Chapter One—

The Nature of Change, of Place, of Religion

In the very last years of the thirteenth and the first decades of the fourteenth centuries, in Rieti, three men made wills, specific and worrying and personal, which still reveal something of the quality of that part of each of their minds which can reasonably be called "soul." The first of these men was Nicola Cece, a citizen of Rieti but formerly of neighboring Apoleggia, who made a will in 1297, added to it a codicil in 1300, and wrote a new will in 1301; and he made the two wills in the refectory and chapter house of Sant'Agostino, Rieti.[1] The second was Giovanni di don Pandulfo Secinari, or de Secinaro, who made his will in the house of his dead father's sons (one of whom would become bishop) in Rieti, in 1311, but who placed in that will memories of his family's place of origin, Secinaro, across the border of the kingdom of Naples in the diocese of Sulmona.[2] The third was Don Giovanni di magistro Andrea, a canon of Rieti, who made his will in his own house in Rieti in 1319.[3] These wills form an articulate centerpiece in an arc of religious and ecclesiastical history which stretches from Pope Innocent III's heroic pronouncing and defining Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 to the beginning of the papal schism in 1378, and which stretches, with different emphasis and slightly different dating, from Francis of Assisi's brilliant (and, like the Lateran, remembered) presence in the diocese of Rieti in the years before his death in 1226 to the death of the third, and seemingly conventionally successful, Franciscan bishop of Rieti in an earlier part of 1378.

In spite of the sense of decline that one must get from seeing the

Schism and a conventional Franciscan bishop put next to, or rather following at a distance, the Fourth Lateran and Francis of Assisi, this arc or line of almost two hundred years was in a number of ways, some of which were very important, a line of, to use a word generally disliked by medievalists, progress. In 1227 in a precisely, but in a rather clumsily decoratedly formal, imperfect document, vertical, in an almost too careful curial hand, the Reatine citizen and scribe (scriniario ), Magister Matteo, wrote that in his presence Abassa Crescentii had given a letter sealed with the seal of the bishop of Narni to Bertuldo the son of the by then dead Corrado once duke of Spoleto. And Bertuldo had asked, "What is this letter?" And Abassa had answered that it was a letter which pertained to the case between Bertuldo and the church of Santa Maria of Rieti. Bertuldo had not wanted to take the letter, and he had said to Abassa, "Go and stick the letter up the culo of an ass."[4]

In contrast with this blunt command and the document in which it is preserved, one finds the epistolary elegance of formal and verbal content in letters to the church of Rieti from two neighboring territorial noble houses, the Mareri and the Brancaleone di Romagnia, who dominated the southeastern and the southern parts of the diocese in the mid-fourteenth century. These letters, about clerical livings, were written by baronial chancellors of humane accomplishment. They are small and beautiful and sealed with small and beautiful seals; and in them graceful phrase succeeds to graceful phrase. Most elegantly perfect of all perhaps is a paper letter of 1346 (but itself too elegant to bear a year date, only the indiction and the month and day), small (29 x 18 cm), horizontal, with a tiny (1.8 cm in diameter) black seal en placard , from Nicola de Romagnia, in Belmonte, exercising his right of patronage over the church of Santa Rufina in Belmonte and presenting to the chapter (uenerabilibus hominibus ) for that living, dompno Francesco di Sebastiano of Belmonte, and in this matter, reuerendam et uenerabilem paternitatem et amicitiam uestram affectuose rogantes .[5]

The contrast between Uade et mitte (go and stick) and affectuose rogantes (affectionately asking), which seems starkly to juxtapose a bear-like Germanic baron, old style, just stumbling out of his cave, and the Angevin elegance, almost perfumed, of a lord of Romagnia sitting in his airy view-filled palace on the pleasant heights of Belmonte, exaggerates. The Urslingen Bertuldo and the Brancaleone Nicola were both in their ways trying to maintain and protect their rights in property, including ecclesiastical property, and to ensure, presumably, the continued inheritance and prestige of their clans. It should be remembered

that during the period of mid-fourteenth-century central Italian raids and wars, physical savagery was not dead, and that it would be hard to make a case for its declining, and that the first bishop of Rieti actually to be freddato , murdered or assassinated, would be Ludovico Alfani in 1397 in a reaction against the growing tyranny of his, the Alfani, family.[6] Nevertheless the difference between "affectuose rogantes" and "uade et mitte" does signal a real change in Reatine communal and ecclesiastical behavior, a normalization, perhaps even civilization, certainly bureaucratization, which occurred between the early thirteenth and the late fourteenth centuries.

When the first at all complete surviving official records of Reatine communal discussion and action, the Riformanze of 1377, appear, they are productions of accustomed professionalism, elegant, beautifully written and composed by a communal chancellor, Giacomo di fu Rondo, of Amelia, a writer of considerable accomplishment, able exactly to describe the four horses assigned to him by the podestà.[7] In the presence of serious threats and dangers, like the lurking and threatening societas italicorum in Leonessa, the faulty state of fortifications, the lacerations left from recent violent disputes between Guelfs and Ghibellines (and the distinction between these parties, like that between noble and non-noble, is apparent and assumed when the Riformanze commence), and in spite of the expressed worry that since Pope Gregory would be returning into Italy reform would undoubtedly (absque dubio ) be demanded of the city and citizens of Rieti, the chancellor Giacomo, or he who dictated to Giacomo, was not only capable of phrases like "quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur," but also of finding that the greatest fortification that any city can have is concord, and stating the belief that great concord can naturally follow great discord, as after the tempest comes the calm and "post nubilem dat serenum."[8] All this, including the elaborate governmental structure which the Riformanze record, is unthinkable of the primitive communal government established under Innocent III, when Berardo Sprangone (or Sprangono), a local scriniario and judge, almost omnipresent in the documents of the church of Rieti in various guises but chiefly as authenticating scribe, seems to have become the first podestà.[9]

The development that the first Riformanze indicate, which is a development of surface, but not only of surface, is one which occurs, or is parallel to one which occurs, not only in ecclesiastical structure—in the actual organization and in the recording of church government—but in religion itself, in the pattern and space of religious exhilaration.

This is most obviously connected with the kind of pastoral reform which was pressed forward by the Fourth Lateran Council and by the coming, the influence, and the changing nature of the orders of friars—in Rieti most particularly the Franciscans, but also the Dominicans and the Augustinian Hermits. Inseparable from the friar's presence and pastoral reform was the changing interpretation of Christ's message, particularly through Matthew, and the changing understanding of Christ's self—even, again, in the way He looked, in image, out upon His people, and the way His earthly houses changed as they became in a new way His houses. They, these houses, changed physically and noticeably, particularly at Rieti in the creation of the great open, internal spaces of the churches of San Francesco, San Domenico, and Sant'Agostino, which were placed at three points on the periphery of the growing city, in the area between the old walls and the new thirteenth-century walls, as those walls were being built.[10]

This development is present in wills. From 1371 one finds a record of part of the execution of the will of Pietro Berardi Thomaxicti Bocchapeca, alias Pietro Jannis Cecis, of the city of Rieti, in which will, the document says, multa fecit legata , he made many legacies; and one was for the dowries of orphans, or the dowry of an orphan, or of a poor woman. Pietro's executors, among whom the presence of his wife, Colaxia, is emphasized, in order quickly and well to execute his will, searched vigorously through the city of Rieti, pluries et pluries , for poor orphans, and they found Stefania, daughter of the by then dead Gianni di Andrea Herigi; she was a poor, wretched, orphaned person, lacking a father, and a person of good reputation (personam pauperem, miserabilem, orfanam, et patre carente et personam honestam ). The executors settled upon her for her dowry a piece of vineyard in the Contrada Coll'Arcangeli.[11] This testamentary action is, in its way, fully expressed Christian charity of the new sort.

