An Assessment of Batak Health Status

To assess the status of Batak health, I rely on two major kinds of evidence about physiological well-being: anthropometric measurements and informal clinical assessment.

Nutritional Anthropometry.

My primary source of data on the health status of the Batak is their nutritional status and derives from my repeated measurements of the weights, heights, upper-arm circumferences, and skin fold thicknesses of men, women, and children over the course of a year. Given their relatively small numbers and dispersed settlement pattern, a major difficulty with obtaining such data among the Batak was simply locating adequate numbers of individuals to take measurements from. Children, in particular, were especially scarce, and instead of following any systematic sampling procedure, I simply tried to take measurements from as many individuals as possible. I limited my efforts to the two largest local groups: Langogan, where I resided during 1980–81, and Tanabag, where I had resided during 1972 and 1975 and which I continued to visit periodically during my stay at Langogan. But despite this concentration of my measurement efforts, there was still the problem that the Batak rarely come together as a group, and even at Langogan, I spent many hours carrying my anthropometric equipment along the trails to scattered field houses and forest camps, searching out the members of my “sample.”

In these circumstances, it was essential that my equipment

be easily portable. For weighing, I employed a beam balance provided by the Nutrition Center of the Philippines. The balance was suspended from a tree limb or roof beam, and the individuals to be weighed sat in a sling suspended from the scale. The scale arm was calibrated up to 25 kilograms, but individuals of up to 75 kilograms could be weighed by hanging additional weights on the end of the beam. My other equipment consisted of an anthropometer and a pair of Harpenden skin fold calipers. When combined with a notebook and provisions, these items made for a somewhat ungainly pack. But it was essential to be mobile, and I was.

If locating adequate numbers of Batak was difficult, the Batak themselves proved highly cooperative. Adults and older children were weighed individually, without footwear and in minimal clothing. Infants were weighed with their mothers and their weights later determined by subtraction. I did not weigh at any particular time of the day, nor did I attempt to control for gut or bladder content. I did note what each individual was wearing at the time of weighing and eventually weighed samples of clothing and ornaments to determine average weights for each item—shirts, bark loin-cloths, skirts, brass ankle bracelets, and so on. I later deducted these weights, as appropriate, from my field measurements; thus, all weights discussed here are nude weights. I measured skin folds at two standard body sites: at midtriceps on the upper left arm and subscapular, on the left back. I took three readings at each site during each encounter and then averaged the three. At the same site where I measured the mid-triceps skin fold, I also measured arm circumference using the tape measure. In the case of children, I also measured head circumference. After completing my measurements, I gave each adult a stick of tobacco and each child, some candy.

I eventually measured at least once 44 men, 40 women, and 24 children, a total of 108 individuals and more than 40 percent of the total population of “core” Batak shown in table 10. To explore the possibility that seasonal change in food availability might be sufficiently severe to be visible in

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seasonal variation in weight and fat accumulation, I repeated my measurements three times over the course of the year. I took my first set of measurements on January 31 in Tanabag and between February 20 and March 29 in Langogan, a dry-season period of average food abundance. I took my second set of measurements on August 1 in Tanabag and July 16–23 in Langogan, at the height of the preharvest “famine season.” I took my third set of measurements on October 18 in Tanabag and November 11–14 in Langogan, during a period of postharvest leisure and rice abundance. Weighed at least twice were 35 men, 28 women, and 16 children. The 44 adult men measured once or more averaged 153.1 centimeters in height and 46.5 kilograms in weight; the 40 adult women measured once or more averaged 143.2 centimeters in height and 40.5 kilograms in weight. Tables 18, 19, and 20 classify height, weight, and midtriceps skin fold thickness, respectively, as a function of sex and age. [ 1]

With what should we compare these data to determine what they tell us of Batak nutritional status? One possible comparison is with comparable data for other equatorial hunter-gatherer groups. Table 21 presents such data for the Agta and the !Kung Bushmen. This comparison is intriguing because of the considerable similarity in body measurements among these three groups, but it does not resolve the question because there is no consensus about whether these other

