of the Herzogstand (B.-C. 810, XIV, 836, XVI, 921). He also painted landscapes with more closely circumscribed views: of the entrance to the grounds, of the terrace and fountain in front of Haus Petermann, and of the garden (B.-C. 812, 813, XVIII, 922, 924, 926–928). Corinth's preferred view, however, remained the one from the terrace, usually toward the south and southwest, with the stately larch tree and a quaint cottage nearby serving as focal points in the middle ground. Often the Hotel Fischer am See with its picturesque rooftop (long since enlarged and modified) is visible at the edge of the lake. Although the pictorial structure of these views is similar, the painter's conceptual approach varies greatly. During the summer of 1920 alone Corinth painted nine Walchensee landscapes, including four nocturnes. The latter range from the silvery blue Moonlit Landscape in June (Fig. 159) and the similarly lyrical Midsummer Night (B.-C. 804) to the brooding Walchensee in Moonlight (Fig. 160) and the near-abstract composition with the same title (see Plate 25) that recalls the bold watercolor of 1918 (see Fig. 158). The unifying atmosphere of the night landscape surely encouraged the formal solutions common to these nocturnes, but their tactile forms are also elusive—as if the very essence of nature, life in all its impermanence, were revealed in one last evanescent glow. This subjective interpretation is supported by Corinth's working methods. Charlotte Berend has written of Corinth's inner preparation for his night landscapes, the tension of translating into pictorial form an image he had nurtured in his imagination all day long and the physical and emotional exhaustion that followed:

Figure 159

Lovis Corinth, Moonlit Landscape in June , 1920. Oil on cardboard, 59 × 72 cm,

B.-C. 809. Private collection.

Photo: Rheinländer.

Whenever he planned to paint a night picture, it was difficult to get a word out of him all day long. Lost in thought, he sat in his chair. As soon as it grew dark, he became restless. Now and then he stepped out . . . onto the terrace to scrutinize the lake and the sky; he kept anxiously pacing back and forth. He did not touch his evening meal. . . . In the waning light of the day he laid the colors out on the palette and hauled the easel and the canvas outside. . . . All of a sudden Lovis pulled himself together. He stepped close to me and whispered, almost inaudibly, "Petermannchen!" I then watched from the bay window as he picked up the brushes and the palette. Calmly and resolutely he stood by the canvas. It was as if his body were being absorbed by the moonlight. Only the face was still recognizable . . . and the hand, moving with alarming swiftness across the canvas. He was now painting the picture that he already carried complete in his imagination. Most of the time he needed only twenty minutes, half an hour at the most. I remained quietly at the table in the bay when Corinth came back in through the door, bent over and tired. He looked haggard. He stared at me with wide-open eyes. They had a strange and mysterious glow. I could tell that he was still far away.[11]

Figure 160

Lovis Corinth, The Walchensee in Moonlight , 1920. Oil on canvas,

78 × 106 cm, B.-C. 810. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

In only one daylight picture of this time (see Plate 26) did Corinth achieve the same allusive equilibrium of content and form as in his nocturnes. In this painting the terrain is highly simplified, and as a result the landscape remains somewhere between the real and the imagined. Like the moonlit landscape in Kaiserslautern (see Plate 25), this picture is painted on a small wood panel. Corinth evidently considered both works no more than oil sketches, for in the larger paintings of that summer, especially in two landscapes now in Mannheim and Dresden (B.-C. 808, 811), he continued to adhere to a far greater degree of objectivity.

Corinth's prints of 1920 include two more evocative night landscapes, a color lithograph (M. 473), and the first in a group of eight etchings that make up the cycle At the Walchensee (Schw. 432), to which Corinth added a portrait of the painter Friedrich Prölss (b. 1855), a friend from his years in Munich then living in nearby Mittenwald.[12] The remaining prints of the cycle depict more narrowly circumscribed views; some, indeed, are of individual motifs,

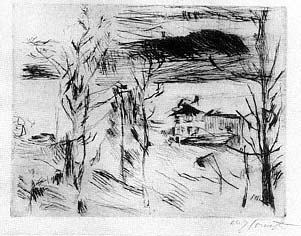

Figure 161

Lovis Corinth, House at the Walchensee , 1920.

Drypoint, 24.5 × 32.0 cm, Schw. 449, M. 731.

Kunsthalle Bremen (41/2).

such as Corinth's beloved larch tree, a billy goat grazing near the house, and Strolch, the Corinth kitten, lazily stretched out on the stump of a felled tree. The atmosphere in all these etchings is transparent, the result of Corinth's preferred etching technique, the drypoint, which invests each line with a velvety texture. An independent drypoint of 1920 (Fig. 161), included three years later in yet another Walchensee cycle (M. 727-732), is a particularly fine example of Corinth's ability to capture, even in the limited tonal range of black and white, the light and atmosphere of the lake without diminishing the imposing character of the landscape. The graphic pattern is of the utmost economy: a gossamer web of lines interwoven with aggregates of silken black. The paper ground and the graphic pattern are perfectly balanced, as is the pictorial structure with its complementary action of horizontals and verticals.

Corinth's drypoints of the lake are like chamber music in relation to the resonant sound of his corresponding watercolors and oils. Although he always executed his Walchensee drypoints from nature, drawing directly on the copper plate without the aid of preparatory studies, he never bothered to reverse the composition: the experience of the lake as a whole was more important to him than absolute topographical accuracy. His prints of the lake are thus actually mirror images of the real view. His lithographs of the Walchensee, on the other hand, are, topographically speaking, more "correct" since they were done on transfer paper. When this paper was placed face down on the lithographic stone or zinc, the crayon was deposited on the plate, and in the subsequent process of printing the image was reversed again.

In 1921 the development of Corinth's Walchensee paintings entered a new stage, in which surface texture opened up. Often, as in the dazzling View of the Wetterstein (see Plate 27), the brushstrokes slash across the canvas, yielding a blurred image, as if the lake and the mountains were seen in rapid motion from the window of a speeding train.[13] In other pictures, such as the Walchensee landscape in Berlin (see Plate 28), the paint has been applied in a heavy impasto, similarly freeing the pictorial structure from the view itself. In each instance the glowing colors reinforce the energetic bluster of the brushstrokes. Yet despite their physical beauty, there is something tragic about these paintings, for they suggest a sense of irrevocable loss, as if these views of nature could be arrested for only one intoxicating moment.[14] These Walchensee landscapes anticipate by several years, and may indeed have influenced, the equally personal landscapes Oskar Kokoschka painted in the later 1920s; and for Corinth as later for Kokoschka, these landscapes derive as much from inner life as from sensory perception. As such, they are a tribute both to the elemental forces of nature and the ephemeral nature of life.

Metaphors of Transience

Corinth's more than seventy still lifes of this period constitute the single largest category of his paintings during the last seven years of his life and for that reason alone provide the most reliable documentation for the evolution of his late style. From a purely iconographic point of view, there is little change from Corinth's earlier still lifes: most are floral pieces, alternating now and then with game, fish, fruit, vegetables, and confections; and, as earlier, emphasis is on luxuriant arrangements. Conceptually, these works are linked to the probing still lifes immediately following Corinth's stroke, except that the simultaneous allusion to efflorescence and imminent decay is now both more consistent and more insistent (Fig. 162). The flowers are nearly always shown in full bloom. Environmental allusions play a role only to provide an appropriate coloristic touch; even the vases containing the flowers are treated in a cursory way. Light falls on some flowers, allowing them to glow, while others sink into deep shadows. The blossoms are rarely individualized since—as in the Walchensee landscapes—Corinth was seeking to convey the totality of a given experience and expression. Technically, too, these still lifes display the same idiosyncracies as the paintings of the Walchensee. The fluid texture of the example in Düren (see Plate 29), similar to that of the landscapes from the same year, makes it virtually impossible to identify the flowers. They have been trans-

Figure 162

Lovis Corinth, Chrysanthemums and Calla , 1920.

