One

The Golden Age of a Corporation, 1855-1885

One gas engineer, in a rare show of wit, remarked that the eighteenth century may have been the "age of enlightenment," but the nineteenth century was shaping up to be the "age of light."[1] That engineer was commenting on one aspect of a general revolution in everyday comforts: nineteenth-century Parisians, like other urban Europeans, expected— even demanded—to be taken out of the nocturnal obscurity that had seemed inevitable for millennia. Rising standards for lighting touched the public thoroughfares and the home. Better illumination was perhaps one of the created needs that an increasingly commercialized society foisted with accelerating and unrelenting pace on innocent consumers. Nonetheless, effective street illumination became a symbol for improvements in urban civilization and a sign, for those who so wished to construe it, of ineluctable material progress. Reassuring as gas lighting may have been to the public, it also became the source of big business and political contention. Regulating the new amenity in the public interest proved difficult in a France governed by liberal notables.

The Formation of the Company

In 1855, the Compagnie parisienne de l'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz was born and quickly developed into one of France's greatest industrial enterprises. It supplied at least half the coal gas consumed in France through the 1870s.[2] The firm was indeed an exemplar of the new indus-

[1] Le Gaz: Organe special des intérêts de I'industrie de I'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz, August 31, 1864, p. 108.

[2] Archives départementales de la Seine et de la ville de Paris (henceforth cited as AP), V 8 O , no. 269, "Usine des Ternes."

trial capitalism that was just beginning to transform the French and European economies. Its legal form, a limited-liability corporation, was still rare in a world of family enterprises and partnerships. The salaried managers who took charge had to coordinate processes across quasi-autono-mous departments and oversee the allocation of resources on a scale that was exceptional. Corporate assets of the Parisian Gas Company (PGC) grew from 55 million francs at the founding to 256 million thirty years later. Managers oversaw a factory labor force of forty-two hundred (in 1885), of which only a tiny fraction had attachments to the conventional crafts. Another new social type, the salaried white-collar employee, numbered 1,975 in 1885. By that time the PGC had become the ninth-largest enterprise and the largest manufacturing firm in France. Only transportation concerns and the Anzin mines were bigger.[3] The PGC also foreshadowed the rise of big business based on high technology. It is true that the production of coal gas was not in itself enormously sophisticated. It required only roasting coal in air-tight retorts and collecting the escaping gases.[4] Yet the necessary quality-control techniques as well as the transformation of residues into industrial chemicals fused applied science and enterprise in a particularly innovative manner.

The PGC was a private enterprise, but its operations necessarily entailed coordination with the public authorities. The precise obligations that the city of Paris imposed on gas producers and that the companies expected of the city were the subject of literally continuous negotiations, reconsiderations, and debate—often acrimonious—from the moment gaslights appeared on the streets of Paris before 1820. Here politics entered the picture. The public authority tried to safeguard the interests of both the community and consumers, and the two interests did not always coincide. At the same time, gas manufacturers, being powerful capitalists, sought the best possible deal for themselves and their investors. They had the ability to manipulate issues and confound the authorities by withholding expertise or limiting options. Conflicts of interest explain why the seemingly innocuous effort to put gaslights on the streets and into stores and homes engendered interminable and rancorous discussion.

[3] Bertrand Gille, La Sidérurgie franfaise au XIX siècle (Geneva, 1968), p. 295, ranks the thirty largest firms in 1881 on the basis of capital.

[4] On the early history of gas production, see Malcolm Peehles, Evolution of the Gas Industry (London, 1980); Trevor Williams, A History of the British Gas Industry (Oxford, 1981); Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century, trans. Angela Davies (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1988); Arthur Elton, "The Rise of the Gas Industry in England and France," in Actes du VI Congrès international d'histoire des sciences, Amsterdam, 1950, 2 vols. (Paris, 1953), 2:492-504.

The formation of the PGC is shrouded in some of the mystery that surrounds most other aspects of public administration under the rule of "the Sphinx," as Emperor Louis-Napoléon was known.[5] In place of fact a legend has arisen about the creation of an imposing gas corporation as a result of the bold entrepreneurship of those paragons of Imperial capitalism, Isaac and Emile Pereire. The claim has often been made that the PGC was one of their pioneering accomplishments, along with Europe's first industrial bank.[6] Their role in the making of the PGC was in truth peripheral and even parasitic. The PGC was formed from the merger of six preexisting gas firms following the wishes of their owners and the urgings of the public authorities. A single, powerful gas firm was a solution to the difficult problem of producing and distributing an urban amenity that was quickly becoming vital for some key elements in the population.

As a new industry in the early decades of the nineteenth century, gas faithfully traced the limits of scale set by technology, financial markets, and consumer demand. These forces at first imposed a relatively modest scale on gas producers, just as they did on forge masters and on textile manufacturers. In 1852 there were six gas concerns serving Paris and four more in the suburbs (in addition to one purveyor of bottled gas).[7] Neither the firms themselves nor the principal gas plants anticipated the large concentrations of capital that the PGC would eventually entail, as the figures in table 1 suggest. A major constraint on the size was the limited demand for gas within the circumscribed areas that their distribution systems could reach. Theoretically it was possible to produce huge batches of coal gas at a centralized plant simply by multiplying the number of retorts roasting coal. But the ability to deliver the gas to faraway customers effectively and at a reasonable cost was lacking. As the distance from the source increased, enormous amounts of gas were lost through leaks in the mains, and gas pressure at the destination fluctuated so widely as to make its use impossible. Thus, gas production became dispersed in modest-sized plants

[5] On the lack of public sources for the history of Paris under the Second Empire, see Anthony Sutcliffe, The Autumn of Central Paris: The Defeat of Town Planning , 1850-1970 (Montreal, 1971), pp. 335-336.

[6] Rondo Cameron, "The Credit mobilier and the Economic Development of Europe," Journal of Political Economy 61 (1953), 464; Theodore Zeldin, France, 1848-1945, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1973-1977), 1:82; David Harvey, Consciousness and the Urban Experience (Oxford, 1985), p. 80; Alain Plessis, De la Fête impériale au tour des fédérés (Paris, 1979), p. 104.

[7] On the pre-merger gas situation, see Journal de l'éclairage au gaz (1852-1855); Henri Besnard, L'Industrie du gaz à Paris depuis ses origines (Paris, 1942), chaps. 1-2; Frederick Colyer, Gas Works: Their Arrangement, Construction, Plant, and Machinery (London, 1884), chaps. 1-4.

Table 1. Assets of Merging Gas Companies and Principal Gas Plants, 1855 | ||

Value (francs) | ||

Firm/Principal owner | ||

Compagnie anglaise/L. Margueritte | 13,628,000 | |

Compagnie française/Th. Brunton | 10,824,000 | |

Compagnie parisienne/V. Dubochet | 5,739,000 | |

Compagnie Lacarrière/F. Lacarrière | 4,494,000 | |

Compagnie Belleville/R. Payn | 3,294,000 | |

Compagnie de l'Ouest/Ch. Gosselin | 2,021,000 | |

Gas plants | ||

Ternes and Trudaine | 472,849 | |

Vaugirard | 545,198 | |

Poissonnière | 464,182 | |

La Tour | 235,835 | |

Ivry | 353,208 | |

Belleville | 139,428 | |

Passy | 79,291 | |

Source: AE V 8 O1 , no. 723, deliberations of December 26, 1855, and October 30, 1856. | ||

in the midst of populous neighborhoods. No one firm was up to the task of serving the city as a whole. The Compagnie française, for example, served the present-day third and fourth arrondissements from a factory on the rue du Faubourg Poissonnière.[8]

The dynamism of nineteenth-century capitalism quickly expanded these limits. Improvements in the manufacturing of gas pipes and joints and the development of mechanical means for regulating pressure permitted the concentration of production. Moreover, the experience of the railroad companies paved the way for the accumulation of ever-greater amounts of capital through the sale of bonds, which tapped the savings of cautious and modest investors.[9] By the 1840s there was no longer any reason one large firm could not control the Parisian gas industry. That situation seemed all the more desirable since it was obvious that the industry was still in its infancy and would call for rare technological and

[8] AP, V 80 , no. 24, "Canalisation: Extraits des rapports et délibérations, 1834 1855"; Préfecture de la Seine, Pièces diverses relatives à l'éstablissement des con-duites pour l'éclairage au gaz dans Paris (Paris, 1846).