Pietro's, and Colaxia's, is a kind of charity, of interpretation of Christ, much more specific and extended than that suggested by the first relatively long and fully stated will which survives from after the coming of Adenolfo to the bishopric and Innocent III to the papacy, the will of Fragulino, written and authenticated by Berardo Sprangone in 1203. This Fragulino, a man of considerable property, was certainly the same Fragulino who is recorded as having been a consul of the city in 1188 and 1193, and so a man who connected the new governmental world of Berardo Sprangone with that which existed before Innocent III's reforms—a figure who shows continuity, a continuity extended by the

appearance of Fragulino's son, Berardo Fragulini, who gave gifts inter vivos for the sake of his father's soul and his own in 1206.[12]

Fragulino thought of his soul. He left the church of San Ruffo in Rieti 20 soldi for his soul. Without specifying purpose he left 20 soldi to the relatively aristocratic San Basilio of the Hospitallers, and one soldo to San Salvatore, presumably to the great Benedictine monastery south of Rieti and physically within the diocese. For what ought to come to him from the will of his brother Pietro Zote he made the church of Santa Maria his heir for his brother's soul and his own. He left more actual and residual money to Santa Maria and its clergy, 40 soldi (provisini) for the clergy and 14 lire (provisini) for the rebuilding (refectionem ) of the church. To the hospital capitis Arci he left 5 soldi. An uncertain but suggestive spiritual profile is drawn: family; attachment to the parish of San Ruffo, and perhaps to its neighborhood extending to San Basilio, with its tone of caste; a nod to a great old Benedictine monastery; and serious money for the cathedral church of Santa Maria particularly for building at what was probably a crucial point in the church's long building campaign. To this is added the 5 soldi for the hospital. These 5 soldi are in the line of the interpretation of Christ which will send Colaxia again and again through the city of Rieti searching for a poor orphan girl. But in the Fragulino will the interpretation of Christ remains relatively mute. One must imply the Christ of corporal acts of mercy, the Christ of Cana, who directly or indirectly provoked the soldi's giving.

The development from Fragulino to Pietro and Colaxia, however, is not so simply one of opening and blossoming as it at first may seem. Pietro's charity, or at least Colaxia's and her colleagues', is caught in a specifically institutional container. Stefania's vineyard dowry is to be hers only if, within two years time, she enters a monastery of nuns within, or in the immediate neighborhood of, Rieti, and takes her vineyard dowry to that monastery, and if she then dwells in habit there like the other nuns. If Stefania fails in this, the vineyard in Coll'Arcangeli is to go instead to a house of Dominican nuns, Sant'Agnese near Rieti.

Between the making of Fragulino's will and the execution of Pietro's, the great majority of religious thoughts, of those spasms of momentary piety, devotion and charity, which, within the diocese of Rieti, affected men's and women's minds and behavior, are of course untraceable. It might seem impossible with so much lost to try to sketch a line of development in this gauzy material; it is tempting to let it rest and to look only at the relatively solid lines of developing government and

institution. But these latter things are inextricably connected with personal piety, and they lose their meaning if they are detached from its more nebulous material. Besides, much does remain, and much that is poignant and moving as well as puzzling.

This pious and testamentary development took place in and around the small urban capital, Rieti, of a big rustic diocese which stretched to different distances in all directions from the city. In its specific Reatine form the development is inseparable from the place in which and the people among whom it took place. Even in thinking as narrowly as one could about Reatine religion one would have to think about, try to sense and see in some detail, what kind of physical place, or places, the city and diocese were, what kind of and how many people lived there, in what patterns of human settlement and tenure and in what kind of geography (mountains, rivers, plants, animals), with what patterns of speech, image, and behavior, and to know something of what they produced besides prayers and churches, wills and heirs. Moving from city to country, and to town or village, from the rules of a great barony to the many speaking voices of a rural inquest and to the amplified voice of a single reacting bishop perhaps will create, at least, a sounding board for the Reatine sermon.

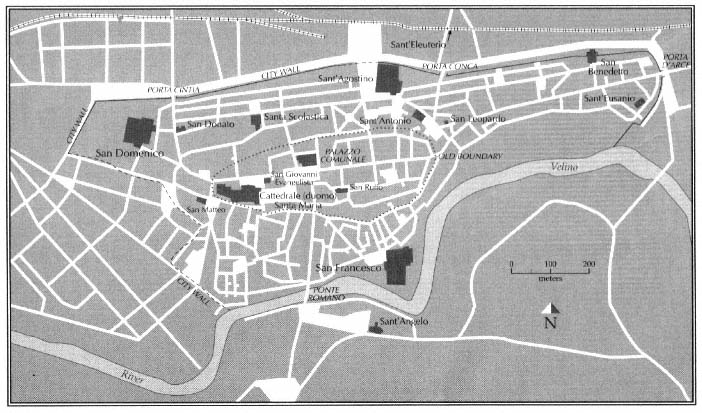

The city itself, for all the surrounding rusticity, was (and is) in the center of Italy and only about eighty kilometers, on the Via Salaria, north and slightly east of Rome.[13] The early thirteenth-century city (plate 9) stretched from west to east in an extended and uneven oval for 1,200 meters (which was at its widest point about 450 meters from north to south) on an outcropping (402 meters above sea level), a ridge above, and north of, the river Velino, where the river was met by the Via Salaria coming from Rome, and where parts of the Roman bridge remain. At the westernmost end and highest part of the ridge stood the cathedral complex with its piazza; close by to the east and slightly to the north developed the building and the area of the palazzo comunale on the site of the Roman forum (see map 3).[14] By the end of the thirteenth century the walled city had been extended in all directions (plate 10) but particularly to the east toward what became the porta d'arce , so that the city's total length from east to west had grown to slightly more than three kilometers. It was extended into the flat land to the north and down the hill to the Velino in the south (plate 11) so that at points it measured a kilometer, or slightly more, from north to south; and it was joined across the Velino, where the river was met by the Via Roma coming down the hill, by a borgo , a suburb, in the neighborhood of the

3.

The city of Rieti.

church of Sant'Angelo. The new walls enclosed the recently established complexes of the Augustinian Hermits to the north (within the wall west of the porta conca ), of the Dominicans to the northwest (in the corner of the city beneath the cathedral and to the west of the porta cintia ) and the Franciscans to the south (actually bound by the Velino not the wall, east of the Via Roma); but they also enclosed another important communal complex, close to and southwest of the Augustinians, the Piazza del Leone, where in the early fourteenth century would be erected the palazzo del podestà.

By the end of the thirteenth century the walls enclosed not only the entire new cathedral dedicated to Santa Maria, which had been consecrated by Pope Honorius III in September 1225, and significant portions of all three of the friars' complexes, but also the new cathedral campanile, which says that it was constructed in or after his first year by Bishop Tommaso (1252–1263/5), and the new episcopal-papal palace which Bishop Pietro da Ferentino (1278–1286) made to be constructed (at the time of the podestà Guglielmo da Orvieto) in 1283, with a loggia added in 1288, under Bishop Andrea (1286–1292/4)—(from the time, as it says, of the podestà, Accoramboni da Tolentino)—and, from just before the turn of the century, the Arco del Vescovo, which bears Pope Boniface VIII's family arms.[15] A list from Bishop Tommaso's time, which does not here include Santa Maria or the friars' churches, does include twenty-nine functioning, or at least census-owing, churches under the rubric: ecclesie de ciuitate.[16] It was to this newly enlarged and monumental complex on its ridge above the Velino (plate 12), that members of the Secinari family, one of whom would become bishop, would come, around 1300, returning from their name-giving Abruzzese village, Secinaro (plate 13), to their Rieti house, perhaps already located in the position of their later palazzo on the Via Roma.[17] The contrast must sometimes have shocked them, but so too, except for scale and monumentality, must sometimes the similarity of the two, Rieti and Secinaro, have been assumed by them, human communities, on their ridges, of normal sorts in the rough pitted terrain in this central part of Italy, in spite of, in Rieti's case, the vastness of the great drying basin to its north.

About the actual population of Rieti, before and after the Black Death, it is only possible to guess. By the end of the sixteenth century, when it is possible to do more than guess, Rieti had a population of around six thousand people.[18] With this figure in mind, and with in mind the comparison of Sulmona, which in the late fourteenth century

reached a similar figure, it certainly seems possible to say that, late in the thirteenth century, at least, Rieti's population could well have reached a figure around four thousand.[19] But this is speculation.

Rieti, once a Sabine center, had, under the Romans, become a Roman city; it was the home of the Flavians and appropriately of the agricultural expert Varro. Under the Lombards it had become part of the duchy of Spoleto. It had been the name-giving center of a gastaldate and then a county, which it remained into the twelfth century. Rieti was the victim of memorable and remembered destruction by Roger of Sicily in 1149. Its recovery and rebuilding were accompanied by the growth of communal government under the local direction of consuls. By the end of the century it had come under papal control.

