6—

Part I:

Pitch Structure

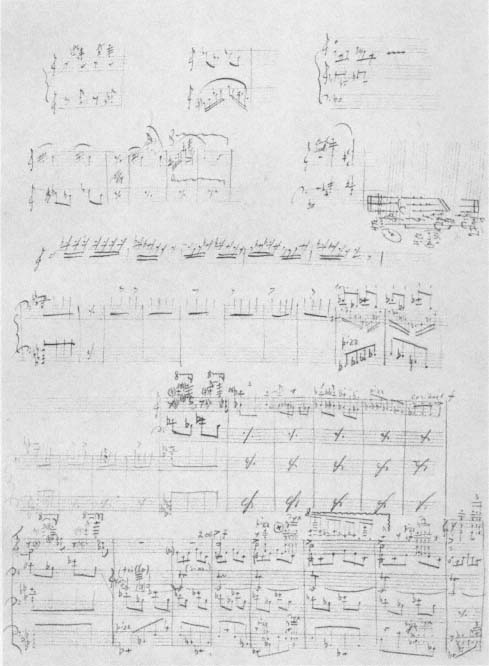

Sketches for the "Augurs of Spring"

Page 3 of the sketchbook of The Rite , reproduced in Figure 3 and transcribed in Example 58, consists of nine entries for the beginning of the "Augurs of Spring." At first glance it would appear that the fifth and sixth lines at the bottom of this page, each with four staves, were composed as a single entry. However, if these lines are read as a continuation of the fourth line directly above (where the "Augurs of Spring" or "motto" chord first appears), then the last three lines constitute, in proper succession, a remarkably accurate account of nos. 13–17 of the score. (Observe that the accentual pattern of the repeated chord, eight measures in length, is fully realized. The score itself extends, at the end of the fourth line, the D

Figure 3:

Early jottings and sketches for the "Augurs of Spring," page 3 of the sketchbook of The Rite.

The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps) Sketches , 1911–1913 ,© copyright 1969

Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Inc.

Example 58:

Sketchbook, p. 3 ("Augurs of Spring")

Example 58

(continued)

Example 58

(continued)

In his commentary to the sketchbook, Robert Craft has remarked that such details were unusual at so early a stage in the conception of a Stravinsky work.[1]

Pages 5 and 6 are likewise ostensibly devoted to the "Augurs of Spring." They include a sketch for the "break" at no. 22, entries for the new horn melody at no. 25, and a brief jotting at the bottom of page 5 for the transition or "modulation" at no. 30. Most elaborate, however, is a six-stave sketch at the top of page 6 for the beginning of the first climactic block at nos. 28–30. The latter even includes the melody, introduced by the trumpets at no. 28+4 of the score, that would subsequently serve as the principal motive of the "Spring Rounds." Following its appearance at the top of page 6, the succeeding material of pages 7–9 is in fact given almost entirely to the "Spring Rounds." (Recall that this was the original order of the dances: "Spring Rounds" followed the "Augurs of Spring," while the "Ritual of Abduction" came after the "Rival Tribes" and its succeeding "Procession." According to Craft, the "Spring Rounds" melody was one of Stravinsky's earliest ideas.)[2] The sketches for the "Augurs of Spring" on pages 3–6 underscore the prin-

[1] Robert Craft, "Commentary to the Sketches," Appendix I in the accompanying booklet to Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring: Sketches 1911–1913 (London: Boosey and Hawkes, 1969), p. 4.

[2] Ibid., p. 6.

cipal divisions of this movement as a whole. At the end of the Introduction there is a brief preparation or transition at no. 12. This is followed at nos. 13–22 by Section I, where the motto chord is first introduced, and then at nos. 22–30 by Section II, where two new melodies appear and the motto chord is dropped. Finally, the transition or "modulation" at no. 30 leads to Section III at nos. 31–37, the final climactic block of the "Augurs of Spring."