[9] AP, V 80 , no. 25, "Canalisation"; Charles Freedeman, Joint-Stock Enterprises in France , 1807-1867 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1979), p. 83.

entrepreneurial talent to handle the vast investments that would soon be necessary.[10]

Another impetus for merger came from the municipal authorities, who increasingly insisted on uniformity of marketing arrangements from the various producers. The introduction of gas services had immediately raised in Paris, as it did in all other large cities, the thorny problem of regulation in a liberal era. Private lighting had heretofore been a matter of individuals buying oil lamps or candles, but gas required sinking mains under streets, spurring concern for public safety. The authorities gradually (and reluctantly) arrived at viewing gas as a "natural monopoly" and then sought means to protect customers and derive financial benefits for the city. By 1822, when gas was still a novelty, the prefect had already given the companies exclusive rights to particular sectors of the city (though there were disputes over precise boundaries) and soon imposed the obligation to serve streets with a minimal demand. The city was not yet ready to set uniform gas rates, and there was as yet no set of uniform contractual obligations for gas producers. These would come with the agreement of 1846, which made gas into a regulated industry,[11]

With this agreement Paris established once and for all the practice of granting to a utility a monopoly for a fixed number of years. Later, some public figures would express their regret over the failure to follow the British example of creating perpetual utility companies, but the municipality would return repeatedly to a concession with limited duration. Most politicians agreed that this arrangement was in keeping with French custom.[12] The charter of 1846 gave the six gas companies a concession lasting seventeen years. Before this charter was in effect, prices for gas had varied from one firm to another, reaching as high as sixty centimes per cubic meter, but averaged forty-eight centimes. In the 1846 agreement, the companies undertook to charge forty-seven centimes and to reduce the price by a centime a year until the rate of forty centimes was attained. The firms would sell gas to the city for street lighting at the putative at-cost rate of twenty-four centimes. Furthermore, they agreed to pay certain duties and to sell the gas mains to the city at a low price when the concession ended as compensation for their monopoly.[13] With

[10] The companies were eager to merge partly to prevent competition and stop customers on border streets from bargaining for lower rates. See AP, V 8 O no. 751, "Affaire Deschamps."

[11] Besnard, Gaz à Paris, chap. 2.

[12] Procès-verbaux des délibérations du Conseil municipal de Paris (henceforth cited as Conseil municipal), March 8, 1881.

[13] Besnard, Gaz à Paris , chap. 2. Note that gas was sold mainly by the hour, not by volume, at this time.

the several firms at last adhering to a single set of regulations, the stage was set for a merger of the firms, which was triggered by an unforeseen economic perturbation.

The charter of 1846 was sealed just as the Parisian economy was shaken by the most serious crisis of the century followed by the uncertainties of political revolution. Gas consumption fell (according to one source by as much as 25 percent), and owners felt the heavy burdens of amortizing the capital for so short a concession. In February 1850 they petitioned the prefect to revise the gas charter on the basis of unification and a longer concession.

A new agreement was hammered out and approved by the administration with what appeared in retrospect to be record speed. The city and the companies were ready to accept in 1852 another eighteen-year concession, with the cost of gas being reduced in stages to thirty-five centimes per cubic meter. The "revolution of 1852," with the simultaneous recovery of economic confidence and the imposition of the steady, guiding hand of a Bonaparte, undoubtedly quickened the negotiations. It brought the producers to settle for a shorter concession than they might have wished in the hope of benefiting from the sudden commercial upturn. The unusual concord between the industrialists and the municipal authorities proved futile, however, for the Council of State rejected the agreement on the grounds that it could be made more favorable to private consumers. This action opened a final round of negotiations, which centered on the price of gas, a matter that would continue to trouble the Parisian gas industry throughout the rest of the century.[14]

A great deal of ink flowed from the companies, outside experts, and public officials about manufacturing costs. Estimates were generally in the range of twenty to twenty-five centimes per cubic meter, but one went as low as three centimes.[15] The industrialists offered, and the city accepted, a rate of thirty-three centimes for private consumers; but once again the Imperial administration upset the accord. Louis-Napoleon had appointed a commission to examine the matter, and its finding was that prices could be lower Showing foresight for which he never received credit, the emperor insisted on the consumer's interests, and negotiations were on the

[14] Ibid., chaps. 2-3; Journal de l'éclairage au gaz (1854-1855).

[15] Compagnies de l'éclairage par le gaz de la ville de Paris, Rapports et délibérations de la commission municipale : Mémoires et documents divers , 3 vols. (Paris, 1855-1856); A. Chevalier, Observations sur le projet de traité pour l'éclairage au gaz de la ville de Paris (Paris, 1854); Mary et Combes, Rapport sur le prix de revient du mètre cube du gaz de l'éclairage tel qu'il résulte des livres de commerce des compagnies anglaises, françaises, et parisiennes (Paris, 1854); Pelouze, Rapport de la sous-commission du gaz : 19 août et 2 septembre 1853 (Paris, n.d.).

verge of collapse. It was at this crucial moment that the Pereire brothers entered the picture and "created" the PGC.

The Pereires did not contribute bold entrepreneurship but simply facilitated concessions from all sides. Some thirty-seven years after the fact, a municipal councilman depicted their role as a matter of bribing the proper authorities. His claim was corroborated by one of the firm's stockholders, who revealed in a private letter that the Pereires dispensed three million francs to get the project off the ground.[16] There is of course no means to probe the allegations. One way or another the Pereires managed to include themselves in what would prove to be an excellent investment. Under their guidance the emperor, the companies, and the city agreed to a fifty-year concession, the longest ever considered, with gas for thirty centimes for private consumers. The Pereires joined the pioneer industrialists of the coal gas industry as founders of the PGC and provided fifteen million of the fifty-five million francs of capital. That was an investment the financiers would never have to regret.

The provisions of the contract, which took effect on January 1, 1856, provided the framework in which the PGC operated until its demise at the end of the concession.[17] In addition to fixing the cost of gas once and for all at thirty centimes for private consumers, it gave the city a price of fifteen centimes for public lighting. The new company was obligated to lay gas mains under a street when a minimal level of demand existed. There were provisions specifying the quality of gas that had to be maintained and the supply of coal the company had to keep in stock to ensure against shortages. The city also negotiated certain financial benefits for itself. The PGC was obligated to pay a two-centime duty on every cubic meter sold. At the end of the concession the city was entitled to the distribution system below the thoroughfares without owing any compensation. Most important, Paris gained the right to half the profits of the PGC after 1872, calculated after a deduction of 8.4 million francs for reserves and debt service. That stipulation made the city a partner in a profitable private enterprise.

The charter of 1855 eventually proved to be a source of political embarrassment for the Imperial government. Critics, especially republican ones, characterized it as a sellout to the interests of "financial feudalism," as an

[16] Conseil municipal de Paris, Rapports et documents: 1892, no. 14, "Rapport . . . par E Sauton," pp. 30-31; AP, V 8 O , no. 616, Graverand to director, April 12, 1880; Maurice Charany, "Le Gaz à Paris," La Revue socialiste 36 (1902): 425.

[17] For published copies of the charters, see Prefecture de la Seine, Service public et particulier de l'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz dans la ville de Paris (Paris, 1883). Besnard, Gaz à Paris , chap. 3, covers the details of the charter of 1855.

alienation of the public interest to selfish monopolists. Under the Third Republic municipal councilmen endlessly discussed the failings of the charter. However, a more balanced assessment is in order. The essential objection made against the gas agreement—that the contract allowed the PGC to charge far too much for gas and thereby reap fabulous, unearned profits—needs qualification. First, the agreement did result in a substantial and immediate reduction in gas rates. If there had been no new charter, consumers would have paid forty centimes or more for another seven years. Aldermen had been under pressure from consumer groups to effect this reduction, and many gas users were probably more interested in immediate costs than the long-term consequences of the concession.[18] Moreover, fixing the rate at thirty centimes happened before the PGC had substantially reduced the cost of production—as it would do in the decade after the charter was signed. Thirty centimes might have seemed indefensibly high in 1865, but not in 1855. Finally, municipal councilmen chose to pursue the interest of the city over that of individual consumers in this agreement. Had they not procured so many financial advantages for Paris, they might have lowered the gas rate for customers. In effect, the public officials decided to impose a hidden tax of sorts on gas users. Given the social profile of consumers—a matter I shall soon explore—this was one of the more progressive taxes levied by the city. Where the Imperial authorities were at fault was in neglecting to create the means to reduce prices in anticipation of falling production costs. They might have been more mindful of the fact that gas companies of London produced handsome returns while selling gas for 15.5 centimes. Yet the agreement did not merit all the opprobrium it received for the rest of the century.[19]

In fact, the revision of the charter worked out in 1861 deserves far more censure, for the opportunity to rectify problems was utterly wasted. The context for the renegotiations was the annexation of the Parisian suburbs. It was already evident that production costs were falling dramatically and that a reduction of the gas rates was in order. Moreover, the city had the leverage to force the PGC into concessions. The company wanted the right to supply gas to the new districts of the enlarged capital, destined for spectacular development. The city might have threatened to award the lucrative gas contract to a new firm. Yet the authorities did not strike a worthy

[18] Journal de l'éclairage au gaz , 1854, no. 7 (October 20): 98-99.