Rieti's continued existence as a governmental center, if this is not too grand a term, was reinforced by its position as an episcopal see. Its traditions connected it with the blood of martyrs, and a fleeting reference to its church is found in the letters of Gregory the Great. Its episcopal position, and memories, were strengthened by the long and seemingly relatively effective episcopate of the twelfth-century bishop Dodone, at least from 1137 to 1179. Still Rieti remained essentially a secondary market and trading center at the heart of an agricultural and pastoral area dedicated particularly to the production of wine and grains, as well as garden and animal products and fish.[20]

From Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) Rieti received two important but not disinterested gifts. Rieti became a free commune, although not free of an annual census, with its own government organized under a podestà. It also became an intermittent papal residence. The city thus entered the thirteenth century, a period of almost universal demographic growth, the period of the growth of its own walled space, with two shaping advantages. Its communal government was able to survive and develop through two periods of violent disorder in central Italy: the wars between the papacy and the emperor in the second quarter of the thirteenth century and the period of seeming chaos and continuous partisan disruption, warring of private armies, and Neapolitan royal infiltration, from the time of the papal retreat from Italy in 1305 particularly until the coming of the legate Cardinal Albornoz in 1353 and the Reatine agreement with him in 1354.[21] There is considerable evidence, especially from the (in many ways more distracting) latter of the two periods, for the continued ability of communal institutions to focus elements of power, both shifting and continuing, within the city, to allow it, the city, to resist, although certainly with mixed effectiveness,

potentially intrusive external forces, royal and baronial. It could be argued that the efforts of the early Angevin kings of Naples, in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century, to strengthen their Abruzzese borderlands with new income- and defense-regulating, relatively urban, planned and gridded communities, like Cittaducale (plate 14) and Leonessa, not only threatened Rieti but helped it, by placing it within a better ordered general neighborhood, and so in some ways echoed the helpful papal organization of territory and border under Innocent III. Certainly in the absence of the papacy, in spite of the presence of papal governors, Rieti was drawn much more heavily into the ambit of the kings of Naples; and it might have been helpful to Rieti if they in fact had been stronger kings.

But Rieti, with its own constitution developed and intact, and visible within its first statutes and its earliest existing Riformanze, survived; and, in the end, it itself, its urban center, survived outside the borders of the kingdom of Naples.[22] Both the army of Rieti, the exercitus Reat' , camped in siege outside the gate of Lugnano in June 1251, and the (particularly nonclerical) counselors from Rieti, asked to help decide whether or not the heretic Paolo Zoppo should be submitted to torture in 1334, suggest the continual existence of a body of responsible and relatively weighty Reatines, of diverse background, substance, and experience, who in their different ways could represent with their strength and wisdom the more general community—a thing which itself existed, was thought to exist, and which could survive partisan fragmentation.[23] In surprisingly similar terms could be described the composite chapter of Rieti, of the cathedral of Santa Maria, representing its church and community.[24]

Innocent III himself came to Rieti. There in 1198, we are told, he consecrated the church of San Giovanni Evangelista (in Statua).[25] One hundred years later in 1298, Innocent's distant successor Boniface VIII came to Rieti and there, it is reported, threatened by the violent earthquakes of November, he took himself from celebrating Mass to the relative physical safety of the cloister of San Domenico.[26] Five thirteenth-century popes, including Innocent and Boniface, the first and the last, together, spent, with their courts, 1,226 days in Rieti: Innocent III, 28 days; Honorius III, 239 days; Gregory IX, 547 days; Nicholas IV, 302 days; and Boniface VIII, 110 days.[27] Popes came to Rieti eleven times for periods ranging from 28 to 547 days; in terms of time spent there, it was the fifth most popular of thirteenth- (and very late twelfth- and early fourteenth-) century central Italian papal residences outside of

Rome: after Viterbo, Anagni, Orvieto, and Perugia.[28] And the popes did not come alone. They came with hundreds of followers (some of whom preceded them to make arrangements), of whom five hundred or six hundred were direct dependents of the papal curia.[29] They packed or bloated the cities at which they arrived. They drastically altered the cities' demands on housing and public services and provisioning. They pushed rents up to as much as four times their normal figure. Some of them demanded hospitality and in what seemed unreasonably spacious quarters.[30] They caused expensive damage and they required protection.[31] They brought many problems and obvious discomforts to the host community; they threatened its fabric. But on the whole they (and the real or presumed economic benefits of their presence) seem to have been much desired, courted, built for; their potential and actual presence seems generally to have improved the facilities and increased the monumentality of the host city, to which they themselves came for various reasons: to strengthen papal presence in the area, to avoid the danger posed by Roman or Rome-threatening enemies, to escape the pain and illness of a Roman summer in a place as seemingly fresh and cool as Rieti—Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi's sweet Rieti (amena Reate ), beneath its mountains and above its waters.[32]

The exact effects of the curia's presence on Rieti and the negotiations leading to that presence are not visible as they are at Viterbo and Perugia, but clearly the monumental center of Rieti, the papal-episcopal palace (built under curial bishops) and the arch of Boniface VIII are connected with attempts to attract the court to, and/or to keep and please it at, Rieti. So may have been, for example, the important fountain in the Piazza del Leone.[33] The late thirteenth century, between the battle of Tagliacozzo (1268) and the popes' departure from Italy, was a time of relative peace and of monumental building and decorating for central Italy; into this pattern the Rieti palace fits naturally, but its specific reason is surely papal presence.[34]

The papal curia brought the world and the world's events to Rieti. In 1288 and 1289, Pope Nicholas IV spent the summer, from mid-May until mid-October, in Rieti. In Nicholas's second year there, Charles II, the new king of Naples, recently freed from the imprisonment in which he had been held hostage, came, with a great following, to Rieti, and on Pentecost, in the cathedral, was crowned king. In memory of this event Charles promised the church of Rieti an annual gift of 20 uncie of gold from the royal treasury, and so an additional financial benefit came to the city, or at least to its church, from the presence of

the papal curia there; but it was not a benefit without eventual problems or one the installments of which would always come free, as is clear from Bishop Giovanni Papazurri's excommunication, in 1311, of any canon who did not pay his share of the money required in order to get the 20 uncie from King Robert, and also in 1332, from the making of proctors by Bishop Giovanni's vicar and the canons of Rieti to appear before the king and dissuade him from any reduction of the sum. In the papal-royal summer of 1289 Rieti was further swollen by the presence there of the thirteenth chapter general of the Franciscan friars minor, men from all over.[35]

The chapter general calls attention to the provenance of the friars resident in the local houses of Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinian Hermits.[36] They were not from the whole world, and they were not all strangers, but the majority of those who can be identified did not come from Rieti or nearby villages but rather from other Italian places. In the early fourteenth century, after the second of the two periods of papal sojourns, and after many Reatines had themselves become members or followers of the papal curia, Rieti, with its Roman Papazurri bishop, was certainly not a place sealed against the outside world. Witnesses and actors who appear, for example, in the parchment cartulary of Matteo Barnabei, for the five-year period 1315–1319, suggest a generous presence of resident strangers.[37] There were signal figures with specific skills: Janductio the painter from Rome, and Magister Jacques, the physician from the diocese of Le Puy-en-Velay (Pandecoste), who had become a resident and medico of Rieti; but there were plenty of others, of course, from neighboring places like Labro, Morro, Greccio, Monteleone, Montereale, Poggio Bustone, but also from more distant and distinct places like Viterbo, Norcia, and Siena, and a sizable number from Rome.