Somewhat puzzling in relation to the extended sketch are the initial jottings at the top of page 3. Not that the relationship of these entries to the "Augurs of Spring" at nos. 13–22 is in any way obscured. Except for the second line's second entry, where the chords are part of the Introduction's preparatory block at no. 12, all entries refer unambiguously to the extended sketch on pages 3–5. Puzzling, rather, is the immediacy of some of these jottings compared to the surprising gaps evidenced by others. The third notation of the first line is an accurate spelling of m.3 of the last line. On the other hand, the first entry's syncopated offbeat figure is inaccurate, down a whole step from its pitch at m.5 in the fifth line.[3] And the (B

All these jottings were undoubtedly composed in preparation for what follows below. Yet the extended sketch, in its overall comprehension and detail, exhibits such a stunning command of the "Augurs of Spring" at nos. 13–22 that the discrepancies revealed by some of these entries are not easily reconciled. Irrespective of whether pages 3–5 do comprise Stravinsky's first notations for the "Augurs of Spring," it is tempting to suppose that the extended sketch had been with the composer for some time prior to actual notation and that the prefatory jottings on page 3 were entered as "soundings" with a preexistent view toward the more precise plan of action detailed below.

Noteworthy in this respect are the sketchbook's initial entries for the "Glorification of the Chosen One" on pages 52, 59, 61, and 66–67 and those for the "Sacrificial Dance" on pages 84–85. These, as noted in Chapter 2, reveal a similarly developed character. And the role of the piano in Stravinsky's inventive processes, early on as an aid in improvisation and then in a constant "testing" of the ear, cannot sufficiently be stressed. Notice, for example, the easy right-hand-left-hand "lie" of the motto chord itself, which underscores the chord's compound nature, its triadically sealed top and bottom "halves." Here, too, then, the pianistic element is most conspicuous in those entries which are at the outset highly developed, suggesting the early, improvisational origin of this material. In contrast, the sketches for the Introduction to Part II and the "Mystic Circles of the Young Girls," material that lacks such a pianistic orientation, are among the most extensive and seemingly arduous in the sketchbook.

[3] Recall from Chapter 1 that this upbeat figure accompanied one of the composer's earliest ideas for the stage action, namely, that of "the old woman in a squirrel coat."

Indeed, when Stravinsky first examined the sketchbook after a period of some fifty years, he cited as his first notation on page 3 not the initial jottings but the motto chord at the fourth line (along, presumably, with its rhythmic pattern, eight measures in length).[4] And the foundational status of this chord has long been taken for granted. Earlier in the century, in his revisionist interview with Comoedia , Stravinsky claimed that the "embryo" of The Rite , "strong and brutal" in character, had been conceived while completing The Firebird in the spring of 1910.[5] André Schaeffner's biography, where much of the information is known to have come from the composer himself, acknowledged the chord as "the first musical idea," composed, however, during the summer of 1911.[6] Craft gave a similar account: the composer continued to single out the "focal chord" of The Rite , the E

At issue, of course, is not the authenticity of a left-to-right and top-to-bottom reading of page 3 (with the jottings preceding the fourth line), but whether this "chronological order" can be taken as representing the very earliest invention.

To recapitulate here for a moment: it is almost universally agreed that, following performances of Petrushka in Paris, Stravinsky began to compose his sketches for the "Augurs of Spring," "Spring Rounds," and possibly even the "Ritual of the Rival Tribes" during the summer of 1911 at Ustilug, Russia. He may have begun

[4] Craft, "Commentary to the Sketches," p. 4.

[5] "Les Deux Sacres du printemps," Comoedia , December 11, 1920. Reprinted in François Lesure, Le Sacre du Printemps: Dossier de presse (Geneva: Editions Minkoff, 1980), p. 53. For an English translation of the interview, see Igor Stravinsky, "Interpretation by Massine," in Minna Lederman, ed., Stravinsky in the Theatre (New York: Pellegrini and Cudahy, 1949), p. 24.

[6] Strawinsky (Paris: Rieder, 1931), p. 39.

[7] Robert Craft, "The Rite of Spring: Genesis of a Masterpiece," Perspectives of New Music 5, 1 (1966): 23.

[8] Ibid., p. 24.

[9] Craft, "Commentary to the Sketches," p. 4.

