Casamac and Duma'an

Before World War II, the Filipino poor left little printed testimony concerning their reactions to events that changed their lives. Moreover, many of those in the past who claimed to speak for tenant farmers and laborers exhibited little understanding of or empathy with them. Often these putative spokesmen represented the interests of the upper class rather than those of their adopted charges. Historians recently have pointed out that, in several instances at least, the rural farmer's world view differed widely from that of the landholder, that the two outlooks were positioned at a greater distance from one another than is normally implied in the great tradition-little tradition dichotomy. Patron-client paternalism did not necessarily produce the kind of symbiosis that allowed planters to fathom the thinking of those who labored in their fields; rather, opportunism, a patronizing attitude, and even adversariness characterized that relationship. Evidence suggests that workers in sugarlandia shared this same fate of being little or badly understood by litterateurs.[43]

In 1964, as part of my research on local history, I conducted an anonymous informational survey among older men in Pampanga concerning their memory of their lives before 1920. Among the respondents, 149 former sugar tenants and thirty landowners provided data about their

residence, education, and employment in the sugar industry during this century's first two decades. Aside from brief, biographical answers, many of these interviewees, who ranged in age from 69 to 104 years, volunteered more extensive comments about their work experience. Their insights, given to the local teachers and college students who acted as surveyors, offer some unusually frank comments on tenant-landlord relations. The forty-four intervening years, eventful and tumultuous as they were, did not erase for some of these old men vivid memories of their days laboring in the sugar industry.[44]

Perhaps the clearest notion that emerged from these interviews was the contrast in perceptions between landlords and casamac about their relationship: landholders considered that their tenants felt a deep sense of gratitude toward them for the treatment they received, while tenants often expressed resentment and fear. The following statements demonstrate this contrast, the first from a landholder in Angeles:

My brother and I tilled the soil—our own land—and had helpers, wards of my father. We treated them like members of our own family. They lived with us. We supplied their necessities and we did not maltreat them. I remember they loved us very much. My father saved one of them from the Guardia Civil during Spanish times. My father held the position of cabeza.[45]

A retired school teacher and hacendero from Guagua described the samacan system in these terms:

We were like one big family. They treated us like their parents and we treated them like children. When the planting began and they came to the house for the cuttings, they brought along firewood of their own volition, and I was thankful for their gesture of kindness.[46]

Another planter, from San Fernando, added:

My father was a farmer with around a three-hundred-hectare hacienda. . . . The sharing of crops was fifty-fifty and the expenses were also on a fifty-fifty basis. The tenants loved my father. They would come and help us during fiestas, bringing us gifts of fruits, chickens, and sweets.[47]

While some tenants considered their landlords paternalistic, the majority were more resentful. An 84-year-old tenant from Porac gave the most positive comment about the relationship:

The tenant and the landowner share fifty-fifty. . . . The landowner calls for the tenant when the Chinese buyer comes—

everything is done in their presence and with their consent. No interest on money and rice. The landowner (Hipolito Coronel) was very humane. He treats his tenants as member of the family. The tenants are served their meals at the family table.[48]

On the other side, a casamac from Guagua stated:

The tenants would serve the landlord by cutting wood for fuel for him, cleaning his yard and his house, and giving him gifts of chickens, firewood, and carabao milk whenever he had a fiesta. No request of the landlord was ever turned down. Of course, the landlord had a way of discriminating among his tenants. It must be kept in mind that the landowner has foremost in his mind the increase of his production. Nevertheless, there were times when a landlord would remove his tenant from his farm for failing to please hirn. There were even cases when the landlord cut out the ration of the tenant altogether.

A common practice of the landlords at that time . . . was that every weekend when the tenant's wife went to see the landlord for the next week's ration, she was made to clean the yard, the house, or made to cook the landlord's meal before she was given the ration, which time was usually shortly before noon or even later.[49]

Another, from Angeles, said:

My landlord would ask me to do odd jobs for him without pay, even to the extent of cutting wood, which was about three carloads, and delivering it to his house. My wife used to dean clothes and clean the house of my landlord. She, too, received no compensation for it. At the end of the milling season our debts were cleared. Of course we were the poor, then oppressed by the rich. I did not complain. We were not allowed to, and nobody dared to.[50]

Fear of landlords appeared in numerous comments, including one by a tenant, 73, from San Fernando:

I started selling firewood at the age of about ten or eleven years old. We were very poor. My father was a tenant farmer. He had no carabao. . . . At that time we were much afraid of our landlord. My father could not answer back for fear of be-

ing removed from his work. My father's landlord cheated my father.[51]

One from Mexico testified:

My landowner was the kindest among the Panlilios. I was formerly a tenant of Don Vicente Panlilio, but something happened. I asked him once if he thinks that the price he gave to my crop was too low. But it happened that he was out of mood at the time I asked him. I have always considered myself one of the most faithful tenants, but that time he got angry with me and he started shouting at me. Plenty of co-tenants heard me because we were in the fields at the time. They were angry at me because I didn't assert my right. They said I was a weakling. All of them were mad at Don Vicente. Then it happened that Don Bengang Panlilio, his cousin, needed one more tenant, and I asked Don Vicente if I could transfer to his cousin's hacienda. He was no longer angry at that time and he refused to let me go. My landlord was just temperamental. I understood his moods because I knew he has some Spanish blood.

