2

Mapping the City

Guide-books, Wellingborough, are the least reliable books in all literature; and nearly all literature, in one sense, is made up of guidebooks.

Herman Melville, Redburn

On 2 Pluviôse, Year II of the republic (21 January 1793 on the prerevolutionary Gregorian calendar), Louis Capet was driven from the Prison du Temple to what had been inaugurated as the Place Louis XV but was then the Place de la Révolution (and would subsequently become the Place de la Concorde). The journey lasted nearly two hours. The closed carriage and its full military escort passed through streets lined with citizens armed with spikes and guns. The beating of drums attached to the horses muffled any possible expression of sympathy for the man who had been Louis XVI, the sixth member of the House of Bourbon to reign as King of France and Navarre, great-great-great grandson of Louis XIV, the monarch known as the Sun King. At the scaffold, the condemned man asserted his innocence and absolved his executioners, but his attempts to say more were stifled by more drums. The deed accomplished, the severed head was paraded before the impatient bystanders whose shouts of "Vive la liberté" and "Vive la république" brought to a close this performance of what Michel Foucault so aptly called the "Spectacle of the Scaffold."[1]

The personal and dynastic drama and its compelling political consequences consumed observers at the time and focused commentary on the properly national significance of the execution. For in beheading the king, the Revolution simultaneously abolished a central symbol of country and obliterated a vital emblem of the city. It is those urban consequences, the crisis of authority that necessitated redefinition of the city, that concern this chapter. Once the king's city—the city earlier kings ritually appropriated as "our good city of Paris"—Paris became the city of the Revolution. But what did, what

might that mean? Whose "good city" would Paris be henceforth? At least since the sixteenth century, monarch and inhabitants alike had boasted of Paris as the "capital of the kingdom." Was it also the capital of the Republic? Decapitation deprived the city of a chef, of its symbolic head. Paris became an organism without a head, truncated, incomplete, in sum, a monstrosity. So strong was the association of the city and the monarchy, so visible the imprint of royalty on the topography and the toponymy of the city itself that the execution made much of Paris a symbolic nonsense. Clearly, the crown and the fleurs-de-lys that figured on the seal of the city had to be discarded. But what would replace them? Whose city was it? Who now would, or indeed could, comprehend it? The city, in a very real sense, had to be rewritten before it could once again be read.

Most obviously, one regime took over from another and went about the business of creating institutions and ideologies in its own image. Accordingly, revolutionaries destroyed a number of the more egregious emblems of the past (the term vandalism was coined at the time). But transition entailed more than demolition. Given the imprint of the monarchy upon Paris, iconographic regeneration posed problems of major proportions. The Revolution had somehow to accommodate the past. The execution of Louis XVI functions as a larger symbol of urban crisis, one that bespeaks an immediate need for symbolic re-representation, a drastic rewriting or resymbolization, of the urban text.

Writers of many different persuasions and commitments took up this challenge in the nineteenth century. Claiming a new authority over the city as text, they sought to guide their readers through the newly unfamiliar passages of the city and to explain, if possible, its disconcerting capacity for continual change. The role of guide through a fearful place was not, of course, a new one. Virgil's guidance of Dante through hell supplied the model regularly invoked through the centuries, and never more insistently than in the first part of the nineteenth century, when Paris itself reverberated from the repeated, and intensified, disruptions of revolution. The writer simply assumed, or arrogated, the intellectual authority to map the postrevolutionary city.

That authority was necessarily also political, so nineteenth-century writers cast themselves in a position of leadership, guiding readers through the perilous territory that only they knew as they insisted it

be known. The special relationship of the writer and the city does not originate in this postrevolutionary period, but it is then that writers learned to press their claims with especial urgency. There was a void to fill, and it was filled by the self-conscious authority of the author and by texts that presented themselves as authoritative. The nature and the consequences of this immense self-confidence are prime elements in an understanding of the urban discourse that began to emerge in early nineteenth-century Paris. The stories that the city came to tell, in new genres like the guidebook and eventually the novel, became part of its history, just as the history of the city was integral to the very notion of the genre. The urban discourse elaborated in nineteenth-century Paris builds on just this crosscutting of genre and history. The Revolution made the interaction of the two more obvious, and more imperative, but the relation was already well established by 1789.

I

Naître à Paris, c'est être deux fois Francais.

Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris

To be born in Paris is to be doubly French.

No city exists apart from the multitude of discourses that it prompts. Topography is textuality. One reads the structured space of the city as one reads the structured language of a book. But more than analogy is at work in this dual textuality. In the modern city the two models of urban texts—the "text" of the physical city and the writings about that city—coincide, overlap, comment upon, and at times contradict each other. This intertextuality becomes increasingly intricate as the city expands, builds, and demolishes and as writing about the city draws upon ever more diverse, ever more sophisticated, and ever more established traditions of texts. As these urban texts become more various, meaning proliferates and turns the city into a palimpsest, that is, a textual expression of the labyrinth. Indeed, readings of the palimpsest weave the magic thread that enables the individual to find a way through the labyrinth.

Such reading requires guidance of a sort different than the directives proffered in more conventional narratives. As early as the mid-sixteenth century, it became evident that the city of Paris needed

another kind of narrative to make sense of its increasing diversity. There was no lack of histories and legends and myths to trace the origins of the city and of its name. In fact, chronicles of ritualized praise had been part of a Parisian discourse for centuries. But these celebrations of Paris make no connection to the explicitly topographical expositions like Guillot's Dit des rues de Paris at the very beginning of the fourteenth century. The guidebook as it took shape in the early nineteenth century emerges from the conjunction of these two very different urban texts, the chronicle and the topographical exposition. But the genre that arises from this alliance does not merely join one text to another. More than juxtaposition is at work. For the guidebook to take its place among city texts first requires that the city as a whole be rethought.

Like most practitioners of the genre since, the authors of these early guidebooks assume that unmediated contact with the city is inadequate at best, and probably dangerous as well. The frequency of reference to Paris as hell in the nineteenth century—it was a cliché by the time Balzac got to it in the 1830s in his celebrated opening of La Fille aux yeux d'or—bespoke a pervasive fear in a city beset by evils with unknown consequences. The writer of a guidebook supplied the essential link between text and reader and between city and inhabitant. Gradually, the nineteenth century raised this affinity between the writer-guide and the city to a principle of literary-urban conduct. The literary guidebook became a characteristic genre of postrevolutionary Paris.

Under the ancien régime, guidebooks were less complex undertakings. To the extent that the control of proliferating meanings was less problematic in the ancien régime, it derived from the increasing emphasis on the imposition of royal authority. Guidebooks undertook to define the city in terms of the evolving landscape of power and to direct attention to the sacred geography of monarchical Paris. The importance of the postrevolutionary literary guidebooks can be gauged only against the background of three centuries of guidebooks that magnified the monarchy. Like the postrevolutionary battles over street names, the reconceptualization of the guidebook, its promotion to something of a literary status, went hand-in-hand with the far larger work of reconceiving city and country after the Revolution.

Appropriately enough, the first guidebook of Paris appeared only four years after François I officially settled in his "good city" of Paris

and two years after publication of the first map of the city. In 1532 the bookseller Gilles Corrozet printed what seems to have been the first guidebook of Paris. La Fleur des antiquitez de Paris (The Flower of Parisian Antiquities ) set a model that served for two centuries and more.[2] Corrozet elaborates in specifically topographical terms the extension of monarch's authority over the city of Paris that is illustrated so strikingly in the evolution of the seal of the city. The original seal, that of the water sellers, dating from the early thirteenth century, shows the simplest boat, emblem of the water merchants' trade. A century later, the seal of the Prévôté des Marchands, the overall municipal governing body, displays the same boat, but with the significant addition of two fleurs-de-lys above the now full (though still single mast) sail. In this way, the monarchy literally impresses its signature on the seal of the city.

