PART III—

TWO PROVINCES

Up to here at both the national and the local level, the account of royal policy and agrarian change has been essentially episodic: of evolving theories of agrarian reform, of the struggles of ministers to solve social ills and fiscal crises, and of the evolution of different towns. The last chapter drew some general lessons from the histories of seven towns, but their validity is limited by the very uniqueness of these towns.

In an attempt to establish some historical regularities at a more macro level, the last part of this study deals with two provinces: Salamanca and Jaén. Rather than be fully descriptive, it looks at the structure and development of the rural society and economy in the form of variables that can be quantified and compared. Thus we may attempt to establish correlations between structures existing at the time of the catastro, the evolution of the next half century, and the changes that disentail produced.

The choice of these provinces results from the structure of the administration of the desamortización at the local level. Permanent commissioners of the Amortization and Consolidation Funds were established in every provincial capital and in the major cabezas de partido, while a number of lesser cabezas de partido had commissioners temporarily located in them. At least 137 localities appear as seats of commissioners at one time or another. For ease of collecting data, it made sense to choose the sales handled by certain commissioners, because they can be easily identified in the Madrid notarial archives. After some trial and error, I selected the documentation of two permanent commissioners, those in

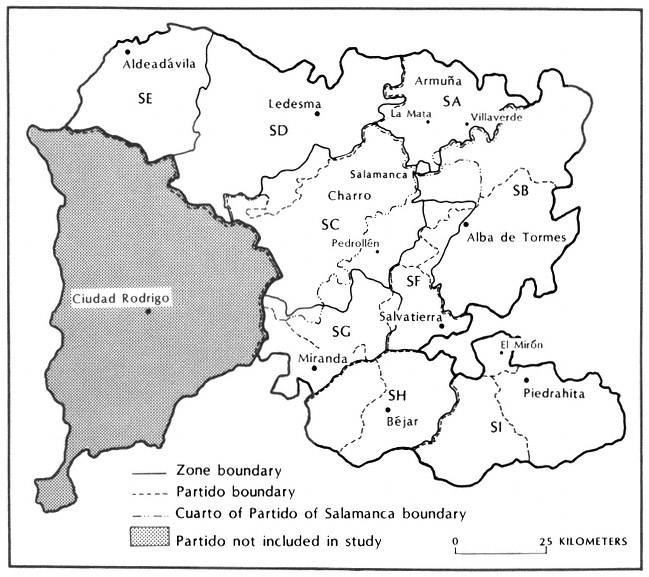

the cities of Salamanca and Jaén. The commissioner at Jaén had charge of the entire province, but in Salamanca province the extensive partido of Ciudad Rodrigo in the southwest was administered by a commissioner in that city, and I did not record his sales. My study of Salamanca province therefore lacks this territory.

They proved fortunate choices. The provinces are located in different regions of central Spain, providing examples of both sides of the Salamanca-Albacete line, and each province has considerable variety of landscape and social structure, facilitating comparative analysis. Both provinces were also areas that preoccupied the royal reformers, and they had a high percentage of church property sold.

Chapter XV—

The Social and Economic Spectrum of Jaén and Salamanca

The province of Salamanca is the southernmost of the kingdom of León. It is located south of the Rio Duero, which drains the northern meseta of Castile, a frontier region that was captured from the Muslims and settled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries in the second major push of the Reconquest. To the west it borders on Portugal and to the south is separated from Extremadura by the central mountain range. To the north and east it has no clear boundary, for the flat, rich grain-bearing tableland of the northern meseta extends south into Salamanca and forms the core of the province.

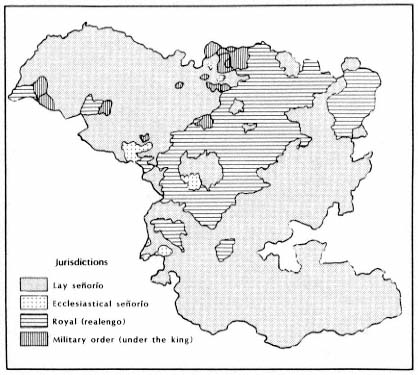

The capital city, Salamanca, sits on high ground above the Rio Tormes, and the tableland stretches out in all directions around it. Under the old regime most of this plain belonged to the partido of Salamanca, the portion of the province directly under the jurisdiction of the provincial capital and thus of the crown. To the southeast, the plains bordering on Ávila province formed the partido of Alba de. Tormes, which belonged to the señorío of the Duque de Alba; and to the west, beyond the partido of Salamanca, was that of Ledesma, most of which was part of the señorío of the Duque de Alburquerque.

Farther to the southwest, the plain spreads on into the partido of Ciudad Rodrigo, second only to that of Salamanca in extent. It accounts for most of the frontier of the province with Portugal and Extremadura. As explained before, because the royal commissioner for the disentail of Carlos IV located in Salamanca city did not deal with the partido of Ciudad Rodrigo, it is not included in this study.

The sierras in the south of the province contained in the eighteenth century a number of partidos, all under seigneurial jurisdiction. These included those of Miranda del Castañar, Montemayor, and Béjar, lying in the valleys of the sierras of Peña de Francia and Béjar, most of which are still part of the province of Salamanca. The province also embraced the partidos of Barco de Ávila, Piedrahita, and El Mirón, in the valleys to the north of the massive Sierra de Gredos, which were transferred in the nineteenth century to the province of Ávila. When we observed the town of El Mirón, we formed a sense of what these sierra regions were like.

Leaving Salamanca and crossing the central sierras and the meseta of New Castile one reaches the kingdom (reyno ) of Jaén, as it was still known in the eighteenth century. It forms the northeastern corner of Andalusia. The Guadalquivir River, whose basin forms the heart of Andalusia, rises in the imposing Sierra de Cazorla, which separates Jaén from the kingdom of Murcia to the east. To the north, the Sierra Morena lies between Jaén and La Mancha, while to the south a series of sharp ranges divide it from the kingdom of Granada. Only to the west does Jaén lack a clear geographic frontier; the province of Córdoba occupies the next portion of the Guadalquivir valley. The eighteenth-century kingdom was somewhat smaller than the present province, for the partido of Orcera now belonging to it was added from La Mancha and Murcia in the nineteenth century.

When we looked at the town of Baños, we saw that the main route from Castile entered Andalusia through Jaén after crossing the Sierra Morena by the passes of El Viso or Despeñaperros. Jaén was the first Muslim kingdom conquered by the Christians after the decisive victory of Las Navas de Tolosa—northernmost town of the kingdom—in 1212. The twin cities of Baeza and Úbeda fell rapidly, and then the Christian forces gathered their strength for a generation before pushing on to Jaén, Córdoba, and Seville in the middle of the century. Granada, to the south, held out until after 1480.

For two and a half centuries the southern mountain ranges of Jaén province were the frontier between the Christians and the Muslims, as they had been earlier between rival Muslim kingdoms. Today the fortresses that dominate the towns of Jaén and the numerous towers scattered along these mountains bear witness to this history. Even the names of many towns recall the military past: Alcalá la Real, La Guardia, Torre del Campo, Torreperogil (Torre Pedro Gil), Torredonjimeno, and the simple Torres. Other names are evidence of later resettlement: Villa-

nueva del Arzobispo, Villanueva de la Reina, Mancha Real, La Carolina (in the eighteenth century), and more recently Puente del Obispo.

In order to grasp the structure of rural society and economy of these two provinces and how it was evolving at the end of the old regime, one may start by observing how individuals behaved in the disentail. The data come from the deeds of deposit (escrituras de imposición) recorded in Madrid by the two notaries Juan Manuel López Fando and Feliciano del Corral. We met these documents in Chapter 5, where they formed the basis for calculating the extent of disentail throughout the monarchy. They are copies of the acknowledgments that the crown gave to the former owners of disentailed properties and redeemed censos specifying the amount of royal indebtedness to the former owner and the annual interest payment due on it. Between 1 January 1800 and 30 January 1801, deeds of deposit were also issued by provincial notaries. My best estimate is that the deeds of the two Madrid notaries cover about 75 percent of the sales outside Madrid province. A search through the historical archives of the provinces of Jaén and Salamanca unearthed only a few examples of deeds of deposit registered at the provincial level. Since they are not complete, I judged that their inclusion would distort more than strengthen the results, and I have based the study of the provinces and their zones on the Madrid records alone.

The deeds of deposit are printed on standard forms of three pages, which quote in extenso the royal decrees and specify the nature of the royal obligation. They provide blank spaces in which the notaries recorded the location of the commissioner, the name and location of the former owner, the date of payment for the purchase, the name(s) of the buyer(s) or the redeemer(s) of censos, the amount paid and the form in which paid (hard currency, vales reales, etc.), the number of installments for payment, and usually the type and location of the property. Each document contains up to fourteen items of usable data. I found and recorded 4,642 deeds for Jaén province and 3,314 for Salamanca.