Not all Reatines were Christians. There were Jews in Rieti in 1341, and the nature of their appearance makes it clear that they had been there for some time, if not in great number.[38] On 1 April 1341 in the house of Vanni di Don Tommaso Cimini (or de Ciminis), with as a witness Matteo di don Filippo Pasinelli, "Manuelis Consilii Judeus" came forward to act for himself and a group of some ten named associates, from a somewhat smaller group of families, men with names like those of the brothers (in the genitive) Abrammi and Salomoni alias Bonaventure , sons of the now dead Magister Bengiamini —a high proportion of magistri . Manuelis was present to come to an agreement, to end discord and litigation, with the brothers Musictus and Gagius, sons

and heirs of the by then dead Magister Elya Muse, who had formerly formed a part of the association or shop (apotheca ) which Manuelis represented. The two brothers received, in addition to anything they had received from the association in the past, 110 florins of gold, accepting an Aquilian stipulation (the conversion into a single stipulation of a variety of obligations); and in return they gave up any share in current actions or debts being pursued against or from the city of Rieti or any person within it. They promised not to stay in future in the city or county of Rieti more than two days a month and not to have there a shop or mercantiam without the express license of Manuelis and his associates. Juxta, the wife of Gagius, consented to this transaction and waived all privileges and remedies at law protecting wives, including privileges guaranteed by the city of Rieti. This document establishes the existence of a self-controlled, in some ways at least, corporation of money-lending Jews in Rieti in 1341, which seems to have operated within perfectly recognizable community procedures, and which was able to act with a witness from one of Rieti's most prominent patrician families in the house of a member of another of those families. The document suggests that these men with their families were the only Jews in Rieti, that there was only one such consortium; and that suggestion would seem to be supported by a legacy in the will of Don Berardo de Colle from the same year 1341: Item dixit se debere dare Judeis qui habitant Reate. v flor. aur. quos eis reliquid (He said that he ought to give the Jews who live in Rieti five florins of gold, which he leaves to them).[39] Whether or not this formula was sufficient to remove the florins from a category of immediately payable debt (as it presumably was intended to do), it certainly seems to imply a single recognizable receiving body.

The community of Rieti, the city, divided into its three double porte , its six sestieri , in which Jews, foreigners, painters, doctors, notaries ,patricians, women from Labro and Greccio, friars, and priests lived, was, by the end of the Middle Ages, or was meant to be, regulated by a composite body of communal statutes. Some of its contents come from the time of Bishop Biagio da Leonessa (1347–1378): a compact between bishop and commune arrived at in September 1353 clearly does.[40] But some are, or at least one is, clearly considerably later; the section de feriis , which refers to the feast of San Bernardino, is.[41]

The statutes present a city preoccupied with the problems common to late medieval communes, from the organization of government and the restrictions on governmental office to public hygiene: the faith and

the honor of the Roman church are to be preserved and the podestà is to be elected, communal notaries and communal bells are regulated; the expenses of construction for the fountain in the Piazza del Leone are apportioned to neighbors and neighbors defined; guilds are numbered and named; testaments and torture are regulated; the salary of the city's master of grammar is fixed at 40 lire for the year; the trimming of the limbs of fruit- and nut-bearing trees (olives, figs, almonds, filberts, walnuts, others) is regulated; Rieti with a mile-wide belt of land around it, is protected from the playing of dice—and the continued use, of a sort, of the statute book is indicated by a drawing in the margin of three dice (with a 2, a 3, and a 6 facing the reader); people in Rieti are forbidden to keep pigs in the city—and in the margin a belled pig suggests its filthiness; women of ill fame are forbidden to hang around any monastery or religious place in the city or borgo or any place in the city except next to the city walls and the road that runs by it—and an ambiguous, perhaps suggestive, drawing appears in the margin; the maintenance of fortifications and bridges is regulated. The use of injurious words is forbidden; and there is an attempt to keep housewives from being raped in mills.[42] The city declares its special rights over the "valley of the Canera" and indicates some of the places that are meant, in this sense, to be included in the valley: Santa Croce, Greccio, Rocca Alatri, Contigliano, Collebaccaro, Cerchiara, Poggio Perugino, and Poggio Fidoni.[43]

The statutes regulate the public behavior of mourners and the course of the palium to be run on the feast of Saint Mary in August (the Assumption, 15 August).[44] And with these last regulations one observes an aspect of this set of statutes which should have been suggested by its pious and ecclesiastical beginning: it is not simply secular; it involves itself with pious act and religion. Alms from the gabella are to go to San Francesco, San Domenico, Sant'Agostino and suburban, Cistercian San Pastore.[45] On the feast of Saint James in May (Saints Philip and James, 1 May) the podestà is personally to go to the church of San Giovanni Evangelista (in which vox populi firmata fuit ) and there to offer, to the praise and honor of God and the honor of the people of Rieti, a ten-pound candle or torch to be lighted when the Corpus Christi is elevated; and then, that offering made, he, the podestà, and the captain of the people and the priori are to proceed to the church of San Giacomo and make a similar offering.[46] The local presence and miracles of Saint Francis are recalled, as the presence of Greccio, Fonte Colombo, and Poggio Bustone (plate 15) still testified, and the friars of

Rieti, and the monastery of San Fabiano, of the order of Saint Clare, or, as the statutes also say, the second order of Saint Francis—all to be borne in affection by the Reatines.[47] The church of Saint Francis in fact performed functions, physical ones of housing, for the operation of Reatine government, but the relations of the city with the great abbey of San Salvatore Maggiore seem to have been more complicatedly possessive; and the statutes insist that no one commit an offense in the lands of the abbey.[48] Hospitals, too, were protected.[49] But so were the city's rights of clerical patronage at Monte Calvo.[50]

It should be clear and unsurprising that at Rieti there was in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, through 1378, a continuous convergence of secular-civil and ecclesiastical institutions; the city in its various aspects came from (or produced) the same mold. Except, of course, for the imported and transient major figures of podestà and captain, the same men and, more, the same families (and the same external forces) appear in the recorded workings of both secular and ecclesiastical institutions. But secular Rieti was not a tightly controlled unitary thing; it was various, rather loosely organized, and, in its way, popular. One would not expect, and one could not find, in the Rieti of the period before 1378, the kind of structured secular-ecclesiastical coherence, with secular domination, that has recently been shown to have existed, for example, in the Verona ruled by the Scaligeri between 1277 and 1387.[51]

At the figurative center of the Rieti complex the palazzo comunale and the palazzo episcopale sat in very close physical proximity, the extended governmental center, insofar as it was local, and concentrated, of the whole place. But it could reasonably be argued that the real center of the community was not in palazzo but in chiesa , the high altar of the cathedral church and that church's sacristy where its treasure was stored. Of that treasure, of the goods which were found in the sacristy of Rieti on 15 January 1353, the chamberlain canon Ballovino di magistro Giovanni and his two sacristans, dompno Nutio di Pandulfictio and dompno Francesco di Pietro, have left us a list beginning with four chalices all of silver, all gilded, and three also enameled, all with patens.[52] The list includes miters and crosses (one little one of silver which the bishop wore around his neck when he was celebrant), an episcopal ring, sandals, vestments of various colors, fifty silk altar and/or other cloths and duo palia que portauit ser Petrus Zutri de Florentia , boxes, candelabra, documents and privileges of various sorts (like Pope Nicholas IV's grant of an indulgence of a year and forty days for the church of Rieti—the first listed), and books.

There is a list of ninety-eight books, with some suggestion of their order.[53] There is some talk of their size, their lettering, their binding and condition, their glosses, the signs (like call numbers) which distinguish a few of them. There are missals, antiphonals, an evangelary, an epistolary, a hymnal, responsories, legendaries, passional, breviaries, office books of various sorts, psalters, Bibles, books of the Bible from both testaments, Paul, books of prayer, scholarly books (some) and books of devotion, books of medicine (a number, including one specified as Constantine on fevers translated from the Arabic), books of laws or canons (not many or modern), Isidore, histories (including one specified as a history of the Franks and the Lombards), lives of the saints, classics (Cicero on rhetoric, fifty homilies of Augustine, Josephus, Gregory on Job or a book commenting on Gregory's Moralia ). There is a "de mirabilis mundi," a treatise on the eight deadly sins, a "vite patrum" (desert fathers lying in wait to snare a soul), a "librum tabulatum de vita beati Thome" (unidentified, but probably Becket of Canterbury). There is in closing a librarian's or a bibliographer's plaint "Item sex quaterni dissoluti de diuersibus rebus." There is also a short list of recent gifts by canons which suggests modern or personal taste, miracles of the Virgin, legende of the saints, sermons for Sundays:

Item librum miraculorum Sancte Marie nouum quem fecit fieri dominus Johannes de Ponticillis, canonicus Reatinus

Item simile alius antiqum

Item librum de legendis sanctorum per totum annum quem fecit fieri dominus Raynallus de Plagis, canonicus Reatinus

Item librum de sermonibus dominicalibus quem fecit fieri dominus Bartholomeus Bontempi canonicus Reatinus

and elsewhere in the list is a new psalter which Bartolomeo Alfani had had made:

Item aliud psalterium tabulatum quem fecit fieri seu dimisit dominus Bartholomeus Alfani.[54]

We are shown a rather old-fashioned country library of reasonable size, unprofessional, except for the profession of praying and perhaps home medicine.