Corrozet follows this lead, insisting upon the connection between all the inhabitants of the city, but particularly that between the bourgeois and the king, who now honors the city with his presence. In what we might now call a semiotic analysis of the Paris seal, at the end of La Fleur des antiquitez de Paris Corrozet lists the inhabitants who count: "men of learning, . . . merchants, . . . priests, bourgeois, nobles, clerics, and men of arms." Yet Corrozet begins by placing his work under the aegis of the king. He will, he notifies the reader at the outset, first present the history of the city and then "all the most laudable things accomplished in Paris by princes and kings, and all the edifices made by them from the time that it was first inhabited until the time of the very Christian king of France, Francis the First of this name." He ends with a truly marvelous genealogy that traces the reigning king, François I, back to Paris, son of Priam, thereby substant iating the legendary origin of the city in the royal line of Troy and, incidentally, making good on his dedication of the work to the "Nobles, bourgeois, of Greek or Trojan origin." The forced conjunction of bourgeoisie and monarchy stands as a reminder that the decision of François I in 1528 to settle in Paris is determined by his need for the funds that only the city fathers could supply. It is, then, entirely appropriate that Corrozet's analysis of the city seal should see the boat on the seas as a sign of "inestimable wealth."

The first edition of La Fleur des antiquitez de Paris follows the tradition of the chronicles. It is all legend and history and testimonial

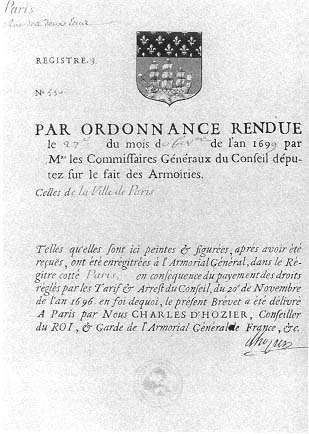

Plate 2.

Seal of Paris, 1699. The seal as officially registered under Louis XIV,

with gold fleurs-de-lys against a blue field over the merchant ship representing

Paris, on a silver sea against a red background. The superimposed fleurs-de-lys

signaled the dominion of the king over the city. The ship first appeared

in the thirteenth century as the sign of the Water Merchants Guild and,

hence, of the commercial vocation of the city. The fleurs-de-lys first appeared

on the seal in the fourteenth century. (Photograph by the University of

Chicago Medical Center, A.V. Department.)

about the city and contains no topographical information whatsoever. Corrozet was an astute bookseller who identified a market and at the same time created a genre. Accordingly, the second edition, which he brought out only a year after the first, turned La Fleur into a true guide to urban space. To the legends, history, chronicles, poems, anecdotes, heraldry, and epitaphs of the great, Corrozet added important topographical information, notably lists of all the streets, churches and colleges in the city. The next twenty years saw a total of five reprints of the 1533 edition, the last two with an updated list of streets and other relevant topographical details.

In 1550 Corrozet printed the far more substantial Les Antiquitez, histoires, croniques et singularitez de la grande & excellente cité de Paris, ville capitalle & chef du Royaume de France (The Antiquities, Histories, Chronicles, and Singularities of the Great and Excellent City of Paris, Capital City and Head of the Kingdom of France ) which he dedicated not to the bourgeois of La Fleur but to "the noble and illustrious Families of Paris." So great is Corrozet's pride of place—Paris is "the most magnificent, largest, most populous and sovereign city of France, indeed of all Christendom"—that he admonishes Parisians for their ignorance of :heir city. It is not enough, Corrozet impresses upon readers who might be tempted to shirk their duties as Parisians, to declare peremptorily that one is from such a place. One must be able to discuss its "prerogatives and beauties," and these, in Corrozet's Paris, are once again the work of the monarchy. He claims the honor of writing for "the very Christian Crown of France & the exaltation of your families," and Les Antiquitez stresses more than the earlier La Fleur the debt of city to the monarchy. From the buildings the first kings built to the tombstones and epitaphs that their successors dedicated to them, Corrozet explains, "you will find how much our Kings have enriched and decorated this capital city with privileges, with buildings, and with their own persons, even after their death," the last in reference to all the "sepulchres and epitaphs" promised in the subtitle. Les Antiquitez too enjoyed considerable success. Corrozet printed a second edition in 1561, and another bookseller brought out a third edition in 1577, after Corrozet's death.

Later guidebooks celebrate the monarchy in a more sophisticated mode, but celebration it remains. François Colletet organized the Abrégé des annales de la Ville de Paris (1664), as the subtitle of the work tells us, by the successive reigns of French kings. It was entirely logical

as well as absolutely appropriate for Germain Brice, author of the most popular guidebook of the century—nine editions and five reprints between 1684 and 1752—to begin his tour of Paris with the official residence of the king in Paris, the Louvre, "the most remarkable place, which is the principal ornament of the city by its vast extent and by the quantity of edifices of which it is composed."[3]

As the growth of the city modified urban space, urban genres began to specialize. Serious historians too confronted the varied strata of urban topography and toponymy. Thus Henri Sauval's Histoire et recherches des antiquités de la ville de Paris (1724) quickly became the standard to which later generations (including Victor Hugo for the documentation of Notre-Dame de Paris ) would return again and again. Other works addressed other uses of the city. Compendia of various sorts emphasized the practical, supplied street names and useful addresses, and included summary statistics for the individual who needed to negotiate the city while contemplating its past glories.

The guidebook proper occupies a space between these two poles of past and present. It usually presents a historical sketch of some sort—the term antiquités, so important for Corrozet, continues to figure in numerous subtitles—along with a modicum of more or less useful information. Whatever the specific orientation, from history to almanac to guidebook in the broadest sense, these urban genres sought to systematize as well as to glorify and to make it possible for readers to make their way around the city.

In 1759 and 1760 two works appeared, by the same author and with almost the same title, that point to the prevailing sense of the guidebook as an urban genre. M. Jèze's 1759 Tableau de Paris offers above all information. It is resolutely tied to the present, since the material consists of, as Jèze announces in the preface, "the details most subject to variation." The author offers his Tableau as a "work that is useful for some, necessary for others." Jèze invites readers to help him keep subsequent editions up to date. The 1760 État ou Tableau de Paris is by design not a history (Jèze cites Sauval) and not a description (he cites Corrozet and Brice) but rather a state (état) of knowledge about the city. This is a book to be used, to be studied, and to depend upon (it is at once a "book for use, for research and for commodity"). Jèze insists again and again, here in his "Preliminary Discourse," on the systematization of the information that he provides. That information, much of it familiar from the 1759 Ta-

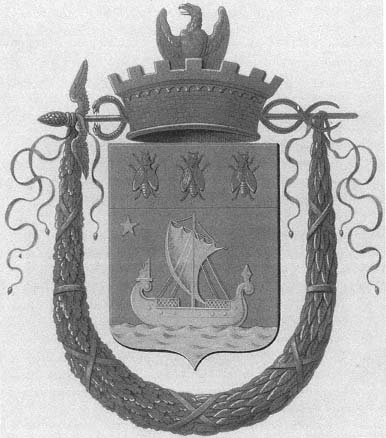

Plate 3.

Seal of Paris, 1811. In the First Empire, the fleur-de-lys and the blue

of the monarchy disappear in favor of the eagle and bees associated with

Napoléon. The Egyptian goddess Isis on the prow of the ancient, silver ship

against a red background brings the Egyptian military successes of Napoléon

in full view as well as the classical associations with imperial Rome, which also

conquered Egypt. The other parts—the crown that recalls a fortified castle,

the eagle, and the two garlands (oak leaves on the left, olive leaves on the

right) tied by red ribbons—were shared by all French cities of the First Order

(bonnes villes ). (Photograph by the University of Chicago Medical

Center, A.V. Department.)

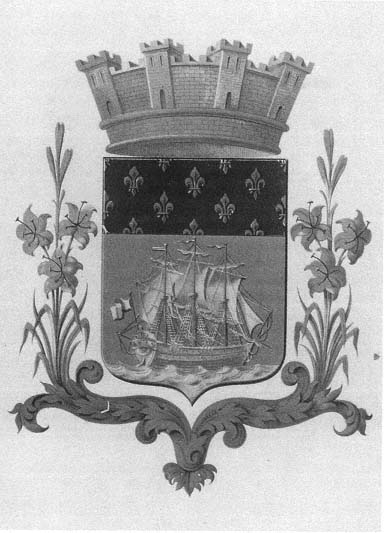

Plate 4.