The first step in preparing the data for analysis was to group together all the purchases made by each individual. One here faced the problem familiar to demographic historians who have reconstituted families: the name of an individual often appears with more than one spelling. Spanish orthography had not yet been standardized, and notaries sometimes recorded one and sometimes two surnames (apellidos). There are also many common Christian names and surnames in Spanish, so that identical names do not necessarily refer to the same person. I used my best judgment. If similar names appeared in the same town, I usually as-

sumed that they belonged to the same individual; if in distant towns, I did not. On the whole, the likely error is of treating the purchases of one individual as if they were made by two or more, rather than vice versa.

I concluded that 2,552 individuals made purchases in Jaén (1.8 purchases per buyer) and 2,148 individuals in Salamanca (1.5 purchases per buyer). These include 67 "unnamed" individuals in Jaén and 233 in Salamanca, my solution for dealing with deeds which read "so-and-so and two others," "so-and-so and his companions," and "various persons." In the case of unspecified plurals, I assumed three buyers. In all cases of more than one buyer, I divided the amount spent equally among them, for lack of information on each buyer's share. One must remember that the identity of the buyers and the amount they spent individually were of marginal interest in the deeds, which were contracts between the king and former owners. The information essential to this study was frequently omitted or entered hastily, for the copyists of the Madrid notaries produced fifty deeds per working day on the average, and in years of intense activity many times more.

In order to proceed, I ranked the buyers in each province in ascending order according to the amount they spent. This procedure produced Lorenz curves, with the cumulative percent of buyers plotted against the cumulative percent of the amount they spent. By their nature, the curves rise slowly at first and sharply at the end. I then divided the purchasers ranked on the curves into four levels as shown in Figure 15.1. In both provinces the small buyers in Level 1 are more numerous than the large buyers in Level 4, although the amount spent by the latter totaled ten times that of the former, a clear indication of the disparity among the buyers.

2

Once one has accomplished this step, it becomes possible to compare the characteristics of the different levels of buyers and the patterns they followed in making their purchases. Three features prove revealing: the type of property the buyers acquired, the terms of payment, and the legal estate of the buyers. The months, years, and seasons in which the buyers made their payments were also compared, but with no meaningful results. The decisive factor in determining when a buyer could make a purchase was the date that the royal commissioner put the property up for sale. The data indicate that this decision was not related in

Figure 15.1.

Allocation of Buyers to Four Different Levels

NOTE: Buyers are ranked in ascending order of

the amount of each individual's total purchases:

Level 1 —buyers of the bottom 5 percent of total purchases (0–5.0 percent)

Level 2—buyers of the next 15 percent of total purchases (5.1–20.0 percent)

Level 3—buyers of the next 30 percent of total purchases (20.1–50.0 percent)

Level 4—buyers of the top 50 percent of total purchases (50.1–100 percent)

any regular pattern to the level of buyer to which the property would appeal.

Table 15.1 shows how each level of buyers of Jaén province divided the amount it spent among the different types of property and the redemption of censos. By showing the share of their money that each level of buyers devoted to each type of property, this table reveals their preferences, with arrows to identify the trends. The lower was the level of buyers, the more their money went into arable, vineyards, orchards, and redemption of censos, and there was a strong but not complete trend in this direction for urban properties (Level 2 devoted a larger share than Level 1 to this type). On the other hand, the higher the level of buyers, the more they spent on olive groves and rural estates.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The table demonstrates a feature of the disentail that we already encountered in the individual towns of the province. One may recall that the catastro revealed that nonresident owners preferred to lease properties whose cultivation required large labor inputs (intensive agriculture) while tilling directly with hired labor and the administration of stewards the properties that called for less labor or whose production was oriented toward the outside market. Large resident landowners and local religious institutions had similar preferences, although they followed them in a smaller proportion of the cases. The economic rationality became evident when one considered the costs of the various inputs for the different types of property and the net income resulting from leasing compared with direct administration. Table 15.1 shows that when it came time to buy disentailed properties, the large buyers preferred the kinds of property that large and nonresident owners had learned was most profitable to exploit directly: olive groves and rural estates (that is, cortijos). These properties produced for the market and relied primarily on seasonal hired labor. Large buyers were not eager, however, to outbid smaller buyers for labor-intensive lands and those whose produce went mostly to feed the town, with the result that the lower levels of buyers spent a larger proportion of their money on these categories. This is notably the case for arable not located in cortijos and therefore probably distributed in small plots. Although they account for only a small part of the disentail, vineyards and orchards also went proportionately more to the lower levels.

The lower levels also demonstrated a stronger preference than the upper for urban properties and the redemption of censos. In both instances the upper levels were following a comprehensible investment policy. For them, in most cases, the purchase of buildings in the town nuclei would mean buying rental properties, from which they could expect a limited income. Leasing buildings to others attracted them no more than leasing agricultural lands. For small buyers, however, the prospect of owning a house rather than renting one had enough appeal to persuade them to spend money here rather than compete for farm land. The reasoning with censos was similar. Whether large buyers were proportionately more or less encumbered with censos than small buyers one cannot know, nor does it matter, since the amounts redeemed were not enough to have represented major shares of local indebtedness. For large buyers, the prospects of investing in market agriculture was on the whole more attractive than paying off obligations bearing 3-percent in-

terest. Smaller buyers, with fewer prospects of production for the market, showed a greater preference to redeem their debts.

All in all, the evidence reveals that as a group the people of Jaén with disposable wealth at the time of the disentail had acquired a fund of comprehensible economic reasoning. The disentail of Carlos IV placed a sufficient number of properties of various types on the market for this reasoning to produce regular patterns in the purchases of them. The trends in Table 15.1 are too clear to be the product of pure chance. Only one form of property shows no trend: improved and irrigated lands. This exception is puzzling, because most of these would be labor-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

intensive properties and in the towns we looked at large private owners preferred to lease them to others.

At first sight, the pattern of property acquired by the different levels of buyers in Salamanca province appears unlike that of Jaén (Table 15.2). Whereas in Jaén there was a clear trend for the smaller buyers to acquire proportionately more arable, Salamanca shows no such trend although there is an indication that larger buyers directed their purchases toward arable more than the smaller ones. The difference, however, is more apparent than real. Large buyers in Jaén interested in the grain market bought cortijos, classed as "rural estates." In Salamanca, as we saw in the two towns of La Armuña, large buyers acquired the collections of numerous small grain plots that the ecclesiastical institutions had built up and whose purchase the peasants could not afford. Unimproved arable was the predominant type of property in Salamanca, accounting for 59 percent of all the money spent; even though arable was also highest in Jaén, it represented only 32 percent. The difference between the provinces lay in the willingness of large buyers in Salamanca to acquire arable to lease to peasants, as the church had done. In Jaén much commercial production was conducted with administrators and hired labor, in Salamanca with tenant farmers. Rural estates in Salamanca meant primarily alquerías and despoblados, which produced both grain and livestock. As in Jaén and for the same reason, the trend in purchasing rural estates was strongly toward the top buyers.

In Salamanca the sales included a number of pastures. The table shows that they were of two kinds, large pastures that could carry extensive herds and appealed to the wealthy, and smaller ones primarily for household animals. Commercially oriented pastures went to the top level, but below Level 4, the trend was toward the smallest buyers, who were prepared to pay extravagant prices, as was the case in El Mirón.

In other respects, the two provinces were similar. More obviously than in Jaén, large buyers shied away from labor-intensive properties, especially the improved or irrigated plots, most of them walled cortinas so typical of this part of Spain. They also spent a smaller share of their money to redeem censos, and they avoided urban properties (even though the inclusion of Salamanca city in the provincial analysis means that substantial urban properties, out of reach of small buyers, figure in the table). Curiously, in both provinces, the level that showed the greatest propensity for buying urban properties was the second, not the bottom, so that this preference was not a straight linear function of wealth.

One is led to conclude that wealthy buyers had a different mentality

than more modest ones, more open to the possibilities of the market. Before accepting this conclusion, however, there is an alternative explanation that should be considered. Perhaps the difference was simply one of opportunity. In the most obvious case, wealthy buyers spent more of their money on rural estates than small buyers. The fact is that most rural estates went for high prices because of their size, and the simple act of buying one automatically placed the buyer into one of our top levels because its cost was greater than the total amount spent by a single buyer in the lower levels.

There is one way to test whether opportunity or a different economic outlook was the primary motivating factor in the different choices of the various levels. If one tabulates only those individual purchases made by all buyers that cost less than the "breaking point" between Levels 1 and 2, that is, those purchases that a person in the lowest level could have made, one can observe whether the preferences observed for all purchases are repeated here (Table 15.3). The test is not conclusive because the upper levels spent only a small percentage of their money on purchases in this price range, and the trends turn out to be fewer and weaker than when all purchases are considered. Nevertheless, those that do appear run in the direction one would expect if the big buyers had different goals than the small buyers. In Jaén the big buyers put a greater share of their money into olive groves than the small ones, and in Salamanca the small buyers preferred vineyards and orchards, in all three cases trends that were found when all purchases were tabulated. It would appear that there was indeed a difference in mentality among the levels, large buyers as a whole showing more interest in properties that were directed to the market and could be profitably cultivated with hired labor, whether they were making large or small purchases.

