2. Greek Education

The author was accordingly a native of the Jewish Egyptian Diaspora. In view of his origin, his knowledge of Greek, the use of the name of a celebrated Hellenistic ethnographer as his pseudonym, and what appear to be Hellenistic features in the fragments, it has been assumed that he was a "Hellenistic Jew,"[33] and the book has been classified in the category of Jewish Hellenistic literature. Our examination of this assumption will at first avoid the question what Hellenistic Judaism actually was. It should be noted only that the Jewish community in Hellenistic Egypt was not homogeneous, and its major streams advocated diverse and often conflicting approaches to the relationship between Judaism and Hellenism. The traditional image of a Hellenistic Jew has, however, been shaped according to the surviving literary contributions of Alexandrian Jewry, especially the works of Philo. Therefore, the question that will occupy us at this juncture is whether Pseudo-Hecataeus was a Hellenistic Jew similar to the enlightened Hellenistic Jews Aristobulus, Pseudo-Aristeas, and Philo, who utilized their profound mastery of the Greek heritage, each in his own way, to reconcile the two cultures and explain the Jewish Holy Scriptures according to the methods, ideas, and achievements of "Greek wisdom." To answer this, it must be established whether the author's Greek education and knowledge of the Greek literary corpus (especially the philosophical one) was profound and on a level with that of the above-mentioned Jewish authors, and whether Pseudo-Hecataeus indeed tried to apply Greek thinking and traditions to an understanding of Judaism.

The evidence available for answering these two questions is closely related. From the contents of the fragments and testimonia it appears that the author did not have any philosophical education and that his acquaintance with the Greek heritage and Hellenistic life was limited to popular ideas and practices, and that even this knowledge was rather superficial. In addition, there are no associations, parallels, or references to the great corpus of Greek literature, which were so common in contemporary prose writing. What the author knew of Hellenistic culture and civilization was, by and large, no more than could be expected of

[33] This is implied or stated explicitly by Freudenthal (1875) 165-66; Graetz (1888) III.2.608-9; Willrich (1895) 32, (1900) 105, 115-16, 127; Hengel (1971) 303; Walter (1976) 148; and others.

an intelligent oriental, living in Hellenistic Egypt or residing in the greatest and most civilized city of the Hellenistic world, who had not completed a comprehensive program of Greek education.[34] A grammatical and stylistic analysis of the text corroborates this impression. The author's acquaintance with Greek literature thus fell considerably short of the standard set by the Hellenistic Jewish authors mentioned above. In addition he made no attempt to apply "Greek wisdom" to the interpretation of Jewish beliefs and religious practices.

One is especially struck by the total absence of any philosophical terminology or argument and the ignorance of the Greek philosophical heritage. It would suffice, for instance, to select at random a few passages from Jason of Cyrene, the Wisdom of Solomon, or Pseudo-Aristeas (not to mention Philo and IV Maccabees) to see the difference. Given the wide range of topics mentioned in the surviving material, the fact that only a small part of the original work has come down to us is no excuse. The passages about the Jews' strong adherence to their religion, martyrdom, the destruction of pagan altars and temples, and even the allusions to Jewish overpopulation invite some philosophical interpretation, justification, or parallels. They are lacking here, although their inclusion was a common practice for most Jewish Hellenistic authors. The author, who paraded himself as Hecataeus and must have known that Hecataeus was a philosopher, does not even try to imitate Hecataeus's Jewish excursus, which is full of philosophical and social reasonings. It is true that these passages may be abbreviated, but Josephus had no reason to be so consistent in omitting "philosophical" explanations. On the contrary, he was keen on offering reasons for Torah precepts. In the preface to the laws of Deuteronomy he states that he plans to write a book on Jewish practices and their reasons (Ant. IV.198), and his version in the Jewish Antiquities provides explanations for many laws.

No less instructive is the absence of any philosophical-moral explanation in the references to the construction of the Jewish altar solely of unhewn stones (Ap. I.188). The Torah itself indicates the existence of such a reason: "If you make an altar of stones for me, you must not build it of hewn stones, for if you lift up your sword on

[34] On the question whether there was a Hellenistic enkyklios paideia and on its regular disciplines, see Marrou (1937) 211-35, (1956) 223ff.; Koller (1955); de Rijk (1965); Mendelson (1982) 1-47.

it, you will profane it" (Exod. 20.25, Deut. 27.5-6). Philo provided two symbolic explanations (Spec. Leg. I.275, 287), and later Judaism interpreted it in various moralistic ways (e.g., Middot 3.4, Mechilta ad loc. ). Pseudo-Hecataeus's description of the Temple is detailed and given in direct speech, and Josephus, who was evidently puzzled about this instruction of the Torah,[35] would not have missed the opportunity to give an explanation had he found one in the original text. Josephus himself gives allegorical explanations in Book III of the Antiquities for various aspects of the Temple and of the priestly service.

