Chapter Eight

Melody, Meter, and the Musical Medium

The theatre, and especially the operatic or musical theatre, possesses a complex system of communication, combining in one integrated medium a number of separate subsystems. The union in theatre of various visual and auditory media was intimated by Bharata in the Natyasastra , when he described how Brahma borrowed the best element of each of the four Vedas to fabricate his invention. To Bharata's pathya (verbal recitation), gita (music and song), abhinaya (gestures and movement), and rasa (sentiments and emotions) we might add other systems of theatrical communication: costumes and makeup, curtains and scenery, uses of space, props, and sound effects. The interplay of these systems creates a sensor), bombardment, enriching levels of meaning and contributing both to theatre's distinctive identity and to its effect on an audience. In the vocabulary of semiotics, we can say that theatre engages the spectator by means of a "surplus of signifiers."[1] From this profusion of coded messages, we isolate different symbol sets or systems.

Even a preliminary overview of the traditional theatres of India suggests that these multiple systems of communication are ordered into hierarchies that vary from theatre to theatre. Abstract masks and song-less speechless mime dominate the Seraikella Chhau of Bihar, while the shifting use of municipal space flavors the grand Ram Lila at Ramnagar in Uttar Pradesh. In the Kuchipudi theatre (Andhra Pradesh) and the Bhagavatamela (Tanjore district, Tamilnadu), elaborate dance and styl-

ized hand gestures prevail. Spectacular headdresses, costumes, and color-coded makeup distinguish both the Kathakali theatre of Kerala and the Yakshagana of Karnataka.

In Nautanki, I contend, it is the music that constitutes the most important nonverbal system of communication, ranking above dance, acting techniques, or visual symbolism as a signifier of meaning. Further, the musical system of Nautanki separates it from performance traditions that share its narratives, serving as a determinant of genre. A Nautanki play based on the Alha story can be identified by its own music, different from that of an Alha epic recitation; the music similarly gives away a Nautanki performance occurring at the edges of a Ras Lila festival. Music in its alliance with poetic meter is the principal source of Nautanki's aesthetic impact on its audience. The sound of Nautanki resides in the hearer's consciousness, giving melody and rhythm to remembered snatches of words, aiding in their acquisition and retention. Musical and metrical structures weave through Nautanki's treasury of hundreds of tales, conferring a unity on an outsized body of folklore. Furthermore, as Nautanki has formed and reformed in the last hundred or more years, it is the music that has most clearly registered the radical shift in the relations between folk theatre and society.

This chapter treats first the more obvious features of Nautanki's music: its distinctive instruments and vocal idiom, the manner in which singing and drumming combine, and the broad divisions of the sung text. The intention is to show that theatrical music constitutes a distinct category within the broader field of the Hindustani (North Indian) musical system, and that without being a classical style it incorporates certain features of the classical system and occupies a separate position comparable to folk music, popular music, or film music.[2] Proceeding from this is a more detailed examination of musical organization, including metrical and melodic analysis of the principal couplet and stanza forms and the variants and rhythmic patterns associated with them. A number of notational examples, possibly of greater interest to the musicologist than the lay reader, accompany this discussion. The musical analysis here supports the hypothesis that in theatre, as in recitational music forms, melodic construction is to a great extent determined by metrical composition within the larger parameters of regional style, historical period, and performative genre. The final section discusses the social, economic, and technological impacts on the traditional theatres, with reference to irrevocable changes in the structure and function of

their music. Over the last hundred years, the context for Nautanki music has altered from patron-supported open competition to production of a commercially-oriented commodity. Remnants of the historically discrete musical styles now coexist. The older Hathras style, to the extent that it survives, has maintained the improvised character and agonistic ethos of the traditional art, while in the Kanpur style and on recorded disks and cassettes, the music has become standardized, melodically and metrically simplified, and commodified to meet very different market conditions and listener expectations.

Music for the Outdoor Stage

We approach the overall character of Nautanki music through consideration of the material culture of the folk stage and its requirements for communication. Until very recently, shows were performed outdoors mainly at night—on temporarily erected stages or platforms, on porches in market areas, in courtyards, or in tented arenas at fairs. Three sides of the stage were generally open to the public, and large crowds gathered, as many as ten thousand spectators by some accounts. In the absence of electricity and amplification, the foremost demand was that the music and voices of actor-singers be audible. Hearing was even more important than seeing, because sightlines would have been obstructed for many in the throng. Probably for these reasons, Nautanki like other traditional theatres favored instruments with piercing timbres. The core of the Nautanki ensemble consisted of a high-pitched reed instrument, such as the indigenous shahnai , a relative of the oboe, or later the imported clarinet. Rhythm was maintained by the booming nagara , a kettledrum played with sticks, supported by a second higher-pitched nagara or a dholak , a popular double-faced hand-drum (figs. 19 and 20).

The shahnai and nagara were traditionally part of a processional ensemble known as the naubat , whose role was to lead military parades and announce the watches of the day in royal palaces.[3] As used in Nautanki theatre, the naubat served first in its original function as marching band. It announced the show, playing in procession in the town or village beforehand and at the commencement of the evening's entertainment while the audience was assembling. Second, it served as "orchestra," accompanying the singers during the drama. Even today, the loud, rapid-fire drumming of the nagara sums up the heroic and martial character of Nautanki and serves as its ubiquitous trademark.[4] The thin piping tone of the shahnai , by contrast, alerts the listener to

Fig. 19.

Title page of Sangit odaki ka by Mitthan Lal and Chunni Lal

(Delhi, 1932). Musical instruments (left to right): sarangi , harmonium,

dholak . By permission of the British Library.

Fig. 20.

Musical ensemble from Amar simh rathor . Musical instruments (left to right): nagara ,

sarangi, dholak . By permission of the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

the romantic and feminine side of the theatre, signaling in particular the flirtatious games (nakh re ) of the dancer-actress.

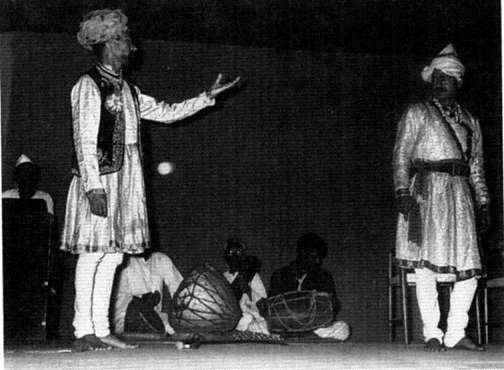

As with the instruments, the singing of the actors had to be very loud to project to the crowds. To reach this goal they cultivated an open-throated, forceful vocal style, dwelling primarily in the upper register (fig. 21). The recitatives of Nautanki typically begin on the tonic in the upper octave and wind their way gradually downward to close on the lower tonic. The melodic "shadow" provided by the accompanying instrument anticipates the beginning, leading up to the high tonic at the end of the preceding phrase. Holding the breath on high notes is considered a feat of virtuosity, earning outbursts of praise from the audience.[5] At climactic moments, the singer conveys dramatic bursts of emotion by exploring the uppermost notes in his or her register; they are the ones most likely to cut through the ambient noise in the performance area and make an impact on the listeners. Male singers, especially female impersonators, may employ a falsetto voice quality. The most virtuosic Nautanki singing is characterized by stirring florid passages charged with an almost erotic excess, an operatic overflow of passion. Rapid ornamental turns, melismatic ascents and descents, and other flourishes are used to adorn the vocal line and are much prized. The vibrato effects common to choral Sufi singing (qavvali ) and the folk singing of Haryana, Rajasthan, or the Punjab are usually absent.