3

Wealth not only gave access to properties oriented toward the market but reduced the ratio of price to expected return, making expensive properties attractive in more ways than one. The royal decrees organizing the disentail, one recalls, offered the buyers a choice of ways in which to pay for their purchases, the basic choice being between payment in hard currency or in vales reales. From the beginning, preference was given to bids in hard currency (metálico or efectivo), and within a year bids for less than the assessed value (the minimum bid was two-thirds of it) could be made only in hard currency. Moreover, the smallest

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

vale real was worth 150 pesos face value, or some 2,260 reales. Sales concluded for less than this amount should have been paid in efectivo. Since the vales were depreciated, however, one finds properties going for around 2,000 reales being paid for with a vale real, but below this price, payment was almost exclusively in hard currency.[1] For sales concluded after 16 August 1801, the deeds of deposit provide an additional item of

[1] The deeds covering payment in vales usually say that payment was made in vales reales "and the balance in hard currency" (y su preciso en efectivo ) but do not list how much in each medium. Jaén deed C9404 (1801) went for 1,605 reales paid with a vale real, the lowest in the two provinces.

information, the relation between the price paid in hard currency and the assessed value, because the king now recognized his debt to the former owner for the full assessed value even if the buyer had paid less in hard currency. Until November 1802 the king also gave the former owner a 25-percent bonus if the sale netted more in hard currency than the assessment. Because bidding in hard currency could begin at two-thirds of the assessed value, sales for the assessed value ("en su tasa") or more in hard currency could result only from competing bids and show us that in these cases demand was high. Conversely, payment in vales reales suggests that there was little bidding and relatively cheap acquisitions, for a bidder could forestall further bids in vales by offering hard currency. While payment in vales had to be at least for the full assessment, vales were usually depreciated by over one-third, making the "minimum"

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

bid actually lower than the minimum bid in efectivo (see Figure 6.1). What terms the different levels of buyers used in making payment thus tell us something about the conditions under which they acquired their properties.

Tables 15.4 and 15.5 show the results. The trends are strong in almost all categories. The higher the level, the greater the proportion of its purchases paid for with vales reales. To a certain extent, the trend is inevitable, since all purchases below about 2,000 reales had to be paid for in efectivo. However, the lowest level included all buyers whose total purchases reached 4,000 reales in Salamanca and 3,390 reales in Jaén. Even the first level thus was not ruled out from the use of vales. Sales recorded as paid in hard currency at or above the assessed value after August 1801 were concluded after active bidding, and so were a large proportion of those paid for in hard currency at a price below the assessed value. The lower levels made more of their purchases in this way. The wealthier bidders, in other words, faced competition less fre-

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

quently, and they paid for their purchases more often in depreciated vales. Smaller buyers competed more actively against each other and got less favorable terms as a result. This is the case even when one considers only those purchases below the "Level 1–2 breaking point," although the larger buyers had to use hard currency more often for these small purchases than for their others (Table 15.6).

The difference between upper and lower levels is more marked in Salamanca than Jáen. In Salamanca the bigger and smaller buyers seem almost to have lived in distinct economic worlds. Level 4 buyers made four-fifths of their purchases for vales, Level 1 only one-fifth (Table 15.5). Conversely, Level 1 paid hard currency proportionately more than four times what Level 4 did. Big buyers here were into an economy based on paper money, received, most likely, for commodities sold on the national market or furnished to the crown for its armed forces. Smaller buyers lived in a world of cash on the line. They could not bid for the large properties, but the rules of the game meant that they could keep each other from using vales to buy church lands. They fought each other at the auctions, not their economic superiors.

In Jaén the trends were the same, but the differences were less marked.

Vales reales dominated the economy here less, only 45 percent of payments were made in this medium, compared to 70 percent in Salamanca (Table 15.4). The biggest buyers used vales six times more than the smallest, but the small buyers used hard currency proportionately only one and a half times as much as the large buyers.

When one considers entire provinces, as here, the range of economic means of the buyers in Salamanca appears much greater than that in Jaén. We saw earlier, however, that the distinction in types of property acquired by the different levels was more marked in Jaén. Putting both sets of evidence together, one can conclude that in both provinces there were two types of economy present, one involved in production for a nonlocal market (olives and wheat being most important harvests) and the other of a variety of products—fruits, vegetables, lesser grains, flax in Salamanca, grapes in Jaén, as well as wheat—for local consumption (self-sufficiency would be a misleading term). The market economy dealt primarily in vales reales, the local economy in hard currency. Production for the former minimized the input of labor, intensive farming was directed to the latter. In actual practice, almost every locality and most individuals participated in both economies, but each was located at a different point on a continuum that ran from the limiting case of all production for the nonlocal market to the other extreme of all for local consumption. At this time, no individual would have reached the first limit, but many small farmers (although probably not many buyers) may have been at the second limit, except that their payments for rent and tithes would enter the larger market. Disentail reinforced this spectrum.

The information on terms of payment permits one to distinguish also between purchases paid for at once and those paid for over several years. Time payments were not very advantageous; they had to be made in three installments: at the time of purchase and on the next two anniversaries, with interest on the last two. As a result this method was little used: 1.5 percent of the total payments in Jaén, 0.4 percent in Salamanca. Jaén shows a slight trend for smaller buyers to use this arrangement more,[2] Salamanca no trend. If conceived to help the less affluent to compete for the properties, the measure had a negligible effect. Again one perceives that so far as the local rural world was concerned, Spain's was still primarily a cash economy.

[2] Level 1: 2.5 percent; 2: 1.8 percent; 3: 1.6 percent; 4: 1.3 percent.

4

Finally, the data in the deeds of deposit enable one to establish a limited social profile of the people involved in the two economic worlds. First they tell us the appellation of the buyers. Some were called don or doña, but the majority not. Since these were notarized documents, it is more than likely that the use of the title depended on a legal privilege or, if not a specific document, on a well-recognized public reputation. Of the persons who made more than one purchase, a few appear at times with the don and at others without it, but they are a minority. The consistency of usage for each individual is remarkable, especially when one recalls that these were résumés of the original documents and that the name of the buyer was of marginal interest.[3] To call oneself don was not a matter of caprice but a recognition of a legal or at least semiofficial status. Among those who regularly appear with the title don are priests, who can be identified by the abbreviation pbro. (presbítero ) after their name. I have kept them as a separate category.

Table 15.7 indicates the proportion of dons and doñas and priests among the different levels of buyers in the two provinces. There are virtually no titled aristocrats (condes, duques, and marqueses) among the buyers (most aristocrats probably hid behind the name of an agent), but those that appear are grouped with the dons. (The previous tables have been based on the amount spent by the buyers; this one counts individuals, not the amounts they spent.) The table reveals very clear trends. In both provinces 70 percent of the buyers in Level 4 (highest) were entitled don or doña. With Level 1 buyers the trends run the other way: almost 90 percent without any qualification in Salamanca province, 70 percent in Jaén.

It is not easy to know who had the privilege of displaying the title don at the end of the old regime. Hidalgos (nobles) were distinguished in this fashion, and they were undoubtedly the most important part of the group. But it is certain that not all who enjoyed the appellation were legal nobles. The census of 1797 shows 785 nobles in the province of Jaén, 7 percent fewer than the buyers identified as don; and in the portion of Salamanca under study, some 441, 8 percent fewer than the buyers.[4] Since it is inconceivable that all hidalgos bought properties,

[3] See Appendix O.

[4] The category "noble" of the census of 1797 is equivalent to hidalgo; one can tell because the census of 1787 uses the term "hidalgos," while the census of 1797, in repeating the totals of 1787, calls them "nobles." For the province of Salamanca the census of 1787 gives a total of 567 hidalgos. In the region studied here, that is, without the partidoof Ciudad Rodrigo, the individual town returns of the census give a total of 533 hidalgos, 94 percent of the provincial total. The census of 1797 shows 470 nobles in Salamanca; the same proportion gives 441 in the region studied. (For the Censo español . . . de 1787 and the Censo de . . . 1797 , see Appendix A. The individual returns are in Real Academia de la Historia, legajos 9-30-2, 6240 to 6242 and 6259 [the last for the city of Salamanca].)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

there must have been many buyers called don who were not included as nobles in the census. Who were they?

It is very likely that the census takers underreported the number of hidalgos. The preface to the census of 1787 says that pressure was applied to eliminate from the number of hidalgos the persons who were not entitled to the privilege, and the number in the census of 1797 is

even less. This last gives 14 percent fewer hidalgos for the province of Jaén than the census of 1768 does for the bishopric of Jaén, and for the province of Salamanca 12 percent fewer than the bishoprics of Salamanca and Ciudad Rodrigo in 1768. Since three partidos of the province—Barco de Ávila, Piedrahita, and El Mirón—were in the bishopric of Ávila, the decline in Salamanca between 1768 and 1797 was even greater.[5] It is probable that the censuses of 1787 and 1797 counted fewer hidalgos than the persons who were reputed to be hidalgos and that if these persons bought disentailed properties, they had themselves listed as don in the deeds.