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

groups suffer from nutritional stress. In the Bushman case, for example, there is disagreement about whether their small stature and their physique are evidence of chronic or seasonal undernutrition (Truswell and Hansen 1968, 1976) or of efficient adaptation to a particular climatic and subsistence regime (Tobias 1964:76; Lee 1979:289–292). Interpreting his Agta data, Headland (1986:394–396) takes the former position. After his own careful evaluation of Agta health status, he concludes that their extreme thinness is not the result of physiological or genetic adaptation but of nutritional deficiencies. Griffin (1984:22–23), describing the deteriorating health of women in another group of Agta, does not report anthropometric data but similarly concludes that they suffer from “malnutrition.” The ultimate problem, however, is that no one knows exactly what the weight of a well-nourished desert or tropical forest forager should be.

In the absence of such knowledge, Tables of Standards derived from measurements of other populations provide another basis for comparison of anthropometric data. Such tables allow one to calculate the proportions of a population sample that stand in particular relationships to the standard value, which is taken to be the most desirable value. The most widely used such standards are the Harvard Standards, which appear in Jelliffe (1966); selected for comparative purposes here are the weight-for-height standards. This widely used evaluation of body proportions is presumed to reflect current nutritional status and to be relatively independent (in comparison to weight or height for age) of genetic influence (Waterlow et al. 1977). Table 22 displays the comparison between these standards and the weight and height data in tables 18 and 19. Table 23 makes a similar comparison using the midtriceps skin fold data in table 20. Table 22 shows that the median weight for height for both sexes is only about 85 percent of standard, with about half of the adult men falling below 80 percent of standard. [2]

Lee (1979:289) makes the same comparison using his data and with the same result: the average !Kung male and female

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

each weigh only 83 percent of the standard weights for their heights. Again, however, Lee questions the validity and applicability of the standards more than he does the nutritional well-being of the !Kung. My feeling is that Lee, anxious to defend the hunting-gathering way of life, is too ready to dismiss such comparisons. However, after exhaustively pursuing the possibility that any seasonal food shortages might be visible in marked seasonal weight fluctuations, Lee found almost insignificant weight losses and gains over the course of a year—on the order of only 1.0 to 1.5 percent of adult body weight.[3] Seasonal weight fluctuation of only about 1.0 percent has also been reported for the Efe Pygmy, who resemble the Batak and !Kung in body proportions and who depend on agricultural food for a large part of their subsistence (Bailey and Peacock n.d.).

The Batak present a sharp contrast. Although I only weighed nineteen adult men and nineteen adult women three times, I found considerable seasonal weight fluctuation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

among them (see table 24). (As we saw in chap. 3, the Batak do suffer a famine season, albeit an agricultural one.) Adults lost 3.2 to 4.2 percent of their body weight between February and July and gained back 2.6 to 3.1 percent between July and October. Skin folds fluctuated considerably—on the order of 15 to 20 percent. These data suggest that the Batak, while otherwise anthropometrically similar to peoples like the !Kung, may indeed be in greater nutritional difficulty.

Turning to the twenty-four children, a local basis for comparison is provided by the weight-for-age standards employed by the Philippine government in its “Operation Timbang” program to assess the extent of rural malnutrition. While these standards are clearly closer to home, they are meant to apply to the lowland Filipino population, not to Negritos. The validity of the comparison is again problematic as these two populations do differ genetically. If the comparison is valid, however, the Batak children I measured were in a poor state. Table 25 shows that half weighed less than 75 percent of the standard weight for their age, and a few weighed less than 60 percent of standard. All of the school-age children in the sample would be considered underweight, three severely so. My arm circumference measurements suggest a similar conclusion. Arm circumference

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

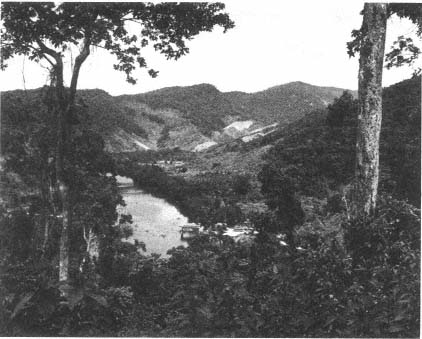

Forest clearance by lowland settlers near the mouth of the Langogan River. The

Batak reside twelve kilometers upstream.