Example 59

in July, either before or after his visit with Nicolas Roerich, at which time the scenario and the titles of the dances were decided upon. Little could have been accomplished in August. The composer made trips to Karlsbad to settle the commission with Diaghilev, to Warsaw and Lugano to meet with Alexandre Benois, and finally to Berlin to visit his publisher, Russischer Musik Verlag, on matters pertaining to Petrushka . In fact, Craft estimates that the initial notations for the "Augurs of Spring" were entered after the composer's return from Berlin, on or around September 2.[10]

In a letter to Roerich dated September 26, 1911, Stravinsky informed his collaborator of his new address in Clarens, Switzerland, explaining that he had already begun to compose a dance, his description of which fits the "Augurs" movement.[11] Yet it is entirely possible—indeed probable, as suggested—that these sketches were preceded not only by considerable improvisation (both at and away from the piano), but by additional sketch material as well. The existence of sketches as much as a year earlier is confirmed by two letters from Stravinsky to Roerich dated July 2, 1910, and August 9, 1910.[12] And Craft has published what he believes to be the earliest extant sketch for The Rite : pre-dating the sketchbook, and given here as Example 59, it shows an E

[10] Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), p. 596.

[11] "Letters to Nicholas Roerich and N. F. Findeizen," Appendix II in the accompanying booklet to Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring: Sketches 1911–1913 .

[12] Ibid., pp. 27–29.

[13] V. Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents , p. 597.

other words, the order of the entries on page 3, even if authentic, in no way discounts the possibility that the motto chord of the fourth line might indeed have been the composer's first idea.

But how significant is the which-came-first argument? Can it matter all that much whether, as Craft now claims, the motto chord of the fourth line was derived from the D

Clearly the essentials here are: (1) that the notations for the "Augurs of Spring" on pages 3 and 4 of the sketchbook, whether in their most original form or not, probably represent the composer's earliest ideas for The Rite ; and (2) that these ideas, forming the very cornerstone of The Rite , introduce vertical and linear arrangements that are of paramount concern not only to a consideration of the "Augurs of Spring" but of succeeding movements as well. Regardless of which came first, the chord or its melodic conception, these arrangements are central to our analytic-theoretical perspective.

1. The three pitches of the D

2. The disengagement from the motto chord of E

3. Vertical or linear in conception, the superimposed quality of the configuration points in turn to the essential triadic makeup of the harmony in these initial pages.

4. Apart from arpeggios, melody is represented most prominently by the (B

[14] Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Expositions and Developments (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), p. 141.

terval order 2-1-2 (whole step-half step-whole step) and with a pitch numbering of (0 2 3 5). The D

5. The (C E G) triad, substituting occasionally for (E G

6. The outer pitches of the motto chord, E

And so pages 3 and 4 of the sketchbook introduce groupings or arrangements central to the "Augurs" movement and to the work as a whole: the vocabulary of The Rite consists in large part of 0–2 whole-step reiterations, (0 2 3 5) tetrachords, major and minor triads, dominant-seventh chords, and 0–11 or major-seventh vertical interval spans. (Again, as in earlier chapters, conventional terminology is employed for purposes of identification, with no intention of invoking tonally functional relations.) And although, given the reputation of this piece as one of considerable complexity, this reduction might seem a bit fanciful, we can narrow the scheme somewhat. The (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, as the principal melodic fragment not only of The Rite but of Stravinsky's "Russian" period generally, surfaces by way of all manner of reiterating, folkish tunes. As such, it is invariably articulated in the tightest or closest arrangement, confined to the interval of 5, the fourth (without interval complementation, in other words). It may nonetheless be either (0 2 5) or (0 3 5), incomplete, as noted already, with the D

The triads and dominant sevenths also assume a characteristic disposition: as with the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, the tight or close arrangement. This is not always the case but is customary, especially in the treble registers. The typical dominant-seventh placement is exemplified by the top half of the motto chord: closed position, "first inversion." Starting with the chord's E

By contrast, the 0–11 vertical span is rarely melodic in character (fragmental or

linear), but defines, harmonically or vertically, the span between pitches of unmistakable priority among superimposed, reiterating fragments or chords. Thus, as noted above, the E

Example 60

Example 61:

"Ritual Action of the Ancestors"

motto chord at no. 13, note the metric accentuation of the 0–11 span in these illustrations, an accentuation that typifies its articulation throughout The Rite , rendering it highly conspicuous from one block or movement to the next.

The Octatonic Pitch Collection

Listed above are thus the principal articulative units, the common denominators, so to speak, often with dispositions of marked character. What may in turn be judged the referential glue of this vocabulary, what binds within and between blocks and sections, is very often the octatonic pitch collection. More precisely, the referential character of this vocabulary is very often determined by its confinement, for periods of significant duration, to one of the three octatonic collections of distinguishable content.