[19] Placing the agreement in a larger context, one could argue that the state proved no more capable of extracting concessions from the new railroad companies. See Kimon Doukas, The French Railroad and the State (New York, 1945), pp. 34-43; Jeanne Gaillard, "Notes sur l'opposition au monopole des compagnies de chemin de fer entre 1850 et 1860," Révolution de 1848 44 (December 1950).

bargain. Indeed, they not only left the defective provisions of the 1855 charter intact, but they also allowed gas executives to impose expensive burdens on the city. The municipal government wound up subsidizing the PGC's lucrative expansion into the annexed areas by guaranteeing a 10 percent return on capital expenditures, paying seventeen francs for each meter of gas main laid there and contributing 0.14 centimes for each cubic meter of gas sold. The ostensible reason for the generosity to the rich gas company was to compensate for the putative risks of the venture. Reasonable observers might have concluded that the negotiators greatly exaggerated those risks. Furthermore, the revision of 1861 finalized another expensive mistake, the city's sharing the firm's amortization costs. Parisian negotiators should have insisted, as several councilmen had since 1855, that the company alone bear that expense. The city's capitulation brought it a concession not worth having, the right to half of the corporate assets when the charter ended in 1906. This was not a wise arrangement for the city because the PGC now had an incentive to allow its plant and equipment to deteriorate as the charter neared its end.[20] In fact, when a new firm took over gas production in 1907, the management decided that several of the PGC's factories were essentially worthless. The successor company had to undertake more than a hundred million francs of immediate capital improvements.[21] Not only did Paris receive little for supporting amortization costs; it paid the cost twice—once when the PGC charged the expenditure to the operating budget and again when the company deducted 8.4 million francs before sharing profits. The courts eventually put a stop to the double payment, but not until Paris had sacrificed millions of francs.[22] Perhaps the authorities who accepted the revised charter were only taking their cue from the state, which had agreed to an excessively generous settlement with the railroad companies a year earlier to encourage development at any price.[23] Nonetheless, the charter of 1861 was indefensible. It represented, at best, a dereliction of duty on the part of Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann and his staff or, at worst, an instance of corruption. Compared with prior bargaining, this charter signaled an

[20] Rapport pr é senté par le Conseil d'administration de la Compagnie parisienne du gaz à I'Assemblée générale (henceforth cited as Rapport ), September 14, 1860, pp. 3-13; Besnard, Gaz à Paris, chap. 3.

[21] AP, V 8 O , no. 1643, "Société du gaz de Paris," deliberations of June 7, 1910.

[22] Rapport, March 28, 1899, p. 41.

[23] Doukas, French Railroad and the State , pp. 34-35. The railroad agreement of 1859 had many of the same features as the PGC's new charter, including public aid for new construction and sharing in the profits after 1872. See also M. Blanchard, "The Railroad Policy of the Second Empire," in Essays in European Economic History, 1789-1914, ed. Francois Crouzet et al. (New York, 1969), pp. 98-111.

alarming decline in the ability of the Imperial administration to defend the public interest.

One more opportunity to modify the gas contract arose in 1870; but at that point the city had little to offer the PGC in exchange for renouncing its most lucrative privileges. As a result of the newest round of bargaining, Paris advanced the onset of profit sharing by two years. In return, the PGC raised the amount of profits exempted from sharing by four million francs. The 1870 charter also put an end to public subsidies for operations in the annexed zone, but not before the PGC had rushed to lay gas lines ahead of need so that the municipality would share the cost.[24] Though this contract marked a return to a higher level of public responsibility than in 1861, Paris still remained unable to wring real benefits from the PGC. The negotiators unwisely treated impending armed conflict with Otto yon Bismarck as a remote possibility. The Franco-Prussian War, ruining gas sales, deprived the treasury of the early shared profits it had paid dearly to receive.

Once the 1870 charter was signed, relations between the city and the company were finalized—much to the regret of aldermen in subsequent decades. Despite a excess of venom on the part of consumers and efforts at negotiations from both sides, no successful new agreement emerged. The provisions laid down in 1855 allowed the PGC to become a very large and rich enterprise even as it presented the firm with serious public-relations problems.

The Sociology of Gas Consumption

The changes in lighting technology during the nineteenth century, from candle to electricity, easily lent themselves to a discourse of progress. Observers found it congenial to tout the triumph of civilization over darkness, using light as a metaphor for material advancement. Behind the hackneyed pronouncements of optimism was one of the many revolutions of everyday life that was so much a part of the nineteenth century. Parisians of varied social categories gradually discovered, each at their own pace, that more and better illumination was a pleasing luxury and, eventually, a necessity. Even before access to that luxury had descended down the social hierarchy gas production had become big business. What happened to gas consumption was paradigmatic for the evolution of a consumer society in nineteenth-century France.

The growth of a consumer economy in France was a particularly com-

[24] Rapport , March 29, 1867, p. 16; September 23, 1869, pp. 1-20.

plex and even paradoxical affair. On the one hand, French enterpreneurs were leaders in developing modern commercial institutions, like department stores. Michael Miller is surely correct to observe that the flourishing of mass retail outlets presupposed a bourgeoisie that was open to consumer innovations and willing to define social status in terms of purchasable commodities.[25] On the other hand, it is a commonplace of French economic history that manufacturers failed to find a mass market for products and instead pursued a strategy of high quality and low volume. Not only were the urban and rural masses excluded from the consumer economy until the twentieth century by the lack of disposable income; those who had comfortable livelihoods seemed to resist the "civilization of gadgets." Many visitors from Victorian Britain expressed surprise at the lack of home comforts among prosperous Parisians.[26] An analysis of gas use does nothing to dispel the incomplete and selective features of nineteenth-century French consumerism. But such an analysis may reveal some of the mechanisms that guided the uneven expansion of the consumer market.

Contemporary perceptions of gas use were so misleading as to undermine confidence in the value of qualitative evidence. The Paris Chamber of Commerce announced that gas lighting was "general" already in 1848. Two engineers writing a few years later argued that gas could "now be considered among the necessities of social life" and would soon become so even for the working classes. Their observation echoed the assurances the PGC's management passed along to stockholders, that the use of gas had "become like air and water."[27] These appreciations lend credence to one historian's claim—quite erroneous, as it turns out—that one in five Parisians lit their homes with gas by the end of the Second Empire.[28] These commentators were not mistaken to find an exceptional acceleration in the demand for better lighting, but they exaggerated the extent to which gas served the newly manifested need.

There can be no question that Parisians easily accommodated them-

[25] Michael Miller, The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store , 1896-1920 (Princeton, 1981), pp. 237-240.

[26] Donald J. Oisen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna (New Haven, 1986), pp. 37, 119, 122; Zeldin, France, 2:612-627.

[27] Chambre de commerce de Paris, Statistique de l'industrie à Paris pour les années 1847-1848 (Paris, 1851), p. 125; Exposition universelle internationale de 1878, Rapports du jury international. Groupe III. Les Procédés et les appareils de chauffage et d'éclairage par M. Barlet (Paris, 1881), p. 46; J. Gatliff and P. Pers, De l'éclairage au gaz dans les maisons particulières (Paris, 1855), p. 2.

[28] Louis Girard, La Deuxième République et le Second Empire, 1848-1870 (Paris, 1981), p. 199.

selves to higher standards of illumination and embraced innovations that provided more lighting. Progressive administrators who sought to improve public lighting in the face of an initially indifferent population eventually found Parisians pressuring them for still better lighting. A technical improvement in the burners of street lamps nearly tripled the amount of light they produced and won the applause of the public in the 1860s. The appearance of electrical lamps reproduced the cycle of skepticism followed by acceptance. The early experiments provoked derision from the press, and some editors wondered if the intense illumination would not blind people. It was not long, however, before local politicians had to include among their campaign promises the provision of electrical lights in the neighborhoods they represented. The organizers of the Universal Exposition of 1900 recognized that standards of lighting had become categorically higher than they had been just a decade earlier and took pains to endow their project properly. The Champ de Mars during the 1900 celebration had nearly five times the lighting power as in 1889. Of course, improvements had a self-defeating quality for success in meeting current expectations produced still higher ones.[29]

The growing sensitivity to illumination on the streets found a counterpart inside the home. The first mark of rising standards was the widening use of oil lamps in the late eighteenth century. They moved beyond workshops and the homes of the rich into modest households when the Swiss inventor Aimd Argand dramatically improved their effectiveness by increasing the draw of air reaching the flame in 1786. Numerous innovations, simplifications, and price reductions followed. The "art of lighting," to use the term of one of the earliest engineers working in the field, was now a matter of evolving technolog. Architects welcomed the cheapening of plate-glass production and incorporated larger and more numerous windows into their plans. The Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, the first library in France to remain open at night, was built in 1843 and pointed in the direction that household amenities could take.[30] The demand for illumination accelerated vastly in the second half of the century along with

[29] Le Gaz, no. 9 (June 15, 1861): 104; AE V 8 O , no. 270, director to prefect, June 4, 1857; Gatliff and Pets, De l'éclairage, p. 8; Eugène Defrance, Histoire de l'éclairage des rues de Paris (Paris, 1904), pp. 107-121; J. Laverchère, "Eclairage intensif par le gaz des parcs et des jardins du Champ-de-Mars et du Trocaddro," Le Génie civil 37 (1900): 27. For campaign posters promising electrical lighting, see Archives de la Prdfecture de police (henceforth cited as Préfecture), B/a 695.