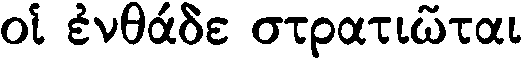

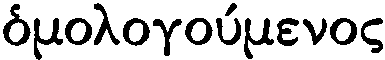

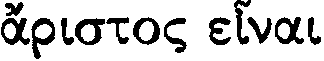

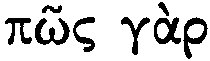

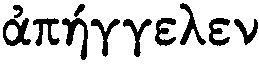

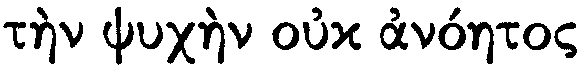

The absence of Greek philosophical terms in the characterization of Jewish personalities is also noteworthy. Hezekiah the High Priest is described as "not unintelligent" (

[36] For the correct reading and translation, see p. 51 n. g above.

Hellenistic literature, including that of biblical heroes.[38] This applies also to Moses and the High Priest in Hecataeus's Jewish excursus (Diod. XL.3.3, 5). Eulogies (enkomia ), which were among the first school exercises of the rhetorical curriculum and played an essential role in public competitions and funerals, included the virtues as a regular component.[39] The personality of Hezekiah seems to reflect the obvious qualities of a good politician or leader in a Hellenistic city and oriental community alike, or of a secular leader in the Jewish Diaspora, rather than to have been inspired by a Greek literary model or reference.[40]

A direct proof of the author's incomplete and superficial acquaintance with Greek conceptions and practices is provided by the Mosollamus story. The analysis of the episode in Chapter III.1 showed that Pseudo-Hecataeus misrepresented the belief in bird omens, as well as the rules of interpretation, and that he failed to mention either the common term for a bird of omen or the particular species. One may of course argue that he disregarded the Greek features in order to simplify the story for his less knowledgeable Jewish readers and thus make the joke more effective. This explanation may be valid as far as the theological conception is concerned, but not with regard to the practical details. The arguments already raised above in the discussion of the authenticity of the book[41]

[38] See, e.g., Plato, Leges 965; Politeia 427eff., 439dff., 480ff.; Plt. 311; Xen. Ages. III.5, IV.1, V.5, VI.1, 4, VIII.1, 4, and esp. XI; Anab. I.9; Cyr. I.3.10-11, 16-18, 4.18-24, 5.6-7, 6.1-6, and many parallels in the other books of that work; Pseudo-Aristeas 122, 212-27; Jos. Ant. I.256, IV.327-31, VII.390-91. Many parallels can be found in references by Philo to biblical figures. Cf. also the rector in Cic. Rep. V and VI.

[39] See Marrou (1956) 272-73.

[40] Literary influence of Il. IX.443 (cf. Cic. De Or. III.15.57) on the characterization of Hezekiah is rather a remote possibility, especially in view of the absence of further associations with the epic tradition and the many other references to the ideal leader Moreover, the terminology is quite different, and the distinction between doers and talkers is a common topos in Greek literature. Josephus's description of Joshua's personality may suggest the existence of a topos that also included the three qualities of Hezekiah. He attributes to Joshua wisdom, eloquence, piety, courage, endurance, dexterity in directing affairs, and adaptability to every situation (Ant. III.49, V.118; cf. Feldman [1989]). However, the other qualities are still missing in the characterization of Hezekiah, and the absence of piety shows even more forcibly that the author had in mind a practical, not a literary, model.

[41] See pp. 68-69, 70 above.

are also applicable here: referring to one or two of the real rules for interpreting omens would have contributed greatly to ridiculing gentile divination. And why would a knowledgeable Hellenistic Jew refrain from specifying the bird in question, or from using the word oionos , the technical term for a bird of omen, and instead repeat four times the general term ornis ("bird")? The Homeric epics stood at the forefront of Hellenistic education in Egypt in all its stages, including the first writing exercises.[42] An author who received a systematic Greek education would easily have been inspired by certain Homeric verses to fill these gaps in his story, even if he was not personally acquainted with the practical side of Greek mantics. Whatever the reason for the absence of a real challenge to the theology underlying Greek omens,[43] the author certainly differed from Pseudo-Aristeas, his older contemporary, who took great pains to undermine the theological foundations of gentile practices mentioned in his book.

