"Harlem Renaissance Man" Revisited:

The Politics of Race and Class in Still's Late Career

Still reached his artistic maturity as a versatile and innovative commercial musician and composer of concert music in Harlem in the 1920s. He sought to break down race-based limitations on the mixing of African American and European techniques, forms, and styles through the use of blues-based harmonic progressions, melodic turns, forms, and sometimes rhythms in his symphonic music as well as to blur class-based boundaries between the "popular" and the "serious." Unlike his white modernist colleagues, Still had nothing to gain and everything to lose by using the exclusionary, modernist creative languages such as serialism or atonality. His personal interest lay with integration into the larger society and the larger musical language–in becoming, as he said, "another American voice" whose work confounded both race- and class-based distinctions. His 1934 move to Los Angeles now appears to be an act of self-exile, one that allowed him to work out his own highly individual creative position–a position that continues to problematize his contribution to American music for both white and black observers. By leaving New York City, he distanced himself psychologically as well as geographically from the interconnected aesthetics and politics of white modernist composers and black intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. He repudiated essentialist racial distinctions but embraced and even exploited cultural difference in his art. In pursuing his own creative imperative, he was forced throughout his career to untangle and then reweave in his music (as in his life) many strands of American culture, strands in-

volving race and musical genre, class differences and political loyalties, gender and geography.

Over a period of a quarter century, his audience grew steadily. Yet his music often drew ambivalent critical responses that were permeated with stereotypically race-based expectations. The 1949 production of Troubled Island by the New York City Opera, a case in point, formed the apogee of Still's rise as a composer. But after that production, he came to believe that he was the target of a communist conspiracy. Here I want to discuss Still's outspoken anticommunism. Far from being a frivolous stance easily dismissed as personal paranoia, I propose that Still's anticommunism and his acceptance of what I will call the "plot theory" are closely connected to the race-based critical expectations often assigned to his music across his career. I make no attempt to explain or justify Still's public denunciations of other individuals; rather, I limit myself to an attempt to understand the political position that lay behind his unfortunate public statements.

Before addressing the questions about how it was that Still came to subscribe to a communist-inspired conspiracy theory and participate in the anticommunist movement, it is necessary to say a few things about Still's politics, his relationship to communism, and the anticommunist movement itself. Controversy over communism and the Communist party was lively and pervasive in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Despite the monumental indifference to matters political ascribed to him by his friends, Still could hardly have avoided contact with creative artists who were both politically involved and interested in communism in his New York years.[1] Carlton Moss describes dining with Still at the Harlem YMCA, "the only decent place to eat in Harlem" and a major gathering place where political discussions must have swirled around him; he could scarcely have shut them all out.[2] In the late 1920s and 1930s, Still worked with at least two writers who were close to the party. One of them was Moss, who supplied the short story on which Still's first opera, Blue Steel, is based; the other was Langston Hughes, author of the libretto for Troubled Island . Still welcomed the opportunity to compose these operas, both on black subjects. He collaborated amicably enough with Hughes on the project until Hughes left for the Spanish Civil War. He was even interested enough to put his name on two Popular Front-style letters supporting the Spanish Civil War, a liberal cause that was co-opted by the Soviets.[3] Given the disruption of Harlem society in the

course of the Great Depression of the 1930s, it is possible that he shared at least a passing interest in communism with a good many Americans, including many modernist composers. In A History of Musical Americanism, Barbara Zuck gives a long-accepted explanation for this passing interest: "The Communist Party had an important sociopolitical function at this time in its organized agitation against groups fostering discrimination and racial hatred. Thus, political leftism in the 1930s simply became a common framework in which the American intelligentsia expressed their idealism and humanitarianism."[4] Still's anti-communism flies in the face of this long-accepted explanation.

From the first public performances of his works in new music concerts in the 1920s, critics sought to pinpoint musical indications of Still's racial identity. They frequently evaluated his work in terms of their success at finding what they understood to be such features. In early 1925, for example, the New York Times critic Olin Downes (not himself a modernist) scolded Still for experimenting with modernist effects in From the Land of Dreams, thus by implication abandoning Downes's expectations: "Is Mr. Still unaware that the cheapest melody in the revues he has orchestrated has more reality and inspiration in it than the curious noises he has manufactured?"[5] (Still followed From the Land of Dreams a year later with Levee Land, a self-styled "stunt" that brought the blues singer Florence Mills to the concert stage, creating a sensation in which his point remained unremarked.) Downes's expectations of "exotic folksong and popular rhythms" in his review of the 1949 production of Troubled Island is a much later expression of the same practice.[6] It would seem that the challenge of composing concert music that was "recognizably Negroid" and at the same time avoided popular and commercial stereotypes was one reason Still turned away from his short-lived "modernist" phase of the early 1920s to focus on making his already-present "racial" expression more obvious. Still's self-characterized "racial " period lasted until 1932, but he continued to write pieces with "racial" features long after that date.[7]

The first performances of the major works from Still's racial period, the Afro-American Symphony and the ballet Sahdji, took place in 1930 and 193 1. These performances, which were given in Rochester, were covered

by critics whose comments also reflected race-based expectations. For example, Emanuel Balaban's report to Modern Music (the "little magazine" of the musical modernists) on the premiere of the Afro-American Symphony rejected the idea that Still had composed an "acceptable" symphony, insisting instead that it was merely a "suite" and stressing the work's simplicity, sincerity, and use of "racial color," qualities safely attributable to an African American composer.