Seal of Paris, 1817. The monarchy that returned to France after

Waterloo replaced the Napoleonic eagle and bees with the emblems

of the ancien régime. The seal reproduced the basic 1699 escutcheon

but replaced the ship with an elaborately rigged military vessel and

retained for the outer section the now familiar château-crown, while

adding lilies to recall the flowers with which Parisians greeted the

return of Louis XVIII. (Photograph by the University of Chicago

Medical Center, A.V. Department.)

bleau, is presented systematically. The goal is not simply to supply more information but to present a rational system of knowledge about the city. As the subtitle tells us and a large fold-out map graphically illustrates, the city is "considered relative to the Necessary, the Useful, the Agreeable, and the Administration." If the last category seems somewhat anomalous in the series, Jèze, in his 1759 Tableau, makes a point of signaling, among the many claims of Paris to preeminence, "the wisdom of its Government and its Police."[4]

These urban works and others that followed served the larger purposes of government insofar as they fit within the larger goal of rationalizing the city and bringing it, and its sometimes rebellious inhabitants, under control. Whether or not they articulated these urban concerns, the guidebooks participated in the work of the monarchy, even as the king moved the court from Paris to Versailles. They fixed its imprint in a written text that would survive topographical and social change. By virtue of being systematically organized in a text, street names, monuments, statues, and other urban icons acquired a permanence that guaranteed their survival as text even as the city itself altered, built anew, and modified urban space. The guides fixed the city and in so doing arrested potentially idiosyncratic definitions of place. So usual do these administrative prerogatives appear to the latter-day reader that we forget just how recent the notion of a fixed urban text is. Guidebooks, histories, and practical compendia comprised but one element in the fixing of that text, but they were an important element, indeed, all the more so for the indirect nature of the connection they compelled.

II

Variété, mon sujet t'appartient.

Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris

Variety, my subject belongs to you.

The struggles over the designation of city space gave a distinctly urban resonance to the larger political conflicts that played out in postrevolutionary France. The successful contestation of authority opened the city to redefinitions from every quarter. The execution of one king and the defeat and subsequent flight of his successors in

1814, 1815, 1830, 1848, and 1870 dramatized the fragility of political authority. Having lost its central authority, the urban symbol system fell into disarray. Into this void, writers stepped with surprising assurance to assert the authority of the written word to interpret the modern city and the society that it both represented and expressed. In this continually manipulated urban space, guidebooks found a ready market, among the provincials arriving in Paris to undertake the work of the new representative government and among a good many others hopeful of profiting from the new state of affairs. Parisians themselves, many of whom seldom ventured outside their neighborhood, stood in need of instruction. They were often lost, as Mercier noted before the Revolution, in the swelling multitude of provincials and foreigners. Native and visitor alike desperately needed direction in the changed and rapidly changing milieu. If this need was apparent to Mercier in the very last days of the ancien régime, it was palpable after the Revolution and in the new century.

Not the least problematic aspect of the new Paris was its inhabitants. The Parisians of the revolutionary and postrevolutionary eras were not those of prerevolutionary yesterday. Indeed, description of place presented less of a challenge for the urban accountant than did analysis of people. If writings in and about postrevolutionary Paris went on at length about the "ruins" of the old Paris, the psychic emphasis nevertheless fell on the new city, and particularly on the changed and changing customs (moeurs ) that characterized that city. One P.-J.-B. Nougaret presented his Paris, ou le rideau levé' in 1798 "to serve the history of our former and present customs." In Paris à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (1801),J. B. Pujoulx opened the century with promises of a "historical and moral sketch" of monuments and ruins, disquisitions on the state of science, art, and industry, "as well as the Customs of its inhabitants." In 1814 Louis Prudhomme's Voyage descriptif et philosophique de l'ancien et du nouveau Paris announced not only "historical facts and odd anecdotes about the monuments" but also much concerning the "variation of the customs of its inhabitants over the past twenty-five years," that is, since 1789.[5] And so on.

To be sure, earlier guidebooks did not altogether neglect the Parisians. Corrozet, we have seen, addressed his Parisian public directly, and a century later, Brice undertook to defend their character. Over the eighteenth century, newspapers and novels found Parisians an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Lesage's novel Le Diable boiteux

(The Lame Devil ) (1707) was immensely popular at the time of its publicaton (Lesage kept adding to it until 1726) and became an important model for a whole line of nineteenth-century literary guidebooks. What better figure for the guide to the inner city than his device, a not very threatening junior-grade devil whose ability to remove rooftops revealed the inside story? Montesquieu was another literary ancestor, not of course through the sober, magisterial Esprit des lois (1748) but through his satirical epistolary novel of 1721, Les Lettres persanes (The Persian Letters ) Marivaux, best known as a dramatist (witness the street named in his honor near the Théâtre de l'Odéon that created such a commotion in the 1770s), also joined this group of explorers of Parisian mores in his novels, La Vie de Marianne (1 731-42) and Le Paysan parvenu (The Parvenu Peasant ) (173435), and. in a direct steal from the journalism of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, Le Spectateur francais (1721-24) and Lettres sur les habitants de Paris (1717-18). Yet, however much these works tell us about Paris, none makes an explicit claim as a guide to the city, and none resembles what we might now call an ethnography of the city.

It fell to Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1740-1814), poet, playwright, novelist, chronicler, and all-purpose man of letters, to make, and make good on, both claims. The first, one-volume edition of the Tableau de Paris, which appeared in 1781, contains 105 short, definitely quirky sketches that explore Paris and examine the mores of Parisians. Here was the literary ancestor to whom every subsequent urban ethnographer turned; this work was the model against which subsequent works were measured.[6] Mercier does not address foreigners who seek their way around Paris so much as he tells Parisians about themselves and their neighbors, about people and places, which they may not know at all and which, in Mercier's view, they ought to know. "Many of its inhabitants are like foreigners in their own city; this book will perhaps teach them something" ("Préface"). The public obviously agreed with the author's assessment, for the popularity of the first volume was such that the indefatigable Mercier brought out a revised edition in four volumes the very next year, four more volumes in 1783, and four more in 1788.

The epigraph to the fifth volume boldly states his credo: "Variety, my subject belongs to you." There is something quite extraordinary in the assertion. Instead of claiming a hierarchical focus as an order-

ing control—king, country, or other symbols of authority—Mercier takes on the whole range of the city around him and makes himself the control. Everything is relevant within an authorial self-possession that becomes its own reason for being. The quasi-ubiquitous and extraordinarily prolific urban explorer alone is in a position to cover and to render the whole city, and through the city, the larger society. Moreover, ubiquity is suddenly a virtue instead of a problem. The controlling perspective in the Tableau de Paris is, to use a neologism of the 1780s, that of ethnology. Mercier justifies a striking comparison between life in Paris and the life of natives in Africa and America by the fact that two-hundred-league hunts and arias at the Opéra Comique are practices that are "equally simple and natural" ("Préface").

Ethnologist avant la lettre, Mercier looks down at the street dwellers as well as up at the great and shows no hesitation about venturing into the most insalubrious and potentially dangerous corners of the city. He will not, he warns the reader, disdain the lowly, the miserable, the disquieting, or the distasteful, for his research covers "all classes of citizens" ("Préface"). Introducing the article "One-eyed cabarets" (7), Mercier knows full well that his "delicate readers" will not come to such an ill-famed place. Now there is no need to do so: "I went there for you. You will see the place only in my picture, which will spare you some disagreeable sensations." And indeed Mercier writes often of places and people that few of his readers will or will have wanted to know: "Beggars" (3), "Rats" (5), "Prisons" (3, 8), "The Executioner" (3), "Cemeteries" (9), "Public latrines" (7, 11) (notably, the absence thereof), "Sewers" (7), and so on and on.

Instead of a place, Paris has been transformed into a multiform experience, one that Mercier describes in such a way that no Parisian need feel left out of that experience. By the same token, every Parisian can also feel more richly involved in a complexity that is less intimidating because it is now experienced—if only vicariously through the printed word. Behind or within each aspect of the narrative lies a larger claim of still greater importance. "This is what we now are," Mercier seems to say, inviting everyone to take both comfort and pride in the cohesion and identity that reading his experiences can bring.