This could account in part for the number of buyers called don, but more can be explained by other categories of men addressed as don because of their vocation, whether or not they were hidalgos. Such were the priests, as already noted. The deeds reveal that high servants of the crown, officers of the armed forces, and notaries appear as don (they could, of course, also be hidalgos, as were Campomanes and Jovellanos). In the various town catastros, men with official and semiofficial positions enjoyed the title: doctors, surgeons, apothecaries, and administrators of the tobacco monopoly. The census of 1797 lists 404 notaries, doctors, surgeons, and apothecaries in Jaén (against some 785 nobles) and some 450 in our portion of Salamanca (against 441 nobles). Nevertheless, the royal government strove to limit the use of the appellation. A decree of 1775 allowed notaries (escribanos) the right to sign with the title don only if they were hidalgos.[6] Our evidence suggests that the practice was more liberal than the letter of the law, but the consistency in the use of the appellation don in the deeds of deposit indicates that it was applied only to persons with a recognized right to it.

We can conclude that the buyers who disported the don or doña had a proper claim to the title. They formed an elite of "notables," of which the true hidalgos were the most important (and probably the most numerous) part, the top stratum of the society of the old regime, not counting the exiguous high aristocracy. Table 15.7 shows that these notables dominated the top level of buyers in both provinces, the people who could spend fortunes for church properties.

This conclusion ill fits the stock hidalgo of literature and history, the threadbare and deluded Quijote. The Cervantine image was alive and

[5] The census of 1768 appears at the beginning of the published Censo . . . de 1787 .

[6] Decreto del Consejo (14 Sept. 1775), Nov. rec., VII, xv, n. 11. A RC of 19 May 1801 established, among other imposts to support the Consolidation Fund, a fee of 550 reales "for the authorization for notaries [escribanos] who are in possession of nobility to sign themselves don" (ibid., n. 12, and in more detail in AHN, Hac., libro 8053, ff. 195–200).

well in the mentality of the eighteenth-century reformers, recognizable in the scornful portrait of the rural noble painted by José Cadalso: "He takes the air majestically in the sad square of his impoverished village, wrapped in his poor cape, admiring the coat of arms above the door of his half-ruined house, giving thanks to God for having created him don Fulano de Tal."[7] A picture that twentieth-century historians have not abandoned,[8] but our provincewide analysis of the disentail brings its accuracy into question. It is not the first such piece of evidence; the reconstruction of the society of Lopera and Baños in Part 2 already revealed the economic and political power of the local hidalguía. We shall return to the issue when we look at the big buyers in Chapter 19.

Priests followed the same trend as the dons, toward the higher levels of buyers. Not all priests can be identified, because the qualification pbro. was not always added in the deeds,[9] so that the trend toward the larger buyers may be exaggerated, but it is not spurious. Part 2 has shown that in the towns of Salamanca the income of the priests was among the highest in the parishes, that in those of Jaén the priests belonged to the best families. In Chapter 19 we shall see another, higher clerical world represented among the buyers, that of cathedral canons, capellanes, and university professors. Their means permitted a significant number of them to make purchases that placed them among the upper levels of buyers.

One can also identify the gender of the buyers from the deeds, in this case relying on their first names and the title doña (Table 15.8). If one considers all women as a group, one finds no trend in the proportion of buyers who were women from level to level in either province, but when the women are divided between those who were called doña and the others, the same trends become apparent as among the men, doñas being more common in the top levels and commoners at the bottom. That is, family and social level, not gender, determined the economic behavior of women. (Because some of the "unnamed" buyers in Table 15.7 would have been women, the correct trend for commoner women would be toward an even stronger presence in the lower levels that Table 15.8 shows, especially in Salamanca.)

With this added information one can give a social definition to the economic spectrum observed earlier. The persons who engaged in the commercial agricultural economy, those who had developed a capitalist

[7] José Cadalso, Cartas marruecas, Carta 38, quoted in Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad española, 116. Fulano de Tal is the Spanish equivalent of "so-and-so."

[8] Callahan, Honor, Commerce, and Industry, 8.

[9] See Appendix O.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

mentality, were typically (but not exclusively) hidalgos and priests and other notables with official positions. The other economy, of production for local consumption, belonged primarily to commoners. The deeds of deposit tell one nothing about their occupation, but the largest number would have been peasants, like the vecinos of La Mata and El Mirón or the labradores peujaleros of Las Navas. Others may have been muleteers or bakers or craftsmen. When we come to study the big buyers, we shall find persons who may be properly classified as bourgeois—administrators of estates and merchants—in the upper levels. One may suppose that others of this kind are unidentified in the lower levels; after all, even the lowest buyers would have had some kind of standing in their towns. But the bourgeois would have been a minority in all levels.

The cases of Jaén and Salamanca indicate that Andalusia and Castile at the end of the old regime had a dual agricultural economy and a corresponding dual society. At one extreme was a peasant society producing primarily for local consumption; marked by high labor inputs; relying on hard currency (when not on barter), which the peasants saved carefully and brought forth to bid against their neighbors when given the chance to buy plots of land of their own. For such buyers, the disentail offered the opportunity to acquire the lands they farmed. At the

other extreme, the notables and a lesser number of wealthy commoners controlled the market economy; sought to minimize the costs of labor on their lands; and accumulated depreciated vales reales, which they could use to buy those disentailed properties that could expand their commercial output. Though functionally and socially different, the two economies were not physically separate. Most individuals connected with agriculture engaged in both, to a greater or lesser extent. In the towns of Jaén those who concentrated on the market lived cheek by jowl with the others; in Salamanca, the commercially oriented were more likely absentees residing in the provincial capital or the cabezas de partido. Such is the general picture that emerges from the provincewide analysis of the deeds of deposit. To refine it, we can turn to the variations among the geographic zones within the provinces.

Chapter XVI—

Jaén Province:

The Determinants of Growth

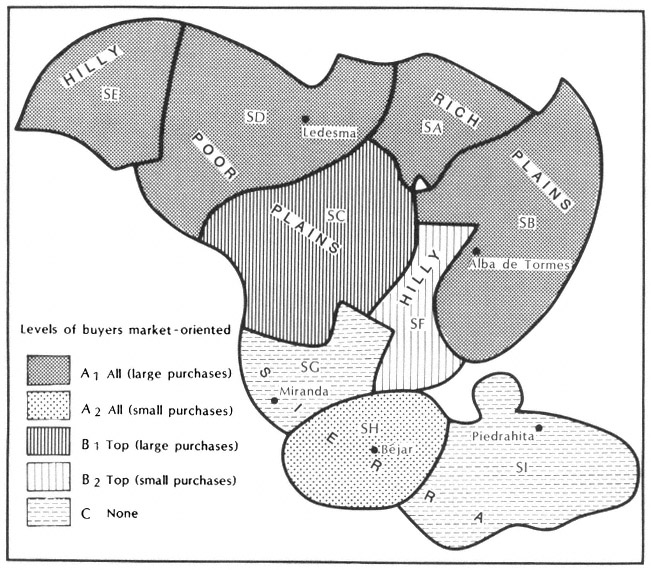

In order to proceed, I have divided the two provinces into a number of zones that I have sought to make geographically and economically homogeneous. They have been drawn on the basis of maps and studies of the physical landscape and geology and extensive personal travels throughout the two provinces by automobile. The purpose is to establish units with different social and agrarian patterns that can be used for a comparative analysis of their evolution.

The division of the province of Jaén into zones is not obvious. Except in the mountains, the region has a low rainfall, weather stations reporting a mean annual precipitation ranging from 487 millimeters at Cazalilla near the Guadalquivir River to 601 millimeters at Jaén. Conversely, evaporation is high everywhere. There is not much difference in annual mean temperature either, ranging from 16° to 18° centigrade. Climate, in other words, is relatively similar throughout the study region, with a cool, moist winter and spring, and a hot, dry summer.[1]

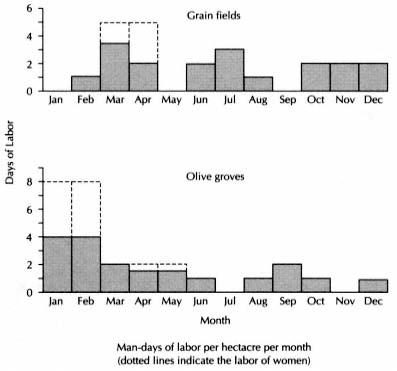

In the eighteenth century and still today, agriculture predominated over grazing, even in the mountain valleys; and agriculture was, and is, marked everywhere by a division between wheat fields and olive groves. The marls that predominate are excellent for olives but less favorable to

[1] Information on the geography and climate of Jaén province comes from Higueras Arnal, Alto Guadalquivir, and Lázaro, Elias, and Nieves, Regímenes de humedades. In addition, I was given invaluable help by don José María Ontañon and doña María del Carmen Cid of the Centro de Estudio Hidrográfico, Madrid, whom I consulted at length and who traced maps of the soils of Jaén for me.

the cultivation of wheat, and over the centuries olives have been gradually replacing wheat. Today there are districts where the rolling hillsides of red or brown earth are dotted as far as one can see with silvery green olive trees set out in precise geometric patterns, columns of plumed soldiers marching up hill and down. In few places of the world has reason tamed nature so successfully. Yet, lest we forget that this is Andalusia, the two or three trunks that make each tree, taunting imposed discipline, become circling dancers with arms flung back in their own flamenco ritual. But go on a few kilometers and the unbroken rows of trees give way to rectangles of alternating olive grove and grain fields, the latter verdant and waving in the spring, sprinkled with brilliant flowers, then brown and parched after the June harvest.