William Grant Still's Afro-American Symphony would be more acceptable had he called it a suite. It is not cyclical nor symphonic in the accepted sense. Rather does it make use of dance forms. . . . The work is quite simple harmonically; in instrumental color typical of Still at his best. He derives extraordinary color with the scantiest of means, color that is essentially racial. Sincerity and naivete are among the most important elements in his work.[8]

Balaban's report was merely wrong and stereotype-laden. It did not contain the vituperation the same symphony attracted a few years later, when it was performed in New York City.

New York-based modernists wrote about the Afro-American Symphony in late 1935, after it was presented by the New York Philharmonic. Marc Blitzstein reviewed the 1935 performance for Modern Music . He attacked the symphony on ideological grounds, criticizing Still's "servility, . . . [his] willingness to debauch a true folk-lore for high-class concert-hall consumption," thus turning the Afro-American Symphony into something "vulgar."[9] The delay of four years between the Rochester premiere and the New York performance may have affected Blitzstein's reaction, as will be seen below in the discussion of the Composers' Collective. Soon after Blitzstein's diatribe, Aaron Copland wrote disdainfully of Still's music in general:

William Grant Still began about twelve years ago as the composer of a somewhat esoteric music for voice and a few instruments. Since that time he has completely changed his musical speech, which has become almost popular in tone. He has a certain natural musicality and charm, but there is a marked leaning toward the sweetly saccharine that one should like to see eliminated.

And of a piece that Still had striven to make "modern":

There is the "naive" kind [of American music] such as William Grant Still's . . . often based on the slushier side of jazz and mak[ing] a frank bid for popular appeal. . . . [O]ne can't help wishing that their musical content were more distinguished.[10]

These remarks by Copland long irked Still, for their effect was to dismiss Still's efforts at crossing race- and class-related barriers of genre as merely profit oriented and sentimental.[11]

In between the symphony's 1931 premiere and its first New York performance (1935), the Composers' Collective, affiliated with the Workers' Music League, an arm of the American Communist party, was formed by some of the New York modernists.[12] The collective's composers, including Blitzstein (the group's secretary), attempted to compose music that would appeal to the masses. (Still, who had used folk materials for years in his concert music, must have seen this as an attempt to reinvent his example, one that was not acknowledged by the composers of the collective.)[13] After the Composers' Collective's efforts to write new songs for workers to sing had ended in failure and the collective itself had dispersed in the late 1930s, folk song was adopted by the American Communist party as a means to promote its revolutionary ideas. A part of its Popular Front approach, the party's position coincided with wide interest in folk music and New Deal support for the arts.[14] Blitzstein's scathing attack may have been less a personal matter than an exercise in the application of party policy, uncritically borrowed from the Soviet approach to the folk musics of its various republics and not thought through in terms that fitted the racism of American society.[15] At about the same time, for example, Marian Anderson was attacked in the pages of New Masses for her recordings of spirituals that were "lacking the requisite rhythmic fire," "far too polite for comfort," and "castrated replicas of the original."[16] For Still, Blitzstein's and Copland's critical attacks in the pages of Modern Music constituted more attempts to circumscribe his creative voice and tell him how he ought to compose. They represented a pernicious old stereotype dressed in new, left-wing clothes. As a prominent African American, Still was seen by the party as an attractive potential recruit. His experience with the members of the Composers' Collective, however, may well have reinforced him in his decision to reject any overtures he may have received from the party.

In the early 1940s, many creative artists who had been drawn to communism as an expression of their "idealism and humanitarianism," in Zuck's words, became disillusioned and either left the party or ceased to cooperate with it. While some African Americans remained loyal to the party publicly, others became seriously disenchanted. The prominent Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay had articulated his objections in 1937. I quote them here as a likely statement of Still's position as well:

(1) I reject absolutely the idea of government by dictatorship, which is the pillar of political Communism.

(2) I am intellectually against the Jesuitical tactics of the Communists: (a) their professed conversion to the principles of Democracy . . . ; (b) their skulking behind the smoke screen of People's Front and Collective Security . . . ; (c) their criminal slandering and persecution of their opponents.[17]

Particularly relevant for Still, a steadfast integrationist, was McKay's view that, Popular Front and party claims to the contrary, the party really advocated black separatism: "Negro Nationalism in the United States . . . is the brain child of the American Communists and the real Negro nationalists are the Communists. They have advocated the creation of a separate Negro state within the American nation."[18] Along with his own experiences in the world of concert music, the position stated by McKay was at the heart of Still's anticommunism and of his plot theory as well.