[30] E. Paul Bdrard, L'Economie domestique de l'éclairage (Paris, 1867), pp. 6-28; E. Pdclet, Traité de l'éclairage (Paris, 1827). On the Biblioth èque Sainte-Genevieve, see David Pinkney, Decisive Years in France, 1840-1847 (Princeton, 1986), pp. 105-109.

the means to satisfy it. The engineer Philippe Delahaye measured the per capita consumption of lighting in Paris from the three principle sources, gas, kerosene, and electricity; he found a forty-five-fold increase between 1855 and 1889.[31] Clearly the PGC came into existence just as daily life in France was entering into a dependence on combustible energy sources.[32]

The public's receptivity to improved means of illumination (and of heating as well) provided a most favorable business climate for the PGC. The firm grew vigorously. The first thirty years saw total gas consumption in Paris and its suburbs rise sevenfold, from 40 million to 286 million cubic meters (see appendix, fig. A1). Gas use doubled during the decade of the 1860s and again during the 1870s. The PGC began its concession with a mere thirty-five thousand customers inherited from the former firms. Initially the clientele was necessarily limited because gas lines reached only the first floors of buildings. A potential user on an upper floor would have had to pay for long and expensive connector pipes from the gas main in the street to the dwelling, and few wanted to bear the expense. The PGC resolved this limitation by installing mounted gas mains (conduites mon-tantes ) in the stairwells of buildings. With this innovation customers had only to rent or buy connecting pipes (branchements ) from the hallway to their lodgings. The company began installing such mounted mains in March 1860, and a vast potential market opened. Another restraint on private consumption disappeared soon after the PGC began operating. Its predecessors had offered gas only during the night, the hours that street lamps were lit. This restriction meant that industrial use of gas or heating with gas in the home was not possible. The PGC began day service on September 1, 1856; within three years it had as day customers 163 restaurants, 233 bakeries, 63 hotels, and more than a thousand cafés.[33] Partly as a result of these measures, the PGC was able to expand far beyond the clientele it had inherited to 190,000 customers in 1885 (see appendix, fig. A2).

Rising standards of lighting and more useful arrangements for residents did not necessarily produce a mass market for the PGC, however.

[31] L'Abaissement du prix du gaz à Paris (Paris, 1890), p. 21.

[32] David Landes notes a sixfold increase in world consumption of commercial energy sources between 1860 and 1900. See his Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present (Cambridge, 1969), p. 98. See also Fred Cottrell, Energy and Society: The Relation between Energy, Social Change, and Economic Development (New York, 1955), for the concepts of low-energy and high-energy societies. Nineteenth-century Europe was clearly in transition from one to the other.

[33] AP, V 8 O no. 724, deliberations of March 22, 1860; no. 765, "Répartition des abonnés faisant usage du gaz pendant le jour (février 1860)."

The clientele of the original gas firms had consisted primarily of commercial establishments on the first floors of buildings; even in the 1880s as the era of electricity was dawning, the PGC still relied heavily on those users. The president of the company affirmed in 1880 that a majority of subscribers (74,400 out of 135,500) were industrial or commercial enterprises.[34] Of course, each of the business customers was likely to use far more gas than an average residential user. Between 1855 and 1885, supplying gas to residents was an appendage to the main business of lighting commercial and industrial establishments.

The PGC could not have been founded at a better moment to grow and prosper by bringing gas to Parisian businesses. The capital was about to undergo two decades of dramatic changes that would enlarge and enrich this clientele. Since gas was the energy source of choice in terms of efficiency, convenience, and novelty, commercial firms adopted it as a matter of course. In the modern Paris that emerged under Baron Haussmann, urban renovations accompanied and accentuated the commercial transformation of the capital. Luxurious apartment buildings appeared along Haussmann's attractive boulevards, especially in the western quarters, and central Paris lost residents but was filled during the day by salespeople, clerks, business agents, and wholesalers. A new shopping district arose to the north and west of the grands boulevards to supplement the older one around the Palais Royal and along the rue de Richelieu (second arrondissement). It was no wonder that the portion of the capital's working population earning a living from commerce rose from 12 to 30 percent during the golden age of the PGC.[35]

The commercial vocation of Paris was favored by two great transformations, the booming world economy of the 1850s and the railroad revolution. Paris became the center of a vast export trade as the well-off in Britain, the Americas, and elsewhere purchased its handicrafts. French exports rose fivefold between 1846 and 1875, and a quarter of the manufactured goods sent abroad was made in Paris.[36] The railroads centralized

[34] Frédéric Margueritte, Observations present,es à Monsieur le Prefer de la Seine sur une pétition tendant à obtenir la réduction du prix de vente du gaz d'éclairage (Paris, 1880), p. 20. His figures are not perfectly consistent with those in other sources, but they at least have an illustrative value.

[35] David Pinkney, Napoleon III and the Rebuilding of Paris (Princeton, 1958); Francois Loyer, Paris au XIX siècle: L'Immeuble et l'espace urbaine, 3 vols. (Paris, n.d.); Philip Nord, Paris Shopkeepers and the Politics of Resentment (Princeton, 1986), chap. 3.

[36] Maurice Lévy-Leboyer and Francois Bourguignon, L'Economie française au XIX siécle: Analyse macro-économique (Paris, 1985), pp. 43, 49; Roger Price, An Economic History of Modern France , 1730-1914 (London, 1975), pp. 158-159.

commercial activities in the capital. They made tourism, retailing, and all other sorts of exchange of information and personnel increasingly feasible. Haussmannization concentrated these changes by giving the growing bourgeois population new neighborhoods, a new housing stock, and new patterns of urban life. Philip Nord has argued that department stores were products of the spatial reorganization of the city depending as they did on massive concentrations of consumers on the boulevards. These emporiums became among the best customers of the PGC, but they provide only one example of the ways commercial expansion gave a boost to gas consumption.[37]

The British writer Philip Gilbert Hamerton claimed that his countrymen had invented the home but the French, especially the Parisians, "invented the street." His remark underscores the transformation of Paris from a city that contained pleasures to a showcase of monumentality, public pleasures, and commercialized leisure during the Second Empire.[38] Gas lighting was an essential accompaniment to the metamorphosis. The streets with the largest gas consumption in 1868 traced the core of commercial Paris—the grands boulevards (132,000 cubic meters), the rue de Rivoli (90,500), the rue Saint-Honoré (82,000), and the boulevard Sébas-topoi (77,500). The use of gas was closely associated with public display. Parisians had probably received their first indoor experience of gas lighting in cafés. Indeed, one of the earliest pubs to be served by gas took the name Café du gaz.[39] The predecessor of the department store during the first years of the nineteenth century, the commercial arcade, put the new energy source to good effect. One observer of 1817 described the passage des Panoramas in the second arrondissement as "a fairy country . . . brilliantly illuminated . . . by [gas]light reflected endlessly off windowpanes and mirrors."[40] Theaters became showcases for gas lighting, not only with their grand chandeliers, but also because stage technicians learned how to use gas for enhancing sets. The Théâtre Gymnase spent thirteen

[37] Nord, Shopkeepers , pp. 132-137. On the use of gas by department stores in the 1860s, see AP, V 8 O , no. 751, "Etat comparatif des consommations du gaz de divers établissements particuliers (1864-1866)."

[38] Olsen, City as a Work of Art , pp. 219-224, 231. An important study of Parisian leisure and entertainment in this period is Robert Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (New Haven, 1988).

[39] AP, V 8 O , no. 753, "Comptabilité des abonnés"; Defrance, Eclairage des rues , p. 99.

[40] Cited in Nord, Shopkeepers , p. 90. By no means was the gas lighting in arcades always so brilliant. Emile Zola described the Passage du Pont Neuf, lit by three gas jets, as dingy and sinister-looking. See his Thérèse Raquin, trans. L. W. Tancock (Baltimore, 1962), p. 1.

thousand francs on gas fixtures in 1867. The press marveled at the fact that the Grand Hôtel alone used more gas than the entire city of Or-1éans.[41]

The great establishments of Haussmann's boulevards were the PGC's most important customers. In 1886, just as electricity was about to coopt some of this business, the Bon Marché department store and the Grands Magasins du Louvre topped the list with more than five hundred thousand cubic meters each (table 2). Some of the celebrated cafés and famous dance halls of the city used more than a hundred thousand cubic meters. The Tivoli-Vaux-Hall paid annual bills of nearly forty thousand francs. The 128 customers consuming more than forty thousand cubic meters annually (0.07 percent of all customers) used 5 percent of all gas consumed in Paris. This clientele had enormous influence as well. Their glamour, prestige, and visibility ensured that when people thought of the City of Lights, they had gas lighting in mind. Such large customers made gas seem not only efficient but also progressive. They set the style for a myriad of smaller stores, offices, and pubs.