In short, Mercier renders the city in terms of both the vagaries and the concrete possibilities of everyday life and through the occupations of ordinary people. He favors public space over private enclave. The places that attract him are not the palaces of royalty or the hôtels particuliers of the elite but rather the gardens and boulevards and promenades open to all, the shops of the bourgeoisie, the cafés, and the cabarets, places of natural urban promiscuity, where the urban spectacle is at its most lively. The individuals he crosses as he traverses the city from one end to the other are not, with a very few exceptions, the well known or highborn. The personages of the Tableau are the many who fill the multitude of tasks on which the city depends: the water carriers, pawn brokers, charlatans, booklenders, cooks, governesses, authors, maids, prostitutes, working girls, dentists, midwives, lackeys, authors. The Tableau emerges in the act of reading as a vast compendium of the everyday practice of the city, where the ordinary may be the extraordinary, and where, under Mercier's pen, the extraordinary becomes ordinary, the stuff of everyday life, from the "Mobility of the Government," "Visits," and "Civility" to "Moving" and "Miracles."[7]

The broad net cast by the Tableau de Paris gives the work a decidedly modern flavor. Over a half century before the "Avant-Propos" to the Comédie humaine and the extended parallels Balzac will later draw between the animal and the human kingdoms, Mercier asserts that the human being "is an animal subject to the most varied and most astonishing modifications . . . whence the infinite number of forms that transform the individual according to the place, circumstances, and time" ('Préface"). Like Balzac, Mercier takes those transformations as his subject, and, like Balzac, he also receives considerable criticism for the reach of people and behavior of which he takes serious account. The most celebrated jibe comes from Antoine de Rivarol, man of letters and author of the most famous celebration of the French language, De l'universalité de la langue française (On the Universality of the French Language ) (1784). To a writer who flatly decrees that "what is not clear is not French," the Tableau de Paris must have appeared obscure and confused. Certainly he objects strenuously to what he viewed as its irremediable vulgarity. This is, Rivarol scolds, a work "thought up in the street and written on the street sign," whose author "has depicted the cellar and the attic and bypassed the salon."[8]

Rivarol is not totally off target. The street is never far from Mercier's eye. The street sign, as we have seen, is an apt analogy, and the streets themselves of eighteenth-century Paris are, and not just by Mercier's account, dirty. There is a good deal of dirt in the Tableau, both real and metaphorical, from the chapter entitled "Manure" (2) to the startling assertion that the proud city of the Enlightenment used to be called "Lutetia, city of mud!" ("Décrotteurs," 6). Mercier's city needs its garbage men, and Mercier sees that his Tableau gets them ("Boueurs," 5). Readers accustomed to the decorous guidebooks that implicitly glorify the monarchy and explicitly praise the city must have been disconcerted, and quite possibly appalled, by the Tableau. Mercier concedes that his is a revisionist view and acknowledges that he has painted a more somber picture than readers are used to, one filled with "chagrin and anxiety" rather than the "joy and gaiety" traditionally attributed to Parisians. But he swears that his paintbrush renders faithfully what he has seen with his own eyes. Not for this ethnologist the "indeterminate and vague speculation" of experience that comes from books. He has, as he tells us, written the Tableau with his legs ("Mes Jambes," 11).

In walking the whole city, Mercier also bespeaks the implicit democracy of the coming revolution. Everything is of interest, and every layer of the city, every social group, receives its due. Privilege and poverty exist side by side. The importance accorded the lowly in this insistence upon a parallelism is almost unthinkable within the ideological (and therefore aesthetic) confines of the ancien régime. With the actual revolution, this same stress becomes part and parcel of a broader and inevitably more dynamic urban experience. One may go farther. Paris is almost incalculably more vital when everything is worthy of description. Mercier predicts, in every sense of the word, a revolutionary city of infinite possibility.

It is not simply what or whom Mercier talks about that explains the success of the Tableau de Paris among contemporaries or made it a model for literary guidebooks a half century later. The literary program that Mercier sets for himself in the 1780s echoes throughout the 1830s and 1840s. Mercier's is a new kind of Tableau de Paris, not the tableaux of Jèze, nor the many inventories or catalogues that seek to rationalize the city, but the tableau of the painter, with its varied palette and different brush strokes. No more annales, no more descriptions raisonnées or dictionnaires, no more antiquitez. Mercier marks his

dissent from the tradition of guidebooks by his determined refusal to take account of topography or history: he has produced "neither inventory nor catalogue." He will not talk, he informs his readers at the outset, about the already fixed, about the monuments and buildings that mark urban space. (Ever-obliging, however, he supplies the name and address of a bookseller where a four-volume dictionary can be purchased.) He will himself fix the transient, the ever-changing public and private behavior, the "fleeting nuances" of comportment and "public and private customs," and everything else that strikes him in "this bizarre heap of customs that may be crazy or reasonable but always changing" ("Préface"). Mercier disavows satire; he is not, he tells us, a latter-day Lesage, however easy it would be to indulge in satirical sallies.

In a credo that looks ahead to and perhaps paves the way for the nineteenth-century realist novel, Mercier certifies that he will restrict himself to what he sees. There will be none of the intellectualizing that mars the work of so many of his contemporaries. His tableau is the product of "the brush of the painter," not "the meditation of the philosophe." Unlike so many others, he does not dismiss the world around him. His own century, his own country, his own city, interest him far more than the "uncertain history" of the Phoenicians or the Egyptian. And since it is, after all, with his contemporaries that he must communicate, the Tableau by rights concentrates on them. In a proclamation that points both ahead to the journalistic principles and the realist practice of the next century and back to the pedagogical thrust of the Enlightenment, Mercier asserts and justifies his unremitting focus on the present, on the "current generation and the physiognomy of my century" ("Préface").

It is here, in his concentration on the present and the exclusion of the past, that Mercier at once continues and revises the guidebook. New editions allow guidebooks to keep pace with the shifting urban scene. But these standard guides tend to place the changing landscape of the city within a fixed history. Fixed by a monarchical past, the changing present is defined and anchored by an established, conventional past and a rationalization of the present (remember that Jèze boasts that he considers Paris systematically, "relative to the Necessary, the Useful, the Agreeable, and [in the wonderful apparent non sequitur the Administration").

Mercier's Tableau parts company from contemporary urban discourse in its elimination of the anchor that had stabilized the city text at least since Henri IV in the beginning of the seventeenth century, namely the monarchy. Thus, even before the destruction of the Bastille actually altered the cityscape, Mercier undertook to remap Paris. His reinterpretation of the city, and of the larger society, reaches well beyond the specific criticisms of the government made with considerable verve (Mercier writes from a prudent self-imposed exile in Switzerland). Like the good philosophe that he is (despite his disclaimers), Mercier stakes his claim to glory on the "few useful verities" contained in his observations, which, he fervently hopes, will lead "the zealous administrator" to correct some of the more egregious abuses he points out ("Préface").

The reconfiguration of ethnologist turns out to be far more significant than the didacticism of the philosophe. Mercier's Paris is more various and more diverse than the Paris produced by the usual guidebook exactly because it has no focal point. In the Tableau, all classes, all occupations, meet and mix. The focal point is the author himself, whose subject, as he himself tells us, is the variety that he finds. The consequent jumble of the text faithfully reproduces the disarray of the city. Both, in Mercier's aggressively egalitarian view, repudiate the hierarchy and chronology that implicitly or explicitly order the conventional guidebook.

Mercier conceives his writing of a piece with his perception of the city. His language adheres to classical norms no more than his rendition of the city follows classical conceptions of urban design. Tellingly, if the word that he needs does not exist, Mercier makes one up. Language changes like the city, and Mercier connects the two fields of action in his Néologie ou vocabulaire des mots nouveaux, à renouveler ou pris dans des acceptions nouvelles (Neologia or Vocabulary of New Words, to Be Renewed or Taken in New Senses ) published in 1801. The clutter of the Tableau reproduces the confusion of the quotidian in a large city. If the Tableau can be seen as a harbinger of the Revolution, it is because this work exposes the neat distinctions between the first, second, and third estates for the fictions that they were. High and low born mixed in the public spaces of the city frequented by Mercier, and by his readers. As Mercier's city encompasses all walks of life, so too his Tableau mixes genres, tones, and modes. At once and in turn reporter, ethnographer, philosophe, man of letters, gossip columnist,

journalist, redoubtable pedestrian, watchdog of government, and more, Mercier sets a paradigm for urban observers for a century to come.