Later on Don Bengang asked Don Vicente if he could spare one, and that was when I transferred to Don Bengang's hacienda. He was a very kind old man—very fatherly; although he also had some bad moods, he was very kind compared to Don Vicente. There were even some brothers of Don Vicente who whipped their tenants.[52]

That whippings occurred on occasion was confirmed by another Mexico tenant, age 78, who revealed:

During those times even grown men got beaten when the landlord, Pablo Panlilio, did not like what he did. We said a tenant was given "two cavans" if he gets whipped fifty times, because one cavan was equal to twenty-five gantas. . . . And the whip he used was not just an ordinary kind, it was especially made for the purpose of whipping tenants. It had a leather case, the handle was made of a metal and gold plated, and the stem was of thick rounded leather. When the landlord asked his servant to bring out the whip, everyone in the barrio trembled in fear. Even how much one hated the tenant being beaten, one felt pity when the whip was taken out. Everyone gathered to see, and the family most of the time cried for mercy. The landlord rarely used the whip, however. He used it only in extreme cases, but I did see him use it once when I

was a small boy, and the memory stayed long in my mind. The tenant was not like a human being when he was being beaten. During the first few whippings he shouted in pain, but after that he did not cry anymore, because he became numb.[53]

If Pampangan tenants expressed a sense of helplessness in the face of planter power and authority, they also conveyed a sense of hopelessness as well. A 76-year-old tenant from San Fernando offered a common sentiment of the era:

Although the sharing of crops was on a fifty-fifty basis, the tenant shouldered his expenses on the farm. Whatever he got from his landlord in cash or kind (cigarettes, rice, sugar) he paid back. He worked for his landlord like a slave. . . . What was not quite nice was that most landlords cheated their tenants. . . .

The tenant does not get his share of the harvest because he has no place to store it' and he does not have connections with big buyers like the Chinese, et cetera.[54]

The endlessness of unrewarding work appeared further in a statement from a 100-year-old tenant from Angeles:

I was supposed to receive one fourth of the sugar production which we placed in pilones. No sugar and no money was given to me in return, for my share was kept in my landlord's storehouse. He sold my share as he pleased without my knowing the selling price. I was just informed of the cost of my ration every time I came to get it. At the end of the next harvest, I was informed of the balance of debts. I got so fed up with such treatment that I gave up the work. My son who was then quite big worked in my stead.[55]

Landholders at their most paternalistic expressed their reluctance to loan money, for it encouraged long-term indebtedness, and three of them commented:

I used to limit the loans of my tenants, because I wanted them to make a little sacrifice for their future. I did not collect interest on money I loaned them. I even gave them lessons on how to produce more, once in a while.[56]

When I lent my tenants any amount of money, I charged twenty percent interest to prevent them from borrowing often and spending the money for gambling. When my father died, I canceled all debts of my tenants.[57]

My father . . . always gave his tenants money as often as they came to borrow, so that when I took over, I found many of the tenants with debts as big as five hundred pesos, six hundred pesos, and a thousand pesos. There seemed to be no way by which they could pay their debts, so I forgave them their debts and told them to start anew. I often gave them lectures on thrift. There were two bad traits I observed common to most tenants—indolence and extravagance.[58]

Despite these charitable sentiments most tenants borrowed to survive, and most landholders loaned them the cash, the majority of the latter charging some interest rate between 5 percent and 20 percent for cash. And this system resulted in a recurring round of indebtedness that left tenants without hope of breaking free. A 95-year-old tenant from San Fernando revealed his thoughts in this manner:

The landlord at that time would give you any number of pilones of sugar as he pleased. We could not complain for fear of being removed from our work. We were much cheated and we poor people were treated as servants. We worked as tenants to pay for the debts incurred by our parents, and our children would in turn work as tenants to pay for our debts to our landlords. We worked day and night. The landlord's word was law.[59]

Perennial debt and inability to alter their situation informed the thinking of casamac in Pampanga; however, these attitudes did not necessarily determine their reaction to a specific hacendero. Rather, along with adequate subsistence tenants expected, even insisted upon, fairness from landlords. Casamac opinion about their relations with others as well depended on this need for fairness, and wrong was measured by just how inequitably someone treated them. The following narrative concerning the arrival in 1916 of the cadastral survey in Magalang reveals a long-remembered slight harbored by a 74-year-old tenant of that town:

I remember clearly—the police came and gathered us. They told us to go to the tribunal [municipal building]. But we were afraid of the police then, and we never wanted to go near the tribunal for we associated it with being imprisoned. They told us to register our land, but we didn't want to have anything to do with the police. We didn't go to the municipal building, and they came and asked us why. We told them we were very busy working in our fields. They then told us that a man would register our land for us. We were ignorant at the time

and we were happy that this man would register for us. We found out later he registered it in his name.[60]

Most tenants in this era possessed no legal claim to land, only traditional rights through the samacan, and the registering of titles did not directly affect them; however, the perception of inequity on the part of those associated with the survey made many tenants view the cadastral program negatively.

Casamac operated on a basic sense of justice in dealing with landholders; and above all the implied paternalism, they needed to be satisfied that they received enough and that their contracts operated fairly. A tenant from San Fernando expressed this sentiment succinctly:

During that time the landlord bore all the expenses on the farm, and all the production went to the storehouse of the landlord. He gave us our necessities—food, clothes, shoes, and other things—and we did not know our share. We just lived buried in debt to our landlord. We were like members of his family. He disciplined us and we were afraid of him. We were not given enough subsistence and we left him.[61]

The samacan functioned in such a way that tenants seldom improved their economic condition, largely because opportunities to profit all remained in the hands of hacenderos. The latter kept the books, warehoused and sold the finished product, set interest rates, and often loaned stores, equipment, and draft animals. Choosing where to profit at the expense of tenants remained a matter of individual landlord style, and the manner selected often determined casamac reaction. Charging moderate interest on loans did not appear to cause undo reaction, providing other parts of the contract proved acceptable; charging no interest compensated for other exactions by the hacendero. A satisfied tenant from Guagua described his relationship this way:

My share of the sugar was paid in cash to me by my landlord, usually a peso less than the current selling price. The molasses went to my landlord. Any amount of money I borrowed from my landlord did not bear any interest. The relationship between us was paternal.[62]

By far the biggest perceived inequity on the part of tenants dealt with the matter of selling finished sugar to brokers. Planters often did not seem to realize the distrust they created with these financial dealings; rather, they believed that they did the casamac a favor (or fooled tenants into

thinking so) in handling the complex negotiations. Three landlords gave different justifications for dealing alone with the Chinese brokers:

During those times tenants were treated very well by us. We did not ask any interest. . . . They were free to ask for help anytime they needed it. Only we were the ones who purchased the whole crop, including theirs, because they might be cheated by Chinese merchants.[63]