As was defined in Chapter 5, the octatonic collection is a set of eight distinct pitch classes that, arranged in scale formation, yields the interval ordering of alternating 1s and 2s (half and whole steps). Such an arrangement obviously yields only two possible interval orderings or scales, the first of these with its second scale degree at the interval of 1 from its first (a 1-2, half step-whole step ordering), the second with its second scale degree at the interval of 2 from its first (a 2-1, whole step-half step ordering). These are shown in Example 62, with the 1-2 ordering and consequent (0 1 3 4 6 7 9 10 (0)) pitch numbering on the left side, the reverse 2-1 ordering and (0 2 3 5 6 8 9 11 (0)) numbering on the right. And the issue as to which of these orderings might pertain to a given context naturally hinges on questions of priority, vocabulary, and articulation. Thus the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord with its 2-1-2 ordering suggests the 2-1 ordering as cited on the right side in Example 62. And octatonic contexts which are (0 2 3 5) tetrachordally oriented will tend therefore to

Example 62

suggest this 2-1 ordering as the most favorable approach in scale formation. Similarly, when octatonically conceived, the 0–11 vertical interval span invariably suggests the 2-1 ordering and its consequent (0 2 3 5 6 8 9 11 (0)) numbering on the right side in Example 62; the latter is in fact closely linked to The Rite's (0 2 3 5) tetrachordal articulation. (Note, in other words, the 0–11 span of this numbering.) On the other hand, the (0 1 3 4) tetrachord, of only slight consequence in The Rite , and the root-positioned (0 4 7/0 3 7) major and minor triads tend more readily to suggest the 1-2 ordering on the left side of Example 62.

The collection is limited to three transpositions; there are only three octatonic collections of distinguishable pitch content. These are also shown in Example 62, labeled I, II, and III. Thus, respecting Collection I with the 1-2 ordering on the left side in Example 62: had we, following the initial C

Finally, note that the 1-2 ordering on the left side in Example 62 ascends, while the reverse 2-1 ordering on the right descends. This is in principle in order to allow representation of longer spans of material, spans that, confined to a single collection, may nonetheless in vocabulary and articulation implicate both orderings. In other words, respecting Collection I again, with the ascending 1-2 ordering at C

Still, the descending formula, the reading-down situation on the right side of Example 62, is not wholly a question of analytical convenience. In many "Russian" pieces it is often an "upper" (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, along with an "upper" pitch number 0, that assumes priority by means of doubling, metric accentuation, and persistence in moving from one block or section to the next. And if the scalar ordering and pitch numbering are to reflect these conditions, the descending formula is the logical course. Throughout large sections of the "Augurs of Spring," the "Ritual of Abduction" and "Spring Rounds" in Part I, a punctuating E

different octatonic collection, in this case Collection II.) Moreover, the symmetrical discipline conveniently allows for options of this kind. The 2-1–2 ordering and consequent (0 2 3 5) pitch numbering of this present tetrachord remain the same whether ascending or descending.

In general summation, Examples 63 and 64 partition the octatonic collection by means of the various articulative groupings cited above.[15] In Example 63 the 2-1 ordering is shown on the left side, where brackets outline the four overlapping (0 2 3 5) tetrachords at 0, 3, 6, and 9. Notice the two non-overlapping (0, 6) tritone-related tetrachords, which together yield the all-important 0–11 vertical span. Separate realizations are given below for each of the three content-distinguishable collections.

On the right side in Example 63 the familiar disposition of the dominant-seventh chord is applied in similar fashion. Here, too, superimposed over its (0, 3) minor-third-related major triad, the compound configuration, encountered already in terms of (E

Example 64 offers a different view of these formulae. The three collections are partitioned at four successive levels, by their (0, 3, 6, 9) partitioning elements at the first level and by their (0 2 3 5) tetrachords at the second. At the third level the 0–11 vertical span encompasses the upper 0–5 fourth of the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, while brackets encircle the lower of the two tritone-related fourths to cover those fewer instances where the lower or both of the collection's (0 2 3 5) (6 8 9 11) tetrachords prevail. Hence the 0–11 designation becomes 0–5, 11, or, more comprehensively still, 0–5/6, 11.[16] Indeed, in light of its comprehensive application, 0–5/6, 11 may

[15] See Pieter C. van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), pp. 48–60. In this earlier volume, the triadic and (0 2 3 5) tetrachordal groupings, yielding the ascending and the descending forms of the scale, respectively, are represented by two separate schemes labeled Model A and Model B. This strict separation was maintained in order to pinpoint critical distinctions involving the whole of Stravinsky's music, from the early "Russian" period to neoclassicism and early serialism. Here, however, with the analysis confined to the articulative routine of The Rite , these models are easily condensed to a single descending mode of representation.