It is scarcely surprising that a work by someone who ten years before had written a utopian treatise (L'An deux mille quatre cent quarante, 1771) should adopt a prospective rather than a retrospective view of society. Mercier is by no means unaware of history. But his is a history in the making, a history of the present for the future, and he writes about the present as a past in the making. Thus, far beyond the ken of most of his contemporaries, Mercier addresses posterity, confident that a hundred years in the future readers will return to his work to find out about his century and his city.

This confidence, perhaps Mercier's greatest asset, was not misplaced. The Tableau de Paris inaugurated a new genre and served at once as model, standard, and norm for innumerable later works about Paris. Louis-Sébastien Mercier was one of the first to write the diversity of the city. Almost alone, he created the essay-reportage, the urban genre that fascinated and inspired generations of urban explorers with its insistence upon the vitality and the meaning of turmoil and confusion. Not surprisingly, then, the "literary guidebooks" that proliferate in the early nineteenth century take the Tableau de Paris as a touchstone, as the work that they have to confront, as the model they must rewrite if they are to come anywhere near Mercier's achievement.

Mercier also sounds one more theme to which later Parisian guide-commentators will turn again and again, that of the special relationship between the writer and the city: "Paris is the country of a man of letters his only country" ("Paris, ou la Thébaide," 12). More than this, however, Mercier's practice sets the example for nineteenthcentury literary urban explorers: affirmation of the diversity of human, and particularly urban, experience and affirmation too of the equality of interest of all those experiences. Where writers in the 1830s and 1840s differ from Mercier, why Mercier himself cannot repeat the achievement of the Tableau de Paris after 1789, what makes his later writing at once more timid and more aggressive, is the colossal fact of actual revolution—1789, 1799, 1804, 1814, 1815, 1830. Mercier anticipates the event but not the many changes of regime that will soon impress upon writer and reader alike the ever-present possibility of violent social change.

III

Avec ce titre magique de Paris, un drame, une revue, un livre est toujours sûr du succès.

Théophile Gautier, Paris et les Parisiens au XIXe siècle

With this magic title of Paris, a play, a journal, a book is always sure of success.

The Revolution generated an immense amount of writing about France, and the production about Paris increased astronomically. Many contemporaries must have agreed with J. B. Pujoulx, who noted in the first chapter of Paris à la fin du XVIII siècle that no period favored the observer more than the present: "Everything is new." Paris became the indisputable center of French political, economic, and intellectual life. Its population augmented at a faster pace than ever before, doubling between 1801, when the first official census was taken, and 1850 (and this despite a serious cholera epidemic). Political volatility exacerbated the sense of urban instability. In a space of less than seventy years, France moved through an impressive number of political regimes. Two monarchies, two empires, and three republics were ushered in variously by two revolutions (1830 and 1848), two military defeats (1815 and 1870-1), one coup d'état (1851), and one civil war (1871). But, as for the Revolution of 1789, the city of Paris was the theater of all but one of these events (the Prussian army laid siege to but did not actually occupy the city in 1870-1).

The great number of guidebooks to Paris that appeared in the new century testifies to the need for guidance, not simply because of the altered topography but also, and more urgently, because of the radically altered character or, to use the term favored by contemporaries, the "physiognomy" of a city that had been shaken to its foundations by revolution. The extraordinary popularity of the Hermit series inaugurated by Étienne de Jouy, beginning in 1811, reveals a dramatic combination of anxiety and curiosity about the city that was changing before the very eyes of the writer and the reader.[9] Jouy's hermits gave the guidebook, or what I shall call the "literary guidebook," a formula that seems to bring Mercier up to date (the later Hermite de la Guiane acknowledges his connection to Mercier). But the filiation is trickier than this explicit reference allows. The Tableau de Paris remains unique because Mercier's city has a decided and marked unity, a coherent physiognomy.

Such cohesion is exactly what the quarter century between Mercier and Jouy has shattered. The volatility of politics has rendered the task of the would-be observer of customs uncommonly difficult. "The French nation no longer has a physiognomy," complains another one of Jouy's personages, Guillaume le Franc-Parleur (William the Frank Speaker), writing a month after the final defeat of Napoléon at Waterloo and the reestablishment of the Bourbon monarchy. "The convulsions of suffering have altered its traits so profoundly and so completely denatured its character, that it has become entirely unrecognizable." Returning to Paris after an absence of twenty-five years and despite having lived in the city for thirty years before that, a friend reports to Guillaume with considerable distress that "Men and things, everything is changed, displaced, confused: I look and recognize nothing; I speak, and people barely hear me."

The chronicler-protagonists of the Hermit series exhibit none of Mercier's enthusiasms, few of his quirks, and little of his ambition. The politically circumspect Jouy moves with the times and the regimes. Royalist fervor wins out when "the august family of the Bourbons is given back to us." Jouy kills off his Bonapartist original Hermit de la Chaussée d'Antin just as Louis XVIII enters Paris as king. Guillaume le Franc-Parleur, the new Hermit, is younger, a politically correct monarchist who, "like all France," had been the "dupe" of Bonaparte's promises. The trenchant criticism and the overreaching ambition to comprehend the course of the city in history had to wait for the great novelists of the July Monarchy, for Balzac and Stendhal and Hugo. Jouy's Hermits have a far less intense relationship to the city than either Mercier before him or Balzac and Hugo after. Like Mercier, the Hermit "paints" customs. But he seeks to depict society as such and not a given society, and his concern is with "classes, species and never individuals."

In all his various incarnations, the Hermit is a genial character whose regular sorties into the city take him into unaccustomed places and bring him into contact with a broad range of people but, as the name implies, without ever involving him deeply. The affable tone of the essays and the title warn the reader that this observer sets himself apart from the city. Very much unlike Mercier, who is passionately involved in every event, every individual, every city space, the Hermit remains aloof from the scenes that he himself observes. It is this distance from his material that enables the Hermit to travel through the

provinces as easily as Paris. For, whether at home or abroad, the Hermit is essentially a traveler (he proudly tells of his trip around the world with Bougainville). He most definitely is not, as Mercier so proudly is, a man of letters. And he is certainly not, again as Mercier so assertively is, much interested in reform.

Jouy's extraordinary success pointed to a pervasive bewilderment over the state of urban society, a state of affairs that other writers by the score also sought to address. If, as Victor Hugo insisted in the 1820s, a postrevolutionary society compelled a postrevolutionary aesthetic, a postrevolutionary urbanizing Paris dictated an urban aesthetic. Just how that aesthetic might be revolutionary was a subject of great debate as writers sorted out genres and styles, publics, publishers, and politics. But that it must be revolutionary in some fashion admitted of no doubt. Histories, guidebooks, essays, novels, and poetry about Paris glutted the market, which then asked for more. Every person able to pick up a pen seemed to rush to take up Pujoulx's implicit invitation when he declared at the beginning of the century that however much had been written about Paris, no time was as interesting as the present. The result, predictable enough, was a surfeit of publications on and about Paris. In 1856, by way of justifying yet another anthology of Paris explorations, Théophile Gautier took stock of a situation that was surely not new: "With the magic title of Paris, a play, a journal, a book is always sure of success. Paris has an inexhaustible curiosity about itself that nothing has been able to satisfy, not the fat serious books, nor the thin publications, not history,. . . not memoirs, not the novel."[10]

Guidebooks proper, with maps and details on the location of streets and sights, generally confined themselves to tracking topography and institutions. As Paris expanded and built (Napoléon I started significant building projects virtually as the century began), guidebooks proliferated. Typical of what we now immediately recognize as an example of this most conventional of genres was Le Nouveau Conducteur parisien ou plan de Paris (1817) with maps, listings of hotels, means of transportation, sometimes statistics of one kind or another, and useful information ranging from hours and locations of restaurants, museums, and libraries; numbers of houses, streets, and inhabitants; locations of translators; the street numbering system; and so on. Le Nouveau Conducteur, like most of its predecessors in the ancien régime and indeed most of its successors, addressed largely foreign-

ers, referring those in need of more information to the sixth edition of Le Conducteur de l'étranger à Paris.