There are few level plains, for the basin of the Guadalquivir undulates in waves of different lengths, heights, and directions. On reaching the southern ranges, the land rises sharply, and a short way up the olive trees give way before thin soil or barren limestone rock, the stark mountains wrapped in flowing green polka-dotted skirts, Gypsy maidens decked out for a perpetual fiesta of the local Virgin. The richness of Jaén's rolling basin, with its broken pattern of olive groves, wheat fields, and stark white towns, the towering ranges on the south and east, the wild, wooded Sierra Morena on the north, make the province a constantly varied vision of beauty.

As is common in southern Spain, the inhabitants of Jaén are gathered into large settlements. In the census of 1786, Jaén had seventy-four cities and towns, with an average population of 2,380. Both for military defense and to escape the heat of summer and the danger of epidemics, most towns of Jaén stand white and nucleated at high points in their territories. Baños is a good example. In the Guadalquivir basin many sit on hilltops, and at the southern and eastern edges of the basin they are located up the base of the mountains, with their fields stretching out beneath them and the barren slopes above serving as protection from attack. The capital city, Jaén, at the foot of the Sierra de Jabalcuz, is a perfect example, dominated by the Castillo de Santa Catalina, which commands the two approaches from Granada, the older western road that circles the higher ranges and the newer road south through the sierra. On the northern limits of the province, the ranges are lower and several towns nestle in saddles where roads pass through the hills, as does Navas.

Close by the towns, where water flows either from streams or wells, lie the irrigated huertas with their vegetable plots and fruit trees. In the

eighteenth century, and still today, the closest land to the nucleus was called the ruedo, the most intensively cultivated zone that is not irrigated. Beyond is the campiña of the town, not to be confused with the term campiña applied generally to the basin of the Guadalquivir as opposed to the sierra. In the empty spaces between the towns of the basin there were, and are, scattered residences and farm buildings of the large estates, the cortijos that roused the ire of Carlos III's reformers and of those of the Second Republic and the casas de campo in the major olive groves. In the case of Baños, we saw that this land use reflects the pattern known as von Thünen's rings, with the intensity of cultivation depending not only on quality of soil and availability of water but on the distance from the town nuclei.

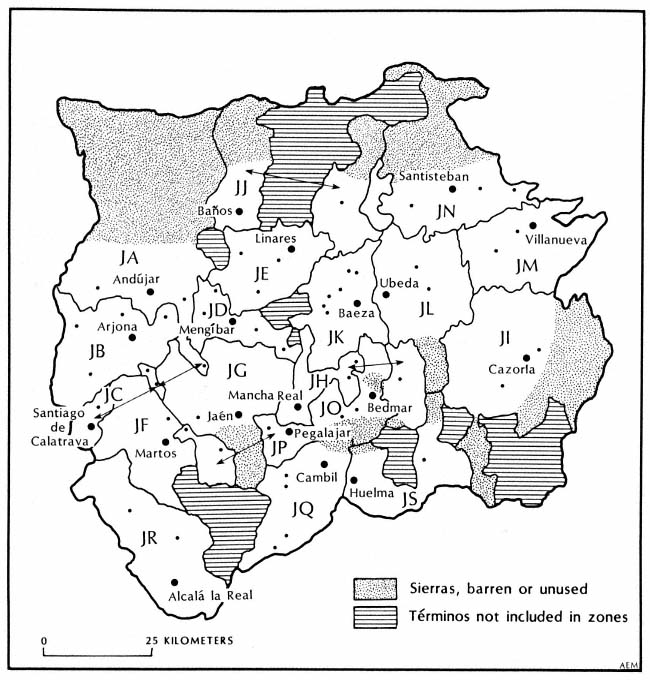

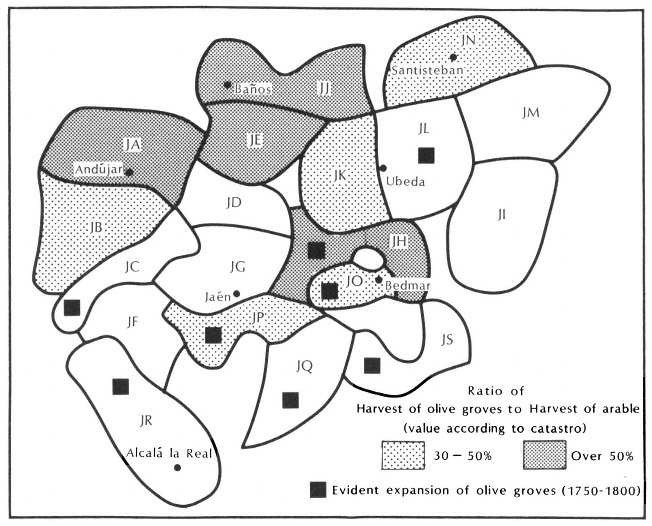

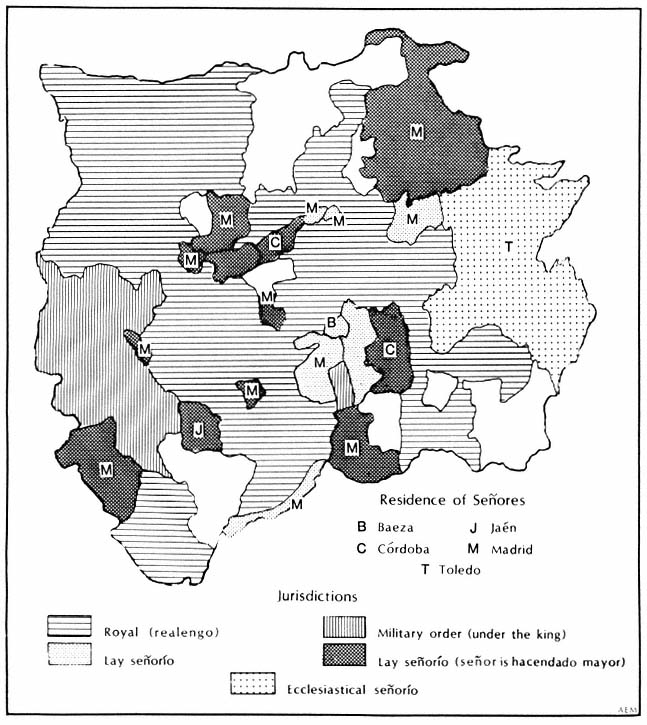

I divided the province into nineteen zones (Map 16.1). Five are located fully in the valley of the Guadalquivir, in the western part of the province. Three have rich soil, centering on the cities of Andújar (Zone JA); Arjona (JB), which includes the town of Lopera, studied in Part 2; and Linares (JE). In the ensuing analysis, they are referred to as rich basin zones. The two other zones in this region are further south, in a rolling plain where salt deposits have reduced the fertility of the soil. Santiago de Calatrava zone (JC), made up of three distinct blocks because of the way the municipal boundaries run, is near the Córdoba frontier, while Mengíbar zone (JD) is in the center of the province. They are called poor basin zones. South and east of this region are four zones whose towns have their lands in the valley of the Guadalquivir and their town nuclei against the foothills of the southern and eastern ranges. Identified here as south basin zones, they are Martos (JF), Jaén (JG), Mancha Real (JH), and Cazorla (JI). The Sierra Morena zone, JJ (Baños), is in the foothills of this range and is made up of the town we studied and a similar one called Vilches. Two rolling ridges or hog's backs (lomas ) rising between rivers in the northeastern part of the province are the location of four zones, the two to the west rich loma zones: Baeza (JK) and Ubeda (JL); and the other two poor loma zones: Santisteban (JN), which includes the town of Las Navas of Part 2, and Villanueva (JM). Finally five zones are located south of the basin of the Guadalquivir. Three of them are sierra zones, Bédmar (JO), Pegalajar (JP), and Cambil (JQ); and two lie in broad valleys in the south, isolated from the rest of the province, Alcalá la Real (JR) and Huelma (JS), the southern valley zones. Appendix P provides a detailed description of the geography, population structure, and political status of these zones.

Map 16.1.