[16] In connection with Béla Bartók's music, this 0–5/6, 11 vertical span was identified as "cell z" by Leo Treitler in his "Harmonic Procedure in the Fourth Quartet of Béla Bartók," Journal of Music Theory 3, 2 (1959): 292–98. Treitler's designation came in partial response to an earlier study by George Perle, where two other "cells" were labeled "x" and "y"; see George Perle, "Symmetrical Formations in the StringQuartets of Béla Bartók," Music Review 16 (1955): 300–312. The role of "cell z" in Bartók's music generally—its relationship to other symmetrical cells, interval cycles, and various octatonic and diatonic orderings—is discussed at length in Elliott Antokoletz, The Music of Béla Bartók (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), pp. 67–137.

Example 63

be envisioned as a kind of basic sonority in The Rite , the shell of its octatonic content. As was noted in Chapter 5, it accounts in large measure for the static "vertical chromaticism" that may be inferred: the upper (0 2 3 5) tetrachord or 0–5 fourth is made to stand in a fixed, polarized opposition to the lower pitch number 11.[17] At the final level in Example 64 the (0, 3, 6, 9) partitioning elements of each of the three scales are represented by round notes.

Example 64

Example 64

(continued)

Preliminary Survey

In its coverage of both Parts I and II, the analytical portion of Example 65 encompasses four successive stages.[18] Moving from a least to a most determinate stage, the first of these levels recognizes the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord as that unit which, complete or (0 2 5/0 3 5) incomplete, is shared by blocks and sections of varied articulative and referential implications, and hence as that unit which is more or less globally determinate or continuously operative with respect to the whole of The Rite . At the second stage the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord attaches itself to the octatonically conceived 0–5/6, 11 vertical span or shell, a formula that applies to passages of octatonic or octatonic-diatonic content, not to the few scattered patches of unimpaired diatonicism in Part I. The local articulation of these global units, acknowledged at the third level, yields the reference collection at the fourth level, where beams, parentheses, and the like confirm earlier-noted priorities and partitionings.

[18] The format of Example 65 corresponds somewhat to that of Example 27 in van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky , pp. 102–22. Here, however, the process has been streamlined. With a view toward The Rite as a whole, the dance movements of both Part I and Part II are taken into account, while the blocks selected for detailed treatment are often different. The accompanying graph, compressed in Example 66, also reflects a concern for The Rite in its entirety.

Example 65

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

Example 65

(continued)

The graph that runs at the foot of Example 65, pages 149–73, shows the general direction of the block and sectional transpositions, a sketch that is further compressed in Example 66. For the moment it will be useful to survey some of the initial realizations.

At no. 6 in the Introduction, the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord in the English horn—(0 (2) 3 5), incomplete in terms of (B

These relations are sustained in terms of (E

Critical at nos. 13–19 is the mixed (0 2 3 5) tetrachordal, triadic, and dominant-seventh articulation. As noted already, (E

[19] A more detailed account of Part I's Introduction is given in van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky , pp. 102–6, 124–26.

Example 66

Example 66

(continued)

Example 66

(continued)

Example 66

(continued)

The transposition of the (C B

Indeed, the embedded fourths in this Collection III-Collection I exchange at no. 19 (E

[20] The role of the interval-5/7 cycle in The Rite is briefly discussed in George Perle, "Berg's Master Array of the Interval Cycles," Musical Quarterly 63, 1 (1977): 10–12, and in Elliott Antokoletz, The Music of Béla Bartók , pp. 313–18. Pursuant to The Rite 's (0 2 3 5) tetrachords and the present descending approach in scale formation, emphasis is here placed on the descending 5-cycle rather than on the complementary 7-cycle (although, of course, explicit 7-cycle segments do occasionally arise in the "Augurs of Spring"). Chart 5, Example 68, and Charts 7–11 just ahead are plotted accordingly.

however, the broader implications of the cycle's intersecting role as suggested by the transposition to (B

Returning to the purely local conditions of the "Augurs of Spring," the introduction of the new (C B

Chart 5

Example 67:

Sketchbook

plicating the D-scale (or Dorian scale) on E

Interestingly, the new (C B

Coming by way of the transition at no. 30, the (E

The Diatonic Component

As can readily be seen in Example 65, the transposition to (D C B A) in the final climactic block of the "Augurs" movement is foreshadowed by the C-

[21] The first of these sketches on page 5 of the sketchbook, Example 67a, is crossed out.