Hans Lewy, in his endeavors to prove the authenticity of the treatise, pointed to a number of references that in his view proved that the author was well acquainted with Greek classical and contemporary literature and trends.[44] This has generally been accepted, even by scholars who deny authenticity, and has led them to describe the author as a Hellenistic Jew. It has been shown above that Lewy was mistaken in describing the characterization of the Jewish individuals in the book as typically Greek. Of the other features that have been taken to indicate a broad knowledge of Greek culture, some are known from Jewish literary tradition, while others were commonplace and conspicuous in a Hellenistic city and the Ptolemaic kingdom. Two references were also influenced by Hecataeus's Jewish excursus, a knowledge of which by a Diaspora Jew is only natural and does not indicate that he had an extensive Greek education.

The philanthropia attributed to Ptolemy I (Ap. I.186) indeed appears in Hellenistic literature as one of the basic notions of ideal kingship,[45]

[42] See Marrou (1956) 226-28.

[43] Philo in Spec. Leg. I.60-63 refers only to the belief of the ignorant mob (para. 60), because in that context he was eager to illustrate the moral and religious dangers facing Jews who turn to pagan mantics. This would have been less convincing had Philo seriously discussed the theological background of Greek mantics.

[44] Lewy (1932) 122ff.; cf. Guttman (1958-63) I.69.

[45] See p. 74 n. 65 above.

but this does not prove direct acquaintance with Greek political writing. The term was common in the koine and recurs in Hellenistic documents,[46] as well as in Jewish Hellenistic literature,[47] including Pseudo-Aristeas (paras. 208, 265, 271), which may well have been known to the author,[48] and even in Ill Maccabees (3.18), which was extremely hostile to the pagan world and its culture.[49]

According to the Hezekiah story, the High Priest "possessed in writing their settling [katoikesis ] and politeia " (Ap. I.189). Chapter VI.4 will discuss what is actually meant in this context by katoikesis and politeia.[50] But whatever the author had in mind, he was influenced by similar terms used by Hecataeus himself in his Jewish excursus (Diod. XL.3.3),[51] and by their current and even daily use in Ptolemaic Egypt. The influence of the Hecataeus excursus also appears in the passage on the large Jewish population (Ap. I.197; cf. Diod. XL.3.8).[52] In addition, it simply records the demographic pressures in the Judean Hills at the time of the first Hasmoneans,[53] as well as the first precept of the Pentateuch. It is not necessarily meant, as might be argued, to be an antithesis to the old Greek practice of infanticide (ekthesis ).[54]

The account of Jerusalem contains two details that were thought to have been influenced by Greek literary models:[55] the city is described as "most beautiful" (Ap. I.196), and the Temple is said to be located

[47] See esp. Meisner (1970) 162-78. See also Feldman (1989) 152-53.

[48] See p. 142 and n. 76 above.

[49] On the author of III Maccabees and his circle, see pp. 176ff.

[50] See below pp. 221ff.

[51] Regarding Hecataeus's influence on the Hezekiah story, see pp. 227-28 below.

[52] See Lewy (1932) 127; M. Stern (1974-84) I.43.

[53] On the overpopulation of Judea, see Bar-Kochva (1977) 170, 174-75, 191-94; id. (1989) 56-57.

[54] On references to high Jewish birth rates in Hellenistic and Roman literature and their purpose, see M. Stern (1974-84) I.33. To the sources quoted add Diod. I.77.7, 80.3 (Hecataeus on the Egyptians); Strabo XV.1.59 (Megasthenes on the Indians). On the new trend with regard to child rearing in Hellenistic literature and practice, see Rostovtzeff (1940) II.623-24; Deissmann-Merten (1984) 276-78; Golden (1990) 173.

[55] See Lewy (1932) 128ff.; Guttman (1958-63) I.69; M. Stern (1974-84) I.43; Doran (1985) 918, n. k.

"nearly in the center of the city" (I.198), while in fact it was built on the northeastern hill. However, the beauty of the city and its surroundings are lauded in the celebrated verses of Psalm 48, and could well have been reported by pilgrims from the Egyptian Diaspora. Coming from a flat land, they would certainly have been impressed by the hilly surroundings of the city. As for the location of the Temple, I have already mentioned that the Temple is not said to have been "in the center" as in a number of Greek utopian and philosophical works, but—significantly—"nearly in the center," and that this description accords with the topography of Alexandria.[56]

With regard to the report on the Temple, it has been argued that it is based on stereotypical temple accounts found in Hellenistic literature. Lewy tried to prove this by a comparison with Euhemerus's imaginary description of the Panchaean temple (preserved in Diod. V.42.6-44.5, VI.1.6).[57] However, there is no similarity whatsoever between the two accounts, neither in structure nor in detail.[58] A note that closes the report of the Jerusalem Temple has also been quoted as reflecting acquaintance with the "characteristics of a Greek temple":[59] Pseudo-Hecataeus states that in the Jewish Temple there are "no statue, nor any votive offerings, and absolutely no plants, resembling neither a grove nor anything similar" (Ap. I.199). However, the predominance of all these in Greek (and Egyptian) temples could not have escaped the notice of Jewish inhabitants in Egypt and in a mixed Greek polis.[60]

[56] See p. 146 and n. 23 above.