Oil on canvas, 70 × 60 cm, B.-C. 790. Niedersächsisches

Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 147/1949).

formed into an active mass of color. From beneath them a human skull protrudes, a macabre reminder of transience. In the large bouquet of chrysanthemums from 1922 (Fig. 163), slashes of red, white, and green paint cover the picture surface, sometimes flowing into each other, wet on wet, in intermediary shades of violet and gray. Corinth has attacked the canvas here as in a fury, stabbing at it with the palette knife and the brush. In paintings such as these he had reached a point where the process of becoming and the process of dissolution were no longer mutually exclusive.

On three occasions between 1919 and 1923 Corinth dealt with the subject of transience in a more conventional way by juxtaposing lavish arrays of cut flowers with depictions of young women. Two of these paintings (B.-C. 762, XVII) are modern-dress versions of the traditional theme of Flora; the third, and most poignant, is a picture of his eleven-year-old daughter Wilhelmine standing next to a table on which are placed a bronze statuette and several bouquets (see Plate 30). This painting derives from the buoyant still life portrait of Charlotte Berend with game and flowers from 1911 (see Fig. 108). Now, however, the earlier expression of joie de vivre has given way to a mood of

Figure 163

Lovis Corinth, Chrysanthemums , 1922. Oil on canvas, 97 × 78 cm, B.-C. 852.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (5101).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

Figure 164

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Artist's Son, Thomas , 1921.

Oil on canvas, 87 × 65 cm, B.-C. 835. Staatliche Museen

Preússischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie, Berlin

(West) (B 549 Kat. 34)

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

profound melancholy. Except for the large showy blossoms of the amaryllis, the flowers are for the most part appropriate to the girl's own stage of life: clusters of lilacs, a small vase with lilies of the valley, and a pot of red tulips that Wilhelmine holds in her hands. As in the independent still lifes with flowers, the blossoms appear as if dissolved from within, as patches of black paint push through the variegated colors. And as in similar compositions by Degas, the young girl has been relegated to the extreme side of the pictorial space. She gazes earnestly at the beholder; her body and face have been accommodated both coloristically and texturally to the flowers as if to emphasize their common fate.

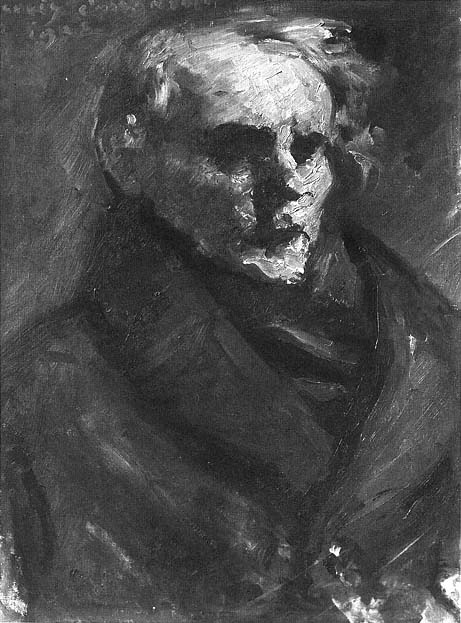

Similar analogies between the life of nature and human life unify a group of plein air portraits and self-portraits painted at Urfeld (B.-C. 835, 837, 838,

Figure 165

Lovis Corinth, Small Self-Portrait at the Walchensee , 1921. Oil on canvas,

68 × 80 cm, B.-C. 845. Private collection.

Photo courtesy Werner Timm.

845, 863, 871, 925, VII). In these the facial traits of the sitters are, for the most part, subordinated to the all-consuming outdoor light. Even in close-up views, as in the portrait of Thomas from the summer of 1921 (Fig. 164), the colors are freed from their purely descriptive function. Wearing Bavarian lederhosen and a Tyrolean hat, Thomas sits on the terrace of Haus Petermann, enveloped in dazzling light that etches itself into his skin and dissolves his face, hands, and body in a burst of incandescent color. In the still more extreme close-up view of Corinth's self-portrait from the same summer (Fig. 165) the head has been accommodated to the structure of the terrain. The surface of the entire canvas has been transformed seemingly into a molten mass, and the textures are dominated by the tactile character of the paint itself.

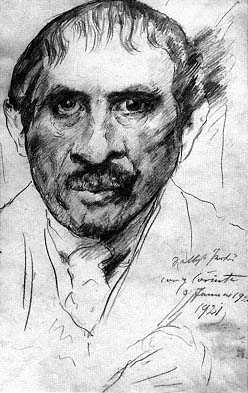

Figure 166

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1921. Pencil,

44.5 × 28.0 cm. Kunsthaus Zurich (1924/10).

This painting, executed on Corinth's sixty-third birthday, is only one in a series of self-portraits from 1921 in which he explored with ever new variations the threatening signs of his progressive physical deterioration. Always observed from up close, the face as depicted frequently differs markedly from Corinth's own. Each self-portrait is like a fragmentary thought, determined by the mood of a given hour rather than by any quest for conventional verisimilitude. In that sense, these self-portraits are truly images of Corinth's inner life. As was the case in the development of the Walchensee landscapes, watercolors lead the way. In a sheet from January (see Plate 31) the expression of a moment is reinforced by the asymmetrical placement of the head; the wild, aggressive gaze finds its pictorial equivalent in the tortuous paths of the colors. It is as if Corinth had flung the colors at his mirror image in disgust. Dingy shades of red, green, gray, and brown are enlivened sparingly in the shirt by the white paper ground. The only truly glowing colors are the touches of cobalt blue in the eyes and at the nostrils and the speck of bright red in one corner of the mouth. In a pencil drawing from the same month (Fig. 166) the contemptuous fury of the watercolor has given way to a more controlled ex-

Figure 167

Lovis Corinth, Death and the Artist ,

1920–1921. Soft-ground etching and

drypoint, 28 × 18 cm, M. 546. Staatliche

Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz,

Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (West).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

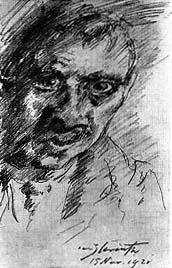

Figure 168

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait ,

1921. Pencil, 22 × 14 cm.

Graphische Sammlung

Albertina, Vienna.

pression of resignation and sadness. The head slants toward the left, but the modeling and the emphatic contour around the face are executed with deliberate care. Corinth's gaze is both attentive and distant, intent on grasping the image but also reflective and inward. One eye remains focused on the subject, the other, noticeably enlarged, has an eerie, visionary glow. The drawing is closely related to a similarly poignant etching of about the same time, entitled Death and the Artist (Fig. 167). The print includes a human skull and a more mundane memento mori symbol in the form of a watch prominently displayed on the artist's wrist. The print is the first in a cycle of six etchings that make up Dance of Death (M. 546–551), in which each episode illustrates a prototypical stage of human life: men and women, alone and in pairs, in youth, in the prime of life, and in old age, face the specter of their inevitable mortality. In the self-portrait drawing of November 15 (Fig. 168) the impression is again that of a barely controlled inner crisis. The slashing lines betray considerable agitation. Although the eyes and the nose retain their definition, the right side of the face is distorted as in a curved mirror, and the form begins to scatter with centrifugal force.