When we sell the sugar I got the average price of sugar and I multiplied it by the number of piculs. That was how I gave an accounting to the tenants. Sometimes I sell several piculs at a certain price and the week after I sell several other piculs at a higher price. I get the average of all these prices and that was the price I based the accounting on.[64]

If I sold a pilon of sugar at twenty-five pesos, I charged it to [the tenant] at twenty-four pesos. My gain was one peso, which was in the form of a gift to me for selling my tenant's share.[65]

No matter how hacenderos justified their negotiations, tenants found them the greatest source of injustice in the samacan contract. Two representative tenant comments reveal the hostility and misperception that underlay the Pampangan labor arrangement:

In sugar production we farmers were cheated most of the time. If a pilon of sugar cost twenty-five pesos in the market, the landowner will first tell the poor farmer any amount he wishes to tell him. Any complaint by the farmer in this accounting will mean his firing from his job.[66]

The landlord treated us kindly in words. I know very well that they were cheating me, especially in sharing the crop, which is supposed to be on a fifty-fifty basis. . . . And when it comes to sharing harvested sugar, the crop was first put in the bodega of the landlords. Then they did everything they can to cheat us. However, they lend us money without interest, provided it will be paid back in not longer than one year.[67]

Tenants who sold their own share usually defended their samacan relationship as fair, but such individuals remained a small minority. Perceived inequities as early as the first two decades of the twentieth century threatened the social order that had developed over the preceding years.

In 1970 a similar survey collected responses from duma'an and other sugar people from Negros concerning their life in the two decades before

World War II.[68] Among the interviewees were eighty-two duma'an from 70 to over 100 years of age who supplied observations concerning their early days working on haciendas. Because of the time lapse between the two surveys and the different period emphasis of the later one, the data collected are not quite comparable; nevertheless, these older Negrenses did offer recollections of the late frontier period. And their comments on their working life contrasted in some ways with those of Pampangan casamac.

Duma'an evinced somewhat more satisfaction with their conditions than did their northern counterparts, perhaps reflecting the better market conditions that prevailed in Negros in the the early twentieth century. While no hacienda laborer admitted to improving his circumstances, they generally felt their subsistence needs were met. An 80-year-old retiree from Murcia supplied this response:

My life as a hired worker of the hacienda was much better during that normal time, even though wages were so small as compared to wages now. At the rate of fifty centavos a day I could still support my family, since prices of foods were very much lower as compared to prices now. I can also let my children go to school, but, due to their [negative attitude], they didn't even reach the intermediate grade.[69]

Several of the comments, however, contain a certain ambivalence: their wages had to suffice, because no alternative sources of livelihood existed. Three examples from octogenarians in. Hinigaran, Isabela, and Himamaylan exemplify this sentiment:

We received no consumo [rations]. . . . Life was hard but I couldn't complain about my financial problems for fear of losing my job. I had to work in the field every day, even when I wasn't feeling well, since my earnings were paid on a daily basis.[70]

We were given consumo and the amount was deducted from our salary. I was contented with my earnings. It was a hand-to-mouth way of life. I supported my family with my meager income. Everything was cheap during that time, so no worry at all, although this income was not enough to meet daily needs.[71]

There were no major troubles, although the landowner didn't give any privileges to his laborers. They couldn't get any cash

loans from him, nor get any help in bad times. Laborers would just have to bear the kind of management they have.[72]

The remarks of the minority who proclaimed dissatisfaction with their hacienda wages contained overtones of a fear and helplessness that bonded them to their poor situations. Three retired duma'an, two from Pulupandan and one from Binalbagan, made representative comments in this vein:

There were no labor troubles. If you do good in your work you won't have any trouble at all. They were treated well by the owner, if they only follow what the owner would like them to do.[73]

Laborers couldn't complain—otherwise they'd be ousted. They just waited for instructions and payday. They never complained because they reasoned that the landlord wouldn't help them anyway.[74]

I just obeyed orders. At times I complained to the cabo because of too much work, but the cabo didn't listen to my complaints. I just worked and obeyed orders.[75]

Not so surprisingly, the only statements that revealed open resentment came from or referred to sacadas. As noted earlier, the one group over which hacenderos complained they exerted little control and which caused them the most trouble were these seasonal workers from neighboring islands. Many sacadas later settled on Negros haciendas and became duma'an, but so long as they remained transients, they maintained an independence unavailable to permanent staff. A 70-year-old duma'an from La Carlota commented:

Trouble arises only if the amount paid to the laborers in the pakyaw [piece work rate] was very low. Laborers would stop working if the landowner would not raise the salary.[76]

Another duma'an from La Carlota remembered the time around 1920 when he came from Antique Province, Panay, to cut cane on Negros. He observed:

Labor troubles arose only during payday when the laborers couldn't receive their salary, especially those under the pakyaw system, and recruited by the contratista. There were sometimes contratistas who didn't give the salary to the laborers but, instead, used the money for themselves.

During those times laborers were treated like animals. There were foods served for the laborers, but foods which weren't prepared well—like rice which was not cleaned well.

There was also a laborer on one of the haciendas in Bago, owned by a Spanish mestizo. He tied the laborer to a tree and let the ants bite him, because of the cane that the laborer wasn't able to cut because he didn't feel well.[77]

A comparison of the collective responses of Pampanga casamac and Negros duma'an points to a similar harsh perception of conditions on the sugarlands of northern Pampanga and the Negros plantations. The casamac, however, appeared to see more unfairness in their relations with landholders than did the duma'an, or at least they expressed their sense of the injustice more often. But such a comparison might be misleading. The surveys involved the memories of old men, some of whom volunteered fuller answers than others. Further, the years between 1920 and the 1960s and 1970s witnessed vastly different political experiences within the two areas, and the replies of the casamac may have been colored by the politically charged atmosphere of 1964 Pampanga. Negros Occidental in 1970 harbored a far more repressive and orderly climate. It is possible, of course, that different cultural backgrounds, living arrangements, and conditions of employment in the two regions accounted for the dissimilarities in declarations of injustice. Perhaps the Capampangan expressed themselves more openly because they possessed collective ways to reveal their resentment. Does other evidence buttress or discredit these disparities in actions and expression?

