Creative Strategies for Cost Control

Some firms have inaugurated creative strategies in this environment, striving to raise quality while minimizing cost. One example

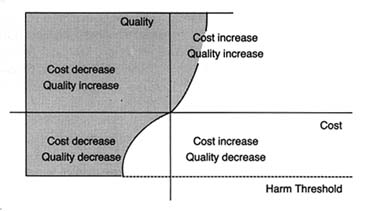

Figure 30.

Impact of cost containment on medical technology.

Shaded area represents positive effects."

Source: Nancy Cahill, esq.

is Acuson. Acuson designs, manufactures, and markets medical diagnostic ultrasound imaging equipment and has expanded sales throughout the 1980s. Its technology has several features that have helped it adapt to the cost-contained marketplace. The company's philosophy has been to develop products that are innovative, versatile, and capable of being upgraded or adapted to additional applications. For example, there are two major ultrasound imaging formats—sector and rectilinear. The former provides a wedge-shaped field of view, the latter a rectangular field. There are also three major ultrasound modes: imaging, Doppler (for analyzing blood flow), and M-mode (for cardiac analysis). Acuson's computed sonography system not only offers significantly better image quality but also provides films in both imaging formats and operates in all three modes. It can be upgraded primarily through software development without expensive investments in new hardware.

In 1985 and 1986, the firm added improvements without rendering its basic system obsolete or requiring customers to make major hardware changes. This flexibility allowed hospitals to acquire breakthrough technology efficiently. Acuson's system was identified as one of the products that "won big" in 1987.[11]

Gary Stephenson and Greg Freiherr, "Products that Won Big in 1987," Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry 10 (July 1988): 26, n. 13.

Thus, it has managed to compete with a number of domestic firms, including major players such as General Electric andHewlett-Packard, as well such important producers in the international marketplace as Hitachi Instruments, Philips Ultrasound, Siemens Medical Labs, and Toshiba Medical Systems. Many of these competitors have significantly greater financial and other resources and compete in more market segments than Acuson.

As the discussion makes clear, some products have attributes that minimize the complications and the barriers of the policy environment. Low-risk, cost-reducing products find a hospitable marketplace. However, many of our most desirable innovations are expensive to develop, may bring high risks along with their benefits, and may raise costs. The failure of the cochlear implant illustrates the sensitivity of the device industry to public policy. If the market is perceived by the innovators as too hostile, then technologies will fall by the wayside. Indeed, there is evidence in some fields, such as contraception, anesthesia, and vaccines, that innovation has been adversely affected.

On the other hand, there is also evidence of overdiffusion in the medical marketplace, at least for some technologies. Over-diffusion leads to misuse and abuse of medical technology, adding unnecessary risks and additional costs to the health care system. This phenomenon occurs because of the attributes of the medical market and the limited ability of public policy to control market failures.

Demand for medical technology is enormous and often undisciplined by the market. Providers of care are attracted to new technologies because of economic incentives, professional pride, and peer pressure to be innovators and leaders in their field. These professionals, in turn, are pressured by equipment manufacturers who tout the virtues of their products and, on occasion, by patients who hear about new treatments in the media.

These groups often overlook costs. Patients with third-party coverage are insensitive to price, and providers expect reimbursement for services they perform. Moreover, traditional referral networks among specialists are often based on patterns of trust among professionals without reference to comparative costs of services provided. Sometimes, too, fear of medical malpractice drives providers to order additional tests and procedures.

Of course, excess demand can be constrained by limited supply. As we have seen, efforts to control supply through certificate-of-need programs in the states have been relatively unsuccessful. Supply can also be controlled by third-party payers. If the payers refuse to cover a new procedure or technology, that treatment will effectively not be available to patients. Medicare and Medicaid are large payers that have an impact on market supply. As we saw in chapter 7, Medicare coverage policy is decentralized and fragmented. Regional carriers are subject to pressures from patients and providers demanding access to new procedures and technologies. Under pressure, these payers tend to cover the desired procedure.

Once covered, third-party reimbursement rates become crucial. As we have seen in the case of cochlear implants, a disadvantageous pricing decision can destroy a technology. Conversely, expectation of high profits often encourages overuse and misuse, as the case studies of the pacemakers and intraocular lenses illustrate.

Public payers are hampered in their coverage and payment decisions by inadequate information. Assessment of the costs and benefits of new technology is problematic. The need for more information on the effectiveness and costs of new technologies is high; the federal government has been unwilling to invest sufficient resources for assessment.

And, once profitability of a procedure is established, greed often follows need. Acquisition of equipment or special skills associated with a new technology or procedure create economic pressures. There is increasing evidence of supply-induced demand, particularly where demand can be manipulated by physicians and hospitals anxious to turn a profit on new equipment. Examples of excess supply include the proliferation of CT and MRI equipment and the overcapacity of mammography screening devices. The aggregate data support a conclusion of over-diffusion, since the United States alone consumes about one-half of the world's supply of medical technology.

This vicious cycle of demand fueling supply, then supply inducing demand is what constitutes the medical arms race. Public payers, such as HCFA, can affect this process, although its market share is too small to exert a strong influence. Congress

and HCFA have demonstrated neither a sufficient understanding of this process nor the political will to constrain providers and producers.