VII—

Later Speculum Editions

The continued popularity of the Speculum humanæ salvationis is evident from the remarkable number of incunabula editions issued before the end of the fifteenth century. No less than sixteen were published by eleven printers, in Latin, Dutch, French, and German, all with woodblock illustrations.[1] The first of these was printed by Günther Zainer in the Benedictine Abbey of SS. Ulrich and Afra at Augsburg, together with another work intercalated into the chapters of the Speculum . The Latin text is printed beneath the woodcuts, followed by a translation of the chapter into German, and then by pages of the Speculo Sanctae Mariæ Virginis , a metrical summary, by Brother Johannes of the Abbey.

Günther Zainer, first known as a scribe, was a famous printer of Strassburg. About 1468 he moved to Augsburg, where the guild of woodcutters tried to prevent him from getting a permit to print, but then allowed him to do so if his books were not illustrated. Later, through the intervention of the powerful Melchior, the Abbot of SS. Ulrich and Afra, he received his regular license on condition that he use only woodcutters belonging to the guilds, although it is said that he was capable of cutting blocks himself. The Abbot set up a press in the monastery in order to avoid the control of the guilds, and there Zainer printed an illustrated edition of the Speculum in 1473. It included forty-five chapters, 192 fine new woodcuts (fig. VII-1), fifteen of which are repeated, and it was rubricated throughout. The unity of character between Zainer's type and the blocks has caused the book to be called one of the most beautiful of incunabula to be created in Northern Europe.[2] The inventory made about the middle of the

[1] Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut (1935; reprint New York, 1963), p. 811. To Hind's list must be added the 1498 edition, printed by André Bocard at Paris for Durand Gerlier; the two printed by Johann Schönsperger at Augsburg in 1492 and 1500; and the edition of 1492, printed by Michel Greyff at Reutlingen.

[2] Alan G. Thomas, Great Books and Book Collectors (London, 1975), p. 49.

century by Jean Schlipat, listing the books in the monastery, included a copy of the Speculum of forty-five chapters and it may be assumed that it was used by Zainer as printer's copy.

The enlightened Abbot Melchior invited a succession of Augsburg printers to direct and instruct his monks. Johann Baemler and Anton Sorg printed, with their own types, at the Abbey in the same year as Zainer, 1473, and in succeeding years. Zainer produced a number of other important illustrated books at Augsburg, many with blocks by the same artist who illustrated his Speculum edition. His blocks for the Speculum vitæ humanæ were used in Reinhard's Lyon edition of 1482 and in the Hurus edition of 1491 at Saragossa, which demonstrates how commonly the woodcuts for popular books travelled from one printer to another.[3]

The Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis , a German translation of the Speculum which issued from the press of Bernhard Richel in August 1476, was the most important early book to be printed at Basel. It had a new set of vertical woodcuts, partially derived from Zainer's blocks, but more directly influenced by the Biblia pauperum . They are placed in the double-column text wherever a new subject begins rather than at the head of the text columns (fig. VII-2).

In the same month and year, Anton Sorg in Augsburg printed an edition of the German translation with cuts also based on Zainer's blocks. Sorg was the most prolific of the printers in that busy center. He produced more than a hundred illustrated books between 1475 and 1493, but in the quality of cutting, their illustrations are below the standards of Zainer and Baemler.[4]

The first illustrated book to be printed at Lyon was a French translation of the Speculum , made by the Augustinian monk Brother Julien Macho from the Basel German edition. Entitled Le Mirouer de la Redemption , it was issued by Martin Huss in 1478 with the blocks of Richel's edition (fig. VII-3). The work must have been extremely popular in France, as elsewhere, for he republished it in 1479 and 1482, and his kinsman, Matthias Huss, printed editions in 1483 and 1484.

At Speier, Peter Drach printed three editions of the Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis , in 1478 (fig. VII-4), 1481, and 1495, using blocks whose design has been attributed to the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet (the Master of the Hausbuch).[5]

[3] A. W. Pollard, "The Transference of Woodcuts in the XV and XVI Centuries," in Bibliographica, II (1896), p. 343.