While direct corroborating testimony does not exist, reactions among rural farmers to two turn-of-the-century messianic movements, one in Pampanga, the other in Negros, tend to confirm the differences in attitude and outlook expressed by the elderly casamac and duma'an. Folk leaders Felipe Salvador—Apong (Saint) Ipe to his followers in Luzon—and Dionisio Sigobela, the Negrenses' Papa (Pope) Isio or Dionisio Papa, seemed to have parallel careers in their respective regions; however, the nature of the support they received reflected regional cultural and historical differences that gave each movement a distinctive flavor, despite a common impact on both of the Philippine Revolution and an expanding sugar industry.

Salvador distinctly belongs to an old Philippine tradition of chiliastic leaders who draw upon folk Catholic themes and practices to express peasant world views. Movements in a similar vein to his own sprang up in central Luzon from Laguna to Pangasinan from at least the mid-nineteenth century onward. In 1894 he formed his own group, Santa Iglesia

(Holy Church), among followers of a sect founded in the late 1880s by Gabino Cortes of Apalit, Pampanga. Salvador himself grew up in the nearby Tagalog town of Baliwag, Bulacan, and spoke that language as his native tongue; nevertheless, he had strong influence within the Capampangan-speaking community. He eventually held sway in the rural barrios of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Pangasinan, and Tarlac as well as Pampanga, communities that he visited first from his base in Barrio Camias, San Miguel, Bulacan, then from hidden centers on Mount Arayat and in the Candaba Swamp.

At the onset of the Philippine Revolution in 1896, he shifted away from his initial, strictly religious focus and created a militant arm to fight for independence, his troops first confronting Spanish forces in San Luis in 1896. After a retreat to Biak-na-Bato (near Camias) to join Aguinaldo, Salvador's army of church members fought again in February 1898 at Apalit and Macabebe, in both cases suffering considerable losses. With the arrival of the Americans, the soldiers of Santa Iglesia took to the field again and achieved success in capturing a hundred rifles from the Spanish garrison at Dagupan, Pangasinan. This feat and others earned Apong Ipe the rank of colonel in the revolutionary army, and in July 1898 he paraded with rive hundred of his followers triumphantly through the streets of Candaba.

Despite these contributions to the cause, local elite officers from Pampanga refused to treat Salvador as an equal, abused soldiers of Santa Iglesia and their families, and accused Apong Ipe himself of desertion in the line of duty. In a reasoned defense to Aguinaldo, the religious leader made it dear that Pampangan principales objected to his troops' loyalty to him and their combining military with religious activities. The elite felt they deserved to command the poor of the province and resented this threat to their authority. Because of his appeal and his loyalty, Salvador earned a favorable ruling from his commander in chief on the charge of desertion and retired to the Candaba Swamp area in time to organize a guerrilla campaign against the American army. Captured in 1902, he escaped to the wonder of his followers—and subsequently conducted religious services and directed a guerrilla war for independence, long after other Pampangan ofricers had sworn allegiance to the new regime.

For eight years Salvador and his apostles wandered the rural barrios of central Luzon preaching devotion and brotherhood. The military wing under the command of Manuel Garcia, known as Capitan Tui, made lightening strikes against unsuspecting constabulary outposts in such places as San Jose, Nueva Ecija (1903), Mabalacat (1903), and Malolos, Bulacan (1906). The constabulary killed Garcia in mid-1906, and military raids diminished thereafter; however, as late as 1910, in the fateful year

of the appearance of Halley's comet, peasants and former soldiers from south of Manila to Lingayen Gulf still looked to Apong Ipe to revive the Revolution and expel the Americans. The colonials and cooperating native elite still considered Felipe Salvador a danger to public order. His capture came about at his home in Barrio San Isidro, San Luis, in the midst of the Candaba Swamp on July 24,1910, the result of a joint effort between secret agents from Governor Arnedo's office, municipal policemen, and constabulary troopers. The government charged him with sedition and on April 15, 1912, at Manila's Bilibid Prison, executed him by hanging.[78]

Santa Iglesia did not vanish with the disappearance of its leader. In 1913 Governor Liongson reported confidentially to the executive secretary in Manila that the Salvadoristas still congregated peacefully and regularly. Evicted from a barrio of Angeles, 150 of the faithful removed to the slopes of Mount Arayat, the old haunt of their slain Apong Ipe. The governor ordered their leader, a man named Cortez, to appear before him, and this spiritual guide dutifully did so, accompanied by Angeles vice-mayor Ireneo Abad Santos, a planter and younger brother of Pedro. Cortez seemed to agree to disbanding the group, and Liongson considered the matter closed, attributing the whole incident offhandedly to opponents of independence. However, in 1970 I visited the Santa Iglesia headquarters, still in Barrio San Isidro, San Luis, and found that elderly adherents maintained two churches in that community. One of the original apostles of Apong Ipe, Victor Larin, who was 101 years old, presided over one of the structures and asserted that the Santa Iglesia never died, although at that time its membership consisted only of very old parishioners living in the surrounding barrios.[79]

While Salvador centered his movement in the wetter, rice-growing portions of Luzon, his sway reached into sugar-growing Pampanga. From his vantage on Mount Arayat he possessed easy access to the rest of the great plain that stretched out from its foot. After their attack on Mabalacat in August 1903, his raiders fled north to safety in Tarlac, where Salvador had a considerable following. Driven from Arayat town center in 1910, he found sanctuary for a 'time in the sugar community of Floridablanca. Finally, as Salvador notes in his abbreviated spiritual autobiography dictated on the eve of his execution, he received hospitality from two tatcheros (those who boil sugar), indicating a kind and enthusiastic reception from those in sugar country.[80]

Papa Isio derived from another Philippine folk tradition, the babaylan or native priest, a holdover from prehispanic society. The religion flourished in rural, especially mountainous, areas of the western Visayas, where babaylanes performed a variety of functions including conducting services

on important occasions that propitiated natural spirits and supplying anting-anting , charms that warded off evil and harm in many forms. Babaylanism as an institution survived in part because of the shortage of Catholic priests to minister intensely to Visayans, including those who lived on or transferred to Negros. Along the central cordillera and in the southern foothills where dwelt upland farmers, victims of usurpacion, and lowland refugees from hacienda exploitation, animist priests ministered to those outside the plantation system.