A-D-A phrase of the opening bassoon melody and by the (D C B A) fragment at no. 6+4. Of concern at no. 37 in the "Ritual of Abduction," however, is the abrupt return to Collection III's (E

Still, patches of unimpaired diatonicism occasionally arise. The D-scale (or Dorian) fragment introduced at no. 37 returns in transposed form at no. 46. And in moving from the octatonic block at no. 44 to the unimpaired D-scale on F at no. 46, the connecting link or pivot, that which is in turn shared by these two blocks of distinct referential character, is the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord.

Thus the presiding (F E

Indeed, similar equations pertain to those blocks and passages of Part I where the octatonic and diatonic collections may be said to interpenetrate . At no. 10 in the Introduction two diatonic fragments in the clarinet piccolo and oboe are superimposed over Collection I's B

[22] The dotted lines in the analytical portions of Example 65 signify octatonic-diatonic interpenetration, with the octatonic component on the left side, the diatonic on the right. At the collectional level, brackets mark off the (0 2 3 5) units held in common.

Chart 6:

"Ritual of Abduction," nos. 44–47

In sum, the two adjoining (0 2 3 5) tetrachords of the octatonic scale are (0, 6) tritone-related while those of the diatonic D-scale are (0, 7) fifth-related. (The octatonic scale contains four overlapping (0 2 3 5) tetrachords, which, in passages of octatonic-diatonic interaction, could imply eight possible D-scales. Here we consider only the two adjoining ones.) And as shown in Chart 6, the critical point of distinction is likely to arise at the pitch-number 6/7 juncture of the two tetrachords. In moving from an octatonic to a diatonic or octatonic-diatonic framework, pitch number 7, replacing number 6, does in fact often intrude to signal this shift. At no. 25 in the "Augurs of Spring," only F of the (C B

Hence, as a subset of both the octatonic and diatonic collections, the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord serves as the principal connecting link between blocks of octatonic, diatonic, and octatonic-diatonic content. And when (0 2 (3) 5) is incomplete, it may in addition connect an (0 2 3 5) partitioning of the octatonic collection with a dominant-seventh partitioning, closed-position, first inversion. Hence, too, as a surface-articulative unit, it embodies matters of deep structural concern to the harmonic, contrapuntal, and referential character of The Rite .

The Interval-5 Cycle

Explicit delineations of the interval-5 cycle are found in the "Augurs of Spring," the "Ritual of Abduction," and the "Dance of the Earth." Most telling in the "Augurs" movement is the E

Indeed, even with the diatonic fragments of Part I, fragments whose framing octaves and (0 2 3 5) tetrachordal formations readily suggest the D-scale ordering, openly articulated fourths can point to the 5-cycle as a constructive and referential factor. Shown in Examples 68a–68c are five diatonic fragments taken from the Introduction and the "Abduction." Separate columns in this example reveal the (0,2,5,7) pitch-class set, the D-scales, and the compression of these latter scales as segments of the 5-cycle. The two diatonic fragments at no. 10 in the Introduction are framed by octaves and exhibit an explicit (0 2 3 5) tetrachordal articulation, circumstances that readily imply the two D-scales on F and B

In Chart 7 the content of the Introduction's climactic block at no. 10 is displayed as a nearly complete 5-cycle.[23] The pitch-class content of the diatonic fragments in the flutes, clarinet piccolo, and oboe (see Example 68b)

[23] Charts 7–10 are modeled after a design used in Elliott Antokoletz, The Music of Béla Bartók .