Little cultural information is included beyond reassurances to the apprehensive visitor that drinking the water from the Seine "does not indispose Parisians with its slight laxative quality" and, moreover, has no ill effects on foreigners so long as they drink it mixed with wine or a drop of vinegar. (Mercier had already pointed to the "purgative" powers of the Seine [1, 4].) The title points to the difference. For this guidebook is, as announced, a conductor, not a guide. A conductor gives precise directions to a specific, known, charted terrain (note that the subtitle of Le Nouveau Conducteur can be translated "map" or "outline"). A guide imparts as well a larger sense of direction. The conductor may be far in the lead; the guide, closer by, imparts wisdom as well as direction through unknown and uncharted terrain. The archetypical image is, of course, Virgil's guidance of Dante through the Inferno (Dante addresses Virgil in canto 2, line 10, "Poeta che mi guidi . . ."). Le Nouveau Conducteur has no author. There is no guide. The modern guidebook makes no moral claims, confines the advice it offers to practical, readily verifiable information, and assumes no responsibility for conduct beyond its confines. We are at the antipode of Mercier's idiosyncratic, opinionated reports about the city and equally as far from his ambition to render the "physiognomy of [his] century." Perhaps these new writers of guidebooks agreed with Jouy that France in the early nineteenth century no longer had a physiognomy.

Without an author, these guidebooks essentially renounce any claim truly to guide the individual in Paris. Modern equivalents of Jèze's tableaux, these works content themselves with the obvious, with surface detail, which, although abundant, says nothing about the nature of the urban experience and nothing about revolutionary Paris. We are miles from the excitement and the wonder that pervade Mercier's Tableau, and still further from the intense explorations of the city by Balzac and Hugo. All of these authors, in however different a mode, stamped the city with their strong personalities.

The link between Mercier and Balzac or Hugo, then, comes not through conventional guidebooks, but by way of what are more aptly called "literary guidebooks." These works are not really guidebooks, since, unlike either Le Nouveau Conducteur or Jouy's Hermit series, they offer significant directions to the new society emerging in Paris

after the Revolution, and especially after the July Revolution of 1830. Topography is the least of the matters taken up in these works, from the fifteen-volume Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un (1831-34) to the work that caps and exhausts the genre, Paris-Guide, published for the World's Fair of 1867. For Parisians as interested as they were anxious about the world changing before their very eyes, these works offered both information and assurance. Where Mercier gave an état présent, nineteenth-century commentators reveled in change, in the new characters, personalities, customs, and behavior that characterized contemporary urban life.

At the same time, no single authorial voice grounds the interpretation of the city text. These were aggressively collective endeavors, multivolume collections of vignettes on people, places, events, and institutions. The anthologies capitalized on the expansion of the reading public, which also made the serial novel so successful a formula at about the same time, beginning in the 1830s. Publishers raced to get out the next compilation, and writers from all corners of the literary world joined in, from Chateaubriand and Charles Nodier among the older generation to Lamartine, Balzac, Gérard de Nerval, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and a host of others. Foreigners too, Goethe and Fenimore Cooper most prominent among them, were pressed into service. Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un saved the publisher from bankruptcy, and each volume of Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes carried a front page to all the contributors from the "Grateful Publisher." By the 1840s these literary guidebooks carried lavish illustrations by Gavarni, Henry Monnier, and Daumier, to mention only the best known.

The pieces themselves run the gamut from the sketches of urban character types known as physiologies (Balzac's "Histoire et physiologie des boulevards de Paris" in Le Diable à Paris or the "Physiologie du flâneur," to which I return in chapter 3), to serious, and generally unimaginative, delineations of sometimes picturesque institutions (the morgue, the insane asylum at Charenton, public libraries) to incidents (the cholera epidemic, the funeral of the scientist Cuvier).[11] Like the city that they strove to represent, these collections offer something from and for almost everyone.

The nominal model of the new urban journalism is Lesage's satirical novel, Le Diable boiteux (1707 and 1726), which recounts the adventures of Asmodée, a minor devil of lust and lechery, as he removes

the rooftops of houses in Madrid (read Paris) to flaunt his control over human lives. Immensely popular from its publication, Le Diable boiteux offered a convenient tag for the literary guidebooks and, perhaps, in the figure of the devil, an emblem of authorial perspective. Asmodée is uninvolved; he comes from another world. When Jules Janin signs "Asmodée" to his introductory article to Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un (1831), he signals his connection to a genre that looks at the city from afar, and when Gavarni places a devil standing over the map of Paris on the title page of Le Diable à Paris, he too suggests distance as the operative mode of urban interpretation in the texts that follow (though it must be admitted that the devil in question bears no resemblance to the description that Lesage gives of his Asmodée)

Yet, if Lesage supplied the emblematic figure for these collections, it was Mercier who furnished the literary model. Fifty years after the publication of the Tableau de Paris, the publisher, Ladvocat, placed Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un under Mercier's aegis: "We must do for the Paris of today what Mercier did for the Paris of his time." But politics has intervened in that half century, and Mercier's brush will no longer do. "Another pen besides Mercier's is needed." It is not simply a question of finding a contemporary Mercier. No single pen can comprehend the postrevolutionary city. Indeed, how could any individual render the multiplicity of "tricolor Paris?" Is not this urban multiplicity inscribed on the flag itself? Does not the very flag of France join the white of the monarchy to the red and the blue of the city of Paris? Who can possibly render the "drama of a hundred different acts" of this revolutionized city? What guide could possibly lead us through the "long gallery of modern customs, brought into being by two revolutions?" The publisher's solution—the solution of this particular genre on the edge of literary respectability—counters diversity of subject with diversity of execution, which is why the literary guidebook stands as the paradigmatic genre of urban exploration.[12]

Jules Janin begins his introductory article, "Asmodée," by insisting on the association between new times and new modes of presenting them. Since everyone has taken to observing contemporary society, nineteenth-century Paris wants not one but many observers to reveal it all: "It is through this revolution in the study of customs that the new lame Devil will get something out of us. . . . It is through the

collaboration of everyone that he will write once again the story of our failings."[13]

Yet collaboration placed definite limits on urban discourse. Although Mercier clearly gloried in the exuberant diversity he found on all sides, he remained confident of his ability to contain the proliferation of the city. His nineteenth-century epigones—overwhelmed by diversity, by sheer numbers, by strange sectors of society and their stranger inhabitants—could not sustain his sense of certainty. Insofar as the fragmentation of the city precludes encompassing the whole, these works could only enumerate their findings. No single point of view prevails. The classical unities, and the more modern ones as well, no longer obtain. The social and political revolution calls for the collaborative interpretation: "Unable to get a comedy out of one man, we have set out more than a hundred strong to make a single comedy; a hundred of us or two: what's the difference? As far as unity is concerned, it comes down to the same thing." Less unified perhaps, the resulting production is more interesting.

To judge by the number of works that appeared in this format, including reprints of previously published articles, multiple authorship made good commercial sense, and it made good sociological and aesthetic sense. Jules Janin obviously thought so, for ten years after Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un, he undertook the introduction to undoubtedly the most ambitious of these works, Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes (five of the nine volumes concern Paris), which appeared between 1840 and 1842 and was billed as an encyclopédie morale du dixneuvième siècle. Not only the rapidity of change but also and especially the fragmentation of Parisian society, Janin asserted, force a new approach to the city. In one hundred years (the same period Mercier allotted for his own work), "people will recount that this city, so proud of its unity, was divided into five or six sections ('faubourgs'), which were like so many separate universes, separated from one another far more effectively than if each were surrounded by the Great Wall of China."[14] Things do not seem to have changed much on this score since Jouy affirmed that in no city except Peking and Lahore do the classes and neighborhoods live so separately (L'Hermite de la Chaussée d'Antin, 12 June 1813).