From as early as the seventeenth century, some babaylanes had taken on the added role of leading peasant revolts and customarily supplied anting-anting that protected their adherents from bullets. Hence, when Isio became a babaylan in Negros, his combining of military and religious leadership fit longstanding local traditions. Authorities believed that he fled to this world after wounding or killing a Spanish hacendero. Information about his life—even about his given name—is conflicting, but the story of this murder at least indicates Isio's longstanding hatred of foreigners. In 1896 at age 50 he joined the revolution against Spain and confronted the Guardia Civil in hard-fought battles in central Negros.[81]

Isio's actions reveal that he despised colonials because they sanctioned, indeed instigated, the sugar industry with all its attendant inequities and injustices. That sugar stood as the root problem to him and his followers is evidenced in an 1899 report by General James Smith:

The Babaylanes came down to the outlying haciendas, and by specious representations that the lands would be repartitioned among the people, that machinery would no longer be permitted in the island, and that nothing but palay [rice] would henceforth be planted, succeeded in persuading the ignorant laborers of about fifty haciendas to join them and to destroy by fire the places which had given them employment.[82]

Initially his men, known collectively (and incorrectly) as babaylanes, attacked just Spanish plantations, in the belief that only native Visayans had rights to the land of Negros.

When the just-formed Negros government sought American protection in early 1899, a disillusioned Dionisio Papa directed his attacks against native planters who collaborated with the new colonial power. Isio made his targets explicit in a letter written to his next-in-command, Rufo Oyos, on May 19, 1900:

It is advisable to punish by decapitation all those who go with the Americans; but it is necessary first to ascertain the existence of the crime, and it should appear that they are real spies

of the enemy, they must be beheaded immediately without any pretext whatsoever against it [being accepted].

You, Captain Antonio and Judge Cornelio must perfectly understand what this order says; when the wealthy are Americanistas, you must seize all their money, clothing and other property belonging to them, immediately making an inventory of the property seized.[83]

From March to July 1899 Papa Isio's troops pillaged Spanish and native Negrense plantations, mainly in the sugar district from La Carlota south to Isabela, an area skirting the central mountain spine that provided raiders sanctuary from pursuing American soldiers. These attacks reduced the island's sugar output, and the U.S. Army eventually committed three battalions to the task of quelling them. Marauders under the command of Rufo Oyos also operated effectively in towns in southern Negros.

After midyear the army provided better security for planters around La Carlota, and the babaylanes moved west to Ma-ao, where they made several forays against the property of, among others, Juan Araneta. Further raids brought them to Himamaylan and Pontevedra, but as they approached the coast the insurgents enjoyed little sanctuary. Additionally, big hacenderos like Araneta, Aniceto Lacson, and Pedro Yulo employed private guards to protect their lands from destruction and their workers and themselves from capture. Finally, planters began to organize programs of registering duma'an to ensure none supported the insurgents. Isio and his troops fought their last major battle of this campaign at Bacolod in late July and suffered a loss of 170 men. From this time on he adopted more sporadic hit-and-run tactics.

Despite defections from his ranks and pursuit by American forces, Isio and his remaining troops harassed plantations and towns in western Negros on and off for eight more years. Although loyal to the cause, he received only reluctant recognition from Aguinaldo, who preferred to deal with faithless hacenderos of his own class, like Araneta. Finally, the last Republican commander, Miguel Malvar, commissioned Isio a colonel in May 1902; at the time of his surrender the latter had served the Revolution more continuously than any other officer. The Philippine Constabulary replaced the American Army in the law-and-order campaign on Negros in 1902, and newly appointed Lt. John White attacked Isio's mountain bases shortly thereafter. Oyos capitulated in April 1903, and Isio carried on the struggle alone. After a final foray against Kabankalan in 1907, Isio, now an old man, surrendered; he died in Bilibid Prison around 1908.[84]

The careers of Apong Ipe and Dionisio Papa reveal many similarities due to the common impact on Pampanga and Negros of faltering economic

conditions and revolution. Depressed markets, spreading epidemic diseases among people and farm livestock, political change, and military destruction damaged the lives of casamac and duma'an, and millenarianism offered them solace and a rallying point for organized protest. Removal of the Spanish clergy as a mechanism of social control and unwillingness on the part of Americans to enforce some of the more onerous restraints upon sugar workers allowed some opportunities to release pent up hostility to the system that subjugated them. That the two religious leaders emerged and flourished during the same time span proves no coincidence, and other regions just then experienced similar religious outbursts. Each movement, however, was shaped according to the local culture of its adherents.

Salvador moved through central Luzon in flowing robes, conducting prayer sessions and giving sermons that spoke of brotherhood and a future that included land redistribution. While Isio constructed a church at a mountain retreat where he maintained his own utopian community, his chief religious function was to issue anting-anting to his followers to ward off injury when they attacked government forces. His agents at the same time destroyed plantations and tried to induce workers to swell rebel ranks on the promise of a more equitable land settlement. Isio also demonstrated a better grasp of modern notions of secular leadership and closer touch with the larger political issues of the day. His captured letters, written in Spanish by a clerk, contained practical instructions on how to conduct a campaign of guerrilla warfare. A note of March 4, 1901, to Rufo Oyos, revealed that Isio knew that American politician William Jennings Bryan somehow featured in America's future plans in the Philippines:

I have received from Luzon an order to proceed more rapidly with my operations this month, because Bryan ordered Emilio to keep the war going vigorously until April, and he also said that if independence was not given the Philippines by that time, he, Bryan, and his followers would rise in arms against the oppressors.[85]

Nothing in Apong Ipe's biography approached such a practical or secular tone.