The particular musical interaction that occurs between the singer-actors and the instrumental ensemble in Nautanki reflects the demands of communication in an outdoor setting. Three types of poetic discourse characterize Nautanki's sung text: these are narrative, dialogue, and lyric. Prose passages may also be introduced into the verbal texture but are never sung. Narrative and dialogue carry the forward movement of the story and must be clearly enunciated for audience comprehension. Perhaps for this reason, overlap between singers and instrumentalists in these sections is reduced to a minimum. The poetic lines are delivered one by one in recitative style, with percussion and the less audible melodic instruments entering after each line is concluded. These passages produce an antiphonal structure between the singer and the instrumental ensemble, the two alternating and taking turns throughout. During the recitative, the singer's meter does not follow the framework of tala (rhythm cycle), as it would in Hindustani vocal music. He or she spontaneously matches the short and long weights of the metered line to the standard contours of the appropriate melody or freely improvises on an end rhyme using melismatic ornamentation. As soon as the singer fin-

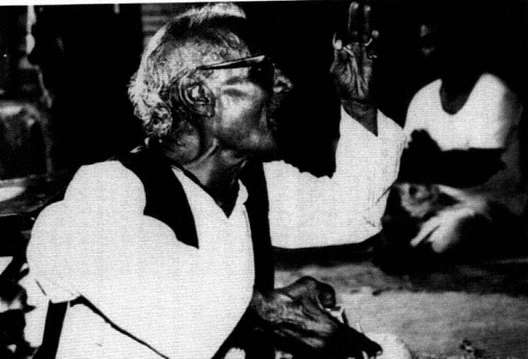

Fig. 21.

Singers in dialogue, from Amar simh rathor . By permission of the

Sangeet Natak Akademi.

ishes the line, and usually beginning with its last note, the percussion enters and plays a pattern in a regular rhythm cycle, ordinarily eight or sixteen beats. Melodic instruments such as shahnai , flute, clarinet, sarangi , or harmonium may shadow the singer during the recitative, lagging behind slightly and imitating the sung line. Customarily they re-

peat a refrain melody (comparable to the lahara of classical music) during the percussion solos. This antiphonal style contrasts with the style of the lyric passages, which exhibits simultaneous accompaniment (sath-sangat ). This style is found in the song forms of Nautanki such as dadra, thumri , and ghazal .

These three levels of poetic discourse and their differing modes of musical realization occur in the opening excerpt from Sultana daku , a commercial Nautanki performance recorded on a 45 rpm Odeon disk (ex. 1).

A narrative passage opens the story, several verses in which the narrator (kavi ) describes the hero's character and fame (lines 1-6). A dialogue follows between Sultana and his guard (sipahi ), an episode that shows Sultana's character, in this case his merciless discipline (ll. 7-14). Here the speeches are short, and the passage is marked by rapid alternation between speakers. There follows another dialogue in which the villains are introduced, namely the notorious Mr. Young and one of his minions (pulis ) (ll. 15-24). The humorous character of the passage lies in the British officer's imperfect success at speaking Hindi, indicated by the artificial retroflection of all dental consonants. In these three sections the singers are melodically shadowed by the clarinet, against the continuous drone and support of the harmonium. At the points indicated by an asterisk, the nagara joins the clarinet to create an antiphonal response to each completed line. The melodies employed are all based on a diatonic mode of the Kalyan-Bilaval-Khamaj type in Hindustani classical music, that is, a major scale occasionally touching the flatted seventh in descent and the raised fourth in ascent.

A transition is announced by a flourish on the wind instruments and a change of mode, at which point a narrative doha specifies the scene switch to Sultana's private quarters (ll. 25-26). The text moves into a lyrical section based loosely on conventions of love poetry found in Hindi and Urdu literature. The beloved woman (Phulkumvar) speaks in a Hindi idiom, suggesting a dadra or thumri song form (ll. 27-28). After the vocal introduction of line 27, the instruments including nagara accompany the singer in the lyrical fashion of sath-sangat to the end of the song. Sultana, the lover, replies using the diction of the Urdu ghazal (note words like tassavur, ulfat, judai , and khudai[*] ) (ll. 29-32). Both songs employ a minor mode that contrasts with the previous sections; in terms of Hindustani music, the mode is comparable to Bhairavi or Asavari ragas with their flatted second, third, sixth, and seventh tones.

Although this passage is extremely compressed, it illustrates the episodic structure of the Nautanki text and, wedded to that structure, a

EXAMPLE 1. LEVELS OF POETIC DISCOURSE AND MUSICAL ORGANIZATION | |||

KAVI: | suna sabhom ne hoiga sultana ka nam, | ||

Everyone must have heard the name of Sultana | |||

sher-e-nar daku bara guzara khas-o-am[*] . (*) | |||

Like a lion, this dacoit was famed among rich and poor . | |||

madadgar rahta garibom[*] ka har ham, (twice, first time *) | |||

He succored the poor at every chance . | |||

mitata tha bevaom ka dukh alam g am. (*) | |||

He removed the great grief of widows . | |||

amirom ka dhan lutta tha hamesha, | 5 | ||

He always stole the wealth of the rich ; | |||

garibom[*] ke khatir[*] banaya tha pesha. (*) | |||

He pursued his occupation for the sake of the poor . | |||

SULTANA: | chhora pahra mera tal kar ke hukam, | ||

Leaving your duty and disobeying my order , | |||

nek sagar ke pine ko aya yaham. | |||

You have come here to drink an ocean . | |||

SIPAHI: | is ghari maf meri khata[*] kijiye, | ||

Please forgive my error this time . | |||

bhul beshak hui, bakh shiye meri jam. (*) | 10 | ||

I made a mistake of course. Please grant me my life . | |||

SULTANA: | maf karta khatavar[*] ko maim nahim, | ||

I don't forgive those who make mistakes | |||

bhej deta hum ik pal mem mulk-e-adam. | |||

I'll send you to the netherworld in an instant . | |||

zyada batom ka sunne ka adi nahim, | |||

I'm not used to listening to much talk . | |||

ek goli mem karta hum qissa kh atam. (shoots him ) (*) | |||

I'll end the story in one shot . | |||

PULIS: | bara hai sultana hushiyar | 15 | |

Sultana is very clever . | |||

pulis us se jati hai har. (*) | |||

The police are defeated by him . | |||

giraftar karna use yang sahab na khel | |||

It's no game to arrest him, Mr. Young . | |||

nikal bhagta har tarah leve jitana gher. | |||

He escapes somehow no matter how you surround him . | |||

hai mushkil us se pana par, | |||

It's difficult to outwit him. | |||

bara hai sultana hushiyar. (*) | 20 | ||

Sultana is very clever. | |||

YANG SAHAB: | vel tum mujh ko janta, hum kitna chalak, | ||

Well, you know how smart I am . | |||

EXAMPLE 1. (continued ) | ||||

barom barom ko ekdam kar deta hum khak[*] . | ||||

I reduce the biggest men to dust in an instant . | ||||

mita dalumga us ko mar, | ||||

I'll kill him, wipe him out . | ||||

bara hai sultana hushiyar.(*) | ||||

Sultana is very clever . | ||||

KAVI: | jab jab fursat dekhta sultana ai yar, | 25 | ||

Whenever Sultana had some free time, my friend , | ||||

phulkumvar ke sath mem karta mauj bahar. (*) | ||||

He enjoyed himself with Phulkumvar [his mistress] . | ||||

PHULKUMVER: | rahe ho balama kaham sari rain. (twice, second time *) | |||

Where have you been all night, my beloved ? | ||||

aye kaham se mere dilara, mad bhar jage kaham ke nain, | ||||

Where have you come from, my darling? Where did you get these wakeful, intoxicated eyes? | ||||