Batak on the move between their settlement and a forest camp.

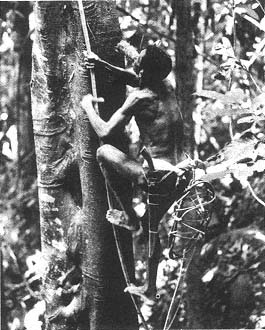

The Batak are agile tree climbers. Here a man collects wild

honey, a favorite food.

Wild pigs are hunted at night, from blinds in trees.

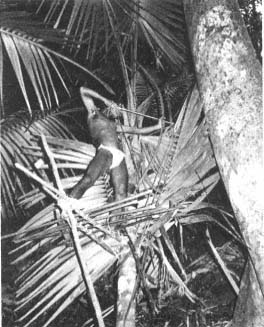

A typical leaf shelter at a forest camp.

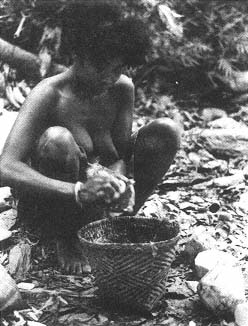

A woman processes wild yams.

Dry season forest camps may be out in the open. The woman is weaving a mat

for drying rice after the harvest.

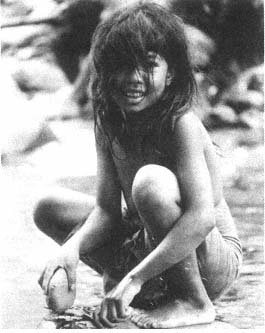

A girl pounds a poisonous tree bark used for stunning

fish.

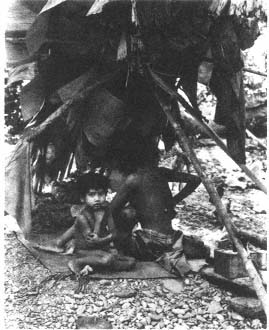

Batak children: two sets of siblings related as first cousins.

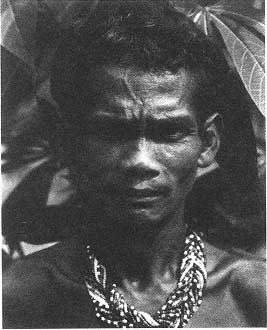

A Batak man.

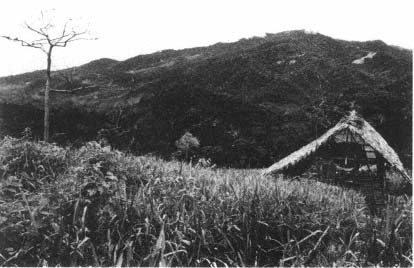

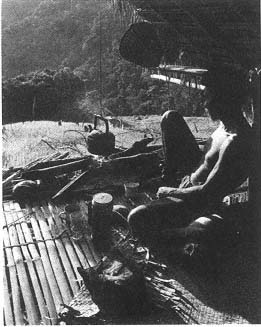

A rice field house.

An upland rice field.

Batak men hired by a lowland settler to help clear his

homestead.

A man guards his rice field against the intrusions of

wild pigs and monkeys.

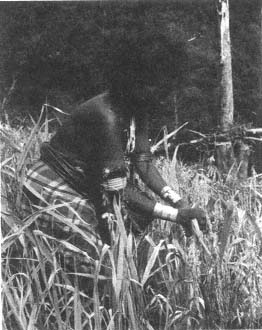

A woman harvests upland rice.