Despite differences in style and mode of operation, Salvador and Isio endured the long, hard struggle for Philippine independence for the same reason. The two leaders finally achieved commissions as colonels, but both faced continuous hostility from such patriots as Maximino Hizon, Liong-

son, Lacson, and Araneta. This enmity existed because those in control of the Malolos government and its provincial branches quite accurately understood that, whereas they fought for political independence, Apong Ipe and Papa Isio struggled for social and economic changes repugnant to the elite.

In his annual report for 1902 Governor Locsin wrote the following:

The society of Babaylanes (believers in superstitious and idolatrous things) is a mixture of confused socialistic principles, anarchistic instincts, and an aberration of religious and fanatic ideas. They are a crazy and criminal sect, and at the same time pray to God and preach the distribution of wealth, and looting and murder.[86]

Undoubtedly his awareness that Isio persuaded duma'an from plantations bordering the central mountains to desert their jobs to join his ranks and that the babaylanes promised to redistribute land and eliminate the sugar industry colored Locsin's judgement. That widespread fear of social revolution afflicted Negrense hacenderos emerges from the following item in a local newspaper:

The presidente of Silay, Sr. Lucio Jaime, convoked on December 17th [1899] a junta of property owners and hacenderos of the pueblo, also with the assistance of [Negros Government] Secretary of the Interior Sr. Locsin and American Lieutenant Hanagan, and they resolved to adopt effective means, not only to repel the bandits who try to claim the shelter of a political idea which they do not comprehend or know, but also to prevent the workers on the haciendas from being infected with the virus of banditry. The junta is organizing a system of vigilance of such workers so that they have to be enrolled on each hacienda, so that by this means they can be better watched.[87]

During this period planters all along the west coast offered to support American forces in suppressing Papa Isio and his movement.

Government forces on Luzon expressed similar judgements about Apong Ipe. A constabulary report in 1906 explained his movement this way:

The society purports to be a religious one, the members being given or sold crucifixes or rosaries by Salvador and using forms of worship similar to those of the Catholic Church. Salvador preaches socialistic doctrines to the believers, practices polygamy, and promises them that land and other desirable

things will be distributed among his followers when he shall have overthrown the Government and taken possession of the country himself, that there will soon be a great flood or fire that will destroy all unbelievers, and that after this purging of the country there will be a rain of gold and jewels for the faithful.[88]

Like their counterparts on Negros, establishment Capampangan placed themselves at the disposal of the Americans in bringing about the downfall of this social revolutionary.

Comparison of the practices and aims of the two religious figures proves helpful in understanding their thinking and that of their adherents; as well, such comparisons provide insight into regional cultural diversity. But what does one learn of the attitude of sugar people toward these millenarian leaders and toward their own social and economic circumstances, so affected by the impact of war and a sugar economy ? The support varied considerably and does provide evidence of differences in outlook between Capampangan and Negrenses.

In Pampanga and Negros Occidental the Philippine Revolution generated several splinter patriotic movements; moreover, simple banditry, a longstanding problem in both provinces, proliferated during these years of distress. Nevertheless, among all these antigovernment, antiestablishment activities, the organizations of Dionisio Papa and Apong Ipe attracted the most support from the indigenous population and the most attention from colonial authorities. Additionally, no other dissident movement survived nearly as long as Santa Iglesia and Isio's babaylanes.

Each leader, however, operated in a different manner and evaded arrest for separate reasons. For many years Apong Ipe moved freely about farming barrios in central Luzon, including the sugar areas of Pampanga and Tarlac, praying with his apostles and preaching love and brotherhood. What appears most remarkable about his experience is that, even in those harsh economic times, no one turned him in despite the P2,000 reward for his capture. A 1910 constabulary report observed:

Felipe Salvador, the well-known bandit leader who deserted from the Filipino insurrectionary forces years ago, and who has been lurking since in the low and swampy regions of Nueva Ecija or neighboring provinces and around Mount Arayat, showed considerable activity last spring after having been long quiet. The people of whole barrios, minor officials and all, joined him, and a large gathering was formed on Mount Arayat, apparently with the intention of attacking some

detachment of Constabulary. Strenuous efforts were put forth by many Constabulary detachments from the near-by province, but they were unable to locate or capture Salvador, who was aided practically by the whole population, though the activity of the detachments prevented his doing any harm and caused his band to dissolve and himself to again go into hiding.[89]

As he himself notes in his autobiography, so long as he stayed away from town plazas, the abode of officialdom and rich landholders, he did not face danger. Like Jesus at the Garden of Gethsemane, Salvador, to test his disciples' faith, led them to pray at the town plaza in Arayat. People of the poblacion proved fearful of approaching him, and soldiers eventually began firing at the religious group. However, among the barrio folk and the very rare hacenderos who remained sympathetic to the Revolution—loyalists like Anselmo Alejandrino (brother of Republican General Jose)—Apong Ipe received a hospitable reception to the end.[90]

Papa Isio, in contrast, depended for backing on mountain folk, people in the nonsugar foothills in the far south, and escapees from haciendas abutting the central cordillera. The greatest defections of duma'an to his ranks came between February and July 1899 when he ravaged inland sugar plantations in the La Carlota district. Defeats at Ma-ao and Bacolod essentially ended this support from sugar workers, and afterwards Isio remained at large chiefly by hiding in the inaccessible central mountains, shunning plantations and making occasional forays against towns chiefly in the south. Whereas Salvador worshipped among the lowland poor, Papa Isio avoided them.[91]

The diverse manner in which the two rebels operated accounts in part for this difference in receptivity. Apong Ipe circulated in a peaceful manner, not destroying farms where casamac earned their livelihoods. Santa Iglesia directed its raids mainly against military and police outposts, seeking weapons and other supplies. Isio, initially at least, ravaged the farms of both Spaniards and collaborating Negrenses, not necessarily discriminating between harsh and generous hacenderos. His activities thus displaced duma'an in a region where alternate forms of labor hardly existed; moreover, White indicates that the babaylanes sometimes kidnapped women from haciendas, an action certain to alienate the local population. If oppression existed on many haciendas, Dionisio Papa's methods did not necessarily provide the means of ending it.[92]

Salvador also traveled freely through sugar country because of the structure of rural communities in Pampanga. As municipalities took on a

more urban face in response to a cash-crop economy, the social division between towns proper and barrios grew. The former became the space chiefly of planters, bureaucrats, merchants, craftsmen, and laborers, while the latter communities remained the realm of tenants and small proprietors where casamac lived freer of hacendero supervision. Certainly representatives of the establishment kept in touch with more remote hamlets, but oversight remained less effective than in Negros. In the latter region, duma'an resided on plantations under the close watch of encargados and hacenderos, and this structured environment offered little opportunity for sugar workers to support without detection Papa Isio's movement.