Zones of Jaén Province

2

Few readers will have been surprised to learn from the previous chapter that two types of economy existed in the provinces—market and local—and that they can be associated with different social groups, although the prominent role of nobles and clergy in commercial agriculture may seem paradoxical at first. If we turn to the data for the individual zones within the provinces, we can refine this simple observation, for the zones show that the different factors associated with the two types of economy come together in a variety of ways to produce distinct

subpatterns, which in turn help us to understand the economic forces at work in rural Spain at the end of the old regime.

When added to the deeds of deposit, the midcentury catastro and various censuses provide a diachronic perspective. The detailed information of the catastro on individual property holding in each town, which made possible the studies in Part 2, is unmanageable at the provincial level, at least for this study. The royal bureaucracy in the eighteenth century, however, extracted much of the information from the reports and their results have fortunately been preserved in most cases. The Archivo General de Simancas has a precise listing of the property of the largest owner in each town, the hacendado mayor, including his, her, or its (if it was an institution) name and residence. Simancas also has a copy of the responses to the forty questions that formed the first part of each town survey, with data on the number of vecinos, houses, people in various occupations, wages, prices, types of harvest, tithes, taxes, and similar matters ("Respuestas generales" or "Interrogatorio general"). Even these questionnaires are not readily usable in extenso—they may run to fifty folio sheets for one town—but their contents were extracted and tabulated in large volumes now in the Archivo Histórico Nacional. This series normally has three volumes for each province, the first ("Estado seglar") devoted to the property and other income of laymen and secular institutions (including the town council, that is, town property); the second ("Estado eclesiástico") for that of ecclesiastical institutions, foundations, and funds; and the third ("Eclesiástico patrimonial") for that of individual clergymen. For purposes of the present study, I have assembled these data, already quantified town by town, into totals for the zones within the province. Unfortunately, for Jaén only the volume summarizing the information of the secular estate has survived.[2]

A number of eighteenth-century censuses have been preserved that give the population (vecinos or total inhabitants) of individual towns. The "Vecindario general de España," located in the Biblioteca Nacional and already described in Chapter 1, gives the vecinos around 1712. The number of vecinos at the time of the catastro (ca. 1752) can be obtained from the respuestas generales, question 21, but it has also been tabu-

[2] For most towns the information is drawn from AHPJ, Catastro, maest. segl. The volumes with this information are missing for the following towns, and I obtained it from the copy in AGS, Dirección General de Rentas, Única Contribución, libros 323–27: Albánchez, Alcalá la Real, Cabra de Santo Cristo, Castillo de Locubín, Fuente del Rey, Higuera de Calatrava, Jabalquinto, La Guardia, Los Villares, Lupión, Marmolejo, Tobaruela, Torre del Campo, and Torrequebradilla.

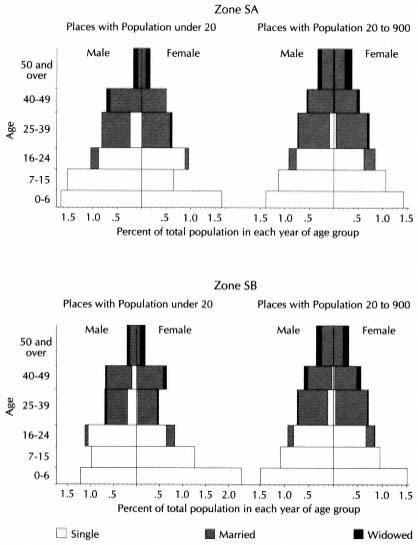

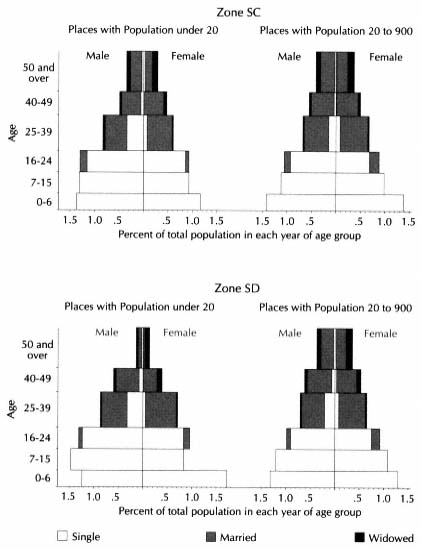

lated from the towns of Salamanca province in a document in the Real Academia de la Historia.[3] The same place houses the original individual town returns of the census taken in 1786 and published the next year. These record the number of each sex, single, married, and widowed, in each of six age groups, as well as the number of individuals in various legal estates and occupations.[4] Finally, I have made use of the number of vecinos and inhabitants recorded for each town in 1826 by the royal geographer Sebastían de Miñano.

The information on the sales has been described in the last chapter. It is now, however, broken down by zone, and within each zone by level of buyers.[5] The level of each buyer is determined by his location on the Lorenz curve of the zone.[6] Thus in a zone where purchases were priced low, a buyer who appeared in Level 3 or even 2 in the province may be placed in Level 4, and vice versa. Buyers in Level 4, or any other level, do not spend equal amounts of money from zone to zone and are not equally wealthy. Table 16.1 gives a sense of the difference among the zones in Jaén province in this respect. It shows the mean purchases of Level 1 and Level 4 buyers and of all buyers in each zone. If one compares the mean amount spent by all buyers in each zone, as shown in this table, with the mean town population in each zone (Table 16.2), one finds a rough, direct relationship (r = .52). One can deduce that, as a general rule, in larger towns, the upper levels of society, those that furnished the buyers of disentailed properties, had more money than the corresponding levels in smaller towns. The correspondence is far from exact, however, r2 = .275, meaning that only about one-fourth of the variation in the amount spent can be attributed to the size of the towns in the zones.

By using the commercial market–local consumption spectrum that emerged from the global look at the two provinces, one may distinguish the zones in Jaén province by the strength of the orientation of their agriculture toward a wider market, as revealed by the nature of the prop-

[3] Real Academia de la Historia, leg. 9-30-3, 6258, no. 13. It is dated 30 Jan. 1760, but it comes from the returns of the catastro. Ibid., no. 14, is a later census of vecinos dated 14 Aug. 1772. I entered it in my analysis, but it proved of little use.

[4] Ibid., legajos 9-30-2, 6228 and 6240–42; 9-30-3, 6259.

[5] All sales but one (in an isolated town not included in any zone) could be assigned to zones. Where the location of the property was not specified in the deed of deposit, I assigned the sale to the zone in which the religious institution that was the former owner was located. No doubt some lay elsewhere, but not enough to invalidate the analysis. The number of sales in each zone is JA, 186; JB, 147; JC, 22; JD, 28; JE, 179; JF, 283; JG, 911; JH, 289; JI, 263; JJ, 116; JK, 762; JL, 482; JM, 273; JN, 208; JO, 47; JP, 160; JQ, 59; JR, 146; JS, 80; Total 4,641.

[6] See Chapter 15, section 1, esp. Fig. 15.1.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

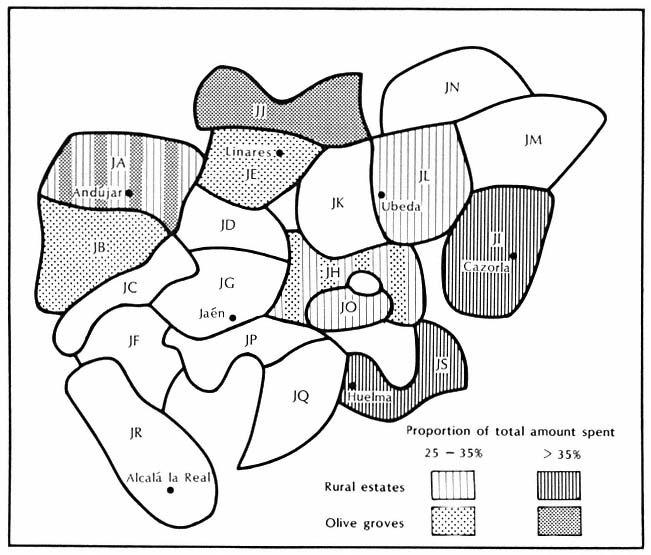

erties disentailed. For instance, although some olive oil was consumed locally, one can posit that most owners and buyers of olive groves were conscious of a national and even an international market and involved in it. Unfortunately, arable land, the largest type of purchase, involving 32 percent of the money spent, could produce wheat and other grains either for local consumption or for the broader market, so that the amount of it disentailed in each zone does not help one distinguish the economy of the zone. On the other hand, cortijos and other rural estates, which can be identified, did produce primarily for the broader market. Table 16.3 and Map 16.2 distinguish the zones by the percent of the total purchases devoted to olive groves and to rural estates. The higher the readings, the more the zone can be assumed to produce for the market economy.

Olive groves are strong in the north and west of the province, cortijos in the south and east. The only zones with strength in both types of cultivation are Andújar (JA), bordering Córdoba province on the Guadalquivir River, and Mancha Real (JH), between the Guadalquivir and the southern ranges. The two zones in the northeast (JM, JN) and a belt of

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

zones in the center and south (including the zone of Jaén city) do not show up as high in either type of clearly commercial property (JD, JF, JG, JK, JP, JQ, JR).