The lighting needs of commercial Paris easily surpassed the industrial uses of gas, though there were important exceptions. Among the PGC's largest customers were the Sommier and Lebaudy sugar refineries. Brewers and liquor distillers also took advantage of gas as an easily regulated source of heat. Some of the largest printers used gas motors to drive their presses and ranked with department stores as customers. On the whole, however, gas had not entered directly into production processes, and manufacturers used it mainly for lighting.[42] Gas engineers had hoped to sell their product to foundries, but the Société industrielle des métaux of Saint-Denis was the only large one to use it. The largest jewelry manufacturer in Paris, Savard, was only a modest consumer; its craftsmen did not use coal gas to fuel their burners. The imposing Cail machine company, which employed more than two thousand workers, used much less gas than the Café américain on the boulevard des Capucines. During the

[41] La Presse , August 26, 1863, p. 3; AP, V 8 O , no. 672, deliberations of October 16, 1867. On the uses of gas in nineteenth-century theaters, see Terence Rees, Theatre Lighting in the Age of Gas (London, 1978).

[42] Gas did have an impact on daily work patterns, and the introduction of gas lighting raised labor protests here and there. I have not found examples of protest in Paris, but see Pierre Cayez, Métiers jacquards et hauts fourneaux: Aux origines de l'industrie lyonnaise (Lyon, 1978), p. 295; Elinor Accampo, Industrialization, Family Life, and Class Relations: Saint Chamond , 1815-1914 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989), p. 82; and Harvey, Urban Experience , p. 7, citing the remarks of Friedrich Engels on Manchester.

Table 2. The Twenty Largest Gas Customers in 1886 | |

Firm | Annual consumption (cubic meters) |

1. Grands Magasins du Louvre | 533,457 |

2. Bon Marché (department store) | 505,624 |

3. Hôtel Continental | 351,149 |

4. Grand Hotel | 324,702 |

5. Théâtre Eden | 303,128 |

6. Raffinerie Lebaudy (sugar) | 283,857 |

7. Bazar de I'Hôtel de Ville | 268,768 |

8. Belle Jardiniere (department store) | 255,431 |

9. Raffinerie Sommier (sugar) | 252,044 |

10. Christofle (silversmiths) | 199,043 |

11. Grande Imprimerie Nouvelle | 187,537 |

12. Imprimerie Dupont | 182,894 |

13. Folies Bergères | 161,627 |

14. Société industrielle des métaux | 159,021 |

15. Café Américain | 135,502 |

16. Grand Café | 109,828 |

17. Théâtre Odéon | 107,280 |

18. Théâtre Gymnase | 106,033 |

19. Tivoli-Vaux-Hall (ballroom) | 95,030 |

20. Cail (machinery) | 81,073 |

Source: AP, V 8 O1 , no. 707, "Consommation de divers établissements." | |

golden era of gas, display, spectacle, and simple illumination were its principal applications.

Gas use was nearly universal among commercial and industrial firms. Approximately four-fifths of the ninety-three thousand workshops and stores in Paris of 1880 used gas.[43] In view of this massive success and of the familiar terms on which Parisians lived with gas outside their homes, it is surprising how rarely they used gas inside their residences. Reliance on less efficient and less elaborate forms of energy was not a simple matter of affordability. The Parisian bourgeoisie was almost as hesitant as the common people about putting gas fixtures into its homes. The use of gas thus raises interesting questions about preferences, habits, and innovations among French consumers.

The statistics on domestic consumption at the beginning of the electri-

[43] Margueritte, Observations , p. 20.

Claude Monet's painting of a Parisian apartment—luxurious but lacking

gaslights. Un coin d'appartement, 1875; courtesy Musée d'Orsay.

cal era, in 1889, comment ironically on the PGC's frequent assurances that gas had become a necessity of life. Only 15 percent of all residences were adjacent to mounted mains and therefore were potential gas users. The policies of the PGC presented one reason for the limited availability of gas, but a discussion of marketing practices can and should be postponed until

Table 3. Residential Gas Use in Paris, 1888 | |||||

Arrondissement | No. Residences | No. Adjacent to Mounted Main | No. Using Gas | % Using Gas | |

First | 23,012 | 6,616 | 2,243 | 9.8 | |

Second | 24,927 | 8,304 | 3,083 | 12.4 | |

Third | 31,809 | 9,240 | 3,053 | 9.6 | |

Fourth | 32,098 | 4,168 | 1,239 | 3.9 | |

Fifth | 24,910 | 3,904 | 1,095 | 3.1 | |

Sixth | 31,139 | 4,776 | 1,374 | 4.4 | |

Seventh | 26,100 | 3,880 | 1,051 | 4.0 | |

Eighth | 23,279 | 9,558 | 5,525 | 23.7 | |

Ninth | 41,525 | 15,688 | 6,241 | 15.0 | |

Tenth | 53,152 | 12,798 | 3,955 | 7.4 | |

Eleventh | 67,599 | 9,204 | 1,945 | 2.9 | |

Twelfth | 31,177 | 1,504 | 301 | 1.0 | |

Thirteenth | 26,291 | 355 | 70 | 0.3 | |

Fourteenth | 27,082 | 580 | 140 | 0.6 | |

Fifteenth | 28,472 | 389 | 75 | 0.3 | |

Sixteenth | 16,012 | 2,640 | 919 | 5.7 | |

Seventeenth | 41,499 | 5,160 | 1,374 | 3.3 | |

Eighteenth | 53,931 | 1,863 | 350 | 0.7 | |

Nineteenth | 34,439 | 651 | 153 | 0.4 | |

Twentieth | 36,499 | 432 | 47 | 0.1 | |

Total | 684,952 | 101,710 | 34,235 | 5.0 | |

Source: AP, V 8 O1 , no. 30, "Statistique des maisons de Paris au point de vue de la consommation du gaz." | |||||

a later point. The matter that concerns us at present is that most households that had the option of lighting with gas did not do so. In the city as a whole, only a third of the apartments near mounted mains used gas. The range was from 58 percent in the wealthy eighth arrondissement to 8 percent in the poor twentieth. No more than 5 percent of all Parisian residences were customers of the PGC. Far from being a necessity of life, domestic gas was a curiosity (see table 3).

Evidently the use of gas had not become a class phenomenon, dividing the bourgeoisie from the urban masses. To be sure, there were wealthy people who could not have done without gas. The elegant town house of the duc de Montesquieu on the quai d'Orsay had fifty gas jets (becs de gaz ) in 1860. The largest domestic consumer, as might be expected, was Baron James de Rothschild, whose palace on the rue Saint-Florentin used forty-six thousand cubic meters a year, almost as much as the Elysée-

Montmartre Theater. At the other extreme, Parisians of modest means hardly ever lit with gas. Less than 1 percent of the households paying less than five hundred francs in annual rent—below the threshold of bourgeois residences—were customers of the PGC.[44] In their pattern of gas use Parisians between these two extremes more often resembled the poor than they did the Rothschilds. Most of the apartments with access to mounted mains rented for at least eight hundred francs a year and as such were among the costliest 10 percent of Parisian residences.[45] Yet only one in three affluent renters used gas. Fewer than a thousand apartments out of sixteen thousand in the sixteenth arrondissement lit with gas. Clearly, gas at the end of its golden age had not even become a daily luxury in which the well-off indulged.

It is a commonplace that French consumers, like businessmen, were slow to accept changes. Scholars have often stressed deeply rooted cultural values and distinctive collective attitudes in accounting for their preferences. Alain Corbin, for example, explains the backwardness of French hygienic practices relative to the British in terms of unconscious predispositions regarding the body. He concludes that income and degree of urbanization were less decisive factors.[46] It is tempting to apply his approach to gas use, especially given the stereotype about French consumers being indifferent to and undemanding about domestic amenities. The French bourgeoisie supposedly spent money on food, clothes, and leisure but not on making the home comfortable.[47] Before adopting this explanation for gas consumption, it would be well to take a broader view. A full consideration of the material conditions attending gas use reduces, if not eliminates, the autonomous role of cultural values in shaping consumer behavior.

The high rates for gas in Paris played a role in limiting its use. The press screamed about this subject at times, and any Parisian who read a newspaper regularly could learn that residents of Berlin, Brussels, and

[44] AP, V 8 O , no. 707, "Consommation de divers éablissements"; no. 24, "Transformation de l'éclairage dans Paris (14 novembre 1892)"; no. 724, deliberations of April 12, 1860.

[45] P. Simon, Statistique de l'habitation à Paris (Paris, 1891), p. 14, for data on the distribution of rent levels in 1890.

[46] Alain Corbin, Le Miasme et la jonquille: L'Odorat et l'imaginaire social (Paris, 1982), p. 202.