rahe ho balama kaham sari rain. | ||||

Where have you been all night, my beloved ? | ||||

SULTANA: | tera hi tassavur rahta hai, tu dil mem samai rahti hai. (twice, | |||

I'm always thinking of you. You are in my heart constantly . | ||||

maim ratom ko jaga karta hum, jab soti khudai[*] rahti hai. (*) | 30 | |||

I lie awake at night when the rest of creation sleeps . | ||||

teri surat, teri chahat, teri ulfat haim pas sabhi, | ||||

Your face, desire for you, longing for you—all are near | ||||

har chiz pas mem hote hue, kyom tujh se judai rahti hai? (*) | ||||

When everything is near at hand, why am I separated still from you? | ||||

(Sultana daku , Odeon EP recorded disk) | ||||

* Instrumental interlude (melody and percussion) | ||||

continuous musical texture that supplies linkages and changes of scene and character. We see here as well that narrative, dialogue, and sections of song and dance alternate easily in a format that allows almost infinite extension in time. Each section engages different qualities of audience attention: the narrative passages move over events the most quickly, the dialogue brings into focus the dramatic interaction between characters; in the song and dance the action virtually stops. To the Western viewer bringing an Aristotelian concept of theatre, the song-and-dance por-

tions appear to digress from the plot and distract the viewer, but the' Indian audience does not rank the narrative and dialogue elements above song and dance. The song and dance in fact more often attract than distract, and viewers place a high entertainment value on them.[6]

Over the course of a performance the musical character of the recitatives varies markedly, first by alternating between contrasting metrical units associated with different modes, and second by gradually introducing a number of new modes, often in conjunction with action-related moods. These melodies in their diversity resemble some of the well-known ragas or scalar types of Hindustani classical music, for example, Yaman, Bilaval, Desh, Bhairavi, Kalingara, and Asavari. In addition, the lyric forms (popular songs) draw on the light classical and folk repertoires and, depending on the singer's knowledge, may develop scale patterns typical of the "mixed" ragas, particularly Khamaj, Pilu, Pahari, and Kafi. The question then arises of the relationship of Nautanki music to the Hindustani system. If the Hindustani system provides the substratum for theatrical music as for much folk music in this region, to what extent can we consider Nautanki music "classical"?

Querying present-day Nautanki singers about their musical training reveals that little direct transmission of the theoretical principles of Hindustani music occurs, at least through the channel of formal disciple-ship. Among currently performing Nautanki artists, very few have had extensive instruction in vocal music, and few know the elaborate nomenclature of raga and tala that demarcates the classical canon. Several performers mentioned a period of study with a guru or ustad as part of their life story. Giriraj Prasad emphasized his own classical training, as several directors who had worked with him also noted. In an interview recorded by the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi, he summoned the names of a dozen ragas that he claimed to sing during his Nautanki performances, but he erroneously attributed a Khamaj-type chaubola he was demonstrating to Rag Malkauns, possibly because the verbal text also contains the heroic sentiment he was being asked to illustrate. Similarly, the nagara player Atthan Khan performed as requested four or five talas ; asked to play Dipchandi, a relatively common rhythm cycle of fourteen beats, he did not do so correctly. These artists' assertions regarding their classical training may be as dubious as Malika Begam's alleged knowledge of the South Indian dance form, Bharata Natyam, which she listed in the same breath with her qualifications in "filmi dance, Kathak, and the twist."

Nonetheless, we should neither discount the informal knowledge of

the artists nor the structural similarities between Nautanki's music and Hindustani music. Perhaps musicians and singers of Nautanki are able to execute in practice what they are unable to discuss or name in theory. Although Nautanki music does not conform to the raga system in its full form, it clearly employs a number of distinctive modes that are similar to classical Hindustani ragas as well as the mixed modes of light classical music. Melodies have contours based on stepwise descent and on vakra movements (skipping intermediate tones); they feature parallelisms between tetrachords and other types of patterning common to ragas. Structural features of classical composition found in Nautanki include the sthayi-antara structure used in the lighter songs, rhythm cycles such as tintal for percussion interludes, and the frequent three-part rhythmic cadence (tihai ).[7] In these and other instances, Nautanki music manifests its closeness to Hindustani classical music while maintaining a distinct character through its own specific musical grammar.

The musical dimensions of Nautanki as a traditional outdoor theatre—its loudness, emphasis on drumming, high vocal register, antiphonal texture, mixture of recitation and song forms, and relatedness to the classical idiom it shares with a number of other South Asian theatrical traditions. The ensemble of aerophones (especially reeds and brass) and drums is found in Gujarat in the bhungal (a five-foot-long copper pipe) and nagara of Bhavai; in Tamilnadu in Terukkuttu's kurukuzhal (small pipe similar to the nagasvaram ) and maddalam ; in the pipes and drums (maddale or mridanga ) of Yakshagana theatre, as well as in the more urbanized forms that use flutes, clarinets, trumpets, and nowadays (everywhere) the harmonium. High-pitched singing is common to most of the traditional theatres. The Jatra of Bengal always began on a high note,[8] and in Tamasha the higher the pitch, the more skillful the artists are considered to be.[9] The bhagavatha or lead singer of Yakshagana inspired Gargi to write: "He starts at a high pitch and raises his voice as if he were loudly calling, challenging, wailing. His high-crested voice constructs a many-pinnacled fortress."[10] The available accounts confirm the presence of multiple layers of recitation, dialogue, and song in all these theatres, as well as the predominance of question-response structures between actors and musicians.[11] Classical ragas similarly occur in the music of folk theatre throughout India, ranging from the mixed repertoire of 150 Hindustani, Karnatak, and regional Kannada ragas found in the Yakshagana theatre, to the smaller selection of favored ragas and light melodies associated with Bhavai, Jatra, Khyal, and Ankiya Nat in the north.[12]

We need to know more about the musical textures of South Asian theatres, and we must compare the function of music with other signifying systems across regions and genres. When more specific information becomes available, we may be able to construct a continuum of the traditional theatres to compare their musical components. On one end, we might provisionally place theatres like Chhau or Kathakali where dance and mime are the actor's concern and singing is the function of a specialist offstage. At the other end, we might position the singer-actors of Nautanki or Terukkuttu who carry the burden of continuous singing.

What consequences do various musical requirements have on the other signifying systems present in theatre? In Nautanki, the amount of movement, gesture language, miming of emotions, and acting is small compared to other traditional theatres. Is this true for other music-dominated genres? How does the participation of actor-singers shift when other modes of communication become more important? These are areas in which comparative research could tell us much about the role of music as a system of communication within the theatre in South Asia.

Metrical Patterns and Melodic Contours

Although Nautanki music resembles other South Asian theatrical music in general ways, it also possesses a distinctive blueprint: a configuration in sound that immediately labels this genre Nautanki, even when compared to neighboring theatres such as Haryanvi Sang or Rajasthani Khyal. This blueprint is the music used for the ten-line stanza known as doha-chaubola-daur , the basic building block of Nautanki composition. It is significant that this identifying unit issues from the narrative level of the text, not the lyric. Nautanki performance freely borrows lyric genres from various sources and incorporates them according to current fashion and the taste of the actors and audience. In older texts we find Hindi folk songs and semiclassical genres such as dadra, savan, holi, thumri , and mand , as well as the Urdu sher, ghazal, qavvali, masnavi , and so forth. Nowadays Bombay film tunes (filmi git or gane ) or film-influenced versions of the above genres tend to predominate. Popular songs are not exclusive to Nautanki; they turn up in many performance contexts classified as "folk." Film-based musical quotations may lend a performance verve and status, but they do not distinguish Nautanki as the old meters doha and chaubola do.