These self-portraits indicate Corinth's dread of old age and decrepitude. They are silent moans, similar in their emotional range to the confessions that fill the later pages of his diary. There too, he poured out his fears of impending senility, his intermittent feelings of self-doubt, and his anguish at the political turmoil of the postwar years, although the very uncertainties of the period sometimes also aroused him to bouts of renewed purpose, as if his work could save both himself and the German nation. "As long as I can walk on this earth and am able to work," Corinth wrote in 1922, "I shall go on painting as I always have. I don't think anyone will be able to say that I was untrue to myself. . . . Maybe I will be praised someday as a soldier who has remained steadfast at his post." At the end of the year he laments the loss of the political stability that had prevailed in the old empire: "I have lost the ground from underneath my feet. I am floating on air and don't feel about art as strongly as I used to." But he quickly rallies: "Would energy help? I am determined, and nothing shall prevent me. Germany shall still be proud of me. . . . I can work better and longer than a young man." A paragraph written on January 11, 1923, concludes: "Never will I allow my God-given talent to be destroyed. I am going to stand my ground and still produce so much that the world will be astonished. The country is crushed. 'Let's get on with the work!'" In subsequent entries from 1923 this optimism gives way to despondency and despair:

There has not been a day in my life when I was not tempted to make an end of it. . . . I discovered that my painting is indeed nothing but rubbish. Life is pointless, without any hope, a black curtain. . . . I rage at myself and at my work. Forgetting my better judgment, I feel like screaming forth at the world: What do you see in a wretched fellow like me! Can't you tell that I don't amount to anything —that I am no artist, nothing! I am desperately discouraged—I cannot see a ray of sunshine anywhere around me; my life has been wasted. The thought of putting an end to it haunts me.

But this pessimistic outburst, too, concludes more reasonably:

Paroxysms . . . always abate. It would be terrible otherwise, and as with a convalescent, one's spirits gradually revive. There is soon joy again in working; indeed, in time one rediscovers one's self-respect through one's work and whispers when nobody is listening: "You are quite a fellow."[15]

The extremes of Corinth's emotional life give all his works from these years their true content. Even the late landscapes and still lifes share in this process of self-revelation. Although still dependent on nature, alternately tender, euphoric, and desolate, they owe more to the painter's inner life than to optical verity. For that reason alone his late work cannot be labeled Impressionistic, the more so since the term is hardly applicable to much of his earlier output. At most Corinth sought to reconcile Impressionist techniques with a deliberately conceptual approach. As Bernard Myers so aptly says of these late works, "The representational is only a point of departure for a . . . metaphysical analysis proceeding from the emotions."[16]

The Red Christ

The figure compositions to which Corinth had once turned so frequently on account of their "universal human" significance, diminished in number as landscapes and still lifes became more meaningful in personal terms. In 1919 there were still six such paintings, but in 1920 and 1921 there were only two for each year. In 1922 there is only one, The Red Christ (see Plate 32), surely Corinth's most horrific interpretation of the subject. The simplified composition as well as the searing nature of the conception is anticipated in the watercolor of 1917 (see Fig. 136), which may well have served as a model for the painting. In the painting, however, the scene is considerably enlarged: Longinus, in the lower left corner of the panel, pierces Christ's side with a lance; another soldier, in the lower right corner, holds aloft the sponge soaked in vinegar offered to Christ just before he died. The figures of the two thieves who were crucified with Christ are dimly visible in the two upper corners. In the middle ground, at some distance, Saint John supports the Virgin, who is overcome with grief.

Although the traditional features of the scene are thus all recognizable, the painting is nonetheless no more a narrative than the watercolor of 1917. The emaciated figure of Christ, seemingly suspended from the picture frame rather than from the cross, is splayed across the pictorial field like some hieroglyphic symbol of pain. The colors have been smeared on the panel in thick globs, then scraped and scumbled with the palette knife and the brush. Virtually everywhere there are spurts of bright red.

The individual faces, like masks, embody a wide range of psychological states: evil, indifference, compassion, and unspeakable horror. Just as Christ's

Figure 169

Lovis Corinth, Crucifixion , 1923. Lithographic

crayon, 63 × 50 cm. Staatliche Museen, Berlin

(DDR).

Figure 170

Lovis Corinth, Death of Jesus , 1923. Lithograph, 50 × 64 cm, M. 694.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1961/234).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

body dominates the pictorial structure, so the howling darkness of his countenance governs the painting's terrifying mood. What personal anguish must have motivated so gruesome a conception! Not even Beckmann or Nolde, who years earlier had turned to Christ's Passion in their search for paradigmatic examples of man's suffering, ever managed to approach the intensity of Corinth's brutal image of pain. The only valid comparison is with Matthias Grünewald, who has left us similarly memorable depictions of superhuman agony.

In a crayon drawing of 1923 (Fig. 169) Corinth returned to the subject of The Red Christ in slightly modified form. Here the individual figures appear as if floating in a spatial void. Like vapors that congeal temporarily, they are about to vanish. The drawing evidently served as a study for the lithograph Death of Jesus (Fig. 170) of the same year. Although in the print the narrative has been considerably amplified, here, too, the palpable character of Corinth's earlier compositions of this type has given way to the allusive expressiveness of his late style.

Late Graphics and Graphic Cycles

The homogeneity of form and expression in Corinth's paintings, drawings, and prints of this time ushered in yet another phase in his graphic output. Almost as if he intended to measure the distance he had traveled, or—more likely—propelled by a compulsive need to recast his earlier extroversive art into the emotive pictorial language of his late style, he resumed the habit, first noted in his graphic production from 1914, of reworking some of his earlier paintings in his late drawing style. A cycle of thirteen etchings of 1919, entitled Ancient Legends (Schw. 351), includes nine such repetitions. Among the four additional repetitions of the same year are new versions of the very early Swimming Pond at Grothe (B.-C. 72) of 1890 (Schw. 363) and the successful Salome (see Plate 12) of 1900 (Schw. 367). Corinth's prints of 1920 include new renditions of his two Salon entries, Susanna in Her Bath (see Fig. 34; M. 465) and the prize-winning Pietà (see Fig. 33). In the print after the Pietà (Fig. 171) he virtually tore to shreds the "corpse of Christ on a red tile floor" that for so long had not satisfied him with respect to "form." The climax of this compulsive revision of earlier work was reached in 1921–1922, when Corinth published a group of ten etchings under the title Compositions (M. 553–565), each based on one of his typical earlier exhibition pieces, including the painting Entombment (see Fig. 95) of 1904. His new approach to this particular work

Figure 171

Lovis Corinth, Pietà ,, 1920. Drypoint, 26.5 × 32.7 cm,

M. 472. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1929/138).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

Figure 172

Lovis Corinth, Entombment , 1920–1921. Drypoint, 21 × 31 cm., M. 556.

Landesmuseum Mainz, Graphische Sammlung.

is of special interest because as his point of departure for the print (Fig. 172) he selected not the finished painting but the life-size cartoon that had preceded it (see Fig. 97). Nothing could reveal Corinth's intention more clearly, for, having singled out this particular drawing, surely one of the most idealized human figures in his entire oeuvre, he proceeded to repudiate the academic nude that had preoccupied him for so many years.