[47] The basic statement on the problematical nature of French consumerism is to be found in Maurice Halbwachs, La Classe ouvrière et les niveaux de vie (Paris, 1912). See also Rosalind H. Williams, Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1982); Zeldin, France, 2:612-627; Olsen, City as a Work of Art, pp. 119-122.

Amsterdam paid only twenty centimes. Londoners paid half the rate of Paris; per capita consumption in London was about twice as high.[48] Noteworthy as the high cost of gas in Paris was, however, the rate alone was not the determining factor. Engineers had no trouble demonstrating quantitatively that even at thirty centimes gas provided more efficient lighting than kerosene, candles, or its other immediate competitors. It would not have been a great burden on bourgeois residents to light with gas as long as they used it prudently. A hundred hours of gas lighting would have cost them only three francs for the fuel.[49] In fact, the PGC was able to expand the domestic use of gas dramatically in the last decade of the nineteenth century even when the price remained at thirty centimes, so

Many Parisians refrained from using gas at home because it had certain disadvantages. Corbin has demonstrated an escalating sensitivity among French people of the nineteenth century to foul odors and an ever-stronger desire for fresh, circulating air.[51] Such sensibilities discouraged gas use. The public was well aware that gas lighting made rooms stuffy and emitted more heat than competing sources of lighting. One engineer established that gas produced almost twice the carbon dioxide that kerosene did and warned of headaches, nausea, and even slow intoxication. The residues of gas combustion faded fabrics, discolored ceilings, and marked walls.[52] Even the employees who worked in the PGC's headquarters complained about stuffy offices and irregular light.[53] Gas also produced a sulfurous odor that annoyed sensitive souls like Hippolyte Taine

[48] For gas rates in various French and European cities see Rapport, March 29, 1881, p. 92; Margueritte, Observations, p. 30; A. Guéguen, Etude comparative des méthodes d'exploitation des services de gaz (Paris, 1902). For data on per capita consumption in various cities, see Compte rendu des travaux de la commission nommée le 4 février 1885 en execution de l'article 48 du traité. . . entre la ville de Paris et la Compagnie parisienne de l'éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz. Procès-verbaux (Paris, 1886), p. 91; AP, V 8 O , no. 1677, "Etudes générales de l'élairage étranger, 1898-1901"; no. 1070, "Notes pour servir à l'établissement des budgets."

[49] Bérard, Economie domestique , p. 45. On the relative efficiency of gas lighting, see E. Jourdan, Renseignements pratiques à l'usage des consommateurs de gaz (Le Mans, 1868), pp. 10-14, and Philippe Delahaye, L'Eclairage dans la ville et dans la maison (Paris, n.d.), pp. 147-159, 268.

[50] See chapter 2.

[51] Corbin, Miasme et la jonquille , chap. 5.

[52] Jean Escard, Le Problème de l'éclairage à l'usine et à I'atelier (Paris, 1910), pp. 38-40; Michel Chevalier, Observations sur les mines de Mons et sur les autres mines de charbon qui approvisionnent Paris (Paris, n.d.), p. 88; William Suggs, The Domestic Uses of Coal Gas, as Applied to Lighting, Cooking, and Heating (London, 1884), pp. 8-18, 157.

[53] Le Journal du gaz. Organe officiel de la chambre syndicale des travailleurs du gaz , no. 76 (February 5, 1896), p. 3.

even in the street. That odor in fact was the source of a popular medical myth that identified gas plants as a refuge from cholera epidemics. One editor caricatured the PGC as a sinister figure surrounded by clouds of soot, sulfuric acid, and carbonic acid.[54] These emanations made potential customers hesitate before installing gas in their homes.

The hesitations were all the more serious in that gas was costly and inconvenient to install.[55] Customers had to pay for connector pipes from the main to their apartments, for interior pipes, and for fixtures. They also had to rent (or buy) a meter and certain cutoff nozzles on the mains. These charges amounted to thirty-six francs a year, nearly as much as a modest consumer would spend on the gas itself.[56] There were also fees for preparing the inspection papers and a monthly exaction for upkeep of the gas line. In addition, the PGC required a security deposit, which seemed to annoy potential customers. Even Baron de Rothschild and an English lord asked to be exempted from the requirement. Estimates placed the cost of initiating gas service between sixty and eighty francs.[57]

Making the installation expenses especially burdensome was the tran-siency of Parisian tenants, who might have used gas if they had found it previously installed in their new lodgings. The speculative construction of the Second Empire, which helped to renew the bourgeois housing stock, did give the PGC some support in this area. The Pereires' novel building enterprise, the Société immobilière, put gas fixtures in all its apartments along the new boulevard du Prince-Eugène (now the boulevard Voltaire). The industrialist Cail did the same for the sizable residential complex he developed in the tenth arrondissement. There were even isolated efforts to bring new, gas-lit apartments to the better class of wage earner. Despite these promising initiatives most tenants were unlikely to find gas fixtures ready for them to use as they took up new lodgings. Mounted mains went primarily into new apartment buildings and hardly touched the older stock of housing. Even in most new, luxurious buildings there was gas only in the hallways, not in individual apartments.[58] Landlords lacked

[54] Girard, Deuxième République, p. 328; Le Gaz , no. 3 (April 30, 1866): 101; AP, V 8 O no. 1294, press clippings.

[55] The customer's responsibilities in installing gas are described in Emile Durand, Guide de l'abonné au gaz d'éclairage (Paris, 1858).

[56] AP, V 8 O , no. 615, "Exoneration des frais accessoires."

[57] Ibid., no. 669, deliberations of September 20, 1862; no. 767, report of February 8, 1873; Margueritte, Observations , p. 6; Durand, Guide de l'abonn é, pp. 35-113.

[58] César Daly, L'Architecture privée au XIX siècle. Nouvelles maisons de Paris et des environs, 3 vols. (Paris, 1870), 1:224-225; AP, V 8 O no. 725, deliberations of February 11, 1864; no. 726, deliberations of October 31, 1867; nos. 28-29, "Conduites montantes"; Michel Lescure, Les 5ociétés immobilières en France au XIX siècle (Paris, 1980), p. 45.

pressure to bear the expense of installing gas fixtures. The rental market favored owners until the mid-1880s, and they easily leased unimproved properties.

Even if landlords or tenants decided to pay for the installation, they were likely to find the experience frustrating. The delays and errors arising from renting the meter, obtaining the obligatory certification from the prefecture, and completing the paperwork were so notorious that the Daily Telegraph of London satirized the situation in 1868. The PGC's engineers were certain that the prefect's rigor and slowness in inspecting the work seriously discouraged the operation.[59] Madame Jacquemart, a publican in Belleville, learned the labyrinthine ways of gas regulation in 1869. She had become a customer, installing the proper pipes and renting a meter without realizing that the gas mains on her street did not yet reach her building. The company had been trying to extend the mains, but the prefect had withheld authorization for more than a year. When at last the company was able to do the work and supply Jacquemart's cafe, the payment bureau ordered a cutoff of the service because the owner had not paid rent on her (unused) meter.[60] Not even the Parisian correspondent to the Daily Telegraph had imagined that such complications could arise, but they did.

Residents might have persevered through the difficulties and spent what they had to for installation if indeed gas was as convenient and necessary as its proponents asserted. However, gas did not have many applications and did not always accord with bourgeois life-styles. Lighting was the only use most Parisians envisioned for gas until the last years of the century. The PGC had originally hoped to develop gas heating but abandoned the idea in 1857 for lack of satisfactory stoves. Existing heaters spread disturbing odors and emitted hydrochloric acid. Moreover, gas heating was not economical. The company chose to develop coke, one of its by-products, as a source of heat and did not take gas heating seriously again until the 1890s.[61] The use of gas for cooking also proved to be some-

[59] Le Gaz , no. 5 (June 31, 1868): 70; Exposition universelle de 1878, Rapports , p. 46. British gas experts argued that public inspection improved the quality of work done on French installations. See Suggs, Domestic Uses , p. 49.

[60] AE V 8 O , no. 766, report of Lependry to director, April 18, 1869.