Doha is a reputable Hindi meter with a long history. The doha-chaubola of Svang and Nautanki may be an outgrowth of the established

EXAMPLE 2. METRICAL STRUCTURE OF THE HINDI doha | ||||

(13) | (11) | |||

|  | |||

(13) | (11) | |||

|  | |||

(Sultana daku, , Odeon EP recorded disk) | ||||

Scansion code: The symbol | ||||

doha-chaupai pattern of medieval Hindi narrative verse. In any case, nineteenth-century Sangit texts reveal that the doha-chaubola alone dominates Svang composition from about 1850 to 1890. Beginning in the 1890s the six lines of doha-chaubola commonly add on an asymmetrical quatrain called daur to form a ten-line unit; in the Hathras texts this becomes the standard.[13]Doha, chaubola , and daur are scanned according to rules of Hindi prosody, by which every syllable bears either a short (laghu ) or long (guru ) weight or measure, indicated by the symbols

In parallel fashion, the meter chaubola consists of four lines of 28 measures each, ordinarily divided 14 + 14 and rhyming b b b b . The final two syllables of each line are generally weighted - -, and the rhyme occurs on the penultimate syllable (a "feminine" rhyme). The doha and chaubola are often interlinked, the final half-line of the doha being repeated at the beginning of the chaubola . The linkage of doha to chaubola is also one of sense; the chaubola often repeats and expands on the content of the doha . Characteristically following the chaubola is a daur , a Hindi meter of four lines, 13 + 13 + 13 + 28 measures, rhyming c c d d , again on two syllables. Doha-chaubola-daur forms the speech of one character or a descriptive passage by the narrator (kavi ). The daur often

EXAMPLE 3. STRUCTURE OF doha-chaubola-daur | |

Doha : two lines of 24 measures, 13 + 11 each; rhymes a a | |

Chaubola : four lines usually of 28 measures, 14 + 14 each, rhymes b b b b ; interlinks with doha , beginning with repetition of final half-line of doha | |

Daur : four lines, 13 + 13 + 13 +28 measures, rhymes c c d d | |

doha | Elizabeth dvitiya [the second] empress, good gracious strong, |

chaubola | May you live long long, rule beneficent continue, |

daur | Your gracious Majesty, |

Amar simh rathor (Hathras: Shyam Press, 1981). The mangalacharanappears in the text in Devanagari, with the English sounds rendered by their nearest Hindi equivalents. Instead of transliterating it, I restore the words to their standard English spellings without altering the grammar of the passage. | |

moves the action forward by forming an address to another character. Formally it provides for closure by returning to a final line of 28 measures, the same as the chaubola .

Examples 3 and 4 illustrate these meters. The first is an homage (mangalacharan ) to Queen Elizabeth in the English language; the excerpt is from an actual Nautanki text printed in Devanagari script. The overall structure of the ten-line stanza is readily visible here, freed from the technical details of Hindi scansion. Additionally, this passage shows how quickly Nautanki performers adapted to changing patterns of patronage. The choice of English when seeking blessings from the British parallels the use of Sanskrit in invocations addressed to the Hindu deity Narayana, or Perso-Arabic for those uttered to the Islamic god Khuda[*] .. One should, after all, address the gods in their own language. Example 4 is from the All-India Radio version of the Nautanki Rani lakshmibai . In this telling of the story of the famous warrior queen, the dacoits are at first the villains, from whom the people require the Rani of Jhansi's protection. Later Sagar Singh, a dacoit leader, becomes an ally of the Rani in her fight against the British.

Whereas the doha-chaubola-daur carries the weight of narration in

EXAMPLE 4. METRICAL STRUCTURE OF doha-chaubola-daur | |||

doha | (13) | (11) | |

|  | ||

(13) | (11) | ||

|  | ||

chaubola | (14) | (14) | |

|  | ||

(14) | (14) | ||

|  | ||

(14) | (14) | ||

|  | ||

(14) | (14) | ||

|  | ||

daur | (13) | ||

| |||

(13) | |||

| |||

(13) | |||

| |||

| |||

Khuda Bakhsh became injured, and all the dacoits fled . | |||

The news of this immediately reached the kingdom of Jhansi . | |||

[The news of this] immediately [reached] the kingdom of Jhansi, and the queen summoned her army . | |||

When she heard the message, she didn't delay an instant . | |||

She brought her female companion, who rode with her at the head of the army . | |||

In Barua Sagar, there was an uproar as the queen arrived from Jhansi . | |||

The enthusiasm and delight [of the people] were unprecedented. The queen loved everyone . | |||

She met with the public and heard from Khuda Bakhsh the story of Sagar Singh . | |||

(Rani lakshmibai , AIR-Mathura recording) | |||

Nautanki, a shorter stanza useful for dialogue, known as bahr-e-tavil , was introduced around 1910. This meter is based on Urdu prosody rather than Hindi, indicating the mixed linguistic heritage of this region and the presence of both Hindi and Urdu prototypes in the oral stratum

EXAMPLE 5. METRICAL STRUCTURE OF bahr-e-tavil |

Bahr-e-tavil : two rhyming lines of 24 stresses (not matras ) each, according to rules of Urdu scansion, that commonly occur in feet of long-short-long |

|

Flexibility exists in determining the short and long stress of syllables, especially for grammatical endings signifying gender and case; ambiguous syllables carry the symbol  |

|

I request this of you, oh moonfaced one: having given your heart, do not withdraw it . |

Never be unfaithful, no matter what, and if you will love, fulfill your promise . |

(Laila majnun [Hathras: Shyam Press, 1981]) |

from which Nautanki arose. It can be described as two rhyming lines of 24 stresses each (according to rules of Urdu scansion), or four lines of 12 stresses each, arranged generally in feet of long-short-long.[15] The two long lines may be divided between two speakers to create a brisker pace of dialogue. Illustrating bahr-e-tavil is example 5.

Other common meters include bir chhand , also known as alha chhand , because of its use in the Hindi oral epic, the Alha. Bir chhand , as used in Nautanki, consists of two rhyming lines of 16+15 measures each (ex. 6). Bir chhand is employed primarily for narration, as are several varieties of lavani such as lavani langari, lavani chhoti,lavani bari , and others. Additional forms favored for dialogue are shair (or sher), qavvali , and even ghazal , which are essentially couplets or quatrains in various common Urdu meters. As occurring in Nautanki, these terms appear to be somewhat interchangeable and may denote melodic rather than metrical units.

The foregoing description of the metrical patterning of the Nautanki text is essential to an understanding of the musical dimension of performance, because music closely follows meter in this tradition. This is true in two primary senses. First of all, the meter of a passage reliably predicts the tune or type of tune to which it will be sung, within the con-

EXAMPLE 6. METRICAL STRUCTURE OF bir chhand |

Bir chhand (or alha chhand ): a Hindi meter of two rhyming lines of 16 + 15 measures each |

|

He allowed no one to live who might commit a wrongdoing . |

Consider the defiance of such a tyrant! He avoided no man . |

(Sultana daku [Hathras: Shyam Press, 1977]) |

ventional framework of the genre and the particular school or style of performance. Notably, the melodic rendering of the two most prevalent meter clusters, doha-chaubola-daur and bahr-e-tavil , is consistent in essentials over a wide range of performance examples collected. (Important differences between the Hathras, Kanpur, and more recent styles do emerge. The discussion here focuses on the Hathras singing style, and the next section treats developments in Kanpur and elsewhere.) Their divergent melodies place these two meter groups in sharp contrast. Doha, chaubola , and daur almost always feature a tune based on the major scale, whereas the melody of bahr-e-tavil uses a mode laden with minor tones, similar to the Bhairavi of Hindustani music. Because of this modal contrast, the audience perceives the shift from a narrative portion of the text (characteristically introduced by a doha ) to a dialogue passage (typically composed in bahr-e-tavil ). Furthermore, the contrast gives the performance a sufficient degree of melodic diversity. Both meter types are sung in the antiphonal manner, alternating between vocal and instrumental lines.