Janin also echoes Jouy (and other conservative writers, such as Balzac) in pointing to contemporary politics, and specifically the Revolution, as the source of division. "This great kingdom has been cut

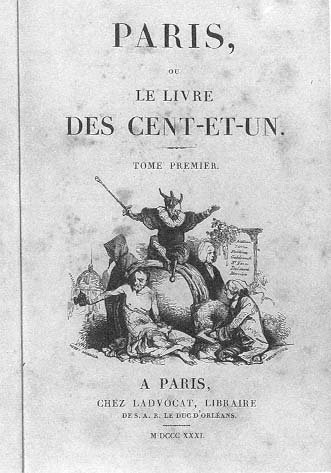

Plate 5.

Title page by Henry Monnier, Paris, ou le livre des

cent-et-un (1831). Among the ancestors invoked for this

miscellany of sketches on the city that opened with

the July Monarchy, English writers predominate on the

tablet in the background (Addison, Sterne, Fielding,

Goldsmith); St Foix and Dulaure are historians of Paris;

and the incomparable Mercier is the author of the Tableau

de Paris. The peg-leg devil, who overlooks the scene in the

foreground, is taken from Lesage's novel of 1709,

Le Diable boiteux. He will acquire more contemporary

demeanor and dress in later collections. (Photograph by the

University of Chicago Medical Center, A.V. Department.)

Plate 6.

Title page, Le Diable à Paris (1855). The devil, in

somewhat more modern dress and no longer lame,

straddles a map of Paris, lamp in hand to light his

way. His basket literally overflows with the articles

of the writers contributing to the collection listed

under the title. (Photograph by University of

Chicago Medical Center, A.V. Department.)

into as many little republics." A single writer could grasp the unitary nature of the king's domain; many chroniclers are needed to comprehend the warring, squabbling republics of a postrevolutionary age. Just open any chapter of Les Caractères, Janin urges, and you will be convinced that representation of France in the July Monarchy must be divided among many authors. Contemporary society boasts, or despairs, of innumerable phenomena that La Bruyère never imagined. Today, in postrevolutionary society, there are multiple cities within the city, and they are all changing all the time. A portrait has to be drawn every hour because yesterday's is already out of date.

Yet the most fundamental questions remain. What and where is Paris? How is the city to be imagined, defined? How in fact are we to read these texts, and the city beyond? I would suggest that tables of contents (tables des matières ) provide just the unity that the city text requires, a unity that encounters diversity in much the same way that a map imposes an artificial, constructed unitary view on three-dimensional space. The order of the text is logical in the primary, etymological senses of theory (logia ) and discourse (logos ) More accurately, this order is physiological because each table of contents is itself taken as an overgrown physiologie. That is, each table of contents offers a particular entry into urban life, a singular, necessarily reductive angle of vision on the vast complex of the city. Like the physiologies that reduced individuals to types, these multiauthored collections reduced urban society to a string of character types.

The very vogue of these works testifies to the failure of the definitions they propose, the failure, in sum, of what may be termed an "aesthetic of iteration." In these texts the divers parts of the city fail to cohere.[15] Jouy made this aesthetic his guide: "The best, or rather the only means of knowing [Paris] well is to examine each part in isolation" (L 'Hermite de la Chaussée d'Antin, 12 June 1813). But at least Jouy could claim that his pages would make the connections. The chorus of voices of multiple authors fails to provide that minimal focus. The aesthetic of iteration founders on the descriptive because there is no authority to turn the list of description into the order of narrative. There is no guide, no authority, to interpret the city.

Absent that guiding authority, the order of these works becomes sociological, the order / disorder of society complacently, uncritically duplicated in an urban text designed to reassure. The multiple authorship vaunted by Janin and so strongly supported by publishers

and readers alike reproduces, as indeed it is meant to, the diversity and the disorientation of urban life. The city is laid out before the reader like the merchandise displayed in the arcades that Walter Benjamin takes as another emblem of modernity and of Paris. By design the display of the guidebook diffuses attention onto as many points as possible, to entice the potential consumer or spectator to sample at random and at will. The power is in the hands of the consumer, not the author.

I suggest that synecdoche is the basic trope of these jumbled urban texts. The table of contents, with the chapter titles listed one after another, is to these works as the view from Notre-Dame is to the city itself, a simplification, perhaps a distortion, but one that is necessary in order to conceive the city as a whole. The table contains the entire book and itself offers an interpretation of that book, and of the city. (This interpretation may be confirmed by the actual articles or modified or, for that matter, contradicted altogether.) The table of contents constitutes an urban planning of a sort, a utopia, though of real enough places and institutions, in any case a fiction. The table of contents negotiates the text and, by extension, the city. The strange becomes familiar, the familiar becomes amusing. These texts depend upon one reading of the city—that contained in the table of contents—and produce another as the individual devises an interpretation within textual constraints.

IV

Il n'y a plus au monde que le Czar qui réalise l'idée de roi, dont un regard donne ou la vie ou la mort, dont la parole ait le don de la création.

Balzac, "Ce qui disparaît de Paris"

There is no longer anyone except the Czar who embodies the idea of king, whose gaze gives life or death, whose word has the gift of creation.

Whether expressly instrumental like Le Nouveau Conducteur or more narrative like Le Diable à Paris, the guidebook could not cope with the city of revolution. Understanding that city required more than lists or descriptions. In place of enumeration nineteenth-century Paris craved interpretation. Collections of miscellaneous texts failed to satisfy that need. Because they diverted attention from the essen-

tial, they could never provide the focus necessary to a coherent urban discourse. Individual writers, however, might and did assume that authority. The great novels of Paris that drew their strength from this arrogation of authority became the privileged vehicle of urban interpretation. Novelists defined the role of guide in the strongest, virgilian sense of the term, as they took their readers into the inferno of the city and led them out again, sociological tour and moral lesson completed.

Clearly, the model for the narrator in these works was no lesser devil, but the highest authority. Rewriting revolution demands a special kind of imagination, one that sees beyond the parts to the whole. The great novels of the nineteenth century do just this, and their richness depends, in good part, on their assumption—quite the contrary of Janin's—that the city exists intact and that, however much attention must be paid to the parts, Paris is more than their sum. For the aesthetic of iteration characteristic of the literary guidebooks the novel substitutes an "aesthetic of integration." The novelist claims to produce in narrative the whole fragmented by the Revolution, reaching to a larger authorial vision.

Balzac, in his piece "Ce qui disparaît de Paris" ("What's Disappearing from Paris") for Le Diable à Paris in 1844, explicitly connects the transformations in the city, in particular its losses, to the dereliction of royal authority. The definition of city space once imposed by the monarch no longer obtains. Latter-day kings no longer possess the powers of invention. In the Europe that appeared after 1789, only the czar fully realizes the idea of kingship, which Balzac locates in a gaze capable of giving life or taking it away or in a word endowed with the gift of creation. Obviously, Balzac has a replacement in mind, himself, the writer, the one individual endowed with the power to resurrect old Paris.

The conjunction of literature and the city is already a commonplace by the nineteenth century. Indeed, urban discourse of every sort threatens to overwhelm the city itself. In one hundred years, Jules Janin fears, "people will say that in this capital all time was spent talking, writing, listening, reading" ("Introduction," Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes ) Into an urban space flooded with discourse of every sort the novel brings a reimagined city. In place of the fragments of a city the novel affirms its intention to make the city whole. This paradigmatic urban genre simultaneously expands the narrative to

contain the city and constricts the city to fit the narrative. The simplification involved in these rhetorical strategies of containment is a necessary feature of the governance and use of symbols. Without such stylization, the city muddles the reader looking to decipher the urban text in much the same way as it disorients the individual inhabitant or traveler endeavoring to negotiate the city.

The metaphorization of Paris does not begin in the nineteenth century, but metaphors and images of the period take on a decided intensity.[16] The characteristic and appropriate trope for the city is metonymy. For metonymic figures, in particular synecdoche, construe the familiar sights of the cityscape that topographically and symbolically tie its many parts: the Seine, the sewers, the catacombs, the cemetery, and in the long term, the métro are, like the printed page, networks that bring the scattered fragments into a whole. All of these figures reduce the city to a part, but a part that in turn contains the city. The reciprocity of synecdoche is vital to the way these metonymic figures define the city in its entirety.