The comments by Blitzstein and Copland marked a general change in the critical reception of Still's work at least from 1936, the end of the period when his music, though it often drew stereotyped critical responses, regularly attracted critical admiration as well. In the mid-1930s it was the modernists who rejected this music; by the mid-1940s the attitude had become more general. By 1946 Olin Downes had arrived at a formula for discussing Still's music that conflated the class-based genre barrier with the frankly racial one:

The composer's expression is diluted in a way that deprives it of racial essence. . . . Years ago we heard music by Mr. Still, of a exoticism and imagination that recompensed considerably for the immaturity of its workmanship. . . . [Now, Still] appears to have smoothed out as a composer—conventionalized. This is unfortunate. It is to be hoped that in later scores Mr. Still will return to what hide-bound academicians might call the original error of his ways.[19]

Troubled Island was premiered in 1949, eight years after its completion and eight years after the campaign for a production began. Following a rejection from the Metropolitan Opera, the campaign paused during the early years of World War II and then centered on the infant New York City Center for Music and Drama, which organized its own opera company not long after the war ended. It became a liberal cause célèbre in

which librettist Langston Hughes's high visibility on the left played a role, as did Eleanor Roosevelt and New York's Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. In 1944 Still wrote about the opera to Leopold Stokowski, who had conducted several of Still's orchestral scores and was in his first year as conductor of the New York City Symphony, a one-year-old arm of the City Center for Music and Drama. Stokowski was enthusiastic, leading Still to expect a concert performance in the 1944–1945 season, to be followed by a fully staged production the following year.[20] That plan ended because Stokowski's association with the symphony lasted only one season; he left without conducting an opera. Nevertheless, the company continued to indicate an interest in producing the opera. Newbold Morris, board chairman of the City Center of Music and Drama, Inc., wrote to contributors to a "Troubled Island Fund" on July 8, 1946:

I am writing to advise you that since Leopold Stokowski has left the City Center, we have recommended that this great opera by William Grant Still be included in the regular repertory of the New York City Opera Company during the 1946–1947 season. Mr. Halász, director of the Opera Company, feels that this production should be presented because we have not yet given to the public the work of an American composer.

This was not the first plan for producing the opera, as the next paragraph suggests:

It is felt that this method of presentation would be a distinct advantage over our original idea of producing the opera all by itself. It will give an opportunity to music critics and music lovers to hear this work and then, of course, if the response is what we hope it will be and impressive financial interests are attracted to it, it might be possible to send it on tour throughout the country.[21]

More delays and a further lowering of expectations ensued.[22] There was plenty of time for both composer (Still) and librettist (Hughes) to get discouraged and grow suspicious at the convoluted and seemingly endless process. Toward the end of this difficult period, Stokowski's own negative experience with the City Center may have encouraged Still's suspicions: "My experience with them was far from good. Confidentially, I would be careful with them if I were you."[23] Through the years of waiting, Still clung stubbornly to his faith that the intrinsic quality of his work would eventually overcome the obstacles. The hoped-for result would not only be a production of Troubled Island but also a fundamental breakthrough in race relations in America—an aspiration he

had once attached to the Afro-American Symphony . When he was finally sure that the opera would be produced, he wrote, "I pray that the opera will be done successfully. Fears arise. I've waited thirty-seven years for it. All is in God's hands."[24]

The opening night audience gave Troubled Island a prolonged ovation; Still took twenty bows. This memorable outpouring was offset by the critics' lukewarm reception. In particular, Olin Downes's review in the New York Times began by addressing Still's crossing of genres, starting with the opera's "cliches of Broadway and Hollywood" and complaining that "very little is new." Toward the end of the evening, in the market scene that opens the last act, Downes found a hint of the racial stereotype he had expected, a clear representation of "exotic folksong and popular rhythms." (Perhaps not coincidentally, the scene includes extraneous sexual byplay, which, also not coincidentally, Still removed in a later, unperformed revision described below.) Only in the small print did he grant Still's gift as a composer of opera who had created "a structure of considerable breadth and melodic curve." Other reviews in the white press followed Downes's model. Two additional performances, scheduled before the season began, did not change the critics' minds.[25] Returning to Los Angeles after the intoxicating experience of the premiere, Still anticipated Voice of America broadcasts of the dress rehearsal, which had been recorded for that purpose.[26] He also set about revisions in preparation for another production, for several possibilities had been mentioned.

Troubled Island is about the Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessa-lines, who was murdered in 1806. In Act I, as the revolution is about to begin, Dessalines is treated as the hero-to-be. In Acts II and III, he is portrayed as the emperor of Haiti, debauched, illiterate, and unable to govern. Finally in Act IV he is murdered by his erstwhile followers; his first wife, abandoned in the years of debauchery, returns to sing a final aria over his body.

So convinced was Still that there would be further productions that he set about a revision that would give the denouement more weight, bringing the tragedy of the hero's high early aspirations and his subsequent destruction into more telling perspective. In the market scene that precedes the assassination, Still removed the lighthearted give-and-take

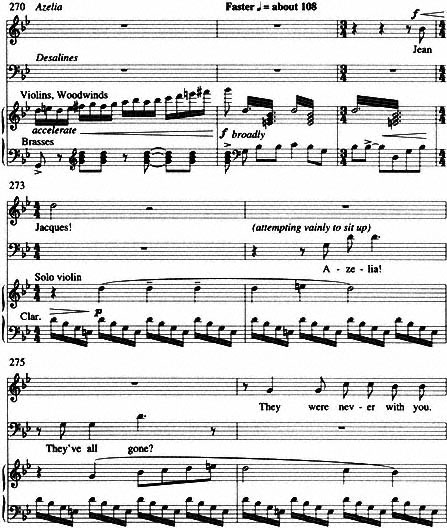

Example 7.