These books and these chalices, the episcopal ring and the life of Thomas were at the center of the community, and the diocese, and occupied the mind of the canon chamberlain Ballovino in 1353. The property which the church and chapter held and which, in part, sup-

ported them, moves the observer's eye back out into the community. An inquest of holdings, in one example, from 1225 and the years just after that, was copied in the early fourteenth century, presumably in 1315, onto surviving paper gatherings of eight folios each. The inquest is divided into three parts, one for each of the double porte , the paired sestieri , of the city: Porta Carceraria, Porta Romana, and Porta Cintia—of which the first once contained 87 entries, the second 42, and the last (the Cintia) 225. The entries of the first gathering of the paper copy move through property over which the church claimed rights across the city to the east in, again, the Porta Carceraria, particularly in the parishes of San Giovenale and San Giorgio; of the 69 items in the first gathering 10 refer to properties in the parish of San Giovenale and 16 to properties in San Giorgio.[55] But other parts of then eastern Rieti are marked out, the parish of San Leopardo, or, in the case of the property of Matteo Allecerati, property in the porta nova in the parish of San Paolo, and other property an actigale (? a hut? a straw hut) outside the porta sancti pauli , bordered by the tanus , a public street, and the carbonaria . And one is told of the tiniosus flaianus (a memory), of a tower "Bertesce," of the river, the city wall (at the edge of a property in San Giovenale), the Arce.[56]

But although the initial part of the inquest certainly seems to be an inquest of the area of the Carceraria, it is of the area in this sense: it asks responses of people denizened there who hold property of Santa Maria, or over whose property Santa Maria has or claims rights. So in some ways the inquest is very much about people, about property holders; they are listed on its left margins. On specific days before specific witnesses they speak, and sometimes still in the first person. Oderiscio Raynerii, speaking of land he had bought from Senebaldo Gerardo says "ipse mihi dixit quod unus pasus est Ecclesie quando mihi vendidit (he told me one piece was the church's when he sold it to me )"; and Andrea Rustici says "et viam per quam vado ad vineam est ecclesie (the road or path on which I go to the vineyard is the church's)" and for it he gives the church each year one sarcinam of wine.[57] But in another sense, and more seriously perhaps, the inquest is about property, arable land and vineyards, as well as lots, and some garden and huts, and this land is not at all restricted to the city: there are references to five vineyards and a piece of arable at, or on, Monte Marone, southeast of the city, but also three references to pieces of land at Terria, northwest of the city; there are vineyards and land in Conca Maiu in the Campo Reatino, in Padula (northeast of the city), in Casamascara and Saletto to the west,

in Valle Racula, in Pratu Moro or Mori, in Vango, in Trivio San Giovanni—in those areas stretching out from the city in which the church and its tenants could grow grain or vines. The majority of the tenants held property in the country as well as, one assumes, in the city. Much of the property was held jointly: over forty joint tenancies are recorded in these eight folios, mostly by members of extended families with specifically stated relationships ("with my brother and my nephew"). A man answers for his wife, two widows for their sons.[58] Some of the names are specifically interesting. One tenant has the locally important name (or patronymic) Carsidonei. One is identified as "Thomas Scriniarius," and one as "Raynutius Molenarius"; and there is a reference to "Magister Petrus Conpange." A tenant is called Crescentio Maccabei, which could possibly suggest that he was Jewish.[59] Some of these men have the remembered importance of three patronymics, or two and a surname: "Bartholomeus Petri Johannis Theotonici," "Thomas Palmerii Berardi Aliverii"; but the lack of need for any patronymic might argue equal prominence: "Nicolaus Terradanus." There is reference to property held by a man identified as being from as far away as Valle Antrodoco, and by one from Apoleggia.[60] On the other hand, repeated patronymics suggest a less open and extended group than mere numbers might, a kind of closing in, particularly in the case of the Tedemarii (if this name has not in fact started at least turning itself into a surname, which would not alter the point).

Although they are in various places, the lands attached to Santa Maria surround each other in those places: the vineyard of Teodino Tasconis in Conca Maiu is surrounded ab omnibus lateribus (by land held of) Sancta Maria ; the land of Rubeus Stracti at portum cecorum in the parish of San Giorgio is bordered on one side by a public street and a tribus lateribus Sancta Maria ; the lot of Nicola Terradanus in the parish of San Giorgio in the portu Pellipariorum (? of the tanners) has before it the public street, behind it the river, and on the other side Santa Maria; and the lot of Andrea Severi Travasacti has ab uno latere flumen ab aliis lateribus Sancta Maria : the devil, one feels, in this little world, and the deep blue sea.[61] But can one say of this devil that it has lots of land? Whose is the land, Andrea's or Santa Maria's? Although there is some talk, very rare, of how land is held ( emphiteotectico jure ), there is no talk of specific returns, or very, very little, such as the sarcina of wine.[62] These may be stories of memories of larger tracts once held by Santa Maria and later divided: memories already in the time of Bishop Rainaldo de Labro, grown more distant but of renewed interest in the

time of Bishop Giovanni Papazurri—not major sources of income in the time of Bishop Biagio da Leonessa.

The chapter's inquest, like the city statutes' securing of the adherence of the towns in the valley of the Canera and their talk of San Salvatore, San Pastore, and the Franciscan hermitages, takes one outside the city walls to the near country, not in these cases generally to identical places, but to places with the same sorts of closeness to the city, forming the same kinds of neighborhood in the nearest reaches of the big diocese of Rieti. At its most distant from its episcopal city the diocese stretched away to the northeast past Campotosto (if one measures simply by drawing a straight line) for more than forty-seven kilometers, and to the southeastern past Corvaro and Cartore for more than fifty-two; although its boundary to the east past Contigliano was hardly more than ten kilometers from Rieti. The physical size of the diocese changed drastically in the mid-thirteenth century, when in 1256 and 1257 Pope Alexander IV constituted the new diocese of L'Aquila and removed (or began to remove) from Rieti much of the large territory of Amiterno to the east of Rieti and to the west of the new city of L'Aquila, and reduced the surface of the diocese from an area of about thirty-five hundred square kilometers to one of about three thousand.[63]

As in the case of the city of Rieti, it is impossible to know the actual population of the thirteenth- or fourteenth-century diocese. When population is relatively knowable, because of visitation records, at the end of the sixteenth and beginning of the seventeenth century, it has been estimated by the historian Vincenzo Di Flavio to have been between 30,000 and 35,000 (between five and six times the size of the population of the city of Rieti) and to have been scattered in about 220 settlements ("villaggi, castelli, o terre"), with a median population of between 150 and 300, with only a few, like Antrodoco or Campotosto, actually reaching a figure of 1,000 or more.[64] Elsewhere Di Flavio has described the early modern diocese as being mountainous, and particularly sharply so in its Abruzzese parts, with a kind of settlement characteristic of central Italy (plate 16): lots of small villages at short distances from each other ("molti piccoli villaggi a breve distanza fra loro").[65] Between the beginning of the thirteenth century and Di Flavio's observed time there certainly had been specific changes in the arrangement of population centers, most sharply noticeable in the creation of the new towns of the Regno, the Angevin kingdom of Naples, like Cittaducale and Posta, and there almost surely had been growth, irregular growth and in actual numbers unmeasurable, after the demographic recession of the four-

teenth century; but the general pattern which he suggests does not conflict with, but rather coincides with, the evidence for the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The political, in the grand sense, situation of the diocese, before, during, and after the period of this study, was extraordinary. As Di Flavio says of his time, and it seems generally to have been true, with minor variations (as during the period of Angevin encroachment in the fourteenth century), from the end of the twelfth century until Unification, roughly two-thirds of the diocese was within the kingdom of Naples and one-third was within the states of the Church.[66] At the time of the compilation, in the twelfth century, of the Catalogus baronum of the old Norman kingdom, Cantalice (about eight kilometers, in a straight line) northeast of Rieti was within the Regno, but its immediate neighbor Poggio Bustone was not (nor were the other Franciscan hermitage sites). Rieti's western neighbors Lugnano, Canetra, Pendenza, and slightly farther south, Caprodossa, Stàffoli and Petrella, were all within the Regno; the border was close to, but not identical with, the River Salto as the border followed the river up, from its confluence with the Velino, into the Cicolano; the border seems to have crossed the river at least twice.[67] Thus, to use (of course importantly inappropriate) modern parlance, the diocese was in two countries: the border's path did not find its reason, in any obvious way, in physical geography or what would have seemed the more general social connection or rather lack of connection between neighboring communities, but instead probably, at this stage, the "national" border found its reason in the early pattern of military tenements held of the kings of Sicily.