[61] Ibid., no. 752, "Chauffage"; no. 1257, "Chauffage au gaz." When the company installed gas heaters in its appliance showroom, it took care to hide the meter from the public so as to avoid drawing attention to the cost. The PGC itself heated its offices with coke, not gas.

what of a dead end during the PGC's golden era. Gas engineers argued for the economy and convenience of gas cooking, but many customers did not like the taste of meats prepared through gas grilling. Interest in culinary uses of gas was so low that special cookbooks did not appear until the end of the century. Domestic servants slowed the entry of gas into the bourgeois home. Since they spent so much of their time in the kitchen, it is understandable that they would want a stove that heated the room during the winter as well as cooked the meals. One trade journal counseled mistresses to instruct their servants on the rationality and progress embodied in gas cooking, but maids had their own logic.[62]

When the PGC finally began to be concerned about the failure of its product to penetrate the residential market in the late 1880s, management probed the ways gas might serve the bourgeoisie. A consultant drew attention to the large Parisian classe moyenne, those paying five hundred to fifteen hundred francs in rent, who had so far been resistant to gas. The reason, he believed, was that these families spent most of their time in the dining room, which was rarely served by gas fixtures. When landlords had bothered to add gas lighting at all, they almost always put it in one room, the salon. Moreover, gas chandeliers (lustres ) attractive enough for the dining room were uncommon and expensive. The consultant concluded that gas failed to enhance family life for these thousands of residents, so the tenants ignored it.[63]

Faced with all these problems, Parisians had a reasonable alternative to gas. Kerosene lamps arrived in France in the 1860s and immediately hampered the PGC from developing a domestic clientele. Per capita consumption of kerosene increased fivefold in Paris between 1872 and 1889. This source of illumination did not require expensive or cumbersome installation. Cheap and even attractive lamps quickly came to the market. They could be carried from room to room. Taken solely as a source of illumination, gas could not easily compete with kerosene. There is little wonder why the PGC was repeatedly accused of conspiring to keep duties on that fuel very high.[64]

Thus there is no reason to assume that French consumer preferences were guided primarily by an unconscious scorn for the novel or an indif-

[62] Gas was best for quick cooking—omelets, a slice of ham, or an entrecote. Bourgeois cuisine entailed slow cooking over wood fires. See Zeldin, France , 2:750-751; Suggs, Domestic Uses , p. 126.

[63] AP, V 8 O , no. 30, report of August 25, 1894.

[64] Philippe Delahaye, L'Industrie du pétrole à l'Exposition de 1889 (Paris, 1889), pp. 9-70; Conseil municipal, deliberations of November 7, 1892; L'Echo du Gaz. Organe de l'Union syndicale des employes de la Compagnie parisienne du gaz , no. 87 (November 1, 1900): 2.

ference to household conveniences. The Second Empire architect César Daly was justified in contradicting the shibboleth that the Parisian bourgeoisie was hopelessly infected with aristocratic preoccupation for public display. He asserted that domestic design in his day was "more concerned with hygiene and comfort than with ornament" and that rising standards of comfort provided the guiding principle for architects.[65] Well-off Parisians who shunned gas were responding to its concrete problems and limitations. They saw and appreciated gas in their stores, offices, and shops but had no strong urge to countenance the expense and inconvenience of bringing it into their homes. Hence the PGC benefited from rising standards of lighting mainly to the extent that commercial establishments implemented them. Nonetheless, there was a potentially large domestic market for gas since Parisians were open to new amenities that enhanced their lives at a reasonable cost. The PGC would discover and exploit this market when its older clientele seemed about to abandon gas.

The Profits of a Privileged Firm

The bookkeepers of the PGC were probably unconcerned that the source of the copious revenues they recorded was the business firm rather than the residential customer. From the clerks' vantage point their employer was faring remarkably well. The company never had an unprofitable year (see appendix, fig. A3). Indeed, it reached a new plateau of profitability every year except one (1877) between its founding and 1882. Profits rose nearly 175 percent during the 1860s as the company benefited from the annexation of the suburbs and from the commercial development of Paris. Returns rose another 65 percent during the 1870s. Top management spoke occasionally, in hushed tones, about the risks of capital, but supplying gas to the stores and offices of the city was in reality a golden opportunity.

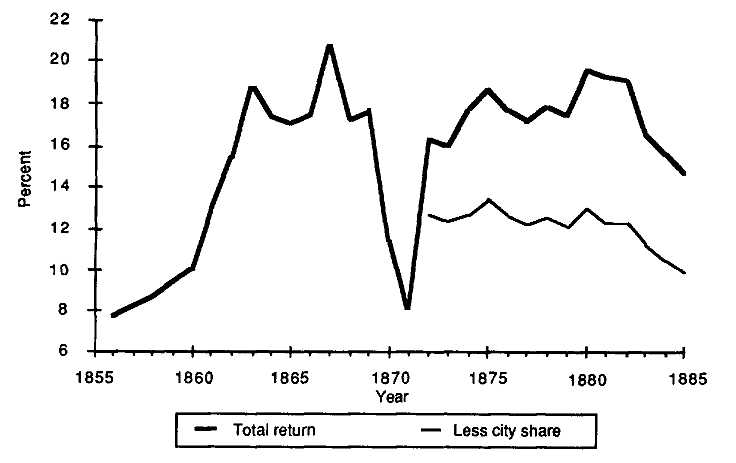

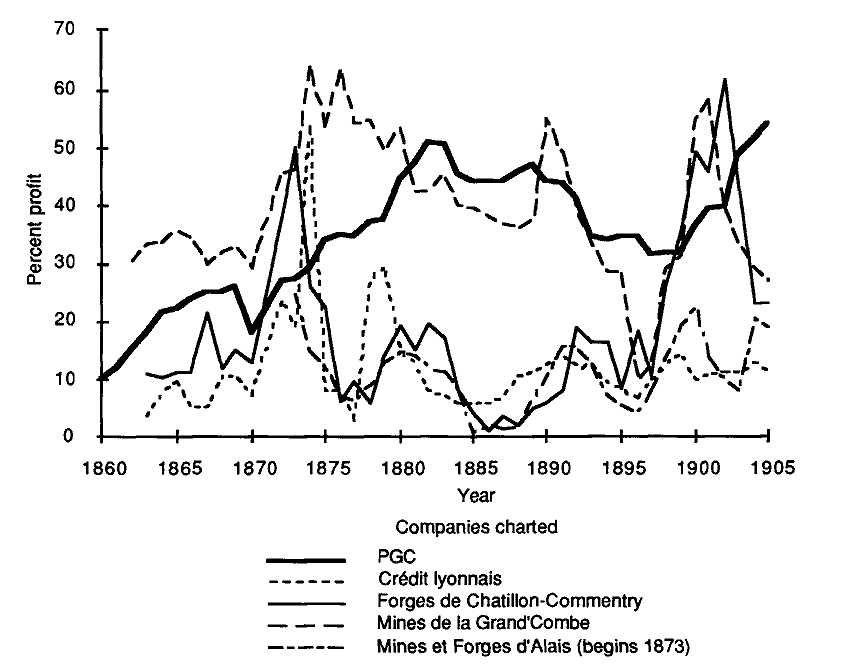

The prosperity of the PGC may be measured in several ways. In terms of the portion of annual receipts, gross profits were enormous; they averaged 42.6 percent during the first thirty years of the firm's existence. Likewise, operating ratios (gross profits as a percentage of expenditures) underscore the success of the enterprise, averaging 72.7 percent (see appendix, fig. A4).[66] Perhaps a more refined measure, taking account of the relative yield of the investment, would be the return on immobilized capital (figure 1). Whereas government bonds yielded 4-5 percent and the

[65] Daly, Architecture privée , 1:14.

[66] Neither of these figures takes account of the revenues shared with the city of Paris after 1872.

Fig. 1. Return on capital, 1855-1885 (in percent). From AP, V 8 O1 no. 907, Rapports

présentés par le Conseil d'administration à l'Assemblée générale, 1856-1905.

average income from a real estate portfolio was 7-8 percent, the PGC returned an average of 17 percent during the 1860s.[67] After 1872, when the company began to share (with large sums set aside for reserves) profits with the city the problem of calculating yields becomes more complicated. Should payments to the city be considered as part of the profits or as an expenditure? Technically of course, the PGC was sharing its profits with Paris. Yet from the stockholder's perspective the payment was a cost of doing business, an expense no less inevitable than money spent on raw materials. Even if the city's share is deducted from gross profits, the PGC's returns on immobilized capital were still quite high, averaging 12.5 percent between 1872 and 1882. One franc of capital produced twelve centimes of profit for the PGC, whereas the Gas Lighting and Coke Company of London derived just eight centimes.[68] Only the most risky real estate venture in Paris could have been so remunerative.

Since the PGC was a limited-liability corporation, one of the handful in France before the liberalizing laws of 1863 and 1867, the stockholders

[67] See Adeline Daumard, Maisons de Paris et propriétaires parisiens au XIX siècle, 1809-1880 (Paris, 1965), p. 228, on profits from real estate investments.