Second, music follows meter in the specific way in which the standard tune matches the words. The doha-chaubola-daur and Hindi meters in general are sung in a recitative style corresponding to the weight of syllables, with long syllables receiving roughly twice the duration of short syllables. The rhythmic details of musical execution therefore vary from one line to another, insofar as the arrangement of long and short syllables varies. The meter also prescribes particular resting points where musical elaboration may occur. Syllables at the ends of lines or before

caesuras are often elongated. Beyond the demands of the meter, moreover, Nautanki singing favors an element of interpretive rubato that allows for individual expression. A passage may be slowed down for emphasis or speeded up to usher in the percussion response, usually set at a slightly faster tempo. In the examples with musical notation included here, I generally transcribe the time value of notes in accordance with their metrical weight, although the values attached to notes in ornamental passages are usually arbitrary. For ease of reading and comparison of modes, I transpose all melodies to a tonic of middle C. Similarly, I use the treble clef throughout, although the majority of examples are of male singers whose voices are pitched somewhat lower.

In example 7, the recitatives of the doha-chaubola-daur from Rani lakshmibai (the metrical structure of which is in ex. 4) are transcribed to illustrate the melodies most frequently associated with these meters. This performance was produced for All-India Radio and was broadcast from its Mathura station in 1981. The singers and musicians come from the Braj area in western Uttar Pradesh and belong to the surviving performance traditions associated with the Hathras style.[16]

The doha begins in characteristic fashion on the high tonic, and after dwelling there for the first half-line, focuses on the fifth and then, in anticipation, moves down to the lower tonic at the end of the first line. In the second line the tune rises again to the high tonic at the caesura and returns to the lower at its completion. A drum interlude of eight bars follows, commencing at the utterance of the final syllable of the doha . (Details of the drumming patterns will be discussed below.) The chaubola is similarly structured in two-line pairs. The first line of the chaubola echoes the opening of the doha , beginning again on the high tonic. The second line carries the melody down from the high tonic to the lower in almost a purely stepwise descent, introducing a flatted seventh. After an eight-bar drum solo (not notated), the third line dwells on the fourth of the octave and moves down to the tonic after touching the fifth. The fourth line is a repeat of the second, essentially a descending scale with flatted seventh. The chaubola concludes with a single drum beat, perhaps an indication of a solo that was edited out. The daur in its own fashion imitates the chaubola ; the first line focuses on the high tonic and its leading tone, the major seventh, and the second line introduces the flatted seventh. The third line emphasizes the fourth tone of the scale, and the last line utilizes the descent pattern and melodic turns of the fourth line of the chaubola , ending again on the lower tonic.

A schematic notation of the melodic range and contour of these lines is given at the end of example 7. Similar contours occur in a variety of

EXAMPLE 7. Doha-chaubola-daur |

|

(Continued on next page)

EXAMPLE 7. (continued ) |

|

Melodic contours |

|

performances, and even when the singing line is highly ornamented, the same melodic orientation and tonal focus can be observed. Example 8 contains a transcription of the voice of Chunnilal, a master singer of the Braj area, singing from Amar simh rathor during an All-India Radio interview; it includes the transcribed, scanned, and translated text. Chunnilal's doha illustrates a common variant, beginning on the middle

EXAMPLE 8. Doha-chaubola |

|

(Continued on next page)

EXAMPLE 8. (continued ) |

|

Melodic Contours |

|

|

Greetings to the emperor, protector of the world, from your humble servant . |

Your downtrodden slave has one request . |

This one request, my lord, a desire that has lodged in my heart : |

On the fifth day of the dark half of the month of Phagun, my wedding-consummation bas been fixed . |

A messenger brought the good news in a letter from Bundi . |

This miserable slave has come to take leave of his master . |

(Amar simh rathor [Hathras: Shyam Press, 1979]) |

Indicates word supplied by singer, not in printed text

third and working up to the high tonic in the first half-line, but otherwise conforming to the earlier pattern. In the chaubola , both two-line phrases begin on the fourth tone, work to the higher tonic, and then close with a descent to the lower tonic. Example 9 contains a doha and chaubola sung by Giriraj Prasad, another famous Hathrasi singer, in a performance of Laila majnun recorded in the studio of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi, and its text. Although the excerpt is highly embellished, it too conforms to essentially the same pattern in the doha . In the chaubola , the singer exhibits his virtuosity in the first line by extending the range up to the fourth of the higher octave and dwelling on the high third tone, a phrase he repeats in the third line as well. Otherwise, the tonal emphasis and contour of these phrases corresponds to the earlier model.

EXAMPLE 9. Doha-chaubola |

|

(Continued on next page)

EXAMPLE 9. (continued ) |

|

|

Here begins the story of a delightful pure love . |

Once there was a king called Amir of Damascus . |

This king was full of virtue, and he ruled his people well . |

He bad a son, Qais, who was very much in love . |

There was also a chief and his queen in the town of Najd , |

And their beloved daughter, raised in the lap of luxury, was Laila . |

(Laila majnun [Hathras: Shyam Press, 1981]) |

Within the rather fixed bounds of the doha and chaubola , opportunities occur for a substantial amount of stylistic and expressive play. Certain places in the lines provide openings, positions for sustaining a syllable with melismatic ornamentation. These openings typically occur

just before the caesuras in both lines and at the end of the first line. The end of the second line (the final word of the couplet in the case of the doha , or the last two or three syllables in the chaubola ) is never used for melodic play. Its rhyme is anticipated by the first line, and it is therefore a point of closure. Furthermore, this rhyme point coincides with the entrance of the percussion; in practice, the singer often deletes the rhyme word, a maneuver performed with an upward flourish of the hand, indicating that it is up to the audience to supply the missing (but easily guessed) syllable(s) (fig. 22).

In these improvisatory passages, the type of vocal ornamentation varies from singer to singer, but in the main it incorporates embellishments such as short tans (rapidly ascending and descending scalar patterns), murkis (mordents, turns), mind (glissando), and expressive breaks or inflections in the voice. The full repertoire of techniques known to Hindustani classical singing is not found here, nor is there the expansive freedom to improvise because of the exigencies of the text. Nonetheless, in comparison with certain popular ghazal or film songsters of today, the best Nautanki artists are accomplished vocalists with their own considerable powers of expression. Without the benefit of training, they achieve a range of vocal modulation that is stirring and forceful, keeping the listener attuned to their words and endowing the performance with an aesthetic dimension.

In addition to the most frequent doha-chaubola melodies illustrated thus far, several other common types may occur. What is remarkable is that there should in fact be so few melodies available, and that these doha variants should be so similar to one other. A degree of divergence from the most common tune certainly exists, yet any of these doha melodies would still be clearly identifiable as "doha ," especially in contrast to the tunes employed for other meters in the performance.