Excerpt from the revised version of Troubled Island, Act IV, final

scene, words added after the 1949 premiere performance at the New York

City Opera. Underlying chords in the strings in an eighth note—dotted quarter

pattern from measure 273 on are omitted from the piano-vocal score.

Copyright 1976 by Southern Music Pub. Co., Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Example 7.

(continued)

that had attracted Olin Downes's approval as suitably "exotic," deleting an exchange between a female fruit vendor and a fisherman of the chorus and substituting repetitions of text already sung for the excised words. The deleted text, sung by the fruit vendor and echoed by the chorus, includes this couplet:

Out of my way and let me pass!

All men's tongues are full of sass!

In the revised closing scene, Azelia (the abandoned first wife), comes upon Dessalines as he lies fatally wounded (but not, in this version, dead)

from the assassins' attack. This is part of the text (supplied by Verna Arvey) that Still interpolated to follow Azelia's discovery of Dessalines:

| ||||||||||||||||||

The text was added to a passage that was purely instrumental in the production.

Presently it became clear that none of Still's expectations for further performances and productions would be realized and that his opening night triumph had led to nothing. As his disappointment grew, he came to believe that the cause of these nonoutcomes lay with the unfair reviews by the New York critics, especially Downes, whom he had once counted as a supporter. The revised ending of Troubled Island, devised to enhance the power of the closing scene with a minimum of change, reflects his feelings. "They were never with you," one of the lines supplied by Arvey in this revised ending, takes on added meaning in the real-life context of fear and suspicion that had begun in the campaign to achieve a production.[28]

After the Troubled Island production, Still became increasingly withdrawn. A sense of preoccupation and distance from his fellows had been a characteristic of his demeanor even in 1930; in his later years, it was carried to an unhappy extreme. He believed, as does his daughter, Judith Anne Still, to this day, that a communist-inspired conspiracy produced the destructive reviews and robbed him of the recognition that was his due. She recalls from her childhood (age seven):

My father returned from the New York production wrenched by disappointment. I remember how he looked in his long, charcoal grey overcoat and brown, wide-brimmed hat, wearily taking his suitcases out of our '36 Ford after we had brought him home from the airport. . . . He took out the little notebook in which he always jotted down notes when he did not have my

mother there to remember things for him, and he glanced through it. "Well, Verna," he said, "I just don't know. I just don't know what to say."[29]

She describes her father reading from the little notebook, telling of a pre-performance visit to his hotel room by the Times drama critic Howard Taubman. Taubman, she reports, warned Still that the white critics had decided "the colored boy has gone far enough" and that the production would be panned. An inquiry by a New York singer friend drew the reply, "You know we're only going to let just so many Negroes through."[30] She believes the notebook may survive, though it remains unlocated.[31] Judith Anne Still's often-repeated personal testimony, which should not be dismissed out of hand, and that of her parents remain the strongest evidence for a specific plot to deny Still an unqualified operatic success.

One may track the development of the plot theory in Still's diary in the months following the production. On first hearing the recording made by the State Department for foreign broadcast, he reacted negatively to what he had heard on musical, not political, grounds, perhaps reflecting a postproduction letdown: "June 14 . . . Got dubs of records. Disappointed. Halász did a very poor job as director. Winter's amateurish. Some others not satisfactory."[32] Later, after the Voice of America recording had been broadcast in Paris and Brussels, the State Department recalled the recording and advised Still that it was "mauvais."[33] Stokowski's comment, "I am afraid there has been some intrigue going on against your Troubled Island, " refers to this incident.[34] The plot theory appears full-blown in Still's diary in October 1949, some five months after the production: "Disquieting news re the persecution we are receiving from the Communists. Unfortunately we cannot tell people of this because they would not believe us. Only God can help us. I believe He will."[35] Lumping the New York critics (especially Downes) with the modernists, Still wrote that he was "downcast over attitude of the so called 'musical intellectuals' toward My Music."[36] By the following February, he concluded sadly, "I marvel on listening to the records of [Troubled Island ] at the critics' reaction. But they were biased for several reasons. I hate to be forced to admit that racial prejudice entered into it."[37]

Still summed up his view about the coterie that opposed him in a letter to Howard Hanson that discussed the State Department's withdrawal of the recording from radio stations in Europe in August 1950: "Although I have recognized the fact that you, and I, and other American composers have had strong opposition for years, this is the first legal

evidence I have had, outside of a number of disparaging clippings written by members of the clicque [sic ]."[38]

Still had started to speak out against communist exploitation of racial issues and recruitment of African Americans for the communist cause after the canceled production of 1946. To begin with, he published "Politics in Music" in a small southern California music periodical. After a slap at the "cerebral pseudo-music" of unnamed modernists who had, through intrigue, "done American music . . . a grave disservice," he distanced himself from the "many who subordinate their art to [communist] political propaganda," and named Paul Robeson and Earl Robinson as examples of the "many." He wrote of his own refusal to allow himself or his name "to be used indiscriminately by political left-wingers" and concluded, "I believe that most of us in the arts are liberal, but not Leftists. I believe that the American tradition itself is liberal. . . . Some Americans have chosen to make their liberality the servant of a foreign political ideology. . . . [S]uch a choice is not mine." In support of his argument, he made the point that his outspoken protest pieces from the early 1940s had been commissioned and performed under the current social and political order, without the need for a violent revolution to enable him to speak. He asserted that, contrary to party claims, he had artistic freedom under the current system: "I thought back to two of my own compositions which were strongest in protest against existing conditions (And They Lynched Him on a Tree and Plain Chant for America ) and remembered that both of them were initiated by a member of what is called our capitalistic class, the poet Katherine Garrison Chapin."[39]