[57] Lewy (1932) 127.

[58] Lewy (ibid.) quotes the references in Euhemerus to the antiquity, splendor, and "favorable location" of the Panchaean temple of Zeus Triphylias as well as those to its size (Diod. V.42.6-44, VI.1.6-10). However, Pseudo-Hecataeus mentions antiquity, beauty, and size only with regard to the city of Jerusalem (para. 196), not the Temple. These details are missing in Euhemerus's account of the Panchaean city. As far as the Jerusalem Temple is concerned, the size of its wall is given, but not of the building itself, and the rest of the description bears no resemblance to Euhemerus's detailed account of the location, splendor, decoration, architecture, and surroundings of the Panchaean temple. Thus, for instance, the latter is located on the top of a lofty hill, 60 stades from the city (Diod. V.42.6, VI.1.6).

[59] See Lewy (1932) 129-30.

[60] To offer just one parallel: Jewish inhabitants of Haifa in Israel know quite well that the temple of the Persian Baha'i sect on Mt. Carmel is surrounded by beautiful gardens, and its shrine is decorated with marvelous carpets, while only a few of them know anything about the Baha'i religion and its literature.

Hans Lewy tried to trace typically Greek features even in the Mosollamus story (I.201-4). That Mosollamus's characterization is not typically Greek, and that the author was ignorant of the theological background, terminology, and practices of Greek divination has been shown above. Lewy's additional argument, that the literary features of the story disclose the direct influence of Greek tragedy,[61] is also unwarranted.

Lewy seems to have indicated as an influence the anecdote about Diogenes the Cynic ridiculing a seer,[62] but this must be rejected: it is narrated in a fictitious epistle written in the first century B.C.[63] At the same time, although it may have been quite a popular motif, I would not rule out the possibility that the author drew some inspiration from one of Aesop's fables containing a similar moral.[64] Fables were, in any case, elementary reading and composition material in Greek education.[65]

Finally, the linguistic and stylistic quality of the fragments should be examined. The very use of the Greek language is in itself no evidence: Demetrius the chronographer (second half of the third century B.C. ), who wrote a stylistically dull and poor account of Jewish history, certainly does not belong in the same category as Pseudo-Aristeas, Jason of Cyrene, or Aristobulus. The same applies to Eupolemus, whose Greek is rightly characterized as "pompous, crude, and poor," and tending to Hebraic structure.[66] The Greek of Pseudo-Hecataeus can be evaluated only on the basis of the passages quoted in direct speech, mainly the two longest and most complete fragments, the account of Jerusalem and the Temple (I.197-99) and the Mosollamus story (I.201-4). This does not provide much material, but the general features are quite clear.

[61] Lewy (1932) 129-30. See also Holladay (1983) 334 n. 52.

[62] See Lewy (1932) 129 and n. 4. The letter: EG , Diog. no. 38 (p. 253). The contents are summarized on p. 64 above.

[63] See the summary of research on the origin and dating of the "epistle" by Malherbe (1977) 14-22, esp. 14 n. 1.

[64] See fable no. 170, ed. Hausrath (Leipzig, 1970). While the fable may have influenced the story, I do not, of course, suggest that they have the same point; see pp. 64-65 above.

[65] See, e.g., Marrou (1956) 215, 239.

[66] See, Jacoby, RE s.v. "Eupolemos," 1229; Goodman in Schürer et al. (1973-86) III.519.

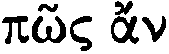

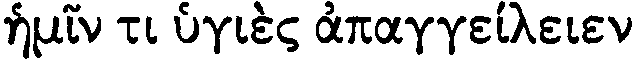

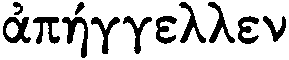

The vocabulary by and large lives up to the norms of the contemporary literary koine . The grammar is, however, less satisfactory; there are a number of instances of grammatical awkwardness. To be on the safe side, here are a few examples just from the Mosollamus episode:

1. Ap. I.201,

2. I.201,

3. I.201,

4. I.204,

[67] On loose genitive absolute in the koine , see Blass and Debrunner (1967) §423, but none of their examples is quite like this sentence.