For the most part, chaubola tunes follow the dohas to which they are attached. Therefore in example 10 1 simply indicate the several varieties of doha melodies alone. Here, for purposes of comparison, the doha melody is rhythmically reduced to common time and each doha fills the space of eight bars. (Actual renditions would dwell on these tones in the recitative style described earlier and employ ornaments.) I label the two types discussed above A and B. In C, the second half of the doha melody is identical to the second and fourth lines of the chaubola illustrated at the end of example 7. The same is true in D, although the first half is unique in beginning on the seventh tone and then dwelling on the high tonic. The melody E is identical to A but rests on the seventh rather than the fifth at the end of the first line, and in its descent in the

Fig. 22.

Phakkar, former Nautanki actor of Lucknow, gesturing at the end of a vocal line. Photographed

in Lucknow in 1982.

EXAMPLE 10. TYPES OF doha MELODIES |

|

second line reaches only the third tone of the scale. Of particular interest are melodies F and G, both of which employ minor modes and seem to occur in narrative passages describing sad events. Though F opens in the same fashion as D, it touches several flatted notes in the descent, notably the sixth and third in addition to the seventh. Melody G rises from the lower tonic to the fifth using a set of flatted tones comparable to Rag Asavari, although in the second half it may use both the flatted and natural seventh. These two "mournful" dohas are rare but significant for the contrast they create with the dominant "happy" sound of the major-scale doha melodies.

Drumming patterns in the doha-chaubola-daur section help to mark the completion of poetic sentences, giving the singers breathing space and keeping the performance moving vigorously ahead. In general, the percussion patterns follow an implicit eight- or sixteen-beat cycle, which usually breaks into two parts: the first part displays a characteristic motif or pattern, sometimes with variations, and the second part contains a rhythmic cadence.

In example 7 the drumming following the doha features a dotted rhythm for the first four bars; this motif reappears in the tihai , a cadence consisting of a six-beat pattern repeated three times, in such a way that the last stroke coincides with the sam or first beat of the next rhythm cycle. The drumming during the daur is different from the drumming during the doha and chaubola . In this example, the first daur drum solo (after the second line of the daur ) lasts eight bars and ends in a tihai The second solo, after the fourth line, contains a cross rhythm, grouping several accented three-beat phrases within four four-beat bars. Example 11 gives additional drumming patterns. Those that are played with doha and chaubola (A, B, C) all feature the dotted rhythmic motif; the daur patterns (D, E) lack it but emphasize longer beat-length strokes with subsequent doubling and quadrupling of speed. The cadences here are often not true tihais but "crown" patterns, where a motif is played in progressively shorter phrases, leading to an anticipation of closure. Thus in pattern C, the phrase

EXAMPLE 11. DRUMMING PATTERNS |

|

(Continued on next page)

EXAMPLE 11. (continued ) |

|

The melody of bahr-e-tavil is distinctive, contrasting sharply with the doha by virtue of its heavily flatted scale. Its supple sweep and dignity must be heard to be appreciated. Here musicality is not a simple matter of scale or pitch; it is often linked to declarations of powerful emotion. In example 12 I illustrate three standard bahr-e-tavil renditions in the Hathras style, along with their texts. Each passage is emotionally charged—the first with karuna ras , the pathetic or tragic sentiment, the second two with vir ras , or valor. In consequence, the singer in each case infuses the line with a high degree of musical expression. The techniques used for this purpose include repeating dramatic phrases, throwing or pushing the voice emphatically, breaking the voice with sighs or simulated tears, or accenting through exaggerated pronunciation. These passages suggest the heights to which Nautanki music can soar.

Unlike the doha with its several variants, the bahr-e-tavil is sung to essentially one tune, with most of the variability occurring during the first phrase. Despite its very different modality, this tune shares the contours of the doha , beginning on the high tonic, moving to the lower tonic at the end of the second phrase, then rising to the fourth tone and again to the high tonic in the third, and A? to the lower tonic at the conclusion. To some extent the recitative style of the doha is also imitated, but the regular pattern of the Urdu meter, based on feet of

EXAMPLE 12. Bahr-e-tavil |

|

EXAMPLE 12. (continued ) | |

| |

A. Indal haran (AIR-Mathura) | |

chhauna ganga mem duba meri god se, | |

dekhte hi dekhte kha gaya kal hai. | |

ruth ham se vidhata hamara gaya, | |

kya kahem ye sabhi bhagya ki chal hai. | |

The lad fell from my lap and drowned in the Ganges . | |

Even as I watched, Death [Time] swallowed him up . | |

The Creator is angry with me . | |

What can one say? This is all the course of fate . | |

B. Amar simh rathor (film Yamuna Kinare ) | |

matvale ki goli se ghayal karo, | |

vaise sar ko ura do ujar hi nahim. | |

do ijazat abhi jake darbar mem, | |

dum chuka khata rakhum kasar hi nahim. | |

EXAMPLE 12. (continued ) | |

Shoot the madman and injure him , | |

And if you blow off his head, no matter . | |

Now please give me permission to leave , | |

I'll go to the court and settle the account completely . | |

C. Rani lakshmibai (AIR-Mathura) | |

apne kartabya pe hamem an sabhi, | |

khokhli bat koi sunani nahim. | |

anch jhamsi pe jjte ji anena dem, | |

pith ran mem ham ko dikhani nahim. | |

We all pride ourselves on our sense of duty . | |

No one needs to utter a hollow remark . | |

To the end of our lives, we will defend Jhansi . | |

We are not ones to show our backs in battle . | |

Schematic Notation | |

w  | |

A number of other readily recognizable melodies populate the performances studied, but rather than prepare an exhaustive index I summarize the remaining narrative and dialogue meters by referring to two further examples. Most of these stanzas are structured by their rhyme schemes into either a rondo pattern (a a b a c a , etc.) or rhyming pairs (a a b b c c , etc.). As one might by now predict, the two-line meters are sung to two alternating melodies, distinguished primarily by register. In the meter type rhyming a a b a , a contrast between high and low melodies is created, and a melodic structure similar to the sthayi-antara pattern is used, where sthayi is the melody in the lower register and antara

that in the upper. The alternation is generated by repeating the first line twice; the first time it is sung to the sthayi (A) and the second time to the antara (B). Then line two is sung to the A melody, line three to B, line four to A and so on. This in effect reproduces the high-low contrast found in the previous examples. For an application, see example 13, an unidentified meter of 28 matras (possibly a lavani or qavvali ) sung frequently in the recording of Rani lakshmibai .

In the a a b b instance, each pair would again be rendered melodically by a contrasting set of tunes. The melodic structure for this type

EXAMPLE 13. Sthayi-antara STRUCTURE | |

| |

ravali ki taraf rani chali phir vam se ai hai, [repeated ] | |

fauj do tukriyom mem shighra rani ne banai hai. | |

suna tha pas jangal mem paharom mem hai kuchh daku, | |

na kini der rani ne turant sena sajai hai. | |

achanak jo hua hamla to daku bhag kar nikale, | |

chala larne ko sagar to pari rani lakhai hai. | |

EXAMPLE 13. (continued ) |

The queen went toward Ravali and then returned from there . |

She quickly divided her army into two platoons . |

She bad heard that there were some outlaws living in the mountains and in the wilds . |