Finally, an important part of the explanation of Apong Ipe's warm reception had to do with the great appeal of his message to Capampangan casamac. The way communities developed in Pampanga affected social attitudes, and Salvador's message of sharing blended with those rural values. Tenants dwelt near their fields, and because of the scattered pattern of landholding, aparceros contracted by several different owners might reside in the same barrio. In contrast, all those farming for a single individual might inhabit one community, especially in recently settled territory where more extensive holdings still prevailed. In any case, Pampanga's tenants mixed more freely with one another than did duma'an of Negros. The need to deal with landlords, often weekly, and to go to central markets, as well as the shorter distances between communities and better roads, generated tenant socializing.

Because of the labor pattern of Pampanga's sugar industry, share farmers forged two sets of relationships: one vertical with landholders, the other horizontal with fellow tenants and barrio denizens. A common ethnic heritage, generations of intermarriage and family ties, and a shared barrio existence provided the bases for social security in harsh times and joint action in the face of disaster. Poor farmers might depend on the rich for certain forms of economic support, but barrio mates and relatives provided the final protection against threats from nature and other outside forces. Rice tenants reciprocated planting and harvesting labor more so than did sugar tenants, but harvesting and milling cane provided some occasions for mutual help. What information casamac gained about market conditions they frequently passed among themselves, and as landlords grew increasingly distant, horizontal ties had to provide compensatory bonds of support. Such a change did not happen quickly or dramatically, and one can still discern strong patron-client bonds operating well into the twentieth century. Nevertheless, crises like those at the turn of the cen-

tury encouraged cooperation and mutual support among rural folk. Two old residents of the province spoke in interviews on this matter of provincial cooperation:

The people then loved one another more than they do now. Your neighbors would rally to your side whenever you need their help.[93]

Life is not so hard because everything is cheap and neighbors then are ready to help those who need help.[94]

Into this environment came Apong Ipe with his message of brotherhood and sharing. A recurrent theme in his autobiography is the partaking together and voluntary giving of food that becomes a metaphor for communalism, spiritual and social. In the biography Salvador also refers to several occasions when he and close friends formed a cooperative venture to cut and sell firewood to obtain their sustenance. At San Luis members of Santa Iglesia formed a successful cooperative market to which came rural folk to buy their food. Through such ventures Salvador demonstrated his theme that joint endeavor provided both physical and spiritual advantages. Concerning the appeal of this message to the farm folk of central Luzon, Ileto notes:

We can also conclude from the narrative that people were attracted to Salvador, not merely because of his individual traits, but because through their association with him certain possibilities of existence were realized. In 1904 Salvador in passing referred to the Santa Iglesia as a katipunan. In the narrative, Salvador talks about what "katipunan," or brotherhood, is all about. The minute descriptions of the bringing of gifts and food, the cooking and. sharing of meals, and the conversations; the sharing of work and earnings; the pervading atmosphere of damay [emotional sharing]—all these point to how the katipunan idea is being realized. In each of Salvador's encounters with people, "katipunan" is experienced.[95]

Sympathy for Apong Ipe and his message of both prayer and communality encouraged Capampangan to harbor this religious rebel in their midst for years, despite the antagonism of the landholding elite and the government. No similar situation existed in Negros, where duma'an proved unwilling and perhaps unable to hide the babaylanes from the purview of hacenderos. Dionisio Papa did have a priestly function and a social message: gain political independence and dismantle the sugar industry. However, if he possessed a vision of a better society he did not make

it easily available, because he did not preach and pray among sugar hands. His only writings contained orders and threats, while his personally established home community lay hidden in inaccessible and mysterious mountain reaches. Dionisio Papa lacked the means to communicate with the great bulk of Negrense poor.

Even with a well-articulated social message, however, it seems unlikely that Papa Isio would have found a sirnpatico response on haciendas, for duma'an had not developed the sense of community that existed in Pampanga's tenant barrios. Whereas the latter region began with communities upon which the sugar industry was grafted, in Negros the social units were a creation of that industry. The duma'an inhabited isolated plantations where they were closely watched. They had limited occasions for concerted action and for socializing with workers on other haciendas. They might well have practiced the everyday forms of small resistance adopted by the poor all over Southeast Asia; the hacenderos did, after all, carry guns when they made their rounds of their estates.[96] Such acts of defiance, however, would have gone largely unnoticed by most, since they were carried out subtly and individually, for the duma'an would scarcely have acted overtly and risked the wrath of the plantation bosses. Even sacadas had more freedom to speak out in concert than did workers on haciendas. This inability to function collectively reduced the duma'ans' ability to confront inequity and to express dissatisfaction with it.

Of social life on plantations in general, Beckford has written:

Within [the] plantation community, interpersonal relations reflect the authority structure of the plantation itself. In every aspect of life a strong authoritarian tradition can be observed. Any one with the slightest degree of power over others exercises this power in a characteristic[ally] exploitlve authoritarian manner, and attitudes toward work clearly reflect the plantation influence. Overseer types never do manual work which is degrading to their social dignity and laborers consistently devise ways and means of getting pay without actually doing the work it is simply a case of always trying to beat the system. On the whole the plantation has a demoralizing influence on the community. It destroys or discourages the institution of family and so undermines the entire social fabric. It engenders an ethos of dependence and patronage and so deprives people of dignity, security, and self-respect. And it impedes the material, social, and spiritual advance of the majority of people.[97]

While this description applies most aptly to Beckford's own Caribbean world, its claims about society appear to fit the situation in Negros as well.