[68] Cf. p. 51 n. g above.

[69] See the apparatus, p. 50 n. 18 above.

The style of the fragments is an odd mixture: the geographic fragment is written in a fluent paratactic style, using simple sentences without subordinate clauses. It resembles the traditional style of itinerary literature. The style of the Mosollamus story is different and syntactically rather diverse: the introduction (I.201) comprises a long, complicated period, employing extended clauses, a common rhetorical device. The episode itself (202-4), which should have been recounted in an entertaining and exciting manner, is told in a monotonous and boring style, two paragraphs (202-4a) sounding especially cumbersome. They contain a cluster of ten participial constructions (including seven genitive absolutes). The use of many participles can be expected in an epitome , and may occur in a historical narrative that tries to compress years and events, but the text is not an abbreviation, since it records in great detail occurrences that took place within a very short time, and even includes an imaginary dialogue. The unusual frequency of the participial forms, the change of the cases, and particularly the recurring changes of subject, make the sentences extremely strained. The style of these paragraphs recalls that of a grammatikos trying to summarize the plot of a tragedy or the like. Only the dialogue between Mosollamus and the seer (203-4) is of a much higher literary quality, using a fluent and simple "periodic" style. Josephus clearly did not rephrase the narrative part of the episode. This is not his style, even when abbreviating accounts of other authors. Moreover, it was pointed out above that Josephus himself stresses that the text of the episode is a quotation (200, 201); that subsequently referring the reader to the treatise itself (205), he must have striven to be accurate; and that the contents of the paragraphs show that they are not an abbreviation.[70]

This mixing of styles and standards is occasionally also discernible in the employment of expressions and phrases: thus, on the one hand, the author three times uses, in a complimentary context, the word

[70] See pp. 70-71 above.

[71] See Preisigke (1924) I.122-23, 126.

One must conclude that the author imitated various (even extremely different) styles. These were known to him from historical, geographical, rhetorical, and "grammatical" literature. While having attained some proficiency in these styles, he was obviously no very gifted writer, employing them inconsistently, and at least once not in the right context. The impression is of an author who had received tutoring in the primary subjects of Greek education, but by no means comprehensively. His education did not include, for example, basic poetical texts, and it certainly did not extend to philosophical literature. Consequently the overall effect is only partly satisfactory.

The standard of vocabulary and the very ability to employ a variety of styles should not mislead us in evaluating the author's degree of Hellenization. Even without attending the educational system of the gymnasium, linguistically talented orientals who were brought up using their mother tongue would have been capable of attaining a sufficient degree of proficiency to express themselves in a reasonable Greek style after taking private tuition or the like. The Greek of Pseudo-Hecataeus is far superior to that of Berossus the Babylonian,[72] but not to that of Manetho.[73] These two, who served in oriental temples at the beginning of the Hellenistic period, had fewer opportunities to communicate with Greeks and practice their language than would a Jew from Alexandria (or even from the rest of Egypt) of the late second or early first century B.C. For determining the position of the author in relation to the cultural and religious divisions within the Jewish community, it is important to stress that his Greek is less impressive, certainly less sophisticated (not necessarily always

[72] On the poor language and style of Berossus, see von Gutschmid (1893) IV.449ff.; Schnabel (1923) 29-32. On his life: Burstein (1978) 5-6; Kuhrt (1987) 48ff. Burstein's conjecture that at one time or another Berossus had served in the Seleucid court is doubtful and does not accord with some of his own assumptions. For an evaluation of Manetho's Greek, see von Gutschmid (1893) IV.419.

[73] On Manetho's life, see Waddel (1940) ix-xiv; Helck (1956) 15ff.; Fraser (1972) I-504-5; Mendels (1990). Josephus's great appreciation of Manetho's Greek culture (Ap. I.73) cannot be substantiated by the surviving fragments. From the following sentence it appears that Manetho's frequent criticism of Herodotus (cf. Waddel fr. 88) is what mainly impressed Josephus. No wonder Manetho was eager to become acquainted with the celebrated Greek account of ancient Egypt.

less accurate), than that of a number of Jewish Hellenistic authors: Aristobulus and Artaphanus in earlier generations, Pseudo-Aristeas in his time,[74] and Jason of Cyrene, who may have written his great work in those years; not to mention later Jewish authors such as Philo, or the authors of the Wisdom of Solomon,[75] IV Maccabees, and Joseph and Asenath. A similar level of familiarity with Greek language and culture (though dissimilar in style) is evinced in III Maccabees.[76]