The maturing of Corinth's late graphic style coincides with an impressive output of illustrations for biblical, historical, biographical, and other literary texts. As a result of the publication of Karl Schwarz's catalogue in 1917, a general appreciation for Corinth's printed graphics had developed. Several subsequent publications by the same author,[17] culminating in 1922 in a second, much enlarged, edition of the catalogue, stimulated interest in Corinth's graphic production still further. As the attention of print collectors grew, so did the business acumen of publishers of print portfolios and illustrated books. The Fritz Gurlitt Press and the Propyläen-Verlag in Berlin, F. Bruckmann in Munich, and E. A. Seemann in Leipzig were among the firms with which Corinth signed contracts for a variety of projects. In addition to individual prints and such series as the Walchensee views, the Ancient Legends, Compositions , and the Dance of Death cycle already mentioned, he completed between 1919 and 1923 no fewer than twenty other print portfolios and illustrated books comprising nearly four hundred etchings and lithographs. Among these are Anne Boleyn (Schw. L428, L429) and a sequel of prints illustrating scenes at the court of Henry VIII (Schw. L430). Although the Anne Boleyn series was for a text by Herbert Eulenberg, much of the inspiration for both cycles came from the filming of the story—with Henny Porten and Emil Jannings in the leading roles—which Corinth was invited to watch at the Babelsberg Studios in Potsdam.[18] Illustrations for three poems, Friedrich von Schiller's Der Venuswagen (Schw. L383), Gottfried August Bürger's Die Königin von Golkonde (M. 499–511), and the Dafnislieder of Arno Holz (M. 733–743), revive memories of Corinth's earlier sensuous art. Like the contemporary Love Affairs of Zeus (Schw. L401), they include captivating scenes of lovers locked in rapturous embrace. The provocative character of the actions depicted in the illustrations to Schiller's poem (Fig. 173) is underscored by pithy inscriptions.

Corinth also illustrated some of the great classics: Shakespeare's King Lear (M. 491–498) and Schiller's Wilhelm Tell (M. 775–796), Die Räuber (M. 797–808), and Wallensteins Lager (M. 809–814). Twice he turned to the story of Götz von Berlichingen, first in 1919, when he made illustrations to Franz von Steigerwald's 1731 biography (Schw. L399), which had already inspired the young Goethe, and again in 1920–1921, when he illustrated the text of Goethe's

Figure 173

Lovis Corinth, Venus Finger , from Der

Venuswagen: Ein Gedicht von Friedrich

von Schiller, 1781 , 1919.

Photo courtesy Hans-Jürgen Imiela.

Figure 174

Lovis Corinth, Frederick the Great on His

Deathbed . Color lithograph, 32.3 × 25.3 cm, M.

618; from the cycle Fridericus Rex , 1922 (M.

593–640). Staatliche Museen Preussischer

Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (West).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

drama (M. 512–538). The life of Martin Luther, with a text by Tim Klein (Schw. L444), also dates from 1919. In 1922 Corinth completed his most extensive single cycle, Fridericus Rex (M. 593–640), a set of forty-eight color lithographs published in two portfolios.[19] The engaging narrative tone of this cycle and the whimsical exaggerations of physiognomy and gesture—as in Corinth's illustrations of 1923 for Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (M. 641–666)—are reminiscent of Corinth's earlier parodic Tragicomedies (see Figs. 42–50).

At the same time, the choice of such protagonists as Luther, Götz, and Frederick the Great implies again a measure of self-identification with embattled German heroes. This is further supported by several more self-portraits in armor, one decorating the title page of the Anne Boleyn series (Schw. L428, II), a Flagbearer of 1920 (Schw. 396) and a Victor of 1920–1921 (M. 564), the latter two done after earlier paintings (see Figs. 105, 106). The first Götz cycle begins with a repetition of the painting of 1917 (see Fig. 153), showing the aged warrior seated at his desk, writing his memoirs (Schw. L399, III). In the next-to-last print Götz has laid aside his armor and halberd (Schw. L399, XVI); the inscription beneath the illustration reads in translation: "Everyone will know what pain I have suffered." For the episode in the second cycle where Götz resists his captors (M. 530), Corinth drew on his earlier portraits of Rudolf Rittner in the role of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16, Fig. 127).

The first portfolio of Fridericus Rex emphasizes Frederick's endurance in the face of misfortunes: the traumatic conflicts between the young prince and his father; the First Silesian War; and Frederick's severest test, the Seven-Year War against the coalition of Austria, Russia, and France. The next-to-last print, inscribed "La montagne est passé/ 17 August 1786," shows the monarch on his deathbed (Fig. 174), a subject often depicted by other artists, usually to preserve a historical record of the dying king surrounded by attendants and members of his court. Corinth's only interest, however, is the deceased monarch, stripped of the accoutrements of the royal household. The dead king's face is based on the death mask in the Hohenzollern Museum that Corinth had drawn as early as September 1908.[20] During the war, in 1915, he had painted a picture of the death mask, starkly contrasting light and shade (B.-C. 653). The motif recurs in the second portfolio of Fridericus Rex (M. 637), followed by illustrations of the empty sedan chair in which the ailing king was carried (M. 638) and Frederick's disembodied uniform and hat, supported by the lifeless armature of a mannequin (M. 639). In 1923 Otto Gebühr, who played the title role in the hugely successful Fridericus films produced at about that time, gave Corinth a copy of Frederick's death mask, which the painter promptly displayed in his studio.[21]

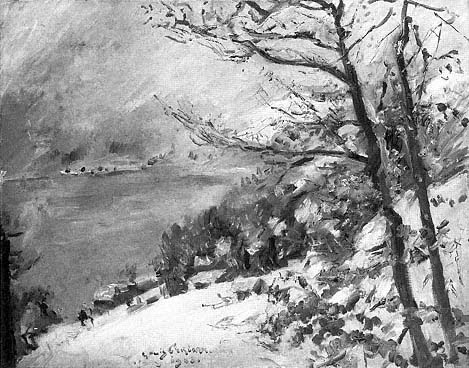

Figure 175

Lovis Corinth, The Walchensee in Winter , 1923. Oil on canvas, 70 × 90 cm, B.-C. 897.

Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt (SG 1132).

Corinth's Altersstil

Corinth's print portfolios and book illustrations clearly went a long way toward compensating for the diminished number of figure paintings after 1919. Walchensee landscapes and still lifes continued to dominate his watercolors and oils. This intensive preoccupation with nature, the need to capture a momentary sensation quickly, seems in turn to have contributed to yet another stage in the evolution of Corinth's late style. Although there are antecedents, even a cursory look at his pictures from 1923 reveals a more consistently fluid application of paint. The colors seem to have been laid on in caressing strokes, and even the dabs of impasto seem light. Brushed into each other right on the canvas, the colors yield transitional hues, often of great delicacy. Like a living, moving substance, they ebb and flow across the pictorial field, producing the impression of a mysterious connection of all material substance. It is as if Corinth were no longer looking at but through nature, as through a translucent veil.

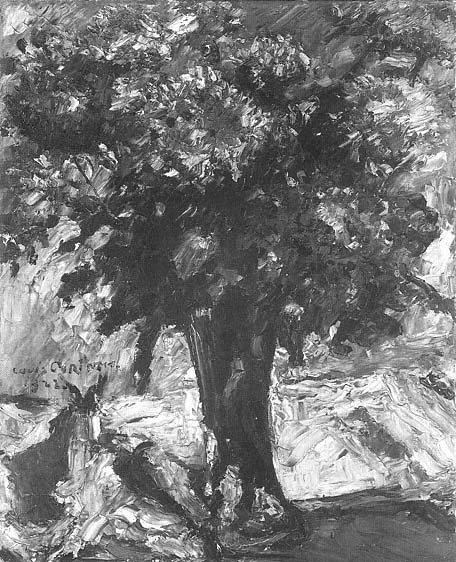

Figure 176

Lovis Corinth, Tree at the Walchensee , 1923. Oil on canvas, 70 × 91 cm,

B.-C. 930. Kunsthaus Zurich (2417).