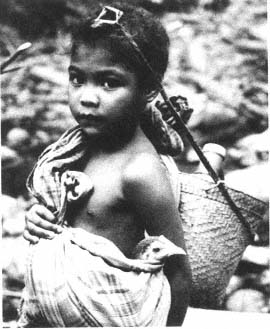

A girl helps her family move its possessions from one

forest camp to another.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

is considered a good index of muscle wasting and hence of protein-calorie malnutrition in children (Berlin and Markel 1977:75). Of the nineteen children whose arm circumferences I measured one or more times, only six exceeded 85 percent of the reference value (classified by age and sex) shown in Jelliffe (1966). Of the remainder, eight children fell between 75 and 85 percent of the reference value and six fell between 65 and 75 percent.

Incidence and Severity of Infectious and Communicable Diseases

Even if the Batak are somehow “too thin,” what difference does it make? With this question in mind, it is appropriate to turn now to my other major kind of evidence of Batak health status—the diagnoses that physicians and other medical personnel have made of the conditions they have observed among the Batak. Given the influence exerted by nutritional status on resistance to and recovery from infection (Scrimshaw et al. 1968), the conclusive proof of whether Batak thinness should be judged dysfunctional may in part be sought in the incidence and severity of infectious and com-

municable diseases. If, on the one hand, the Batak go through their lives relatively free of serious illness and survive in large numbers to old age, perhaps one may justifiably dismiss as irrelevant comparisons of Batak anthropometric measurements with Western-derived standards. But if, on the other hand, the Batak do not enjoy such lives, we may indeed want to regard their nutritional status as marginal.

In addition to making (admittedly untrained) clinical observations of Batak health problems, I often inquired about causes of death of deceased individuals in the course of obtaining my census data. Of course, in the absence of a physician's diagnosis, it is often difficult to determine precisely kinds of illnesses and causes of disability and death, particularly among people like the Batak who do not subscribe to the germ theory of disease and who do not normally classify their health problems in the fashion of Western medicine. The Batak were of some help in this enterprise, however; in cases of death due to illness, for example, they readily described the part of the body most affected and the most visible symptoms prior to death. Some illnesses (e.g., tuberculosis) could be deduced with relative confidence from such descriptions, although others could not (thus, the Batak usually describe any illness accompanied by severe fever as malaria, and they probably attribute more deaths to malaria than it actually accounts for in practice). Fortunately, doctors have visited the Batak from time to time, and I am able to draw on some of their appraisals as well as my own.

Epidemic disease, the great depopulator of tribal societies, has played its role in the demographic history of the Batak. They have apparently been spared the devastating epidemics that reduced some tribal groups to small fractions of their aboriginal numbers (Dobyns 1966; Driver 1969). Rather, the Batak have been swept repeatedly by smaller, more localized epidemics—measles, cholera, and influenza have all taken their toll. A case in point is a measles epidemic that occurred in Langogan in December 1980. Of the fifty Batak present at

the start of the epidemic, twenty contracted measles during December. Among these twenty were virtually all of the small children, most of the teenagers, and four adults who had previously escaped the disease. Four children, ages one to three, died; two adults almost died and were said to have survived only because of intervention by City Health Department personnel. In addition, two children of Tagbanua families living among the Batak also died. The impact of this same epidemic on the lowland Langogan population was strikingly different. Approximately three times as many lowland adults and children contracted measles during December, but all survived (without medical assistance).

The Batak were particularly vulnerable to contagious disease in December; as we saw (chap. 3), in November and December the Batak are concentrated in their settlements, often with two or three families sharing a single dwelling. But despite a more dispersed settlement pattern, many lowlanders contracted measles as well. It is unknown whether their higher survival rate reflected genetic or immunological factors or better nourishment or care.

Over the longer term, however, chronic, rather than epidemic, infectious and communicable diseases have likely been the single greatest cause of Batak mortality. Those diseases that most seriously plague the Batak are malaria, tuberculosis and other respiratory infections, and gastrointestinal infections. Palawan, in general, has a serious problem with malaria; both vivax and falciparum are endemic. The latter, now chloroquine resistant, is probably the biggest single cause of hospital admissions on the island. All Batak adults claim to have had recurrent bouts with malaria, and on many occasions, I saw individuals apparently suffering from malarial fever. In 1980, a team of health workers examining spleens and blood smears estimated that 70 percent of the Langogan Batak harbored malarial parasites. Only occasionally do Batak obtain and use antimalarial drugs. Rai (1982:134) believes that malaria only became a significant health problem for the Agta after lowland Filipinos entered

their environment and established agricultural fields. I cannot assess whether this interesting contention applies to the Batak as well, but there is some evidence that malaria is more prevalent among indigenous peoples living at the fringes of an altered forest than among more nomadic peoples living within an intact forest (Wirsing 1985:314). In any case, while malaria itself may account for relatively few deaths, the disease is debilitating and likely decreases Batak resistance to other, more life-threatening infections.