[68] AP, V 8 O , no. 709, report of Audouin to director, March 31, 1882.

were the chief beneficiaries of the business success. The capital of the firm originally consisted of 110,000 shares, each with a nominal value of five hundred francs. In 1860 the company raised another twenty-nine million francs in equity; but the corporate charter placed limits on the number of shares it could issue, so that was the last time ownership was further dispersed. The company subsequently covered its considerable investment needs through the sale of bonds. By 1897 the PGC had 257 million francs of debt. Although reinvestment of profits was the rule among most French firms, the PGC never tapped that source of capital.[69] Indeed, in the early years, when the firm was encumbered with the need to build productive capacity rapidly it secured a short-term loan of four million francs from the Crédit mobilier to pay current dividends. The shareholders expected regular returns and grumbled when investment seemed to cut into their income. 7o

The identity of the PGC shareholders is destined to remain obscure, for the firm's archives do not contain a file on them. The only source is the proceedings of the annual general assemblies, which listed the stockholders who chose to attend.[71] These documents sustain the impression that ownership was rather heavily concentrated in the hands of a Parisian elite. For 1858, 380 stockholders possessed at least forty-three thousand shares, 40 percent of the outstanding equity. The owners of the merging gas firms still held the largest block of shares: the Dubochet brothers (former owners of the Compagnie parisienne) had 4,580 shares, Louis Margueritte (former owner of the Compagnie anglaise) 2,350 shares, Isaac Pereire 1,500 shares. Among the large stockholders were many titled people and well-known business figures, including members of the Haute Banque (the financial elite of France), Warburg, Mallet, Hentsch, Delessert, and Seillière. Ownership was still concentrated at the end of the golden age. In 1889, 1,047 people held 81 percent of the shares. A comparison of the lists from 1858 and 1889 shows impressive continuity. Families apparently held the PGC's stock over the long run for the sake of the returns. The duchesse de Galliera (1,154 shares), the comte de Grammont (607 shares), and the princesse de Broglie (1,037 shares) all prospered from doing so.

A detailed study of the acts of succession (inheritance tax declarations) for the fourth and fifth arrondissements in 1875 provides some insight

[69] Claude Fohlen, "Entrepreneurship and Management in France in the Nineteenth Century," in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe (Cambridge, 1978), 7(1): 348-373.

[70] Rapport , April 10, 1857, p. 10; May 16, 1865; AP, V 8 O no. 724, deliberations of September 2, 1861.

[71] AP, V 8 O , nos. 908-1001.

into the identity of smaller owners who may not have attended the general assemblies.[72] The findings reinforce the impression of concentrated ownership. Of the 835 estates worth at least five hundred francs declared in these primarily bourgeois districts, eighty-two contained some wealth in the form of stocks. Only six of these held the equity of the PGC; in five of the cases the stocks belonged to women without occupations, and the last case involved a rentier. The average value of their estates was just under sixty thousand francs; each person held an average of seven shares. The portrait is a classical one of small rentiers, who invested in the PGC for the same reason they bought railroad stocks and bonds, to obtain a secure income and long-term capital appreciation.[73]

The PGC did not disappoint either Madame la princesse de Broglie or the small rentier. Dividends, declared every year without exception, rose as high as 165 francs in 1882 and were not below 120 francs after 1875 (see appendix, fig. A5). This represented a return of more than 9 percent on the market value of a share. Those who retained their holdings, as many of the large owners appear to have done, realized considerable capital appreciation (see appendix, fig. A6). The market value of shares rose 54 percent between the beginning of 1862 and the end of 1869 and another 40 percent between 1872 and 1882. Nor were there many sharp drops to frighten the stockholders.[74] The narrow circle of investors in the PGC did very well as a result of their persistence.

The key to profitability was of course the high price of gas that the charter allowed the PGC to charge for fifty years. Regardless of whether thirty centimes was a reasonable rate in 1855, production costs fell by almost a third within the first ten years of operation. The PGC earned around twenty centimes on every cubic meter of gas sold. The company even made about five centimes per cubic meter on the fuel sold for street lighting, which was supposed to be "at cost."[75] Contributing to the handsome state of the PGC'S balance sheet were impressive profits from the marketing of the by-products of coal distillation. The coke that remained in retorts after gas had escaped found wide use in Parisian households for heating. The firm was also fortunate to come into existence just as organic chemicals became essential to industry. Precisely at the moment the artificial dyestuffs industry was taking off, the PGC was one of the world's

[72] AP, D1 Q7 , nos. 11374-11380.

[73] Charles-Albert Michalet, Les Placements des épargnants fran ç ais de 1815 à nos jours (Paris, 1968), pp. 157-179.

[74] The PGC did experience difficulties raising loans during the financial troubles of 1857-1858. See AE V 8 O no. 723, deliberations of May 1, 1858.

[75] Ibid., no. 748, report of November 6, 1856.

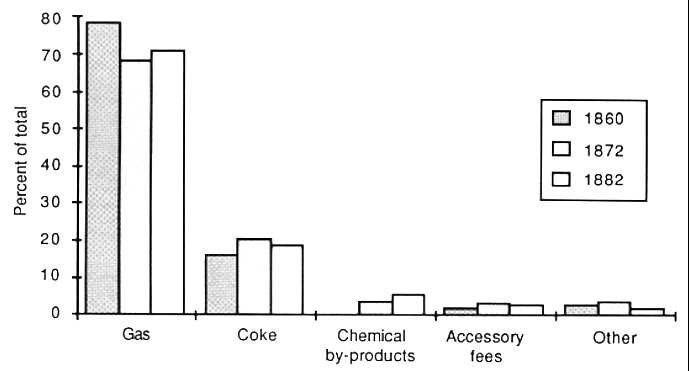

Fig. 2. Sources of Revenue for Selected Years (in percent).

From AP, V 8 O1 , no. 907, Rapports présentés par le Conseil

d'administration à l'Assemblée générale, 1856-1905.

largest suppliers of the essential raw materials, the residues of coal roasting. Naphthalene, aniline, alizarin, benzol, and naphthas all found important industrial uses. Since they were relatively scarce in the 1870s and early 1880s, the price that the PGC received for these former waste products was quite advantageous.[76] Revenues from by-products grew so substantially between 1860 and 1872 that the income derived from gas sales declined from four-fifths to two-thirds of the total (see figure 2).

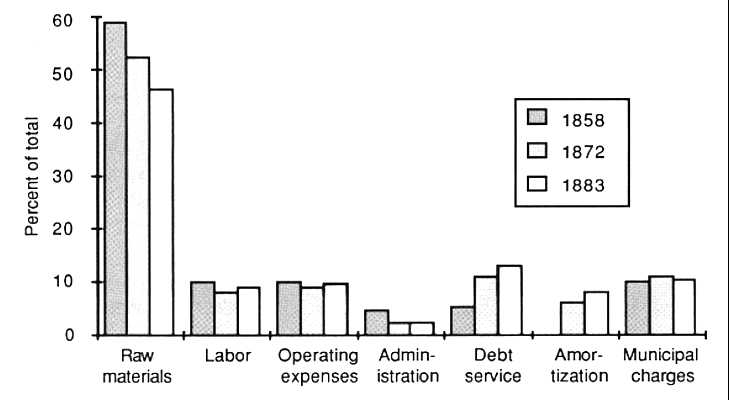

With such assured profits, managers of the PGC might have chosen to overlook wasteful expenditures, but in fact they were extremely conscious of costs. Producing gas and by-products became markedly less expensive in the 1860s as engineers made some basic changes in the organization of labor and in operating procedures (see chapter 4). Their greatest challenge in reducing costs was to save on fuel and coal. Wages accounted for only a small part of operating expenses, but roughly half went to purchase coal, the basic raw material. In the earliest days of the firm there was discussion of acquiring a mine, but nothing came of it.[77] The company took other measures to reduce expenses. Its chief procurement officer received pay based on his success at arranging favorable contracts, and there were several agents on the scene at the developing coal fields of northern France.

[76] Ibid., no. 721, "Instructions de Monsieur Regnauh."

[77] Ibid., no. 723, deliberations of October 17, 1855.

Fig. 3. Distribution of Expenditures for Selected Years (in percent). From AP, V 8 O1 no.

907, Rapports présentés par le Conseil d'administration à l'Assemblée générale, 1856-1905.

The PGC could also take comfort in the fact that when coal prices rose, the company could recoup the loss by charging more for coke. And it did not necessarily have to reduce the coke rates when coal prices fell.

To save money on the roasting of coal was an obsession for production managers. They tinkered endlessly with the mix of fuels, substituting different grades of coal and burning by-products as market conditions dictated. They were even willing to risk angering the touchy stokers, whose hard job was made still more burdensome by constant changes in fuels. The search for the perfect furnace was another constant of managerial activity in the PGC, leading to basic innovations for the gas industry in France. The energetic management seemed rather oblivious to the fact that high gas rates ensured handsome profits regardless of the production costs.[78]

An expenditure the PGC could not control was the amortization of outstanding stocks and bonds. As a corporation with a limited life, these expenses necessarily burgeoned. By the 1880s they already accounted for a tenth of total expenditures—as much as labor—and would continue to put pressure on profit levels (see figure 3). Amortization costs were ex-

[78] Rapport , March 25, 1869, p. 13.

penses of a distinct sort, however, because they went partly to the owners of the company? Moreover, the PGC's negotiators had contrived to have the city pay far more than its share of the expense. The assets Paris would receive in 1906 would never compensate for the contribution it made to amortization costs. Thus stockholders had no real reason to complain about the rising portion of the budget devoted to this expense.