[4] Hind, op.cit. , p. 295.

[5] Ibid. , p. 346.

VII-2.

The Fall of Lucifer, Chapter I a.

The Creation of Eve, Chapter I b.

Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis , Bernhard Richel, Basel, 1476.

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, 105168.

VII-3.

Adam Toils and Eve Spins.

Cain Kills Abel. In the background they are at the altar with their offerings.

Le Mirouer de la Redemption , Martin Huss, Lyon, 1478.

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, 105169.

VII-4.

Moses and the Burning Bush, Chapter VII b.

Gideon's Fleece, Chapter VII c.

Rebecca at the Well, Chapter VII d.

Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis , Peter Drach, Speier, 1478.

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, 104026.

As for the woodcuts of the Speculum blockbooks, they were preserved, if our surmise is correct, at a community of the Devotio moderna near Louvain. It was at Louvain that Jan Veldener set up his original printing equipment and there issued the Fasciculus temporum , dated 29th December, 1475.[6] It was the first printed book, after the Speculum , with woodcut illustrations to be produced in the Low Countries.

[6] Wytze and Lotte Hellinga, The Fifteenth-Century Printing Types of the Low Countries (Amsterdam, 1966), I, p. 18.

Veldener is also known to have supplied type and printing equipment to the Brethren of the Common Life in Brussels, and probably set up their press which was the first printing workshop in that city. Their community was known as Nazareth, or as the House of the Annunciation, and thirty-six editions were issued from it between 1474 and 1485.[7] It is an attractive thought that out of appreciation, if not obligation, perhaps the Congregation at Brussels or at Groenendael rewarded Veldener by turning over the Speculum woodblocks to him after the last edition was printed about 1479. In any case Veldener had moved to the bishopric of Utrecht in 1478 where he printed two editions of the Epistelen en Evangelien . For the third edition, in 1481, he used two of the Speculum blocks sawed in half, the cuts for the Last Judgment, and the Wise and Foolish Virgins.

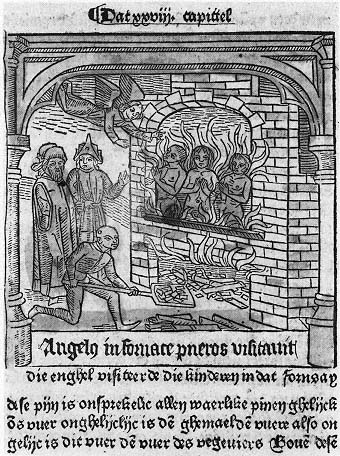

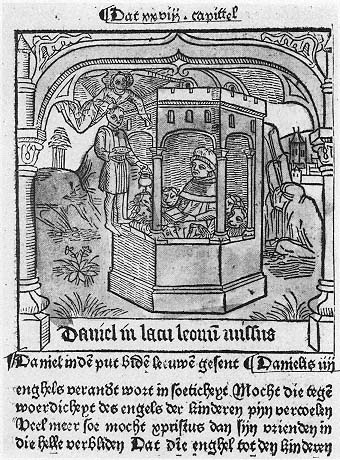

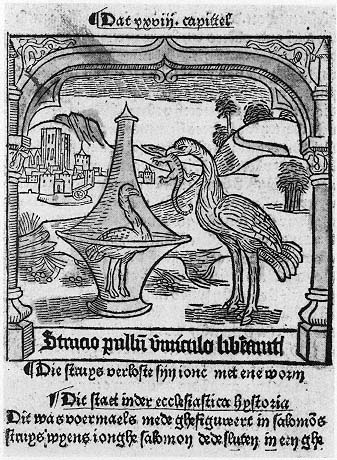

Because of the ecclesiastical conflicts in Utrecht, he soon took refuge at Culemborg, and there, in 1483, printed a Dutch translation of thirty-two chapters of the Speculum , entitled Dat Spieghel onser behoudenisse , using the woodcuts from the blockbooks, cut in half, as noted earlier, and eleven more by the second artist/cutter of the Speculum (fig. VII-5). The source of the Dutch text for these three added chapters is unknown. Deviating from the pattern of the Latin manuscripts, Veldener substituted for the first half-block of Chapter XXV (properly the scene of the Synagogue deriding Christ) the Crucifixion scene, which he had also used in Chapter I in place of the Fall of Lucifer. Chapters XXVIII and XXIX of the manuscript texts, omitted in the blockbooks, are also included with their appropriate woodcuts. The sturdy blocks were not, however, laid to rest yet. In 1484, after his return to Louvain, Veldener used two of them in his edition of Herbarius in dietsche , or Kruidboeck .