Three years later, he continued this theme in "Fifty Years of Progress in Music," a more widely distributed essay citing several African Americans (Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, Marian Anderson) who either had reversed or were helping to reverse the stereotype that "Negroes were talented only in folk or theatrical music." He wrote of the effort that white symphony conductors had to make to hire African American musicians in the face of rigidly segregated musicians' unions; of the one black impresario in the United States (M. H. Fleming of Salt Lake City); of the tremendous success and worldwide influence of jazz as opposed to the ban against black singers at the Metropolitan Opera and the continuing difficulty that African American composers of concert music had gaining recognition. Turning to his recent experiences with Troubled

Island, he described the even higher barriers faced by black composers when they undertook to get an opera produced. For the first time, he publicly attacked two white modernist composers as enforcers of a communist-inspired, aesthetically doctrinaire strategy with racist as well as political implications:

It is a fact that there is in New York a powerful clique of white composers who exclude all others, white as well as colored. . . . it is interesting to know that Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, the leaders of the clique, were also publicized in Life magazine's April 4, 1949, issue, in an expose of "Dupes and Fellow Travelers." The connection is all too obvious!

Having refused to follow Leftist doctrines, certain colored and white composers have been opposed by this clique for many years. Among other things, the door to adequate recordings of our music—always a sore spot—has been closed to us. Thus the New York clique had made a totally unnecessary obstacle for many of us—an obstacle that has wider implications than the merely racial or personal.[40]

In 1951, Still was reported by the Hollywood Citizen-News as having asked to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.[41] The following year, he wrote at length to the Arkansas Gazette, not to name names this time, but to set forth his earnest conviction that the Communist party had no program to improve race relations in the United States and to cite evidence that the party had actually proposed (some years earlier) further segregation of the races as a solution.[42]

In May 1953, he read a potentially incendiary speech to the San Jose, California, Chamber of Commerce. This time he neither argued the communist position on race relations nor settled for naming a couple of people who had sold out to a foreign power or were part of a politically motivated music conspiracy. The typescript of his remarks is entitled "Communism in Music." Some excerpts:

Although America has not been taken over by the Soviets in fact, it is true that Moscow has had a subtle but effective hand in our arts for many years. . . . [I]n no instance am I accusing any American citizen of being a Communist, because I am not in a position to say who carries a Party card and who does not. . . . I am able to mention a series of coincidences, backed up by printed documentation, and ask the reader to draw his own conclusions.

Still's list of those who furthered Moscow's "subtle but effective hand" is long, varied, and deserving of skepticism. Roy Harris is named for dedicating his Fifth Symphony to the Soviet Union; Aaron Copland, for allegedly being a member of twenty-eight communist-front groups. Also named are Leonard Bernstein, Serge Koussevitzky, Olin Downes, Marc

Blitzstein, Newbold Morris (board chairman of the New York City Opera), and Kurt Weill. For good luck, perhaps, he named some others "whose names appear on such lists [of un-Americans] regularly": Larry Adler, Dean Dixon, Morton Gould, Earl Robinson, Margaret Webster, Garson Kanin. Even his old friend Henry Cowell, whom both Still and Arvey had stuck by all through the San Quentin years, is mentioned.[43] In addition, Douglas Moore, Oscar Hammerstein II, Ira Gershwin, and Hanns Eisler are named, along with the sponsors of a concert of Eisler's music: Copland, Bernstein, David Diamond, Harris, Walter Piston, Roger Sessions, and Randall Thompson. On the other side, he gave a much shorter list of composers whose work had been intentionally shut out: Charles Wakefield Cadman, Deems Taylor, and Paul Creston were named as loyal white American composers. In addition, Still reported, "On one occasion, I was made so uncomfortable in a studio job that I resigned, only to have my place taken by a known Communist." At the same time, he emphasized that his primary concern was race-based:

Here, a word must be said concerning the part played in all this by the racial angle. When the communists decided to take over America, they also decided that American Negroes would be their shock troops and lead a revolution for them. American Negroes have thus been under great pressure but, speaking in general terms, they have not as a whole fallen in with this plan. However, the pressure on them still continues, and any Negro leader who dares to think for himself is a target of special attention. So, both musically and racially, my work has been opposed.[44]

In reading the speech, Still omitted these sentences by Arvey: "In the final analysis, Party membership may be only a technicality. The big question is: to what extent have certain musicians used their talents and their positions to further the aims of Soviet Russia?" Though Still did not identify his informant, he added his story about Howard Taubman's preperformance visit and warning. He also remarked on Newbold Morris's role in the firing of László Halász, the music director who had chosen to produce Troubled Island, and (erroneously) the subsequent decision to produce a work by Kurt Weill, whom he added to his list of communists.[45] Neither Still nor Arvey changed their minds in later years; this speech, however, marks the end of Still's career as a public speaker on the issue of anticommunism.