The physical geography of the diocese was not totally incoherent and became somewhat more coherent after the removal to L'Aquila of Amiterno. At the diocese's administrative and population center was the relatively vast alluvial plain, the conca di Rieti (plate 17), once the site of a large lake fed by the river Velino. The conca is, in fact, similar to other large fertile plains or basins inserted in the Abruzzese mountainous areas of central Italy: L'Aquila, Sulmona, Fucino, Leonessa. Around Rieti's alluvial center, and its high terraces of sandy clay, rise sharply the limestone highlands and mountains, the Monti Sabini, the Monti Reatini (rising at their greatest height, at Terminillo, to 2,213 meters), and the northwestern rim of the Monti Carseolani.[68] The Reatini and the Sabini enclose the conca to the north and mark the northwestern boundaries of the diocese. South of Rieti, itself raised above the southeastern edge of the alluvial flatlands, the valleys of the rivers Turano and

Salto make approximately parallel cuts into the southern terraces (as one follows the rivers upstream), and the Velino valley goes off to the east. This area—alluvial flatlands, surrounded by high terraces cut by river valleys, and they in turn surrounded by mountains (or high limestone hills)—forms the rational geographical center of the diocese. To this part of the diocese was joined the upper valley of the Velino, from its sharp turn north at Antrodoco (as one follows it upstream) to its source beyond Cittareale, and the parallel valley of that part of the Aterna which remained in the diocese, after the departure of Amiterno, from south of Marana to the river's source beyond Aringo. This northeastern part of the diocese, the two valleys, with the area between them (with centers as important as Borbona) and areas farther cast including Capitignano and Campotosto, was clearly that part of the diocese least closely tied to its center, a point made particularly clear by the existence for it of a separate vicar general at Montereale in the mid-fourteenth century. It was an area of mixed agrarian value, mixed topography, but it included areas of at least great agricultural potential.[69]

Pierre Toubert, in a lyric moment, has talked of the Sabina's, including the Reatine Sabina's, smiling heights and beautiful landscape where orchards and vineyards and fields of grain are mixed together: "ridenti paesi d'altura ed il suo bel paesaggio, dove l'arboricultura si unisce alla coltura della vite e dei cereali."[70] In another place, in what may be the most memorable section of his major book on medieval Lazio, Toubert, with his constant interest in words, has brought into focus with the blossoming of modern Sabina, including again the Reatine Sabina, the blossoming and leaving botany of its medieval past (where blossoming and leaving were not forbidden by bare, or almost bare, limestone or great height). Place names make that vegetable past visible. Greccio is heather. Sambuco is elder. Ginestra is broom. Dogwood, red cane, fennel, laurel, hawthorn, oaks (quercus and robur ), fern, willows are as alive in the names on the land as olives and chestnuts are in the documents.[71] Toubert's Rieti had the "climat de colline," and around it stretching out into the Abruzzi mountains, in the nature-filled environment, the plains, scattered, seeded through the mountains, had the determining role in the occupation of the soil, in, obviously, the raising of cereal grains (wheat, spelt, barley, rye, millet, panic, sorghum [sagina ], but not apparently oats, or not many oats), and more tangentially in the placing of rows of vines, and the gathering of chestnuts.[72] Olives had an extra dimension; their line of possible growth passes through the diocese of Rieti. Where men were in the diocese

there were gardens, fruit, the pear, the apple, the cultivated nut, and noticeably the leek—remembered still in repeated luscious physicality, on the dinner table of the Last Supper in the late thirteenth-century frescoes at Fossa, in the diocese of L'Aquila, on, or off, the road between Rieti and Secinaro (plate 19).[73]

The diocese was also not only a land of castri or walled settlements on hills, but of castles, with barons in them. The city of Rieti itself may be seen as having been more disturbed by the rivalries, or impertinences, of neigh boring towns, particularly those within the Regno, but the local barons (who, or many among them, would eventually be replaced by the great barons of Rome) were of vital importance to the area of the diocese, to its rule and organization, and to the structure and peopling of its church. Although it is not easy to examine them individually, these barons give no sign of having been identical with one another, cut from the same pattern. The lords of Labro in the mountains just to the north of the conca, with their castle or castles in the papal states, do not seem in all ways like the lords of Mareri to the south, with some of their block of territory in the papal states, but essentially men of the Regno. The lords of Labro, who fought against the lords of Luco, and who seem to have been closely connected with the lords of neighboring Morro, were very important to Santa Maria Rieti as neighbors but also as participants in its most important functions, as canons, as bishop.[74] In spite, however, of their relatively easy identification with the family Nobili by some more recent historians, they are hard to identify, to separate, to pin down; some contemporary records suggest that they participated in a kind of consortium, a kind of barons' cooperative, in which the relations of the members one to another are no longer visible. And of course it is not always possible to say when a man is identified as "de Labro" whether he was a lord of Labro or simply someone who came from the castro ; the presence or absence of dominus is not always decisive, and the use of grander titles for local barons is sparing in the records of the Reatine.[75] In the fourteenth century, as the walls of San Giacomo degli Incurabili in Rome tell us, a Labro had found attachment to a Colonna; in the thirteenth century another Labro was in the household of Cardinal Ottaviano Ubaldini, perhaps related to him, and later became archdeacon of Bologna. In July 1296 the Sienese chose the nobili viro Tommaso de Labro, ciui reatino (in the dative), as their podestà.[76] The Labro were locally important landowners who were able to fight. They were not without good connections. They commanded an imposing castle-castro still very striking on its height.[77] But there is no suggestion

that they by themselves controlled in almost every way the massive domain of an almost royal substate.

Quite the opposite was true of the Mareri in the southern part of the diocese. By the time of the compilation of their late fourteenth-century "statutes," if the "statutes" are (and there is no reason to believe that they are not) a statement of conditions which then pretty much existed, the Mareri ruled a state which extended itself for considerable distance on both sides of the river Salto and, at one point at least, west across the intervening hills and high terraces (hospitable at least at times to transhumants) to the east bank of the river Turano, although this statement in a way distorts the "statutes'" own system of mapping, castro by castro. But, in any case, the Mareri were locally very gran' signori .

The surviving "statutes" list, in varying detail, the Mareri lords' rights, and the obligations of the denizens of each castro, for Petrella Salto, Castel di Tora (Castelvecchio), Rigatti, Marcetelli, Mareri, "Vallebona" (? at Colle di Sponga), Stàffoli, Poggio Poponesco (Fiamignano), Gamagna, Sambuco, Poggio Viano, Radicaro, and Castro Rocca Alberici or Alberti. Mareri control was very broadly imagined and realized. It was deep and heavy. The Mareri seem to have regulated almost every area of castro life: mills, justice, the bearing of arms, the selling of wine, the selling of meat, of dairy products and fish, of cloth, of oil and honey. They demanded hospitality for their messengers and familiars. The lord had rights over the piazza and fixed tolls for whoever crossed it, depending upon what he or she took across it: a horse or a mule, a cow or an ass, a goat or a sheep, wine, grain, cloth, wax, honey, leather, "spices," whatever the mind of the Cicolano could think of someone's profitably carrying.[78] Of every head of cattle raised in Petrella, when it was butchered, the lord should receive a haunch; from everyone the lord should receive a lamb, a cordiscum , and cordisci are defined as all lambs born between 1 March and 15 August ("videlicet omnes agnos qui nascuntur a kalendis martij usque ad sanctam Mariam de mense agusti").[79]

The lord had fortifications and houses. He had the watercourses; he had mountains and pastures. He fixed the time of the vintage. The lord had rights of hunting; and when he went to hunt the hare in any wood in his barony the men of that castro who had snares or hounds were bound to go with him, and when he went for the wild boar, men were to come with arms and dogs. The men of the place could not trap without license; what, licensed, they took, lost its head and a fourth part to the lord. Of partridges and other birds, hedgehogs, and hares,

the lord got a half. No real property could be alienated without license, and an entry fee was to be fixed for anyone coming into property. "Nobles" found in the castro owed aid, suit of court, service. Weights and measures were regulated. Rents, dues, and services were fixed in several castri with men, women, and heirs listed next to that which they must pay (including lots of chickens and eggs).