Sugar workers recently drawn from several surrounding islands and diverse language groups and living in isolated, atomistic units scarcely constituted a population likely to share a common notion of the ideal community. Papa Isio's social vision probably had little chance of being well received or even comprehended by those to whom he most needed to appeal.

Thus, differences in expression of resentment and sentiments toward social protest in the statements of casamac and duma'an seem to find corroboration in the responses of each to local rebels. The two regions had grown along different lines, and not surprisingly, their work forces had developed disparate social attitudes that reacted to events in separate ways. In the broadest terms Pampanga's spirit of community and the Negrense notion of individuality emerge as the two major social legacies of the frontier era, ideals that would carry over into the years when centrals dominated the landscape.

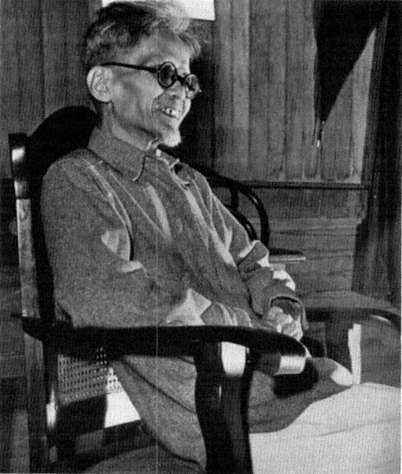

Plate 1.

Pedro Abad Santos. From Florence Horn, Orphans of the Pacific: The

Philippines (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1941), photo section.

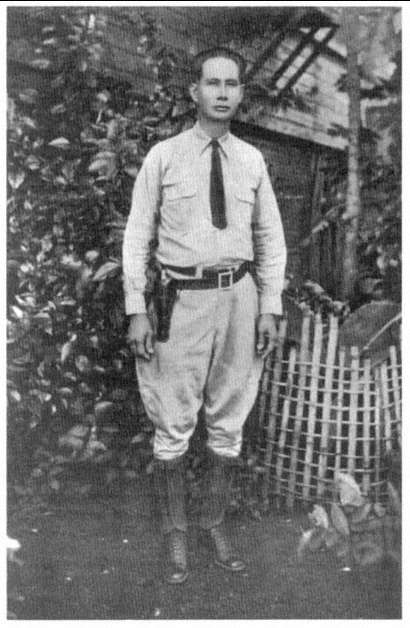

Plate 2.

Successful Negros Hacendero Yee On. From Sugar News 14 (1933): 92.

Plate 3.

Cane Cutter. From Sugar News 1, no. 15 (1920): 55.

Plate 4.

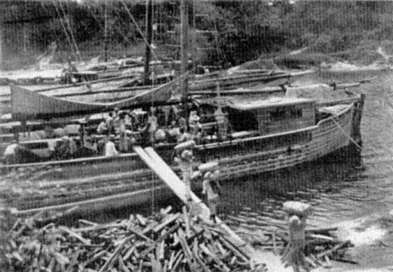

Loading Sugar on Lorchas in Negros. From G. E. Nesom and Herbert S.

Walker, Handbook on the Sugar Industry of the Philippine Islands

(Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1912), pt. 2, plate 9, fig. 2.

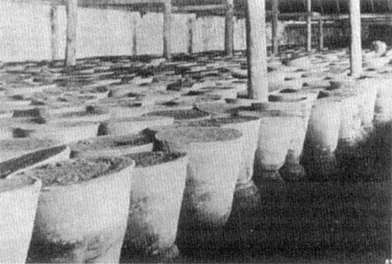

Plate 5.

Pilon Sugar in Storage. From Sugar News 1, no. 9 (1920): 19.

Plate 6.

Sugar Mill in Action. From Nesom and Walker, Handbook , pt. 2, plate

6, fig. 2.

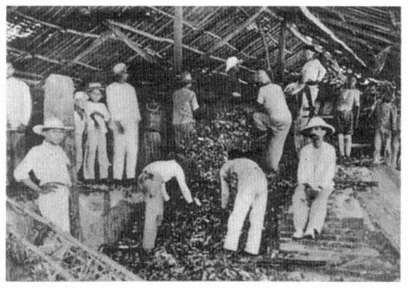

Plate 7.

Furrowing Out Rows and Planting Cane Points. From Nesom and Walker,

Handbook , pt. 1, plate 11, fig. 1.

Plate 8.

Loading Railroad Cars with Cane. From Sugar News 1, no. 14 (1920):20.

Plate 9.

Cascos of Sugar at the Manila Wharves. From Frederic H. Sawyer, The

Inhabitants of the Philippines (London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1900), p. 161.

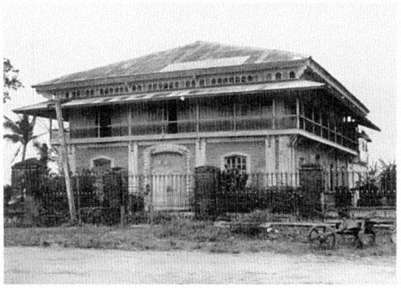

Plate 10.

Aniceto Lacson House, Talisay, Negros Occidental. From the Museum

of History and Iconography Archive, Ayala Museum, Makati, Metro Manila.

Plate 11.

President and Mrs. Quezon at Their Pampanga Farm. From Manuel

L. Quezon, The Good Fight (New York: Appleton-Century, 1946), p. 198.

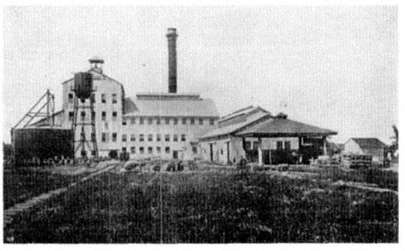

Plate 12.

Central Azucarera de La Carlota. From Sugar News 1 , no. 10 (1920):

frontispiece.