One returns to the following overriding questions. Why did Still come to a conspiracy theory to explain the critical reception of his music (es-

pecially Troubled Island ) and the lack of recordings of his music? After all, many an opera by an American composer has sunk into the unmarked depths after a few performances, certainly some that may not have deserved that fate.[46] Why the anticommunist position that laid the "failure" of Troubled Island on this doorstep and so soured both Still and Arvey toward much of the concert music establishment, especially considering that Still's concern with the racial issue is evident throughout? My purpose here is to understand how Still came to the conspiracy theory and to anticommunism, both of which are difficult to accept.

Other incidents, in conjunction with political developments, probably reinforced Still's perception of a pattern of communist-inspired racial persecution that he began to dwell on as the Troubled Island production developed. Noisy competition among political factions suffused the Hollywood film colony in the 1930s and 1940s. The rise to power of the leftist Screenwriters' Guild by 1940 was countered by the 1944 formation of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, organized by film producers to "combat what we regard as a growing menace within our own industry of Communists and to some degree Fascists."[47] After years of shrill political debate (fanned in part by the intransigently antiunion Los Angeles Times ), the 1947 hearings on alleged communist influences in the Hollywood film colony may have predisposed Still toward his anticommunist position. It may have led him to wonder whether his treatment at the hands of Twentieth-Century Fox over Stormy Weather had been politically motivated. (In 1943, Still resigned from a lucrative studio contract, partly because he disapproved of the image of African Americans projected in Stormy Weather, the film he had been signed to work on and the "studio job" mentioned in the 1953 San Jose speech.)[48]

Circumstances surrounding the premiere of Still's choral ballad And They Lynched Him on a Tree in New York City in June 1940 may also have fostered Still's developing sense of distrust, even though (or even because) its positive critical reception showed no obvious sign of the pattern I have described in connection with the Afro-American Symphony and Troubled Island . Still learned a few days before the premiere that another new work calling for roughly similar performing forces, Roy Harris's Challenge 1940, would be performed at the same concert. Many years later, Arvey wondered aloud how Harris, once a member of the Composers' Collective, had managed to push his way onto this program and deflect some of the glory away from Still. The presence of Paul Robeson and of Earl Robinson's music, which Still knew about in ad-

vance, added to the surprise presence of Harris's music, may also have left Still feeling used by these leftist composers.[49] Still had been aware earlier of conductor Artur Rodzinski's concerns about programming so timely and controversial a text as Still's piece employed. He probably never knew, however, that Rodzinski had commissioned Harris for another new work that would focus on a more traditionally patriotic and therefore "safer" topic. Because he did not go East for the concert and it was not broadcast in Los Angeles, he was unaware of how negligible Harris's contribution actually was.

With And They Lynched Him on a Tree, premiered in New York City in 1940, not only Still's highest aspirations for his music but also his single strongest public expression in music about racial oppression had been, as both Arvey and Still viewed it later, co-opted at its premiere by the left. Still's absence from the performance may have bolstered a sense of helplessness in the shaping of distant events. He may even have attributed the warm critical reception his own work received to the presence of music by Robinson and Harris, both of them far to his left, on the program. The feeling of co-optation became increasingly uncomfortable, at least in hindsight, for a man who was convinced that the Communist party was cynically exploiting racial violence in the United States with no program or expectation of improving the situation.

Another incident that may have influenced Still's thinking about communism cannot be dated. Judith Anne Still reports an occasion when her father was invited to a meeting in an "elegant apartment" where he was promised support as a composer and urged to become a party member as some other prominent African American artists had done. Langston Hughes was in Los Angeles in 1939 to work with Still on Troubled Island . Judith Anne Still suggests that Hughes arranged such a meeting at that time. Whenever it happened, the result seemed to be to create suspicion rather than interest on Still's part. The coolness that developed between Still and Hughes, which became public shortly before the opera's 1949 premiere, resulted in part from Hughes's departure for the Spanish Civil War before the Troubled Island libretto was completed to Still's satisfaction, but it may well have fed off their increasing political differences as well.

The situation with the New York City Opera beyond Still's previously described negotiations may also have encouraged the plot theory. Newbold Morris, the official who was the liaison between the City of New York and the opera company, was heavily involved in politics and often a center of public controversy because of his position with the city.

Among the board members and those on the "Troubled Island [fund-raising] Committee" was Claire M. Reis, longtime administrator of the League of Composers. Though the league had commissioned Still and given him early performance opportunities, it was also the sponsor of the journal that had led the critical attack on his work, Modern Music . Reis, who functioned as secretary of the opera board and had been one of the original donors, appears to have favored board involvement in artistic decisions, something that appears in Martin Sokol's account of Halász's firing in 1951.[50] Divisions and politicking on the board were, apparently, well reported in the press, a situation that may have encouraged Still's dissatisfaction.