To understand better the economy of the various zones, one can distinguish them according to the orientation toward the market of the different levels of buyers. The purchases of each level show if it was primarily interested in buying properties directed toward market production and was able to acquire them. I shall divide the zones into three

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

categories according to these criteria, using the premise that olive groves and cortijos were engaged more in market production than other types of property. Some grain grown in small plots was also destined for the outside market, of course, but since much of it would be for local consumption, the marketed proportion of the grain not grown in cortijos would be less than that of the cortijos. Vines would also be directed toward an outside market, but most fruits and vegetables would be too perishable.

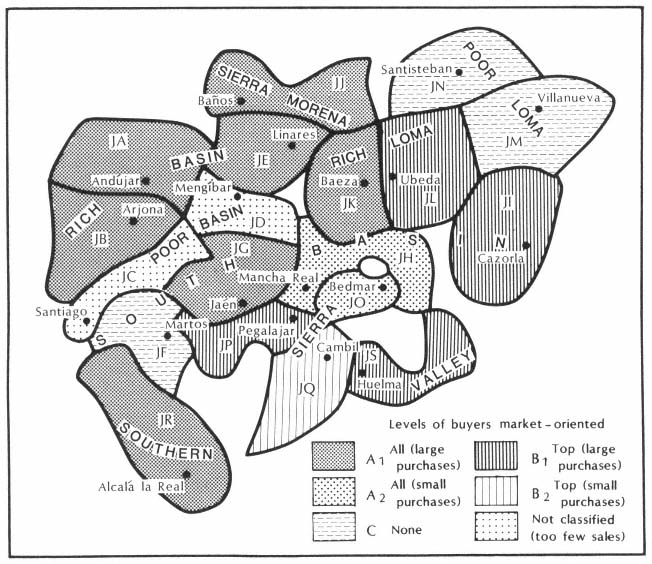

The three categories of zones are as follows:

Type A. All levels of buyers into the market. Those zones where both Level 4 and Level 1 buyers directed their purchases toward market-oriented properties. To qualify for this type, Level 4 buyers (highest) must devote the largest share of their purchases to olive groves or rural estates or both together, and Level 1 buyers (lowest) must either devote a larger share of their purchases to olive groves than to arable or must

Map 16.2.

Jaén Province, Rural Estates and Olive Groves in Disentail, 1799–1807

have olive groves as their next choice after arable. The second alternative for Level 1 buyers is necessitated by the fact that in most zones sales of arable outweighed considerably sales of olive groves, so that Level 1 buyers, even if they preferred olive groves, had more arable available to purchase. Zones where Level 1 buyers preferred urban properties, improved or irrigated plots, or the redemption of censos to olive groves do not qualify for this type.[7]

Type B. Top levels of buyers into the market. Those zones where Level 4 is into the market but Level 1 is not, under the terms defined above. These are primarily zones strong in cortijos, where Level 1

[7] In Zone JO, Level 1 preferred improved or irrigated plots to olive groves (24 percent to 21 percent), but they also bought many vineyards (14 percent). Since vineyards produced for the market, I have included this zone in this category. (It is impossible for Level 1 buyers to have rural estates as their preferred type of purchase, since most of these were cortijos, whose price was greater than the total amount spent by someone in Level 1, and thus rural estates are not used as a criterion for considering the market orientation of these buyers.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

buyers did not have available olive groves that would put them into the market.[8]

Type C. No levels of buyers into the market. Those zones where neither Level 4 nor Level 1 is into the market as defined above. Although these zones obviously sold some produce on the outside market, the nature of the properties that were disentailed indicates that this commerce was not conducted on a major scale and was not the primary objective of local agriculture.[9]

Table 16.4 shows the distribution of the zones into these three types.

3

One may now proceed to compare these different types of zones on the basis of other known characteristics. For instance, the mean amount spent by the buyers in each zone proves to be related to the extent that the buyers were into the market. If one ranks the zones according to the mean amount spent and draws a line between numbers 11 and 12, as is done in Table 16.5, one finds that seven of the nine zones in Type A (all levels into the market) and four of five zones in Type B (top levels into the market) are above this line. All the zones in Type C (no levels into the market) are below the line. Zones JH and JO, belonging to Type A, fall below the line. The considerably smaller mean amount spent by their buyers than those of other zones in Type A indicates that these two zones had a distinct economic level and deserve to be grouped separately. I have therefore divided Type A into Types A1 and A2 . The same is true for Zone JQ in Type B, which becomes the only zone in Type B2 . These subcategories are already incorporated in Table 16.4. Henceforth most of the discussion will exclude Type A2 and Type B2 zones, which are too few in number to draw conclusions about the significance of their characteristics. With these exceptions, being into the wider market, whether by all levels of buyers or by the top levels, meant that the properties sold in the zone were more expensive and the average buyer spent more than in the zones that were not into the market.

[8] Zone JP shows a high demand among Level 1 buyers for improved or irrigated plots (23 percent). Some of these were probably devoted to market gardening for nearby Jaén city, but I do not count this as production for a wider or national market.

[9] This categorization ignores the purchases of Levels 2 and 3. In most cases Level 2 preferences reflect Level 1, while Level 3 is closer to Level 4. Thus Type A is properly called "All levels of buyers market oriented" and Type B "Top levels market oriented."

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Map 16.3 shows that these types reflect geographic affinities. Except for the two unclassified poor zones, JC and JD, marked by infertile soil, small towns, and few purchases, most of the central and west of the Guadalquivir valley consists of Type A zones (all levels into market). Type B zones (top levels into market) form a ring around this block on the east and south, while Type C (no levels into market) are peripheral in the northeast and southwest. Only one Type A zone is not contiguous to the others, JR (Alcalá la Real), made up by the three rich valleys in the southwest. Type A2 zones (all levels into the market, small purchases) lie next to each other on the eastern edge of the A zones, and the B2 zone (top levels into the market, small purchases) is nearby, in the long valleys above Jaén city.

Because of the way in which being into the market is determined, with the bottom levels depending on the purchases of olive groves and the top levels on either olive groves or rural estates, one would expect Map 16.3 to reflect closely Map 16.2, which shows the zones of heavy purchases of olive groves and rural estates. There is a similarity but by no means an identity. All the zones that had a large proportion of their

Map 16.3.

Jaén Province, Types of Zones

sales in olive groves do, in fact, fall into Type A (except Zone JC, not classified for lack of sufficient sales), but so do four other zones that were not strong in olives. In three of these, the small buyers sought the available olive groves within their means, while the upper levels went for rural estates. In the fourth, JO (a Type A2 zone), Level 1 got into the market by buying vineyards as well as olive groves. Three of the six zones strong in rural estates thus fall into Type A, leaving only three others for Type B, along with two others not strong in rural estates. Those zones that had a large share of their sales in either rural estates or olive groves belong to one of the types that were into the market—and quite properly so—but by concentrating their purchases on the available rural estates (JP) or olive groves (JQ), the upper level of buyers placed two other zones among those where the upper levels were into the market.

One may question whether the division of the zones into these three types in reality represents different orientations toward the wider mar-

ket. It could, for instance, be simply a reflection of the size of their towns, with Type A zones containing the largest towns and Type C the smallest. (One recalls that we have found a rough correlation between the mean size of the towns and the mean amount spent by the purchasers.) If one treats these three types of zones as random samples drawn from an imaginary larger population of zones with similar characteristics and applies a test of significance to the differences in the size of their towns in 1786, one finds no significant relation between town size and the three types. The mean town size has the expected trend, but the difference in town size varies so widely within each type of zone that the difference is not significant.[10] The three types of zones thus reflect something other than town size.

Another possibility would be that the types offer a measure of general economic activity and not simply the market orientation of agriculture. To explore this possibility, one must go back fifty years to the information in the catastro. Table 16.6 shows the proportion of artisans and craftsmen among the vecinos in each zone in the early 1750s. On the surface, the three types of zones do seem related to artisan production. The mean number of all craftsmen per thousand vecinos declines from Type A1 , to B1 , to C and, disaggregating the crafts, so do the numbers of carders and weavers and of tailors. On the other hand, the number of sandalmakers (alpargateros) per thousand vecinos is highest in Type C zones and lowest in Type A1 , responding perhaps to the greater isolation of Type C towns. Tests show that these trends are not significant, however, because of the wide variation among the readings within each type of zone (again treating the three types of zones as if they were random samples drawn from a larger population). The same is true of the income of the retail food stores per vecino, although here there is a hint of a possible relationship.[11]

In fact, other factors can be more readily associated with at least two types of crafts. The concentrations of carders and weavers, for instance, are found in the zones with the largest mean town population, and indeed, they are located in the large towns. Jaén, Ubeda, Baeza, Alcalá la Real, and Andújar, the only municipalities in the province with over two thousand vecinos, had 109 of the 115 carders in the province and 148 of the 156 weavers. Alpargateros also have a different association.