She made no delay; the queen quickly assembled her army . |

When they were suddenly ambushed, the outlaws ran off and escaped . |

Sagar Singh went to fight, and the queen found him out . |

(Rani lakshmibai ) |

Rhyme scheme:a (a) a b a c a |

Melody scheme: A B A B A B A |

of meter in Nautanki would be B A B A, where B represents a high-pitched melody, and A is in the lower register and ends on the tonic. Example 14 bears out these suppositions with a skeleton of the melody used for bir chhand in Nautanki. This narrative meter tends to be used for long passages, similar to its use in epic recitation. In the Alha singing style, however, the lower melody predominates, and the higher is used only occasionally for contrast; the melodic: structure might be something like AA AA AA BA AA AA, and so forth. The melodies, we note, are essentially the same in the epic and Nautanki renditions, but the meter in Nautanki is sung in the higher register 50 percent of the time: BA BA BA BA. This indicates a process of adaptation, wherein a sung meter molds itself to the features of its musical environment. The direc-

EXAMPLE 14. Bir chhand |

|

EXAMPLE 14. (continued ) |

itni bat suni malkhe ne, vake man mem gai hai samay, |

kh abar bhej dai sab rajan pe, aye apni fauj sajay. |

makarandi ne mal lut ko rasad sahit dini pahumchay, |

udal ko ghora rakh lino jako bendil nam kahay. |

When Malkhan heard this, he understood [what was needed ]. |

He sent word to all the kings to come with their armies . |

Makarandi distributed the provisions and foodstuffs . |

They procured Udal's horse who was called Bendil . |

(Indal haran ) |

Rhyme scheme:a a a a |

Melody scheme: B A B A |

tion of adaptation, however, is not proven. The tune might have originated with epic recitation, and been embellished by emphasis on the antara when it entered Nautanki; or it could have been simplified in passing from the more musically intricate theatrical tradition to the recitational genre.

Further consideration of the origins of the many melodies and meters that make up the Nautanki performance is beyond the scope of this research. Nonetheless, it is important to reiterate the degree of overlap that exists: many of these meters are found in other North Indian performance traditions and general characteristics may be present throughout South Asia. Musical treatment of the important narrative and dialogue meters so far seems unique to Nautanki; however, definitive comparisons cannot precede research into other theatre music.

From Competition to Commodity

Within the seemingly prescribed limits of Nautanki's metrical grammar we observe a substantial amount of melodic, rhythmic, and textually expressive play, especially in the most accomplished singing of the Hathras style. In the alap -like introductory flourishes and the elaboration of midline openings, the singer has the opportunity to demonstrate his or her virtuosity and personal creativity, while similar scope exists for the drummers in the spontaneous construction of rhythmic motifs and cadences. This "play" in the musical system—the flexibility, openness, and elasticity that allow improvisation—is closely related to audience

responsiveness. The display of musical virtuosity actively solicits audience participation: the performers seek and expect vocal signs, calls of approbation. Techniques such as the deletion of the end rhyme or the repetition of key phrases engage the spectators in the ongoing construction of the sung text. Drawn in by the tension of anticipation, they too become players and poets. Together the performers and the audience articulate the high points of emotion in the story as they interact in the joint venture of creating the performance.

While an atmosphere of cooperation between audience and performers stimulates improvisation, equally important is the edge of challenge and competition that fuels the performance. Between audience and performers, the challenge is implicit in the guessing games that the singer initiates, as if daring the audience to "complete this if you can." The audience originates its own challenges as well, in its demands for passages to be repeated (at even greater levels of musical intensity or speed) or in requests for certain preferred items. If audience members are not pleased by the performance, they manifest disapproval in distractions such as talking, in avoidance (walking away), or in open jeering and disruption.

The interplay among the performers themselves is perhaps even more important to a full understanding of the process of improvisation. Music especially in its virtuosic dimension operates as a medium for acting out rivalries between singers and troupes. Melodic elaboration is prized because it "shows" the high calibre of the singer; the key verb in Hindi is dikhana , to show not in the visual sense so much as to demonstrate or prove. The performance event is literally a "show," a proving ground, where a singer must demonstrate a sufficient degree of proficiency. The ability to hold one's breath, sing loudly, or high, or very quickly, establishes a singer's credentials as an expert, increasing his or her reputation. Improvisation is thus crucially tied to a competitive situation in which rewards are proffered for the achievement of special musical effects.

A further point, applicable to other musical styles in addition to theatre, is that improvisation is agonistic in nature; it relies on an opposition or contest between two individuals or parties. This competition generates the friction necessary for creative response. Folk theatrical forms like Nautanki characteristically involve only two leading actor-singers on stage at the same time. Their dialogues are known as "question-answer" or saval-javab ; the word javab meaning "answer" or "re-

sponse" occurs in the printed texts as a stage direction to refer to a character's speech. The saval-javab format has analogues in classical music performance and practices such as public debate of scripture (shastrarth ). The question-answer structure creates a dynamic of imitation and improvisation in performance, encouraging the continuously escalating elaboration of musical ideas. In contrast, epic recitational genres, in which there is one primary singer, inhibit improvisation and may therefore contain more static musical forms, at least as practiced at the village level. (One would expect more musical variety in an event like an Alha festival, in which different singers are competing against one another within the same arena.)

The intense rivalry that exists between Nautanki actors and their troupes is manifest in the social organization of Nautanki performers into akharas and is reproduced at every performance when the event is structured as a dangal or competition. An akhara is an arena, gymnasium, or wrestling-pit—a ground for competitive play.[17] Sociologically speaking, it is an affiliative order based on adherence to a common activity or leader such as groups of amateur athletes (especially wrestlers and practitioners of martial arts), ascetics (sadhus and fakirs), and actors and folk performers in several regions of India. The possible historical connections between the martial and theatrical arts are particularly revealing here. Beginning as a site for physical training and male socializing, the akhara acquired the characteristics of a cultural center where singing, dancing, and theatrical activities took place. In Orissa, Gotipua dancing boys were known as akhada pila because of their attachment to particular gymnasia where they were taught athletics and dancing.[18] The consecrated dancing area in Seraikella Chhau is known as an akhada ; the performers identify themselves by membership in two competing groups, the Bazar Shahi Akhada and the Brahmin Akhada.[19] The Bhagat, Khya1, Manch, Sang, and Turra-Kalagi are all traditions organized into akharas , as are nondramatic singers of forms such as Biraha.[20] An akhara identifies itself by external symbols such as a distinctive banner, crest, color, or mark and internally binds itself through initiatory practices, common rituals, and an often secret body of knowledge.[21]

Nautanki performers' discourse on their art provides further evidence of the competitive aspect. The early printed Sangits mention the poet's affiliation with a Turra or Kalagi akhara and the rivalry of actors in the theatrical arena, for example:

We bear the guise of the Turrä faction.

No one has achieved victory over those who wear the turra .

Nattha the Brahmin and Madan enter the arena with the

crest on their drum.

Raghuna leads the party in the dangal ./ Flaunting the crest

on the drum, he deals blows to the pride of the enemy.

The prefaces to some texts condemn Svang and Khyal performers for indulging in mutual narnecalling and abuses, and in several places one reads of performances ending in physical violence—an extreme form of the phatkebazi (bragging) employed to further group rivalry. On the positive side, competition produced a proliferation of performers and plays during the growth phase of Nautanki (1890-1920). At least five major akharas were active in Hathras, and dozens of other parties were performing in the region.

What were Nautanki performers competing for? As far as is known, theatrical shows in the Hathras heyday most often exhibited during fairs, festivals, and weddings, under the patronage of a prominent personage. Financial reward was thus guaranteed once a troupe was invited, but the troupe's survival depended on maintaining its reputation vis-à-vis rivals. Within the troupe, roles were graded, with the better singers playing the leads and receiving more money. Troupes tried to steal one another's stars so as to win the big bookings. Rewards or inam were also given for superlative performances. In short, competition seems to have flourished in the hopes of winning the name and fame always associated with show business.