Photo: Walter Drayer.

The winter landscape in Frankfurt (Fig. 175) dated January 1, 1923, is one of these works. It is a painting of extraordinary structural and coloristic simplicity. It could almost be called monochromatic were it not for the pale violet of the clouds, the pale blue of the frozen lake, and the bronze-brown hues of the leaves still clinging to the trees on the right. The luminous white of the snowy landscape nonetheless unifies sky, lake, and terrain, and the constant blending of tones and the fluid treatment heighten the pictorial unity still further. Throughout, the landscape is so expressive of atmospheric life that one can almost feel the clammy air of the winter day. In the Walchensee landscape in Zurich (Fig. 176), a painting of great pictorial richness and emotional appeal, there is both drama and lyrical calm. A barren tree stands out against the luminous distance, its winding branches evoking both struggle and endurance. Several features contribute to the painting's suggestive power: the magnificent blue that unites sky, mountains, and lake; the misty forms of the

Figure 177

Lovis Corinth, Unter den Linden, Berlin , 1922. Oil on canvas,

70.5 × 90.0 cm, B.-C. 893. Von der Heydt-Museum der Stadt

Wuppertal, Wuppertal-Elberfeld.

houses by the edge of the water, which seem to float as in a mirage; and the opalescent luster of the tree itself, its trunk and branches sparkling with color as if still pervaded by a mysterious inner life.

In two contemporary city views of Berlin even the urban landscape appears similarly transfigured. The visual sensations of the crowded boulevard Unter den Linden (Fig. 177), viewed from the second floor of the Restaurant Hiller in 1922, yield a panorama of blurred accents reminiscent of similar paintings by the French Impressionists. Unlike Monet and Pissarro, however, Corinth imposed the ceaseless change of color on the pictorial structure: the pronounced diagonal of the tree-lined street seems to exert a gravitational pull, and everything slants precariously as if about to fall, the façades of the houses as well as the mighty columns of the Brandenburg Gate.

Even in the close-up view of the Berlin royal palace (Fig. 178), the tactile substance of mortar and stone has given way to the diaphanous texture of the picture surface. Although seen head-on and occupying virtually the en-

Figure 178

Lovis Corinth, Schlossfreiheit, Berlin , 1923. Oil on canvas,

104 × 79 cm, B.-C. 894. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz,

Nationalgalerie, Berlin (West).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

tire pictorial field, the building remains strangely disembodied. With its architectural elements dislodged, its structure shifts. The cupola sits askew above Eosander von Göthe's sumptuous gateway in the west front facing the Schlossfreiheit, literally "freedom of the palace," so named for the remission of taxes that earlier inhabitants of the palace grounds enjoyed. Reinhold Begas's monument to Wilhelm I, the founder of the Second German Empire, looms in the right foreground, separated from the deserted palace by a dark canal that seems to tunnel directly beneath the building. The inconsequence of the palace's tangible character to Corinth is indicated by his affixing his signature and the date of the painting to the swaying entablature of the façade.

The same allusive transparency makes itself felt in Corinth's late still lifes. It no longer matters what flowers are depicted (Fig. 179) or whether a still life is of fruit or of cuts of meat and fish arranged in a bowl or on a kitchen counter. In every instance the substances dissolve into a coruscating display of color.

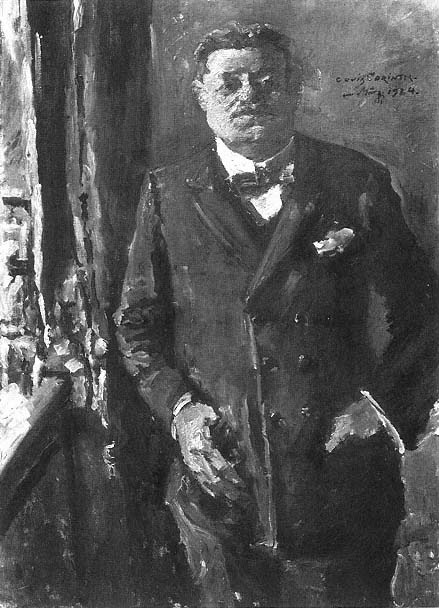

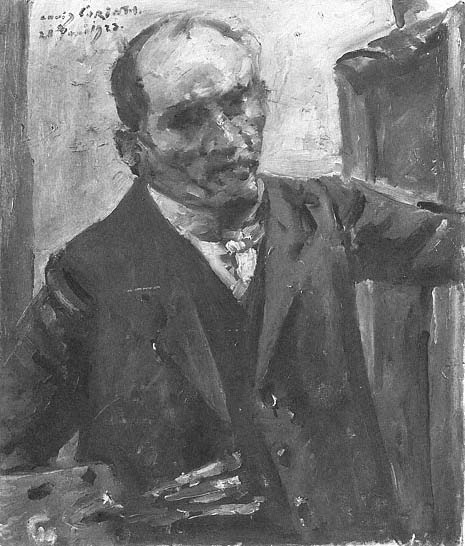

Because color also preponderates over physical resemblance in Corinth's late portraits, in all his work after 1922 there is only one truly formal portrait. The other portraits—of colleagues, friends, and members of Corinth's immediate family—were all painted on his own initiative. These too, pervaded by Corinth's awareness of his increasingly frail condition, are really expressions of his own self and thus among the most explicit statements of his mature conception. Three compelling examples date from 1923. In the portrait of the Russian painter Leonid Pasternak (see Plate 33), the father of the famous poet and novelist, the sitter is seen from up close in a casual pose, arms folded across his chest. Light tones predominate, their oscillating life reinforced by the vivid brushstrokes, in keeping with what by all accounts was a strikingly debonair appearance. Yet in the shadows of the mouth there is a disturbing darkness; the eyes appear clouded and dim; the skull seems to protrude right through the eroding texture of the skin, giving the face a mocking, indeed sinister, expression.

Leonid Osipovich Pasternak (1862–1945), who had settled in Berlin in 1921, had written to Corinth to express his admiration for works of the painter he had recently seen, most likely at the former Kronprinzenpalais, where in the summer of 1923 the National Gallery featured a large exhibition of Corinth's work, drawn entirely from private collections. Corinth replied by asking Pasternak to come and sit for the portrait, complimenting the Russian on his good looks. "Were I a woman," Pasternak wrote to a friend on July 18, 1923,

Figure 179

Lovis Corinth, Spring Flowers in a Fluted

Vase , 1924. Oil on canvas, 61 × 41 cm, B.-C.

937. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

"I would have been proud."[22] On December 2 he described Corinth's work on the portrait in greater detail:

When he was painting me, the expression in his eyes was almost terrifying! Whether it's the result of his illness or of an intent fixation on his subject, he is beginning to squint; his left arm is paralyzed, so he presses the palette convulsively to his body; he stands there bowed down, perhaps trying to overcome superhuman torment. And for three hours at a stretch he stands like this in front of his canvas.[23]

Pasternak, in return, painted Corinth with palette in hand, stooped, working at the easel, his eyes fixed on the subject with fierce determination. But Pasternak's own ingratiating style could hardly communicate "superhuman torment," and consequently the expressive character of his portrait of Corinth remains somewhat forced.[24]

Corinth's awareness of human transience, so eloquently expressed in the diaphanous structure of the Pasternak portrait, reaches a point of passionate

Figure 180

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Alfred Kuhn , 1923.