The Mareri laid a heavy hand on the men they controlled. They seem absolute lords. But of course the very recording suggests a limit to their absolutism, to their depredation. And the significance of this written limitation, of writing things down, is suggested by the recorded presence of notaries in the area, and by the very real prominence of one notary, who appears, and whose wealth and importance appear, repeatedly: Giovanni de Lutta. Still the lords' control is great and clearly expressed. Of his half of Castel di Tora, the lord Lippo Mareri claims for himself and his heirs quite complete banal jurisdiction over present and future inhabitants "merum et mistum imperium cum gladii potestate et potest regere ibi curiam per se et vicarium eius et exercere iudicium ordinarium in civilibus et criminalibus et homines dicte medietatis corregere et punire ad eius voluntatem et arbitrium"; and also it is claimed, "Et homines ipsius castri [should acknowledge] nullum alium dominum et superiorem nisi solum Deum et dominos de Marerio"—only God and the lords of Mareri.[80] Naturally the lords of Mareri concerned themselves with churches.

In the small castro of Stàffoli, now so spare and reduced that its few stone houses seem to be returning to the limestone mountainside on which they lie and from which they came, the northernmost of the places of the surviving statutes, where the Mareri lords had their eyes on littering sows, so that from each litter, after it had been cared for at least for its first three weeks, a piglet must go to the lord's curia ; this was to happen as was said "in the vernacular quando la scrofa latanta ." As elsewhere, the Mareri lord dealt with the church. "He has the church of San Giovanni, which is archipresbiteratus [an archpriest's church, a pieve , baptismal and presumably collegiate], and is outside the castro. He has the church of Sant'Angelo, which is inside the castro. He has the church of San Nicola, which is outside the castro. He has the church of Santa Maria Sconzie, which the abbot of San Salvatore confirms [? accepts there provided benefice holders]. Of these churches the Lord Lippo is lord and patron."[81]

For larger Petrella, there is, as one would expect, more to say; including the restriction that no one could found or endow churches or

chapels there without the lord's license. But in fact in Petrella there are two patrons who are not Mareri: of San Silvestro, the heirs of dompno Giovanni Protempze; and of the chapel of San Nicola in the church of Santa Maria di Petrella, the notary Giovanni de Lutta and his heirs—they are patrons of this chapel, founded and endowed by them, by the license of Lord Lippo and the bishop of Rieti. But the lord has the patronage of Santa Maria itself, whose parishioners all the men of Petrella are, and other existing churches and chapels, and the statute continues: "Et omnium ecclesiarum et capellarum que in postero hedificabuntur ipse dominus debet esse verus patronus et dominus et representare in eis clericos et rectores (he is the patron of all churches yet unbuilt; the church of Petrella shall always be his)."[82] But, the historian Andrea Di Nicola has noted, in only one church properly within the diocese, does a statute seem to withhold from the bishop what would normally be his: of the chapel of San Giovanni in the rocca Castel Mareri, it is said "et est ipsa capella libera ab omni servitio papali et episcopali."[83]

As the statement about Santa Maria di Petrella shows, the Mareri fief (with its additions) is divided into parishes full of parishioners. A large number of the people in the castri, moreover, present themselves, with their names, to be counted; some of these places offer more information for estimating population than anyplace else in the fourteenth-century diocese. For "Villa de Illicis" a frazione of Marcetelli are listed twenty-one homines dicti castri , men and women, including the last named "mastro Angelutius," held, presumably as heads of households, to services; Marcetello itself, with perhaps less pretense to complete inclusiveness has fifty. Rigatti lists sixty-one names, presumably representing households (a number of them listed as heredes ), besides fourteen forenses , people from Marcetelli, Vallececa, Varco, and Poggio (? Vittiano) including a notary from there.[84] These people are listed merely as people who owe rents and services, but in their enumeration they press forward a strong sense of their individual and group existence. And it is perhaps not too much to say that a strong and penetrating government always produces a group of governed with the potential of reacting in group to that government.

The formidable Mareri, in the early thirteenth century, gave the church of Rieti a very visible, at least at one point, canon, and they gave the diocese its most effectively remembered "saint." But their statutes come from (or just after) the end of the period of this study. From near its beginning, and from farther up the course of the Salto, and actually

from a place on a tributary of one of the Salto's tributaries, fourteen and one-half kilometers (in a straight line) southeast of Castel Mareri, come a set of documents, a set of witnesses' testimonies, that reveal the diocese as a place in a more directly ecclesiastical way. They come from, or are about, the church of San Leopardo near Borgocollefegato. It, like the Mareri places, is in the Cicolano, the most distinctive region of the diocese, most internally connected and self-conscious, which stretches itself along the valley of the Salto southeast in the direction of the Montagne della Duchessa and Monte Velino.

Some time around the year 1210, when Transarico was abbot of Ferentillo, and his nephew Transarico was already a monk there, as was Jericho, and when Adenolfo de Lavareta seems surely still to have been bishop of Rieti, but equally certainly no longer an unconsecrated "elect," the Benedictine abbey of San Pietro di Ferentillo, locally within the diocese of Spoleto, and the bishop and church of Rieti were involved in a dispute about jurisdiction over San Leopardo and its clerks.[85] In itself it was not an unusual kind of dispute. It was not very unlike the closely contemporary dispute between the monastery of San Quirico in Rieti diocese and the bishop of Penne, over churches and clerks in the diocese of Penne. In cases like these, distant and recent history combined to make unclear and debatable the jurisdictional boundary between the rights of two claimants, both of whom had some reason to believe that jurisdiction was or should be theirs. At the moment of the actual disputes, frequently, some local disposition—like a temporary period of relative peace and order—or something more general—like the expansion of the accepted notion of episcopal jurisdiction of the sort encouraged by Innocent III, or even an extended sense of parish reality—pushed the parties into the need to define, to establish control, and so to litigate.

In the San Leopardo dispute, the witnesses interrogated (men who had traveled with or observed bishops of Rieti and men local to the place in dispute, at least those witness from whom testimony is preserved) were asked questions about things that they had seen or heard or in some way knew. And in answering these questions they, in various ways, described part of the diocese of Rieti in the early thirteenth century, and also in fact quite deep back into the twelfth century. They produced this depth because some of their memories, and among them some extended by the memories of others, were very long, or at least they thought or said that they were very long.

One witness said that he was almost one hundred years old and that

for his whole life, except for one year, he had made continuous residence at San Leopardo and so he knew what had and had not happened there. Another witness, the farmer named Rollando, said that he had often heard, from the old men of the paese , to whom the church belonged (pertinebat ), and it was to San Pietro Ferentillo.[86] He also said that the clerks of San Leopardo got their crisma , oleum sanctum , and oleum infirmorum from the church of Santo Stefano of Corvaro, which est ecclesie Reat' . Another farmer (agricola ), Andrea, said that he saw the messenger of Gentile de Amiterno, who was called Giovanni Castelli, come to the church, close the gates (ianuas ), extract the keys, and give them to a monk called Transerico; he gave them to Bartolomeo the prelato of the church. And how did he know he was a monk of Ferentillo? Because everyone said so, and besides he had seen him coming to the church with the abbot. Giovanni Bonihominis, another farmer, had seen Bishop Benedetto of Rieti dining on the vigil of Saint Leopardo's feast in the church, but he had not been at the church the next morning although he had heard the bells. Another farmer, Giovanni Franconi, had seen monks coming from Ferentillo and being received as if they were in their own home, sicut in domo propria , when San Leopardo was presided over by Pietro his uncle, his mother's brother. When the land of Teodino de Amiterno was under interdict, the interdict was observed by the church of San Leopardo until a monk from Ferentillo (whose name he did not know, but it was said that he was from Ferentillo) came and celebrated service publicly with bells ringing, but the clerks of San Leopardo themselves did not take part in the services. He had seen Bishop Dodone received at the church with bells ringing when he visited the parish. And he said too that the holy oils came from Santo Stefano, and that before the dispute arose the clerks of San Leopardo had been ordained by the bishops of Rieti. Another farmer, Giovanni Alkerii, who was of the villa of the church of San Leopardo, agreed about the oil and said that the children of local farmers (pueri rusticorum ) were baptized at Santo Stefano, and that he had three times seen a bishop of Rieti whose name he did not know given hospitality in the church (and he knew he was bishop of Rieti because everybody said so: dicebatur ab omnibus ), but he had not seen a bishop for the last five years.