It is likely that the Nautanki theatre also operated as an arena for contesting political and social influence at the local and regional levels. The competition between actors and singers may have been part of larger processes of establishing dominance among communities. According to this analysis, the rivalry of Nautanki troupes could be utilized and indeed fostered by opposing landlords, merchants, political factions, even religious patrons involved in their own contests for prestige and power. Unfortunately, little direct historical evidence has come to light to illustrate this process.

What I have said, in any case, should be sufficient to indicate a view at variance with that of Richard Schechner, when he states, "the occasion for theatre in India is not, nor was it ever, a competition among poets and actors."[22] Indeed, historical proof of dramatic contests is as old as the Natyasastra , which lays out rules; for how the king should award the banner of victory.[23] As I understand it, the Nautanki perfor-

mance in the days of the Hathras akharas was very much a competition. Like a sporting event, it was dominated by a spirit of play and partisanship. For the audience, part of the entertainment consisted of taking sides, expressing approval and disapproval, and engaging in aesthetic judgments—especially of the singing by the leading actors. In accordance with these expectations, the musical style was soloistic, improvisatory, and almost unbounded in its use of time. To enable all sides of the audience to hear, for example, each verse was repeated three times on each side of the stage. Proceeding at this relaxed rate, performances could easily last all night.

In the 1920s with the rise of the Kanpur style, however, a process of commercialization began that fundamentally altered the theatre's musical culture. The "ticket-line system" involving box-office sales started to replace the old patronage patterns. Shrikrishna Khatri, a wrestler and tailor before his theatrical career blossomed, introduced changes to bring Nautanki closer to the social dramas of the Parsi theatre. New topics on modern themes emerged, such as Dhul ka phul , in which two college students fall in love when their bicycles collide. In line with these changes, the music ensemble came closer to the model of Western orchestras by including instruments such as clarinets, trumpets, violins, even piano, banjo, mandolin, and bongos. Prose passages assumed a greater part in the verbal text, marked in Shrikrishna's plays by the English assignation drama . Not surprisingly, the role of virtuosic singing and improvisation declined.

The Kanpur musical style is available on a number of commercial records and cassettes.[24] These miniature performances contain several recurring musical traits. The orchestral sound here is "fuller" than in the Hathras examples, using more instruments; it serves more frequently for sound effects and scene changes. The singing line reduces its range of pitches, its duration, and the amount of ornamentation. Metrical regularity replaces the free-floating unmetered recitative, with standard meters like doha-chaubola and bahr-e-tavil molded to common time. The tunes associated with the various meters have become stereotyped, and the variety among them has diminished; recognition of metrical distinctions becomes more difficult. Fewer meters occur overall. The bahr-e-tavil comes into prominence and by comparison the doha-chaubola fades into the background.

The most obvious indicator of the musical change to the Kanpur style is the virtual elimination of modal difference. It minimizes the contrast between the bahr-e-tavil and doha-chaubola , for example, in two

ways. First, it restricts the range of the doha melody to the six notes of the descending scale, beginning with the high tonic and closing on the major third of the scale rather than the low tonic. The Kanpur doha typically conforms to the type E outlined in example 10. Second, the bahr-e-tavil is transposed from the tonic of C (with four accidentals) to the tonic of E (with no accidentals); thus, the final note of the doha melody (the major third, E) becomes the tonic of the bahr-e-tavil . The Kanpur bahr-e-tavil in consequence uses the same range and tones as the doha , extending from the high tonic to the third, with an occasional variant that stretches to the third in the higher octave (example 15). The transposition and removal of accidentals make the melodies easier for the orchestra to handle, especially for instruments with fixed intervals. The reduction of modal contrast also prepares the way for the most radical change: the introduction of Western harmony.

Before proceeding to that point, however, we return to the narrative of social, economic, and technological developments that precipitated musical change. Together with the breakdown of old patronage patterns, the 1920s witnessed the admission of women to the Nautanki stage for the first time. Gulab Bai, who was awarded a Sangeet Natak Akademi prize in 1984, was one of the first to enter the field, beginning a trend whereby women now own and control most of the surviving companies in the Kanpur area. Although women performers in Nautanki sing and enact roles in the same styles as men, the exhibition of the female body in public space—a cultural taboo—deflects attention from the music. The "male gaze" directed to the actress as fantasy object now dominates the popular stream of Nautanki. This emphasis focuses on dance and the interspersed lyric portions of the text (song forms) and reduces the recitational styles of singing associated with the older Hathras art.

Further, the introduction of the talking motion picture shifted the whole arena of competition. At first folk theatre provided models for film production but then faced its own demise as cinema seized its audience. To keep pace, Nautanki for years imitated the tunes and trends of the Bombay cinema, bringing the hits wholesale onto the stage or changing the words to fit the narrative situation. Musically this entailed the adoption of popular gits and ghazals of urban origin, enhanced by simple Western harmonizations, as well as the diverse lot of regional folk dances and songs jazzed up for film presentation. With harmony creeping in through film music, harmonium players in Nautanki parties

EXAMPLE 15. Doha AND bahr-e-tavil IN KANPUR NAUTANKI |

|

soon began to experiment with triads, adding a "modern" touch to the old recitatives.

More recently, Nautanki listening (rather than viewing) has been turned into a leisure-time activity catering to the consumption habits of the semiurban populace. This trend has taken shape in the mass production of inexpensive audiocassettes and recorded LPs of Nautanki

Fig. 23.

Record jacket: of Bhakt puranmal on Brijwani Records, pur-

chased in Lucknow in 1982.

songs (fig. 23). In this new package, Nautanki offers to the consumer one more musical commodity available at thee push of a button. Gone is the lively atmosphere of the dangal with the free play of improvisation it inspired. Instead, the soundtrack is a series of abbreviations: allusions to films, to sounds, to sentiments associated with prestige and pleasure. The new cassettes seem to be organized so that when casually dropped into a tape recorder, they offer hearers the first impression of a Hindi film score.

With widespread availability of amplification, instrumentation has changed drastically, both in live performances and recordings. One effect adopted from studio sound technology is the violin tremolo, used as background to prose dialogue, as found in an example from Bhakt puranmal , one of the most venerable Nautanki stories, in its latest incarnation on Brijwani Records. The worthy nagara , a difficult instrument to record because of its resonance and low boom, has been replaced by tabla, dholak , and even castanets. The use of harmony and

chords to accompany familiar bahr-e-tavil tunes is another innovation. Other signs of the times are reverberation and special effects: the addition of ghoulish laughter (in an echo chamber) sets the scary mood for the opening of Daku dayaram gujar on a T-label cassette. The hallmark of these performances is the vicious speed at which the story and music proceed, imposed both by the limited availability and high cost of electromagnetic tape and by the hearers' preference for "modern," that is, fast-paced, music.

While the burgeoning audiocassette, film, and television industries have helped break up the old patron-performer-audience nexus that nurtured improvisatory folk music, they have attracted mass audiences seeking new symbols of social identity through hybridized forms of rural and regional music. Cassette technology, as Peter Manuel notes, may facilitate the access of rural audiences to folk music and even offer the potential for democratic control of the means of production.[25] In this sense, the mass media possess a regenerating force that may buttress dying folk arts and stimulate their recirculation. Meanwhile, for the recently urbanized seeking a palpable sense of place, the Nautanki "hit" synthesizes nostalgia and modernity, negotiating the divide between distinctive regional cultural symbols and the homogenizing impulses of a larger public culture. Vestiges of the genre's identity remain, and the word Nautanki still carries meaning. But a new arena has been created, and music now provides a ground for playing out the conflicts accompanying development, social dislocation, and economic change.