Oil on cardboard, 61 × 51 cm, B.-C. 915. Private

Collection, Austria.

Photo courtesy Bernd Schultz.

defiance in the portrait of Alfred Kuhn (Fig. 180). Here the figure has been pushed to the extreme side of the composition. Torso and ground, with the same textural characteristics, flow into each other in a torrent of brushstrokes. The head, stretched out of shape, dissolves between a burst of light and the silvery gray pallor of the colors. Kuhn, who at the time was preparing his monograph on the painter, was fully aware of the extent to which Corinth had come to see in nature a mere pretext for revealing the world of his imagination:

For the old Corinth the world was only a shell inhabited by a slowly disintegrating body, only an opportunity to receive new inspirations for visions of color. When one sat opposite him during these last years and talked to him, one soon became aware that the conversation did not interest him in the least, that his gaze, so firmly fixed, was not intended for anyone in particular, and it could happen that Corinth would suddenly say such things as, "Hold still, that yellow forehead interests me," or "What a strange color there is in your eyes right now."[25]

Among the most remarkable of all of Corinth's late works is his portrait of the Norwegian painter Bernt Grönvold (Fig. 181). The two had first met at the Académie Julian but had not seen each other in fifteen years. When Grönvold (1859–1923) called on him in his Berlin studio, Corinth was struck by the old

Figure 181

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Painter Bernt Grönvold , 1923.

Oil on canvas, 80 × 60 cm, B.-C. XX, Kunsthalle Bremen (683-1953/22).

Figure 182

Lovis Corinth, Susanna and the Elders , 1923. Oil on canvas, 150.5 × 111.0 cm,

B.-C. 910. Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 123/1954).

Figure 183

Lovis Corinth, Susanna and the

Elders , 1898 and 1923. Pencil and

watercolor, c. 44.0 × 34.5 cm. Present

whereabouts unknown (see Fig. 68).

Photo courtesy Thomas Deecke.

friend's altered appearance and immediately asked to paint him. Dressed in a curious old-fashioned coat tailored to his own specifications, the eccentric Norwegian consented, but he requested that Corinth not paint his eyes. The portrait was completed in a matter of two hours, and Grönvold left without giving it even a glance, professing later that since he had asked Corinth not to paint the eyes, he did not think that he had the right to look at the painting. When he saw the portrait by chance a short time later, he exclaimed in surprise: "Why, I look like a ghost!"[26] Grönvold does indeed inhabit a world whose mystery can hardly be fathomed. The colors are muted: against the overall tonality of blue, gray, and black the pale skin tones and wisps of white hair stand out in an eerie light. The deathly pallor of the complexion is relieved only sparingly by touches of red in the right ear and temple and in Corinth's signature and date on the picture. The visionary quality of the portrait is intensified by the greenish blue haze of the background. It is actually impossible to speak of figure and ground as separate since they share the same amorphous texture. As the skull is revealed beneath the skin, the cavities fill with impenetrable shadows. It is as if a human life were being slowly extinguished. Grönvold died, apparently unexpectedly, not long after the portrait was painted.[27]

Twice in 1923 Corinth turned to figure compositions that had last occupied him many years earlier, in each case rejecting the academic principles that had governed such compositions before to achieve the final sublimation of his earlier sensuous style. He began Susanna and the Elders (Fig. 182) by adding to the drawing of 1898 (see Fig. 68) a watercolor wash (Fig. 183). This draw-

ing was unusual because it anticipated the expressive vigor of Corinth's more mature works; thus it was apparently no accident that the painter found the sketch still useful a quarter of a century later. In the painting itself, however, the baroque qualities of the drawing—exploiting movements and gestures and light and shade for picturesque effects—have been replaced by an action that is essentially static. At the same time there is a more profound human implication in the way Susanna, shielding herself with her robes, stands defiantly before her would-be seducers. Hers is a heroic courage summoned in the face of the greatest possible odds. The voluptuous form of the female nude still contains the memory of Corinth's earlier displays of feminine allure; but now the texture of the flesh is subordinated to the breadth and vigor of the painterly treatment. The drama of the action, too, is vested in the life of the paint itself—impressively so, since the three figures are approximately life-size. Creamy shades of pink and rose, accented with touches of white, gray, and pale blue, stream downward from the upper part of the composition. Near the lower margin and on both sides, the forms dissolve into pure abstractions.

The much smaller panel Birth of Venus (see Plate 34) similarly goes back to a work from the 1890s (see Fig. 61), although a watercolor from 1916 (Fig. 184) may have served as a less distant mediator. In any event, the earlier memories of Botticelli, Bouguereau, and Böcklin have been drowned in color. The colors, in turn, are expressive rather than descriptive. It is hard to imagine a more apt pictorial equivalent of the goddess's miraculous birth than the radiant blues, pinks, and whites that Corinth whisked up with the aid of the palette knife. But Corinth himself continued to see the painting primarily as illustrative. He would often look at it and remark with amusement: "The cupids are really flying."[28]

The ambivalence between form and formlessness gives Corinth's late work its particular tension. It is an ambivalence, however, only for the viewer—not, evidently, for the painter himself. As late as 1920, in the third edition of his teaching manual, Corinth still defined painting as an art "that reproduces on a two-dimensional plane what the eye sees in nature." He goes on to say that "all objects that are freestanding in nature must be made to appear three-dimensional and surrounded by light; the properties of the terrain, and everything that is in it, must be arranged in relation to one another, all the way to the horizon, so that a projection of depth is achieved."[29] These, of course, are Corinth's words to the beginner; he encourages the experienced student "to throw all caution to the wind, to follow his instincts and finish the painting in a few hours."[30] Mistakes are excused as long as the character of a given

Figure 184

Lovis Corinth, Birth of Venus , 1916. Pencil,

crayon, and watercolor. Dimensions and present

whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Marburg/Art Resources, New York.

image has been captured. "No spot in a painting must lack life," he concludes; "a picture is finished when it is painted well. . . . even a well-painted sketch is finished."[31] In short, Corinth ultimately gives priority to the process of painting without abandoning subject matter altogether.

Corinth's late paintings often balance "on the edge"[32] between formation and dissolution. This process has meaning to the extent that it reflects the painter's innermost disposition. Carmencita (see Plate 35), the last portrait Corinth painted of Charlotte Berend, is a good case in point. The origins of the portrait were innocent enough: a costume ball at the Berlin Secession on February 28, 1924. Charlotte was dressed in the traditional gown of a Spanish woman. Corinth's costume was improvised more casually: with a fake beard, a red scarf around his waist, and a Christmas tree ornament pinned to his

chest he looked, perhaps, like a caricature of a high official. In her recollections of the evening Berend could not help acknowledging the disparity in age between herself and her husband:

For me this was the first time that I could try out the steps of the new dances. I looked pretty stylish and danced . . . with one partner after another. In the process I completely forgot my obligations to Corinth. I caught a glimpse of him once in a while as he sat by himself, abandoned, old, and lonesome . . . ; I had the gnawing feeling that I should really join him, but then I kept forgetting it, for hours on end. . . . By closing time . . . he said, "Now you are going to sit down for a while." That I did, and my admirers came buzzing to the table and buzzed off again when they heard that for this evening I was through dancing.[33]

A few days later Charlotte asked Corinth whether he felt like painting her in the handsome Spanish dress. No prompting was needed. With the glowing lights of the chandelier in the couple's living room setting a festive tone, Corinth completed the portrait in two short evenings. To stay in character, Charlotte kept chanting melodies from Bizet's Carmen . The painting itself, however, is far from lighthearted. To be sure, the colors are exhilarating, and the room behind Charlotte glows. The brushstrokes reinforce the scintillating life of the colors, following, as in many of Corinth's late works, a predominantly diagonal direction from the upper right to the lower left. In addition, there are independent brushmarks of varying strength and direction. Passages of heavy impasto vie with dabs of great transparency, so that the pictorial structure seems perpetually to ripple. The figure of Charlotte, shown life-size, is pushed close to the picture frame. Her ebullient temperament, her capacity for living life to the fullest, even the formidable strength of her personality find eloquent expression in her opulent appearance. To that extent the painting might be called the culmination of Corinth's portraits of Charlotte as well as a document of a particular way of life.