Among these other infections is tuberculosis. Unfortunately, no tine tuberculin tests have ever been administered among the Batak; they frequently attribute deaths to a set of symptoms—chronic coughing, coughing up blood, prolonged weight loss—indicative of tuberculosis. Indeed, “the chest” is probably the most commonly cited locus of terminal illness, although chest ailments are not limited to tuberculosis but probably also include bronchitis and pneumonia. An instructive comparison may again be drawn with the Casiguran Agta, who closely resemble the Batak in general health status as well as in anthropometric measurements. Headland (1986:394) reports that respiratory diseases are the most common causes of death, with tuberculosis being the single biggest killer among adults and pneumonia being the biggest killer in the population as a whole. Recently introduced tuberculosis is a serious threat to many tribal peoples, and there are places where mortality from this disease has for many years exceeded the birth rate (Wirsing 1985:307).

Another locus of terminal illness often cited is “the stomach,” with “disenteria” or “loose bowels,” sometimes said to contain blood, as the most visible symptom. Again, it is likely that these terms gloss a variety of medical conditions—from amoebic dysentery to severe infestations of intestinal parasites. No stool samples have ever been examined among the Batak, but they would undoubtedly show a variety of helminths (see Dunn 1972). Two unverified accounts of deaths involving high fever mentioned worms leaving the ears and nose of the dying individual.

Such difficulties with epidemic and chronic infections—and the levels of infant and child mortality discussed in chapter 4—strengthen my earlier conclusion that Batak nutritional status is indeed marginal. In the developing world generally, for example, mortality due to measles is said to be a result largely of poor nutritional status (Scrimshaw et al. 1968:15–16). Along the same lines, Buchbinder (1977) has demonstrated that local Maring populations in New Guinea which suffered the greatest mortality from introduced infectious diseases also suffered the greatest degree of chronic malnutrition.

The Batak have apparently been spared the ravages of venereal disease. I saw little evidence of degenerative disease. Teeth and eyes do often fail in older individuals, and I observed several adults with cataracts or opaque lenses. There are no living blind Batak. One adult is blind in one eye, and there is one living deaf-mute, age 42. I saw only a few individuals who appeared to suffer from rheumatoid arthritis. Leprosy and rabies, occasional health problems on Palawan, are known and feared by the Batak, but I learned only of one death attributed to rabies.

Less serious, but highly visible, are a variety of skin lesions and diseases, notably, tropical ulcers, scabies, and ringworm. They are a source of much discomfort and embarrassment to the Batak. I have known entire families to be infected with scabies; they would lie awake all night, scratching themselves in agony. And for the fastidious lowlander, the stereotypical Batak is covered with ringworm (or “doubleskin,” as it is known locally) over 70 to 80 percent of his body. Many Batak escape such diseases, but many do not: I estimate that scabies or ringworm, or both, is a chronic problem for almost half the Batak at Langogan. Lowlanders blame poor hygiene for these conditions, but individual Batak appear to differ not only in their hygienic practices but also in their predisposition to skin diseases. The living conditions and cultural practices that affect the transmission of these and other diseases are discussed below.

There are, to be sure, other causes of disability and death among the Batak besides disease. Most distinctive for outsiders are the various occupational hazards associated with the hunting-gathering life (Howell 1979:54–59). Snakebites, falling from trees, being gored by wild pigs, accidents with weapons—these are the things that might appear to make Batak life dangerous. In fact, however, although the Batak do often talk about and even fear such hazards, actual incidents involving them are uncommon. My data on this subject are not systematic; they concern the number of cases of various kinds of accidental deaths that several adults, questioned together, could recall as having occurred since they were young among the Langogan and Tagnipa Batak, today totaling 23 households but once totaling many more.