At Lübeck in about 1483, Lucas Brandis printed a Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis with many crude and angular illustrations in woodblocks.[8] Another Augsburg edition of the Spiegel printed by Peter Berger appeared in 1489, with illustrations that follow the Richel subjects and are even more directly influenced by the Biblia pauperum .[9]

[7] Elly Cockx-Indestege, "Les Frères de la Vie Commune à Bruxelles," in Le Cinquième centenaire de l'imprimerie dans les anciens Pays-Bas (Brussels, 1973), p. 196.

[8] William Martin Conway, The Woodcutters of the Netherlands in the Fifteenth Century (1884; reprint Hildesheim, 1961), p. 13.

[9] Hind, op.cit. , p. 364 and p. 326.

VII-5.

An Angel Visited the Boys in the Furnace, Chapter XXVIII b.

Daniel in the Lions' Den, Chapter XXVIII c.

The Ostrich Liberated Her Young from the Glass

with a Reptile's Blood. Chapter XXVIII d.

Dat Spieghel onser behoudenisse , Jan Veldener, Culemborg, 1483.

New York Public Library, Spencer Collection, NETH 1483.

VII-6.

Balaam and the Angel, Chapter III d.

The Birth of Mary, Chapter IV a.

Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis , Johann Schönsperger, Augsburg, 1492.

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, 101922.

Johann Schönsperger, another Augsburg printer, was one of the most prolific producers of illustrated books of the period, but many of his woodcuts were copied from, or had been used in other printers' issues of the same texts, not the least of which were his three plagiarized editions of the Nuremberg Chronicle (Koberger, 1493).[10] He printed two editions of the Spiegel , one in 1492 (fig. VII-6) and one in 1500, but the source of his blocks is unknown.

Very few editions of the Speculum were printed in the sixteenth century, for the change in religious and intellectual climate and the rise of Humanism and Protestantism gradually undermined the popularity of the typological treatises.

We have attempted to trace the steps in the metamorphoses of the Speculum humanæ salvationis from its fourteenth-century Latin manuscripts into the gloriously illuminated French translations for ducal courts, and their models; then, with the advent of the woodcut and of movable type, its appearance in the four editions of the blockbooks; and finally, its many letterpress editions with woodblocks and text printed in the press.

[10] Adrian Wilson, The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle , 2nd edition, revised (Amsterdam, 1978), p. 191.

Epilogue

The Speculum was also the source for works in many art forms, among them medieval tapestries at La Chaise-Dieu in the Auvergne; stained glass at Mulhouse, Colmar, Rouffach, and Wissembourg in Alsace; and sculptures at Vienne near Lyon.[11] In individual woodcut prints it appears in the form of a hand (fig. VII-7), presumably used as an aid to prayer. Four examples are preserved, each from a different woodblock.[12] At the top of the print reproduced here is an almost indecipherable text from the Bible, above a large hand with an inscription at the joint of each finger and a banderole at each tip. On either side of the wrist is the Latin text, translated as follows:

|

The fingers are flanked by Maria Magdalena with an ointment jar, and Maria Martha using an aspergill which is attached by a rope to a bulldog (or dragon?). This is presented here as a final benediction to our study.

[11] Robert A. Koch, "The Sculptures of the Church of Saint-Maurice at Vienne, the Biblia Pauperum and the Speculum humanæ salvationis ," in Art Bulletin, XXXII (1950), pp. 151–55.

[12] Hind, op.cit. , p. III.

VII-7.

Speculum humanæ salvationis in the form of a hand, 1476.

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, H. 60.