The painting is also, however, a farewell, for its initially festive mood does not withstand prolonged scrutiny. Despite Charlotte's implied physical presence, there is no real physical substance. For all its massiveness the figure succumbs to the labile character of the pictorial structure; the lower half of the figure in particular seems to sag. Although from a distance the facial expression seems aloof, the features are far too blurred to be psychologically accessible. It is as if Charlotte had receded into a world the painter no longer shares. As Hans-Jürgen Imiela has aptly observed, Corinth's Carmencita has "something of the character of a widow's portrait."[34]

There is a similar ambivalence about Corinth's portrait of Wilhelmine (Fig. 185), painted in July 1924. Nothing could evoke better the bloom of youth than the white frills of the dress accented with tones of pale yellow, lime green, and rose. Yet the figure is seen as through a veil; the features grow indistinct as if the girl were no more than a distant vision.

Whatever the personal implications for the old painter, both the Carmencita portrait and the portrait of Wilhelmine were conceived in accordance with a fundamental distinction—today it would be called sexism—that Corinth advocated in portraits of women as opposed to portraits of men. "In the case of men," he writes in his teaching manual, "interest will be in the spiritual physiognomic character, in sensitive hands, in a peculiar posture whereas in portraits of women, concern will be more with the effect of the colors. A man must always be interpreted more from an intellectual point of view, a woman more decoratively."[35] This distinction explains why even Corinth's earlier portraits of Charlotte, no matter how sensitive, show her most often in the stereotypical roles of lover, wife, and mother and only rarely as a professional artist in her own right. The emphasis on the cerebral component in male sitters, in contrast, accounts in the late works for such striking, if overwrought, physiognomic studies as the second portrait of Herbert Eulenberg (Fig. 186). Here the poet's inner radiance breaks through the fragile shell of the body; the eyes glow feverishly, wide open as if he were entranced by a horrible vision.

From 1924 on virtually all of Corinth's male sitters share this terrified expression. The most notable exception is the portrait of Friedrich Ebert (Fig. 187), the first president of the Weimar Republic. Although the technical execution does not differ fundamentally from that of other paintings of the same year, the conception is formal, evidently precluding a more personal treatment. The portrait was painted on Corinth's initiative. By his own admission, he was intrigued by Ebert's "fascinating ugliness."[36] Without diminishing the coarseness of the features, he nonetheless stressed the innate dignity of the saddler-turned-statesman. Ebert's humble origins, in fact, endeared him to Corinth: "I don't want to deny that I found in him a man whom, on account of my own background, I understood better than the titled and the rich. I find people of my sort easier to deal with."[37] By the time Corinth painted the portrait he had learned to accommodate himself to the republic. Whereas in 1918 he had lamented the spread of socialism in Germany, Ebert was for Corinth now the embodiment of the new order and thus worthy of the same respect the painter had formerly accorded the emperor. "I did not see in Ebert the social democrat," he wrote in his diary, "but the head of the German state."[38]

Figure 185

Lovis Corinth, Wilhelmine in a

Yellow Hat , 1924. Oil on canvas,

85 × 65 cm, B.-C. 947. Museum für

Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Lübeck.

Figure 186

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Herbert

Eulenberg , 1924. Oil on canvas, 60 × 49

cm, B.-C. 952. Kunsthistorisches

Museum, Vienna (NG 51).

Corinth had met Ebert informally on a number of occasions. At one of Ebert's receptions the critic Paul Fechter was also present. When he noticed that Corinth was having difficulty lighting a cigar, he rushed to help him, a gesture that the painter acknowledged gratefully. Fechter's subsequent account of the episode is also one of the most moving descriptions of the old Corinth:

The way he looked at me was really the most unforgettable part of this small incident. His broad peasant face, which had never acquired the look of a Berliner, was dominated by two beautiful brown eyes. They were the eyes of a sick, wounded animal . . . filled with the silent moan: "I cannot go on any longer." They were the eyes of a painter. . . . of a man who in his suffering was absorbing the world only passively, who could no longer grasp, hold, and form the world according to his own will but had to accept what was offered, who was no longer even master of himself and his body. This was the gaze of one . . . who has . . . only lived for the visible, and who now, without any words, silently acknowledged with these eyes the smallest kindness shown to him. They took possession of my face. I could feel how for one brief moment he fixed the image in his mind with all his power. But then the silence and the sickness of the animal came once again to the fore, as if he were already far removed from the world of those around him and no longer shared anything with them but that certain waiting for something.[39]

Figure 187

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Friedrich Ebert , 1924. Oil on canvas, 140 × 100 cm,

B.-C. 968. Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Kunstmuseum (1699).

While Fechter's eloquence bears the stamp of poetic license (Corinth's eyes, for example, were blue, rather than brown), the fundamental truth of his observations is corroborated by others who encountered the painter during these years. Wilhelm Hausenstein was struck at about the same time by Corinth's way of observing the world around him, the eyes far apart, as if seemingly no longer looking in one direction:

Under his gaze life parted like a curtain, and in the center there was something like the silhouette or the shadow of death. . . . I shall remember this gaze in the hour of my own death; this is how one sees when the world is dissolving. Then one looks not only into depths that were previously hidden but also to both sides—things become deep, and they become wide; they reach to the left and to the right, and the sides, too, become depths.[40]

Far less poetically, Karl Schwarz bluntly calls Corinth a "gruff man" whom illness had turned into a "wreck."[41] Likewise, Alfred Kuhn, who saw Corinth often in connection with the monograph he was then preparing, describes him as a "stooped man" with an "emaciated body, . . . a shuffling walk, and trembling, red, swollen hands." "Listening to his halting, grumbling speech," Kuhn continues, "one would scarcely have thought that this was one of Germany's greatest living artists. But seeing him at some public function, . . . sitting up straight, one was tempted to think of the old Rembrandt: the same ragged features, the same expressive mouth, . . . and the same faraway gaze."[42] Both Kuhn and Schwarz, however, make the point that Corinth's frailty in no way hindered his productivity. Kuhn speaks of "miraculous works" created by the "helpless hands of an old man."[43] Schwarz writes of the astonishing energy Corinth summoned while painting: "When he stood before the easel, it was as if a vulcano erupted. He flung the paint at the canvas, groaned and moaned, cursed and thundered, totally oblivious to the world around him."[44] In the excitement of painting, moreover, Corinth surmounted his impediments by resorting at times to impromptu measures as long as they yielded the desired results. Rudolf Grossmann, one of the younger members of the Berlin Secession, whose portrait Corinth painted in 1924 (B.-C.965), writes: "He knows how to take advantage of his diminished locomotive powers. . . . His hand gropes about on the palette and gradually turns as red as madder. . . . Often he uses the other trembling hand like a mahlstick for support to give a particular tone greater definition. . . . At the end, after two and a half hours of uninterrupted work, . . . he lowered his hands; they were as red as blood, as if he had burrowed into my intestines."[45]

Late Self-portraits

At this time in his life painting was for Corinth no longer just a calling or an occupation but a necessity; not merely a way of life but a way to survive. He needed to work, if only to maintain his inner balance. Corinth's late self-portraits give a vivid account of his emotional disposition. As always, they are rooted in a search for truth and an intense integration of his physical and psychic life. Some are pervaded by an undertone of resignation. But again and again the painter rallies and confronts himself, pencil or palette and brushes in hand, in a renewed gesture of self-challenge. In the self-portrait of June 21, 1923 (Fig. 188), Corinth is a quiet, thoughtful observer of his appearance. While the right arm, reversed in the mirror image, suggests the momentary action of painting, the face mirrors both sadness and fatigue. Broad patches of light and dark merged by fluid halftones render the textures indistinct; the forms seem about to dissolve.