The only fatal snakebite recalled in these two districts occurred during World War II. (In late 1981, a Babuyan Batak died of snakebite; it was likely the only such death in the entire population for at least ten years.) Only two Langogan Batak have ever been bitten by venomous snakes, probably by the common Philippine cobra. The only Langogan Batak recalled as having been attacked by a wild pig survived it. No individuals could be recalled who died because they were accidentally shot by another or because they fell out of a tree while collecting honey, although two men who limped slightly were pointed out as having experienced precisely these kinds of accidents. Similarly, no deaths were reported in these districts as the result of weapons malfunctions, although in 1977, a Tanabag Batak did die after a homemade “pigbomb” he was carrying exploded prematurely.

Somewhat more important may be accidents not related to hunting and gathering per se but to forest life in general. For example, a man was said to have died at Langogan several years before my arrival as the result of a severe infection from a foot wound he sustained while walking in the forest. Similarly, my informants recalled one small child who accidentally fell into a river and drowned and two infants who apparently smothered in their blankets. Childbirth, of course,

can also be hazardous; a number of women were said to have died during or after childbirth. Such deaths are not common, however. In addition to the likelihood of rigorous selection against any genetic predisposition for difficult childbirth (Howell 1979:58), women who experience a difficult childbirth and survive may take an herbal preparation to prevent future pregnancies (see chap. 4). (Headland [1986:538], however, estimates that about 14 percent of adult Agta women die as a result of the complications of childbirth.) In summary, even allowing for some undercounting, the risks and accidents associated with the Batak way of life are not a major cause of death. Rai (1982:133), reviewing the causes of Agta mortality, similarly concludes that occupational hazards are infrequent causes of injury or death.

Finally, there are the injuries and deaths that can occur as a result of interpersonal violence, but such incidents among Batak are truly exceptional. From Howell's (1979:59–62) account of interpersonal violence and homicide among the !Kung and her estimate that such violence accounts for 5 to 10 percent of all deaths known, it appears that the !Kung are not the “harmless people” Thomas (1965) thought them to be. But such a characterization could be applied with some accuracy to the Batak. Landor (1904:145) reported them to be a “most peaceful people, shy and retiring,” who never fought among themselves or with others. (Similar peoples inhabiting the Malay Peninsula have been described as remarkably nonviolent; see Howell 1984:34–38.)

After years of inquiry, I failed to turn up one case, present or past, in which one Batak had killed or intentionally injured another Batak. Such behavior is quite simply unthinkable. Furthermore, despite the variety of frictions and intimidations associated with contact with lowland Filipinos (see chap. 6), only on two occasions within the memory of living Batak has a lowlander actually killed a Batak. In 1968, a lowlander shot a Batak in Tanabag while both were drinking. This incident was widely discussed among the Batak as the first of its kind. A second murder in 1975 at Tagnipa was

more threatening. A Batak involved in a land dispute with an influential lowlander was found hanging from a tree, an apparent suicide. No one familiar with the case believed it to be a suicide, but no arrests were made. Only on one occasion, apparently, has a Batak killed an outsider: in 1971, incensed at having been cheated in an economic transaction, a Caramay Batak shot a widely disliked lowlander with a bow and arrow. He was not apprehended until some years later when, during a drinking spree, he bragged publicly about the murder. He remains in detention today.

The Batak may have suffered more violence at the hands of outsiders prior to 1900. As we saw in chapter 2, the sultanates of Sulu and Brunei long raided Palawan for slaves, and every adult Batak can recount how the feared “Moros” surprised and carried off one of his or her kin as a young child. But it is impossible to assess the quantitative impact that such raiding had when it was practiced.

Infectious and communicable diseases, in synergistic interaction with poor nutrition, are by far the most significant cause of disability and death, if only because other causes of disability and death are absent or unimportant. I now turn to the causes of poor nutrition and the factors governing the transmission of disease.