Around 1950, Still's income began to diminish. His fellowships (a Guggenheim, twice renewed, followed by a Rosenwald, renewed once) had long since run out. Commissions for new works and opportunities for commercial work likewise dwindled. He ascribed the problem to the conspiracy: "Funny that people think we have money when on the one hand I am denied employment in the movie studios as a composer, and on the other the intellectual & Communist musical people (who are in control) keep us from getting recordings and performances. They would have me starve."[51]

None of the concerns I have mentioned—the stereotyping of his concert music throughout his career, the critical treatment of the Afro-American Symphony, the performance circumstances of And They Lynched Him on a Tree, the controversy over the music for Stormy Weather, the politicization of the New York City Opera, disappointment over the curtailed European broadcasts of Troubled Island as well as its critical reception in New York, even the loss of paying work—seems to be serious enough to warrant Still's increasing suspicion and his conversion to the communist plot theory in itself, let alone his public espousal of these positions. Yet, taken together, and given the atmosphere of mystification and manipulation that surrounded the activity of the party,[52] one can see why someone in Still's position might well have discerned a pattern of obstructionism. Certainly one can recognize the desperation and the suggestion of paranoia in Still's journal entries quoted above over the months following the production.

One may infer that Still's anticommunism was the end product of a line of reasoning that his experience as a composer of concert music led him to ascribe to his critics: he was an African American, and African Americans were by stereotyped assumption considered not capable of composing in elite "higher forms." Hence the evaluations by white crit-

ics and composers that he was not really composing in the "higher forms" at all but must be writing commercial music. If that was the line of reasoning that led him to attack stereotyped, race-based expectations of his music, the reasoning he apparently applied in arriving at his anti-communist position formed a parallel, equally weak syllogism: Still composed (for whatever reason) conservative, less dissonant music and was himself politically conservative. The composers of the "New York clique" wrote more dissonant music, and many of its members or associates had flirted with communism, perhaps even joined the party, and had certainly espoused more liberal politics than he. Therefore dissonant music was part of a communist plot to undermine American music, and critical attacks on his music were a part of this plot. One of the ugly aspects of the anticommunist movement around 1950 was that "communist" was sometimes understood as a code word for "Jewish" and/or "homosexual." The homophobic and anti-Semitic implications here problematize the Stills' position even further. Still's African American identity made him a very visible composer of concert music who had long been a target for recruitment by the party. However alienated he had become from Copland, Blitzstein, and Harris et al., he had once been a New York modernist himself. He had once been grateful to Downes for addressing his work at all; now he was frustrated that Downes and other critics would not outgrow their racially stereotyped views of his music. His connections with Hollywood might have served to make him even more of a target of the anticommunist witch hunt. In addition, Arvey's heritage was Jewish. Her uncle, Jacob Arvey, occupied a prominent position in the Democratic machine that controlled Chicago politics; Uncle Jake's record of opposition to communist-controlled unions might not have protected either him or his relatives from what was, among other things, a partisan political movement.[53] Still may thus have acted in part out of concern and support for Arvey. He granted the role of generic racism in what he had come to see as the Troubled Island debacle only in a moment of despair, months after the fact; it must have been less painful for him to perceive the "failure" of that production as contrived by a specific coterie than to see himself as a helpless victim of institutionalized racism. Under these circumstances, the flawed reasoning evident here may have had much less to do with Still's actions (and Arvey's) than with the fact that Still was culturally positioned in a way that left the path he chose as the one least objectionable. Perhaps the final irony of his entire involvement with anticommunism was that the McCarthyite movement rent American society in an excruciating way, one whose

scars remain visible; yet, except as a more or less theoretical civil liberties issue, it did nothing whatever to address the issue of racism. All it did, on either side, was to distract attention. Still's anticommunism—by far his most controversial public position—was thus irrelevant to his principal cause, which was to end racism.

If I have indeed tracked some of the reasons for Still's early perception that the radical left had no sympathy for his artistic aspirations and no agenda to improve race relations in America, and if the critical attacks on his music in the 1930s and later were partially motivated by doctrinaire political considerations, as now seems entirely possible, it may be necessary to rethink the charge of "paranoia." It must be remembered here that, despite the apparent opposition suggested by the term "anticommunism," the issue was never a simple question of "communists" versus "anticommunists." The crude polarized language that marked this movement fostered confusion at the time and continues to complicate discussions. The outspoken "anticommunists" were a relatively small group who shared right-wing, nativist views. They labeled many more liberal Republicans and Democrats, most of whom had long opposed the Communist Party, as "communists" or "communist sympathizers." It is now clear that many careers were destroyed by the extreme anticommunism of the McCarthy era. It is also clear that the party attempted to destroy the careers of prominent writers and artists who left it (e.g., Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright). We also know that critical judgments of artistic production have often been based on nonobjective criteria and that racism was pervasive among both liberals and conservatives. One could claim that Still was as much a victim of those battles as a participant. Such a claim has the advantage of insisting on the complicated contextual web in which Still took his position but denies Still's agency as an individual capable of making his own decisions. Whatever the whole story may be, individual paranoia is not a satisfactory explanation.

Whether there was a conspiracy or not seems less important at this point than that Still firmly believed that there was one and that he acted on that belief. Like his long-standing conservative politics and his often-stated belief in God, anticommunism became a way to confront and separate himself from the white liberal establishment that had both supported and thwarted him for so long. Forsythe's insight (perhaps gleaned from his conversations with Still) presents an aspect of the modernism that Still came to oppose at such cost and is relevant here despite

its incompleteness: "The intellectualism of modern music is more psychopathic than has been generally understood."[54]

Yet racism remained Still's principal issue. In the early 1940s, Arvey had written,

Very few people regard racial matters as a vital topic in this war. How wrong they are will only be seen after the war is over, and perhaps even before it ends. We who are close to the heart of the matter know that is one of the chief reasons for the war and, after it's all over, this will be seen as a major objective. It's one of the necessary topics.[55]

Jon Michael Spencer has recently documented Still's continuing statements against racism, showing them to form a long-standing and consistent pattern.[56] Nevertheless, in the late 1950s and 1960s Still's public position as a McCarthyite remained unchanged.