Exactly a month later, on his sixty-fifth birthday, Corinth painted himself again at the Walchensee (Fig. 189). The eyes are clear, the face smooth, the expression probing but unhampered by fear or skepticism. Unlike the first Walchensee self-portrait of 1921 (Fig. 165), the painting asserts the figure's independence vis-à-vis the terrain. Corinth towers above the lake, like the old tree in the Walchensee landscape of the same summer (see Fig. 176), impaired but not yet beaten. How quickly, however, his moods tended to change is evident from a long lament in his diary, written not long after the completion of the self-portrait. Dismissing any claim to "virtuosity," he speaks of the "sicknesses," the "paralysis," and the "awful tremor of the right hand" that made any technical display in his late work impossible.

A constant ambition to achieve a goal I never reached has made my life bitter, and each piece of work ended in depression when I thought of having to continue this life! To be sure, whenever I compared my work with that of others, it seemed to me that I was as good as or better than anyone else. . . . Liebermann once told me that one must have everything to discover how unimportant everything is. For my part, however, I am sickened by everything. I don't even want to have what I still could achieve because it disgusts me already. Perhaps it is the sad state of Germany today that bears responsibility for this disgust. The times for us old ones have changed so much. . . . it's wretched. . . . most sad, very sad. And the future is hidden by the darkest curtain.

Corinth then goes on to praise Charlotte Berend for having made his anguish bearable. Calling her his "guardian spirit," he concludes: "People will have

Figure 188

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Palette , 1923. Oil on canvas, 90.2 × 75.5 cm,

B.-C. 916. Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (2457).

her to thank if in my later days I still managed to produce a few good things."[46]

The self-portrait of April 1, 1924 (Fig. 190), now in New York, mirrors the ambivalence of Corinth's thoughts. The face speaks of both apprehension and resolve. There is something defensive about the stooped posture, an impression reinforced by the palette, held perpendicular to the picture plane like a shield. The pictures displayed in the background press hard upon the painter. Cramping his field of action, they are also a reminder of an obligation not yet entirely fulfilled.

Figure 189

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat , 1923. Oil on cardboard,

70 × 85 cm, B.-C. 925. Kunstmuseum Bern (1488).

Figure 190

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Palette , 1924. Oil

on canvas, 100.0 × 80.3 cm, B.-C. 967. Collection, The

Museum of Modern Art, New York

(Gift of Curt Valentin).

If the New York self-portrait suggests constriction and weary vigilance, the self-portrait (see Plate 36) Corinth painted at the Walchensee on July 21, 1924, his sixty-sixth birthday, conveys openness and serene assurance. The physical energy required to paint the life-size picture in the heat of the midday sun, to haul the heavy canvas intermittently indoors to examine the effect of the colors in a more diffuse light, as Charlotte Berend relates,[47] must have been formidable. Corinth does indeed seem rejuvenated. He stands erect, his shirt inflated by a breeze; his face aglow with sunshine; his gaze attentive, absorbed not by self-scrutiny but solely by the painterly task at hand. Although he stands high above the lake, painter and landscape are unified. The green of the trees and the meadow and the blue of the lake, mountains, and sky have invaded the shadows of the trousers and the shirt, where they are complemented by stripes of red, purple, yellow, and brown. The warm tones find their greatest concentration in the skin tones, which stand out resonantly against the cool ground of the landscape. "This portrait contains all of Urfeld," Charlotte Berend writes in her diary, "the wind, . . . the radiance of summer in all its fullness and bliss."[48] Many years later she recalled that Corinth told her at that time, "I want to live to be seventy. I still don't have any wrinkles or a single gray hair on my head. I would like to paint myself with a wrinkled face and white hair; that would make a completely different picture."[49]

"True Art Means Seeking to Capture the Unreal"

Corinth had hardly finished the self-portrait when he was already at work on the splendid still life of larkspur (see Plate 37). The bouquet was a birthday gift from Wilhelmine, and the large dimensions of the painting lend the simple flowers an appropriately festive air. As in the Walchensee birthday self-portrait, warm and cool tones complement each other. There is also an unexpected renewed commitment to interior space. The checkered table cloth and the window framed by a white lace curtain convey something of the room's rustic charm. Yet structural ambiguities, as nearly always in Corinth's late works, prevail: the vase leans toward the right, and there is a notable divergence between the left and right corners of the table and between the window-sill and window frames. In the end, however, these instabilities are resolved in the stalks of the flowers radiating outward from the very center of the composition. The result is a dynamic equilibrium that defies the logic of statics.

Figure 191

Lovis Corinth, Walchensee: View from the Kanzel , 1924. Oil on canvas, 100 × 200 cm,

B.-C. 955. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

During that summer Corinth also painted seven Walchensee landscapes. These included two nocturnes (B.-C. 953, 954), two views of the Jochberg (B.-C. 956, 958), and a view of the lake shrouded in morning fog (B.-C. 959). The most unusual of all is the large panorama (Fig. 191), now in Cologne. Like the preceding birthday self-portrait and the still life of larkspur, the painting conveys a sense of serene detachment. The landscape is actually made up of two views: at left, a corner of the northeast shore, the green island of Sassau, and the Hotel Fischer am See; at right, toward the southwest, the slope leading up to the Herzogstand. On the opposite side of the lake lies the extended chain of the Karwendel, and almost in the center of the canvas, unifying the composition, Corinth's favorite larch tree stands on its own promontory overlooking the water. The brushstrokes are vivid but of a uniformly soft texture that enhances the breadth of the view and contributes to the impression of an all-pervasive calm. One is tempted to call the landscape "classical," so much does the painting depend on both the ordering of human reason and the laws of nature.[50]

Figure 192

Lovis Corinth, The Trojan Horse , 1924. Oil on canvas, 105 × 135 cm, B.-C. 960.

Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie,

Berlin (West) (NG 1522; A II 488).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

Corinth's love of a good story depicted with verve revives briefly in The Trojan Horse (Fig. 192), painted in the fall or early winter of 1924. The subject is rare in art, perhaps because the story lacks a major human character. Corinth, too, was forced to select a subplot of the epic to highlight the drama of deception and folly. Facing the gate of the walled city, the sham animal stands stiffly by the seashore. Two derelict boats, left behind by the Greeks, lie in the shallow water nearby, their prows pointing no less menacingly in the same direction. All the action centers on the lone Greek who professes that he was abandoned by his compatriots on the beach. Having been captured by a small advance troop of Trojans, he tells them the story of the curious idol as Odysseus had instructed him to do. Two armed warriors