One of the most frequent strategies of writers and tourists alike is to view the city from afar, most strikingly from a height. Early maps tend to place the observer somewhere on the horizon, at a point of view that no one at that time could possibly have. Mercier was not the first to climb the towers of Notre-Dame to observe the city from above, nor was he the last.[17] In the nineteenth century an adventurous soul might take a balloon ride. Or read novels. The view of the city from afar becomes a staple among topoi in the nineteenth century, an urban variant of the more general romantic taste for panoramas. The most famous of these is assuredly the "chronicle inscribed in stone" that Victor Hugo details for medieval Paris in "A Bird's-Eye View of Paris" ("Paris à vol d'oiseau") in Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) (bk. 3, chap. 2), which he counters thirty years later in Les Misérables (1862) by "the deadly harmonies" of the 1832 Paris insurrection in "An Owl's-Eye View of Paris" ("Paris à vol de hibou") (pt. 4, bk. 13, chap. 2). The mirror image of the aerial panorama is the labyrinth in Hugo's celebrated presentation of the sewers in Les Misérables, the one and the other not the "real" city but a projection of that city.

Of Balzac's Parisian panoramas, the most striking views, the most pregnant with meaning, are those from the cemetery of PèreLachaise, which is both in and above the city.[18] These scenes—Jules Desmarets' meditations at the burial of his wife in Ferragus and Eu-

gène de Rastignac's defiant challenge at the very end of Le Père Goriot —elaborate the topographical contrast between the subterranean and the aerial city into an analogy between the city of the living and the city of the dead (complicated by the location of the cemetery above the city). The cemetery is a site de passage and a rite du récit, a rite and a place of passage, a modern example of the medieval dance of death designed to impress the living with the vanity of life. At PèreLachaise the grieving Jules Desmarets for the first time comprehends the Paris that he sees at a great distance. The cemetery becomes a city unto itself, a microscopic Paris that presents a synedoche for the "true" Paris. The topos of the cemetery constitutes a chronotope, which reinvests the landscape with authorial definition, and the bird's-eye view of the writer substitutes for the superior vantage point that was once the king's. And of course, as Balzac makes clear by equating the king's gaze with life and death, the writer aims higher, beyond the king to the deity from whom royal, and narrative, authority derive.

This "urban imagination" is then very much a "synecdochal imagination," defined by the ability simultaneously to conceive the part and the whole. This imaginative power is vital to the urban novel because it alone allows the city to be apprehended beyond the fragmentation implied in the parts that multiply as writers explore the city further. Synecdoche thus bespeaks the aesthetic of integration. Physiologies and literary guidebooks disperse energy by dividing Paris into parts. The urban textual equivalent of "divide and conquer" is the "segregate and dismiss" implied by the physiologies. Those caricatured are safely Other, they live safely Elsewhere. The urban imagination, however, insists upon the inescapable connections between those parts, not excluding the most extreme. Père-Lachaise is part of the city, so are the sewers; the infamous rue Soly, where the ex-convict Ferragus lives, is contiguous with the rue Menars, which is the home of his eminently respectable and elegant daughter; and the Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève of the scruffy Pension Vauquer is inscribed within the faubourg Saint-Germain of Mme de Beauséant's elegant hôtel and vice versa. Balzac never allows the reader to forget or dismiss these connections. Each is a necessary function of the other. Each depends upon the other. The myth of Paris, which crystallizes in the revolutionary energies released by the July Revolution,

is in turn a function of the emphasis upon these almost organic attachments.

The personification of Paris, indeed the multiplication of grandiose metaphors of every sort, further attests to this organic conception of the city. Integration overcomes iteration to create the unity that cannot be reproduced because it does not exist. The panorama offers one means of creating unity, global metaphors another. In either case this creation is the vocation of the writer, and the city thus created stands as another in a long line of utopics that allow us to identify with the city, to know it, or to feel that we do. The utopic offers the reader a text, and a tactic, for dealing with the city.

This utopic, properly speaking, is revolutionary. The assimilation of the Revolution into literary France is the task, and the glory, of the writer and the condition of literature. The writer's creation of figurative unity replaces the monarchy but does so only in full acceptance of the consequences of that which destroyed the monarch. The novel makes its distinctive contribution by restoring the human scale of the city through exemplary (not typical) figures, which give the city expression and definition. Rastignac, Quasimodo, Gavroche, Frédéric, Gervaise, Nana . . . are not simply protagonists in novels. They are also actors in a profoundly literary because profoundly revolutionary Paris.

V

Paris est le point vélique de la civilisation.

Victor Hugo, Paris-Guide

Paris is the focal point of civilization.

The guidebook, ordinarily, makes few claims to greatness. Its great strength, but also its great limitation, is topicality. If customs change almost weekly, as these works often claim, then they are outdated as soon as they are published. The only answer possible is to put together another guidebook (which, indeed, seems to have been the strategy of choice in the 1830s and 1840s). The novel, on the other hand, proclaims its ambition to understand not the day or the week or the year but the century. The two modes of urban exploration would seem to be irreconcilable. Balzac's incorporation of his occasional pieces into his novels does not fundamentally alter either genre. But

when Victor Hugo takes on the introduction of a great collective guide to Paris, the genre virtually splits in two, utterly transformed by virtue of Hugo's reconceptualization of urban discourse.

The fusion of the writer and Paris, Paris and modernity, modernity and revolution, is nowhere more arresting than in the work and the persona of Victor Hugo. And nowhere is Hugo more insistent on making those affinities explicit than in his outsize introduction to Paris-Guide (1867 ) Given his tenacious, vocal, and highly publicized opposition to the Second Empire, Hugo represented a somewhat audacious choice to present a work timed to appear for the World's Fair sponsor d by the government. But any work whose title page boasted authorship par les principaux écrivains et artistes de la France simply had to include Hugo, so great was his reputation in France and abroad and so strong were his associations with Paris.[19]

The book, like Paris itself, is suffused with light. The title page carries a small seal with a large sun rising over Lutetia (though the buildings mark it as medieval Paris), and Hugo stresses that Paris-Guide is an edifice constructed by "a dazzling legion of minds." Further, if all the missing "luminaries" were added, the book "would be Paris itself."[20] Thus Hugo both affirms the writer's right to define the city and attests to the fact of that definition.

Yet, though Hugo speaks for authorial privilege generally, the claims that he makes on and for "Paris itself" are, finally, personal claims. For over thirty years Paris has been Hugo's city, his creation, from Notre-Dame de Paris to Les Misérables. His identification is total. Paris itself is text and intertext. Old Paris shows up distinctly under the Paris of today "as the old text shows up in between the spaces of the new" (x). So complete is Hugo's assimilation of the city that he conflates his exile with his marginal authorial status: "We are properly on the threshold, almost outside. Absent from the city, absent from the book" (xxxiv).

Hugo's colossal introduction essentially turns Paris-Guide into an oxymoron. However brilliant the contributions of the other "luminaries," they supply mere fragments; Hugo provides the only source of light for the City of Lights. He is then in person the guiding light of this work, the sole source of unity. Thus Paris-Guide explodes the genre of the literary guidebook. There will be other guides to Paris, of course, and no end of works on one or another aspect of Paris. But

Plate 7.

Frontispiece and title page, Paris-Guide (1867). The small seal at right

shows the sun rising over Lutetia. The seal of the modern city to the

left literalizes Hugo's conception of postrevolutionary Paris in a century of

progress. In contrast to the official seal, which displays a three-masted ship

viewed from the side, this seal exhibits a galley with a single square sail

going before the wind with its bank of oars raised. The great billowing sail

heading directly toward the reader pictures Hugo's impassioned affirmation in

the introduction to this work that "Paris is the center of effort on the sail

that represents civilization." Like the winds that converge on a single point of

the sail, the currents of modern civilization intersect in Paris. With the crossed

olive and oak branches that recall the garlands of the seal of the First Empire,

the editors discreetly placed the volume under Napoleonic protection—but that

of the first Napoléon not the third. Hugo should have been pleased at the

iconographic gymnastics that placed him in the company of the right Napoléon.

(Photograph by University of Chicago Medical Center, A.V. Department.)

no other writer lays claim to a vision of Paris anywhere nearly as comprehensive as Hugo's.