The complexity of the situation in which the racial issue and Still's creative efforts were repeatedly submerged in other, irrelevant issues provides a background for the arguments about racial separation and integration that arose afresh in the 1960s. Not least among the ironies of Still's anticommunism is that in the twilight of his career he wound up in bitter opposition to the Black Power and Black Arts movements. Still had long been committed to racial integration, and he did not change his position; yet his difficulties in keeping the focus on the racial issue almost seem a textbook argument in favor of separatism, a doctrine he had addressed in another context decades earlier, in the course of his racial period. Yet a great part of Still's musical utterance had addressed the development of an authentic African American voice for concert music where there had been almost no such voice. It appears that he had hashed out the issue, probably not for the first time, with his Los Angeles friend Forsythe, who in 1930 was the first to write at length about Still's work. Forsythe ascribed the "dark-heart" to Still and celebrated Still's compositional achievements with the insights and the resolve born of his own struggle to produce literature and music that might reflect his own identity as an African American.[57] The upshot was that Still rejected the principle of black separatism along with Forsythe's rhetoric, but not, where his music was concerned, the practice of self-conscious racial expression. His resistance to the prescriptions of the Black Arts movement of the 1960s simply repeated the position he had reached in his discussions a generation earlier with Forsythe and elsewhere. Since then, the

practice of ignoring middle-class African American cultural contributions has militated against knowledge, let alone acceptance, of Still's life and work by a wide American or African American audience.[58] In what seems the greatest irony of all for the composer of Africa and the Afro-American Symphony, the Black Arts movement saw Still's great "classical" aesthetic experiment as irrelevant, if they knew about it at all.[59]

Still's use of African American materials embodied a different approach from that of white composers, carrying the potential for subverting or even upsetting the racial status quo. Who might present "black" musical ideas as concert music and in what format and to what audience were clearly at issue as Still (and other African Americans) entered the arenas of concert music and opera. Still addressed this issue directly in his work.[60] The critical reception of Still's music as too commercial, even too polished (however ironic in view of his early struggles to master his art), suggests that his long-term efforts were indeed successful at raising questions about the artificial barriers of genre that mirrored racial distinctions, that he was occupying new ground, opening an unfamiliar and not entirely welcome territory. The critical misunderstanding he attracted suggests that his challenge to a wide array of cultural stereotypes met with resistance, however poorly articulated, from both races.

It is worth remembering here that Still participated in not one but several transformations of the blues, including not only the "uplifting" transformation found in the Afro-American Symphony but also W. C. Handy's earlier metamorphosis of blues from a folk practice to the commercially viable (and sexually suggestive) "classic" blues of the 1920s and even Paul Whiteman's "sweet" synthesis of blues and jazz for large orchestra. Still's racial doubleness figures in each of these changes. Hindsight locates Still in the role of the mythical West African trickster, a figure he may not even have known about, as his career evolved.[61] The self-consciousness with which he went about his compositional practices, his contrasting and complementary double personae as modernist and Harlem Renaissance man as well as the multiplicity of adaptations of African American cultural practice he experienced in the crucibles of Harlem and Broadway, make this a valuable insight. His response to the reception of From the Land of Dreams in 1925 had been to offer Levee Land, featuring a blues singer performing the blues to a "modern" accompaniment, to the same audience the next year. As we have seen, the Afro-American Symphony contained its own response to white commercial borrowings from African American folk music. His firing from Columbia Pictures in 1936 for inserting "The Music Goes Round and

Round" into a rehearsal of a quiet passage for the film Lost Horizon was surely a tricksterish gesture as well. It is possible, too, that the social change of the 1960s involved at last one too many adaptations for a single human being to negotiate. How does one accommodate to a cultural change that appears ready to bury one's entire creative output? (Close analysis by other scholars may show that, in his music, he did negotiate it.)

Still's anticommunist position hints at how complicated his chosen path was. His identification as an African American who confounded a range of sometimes conflicting popular stereotypes—raised in an urban Southern environment in a tight-knit family with aspirations to uplift the race; active and successful in the separate, culturally opposed worlds of commercial and concert music; more the modernist and Harlem Renaissance man than he would have cared to admit, self-exile notwithstanding—assured that his aesthetic synthesis would be a unique and valuable contribution to American culture. The uniqueness of Still's creative path meant that even when audiences received his music warmly, as they often did, his formal and technical achievement would go largely unrecognized. There was little room for this experiment, for the inflections of class distinction and racial expressivism that were essential features of Still's art, in the fierce and reactionary political and social binarisms of the 1950s. In this light, Verna Arvey's aphorism, "they were never with you," takes on a far richer meaning. When it comes right down to it, they—whoever "they" might have been, then or now—were probably never entirely against him, either. They just didn't, and don't, know quite what to make of him. By now, we may be ready to rethink the person and rehear the music.