Oderisio Bonihominis, whose occupation is not specifically identified, saw the abbot of Ferentillo "who now is" and who is called Transerico come to the church and be received with bells and procession and be as if he were in his own home; and he had seen three monks

similarly at home, and they were called Dom Angelo, Dom Transerico, and Jericho.[87] Of an exchange of keys he had been a witness but he had not, as had an earlier witness, been in the church when Mass was sung, but he was against the wall of the church (iuxta muros ecclesie ) and heard what was said. Nicola Jordani said that when the bishop came and was received he was given cena but not pranzo or pranzo but not cena —he was not given both (and another witness spoke of a visitor's not eating cena because he was fasting). Nicola said that he saw the abbot of Ferentillo coming to the church but that he did not know whether he was received in procession or not because he was sometimes in the fields and sometimes in his own house, which was next to (or very near to [vicina ]) the church—but he heard the bells. And he said further that he had seen Pietro di Giovanni Gisonis (presumably the farmer Giovanni Franconi's uncle) having an argument with the old Lord Gentile de Amiterno during which argument Pietro had said that he did not hold the church from Gentile but from the abbot of Ferentillo. He said that everyone said that the abbot was as at home at San Leopardo and that it had been given to the abbey by the ancient emperors (ab antiquis imperatoribus ).

Pietro Pelliparius (or Pietro the tanner), who said he came from the castro near the church (et oriundus erat de castro vicino ipsius ecclesie ), had seen forty years earlier a clerk called donnus Annisio whom they had said was an oblate of Ferentillo but he did not wear a monastic habit; and he said that when Pietro had held San Leopardo he had held two other churches from the abbot of Ferentillo in the diocese of Marsi (in episcopatu Marsican' ). The farmer Benedetto said that Teodino had received letters from the lord pope which returned the church to Ferentillo; he saw them, but he did not read them or hear them read, but it was said that they were the pope's letters. The farmer Simeone saw the letters, and the farmer Rainaldo Oderisii heard them read. The farmer Gualterio Petri said that he used to hear his father saying that the church belonged to Ferentillo, and Giovanni Petri said that his father (perhaps the same Pietro father) spoke badly of (or cursed) the clerks of Ferentillo because of their acceptance of the bishop because he said the church belonged to the monks of Ferentillo.

These provoked memories of the farmer Rollando and his associates build an inconsistent but coherent oral church (remembered days in the field, by the wall, bells ringing, old emperors) for the southeastern corner of the diocese in the early thirteenth century. They are joined by more professional memories and socially more elevated ones. Most professional and professionally interested is the archpriest of Corvaro who

offers straight and detailed evidence about past episcopal behavior and receptions and also offers an explanation of current difficulties. He says that a certain abbot of Ferentillo came to the church in question and sent to the witness and demanded that the witness receive him and give him procurations. He refused and said that he was a vassalum ecclesie Reatine . The abbot, whose name he did not know, then sent to the ballivo of the place, whose name was Rayn' de Latusco, who ordered the witness to receive the abbot "without prejudice" and give him hospitality and the necessary food for not more than one day.[88] And the witness heard nothing more of the matter until the current dispute arose, after the bishop placed San Leopardo under interdict for refusing proper procurations, which offered an opportunity to Teodino de Amiterno and the abbot of Ferentillo. Letters were got from Rome which allowed Teodino to give or restore the church to the abbot of Ferentillo, who then moved in and relaxed the interdict. The archpriest's partisan memory recalls a church under the normal control of the bishops of Rieti from the time of bishop Benedetto, through the time of this present bishop, Adenolfo, when he was elect. The archpriest evokes with particular clarity the time when Adenolfo was still elect because during that time since Adenolfo was not a bishop he could not perform episcopal functions and so ordinands had to be sent to other bishops.[89] He also remembers the custom that when patrons presented clerks to vacant churches the archpriests of Santo Stefano were accustomed in the bishop's name to institute and invest them in churches within the district, including San Leopardo. The archpriest's institutionally ordered mind gives a kind of sense to his testimony different from that of the farmer witnesses, but it does not, quite noticeably, give him a better memory for names, nor does it provoke him to a greater use of sensory detail.

The archpriest's memory is countered by that of Giovanni de Fonte, clerk of San Paolo di Spedino, who, since he had been a clerk of San Leopardo, had seen Dodone, Benedetto, and Adenolfo all come to San Leopardo, but he recalls the exact nature of the reception only vaguely.[90] He remembers that when the bishop demanded procurations that seemed inappropriate because of the church's pertaining to Ferentillo, and when, upon their being refused, the bishop imposed an interdict, it fell to the witness himself to go to Rome to appeal. The episcopus respondit dure super interdicto , and the witness knew that the dominum terre [was] turbatum contra episcopum : Giovanni provokes to emotion Adenolfo (the bishop) and Teodino (the lord of the place), scions of neighboring baronial houses.

The knight Lord Gomino remembered another interdict sixty years before when the land of Gentile de Amiterno was put under interdict because Gentile had put aside the daughter of the count of Albe. The church of San Leopardo, he recalled, had not observed the interdict because—as the prelate of that church, dompno Pietro, whose father had founded the church, often said—the church itself pertained to the church of Ferentillo.[91] When he was asked how he, Gomino, knew the other churches of the Amiterno lands observed the interdict and San Leopardo did not, he said because they did not ring their bells or even open their doors and the church of San Leopardo rang its bells and celebrated divine services.

For the Rieti side two canons testified: Pietro Cifredi and Rainaldo da Pendenza. The abbot of Sant'Eleuterio testified, and the episcopal cook who, professionally, remembered that the bishop was served both night and day. The clerk Berardo, a familiar of Bishop Benedetto, saw that bishop visit as he visited other parishes, and one year when he did not go he sent two canons of Rieti, Adinulfo d'Ascenso and Pietro Cifredi. And the witness himself had gone too.[92]

A knight named Berardo said that when he was young (cum esset iuvenis ) he had gone with Bishop Dodone through the bishopric (episcopatum ) because he was the bishop's blood relative (quia consanguineus eius erat ) and that they had visited San Leopardo as they had the other parishes and that members of the familia had been given denari (a crucial point)—and he himself had received six or eight denari.[93] And another knight, Matteo Sinibaldi Dodonis, gave similar testimony, and Dodone was his uncle, his patruus . And Barbazano went with Dodone when he consecrated San Leopardo, because he often went with Dodone, but he can't remember who else was there.

Jacopo or Giacomo Sarraceno, having been asked the whole list of questions posed in order, said that he himself knew nothing.[94] But for the other side the deacon Oderisio Gerardi, the man almost a hundred, remembered a lot, some seeming confused, some of it hazy, some very exact: what happened when Bishop Dodone consecrated the chapel of Saint Martin at San Leopardo at the mandate of Gentile de Amiterno; that the bishop's boys were not given the bread they demanded in the morning; about the letter of Pope Innocent which Jericho had given to Gentile de Amiterno in the church of San Leopardo, restoring it to the abbot of Ferentillo—he had not read the letter but had heard it read by someone whose name he could not remember; and although there had been sonic clamor about the letter's being false, he, Oderisio, knew

it was not, because he had put his hand on it (them) and "they were true (vere erant )."[95] It is old Oderisio who remembers to say that the monk Transerico was a nephew of the abbot.