[10] Mean town population: Type A = 3,230, B = 2,960, C = 2,680. Despite the apparent trend, the null hypothesis, that all three types come from the same parent population, is not disproved by an analysis of variation, whether one uses the mean town population for each zone, or the individual population readings of all the towns.

[11] An analysis of variation shows F = 1.75. For a 20 percent probability, F = 1.87.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The high concentrations (over ten per thousand vecinos) all occur in the four loma zones and Cazorla, contiguous in the east. Theirs was a regional specialty.

On the other hand, one kind of activity recorded in the catastro correlates well with the three types of zones. This is the income of muleteers (arrieros). Table 16.7 shows the income per vecino from muleteering in the zones, and Map 16.4 locates the towns that reported income from

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

muleteering. Type A1 zones have a mean per vecino income from arrieros of 19.5 reales; Type B1 , 5.8; Type C, 0.9. An analysis of variation shows that there is less than a 5-percent probability that these differences occurred by chance. Even more conclusive is a comparison of the number of towns in each type of zone that had a major sector of muleteering (here defined as having a minimum of one thousand reales total annual income for all the arrieros in the town). Eighteen of twenty-seven towns in Type A1 , zones reach this figure, three of twelve in Type

Map 16.4.

Jaén Province, Income from Muleteering, ca. 1750

B1 , and only one of eleven in Type C. The difference in proportions is significant at the 1-percent level.

Of course, active muleteering could be independent of the nature of local agricultural production, as is shown by zone JQ, the deviant case labeled Type B2 . It had the largest arriero income per vecino of all the zones. It lay on the new road from Madrid to Granada through the sharp valleys south of Jaén city, and all its arriero income came from the two towns nearest the border with Granada, Campillo de Arenas and Noalejo. Relatively small mountain towns, they specialized in transport independently of their agricultural activity. Zone JD was a similar

case, second in income per vecino from arrieros only to JQ. All of its arrieros were located in one town, Mengíbar, site of the main ford across the Guadalquivir River on the way south to Jaén and Granada. A small town, it was nevertheless the largest of five in this poor valley zone and prospered from its location. Surrounded by zones actively into the market (Type A1 ), it stood in a natural spot to develop muleteering.[12] Elsewhere the variation in the amount of muleteering income among the three types of zones lends support to the proposition that the types do in fact represent different orientations toward commercial agriculture. Although positive proof is lacking, all the information adduced leads to the conclusion that the three types of zones differed in the market orientation of their agriculture but not significantly in other forms of economic activity except muleteering, which can be seen as a forward linkage of commercial agriculture.

4

Having determined the extent of the involvement in the market of the agriculture of the different zones, we may proceed by observing how this factor is related to their social structure. To begin with, I shall use the information provided by the sales during the disentail. One statistic is especially revealing: the proportion of the buyers who were notables (as defined in Chapter 15). Table 16.8 gives these figures for Levels 1 and 4 and all buyers, broken down by type of zone. Among the three types of zones, there is a significant difference in the proportion of buyers who were notables. Zones with all levels of buyers into the market (Type A1 ) had the highest proportion (46 percent), zones not into the market (Type C) the lowest proportion (30 percent), while those where only the top levels of buyers were into the market were in between (35 percent). This trend appears also among Level 1 (small) buyers, but not to a statistically significant extent among Level 4 (large) buyers. The previous chapter showed that there were many more notables among the top buyers in the province as a whole, and the table shows that to be the case in the individual zones (except the zones not included in the three types because they had few buyers). Not here, however, but in the lower levels does a clear pattern emerge of the proportion of buyers who were notables directly correlated to the extent of involvement in the wider market.

[12] For its location at the main ford, see Biblioteca Nacional, Tomás López, "Atlas particular," and Laborde, View of Spain 2 : 108.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The census of 1786 reveals that the pattern was not peculiar to buyers alone but characterized the population as a whole. The zones where all levels of buyers were into the market (A1 ) were those with the largest proportion of nobles among the residents. The census called for an enumeration of the hidalgos in each town, a piece of information not included in the questionnaire or provincial summaries of the catastro. Table 16.9 shows the number of hidalgos per thousand adult males in each zone. In many respects the accuracy of the census for Jaén is suspect, as already noted in the case of Baños, so that the number of hidalgos reported may not be correct. The trend is clear, however. The ratio of nobles to adult males is distinctly higher in all but two Type A1 zones than in Type B1 , zones (the two deviant A1 , zones are contiguous in

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the north center). Two of the Type C zones show a lower proportion of hidalgos than the large majority of Types A1 and B1 zones, but the third, JM in the northeast, has the highest ratio of all zones. (The high count is in the two newer towns Villacarrillo and Villanueva del Arzobispo, the other older, pre-conquest town Iznatoraf reported only one noble. One cannot tell from the data whether the deviance of JM is real or the result of an enthusiastic census taker.) Except for these three cases the pattern reflects the picture drawn from the sales: the more fully a zone was involved in the outside market for agricultural products, the larger was its class of hidalgos.

This information permits us to look again at the conclusion reached in the last chapter about the relation between social class and commercial agriculture. The data in Tables 16.8 and 16.9 indicate an apparent paradox. The zones of local economy (Type C), where the average amount spent by the buyers was low, mostly located on the periphery of the province, had the fewest nobles and the most distinctly stratified group of buyers (small buyers having a far smaller proportion of nobles than large buyers). By contrast, the wealthy zones, where all levels of buyers were into the market and the average amount spent by buyers was high, had the most nobles and reveal the least stratification among

the buyers. The percentage of nobles is higher and more evenly distributed among the levels. Zones in which only the top levels of buyers were into the market lie in between.

If one recalls from Part 2 the contrast between Baños and Lopera on one hand (both located in zones where all levels of buyers were into the market, JJ and JB), and Navas on the other (zone JN, no levels into the market), one can posit a conclusion. The first two had a wealthy resident elite headed by a number of hidalgo families. Their elite formed a distinct layer at the top of the social pyramid (8 percent of the vecinos in Baños, 10 percent in Lopera, see Tables 11.20 and 12.14), which ran their towns and extracted wealth from the land without getting their hands dirty. But in Navas there was only one landowning don out of 214 male vecinos, the notary. The information provided by the present chapter indicates that this contrast can be generalized to the entire province. One can conclude that there were two distinct typologies of social structure in Jaén province. Towns in zones actively engaged in commercial agriculture attracted more wealth and developed a strong resident economic, social, and political elite of which hidalgos formed a major part. Nonnobles were a vast majority of the vecinos, but among the buyers they were a bare majority (a minority in two zones), and even at the lowest level of buyers they were not an overwhelming majority. The conclusion of the last chapter is reinforced: the presence of commercial agriculture and a strong resident hidalgo class went hand in hand.

At the other extreme, areas involved primarily in a local economy did not produce or attract a resident elite of this nature. A few hidalgos were present and formed the apex of the social pyramid. When they bought disentailed lands, they sought the best properties, having the most money to spend, and dominated the top level of buyers, where they might be joined by outsiders. But they left to local commoners the largest amount of land put on sale. Although there was greater disparity in the composition of the buyers, this reflected a smaller and weaker, not a stronger, local elite.

Type B zones, where the top levels of buyers were into the market, are a halfway stage between the two extremes. Disentailed property here was split more evenly between what was commercially oriented and what was produced for local consumption. The elite of notables, smaller than in Type A zones, stressed the purchase of market-oriented properties, leaving the less expensive properties to the noncommercialized, nonnotable sector of the towns.

5

This analysis of the relationship between the different types of agricultural activity and social structure offers a static picture of the rural world of Jaén at the end of the old regime. Our next task will be to make the picture move, to demonstrate evolution during the half century under study and discover the forces at work. The data will not always permit the sequence to be fully in focus, but the picture will be instructive, nonetheless.

One may start by determining in which zones the market economy was expanding. For this purpose, one would like to compare the proportion of land devoted to harvests for the market at the time of the catastro with that shown by the sales, but the data available do not permit so precise a comparison. The catastro of each town states the area devoted to each type of cultivation and the value of the annual harvest,[13] while the records of the sales give the price but not always the size of the ecclesiastical properties that were sold. The extent of land devoted to the various harvests at the time of the sales is unknown, but from the available data one can compare the value of land devoted to cereals and olive groves at the time of the catastro with that shown by the sales. If the ratio of olive groves to arable shows an increase between the two dates, one can assume increasing production of olive oil for the market. There is unfortunately no way of determining an absolute increase in grain production for the market, but because the demand for olive oil was outdistancing that for grain, as will be explained below, greater participation in the market was likely to show up as an increasing ratio of olive groves to arable.

Even here there are difficulties. One saw in Chapter 5 that the ratio of catastro value to sales price varied widely among the properties devoted to different cultivations. One must adjust for the different markup of the two types of property when comparing figures from the two sources. Table 16.10 shows the results.