Example 68

Chart 7:

Introduction

yields the A

Chart 8:

"Augurs of Spring"

Chart 9:

"Augurs of Spring"

Similarly, the embedded fourths in the superimposition of (B

There are important connections among several of the 5-cycle segments traced in Example 68 and Charts 7–10. The E

Chart 10:

"Dance of the Earth"

Chart 11

reappears in the "Dance of the Earth." Yet the limitations of the 5-cycle as an explanatory tool, even when it is applied in conjunction with other interval cycles, are at least equally apparent in these illustrations. The cycle tends to skirt essentials of vocabulary and disposition, especially the triads and dominant sevenths, groupings with special articulative and registral implications. And while its circumvention of priority and octave considerations is at times both convenient and appropriate, the (0 2 3 5) tetrachords and octatonically conceived 0–5/6, 11 spans can more often than not ensure the more determined conditions of a scalar ordering. (As should be evident, the analysis of Examples 65 and 66 provides a far more detailed and explicit picture of pitch organization on both a local and global scale.) Nor, as we shall see, is the cycle of much use when confronting The Rite as a whole. In order for it to be effective, inferred segments must exhibit pitch-adjacency or, if severely gapped, a pattern of some sort. Apart from some of the above-noted passages, this is seldom the case in The Rite .

Summations

The prevalence of E

to the D-scale on E

More critical still is the final return to E

A second area of contention in Part I entails D and the (D C B A) tetrachord. Here, too, details have been noted: the (D C B A) fragment in the Introduction at m.2 and no. 6 + 4, the transposition to (D C B A) at nos. 31–37 in the "Augurs of Spring," and the appearance of (D C B A) as part of a new D-scale fragment at no. 37 in the "Abduction." The affiliation of (D C B A) with Collection II materializes slowly and is first established at no. 44. In the "Procession of the Sage," the reiterating A-D-C-D fragment in the horns (an incomplete (D C (B) A) tetrachord) along with the G

Note, finally, the persistence of Collection II's D-A, E

Beyond these tetrachordal or collectional priorities, associations, and links, however, The Rite does not readily submit to the imposition of an all-embracing plot, one of intrinsic interest (exhibiting a form of symmetry, for example) or tied in some fashion to local details of significance. The interval—5 cycle is not a convincing model in this respect. Apart from its E

Nor, for that matter, can the reduction of Example 66 be equated with a "Schenker graph." As a series of "progressions," the beams connect the various realizations or transpositions of important globally defined units from one block or movement to the next. And while these shifts inevitably yield a voice-leading path, the meaning or significance of this path is far from apparent.

The question, in other words, is why one particular octatonic or diatonic collection (or transposition) should necessarily succeed another. What, in the final analysis, accounts for "progress" in this piece? At nos. 38 and 40 + 6 in the "Abduction," for example, why should Collection III's (E

No doubt Collection II's presence at nos. 38 and 40 + 6 is foreshadowed by the transposition to (D C B A) at nos. 31–37 in the "Augurs of Spring" and anticipates the Collection II block at no. 44. The original chronology of these dance movements, according to which the "Abduction" at no. 37 followed

the "Rival Tribes," allows a more compelling explanation: the C-B fragment in the percussion and lower strings at nos. 38 and 40 + 6 served as an immediate link to the tuba's C-B fragment in the opening measures of the (then preceding) "Rival Tribes." And since, in relation to the opening (E

It should also be noted that conventional notions of harmonic progress, voice leading, and "directed motion" are qualified not only by the symmetrical implications of octatonic construction but also by the two types of rhythmic structure. In blocks and movements adhering to Type II, which include the "Procession of the Sage" and the "Dance of the Earth," pitch organization is necessarily static. Essentials here include the registrally fixed layers of reiterating fragments, the referential implications of these layers, points of intersection, and the varying periods defined by the repetition in relation to an assigned or readily inferable metric periodicity. Conventional voice-leading graphs applied to settings of this type would be essentially meaningless. Similar reservations pertain to the large block structures of Type I. The point of this invention rests with the modification and reshuffling of the juxtaposed blocks upon successive restatements, a juxtaposition in which the blocks often retain separate collectional identities. And since with larger block settings—as at nos. 57–62 in the "Rival Tribes" (Example 38 in Chapter 4)—the same blocks are always preceding or succeeding one another, a true sense of progress can come only with an abrupt cutting off of the entire section and with its further juxtaposition with something quite new in formal, rhythmic, registral and/or pitch-relational design. It is with these considerations in mind that the analysis of Example 65 and its accompanying graph in Example 66 are best understood.